Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2022, vol. 48, pp. 143–164 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2022.48.9

Associations Between Global Competence and Right-Leaning Population: Evidence From PISA 2018 and European Social Survey

Jogaila Vaitekaitis

Vilnius university, Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics,

Institute of Data Science and Digital Technologies,

Faculty of Philosophy, Institute of Educational Sciences

E-mail: jogaila.vaitekaitis@fsf.vu.lt

Dovilė Stumbrienė

Vilnius university, Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics,

Institute of Data Science and Digital Technologies

E-mail: dovile.stumbriene@mif.vu.lt

Abstract. This study explores the relationship between 15-year-olds results in the PISA 2018 assessment of global competence and citizens’ political views. In particular, we look at the correlations of 18 EU nation-states citizens’ political preferences (right-leaning) and students’ non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values. Data from the OECDs’ PISA global competence and European Social Survey for the year 2018 were used. After the analysis, it can be presumed that the higher share of the right-leaning population in the country is associated with lower students’ global competencies.

Keywords: European education, global competence, PISA, political right, far-right, linear regression analysis

Dešines politines pažiūras turinčios populiacijos ir globaliųjų kompetencijų ryšys: įrodymai iš PISA 2018 ir European Social Survey tyrimų

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje tiriamas ryšys tarp piliečių politinių pažiūrų ir penkiolikmečių rezultatų PISA 2018 globaliųjų kompetencijų tyrime. Taikant tiesinę regresiją ir skaičiuojant Spirmeno koreliacijos koeficientą, tiriamas ryšys tarp 18-os ES šalių piliečių politinių preferencijų (polinkis į politinę dešinę) ir mokinių nekognityvinių įgūdžių, vertybių ir nuostatų. Naudojami 2018 m. duomenys iš EBPO PISA globaliųjų kompetencijų ir European Social Survey tyrimų.

Analizės rezultatai suponuoja, kad didesnė dešiniųjų pažiūrų gyventojų dalis šalyje yra susijusi su žemesnėmis mokinių globaliomis kompetencijomis. Nustatyta, kad dešiniųjų pažiūrų gyventojų dalis šalyje paaiškina daugiau nei 40 proc. globalių kompetencijų rezultatų, sietinų su mokinių nuostatomis dėl imigrantų ir (ne)pagarba kitų kultūrų žmonėms.

Tyrimo išvadose teigiama, kad 15-mečių PISA 2018 globalių kompetencijų rezultatai gali būti paveikti šalies visuomenės politinio-ideologinio konteksto. Remiantis atlikta klasifikacija, Latvijoje, Lenkijoje, Vengrijoje, Italijoje ir Bulgarijoje, kur daugiau nei 40 proc. gyventojų laiko save politiškai dešiniaisiais, mokiniai yra dažniau linkę nesutikti su tokiais teiginiais, kaip antai: aš gerbiu kitų kultūrų žmones kaip lygiaverčius žmones; su visais žmonėmis elgiuosi pagarbiai, nepaisant jų kultūrinės kilmės; ar imigrantų vaikai turėtų turėti tokias pat galimybes mokytis ir pan.

Diskusijos dalyje svarstoma, ar socialinės sanglaudos išlaikymas, empatijos, demokratiškų ir humanistinių vertybių puoselėjimas nėra tai, kas prarandama dėl perdėm didelio švietimo sistemų koncentravimosi į aukštą ekonominę pridėtinę vertę kuriančias mokinių gamtos mokslų, matematikos ir skaitymo akademines žinias. Visuomenių poliarizacijos, dehumanizacijos ir augančios įtampos kontekste keliami klausimai dėl švietimo sistemų gebėjimo švelninti radikalizaciją ir ekstremizmą.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: Europos švietimas, globaliosios kompetencijos, PISA, politinė dešinė, kraštutinė dešinė.

___________

Received: 20/01/2022. Accepted: 21/03/2022

Copyright © Jogaila Vaitekaitis,

Introduction

The importance of interrelationships between the context in which students live and learn and their achievements have been proven since the beginning of educational effectiveness research (see Coleman et al. 1966; Reynolds et al., 2014). While the impact of the socio-economic and cultural context of students and their families on achievements are studied quite extensively (Scheerens, 2016), linking prevailing political-ideological views with students’ non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values are not that common in educational sciences. Usually, politics are theorized in the context of curriculum standards (Young, 2014), testing (Lauder et al., 2012), school accountability (Želvys et al., 2019), funding, inclusion, or equality of education (Eurydice, 2020). Apple (2013); Ansell and Lindvall (2013); Mehta (2013) have described how political ideologies contribute to shaping educational ideas and policies. Likewise, researchers study how growing international large-scale student assessments impact educational decision-making (Sjøberg, 2019). One could say, that the keyword politics in educational research is most often understood as policy.

Nevertheless, we identified a few studies that did focus on politics per se and students’ competencies. Ross (2020) studied and described how and where do students get their political influences from. The research was based on 324 group discussions with 2000 young people, in 104 locations in 29 different European states and concluded that young Europeans see parents, not teachers, as the people with whom they most often talk about politics (Ross, 2020).

Talking politics at home has been proven as a booster to achievements in key academic subjects. Researchers (Chulz et al. 2010; Fjeldstad et al. 2010) proved, that growing up with parents who are socially and politically engaged has some modest association with stronger students’ engagement and knowledge of civic and political matters. Lauglo (2011), using a large-scale survey of Norwegian youth, demonstrated that students’ political socialization (talking with parents about politics and social issues at home) has a positive correlation with better performance in key academic subjects (mathematics, Norwegian and English languages) and their aspirations of higher education.

Further, in education research, participation in political processes and student attitudes have been linked. Knowles (2015) looked at how civic values and obedience to authority among students’ associated with democratic citizenship. The author concludes, that obedience to authority has a negative correlation with civic knowledge, citizenship self-efficacy, democratic values, and rejection of authoritarian governance. Kuang and Kennedy (2018) found a relationship between student participation in different forms of political protests in Hong Kong and their scores in the 2009 International Civic and Citizenship Education Study (ICCS). Moreover, the study found that different student-level results on the ICCS test could predict membership in “radical” or “rational” protest groups as well as engagement in legal or illegal protests.

In summary, the majority of reviewed educational science literature was considering politics as policy, less frequently, as students’ politicizing at home or school and its effect on students’ achievements as well as the relationship between students’ attitudes and their participation in political processes. As far as we know, there are no studies where the student’s results are analysed in the context of politics per se, in a form of left or right political ideological spectrum. This is also noticed by Giudici (2020), pointing out, that there is essentially no overlap between research on politics per se and education.

This paper contributes to the educational science literature by addressing the current knowledge gap by building a possible explanation of the association between political-ideological context and students’ results of global competencies (see more about this below). The purpose of the study is to estimate the association between the share of politically right-leaning population in country and students’ non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values in global competencies in 18 European countries. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, we elaborate on the concept of global competence and its critique, and discuss the intersection of global competences and right-leaning population variable, while the data used and methods are presented in Section 2. The results are analysed in Section 3 as well as Section 4 where discussion can be found. Finally, the main conclusions are presented in Section 5 and the limitations of the research are identified in Section 6.

1. Global competence

Education is one of the strongest factors associated with social cohesion and levels of trust and tolerance (Borgonovi, 2012). It is blatant, that an increasingly complex and interconnected globalized world requires not only mathematical or scientific literacies but the ability to understand cultural heterogeneity, recognize core values of democracy, empathy, and diversity. What kind of knowledge, skills, and values do students need to prepare for these challenging times? The OECD suggests an answer – people with global competence. In the 2018 cycle of PISA, OECD has assessed 15-year-old students’ global competence – a multidimensional capacity that encompasses skills, knowledge, and values, as OECD states, “needed to thrive in an interconnected world” (OECD, 2020, p. 53).

The idea of global competence has been circulating in the academic literature for several decades. Nonetheless, according to Sälzer and Roczen (2018), this relatively young construct has many different interpretations and no agreed-upon definition. For example, German researchers usually discuss global competence in the context of education for global and sustainable development, while English-language researchers focus on intercultural communication, linguistic and cultural competencies, and behaviors (Sälzer and Roczen, 2018). According to Vaccari and Gardinier (2019), the idea of assessing this novel and unsettled construct originated from UN Agenda 2030 Goal 4.7, which calls all nation-states by 2030 to:

“ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and culture’s contribution to sustainable development” (UN, 2015).

