Informacijos mokslai ISSN 1392-0561 eISSN 1392-1487

2020, vol. 90, pp. 26–41 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2020.90.48

Communication Strategies Used in Teaching Media Information Literacy for Combating Hoaxes in Indonesia: A Case Study of Indonesian National Movements

Nurul Hidayatul Ummah

Department of Media and Communication, University of Leicester, United Kingdom

nurulluuz@gmail.com

Muchamad Sholakhuddin Al Fajri

Faculty of Vocational Studies, Airlangga University, Indonesia

m-sholakhuddin-al-fajri@vokasi.unair.ac.id

Abstract. This study examined communication strategies used by Indonesian national movements to teach media information literacy as an endeavour to fight hoaxes. The in-depth online interview and content analysis had been employed to investigate approaches of the movement to campaign media information literacy competence to society. The findings reveal that the offline communication has been massively applied by the movement to establish direct engagement to give a comprehensive understanding. Moreover, in the case of online communication, the content of Instagram shows that the movements predominantly use Instagram for marketing tools which post much information related to offline activities, instead of educated contents that contain media information literacy understanding. This study suggests that educating media information literacy through online communication should be prioritised, as 140 million Indonesians are active social media users, dominated by the youth aged 18-24 who are prone to be attacked by fake news.

Keywords: hoax news, media information literacy, digital media, content analysis, communication strategy, social media, Instagram

Komunikacijos strategijos ir medijų informacijos raštingumas kovojant prieš melagingas žinias Indonezijoje: Indonezijos visuomeninių judėjimų pavyzdžiai

Santrauka.Straipsnyje tiriamos Indonezijos visuomeninių judėjimų komunikacijos strategijos kaip pastangos kovojant prieš melagingą informaciją. Tyrimo tikslams pasitelkta turinio analizė ir išsamus internetinis klausimynas leido ištirti, kaip šie judėjimai rengė kampanijas nukreiptas į visuomenės medijos informacijos raštingumo didinimą. Tyrimo išvados parodė, kad ne internetinis bendravimas buvo plačiai taikomas užtikrinant tiesioginį visuomenės įtraukimą ir supratimą. Internetinės komunikacijos atveju, konkrečiai analizuojant turinį, kuriuo dalijamasi Instagram platformoje, buvo nustatyta, kad visuomeniniai judėjimai daugiausiai naudojosi platformos teikiamomis rinkodaros priemonėmis ir dalijosi daugiausia su ne internetine veikla susijusiu turiniu, o ne medžiaga apie medijų informacijos raštingumo didinimą. Remiantis tyrimo išvadomis teigiama, kad prioritetas turėtų būti teikiamas skaitmeniniam turiniui apie medijų informacijos raštingumą, kadangi 140 milijonai Indonezijos gyventojų yra aktyvūs socialinių platformų naudotojai, iš kurių didžiausią dalį sudaro 18-24 m. amžiaus gyventojai, kurie šiose platformose linkę susidurti su melagingomis žiniomis.

Raktiniai žodžiai: melagingos žinios, medijų informacijos raštingumas, skaitmeninės medijos, turinio analizė, komunikacijos strategijos, socialinės medijos, Instagram

Received: 19/04/2020. Accepted: 15/05/2020

Copyright © 2020 Nurul Hidayatul Ummah, Muchamad Sholakhuddin Al Fajri. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The rapid development of communication technology has made the spread of information become very quick. The internet has eased for everyone to produce, access and disseminate information (Waheed, 2019) especially through social media like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or cross-platform messaging such as, WhatsApp and others. The given information, however, cannot be easily and adequately filtered. Social media can provide one-sided information or opinion which is difficult to clarify its authenticity (Del Vicario et al., 2016). Santoso and Wardiana (2017, p. 30) also assert that the quick change of technology does not go along with the understanding of users in operating the devices wisely. This lack of understanding can cause various problems such as the proliferation of hoax news.

The propagation of hoaxes has become one of governments’ concerns as hoaxes could cause doubt, fears and anger to the public and even could split the harmony of society as well as a nation (Bakhsi et al., 2014; Jang et al., 2018). In multicultural Indonesia, for instance, according to the Ministry of Communication and Information of Indonesia, the number of hoax news has reached approximately 800,000 in a year (Juliawanti, 2018). The fact that Indonesia has many active internet users may contribute to the quick spread of fake news. As Internet World Stats show, Indonesia is in the top 5 countries with the highest number of internet users in which per December 2017 the number of Indonesian internet users is approximately 143,260,000 of 266,794,980 population (Internet World Stats, 2018). Several attempts have been made to combat the proliferation of hoax news in social media. One of them is by creating media information literacy program. This program has been campaigned by several Indonesian national movement such as Siberkreasi, MAFINDO and AIS Nusantara (multi-stakeholder initiatives which aim to improve media information literacy skills for Indonesian internet users to combat against hoax news).

Several scholars have analysed the role of media information literacy in decreasing the spread of fake news (e.g. Jang et al., 2018; Kurniawan et al., 2019; Mihailidis and Viotty, 2017; Wijaya, 2019). For instance, the former study from Inayatillah (2018) that surveyed the utilising of media information literacy (MIL) to higher school students in Indonesia found that the understanding of MIL in higher school students has a positive impact on students’ views of the new information that they obtained. To be more specific, they more have the awareness to recheck the information in order to obtain the accurate information, while before having the understanding of MIL, students are more likely to absorb the information merely based on what they hear and see.

