Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika ISSN 1648-2425 eISSN 2345-0266

2026, vol. 32, pp. 59–75 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2026.32.4

“What Now?” vs. “Now It’s My Turn!” – Reflecting on Motherhood after the Children Have Left

Marie-Kristin Doebler

ISF Munich - Institute for Social Science Research, Germany

E-mail: Marie-Kristin.Doebler@isf-muenchen.de

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9190-6734

https://ror.org/0120amd78

-----------------------------------

This paper is based on empirical material gathered in the project, “Gender differences in key transition phases in family life: Ethnographies of Becoming a Parent, Separation, and the Empty Nest“. The project was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under project number 315174848.

-----------------------------------

Abstract. Interested in being a mother and mothering across time, I compare two types of data: (a) interviews with middle-class mothers of grown-ups reflecting upon their prior (maternal) life in Germany, and (b) self-help books addressing parents in this life-phase, called the ‘empty nest’. My analysis reveals differing understandings and constructions of motherhood. The books homogenise being a mother and naturalise what a mother is, does and feels. Accordingly, women complete themselves and find self-fulfilment primarily as mothers, and thus, they struggle when children have moved out as this provides problems for mothering or even signifies the end of motherhood. Contrary to this, the interviews display much greater diversity: despite retrospectively construing images of comprehensive motherly care, gender differentiated life-courses and intensive mothering prior to children’s move out, the interviewees narratively present varying ways of being a mother and a dynamic balancing of motherhood with other sources of identity. Thus, their self-descriptions clash with the self-help depiction of static motherhood in books and uniform experiences of the nest emptiness. Rather than discussing a void and asking, “What now?”, the interviewees make sense of the lived temporality of motherhood and pragmatically deal with the changing needs for mothering. None of them suffers when they launch their children into independent life as they develop coping strategies in former life-course stages, continue to mother after the children have left home, and claim “Now it’s my turn!”

Keywords: Empty nest, gendered parenthood, life-course, motherhood, social constructionism.

Received: 2025 02 25. Accepted: 2025 07 04.

Copyright © 2025 Marie-Kristin Doebler. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

People grow up with ideas about gendered parenthood and parenting from infancy onwards (Rose & Schmied-Knittel, 2011). Expectant and new parents are exposed to these ideas in a particularly explicit and prescriptive manner, e.g., by attending prenatal and childbirth classes which can be considered the norm for first-time parents in Germany (Müller & Zillien, 2016). Many also seek advice in parenting guides. These courses and books tend to link biological processes of being pregnant, giving birth and breast-feeding to a female primary carer role (Grant, 1998; Hulbert, 2003). Combined with other socio-cultural factors (e.g., parental ideologies emphasising intensive care, the moralisation of maternal doings; cf. Ennis (2014); Hays (1996)) and institutional conditions (e.g., tax regimes, childcare infrastructure, configurations of the labour market), this (re)produces a normative image of women as primary caregivers (Lück & Ruckdeschel, 2018), and renders the act of people becoming parents a highly gendered process. Taken together, this contributes to the persistent framing of child-rearing as a primarily maternal task and paves the way for subsequent life courses. Hence, it does not come as a surprise that research on the effects of children’s departure, i.e., the so-called ‘empty nest’1, deals primarily with mothers, too.

While a few consumer-oriented studies portray this transition as an opportunity, by pointing out that parents (re)gain freedoms and experience economic betterment (Hogg et al., 2004; Lefton, 1996), the majority of the slowly growing body of empty nest research treats the departure of children as a predominantly negative turning point (Mitchell, 2019; Randhawa & Kaur, 2021; Raup & Myers, 1989). Respective views began to circulate with primarily psychological research focusing on (especially white, middle-class, married) women who concentrated their entire lives on the nuclear family with an identity defined by be(com)ing the wife and mother of someone. Despite considerable changes in the last decades regarding family formation and composition, e.g., an increasing maternal age at first birth, a decline in the number of children per woman, as well as an increasing labour market participation of (married) women (with children), this research strand still hypothesises that women entering the empty nest ask themselves: “What now?” Probably due to the samples and questionnaires used, as well as by taking a snapshot view, they indeed find that mothers suffer when their children depart (Mitchell & Lovegreen, 2009).

Even when there is research pointing out that the process of children’s detaching is less homogenous and less exclusive (Hartanto et al., 2024), the primarily quantitative body of psychological research on the empty nest renders it a maternal crisis in midlife. In doing so, they tend to omit socio-cultural, infrastructural and institutional factors (e.g., legal and practical entitlements to parental leave, childcare and parenting ideals), and tie women’s identity, self-worth or value to their performance as mothers.

Studies rooted in social psychology, and rarely in sociology, draw more nuanced pictures, by acknowledging (a) that other family members might be affected too, and (b) by highlighting both negative and positive effects. These include re-intensified romantic relationships and improved parent-child relationships which are relieved of everyday conflicts, as well as the recognition of the broader life context in which this transition occurs, e.g., aging, the onset of caregiving for older relatives and the loss of one’s own parents (Newman & Grauerholz, 2002).

