Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika ISSN 1648-2425 eISSN 2345-0266

2023, vol. 27, pp. 58–83 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2023.27.4

A Systematic Literature Review on the Relationship Between Quality of Work and Intentions to Retire Among Individuals Aged 50 and Older

Antanas Kairys

Vilnius University, Institute of Psychology

antanas.kairys@fsf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8082-8016

Raimonda Sadauskaitė

Vilnius University, Institute of Psychology

raimonda.sadauskaite@fsf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0514-1086

Olga Zamalijeva

Vilnius University, Institute of Psychology

olga.zamalijeva@fsf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9186-8440

Halldór S. Guðmundsson

University of Iceland, Faculty of Social Work

halldorg@hi.is

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5917-5206

Ieva Reine

Uppsala University, Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences, Sweden and Rīga Stradiņš University, Statistics Unit, Latvia

ieva.reine@pubcare.uu.se

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1643-0983

Luule Sakkeus

Estonian Institute for Population Studies, Tallinn University

luule.sakkeus@tlu.ee

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3785-183X

Signe Tomsone

Rīga Stradiņš University, Department of Rehabilitation

Signe.Tomsone@rsu.lv

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7836-2672

Summary. Europe, notably in countries like Lithuania, is facing substantial demographic shifts due to aging, impacting various systems, including the labor market. In this context understanding retirement intentions is crucial. Quality of work is a key determinant of retirement intentions, yet other factors such as financial situation, health, or family pressures also play a role, and a comprehensive understanding of their interactions remains a research gap. Therefore, the aim of this study was to conduct a systematic literature review of research on the relationship between retirement intentions and quality of work, with a specific focus on potential control factors, moderators and mediators of this relationship. This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA). Articles were electronically retrieved from Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and EBSCO databases. Studies selected were full-text, peer-reviewed articles in English from 2003 to 2023, which used quantitative methodologies and focused on the relationship between retirement intentions and quality of work for workers aged 50+. The quality of the selected publications was assessed using the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies – AXIS tool. Of the initial 776 sources, after removing duplicates and irrelevant articles, 91 were fully screened, and 17 met the criteria for inclusion in the systematic review. This systematic literature review provided further insights into the relationship between retirement intentions and quality of work, highlighting the roles of moderators, mediators, and control factors in this relationship.

Keywords: intentions to retire, quality of work, systematic literature review, aging.

50 metų amžiaus ir vyresnių darbuotojų darbo kokybės ir ketinimų išeiti į pensiją ryšys: sisteminė literatūros apžvalga

Santrauka. Europoje stebimas visuomenės senėjimas, kuris veikia darbo rinką, tad darosi aktualu suprasti ketinimo išeiti į pensiją reiškinį. Tarp įvairių ketinimo išeiti į pensiją veiksnių išsiskiria darbo vietos kokybė, tačiau yra mažai informacijos apie galimas jos sąveikas su kitais veiksniais. Tikslas – atlikti sisteminę tyrimų, kuriuose analizuojamas ketinimo išeiti į pensiją ir darbo vietos kokybės ryšys, apžvalgą, skiriant dėmesio galimiems kontroliniams šio ryšio veiksniams, mediatoriams ir moderatoriams. Išanalizuota 17 straipsnių, atrinktų iš Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect ir EBSCO duomenų bazių. Apžvalga suteikė įžvalgų apie ketinimo išeiti į pensiją ir darbo vietos kokybės ryšį, išryškinant šio ryšio moderatorių, mediatorių ir kontrolinių veiksnių vaidmenį.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: ketinimas išeiti į pensiją; darbo vietos kokybė; sisteminė literatūros apžvalga; senėjimas.

Received: 2023-10-20. Accepted: 2023-12-21.

Copyright © 2023 Antanas Kairys, Raimonda Sadauskaitė, Olga Zamalijeva, Halldór S. Guðmundsson, Ieva Reine, Luule Sakeus, Signe Tomsone. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The aging phenomenon, driven by low birth rates and increased longevity, is significantly affecting the demographic structure across Europe, leading to a higher proportion of older people. In the EU, the population aged 65+ is set to rise from 26.3% (2019) to 43.5% (2070). Lithuania and Latvia are projected to have the highest decline in labor supply within the EU by 2070. The percentage of the older adults in Lithuania, which stood at 19.8% in 2019, is forecasted to nearly double, hitting 32.9% by 2070 (European Commission, 2021), which will put a huge strain not only on the labor market, but also on social security, pension, and other systems. Staying in the labor market is crucial for both society and individuals’ functioning, as the employment rate is one of the four components of Active aging (United Nations, 2019). At the same time, a simple increase in retirement age to counter rapid aging may not be a one-size-fits-all solution. It is obvious that the statutory retirement age cannot be increased indefinitely, and the real possibility to increase it varies a lot, depending on the region. According to the Eurostat (2021), healthy life years at birth in the Baltic states, being 60 at best, do not even reach the retirement age. For instance, a 65-year-old in Sweden can expect to live free from disability for another 14 years, whereas Lithuanian residents can expect it to be more than two times shorter (Eurostat, 2021). What is more, recent events in France, where pension reform and an increase in retirement age resulted in notable unrest (Drake, 2023), show that these type of changes are not welcomed by the public. Thus, the current situation calls for a new approach promoting retention of employees beyond retirement age without imposing legislation that forces them to do so. Understanding the factors influencing retirement intentions becomes essential in this context.

Work is not only important as a source of income, but also as a way of structuring and making sense of life and is an important part of a person’s identity (Lent & Brown, 2013). Moreover, the contemporary labor market facilitates active participation and presents numerous transitional pathways from employment to retirement, such as part-time work opportunities. However, Stynen et al. (2016) determined that roughly half of the older workforce intends to cease employment upon reaching the mandatory retirement age. Additionally, Van Solinge and Henkens (2014) found that 81% of older employees aim to retire even before the age of 65. So, overall, retirement is considered as a more favorable option than staying active in the labor market beyond retirement age. This suggests that the benefits an older worker expects from staying employed do not outweigh the anticipated effort. Consequently, the decision-making process involved needs further analysis.

