Informacijos mokslai ISSN 1392-0561 eISSN 1392-1487

2020, vol. 90, pp. 42–52 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2020.90.49

Coverage of Events After Maidan Protests and the Annexation of Crimea in Local Russian-Language Newspapers in Lithuania (March, 2014)

Viktor Denisenko

Vilnius University, Faculty of Communication

Vilniaus universitetas, Komunikacijos fakultetas

E-mail: viktor.denisenko@kf.vu.lt

Abstract. In 2014, some significant geopolitical changes in the region of Central and Eastern Europe took place. After the so-called Euromaidan events in Ukraine, Moscow took advantage of the situation and annexed the Crimean peninsula. The global agenda was dominated by the discussions about “hybrid war”, “information warfare,” etc. It was obvious that the Kremlin used propaganda in its operation in Crimea in order to manipulate the public opinion and to include ethnic minorities (Russian-speaking inhabitants of Crimea) into its games.

In the above context of Kremlin’s practice of involving compatriots from near abroad (including Lithuania) into geopolitical processes, as well as facing the challenge of propaganda, it is important to look how the events in Ukraine were covered in the Russian-language newspapers in Lithuania. The materials of research become publications in the weeklies “Litovskij kurjer”, “Obzor”, and “Ekspress-nedelia”. The question of the research was: did these newspapers use narratives of the Kremlin propaganda, and if so, how strong was the representation of these narratives?

Keywords: propaganda, hybrid war, national minorities, media, Russian Federation, Lithuania

Po Maidano protestų sekusių įvykių ir Krymo aneksijos pateikimas vietiniuose laikraščiuose rusų kalba Lietuvoje (2014 m., kovas)

Santrauka. 2014 metais Centrinės ir Rytų Europos regione įvyko reikšmingi geopolitiniai pokyčiai. Po vadinamųjų Maidano įvykių Ukrainoje Maskva pasinaudojo situacija ir aneksavo Krymo pusiasalį. Šia įvykiai paskatino moksliniame ir ekspertiniame pasaulyje atnaujinti aktyvesnes diskusijas apie tokius reiškinius kaip „informacinis karas“, „hibridinis karas“ ir pan. Buvo pastebėta, jog vykdydamas operaciją Kryme Kremlius aktyviai naudojo propagandos priemones, siekdamas manipuliuoti vietinių gyventojų nuomone bei savotiškai įtraukdamas rusakalbius Krymo gyventojus į savo žaidimą.

Suprantant šiuolaikinės Kremliaus propagandos keliamą pavojų, kaip ir bandymą įtraukti užsienyje (taip pat ir Lietuvoje) gyvenančius tėvynainius į tam tikrus geopolitinius procesus, verta išanalizuoti, kokiu būdu Krymo aneksijos įvykiai buvo pateikti vietinėje rusakalbėje spaudoje Lietuvoje. Tyrimo objektu tapo rusakalbiai savaitraščiai „Litovskij kurjer“, „Obzor“ ir „Ekspress-nedelia“. Tyrimo metu buvo siekta nustatyti, ar minėtų įvykių pateikime buvo naudojami atitinkami Kremliaus propagandos naratyvai? Taip pat buvo siekta nustatyti, kiek plačiai tokio pobūdžio naratyvai buvo atspindėti vietinės rusakalbės spaudos publikacijose.

Raktiniai žodžiai: propaganda, hibridinis karas, tautinės mažumos, žiniasklaida, Rusijos Federacija, Lietuva

Received: 06/05/2020. Accepted: 18/05/2020

Copyright © 2020 Viktor Denisenko. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The Revolution of Dignity in Kiev and Russia’s reaction to it (annexation of Crimea, support of separatists in the Donbass region) changed the geopolitical situation in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The 2013-14 events became a point of critical changes in the post-Soviet area. Russia demonstrated its readiness to fight for the zone of influence not only verbally, but also practically.

