Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2022, vol. 48, pp. 8–25 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2022.48.1

Textual Analysis of Quality Assurance Development in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Higher Education Sector

Aleksandra Figurek

Faculty of Agriculture, University of Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina

aleksandra.figurek@agro.unibl.org

Giuseppe T. Cirella*

Faculty of Economics, University of Gdansk, Sopot, Poland

gt.cirella@ug.edu.pl

Anatoliy G. Goncharuk

Department of Management, International Humanitarian University, Ukraine

agg@ua.fm

Enoch T. Iortyom

Department of Geography, Environment and Sustainability Studies, Ernest Bai Koroma, University of Science and Technology, Sierra Leone

etiortyomenoch@ebkustsl.edu.sl

Una Vaskovic

Hochschule Macromedia, University of Applied Sciences, Munich, Germany

vaskovic1997@gmail.com

Solomon T. Abebe

Polo Centre of Sustainability, Imperia, Italy

solomtu6@gmail.com

Abstract. Education is the bedrock of any nation. It is essential for individual and societal growth and development. This study investigates the role of quality assurance in achieving the expected outcome of education in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education sector. A textual analysis is used to examine the National Qualification Framework. The study is based on a documented review and descriptive analysis of student enrollment and programs of studies. The textual analysis is largely qualitative in nature. Unlike the global trend, it can be seen that student enrollment is on the decline in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was found that quality assurance is an indispensable tool for strengthening the higher education sector and for achieving the desired change and outcomes that education offers. It was also found that study programs and curricula are pivotal for teaching and learning processes, and that a unified qualification framework is essential for achieving set objectives of education at all levels. The study recommended that sound quality assurance systems as well as an appropriate structure for monitoring and accreditation be put in place and be judiciously followed in order to achieve the desired outcomes in conjunction with the set objectives of higher education in the country. Moreover, certain pressures (i.e., democratic, economic, and systemic) and obstacles are looked at that show signs of epistemological, political, and institutional barriers that Bosnia and Herzegovina faces as a developing country Europeanizing its system of education.

Keywords: National Qualification Framework; education performance; university barriers; education system; Bosnia and Herzegovina

Kokybės užtikrinimo plėtra Bosnijos ir Hercegovinos aukštojo mokslo sektoriuje: teksto analizė

Santrauka. Švietimas yra kiekvienos tautos pagrindas, būtinas asmens ir visuomenės augimui bei vystymuisi. Šiame tyrime analizuojamas kokybės užtikrinimo vaidmuo siekiant numatomų Bosnijos ir Hercegovinos aukštojo mokslo sektoriaus rezultatų. Nacionalinė kvalifikacijų sistema nagrinėjama pasitelkiant teksto analizės metodą – tyrimas grindžiamas dokumentuota, daugiausia kokybine studentų priėmimo ir studijų programų apžvalga bei aprašomąja analize. Tyrimas atskleidė, kad skirtingai nuo pasaulinių tendencijų, Bosnijoje ir Hercegovinoje studentų skaičius mažėja. Kokybės užtikrinimas yra nepakeičiama priemonė stiprinant aukštojo mokslo sektorių, taip pat norint pasiekti švietimo inicijuojamus pokyčius ir rezultatus. Atskleista ir tai, kad studijų programos ir ugdymo turinys turi lemiamą reikšmę mokymo ir mokymosi procesams, o unifikuota kvalifikacijų sistema yra būtina siekiant užsibrėžtų švietimo tikslų visais lygiais. Tyrime rekomenduojama įdiegti patikimas kokybės užtikrinimo sistemas, atitinkamą stebėsenos ir akreditavimo struktūrą bei jų apgalvotai laikytis, kad šalyje būtų pasiekti keliamus aukštojo mokslo tikslus atitinkantys rezultatai. Be to, tyrime aptariami labai svarbūs ir nuodugniai išanalizuoti lemiami veiksniai (demokratiniai, ekonominiai ir sisteminiai) ir trikdžiai – jie nusako epistemologinių, politinių ir institucinių kliūčių požymius Bosnijoje ir Hercegovinoje, besivystančioje šalyje, kuri yra švietimo sistemos europinimo pavyzdys.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: Nacionalinė kvalifikacijų sistema, švietimo rezultatai, kliūtys universitetams, švietimo sistema, Bosnija ir Hercegovina.

__________

* Corresponding author.

Received: 21/05/2021. Accepted: 10/04/2022

Copyright © Aleksandra Figurek, Giuseppe T. Cirella, Anatoliy G. Goncharuk, Enoch T. Iortyom, Una Vaskovic, and Solomon T. Abebe

Introduction

As popularly alluded to, education is the bedrock of any nation. It is essential for individual and societal growth and development. Admittedly, the World Education Forum (2015) and Glewwe et al. (2016) have averred that education generally plays a critical role in driving economic development the world over. In recognizing this, the United Nations Children’s Fund declared a benchmark of 26% of total public expenditure for education (UNICEF, 2017). To this effect, most countries also attribute a high percentage of their budget to education. Yet, regardless of fiscal investment, the quality of education is still a major determinant of the expected impact education can create. As a result, globally, the demand for education has consistently been on the rise (UNESCO, 2020). As such, the global projection by 2025 is that the demand for higher education should reach a staggering 263 million students (Karaim, 2011). The demand for quality education simultaneously increases with the growing demand of quality assurance for international universities (Hou, 2012).

The motivating factors that contribute to quality assurance in higher education are the underlying premise of this case report. Based on a study by Bobby (2014), these factors should support and boost the development of higher education institutions, which, in turn, will promote educational achievement. The quality of an education system, hence, depends on its capacity to equip people with the skills and competences needed for their personal development, the fulfillment of their function in the society, as well as for ensuring their integration and transition into the labor market after they graduate. This study is a textual analysis and overview of how school quality assurance policies, procedures, and practices currently work in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education sector. It examines the processes used to advance measures that will enhance the quality of education, i.e., the current society-wide system design based on social cohesion, equity, employment, innovation, and competitiveness. It is against this background that exploratory quality assurance practices and mechanisms can be implemented to ensure the quality of higher education and effective information and knowledge delivery. This paper is structured as follows: a literature review of the state of the art of higher education development, an explanation of the methodology used in the study, a summary of the results, and a discussion and conclusion on the modernization steps of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education sector.

Literature review

The historical structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher academic system dates back to the former country of Yugoslavia, wherein four distinct stages can be singled out: first, between 1945 and 1954, a period of socio-ideological and instructional transformation of higher education, with an emphasis on state building (Ivic, 1992; Uvalic-Trumbic, 1990). Second, between 1954 and 1982, a period of inner higher education transformation and development centralized around a close compliance with Marxist ideology was formally instituted (Ivic, 1992; Nellie, 1980; Wright, 2021). Third, from 1982 to 1989, a brief period of logical and reasonable qualitative higher education reform was introduced with an emphasis on economic progress (Samolovcev, 1989). Fourth, from 1990 to 1992, a period marked by a brief but sharp move toward hypernationalism, as well as attempts to rescue the state and, eventually, the state’s disintegration (Weber, 2007). The university was viewed as a place where future leaders would be raised, and scientific study would aid in the development of a socialist society founded on evidence and logic (Ivic, 1992; McQuay, 2014; Samolovcev, 1989). Higher educational institutions in Yugoslavia supplied the nation with a plethora of highly trained specialists, eager to accelerate the cultural and economic developments necessary for implementing a system of socialism. In Yugoslavia, higher education peaked in 1980 and, subsequently, rapidly deteriorated along with the rest of the country (Kunitz, 2004; Yarashevich & Karneyeva, 2013). The fundamental reason behind it was the downfall of the economy, in part from its Long-Term Framework for Yugoslav Economic Recovery, formed in 1983, that called for benefit cuts in all areas – including higher education (Baketa, 2014; Heuvel & Siccama, 1992).