In general, there is consensus that retirement is more complex than a sudden status change from worker to retiree. Thoughts, plans, expectations, and wishes are linked to action to retire or stay in the labor market past the retirement age (Topa et al., 2009). Two competing models of retirement have been proposed: the two-phase and the three-phase models (Nivalainen, 2022). The two-phase model conceptualizes stages of decisions (or intentions) and actions (Solem et al., 2016). Three-phase models distinguish between preferences (or thoughts), decisions (or intentions) and actions (Topa et al., 2009) or expectations, intentions, and actions (Prothero & Beach, 1984). However, many agree that preferences and decisions are related (Topa et al., 2009) and in various studies a wish to retire at a certain age is conceptualized both as a retirement preference (Örestig et al., 2013) and as a retirement intention (Carr et al., 2016). Therefore, the two-phase model, which does not distinguish between preferences and decisions, appears to be conceptually sound and more pertinent than the alternative. This also suggests that an individual’s purposeful desire and intention to retire (or to maintain employment beyond retirement age), regardless of the term used, are both equally relevant.

It is also quite evident that the decision making process resulting in the intention to retire is likely to be swayed by a variety of factors related to the immediate working environment. Research shows that undesirable job characteristics, such as stressful psychosocial work environment, high workload, and low control are associated with thoughts about early retirement (Carr et al., 2016). In contrast, an interesting work environment, appreciative colleagues, and development opportunities are linked to a lower intention to retire (Van Dam et al., 2009). Of course, work characteristics encompass many aspects, but in the broadest sense, quality of work is defined as “the set of work features which foster the well-being of the worker” (Green, 2006, p. 9). In empirical research, the terms “job quality” or “work quality” are used to describe various “working and employment conditions, such as the physical workload, the imposed work pressure, the incentive structure, and the perceived job stability” (Schnalzenberger et al., 2014, p. 142), and authors state that “no encompassing and operational definition of job quality is available” (Schnalzenberger et al., 2014, p. 142). Two models of quality of work have received significant attention: the demand-control model and the effort-reward imbalance model (Siegrist et al., 2007). In this review, we conceptualize quality of work as the work conditions that enhance or maintain employee well-being. This is described in terms of effort-reward imbalance, the demand-control ratio, or a multifaceted set of work attributes, such as physical workload, work pressure, and the incentive structure.

Over the past several decades, the quality of work emerged as one of the principal factors explaining retirement intentions, with several systematic reviews devoted to examining this relationship (e.g., Browne et al., 2019; Woźniak et al., 2022). What is more, the popularity of work quality in the context of retirement intentions is likely driven by existing theoretical models that comprehensively analyze specific work characteristics and their role in employee’s well-being. But in addition to quality of work, the literature has identified other factors contributing to retirement intentions. These factors include financial situation (Le Blanc et al., 2019), health status (Nivalainen, 2022), occupational class (Virtanen et al., 2017), perceived pressure from immediate family (Van Dam et al., 2009), among others. So, while the relationship between the quality of work and retirement intentions has been explored, there remains a gap in understanding how other factors influencing retirement intentions might interact with workplace quality. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic literature analysis, which has examined the relationship between retirement intentions and quality of work, has also focused on potential moderating, mediating or control factors of this relationship.

The aim of this study is to conduct a systematic literature review of research on the relationship between retirement intentions and quality of work, with a specific focus on potential control factors, mediators and moderators of this relationship.

Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021).

Study selection

Articles were searched electronically in the following databases: Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and EBSCO. The search was conducted using keywords combined with logical operators: (((retirement) OR (retire)) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND (((((work) OR (job) OR (employment)) AND (quality)) OR ((effort) AND (reward))) OR ((demand) AND (control)). Searches were conducted between the 7th and 15th of August 2023. For most databases, keywords were divided into two searches. However, for ScienceDirect, three searches were used due to a limitation in the number of logical operators. Specific combinations of keywords, additional limiters for each database, and the number of studies found in each database are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Search phrases for each database

|

Database |

Search phrase |

Additional |

Items found |

|

Scopus |

1. Searched 07/08/2023: TITLE-ABS-KEY (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((((work) OR (job) OR (employment)) AND (quality)) OR ((effort) AND (reward)))) AND PUBYEAR > 2002 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) 2. Searched 15/08/2023: TITLE-ABS-KEY (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((demand) AND (control))) AND PUBYEAR > 2002 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ar“)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) |

|

First search: 190 Second search: 40 |

|

Clarivate |

1. Searched 07/08/2023: TS=(((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((((work) OR (job) OR (employment)) AND (quality)) OR ((effort) AND (reward)))) 2. Searched 15/08/2023: TS=(((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((demand) AND (control))) |

Published 01/01/2003 – 08/08/2023 |

First search: 224 Second search: 67 |

|

Ebsco1 |

1. Searched 07/08/2023: TI (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((((work) OR (job) OR (employment)) AND (quality)) OR ((effort) AND (reward)))) OR AB (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((((work) OR (job) OR (employment)) AND (quality)) OR ((effort) AND (reward)))) OR SU (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((((work) OR (job) OR (employment)) AND (quality)) OR ((effort) AND (reward)))) 2. Searched 15/08/2023: TI (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((demand) AND (control))) OR AB (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((demand) AND (control))) OR SU (((retir*) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((demand) AND (control))) |

Published 01/01/2003 – 31/12/2023; Peer reviewed |

First search: 182 Second search: 30 |

|

Science |

1. Searched 07/08/2023: (((retirement) OR (retire)) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND (((work) OR (job) OR (employment)) AND (quality)) 2. Searched 07/08/2023: (((retirement) OR (retire)) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((effort) AND (reward)) 3. Searched 15/08/2023: (((retirement) OR (retire)) AND ((intention) OR (wish) OR (decision))) AND ((demand) AND (control)) |