To track this goal, UNESCO has teamed up with the OECD, whose task was to develop and assess the mentioned indicator. In developing this concept OECD, has cooperated with another organization called Asia Society1, according to which, global competence is necessary for employability in the global economy, for living cooperatively in multicultural communities, for young people to communicate and learn effectively and responsibly with old and new media, and for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (Asia Society/OECD, 2018). One of the founders of this concept – Reimers (2013) refers to it as an idea of “the new civics of the 21st Century” (p. 1). In doing so OECD was seeking unification of the concepts of global citizenship, intercultural competence, and knowledge on globalization (Sälzer and Roczen, 2018). After developing the concept, the OECD integrated it into its triennial large-scale student assessment PISA 2018 (Robertson, 2021) in the form of cognitive tests and student questionnaires. The end result – the framework of global competence as defined by the OECD - a multidimensional ability to: 1) examine issues of local, global and cultural significance; 2) understand and appreciate the perspectives and worldviews of others; 3) engage in open, appropriate and effective interactions across cultures; and 4) take action for collective well-being and sustainable development (OECD, 2020).

Each of the four dimensions listed in the OECD global competence framework has multiple components. First dimension - examining local, global and intercultural issues focuses on students’ familiarity with specific topics by asking whether students can explain climate change or population growth, migration, causes of poverty, etc. The second dimension focuses on understanding and appreciating the perspectives and worldviews of others. It is assessed by asking students to self-report how well do such statements describe them, e.g.: I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision; I am interested in how people from various cultures see the world; I respect people from other cultures as equal human beings; Immigrants should have all the same rights that everyone else in the country has; etc. The third dimension of global competence awareness of intercultural communication assesses the ability to engage in open, appropriate, and effective communication across cultures by asking students to imagine them talking to a person whose native language is different from their own. This hypothetical engagement is then, followed by statements like: I carefully observe their reactions; I frequently check that we understand each other correctly; etc. Lastly in this dimension, students are asked whether they have contact with people from other cultures at school, in their family, neighbourhood and circle of friends. The fourth dimension had two components, first: self-reported information from students on actions taken for sustainability and collective well-being (energy use reduction at home; boycotting products or companies for political, ethical, or environmental reasons; etc.); and second: a sense of agency regarding global issues (do students think of themselves as citizens of the world; do they think their behaviour can impact people in other countries; etc.) The full list of questions and statements can be found in OECD PISA 2018 data website2.

1.1. Debates over the OECD’s global competence framework

The inclusion of ‘global’ in school curriculum and calls to become ‘global citizens’ is understood as a necessity in order to ‘thrive in an interconnected world’ by both the OECD (Colvin & Edwards, 2018) and The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2016). Indeed, schools are challenged to prepare children and adolescents to cope with hyper complex phenomenon of globalization, climate crisis, or structural injustices. However, the very term globalization is ‘loaded’ and has different interpretations; to no surprise, the call for teachers to integrate global competence into their existing curriculum, instruction, and evaluation, and, above all, rate countries internationally raises many questions for a number of researchers.

The main critical interrogation of the global competence framework stems from critical theory and postcolonial body of thought. Researchers claim that the global competence framework in its current form enables social reproduction (Vaccari and Gardinier, 2019), the perpetuation of global inequalities (Andrews, 2021), reinforces the us-them divide, and promotes neoliberal hegemony (Robertson, 2021), silences the voices and theories from the global South (Grotlüschen, 2018), also critical observations are expressed regarding insufficient instrument validation, theory-building, Western bias and a lack of intercultural comparability (Sälzer and Roczen, 2018). In the following, we review some of these concerns.

After conducting a comparative analysis of UNESCO and OECD definitions of global citizenship and global competence Vaccari and Gardinier (2019) concluded that both organizations are leading educators along two distinctly different pathways. According to these researchers, the OECDs’ vision of education for global competence could be summarized as a movement toward national economic development and global competition with divergent values, but common markets, while UNESCO sees global citizenship as post-national identity and belonging to global community and shared values (Vaccari and Gardinier, 2019). Both organizations are claimed to lead global competence and global citizenship concepts towards risky paths enabling the perpetuation of global inequalities rather than reducing or transforming them (Vaccari and Gardinier, 2019).

Similarly, Andrews (2021) deducts that OECD’s global competence framework is enabling social reproduction. According to the author, the OECD’s global competence framework can counteract the intent of the framework and could contribute to the reproduction of inequality within society because it lacks conceptual clarity and was developed without any diversity in expert groups. According to Andrews (2021), Global competence reproduces the habitus of an Anglosphere elite. The author calls for reforming the framework to one that encourages changing the world rather than just reacting to a changing world (Andrews, 2021).

A discourse analysis focusing on OECD documents including minutes and drafts from expert groups’ consultations during the construction of the global competence framework conducted by Grotlüschen (2018) reveals that during the reiterative processes of expert group discussions voices and theories from the global South were effectively eliminated. This lead to western, cognitive, rational, late modern discourse disqualifying any postcolonial, queer, feminist, and moral theories that were present in the inception of the document (Grotlüschen, 2018). Salzer and Roczen (2018) could elaborate. According to them, the many unresolved challenges and disagreements regarding the construction of the global competence framework led more than 30 countries to withdraw from participating in the global competency assessment in PISA 2018 (Salzer and Roczen, 2018).

Robertson (2021) analyses the concept of global competence, stating that it promotes a neoliberal worldview. According to author, the global competence of the OECD reinforces the divide between us and them by portraying cultures as exotic features ‘over there’, while the question of capitalism, patriarchy, and colonialism, which, as stated by the author, is key to understanding the global North and South relations, is not being addressed at all. Robertson (2021) states, that this concept is overly tolerant of global capitalism and normalizes the neoliberal status quo “It is aimed at advancing US corporate capital’s interests through the cultural production of the new worker citizen able to participate in the global economy” (Robertson, 2021, p. 168). The author claims that global competence lacks the radicalism that the global world needs, that is, knowledge of the links between climate change and capitalism’s accumulation model.

Recognizing the reviewed criticism regarding the OECD’s global competence framework, present study considers that analysis of this data can provide new knowledge, though at the same time legitimizing the construct in question. We hold, that analysis and comparison of self-reported information from students can give valuable insights for social science researchers, teachers, non-governmental organizations working on global citizenship education, educational policymakers, curriculum developers, and teacher training institutions.

1.2. Global competence and right-leaning population

We are focusing our attention at the intersection of students’ global competence and populations’ political self-identification (right-leaning). It can be assumed that 15-year-olds live and study in a given context, which is impacted by society. It has been argued, that societal values, and cultural beliefs are connected with students’ school relevant variables (e.g. motivation) (Hofer and Peetsma, 2005). Boekaerts (2003) also states, that students’ cognition, feelings and behaviour are shaped by cultural context of society, which, in turn is affected by specific political or religious traditions. In the analysis of political self-identification of society, categories of the left and right are typically used (Wiesehomeier and Doyle, 2012). Classical political left-right dichotomy can be expressed by different attitudes and believes concerning equality (Bobbio, 1996). Thus, while the left seeks greater equality in society, the right considers inequality as a natural social order, meanwhile (neo)liberal right legitimizes inequality by transferring the responsibility to the individual (Wiesehomeier and Doyle, 2012).

Nevertheless, one should note, that citizens who identify as politically left or right might not share similar beliefs and convictions. It has been suggested, that in different countries political “left” and “right” have evolved to mean different things (Piurko et al., 2011, Wiesehomeier and Doyle, 2012; Vegetti and Širinić, 2019). Using data from European Social Survey researchers Piurko et al. (2011) compared the importance of personal values in choosing the “left” or “right” political orientations in 20 European countries and concluded, that in liberal and traditional countries3, universalism and benevolence values predicted left political orientations, and conformity and tradition values predicted a right political orientation, while in post-communist countries none of the values had explanatory value, with sociodemographic factors having a lot stronger predictability (Piurko et al., 2011).

OECDs’ conceptual framework of global competence primarily emphasises attitudes and values as opposed to cognitive skills and knowledge (OECD, 2020). From what was described in the previous sections, OECD’s global competence does promote gender and racial equality, cosmopolitanism, multiculturalism, environmentalism, human rights protection, pro-immigrant attitudes, individual responsibility, and other principles that might be interpreted with caution by societies that have high population share of self-identified political right. It has been argued, that right-wing politics promote views that represent conservative and traditional cultural values (Mudde, 2016; Wondreys, 2021), also it is claimed, that right-leaning people having more pronounced negative attitudes towards immigrants throughout Europe (Inglehart and Norris, 2016; Deimantas, 2021). Thus, one could hypothesize, that OECD’s global competence results might be negatively associated with the right-leaning population.

2. Data and method

For estimation of the relationship between the global competence of students and the political position of European country citizens, we combined the OECD PISA data with data from the European Social Survey (ESS) for the year 2018. PISA measures the knowledge and skills of representative samples of 15-year-old students, i.e. the outcomes of education at a point at which most young people are still enrolled in formal education. ESS measures the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviour patterns of diverse populations in countries and is representative of all persons aged 15 and over (no upper age limit). Due to the limited scope of the article, we direct our attention only to right-leaning political views.