Still, there is a lack of research engaging with mothers’ self-understanding and dynamic ways of mothering. These elements are crucial in understanding how the transition to the empty nest is perceived and experienced. Consequently, I adopt a qualitative sociological perspective, rooted in social constructivism (Berger & Luckmann, 1966) and practice theory (Reckwitz, 2002). Accordingly, I engage with sociocultural ideas of motherhood documented in self-help books as well as mothers’ presentation of being a mother self-reflexively narrated in interviews. My aim is to depict the situatedness of ‘mothering’ and the related evaluative interpretations, and to show that there is dynamism and heterogeneity in doing ‘being a mother’. My research serves as an explorative case study of middle-class motherhood in Germany. This focus frames the scope of my insights, as discussed at the end of this paper. Here, I solely contextualize the empirical analysis by sketching some aspects which may make this national context in some respects distinctive:

• A historically rooted scepticism toward institutional childcare (in what has been known as West Germany), tied to experiences of state overreach during National Socialism, resulting in a persistent preference for private caregiving expressed primarily in moralizing terms, while framing (working) mothers who send their children to kindergarten as bad moms (‘Rabenmütter’);

• A tax system that renders higher earnings by the second parent financially unattractive, and thereby promotes a modernized bourgeois family;

• High costs and limited availability of high-quality institutional childcare, especially for children under three, and for afterschool care, thereby making it difficult to combine employment and caregiving responsibilities.

Taken together, these factors contribute to prolonged periods of non- or part-time employment with very few hours among mothers, as well as gendered parenthood (Döbler et al., 2025).

In the following, I first outline the methods and the empirical material (Section 2). I then present the findings derived from the analysis of self-help books addressing parents in the empty nest transition (Section 3) and interviews with mothers in this phase (Section 4). Next, I compare, and contrast the interviewees lived lives with (normative) idea(l)s documented in the analysed self-help literature (Section 5). The paper concludes with a brief reflection on the study, including an outlook on future research (Section 6).

2. Methods and Materials

The empirical material was collated as part of a research project funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), with a focus on the division of labour in heterosexual couples during family transitions in Germany: birth, separation, and children’s move out. In this paper, I concentrate on the latter. I analyse and contrast self-help books and narrative-biographical (couple) interviews that address children’s departure.

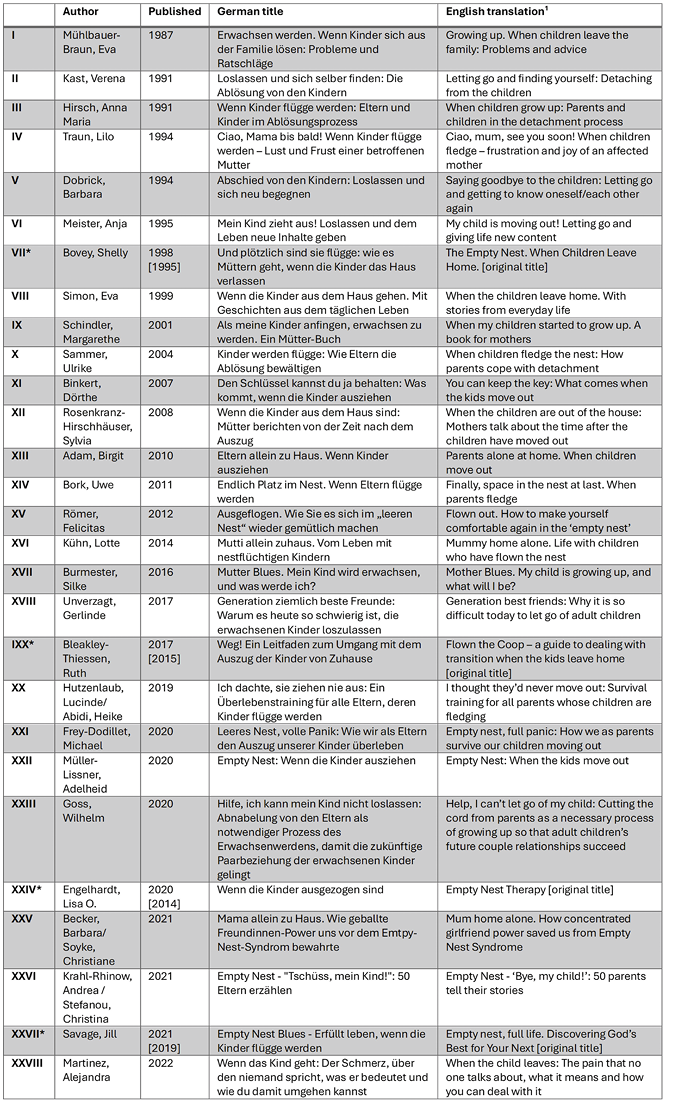

Table 1. Self-help book overview; 1 Unless stated otherwise, own translations;

* Originally published in English.

Typical for the genre, the books promise advice or guidance, function as self-help manuals or companions, and condense values, norms and (moralised) knowledge considered valid and available at a certain point in time (Zeller, 2018). Thus, I view the self-help books as sociocultural artefacts and material documents of the contexts in which the interviewed mothers live and practice motherhood. The interviews capture the retrospective, reflexive self-positioning of interviewees based on lived experiences within a respective sociocultural background.

