Information & Media eISSN 2783-6207

2025, vol. 102, pp. 84–111 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Im.2025.102.5

A Qualitative Approach to Understand Key Components of Independent Film Production Companies’ Business Model in the European Film Market

Ieva Vitkauskaitė

Vilnius University

vvvieva@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1900-1033

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Abstract. The purpose of this study is to better understand what components of business models independent film production companies in Europe use to compete in the European film market using empirical data from multiple countries. It provides an analysis of independent film production companies’ business model components which are comprised of the elements ‘Value creation’, ‘Value proposition’, and ‘Value capture’. The empirical study was implemented by using purposive sampling. The participants included 17 experts from 8 European countries with direct links to practical management of a film production company who are denoted by comprehensive experience within the European film industry as well as the business models used by independent film production companies. Thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews identified 11 categories encompassing 60 sub-categories.

By using the results of the empirical research study, a model has been created to show the relationship of components and sub-constructs that make independent film production companies competitive in the market. Two critical components were identified in the research that independent film production companies need to focus on. They include outstanding talent as one of the key components of the business model and stakeholders/investment partners. The study has also revealed challenges that include slow funding systems based on subsidies. The results of the study thus shed light on the general situation for independent film production companies, and form a foundation for future studies in this area. The article was written based on a dissertation in progress.

Keywords: business model, film production, independent film production company, film production company, European film market, film industry.

Kokybinis požiūris siekiant suprasti pagrindinius nepriklausomos kino gamybos kompanijos verslo modelio komponentus Europos kino rinkoje

Santrauka. Tyrimo tikslas – pasitelkiant empirinius duomenis iš įvairių šalių, geriau suprasti, kokie Europos nepriklausomų kino gamybos kompanijų verslo modelio komponentai yra naudojami konkuruojant Europos kino rinkoje. Straipsnyje pateikiami ir analizuojami nepriklausomos kino gamybos kompanijos verslo modelio „Vertės kūrimo“, „Vertės pasiūlymo“ ir „Vertės pagavimo“ elementų komponentai. Empirinis tyrimas atliktas naudojant tikslinę atranką. Tyrime dalyvavo 17 ekspertų iš 8 Europos šalių, visi jie turi glaudžias sąsajas su kino gamybos kompanijų praktiniu valdymu, kompleksiniu išmanymu apie nepriklausomų kino gamybos kompanijų verslo modelius, Europos kino industriją. Iš dalies struktūruoti interviu buvo analizuojami pasitelkiant tematinę analizę, kurios metu identifikuota 11 kategorijų ir 60 subkategorijų.

Naudojant empirinio tyrimo gautus rezultatus, sukurtas modelis, kuriame atsiskleidžia nepriklausomų kino gamybos kompanijų komponentų ir subelementų, naudojamų konkuruojant rinkoje, ryšiai. Tyrimo metu identifikuoti du ypač svarbūs komponentai. Vieni iš pagrindinių verslo modelio komponentų yra išskirtinis talentas ir suinteresuotos šalys ir (arba) investiciniai partneriai. Taip pat tyrimas atskleidė iššūkius, su kuriais susiduria kompanijos, pavyzdžiui, lėta finansavimo sistema, paremta subsidijomis. Tyrimo rezultatai atskleidžia nepriklausomų kino gamybos kompanijų bendrą situaciją ir suteikia pagrindą būsimiems šios srities tyrimams. Straipsnis parašytas remiantis rašoma disertacija.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: verslo modelis; kino gamyba; nepriklausoma kino gamybos kompanija; kino gamybos kompanija; Europos kino rinka; kino industrija.

Received: 2024-07-13. Accepted: 2025-07-03.

Copyright © 2025 Ieva Vitkauskaitė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

A business model is a simplified and generalized representation of a company’s activities (Wirtz et al., 2015). A business model refers to the logic of a company, the way it operates and how it creates value for its stakeholders (Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, 2010) and can be a form of creating entrepreneurial opportunities (George & Bock, 2011). It should be noted that the development of a business model helps to remain competitive in the market (Teece, 2010; Wirtz et al., 2015).

Film is a complex product, and each film has its own business model. However, the overall business model of an independent film production company must also be considered when developing the product business model, and vice versa. It is of importance to understand that film production companies create films – that is, art products. This means that it is essential to generate not only direct economic value, but also, for instance, artistic and educational value, or, depending on the company’s objectives and the audiovisual media policy of the country, certain films may convey ideological and political issues because semiotic codes are used in product development.

The film industry is a risky business environment because it lacks financial security and is difficult to control and accurately predict (Finney & Triana, 2015). Additionally, Finney (2008) suggested that “independent film production, which is essentially most film production outside the Hollywood system, is a fragmented, ill-structured and, for that reason, a highly demanding business” (p. 107). However, independent production is a key driver in fostering cultural diversity (Cabrera Blázquez et. al., 2019), and, according to the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005), “each Party may adopt measures aimed at protecting and promoting the diversity of cultural expressions within its territory” (Article 6, paragraph 1).

This study focused specifically on how independent film production companies compete in the European film market, by using empirical data from multiple countries. It adds to the body of knowledge by contributing to not only the independent film production business as a business, but by also contributing the company perspective and regional focus that are both well-founded and growing. The empirical research presented here also incorporates the specific nature of the film industry and the company business model. The purpose of this study is to better understand what components of business models independent film production companies in Europe are using to compete in the European film market.

It should be noted that this study based on a theoretical article by the same researcher, published in 20201, which outlines general types of film business models for production companies in the film industry. For the purposes of this article, four models were used for this study: 1. Horizontal integration, 2. Vertical integration, 3. Product-oriented, and 4. Market oriented. The first of these, horizontal integration, allows the coverage of a broader spectrum of audiences and production and distribution of film, television, and games, while, at the same time, expanding the consumer base (Finney & Triana, 2015). The second model, vertical integration, occurs when a company covers as many elements of the value chain as possible to maximize profits (Finney & Triana, 2015). Next, the market-oriented model posits that films are adapted to the market demands, and decisions are made with market considerations in mind (Jaworski, Kohli, & Sahay, 2000 as cited in Guild & Joyce, 2006). It is of importance to note that the high concept model, a framework employed to delineate a particular archetype in the Hollywood producer-centered filmmaking process (Wyatt, 1994 as cited in Strandgaard, 2011), characterized by a market-driven approach and the extensive employment of ‘integrated professionals’ (Becker, 1982 as cited in Strandgaard, 2011) falls under this category. Finally, in contrast to the market-oriented model, the product-oriented model suggests that business decisions are made on the product itself, aiming to achieve the highest possible quality with the expectation that the market will recognize and appreciate it (Guild & Joyce, 2006). It can be assumed that the auteur model as a form of ‘European’ director-centered filmmaking – where the director is the central and most influential figure, and where ‘Mavericks’ who challenge and break away from the conventional film industry norms predominate (Strandgaard, 2011) – falls under this category. It should also be noted that this study focused on a new film value chain consisting of: the producer, the aggregator, and the consumer (Finney, 2014). In the empirical study, the main characteristics of the business models were analyzed.