After the breakup of the Yugoslav federation in 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher academic system, as noted by Kovácováa and Vackováa (2015), persistently changed and implemented quality in higher education via several dependent factors, including specialization and methodical training; collaboration between lecturer and students; and provision of the necessary learning, material, moral, and psychological conditions on par with other European countries (Eder, 2014; Magill, 2010; Rushaj, 2015; Savić & Kresoja, 2016). A university lecturer, nowadays, is a crucial component of educational quality assurance and should be familiar with new trends in their field, pay attention to quality content preparation and educational organization, keep up with news, professional and educational publications, and legislative developments in the discipline, improve one’s own professional qualification and personal development, expand the didactic and pedagogical profile of competencies, attend conferences and seminars as well as international workshops, connect with their students, and collaborate with institutions and organizations. The concept of educational quality itself is multidimensional and therefore difficult to define (De Ketele, 2008). The use of the term quality assurance has changed over time to reflect the society’s growing interest in evaluating the performance of higher education institutions; however, scholars continue to define quality assurance in higher education in different ways (Williams, 2016). One category of scholars choose to give a broad definition that targets a single central goal or outcome (Bogue, 1998; Harvey & Green, 2006). On the other hand, there are those that categorize quality assurance through the designation of specific indicators and desired inputs and outputs (Barker, 2002; Lagrosen, Seyyed-Hashemi, & Leitner, 2004; Scott, 2008; Tam, 2010; Vlăsceanu, Grünberg, & Pârlea, 2004).

Currently, the suggested use, comprehensively, refers to all of the policies, procedures, and activities that are used to validate and improve the performance of higher education institutions (Harvey, 2005); in other words, quality is defined through a stakeholder-driven perspective (Bobby, 2014; Harvey, 2005). An example of a successfully implemented use is the Scottish Credit and Qualification Framework, which introduced a robust National Qualifications Framework (NQF) based on a consistent conceptual model, flexible architecture guidelines, and voluntary, partnership-based education. In Europe, the execution of NQFs are often accredited as a baseline for framing education programs continent-wide (Gallacher, Toman, Caldwell, Raffe, & Edwards, 2005; Young, Young, & Michael., 2005). At length, a comprehensive NQF introduces a standardized language and common curriculum across different sectors of the education and coaching systems. Area unit tools create a method that is clear and coherent for coordinating framework elements and constructing pathways between them. At present, NQFs are broadly utilized throughout the European Union and a number of other countries, like Australia and New Zealand (Wheelahan, 2011). These countries demonstrate that, over time, problems can accumulate and require reform; however, once a framework is in situ, any restructuring can be problematic, especially with standardized language requirements and the need to educate students in a language not spoken in the community or at home (Gallacher et al., 2005). In short, while quality is the desired result, quality assurance is the process through which systems try to ensure that quality is achieved and continuously improved. As with many European countries, English has become a common teaching language, mixed in with programs that also instruct in the native language. In the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, this is a common practice in its higher learning institutions. Nowadays, the country’s higher educational quality assurance is on track to closely aligning itself with European Union standards and norms (Brankovic & Brankovic, 2013; Constantinides & Stagno, 2011; Figurek, Goncharuk, Shynkarenko, & Kovalenko, 2019). This paper showcases Bosnia and Herzegovina’s educational quality assurance by utilizing textual analysis methods similar to those employed by Ilinska et al. (2016), Cunningham-Nelson et al. (2018), and Zhang and Law (2013). A textual analysis framework is developed in line with Ryan’s study (2011), which contributes to the knowledge base of textual analysis research.

Methods

Bosnia and Herzegovina is situated at the central part of the Balkan Peninsula and spans a territory of 51,209.2 km2. The country shares borders with Croatia to the north, west, and southwest, with Serbia to the east, and with Montenegro to the southeast. Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of two administrative entities, namely the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) (i.e., divided into ten cantons that further split into 79 municipalities) and the Republic of Srpska (RS) (i.e., divided into regions and further into 62 municipalities), and the Brčko District of Bosnia and Herzegovina (BDBiH) (i.e., a separate district under the government of the state). Economy-wise, the gross domestic product of Bosnia and Herzegovina as of 2019 was 2.8%. In terms of higher education, it has both public and private institutions (Kostić, Jovanović, & Letica, 2017). The public higher education institutions are established in accordance with the following laws: the Framework Law on Higher Education, the Law on Higher Education for the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Law on Higher Education for the Republic of Srpska (Joint Declaration of the European Ministers of Education, 1999; Kostić et al., 2017; Rastoder, Nurovic, Smajic, & Mekic, 2015).

