Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2020, vol. 45, pp. 30–41 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.45.2

Promoting the Cultural Understanding of a Student in a General Education School: Teachers’ Experiences and Challenges

Ilze Briška

University of Latvia

ilze.briska@lu.lv

Gunta Siliņa-Jasjukeviča

University of Latvia

gunta.silina-jasjukevica@lu.lv

Abstract. Cultural understanding is a basis for competence-oriented general education. Teachers are responsible for applied content and methods that are used to purposefully lead school students to that result.

The readiness of teachers to promote the cultural understanding of primary school students was explored in a mixed-methods study. The findings indicated aspects that teachers consider relevant as well as the main problems and gaps between theoretical principles recognised as essential by educational policy, and teachers’ beliefs and practices.

Mokinių kultūrinio supratingumo skatinimas bendrojo ugdymo mokyklose: mokytojų patirtys ir iššūkiai

Santrauka. Kultūrinis supratingumas yra į kompetencijas orientuoto bendrojo ugdymo pagrindas. Todėl mokytojai yra atsakingi už taikomą turinį ir metodus, kurie mokinius turėtų vesti link to. Gilinantis į iššūkius, su kuriais susiduria mokytojai, norėdami užtikrinti kuo sėkmingesnį mokinių kultūrinio supratingumo ugdymą bendrojo ugdymo mokyklose, šiuo straipsniu siekiama identifikuoti dabartinius tikslus, galinčius padėti stiprinti mokytojų ugdymo turinį, profesinį jų rengimą ir mokymo pagalbą.

Mokytojų pasiruošimas skatinti pradinių mokyklų mokinių kultūrinį supratingumą analizuotas atliekant mišrių metodų tyrimą. Gauti rezultatai atskleidė mokytojams svarbius aspektus, identifikavo pagrindines problemas ir spragas, egzistuojančias tarp teorinių principų, kurie svarbūs švietimo politikai ir pačių mokytojų įsitikinimams bei praktikoms.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: kultūrinis supratingumas, bendrasis ugdymas, mokytojų patirtis, mišrių metodų tyrimas.

Received: 02/11/2020. Accepted: 04/12/2020

Copyright © Ilze Briška, Gunta Siliņa-Jasjukeviča

Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The problem is that such an approach is new for teachers. Many of them had been doing this intuitively all the time, but now their practice must be reflected upon and purposefully promoted. The question is – how ready teachers are, and what the biggest gaps between the demands and their competence are.

In previous studies, authors have analysed the concept of cultural understanding, constructed a set of pedagogical principles for realisation of it in transformative and in-depth education, and highlighted the potential misunderstandings (Briška & Kalēja-Gasparoviča, 2020; Siliņa-Jasjukeviča & Briška, 2016; Siliņa-Jasjukeviča, Briška, & Juškevičiene, 2019). Structured questionnaire created in the study was tested and found to be a suitable tool for the measurement and analysis of teacher competence to promote students’ cultural understanding.

The aim of this study is to identify actual goals for the development of teacher education curriculum, professional development and teaching aids by investigating in-service teacher’s challenges for the successful promotion of students’ cultural understanding in general school.

To meet the aim, 255 Latvian teachers were asked to complete a survey. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of the data was performed to clarify their practices, beliefs and professional needs related to the problem.

Theoretical background

Cultural understanding

Cultural and learning theories are useful in the investigation of teacher competence to promote cultural understanding in students. Different cultural theories provide various explanations of the concepts culture and cultural understanding, but learning theories analyse approaches to how these concepts can be realised in educational practice.

According to Griswold (2012), culture can be attributed to art (where culture is separated from everyday living and is comprised of elevated activities and materials), to an individual sense (culture as a toolkit used by humans to make sense of their world), to societal norms (culture as a coherent system, of norms, beliefs, values, and attitudes), or to the existential reality of being a human (culture as a phenomenon, which affects social existence) (Griswold, 2012). Each of these perspectives implies a different learning content, process, and outcome. The approach of the symbolic anthropologist was recognised as the most appropriate for transformative learning. It explains the concept of culture as an accumulated totality of symbolic systems in terms of which people make sense of themselves, the world, as well as the way they represent themselves to themselves and to others (Banks, Cherry& McGee, 2015; Geertz, 1973). Culture can be reached only through the participation of each member in the community and the prism of an individual’s personal significance and the values of the society in which they live (Siliņa-Jasjukeviča & Briška, 2019, 2016).