It is important to note, that the countries that participated in PISA survey in the global competence assessment, chose different levels of participation:

“The PISA 2018 global competence assessment relied on two instruments: 1) a cognitive test focused on the cognitive aspects, including knowledge and cognitive skills; and 2) a set of questionnaire items collecting self-reported information from students, parents, teachers and school principals.” OECD (2020, p. 19)

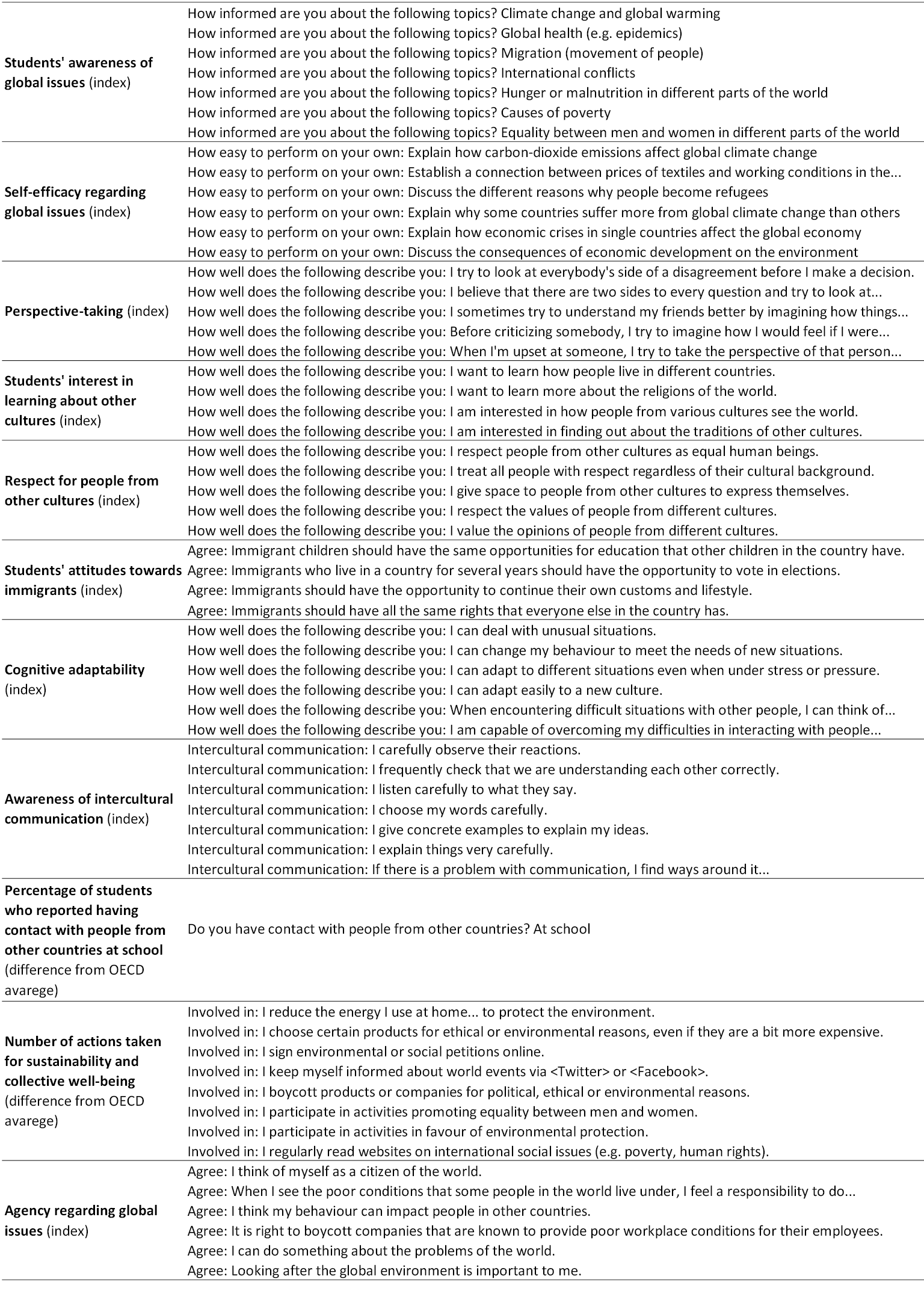

We note that 22 EU countries completed the student questionnaire and only 7 EU countries completed both the cognitive test and the student questionnaire. Since this study focuses only on EU countries, we analysed the results of the global competence questionnaire that collected self-reported information from students. According to OECD (2020), student self-reported information covers non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values. For the analysis, we used the global competence indexes constructed by OECD from questionnaire items collected from the self-reported student questionnaire (the constructs of global competencies and its statements from students’ questionnaires are presented in Table 2 in Appendix).

Constructs of global competencies:

• Student awareness of global issues (index),

• Self-efficacy regarding global issues (index),

• Perspective-taking (index),

• Student interest in learning about other cultures (index),

• Respect for people from other cultures (index),

• Students’ attitudes toward immigrants (index),

• Cognitive adaptability (index),

• Awareness of intercultural communication (index),

• Share of students who had contact with people from other countries at school (difference from the OECD average),

• Number of actions taken for sustainability and collective well-being (difference from the OECD average),

• Agency on global issues (index).

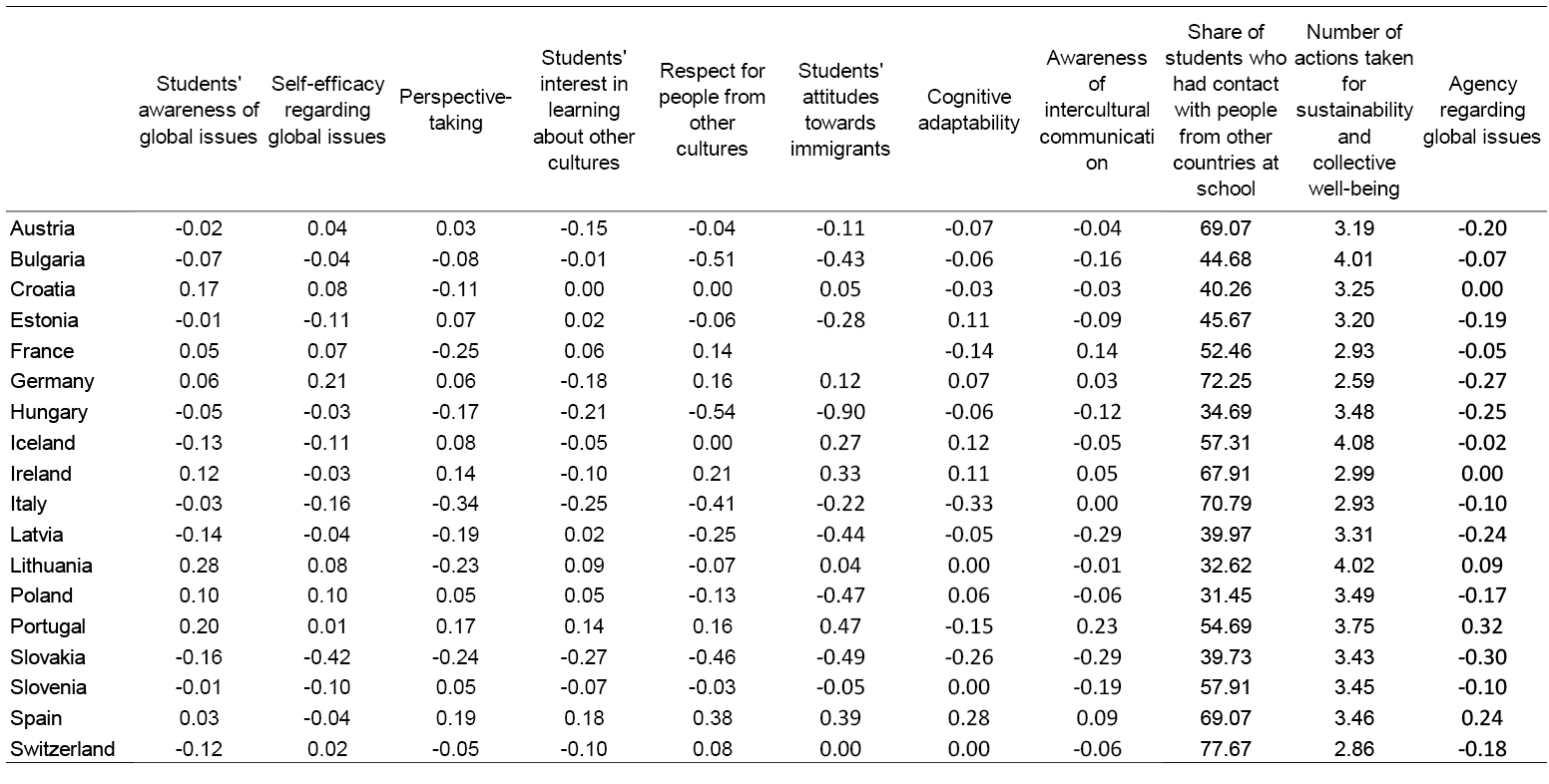

Dataset of the global competencies constructs is presented in Table 3 in Appendix. The positive values of the indices indicate that the global competence is greater than the OECD countries’ average. For example, the positive values in the index of Student awareness of global issues indicate that the student expressed greater awareness of global issues than the average student in the OECD countries.