Despite this number of previous studies on MIL and fake news or hoaxes, very limited research investigates communication strategies used by institutions, schools, or communities in Asia especially Indonesia which has a high number of internet users to teach MIL as an attempt to combat hoaxes. Thus, this present study tries to fill the gap by analysing communication strategies employed by Indonesian communities and the representation of social media content of the movement by using in-depth interviews and content analysis respectively.

Literature Review

The Concept of Hoax News

Hoax comes from the word hocus which means “to perpetrate a trick or hoax on” (Santoso and Wardiana, 2017, p. 30). According to Merriam-Webster, hoax is “an act intended to trick or dupe”. Generally speaking, hoax news is the news that “purposely spread to deceive people” (Lazer et al., 2018, p. 1094). Further, Santoso and Wardiana (2017, p. 30) assert that as fabricated lies, a hoax can merge as fake news, modified pictures/meme, etc. Therefore, this study uses both terms of hoax and fake in the subsequent explanation since the two-term have a similar meaning and is used in many works of literature.

Some scholars point out that the aim of the spread of hoax news is for political purpose, mainly during the election process (Nelson and Taneja, 2018; Lazer et al., 2018; MacGonagel, 2017, Frederiksen, 2017). Silverman and Singer-Vine (2016) show fake news has massively spread in Facebook during the 2016 US general election, and many people in the US report they believe in the hoax news. Another study from Azali (2017. p. 2) found that hoax news could come from sectarian, ethnicity and religious group, with spreading the hoax news or hate speech by malicious group or extremism to blemish particular group. Therefore, it could be stated that hoax news could come from various elements including politics and sectarian issues.

Rubin, Chen and Conroy (2015) classified fake news into three types; serious fabrications, large-scale hoaxes, and humorous fakes. Journalists primarily do a serious fabrication, which is well-structured as a piece of news. It is divided into two types: yellow press and tabloids. Both of them focus on exaggeration information, such as sensation crime stories, astrology, gossip columns about celebrities, and junk food news (Rubin et al., 2015). Large-scale hoaxes are mainly social media-based hoaxes. This hoax news spreads in multi-platform social media which attempt to deceive audiences as a prank and joking, causing harm to the victims who believe in that news (Rubin et al., 2015). The last type is a humorous fake. This type of fake news intends to entertain and creating humour. According to these types of fake news, this research focuses on large-scale hoaxes which mainly spread in multi-platform social media.

Social media might provide the freedom of sharing and creating content that paves the way for the diffusion of misinformation and hoaxes (Tacchini et al., 2017, 1). The internet platforms have become the essential medium in spreading fake news due to the affordable medium as well as the fast medium in connecting others (Lazer et al., 2018:1094). The internet, it is said, not only “provides a medium for publishing fake news but also offers to actively promote dissemination” (Lazer et al., 2018, p. 1096). Some actions have been made by the government to combat the spread of hoax news in Indonesia, including teaching MIL to the public.

Media Information Literacy

Technically, literacy is defined as the ability of writing and reading (Gilster, 1997, 1). However, many scholars have interpreted that literacy has extended to broaden meaning beyond reading and writing competency. The term literacies have extended to the visual literacy (Moore and Dawyer, 1994), television literacy (Siniscalco, 1996), cine-literacy (British Film Institute, 2000), and Information literacy, (Bruce, 1997). Therefore, it can be concluded that literacy has broadened its meaning from writing and reading skills only to the understanding of various information.

The growth of media technology has made “the boundary between information and other media have become increasingly blurred” (Buckingham, 2006, p. 22). The information provided by the media cannot be filtered properly, in other words, the media provides too much general information (Abner et al., 2017). Therefore, MIL is essential since the internet is becoming inevitably embedded in everyday life; if we cannot critically operate it, it will change our life (Gilster, 1997, p. 2).

Communication Strategy

Generally, communication strategy is working on a business goals framework. It pays attention to the customer’s needs, surveys the competitive environment, identifies the uniqueness of brands, and builds successfulness. In other words, the communication strategy combines “marketing, public relations, and internal communications” (Holston, 2015). However, this research focuses on the strategic communication used by the organisation to achieve its goals. Falkherimer and Heide (2018) demonstrate that there are two fundamental approaches of communication strategy from the traditional perspective which can be used for practitioners or researchers, organisational approach and societal approach. Organisational approach spotlights on the essentials of strategic communication processes for the efficiency of organisation, culture, democracy, management and related aspects, while societal approach focuses on analysing the publics’ attitudes, the public opinion, democracy, and culture contractions and many others. In this regard, this research focuses on the organisational approach of strategic communication in achieving its goals.