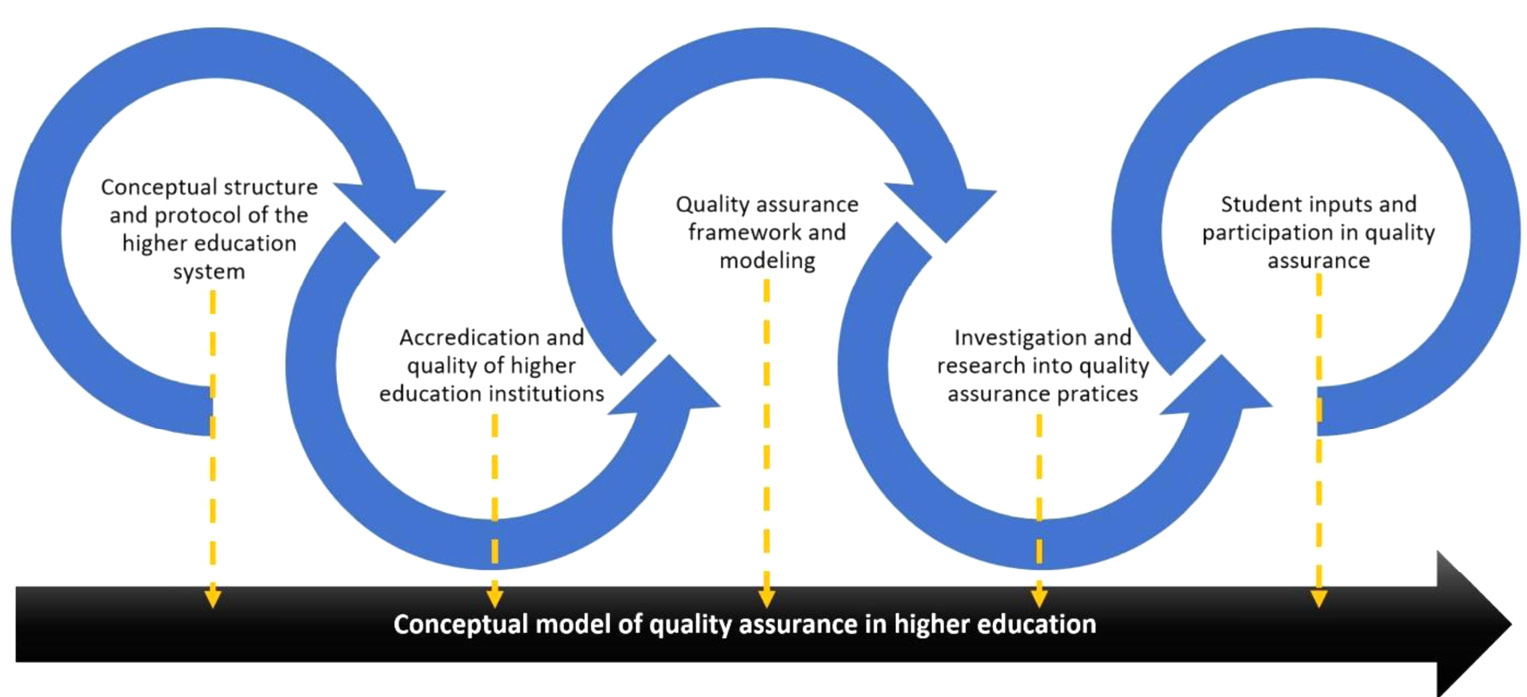

The study employed a textual analytical approach, which closely followed Zhang and Law’s (2013) online journal review methodology. Further textual methods included comparing documents for repetitive information and interpreting the text from a historical and developmental lens (Fürsich, 2009; Lacity & Janson, 2015; Zhang & Law, 2013). For the study, this involved reviewing existing literature upon which inferences were made regarding the quality assurance of higher education in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The focus of the study was narrowed down to 59 research papers published in journals indexed in the Web of Science’s Social Sciences Citation Index and six reports from European governing bodies (Bartlett, Branković, & Oruč, 2016; Council of Europe & European Commission, 2005, 2007, 2017, European Commission, 2015, 2017). Secondary data on student enrollment in higher education were also sourced from the statistical offices and agencies of FBiH, RS, and BDBiH, and used for the descriptive analysis (Bartlett et al., 2016). The conceptual model of quality assurance in higher education parallels Ryan’s (2011) work, in which most European countries are currently framed (Figure 1). The textual analysis method was used to describe, interpret, and understand texts as well as sort out information pertaining to the state of the art of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education institution quality assurance policies, procedures, and practices.

The methods used to conduct the textual analysis focused on connections between the broader social, political, and cultural context within the country. It examined the design elements in the higher education sector, the target population, and the relationship with other concurrent systems. The timeframe of the study is from 2015 to 2020. The analysis is qualitative in nature – with findings presented as recommendations and ways for the further development of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education sector.

Figure 1. Framework of conceptual model of quality assurance in higher education, adapted from Ryan (2011).

Results

Background to Europeanizing higher education in Bosnia and Herzegovina

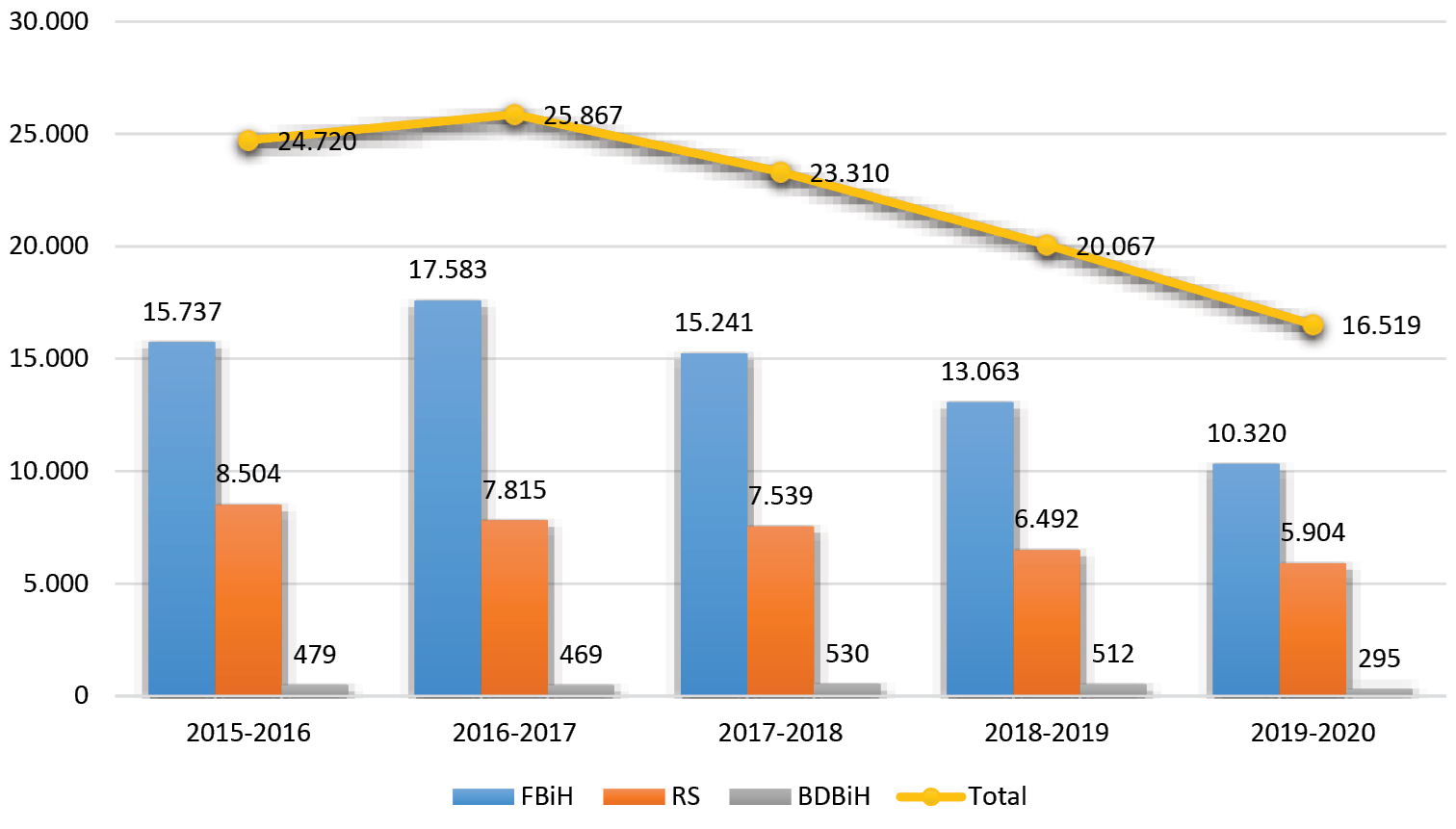

In 2005, the European Network for Quality Assurance in Higher Education made the first step in setting up the process through which systems would try to ensure that quality is achieved and continuously improved (Kostić et al., 2017). This was done by establishing quality-related values, expectations, good practices, and assurances by institutions (European Commission, 2018). Contemporaneously, standards and guidelines were directed in a way that achievements were equivalent to implementing the Bologna Declaration of 1999. At present, the Declaration is supported by 29 European governments and complements higher education reform by setting up a quasi-European Higher Education Area via national systems (Kostić et al., 2017). In this structure, the European Commission is given the umbrella-role of supporting reforms in curricular development, degree structures, credit transfer, and quality assurance as agreed upon in the Ministerial Conference Bergen of 2005. Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted a new state level reform titled the Framework Law on Higher Education after the signing the Bologna Declaration in 2007 (European Commission, 2018; Kostić et al., 2017). At this point, the country introduced three cycles of studies to harmonize with the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS), i.e., Bachelor studies with 180 and 240 ECTS for three- and four-year programs, Master studies with 60 and 120 ECTS, and Doctor of Philosophy studies with 180 ECTS. As a result, at the European level, the social aspect has been noticeable, since one of the priorities of the Bologna Declaration is to provide European governments with the tools to better attend to the social circumstances of students in their respected countries (European Commission, 2018; Ferencz, 2015). In the last five years, this has reflected a general trend across Europe, wherein an increase in student enrollment has been recorded (Calderon, 2018; Eurostat, 2020; Klaveren, Kooiman, Cornelisz, & Meeter, 2018). However, in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, this has not been the case (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Total number of students enrolled in the first year of higher education in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2015–2020. Source: statistical offices and agencies from FBiH, RS, and BDBiH from 2020.