In order to obtain more detailed information and to bring some structure and clarity to this empirical study, three dimensions were used to explain a company’s business model. For the basic framework, Clauss’s (2016) synthesized business model literature review (for instance, Morris et al., 2005; Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010) was used as a basic framework for the foundational conceptualized business model components and/or dimensions, where it was suggested that a company’s business model framework consists of three main dimensions: value creation, value proposition, and value capture. Clauss (2016) further divided each dimension into aggregated groups of business model sub-constructs relevant to business model innovation. For instance, sub-constructs of value proposition innovation include new offerings, new customer segments/markets, and others. In this study, the business model is also broken down into dimensions and their corresponding sub-constructs.

Wirtz et. al. (2015) reviewed the relevant literature (for instance Hamel (2000) and Johnson (2010)) on business models and identified the key components. The authors outlined components related to the following aspects: strategy, resources, network, customers, market offering (value proposition), revenues, service provision, procurement, and finances. It should be noted that these business model components can be aligned with the groups of business model sub-constructs proposed by Clauss (2016). In this study, the value creation sub-constructs adapted from Clauss (2016) include capabilities, technologies/equipment, organization/processes/structures, and partnerships. The value proposition subconstructs comprise offerings, customer segments/markets, channels, and customer relationships. The value capture sub-constructs encompass revenue models and cost structures. While this study does not propose any new theoretical major sub-constructs of the business model, it contributes by identifying industry-specific components that independent film companies can leverage for competitive advantage. In addition, the empirical research reveals the general situation of independent film production companies, such as the predominant size of companies, market challenges, and innovations. This study enables the formulation of new hypotheses regarding the business models and management of independent film production companies, as well as the European film market.

It should be emphasized that the definition of an independent film production company varies from region to region, and from country to country. According to Cabrera Blázquez et al. (2019), independent production remains associated with the concept of production outside the system of major studios. For the purpose of this study, an independent film production company is not associated with, nor is it part of any major U.S. studios; it is also not enrolled into the Motion Picture Association2. According to the European Coordination of Independent Producers (CEPI), the European Production Association (2021), and statutes, “independent production is considered as not controlled, de facto or de jure, by a broadcaster and which can therefore maintain managerial independence and freedom to dispose of its production or which is recognized as an independent by the national Associations represented” (p. 2). In this study, an independent film production company (which, for the purpose of this study, will also be referred to as ‘the company’ or ‘film production company’) focuses on the production of cinematographic works, while maintaining managerial independence from streaming company services (hereafter referred to as ‘streamers’), broadcast companies, distributors, and retaining freedom to dispose of its production; also, the company is established in the European film market.

Organization and Methodology of the Empirical Research

The empirical study was implemented by using purposive sampling. Purposive sampling is acceptable for studies in which the researcher has an interest in studying informants possessing a high level of knowledge regarding the research topic (Creswell, 2013 as cited in Elo et al., 2014). Analyzing information-rich cases tends to produce insights and a deeper understanding, rather than facilitating empirical generalizations (Patton, 2002). The chosen expert sampling allows for the collection of specific information and facilitates an understanding not only of the prevailing features of the business model, but also of the underlying reasons behind them. This approach provides insights into the specificities of the European film market in practice, enabling a holistic view of the business development of independent film production companies and allowing for the identification of market failures.

Firstly, representatives from associations of producers were selected because they represent the interests of producers and possess relevant experience for the study. Additionally, experts from national film institutes were included, as these institutions support and promote national film and cinema culture, as well as film production.

Invitation emails explaining the purpose of the study and the planned publication of its results were sent out to 28 European associations of producers and national film institutes, thus inviting them to participate in the study. Recommendations were also made for the inclusion of additional participants with relevant expertise in the subject matter of the study. Notably, the process began with the establishment of the initial contact. Two participants declined to participate in the study – one without stating a reason, and the other citing a demanding schedule. The sample population was comprised of 17 expert participants from 8 European countries: Lithuania, Germany, Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, Sweden, Latvia, Switzerland. It should be noted that, although six of the experts were from Lithuania, this did not significantly bias the findings, as the remaining 11 experts represented a diverse range of European countries, as previously indicated. Moreover, the Lithuanian experts are actively involved in substantial co-production projects with European partners and are members of various multi-national and regional professional organizations. However, the focus is naturally placed on the specific characteristics of small markets, such as Lithuania.

The experts’ key positions included: a member of the European producers’ professional organization – a board member of the national independent producers association – a founder and the head of an independent film production company – a producer – an investor – a strategy developer – a lecturer – a founder and board member of a film cluster; a previously active producer (for more than 26 years) before becoming a managing director at the national film institute; a national film institute representative – a lecturer-producer; a national film institute representative; a board member of the national animation association – a founder and the head of an independent film production company – a producer; a member of an independent producers association – a founder and the head of an independent film production company – a producer; a managing partner of a film and visual arts cluster; an executive director of an audiovisual producers association; previously, a CEO of the international film sales agency before becoming a managing director at a film and TV production company; a representative of an independent film production company which is one of the three largest in one Nordic country; a co-founder and the head of an independent film production company – a director – a producer – a member of a producers association; a member of a film producers association – the owner of an independent film production company and a film studio – a producer – a director – a former owner and CEO of a major television company; a member of the European producers professional network – a founder and the head of an independent film production company who developed budget management software; a chairman – a CEO of an independent film production company which has become one of the leading independent production companies in the Nordic region over the past decade; an executive producer – a producer – a founder (with more than 40 years background in the film business) of a film production company whose films have received international recognition, as well as major awards (e.g., Oscars) and which has created a film movement, and it is one of the most the most prolific, famous and critically acclaimed production companies in the Nordic countries and entire Europe.

To gather the required data, semi-structured interviews were employed with the aim of achieving a comprehensive understanding of the broader context, as well as gaining insight into the current situation of film production companies and the prevailing business models. Semi-structured interviews take into account differences in the interviewees’ worldviews and perspectives. This method uses an interview guide that encompasses broad themes to be explored during the conversation (Qu & Dumay, 2011). The guide initially consisted of preliminary open-ended questions and was subsequently expanded into 14 questions, grouped into eight thematic blocks. The preliminary questions aimed to identify the components of business models that film production companies in Europe use to compete in the European film market. The questions sought to determine whether film production company executives primarily focus on a product-oriented model or a market-oriented model, and to explore the influence of film producers on the entire filmmaking process (with some attention given to the artistic value, depending on the target market). The study also aimed to understand the marketing practices for films – for example, whether marketing is handled by the production company itself or outsourced to specialized marketing firms – and to examine the prevalence of film merchandise. In addition, the questions addressed the extent to which horizontal integration is practiced by film production companies, including how many companies cover all stages of the film value chain, and how common it is to operate a value chain without theatrical exhibition. Further questions explored the development of additional products and services. Given the financial insecurity, which is often present in the film industry, particular attention was paid to the questions focusing on the types of investors, and whether production companies are able to develop and produce films without public funding, thereby expanding their operations within the European market. Finally, the questions also addressed the point how widespread it is for companies to establish divisions in international markets or to expand through mergers and acquisitions. The questions were framed in a way so that to prompt the participants to reflect on both their national context and the European film market as a whole.