The Euromaidan events in Ukraine were a signal not only for Kiev. The revival of imperial ambitions in the Russian Federation changed security situation in the entire CEE region. These changes were quite predictable. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Moscow shows a special attention to the post-Soviet area and countries of a former communist block (Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, etc). The post-Soviet space has been of particular importance for the Russian authorities, since Moscow perceives this region as the sphere of its direct geopolitical influence.

The Baltic States form an exception from this geopolitical status quo. Occupied and incorporated in the Soviet Union in 1940, these republics were perceived rather as “aliens” (Laurinavičius, Motieka, Statkus, 2005). There was a wide-scale resistance movement in the Baltic States against the Soviet occupation during and after the World War II (1944-1953). Later, under the Soviet rule, the societies of the Baltic States strove to preserve their identities and hoped to reclaim freedom. For instance, Lithuania was the first among the Soviet republics to declare the re-establishment of its Independence on 11 March 1990.

Similarly to Estonia and Latvia, independent Lithuania opted for integration into the Western structures. This choice disregarded the position of Russia. Its authorities were in fact quite unhappy with the developments in the Baltic States, but “allowed” them to join the European Union and the NATO in 2004 when the confrontation between Russia and the so-called “West” was quite low. However, the accession of the Baltic States in these Western alliances did not mean that Russia withdrew its ambitions to have geopolitical control over these three countries. Therefore, Lithuania remains among the countries which Russian authorities would like to see as the area of their geopolitical influence.

Lithuania in the orbit of Russia’s influence

Lithuania and the Russian Federation belong to different geopolitical areas. Moscow lives in the realm of its new imperial illusions. Lithuania joined the European Union and the NATO and has established itself as an integral part of the political “West”. It does not mean that Moscow supports the Lithuanian decision about choosing its geopolitical allies. For example, before Lithuania’s accession to the NATO, Russia had tried to scuttle the idea of the Baltic States integrating in this organization (Martišius, 2010, p. 137).

Scholars stress different types of Russian influence in Lithuania. Organized and objective influence is transmitted through Russia’s foreign policy and soft power. Vitkus (2006, p. 49) defines the following domains of this influence:

• Accusation of the violation the rights of the Russian-speaking minorities1

• Support of the so-called “compatriots”2

• Cultural dimension

• Education dimension

• Russian media

Russia tries to keep Lithuania in its zone of geopolitical influence. Before 2014, the main strategy of Moscow was to use the area of foreign affairs and soft power to “control” Lithuania as well as Latvia and Estonia. Russia tried to prove that the Baltic States are “not democratic” countries and stress that Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia violated the rights of their Russian-speaking minorities. Th core of this strategy was to segregate the Baltic States from the Western World and to provoke mistrust between them and their partners in Europe.

The strategy of soft power means that Russia tries to keep its influence in the area of humanitarian dimension. For it, Moscow used historically established ties. In fact, “Russia has a competitive advantage for its humanitarian policies in the post-Soviet sphere due to objective reasons: Russian compatriots living in this region, the popularity of Russian mass culture, and the spread of Russian Orthodox Christianity” (Pelnens (ed), 2009, p. 203).

The Kremlin developed a concept of the “Russian World” for own soft power needs. Unlike the conception of compatriots, the “Russian World” definition is not enshrined in the law and provide opportunities for broad interpretation by every actor. In fact, this is an exterritorial concept which united all Russian-speaking people (compatriots) beyond the borders of the Russian Federation (Tishkov, 2007). As Nerijus Maliukevicius noticed, “the Russian World as an ideology for Russian soft power has a huge potential because of its positive integrating capacity as opposed to the traditional anti-Western rhetoric” (Maliukevičius, 2013, p. 80).

