Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2024, vol. 99, pp. 185–202 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2024.99.10

The Role of Public Figures amidst Indonesia’s Early Social Restrictions Policy on Twitter (X): A Social Network Analysis

Tatak Setiadi

State University of Surabaya, Indonesia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6229-4708

https://ror.org/01jf74q70

Eko Pamuji

State University of Surabaya, Indonesia

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-3884-0240

https://ror.org/01jf74q70

Abstract. The Government of Indonesia implemented large-scale social restrictions (Indonesian: Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar, abbreviated as PSBB) following the first confirmed cases of COVID-19. Due to social media role in information propagation, this decision quickly became a trending topic on Twitter. This study investigates the main actors and the dynamics of these discussions surrounding PSBB. Utilizing RStudio software, tweets containing the keyword „psbb“ and the hashtag #psbb were mined as of May 6, 2020. The data were analyzed and compared with research conducted during May 2020. Key findings include the significant role of the musician Fiersa Besari in shaping discussions about social restrictions, the emergence of seven major opinion leaders, and the prominence of online news outlets like detikcom and CNN Indonesia in the conversation. Additionally, the study highlights critical commentary from actors affiliated with the Democratic Faction of the Indonesian House of Representatives regarding the government‘s social restrictions policies. These findings provide insights into the network dynamics and public opinion on social restrictions during the early social restrictions policy in Indonesia.

Keywords: Centrality; COVID-19; PSBB; Public Opinion; Social Restrictions

Viešųjų asmenų vaidmuo Indonezijos ankstyvosios socialinių apribojimų politikos „Twitter“ (X) kontekste: socialinio tinklo analizė

Santrauka. Indonezijos vyriausybė įgyvendino plataus masto socialinius apribojimus (indonezietiškai: Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar, sutrumpintai PSBB) po pirmųjų patvirtintų COVID-19 atvejų. Dėl socialinių medijų vaidmens skleidžiant informaciją šis sprendimas greitai tapo populiariausia tema „Twitter“ tinkle. Šiame tyrime nagrinėjami pagrindiniai šių diskusijų, susijusių su PSBB, dalyviai ir dinamika. Naudojant „RStudio“ programinę įrangą, 2020 m. gegužės 6 d. buvo išgauti „Twitter“ įrašai su raktažodžiu „psbb“ ir grotažyme #psbb. Duomenys buvo analizuojami ir lyginami su tyrimais, atliktais 2020 m. gegužės mėn. Pagrindinės išvados: svarbus muzikanto Fiersos Besari vaidmuo formuojant diskusijas apie socialinius apribojimus, septynių pagrindinių nuomonių lyderių atsiradimas ir internetinių naujienų portalų, tokių kaip detikcom ir CNN Indonesia, svarba diskusijose. Be to, tyrime atkreipiamas dėmesys į kritiškus su Indonezijos atstovų rūmų Demokratų frakcija susijusių veikėjų komentarus apie vyriausybės vykdomą socialinių apribojimų politiką. Šios išvados suteikia įžvalgų apie tinklo dinamiką ir visuomenės nuomonę apie socialinius apribojimus ankstyvuoju socialinių apribojimų politikos Indonezijoje laikotarpiu.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: centralizacija; COVID-19; PSBB; viešoji nuomonė; socialiniai apribojimai

Received: 2022-12-08. Accepted: 2024-09-17.

Copyright © 2024 Tatak Setiadi, Eko Pamuji. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Public opinion and its consumption in popular media have been a topic of growing interest (Anderson & Turgeon, 2023). T his fascination stretches back centuries, from the invention of the printing press in the 17th and 18th centuries to today‘s advanced communication technologies. Despite these advancements, the core concept of widely shared ideas and opinions transcending geographical and political borders remains remarkably constant. The rise of public opinion polling in the 1930s, pioneered by Gallup‘s work, further run this interest. This research method quickly gained traction among market researchers, government and political figures, and academics alike. This surge in interest led to the formation of organizations like the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) and the World Association of Public Opinion Research (WAPOR). These organizations have played a crucial role in developing and refining survey methodologies, including mail, in-person, telephone, and now, internet surveys.

Public opinion is a cornerstone of policymaking in democracies, as highlighted by Glynn et al. (cited in Anderson & Turgeon, 2023). It reflects a nation‘s cultural values, providing valuable insights for effective policies. This is particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the global fight against the virus, different regions implemented varied policies, such as lockdowns, crowd restrictions, mask mandates, and even vaccine passports.

Although people, as mentioned by Burnell et al. (2021), are generally being poor reporters when using social media, in today‘s information age, social media platforms become breeding grounds for crises communication, disaster, public discourse, and several policy issues (Wang, 2014; Yoo et al., 2016; Kim, J. & Hastak, M., 2018). For instance Twitter, established in 2011, is the second-largest social media platform after Facebook (Bruns, 2011). Notably, Indonesia boasted over six million Twitter users by January 2019. Twitter‘s user-friendly features, like hashtags (#), facilitate discussion and discovery. Hashtags allow users to categorize tweets by topic, enabling rapid issue propagation when netizens employ them. Netizens can easily follow specific topics by adding hashtags to keywords (Bekafigo & McBride, 2013; Xiao, Noro, & Tokuda, 2012; Muda, 2015).

In May 2020, the world, including Indonesia, was grappling with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus causing COVID-19. The disease, primarily affecting the respiratory system, was believed to have originated in Wuhan, China, around November or December 2019. The World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed China‘s report of the first COVID-19 case on December 31st, 2019 (WHO Statement, 2020). Three months later, Indonesia reported its first COVID-19 case in Jakarta. Two Indonesian citizens who had recently travelled to Indonesia and come into close contact with Malaysian-Japanese individuals tested positive (Nuraini, 2020). This discovery triggered contact tracing efforts, which ultimately led to wider restrictions on movement, culminating in a national social restrictions policy.