Several organisations employ the online and offline strategy to achieve its goal (Kitchen, 2017, p. 11). This is because both strategies give ample benefits to the organisation to reach its target regarding alluring the customer (Kitchen, 2017, p. 111). In doing so, an organisation needs to set a plan to build the communication strategy through online and offline communication. The online communication can assist the organisation to campaign their messages. As Wood and Smith (2001) point out, online communication has its aim to support a human for getting close with the technology socially or communicatively. Furthermore, establishing interactions among the public through online communication tools is essential in constructing a virtual community to engage with the public closely (Lin, 2007). The offline communication also could be applied due to the strong ties to the society that can be obtained by establishing direct engagement (Penard and Pousing, 2010). The organisation might implement offline communication in the two forms; participatory communication and face-to-face communications. Participatory communication allows sharing information through dialogue and gives new insight for the society to improve the understanding of addressing particular issues (Thomas & Mefalopulos, 2009, p. 9). On the other hand, face-to-face communication is more direct interaction by showing the appearance (Duncan & Fiske, 1977). Besette (2004:32) demonstrates that two-way communication and participation is a valuable method to fully engage with the society directly through dialogue to transform new insight or share the knowledge and even to address the problem.

In line with this study, the communication strategy is primarily needed to be employed by the organisation to inform the public about the urgency of understanding MIL. It is also indispensable for the organisation to design a communication strategy to campaign MIL either through online or offline communication.

Methods

The data of this study were collected from in-depth interviews and from Siberkreasi’s Instagram account. An in-depth interview is usually employed to seek the ‘deep information and knowledge’ (Johnson & Rowlands, 2012, p. 100; Poynter, 2010, p. 132). The significant advantage of using in-depth interview is that the researchers can explore the knowledge from the interviewees in a very deep understanding (Johnson, 2001:104). Thus, this method is primarily needed for this study since we aim to dig an in-depth knowledge and information from the participants. The in-depth interview also allows the researcher to access rich data from the participants which are crucial for the study (Morris, 2015). Therefore, these online in-depth interviews are absolutely essential to gain direct and intensive insight from the participants. As Boyce and Neale (2006, p. 3) argued, it is crucial to conduct an in-depth interview technique because it has a very intense individual interview, “to explore their perspective, particular idea, program, and situation”. The in-depth interview was employed to answer the first research question about the communication strategies used by the communities.

Three participants were selected for this study: one from the committee of Siberkreasi (henceforth interviewee No. 1), and two others from communities that support Siberkreasi: MAFINDO (interviewee No. 2) and AIS Nusantara (interviewee No. 3). They were selected purposively as appropriate representatives (Nunan, 1992; Richards, 2003) based on criteria. First, to make sure that we acquired accurate and detailed information, we selected one of the founders or board members of each community as the participant. Second, the participants must understand the management of the social media account of the community. These three participants therefore were expected to give sufficient data.

The next data were collected from the content of the communities’ social media account. Social media posts and other virtual documents according to Bryman (2016, p. 299) are potential data to the researcher in conducting either qualitative or quantitative research. This is because the social media provides a ‘big data’ which can easily become subject of the research. The ‘big data’ gives a chance for the researchers to examine other means of social media platforms, such as, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter which are believed to be common-used data of content analysis research in the future (Bryman, 2016, p. 301). It should be noted, however, because of limited space, we only investigated Siberkreasi’s social media account. Siberkreasi is an Indonesian national movement to overcome the biggest potential threats that are being faced by Indonesia, namely the spread of negative content through the internet such as hoaxes, cyberbullying and online radicalism. Countermeasures are carried out by socializing MIL to various sectors, especially education. This movement also encourages people to actively participate in spreading positive content through the internet and to be more productive in the digital world. Siberkreasi comes from initiatives with various groups, caring communities, the private sector, academics, civil society, government and the media. Besides, Siberkreasi is the largest national movement that contains many communities and institutions which have the same vision to improve MIL competence of the Indonesian society. Thus, Siberkreasi could represent the movement of the country to campaign MIL competence from all the communities and institutions that cover the whole country.

Siberkreasi’s Instagram account was selected since the organisation is more active on the Instagram platform rather than other social media platforms. We selected images and videos that were posted by Siberkreasi account from September 20, 2017 to June 30, 2018. This resulted in 223 posts consisting of images and videos. The period was preferred because the account was very active during this period and in June 2018 there was an election for local government. Therefore, there might be some fake news before and after this political agenda that triggers Siberkreasi to post more content on their Instagram to advise people to be aware of hoax news.

Content analysis was used in this study to examine the content of Siberkreasi’s Instagram account. Bryman (2016, p. 283) defines content analysis as a methodology which analyses documents and texts that contain words, images in printed or online media, aiming to find out the quantitative content by deciding categories in advance. The categories or codes are explained in the following section.

To conduct the content analysis, several codes were created. The coding was determined following the previous study of Instagram analysis of communicating via photograph by Geurin-Eagleman and Burch (2015). Eleven variables were used including date of images (1), theme of images (2), image’s content (3), what the image is about, (4), how the image is presented (5), what colour is shown (6), what language is used (7), who the picture of the person is indicated (8), number of likes (9), number of comments (10), and number of video viewers (11).