Data concerning the results of citizens’ political positions in European countries have been taken from the European Social Survey (ESS). The indicator Placement on the left-right political scale4 was used. Using the ESS scale, where 0 means left and 10 means right, we divided respondents into three groups – respondents choosing [0 to 4] were labelled as a self-reported political left, respondents choosing [6 to10] - as a self-reported political right, and respondents who are in the center of the political spectrum (on the scale choose ‘5’) were identified as neutral. Next, we use the definition of the share of left-leaning, right-leaning, and neutral populations, accordingly.

In the countries’ comparative analysis, we used the Spearman correlation coefficient as a measure of the strength of the relationship between the students’ global competence and countries’ population political preferences (leaning right). To quantify the importance of the share of the right-leaning population for each global competence construct, linear regression models for each global competence construct were performed and the determination coefficients calculated. The analysis was performed for all countries that participated in both surveys (PISA and ESS): Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland. The data for the students’ global competence are available at the OECD database5 and the data for the placement on the political spectrum scale are available at the ESS database6.

3. Results

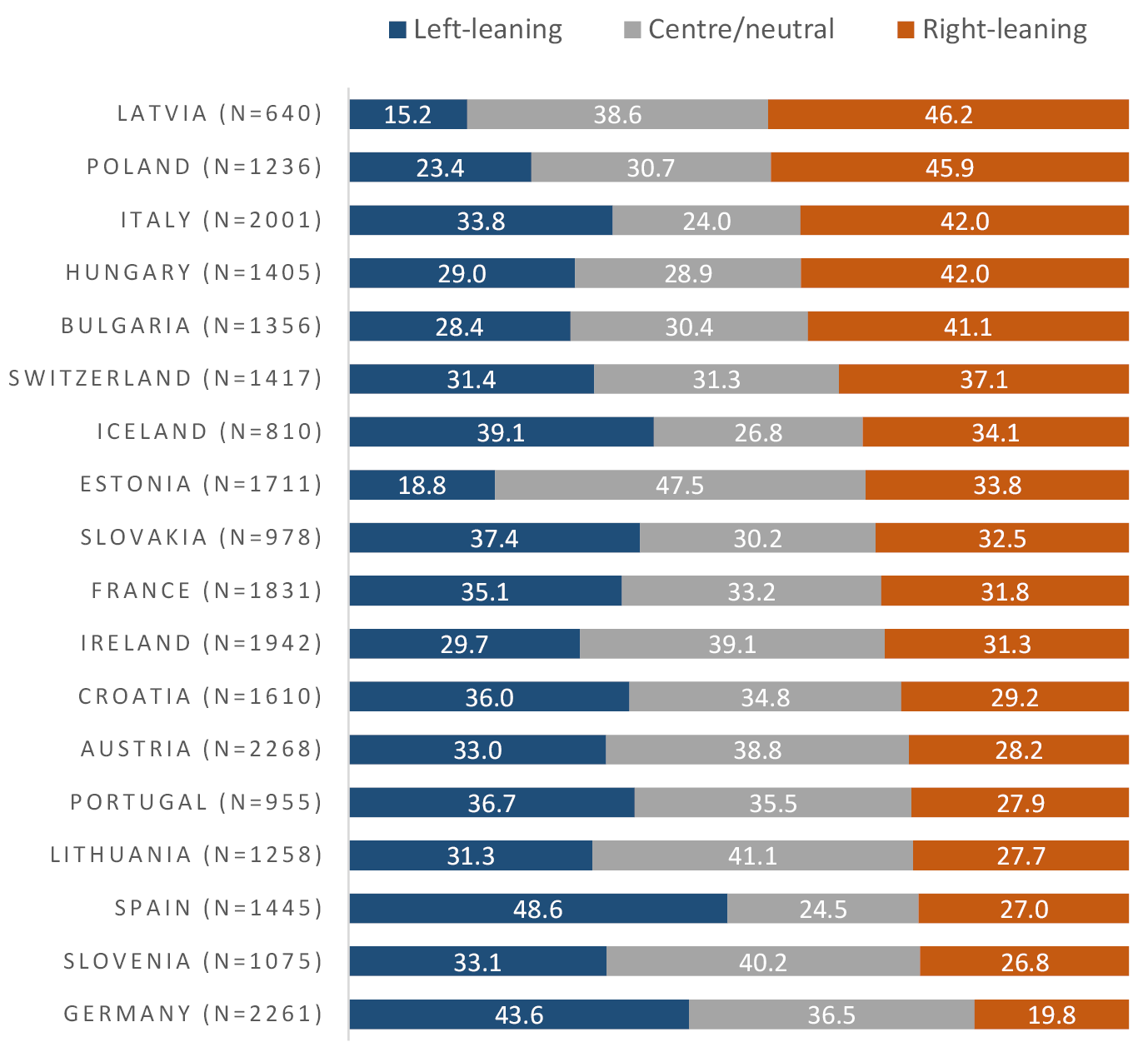

According to our classification, the top five nation-states that have the largest shares of right-leaning populations are Latvia (46.2%), Poland (45.9%), Hungary (42%), Italy (42%), Bulgaria (41%) (Figure 1). On the other side of the spectrum – countries, that have the largest shares of left-leaning populations: Spain (48.5%), Germany (43,6%), Iceland (39.1%), Slovakia (37.4%), Portugal (36.7%). In almost all countries, a third of the people consider themselves at the center of the political spectrum. Staying politically neutral is safe and comfortable, it enables individuals to choose the best of both worlds. It is intuitive that people considering themselves in the political center tend to lean left regarding some issues and right regarding others. In this study, we focus on estimating the association between the share of politically right-leaning population in country and students’ non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values of global competencies.

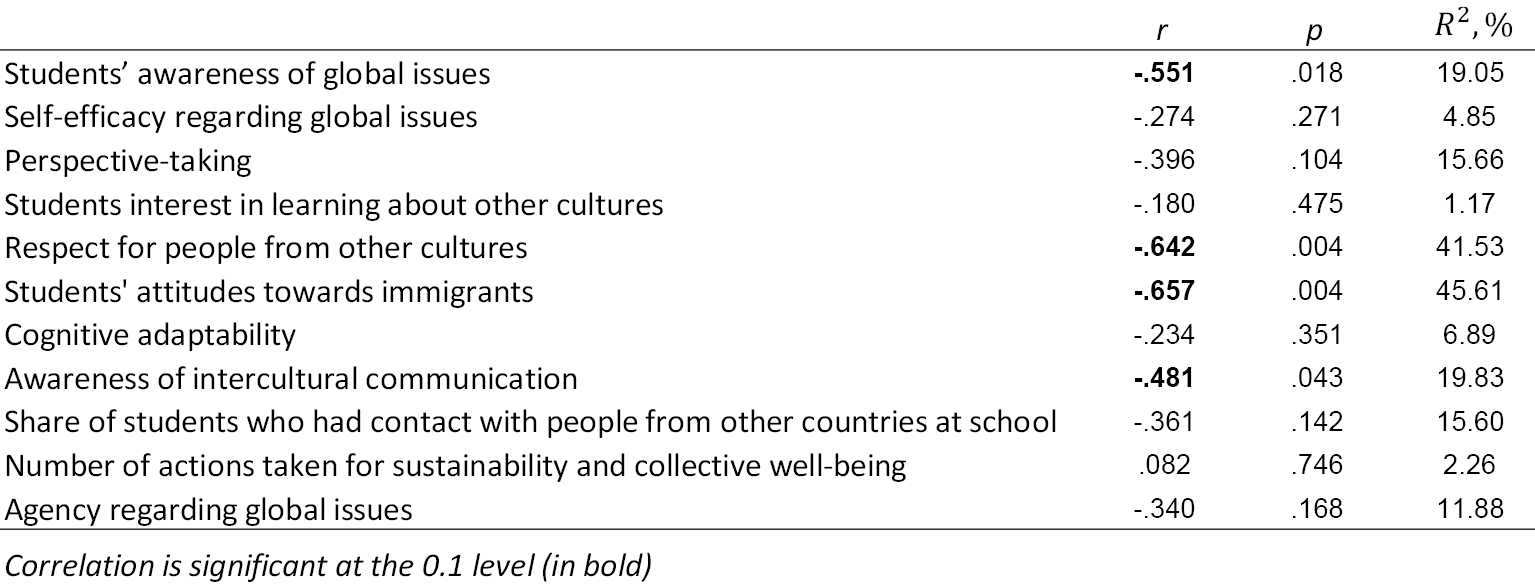

For the correlation and regression analysis, we used all 11 constructs of global competence and the share of the right-leaning population in the country7. We can note that the percentage of the right-leaning population in the country negatively correlates with all global competence constructs except the number of actions taken for sustainability and collective well-being (Table 1). A statistically significant negative correlation is observed between the percentage of the right-leaning population and four global competence constructs: students’ attitudes towards immigrants, respect for people from other cultures, students’ awareness of global issues, and awareness of intercultural communication.