From this it follows that (1) a purposeful development of cultural understanding can be realised in the content of each school subject of primary education, not only in the arts subjects, and (2) culture is not just knowing beliefs and values, but it affects all situations in life and people’s subjective sense of life.

Cultural understanding is a result of learning. Learning theories, such as social constructivism, experiential learning, in-depth learning, and existential learning provide ideas of how cultural understanding can be developed in primary education.

According to socio-cultural learning theories, understanding is formed if learning is considering a person’s subjective sense, emotional experiences, layers of meanings, symbols, and complexities within a specific context (Grossberg, 2010; Kron, 2004). Held also points to the significance of learning as an individual construction of knowledge in accordance with one’s subjective sense and experience, combined with social learning and the communication of cultural contexts (Helds, 2006).

Experiential learning theorists develop the idea of including the learner’s personal and cultural experiences in the educational process, too (Dewey, 1979; Griffin, Holford, & Jarvis, 2003).

In in-depth learning theories, the highest manifestation of learning is described not only as a cognition which involves processes of concluding, interpreting, and estimating, but as becoming a transformed, competent person (Bennett, Grossberg, & Williams, 2005; Grossberg, 2010; Halupa, 2016).

Thus, the objective and critical explanations of cultural phenomena are not enough for deep cultural understanding. Therefore, teaching that considers the student’s inner world, personal experiences, and life events is valid for personally meaningful learning and human transformation.

Previous research highlighted one or another range of problems related to the atmosphere and mutual relationships in school. This aspect can be characterised as a school culture. Attitudes, notions of desired behaviours and actions, traditions, symbols, rituals, and human relationships at school are determined by the beliefs and values of all those involved in the educational process (Fullan, 2016; Siliņa-Jasjukeviča & Briška, 2019). Whether they are clearly declared or hidden, they provide the student with direct primary experiences, and are therefore important for the development of cultural understanding. Teachers’ responsibility here is the conscious building of an atmosphere, regulations, and relationships favourable for the development of all aspects of students’ cultural understanding.

From theoretical analysis, teachers’ opportunities to foster the development of primary school students’ cultural understanding are derived:

1) incorporating the cultural issues in each school subject,

2) promoting personally meaningful learning,

3) adjusting the learning to actual situations and life contexts,

4) cultivating collaborative, sincere, and accepting relationships in the classroom.

From this follows that teachers’ practices, experiences, and beliefs related to the integration of cultural issues in cross-curriculum, promoting personally meaningful learning for students, adjusting the learning to actual situations and life contexts, cultivating collaborative, sincere, and accepting relationships in the classroom, needs to be clarified to answer the question of which aspects are familiar for them, and which are uncommon and challenging.

Methodology

Method and data collection

A questionnaire was developed to investigate teachers beliefs, practices, and needs. It is structured in four parts related to the respondent’s experiences and priorities regarding learning the content of culture, the process, and contexts of learning, and building the relationship in a classroom. Each part contains Likert scale questions and open-ended questions to help respondents to describe the most urgent problems, challenges, and confusions related to the development of school students’ cultural understanding in the context of educational reforms.

The questions were formulated in a language appropriate to the professional vocabulary of the group, but at the same time were simple and easy to understand (McLeod, 2018).

Data were obtained in an electronic questionnaire. Descriptive statistics and correlations of quantitative data, and the content analysis of qualitative data (respondents’ answers to open-ended questions) were undertaken. Quantitative and qualitative data were compared to find the similarities and contradictions in teachers’ ideas on how to promote student’s cultural understanding in their practical daily work experiences.

Sample: 255 in-service teachers, graduates from University of Latvia of the last 15 years, presenting different regions of Latvia and various fields of education - language (69), math (12), science (6), social sciences (24), arts (27), technology (3), sport (6) and primary education teachers who teach all school subjects (108).

Data were obtained in September and October 2020.

Results

The data for each dimension (content of learning, process of learning, context of learning, and school culture) were analysed separately.