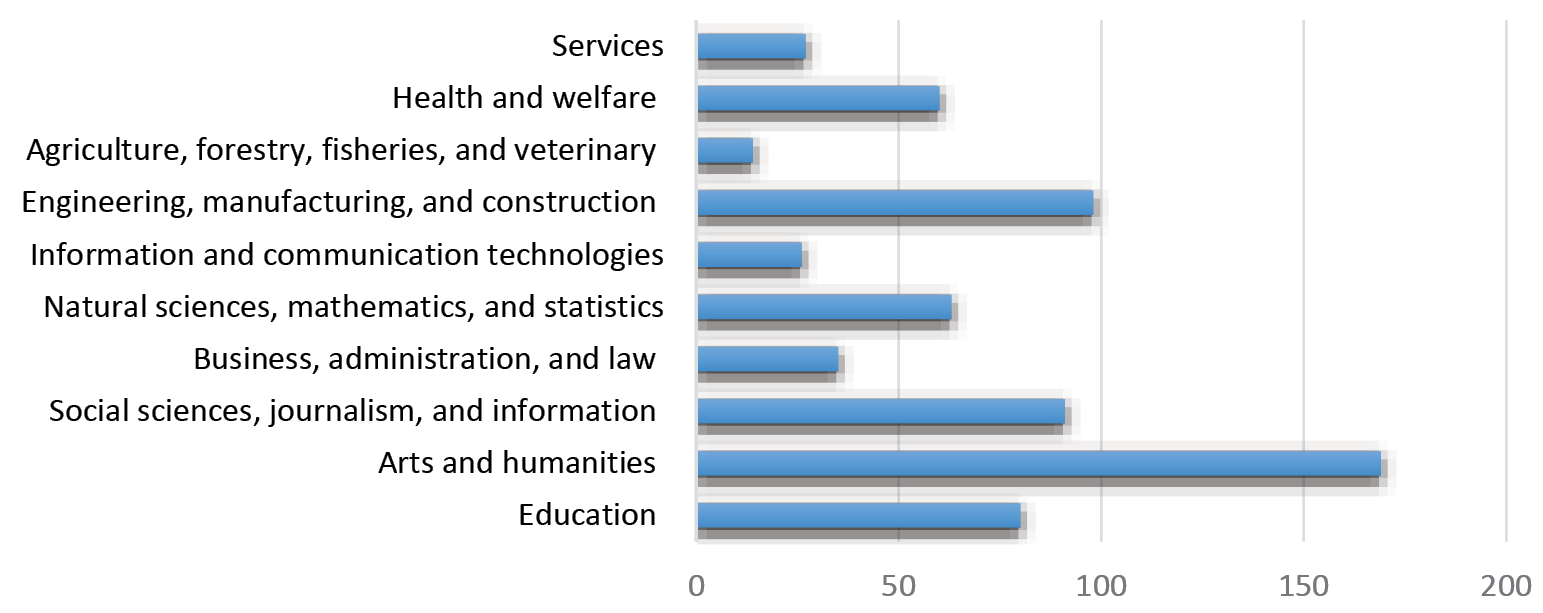

The total number of students enrolled in the first year of higher education between 2015 and 2020 shows an initial increment of 4.64% between the academic years of 2015–2016 and 2016–2017; however, a consistent decline in the following three academic years is present. In the 2017–2018 academic year, for instance, the number of students enrolled decreased by 10% compared to the previous academic year, followed by 14% in 2018–2019 and 18% in 2019–2020. In the last three years, the number of students enrolled for the first time in their first year of study dropped by 29%, i.e., from 23,310 to 16,519. In other words, while global demand for higher education was on the increase and was projected to reach 263 million students (i.e., about a 163 million increase in the next 25 years), data shows that student enrollment is on the decline in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Agency of Herzegovina, 2019; BiH Statistics, 2018). A closer examination of the data, at the field of study level, reveals the arts and humanities as higher than other study programs on a national level (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Number of available study programs by broad field of study in Bosnia and Herzegovina for the academic year 2019–2020. Source: provision database in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 2020.

Quality assurance policy in Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Proposed guidelines and objectives

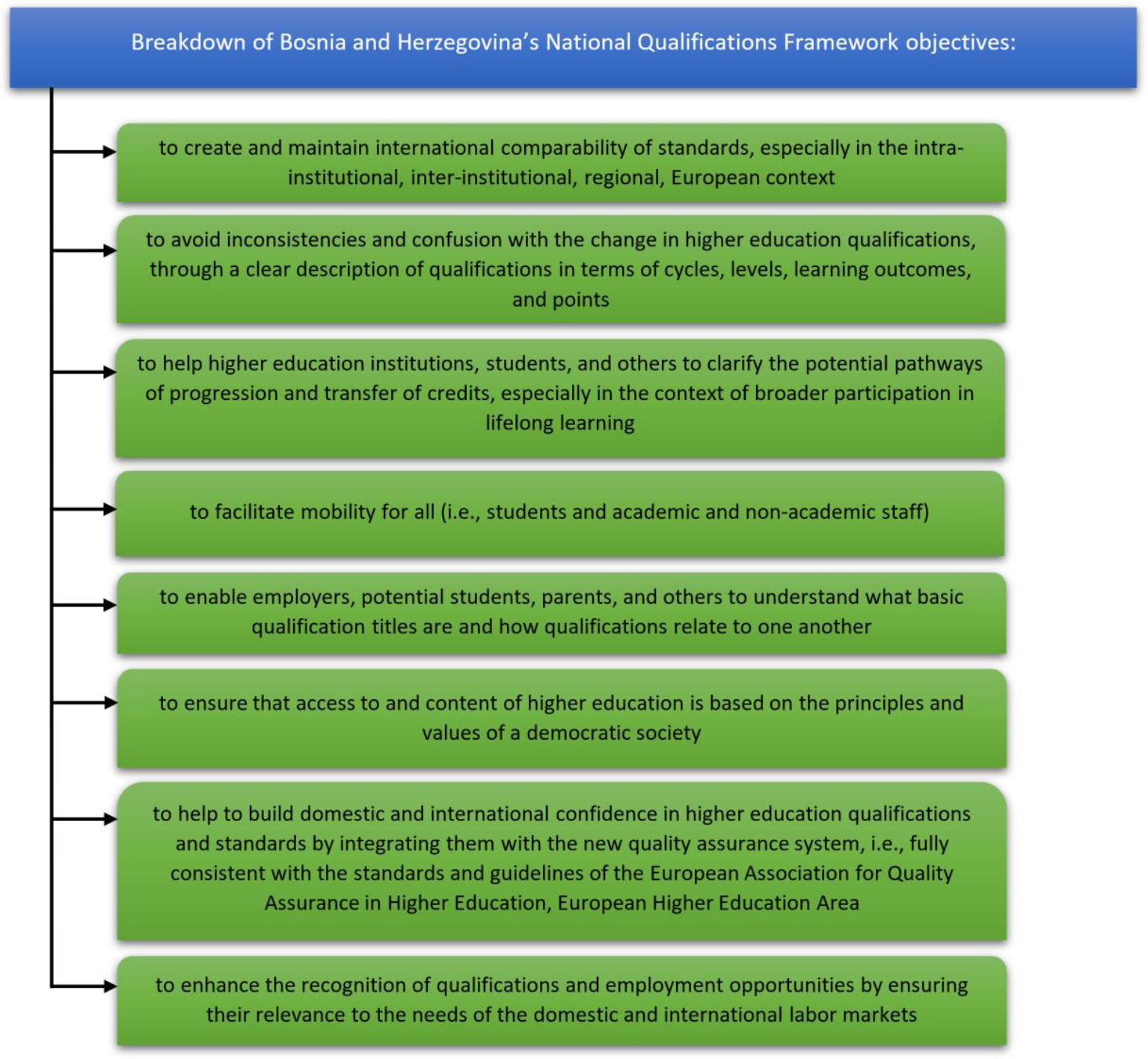

To better understand the level of quality assurance in higher education in Bosnia and Herzegovina, its NQF was framed in such a way that the Bologna Declaration and the Framework Law on Higher Education were addressed (Figure 4). In summary, the objectives have been to achieve guidelines that illustrate a strong policy direction encouraging an upward enrollment trend in the coming decade. The guidelines commit the country to implementing reformed terms of quality assurance targets intent on progressively advancing the higher education system. In conjunction with the Joint Council of Europe and the European Commission, these guidelines were cooperatively approved to strengthen the higher education sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as move it towards a Eurocentric structure. The most basic and important elements of the NQF consist of creating a framework for higher education qualifications, developing a work plan for introducing modern procedures and structures for recognition of qualifications, and establishing broadened standards and guidelines for quality assurance in higher education institutions.