Search in title, abstract or author-specified keywords; Published 2003–2023 |

First search: 20 Second search: 1 Third search: 3 |

Notes: 1 The search was performed in these EBSCO databases: Academic Search Ultimate, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Business Source Ultimate, Central & Eastern European Academic Source, Computers & Applied Sciences Complete, eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), eBook Open Access (OA) Collection (EBSCOhost), EconLit with Full Text, Education Source, ERIC, European Views of the Americas: 1493 to 1750, GreenFILE, Health Source – Consumer Edition, Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition, Historical Abstracts with Full Text, Humanities International Complete, Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, Literary Reference Center, Literary Reference eBook Collection, MasterFILE Premier, MasterFILE Reference eBook Collection, MEDLINE, Newspaper Source, OpenDissertations, Regional Business News, SocINDEX with Full Text, Teacher Reference Center; 2 due to the limits on the maximum number of Boolean operators, three searches were performed instead of two.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion of studies was based on the following criteria: full-text, peer-reviewed scientific articles in English, published between 2003 and 2023; quantitative methodologies conducted on a sample of working individuals aged 50 and older (studies involving a wider age range are included if separate analysis (or moderation) with 50+ subjects was done); the study analyzed the relationship between retirement intentions and the quality of work. Considering retirement intentions, we included studies that measured individual’s purposeful desire or intention to retire (or to remain in the labor market beyond retirement age), regardless of the term used. Studies that explore general attitudes towards retirement or retirement actions were not included. Regarding the quality of work, studies were selected for inclusion if they met any of the following criteria: authors explicitly stated that the quality of work was assessed; effort-reward imbalance was measured; both demand and control factors were evaluated; or multiple attributes of work, such as physical workload, work pressure, and the incentive structure, were examined. Articles that specifically focused on individuals with illnesses or disabilities were excluded, as these factors could distinctly affect retirement intentions. Literature reviews, meta-analyses, systematic literature reviews, and theoretical articles were not considered.

The agreement of two raters: Cohen’s Kappa = 0.73 for title and abstract screening, and Kappa = 0.74 for eligibility assessment based on full text.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by 2 researchers, with certain portions addressed individually. The information extracted from the selected articles includes: the aim of the study, countries where the study was conducted, dataset used, representativeness of the sample, whether it was a random sample, study design, timing of the study, sample size, gender distribution, age range, mean age, professions (or business areas) of respondents, the sectors of the companies represented, terms describing the intention to retire and quality of work, assessment methods for retirement intentions and quality of work, control variables (and significance), as well as moderating/mediating variables (and significance).

Quality assessment

The quality of the selected publications was assessed using the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies – AXIS tool (Downes et al., 2016). The tool is designed for quantitative studies and addresses the most critical quality aspects of research, such as study design, reporting quality, and risk of bias. Each study was given a score ranging from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating greater study quality. Quality assessment was performed by two reviewers. Their evaluations were in agreement for 65–100% of the items in each study. Overall, the agreement across all studies was 84.1%, Cohen’s Kappa = 0.62.

Results

Search results

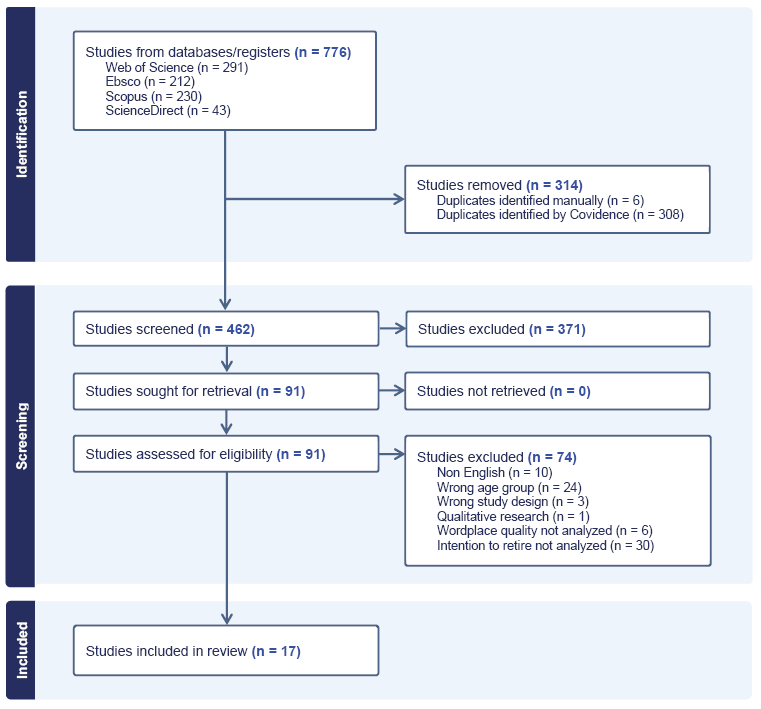

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart for studies included in the systematic review.

A total of 776 studies were identified. After removing 314 duplicates, 462 articles remained for screening. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, 371 studies were concidered irrelevant. Of the remaining 91 full-text articles that were screened, 74 were excluded for various reasons, the most common being that they did not analyze the intention to retire. Ultimately, 17 studies were included into the systematic review (see Figure 1).

Description of studies

Most of the studies included (see Table 2) were conducted in Europe. Only 2 of the 17 studies (11.8%) were conducted outside Europe (Australia). A significant proportion of studies (7 or 41.2%) covered more than one country. A significant number of studies used data from international or national databases and the most common (6 out of 17 studies, 35.3%) data source was the Survey on Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) database.

Most of the studies (58.8%) analyzed representative samples (see Table 2), and the same proportion of the studies analyzed the data collected using some type of random sampling. The vast majority (76.5%) of studies applied a cross-sectional study design. While most of the samples were large (with a min. sample size of 295 and a max. of 11790), only three studies had a sample size of less than 1,000. However, the populations within these samples were very diverse. Studies covering workers from different sectors and genders were prevalent, but there were also samples that were homogeneous in terms of occupation (e.g., Finnish postal workers) or gender (women only). The lower age limit for most of the studies was 50 years, but the upper age limit varied from 55 to 71, with most covering workers up to 65 years old.