To analyse the result of the 11 variables, the researchers divided the analysis into three sections: the content, the appearance, and the engagement. The first category was the content of the images/videos that came from variables 2, 3, and 4. It examined whether the posts contain general/specific information, educative information or others. The second section describes the appearance of the images/videos. It covers variables 5, 6, 7 and 8. The presentation of the posts was analysed by the presence of image, colour, language, and the person shown. Lastly, the third section was the engagement of the images/videos. Beullens and Schepers (2013) argue visual images on the social media platform could be analysed within “social media post and comment”. This section analysed how many interactions that could be generated by @siberkreasi by counting the likes (variable 9), comments (10), and views of vidoes (11).

Results and Discussion

Communication strategies

As discussed in Section 2.3, a communication strategy is indispensable to every organisation for achieving its goal (Hallahan et al. 2017, p. 3). In line with that theory, the communication strategy was also employed by Siberkreasi to educate society about MIL competency. Many actions have been conducted to campaign the MIL. Some strategies such as offline and online communication are being chosen to convey the aim of Siberkreasi (interviewee No. 1). The decision was acceptable since many organisations often employ both online and offline communication to whom they targeted in term of alluring the customers (Kitchen, 2017, p. 111).

Offline activities could be derived from the combination of face-to-face communication and participatory communication. Face-to-face communication is more direct interaction with showing the appearance (Duncan and Fiske, 1977), while participatory communication is direct engagement with the particular group through dialogue (Thomas & Mefalopulos, 2009, p. 9). In regards to the offline activities theory above, Siberkreasi has set out various events in many Indonesian regions and those events have become their priority to campaign MIL, as being said

“we maximise the offline event to the society all over Indonesia, for example, we could conduct the offline activities in 8, 6, or 12 times a week all over Indonesia, so we have almost full day offline event in a week” (interviewee No. 1).

Those strategies also have been employed by the other communities of MAFINDO and AIS Nusantara. Both communities are using offline communication in several places of Indonesia. MAFINDO, for instance, has a regular agenda to campaign MIL skills and the adverse effect of hoax news through a massive campaign in public space such as in a weekly car-free day event by giving a brochure that contains information about the understanding of MIL and the harm of hoax news (interviewee No. 2). Similarly, AIS Nusantara also set the regular schedule such as “ngaji sosmed”, a monthly meeting with the student of Islamic boarding school in particular region, to educate students in mastering MIL skills (interviewee No. 3).

Therefore, it can be stated that every community has its regular activities for educating the society related to MIL issues on their way but still have the same vision; educating public in general. For instance, the Siberkreasi can target the audience in various places in Indonesia, including rural regions. While MAFINDO could educate the public in the public space, and AIS Nusantara are more likely to target the students. This approach might be effective in covering all the elements of the society.

The online activities are the second communication strategy that has been applied by Siberkreasi and other two communities. Online communication has been chosen by Siberkreasi to deliver their message. All the social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, Website, and Instagram are being employed to campaign the urgency of MIL competency (interviewee No. 1). Similarly, the two communities also use their all social media platforms to deliver their message (interviewee No. 2 & 3).

The online communication has its benefits to engage closely with the audiences through means of communication technology (Paul, 2011; Lin, 2007). It is also believed that employing online communication helps to cover all the audiences with the technology socially and communicatively (Wood & Smith, 2001). More specifically, Siberkreasi employs not only social media platforms as their tool, but also other means of online communication, such as the SMS blast and cooperating with the company provider to place an advertisement that contains educated content related to MIL understanding in a particular smartphone application (interviewee No. 1).

Moreover, it is interesting to note that the collaboration with influencers such as celebrities in Instagram, Youtubers, and other public figures to create educated content in social media gains much more the public’s attention (interviewee No. 1). This is emphasized by the scholar who argues that the power of celebrity in advocating the social program is gaining the public’s interest (Thrall et al., 2008, p. 363), such as Al Gore and over one hundred fellow celebrities who brought global attention to climate change through Live Earth, a twenty-four-hour concert, and Angelina Jolie for the United Nations High Commission of Refugees, who takes a part in aiding the refugees. Thus, this strategy might give a huge contribution to deliver messages of Siberkreasi in terms of capturing public’s attention.

Even though the online communication provides ample benefits in fostering the interaction through the cutting-edge technology (Best, Manktelow & Taylor, 2014), the usage of online communication by Siberkreasi is not as massive as offline communication. They are more likely prioritise direct engagement with the society to give a more comprehensive understanding (interviewee No. 1). Presumably, they more focus on offline communication due to the strong ties that can be obtained by establishing direct engagement (Penard & Pousing, 2010). Technically, direct involvement is needed for an organisation to have two-way communication with the audiences. As Besette (2004, p. 32) demonstrates, two-way communication and participation is a valuable method of fully engaging with the society directly through dialogue to transform new insight or share new knowledge and even to address the problem.

However, as the growth of technology goes massive, and people are more relying on the internet (Boyd & Ellison, 2007), online communication should also be prioritised in delivering the messages. Since from the total of 265,4 million population of Indonesia, 140 million people are active social media users, dominated by users aged 18-24 years old (Pertiwi, 2018), educating through online communication is necessarily needed to prevent users from believing and sharing hoax news, especially to the young people, who are liable to be attacked by hoax news. This is due to the ironic fact that “young people are fluent in social media, but they were not equally savvy about what they find there” (Piction & Teravainen, 2017, p. 8). Moreover, not all people can access the offline activities conducted by Siberkreasi, so campaigning the messages massively in both online and offline strategy could be effective. As Kitchen (2017, p. 111) points out, integrating both forms offline and online communication is “effective in today’s market”.

