Informacijos mokslai ISSN 1392-0561 eISSN 1392-1487

2019, vol. 86, pp. 41–55 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2019.86.25

A study of the attitude of Generation Z to cross-cultural interaction in business

Denys Lifintsev, PhD

Kyiv National Economic University named after Vadym Hetman, Kyiv, Ukraine

denfcdk@gmail.com

Cristina Fleșeriu, PhD

Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

cristinafleseriu@gmail.com

Wanja Wellbrock, PhD

Heilbronn University of Applied Sciences, Heilbronn, Germany

wanja.wellbrock@hs-heilbronn.de

Abstract. Background and Purpose: In a digitally globalized world cross-cultural interaction in social and business environment has become more widespread than ever before. The purpose of this paper is to explore the attitude of Generation Z representatives to different aspects of cross-cultural interaction.

Design/Methodology/Approach: We used an online questionnaire to collect data for our study. A sample of 324 young adults from three countries: Germany (n=113/34.9%), Romania (n=107/33.0%) and Ukraine (n=104/32.1%) participated in the online survey. The sample consists of university students aged less than 23 years to match the criteria of being representatives of Generation Z. Different statistical tools were used to check the hypotheses.

Results: The results of the study indicate that Generation Z representatives consider cross-cultural communication skills as highly important both in their private and business life. The main motivation factors to work in a multicultural business environment have been identified as well as major barriers for effective cross-cultural interaction.

Conclusion: This paper illustrates that Gen Zers are willing to work in a multicultural business environment; moreover it can give them additional motivation. This trend along with ongoing processes of globalization and digitalization fosters further interconnection of countries and regions of the world, making cross-cultural communication and cross-cultural management techniques even more important.

Keywords: globalization, multiculturalism, Generation Z, cross-cultural management, cross-cultural communication.

Received: 10/09/2019. Accepted: 06/11/2019

Copyright © 2019 Denys Lifintsev, Cristina Fleșeriu, Wanja Wellbrock. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1 Introduction

Our world has always been more or less globalized. But every day it becomes more interconnected, and the pace of this process grows dramatically. Comparing the second decade of 21st century and early 1980s, when Harvard professor T. Levitt popularized the term “globalization” (Levitt, 1983), is like comparing the Space X Falcon rocket to a bicycle.

The key driver of such a high-rocketing speed of globalization processes is another phenomenon of our age – digitalization. A “digitally globalized” environment has changed people’s everyday life. Social networks, low-cost airlines, digital payment systems allow millions of individuals to enjoy a truly cosmopolite way of living.

The scale of digital economy is really impressive. Global production of ICT (information and communication technologies) goods and services amounts to an estimated 6.5% of the global gross domestic product (GDP), and some 100 million people are employed in the ICT services sector alone. The world’s top four companies by market capitalization are all linked to the digital economy: Microsoft, Amazon.com, Apple and Alphabet (Google). Worldwide e-commerce sales in 2015 reached $25.3 trillion with cross-border B2C (“business-to-customers”) e-commerce worth about $189 billion, with some 380 million consumers making purchases on overseas websites (UNCTAD, 2017).

Decades ago global business was a privilege of corporations with multimillion budgets. Nowadays you can operate “globally” just using your smartphone. Digital platforms and social media connect billions of individuals across the globe, providing fantastic opportunities to small and medium enterprises (SMEs). About 21% of internet users in the EU engage in cross-border e-commerce (European Commission, 2017). Digitalization has significantly simplified tasks for human resource managers and job-seekers’ search processes. LinkedIn and similar platforms are great timesavers for both sides.

Digitalization seriously influenced deep changes in the mentality of new generations. Young people (Millennials – born in 1980–1995, and Generation Z – born after 1995) growing up in the age of social media, internet of things, advanced robotics, artificial intelligence etc. are highly dependable on ICT. It defines their way of thinking, decision making, working and living.

These social and business environment megatrends foster the need of cross-cultural communication and cross-cultural management skills. Goods, services, finance, people and data flows are much faster and easier every year. More companies tend to form multinational teams and, at the same time, even small and medium enterprises are trying to operate on a global market dealing with local customers and partners.

Main aim of the paper is to explore the attitude of Generation Z representatives to different aspects of cross-cultural interaction.

We hypothesized that cross-cultural communication and interaction skills are highly important for the young people (Generation Z). They are mobile, digitally educated, and open for new incentives and projects no matter in their own countries or abroad. On the other hand, there are some serious obstacles on the way to effective cross-cultural interaction (and primarily language barriers). We also decided to check some of the stereotypes regarding national and gender differences, i.e. “men are more likely to take a chance travelling abroad” and “people from low-income countries are more willing to work in a globalized business environment mostly because it can give them an opportunity to earn more money”.

We summarized our thoughts in the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Generation Z representatives (Gen Zers) consider cross-cultural communication and interaction skills as essential due to their “digitally globalized” lifestyle .