We complied a complete sample of the twenty-eight empty nest self-help books published in German between 1987 and 2022. The growing publication activities during the last few years (cf. Table 1) might indicate an increased (societal) interest in the empty nest, a greater demand for advice from parents or the somehow ‘logical’ (market) consequence: guides aimed at soon-to-be empty nesters have been published since the first generations of parents who consumed prenatal and parental advice, e.g., in the form of books, and practised intensive parenting styles began to transition into this phase of life (Döbler et al., 2025; Grant, 1998; Hulbert, 2003).

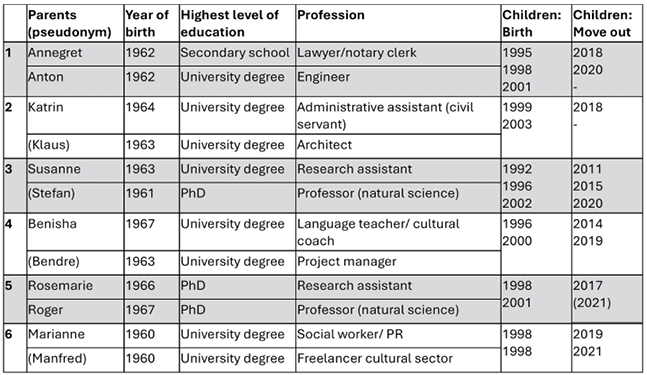

Authors of the empty nest self-help books describe their readership, amongst others, through self-identification: “we” are formally highly educated, economically well-off, “our” children completed their schooling with their A-levels and left the parental home for study or, “symptomatic of this generation of middle-class children” (XVII, 14), to spend a longer period abroad. Aiming to compare self-help books and interviews, we oriented our sampling accordingly at a modern self-reflexive middle-class striving for postmaterialist values such as autonomy and equality (Reckwitz, 2020). Additional selection criteria were defined by the overall interest of this research (cf. above) and this paper’s focus. Thus, the interviewees are all mothers of a similar age who, with one exception, are still in the same heterosexual relationships in which their now grown-up children were born (cf. Table 2). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020/2021, we conducted the interviews online.

All interviews, except for the one with Benisha, were conducted in German. We focused on the German editions of the guides (even if four of them were first published in English). Consequently, all subsequent quotes are my own translations, intersubjectively validated and cross-checked by using software (DeepL). They aim was to be as literal as possible while preserving the meaning.

We digitised the self-help books, transcribed, and anonymised interviews. The whole material was analysed by means of qualitative content analysis for gaining an overview of the themes (Kuckartz & Rädiker, 2024). Passages, identified as ‘rich’, were subjected to interpretative sequence analysis by following the documentary method (Bohnsack, 2001) and discourse analysis (Keller, 2005).

Table 2. Interview sample – a descriptive overview; names in brackets = not part of the interview

3. The Self-Help Books: Depictions of Mothers in the Empty Nest

The self-help books present the children’s move out as a surprise for the parents. There is supposed to be “full panic” as “we as parents” wonder how “to survive” (XXI: title page) or call for “Help!” as one has difficulties with detaching from or letting go of the children (e.g., XXIII; II; V). According to the authors, society expects “us to deal with” the respective change and loss, “but nobody tells us how to do that” (XV, 11; XXVIII). They posit their own experience of an alleged absence of knowledge regarding the transition, the paucity of guidance for navigating the empty nest, and the lack of community support – when needing all of it – as key motivations for engaging with the topic. Thus, the plot is usually like this: the authors explain in the epilogue or introduction that they as parents, i.e., in 25 out of the 28 cases as mothers, struggled and mourned when their children had left home, but eventually discovered coping strategies which are presented throughout the rest of the book.

To substantiate their advice, the authors refer to their own expertise, primarily based on experiences with launching children (e.g., XIV; XVII), and occasionally supported by a professional background in education or psychology (e.g., II; XX). Some guides additionally draw on scientific studies (e.g., XV; XXII), though, more often, supportive evidence comes from testimonials gathered from other parents (e.g., XIII; XXVI). Taken together, these sources strengthen the authors’ arguments, but, especially, they normalise the experiences of emptiness or suffering. It is implied that there are a lot of “us” feeling this way (e.g., XII; XV; XXVI; XXVIII).

Unsurprisingly for this genre, there is the focus on struggles, and then, on the adopted coping mechanisms. Further, this may (!) be an adequate depiction of the self-help books’ readers, who, in search for advice, consume the book. However, it seems problematic that particular experiences are essentialised and homogenised, carrying with them normative expectations. Declaring it ‘natural’ for mothers to feel sad, lonely or depressed when their children leave, and depicting mothers as ‘good’ and ‘loving’ who report about a void and mourning when the children have moved out, creates a kind of moral pressure. Several passages imply that if a mother does not feel as if “a part of [one]self has been taken away” (XXV, 56), she may not have loved her children (enough) or has not taken the mother’s role seriously. Alternatively, she might not have acted as a mother at all – but rather as a father who are said to have a life besides the family (e.g., XXV) and a self not exclusively defined by parenthood. Taken together, this contributes to the reproduction of particular ideas of what it means to be a mother: it is a life defining und filling task. Accordingly, motherhood is marked by “exclusiveness”, “voluntary sacrifices” for the family as well as a (biological pre-prepared) “natural suffering” when active mothering ends. It also reinforces particular images of the assumed readership. Even if they are emancipated, independent and “anything but a passive ‘stay-at-home mum’” (XVII, 12), they are assumed to lose the core of their selves once their children have left. They get the “Mother Blues” and ask themselves: “What will I be?” (XVII); they face the emptiness of the nest and their life, wondering whether it will ever be filled again.