Figure 1. The percentage of left-leaning, neutral, and right-leaning populations in analyzed European countries.

To quantify the importance of the share of the right-leaning population for each construct, linear regression models for each global competence construct were performed and the determination coefficients (R2) were calculated. The share of the right-leaning population in the country explains the highest portion of variation in students’ attitudes toward immigrants and respect for people from other cultures (more than 40%) followed by awareness of intercultural communication and students’ awareness of global issues (almost 20%) (Table 1).

The statistically significant negative correlations between the share of the right-leaning population in the country are associated with lower students’ questionnaire results related to people from different countries and cultures (students’ attitudes toward immigrants, respect for people from other cultures, and awareness of intercultural communication) and students’ awareness of global issues (climate change and global warming, global health, migration, international conflicts, hunger or malnutrition in different parts of the world, causes of poverty, equality between men and women in different parts of the world). One could say that a higher proportion of the right-leaning population in a country is associated with lower global competence non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values of 15-year-olds. According to OECD (2020), people with the skills and attitudes to succeed in an interconnected world are capable of seeing global problems from multiple perspectives and interpreting other people’s perspectives as well. It is believed that if people learn about the history, values, communication styles, beliefs, and practices of other cultures, they become capable of understanding the influence of multiple factors on their own thinking and behaviour (Hanvey, 1982). Next, the strongest associations between the students’ global competence constructs’ and countries’ share of the right-leaning population are presented.

Table 1. Spearman correlation coefficients (r) and p-values (p) between global competence constructs and the share of the right-leaning population in the country, and determination coefficient (R2).

As was mentioned, the highest correlation is observed between students’ attitudes toward immigrants and the share of the right-leaning population in the country (r=-0.657, p=0.004). It can be stated, that lower students’ attitudes towards immigrants are associated with a higher proportion of the right-leaning population in a country (the positions of the countries are shown in Figure 2). The share of the right-leaning population in the country explains 45.61% of the variation in result of the students’ attitudes towards immigrants.

Based on the classification performed, Latvia, Poland, Hungary, Italy, and Bulgaria have the highest proportion of people considering themselves politically right-leaning (46.2%, 45.9%, 42%, 42%, and 41.1% of the right-leaning population accordingly). In these countries as well as in Slovakia and Estonia, the higher share of 15-year-olds tend to disagree with statements such as Immigrant children should have the same opportunities for education that other children in the country have or; Immigrants who live in a country for several years should have the opportunity to vote in elections; etc. (all statements from which the index is composed are presented in Table 2 in Appendix, see section Students’ attitudes towards immigrants). The extremely low index of students’ attitudes towards immigrants is observed in Hungry.

Figure 2. Students’ attitudes towards immigrants vs. a share of the right-leaning population in the country (r=-0.657, p=0.004).

On the opposite side of the spectrum, countries with the highest scores of students’ attitudes toward immigrants index – Portugal, Spain, Ireland, and Iceland. These countries demonstrate the highest percentages of students that would agree with the statements like Immigrants should have the opportunity to continue their own customs and lifestyle; Immigrants should have all the same rights that everyone else in the country has; etc. (all statements from which the index is composed are presented in Table 2 in Appendix, see section Students’ attitudes towards immigrants). Portugal, Spain, and Ireland have less than one-third population self-identifying as right-leaning.

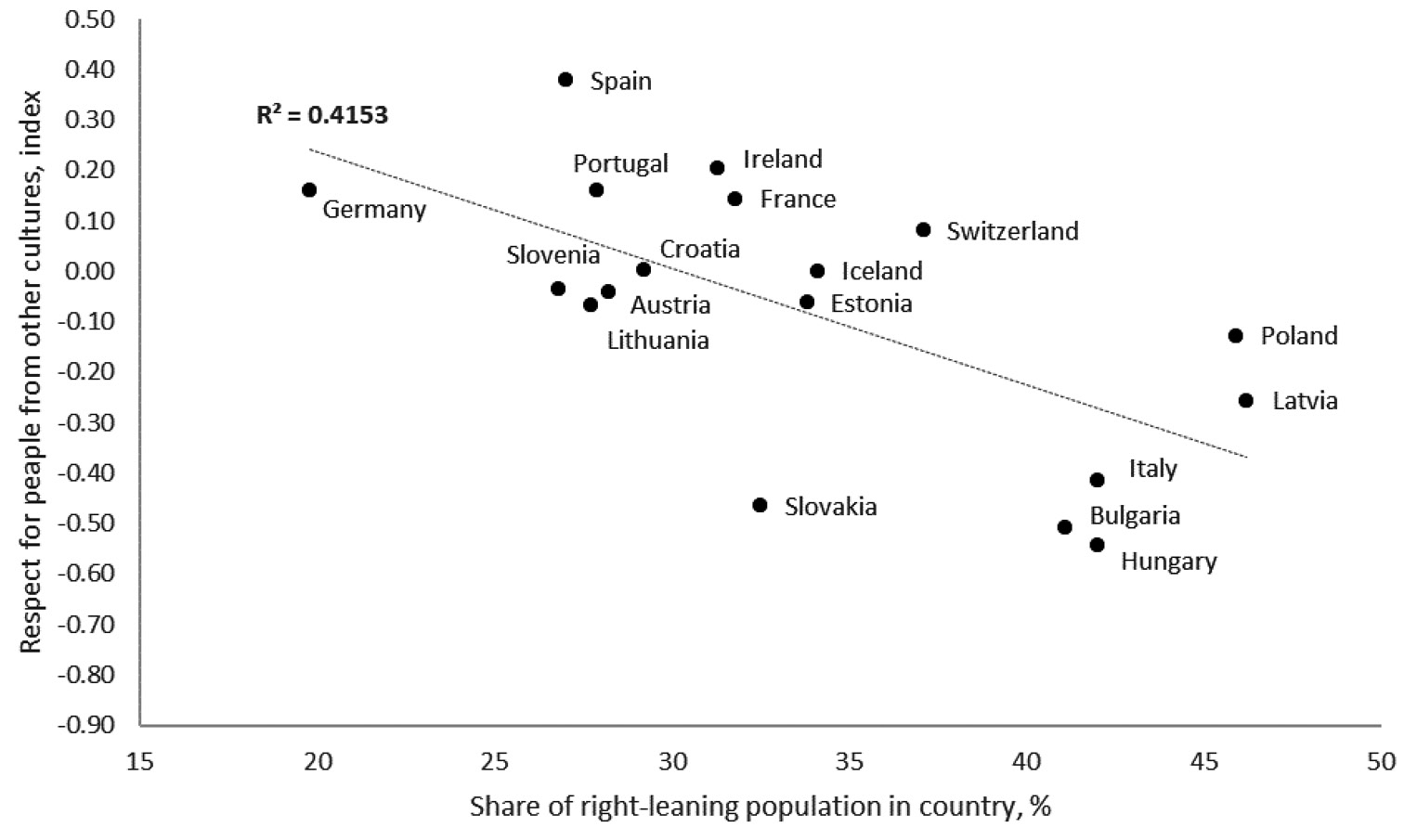

A similar situation is observed when students are asked whether they respect people from other cultures as equal human beings. A strong negative correlation is observed between the index of respect for people from other cultures and the percentage of the right-leaning population in the country (r =-0.642, p=0.004). The positions of the countries can be seen in Figure 3. The share of the right-leaning population in the country explains 41.53% of the variation in result of the respect for people from other cultures.

The arrangement of the respect for people from other cultures index is similar to that of the already explored index of attitudes towards immigrants, with a lower distribution of countries. The highest share of the right-leaning population in the country is associated with the lowest respect for people from other cultures of 15-year-olds (Latvia, Poland, Hungary, Italy, and Bulgaria). Slovakia stands out because it does not have a high percentage of the right-leaning population in the country, but the index of respect for people from other cultures in Slovakia is one of the lowest among the analysed countries and is similar to those in Hungary, Bulgaria, and Italy.

Figure 3. Respect for people from other cultures vs. a share of the right-leaning population in the country (r=-0.642, p=0.004).