By May 8th, 2020, WHO data revealed a grim picture over 3.7 million confirmed COVID-19 cases globally, with over 259,000 deaths. Indonesia, with over 13,000 confirmed cases, 943 deaths, and 2,494 recoveries at the time (COVID-19 National Task Force, 2020), faced a growing challenge. In response, the COVID-19 National Task Force urged the government to implement effective control measures. This led to Presidential Decree No. 7 of 2020 establishing a COVID-19 Task Force under the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB). Subsequently, the government issued Decree No. 21 of 2020, enacting a National Social Restrictions Policy (PSBB), a partial lockdown requiring closures of offices, schools, places of worship, and public spaces.

The COVID-19 outbreak significantly impacted various aspects of Indonesian life, including politics, economy, society, culture, security, and national well-being. To curb the virus‘s spread, the government implemented social restrictions (PSBB) in infected areas. These restrictions limited people‘s movement and activities, including closures of schools, offices, religious institutions, and public services. While intended to reduce infection rates, the PSBB policy also triggered various reactions. Hanoatubun (2020) highlighted the negative economic consequences of the PSBB, such as a slowdown in growth, increased competition for jobs, and financial strain on families.

The education sector also felt the impact, with restrictions affecting all levels from elementary to tertiary institutions (Angdhiri, 2020; Dewi, 2020; Pratiwi, 2020). While some saw potential in home-based learning fostering collaboration between students, teachers, and parents, a major challenge emerged in Indonesia was the lack of stable internet connections and suitable equipment for online learning. This mirrored a global trend where countries were inspired by the potential of distance learning but faced limitations in infrastructure and resources. Mas’udi & Winanti (2020) and Gao et al. (2020) emphasize the broader impact of COVID-19 beyond just health. The pandemic affected educational systems, transportation, the pharmaceutical industry, vulnerable communities, and even government communication strategies (Beniušis, 2023).

Moon, Oh, & Carley (2011) emphasized that unlike traditional media, where information flows top-down from journalists, social media allows the public to both produce and consume information, leading to a bottom-up spread of news and opinions. During the early stages of the explosive COVID-19 pandemic, social media witnessed an unparalleled explosion of digital discourse since social media messages, especially tweets, can be attributed to various user accounts, including individuals, media outlets, public figures, and even political figures (Bradley, 2009; Henderson & Bowley in Motion, Heath, & Leitch, 2016). Conversations erupted globally even before the first mask was worn or toilet paper stockpiled. Netizens worldwide weaved a complex tapestry of online discussions, expressing fear, frustration, and even humor. Hashtags like #StayHome, #FlattenTheCurve, and #stopthespread transcended borders, uniting individuals in a fight against this invisible enemy (Sutton, Renshaw, & Butts, 2020). Stark images of deserted streets and masked faces served as constant reminders of the pandemic‘s grip, yet laughter emerged as a surprising coping mechanism. Memes poking fun at sourdough starters and Zoom fatigue offered temporary relief from the harsh reality. Simultaneously, aside to those hashtags, Bahri & Widhyharto (2021) also found there are public figures and celebrity actors like Dr. Scott Johnshon and David Beckham within the discussion of COVID-19.

This research aimed to investigate the role of public figures amidst the early social restriction policy in Twitter (X). Therefore, the research observed the dynamics of online discussions among public figures and Indonesian netizens regarding the early social restrictions implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic. By analyzing tweets containing the keywords „psbb“ or „#psbb,“ the research aims to explore how these restrictions were perceived and debated on social media platform Twitter. Further, these key actors and their influences on this discussion may give interventions to policymakers to provide accurate information and encourage adherence to public health guidelines.

Literature Review

Global Opinion on The Early COVID-19 Outbreaks

The COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies the intricate relationship between communication technology and public opinion in shaping societal responses to global crises. Social media platforms have blurred traditional communication lines, fostering real-time dialogue and a sense of global interconnectedness, reflecting McLuhan‘s „global village“ concept (McQuail, 2010; West, Turner, & Zhao, 2010). Public opinion expressed on these platforms extends beyond mere popular sentiment, during the pandemic, it significantly influenced government policies and public behavior.

Global case studies highlight this complex interplay. In Brazil, social media, particularly WhatsApp, plays a major role in political participation and news consumption. Its encrypted nature allows rapid information sharing but also facilitates misinformation spread (Gagnon-Dufresne et al., 2023). This was evident during the 2018 elections and the COVID-19 pandemic, where President Bolsonaro used WhatsApp to downplay the virus‘s severity and promote unproven treatments, eroding public trust in health institutions and contributing to political instability.

Similarly, Bridgman et al. (2020) found that Twitter in Canada had higher misinformation levels compared to news sources on various COVID-19 themes. While news sources focused on public health recommendations, Twitter content had more misinformation, particularly regarding unproven cures and conspiracy theories. However, social media‘s impact is double-edged. In Pakistan, Yu et al. (2022) suggest that informed individuals use social media positively for connection and education, whereas Sharma (2023) found that social media use during lockdowns in India caused stress and frustration due to limited physical interaction.

These examples underscore the intricate interplay between public opinion, public figures, and communication technology, mentioned by van Dijk (2006) as the network society. While public opinion can be manipulated, as Hucker (2020) cautions, studies like Sirin et al.‘s (2021) on „group empathy“ suggest social media‘s potential to foster positive social movements. Anderson & Turgeon‘s (2023) work on party identification shows that social media can amplify and polarize public opinion. Specifically, Li (2021) found that social media platforms during COVID-19 in various countries such as the UK, the US, Mexico, Canada, Brazil, Spain, and Nigeria became crucial for public health officials and influential figures to spread health updates, calls for strong evidence-based leadership, and address anxieties about the pandemic‘s social and economic impacts.