Data collection involved several steps. After the initial contact was established and consent to participate in the study was obtained, the researcher scheduled a meeting with each participant in person. It should be noted that the participation was fully voluntary. If necessary, the participants had the opportunity to request additional information about the study, the researcher, and previous research activities. Prior to the full data collection through the semi-structured interview, each participant was sent preliminary questions, an outline of the company’s business model covering value creation, value proposition, and value capture, as well as a definition related to an independent film production company.

Due to contact restrictions in place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the interviews were conducted virtually by using the Microsoft Teams or Google Meet software. The interview used both audio and video, and thus the researcher could see the participants’ emotions and body language to better facilitate an open conversation and afford a closer contact. However, if participants experienced technical difficulties or other issues, the interview was conducted without a video transmission. It should be noted that verbal consent to record the interviews was obtained at the meeting, prior to recording. The recordings were used solely for the purpose of transcribing the interviews, and the material was used exclusively for this study. No confidential information was requested during the interviews. In one instance, the interview was completed through email communication.

One of the experts shared the research questions with other professionals who were suitable for the study and also forwarded their own written insights. Additionally, another expert had a hectic production schedule, and therefore declined to participate in an interview. However, the expert’s email identified the generic business models used by the represented company, which was described in the key terms. All these data were used in the analysis.

During the data collection interviews, the researcher used active listening and adaptability skills to foster an open and responsive environment by attending to the participants’ reactions. In the course of the formal interviews, the researcher used both follow-on and additional questions to encourage more in-depth responses from the participants. It should be noted that the questions were adjusted based on the participants’ responses in order to explore the emerging themes in a greater depth, while also taking into account the definitions and components of the business model. In some cases, the experts introduced new topics by themselves. Most of the experts were willing to answer the questions in detail, often going beyond by explaining the general situation of the market and the industry as a whole. If the experts were, for instance, company owners, their perspectives naturally drew upon their own business experience. It should be noted that the participants could have opted out of the study at any time and had an opportunity to decline to answer particular questions, and they were not obliged to respond to all questions asked.

All the participants in the study were informed of the results of the interview analysis regarding their statements in the category and subcategory tables. This transcript validation was used to enhance the reliability of the collected data and to verify that the transcription was completed correctly according to their responses. This is especially important in order to ensure that the data are valid and reliable when it comes to foreign language transcription. Each participant was also informed of the final results of the study, and their position regarding the conclusions was included so as not to be misunderstood or taken out of the context to finalize the reliability of the data. Identifiable participants were provided with access to the manuscript, and gave their explicit formal consent via email. They were also given the opportunity to review the results pertaining to them and to request corrections should any inaccuracies be identified. Additionally, all the participants – except for a few who were deemed ineligible – were given the opportunity to review the final version of the manuscript after the peer-review process and prior to publication. In the case of a few participants who could not be reached, it was determined that their contributions and identifiability do not affect the integrity or ethical compliance of the publication.

The limitations of the study included several factors. First, there was restricted access to potential study participants. Communication and data collection were also significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, which introduced additional organizational challenges, particularly in relation to the participants’ employment schedules. Furthermore, a large number of recipients did not respond to the invitation emails. Language barriers – since the researcher was only able to communicate in English – and the closed nature of the industry also contributed to a limited overall response rate.

Second, the small sample size should also be acknowledged as a limitation. As a result, the findings are not fully representative of the wider population. Further research is needed, as the results cannot be considered fully reflective of the business model components employed by the broader spectrum of independent film production companies operating within the European film market.

Analysis and Results of the Study

The interviews ranged in duration from 40 minutes to 2 hours, totaling approximately 1062 minutes. The interviews were then transcribed and analyzed by using the MAXQDA software with the experts coded by using codenames D1 through D17. The data were analyzed by using thematic analysis, which may function both as a tool for reflecting reality and for uncovering or deconstructing its underlying structures (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Through this method, 11 categories encompassing 60 sub-categories were identified from the interview material. It should be noted that only one researcher conducted the analysis, and reviewers were not involved in the validation of the study data. However, double-checking was employed to ensure adherence to the established coding principles. A detailed and systematic analysis was followed during the coding process and emergence of categories (themes). The process begins with the extraction of meaningful text segments, which are then assigned initial codes. Next, common codes across the transcript were grouped to form sub-categories. Finally, these sub-categories were logically organized into major categories and central themes based on their relationships. It should be noted that, during the coding and categorization of the data, the researcher observed a tendency for the vast majority of categories to be reflected in company business model sub-constructs. Therefore, the analysis takes these sub-constructs into account, contributing to greater conceptual clarity.

The first theme identified was “Business Model Features of Independent Film Production Companies in the European Film Market: Value Creation”, and it is comprised of four categories and 13 sub-categories. It should be noted that, according to the research experts, animation is considered a separate industry. Therefore, animation companies were not included in this study.

Category 1: Capabilities. The data analysis revealed that European independent film production companies typically have between 1 and 10 permanent employees, while all the remaining crew are freelancers. However, a company can have up to 200 permanent employees, depending on the size of the independent film production company. Expert D11 pointed out that the company focuses on writers and producers, which is why they are employed by the company, with a total of 10–15 people working for the company and the rest being freelancers. The researcher concluded that small film markets, such as Lithuania, Latvia or Finland, are dominated by small companies with few permanent employees.

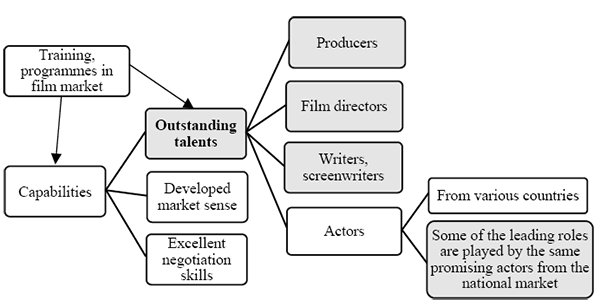

The analyzed empirical research results are presented in Figure 1, where the critical components can be seen that make up the sub-construct Capabilities of a company’s business model.

Figure 1. Key Components of the Company’s Business Model Sub-construct: Capabilities

When analyzing the data presented in Figure 1, the highlighted components are bases of the company business model. Outstanding talents is a critical component of a company’s business model. After analyzing our experts’ statements, it is evident that the importance of outstanding talents lies in their role in critical capabilities for independent film production companies. For example, according to Expert D11, the film value chain is controlled when there are talents who offer high creative potential. From a strategic point of view, talented producers and writers are among the most important contributors. As far as producers are concerned, this is partly shared by Expert D16, as every film project has a leader (producer) who tries to develop the project in order to get it to the production and post-production stages, and the film premiere.

When it comes to content development, a company needs talent in a general sense. It is suggested that if a person has talent, he or she can create unique content. Expert D15 agreed to some extent, by sharing his personal experience dating back to a period when he was unable to raise the money needed to produce a feature film. The research participant used his talent to make a film with almost no money (Researcher’s note: the producer was also the director and the scriptwriter). Obviously, the team was small, and current technology was used. It is said that it is possible to make a film by using an iPhone, but it is all about how it gets done, the idea and so on, and it all depends on talent.