Within this horizon, advice is suggested on how to cope with the (potential) void and how to find new meaning in life. Genre-typically, yet unexpectedly, given the essentialist perception of motherhood, the books suggest exploring, finding or rediscovering one’s true self (e.g., V; VI). Thus, the authors imply (yet never explicate) that this self was either lost through active mothering, or never fully realised by becoming a mother. Accordingly, the regained resources, especially free time, should be used to try out new hobbies (somewhat clichéd, e.g., yoga). Moreover, readers are encouraged to recognise and exploit new options, such as rearranging the children’s room for themselves, revitalising the couple’s relationship (e.g., XXII, 199 pp.) or concentrating on the grandchildren (e.g., XV, 151 pp.).

In giving advice like this, the books further mirror the traditional family structures centred around a full-time mother in a stable (heterosexual) relationship who is financially secure thanks to her partner’s income. This may explain the striking lack of topics such as financial hardship or economic necessities.

Two factors appear paradoxical in this context. First, these books are primarily written, at least in part, autobiographically by female journalists, therapists, or academics; in other words, by working mothers who pursued their careers (including authoring self-help books on family transitions). Nevertheless, employment is presented as one of the least promising options in the empty nest phase. As mothers “have often given up their jobs to raise their children or have only worked part-time” (XIII, 7), re-entering the workforce and finding fulfilling employment is presented as unlikely, as is securing an income to live on. Therefore, they are encouraged to search for a meaningful activity elsewhere, for instance, again clichéd, in the field of “voluntary work in the social and church sector” (VI, 69).

Second, the topic of gender differentiating effects of parenthood on career opportunities, financial dependency within the parental couple, and inequalities between fathers and mothers disappears from the empty nest guides, in parallel with an increased societal importance and discursive attention assigned to the ideals of (a) gender equity and (b) the compatibility of family responsibilities and paid employment. Only the oldest guide, published in 1987, dedicates a full chapter to the employment of mothers. It emphasises the relevance of self-earned money, recommends part-time work or self-employment already before the children leave home, and points out the possibility of a stronger focus on employment afterwards (I, 150). All other self-help manuals, if they mention economic topics at all, do so only in passing. Instead, they deal with a particular way of ‘being a mother’ as presumed ‘default’, or at least as lived reality of the self-help books’ authors and readers: while mothers practice highly child-centred mothering, fathers are the main (or sole) breadwinners. This model seems to guarantee a quite comfortable lifestyle, children’s higher education and extended stays abroad, etc. – at least as long as the couple stays together. Separation is addressed only sporadically, and, when it is, it is not in terms of finance, but rather in terms of loneliness. It is posited that single mothers struggle particularly when children leave as they suffer from the empty nest and the lack of a partner, i.e., they are presented as ‘normatively deficient’ in two respects, which is thought to make them vulnerable to severe loneliness.

Overall, the guides largely ignore historical and biographical change and operate with the norm of a traditional life-long lasting (modernised) breadwinner marriage. This goes hand in hand with gendering the ‘empty nest’. Accordingly, mothers enter a critical phase when their children move out, leaving them as a “childless mother” (XVI, 125). This seems to rest on a highly limited and static understanding of motherhood as well as a binary and one-dimensional perception of presence (Döbler, 2020): physical distance prevents the performance of a mother’s role; mothering is confined to co-residence. Such assumptions neglect the shifting practices of mothering, e.g., from reproductive to emotional labour (Hogg et al., 2004), and technological change enabling to mother digitally from a distance – these are practices narrated extensively by the interviewees.

4. The Interviews: Mothers’ Self-Descriptions

Subsequently, I sketch the reconstructed biographies of my interviewees, focusing on the mothers’ self-understanding, and experiences of motherhood and mothering.

Annegret (60) has led a life of deliberate planning. Long before she had children, she had decided to become a stay-at-home mother, which was a choice that she and her husband, Anton (60), frame as “natural” and “typical”. She chose a profession that allowed for extended parental leave and part-time work. While Anton followed a linear path from education to full-time work with little involvement in caregiving, Annegret followed the traditional three-phase female life course: (1) full-time employment; (2) twenty years devoted to the family, during which she solely cared for the children, providing them with a “warm home”, “safety net” and space for autonomous self-exploration, which is believed to be unattainable in professional childcare; and (3) a return to part-time work once her youngest son, who was then thirteen, no longer needed full-time care. Still, she continued to align her work hours with the children’s schedules and continued to centre her life around them. Today, she values her ongoing maternal role during weekly family gatherings as much as she values having time to herself, time for her job, and time with Anton.