Hypothesis 2: The majority of Gen Zers (more than 50%) would like to work in a multicultural environment.

Hypothesis 3: The majority (more than 50%) of Gen Zers are ready to move abroad for a business project for a period of one to two years.

Hypothesis 4: Men are significantly more likely than women to move abroad for a business project for a period of one to two years.

Hypothesis 5: Gender and country of origin are associated with the reasons for working in a multicultural business environment.

Hypothesis 6: There are significant differences in the perception of communication barriers depending on country of origin.

Hypothesis 7: There are significant differences in language barriers depending on the experience of cross-cultural communication.

2 Literature review

The growing pace of globalization processes fosters the researchers’ interest to cross-cultural issues in business and management. G. Hofstede’s fundamental study of value orientation in different cultures (Hofstede, 1980) is, maybe, still the most influential work in this field. The Hofstede’s model of national culture (Hofstede, 2001; Hofstede et al., 2010; Minkov et al., 2017; the official G. Hofstede centre website, 2018) consists of six dimensions: power distance (expresses the degree to which the less powerful members of a society accept that power is distributed unequally); individualism / collectivism (distinguishes the cultures where people are more concerned on personal goals and achievements from the cultures where people feel more comfortable working in teams); masculinity / femininity (illustrates the domination of traditional “male” or “female” values in different cultures); uncertainty avoidance (shows the attitude of society’s members to uncertainty); long-term orientation / short-term orientation (illustrates how “long-term oriented” the society is); indulgence / restraint (defines the role of rules in people’s behavior). The relative positions on these dimensions are expressed in a score on a 0 to 100 point scale.

Setting the scores for countries was an outstanding idea to simplify the understanding of basic assumptions regarding national cultural peculiarities. Despite some fair critique concerning limitations (McSweeney, 2002), Hofstede’s theory is still playing a monumental role in further cross-cultural research. Along with E. Hall’s theory,

that illustrates the role of context in cross-cultural interaction (Hall, 1989), Hofstede’s findings are very popular among scholars and practitioners. The measurement of culture through cultural dimensions is still highly widespread among cross-cultural management researchers (Taras et al., 2009). However, we agree with Gerhart that “significant degree of intra-country variation in culture variables may make national culture mean scores less useful” (Gerhart, 2008).

Another great contribution to cross-cultural management studies was made by N. Adler who explored the impact of culture on different organizational functions. According to Adler cross-cultural management is pointed to describe and compare organizational behavior in different cultures seeking to improve the interaction between co-workers, partners, clients, managers etc. from different countries or cultures (Adler, 1983, 1991).

In a globalized business world cultural diversity is an opportunity to find original solutions (Hoecklin, 1995). A shift toward forming multicultural teams not only in multinational corporations, but even in local businesses fosters the interest to effective diversity management techniques (e.g., DiTomaso and Hooijberg, 1996; Jehn, Northcraft and Neale, 1999; Kodydek and Hochreiter, 2013). Companies have to deal with the representatives of different cultures to get access to new markets, or searching for cheaper resources abroad, forming global multinational supply chains (Wellbrock and Hein, 2018), and cultural differences are treated by international companies as a competitive advantage (Luo, 2016) helping them “leverage the benefits of cultural differences in a wide range of contexts, such as the development of strategic capabilities, foreign direct investment and entry mode decisions and synergy creation in cross-border M&A” (Stahl & Tung, 2015). Multicultural teams are potentially more creative in problem solving than national homogenous teams (Watson et al., 1993). The heterogeneity of national cultures of team members can improve their performance if cultural diversity is properly used (Shachaf, 2008). Companies can benefit by identifying the professionals for international business assignments considering their level of cultural intelligence (Velez-Calle et al., 2018) which can be defined as “an individual’s capability to function and manage effectively in culturally diverse situations and settings” (Ott & Michailova, 2018). On the other hand, diversity “increases the ambiguity, complexity and confusion in group processes, thus being potentially devastating for the effectiveness of the team”, so the impact of national cultures on the functioning of multinational teams depends on the quality of cross-cultural management processes (Chevrier, 2003). Language barriers, differences in values and standards of behavior, lack of experience, lack of trust, and lack of knowledge about other cultures or stereotypical thinking are among the most widespread obstacles for cross-cultural communication (Lifintsev & Canavilhas, 2017, Lifintsev & Wellbrock, 2019).

Indeed, in a globalized business environment, a manager’s cultural intelligence (CQ) is highly important (Earley and Ang, 2003, Velez-Calle et al., 2018). Using special cross-cultural techniques helps to act efficiently in heterogeneous working cultures (Primecz et al., 2011) and to negotiate successfully across cultures (Søderberg and Romani, 2017). The Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) research program findings illustrate the importance of culture for organizational and leadership effectiveness (House et al., 2004).