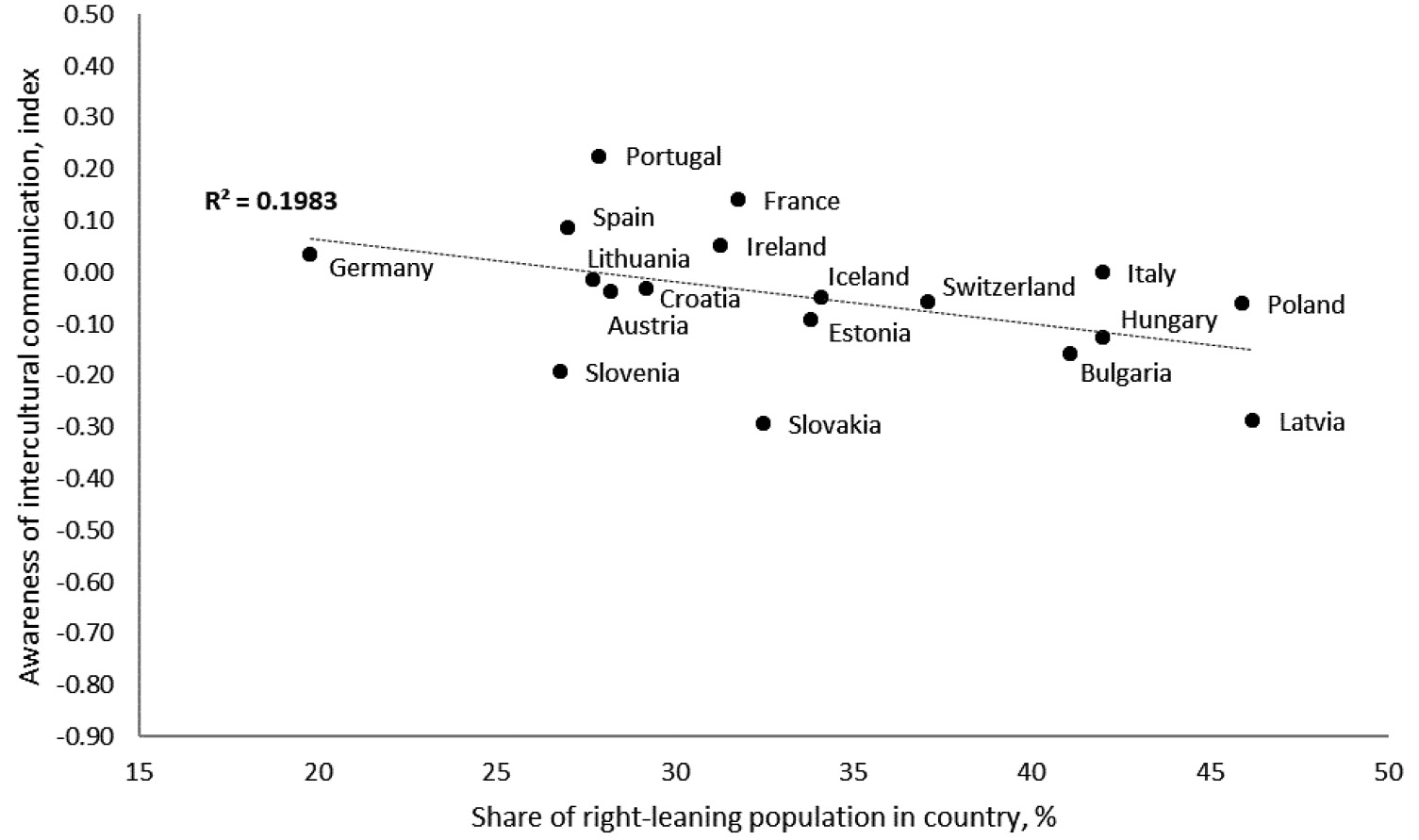

Another significant correlation is observed between the percentage of the right-leaning population in the country and the index of students’ awareness of intercultural communication (r=-0.481, p=0.043). The positions of the countries are shown in Figure 4. The share of the right-leaning population in the country explains 19.83% of the variation in result of the awareness of intercultural communication.

Figure 4. Awareness of intercultural communication vs. a share of the right-leaning population in the country (r=-0.481, p=0.018).

A higher proportion of the right-leaning population in the country is associated with lower students’ awareness of intercultural communication i.e. fewer students agree that in talking with people from other cultures they frequently check that they are understanding each other correctly; and less carefully observe their reactions, etc. (all statements from which the index is composed are presented in Table 2 in Appendix, see section Respect for people from other cultures). The lowest students’ awareness of intercultural communication is in Latvia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria, and Hungary. Latvia, Bulgaria, Hungary could be singled out as having a high percentage of the right-leaning population.

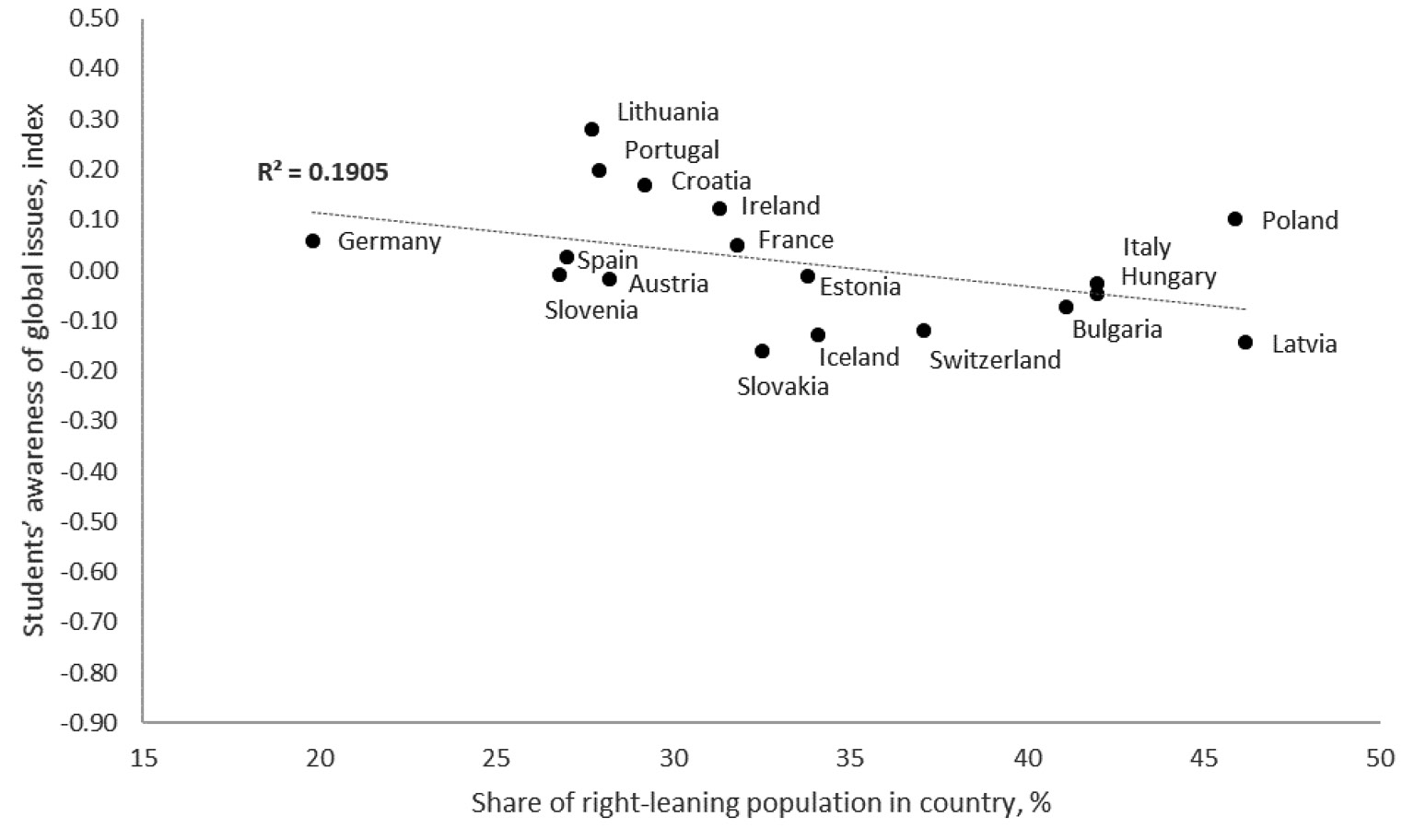

One more noticeable example of the share of the right-leaning population and negative correlation with global competence is students’ awareness of global issues (r=-0.551, p=0.069). One could say that a lower students’ awareness of such global issues as international conflicts, migration, equality between men and women, causes of poverty, hunger, or climate change is associated with a higher proportion of the right-leaning population in a country (the positions of the countries are shown in Figure 5). The share of the right-leaning population in the country explains 19.05% of the variation in result of the students’ awareness of global issues.

Figure 5. Students’ awareness of global issues vs. a share of the right-leaning population in the country (r=-0.551, p=0.018).