The Representation of Instagram Content

To reveal the answer to this research question, we used content analysis. As stated in the method section, eleven variables were chosen to interpret the images/videos on Siberkreasi’s Instagram account. The eleven variables include the theme of the images, how the image is shown, the content of images, the number of likes and comments, the colour used, the persons shown, and lastly, how many times video is watched; because the posts are in the form of images and videos. Total of 223 pictures and videos have been examined from 20th of September 2017 to 30thJune 2018.

We divided the analysis into three sections. Firstly, we analysed the content of the images/videos including theme, content, and what the images/videos about. Secondly, the appearance of the images/videos including colour and forms of the posts were examined. Finally, the last section analysed the engagement of the public in responding to the Instagram post of Siberkreasi.

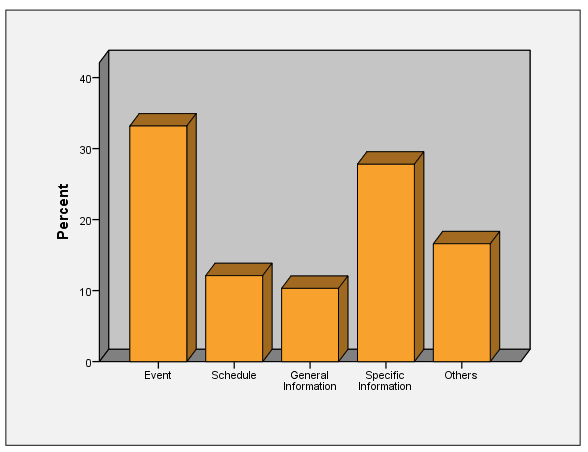

To begin with, we examined the theme of image/video. To answer this question, five possible answers have been determined; 1. event (the variety of offline activities conducted) 2. schedule (Lists of schedules of the upcoming event) 3. general information (e.g. commemoration of the Indonesian big day). 4. specific information (specific content related to MIL understanding and the danger of hoax news). 5. others (photo/video contest, promoting others institutions/communities’ event etc).

This question elaborates on the theme of images and videos showed. Figure 1 reveals that the theme of pictures and videos were dominated by events, with 33.2 % (74 posts), followed by the specific information linked to subject of media literacy 27.8% (62). Schedule and general information topics showed 12.1% (27) and 10.3% (23) respectively, while other themes account for 16.6% (37).

Figure 1: Theme of the images and videos

Moving onto content variables, all the images/videos were dominated by events and schedules with nearly half (45.74%) of the total. This finding placed the educated material linked to subject of media literacy in the second place with 26.91%, meanwhile others and general information content had a less percentage wuth 17.04% and 10.31% respectively. The educated posts linked to MIL are predominantly in the forms of information about the rules to use social media wisely, what kind of post considered as a hate speech, and steps to check information before sprading it. We also crooschecked this information with the interviewees.

This result shows that their Instagram account is mostly used to keep the followers to be informed about their offline activities in other words, to only promote their offline activities. They do not employ the Instagram account thoroughly to teach society, but predominantly to convey their agenda that has been set on their program. In this regard, it can be stated that they employ Instagram mostly to highlight their offline activities, applying Instagram as a marketing tool. This is also reinforced by the interview that Siberkreasi prefer to do offline events such as seminars and workshops to give a more comprehensive understanding. By doing offline campaigns massively, they more focus on teaching the society directly by conducting dialogues all around Indonesia, practising participatory communication. This practice allows sharing information through dialogue and gives new insight for society aiming to improve the understanding or addressing particular issues (Thomas & Mefalopulos, 2009, p. 9). Thus, this action might be chosen by Siberkreasi massively to create direct engagement.

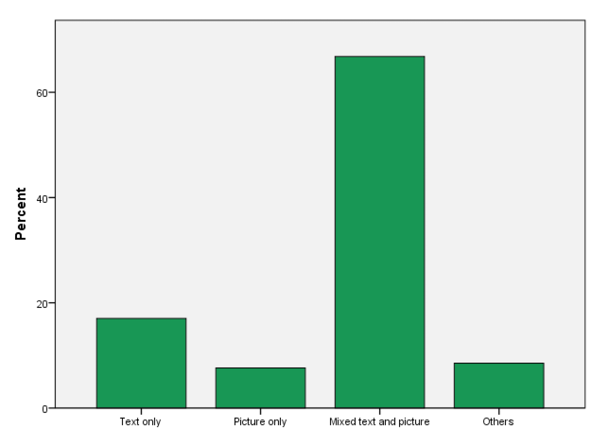

Turning to the appearance of images/videos, first we identified whether the posts are in the form of a text, picture or picture combined with texts.