Katrin’s (57) life parallels Annegret’s, though she frames it differently. While Annegret confidently aligns her planned and lived role as a mother, Katrin appears torn between the ideals of gender equality and her deep commitment to motherhood. Her statement that she and her husband Klaus (58) wanted to be “progressive” but ended up in a traditional family therefore seems to be more of an attempt to conform to the image of a well-educated middle-class woman than an expression of conviction. Katrin repeatedly portrays motherhood and intensive parenting as essential for a woman’s fulfilment. She feels sorry for her childless friends, has tried to conceive using fertility treatment, and has taken extended maternity leave after the birth of both her daughters to satisfy her desire to “stay with the child”. Nevertheless, she stresses both the joys and strains of mothering – caring for young children, navigating teenage challenges, and losing personal freedom – while emphasizing the deep emotional bond she shares with her daughters, especially the younger one, whom she describes as a “best friend”. Now, as her younger daughter prepares to leave home, Katrin wonders about her relationship with her husband, which had taken a back seat to parenthood for more than two decades, and about her identity beyond active motherhood.

While Annegret confidently orients herself and her life at the traditional female roles and life-courses with a clear ideal notion of motherhood and the corresponding understanding of family life, Katrin’s self-description indicates the acknowledgement of contradictory discursive demands and social norms directed at women which need to be aligned, at least communicatively. In Susanne’s case this appears to be more than a narrative challenge. Her self-presentation reveals a bundle of desires, plans and values which still seem difficult to reconcile within a woman’s life-course.

Susanne (60) wanted both motherhood and independence as well as self-fulfilment through employment. However, after her first child was born, she became the “family manager” at the cost of working in her studied field. For both practical reasons and self-worth, she professionalized this role – by taking charge of household and childcare, organizing five international moves, and managing ongoing financial strain due to her husband’s precarious, mobile career until he secured a rare permanent position. As she had to take on any job to support the family, she could neither be a full-time mother nor a “modern working mother” with a career. Consequently, like Annegret and Katrin, she expected motherhood to change her life, but, unlike them, she had envisioned a path with greater social integration beyond being someone’s mother or wife. Additionally, unlike the others, she had to reinvent herself: being out of her field too long made returning impossible. Upon acknowledging that “this door had closed” and that lacking a personal “project when mothering becomes less”, she re-enrolled in university. Her new career from this second degree became a key part of her identity. Still, she mothers intensively from a distance and stays deeply involved in her children’s lives. She believes that children never stop being children – and so she will never stop being their mother, though her role evolves over time and differs with each child.

Benisha (53) also emphasizes lifelong parent-child relationships and evolving parenting. Supported by her parents-in-law, with whom the family had been sharing the household when the children were born, she took the “typical three months” of parental leave and “naturally” returned to full-time work. However, when her husband Bendre (57) was transferred to another city, the family “as a matter of course” moved too, and Benisha lost her support network. Uncomfortable with hiring outside help, she took over childcare. Like Susanne, she prioritized family duties but sought compatible work, thereby becoming a freelance English teacher and culture coach for people working abroad. This allowed her to align paid work with caregiving – preparing meals and connecting during family meals. When Bendre was relocated again, the family moved abroad. Like Susanne, Benisha organized the move. Contrary to her, however, Benisha profited from her professional skills: she became the family’s pioneer (finding housing, schools, building connections), and continued freelancing. Overall, her family has been adapting pragmatically to new conditions, allocating care work based on opportunity, need, preference, and ability of all involved parties. For Benisha, motherhood means neither always prioritizing the children nor doing all care alone, but supporting independence, teaching responsibility, and fostering intergenerational obligation. She holds a consistent view of motherhood, even as its form changes, alongside her roles as a wife and an independent woman.

While Benisha refers to a socially accepted “normality” of career-oriented motherhood, Rosemarie (56) and her husband Roger (55) frame their arrangement in terms of equality. They split care tasks 50:50 and both work nearly full-time, as long as adequate childcare is available. Being aware that this deviates from the prevailing norms, Rosemarie justifies placing her daughter in a nursery at a very early age by appealing to the value of early education. She highlights the nursery’s high standards, by arguing that no mother could offer the “same quality of education while managing household duties”. This challenges the assumed link between full-time mothering and good parenting in earlier cases, redefining good motherhood as enabling children’s intellectual growth through stimulating environments. However, when the family relocated and their second child was born, lack of quality childcare led Rosemarie to take over their education. Like Susanne and Benisha, her life became shaped by the need to mother herself. Yet, unlike Susanne, she does not complain, and, unlike Benisha, she does not call it “natural”. As with Annegret and Katrin, parental roles are complementary, but Rosemarie’s path – like those of Susanne and Benisha – neither fits the traditional female three-phase model nor the linear male career trajectory. Additionally, it does not seem to be motherhood which defines her life. Instead, it is shaped by factors such as temporary contracts and the limited availability of full-time position in academia affecting both Rosemarie and Roger. They divide labour not by gender, but rather by opportunity and necessity, while pragmatically responding to shifting conditions in paid and care work. Rosemarie eventually returned to extended part-time work, while Roger scheduled breaks around school hours and acted as a househusband during unemployment. Their parenting ideal is based on mutual involvement and intellectual exchange: both maintain close, equal relationships with their children, with good parenting defined by educational quality and reciprocal intellectual growth.