Figure 4. Objectives of the >Bosnia and Herzegovina National Qualifications Framework. Source: elaborated by the authors according to the data of the Agency for Development of Higher Education and Quality Assurance of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2020).

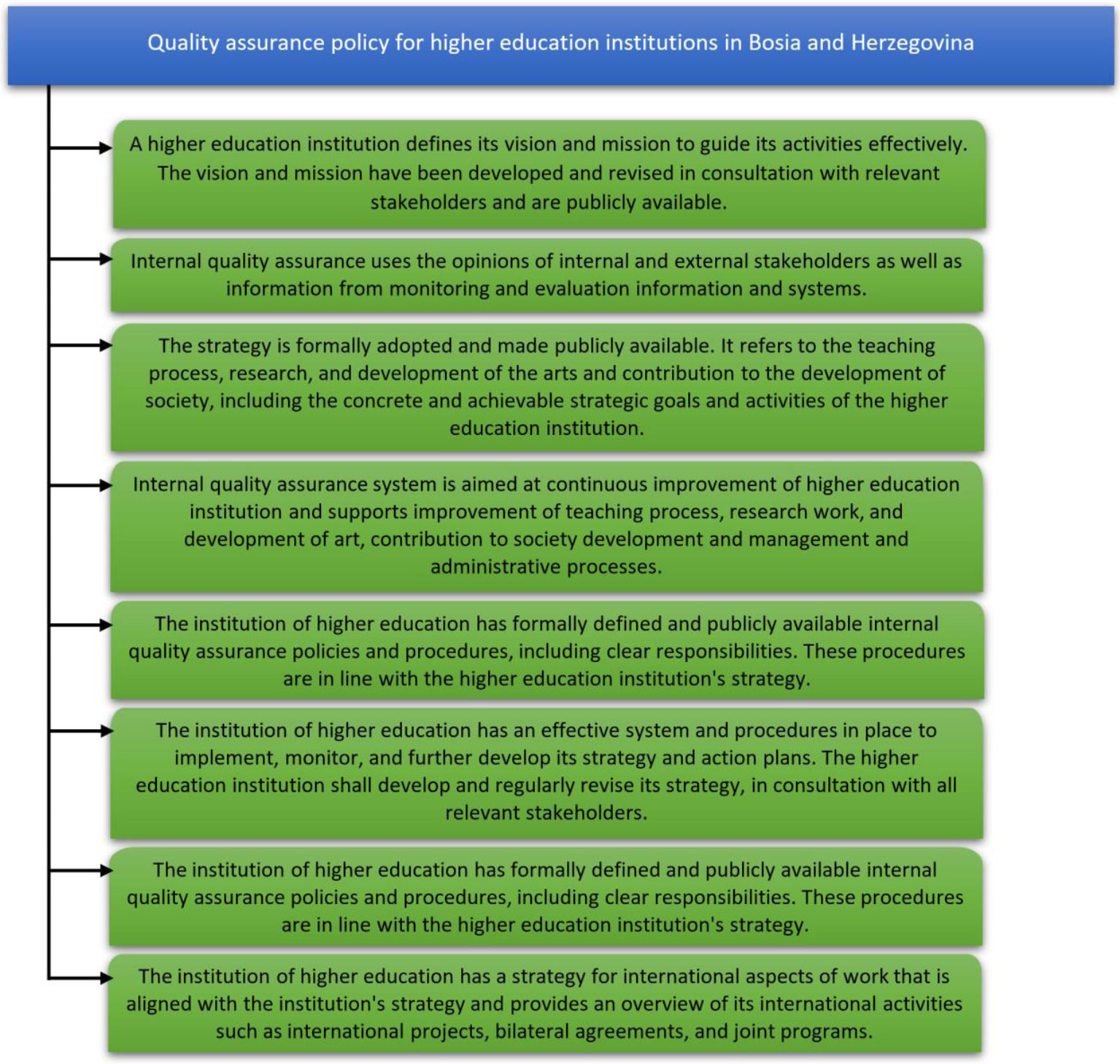

The proposed guidelines for quality assurance policy in Bosnia and Herzegovina and its main objectives are expounded as an important step in quality assurance policy for the country. The quality assurance policies for higher education institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina are presented in Figure 5. EACEA (2015) and Brennan and Shah (2000) point out that the advancement of long-term objectives for a quality assurance system should include:

• supporting equal social opportunities for all learners;

• supporting the mobility of students, graduates, and citizens nationally and internationally;

• encouraging research and knowledge transfer;

• responding to stakeholder and user needs in higher education;

• guaranteeing comparability with the European Union across a wide range of areas (e.g., student learning support network and graduates and employer feedback systems); and

• improving the public accountability of higher education to the wider society.

Figure 5. Quality assurance policy of higher education institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Source: elaborated by the authors according to the data of the Agency for Development of Higher Education and Quality Assurance of Bosnia and Herzegovina (2020).

The importance of maintaining quality assurance is to ensure that the expected outcome of education programs is achievable. In this regard, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s internal guidelines may not be sufficient to maintain and achieve this desired target. This brings to light the need for an external quality assurance strategy that can monitor and direct the system towards achieving its set objectives. Stensaker (2011) noted that external quality assurance is of immense importance, stressing that the accreditation and accreditation systems of European countries are dominated by evaluation methods in-line with the European Higher Education Area and in conjunction with trends from the American system. Taking this into account, accreditation is rapidly becoming “one of the most popular methods for external quality assurance worldwide” (Stensaker, 2011). For Bosnia and Herzegovina, it falls into the category of a newly emerging system of accreditation schemes, which has changed immensely over the two decades. This change parallels much of the early higher education reform in Central and Eastern Europe (Enders & Westerheijden, 2017; Gornitzka & Stensaker, 2014; Rozsnyai, 2003; Smidt, 2015; Temple & Billing, 2010) that currently lags in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Accreditation and systemization of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education

According to Ryan (2011), the Council for Higher Education Accreditation advanced three important considerations that influence the quality assurance trends in international higher education. First, an increment in competitiveness and the rigorousness of quality assurance. Second, quality assurance that has been recognized regionally. Third, a demand for an international quality assurance framework. However, studies in both developing and developed countries have outlined a challenge in the accreditation process – manipulation and abuse by the local accrediting agencies (Alderman & Brown, 2005; Blackmur, 2007; Goodlad, 1990). In line with these considerations, Bosnia and Herzegovina utilizes two sets of criteria for conducting accreditation. First, the criteria for accreditation of higher education institutions and, second, the criteria for accreditation of the study programs via cycles I and II (Glewwe et al., 2016). The criteria for accreditation of both higher education institutions and study programs in Bosnia and Herzegovina expand its guidelines for internationalization by encouraging and supporting continuous improvement in the quality and standards for the provision of higher education programs; guaranteeing that clear and accurate information is made publicly available about the quality and standards of higher education and training provision; and placing the best international practices of evaluation and review of higher education and training as part of its regular monitoring process (European Commission, 2007). Moreover, on the importance of external quality assurance, four key forms, i.e., structures, are identified from Kis (2005), Stensaker (2011), Palmer (2013), and Lange and Singh (2013): accreditation, audit, assessment, and licensing. These key forms make up a four-step review model that is recommended as a viable approach for systemizing Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education system. The steps include:

1. self-review report – submitted by the institution under review in order to provide its own analytical assessment;

2. external review team – encompassing three to five persons of high academic standing and repute, competent to make national and international comparisons on the quality of teaching and research and the provision of other services at the university level;

3. review team – experts visiting the institution to confirm the self-review report; and

4. review team evaluation report – presenting the report along with the conclusions and recommendations, which must be made publicly available, in a timely manner.