In this study we emphasize the special role of a new generation entering the labor market right now – Generation Z. Exploring generational differences is a highly popular trend nowadays. A generational cohort is defined as an “identifiable group that shares birth years, age, location and significant life events at critical developmental stages” (Kupperschmidt, 2000). One of the most widespread approaches (Pew Research Center, 2014, Bencsik et al., 2016) classifies the generations as follows: Silent Generation (years of birth: 1928 to 1945), Baby Boomers (1944 to 1964), Generation X (1965 to 1980), Millennials or Generation Y (1981 to 1995), Generation Z (1996 to 2010).

From the childhood, Gen Zers (Generation Z representatives) experienced globalization, digitalization and cultural diversity (McCrindle, 2014; Kirchmayer & Fratričová, 2018). Internet and new technologies influenced many aspects of their lives. The norms and standards of behavior of Gen Zers are different from the norms of the previous generations. They use a lot of different words, slangs and expressions which can cause serious misunderstandings with their parents (Bencsik et al., 2016).

While Generation Z shares some characteristics with Millennials, it is a different generational cohort (Seemiller, C., & Grace, M., 2017). If Millennials were the first generation that has been characterized as “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001) or “net generation” (Tapscott, 1998), Generation Z might be called a “living-online” one. The dependence of these “digital age kids” on information and communication technologies in both personal and business issues is maybe highest ever. Being “technologically fluent” (Fratričová & Kirchmayer, 2018) they have some competitive advantages over previous generations.

Integrating technology (Google, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram etc.) into many areas of their lives Generation Z became truly “globally focused” (McCrindle, 2014). They are more likely to travel, to migrate across borders than any previous generation (Broadbent et al., 2017, Fleseriu et al., 2018). Indeed, having connections with the representatives of different cultures and backgrounds via social media (Kirchmayer & Fratričová, 2018) the Gen Zers themselves are making the environment more globalized and culturally diverse.

The results of a global research conducted by Universum with some 49,000 members of Generation Z across 47 countries, throughout America, Europe, Asia, South America, and the Middle East participating, illustrated that these young people are curious (“Curiosity is the strongest motivator for choosing a course of study”), eager to start career without formal education (“They are interested in entering the workforce without higher education, but fear actually doing so”), very entrepreneurial (“More than half of Gen Zers around the world indicated an interest in starting their own company”), interested in security and work-life balance (“Despite their entrepreneurial nature, work-life balance and job security are the two career goals most important to this generation”), pragmatic (“Gen Zers may be less optimistic than Millennials about their work opportunities”) and, obviously, willing to get new information instantly (Dill, 2015).

Numerous studies have been conducted in different countries to describe (and forecast) the behavior of the Generation Z representatives at the workplace. The results illustrate many similarities among young people from different regions of the world. The Gen Zers are called pragmatic, driven by money, willing financial security (The Wall street journal, 2018), motivated by positive corporate culture and flexibility (Deloitte, 2018). This generation chooses a career of their own interest, at the same time trying to find the work-life balance (Bencsik et al., 2016).

Due to a similar “globalized background” (Gen Zers all around the world are deeply connected by using same social media and other information sources) Generation Z surveys regarding their attitude to motivation give similar results in different countries and illustrate strong correlation with global studies. A research conducted in Romania proved that Romanian Gen Zers have very realistic views on their future career (e.g., their “expected salary at first job” is less than average monthly salary across country) (Iorgulescu, 2016). Polish Gen Zers are also pragmatic: they do not expect fast career; prefer good planning and expect constructive feedback from managers (Dolot, 2018). Slovakian Gen Zers are motivated mostly by interesting work, reward and achievements (Kirchmayer, Z. & Fratričová, J., 2017; Kirchmayer, Z. & Fratričová, J., 2018). Czech Gen Zers show themselves as pragmatic ones, too. For example, they would prefer personal communication with colleagues and managers while using ICT (which they love so much in everyday life), mostly seeking for information and learning (“developing skills”) (Kubátová, 2016).

Being the most globally connected and most formally educated generation (McCrindle, 2014) Gen Zers are most likely to work in multicultural business environments. Diversity is common for Generation Z in everyday life so is not a real obstacle for them at the workplace. On the other hand, they are concerned with equality which should be taken into consideration by managers and colleagues from other generations (Lanier, 2017).

3 Research methodology

We used an online questionnaire to collect data for our study. A sample of 324 young adults (male: n=135/41.7%, female: n=189/58.3%) from three countries: Germany (n=113/34.9%), Romania (n=107/33.0%) and Ukraine (n=104/32.1%) participated in the online survey. We have chosen these three different countries (see table 1) to have a broader perspective regarding the aim of our research.