Table 2. Description of the studies included

|

Reference |

Country in which the study conducted |

Data set used: |

Is sample represen-tative? |

Was random sampling applied? |

Study design |

Start and end date of data collection |

Population |

Total number of participants |

N(%) of females |

Min. - max. age |

Mean (SD) age |

Occupation or industry |

Sector |

|

Aidukaite & Blaziene, 2021 |

Multiple (Europe) |

Survey conducted by the authors |

Yes |

Yes |

Cross-sectional |

2019 |

Working older (50+) employees in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia |

2015 |

nd(61.2) |

50-nd |

nd |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Carr et al., 2016 |

United Kingdom |

ELSA db |

Yes |

Yes |

Longitudinal |

2004–2009 |

Working people aged 50+ living in private households in England |

3462 |

nd(51.2-52.9 (different numbers reported)) |

50-69 |

58-58.7(4.1) (different numbers reported) |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Dal Bianco et al., 2015 |

Multiple (Europe) |

SHARE db |

Yes |

Yes |

Longitudinal |

2004–2011 |

50-59 years old working people from 12 European countries |

10807 |

5248(48.6) |

50-59 |

nd |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Desmette & Gaillard, 2008 |

Belgium |

Survey conducted by the authors |

No |

No |

Cross-sectional |

nd |

French-speakers in Belgium working in private organizations |

352 |

nd(42) |

50-59 |

nd |

Different |

Private |

|

Grmanova & Bartek, 2022 |

Multiple (Europe) |

SHARE db |

Yes |

Yes |

Cross-sectional |

2019–2020 |

Unclear |

5342 |

2925(54.75) |

nd |

nd |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Henkens & Leenders, 2010 |

Netherlands |

Survey conducted by the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute |

No |

No |

Cross-sectional |

2001 |

Dutch older workers (50 +) and their spouses |

2892 |

2195(24) |

50-65 |

54.6(2.81) |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Hodgkin et al., 2017 |

Australia |

Survey conducted by the authors |

No |

No |

Cross-sectional |

nd |

Australian older healthcare workers |

295 |

nd(94.3) |

55-71 |

59(3) |

Healthcare personnel (nurses and allied health-care workers) |

Public |

|

Laires et al., 2019 |

Multiple (Europe) |

SHARE db |

Yes |

Yes |

Cross-sectional |

2015 |

Employed persons aged 50-65 in 14 European countries |

11790 |

6105(51.8) |

50-65 |

56.3(nd) |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Neupane et al., 2022 |

Finland |

National-level survey among Finnish postal services employees |

No |

No |

Cross-sectional |

2016 |

Finnish postal services employees aged≥50 years |

1965 |

781(40) |

50-nd |

56.3(3.43) |

Postal services employees |

Public |

|

Nilsson et al., 2011 |

Sweden |

Swedish National Institute of Working Life study db |

No |

No |

Cross-sectional |

2004 |

Respondents aged 55–64 years, employed in the healthcare sector in Sweden |

1792 |

nd(84) |

55-64 |

59 (median)(nd) |

Healthcare personnel |

Public |

|

Nivalainen, 2020 |

Finland |

QWLS db |

Yes |

Unclear |

Cross-sectional |

2008 - 2016 |

Working 50-62 years old Finish persons |

803 |

nd(57) |

50-62 |

57.4(2.5) |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Prakash et al., 2019 |

Finland |

2tS db |

No |

Unclear |

Cross-sectional |

2016 |

Finnish postal services employees aged ≥50 years |

1466 |

587(40) |

51-nd |

58.4(3.4) |

Postal service employees |

Public |

|

Schnalzenberger et al., 2014 |

Multiple (Europe) |

SHARE db |

Yes |

Yes |

Longitudinal |

2023 |

Employed Europeans aged 50-65 in 10 countries |

5639 (baseline) |

nd(48.2) |

50-65 |

55.3(3.73) |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Siegrist et al., 2007 |

Multiple (Europe) |

SHARE db |

Yes |

Yes |

Cross-sectional |

2004 |

Employed men and women aged >50 in 10 European countries |

6836 |

3316(48.5) |

50-65 |

nd |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Sousa-Ribeiro et al., 2023 |

Sweden |

SLOSH db |

Yes |

Yes |

Longitudinal |

2010 - 2016 |

Older workers (in Sweden) |

1510 (baseline) |

nd(59) |

50-55 (baseline) |

52.65(1.7) |

Different |

Private and public |

|

Taylor et al., 2016 |

Australia |

Online survey conducted by the authors |

No |

Yes |

Cross-sectional |

2013 - 2014 |

Australian women aged 50-70 and participating in two superannuation funds |

1043 |

1043(100) |

50-70 |

58.6(nd) |

Emergency services, higher education, research and public sectors |

Unclear |

|

Wahrendorf et al., 2013 |

Multiple (Europe) |

SHARE db |

Yes |

Yes |

Cross-sectional |

2004 - 2005 |

Employed Europeans aged 50+ in 11 countries |

6398 |

2840(44.4) |

50-64 |

nd |

Different |

Private and public |

Note: nd – no data; db – database.

2tS – “Towards a Two Speed Finland Survey (2tS)” (collected from the Finnish postal service employees); ELSA – The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing; SHARE – The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe; SLOSH – The Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health; lidA – The lidA Cohort Study (German Cohort Study on Work, Age, Health and Work Participation); QWLS – Statistics Finland’s 2008 cross-sectional, interview-based Quality of Working Life Survey.

Conceptualization and measurement of intentions to retire and quality of work

The terms used to describe intentions to retire did not differ much across studies (see Table 4). Most commonly, authors have used the terms “retirement intentions” or “intentions to retire,” but some studies have used the terms including “retirement preferences” (Carr et al., 2016), “desire to retire” (Grmanova & Bartek, 2022), “decision to retire” (Nilsson et al., 2011), or a combination of several terms (e.g., Dal Bianco et al. (2015) used both “intended early retirement” and “desire to retire as soon as possible”).

Most of the studies used single-item measurements to measure intentions to retire (see Table 3). For example, in SHARE project intention to retire is measured in six studies by asking: “Thinking about your present job, would you like to retire as early as you can from this job?” (SHARE, 2020). Three studies used two items to measure the intention to retire, for example, Nilsson et al. (2011) in their survey asked whether respondents wanted to work until 55–59, 60–64, 65, or ≥66 years of age, and whether participants believed they could work until those age brackets. Only one study used a multiple-item scale (Henkens & Leenders, 2010), comprising four questions about preferred retirement age, and intentions to retire or to continue working.

Where quality of work is concerned, there is a much wider range of concepts (see Table 3) among the studies that were selected for the analysis. The terms “working conditions,” “job characteristics,” “quality of work” and others were used by the authors. Some of the studies used theory-related constructs like effort-reward imbalance. While almost all studies used multiple-item tools to measure the quality of work, only one study (Grmanova & Bartek, 2022) used two items.

Links between the quality of work and intentions to retire

All but two studies found a significant link between quality of work and intentions to retire (see Table 3). No association between quality of work and intentions to retire was found in studies by Desmette and Gaillard (2008) and Hodgkin and colleagues (2017).