Like the first three interviews, motherhood is highly important to Marianne (60), but equally central is maintaining a life beyond it. This results in a distinct approach to motherhood and family life. Before having her own children, Marianne’s life included several resets: after studying social pedagogy, she worked part-time as a social worker, experienced unemployment, retrained in PR, cared for her brother’s children after he was widowed, and worked full-time in marketing. Having given up on motherhood, she unexpectedly became pregnant and gave birth to twins at thirty-eight after a difficult pregnancy. She took two years of parental leave, while her partner Manfred (60) paused his studies for a semester and later aligned his freelance work with caregiving duties. With his flexible schedule, Marianne gradually increased her working hours, and the couple shared childcare equally. However, Marianne found the division of household labour unfair and separated from Manfred when the twins were fourteen. The separation resolved their conflicts, and they continued co-parenting in separate homes. Marianne strongly values both “having children” and autonomy, defining motherhood by relationship quality and a gender-neutral division of care. For her, the members of a cohabiting family have to share the tasks as in a “socially functioning flat-sharing community”, thus, giving up hands-on care tasks, such as cooking or laundry, long before the twins’ departure does not diminish her role as a good mother.

All in all, the interviewees reveal similarities regarding the following points: the interviewed mothers:

• perform, admittedly over different time spans, full-time motherhood;

• mother with a focus on attachment and ‘good’, ‘lasting’ parent-child relationships;

• value their children’s well-being, needs, and interests;

• organise their lives with and around the children at least until these move out;

• built their identities upon being a ‘good’ mother.

However, there are differences regarding the:

• correspondence between planned and realised life-courses and the varying ideals the mothers try to live up to;

• value placed on different parties’ autonomy and self-realisation and the mothers’ prioritisation of children’s needs;

• involvement of fathers in everyday family life and whether it is a parent- or mother-child(ren) relationship;

• ways of mothering, and the realisation of motherhood subsequent to the children’s move out.

Thus, the interviews have revealed a variety of (practically realised) understandings of motherhood, needs to mother, and ways of being a mother across life – contrary to the self-help books which operate with rather uniform and static notions.

5. The Empty Nest in Media Discourse and Self-Representations

In the following, I compare the discursive conceptualisation of the empty nest and post-motherhood as depicted in self-help books with women’s interpretations of lived mothering across time communicatively presented in interviews.

First, books and interviewees deal with gender-differentiated parenthood and its impacts on the life courses as it manifests itself at the time the children move out. However, while the self-help books reproduce unquestioned homogenised notions of (good) motherhood, the interviewees show active reflections about what a mother’s role is and report a variety of dynamically modified performances. On a daily basis, they have redefined being a mother, reinterpreted motherhood, and refigured mothering practices. Long before the children’s departure, they have planned post-parental life, (re)created identities besides motherhood, and modified their relationships with the children – over time, parents engage with them increasingly on eye-level, treating them as adults or equals. Today, they bridge distances technologically. This contrasts with the books. Where the interviews highlight change, the books emphasise the end of mothering, a void in life, and the lack of ideas who or what one can be after the life-defining task has been completed. Accordingly, the children’s move challenges the mothers’ self-understanding and identity, as well as the mother-child relationship.

Second, the mothers I have talked to emphasise that they have been highly involved in their offspring’s lives. Thereby, they have managed, accompanied, and witnessed several moments of children’s detachment and steps towards independence. Thus, they have acquired experience, and even expertise in dealing with (smaller versions of) letting go. Additionally, being involved in the children’s moving process has enabled the mothers to prepare themselves, allowing them to perceive the relocation as a somehow logical consequence of a long-term development. Nevertheless, the interviewees depict the move itself as an important event which triggers unexpected emotional reaction. However, whereas they describe such affective reactions as temporally limited, linked to the day when the move becomes real, as shared ‘nervousness’ with their children or as empathy with their anxiety, the books depict mothers entering a prolonged phase of suffering, grieving, and mourning. No interviewee reports anything similar. Instead, they continue to mother from a distance and embrace their own (new) ‘projects’.

Third, given the notable persistence and ubiquity of respective idea(l)s mirrored in the books and the emergence of ‘new’ demands, such as appeals to gender equality and egalitarian care arrangements, the interviewees have and do deal with contradictory expectations experienced (in particular) as members of the well-educated middle-class. Thus, while self-help books’ authors link uniform, homogenised and moralising images about mothers with implied or (latently) demanded grieving, the interviewed women resist such one-dimensional images. Instead, they present changing maternal practices, rather than the end of being a mother when the children have departed.

Fourth, the guides posit an ‘emptiness’ after the children have departed and advise to fill the resulting void with leisure and the revitalisation of the couple relationship. They almost entirely neglect the topic of employment and social appreciation based on labour market integration. In contrast, the interviewees emphasise (re)gained resources, primarily time, which they begin to invest in their own life, in social contacts beyond the family, and paid work. This results in highly valued (financial) independence, self-fulfilment, and social recognition. Nevertheless, the stereotyping of empty nest mothers and the presupposed maternal grief presented – perhaps not only – in the analysed books can become problematic, e.g., when ‘suffering’ is taken as a normative marker of being a ‘good’ mother, as some interviews suggest. The interviewees feel socially urged to legitimise their positive feelings about their children’s departure without being seen as a ‘Rabenmutter’ or devaluing the parent-child relationship as it is indicated by their routine in talking about realising motherhood adapted to changing circumstances and children’s age, and their emphasises on continued mothering.