1. The content of learning

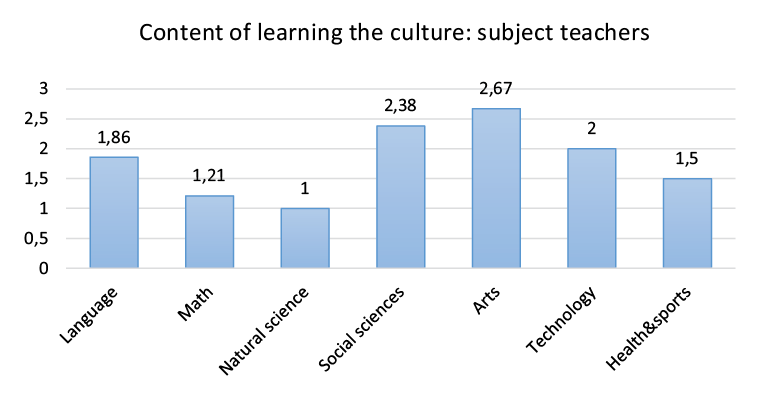

The first part of survey investigated teachers’ conceptions about the possibility of integrating cultural contexts into the content of their subject. In Figure 1, the experiences of different subject teachers are presented.

Figure 1. Different subject teachers’ experiences in integrating cultural issues in the content of learning.

We can see that teachers of arts and social sciences feel a responsibility to integrate cultural issues in their subjects. For teachers of languages and technologies, this indicator is at a lower level, but teachers of math and natural sciences mostly do not care about the manifestations of cultural values in their field. Only two natural sciences teachers stated “I do it often” and six teachers said they did it “sometimes.”

In open-ended questions, teachers used expressions like “culture refers to the specifics of the subject”, and “my subject does not provide a space for cultural issues”, which confirms and explains the quantitative results. If the teacher says that their subject is not appropriate for learning the culture, it means that the teacher does not understand the contextual component of learning.

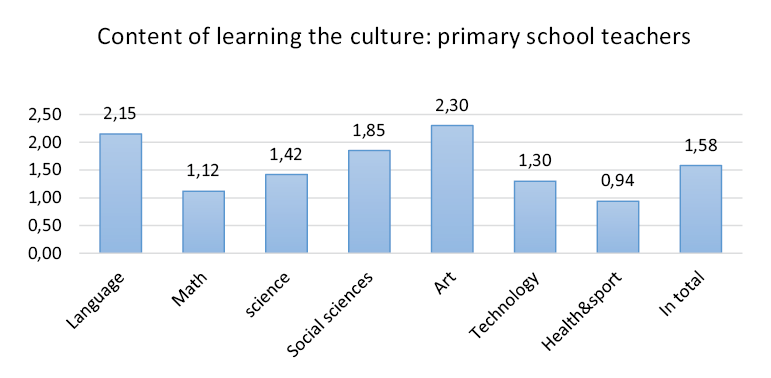

Overall, the same conceptions are demonstrated by primary school teachers, who teach all subjects (Figure 2).

When speaking about their problems and challenges, some primary school teachers demonstrated that they believe that the focus in primary education is mostly on learning languages and math, and this does not allow to them to dedicate time to cultural issues (“[we need to] realise the whole programme”, “to follow the whole textbook”). In contrast to the subject teachers, primary school teachers see the possibility of including cultural issues in integrated learning to “guarantee the possibility that the student sees the wider world”, but they worried about the lack of methodical aids for it.

Figure 2. How primary school teachers integrate cultural issues in the content of learning.

Traditionally, in education, the arts represent all the cultural issues, but social sciences discuss the virtues. It can be concluded that teachers mostly see culture as being attributable to a complex set of societal norms or aesthetics which affect social existence, rather than a person’s individual sense nor phenomenon (Griswold, 2012). Data show that the realisation of cultural contexts in other fields of education, especially in mathematics, natural sciences, and technology is not common for teachers. Thus, it can be concluded that teachers do not use the social-constructivist approach to learning, which declares that life (cultural) contexts are present in all fields of education (Helds, 2006). Teachers’ dominant experiences can be interpreted as manifestations of a transmissive approach to education.

2. Process of learning

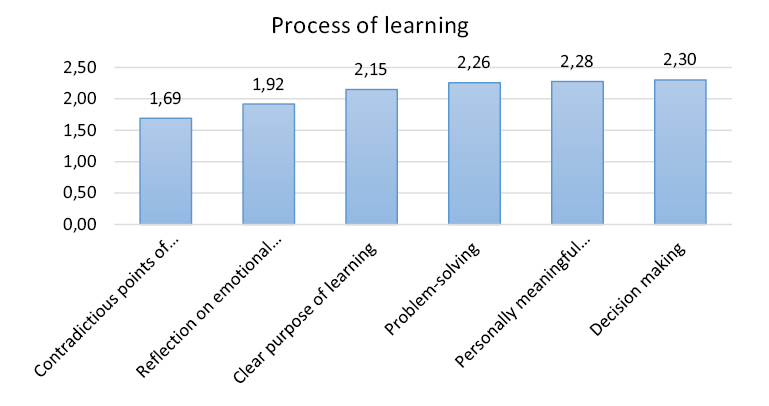

The second part of the survey investigates teachers’ conceptions and practices of the organisation of the transformative and personally meaningful process of learning (Figure 3).