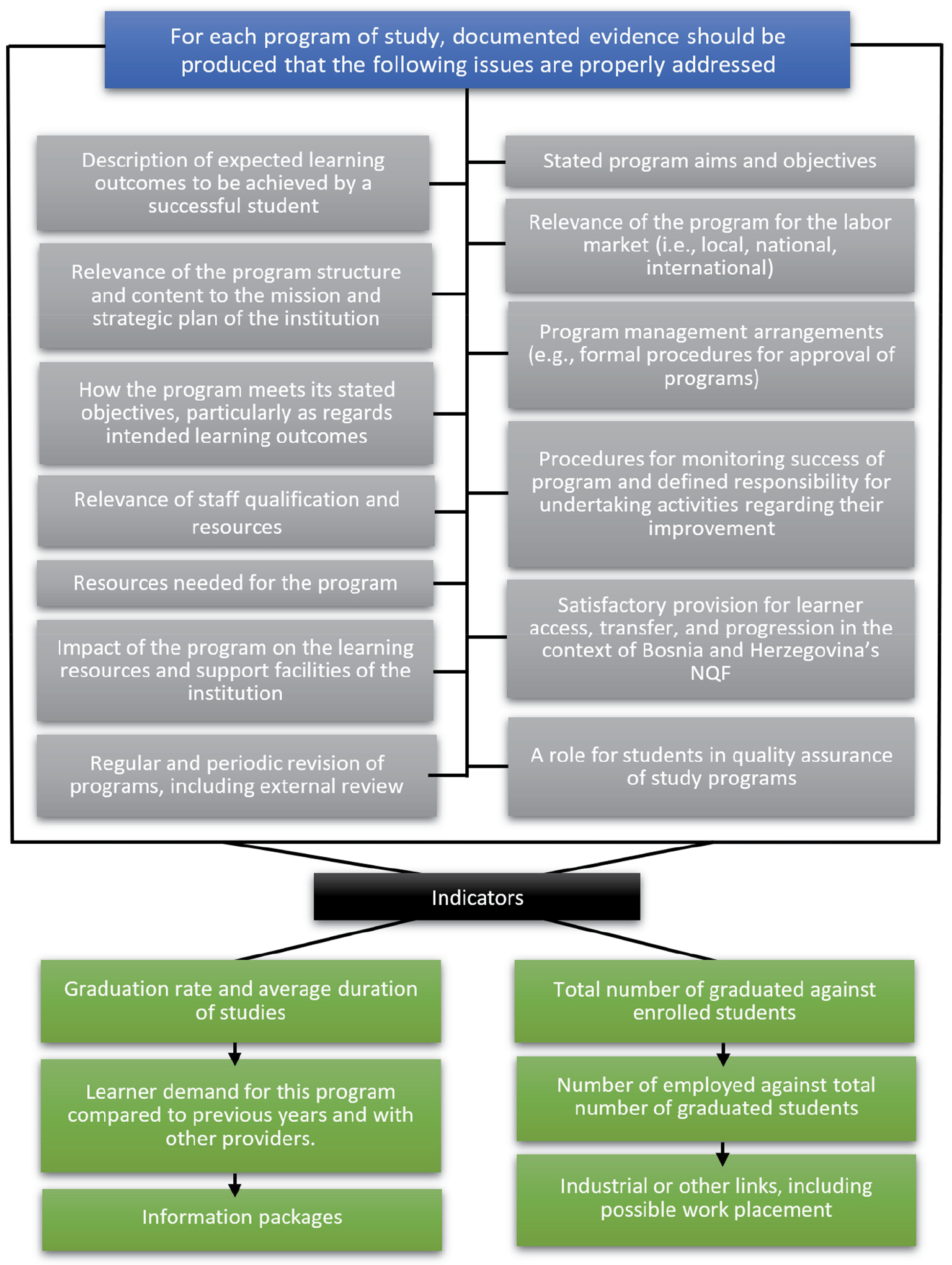

Indicators can be performance, as noted by Suryadi (2007), as well as other qualitatively assessed indicators (according to Chalmers, 2008) that can valorize the implementation of study programs and protocols for their implementation (Figure 6). This is consistent with the use of the four-step review model, i.e., by reporting on self-evaluation, the external review process team, and a repetitive (and consistent) process of updating expert opinion on quality assurance development. This will include training of experts, program development, and documentation on accreditation design, either planned or realized, e.g., via the use of international experts and the participation of students. Study program quality assurance policy has defined the following, i.e., next-level rules:

• higher education institutions have an approved and publicly available policy of internal security of the quality of study programs as well as their strategic management;

• the policy of ensuring the quality of study programs is aimed at research work, learning and teaching, mobility, and internationalization on study programs, as well as preventing plagiarism of lecturers’ work and students’ final theses on all study cycles; and

• the policy supports the development of a quality culture in which all internal participants contribute to the quality of study programs, and defines the way in which external participants are involved.

Figure 6. Key elements of the study programs and their indicators.

Source: elaborated by the authors.

Discussion and conclusion

Deduced from the textual analysis are two factors: (1) the need for higher education institutions to focus on internal quality assurance (i.e., with established criteria) in the work processes, especially in the quality of the study programs; and (2) the development of key elements to structure an accredited and systemized review process to best develop the higher education system. The methods used to conduct the textual analysis indicated connectivity between the broader social, political, and cultural context within Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher educational sector. In light of the data’s timeframe, i.e., from 2015 to 2020, there was some lack of information in regard to socioeconomic relationships, which, unfortunately, could not be verified via government websites, since a number of them were not up-to-date, or other government literature. However, after further researching several local government agencies as well as directly contacting personnel in some of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s higher education sector, it was identified that the collected data from the textual analysis did parallel the broader consensus in terms of NQF development. The qualitative, face-to-face dialogues should be considered suggestive at best, since they were informally conducted without a specific data collection objective. Nonetheless, from the literature and from the numerous qualitative informal interviews throughout the country’s universities as well as from living within the country, it can be inferred that there is a need for students to be encouraged to thoroughly and critically study curricula that does not view education solely as a pathway to secure work, but as something that contributes to improving their lives and society. Further, it should be inconclusively noted that students were not convinced that after acquiring a university degree a secure, professional job would be waiting for them. The findings also point towards a possible correlation in the population distribution of young people in Bosnia and Herzegovina that have migrated outside the country and have not returned. According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, for the age group of 15 to 30 (i.e., categorized as young people), there are currently 777,000 in the country (i.e., down by 315,000 from 1,091,775 in 1991). From the 2016 census data, only 95,048 (i.e., 13.15%) had a university degree and 58.33% had completed secondary education (Agency of Herzegovina, 2019). According to the World Bank (2018), high levels of unemployment are associated with the youth (i.e., ages 15–24), while emigration of people in this particular age bracket is high. As such, decision-makers in Bosnia and Herzegovina should consider this correlative result when reviewing baseline education data. This correlates with research conducted by Goncharuk and Cirella (2022), which shows that higher education institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina do not offer a high enough level of creativity for academicians needed to excel within the profession. This is especially important because lecturers in the country regularly abandon their workplaces in search of work in more prosperous Western countries (Goncharuk & Cirella, 2022).

As a result, the Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina decided to adopt the Baseline of Qualifications Framework on March 24, 2011, which established the process of building its NQF at all levels of education and harmonizing it with the European Qualification Framework (Turčilo, 2019). This methodological step is aimed at developing provisional occupational standards, qualifications, knowledge, and education based on learning outcomes. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s NQF organizes its higher education institutions as either universities or professional colleges, with private and public entities in both. Horizontal and vertical mobility through the education system and training in and out of the country is also established in accordance with the Bologna Declaration. That is, its institutions continue to work on quality assurance policies and practices needed to develop the higher education sector and build toward inclusion in the European Higher Education Area. As such, the need for systemized assurance quality procedures should incorporate academic, governance, and administrative areas as crucial modernization and reform components of the higher education sector.