Tweets in Shaping Public Figures’s Persona in Indonesia

In a 2010 study focused on gleaning political information during a six-month US election campaign, Gainous and Wagner (2014) discovered a fascinating trend. While half of the politicians had Twitter accounts, a significant portion (45%) rarely engaged with the platform. Even more intriguing, politicians who used Twitter primarily for attacking opponents saw diminished electoral success. This finding led Gainous and Wagner to propose alternative Twitter strategies for political campaigns, emphasizing tactics like sharing links to relevant information and using hashtags to promote issue-based discussions.

Examining the social media landscape, Chadwick, as cited in Calderaro (2014), identified three key areas of impact. First, it fosters a more competitive environment, allowing new and marginalized parties a chance to be heard. Second, social media empowers citizens, enabling grassroots movements to influence politicians and build a strong sense of community among supporters. These foster shared beliefs, solidarity, and even follower demonstrations on specific issues. Finally, the creative potential of social media in crafting campaigns necessitates adaptation for political institutions in this information age. However, Romejin (2020) argues that a party‘s success ultimately hinges on having a distinct position within the government.

The influence of Twitter on the political landscape is undeniable. It acts as a megaphone for citizen voices, transforming whispers into pronouncements that reach politicians and the wider world. Juditha (2014) observed this amplification during discussions surrounding the Police versus the KPK (Corruption Eradication Commission) on Twitter. Two dominant hashtags – #saveKPK and #saveIndonesia – emerged, signifying citizen support for the KPK. This empowers social movements, facilitates real-time news dissemination, and challenges established media narratives. However, Twitter‘s political utility remains undeniable. Ardha (2014) notes the growing awareness among political actors of social media‘s power to garner citizen support. The 2014 political campaign, for instance, witnessed a surge of targeted interactions vying for public attention.

This power, however, is a double-edged sword. Echo chambers can trap users in misinformation bubbles, while political actors can manipulate public opinion through bots and targeted campaigns. This potent mix fosters both increased engagement and transparency, but also carries the risk of polarization and democratic erosion. Ultimately, Twitter‘s impact on our political landscape hinges on our ability to navigate its complexities. We must wield its tools with critical thinking, seeking diverse perspectives to harness its potential for good and mitigate its potential for harm. Within this context, Ridwan Kamil, a candidate for governor-elect of West Java Province, provides a compelling example of effective Twitter engagement (Wulansari, 2014). He actively interacted with his followers on issues like government transparency, environment, healthcare, and culture.

The way our communication systems function today plays a role in this phenomenon. They, the public figures, prioritize what people already know and how they perceive facts. Consequently, political actors increasingly leverage social media to shape public opinion and perceptions, as noted in Ausserhofer and Maireder (2013) and Park (2013). This creates an opportunity for manipulation of political information. Different information dissemination strategies lead to distinct political behaviors. People tend to avoid information perceived as contradicting their existing beliefs (Gainous & Wagner, 2014). This results in a personalized information landscape for each social media user. As Twitter functions as both a source of information and a tool for virtual interaction, Januškevičiūtė (2022) mentioned that at the same time, public figures which have clear understanding of who they support and who the supporters are, can target specific demographics. This media proliferation of current events raises questions about the identity of those public figures, especially of the political actors.

Methods

This study delves into the Twitter hashtag #psbb, exploring it as a dedicated community where individuals engage in discussions centered around this specific topic. The research focuses on three key aspects of this conversation community: the contributors to the discussions, the nature of their contributions, and the behavioral roles of the users involved. Loosemore (1998) suggested that crises can bring to light the true interests of organizations and individuals. In the context of social media, these interests may not always be immediately apparent within the conversations. To uncover the behavioral roles of both organizations and individuals in the network and to understand the different types of relationships between them, the study applies the Social Network Analysis (SNA) approach. The research presents a case study on the COVID-19 outbreak in Indonesia, utilizing SNA to provide valuable visualizations and metrics that offer deep insights into the conversations taking place.

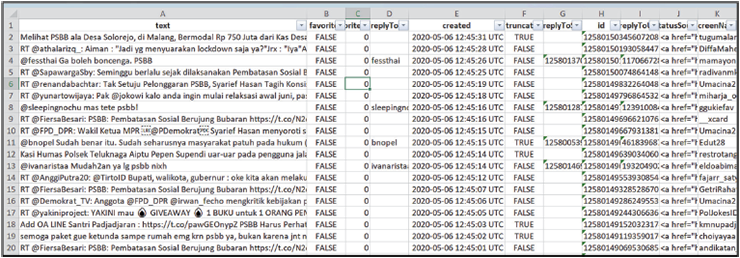

Data were taken from the Twitter API big data, dated May 6, 2020. This selection is based on several reasons. First, the COVID-19 outbreak became a global crisis communication issue in April 2020. Second, the Government of Indonesia reported the first COVID-19 case in May 2020. Third, during this period, the Government of Indonesia attempted to form a national task force to restrict people‘s movement. After mining the tweets, the interactive map and actors were identified using Gephi Mapping Software. Relationships can also be weighted or valued to assess the strength or frequency of actors in a network.

A qualitative method incorporating Social Network Analysis (SNA) will be used as the research framework. The primary interaction patterns will be captured to understand the impact of COVID-19-related hashtags on the Twitter platform. Data analysis will be conducted using big data analysis tools, including RStudio and Gephi mapping software. Data extraction is performed through data mining, which involves extracting data and patterns from large datasets. This process is based on the idea that massive datasets contain meaningful information that is nonrandom, valid, novel, useful, and ultimately understandable. SNA methodologies are used to map, measure, and analyze social relationships between individuals, teams, and organizations (Marsden, 2005; Zwijze-Koning & de Jong, 2015).