In general, quantitative research shows that most teachers highly evaluate their practices to provide all the components of the educational process necessary for promoting students’ cultural understanding (the average value fluctuates around 2.1).

However, an analysis of the answers to the open questions shows a different picture. A relatively large number of teachers’ statements (52 cases) such as: “students are not interested in the suggested tasks”, “students lack interest and motivation to get involved”, “students are passive, not interested”, and so on, suggest that the teacher had not provided personally meaningful teaching.

Figure 3. Teachers’ experiences of providing in-depth learning

The majority of respondents (192) attach importance to students’ understanding of the purpose of learning; however, almost a quarter of teachers (63) do so only in isolated cases, and three of them, never. If a student does not understand the purpose of learning, and the result to be achieved is not understandable and personally important to them, then learning cannot be deep (Kron, 2004; Tiļļa, 2008).

Paying attention to students’ emotions often is recognised by 129, but always – by 69 respondents. Sixty teachers do so in isolated cases, and six not at all. Thus, almost a quarter of teachers do not attach importance to the emotional aspect of teaching. Respondents rather state that “there is not enough time for the analysis of emotional experience”, “there is no time for individual conversations”, “there is a lack of experience to implement it”. Respondents note that “the situation would be improved by teaching materials that include tasks to evaluate emotional experiences”. If learning excludes the reflection of a learner’s emotional experience, it becomes mechanical. Students lose interest without the understanding of the depth and personal meaning of learning.

The same situation is true for personally meaningful learning, which is often or always practiced by 227 teachers, but never or rarely by 37.

According to Hattie (2012), a reflection on experience (goal of action, course of work, assessment criteria, achievement), formative assessment (emphasis on the session) and metacognitive strategies (Hattie, 2012) are the most important components of the learning process, and if the teacher implements the learning process according to them the process will become a driver in promoting cultural awareness.

3. Context of learning

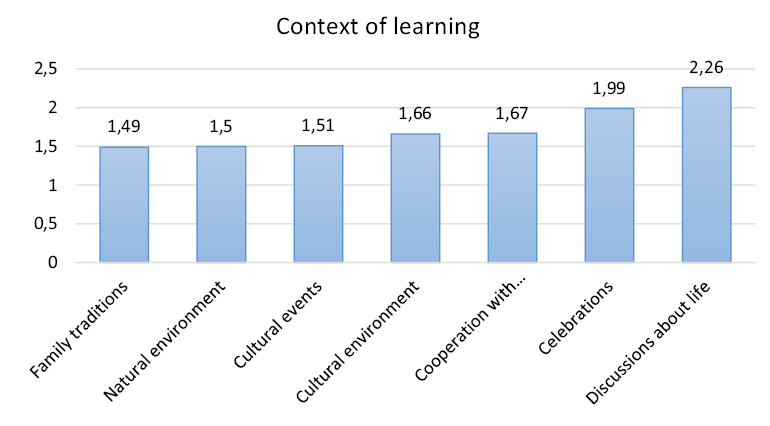

The third part of the survey contained statements concerning the involvement of the events and processes of actual life in the process of learning.

The data shows that involvement of actual socio-cultural contexts is non-systematic in teachers’ practices (Figure 4). Approximately 50% of respondents consider life contexts to be an important resource for learning; just as many do not attach importance to context-based learning (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Teachers experiences of adapting learning to actual life situations

The majority – 235 respondents – note the importance of discussions in the learning process, 178 respondents associate their studies with celebrations, and 204 note that they often and regularly implement cooperation with parents. At the same time, 138 teachers pay little or no attention to the exploration of students’ family traditions in the learning process. This contradicts the notion that learning about the world’s cultural diversity begins with an understanding of the traditions of the immediate socio-cultural environment – the family (Rogoff, 2008).

Cognition of the natural and socio-cultural environment is also not a self-evident and widely implemented practice in primary education. Outdoor learning is regularly implemented by 42, often – by 75 respondents, studies of the local cultural environment are supported regularly by 105, often -by 45 teachers. Although learning in an authentic environment outside the school offers greater opportunities to combine conceptual thinking, and theoretical and experiential knowledge with sensory experience (Dālgrēns, Ščepanskis, 2007), it requires time and careful planning, as well as collaboration with colleagues, children, and parents. Perhaps it is a reason why teachers rarely choose to do it (147 – learning in a natural environment, 114 – in a socio-cultural environment), although the School Bag Project, initiated to promote access to culture in education, is available to support teachers. Most of the respondents rarely include attending cultural events in the learning process.