It can be found from this study that quality assurance is an indispensable strategy for strengthening the higher education sector of Bosnia and Herzegovina and for achieving the desired change and, eventually, the outcomes of its education sector. Since study programs and curricula are pivotal for teaching and learning processes and are a basis by which knowledge is transferred to the younger generation, it should be assumed that a unified qualifications framework is essential for achieving the set objectives of education at all levels. It can, therefore, be recommended that sound quality assurance systems be put in place and be judiciously followed. They should be adequate and appropriate structured for time-to-time monitoring, accreditation, and systemization. This will guarantee the achievement of desired outcomes and set objectives of higher education institutions without deviations. In addition, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s NQF should be based on the country’s characteristics and the particularities of its educational sector objectives. These objectives are inclusive to Europeanizing the education system and facilitating mobility for all. Moreover, the quality assurance policy of higher education institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as the key elements of the study programs and their indicators, in terms of developing a viable approach to systemizing higher education, should be prioritized. As with all case research, it is necessary to take into account the pressures (i.e., democratic, economic, and systemic) and barriers in relation to the epistemological, political, and institutional barriers of a country when decision-making is demanded. In terms of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s education sector, the authors are optimistic that this baseline textual analysis of higher education will assist in producing interest and commitment on the part of academicians and policymakers. Future research in quality assurance in Bosnia and Herzegovina should consider the permanent landscape of higher education in the country and move away from control-type roles to roles highlighting quality enhancement and diversity.

References

Agency of Herzegovina. (2019). Analysis of Student Enrollment for the First Time in the First Year of Study. Sarajevo: Higher Education Institutions.

Alderman, G., & Brown, R. (2005). Can quality assurance survive the market? accreditation and audit at the crossroads. Higher Education Quarterly, 59(4), 313–328. http://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-2273.2005.00300.X

Baketa, N. (2014). Non-integrated Universities and Long-standing Problems The Universities of Zagreb and Belgrade in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Today. International Review of Social Research, 4(2), 111–124. http://doi.org/10.1515/IRSR-2014-0015

Barker, K. (2002). Canadian Recommended E-learning Guidelines. Vancouver: FuturEdCanadian Association for Community Education and Office of Learning Technologies, HRDC. Retrieved from http://www.nald.ca/cacenet.htm

Bartlett, W., Branković, N., & Oruč, N. (2016). From University to Employment: Higher Education Provision and Labour Market Needs in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Brussels: European Union.

BiH Statistics. (2018). Overview of Books. Sarajevo: BiH Agency of Statistics.

Blackmur, D. (2007). A Critical Analysis of the UNESCO/OECD Guidelines for Quality Provision of Cross‐Border Higher Education. Quality in Higher Education, 13(2), 117–130. http://doi.org/10.1080/13538320701629137

Bobby, C. L. (2014). The ABCS of Building Quality Cultures for Education in a Global World. In International Conference on Quality Assurance. Bangkok: ICQA.

Bogue, E. G. (1998). Quality Assurance in Higher Education: The Evolution of Systems and Design Ideals. New Directions for Institutional Research, 1998(99), 7–18. http://doi.org/10.1002/IR.9901

Brankovic, J., & Brankovic, N. (2013). Overview of Higher Education and Research Systems in the Western Balkans: Bosnia and Herzegovina. Oslo: NORGLOBAL programme, Norwegian Research Council.

Brennan, J., & Shah, T. (2000). Managing quality in higher education : an international perspective on institutional assessment and change. Buckingham : Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Calderon, A. J. (2018). Massification of higher education revisited. Melbourne: RMIT University.

Chalmers, D. (2008). Teaching and Learning Quality Indicators in Australian Universities. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://pdf4pro.com/amp/view/teaching-and-learning-quality-indicators-in-1c5b7a.html

Constantinides, E., & Stagno, M. C. Z. (2011). Potential of the social media as instruments of higher education marketing: A segmentation study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 21(1), 7–24. http://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2011.573593

Council of Europe, & European Commission. (2005). Higher education reform in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Priorities for integrated university management. Sarajevo: Council of Europe.

Council of Europe, & European Commission. (2007). Standards and guidelines for quality assurance in higher education in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Brussels: European Commission.

Council of Europe, & European Commission. (2017). Institutional Evaluations of Seven Universities in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Summary Report. Brussels: European University Association.

Cunningham-Nelson, S., Mukherjee, M., Goncher, A., & Boles, W. (2018). Text analysis in education: a review of selected software packages with an application for analysing students’ conceptual understanding. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 23(1), 25–39. http://doi.org/10.1080/22054952.2018.1502914

De Ketele, J. M. (2008). The social relevance of higher education. In Global University Network for Innovation (GUNi) Report on Higher Education in the World. London: Palgrave.

EACEA. (2015). The European Higher Education Area in 2015: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/european-higher-education-area-2015-bologna-process-implementation-report_en

Eder, C. (2014). Displacement and education of the next generation: Evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina. IZA Journal of Labor and Development, 3(1), 1–24. http://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9020-3-12/TABLES/13

Enders, J., & Westerheijden, D. F. (2017). Quality assurance in the European policy arena. Policy and Society, 33(3), 167–176. http://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLSOC.2014.09.004

European Commission. (2007). Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Higher Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Brussels: European Commission and the Council of Europe. Retrieved from http://www.enqa.eu/files/BergenReport210205.pdf

European Commission. (2015). TEMPUS Project “Bosnia and Herzegovina Qualification Framework for Higher Education - BHQFHE.” European Union. Brussels: European Union, TEMPUS Project.

European Commission. (2017). Overview of the Higher Education System: Bosnia and Herzegovina. Brussels: European Union.

European Commission. (2018). The European Higher Education Area in 2018: Bologna Process Implementation Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. http://doi.org/10.2797/265898

Eurostat. (2020). Tertiary education statistics. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Tertiary_education_statistics

Ferencz, I. (2015). Balanced Mobility Across the Board—A Sensible Objective? The European Higher Education Area, 27–41. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_3

Figurek, A., Goncharuk, A., Shynkarenko, L., & Kovalenko, O. (2019). Measuring the efficiency of higher education: Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 17(2), 177–192. http://doi.org/10.21511/PPM.17(2).2019.13

Fürsich, E. (2009). In defense of textual analysis: Restoring a challenged method for journalism and media studies. Journalism Studies, 10(2), 238–252. http://doi.org/10.1080/14616700802374050

Gallacher, J., Toman, N., Caldwell, J., Raffe, D., & Edwards, R. (2005). Evaluation of the impact of the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF). Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Social Research.

Glewwe, P. W., Cuesta, A., Krause, B., Glewwe, P., Cuesta, A., & Krause, B. (2016). School Infrastructure and Educational Outcomes: A Literature Review, with Special Reference to Latin America. EconomÃa Journal, Volume 17(Fall 2016), 95–130. Retrieved from https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:col:000425:015158

Goodlad, J. I. (1990). Teachers for our nation’s schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Goncharuk, A. G., & Cirella, G. T. (2022). Effectiveness of academic institutional models in Europe: University instructor perception case research from Bosnia and Herzegovina and France. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(5), 836–853.