The general consensus suggests that the quality of work plays an important role in forming retirement intentions. However, when analyzing particular quality of work factors, evident discrepancies can be found after comparing the results of different studies (see Table 3). A prime example of such inconsistencies are the findings related to the physical working environment or physically demanding work. Five studies failed to find a link between physical aspects of quality of work and intentions to retire, but 4 studies managed to establish such a relationship. Similar inconsistencies were observed for autonomy, social support, financial rewards, and other factors. The effort-reward imbalance factors predicted intentions to retire in most studies, except in the study by Hodgkin et al. (2017).

Moderators, mediators, and control variables of the link between quality of work and intentions to retire

Only 3 studies (see Table 3) included mediators between the quality of work and intentions to retire: burnout may be considered a mediator in the relationship between quality of work and retirement intentions (Henkens & Leenders, 2010); job control and job support mediated the link between work-life satisfaction and intention to retire (Prakash et al., 2019); the associations between social position and retirement intentions might be partly mediated by the experience of work stress, however in this study, the mediational effect wasn’t fully tested (Wahrendorf et al., 2013).

Eight studies (47%; see Table 3) analyzed moderation effects or carried out a similar analysis (e.g., regression analysis in separate groups). The obtained results suggest that gender could be an important moderator of the association between quality of work and intentions to retire, as one study found a moderating effect (Neupane et al., 2022), two studies (Dal Bianco et al., 2015; Schnalzenberger et al., 2014) conducted analyses separately for gender, and only one study (Carr et al., 2016) did not find any moderating effect. Individual studies also found age (Carr et al., 2016) and type of contract (Taylor et al., 2016) to moderate the quality of work and intentions to retire relationship. Two studies (Hodgkin et al., 2017; Siegrist et al., 2007) tested interactions among various aspects of the quality of work, yet neither found any significant result. Given that many studies used cross-national samples, it can be hypothesized that the country of residence could be a potential moderator. This assumption aligns with the premise drawn in the study by Siegrist et al. (2007).

Of the studies analyzed, all except 2 included a set of control variables (see Table 3). The most common variables were demographic (e.g., age, gender), health (e.g., self-rated health), economic (e.g., income), and partner-related (e.g., marital status, partner employment status) variables. Employment history-related control variables (e.g., unemployment experience), employer-related control variables (e.g., recent layoffs), and psychological variables (e.g., well-being or depressiveness) were the least frequently examined. At least one study has found that predictors in each group are important in predicting intentions to retire and hence may be considered control variables.

Table 3. Results from included studies

|

Reference |

Terms to describe IR |

IR measurement |

Terms to describe WQ |

WQ measurement |

WQ aspects that predicted IR |

WQ aspects that didn’t predict IR |

All moderators of the IR and WQ link |

Significant moderators of the IR and WQ link |

All mediators of the IR and WQ link |

Significant mediators of the IR and WQ link |

All control variables of the IR and WQ link |

Significant control variables of the link IR and WQ |

|

Aidukaite & Blaziene, 2021 |

Decision (not) to stay longer in the labor market, intentions to stop/continue working after reaching the retirement age |

Unclear |

Working conditions |

Unclear |

Physical working conditions, work intensity, working time arrangements, social environment, job-related prospects**** |

Unclear |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Carr et al., 2016 |

Retirement preferences, preferred number of years until retirement |

Single item |

Working conditions, job characteristics (physical job demands, psychosocial demands and decision authority) |

Multiple items |

Psychosocial demands, decision authority, recognition** |

Physical demands, social support |

Interactions between job demands and job resources, sex, age |

Age |

- |

- |

DC, EC, HC, SC |

Unclear |

|

Dal Bianco et al., 2015 |

Intended early retirement, desire to retire as soon as possible |

Single item |

Quality of work, work quality |

Multiple items |

Physically demanding work**, stress, freedom**, possibility of skills development, support, recognition** |

Adequate salary, career prospects, job security |

Gender*** |

Unclear, models were specified for males and females separately |

- |

- |

CC, DC, EC, SC |

Unclear |

|

Desmette & Gaillard, 2008 |

Early retirement intentions, intentions to retire early |

Two items |

Job characteristics (physical strain of the job, autonomy at work) |

Multiple items |

None |

Physical job strain, autonomy, work-to-private conflict |

- |

- |

- |

- |

DC, EC, HC, RC, SC |

EC, HC, RC |

|

Grmanova & Bartek, 2022 |

Desire to retire early |

Single item |

Job physical demands, job satisfaction |

Two items |

Job physical demands, job satisfaction**** |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Henkens & Leenders, 2010 |

Early retirement intentions, retirement intentions |

Multiple items |

Job characteristics (workload, physical demands, challenge, opportunities of growth, autonomy, social support) |

Multiple items |

Workload**, challenge, opportunities of growth |

Physical demanding job, authonomy, social suport |

- |

- |

Burnout may be a mediator of the work quality and retirement intentions relationship |

Burnout may be a mediator of the work quality and retirement intentions relationship |

DC, PSC, SC, WC |

DC, PSC, SC, WC |

|

Hodgkin et al., 2017 |

Retirement intentions |

Single item |

Effort-reward imbalance |

Multiple items |

None |

Effort, reward |

Interaction between effort, reward and overcommitment was tested |

None |

- |

- |

DC |

DC |

|

Laires et al., 2019 |

Intention of retirement |

Single item |

Quality of work |

Multiple items |

Effort-reward imbalance |

- |

Working conditions, integration policies (the link between multimorbidity and retirement intentions were moderated) |

None |

- |

- |

CC, DC, EC, HC |

DC, HC |

|

Neupane et al., 2022 |

Intention to retire |

Single item |

Equality at work, quality of work community |

Multiple items |

Equality at work, supportive work environment**, flexibility at work** |

- |

Gender |

Gender |

- |

- |

DC, HC, PC, WC |

HC |

|

Nilsson et al., 2011 |

Decision to extend working life or retire |

Two items |

Work environment |

Multiple items |

Physical work environment**, mental work environment**, work pace and working time**, managerial and organizational attitude towards older workers**; competence and possibility for skills development**; motivation and work satisfaction**. |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

EC, HC, SC |

EC, HC, SC |

|

Nivalainen, 2020 |

Retirement intentions |

Single item |

Work characteristics (job autonomy, job demands) |

Multiple items |

Employer’s support for continued employment, job autonomy |

Flexibility in scheduling, physically demanding job, mentally demanding job, time pressure |