Expert D1 highlighted that a film star is one of the key marketing and sales tools used to attract mass consumers on a global scale. However, independent film production companies face problems of financial capability because, in order to hire world-class ‘A-list’ actors to star in a film, the company must pay royalties to the tune of dozens of millions of US dollars.

However, regarding the film festival market, Expert D17 provided a different approach. Currently, the mentality now asks for different content, or for different talent. Therefore, the question of finding the right talent is generally difficult.

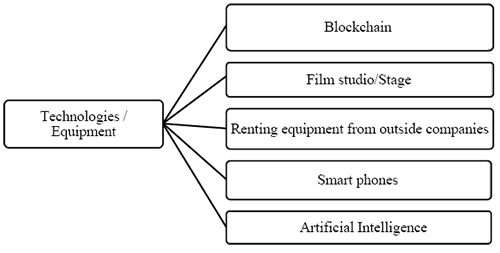

Category 2: Technologies/Equipment. The analyzed empirical research results are provided in Figure 2, where the key components can be seen that make up the sub-construct Technologies/Equipment of a company’s business model.

Figure 2. Key Components of a Company’s Business Model Sub-construct: Technologies/Equipment

When analyzing the data presented in Figure 2, it should be noted that a film studio is treated as a means of a production tool. According to the interview data from Expert D11, larger film production companies have their own studios. However, if a company realizes that it is not within their capacity, more emphasis is placed on creation, control, and production. For example, interview data suggest that the Lithuanian film market is dominated by film production companies that do not have their own means of production: technique, equipment, etc. According to one expert, in the Latvian film market, a production film company and one of the largest film studios (with stages and sets), although owned by the same producer, are separate legal entities. The researcher assumed that the creation of a separate legal entity allows better management of the company’s financial risks.

During the interview, one of the experts touched on the topic of artificial intelligence, the use of which in filmmaking is controversial and is a separate area of research. As stated by Expert D2, there is currently an experiment in which a film script is provided to AI, and artificial intelligence analyzes it, and, by using big data, proposes the film execution plan: from actors to marketing tools. However, it is questionable how this will affect the content variety and whether it will truly benefit film as a form of art, particularly given the growing uniformity in the content being produced. It is also noticeable that any algorithm, although projected into the future, will reflect on the past. Therefore, if films are produced according to the historical past, it is likely that the content of the films in the industry will become more uniform and less original. In addition, another aspect regarding the use of artificial intelligence in the production of film content is noted. Participant D6 gives an example with the film Another Round, directed by T. Vinterberg (2020), which received an Oscar award in 2021. If artificial intelligence (big data analysis) is used to create a film, the question is the following: whether the content of the film would have met all the requirements since the film is about four white middle-aged men who consume alcohol and teach children. It is believed that artificial intelligence would not have allowed such content to be created. Thus, the emphasis is on the created sense of a market without relying on different technologies. The researcher concluded that, for filmmakers who make films of high artistic value, a developed sense of the market which artificial intelligence cannot provide is important. Films of high artistic value pose problems in society and often address painful topics that do not meet certain standards (perhaps even political ones), and thus there is no point in homogenizing the content of all films to suit the consumers, especially the mass consumer. As observed in the study, the implicitly mentioned mentality, values, etc., currently prevailing in the film industry, sometimes go to certain extremes.

The study has revealed that one research participant developed a blockchain-secured crowd investment model. It is currently being tested with the film production. According to the expert, this technology provides a model based on the creation of a fan base that can finance the production of a film. In the blockchain process, the production company, thus, reduces the administrative processes of the film, and, for investors, provides transparency and security that they will receive their money automatically, and that they do not have to wait for a producer finally providing funding as it is all automated.

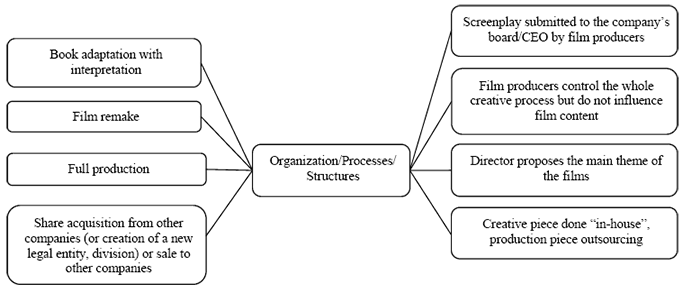

Category 3: Organization/Processes/Structures. The analyzed research data are presented in Figure 3, which represents the key components of a company’s business model sub-construct Organization/Processes/Structures.

When analyzing the data presented in Figure 3, Expert D1 noted that feature film management and process organization are more complicated than the equivalent work for documentary films which do not require a large creative team. Every film has its own organizational processes. Concerning the analyzed data regarding the sharing of the producer and director functions in making the film, the results suggested that, in general, the director is responsible for the content of the film and, for instance, according to one expert, the director has full artistic rights, and so producers cannot legally demand from the director what he or she may not want to do. This was clearly indicated as an example in Denmark. Expert D1 also stressed that the director is responsible for the content, while the producer should not be in charge of the creative aspects. Expert D11 emphasized that the production of a film (Researcher’s note: specifically from the pre-production to the post-production) is a team effort. In the company, the screenwriter is responsible for the script, whereas the director produces the film based on the script. Certainly, during the production of the film, if the director has certain observations or ideas about the content of the film, he or she can make comments, and may discuss the relevant points with the scriptwriter and the producer. It should be noted that the producer of the film works from the beginning of the film – i.e., from the writing of the script (working with the screenwriter) and is responsible to the company for the ongoing film project. The script is therefore proposed to the company’s board by the producer, and not by the director. According to the statements by study Experts D6, D11, D13, D15, and D16, the producer (including the company) has some control of the project (financial responsibility). Still, attempts are made to maintain a certain balance between the producer and the director, to solve the encountered issues, and to find a consensus.

Figure 3. Key Components of a Company’s Business Model Sub-construct: Organization/Processes/Structures

Expert D15 noted that it is sometimes difficult for producers to understand filmmakers who have a specific way of making films, especially those just starting in the film industry. All this leads to high investment risks, and some producers refuse to take the risk without foreseeing the film’s success. It is suggested that more experienced directors with name recognition have less challenges as producers trust them because they know that the director will deliver something that has an audience.

Expert D16 identified two production models:

• The American film production model – the production company employs a screenwriter, and only after the screenwriter has finished the script, the director is hired.

• European film production model – the director is the key person, and he or she is looking for a production company that can help him make a film based on his or her ideas, while bringing the script with him/her.

Expert D16 shared personal experience that the theme of one film was developed by the producers (the company) and was presented to the director, but, routinely, the central theme of other films comes from the director.

It should be noted that Expert D13 emphasized the importance of work ethic. For example, D13 stated that, in the Lithuanian film market, directors are usually freelancers (talents), and they work with the same producers. If the director has a new idea for a project, he or she will first suggest the concept to a producer with whom s/he has already made several films. If the producer opts out of a new project, the director then suggests the idea to another producer. Of course, the process may be reversed where the producer suggests a project to a director, etc. It is important to note that headhunting does not exist in the Lithuanian film industry. Notably, in the general film industry, talents have agents, and the process takes on certain business rules.