6. Conclusion

Interested in motherhood over the life-course, I comparatively analysed self-help books which deal with the so-called empty nest and interviews with mothers of grown-ups. Rooted in a practice theoretically oriented, constructivist perspective, I was open to find different descriptions of doing motherhood and mothering (in the context of this transition). Yet it came as surprise to find (a) remarkable differences between the books and the interviews, and (b) a quite uniform presentation of being a mother across the books. The books’ depictions document and re- or coproduce sociocultural ideas such as maternal love or the bourgeois family, and parenting ideologies which have gained traction since the late 1980s, e.g., attachment and intensive parenting (Ennis, 2014; Hays, 1996). Women encounter these ideas and ideologies not only upon entering the empty nest and reading such guides.

Notwithstanding the fact that I was able to show a variety of mothering practices and differing representations of motherhood, my material covers only a part of the discourse and a particular sample’s self-reflexion about their lived and practiced motherhood. This is due to:

• The overall context of the project, which focuses on the division of labour in heterosexual couples in Germany;

• The aim of interviewing those people who are also the presumed readers of the self-help books, namely, well-educated, middle-class parents;

• This article’s interest in motherhood in face of children’s departure, resulting in a sample of mothers of approximately the same age who had their first children in the early 1990s.

This might suggest that some of my findings are unique, e.g., due to the national specificity in Germany (cf. Section 1) or the sociodemographic of my sample. However, first, some of my findings align with international research. Additionally, there are no noticeable or systematic differences between those books written in German or translated from English into German suggesting that:

• Ideals of motherhood may overshadow institutional differences (e.g., in tax or labour market structures). If sociocultural norms are sufficiently shared across countries, they may exert stronger influence on how motherhood (in the empty nest) is perceived than national policies do. This suggests a need for cross-country comparisons that more clearly disentangle cultural from structural effects.

• Norms and expertise have been imported from (Anglo-)American contexts to Germany, resulting in a shared discursive repertoire. This calls for a broader, possibly historically informed discourse analysis of the emergence and transnational circulation of the empty nest discourse in self-help media.

• Much of the existing literature may be concerned less with lived experience than with normative scripts and cultural ideals of motherhood, i.e., with the way how mothers are imagined and how they ‘ought to’ feel upon entering the empty nest phase. This indicates the need to reflect on empty nest research, which might appear less as a depiction of maternal realities, but as a reflection of ideals, myths, and abstractions surrounding motherhood, as well as a focus on the temporary emotional reaction ‘when it becomes real’.

Second, the homogeneity of my sample enabled me to reconstruct a nuanced ‘within group picture’ of how mothers retrospectively interpret their experiences of motherhood despite common class, educational, and familial coordinates. However, incorporating greater sociodemographic diversity, e.g., women from lower-income backgrounds, single mothers, breadwinner mothers, or those with migration backgrounds, would likely bring to light further dimensions of meaning, experience, and normativity. These groups may face different constraints and moral expectations. Unlike well-educated, middle-class mothers, who are presumed to have the economic and cultural capital to choose whether to work, they might follow different motherhood paths shaped by structural necessity rather than post-materialist ideals such as self-realisation or identity work. Future research should thus explore whether and how the understandings and practices of motherhood evolve differently across class, race, migration status, and religion. We might enquire into the following: Do retrospective accounts of parenting and children’s departure differ among these groups? If so, what does this reveal about the intersection of structural conditions and cultural scripts? Additionally, the sample may have failed to capture the full spectrum of middle-class women’s experiences and perceptions of motherhood over time or their diverse ways of coping with the transition to post-parental life. Thus, a larger sample might reveal additional interpretations of ‘good motherhood’, including more rigid or traditional constructions of motherhood which are challenged by reaching the end of the active parenting phase. For example, I did not interview mothers diagnosed with the ‘empty nest syndrome’, and none of the participants reported severe difficulties in letting go. Their self-presentations might resonate more closely with presentations in the books.

Moreover, juxtaposing interview-based self-presentations with the discursive representations of motherhood in self-help guides against the backdrop of a sociodemographic match revealed significant divergences in how the role of the ‘good mother’ is articulated and made sense of over time. This indicates that there is no one-to-one correspondence between public discourse and personal experience, even if both are shaped by – a probably similar – sociocultural background. Future research might explore intertextual dynamics further, e.g., by varying the forms of self-help material – such as online communities, advice blogs, or social media content – or by investigating the influence of empty nest self-help literature compared to antenatal and parenting advice literature, which has been shown to shape expectations and practices of parents-to-be. Additionally, the different modes of presenting motherhood could be incorporated in the analysis more systematically. For instance, rather than presenting a personal self, the books depict a generalised narrative by addressing a generalised readership, and meet certain media-discursive requirements regarding the style and content of self-help books. Contrary to the interviewees who might fear losing their face by framing ambivalence in terms of personal loss – of purpose, identity, and meaning – once children have become independent, the books can deal with this openly. In order to trace possible ‘audience effects’, self-presentations in different communicative settings could be compared.

Finally, I addressed ‘fatherhood’ only rarely, and, if so, primarily in contrast to ‘motherhood’. This has three reasons: (a) it mirrors how ‘fathers’ and ‘being a father’ is addressed in the interviews when motherhood or maternal actions are portrayed. (b) Fatherhood is largely absent in the self-help books, and the primary psychological research about ‘the empty nest’ renders this phase a maternal crisis in midlife too. (c) This led me to formulate this paper’s research question with a focus on mothers – at the expense of a more thorough analysis of fatherhood. While this approach to ‘fathers’ as a contrast is grounded in the empirical material and in literature, it does not do justice to the complex nature of fatherhood. Therefore, it should be discussed in more detail in future studies – especially as we do know even less about fatherhood across time and fathers’ experience of the children’s departure.