- |

- |

- |

- |

DC, EC, EHC, EMC, RC, SC, WC |

DC, EC, EHC, EMC, RC, WC |

|

Prakash et al., 2019 |

Intention to retire |

Two items |

Working conditions (job support and job control) |

Multiple items |

Job control, job support |

Unclear* |

- |

- |

Job control, job support (the link between worklife satisfaction and intention to retire was mediated) |

Job control, job support (the link between worklife satisfaction and intention to retire was mediated) |

DC, HC, PC, WC |

Unclear |

|

Schnalzenberger et al., 2014 |

Intention to retire |

Single item |

Job quality |

Multiple items |

Job satisfaction, effort-reward imbalance**, support**, recognition**, adequate earnings**, poor prospects** |

Physically demanding job, time pressure, job security |

Gender*** |

Unclear |

- |

- |

CC, DC, EC, HC, PC, SC, WC |

Unclear |

|

Siegrist et al., 2007 |

Intended retirement, intended early retirement |

Single item |

Quality of work |

Multiple items |

Effort-reward imbalance, control |

- |

The interaction between effort-reward imbalance and control was analyzed. Country*** |

None |

- |

- |

DC, EC, HC, PSC |

DC, HC, PSC |

|

Sousa-Ribeiro et al., 2023 |

Preferred retirement age |

Single item |

Effort-reward imbalance |

Multiple items |

Effort-reward imbalance |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

DC, HC, PC, SC, WC |

DC, HC, PC, WC |

|

Taylor et al., 2016 |

Retirement intentions |

Single item |

Job satisfaction |

Multiple items |

Satisfaction with: job security, the work itself**, flexibility to balance commitments**; overall satisfaction** |

Satisfaction with: total pay, working hours |

Employment status |

Employment status |

- |

- |

EC, HC, PC, RC, SC |

EC, PC, RC, SC |

|

Wahrendorf et al., 2013 |

Retirement intentions |

Single item |

Quality of work, work stress |

Multiple items |

Effort-reward imbalance, control |

- |

- |

- |

Associations between social position and retirement intentions might be partly mediated by the experience of work stress.*** |

Associations between social position and retirement intentions might be partly mediated by the experience of work stress.*** |

CC, DC, HC, PC, WC |

CC, DC, HC, PC, WC |

Notes: IR – intentions to retire; WQ – quality of work.

Control variables: CC – country-level (like country, life expectancy); DC – demographic (like age or gender); EC – economic (like income); EHC - employment history-related (like unemployment experience); EMC – employer-related (like recent layoffs); HC – health-related (like self-rated health); PC – profession or occupation-related (like occupational status); PSC – psychological (like well-being or depressiveness); RC – retirement-related (like attitudes about retirement or being in partial retirement); SC – spouse or partner-related (like marital status, employment status of partner); WC – work-related (like working hours or flexibility at work).

* the use of analytical methods that do not allow the statistical significance of specific predictors to be assessed; ** several models tested, not significant in some models; *** the moderation or mediation effect not tested, however, some other analyses indicated a moderating effect; **** only univariate analysis performed.

Quality assessment

The quality assessment (see Table 4) identified several weaknesses in the studies. It should be noted that many AXIS criteria were met by all or almost all studies, but the justification of sample size and information on nonresponders undermined the quality of many studies. Most studies did not specify the rationale for the sample sizes chosen or determine whether they were sufficient for the analysis outlined. However, if we consider that the sample sizes in most analyzed studies were notably large, it can be concluded that the absence of sample size justification, in this case, might not be a cause for concern. Only a few studies provided any information on nonrespondents, making it difficult to assess whether the samples were biased.

Table 4. Assessment of the study quality

|

Reference |

Aidukaite & Blaziene, 2021 |

Carr et al., 2016 |

Dal Bianco et al., 2015 |

Desmette & Gaillard, 2008 |

Grmanova & Bartek, 2022 |

Henkens & Leenders, 2010 |

Hodgkin et al., 2017 |

Laires et al., 2019 |

Neupane et al., 2022 |

Nilsson et al., 2011 |

Nivalainen, 2020 |

Prakash et al., 2019 |

Schnalzenberger et al., 2014 |

Siegrist et al., 2007 |

Sousa-Ribeiro et al., 2023 |

Taylor et al., 2016 |

Wahrendorf et al., 2013 |

|

1 Were the aims/objectives of the study clear? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

2 Was the study design appropriate for the stated aim(s)? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

3 Was the sample size justified? |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

|

4 Was the target/reference population clearly defined? (Is it clear who the research was about?) |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

5 Was the sample frame taken from an appropriate population base so that it closely represented the target/reference population under investigation? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

|

6 Was the selection process likely to select subjects/participants that were representative of the target/reference population under investigation? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

|

7 Were measures undertaken to address and categorise non-responders? |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

|

8 Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured appropriate to the aims of the study? |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

9. Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured correctly using instruments/measurements that had been trialled, piloted or published previously? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

10 Is it clear what was used to determined statistical significance and/or precision estimates? (e.g. p-values, confidence intervals) |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

|

11 Were the methods (including statistical methods) sufficiently described to enable them to be repeated? |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

12 Were the basic data adequately described? |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

|

13 Does the response rate raise concerns about non-response bias? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

|

14 If appropriate, was information about nonresponders described? |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

N |

Y |

|

15 Were the results internally consistent? |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

16 Were the results presented for all the analyses described in the methods? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

17 Were the authors’ discussions and conclusions justified by the results? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

18 Were the limitations of the study discussed? |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

19 Were there any funding sources or conflicts of interest that may affect the authors’ interpretation of the results? |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

|

20 Was ethical approval or consent of participants attained? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

Note: Y – yes; N – No

Discussion

In this systematic analysis, 17 articles published during the period from 2007 to 2023 and analyzing the relationship between the quality of work and intentions to retire among workers aged 50+ were included. Moving beyond the analysis conducted and conclusions drawn by prior studies (Browne et al., 2019; Woźniak et al., 2022), this systematic review adds a new layer of information on moderators, mediators and control factors that play a role in understanding the mechanisms underlying the relationship between the quality of work and intentions to retire.