Table 1. Some basic social and economic indicators of the analyzed countries|

Country |

Population, mln, 2017* |

EF English Proficiency Index, 2017** |

GDP per capita, PPP, USD, 2017* |

Average annual wage, EUR, 2017 |

|

Germany |

80.7 |

62.35 (high) |

50638.9 |

39446*** |

|

Romania |

21.6 |

59.13 (high) |

25840.8 |

8467**** |

|

Ukraine |

44.2 |

50.91 (low) |

8666.9 |

2842***** |

Source: *https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS, **https://www.ef.com/epi/, ***https://stats.oecd.org/ Index.aspx?DataSetCode=AV_AN_WAGE, ****www.insse.ro, *****http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/

The sample consists of university students aged less than 23 years to match the criteria of being representatives of the Generation Z. The survey was conducted during the period October 2018 to January 2019 in Heilbronn in Germany (Heilbronn University of Applied Sciences), in Cluj-Napoka and Suceava in Romania (Babeș-Bolyai University and Stefan cel Mare University) as well as in Kyiv and Lviv in Ukraine (Kyiv National Economic University named after Vadym Hetman and Lviv Polytechnic National University).

We collected opinions of respondents from nations with different cultural dimensions’ indicators (Table 2) which is important to compare the opinions of Gen Zers from different cultures. We used the data from the official website of Geert Hofstede centre (2018) to illustrate cultural differences between the selected countries.

Table 2. Cultural dimensions in analyzed countries (G. Hofstede 6-D model)|

Country |

Power distance |

Individualism |

Masculinity |

Uncertainty avoidance |

Long-term orientation |

Indulgence |

|

Germany |

35 |

67 |

66 |

65 |

83 |

40 |

|

Romania |

90 |

30 |

42 |

90 |

52 |

20 |

|

Ukraine |

92 |

25 |

27 |

95 |

55 |

18 |

Source: https://www.geert-hofstede.com

Our sample consists of countries with different expressions of the cultural dimensions’ indexes. Countries as Ukraine and Romania have very high PDI (power distance index) while Germany represents a group of lower power distance countries. German society is more individualistic, especially comparing to Romanian and Ukrainian collectivistic cultures. Germany has a masculine society, while Ukrainian and Romanian cultures are feminine. The uncertainty avoidance index is above 50 for all three nations, but Ukrainians and Romanians have extremely high indicators here. German culture has the highest long-term orientation index in our sample. All the three nations are rather restricted by rules.

The respondents were given three statements regarding the aim of the research:

1. Cross-cultural communication is an essential skill in our globalized world (the skills of cross-cultural communication (dealing with the representatives of different cultures) can help you in both personal and business issues).

2. I would like to work in a culturally diverse environment.

3. I am ready to move abroad for a business project for a period of one to two years.

In our effort to achieve higher quality data (Revilla et al., 2013) we offered the respondents an agree/disagree scale with five answer categories, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Given the number of possible answer categories in each statement of our survey (five), we considered the answers receiving more than 20% of responses as dominant. The statement can be considered as confirmed if “agree” and “strongly agree” categories receive more than 40% of responses in total.

The questionnaire contains two more questions to identify major motivators of the Gen Zers to work in multicultural environment and main barriers for effective cross-cultural communication and interaction.

First, the respondents had to share 100 points between five major motivators to work in a multicultural environment:

1. Opportunity to earn more money comparing to local businesses.

2. Experience of cross-cultural communication.

3. Opportunity to travel the world.

4. Opportunity to learn, to improve their professional level.

5. Opportunity to be a part of global projects.

Then, the respondents had to share 100 points between five main barriers for effective cross-cultural communication and interaction:

1. Language barriers.

2. Stereotypical thinking.

3. Differences in values.

4. Differences in standards of behavior.

5. Lack of trust (to the representatives of other cultures).

4 Results

The questionnaire was randomly handed out and the results showed that more than 88% of the respondents agree or strongly agree that cross-cultural communication is an essential skill in the globalized world. In respect with the country of origin, in all three countries the youngsters agree with this skill. Also, both females and males consider cross-cultural communication as being very important. Based on the results, it is proved that the Gen Zers consider cross-cultural communication as a very important skill nowadays (H1) due to their “digitally globalized” lifestyle.

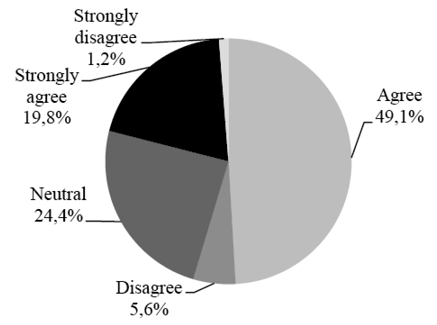

The majority (almost 70%) of the respondents would like to work in a culturally diverse environment (H2) (Figure 1), and more than 50% of them (61.4%) stated that they are ready to move abroad for a period of one to two years (H3).

In order to test if men would like more than women to move abroad for a business project for a period of one to two years (H4), a Mann-Whitney test was conducted. The test indicated that men (Mdn=4) are significantly more likely than women (Mdn=4) to move abroad for a business project for a period of one to two years (U=10,624.5, p=.008, r=-0.148). Although the difference is statistically significant, the effect is small. The equality of variance was confirmed by the Leven’s test (F(1,319.071)=.460, p=498).