The tweet mining process in RStudio involves several steps:

#Accessing the Twitter API and Collecting Tweets#

> consumer_key = “s14c3kAYM1w84JEdKeSqKYXss”

> consumer_secret= “onrEpKaNmwxxCnQCPXULB8CjqZDREVwADhnVFa71DXn9Htzwfh”

> access_token = “2674012111-ESWnsnesak0O90sD6R8pekrmuucBkTtYbbKh1tt”

> access_secret = “diGElfjd1GI7b3lcui4cIdqABYjLO2WtzClInHwtGMjQi”

> install.packages(“rtweet”)

> install.packages(“twitteR”)

> install.packages(“ROAuth”)

> install.packages(“RCurl”)

> install.packages(“tm”, dependencies=TRUE)

> download.file(url=”http://curl.haxx.se/ca/cacert.pem”,

> destfile=”C:/D/cacert.pem”)

> psbb <- searchTwitter(“#psbb”, n=5000, cainfo=”cacert.pem”)

> psbb.df <- do.call(rbind, lapply(psbb, as.data.frame))

> write.csv(psbb.df, “C:/ /psbb.csv”)

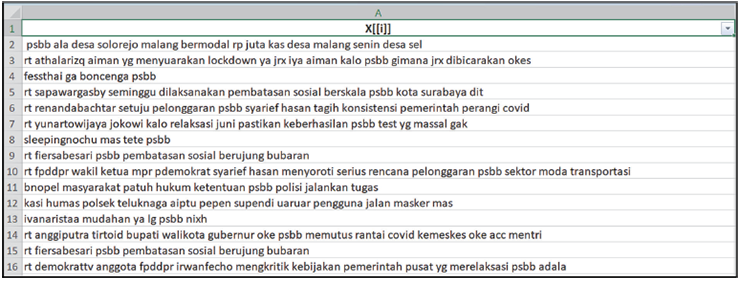

#Data Cleaning to remove duplicates, irrelevant information, and noise#

> psbb_list <- sapply(psbb, function(x) x$getText())

> psbb_corpus <- Corpus(VectorSource(psbb_list))

> psbb_corpus <- tm_map(psbb_corpus, tolower)

> psbb_corpus <- tm_map(psbb_corpus, removePunctuation)

> psbb_corpus <- tm_map(psbb_corpus, function(x)removeWords(x,stopwords()))

#Remove Stopwords in Indonesian Language#

> myStopwords = scan(“c://stopword.txt”,what=”character”)

twitcleanpsbb <- tm_map(twitcleanpsbb,removeWords,myStopwords)

#Saving The Data#

> dataframe <-data.frame(text=unlist(sapply(twitcleanpsbb, `[`)), stringsAsFactors=F)

write.csv(dataframe,file = ‘C://twitcleanpsbb.csv’)

This research utilizes Social Network Analysis (SNA) by using Gephi software to explore the dynamics of the conversation community formed around the #psbb hashtag on Twitter. SNA offers a method for mapping and analyzing relationships between actors (individuals or groups) within a network (Wasserman & Faust, 1994). Actors are visualized as nodes, and the connections between them represent the nature of their interactions. By employing SNA, the research can identify user roles (influencers, information sharers, etc.), map network relationships to understand information flow, and analyze the overall network structure to identify central nodes and user clusters. This approach, along with existing theories on collective behavior and social interaction (Borgatti et al., 1992), provides a framework to investigate how information spreads, opinions form, and individuals interact within this online conversation community. This data will then be compared to research discussing this phenomenon in May 2020. These include studies concerning the global governments and the Government of Indonesia‘s responses to COVID-19 outbreaks, studies about social media data analytics, and studies concerning the role of news and social media during COVID-19.

Figure 1. Result of tweets mining.

Figure 2. Result of data cleaning.

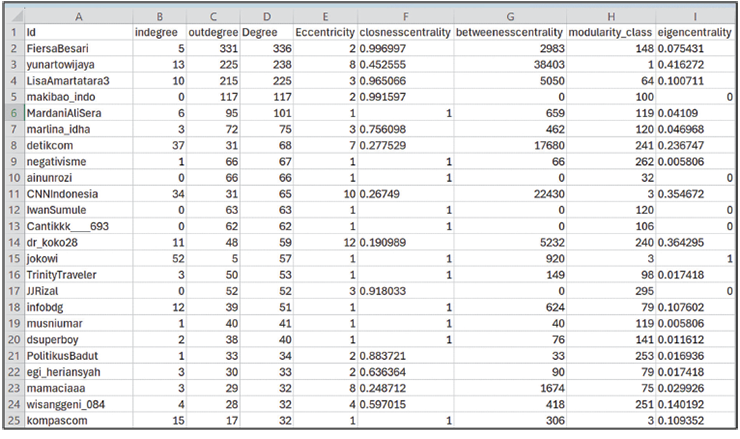

Figure 3. Degree of Centrality values of the network discussing #psbb.

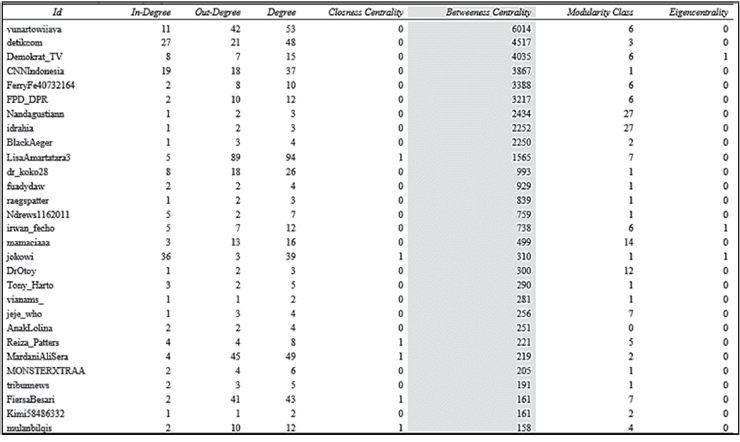

Figure 4. Centrality values based on Betweeness Centrality.