Figure 2: The bar chart describing how the image is shown

The result shows that they are more likely to combine pictures and texts, with over half of the total percentage (66.8% / 149 posts). Meanwhile, the other three categories (text only, a picture only, and others) are under 20% (17.6%/39 posts, 8.5%/18 posts and 7.6%/17 posts respectively). Using images for delivering the messages is not new for visual communication. Smiciklas (2012, p. 3) mentioned that as infographics “it is a type of picture that blends data with design, help individuals and organisations concisely communicate the message to their audience’. Further, Simiciklas (2012, p. 7) adds that using the infographics help the individual or organisation to deliver their messages ‘physically easier’ to the audience in relating and connecting the information. This is because the brain readily recognises the image quickly. Thus, this technique might be useful for the Siberkreasi to reach the audiences.

The variable of the colour of images/videos posted were dominated by bright colour, with 182 pictures, while dominant black colour also has a relatively high number, with 41 photos of the total. This finding reveals that Siberkreasi Instagram account preferred to employ different colours in sharing their images. This can be analysed that the tone colour of the post is mostly bright, which can depict the salience of the image shown to attract the followers. Machin and Mayr (2012, p. 55) state the more colourful pictures, the more salient it is. The bright colour is often used by the commercial photograph to attract the viewers, and it can depict the aura of the picture itself (Hansen & Machin, 2013, p. 186). Moreover, Machin and Mayr. (2012, p. 55) emphasise that bright colour can attract the eyes; the ‘brighter tones’ is used by advertisers to make the product shiner and more attractive. Therefore, this chosen colour would be useful in terms of attracting the audiences.

The next aspect that we studied is what kind of people pictures posted. The finding shows that none people picture has the largest proportion, with more than half of the percentage, while famous people were positioned second, with 26%, followed by ordinary people with 21.5%. This result reveals that they did not include a person picture in every single Instagram post. This might be due to they are more likely to deliver their messages through texts and other pictures rather than people pictures to include more details of events and programs. However, this might not increase the engagement rates since public figure images might attract more interaction (Thrall, 2008).

To know how they deliver their message, another variable that needs to be examined is the type of language of the images/videos used. The result reveals that they applied more formal language in delivering their message. Formal language accounted for 167 images, with 74.9%, while informal language was used in 57 images (25.6%).

Lastly, the last section examines the engagement of the public in responding to Instagram posts of Siberkreasi. It begins with investigating how many likes that images/videos obtained.

From 223 posts examined, the images/videos mostly obtained under 100 likes. Only 15 images achieved more than 200 likes. It is a small number compared to the number of followers which have reached over eight thousand. The engagement also can be derived from the comments obtained. The result was quite similar to the likes. Most of posts did not generate any comments from the followers, in that from the 223 posts examined nearly half of them did not obtain any comments (98 images), while just five images received over 30 comments. The image posts that acquired most likes and comments contain information about previous events, event schedules, and other general knowledge, while posts linked to MIL obtained less likes and comments.

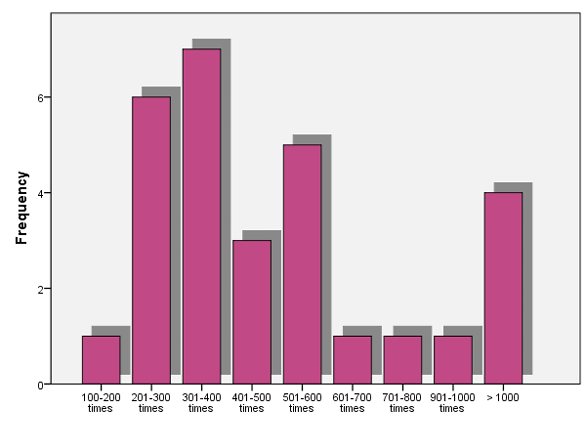

Moving onto the video’s engagement, there were 29 videos posted during the period under study. Figure 3 depicts that most videos (7) obtained 301-400 views, six videos got 201-300 viewers and five videos acquired 501-600. Meanwhile, only four videos were watched by more than 1000 viewers. Different from image posts, most liked and commented vidoes are those containing information related to MIL, despite the small number of viewers, compared to the number of followers.

Figure 3: The bar chart shows the number of viewers of videos

It can be stated that the engagement rate of the followers and the Instagram account is not high. As Bakhshi et al. (2014, p. 967) argued, “the number of likes signals for the extent to which the content is interesting to users, and the number of comments quantifies the level of discussion on the social network”. Considering the number of followers, this contradicts with the previous study that claimed “the greater number of followers, the more people can see the photo, and there is presumably a higher chance of receiving likes and comments” (Bakhshi et al., 2014:968). Thus, this can be stated that the number of followers could not always determine high engagements.

Moreover, the videos posted also reached a small number of viewers. This is again evidence that the followers are reluctant to interact with Siberkreasi’s Instagram. Although it has been stated that the use of Instagram is not the main of strategy to educate the public about MIL, the appearance and content of Instagram should be considered by Siberkreasi since more and more people are connected in the social network site (Boyd and Ellison, 2007). Therefore, it is suggested to utilise social media platforms to educate people about MIL competence to fight against hoax news by posting more creative content, especially videos, related to MIL.

Conclusions

This study aims to examine the communication strategies used by the national movement in Indonesia to teach MIL to the public. The findings show that the offline communication was massively used instead of online communication. They tend to campaign through offline activities to establish direct engagement within society. Although the online communication might assist to reach broader audiences, they believe that direct involvement more gives a comprehensive understanding of MIL skills to the society all over Indonesian regions. This is also reinforced by the result of content analysis of their Instagram content, which shows more offline activities instead of educated content.