However, in 2014, the situation changed dramatically. The aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine embodied in the annexation of the Crimean peninsula and support of the separatists in the Donbas region showed that the ”Russian World” is the not only a soft power concept. Russia used this concept in its hybrid warfare operation in Ukraine. After that the “Russian World” become a marker of threat. In the Ukrainian context, Russia put the “Russian World” as an alternative to the “Euromaidan” (Shulga, 2015, p. 235). Moscow explained its aggression against Ukraine in terms of necessity to defend its compatriots, i.e. representatives of the “Russian World”.

Russia uses the concept of Russian World globally. After 2014 Russia’s soft power changed towards much more open information and propaganda warfare. Lithuania and the Baltic States in general were the first countries of the political “West” affected by it. The growing threat of Russia’s activities in 2014 was mentioned inter alia by the State Security Department of Lithuania in its annual public report (VSD, 2014, p. 9-10).

It is obvious that Moscow could try to use the hybrid warfare strategy not only against Ukraine but also against other countries in its immediate neighborhood. Lithuania potentially belongs to the zone of the risk. Therefore, it is important to evaluate possible threats. For this purpose, the lessons of Crimea should be analyzed.

The lessons of Crimea

The annexation of Crimea gives many lessons pertinent to information warfare. Russia organized a broad informational support of its aggression against Ukraine. Russia’s main goal of was to camouflage the real armed aggression in Ukraine.

One can distinguish three stages of Russia’s operation against Ukraine.

The first stage is linked with the reaction of Russia’s authorities to the Euromaidan events in Kiev. Moscow tried to be an actor in the Ukrainian agenda. It was a question of geopolitical influence in the neighboring country. For this purpose the Kremlin tried to use all leverages it had. According to Darczewska (2014, p. 5) Russia’s activities in Ukraine during the Euromaidan times were “combined with ideological, political and socio-cultural sabotage, provocation and diplomatic activity”. The main goal of the Kremlin was to keep the “pro-Russian” and controllable Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych in power.

Some commentators believe that the Kremlin could have different strategies in Ukrainian situation. For instance, Edward Lucas and Peter Pomeranzev (2016, p. 15) suggest:

By associating the pro-democracy movement in Ukraine with fascism and an anti-Russian, Western-backed coup, Russia hopes to galvanize its own domestic audience behind its assertive foreign policy. Similarly, it hopes to radicalize potential supporters in eastern and southern Ukraine to bolster its military campaign there. Finally, Russia hopes to discredit the Ukrainian government in the eyes of Europe and NATO.

However, after Yanukovych’s escape the situation significantly changed. At this second stage the Kremlin understood that it was about to lose a battle in Kiev. This, however, provided Russia with new geopolitical opportunities. One of these opportunities was to organize the annexation of Crimea. In fact, Russian authorities used the Euromaidan context for their own purposes. As Cepuritis (2015, p. 149) concludes, “Euromaidan protests turned to riots, and riots turned to tragedy, creating the perfect moment for Russia to annex Crimea and escalate military hostilities in Eastern parts of Ukraine”.

In Crimea, Moscow showed a new strategy, which quite soon was named a “hybrid warfare” (Ibid, p. 152). This strategy could be explained as the combination of information and disinformation campaigns used together with (camouflaged) military actions. Hence, to justify the annexation of Crimea, Russia used a series of absurd propaganda narratives, such as “Banderivtsy could storm into Crimea”, “the Black Sea Fleet bases could be taken over by NATO”, or “Ukrainian citizens could be de-Russified” (Darczewska, 2014, p. 5).

The third stage was a strategy to entrench the fact of annexation. For the domestic audience, the Kremlin used the traditional “fear of the West” in a broad historical context. According to Darczewska, (2016, p. 32), “[s]ince the “Orange Revolution” in Ukraine in 2003/4, Russia has been exploiting ever more intensively the threats stemming from the “export of Western democracy”, and today it insists on presenting its armed interventions in Crimea and Donbas as a kind of liberation mission aimed at freeing Ukraine from US dominance”.