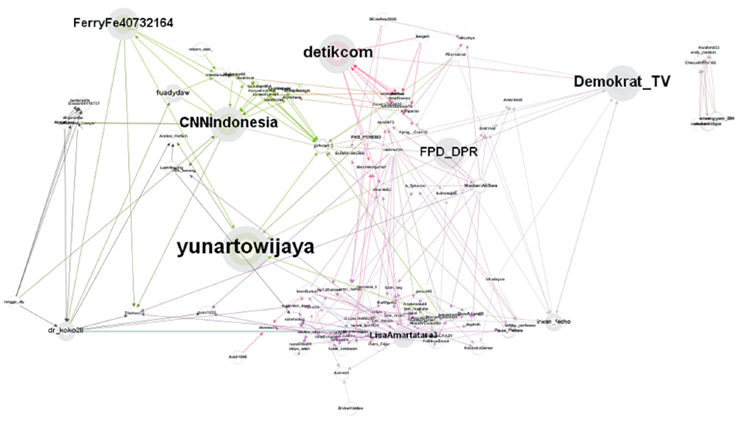

Figure 5. Main accounts amidst the early social restrictions policy.

Results and Discussion

Results

This research systematically identified approximately 877 Twitter accounts using the hashtag #PSBB, a prominent topic during the COVID-19 pandemic on May 6, 2020, particularly in the early stages of social restriction policies. The study aims to identify the key actors and issues in the discourse. While initially surprising, the presence of entertainers like Fiersa Besari in the conversation revealed intriguing nuances upon closer analysis. The study underscores Fiersa Besari‘s relevance as a private actor, suggesting that further examination of his content, engagement metrics, and interactions could offer valuable insights into his influence on the PSBB discussion. Fiersa Besari, an influential figure in Indonesia, serves as a role model for young people through his messages of hope and inspiration, noted for their authenticity, relatability, and personal connection with audiences.

The resulting analysis provides valuable insights into the complex yet interconnected nature of public discussion on this pressing social issue. This complexity can be examined through the analysis of network characteristics. The network comprises distinct communities, indicated by a modularity value of 0.864. A high modularity value typically signifies strong internal connections within each community but relatively weak connections between them, demonstrating significant internal cohesion within each community. The network is a complex system consisting of 393 subcommunities, which are integral to its structure and play a significant role in its overall cohesiveness. Each subcommunity is a cluster of nodes with a common attribute or connection set, contributing to the network‘s intricate segmentation and granularity. These subcommunities likely emerged from interactions between nodes over time, representing groups of nodes more tightly connected than the rest of the network.

The network diameter, which measures the farthest distance between any two nodes, has a value of 13 in this case. This represents the longest shortest path between any two nodes, consisting of 13 edges. This measurement is a crucial indicator of the network‘s interconnectedness and accessibility, providing valuable insights into how information or influence can propagate throughout the network. A lower network diameter denotes a more efficient network, where information or influence can travel through the network in fewer steps. Conversely, a higher network diameter suggests a less efficient network, where it may take more steps for information or influence to propagate. Additionally, the network‘s graphical density value is 0.000, indicating a high level of sparsity. This means that only a tiny fraction of possible connections among nodes are realized. Such a low density suggests that the network may be highly specialized or that connections are formed based on specific criteria, resulting in a less densely connected overall structure. This sparsity could imply that the network is composed of distinct, specialized groups with limited interactions between them.

The degree of centrality measures how connected a node is to other nodes in a network, calculated by counting the number of direct connections a node has. The data analysis indicates that there are five highly central accounts and five less central ones in the PSBB discussion on Twitter. The five most central accounts, based on the number of direct connections are Fiersa Besari (Individual Actor), Yunarto Wijaya (Individual Actor), LisaAmartatara3 (Individual Actor), Detikcom (Online Media), and CNN Indonesia (Online Media). At the same time there are other users that are mostly mentioned amidst the conversation such as Jokowi (Government Official), detikfinance (Online Media), Anis Baswedan (Government Official), Kompascom (Online Media), TirtoID (Online Media), infobdg (Online Media), and sbyfess (Online Media). Overall, the data highlights that the discussion on Twitter related to the social restriction policy was mainly driven by a small number of highly central accounts.

Discussion

The appearances of several actors in this network played a critical role in shaping the public discourse of the crucial policy since their tweets were frequently retweeted and commented on. It supports the finding of Yoo’s research (2016) highlighting that information spreads more rapidly when originating from users with a high level of influence, measured by their social connections or number of followers. During the pandemic, Chairil (2020) emphasizes the late response and public health securitization during Indonesia‘s early COVID-19 phase. Individuals like Fiersa Besari, through their artistic expressions and social commentary, likely resonated with public anxieties and concerns not fully addressed by the authorities. The conversation of the Member of Parliament Mardani Ali Sera who criticized the delayed policy during the COVID-19 and the discourse of Chinese workers coming into Indonesia are reported also by De Salazar et al. (2020) and Djalante et al. (2020) as well. Their findings realize that during May 2020, the online discussion appears to call for transparency and responsiveness from the authorities. That is the reason why public health officials and policymakers should leverage insights from network analysis to identify influential voices, address pressing public concerns, and tailor messaging to resonate with diverse communities.

The emergence of media outlets in the networks suggests that they act as key nodes in the network, amplifying information and shaping public discourse on the PSBB policy. Ohme (2020) & Bajçinca (2024) argued that social media, especially news on social media, has become a central platform for news consumption and dissemination, with established media houses playing a crucial role in setting the agenda for online conversations. The dominance of media outlets in the top ten positions further underscores their crucial role in shaping the PSBB conversation on Twitter. By acting as gatekeepers and curators of information, they provide a platform for diverse perspectives and viewpoints to be shared and debated (Duncombe, 2019). This fosters a more informed and engaged public discourse, allowing users to access a variety of arguments and engage in critical discussions beyond their own personal networks. Furthermore, research by Bruns (2012), Romero (2014), and Rosa (2014) support this notion, arguing that social media has transformed the traditional public sphere by empowering media organizations to act as commentators rather than simply passive transmitters of information. Through features like retweets, hashtags, mentions, and replies, media accounts on Twitter actively cultivate interactive spaces where users can engage with news content, share their opinions, and challenge viewpoints. However, it‘s crucial to consider potential limitations to this model. The prominence of certain media outlets may raise concerns about bias and agenda-setting. Additionally, algorithms and content moderation practices can inadvertently shape the visibility of certain perspectives and potentially silence marginalized voices.