When discussing the quality of the studies, it can be noted that most studies included in the review analyzed data from large samples, and a compelling number of them used data from representative and randomly selected samples. But there is a clear lack of studies conducted in non-European contexts. The prevalence of research in Europe is not surprising given that Europe is one of the regions experiencing rapid demographic aging (European Commission, 2021). Nevertheless, ageing is a worldwide megatrend and noticeable country differences, including diverse pension systems, employers’ policies on the quality of work, the level of ageism and other cultural or policy factors, make it impossible to generalize the patterns found in Europe more widely. The importance of longitudinal studies in this area has been indicated by previous systematic reviews (Browne et al., 2019), but once again it became evident in the current review that cross-sectional studies remain to be the most prevalent and research is still far from causal inferences. What is more, just a few studies included people over 65. This age restriction is disappointing, as it is not uncommon for people over 65 to remain active in the labor market, for example, as many as 46.3% of Icelandic men aged 65 and over are still employed (NASEM, 2022). Thus, there persists a need to figure out how retirement decisions are made by those who has already reached retirement age. Finally, as only a few studies provide any information on nonrespondents, there is risk of biased samples and this limits the generalizability of findings even more.

This systematic analysis suggests that quality of work is in fact linked to intentions to retire, as only two of the 17 studies did not confirm this relationship. This broadly replicates the findings of previous systematic analyses (Browne et al., 2019; Woźniak et al., 2022) and theoretical work (Feldman, 1994). While the general proposition that quality of work is related to intentions to retire can be considered to be well supported, the same cannot be said about specific quality of work aspects. There is no clear answer if physical aspects of work quality, autonomy, social support, financial rewards and other variables can be considered as determinants of intentions to retire. These findings may be partly related to the results of the review conducted by Brown and colleagues (2019). In their review they found that different aspects of quality of work have different value in predicting intentions to retire: work resources (negatively) rather than demands are more strongly associated with intentions to retire, while the amount of research that analyzed the role of effort-reward imbalance was deemed to be insufficient by the Brown at al. (2019) review to draw conclusions. This implies that further research on different aspects of quality of work is needed in order to have an evidence-based understanding which work characteristics are the most important for retirement intentions.

The systematic review identified that the relationship between quality of work and intentions to retire may indeed be mediated or moderated by other factors. Unfortunately, there are too few studies to make broader generalizations. A study by Henkens and Leenders (2010), showing burnout to be a mediator of the quality of work and retirement intentions relationship, suggests that the analysis of potential mediators may lead to a better understanding of the psychological mechanisms underlying the association between quality of work and intentions to retire. The analysis of moderators showed that most (but not enough) evidence points to gender as a moderator. Other potential moderators (age, country, type of employment contract) have only been analyzed in single studies, so there is a lack of evidence on their moderating role. A comprehensive analysis of moderators can help explain the reasons why some studies find a relationship and others do not.

The analysis of the control variables revealed a wide variety of factors that are controlled for when studying predictors of intentions to retire. While most studies included demographic, health or economic variables, there is a lack of information on employment history, employer-related and psychological factors. The wide range of control variables included in the studies should not be surprising given the complex interplay of individual, interpersonal, organizational and cultural variables associated with intentions to retire. The model by Woźniak and colleagues (2022) is an excellent representation of the complex interaction between the social environment at the workplace, job characteristics, employee- and employer-related factors, and cultural context, all of which influence the work ability and eventually affects the intentions to retire. The Woźniak et al. (2022) model and the findings of our review suggest that simple inclusion of control variables in a multiple regression or similar models is not an accurate representation of the true interaction between factors and that we should be looking for moderating and mediating effects. Moreover, the inclusion of too many control variables or unreliably measured control variables can lead to undesirable statistical artefacts (Briere, 1992). Excess of control variables may artificially suppress the effect of the independent variable of interest. In addition, a large number of covariates increases the likelihood of multicollinearity, which can in turn lead to very strange and unjustified effects. Variable measurement error can also lead to changes in the strength or even direction of the relationship (Briere, 1992). Thus, researchers should be very careful in selecting necessary, theoretically sound and reliably measured control variables and be cautious when considering whether they are control variables or whether, based on theoretical assumptions, they should be included as mediators or moderators. On the other hand, more research is needed to show which intention-to-refute predictors are necessary in analyses.

This systematic review highlights the importance of mediating, moderating and control variables, which have not been analysed in previous systematic reviews (Browne et al., 2019; Woźniak et al., 2022). On the other hand, this review has some limitations. Firstly, a broader search is possible, covering a larger number of databases and an extended period of publication. The inclusion of gray literature (e.g., unpublished papers, theses, policy papers) may broaden the variety of studies and help alleviate publication bias, enhance the comprehensiveness and timeliness of the review, promote a more well-rounded portrayal of the existing evidence (Paez, 2017). The fact that only studies published in English were included is also a limitation. The inclusion of studies published in other languages would allow for a broader range of countries to be represented and hence provide better insight into the ways the quality of work and intentions to retire are related in non-European cultures and pension systems. The systematic review is also limited because it focuses only on healthy populations. Finally, people with chronic diseases or disabilities may face specific workplace challenges or retirement decisions, thus a systematic review of studies focusing specifically on these populations would be worthwhile.

Acknowledgement

The research was conducted as a part of the project “Sustainable working-life for ageing populations in the Nordic-Baltic region” (Project No. 139986 financed by NordForsk).

References

Aidukaite, J., & Blaziene, I. (2022). Longer working lives – what do they mean in practice – a case of the Baltic countries. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 42(5/6), 526–542. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-02-2021-0049

Briere, J. (1992). Methodological issues in the study of sexual abuse effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(2), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.60.2.196

Browne, P., Carr, E., Fleischmann, M., Xue, B., & Stansfeld, S. A. (2019). The relationship between workplace psychosocial environment and retirement intentions and actual retirement: A systematic review. European Journal of Ageing, 16(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0473-4

Carr, E., Hagger-Johnson, G., Head, J., Shelton, N., Stafford, M., Stansfeld, S., & Zaninotto, P. (2016). Working conditions as predictors of retirement intentions and exit from paid employment: A 10-year follow-up of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. European Journal of Ageing, 13(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-015-0357-9

Dal Bianco, C., Trevisan, E., & Weber, G. (2015). “I want to break free”. The role of working conditions on retirement expectations and decisions. European Journal of Ageing, 12(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-014-0326-8

Desmette, D., & Gaillard, M. (2008). When a “worker” becomes an “older worker”: The effects of age‐related social identity on attitudes towards retirement and work. Career Development International, 13(2), 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810860567

Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C., & Dean, R. S. (2016). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

Drake, H. (2023). Reform or Revolution? French Politics at the Crossroads. Political Insight, 14(1), 36–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/20419058231167271

European Commission (2021). The 2021 ageing report: Economic & budgetary projections for the EU member states (2019-2070). Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2765/84455

Eurostat (2021). Healthy life years statistics. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Healthy_life_years_statistics

Feldman, D. C. (1994). The decision to retire early: A review and conceptualization. Academy of management review, 19(2), 285-311. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1994.9410210751

Green, F. (2007). Demanding work: The paradox of job quality in the affluent economy. Princeton University Press.