For the foreign audience, another version was used. The Kremlin tried to promote its own “truth.” The so-called Crimean referendum held on 16 March 2014 was used as the argument to legitimize the aggression (Berzins, 2015, p. 43). As Lucas and Nummo (2015, p. 13) underline, “even if Western audiences only come to believe that there are two sides to the story – say, on Russia’s aggression in Ukraine – then the Kremlin has already won an important victory”.

Information manipulation aimed at the local population was another important aspect of the “hybrid warfare” usage in Crimea. As Darczewska (2016, p. 6) explains:

The Crimean operation perfectly shows the essence of information warfare: the victim of the aggression – as was the case with Crimea – does not resist it. This happened because Russian-speaking citizens of Ukraine who had undergone necessary psychological and informational treatment (intoxication) took part in the separatist coup and the annexation of Crimea by Russia.

It also could explain the impulsive decision made by Moscow. As Latvian researcher Andis Kudors (Kudors, 2015, p. 167) observed: “It is possible the decision to annex Crimea was made suddenly by the Kremlin, however, Russian compatriots’ organisations in Ukraine had been preparing for the possibility of such a step for a number of years already” .

Russian media have also played a significant role in information warfare against Ukraine in 2014 and later. It was the main channel of influence for the local Russian-speaking population in Crimea. Some commentators argue that “in Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine, media play the principal role” (Ibid, p. 164). Hence, it was a tool used for destabilization of the situation in Ukraine (Darczewska, 2014, p. 6).

It also important to mention that Moscow did not stop after Crimea. It is obvious that “spurred on by the Crimean success, the Russian leadership then embarked on the Donbas adventure” (Kažocinš, 2015, p. 54). The confrontation between the Ukrainian state forces and the so-called separatists supported by Russia in the Eastern part of Ukraine still have no solution.

The main lesson of the Crimean events is that Russia is ready to cross the “red lines” in foreign affairs and geopolitical domain. It means that none of the neighboring states could feel safe in the Russia’s vicinity. This poses the actual challenge not only for Lithuania but also for other Baltic States because “similar Russian media and “compatriots” policy methods used in Ukraine before and after the annexation of Crimea, are also used in the Baltic States” (Kudors, 2015, p. 168).

Scholars stress that success of the Crimean annexation could inspire Russian officials to new geopolitical adventures. Lithuania and other Baltic States belong to the immediate risk zone, because “it might tempt President Putin to use his doctrine of protecting ethnic Russians and Russian speakers in seeking territorial changes elsewhere in the neighborhood, including in the Baltic States, provoking a direct challenge to NATO” (Daadler etc, 2015, p. 5).

It means that all types of Russian information activities in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia should be analyzed, including the coverage of the Euromaidan events in Ukraine and the subsequent annexation of Crimea in local Russian-language newspapers in Lithuania. This research is important as it addresses the issues of information security and Moscow’s possibility to appeal to the Russian-speaking minorities for support of Russian geopolitical capers. This is particularly important because Russian turned Russian language into the tool of its geopolitical influence on the post-Soviet area (Oledzka, 2017).

The coverage of Ukrainian events in March 2014

The scope of the Russian-language press in Lithuania is quite small. There are three main nation-wide weekly newspapers well-known among the readers since the 1990s: “Litovskij kurjer” (“Lithuanian courier”), “Obzor” (“Overview”), “Ekspress-nedelia” (“Express-week”). These three publications are the main print media for Russian-speaking community in Lithuania.

The annexation of Crimea was the main media topic in March 2014. The Russian-language press could not ignore these events as well. Thus, the main point of the research was to answer the question: how did the Russian-language newspapers of Lithuania cover the annexation of Crimea?

The methods of the research were a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the documents (articles). The quantitative part of the research allowed to determine aspects of coverage of chosen events in the agenda of Russian-language newspapers in Lithuania. Qualitative analysis of the texts allowed to explore links of the content of published articles to one or another version of events (i.e., from the side of Russia, from the side of Ukraine etc.) as well as links to narratives of the Kremlin propaganda.