Gornitzka, A., & Stensaker, B. (2014). The dynamics of European regulatory regimes in higher education - Challenged prerogatives and evolutionary change. Policy and Society, 33(3), 177–188. http://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLSOC.2014.08.002

Harvey, L. (2005). A history and critique of quality evaluation in the UK. Quality Assurance in Education, 13(4), 263–276. http://doi.org/10.1108/09684880510700608

Harvey, L., & Green, D. (2006). Defining Quality. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 18(1), 9–34. http://doi.org/10.1080/0260293930180102

Heuvel, M. P. van den., & Siccama, J. G. (1992). The disintegration of Yugoslavia. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Hou, A. Y.-C. (2012). Mutual recognition of quality assurance decisions on higher education institutions in three regions: a lesson for Asia. Higher Education 2012 64:6, 64(6), 911–926. http://doi.org/10.1007/S10734-012-9536-1

Ilinska, L., Ivanova, O., & Senko, Z. (2016). Teaching Textual Analysis of Contemporary Popular Scientific Texts. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 236, 248–253. http://doi.org/10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2016.12.020

Ivic, I. (1992). Recent Developments in Higher Education in the Former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. European Journal of Education, 27(1/2), 120. http://doi.org/10.2307/1502668

Joint Declaration of the European Ministers of Education. (1999). The Bologna Declaration of 19 June 1999: Joint declaration of the European Ministers of Education. Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://www.eurashe.eu/library/bologna_1999_bologna-declaration-pdf/

Karaim, R. (2011). Expanding Higher Education: CQR. CQ Global Researcher , 5(22), 525–572. Retrieved from https://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/document.php?id=cqrglobal2011111500

Kis, V. (2005). Quality Assurance in Tertiary Education: Current Practices in OECD Countries and a Literature Review on Potential Effects. Paris: OECD.

Klaveren, C. van, Kooiman, K., Cornelisz, I., & Meeter, M. (2018). The Higher Education Enrollment Decision: Feedback on Expected Study Success and Updating Behavior. 12(1), 67–89. http://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2018.1496501

Kostić, M. D., Jovanović, T., & Letica, M. (2017). Perspectives on and obstacles to the internal reporting reform at higher education institutions – Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia. Management : Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 22(Special Issue), 129–143.

Kováčová, L., & Vacková, M. (2015). Applying Innovative Trends in the Process of Higher Education Security Personnel in Order to Increase Efficiency. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 186, 120–125. http://doi.org/10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2015.04.085

Kunitz, S. J. (2004). The Making and Breaking of Yugoslavia and Its Impact on Health. American Journal of Public Health, 94(11), 1904. http://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.11.1894

Lacity, M. C., & Janson, M. A. (2015). Understanding Qualitative Data: A Framework of Text Analysis Methods. Journal of Management Information Systems, 11(2), 137–155. http://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.1994.11518043

Lagrosen, S., Seyyed-Hashemi, R., & Leitner, M. (2004). Examination of the dimensions of quality in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 12(2), 61–69. http://doi.org/10.1108/09684880410536431

Lange, L., & Singh, M. (2013). External quality audits in South African higher education: Goals, outcomes and challenges. External Quality Audit: Has It Improved Quality Assurance in Universities?, 147–168. http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-676-0.50010-8

Magill, C. (2010). Education and fragility in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000191060

McQuay, M. (2014). Inevitable War? Examining Yugoslavia as a Fault Line Conflict. Securitologia, 20(2), 25–36. http://doi.org/10.5604/18984509.1140839

Nellie, A. (1980). Education in Eastern Europe. An Annotated Bibliography of English-Language Materials 1965-1976. Education in Eastern Europe. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Palmer, N. (2013). Scope, transparency and style: System-level quality strategies and the student experience in Australia. External Quality Audit: Has It Improved Quality Assurance in Universities?, 221–246. http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-676-0.50015-7

Rastoder, A., Nurovic, E., Smajic, E., & Mekic, E. (2015). Perceptions of Students towards Quality of Services at Private Higher Education Institution in Bosnia and Herzegovina. European Researcher, 101(12), 783–790. http://doi.org/10.13187/ER.2015.101.783

Rozsnyai, C. (2003). Quality Assurance before and after “Bologna” in the Central and Eastern Region of the European Higher Education Area with a Focus on Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland. European Journal of Education, 38(3), 271–283. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/1503503

Rushaj, S. (2015). The Right to Education in Minority Languages in Bosnia And Herzegovina: The Case of Roma Minority. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 4(2), 441–448. http://doi.org/10.5901/ajis.2015.v4n2p441

Ryan, T. (2011). Quality assurance in higher education: A review of literature. Higher Learning Research Communications, 5(4), 1. http://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i4.257

Samolovcev, B. (1989). Higher Education in Yugoslavia: A Historical Overview. In N. Soljan (Ed.), Higher Education in Yugoslavia. Zagreb: Andragoski Centar.

Savić, M., & Kresoja, M. (2016). Modelling factors of students’ work in Western Balkan countries. Studies in Higher Education, 43(4), 660–670. http://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1190960

Scott, G. (2008). University student engagement and satisfaction with learning and teaching. Sydney: University of Western Sydney.

Smidt, H. European Quality Assurance—A European Higher Education Area Success Story. (A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, & P. Scott, Eds.), The European Higher Education Area 625–637 (2015). Cham. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_40

Stensaker, B. (2011). Accreditation of higher education in Europe – moving towards the US model? Journal of Education Policy, 26(6), 757–769. http://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2010.551785

Suryadi, K. (2007). Key Performance Indicators Measurement Model Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process and Trend-Comparative Dimension in Higher Education Institution. In ISAHP 2007. Viña Del Mar: ISAHP 2007.

Tam, M. (2010). Measuring Quality and Performance in Higher Education. Quality in Higher Education, 7(1), 47–54. http://doi.org/10.1080/13538320120045076

Temple, P., & Billing, D. (2010). Higher Education Quality Assurance Organisations in Central and Eastern Europe. Quality in Higher Education, 9(3), 243–258. http://doi.org/10.1080/1353832032000151102

Turčilo, L. (2019). Youth study Bosnia and Herzegovina 2018/2019. Berlin : Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftunge.

UNESCO. (2020). Inclusion and education: All means all. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

UNICEF. (2017). Impact evaluation report: Impact evaluation of UNICEF Nigeria girls’ education project Phase 3 (GEP3) cash transfer programme (CTP) in Niger and Sokoto States. Abuja: United Nations Children’s Fund, Nigeria.

Uvalic-Trumbic, S. (1990). New Trends in Higher Education in Yugoslavia? European Journal of Education, 25(4), 407. http://doi.org/10.2307/1502626

Vlăsceanu, L., Grünberg, L., & Pârlea, D. (2004). Quality assurance and accreditation: A glossary of basic terms and definitions. Bucharest: UNESCO.

Weber, B. (2007). The crisis of the universities in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the prospects of junior scholars. Sarajevo: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftunge.

Wheelahan, L. (2011). From old to new: the Australian qualifications framework. Journal of Education and Work, 24(3–4), 323–342. http://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2011.584689

Williams, J. (2016). Quality assurance and quality enhancement: is there a relationship? Quality in Higher Education, 22(2), 97–102. http://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2016.1227207

World Bank. (2018). Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15-24) (modeled ILO estimate). Retrieved September 25, 2021, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS

World Education Forum. (2015). World Education Forum 2015. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en

Wright, P. Q. (2021). Between the Market and Solidarity: Commercializing Development Aid and International Higher Education in Socialist Yugoslavia. Nationalities Papers, 49(3), 462–482. http://doi.org/10.1017/NPS.2020.17

Yarashevich, V., & Karneyeva, K. (2013). Economic reasons for the break-up of Yugoslavia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 46(2), 263–273. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/48609746?seq=1

Young, M., Young, & Michael. (2005). National qualifications frameworks: their feasibility for effective implementation in developing countries (No. Skills Working Paper 22). Geneva: International Labour Organization. Retrieved from https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:ilo:ilowps:993766463402676

Zhang, Z., & Law, R. (2013). The concerns of authors: Textual analysis of online journal reviews. Serials Review, 39(4), 227–233. http://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2013.10766403