In response to open-ended questions, teachers say that there is a “shortage of time” which prevents exploring ideas outside the classroom and the ordinary curriculum (“I have to follow the textbook”, “there are no appropriate materials”).

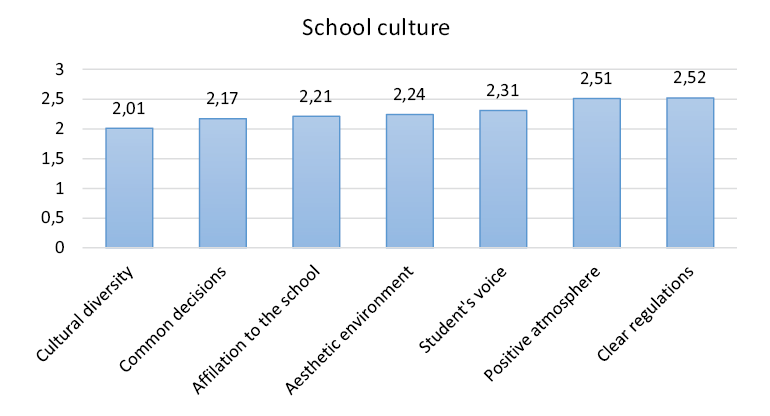

4. School culture

The fourth part of the survey investigated the teachers’ understanding of the building of school culture.

Figure 5. Teachers’ experiences in cultivating collaborative, sincere, and accepting relationships.

In Figure 5, we can see that in general, all variables related to the development of the school culture are at a high level. The highest ratings are for the creation of a positive atmosphere in the classroom and clarity of regulations. This means that the open and collaborative relationships necessary for cultural diversity and trust in the classroom seem to be one of the teachers’ priorities. However, cultural diversity is in the last place in teachers’ ratings as an important factor for the development of cultural awareness.

In open-ended questions, teachers focused on the other problems related to school culture. Overall, 57 respondents mentioned the lack of a multilateral relationship between teachers, school leaders, and parents. Comments regarding factors such as “lack of cooperation/ coordination with other colleagues”, “too little responsiveness from school leaders”, “resistance of parents”, “teachers’ fear of doing something wrong” indicate the lack of a positive atmosphere and common goals/understanding within the school community.

The second aspect that emerges from teachers’ statements can be interpreted in connection with their awareness of their personal responsibility. Many respondents reflect the “lack of experience” (30) and acknowledge their own competence – “it is easy for me” (42) – and opportunities to learn: “I am looking for information by myself”, “I contribute to lesson preparation” (12). However, in total, more than half of the respondents see the problem as being outside their personal competence or responsibility.

It follows from the above discussion and findings that if teachers and school communities do not implement the principles they teach to students in their own lives, then success cannot be expected.

Conclusions and Discussion

The statistical data showed that teachers are aware of the significance of personally meaningful learning for students and the importance of a positive atmosphere in classroom. Their experiences of integrating the cultural issues in all school subjects and connecting the learning with actual situations and socio-cultural contexts life are at a much lower level. A similar situation is with teachers’ experiences with the content of culture – they mostly interpret culture as belonging to art, rather than all human expression.

The comparison of quantitative and qualitative data revealed a difference between educators’ beliefs and knowledge – and their real practices:

• Teachers note the importance of active and self-directed learning, but common expressions that students are not motivated show that it is not implemented effectively in practice.

• Teachers recognise the need to foster the development of contextual learning, but do not dare to plan and implement the learning process independently and creatively.

• Teachers cultivate a positive atmosphere in the classroom, but do not feel responsible for creating one outside the classroom, in collaboration with colleagues and school management.

It can be argued that there is a gap between what teachers think they know and do to achieve a transformative learning process and their real competence to implement it in practice.

The practice of respondents can be interpreted a traditional transmissive approach to the promoting of students’ cultural understanding. Teacher educators face a challenge in upgrading the teacher education curriculum, professional development, and teaching aids to reduce the gap between theoretical principles of transformative learning and teachers’ beliefs and practices related to the promotion of general school students’ cultural understanding.