According to Experts D2, D5, and D1, some film production companies adopt a film remake approach. This strategy involves acquiring and localizing a film script, adapting it into a format that has already generated profits in other markets, and tailoring it for the national market. For example, in Lithuania, film production companies predominantly use this approach to produce comedy films. The researcher concluded that the company, by producing films in this way, can more accurately calculate the potential profit and user segment. This approach is a form of risk reduction while securing film payback. However, study Expert D6 noted one subtlety: making such films is “very easy and boring”.

Regarding organizing film production activities in-house and outsourcing to external suppliers, the analysis of Experts D7, D10, D13, D12 insights disclosed that a production company controls the pre-production3, production, and post-production stages. It is only noted that the post-production of a film is usually done by external companies. Expert D5 stressed that while the creative aspect is done ‘in house’, the production part (rental equipment, staffing, and so on) is typically outsourced.

Expert D11 observed that broadcasters have sold or no longer hire production companies in the Nordic countries market, and primarily work with external production companies. In general, in-house companies are becoming a problem, and thus it is not an advantage for a production company to be part of a broadcaster’s company.

Additionally, according to Expert D1, the European film market is dominated by companies which do not cover the distribution stage of the value chain. According to research Expert D9, the independent film company Constantin controls the entire value chain by owning the television and cinema units, and has an export unit and links with other companies. Expert D6 stated that Zentropa covers all stages of the film value chain, except for distribution in cinemas (Researcher’s note: 50% of the shares are owned by Nordisk Film (Strandgaard, 2011)), thus covering the value chain of the film. However, according to Expert D6, the company Zentropa has a separate company for international sales. Thus, the company sells not only its own films but also films produced by competitors. Most of the films produced in the Nordic countries film market are sold. It is important to note that the company has a film studio, and the whole filmmaking process takes place in the same territory. Study participant D17 notes that the company’s best position on the market is at a time when the company is exploiting the full vertical integration business model.

Category 4: Partnerships. The data analysis revealed the key components of a company’s business model sub-construct Partnerships, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Key Components of the Company’s Business Model Sub-construct: Partnerships

When analyzing the data presented in Figure 4, the highlighted component is the basis of a company’s business model. Key stakeholders include different types of investment partners like film funds, country and regional government bodies, venture capital funds, private investors, banks, crowdfunding, broadcasters, and intermediate investors such as distributors. It should be noted that it depends on the size of the market. For example, key stakeholders may provide funding through hedge funds, loans for film productions, and completion guarantee – funds that will be provided for completion of the work – and are systematically active only in larger markets. Expert D2 stated that venture capital can be exploited within the company itself when certain investors diversify their portfolio and invest funds in the film production company. However, the company has to demonstrate a good track record and make a unique proposal, so that business angels or similar venture capitalists would consider investing in such a company.

Expert D8 pointed out that distribution companies are a type of a partner because they have certain knowledge regarding successful distribution and can therefore assess the script. Thus, the cooperation with the distribution company develops from the script of the film in this example. The researcher concluded that the distribution company becomes not only an investment partner, but also partly a partner of the film itself in terms of its content. For instance, research participant Expert D16 noted that there is an effort to start cooperation with sales agents and distributors at the development stage.

Europe is dominated by co-production. According to Expert D2, this is encouraged because each film has a chance to enter another market when there is collaboration between talents. Additionally, Expert D16 emphasized that co-production is also financially beneficial. Since it is challenging to obtain all necessary film production funds from one country, partners from other countries are sought. Expert D15 gave an example from his own experience of working with companies from countries such as Croatia, Slovenia, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Azerbaijan, and others. It was also noted there is also a desire to cooperate and establish links with companies in the Middle East and the United Arab Emirates.

The second theme of “Business Model Features of Independent Film Production Companies in the European Film Market: Value Proposition” is comprised of five categories and 27 sub-categories.

Category 1: The socio-cultural context of a country. The size of a country’s population has an impact on independent film production companies. According to Experts D1, D2, D6, D7, D8, countries such as Lithuania, Latvia, or Denmark are classified as small markets, whereas countries such as Poland and Germany are perceived as large markets. According to Experts D1 and D2, the market determines the production volumes and opportunities, and what may be progressive on a European scale may not work on a small market. Expert D8 noted that, in a small market, it should not be limited to the national market only. Expert D15 noted that if the population is less than 1 million, films are produced with an eye on international markets, as it is very difficult to produce for a national market. Finally, Expert D2 suggested that, in Poland, a company can produce films for the national market and can pay back. If the film has a budget of around 1 million Euros, it would have a better return on investment in a large market. Expert D6 made a comparison between Germany and Denmark. If an arthouse film is successful in Denmark, it will be seen by between 10% to 15% of the population, approximately 500,000 to 800,000 viewers. However, when compared to the population in Germany, 10–15% of the population would be approximately 8–12 million viewers.

The data analysis revealed that some companies produce 1–2 feature-length films per year, while others produce 4–5 films a year or more. Many small active companies also carry out co-production projects as co-producers. The study also revealed that, in the European film industry, the size of film production companies is a developing trend. The European market is increasingly dominated by very small or very large companies with very few medium-sized organizations. Expert D9 suggested that independent film production companies are increasingly struggling for financial resources and do not have sufficient funds to invest in the development of new projects, i.e., financially risky projects. This was also mentioned by Expert D2, and, based on statements by these experts, it is suggested that the number of very small and medium-sized independent film production companies will decrease, and they will be absorbed into big companies.

Expert D13 touched on a new topic by noting that in order to have a variety of content of films in the market, and not just for the mass audience, the funding issue is part of the cultural economy. The film industry is not just about profit, and this also touches upon major US film studios where certain films make a profit, while other create a loss. Therefore, major companies maintain and finance films that hold their position in the market.

When analyzing category 2 “Markets”, the market is primarily distinguished by a territory:

• National market – films produced with local film stars and exhibited at the national market.

• International market – films exported to other countries.

Expert D15, based on personal experience, stated that the company sells films to Arab countries because it is one of the emerging markets where there are also opportunities to be taken. The researcher concluded that while there is a focus on the international market, searches for potential opportunities outside the European film industry are being explored. According to Experts D2, D13, and D17, if a film has suitable story – or a ‘universal’ story – and it is perfectly conveyed, the film may be viewed in various countries around the world. For example, Lars von Trier created the television series Kingdom, and according to study participant D6, ‘opened up’ international markets. At that time (Researcher’s note: circa 1994), Danish films were not exported to other countries until the company Zentropa was the first to begin successful export of films. The researcher noted that the films produced by this company were exceptional in their theme, style, and form. From this, it can be suggested that the nuances of making films for the international market were addressed and achieved. The series Kingdom received national and international awards. Study participant D13 stated that the Dogma 95 movement made this company and Danish cinema in general more visible in the world market. Currently, some Danish actors are internationally known. The researcher noted that the actor Mads Mikkelsen, who also stars in films produced by Zentropa, also received offers from companies in Hollywood. Such projects offer an opportunity to draw attention to Danish films, and companies may increasingly export films to international markets in the future and try to enter the American market. Expert D17 also emphasized the importance of actors, and thus actors from different foreign countries are chosen in the particular film.