The representation of Instagram’s content of Siberkreasi indicates that most of the images/videos showed offline activities or events conducted by Siberkreasi in educating MIL to the society. The educated posts linked to MIL are predominantly in the forms of information on how to use social media wisely, what kind of posts are considered as hate speech, and how to crosscheck information before spreading it.

However, the engagement rate is not high. This can be seen from the number of likes and comments, which does not exceed 300 for likes and 40 for comments. Similarly, the videos posted reached under 600 viewers, while the followers had reached over eight thousand. Thus, it could be stated that there should be an improvement of the content and appearance of their Instagram to increase the engagement of the followers especially, and other audiences generally. This study may contribute to the discussion of the employment of MIL to decrease the spread of fake news in social media, especially in the Asian contexts. However, there are some limitations of this study. This study only focused on the approaches of the organisation to combat the proliferation of hoax news. Thus, it is suggested that the future research could measure how effective the utilisation of offline and online communication strategy to teach MIL competencies in combating hoax news.

References

Abner, et al. (2017). Penyalah Gunaan Informasi Berita Hoax di Media Sosial. Retrieved from: https://mti.binus.ac.id/2017/07/03/penyalahgunaan-informasiberita-hoax-di-media-sosial/

Azali, K. (2017). Fake News and Increased Persecution in Indonesia. ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute, 61, 1–10.

Bakhshi, S., Shamma, D. A., & Gilbert, E. (2014). Faces engage us: Photos with faces attract more likes and comments on instagram. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 965–974). New York: ACM.

Besette, G. (2004). Involving the Community: A Guide to Participatory Development Communication. Penang: International Development Research Centre.

Best, P. and Manktelow, R. & Taylor, B. (2014). Online Communication, Social Media and Adolescent Wellbeing: A Systematic Narative Review. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001

Beullens, K., & Schepers, A. (2013). Display of alcohol use on Facebook: A content analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(7), 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0044

Boyce, C & Neale, P. (2006). Conducting In-Depth Interviews: Guide for Designing and Conducting In-Depth Interviews for Evaluation Input. Massachusetts: Pathfinder International.

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of computer‐mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Breakstone, J., McGrew, S., Smith, M., Ortega, T., & Wineburg, S. (2018). Why we need a new approach to teaching digital literacy. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(6), 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0031721718762419

British Film Institute. (2000). Moving Images in the Classroom: A Secondary Teacher’s Guide to Using Film and Television. London: British Film Institute.

Bruce, C. (1997). The Seven Faces of Information Literacy. Adelaide: Auslib Press

Bryman, A. (2016) Social Research Methods 5th eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buckingham, D. (2006) Defining Digital Literacy; What Do Young People Need to Know About Digital Media? Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, pp. 21–34.

Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., ... & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554–559.

Duncan, S. and Fiske, D.W. (1977). Face-to-face Interaction. London: Routledge

Falkheimer, J. and Heide, M (2018) Strategic Communication an Introduction. Oxon: Routledge.

Frederiksen, L. (2017). Fake news. Public Services Quarterly, 13(2), 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2017.1301231

Geurin-Eagleman, N.A. & Burch, L.M. (2016). Communicating via Photographs: A gendered Analysis of Olympic Athletes’ Visual Self-presentation on Instagram. Sport Management Review, 19(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.03.002

Gilster, P. (1997). Digital Literacy. New York: Wiley Computer Publishing.

Hallahan, K., Holtzhausen, D., Van Ruler, B., Verčič, D., & Sriramesh, K. (2007). Defining strategic communication. International journal of strategic communication, 1(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180701285244

Hansen, A. & Machin, D. (2013). Media and Communication Research Methods. Basingstoke: Palgrave Mcmillan.

Holston, D. (2015). Show Me, Don’t Tell Me: Visualizing Communication Strategy. New York: HOW Books

Inayatillah, F. (2018). Media and Information Literacy (MIL) in journalistic learning: strategies for accurately engaging with information and reporting news. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 296, No. 1, p. 012007). Bristol: IOP Publishing.

Internet World Stats. (2018). Top 20 Countries in Internet Users vs. Rest of The World – December 31, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.internetworldstats.com/top20.htm

Jang, S. M., Geng, T., Li, J. Y. Q., Xia, R., Huang, C. T., Kim, H., & Tang, J. (2018). A computational approach for examining the roots and spreading patterns of fake news: Evolution tree analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.032

Johnson, John M. (2001). In-depth interviewing. In Gubrium, J. F., & Holstein, J. A (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method, (pp. 103–119). London: SAGE

Johnson, J. M., & Rowlands, T. (2012). The interpersonal dynamics of in-depth interviewing. In Gubrium, J. F., Holstein, J. A., Marvasti, A. B., & McKinney, K. D. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft, (pp. 99–113). London: SAGE

Jones, R.H. and Hafner, C.A. (2007). Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Induction. London: Routledge.