Furthermore, the analysis highlights the democratizing potential of social media in facilitating direct engagement with otherwise inaccessible individuals. The presence of high-profile figures like Jokowi and Anies Baswedan among the top ten users underscores this phenomenon. This bypasses traditional gatekeepers and enables citizens to directly voice their opinions and concerns to decision-makers. This democratization of voice can potentially influence policy decisions, as evidenced by research from Seib (2012) who found that increased online engagement with elected officials can lead to greater responsiveness to public needs. Additionally, the direct communication channel fostered by social media can enhance public participation in policy debates. By circumventing traditional media filters and allowing unfiltered public voices to be heard, social media platforms like Twitter can contribute to a more inclusive and participatory policymaking process named connective democracy (Jungher, 2015; Jungher, Schoen, & Jürgens, 2016). However, it is important to acknowledge potential limitations of this direct engagement.

Concerns about echo chambers, misinformation, and manipulation tactics employed by some actors can potentially skew public discourse and undermine the democratic potential of social media. In this network, simply being active doesn‘t automatically influence even though we are knowing each affiliation. One may state that Yunarto Wijaya has connection to Joko Widodo during 2019 presidential election campaign. And another may state that Mardani Ali Sera is part of the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) faction. Furthermore, exploring network dynamics beyond simple identification of political factions is crucial. Identifying such bridges and points of connection provides deeper insights into how diverse viewpoints come together and potentially shape the overall discourse since that there will be a tendency for opposing parties to support opinions that reject specific policies on certain issues (Romejin, 2020).

Baharuddin et al. (2021) investigates that the COVID-19 case in Indonesia was increasing since March 2020 to May 2020. During the period from March 2020 to May 2020, the number of COVID-19 outbreaks showed a significant and alarming increase. Coping with this phenomenon, the central government of Indonesia has collaborated with local governments to reallocate budgets to address the health and economic impacts of COVID-19. President Jokowi urged both central and regional governments to ensure the availability of basic commodities, maintain people‘s purchasing power, and mitigate the risk of employee terminations during the pandemic. This action is seen during the research. President Jokowi Twitter’s account appears amidst the discussion on #psbb. It is emphasized later by Haman (2020) where they found that the President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) is among the twenty three governments’ officials like Australia, Taiwan, Czechia (Czech Republic), Singapore, Morocco, the United States, Canada, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Japan, Indonesia, Ecuador, Argentina, Jamaica, the Bahamas, Bhutan, Italy, Panama, the Netherlands, Brazil, Spain, and Guatemala.

Since the policy is considered not optimally run, the quick response of the governments in this case is crucial. According to Li et al. (2021), it is important for the government to demonstrate their commitment to public health and to provide valid and reliable information to the public.. So that, even though the appearance of President Joko Widodo is relatively small, the people hope there will be a policy regarding the increasing cases of COVID-19 in Indonesia. Rahmanti et al. (2021) noticed this phenomenon and then give the evidence of that policy. In their study, the finding mentioned that after the rapid outbreaks of COVID-19 cases, on June 5th, 2020, the Government of Indonesia implemented the New Normal Policy. The new policy, somehow, became trusted by the netizens. Their analysis found that tweets of “New Normal” showed more than 50% of trusting the new policy.

While our analysis of Twitter users‘ posts found that government communication plays a limited role in public health crises, it also reveals strong emotions like anticipation and anger on social media. Sharma (2023) further highlights this by pointing out that Twitter users‘ anger might be directed not just at current officials, but also at those from past governments. One of the possible reasons is that the use of social media as an information source may result in several misperceptions such as conspiracy theory, the consumption of bats, about consuming Vitamin-C, and about the less effect than the flu (Bridgman et al., 2020). Therefore, this study suggests that a well-maintained social media presence, particularly on Twitter, by government officials can build public trust since this platform may multiplying tweets in an instant.

Conclusion

The analysis of Twitter networks during Indonesia‘s early COVID-19 phase reveals significant insights into the dynamics of public discourse and policy communication. Key actors, including high-profile figures and media outlets, played critical roles in shaping the conversation around public health policies, such as the PSBB (large-scale social restrictions). Influential individuals like Fiersa Besari and Mardani Ali Sera, along with media outlets, amplified public concerns and criticisms, calling for greater transparency and responsiveness from authorities. The emergence of media outlets as key nodes in the network underscores their crucial role in amplifying information and setting the agenda for online conversations. By acting as gatekeepers and curators of information, media outlets foster a more informed and engaged public discourse, allowing users to access a variety of arguments and engage in critical discussions beyond their own personal networks.

The rise of social media has provided an opportunity for direct interaction between citizens and policymakers, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. Notably, influential figures such as President Jokowi and Anies Baswedan are active on Twitter, allowing citizens to express their thoughts and concerns directly to decision-makers. This direct line of communication has increased public involvement in policy discussions, potentially influencing policy choices. However, it‘s important to address issues such as echo chambers, misinformation, and manipulation tactics, which can distort public discourse and diminish the democratic potential of social media. Additionally, concerns about bias, the influence of dominant media outlets, and the impact of social media algorithms on content visibility add complexity to public conversations on social media. Therefore, it‘s crucial for the government to understand the real-time public sentiment and respond promptly to relevant discussions. Further studies should be conducted to investigate the role of social media algorithms in shaping public discourse and explore the emotional tone of tweets which can provide valuable insights into the emotional dynamics of social media communication. Thus, through that strategy, the future research can identify several characteristics of influencing actors on social media who can lead the opinion of netizens about certain policies.