Consequently, there is still a lot to learn about motherhood idea(l)s, the experience and self-perception of mothers, understandings of ‘good’, ‘proper’, ‘adequate’, etc. mothering or experienced discrepancies between the desired, planned and realised life-courses of mothers – as well as those of fathers. Research should therefore be continued, by expanding and deepening what my exploratory case study with its insights into how middle-class mothering is constructed and reproduced both textually and experientially. Nevertheless, already now, my findings depict ‘motherhood’ as a social construct, ‘being a mother’ as a situated expression of dynamically adapted practices, and ‘mothering’ as a context-sensitive performance of intergenerational care requirements which vary across (historic and biographical) time and culture.

References

Berger, P. L., Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Penguin Books.

Bohnsack, R. (2001). Dokumentarische Methode: Theorie und Praxis wissenssoziologischer Interpretation. In T. Hug (Ed.), Wie kommt Wissenschaft zum Wissen? Band 3: Einführung in die Methodologie der Sozial- und Kulturwissenschaften (pp. 326–345). Schneider Verlag Hohengehren.

Döbler, M. K. (2020). Nicht-Präsenz in Paarbeziehungen. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-29448-9

Döbler, M., Müller, M., & Zillien, N. (2025). Mutterschaft und Vaterschaft in Lebenslaufperspektive – Geschlechterdifferenzen im Übergang zum Empty Nest. In Jahrbuch für Europäische Ethnologie. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Schöningh. https://doi.org/10.30965/9783657797189_019

Ennis, L. R. (2014). Intensive Mothering: Revisiting the Issue Today. In L. R. Ennis (Ed.), Intensive Mothering: The Cultural Contradictions of Modern Motherhood (pp.1–23). Demeter Press.

Grant, J. (1998). Raising Baby by the Book. The Education of American Mothers. Yale University Press.

Hartanto, A., Sim, L., Lee, D., Majeed, N. M., & Yong, J. C. (2024). Cultural contexts differentially shape parents’ loneliness and wellbeing during the empty nest period. Communications Psychology, 2(1), Article 105. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-024-00156-8

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press.

Hogg, M. K., Folkman Curasi, C., & Maclaran, P. (2004). The (re‐)configuration of production and consumption in empty nest households/families. Consumption Markets & Culture, 7(3), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/1025386042000271351

Hulbert, A. (2003). Raising America: experts, parents, and a century of advice about children. Vintage Books.

Keller, R. (2005). Analysing Discourse. An Approach From the Sociology of Knowledge. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(3), Article 32. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.3.19

Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2024). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Umsetzung mit Software und künstlicher Intelligenz (6. (überarbeitete und erweiterte)). Beltz Juventa.

Lefton, T. (1996). Empty Nests, Full Pockets. Brandweek, 37(39), 36–40.

Lück, D., & Ruckdeschel, K. (2018). Clear in its core, blurred in the outer contours: culturally normative conceptions of the family in Germany. European Societies, 20(5), 715–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1473624

Mitchell, B. A. (2019). Empty Nest. In D. Gu & M. E. Dupre (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging (pp. 1–6). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69892-2_317-1

Mitchell, B. A., & Lovegreen, L. D. (2009). The Empty Nest Syndrome in Midlife Families. Journal of Family Issues, 30(12), 1651–1670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X09339020

Müller, M., & Zillien, N. (2016). Das Rätsel der Retraditionalisierung – Zur Verweiblichung von Elternschaft in Geburtsvorbereitungskursen. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 68(3), 409–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-016-0374-5

Newman, D. M., & Grauerholz, L. (2002). Sociology of Families (2nd ed.). Pine Forge Press.

Randhawa, M., & Kaur, J. (2021). Acknowledging Empty Nest Syndrome: Eastern and Western Perspective. Mind and Society, 10(3), 38–42.

Raup, J., & Myers, J. (1989). The Empty Nest Syndrome: Myth or Reality? Journal of Counseling & Development, 68(2), 180–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1989.tb01353.x

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: a development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203335697-23

Reckwitz, A. (2020). Society of Singularities. Polity Press.

Rose, L., & Schmied-Knittel, I. (2011). Magie und Technik: Moderne Geburt zwischen biografischem Event und kritischem Ereignis. In P. I. Villa, S. Moebius, & B. Thiessen (Eds.), Soziologie der Geburt: Diskurse, Praktiken und Perspektiven (pp. 75–100). Campus.

Zeller, C. (2018). Warum Eltern Ratgeber lesen: Eine soziologische Studie. Frankfurter Beiträge zur Soziologie und Sozialphilosophie: Band 28. Campus Verlag.

1 Despite acknowledging the problematic nature of this metaphor, which has been argued to elicit and perpetuate specific negative images, the prevailing usage of the term within both popular discourse and institutional frameworks renders it a salient point of reference (Mitchell, 2019; Randhawa & Kaur, 2021). Consequently, I will employ this term as well but ask readers to bear the contested status in mind.