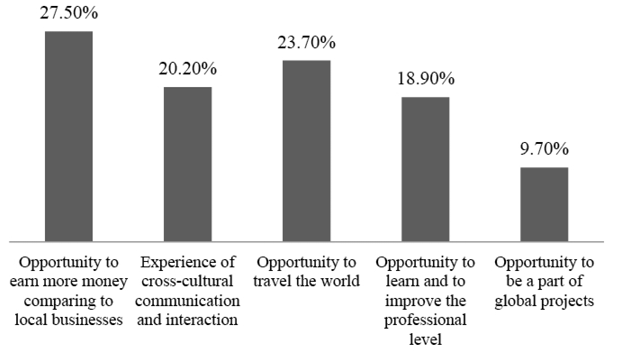

Also, from the total number of respondents, the highest percentage considers that the opportunity to earn more money comparing to local businesses is the best motivator to work in a multicultural business environment. The smallest percentage says that the opportunity to be a part of global projects is the best motivator (Figure 2).

Because the two samples are not normal distributed, a Mann-Whitney two independent sample test was run. The results indicate that men (Mdn=30) are significantly more likely than women (Mdn=24) to regard going abroad as an opportunity to earn additional money (U=9383, p<.001, r=-0.226). Although the difference is statistically significant, the effect is small. The equality of variance was confirmed by the Leven’s test (F(1,311.504)=2.785, p=096).

Another Mann-Whitney test indicates that women (Mdn=25) are significantly more likely than men (Mdn=20) to regard going abroad as an opportunity to travel (U=9210.5, p<.001, r=-0.237). Although the difference is statistically significant, the effect is small. The equality of variance was confirmed by the Leven’s test (F(1,313.553)=1.323, p=251).

Thus, we see that men are more willing to work abroad and they are more driven by money comparing to women. While men are more motivated to earn extra money during business projects abroad, women are more likely to be motivated by travelling itself.

Gen Zers from countries with lower economic living standards (Ukraine, Romania) are more interested in cross-cultural interactions because a global business environment is financially more attractive for them comparing to a domestic one.

Because the samples are not normally distributed, an independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. A Dunn post-hoc test revealed that Ukrainians (Mrank=185.75) are significantly more likely to view traveling abroad as an opportunity to make more money than Germans (Mrank=142.62), (chi^2= 11.549, df = 2, p=.003).

On the other side, a Dunn post-hoc test revealed that Germans (Mrank=178.42) are significantly more likely to view traveling abroad as an opportunity to experience cross-cultural communication than Ukrainians (Mrank=141.76), (chi^2= 8.523, df = 2, p=.014).

We found a correlation between a country’s average income (Table 1) and motivation factors to work in a global business environment. The lower average domestic income (salary) is the more important role material motivation is playing. While Ukrainians (the country with the lowest average income in our sample) are mostly driven by the opportunity to earn extra money working in global companies, the Germans (country with the highest average income in our sample) have the highest interest to experience interaction with other cultures. Obviously, this trend cannot be considered as typical only for Gen Zers: Millennials and some of Generation X representatives from countries with lower living standards are motivated to work abroad mostly because of material motivation reasons.

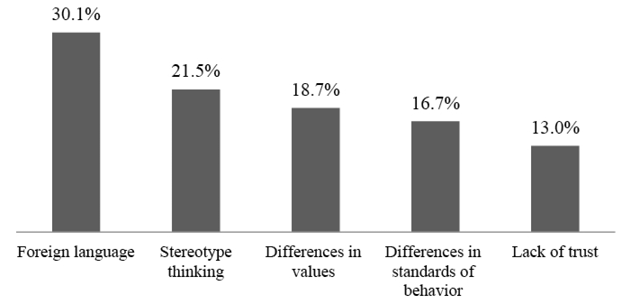

When analyzing the barriers for effective cross-cultural communication, almost 1/3 from the respondents consider the language barrier as the biggest one, followed by the stereotypical thinking, the differences in values and behavior standards and the lack of trust in the representatives of other cultures (Figure 3).

In order to see if the country of origin can influence the way young people see the barriers for an effective communication (H6), some statistical tests were used. Because the samples are not normally distributed, an independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. A Dunn post-hoc test revealed that Ukrainians (Mrank=187.46) are significantly more likely to perceive language barriers as being important than both Germans (Mrank=149.36) and Romanians (Mrank=152.11), (chi^2= 10.944, df = 2, p=.004).

We noticed a correlation between the level of English language knowledge in a country and the importance of a language barrier as an obstacle for effective cross-cultural communication. The higher the English Proficiency Index (Table 1), the less of an obstacle language barriers are being treated.