References

Anderson, D. C., & Turgeon, M. (2023). Comparative Public Opinion. Routledge.

Angdhiri, R. P. (2020, April 11). Challenges of home learning during a pandemic through the eyes of a student. The Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2020/04/11/challenges-of-home-learning-during-a-pandemic-through-the-eyes-of-a-student.html

Ardha, B. (2014). Social media sebagai media kampanye partai politik 2014 di Indonesia. Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi, 13(1), 105–120. http://dx.doi.org/10.22441/jvk.v13i1.383

Ausserhofer, J., & Maireder, A. (2013). National politics on Twitter: Structures and topics of a networked public sphere. Information, Communication & Society, 16(3), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.756050

Baharuddin, T., Sairin, S., Jubba, H., Qodir, Z., Nurmandi, A., & Hidayati, M. (2021). Social capital and social trust: the state‘s response in facing the spread of COVID-19 in Indonesia. Sociología y tecnociencia, 11(2), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.24197/st.2.2021.23-47

Bahri, M. T., & Widhyharto, D. S. (2021). Twitter-based digital social movement pattern to fight COVID-19. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial Dan Ilmu Politik, 25(2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.22146/jsp.56872

Bajçinca, E. (2024). The Consequences of Digitization and Challenges to Kosovar Magazines in the Era of Social Media. Information & Media, 99, 8–22. https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2024.99.1

Bekafigo, M. A., & McBride, A. (2013). Who tweets about politics? Political participation of Twitter users during the 2011 gubernatorial elections. Social Science Computer Review, 31(5), 625–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439313490405

Beniušis, V. (2023). Internal Communication Challenges and Their Solution When Hybrid Work is Implemented in a Public Sector Organization: The Case Study of the Ministry of Transport and Communications of the Republic of Lithuania. Information & Media, 95, 94–115. https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2023.95.59

Bradley, P. (2009). Mass media and the shaping of American feminism, 1963–1975. University Press of Mississippi.

Bridgman, A., Merkley, E., Loewen, P. J., Owen, T., Ruths, D., Teichmann, L., & Zhilin, O. (2020). The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: Understanding the role of news and social media. Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-028

Bruns, A. (2011). How long is a Tweet? Mapping dynamic conversation networks on Twitter using Gawk and Gephi. Information, Communication & Society, 15(9), 1323–1351. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.635214

Burnell, K., George, M. J., Kurup, A. R., Underwood, M. K., & Ackerman, R. A. (2021). Associations between Self-Reports and Device-Reports of Social Networking Site Use: An Application of the Truth and Bias Model. Communication Methods and Measures, 15(2), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2021.1918654

Calderaro, A. (2014). Internet politics beyond the digital divide: A comparative perspective on political parties online across political systems. In B. Pătruţ & M. Pătruţ (Eds.), Social media in politics: Case studies on the political power of social media (pp. 3–18). Springer International Publishing.

Chairil, T. (2020). Respons Pemerintah Indonesia Terhadap Pandemi COVID-19: Desekuritisasi Di Awal, Sekuritisasi Yang Terhambat. IR Binus, 23.

De Salazar, P. M., Niehus, R., Taylor, A., Buckee, C. O., & Lipsitch, M. (2020). Identifying Locations with Possible Undetected Imported Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Cases by Using Importation Predictions. Emerging infectious diseases, 26(7), 1465–1469. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2607.200250

Dewi, W. A. (2020). Dampak Covid-19 terhadap implementasi pembelajaran daring di Sekolah Dasar. Edukatif: Jurnal Ilmu Pendidikan, 2(1), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.31004/edukatif.v2i1.89

Djalante, R., Lassa, J., Setiamarga, D., Sudjatma, A., Indrawan, M., Haryanto, B., Mahfud, C., Sinapoy, M. S., Djalante, S., Rafliana, I., Gunawan, L. A., Surtiari, G. A. K., & Warsilah, H. (2020). Review and analysis of current responses to COVID-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020. Progress in Disaster Science, 6, Article 100091. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091

Gainous, J., & Wagner, K. M. (2014). Tweeting to power: The social media revolution in American politics. Oxford University Press.

Gagnon-Dufresne, M. C., Azevedo Dantas, M., Abreu Silva, K., Souza Dos Anjos, J., Pessoa Carneiro Barbosa, D., Porto Rosa, R., de Luca, W., Zahreddine, M., Caprara, A., Ridde, V., & Zinszer, K. (2023). Social media and the influence of fake news on global health interventions: Implications for a study on dengue in Brazil. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), Article 5299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075299

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Fu, H., & Dai, J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 15(4), Article e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

Government Regulation of The Republic of Indonesia Number 21 the Year 2020 Concerning Nation-Wide Social Restictions (PSBB) to Reduce Corona Virus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) (2020). https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC195053/

Haman, M. (2020). The use of Twitter by state leaders and its impact on the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon, 6(11), Article e05540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05540

Hanoatubun, S. (2020). Dampak Covid-19 terhadap perekonomian Indonesia. EduPsyCouns Journal, 2(1), 146–153. https://ummaspul.e-journal.id/Edupsycouns/article/view/423

Hucker, D. (2020). Public opinion and twentieth-century diplomacy: A global perspective. Bloomsbury Academic.

Januškevičiūtė, J. (2022). Threats to the Process of Receiving Political News from Echo Chambers and Filter Bubbles on Social Media. Information & Media, 94, 39–52. https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2022.94.64

Juditha, C. (2014). Opini publik terhadap kasus „KPK Lawan Polisi“ dalam media sosial Twitter. Jurnal Pekommas, 17(2), 61–70. https://doi.org/10.30818/jpkm.2014.1170201

Jungher, A. (2015). Analyzing political communication with digital trace data: The role of Twitter messages in social science research. Springer International Publishing.