Based on the statements, a distinction is made between film classification according to the markets where they are exhibited:

• films focused on cinema market;

• films focused on broadcasters and streamers’ market, and;

• films focused on film festivals market.

It should be noted that a film can cover several markets at once. According to Expert D17, the majority of producers use a business-to-business (B2B) model. This means that a film production company does business with a sales or distribution company or a TV channel. It should be noted that, according to research participants Experts D14 and D9, companies not only produce films for the cinema or broadcast market, but also direct production of TV series, films for broadcasters, and streaming company services.

Expert D14 noted a particular business model where broadcasters and streaming services share networks and territories and other new ‘frenemy’ financing/rights constellations depending on the individual qualities and potentials of the projects, and innovative financing models created by producers and distributors.

Regarding the expansion of a film production company into other markets, Expert D2 named Zentropa as a good example because it has a presence in major markets. Expert D6 also confirmed that Zentropa had and still has companies in other countries: Germany, Sweden, and Belgium. According to Expert D15, for example, Luxembourg is a small country, however, companies from other countries have acquired shares in film production companies there. According to the experts, the company’s expansion into other markets makes it possible to conduct co-production among themselves. According to Expert D1, the most common ‘merger’ of companies is through film clusters. When analyzing the statements of research participants D15 and D6, it is noticeable that subsidiary companies are set up for film sales and distribution. Expert D6, based on personal experience, emphasized that, in the Nordic countries’ film markets, there are 2–3 sales companies as a specialized business. Therefore, the film production company has the largest film sales company in the territory and is the only service provided to other film production companies.

Experts D2, D13, and D17 emphasized the importance of the audible language used in the film in order to enter international markets. Experts D2 and D17 argued that a film made in English is denoted by greater potential in the international market. Interestingly, Expert D13 noticed a certain nuance in language. Every film can be translated to every other country’s language by using, for example, subtitles. However, as for the original language heard in the film, international audiences are more inclined to such language which is close and familiar (for example, Italian, French, or English languages), because it creates a certain sense of comfort.

Category 3: Proposition. According to Experts D1, D15, D16, D17, and D11, the classification of independent film production companies concerning the nature of the film being produced are the following:

• producing feature films;

• producing documentary films;

• producing feature films and documentaries;

• producing animated films, and;

• producing movies and series for television.

It should be noted that a company can produce not only documentaries, but also feature films, etc. According to Experts D2, D4, D5, D8, D10, and D13, there is a further differentiation of companies in the market based on intellectual property:

• film production service companies, and;

• film production companies that create content, i.e., creators of intellectual property.

According to Experts D13 and D2, film companies create content and also provide film services for other film production companies from other countries. As noted by Expert D2, based on personal experience, this activity involves a profit margin and increases the financial stability of the company. Expert D10 argued that, in most cases, film production companies own the intellectual property, creative content, and monitor the production.

The European film industry is dominated by arthouse film production, according to Experts D3, D12, and D17. Experts D2, D13, D11, D7, and D17 also suggested that there are also companies that produce only mainstream films. In the Finnish film market, for example, film production companies produce more mainstream than arthouse films. According to Expert D17, mainstream films produced by European companies are not equivalent to mainstream films produced by US companies. According to Expert D2, major Hollywood studios do not focus on artistic inspirations and would not risk their business, for example, with the Danish director Lars von Trier’s films. According to research participant D15, companies can produce films that are in between commercial and arthouse film. Study participant D6 suggested that it is just as useful to invest in a long-lasting arthouse film, which can have viewers even after 15 years. At the moment, the viewer can very easily watch a standard mainstream movie from Hollywood companies, and so it is easier to export arthouse films. However, arthouse films should not be interpreted as uninteresting or boring. Instead, the general consensus should be that arthouse films are interpreted more as ‘entertaining’. In general, the study suggested that these terms raise some issues of usage in the European film industry. In this article, the artistic nuances of the films are not explored. However, it is believed there can be classification of film production companies, and these companies produce films for the mass consumer base and high artistic quality, specialized films.

According to research participants D9, D6, D2, D16, D15, and D17, some film production companies are involved in the production of advertising, marketing campaigns, and other ventures in this sector. Larger companies have separate advertising departments. According to Expert D6’s personal experience, a company was initially ‘very commercial’ and tried to squeeze money from the advertising industry. Expert D2 noted from personal experience that a company may produce commercial videos and offer advertising services for international markets. According to the study participants D15, D16, and D3, film production companies are not only involved in the production of films, but also in the distribution of music and the production of music videos and other media. According to the material provided by study participants D10 and D6, independent film production companies have a limited opportunity to develop what is not their main activity. In regard to personal experience, Expert D6 claimed that switching to a different type of business would result in financial failure.

During the interviews, experts touched on film genres. For instance, two experts stated that Scandinavian film production companies have developed a Scandinavian crime drama. Expert D11 noted that the German film market is also paying more attention to crime dramas. As far as the comedy genre is concerned, the researcher assumed that comedies tend to be localized in each market primarily according to the culture of that country, as well as other contributing factors. However, research participant D15 suggested, based on experience, that comedies can be successful internationally in a variety of markets without being localized. Expert D2 highlighted that the film content is increasingly becoming similar and uniform for consumers. To counter this trend, it is essential to educate audiences. Experts D2 and D13 also emphasized the critical importance of uniqueness in the film content.

Participant D11 observed that the budget and margins for an arthouse film tend to be low. Therefore, companies that focus only on the mainstream film, the TV drama genre, and the production of the arthouse film raise the level of creativity of the company. The researcher noted that the production of the mainstream film also requires a certain level of creativity, depending on the artistic quality of the film or series being produced, and that the term ‘creativity’ should not be associated with arthouse films only.

The researcher assumed that, in the European film industry, these are some exceptions, where theme parks are created based on films and characters created by an independent film production company. This is partly confirmed by participant D9, who stated that film merchandise is more likely to be sold than theme parks. Research participant D15 highlighted the personal experience of developing merchandise (e.g., T-shirts) on the national market and on an online platform. According to participant D10, however, merchandising is rare in the European film industry. Participants D17 and D16 further suggested that if an arthouse film is being made, there is no market for the sale of the film’s merchandise. According to participant D16, the European film industry does have a venue for the sale of film merchandise for children’s films and certain comedies.

Category 4: Channels. The data analysis revealed that film production companies, particularly in small markets, assess whether it is more advantageous to collaborate with a distribution company or to distribute their films independently. For international distribution, it is generally more effective to partner with international film sales companies, as each market has unique characteristics that are challenging for producers to navigate without specialized expertise. It is interesting to note that Expert D11 observed that French film distribution companies are more willing to cooperate with Nordic film production companies than, for instance, with German film production companies.

Expert D9 pointed out that it does not make sense for a film production company to have its own screening platform unless it is a big company in the film market. Expert D17 stated that an experiment was underway where a film production company planned a global release of the film at the same time. It was believed that the film was in production, and would only be profitable if this exhibition method is chosen. If a film production company has a product that a consumer wants to see, the film is watched on a platform created by the producer. The only problem with platform marketing is how to reach the consumer. In general, territorial distribution systems are not designed for the 21st century film industry, and it is expected to change in the future. According to Expert D9, it is likely that the future of the European film industry will increasingly involve the development of a system of virtual cinemas in which digital streaming ‘rooms’ are developed. For example, a project of this kind is underway in Germany. In the opinion of study participants D7, D12, and D9, this approach was influenced by the COVID-19 period, where the vast majority of new films produced by European independent film production companies waited for cinemas to open.