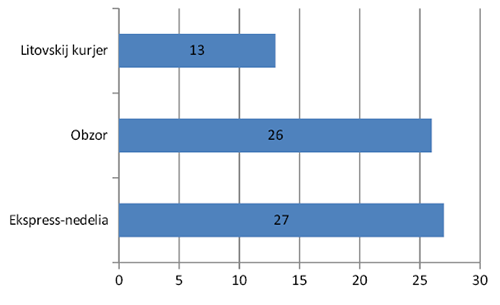

Twelve issues of the newspapers, in which 66 texts3 about Ukrainian events were found (see Table 1), were analyzed. The number of publications in the three titles was distributed as follows: Ekspress-nedelia” (27 texts), followed by “Obzor” (26 texts) and “Litovskij kurjer” with only half as much as two other newspapers (13 texts).

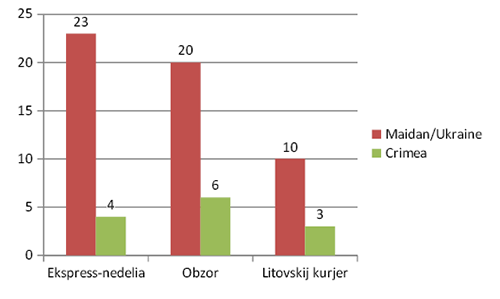

In the research attention was focused on the question whether publications covered the Ukrainian events in general, or specifically focused on the Crimean events? This aspect is particularly important if we focus on the chronological development of the situation. In March 2014, the Euromaidan protests were already over. The protesters won, but the power in the country lacked stability. Thus, this factor was used by Russia in its activities aimed at the annexation of Crimea. One can assume that the news about Crimea should dominate in the agenda of the media during this period. However, we can observe that the Russian-language newspapers in Lithuania prefer to write about Ukraine in general, while the Crimean events drew significantly less attention (see Figure 2). In fact, a similar trend can be observed in both “Obzor” and “Litovskij kurjer” (1/3 about Crimea v. 2/3 about the entire Ukraine), while in the case of “Ekspress-nedelia” there was a much more “careful”4 proportion.

Fig. 1. All articles about Ukrainian events during research

Source: research data

Fig. 2. Proportion of publications about Euromaidan/Ukraine events and the Crimean events

Source: research data

The research primarily strove to answer the question of which position the newspapers transmitted while covering these events. The main professional principle for journalists and publishers is to try to be as much objective as possible.

As for the Ukrainian events (including those in Crimea), one could observe least two positions. The first one was the official position of Ukraine, formed by the Ukrainian parliament after Yanukovych’s escape. In fact, this position was supported by Europe and Lithuania. Vilnius recognized the new Ukrainian government, and the win of the Euromaidan was interpreted as the victory of democracy.

The second position was the position of the Russian Federation. In fact, it was clearly reflected by the propaganda narratives which the Kremlin used during the period. Russians argued that the events in Kyiv were in fact a coup. They portrayed the protests as not peaceful and headed by “Nazis”, “Nationalists” and “Banderovtsy” (Ukrainian nationalists, followers of the ideas of Stepan Bandera). Russia claimed that the new government was illegal and still acknowledged Viktor Yanukovych as a legitimate president.

Similar differences could be observed in positions pertinent to the Crimean events. Ukraine insisted on the fact of Russia’s invasion and annexation of the peninsula. Lithuania (as all the political “West”) also supported this interpretation of events.

Moscow tried to mask own steps and actions. Russia denied the activities of its its armed forces in the Crimean peninsula. The annexation of Crimea was presented as “a free choice” of its inhabitants.

Additionally, we observe the third professional position of the media, when it represented different points of view or just the objective facts. This position could be as either “Objective”, or “Neutral”.