Students’ awareness of global issues is lower than the OECD average in 4 out of 5 countries with higher than 40 percent of the right-leaning population – in Latvia, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Italy, with the exception of Poland. Lithuania, Portugal, Croatia, Germany, Ireland stand out as having high student awareness of these issues and a relatively low percentage of the right-leaning population in the country.

4. Discussion

By focusing on the cross section of political views of populations and their 15-year-olds results in the PISA 2018 assessment we estimated that the lower students’ global competence is associated with the higher share of the right-leaning population. Students’ attitudes toward immigrants, respect for people from other cultures, awareness of intercultural communication and such global issues as international conflicts, migration, equality between men and women, causes of poverty, hunger, or climate change are lower in countries with higher share of the right-leaning population.

One should note, that our study used a broad-spectrum ‘right-leaning’ variable, which might include not only the population that has conservative views but also the population ideologically close to far-right. Ideology can be defined as an ‘all-encompassing set of ideas’ needed for people to interpret and judge social reality (Bale, 2017). Far-right ideology is characterised by authoritarianism; anti-democratic or anti-liberal attitudes; and anti-egalitarianism (a belief that some social groups (usually nations, genders, races, or religions) are inherently unequal) (Giudici, 2020; Carter, 2018). A recent study reported by Krzyżanowski (2020) points out how right-wing populist politics use an immigration-related moral panic to introduce and normalise radical or often blatantly racist discourse into the public domain. The main finding of our study indicates that the higher share of the right-leaning population in the country is associated with lower students’ global competencies related not only to students’ awareness of international conflicts, migration, equality between men and women, causes of poverty, hunger, or climate change, but most significantly with migrants and people from different cultures. It can be argued that 15-year-olds results in the PISA 2018 assessment of global competence may be impacted by a given political-ideological context of the country as reflected in the political preferences of the society including, the far-right and populist views.

To discuss our findings in the broader context it is important to acknowledge, that during the last decade, following the 2015 European migrant “crisis” extremist, far-right political movements increased their influence using concerns about immigration, globalization, and religion across Europe (Wondreys, 2021; Mudde, 2016). Far-right political parties polarized societies in Central and Eastern Europe (Mudde, 2019; Krzyżanowski, 2020). Similarly, conservatively-nationalist anti-immigrant rhetoric was prevalent during the Brexit campaign (Hobolt, 2016; Inglehart and Norris, 2016). At the time of writing this, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees report of violent cross-border asylum seeker pushbacks on the Latvian, Lithuanian, and Polish border with Belarus” (UNHCR, 2021). This is followed by growing racist, xenophobic, and islamophobic attitudes in the broader society of Lithuania (Blažytė et al. 2020; Blažytė, 2021). Does the present political discourse affect students’ non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values? Future studies on the current topic are therefore recommended. It should also be mentioned, that many factors can be related to the students’ results in the global competence questionnaire discussed in our study. These factors can range from education policy to curriculum, or structural and cultural factors. Only one (share of right-leaning population) of the many factors was the focus of this article, other possible factors are beyond the scope of this investigation. Thus, future studies on possible factors are therefore recommended.

There is a heated discussion within the educational community about how over obsession with student testing in the main academic fields such as science, math, or reading could impoverish the potential spectrum of educational experiences (Želvys, 2018; Spring, 2015). It is argued, that prioritising the skills and knowledges needed for competitiveness in the market economy overshadows the socio-cultural potential of education. Such educational goals as social justice, intercultural inclusion, integration and active democratic citizenship might be the ones who are overlooked. As described by Ross (2020) who was studying to what extent do the schools contribute to the formation of students’ political selves - the majority of students recognize that their teachers are reluctant to talk about political issues in the classroom. The author highlights the need for reflexive, critical and in-depth look at the education per se.

It is believed, that education might serve as prevention of radicalization and violent extremism (UNESCO, 2015), but at the same time, it is also a catalyst of larger societal perturbations. Countries that are way above average in educational attainment also demonstrate students values and attitudes that are echoing extremist ideologies. In this context, educational communities should be empowered to reflect the fact that schools are never apolitical, the curriculum is never neutral, and values are always subjective. To reflect this, educational decision makers could rethink whether the humanistic declarations in the policy documents are still relevant, if so, whether they are being followed through. Teacher trainer organizations could provide teachers with conceptual tools to reflect their personal values and attitudes, prepare them not to be apolitical in the classroom, since the unanswered student questions may be filled by the visions of fear-mongering populists. In order for teachers to take appropriate steps in empowering students, they should have the opportunities to work outside the strict high-stakes testing labour market oriented educational paradigm.

5. Conclusions

Educational science literature often focuses on politics as policy and centres on how different policies affect the organization, process, outcomes, and other aspects of educational systems. In present study, we are bridging the gap in the educational science literature by analysing student’s results in the context of politics per se, in a form of right political ideological spectrum. We estimated the association between the share of politically right-leaning population in country and students’ non-cognitive skills, attitudes, and values of global competencies in 18 European countries. While the OECD framework of global competence is being criticized by various authors as being neoliberal and having western bias, the results of the analysis, nevertheless, prove to be valuable. In the discussion of the results obtained, we raised the idea that it is necessary to look at the intersections of politics and education due to the polarization of society, instrumentalisation of people and the growing tensions in the region.

The analysis revealed, that students’ self-reported ability to examine issues of local, global and cultural significance; ability to understand and appreciate the perspectives and worldviews of others; ability to engage in open, appropriate, and effective interactions across cultures, or, in other words, students’ global competence is associated with the share of the right-leaning population in the country. Looking at the particular global competence constructs, we identified, that statistically significant negative correlations are between the share of the right-leaning population in the country and students’ attitudes toward immigrants, respect for people from other cultures, awareness of intercultural communication and students’ awareness of global issues (international conflicts, migration, equality between men and women, causes of poverty, hunger, or climate change). The share of the right-leaning population in the country explains 45.61% of the variation in result of the students’ attitudes towards immigrants, 41.53% of the variation in result of the respect for people from other cultures, 19.83% of the variation in result of the awareness of intercultural communication, and 19.05% of the variation in result of the students’ awareness of global issues.

The share of the right-leaning population in the country explains more than 40% of variation in result of global competence based on students’ attitudes toward immigrants, respect for people from other cultures. As discussed above, anti-egalitarianism is typical for far-right ideologies. Our constructed variable ‘right-leaning’ includes not only the population that has conservative views but also a population that might be closer to far-right. Based on our classification, Latvia, Poland, Hungary, Italy, and Bulgaria have more than 40% of population considering themselves politically right-leaning. The lowest result of global competence based on attitudes towards immigrants and respect for people from other cultures are in these countries together with Slovakia and Estonia (third of population considering themselves as right-leaning). These countries have the highest share of 15-year-olds that tend to disagree that immigrant children should have the same opportunities for education, immigrants should have the opportunity to vote in elections, to continue their own customs and lifestyle, and have all the same rights that everyone else in the country has. Also, students in these countries tend to disagree with statements such as I respect people from other cultures as equal human beings; I treat all people with respect regardless of their cultural background; I give space to people from other cultures to express themselves; I respect the values of people from different cultures; I value the opinions of people from different cultures.

This paper has provided a deeper insight into the associations between right-leaning population and global competence non-cognitive skills, attitudes and values. We argued that that 15-year-olds results in the PISA 2018 assessment of global competence may be affected by a given political-ideological context of the country as reflected in the political-ideological views of the society. The findings of the current study do support the research of Ross (2020) stating, that students’ political socialisation is happening outside of school. It can therefore be assumed that expedient education on cultural heterogeneity, core values of democracy, empathy, and diversity could help support higher students’ global competence.

6. Limitations

In this investigation, there are several sources of limitations. The main limitation is determined by low country participation in the OECD’s PISA 2018 global competence assessment. The global competence assessment had two instruments – a cognitive test and a self-reported student questionnaire. Since only seven EU countries participated in the cognitive test, this study is based on student-self-reporting of global competence only.

Another limitation stems from the fact that the OECD’s global competence framework has a neoliberal bias. Theoreticians using Critical Theory claim that this framework is not measuring how students are ready to live in an interconnected globalized world, but, rather how students are ready to become a dynamic workforce in a globally competitive market society. The conclusions of the present study should be considered minding that global competence is an artificial construct developed by people with certain political and ideological inclinations.

The right-leaning variable is our made-up classification based on respondents’ self-reported placement on the political scale where 0 means political left and 10 means political right. It can introduce bias due to respondents choosing to place themselves at a particular point on the political scale without shared understanding of political left or right principals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Audronė Jakaitienė, Giedrė Blažytė, Julius Žilinskas, Monika Orechova, Rimantas Želvys, Rita Dukynaitė, Saulė Raižienė, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and advice.