Grmanova, E., & Bartek, J. (2022). Factors affecting the working life lenght of older people in the European Union. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 10(1), 64–79. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2022.10.1(3)

Henkens, K., & Leenders, M. (2010). Burnout and older workers’ intentions to retire. International Journal of Manpower, 31(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437721011050594

Hodgkin, S., Paul, W., & Warburton, J. (2017). Effort-reward imbalance and intention to retire early in Australian healthcare workers. Australasian Journal of Organisational Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.1017/orp.2017.2

Laires, P. A., Serrano-Alarcón, M., Canhão, H., & Perelman, J. (2020). Multimorbidity and intention to retire: A cross-sectional study on 14 European countries. International Journal of Public Health, 65(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01322-0

Le Blanc, P. M., Peeters, M. C. W., Van Der Heijden, B. I. J. M., & Van Zyl, L. E. (2019). To leave or not to leave? A multi-sample study on individual, job-related, and organizational antecedents of employability and retirement intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02057

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Understanding and facilitating career development in the 21st century. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed, pp. 1–26). Wiley.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). 2022. Understanding the Aging Workforce: Defining a Research Agenda. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26173

Neupane, S., Kyrönlahti, S., Kosonen, H., Prakash, K. C., Siukola, A., Lumme-Sandt, K., Nikander, P., & Nygård, C.-H. (2022). Quality of work community and workers’ intention to retire. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95(5), 1157–1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01826-4

Nilsson, K., Hydbom, A. R., & Rylander, L. (2011). Factors influencing the decision to extend working life or retire. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 37(6), 473–480. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3181

Nivalainen, S. (2022). From plans to action? Retirement thoughts, intentions and actual retirement: An eight-year follow-up in Finland. Ageing and Society, 42(1), 112–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000756

Örestig, J., Strandh, M., & Stattin, M. (2013). A wish come true? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between retirement preferences and the timing of retirement. Journal of Population Ageing, 6(1–2), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-012-9075-7

Paez, A. (2017). Gray literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 10(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12266

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Prakash, K. C., Jodi Oakman, Nygård, C.-H., Siukola, A., Lumme-Sandt, K., Nikander, P., & Neupane, S. (2019). Intention to retire in employees over 50 Years. What is the role of work ability and work life satisfaction? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142500

Prothero, J., & Beach, L. R. (1984). Retirement Decisions: Expectation, Intention, and Action. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 14(2), 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1984.tb02228.x

Schnalzenberger, M., Schneeweis, N., Winter-Ebmer, R., & Zweimüller, M. (2014). Job quality and employment of older people in Europe. Labour, 28(2), 141–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/labr.12028

SHARE (2020). Questionnaire Wave 8. https://share-eric.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Questionnaires/Q-Wave_8/paperverstion_en_GB_8_2_5b.pdf

Siegrist, J., Wahrendorf, M., Von Dem Knesebeck, O., Jurges, H., & Borsch-Supan, A. (2007). Quality of work, well-being, and intended early retirement of older employees: Baseline results from the SHARE Study. The European Journal of Public Health, 17(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckl084

Solem, P. E., Syse, A., Furunes, T., Mykletun, R. J., De Lange, A., Schaufeli, W., & Ilmarinen, J. (2016). To leave or not to leave: Retirement intentions and retirement behaviour. Ageing and Society, 36(2), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14001135

Sousa-Ribeiro, M., Stengård, J., Leineweber, C., & Bernhard-Oettel, C. (2023). Are trajectories of preferred retirement ages associated with health, work ability and effort–reward imbalance at work? Findings from a 6-year Swedish longitudinal study. Work, Aging and Retirement, waad006. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waad006

Stynen, D., Jansen, N. W. H., Slangen, J. J. M., & Kant, Ij. (2016). Impact of development and accommodation practices on older workers’ job characteristics, prolonged fatigue, work engagement, and retirement intentions over time. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 58(11), 1055–1065. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000853

Taylor, P., Earl, C., & McLoughlin, C. (2016). Contractual arrangements and the retirement intentions of women in Australia. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 19(3), 175–195. https://ftprepec.drivehq.com/ozl/journl/downloads/AJLE193taylor.pdf

Topa, G., Moriano, J. A., Depolo, M., Alcover, C.-M., & Morales, J. F. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of retirement planning and decision-making: A meta-analysis and model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(1), 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.03.002

United Nations (2019). 2018 Active Ageing Index. Analytical Report. United Nations. https://unece.org/DAM/pau/age/Active_Ageing_Index/ECE-WG-33.pdf

Van Dam, K., Van Der Vorst, J. D. M., & Van Der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2009). Employees’ Intentions to Retire Early: A Case of Planned Behavior and Anticipated Work Conditions. Journal of Career Development, 35(3), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845308327274

Van Solinge, H., & Henkens, K. (2014). Work-related factors as predictors in the retirement decision-making process of older workers in the Netherlands. Ageing and Society, 34(9), 1551–1574. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000330

Virtanen, M., Oksanen, T., Pentti, J., Ervasti, J., Head, J., Stenholm, S., Vahtera, J., & Kivimäki, M. (2017). Occupational class and working beyond the retirement age: A cohort study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(5), 426–435. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3645

Wahrendorf, M., Dragano, N., & Siegrist, J. (2013). Social position, work stress, and retirement intentions: A study with older employees from 11 European countries. European Sociological Review, 29(4), 792–802. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs058

Woźniak, B., Brzyska, M., Piłat, A., & Tobiasz–Adamczyk, B. (2022). Factors affecting work ability and influencing early retirement decisions of older employees: An attempt to integrate the existing approaches. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 35(5), 509–526. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01354