Juliawanti, L. (2018, March 14). AngkaPenyebaran Hoax Capai 8000 ribukonten, di pilkada terus Meningkat. IDN Times. Retrieved from: https://news.idntimes.com/indonesia/linda/angka-penyebaran-hoax-capai-800-ribu-konten-di-pilkada-terus-meningkat/full

Kitchen, P. J. (2017). The Complexities of Online/Offline Communications. Journal of Marketing Communications. 23(2), 111–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2017.1282953

Kurniawan, E., Tri M. P. A., Cahyo B. U., Danang J. T. (2019). Using Media Literacy to Prevent the Dangers of Hoaxes and Intolerance among the Students of Universitas Negeri Semarang. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 8(7), 1–13.

Lazer, D. M., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., ... & Schudson, M. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.aao2998

Lin, H. (2007). The Role of Online and Offline Features in Sustaining Virtual Communities: An Empirical Study. Internet Research, 17(2), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240710736997

Machin, D. & Mayr, A. (2012). How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: SAGE.

McGonagle, T. (2017). “Fake news” False fears or real concerns?. Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights, 35(4), 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0924051917738685

Mihailidis, P., & Viotty, S. (2017). Spreadable spectacle in digital culture: Civic expression, fake news, and the role of media literacies in “post-fact” society. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002764217701217

Moore, D., & Dwyer, F. (1994). Visual literacy: A spectrum of visual learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Morris, A. (2015). A Practical Introduction to In-depth Interviewing. London: SAGE

Nelson, J. L., & Taneja, H. (2018). The small, disloyal fake news audience: The role of audience availability in fake news consumption. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3720–3737. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1461444818758715

Paul, C. (2011). Strategic Communication: Origins, Concepts, and Current Debates. New York: Praeger.

Penard, T. & Poussing, N. (2010). Internet Use and Social Capital: The Strength of Virtual Ties. Journal of Economic Issues, 44 (3), 569–595. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEI0021-3624440301

Pertiwi, W. K. (2018, March 1). Riset Ungkap Pola Pemakaian Medsos Orang Indonesia. Kompas News Online. Retrieved from: https://tekno.kompas.com/read/2018/03/01/10340027/riset-ungkap-pola-pemakaian-medsos-orang-indonesia

Picton, I., & Teravainen, A. (2017). Fake news and critical literacy: an evidence review. National Literacy Trust, London, available at: https://literacytrust.org. uk/policy-and-campaigns/all-party-parliamentary-group-literacy/fakenews/ [Google Scholar].

Poynter, R. (2010). The Handbook of Online and Social Media Research: Tools and Techniques for Market Researchers. Sussex: Wiley.

Rubin, V. L., Chen, Y., & Conroy, N. J. (2015). Deception detection for news: three types of fakes. In Proceedings of the 78th ASIS&T Annual Meeting: Information Science with Impact: Research in and for the Community (p. 83). New York: American Society for Information Science.

Salleh, S. M., Shamshudeen, R. I., Abas, W. A. W., & Tamam, E. (2019). Determining media use competencies in media literacy curriculum design for the digital society: A modified 2-wave delphi method. SEARCH (Malaysia), 11(1), 17–36.

Santoso B. and Wardiana, D. (2017) New Media Literacy and Spread Hoaxes: Why It Matters, in Purnomo, E.P. et al. (eds) Social and Political Issues in Asia: The Context of Global Changes (2017), Yogyakarta: Buku Litera Yogyakarta, pp. 29–46.

Silverman and Singer-Vine. (2016, December 6). Most Americans Who See Fake News Believe It, New Survey Says. BuzzFeed News. Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/fake-news-survey

Siniscalco, M. T. (1996). Television literacy: Development and evaluation of a program aimed at enhancing TV news comprehension. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 22(3), 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-491X(96)00012-0

Smiciklas, M. (2012). The Power of Infographics: Using pictures to communicate and connect with your audiences. Indiana US: Que.

Sundar, S. S. (2016, December 8). There’s a psychological reason for the appeal of fake news. New Republic. Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/139230/theres-psychological-reason-appeal-fake-news

Susilawati, D. (2017, April 11). Begini Dampak Berita Hoax. Republika News Online. Retrieved from: http://trendtek.republika.co.id/berita/trendtek/internet/17/04/11/oo7uxj359-begini-dampak-berita-hoax

Tacchini, E., Ballarin, G., Della Vedova, M. L., Moret, S., & de Alfaro, L. (2017). Some like it hoax: Automated fake news detection in social networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.07506.

Thrall, A. T., Lollio-Fakhreddine, J., Berent, J., Donnelly, L., Herrin, W., Paquette, Z., ... & Wyatt, A. (2008). Star power: Celebrity advocacy and the evolution of the public sphere. The international journal of press/politics, 13(4), 362–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208319098

Thomas, T. & Mefalopulos, P. (2009). Participatory Communication: A Practical Guide. Washington D.C: The World Bank.

Waheed, M. (2019). Online threats and risky behaviour from the perspective of malaysian youths. SEARCH (Malaysia), 11(2), 57–71.

Wijaya, N. P. N. P. and Mohd H. M. S. (2019). Analysis of Student Perception in Responding To the Hoax New. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 6(6), 159–164.

Wood, A. F. & Smith, M. J. (2001). Online Communication: Linking Technology, Identity, and Culture. New York: Psychology Press.