Funding

This research is funded by the European Social Fund according to the activity Improvement of researchers’ qualification by implementing world-class R&D projects of Measure No.09.3.3-LMT-K-712. The project No. DOTSUT-39 (09.3.3-LMT-K-712-01-0018) / LSS-250000-57.

Appendix

Table 2. The constructs of global competencies and its statements from students’ questionnaire.

Table 3.

Table 3.

References

Andrews, T. (2021). Bourdieu’s Theory of Practice and the OECD PISA Global Competence Framework. Journal of Research in International Education, 20(2), 154–170.

Ansell BW and Lindvall J (2013). The political origins of primary education systems: ideology, institutions, and interdenominational conflict in an era of nation-building. American Political Science Review 107(3), 505–522.

Apple, M. W. (2013). Educating the right way: Markets, standards, God, and inequality. Routledge.

Asia Society/OECD (2018), Teaching for Global Competence in a Rapidly Changing World, OECD Publishing, Paris/Asia Society, New York, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264289024-en.

Boekaerts, M. (2003). Adolescence in Dutch Culture. International perspectives on adolescence, 3, 99.

Blažytė, G. (2021). Visuomenės nuostatos etninių ir religinių grupių atžvilgiu Lietuvoje | 2021 m [Public attitudes towards ethnic and religious groups in Lithuania, 2021]. https://www.diversitygroup.lt/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Giedres-skaidres.pdf

Blažytė, G., Frėjutė-Rakauskienė, M., & Pilinkaitė-Sotirovič, V. (2020). Policy and media discourses on refugees in Lithuania: shaping the boundaries between host society and refugees. OIKOS: lietuvių migracijos ir diasporos studijos, 1(29), p. 7–30.

Borgonovi, F. (2012). The relationship between education and levels of trust and tolerance in Europe 1. The British Journal of Sociology, 63(1), 146–167.

Carter, E. (2018). Right-wing extremism/radicalism: Reconstructing the concept. Journal of Political ideologies, 23(2), 157–182.

Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., & York, R. L. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Colvin, R. L., & Edwards, V. (2018). Teaching for Global Competence in a Rapidly Changing World. OECD Publishing.

Deimantas, V. J. (2021). Anti-immigrant Attitudes in the European Union: What Role for Values?. Filosofija. Sociologija, 32(4).

Eurydice, European Education and Culture Executive Agency (2020). Equity in school education in Europe: structures, policies and student performance, Publications Office, 2020, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/880217

Fjeldstad, D., J. Lauglo, and R. Mikkelsen. 2010. Demokratisk beredskap. Kortrap- port om norske ungdomsskoleelevers prestasjoner og svar på spørsmål i den internasjonale demokratiuindersøkelsen. Oslo: Enhet for kvantitative utdanning- sanalyser (EKVA), Institute for Teacher Education and School Research, University of Oslo.

Giudici, A. (2021). Seeds of authoritarian opposition: Far-right education politics in post-war Europe. European Educational Research Journal, 20(2), 121–142.

Greenstein F, Herman V, Stradling R, et al. (1974) The child’s conception of the queen and the Prime Minister. British Journal of Political Science 4(3): 257–287.

Grotlüschen, A. (2018). Global competence–Does the new OECD competence domain ignore the global South? Studies in the Education of Adults, 50(2), 185-202.

Hanvey, R. (1982), “An Attainable Global Perspective”, Robert G. Hanvey, Vol. 21/3, pp. 16–167.

Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277.

Inglehart, R.; Norris, P. 2016. Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-nots and Cultural Backlash. HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP16-026.

Knowles, R. T. (2015). Asian values and democratic citizenship: Exploring attitudes among South Korean eighth graders using data from the ICCS Asian Regional Module. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 35(2), 191–212.

Kuang, X., & Kennedy, K. (2018). Hong Kong adolescents’ future civic engagement: do protest activities count? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education.

Lauder, H., Young, M., Daniels, H., Balarin, M., & Lowe, J. (2012). Assessing educational reform: Accountability, standards and the utility of qualifications. In Educating for the Knowledge Economy? (pp. 204–222). Routledge.

Lauglo, J. (2011). Political socialization in the family and young people’s educational achievement and ambition. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(1), 53–74.

Mehta, J. (2013). How paradigms create politics: The transformation of American educational policy, 1980–2001. American Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 285–324.

Mudde, C. (2016). The Study of Populist Radical Right Parties: Towards a Fourth Wave. C-Rex Working Paper Series, No. 1. Center for Research on Extremism, The Extreme Right, Hate Crime and Political Violence, University of Oslo. Available online at: https://www.sv.uio.no/c-rex/english/publications/c-rex-working-paper-series/Cas%20Mudde:%20The%20Study%20of%20Populist%20Radical%20Right%20Parties.pdf

Mudde, Cas. 2019. “The 2019 EU Elections: Moving the Center.” Journal of Democracy 30(4): 20–34.

OECD (2020), PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI): Are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World? PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d5f68679-en.

Piurko, Y., Schwartz, S. H., & Davidov, E. (2011). Basic personal values and the meaning of left-right political orientations in 20 countries. Political Psychology, 32(4), 537–561.

Reimers, F. M. (2013). Assessing global education: An opportunity for the OECD. Online verfügbar unter http://www. oecd. org/pisa/pisaproducts/Global-Competency. pdf, zuletzt geprüft am, 16, 2014.

Reynolds, D., Sammons, P., De Fraine, B., Van Damme, J., Townsend, T., Teddlie, C., & Stringfield, S. (2014). Educational effectiveness research (EER): A state-of-the-art review. School effectiveness and school improvement, 25(2), 197–230.

Robertson, S. L. (2021). Provincializing the OECD-PISA global competences project. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 19(2), 167–182.

Ross, A. (2020). With whom do young Europeans’ discuss their political identities? Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 19(3), 175–191.

Sälzer, C., & Roczen, N. (2018). International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning Assessing global competence in PISA 2018: Challenges and approaches to capturing a complex construct. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 10(1), 6–20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.10.1.02

Scheerens, J. (2016). Educational effectiveness and ineffectiveness. A critical review of the knowledge base, 389.

Sjøberg, S. (2019). The PISA-syndrome–How the OECD has hijacked the way we perceive pupils, schools and education. Confero: Essays on Education, Philosophy and Politics, 7(1), 12–65.

Spring, J. (2015). Globalization of Education: An Introduction. New York: Routledge

UN (2015). Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 11 September 2015. A/RES/69/315 15 September 2015. New York: United Nations.

UNESCO (2015), Decisions adopted by the Executive Board at its 197th session. 197 EX/DECISIONS. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235180

UNHCR, (2021). UNHCR and IOM shocked and dismayed by deaths near Belarus-Poland border. https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/press/2021/9/6149dec74/unhcr-iom-shocked-dismayed-deaths-near-belarus-poland-border.html 21 September 2021

Vaccari, V., & Gardinier, M. P. (2019). Toward one world or many? A comparative analysis of OECD and UNESCO global education policy documents. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning.

Vegetti, F., & Širinić, D. (2019). Left–right categorization and perceptions of party ideologies. Political Behavior, 41(1), 257–280.

Wondreys, J. (2021). The “refugee crisis” and the transformation of the far right and the political mainstream: the extreme case of the Czech Republic. East European Politics, 37(4), 722–746.

Young, M. (2014). Standards and standard setting and the post school curriculum. Perspectives in Education, 32(1), 21–33.

Želvys, R., Dukynaitė, R., & Vaitekaitis, J. (2018). Effectiveness and Eficiency of Educational Systems in a Context of Shifting Educational Paradigms. Pedagogika, 130(2), 32–45.

Želvys, R., Dukynaitė, R., Vaitekaitis, J., & Jakaitienė, A. (2019). School leadership and educational effectiveness: Lithuanian case in comparative perspective. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 24 (Special Issue), 17–36.

Wiesehomeier, N., & Doyle, D. (2012). Attitudes, ideological associations and the left–right divide in Latin America. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 4(1), 3–33.

Ryan, C. (2017). Political Self-Identification and Political Attitudes.

Levitin, T. E., & Miller, W. E. (1979). Ideological interpretations of presidential elections. American Political Science Review, 73, 751–771.

Hofer, M., & Peetsma, T. (2005). Societal values and school motivation. Students’ goals in different life domains. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 203–208.

1 Organization that OECD has teamed up with for the development of global competence assessment framework is Asia Society: https://asiasociety.org/

2 OECD PISA 2018 data website: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/

3 Liberal countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom; Traditional countries: Greece, Ireland, Israel, Poland, Portugal, and Spain; Postcommunist countries: Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia.

4 Question B26. In politics, people sometimes talk of ‘left’ and ‘right’. Using this card, where would you place yourself on this scale, where 0 means the left and 10 means the right?

5 OECD data: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/

7 The percentage of respondents choosing [6 to 10] as self-reported political right in the scale of [0 to 10].