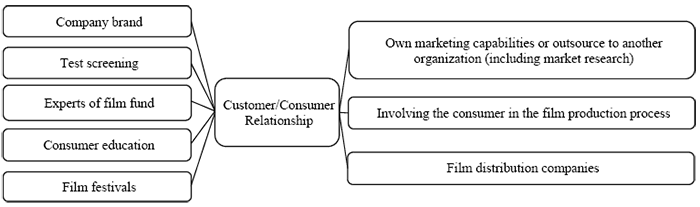

Category 5: Customer/Consumer Relationship. The data analysis revealed the key components of the company’ business model sub-construct Customer/Consumer Relationship, presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Key Components of the Company’s Business Model Sub-construct: Customer/Consumer Relationship

When analyzing the data featured in Figure 5, according to Experts D2, D5, D16, and D15, the marketing of films is carried out by film production companies, film distribution companies, sales companies, or hired marketers. However, Expert D6 observed on the grounds of personal experience that when a film production company does its own marketing for a film, it becomes more accurate, that is, closer to the film being produced. Obviously, freelance marketers are bought in, but the film production company controls everything.

When a film production company produces films for the film festivals market and enters the acclaimed film festivals, it becomes a strong film marketing tool. According to research participant D8, participation in film festivals gives the film a certain brand and helps to market it. Moreover, according to Expert D13, festivals are a kind of platform where the producer meets the buyer, and the film becomes recognized and acknowledged by film critics. Similarly, research participant D6 stated that if a company does not have a large marketing budget, marketing at festivals such as the Cannes Film Festival, the Berlin Film Festival and the Toronto Film Festival is partly free. All well-produced films can receive international recognition, and the various press outlets that appear during and after the festival become extremely important resources.

According to Expert D16, some film production companies organize various discussions and parties related to the film’s theme. The study revealed that this enhances involvement of the consumer in the product. In many instances, film production companies use the traditional method of test screening. Expert D10 observed that film distribution companies want test screenings because they use data and have a target audience. According to Experts D6 and D15, the unfinished film is shown as many times as possible to the audience. Expert D6 observed that this gives more opportunities for the produced film to communicate with the widest possible audience in the national and international markets. According to research participant D15, for example, film production companies in Luxembourg have the opportunity to understand the German and French mentalities. Everyday communication takes place in at least four languages, and there is the opportunity to organize test screenings of the film, while attracting as diverse an audience as possible, regardless of their origin, language, etc. In addition, in the event of multiple applications for funding, according to Expert D1, the end consumer is represented by experts. During the study, Expert D17 discussed an experiment with a film which was in production. When Business to the consumer (B2C) is implemented, fans of the film are involved in the production process, but they do not know the full storyline, and the script is not revealed. In this way, filmmakers get a better feel for consumers and try to understand what they like. It is important to note that, for this approach, there must be a relevant film on offer (regarding the nature of the film, its theme, etc.).

What regards the identification of customer and consumer demand for a product, i.e., investment in market research, Expert D9 noted that large companies have market research departments. In addition, in markets such as Germany, there are companies specializing in film market research, and they have all the necessary tools. Therefore, larger film production companies can buy the services, while smaller companies do not invest in market research. The researcher concluded based on the data that companies do not have enough money to invest in market research. According to Experts D1 and D13, producers and directors, based on intuition and experience, understand what can work and what does not work in the film market. Expert D13 stated that the film industry identifies key indicators and will often know soon enough if a film is suitable.

The study has also revealed the importance of the film production company brand. Expert D11 emphasized that, for small film production companies, the focus on producing only 1–2 films per year suggests that the company brand is not very important. For companies that produce three or more films or want to cover as many stages of the film value chain as possible, the company’s brand is essential. According to research participant D6, a company’s brand must have an impact. Expert D2 claimed that Zentropa is one of the best examples of how to develop a company brand. Expert D6 also stated that a strength of Zentropa is its uniqueness, and it is different from other companies, whereas one of these differences is its talents. The talents were described as a bit crazy, and regarded as not only funny, but also a “Viking-type” of a producer. The researcher concluded that the company seeks to provoke, while at the same time seeking freedom in art. All problems are solved creatively and provocatively. For instance, when the Cannes Film Festival declared director Lars von Trier ‘persona non grata’, the company threw a response party, and the statement became part of the director’s and the company’s brand, with the director appearing in the press wearing a T-shirt with the festival’s logo and the message: “Persona non grata. Official Selection”. The same T-shirts can be purchased by the public. All of this further empowers the company’s brand impact in the film industry.

The third theme of this research is “Business Model Features of Independent Film Production Companies in the European Film Market: Value Capture”, and it is comprised of two categories and 20 sub-categories.

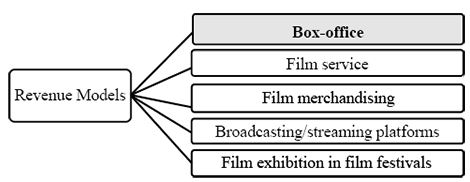

Category 1: Revenue models. The results of the data analysis identified the key components of a company’s business model as a sub-construct: Revenue models as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Key Components of Company Model Sub-construct: Revenue models

When analyzing the data presented in Figure 6, the highlighted component is the foundations of the company’s business model. Independent film production companies generate most of their revenue from cinema ticket sales (box-office). It should be noted that this goes back to the period before the COVID-19 pandemic. Expert D2 noted that, in cinemas, the exhibition format is copyright-protected, allowing producers to program a specific number of film screenings. Regarding data transparency, Experts D2 and D6 highlighted that some of the largest streaming platforms (e.g., Netflix) do not share viewing data, such as the number of viewers or film ratings, with the producers. Additionally, Expert D2 observed that, when a film is shown on a streaming platform, the producer’s revenue share is often disproportionate to the film’s success, with streamers retaining a significantly larger portion of the earnings.

Expert D8 highlighted that film licensing is a good business because film licenses can be sold repeatedly for a certain period of time in many countries. Expert D2 noted that increasingly when streamers root in the European film market, film production companies lose the possibility to exploit film licenses. According to study participants D2 and D7, the business model of a streamer is based on film licensing, where a company pays a one-off premium to a film production company and takes the licensing of the film globally. As the experts further explained, this is when a film production company sells a film license to a streamer and no longer has the right to sell the license to a TV channel. However, it is worth noting that Netflix is becoming more flexible regarding this issue through the use of success fees.

Expert D17 noted that independent film production companies have problems making a profit from their films, because the sales and the distributions companies earn their profits from it. According to Experts D7 and D8, a minimum guarantee (MG) and an additional film distribution fee are deducted from the revenue. According to Experts D1, if a company focuses on the production of films of high artistic quality, in the arthouse film sector, there is a high probability that the investment will not yield the required return.