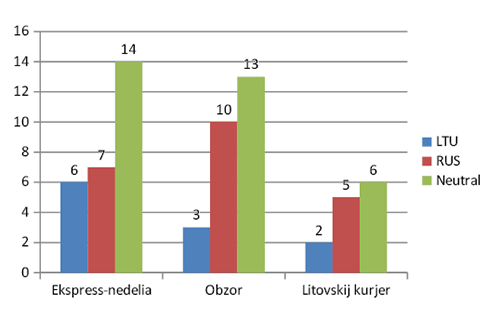

Figure 3 shows the distribution of these positions in the publications of the three Lithuanian Russian-language newspapers during the period in question.

Fig. 3. Representation of different positions in publications

Source: research data

It could be seen that all newspapers tried to comply with the principles of objectivity and neutrality5. However, it seems interesting to focus on the correlation between the numbers of publications which represented different positions. Only in the “Ekspress-nedelia” the Lithuanian (i.e. Ukrainian) and the Russian positions were presented in equal proportion. In other two newspapers the Kremlin position prevailed.

The research also showed that during the period in question the newspapers transmitted the narratives used by the Kremlin propaganda against Ukraine. The messages of these narratives and their distribution between the three newspapers in question are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. The Kremlin’s propaganda narratives, presented in the newspapers

|

Narrative |

Ekspress-nedelia |

Obzor |

Litovskij kurjer |

|

Only Yanukovych is a legitimate president |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Anti-constitutional coup in Ukraine |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

The “Right Sector” (as main hostile power at Euromaidan) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

The Russian army doesn’t act in Crimea |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Protesters at Euromaidan uses nationalistic Bandera’s ideology |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Protesters at Euromaidan are extremists and radicals |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Euromaidan events is fault of EU |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Nationalists and neo-Nazis at the Euromaidan |

+ |

|

+ |

|

Antisemitism of the Euromaidan protesters |

+ |

|

+ |

|

Protesters at the Euromaidan use “Nazi/SS” slogans |

|

|

+ |

|

People get payed for participation in the Euromaidan protests |

|

+ |

|

|

Snipers provoked the Euromaidan protesters |

|

+ |

|

|

Nationalists in Ukraine will attack/fight against the representatives of Russian (Russian-speaking) minority |

|

+ |

|

|

Kiev could not handle the threat of ultra-nationalists |

|

+ |

|

|

In Kiev new oligarchic regime emerges |

|

+ |

|

|

Referendum in Crimea is legal and democratic |

|

+ |

|

This information can be seen as a certain ranking of the Kremlin propaganda narratives, used in Lithuanian Russian-language newspapers in the context of the Ukrainian events. The most popular narratives, repeated in all three newspapers emphasized that “only Yanukovych was a legitimate president”, that the “anti-constitutional coup” was taking place in Kiev, whereas the Ukrainian patriotic “Right Sector” movement was portrayed as the “main hostile power in the Euromaidan”. Moreover, publications in all the newspapers claimed that “the Russian army did not act in Crimea”.

Another type of the Kremlin propaganda narratives became quite popular. Two of the three newspapers reported about the alleged “Nationalism”, “Nazism” and “Antisemitism” among the Euromaidan protesters. The publications “explained” that the street protesters used “Bandera’s ideology”, that they are “extremists and radicals”, and even that all the Euromaidan events are, in fact, “the fault of the European Union”.

The texts by the Obzor contain more examples of the Kremlin propaganda. For example, its authors wrote that “people got paid for participation in the Maidan protests” and even that it was not “Berkut” snipers who shot to the protesters, but unknown snipers from the Euromaidan side.

Conclusions

In its hybrid war against Ukraine in 2014, Russia used a broad variety of information aggression tools and propaganda techniques. The reflections of these activities could be found in the Russian-language newspapers in Lithuania. The results of this research demonstrated that:

1. The local Russian-language newspapers showed wired attention to general Ukrainian events in 2014, whereas the events in Crimea drew much less attention.