In addition, a Dunn post-hoc test revealed that Ukrainians (Mrank=140.21) are significantly more likely to perceive stereotype thinking as a barrier than Romanians (Mrank=179.44), (chi^2= 9.678, df = 2, p=.008), and Germans (Mrank=179.92) are significantly more likely to perceive differences in values as a barrier than Romanians (Mrank=150.27), (chi^2= 6.238, df = 2, p=.044).

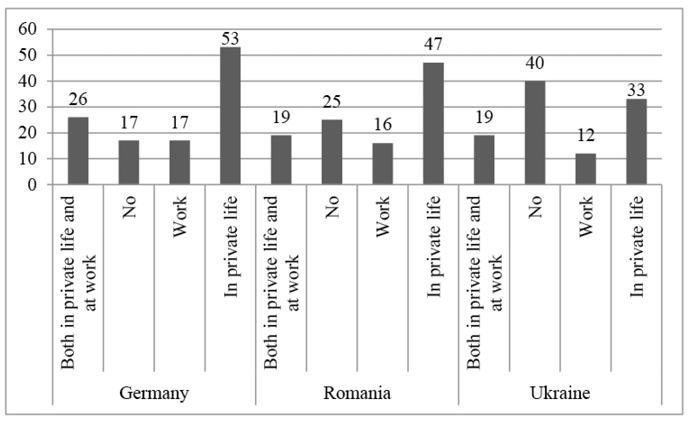

Related with the experience that the respondents already have with cross-cultural communication, in Ukraine, 38% of them do not have it. In Romania, 23% do not have an experience while in Germany the percent is even smaller (15%). From those that have a cross-cultural communication experience in all the analyzed countries, the majority has it from private life (Figure 4).

To analyze if there is a significant difference in language barriers depending on the experience of cross-cultural communication (H7), an independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. A Dunn post-hoc test revealed that people with no experience of cross-cultural communication perceive the language barrier as being more important (Mrank=182.77) than people with experience in both work and private life (Mrank=139.5), (chi^2= 8.634, df = 3, p=.035).

4. Conclusions and discussions

Comparing the results of our survey with the global studies aimed to describe the behavior of Gen Zers in business (Deloitte, 2018; the Wall street journal, 2018) we found a lot of things in common. On the other hand, our study was focused on the specific attitude of the Gen Zers to cross-cultural interaction in business, and the findings illustrate that these young people are not only open and tolerant to diversity in everyday life and in office. Moreover, a multicultural environment itself gives them additional motivation at the workplace.

Our sample consists of representatives of three quite different nations with specific cultural backgrounds and different levels of average income. Despite such differences, the majority of young people show a similar attitude to work in a multicultural business environment. The respondents proved they are mostly driven by money, giving the “opportunity to earn more in global business” the highest rank in their motivation hierarchy, which correlates with other studies (the Wall street journal, 2018; Kubátová, 2016; Kirchmayer, Z. & Fratričová, J., 2018 etc). “Opportunity to travel the world” is the second strongest motivator for the respondents from all of the three countries from our sample. Thus, we can describe Gen Zers as open-minded, global-oriented people who are ready and willing to work in a multicultural business environment, highly motivated to earn extra money using opportunities provided by globalization. In the same time, among the biggest threats for effective cross-cultural interaction, in their opinion, are language barriers and stereotypical thinking.

Gen Zers from different nations have a lot of things in common nowadays due to their “digitally globalized” lifestyle. Indeed, due to globalization and digitalization, young people from almost all over the world are influenced by the same trends through the Internet, social media and popular culture (McCrindle, 2014). This is why their attitude to cross-national differences in values and standards of behavior as possible obstacles for cross-cultural communication is moderate comparing to the fear of language barriers.

Considering the growing pace of globalization, a rising interdependency among countries (Verbeke et al., 2018) and the emerging role of digital technologies along with the growing share of Gen Zers in the working force worldwide (Deloitte, 2018), we can forecast a further interest in cross-cultural interactions and cross-cultural management. Small and medium enterprises entering the global market as well as large multinational corporations rely always more on young professionals, giving them international assignments. In general, being physically well-prepared for business trips abroad due to their young age, the Gen Zers are additionally motivated with such a kind of activity. Another possible trend is the emerging role of young professionals from the developing countries. Among the key factors fostering their motivation are simple access to education (including self-education), easiness to get a job in almost any country, and significant differences in incomes between developed and developing countries. Indeed, in a modern society, when intellectual capital becomes dominant (Lazarenko, 2014), companies do not care about the nationality of their workers. On the other hand, their soft skills, including cultural intelligence (Earley and Ang, 2003; Velez-Calle et al., 2018), are playing a significant role.

Of course, our study has some limitations. We focused only on three European countries and our sample consists of only university students. While we are certain that university students are most likely to form the majority of the future working force involved in cross-cultural interaction, the number of countries chosen for our research is not sufficient to make global conclusions. Further research may include larger sample of cultures (nations), including a cross-continental comparison. We are also interested in intra-country investigations that may help to compare regional differences mentioned by some of Hofstede’s approach critics (e.g., McSweeney, 2002).