Possible solutions:

• To realise inter- and trans-disciplinary studies in teacher education by purposeful integration of cultural issues and discussions about contradictory values in all study courses, not only in arts, language, and social sciences.

• To promote the prospective teacher’s own cultural understanding through reflecting on personal experiences, involving the students in setting individual learning goals, as well as discussing the different meanings and cultural values that help the appreciation of the cultural context and the diversity of people’s experiences.

• To encourage the openness and creativity of future teachers by suggesting that they create and share with other students some original materials, like catalogues of lesson ideas or support materials for the organisation of primary school students’ personally meaningful learning, linking them with their life experiences and authentic life events.

• To cultivate a trustful, honest, straightforward, and respectful atmosphere in academia.

References

Banks, J. A., Cherry, A., & McGee, B. (2015). Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives, (9th ed.). London: Wiley.

Bennett, T., Grosberg, M., & Williams, R. (2005). New keywords: A revised vocabulary of culture and society. Oxford: Blackwell Pub.

Briška, I., Siliņa-Jasjukeviča, G., Kalēja-Gasparoviča, D. (2019) The Concept of Competence in the Context of Education Reform in Latvia. Society. Integration. Education: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. Volume II, May 24th -25th, 2019. 43-52 Retrieved October, 25, 2020, from: https://conferences.rta.lv/index.php/SIE/SIE2019/paper/view/2789

Briška, I., & Kalēja-Gasparoviča, D. (2020). Promoting of student’s cultural understanding in general education: Contradictions and solutions. Rural Environment. Education. Personality., 13, 236-242. Retrieved October, 20, 2020, from: https://llufb.llu.lv/conference/REEP/2020/Latvia_REEP_2020_proceedings_No13_online-236-242.pdf

Dālgrēns, Ū.L., & Ščepanskis, A. (2007). Brīvdabas pedagoģija. Mācīšanās no grāmatām un sensoprās pieredzes. [Outdoor pedagogy. Learning from books and sensory experiences]. Valmiera: Lapa.

Dewey, J. (1979). Art as experience. NewYork: A Paragon Book.

Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change (5th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. NewYork: Basic Books.

Grossberg, L. (2010). Cultural studies in the future tense. Durham: Duke University Press.

Griffin, C., Holford, J., & Jarvis, P. (2003). The theory & practice of learning. Kogan Page.

Griswold, W. (2012). Cultures and societies in a changing world. Pine Forge Press.

Halupa, C. P. (2016). Transformative curriculum design. http://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0978-3.ch021

Hattie, J. (2009) Visible learning: A synthesis of meta-analysis relating to achievement. Routledge.

Helds, J. (2006). Mācīšanās kā konstruktīvs un sistēmisks jēdziens [Learning as a constructive and systemic concept]. In I. Maslo (Ed.), Rakstu krājums No zināšanām uz kompetentu darbību [Collection of articles—From knowledge to competent action]. Rīga: LU akadēmiskais apgāds, 31-35.

Kron, F. W. (2004). Grundwissen didaktik. Ernst Reinhard Verlag.

McLeod, S. A. (2018). Questionnaire: definition, examples, design and types. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/questionnaires.html

MK Noteikumi par valsts pamatizglītības standartu un pamatizglītības programmu paraugiem No. 747 [Cabinet of Ministers Regulations on the National Standard for Basic Education and Models of Basic Education Programs No. 747]. (2018). Retrieved September, 29, 2019, from: https://likumi.lv/ta/ id/303768-noteikumi-par-valsts-pamatizglitibas-standartu-un-pamatizglitibas-programmu-paraugiem

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Siliņa-Jasjukeviča, G., & Briška, I. (2016). In-depth cultural studies in multicultural group. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 7, (pp. 139-148). Rēzekne: Rēzeknes Tehnoloģiju akadēmija.

Siliņa-Jasjukeviča, G., Briška, I. & Juškevičienė, A. (2019). Regional cultural understanding in teacher education in Latvia, Lithuania, Norway: Comparative case analysis. Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia, 430, 10-24. doi: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.43.1.

Siliņa-Jasjukeviča, G., & Briška, I. (2019). Reflection of pre-service teacher professional performance for promoting transdisciplinary learning in primary school education. ATEE Spring conference proceedings. Innovations, technologies and research in education, Rīga: University of Latvia. p.301-312. DOI. https://doi.org/10.22364/atee.2019.itre ISBN 978-9934-18-482-6

Tiļļa, I. (2005). Sociālkultūras mācīšanās organizācijas sistēma. [Socio-cultural learning organization system]. Rīga: Raka.