2. All the newspapers in question tried to create an illusion of objectivity and balance in providing their readers with information. However, a rather balanced coverage of the Ukrainian events could be observed only in the “Ekspress-nedelia”

3. All the newspapers were, in fact, providers of the Kremlin propaganda narratives used against Ukraine in its hybrid war. The research identified 16 types of these narratives. Seven narratives were presented in the “Litovskij kurjer,” nine – in the “Ekspress-nedelia”, and 13 in the “Obzor”.

4. The coverage of the Ukrainian events puts these newspapers as a potential factor of risk in the context of state’s (information) security and stability. On the one hand, their publications demonstrated lack of informational loyalty to Lithuania and orientation towards Russian information space. On the one hand, they showed a possibility of exerting influence on the Russian-speaking minority groups in Lithuania.

References

Cepuritis, M. (2015). Revision of the European Union’s Eastern Partnership After Russia’s Aggression Against Ukraine, in Pabriks, A.; Kudors, A. (Ed). The War in Ukraine: Lessons for Europe. Riga: The Center for East European Policy Studies, University of Latvia Press, 146–157.

Daadler, I.; Flournoy, M.; Hrbst, J.; Lodal, J.; Pifer, S.; Stavridis, J.; Talbott, S.; Wald, C. (2015) Preserving Ukraine’s Independence, Resisting Russian Agression: What the United States and NATO Must Do. Washington: Published by Atlantic Council. Access through Internet: <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/UkraineReport_February2015_FINAL.pdf>

Darczewska, J. (2014). The Anatomy of Russian Information Warfare. Point of view, No. 42. Access through Internet: <https://www.osw.waw.pl/sites/default/files/the_anatomy_of_russian_information_warfare.pdf>

Darczewska, J. (2016). Russia’s Armed Forces in the Information War Frond. Strategic Documents. OSW Studies, No. 57. Access through Internet: <https://www.osw.waw.pl/sites/default/files/prace_57_ang_russias_armed_forces_net.pdf>

Federalnyj zakon… 1999 (2002). Federalnyj zakon ot 24.05.1999 g. Nr. 99-FZ o gosudarstvennoj politike Rossijskoj Federacii v otnoshenii sootechestvennikov za rubezhom [Federal Law of the Russian Federation of May 24, 1999 No. 99-FZ About State Policy of the Russian Federation concerning compatriots abroad]. Access through Internet: <http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/13875>

Jakniūnaite, D. (2007). Kur prasideda ir baigiasi Rusija: kaimynystė tarptautinėje politikoje [Where Russia Begins and Ends: Neighbourhood in International Politics]. Vilnius: VU leidykla.

Kažocinš, J. (2015). Baltic Security in the Shadow of Ukraine’s War, in the Baltic States, in Pabriks, A.; Kudors, A. (Ed). The War in Ukraine: Lessons for Europe. Riga: The Center for East European Policy Studies, University of Latvia Press, 52–67.

Kudors, A. (2015). Reinventing Views to the Russian Media and Compatriot Policy in the Baltic States, in Pabriks, A.; Kudors, A. (Ed). The War in Ukraine: Lessons for Europe. Riga: The Center for East European Policy Studies, University of Latvia Press, 157–175.

Laurinavičius, Č.; Motieka, E.; Statkus, N. (2005). Baltijos valstybių geopolitikos bruožai. XX amžius [The Baltic States in the Twentieth Century: A Geopolitical Sketch]. Vilnius: LII leidykla.