This paper shows that Generation Z representatives are willing and ready to work in a multicultural business environment, making the world even more interconnected and globalized. The new face of the working force worldwide is probably the most globally oriented ever. Such a mentality of the Gen Zers, along with further processes of globalization and digitalization, fosters cross-cultural interaction and communication and makes cross-cultural management skills and techniques even more important for managers not only in transnational corporations, but in small and medium local businesses as well.

Acknowledgments

We are sincerely grateful to our friends and colleagues for their help with the online-survey: Dr. Prof. Olha Melnyk for conducting the survey in Lviv, Ukraine; Dr. Prof. Carmen Nastase, Dr. Mihaela State for conducting survey in Suceava, Romania.

Literature

Adler, N. (1983) Cross-Cultural Management: Issues to Be Faced, International Studies of Management & Organization, 13:1-2, 7-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1983.11656357

Adler, N. (1991) International dimensions of organizational behaviour. Boston, MA: PWS-Kent Publishing Company.

Bencsik, A., Horváth-Csikós, G., & Juhász, T. (2016). Y and Z generations at workplaces. Journal of Competitiveness, 8(3), 90-106. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2016.03.06

Broadbent, E., Gougoulis, J., Lui, N., Pota, V., & Simons, J. (2017). Generation Z: global citizenship survey. What the World’s Young People Think and Feel, 26-44.Chevrier, S. (2003). Cross-cultural management in multinational project groups. Journal of World Business 38: 141–149. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sylvie_Chevrier/publication/222549889_Cross-cultural_management_in_multinational_project_groups/links/5a34d2960f7e9b10d8436857/Cross-cultural-management-in-multinational-project-groups.pdf. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1090-9516(03)00007-5

Deloitte. Millennial Survey (2018). [online], retrieved December 21, 2018. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/millennialsurvey.html

Dill, K. (2015). 7 Things Employers Should Know About The Gen Z Workforce, Forbes Magazin, 11.6. Available from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/kathryndill/2015/11/06/7-things-employers-should-know-about-the-gen-z-workforce/print/

DiTomaso, N. & Hooijberg, R. (1996). Diversity and the demands of leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 7(2), 163-187, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(96)90039-9

Earley, C., and S. Ang. 2003. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions across Cultures. Stanford: University Press.

Dolot, A. (2018) The characteristic of Generation Z, “e-mentor” 2018, s. 44–50, http://dx.doi.org/10.15219/em74.1351.

European Commission (2017). Europe’s Digital Progress Report. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/europes-digital-progress-report-2017

Fleșeriu, C., Cosma, S., Bocăneț, V., Bota, M. (2018). The influence of age on how Romanians choose a hotel, in Generational impact in the Hospitality Industry, Edit. Cosma et al., Publisher RISOPRINT, Cluj-Napoca. Available from: https://tbs.ubbcluj.ro/ehi18/Book-EHI18.pdf.

Fratričová, J. & Z. Kirchmayer (2018). Barriers to work motivation of Generation Z. Journal of human resource management, vol. XXI, 2/2018, 28-39.

Gerhart, B. (2008) Cross Cultural Management Research Assumptions, Evidence, and Suggested Directions. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management: Vol 8(3): 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595808096669

Hall, E. T. (1989). Beyond culture. New York: Anchor. Hoecklin, L. (1995) Managing Cultural Differences: Strategies for Competitive Advantage. London: Economist Intelligence Unit/Addison Wesley.

Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084068300400409

Hofstede, G., Hofstede G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Revised and Expanded 3rd Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.7389951

House, R., P. Hanges, M. Javidan, and V. Gupta (2004). Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Iorgulescu, M. C. (2016). Generation Z and its perception of work. Cross-Cultural Management Journal, 18(01), 47-54.

Jehn, K.A., Northcraft, G.B., & Neale, M.A. (1999). Why differences make a difference: A field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in workgroups. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(4), 741-763. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667054

Kirchmayer, Z. & Fratričová, J. (2017). On the Verge of Generation Z: Career Expectations of Current University Students, Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020, IBIMA, Vienna, 1575-1583.

Kirchmayer, Z., & Fratričová, J. (2018). What motivates generation Z at work? Insights into motivation drivers of business students in Slovakia. Innovation Management and Education Excellence through Vision 2020, IBIMA, Milan, pp. 6019-6030.

Kodydek, G., Hochreiter, R. The Influence of Personality Characteristics on Individual Competencies of Work Group Members: A Cross-cultural Study. Organizacija, North America, 46, oct. 2013. Available at: <http://organizacija.fov.uni-mb.si/index.php/organizacija/article/view/530/961>. Date accessed: 05 Dec. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2478/orga-2013-0017

Kupperschmidt, B. (2000). Multigenerational employees: Strategies for effective management. Health Care Manager, 19(1), 65-76. https://doi.org/10.1097/00126450-200019010-00011

Lanier, K. (2017). 5 things HR professionals need to know about generation Z: Thought leaders share their views on the HR profession and its direction for the future. Strategic HR Review, 16(6), 288-290. https://doi.org/10.1108/shr-08-2017-0051

Lazarenko, Y. (2014). The adoption of open innovation practices: a capability-based approach. Scientific Journal of Kherson State University. Series “Economic Sciences”, issue 9, vol.2, p.42-46.