According to Expert D1, an intriguing example was presented where a company that produced a film opted to release it directly on YouTube, thus making it freely accessible for viewers. However, the company generated revenue from the sale of merchandise for the film and thus recovered its entire investment in the film. Expert D17 shared personal experiences during the study. There was a unique case in the film industry where a film’s merchandise was sold for almost €250,000 before even making a film (Researcher’s note: the amount varies as the processes were still evolving when this study had been completed). This approach was used to start and expand the fan base.

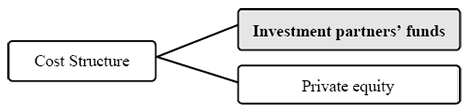

Category 2: Cost Structure. Figure 7 shows the summarized key components of a company’s business model identified as the sub-construct Cost Structure.

Figure 7. Key Components of Company Model Sub-construct: Cost Structure

When analyzing the data presented in Figure 7, the highlighted component forms the basis of a company’s business model. According to Experts D15, D17, and D6, independent film production companies are mostly dependent on public financing. Expert D6 observed that, in small markets, such as Denmark, it is not possible to make a film without public funding. While it was stated that it could be done for larger populations such as Germany, France, and Italy because of greater opportunities, it is still very difficult to generate income. According to research participant D9, in markets such as Germany, there are companies that invest part of their funds in film production, but also address film funds. According to Expert D12, a feature-length film was made in Latvia with the company’s funds and sponsors’ money (a small part), but this is an exception. According to Expert D2, for example, in Lithuania, some films, mostly comedies, are produced by private equity funds, without public funding. However, investments depend on related financial indicators. Venture capital funding becomes challenging because, as the production volume grows, films compete for the same audience, which results in lower ROI. It should be noted that the vast majority of the Lithuanian industry revenue comes from the film services for other companies from other countries.

According to Expert D17, theoretically, if the right investors are attracted, it is possible to produce a film without public funding. However, a doubt exists if the film can recover the investment with the distribution system that is currently being used in the film industry. If somebody produced films with crowd-investing and released it globally on the same day on own platform, it may generate the necessary revenue, but this is not a sustainable business model because there is not enough revenue.

Expert D10 highlighted that the margins in film production companies are used to develop new ideas, as they are usually small and do not allow for investment. According to the personal experience of research participant D15, if a film production company is not able to obtain the total amount of a film’s budget, it invests in the production of the film in the hope of recouping its investment through its existing distribution company and thus preserving the intellectual property of the film.

Experts D2, D1, and D3 noted that every film is like a start-up. According Expert D17, it is necessary to produce as many films as possible with the hope that some of them will be successful. However, independent film production companies do not have this financial capacity. The European film industry has a very slow funding system based on subsidies, which have certain limitations. It was observed that American streaming companies are competing strongly with European film production companies because it is easier for them to finance the production of films, thus creating a ‘brain drain’ of the European film talent.

According to Expert D6, films produced by film production companies can be financed by streamers when working directly with major global streaming companies like Netflix. However, the film then becomes the property of the streamer. Therefore, Expert D6 disclosed that it is better to produce a film in such a way that all intellectual property rights belong to the film production company rather than to its competitors. An example of this is the presence of films made 30 years ago and owned by the company. The researcher assumed that it is a long-term investment, that film licensing is exploited, and that the film may achieve international recognition, receive awards, or even be recognized as a cinematic classic, among other possibilities. In general, Expert D17 noted that the American system coming to Europe is different due to differing intellectual property rights.

The data analysis revealed that tax incentives are used in some countries. For example, in Latvia, a cash rebate is being developed for film production. Luxembourg also used tax relief for film production, but it has since been abolished. According to Expert D11, the tax credit encourages, for example, post-production in countries such as Finland, Belgium, and the Baltic States.

During the study, one of the experts mentioned that, in general, in the film industry, especially in the US, film companies use Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV). As this risk management model was only mentioned by one expert in the study and there is no detailed information on the European film industry, the researcher asked additional questions to the other experts in the study. This financial model of risk management is not widespread in the European film industry. According to research participant D9, it is used for large international co-productions. For instance, Babelsberg Studio had a special purpose vehicle for its major films. However, it is not common among smaller film production companies. Research participant D1 noted that smaller film production companies do not use an SPV, although there is a need for it. All possibilities depend on the available budgets. Research participant D11, based on his personal experience, stated that the company uses a SPV in some productions.

If, in the future, film premieres will take place not only in physical cinemas but also on broadcaster platforms (S1), Expert D11 highlighted the problem of controlling the ‘waterfall’. Film production companies will then have a problem with generating revenue from a film. According to research participants D13 and D11, intensive negotiations take place on the first levels, especially if there is a distribution company involved. For example, if a film production company receives a soft loan from the film fund for a film, it will usually be in the first tier. If a film sales agent acquires the distribution rights of a film, he or she pays MG and usually takes the first level of the ‘waterfall’, followed by a distribution fee and so on. Of course, the number of investors determines the number of ‘waterfall’ levels, and the ‘waterfall’ level is negotiated. According to research participant D11, a film production company receives some offers from other business sectors such as real estate companies to collaborate with them on investing in production, but then there are questions about the provisions because of the use of ‘waterfall’ control. It has been observed that small investments tend to be subject to unfavorable conditions that reduce the potential profitability of the film production company.

Discussion

As the empirical research unfolded, outstanding talents were found to be a critical part of a company’s business model. However, this study raises many additional questions regarding talents and the film content, because the current mindset in the industry wants a certain type of film content and talents. This study also raises questions about using AI and content levelling. These are quite broad topics and would require interdisciplinary research to discuss and get a holistic view about the film industry and independent film production company’s development possibilities.

Large sums of money or extraordinary financial success in this industry is not the main driving motivation. According to Finney & Triana (2015), “Ownership, recognition, appreciation and responsibility tend to be more important and persuasive drivers than simply being paid large sums of money” (p. 194). In addition, some creative individuals are motivated by artistic ambitions. This is partially supported by one expert’s account of producing a film with a small team and almost no budget, relying primarily on personal talent. Of course, a more detailed analysis – including financial and socio-cultural factors – would be necessary, followed by a comparative assessment. One could also argue that it is not only recognition and appreciation that matter, but also the pursuit of creative and artistic challenges. Continuously producing the same type of film may result in a sense of routine, which can diminish creative fulfilment. A company with certain artistic ambitions and challenges chooses a more complex, but perhaps more interesting, business model.

A problem raised by this study is that it is difficult for producers to understand filmmakers who have a specific way of making films, because this leads to high investment risk and refusal to take risks without foreseeing the film’s success. This allows the development of a new field of inquiry into the producer’s strategic–creative thinking of how to encourage innovative ideas while at the same time measuring and managing the financial risks of the whole company, and not just the film. At what point does it make sense for a company to take a very high risk and be on the verge of a foreseeable major failure, but still produce films and hope for their success? Of course, this is also where the ‘development market sense’ is mentioned by the experts. It also depends on the criteria for assessing the success of a film in the short or long term.

It is assumed that the production of film remakes can be used during periods of a significant revenue decline, particularly for companies that specialize in arthouse films. Also, this model may be helpful for a company that has only been in the market for a few years to fund future ambitious artistic projects. In this way, there is a greater chance of securing a certain success for a film, and, of building future relationships with investors.