Lucas, E.; Nimmo, B. (2015). Information Warfare: What Is It and How to Win It? CEPA Infowar Paper No. 1. Access through Internet: <http://cepa.org/sites/default/files/Infowar%20Report.pdf>

Lucas, E.; Pomeranzev, P. (2016). Winning the Information War. Techniques and Counter-strategies to Russian Propaganda in Central and Eastern Europe. CEPA. Access through Internet: <http://cepa.org/reports/winning-the-Information-War>

Maliukevičius, N. (2013). (Re)Constructing Russian Soft Power in Post-Soviet Region. Agora, 2: 61–87.

Martišius, M. (2010). (Ne)akivaizdus karas. Nagrinėjant informacinį karą [(Not)obvious war. Information war study]. Vilnius; Versus Aureus.

Oledzka, J. (2017). Russian Language as a Tool of Geopolitical Influence. Yearbook of the Institute of East-Central Europe, No. 3 (15): 135–165.

Pelnens, G. (Ed). (2009). The “Humanitarian Dimension” of Russian Foreign Policy Toward Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, ant the Baltic States. Riga: CEEPS.

Randall, D. (2011). The Universal Journalist, Fourth Edition. London: Pluto Press.

Shulga, O. (2015). Consequences of the Maidan: War of Symbols, Real War and Nation Building, in Ukraine after the Euromaidan: challenges and hopes. Bern: Peter Lang.

Tishkov, V. (2007). Russkij mir: smysl i strategii [The Russian World: meaning and strategies]. Strategija Rossii: No. 7. Access through Internet: <http://sr.fondedin.ru/new/fullnews_arch_to.php?subaction=showfull&id=1185274651&archive=1185275035>

Vitkus, G. (2006). Diplomatinė aporija: tarptautinė Lietuvos ir Rusijos santykių normalizavimo perspektyva [The Diplomatic Aporia: the International Perspective of Normalization of Relations Between Lithuania and Russia]. Vilnius: VU leidykla.

VSD. (2014). Grėsmių nacionaliniam saugumui vertinimas [The Evaluation of Threats for National Security]. State Security Department. Access through Internet: <https://www.vsd.lt/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Gresmiu-vertinimas-2013.pdf>

1 In fact, here we are talking not about an ethnic minority but about a minority with common tradition and experience, dependent of mother tongue. As Justyna Oledzka wrote: “Language is the basis for enabling the creation of a common group of a people’s history, religion and traditions. Through it, a mentality and axiology common to the members of the group is created, which enables them to integrate into specific social structures” (Oledzka, 2017, p. 138).

2 The compatriots is the definition from Federal low of the Russian Federation. By the law, compatriots are “ the citizens of the Russian Federation who are constantly living outside the territory of the Russian Federation ”, and also “the people which are historically living in the territory of the Russian Federation are also recognized and also persons who made free choice for benefit of spiritual, cultural and legal bond with the Russian Federation, whose relatives on the direct ascending line lived in the territory of the Russian Federation earlier” including former citizens of USSR (Federalnyj zakon…, 1999 (2002)). Lithuanian scholar Dovile Jakniuniene explained that “compatriots” are a group of people who identify themselves with the Russian Federation as state and the cultural idea, but not with Russia’s current territory (Jakniunaite, 2007, p. 147). Russian language is the main distinctive marker of this group.

3 The subject of analysis becomes all publications (informational articles, analytical articles, opinion columns, interviews) which match the topic.

4 “Careful” means here that if the Euromaidan events are be interpreted in different ways and depicted as controversial,- it is could be much more difficult to provide similar interpretation of the Crimean events. The Kremlin’s version of the events just confirmed that Moscow obviously lied. Under such circumstances, it was not comfortable for the Russian-languages newspapers in Lithuania to transmit the Kremlin’s view of the Crimean events. This could explain a little attention to it.

5 The objectivity and neutrality is difficult conceptions for research because opens the way for some bias depended on subjectivity of researcher. The “objectivity” understood here as obligation of journalist to “attempt to find out what really happened” (Randall, 2011, p. 148), and non-objectivity interpreted as act of providing false (fake) information and narratives of Kremlin propaganda.