Levitt, T. (1983). The globalization of markets. Harvard Business Review, May-June 1983. Available at: https://hbr.org/1983/05/the-globalization-of-markets. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.5060250311

Lifintsev, D. (2017). Cross-cultural management: obstacles for effective cooperation in multicultural environment / D. S. Lifintsev, J. Canavilhas // Scientific bulletin of Polissia. – 2017. - № 2 (10). P. 2. – pp. 195-202. https://doi.org/10.25140/2410-9576-2017-2-2(10)-195-202

Lifintsev, D., & Wellbrock, W. (2019). Cross-cultural communication in the digital age. Estudos em Comunicação, 1(28), 93-104.

Luo, Y. (2016) Toward a reverse adaptation view in cross-cultural management. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management: Vol. 23, No1, 2016, pp. 29-41. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-08-2015-0102

McCrindle, M. (2014), The ABC of XYZ: Understanding the Global Generations, 3rd ed., McCrindle Research, Bella Vista.

McSweeney, B. (2002). Hofstede’s model of national cultural differences and their consequences: A triumph of faith - a failure of analysis. Human Relations, 55(1), 89-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726702551004

Minkov, M. et al. (2017). A revision of Hofstede’s model of national culture: Old evidence and new data from 56 countries, Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, issue 3, 2017, pp. 386 - 404. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-03-2017-0033

Ott, D. L., & Michailova, S. (2018). Cultural intelligence: A review and new research avenues. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 99-119. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12118

Pew Research Center. (2014). The next America: Boomers, millennials, and the looming generational showdown. New York: PublicAffairs. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.52-0573

Primecz, H., I. Romani, & S. Sackmann. (Eds.). (2011). Cross-cultural management in practice. Culture and negotiated meanings. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9780857938725.00018

Revilla M., Saris, W., Krosnick, J. (2013), Choosing the Number of Categories in Agree–Disagree Scales Sociological Methods & Research Vol 43, Issue 1, pp. 73 - 97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113509605

Shachaf, P. (2008). Cultural diversity and information and information technology impacts on global virtual teams: An exploratory study. Information & Management, 45(2). 131-142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2007.12.003

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2017). Generation Z: Educating and engaging the next generation of students. About Campus, 22(3), 21-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21293

Søderberg A.-M., Holden N. (2002) Rethinking cross cultural management in a globalizing business world. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 2(1): 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/147059580221007

Søderberg, A. M., Romani L. (2017). Boundary spanners in global partnerships: A case study of an Indian vendor’s collaboration with western clients. Group & Organization Management, 42 (2), 237–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601117696618

Stahl, G.K. & Tung, R. (2015). Towards a more balanced treatment of culture in international business studies: The need for positive cross-cultural scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 391-414. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269992746_Stahl_GK_Tung_R_2015_Towards_a_more_balanced_treatment_of_culture_in_international_business_studies_The_need_for_positive_cross-cultural_scholarship_Journal_of_International_Business_Studies_46_391-41 [accessed Feb 02 2019]. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.68

Taras, V., J. Rowney, and P. Steel (2009). Half a Century of Measuring Culture: Review of Approaches, Challenges, and Limitations Based on the Analysis of 121 Instruments for Quantifying Culture. Journal of International Management 15 (4):357–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2008.08.005

The official site of EF “Education first” (2018), available at: https://www.ef.com/epi/ (Accessed 2018).

The official site of G. Hofstede centre (2018), available at: https://www.geert-hofstede.com (Accessed 2018).

The official site of the World Bank (2018), available at: http://www.worldbank.org (Accessed 2018).

The Wall street journal. Gen Z Is Coming to Your Office. Get Ready to Adapt. [online], retrieved December 21, 2018. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/graphics/genz-is-coming-to-your-office/

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2017). Information Economy Report 2017: Digitalization, Trade and Development. Available at: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ier2017_en.pdf. https://doi.org/10.18356/3321e706-en

Velez-Calle, A., Roman-Calderon, J. P., & Robledo-Ardila, C. (2018). The cross-country measurement invariance of the Business Cultural Intelligence Quotient (BCIQ). International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 18(1), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595817750684. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595817750684

Verbeke, A., Coeurderoy, R., & Matt, T. 2018. The future of international business research on corporate globalization that never was…. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(9): 1101-12 https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-018-0192-2

Watson, W. E., Kumar, K., & Michaelsen, L. K. (1993). Cultural diversity’s impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal, 36: 590–602. https://doi.org/10.2307/256593