Jungher, A., Schoen, H., & Jürgens, P. (2016). The mediation of politics through Twitter: An analysis of messages posted during the campaign for the German Federal Election 2013. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(1), 50–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12143

Kim, J., & Hastak, M. (2018). Social network analysis: Characteristics of online social networks after a disaster. International Journal of Information Management, 38(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.08.003

Li, L., Aldosery, A., Vitiugin, F., Nathan, N., Novillo-Ortiz, D., Castillo, C., & Kostkova, P. (2021). The response of governments and public health agencies to COVID-19 pandemics on social media: A multi-country analysis of Twitter discourse. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, Article 716333. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.716333

Loosemore, M. (1998). Social network analysis: using a quantitative tool within an interpretative context to explore the management of construction crises. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 5(4), 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb021085

Marsden, P. V. (2005). Recent developments in network measurement. In P. J. Carrington, J. Scott, & S. Wasserman (Eds.), Models and methods in social network analysis (pp. 8–30). Cambridge University Press.

Mas‘udi, W., & Winanti, P. S. (2020). Tata Kelola Penanganan Covid-19 di Indonesia: Kajian Awal. Gadjah Mada University Press.

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail’s mass communication theory (6th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Moon, I.-C., Oh, A. H., & Carley, K. M. (2011). Analyzing social media in escalating crisis situations. Proceedings of 2011 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics, 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISI.2011.5984053

Motion, J., Heath, R. L., & Leitch, S. (2015). Social Media and Public Relations: Fake Friends and Powerful Publics (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203727799

National Special Force for Covid-19. (2020, May 8). Pasien Sembuh COVID-19 Naik Jadi 2.494, Kasus Meninggal 943 Orang. https://covid19.go.id/p/berita/pasien-sembuh-covid-19-naik-jadi-2494-kasus-meninggal-943-orang

Nuraini, R. (2020, March 2). Kasus Covid-19 pertama, masyarakat jangan panik. https://indonesia.go.id/narasi/indonesia-dalam-angka/ekonomi/kasus-covid-19-pertama-masyarakat-jangan-panik

Park, C. S. (2013). Does Twitter motivate involvement in politics? Tweeting, opinion leadership, and political engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1641–1648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.01.044

Pratiwi, E. W. (2020). Dampak Covid-19 terhadap kegiatan pembelajaran online di sebuah perguruan tinggi kristen di Indonesia. Perspektif Ilmu Pendidikan, 34(1), 1–8. doi:10.21009/PIP.341.1

Presidential Regulation of The Republic of Indonesia Number 7 the Year 2020 Concerning Task Force to Reduce Corona Virus Disease 2019 (Covid-19).

Rahmanti, A. R., Ningrum, D. N. A., Lazuardi, L., Yang, H.-C., & Li, Y.-C. (2021). Social media data analytics for outbreak risk communication: Public attention on the “New Normal” during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 205, Article 106083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106083

Romejin, J. (2020). Do political parties listen to the(ir) public? Public opinion-party linkage on specific policy issues. Party Politics, 26(4), 426–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818787346

Romero, L. D. (2014). On the web and contemporary social movements: An introduction. In B. Pătruţ & M. Pătruţ (Eds.), Social media in politics: Case studies on the political power of social media (pp. 19–34). Springer International Publishing.

Rosa, A. L. (2014). Social media and social movements around the world: Lessons and theoretical approaches. In B. Pătruţ & M. Pătruţ (Eds.), Social media in politics: Case studies on the political power of social media (pp. 35–48). Springer International Publishing.

Seib, P. (2012). Real-time diplomacy: Politics and power in the social media era. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sharma, N. (2023). Digital moral outrage, collective guilt, and collective action: An examination of how Twitter users expressed their anguish during India’s COVID-19 related migrant crisis. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 47(1), 26–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/01968599221081127

Sirin, C. V., Valentino, N. A., & Villalobos, J. D. (2021). Seeing us in them: Social divisions and the politics of group empathy. Cambridge University Press.

Sutton, J., Renshaw, S. L., & Butts, C. T. (2020). The first 60 days: American public health agencies‘ social media strategies in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. Health Security, 18(6), 454–460. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2020.0105

van Dijk, J. A. (2006). The network society: Social aspects of new media (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Wang, X. (2014). How Do People Participate in Social Network Sites After Crises? A Self-Determination Perspective. Social Science Computer Review, 32(5), 662–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314525116

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press.

We are social. (2019, March 7). Lipsus Internet 2019. https://websindo.com/indonesia-digital-2019-media-sosial/

West, R. L., Turner, L. H., & Zhao, G. (2010). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application (Vol. 2). McGraw-Hill.

WHO Statement. (2020, April 27). WHO timeline - COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19

Wulansari, I. (2014). Artikulasi komunikasi politik Ridwan Kamil dalam media sosial Twitter. Jurnal Ilmu Komunikasi, 6(2), 20–40. https://doi.org/10.31937/ultimacomm.v6i2.413

Xiao, F., Noro, T., & Tokuda, T. (2012). News-topic oriented hashtag recommendation in Twitter based on characteristic co-occurrence word detection. In M. Brambilla, T. Tokuda, & R. Tolksdorf (Eds.), Web engineering: 12th international conference, ICWE 2012 proceedings (pp. 16–30). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Yoo, E., Rand W., Eftekhar, M., & Rabinovich, E. (2016). Evaluating information diffusion speed and its determinants in social media networks during humanitarian crises. Journal of Operations Management, 45(1), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2016.05.007

Yu, S., Abbas, J., Draghici, A., Negulescu, O. H., & Ain, N. U. (2022). Social media application as a new paradigm for business communication: The role of COVID-19 knowledge, social distancing, and preventive attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 903082. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903082

Zwijze-Koning, K. H., & de Jong, M. D. (2015). Network analysis as a communication audit instrument: Uncovering communicative strengths and weaknesses within organizations. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 29(1), 36–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1050651914535931