Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2021, vol. 47, pp. 25–38 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2021.47.2

Language Learning Attitudes of Young Learners: Differences between Syrian Refugee Learners and Turkish Learners

Mehmet Asmali

Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University, School of Foreign Languages

E-mail: mehmet.asmali@alanya.edu.tr

Sanem Dilbaz Sayın

Hacı Yılmaz Emine Urhan İmam Hatip Secondary School, Denizli, Turkey

E-mail: sanem1406@hotmail.com

Abstract. Welcoming more than 1.7 million refugee and asylum-seeker children, Turkey has put a considerable effort in turning this tragedy into an advantage for these children in terms of their education. Language teaching has played a remarkable role in this effort. Turkey has offered both Turkish and English language courses to these people. Considering the significance of English as a global language for social integration and future studies, this study attempted to investigate young Syrian refugee students’ attitudes toward English language and their reasons to learn English. Moreover, their perspectives were compared with Turkish young learners. Thirty-eight Turkish and 26 Syrian 5th graders (aged 10–11) voluntarily participated in this study. The findings indicated that learning English makes Syrian students happy, whereas Turkish students enjoy the fun activities in English classes. Learning English is considered both relatively easy and important by both groups. Turkish and Syrian young learners’ reasons to learn English differed slightly. Suggestions were provided for refugee young learners to overcome the potential problems regarding language learning.

Keywords: English, language learning attitude, reasons to learn English, refugees, young learners.

Jaunų besimokančiųjų kalbų mokymosi požiūris: skirtumas tarp besimokančių Sirijos prieglobsčio prašytojų ir besimokančių turkų

Santrauka. Turkija priėmė daugiau nei 1,7 milijono pabėgėlių ir prieglobsčio prašytojų vaikų ir dėjo daug pastangų, kad ši tragedija vaikams virstų jų išsilavinimo privalumu. Svarbus vaidmuo šioje iniciatyvoje tenka kalbų mokymui – Turkija šiems žmonėms siūlo tiek turkų, tiek anglų kalbos kursus. Atsižvelgiant į anglų, kaip globalizacijos kalbos, reikšmę socialinei integracijai ir studijoms ateityje, šiame tyrime analizuojamas Sirijos pabėgėlių moksleivių požiūris į anglų kalbą ir anglų kalbos mokymosi priežastys. Be to, jų nuostatos lyginamos su turkų moksleivių nuostatomis. Tyrime savanoriškai dalyvavo trisdešimt aštuoni penktų klasių (10–11 metų) moksleiviai iš Turkijos ir dvidešimt šeši moksleiviai iš Sirijos. Rezultatai atskleidė, kad pats anglų kalbos mokymasis sirų vaikams teikia daug džiaugsmo, o turkų moksleiviams anglų kalbos pamokose labiausiai patinka smagūs užsiėmimai. Abiem grupėms mokytis anglų kalbos atrodo gana lengva ir kartu svarbu. Šiek tiek skiriasi turkų ir sirų moksleivių pateikiamos priežastys mokytis anglų kalbos. Tyrime taip pat pateikiama siūlymų, kaip pabėgėliams moksleiviams įveikti galimus kalbų mokymosi sunkumus.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: anglų kalba, požiūris į kalbos mokymąsi, priežastys mokytis anglų kalbos, pabėgėliai.

_________

Received: 26/07/2020. Accepted: 20/06/2021

Copyright © Mehmet Asmali, Hacı Yılmaz, 2021. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The refugee crisis has been among the major recent issues dominating political debates in today’s world (Savaşkan, 2019). It is still a considerable problem, since 27.5 million new people were forcibly displaced from their homes from 2009 to 2018, reaching a total of 70.8 million people around the world (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2019). Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Turkey, a country with the largest refugee population in the world (United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 2019), has been a transit country for refugees and migrants on the move. Hosting over 1.7 million refugee and asylum-seeker children, a total of over four million with their family members (UNICEF, 2019), Turkey has put a considerable effort in turning this tragedy into an advantage for these children in terms of their education by making it one of the country’s major concerns.

Despite the best efforts of Turkey in increasing the number of Syrian refugee children that receive formal education to 684 253, 400 000 of them are still out of school (Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan, 2020). However, the remarkable increase in the overall enrollment rate of the refugee students from 30% in 2014 to 63% in 2017 is also an undeniable success (Ombudsman Institution of the Republic of Turkey, 2018). The statistics provided by the same institution indicated that the enrollment rate is rather high in primary school (98%) compared to middle school (53%) and high school (23%). Considering the low school enrollment, especially in the upper levels, and the decreasing hopes of returning these refugee children to their home country, the need to take serious steps in order to meet their vital educational needs, as well as such basic needs as food and safety, has emerged (Soylu, Kaysılı & Sever, 2020).

In order to meet their educational needs and accelerate the social integration of a huge number of refugee students, language may be thought to be one of the main elements of this process. Therefore, Turkish language courses are offered both to these learners and their families (Savaşkan, 2019). However, in this acculturation process, not only the home country language but also additional languages matter since they bolster social integration, provide new job and education opportunities, and let children express their concerns in various contexts. Considering the future of these students, English as a global language is of vital importance as well. Refugees have already reported the increasing need of English that plays a role in giving an international voice for them both in and outside of Turkey. An increasing demand for English among the refugees is not surprising, because stakeholders working on the Syrian border and those working for a future Syria have already recognized English as a lingua franca, which makes it more important than ever due to the increased contact with the international community (British Council, 2018).

It does not seem to be possible for refugees to return to their country in the near future (Culbertson & Constant, 2015), which makes children’s language learning significant, as their school enrollment is higher and they are considered to be their own country’s future. Additionally, as most of the young children suffer from severe trauma due to displacement and losing their family members, language learning may relieve their distress through creative activities, games, storytelling, and other activities (British Council, 2018). However, young learners’ attitudes and reasons to learn English have been reported to be essential components of learning English (Arda & Doyran, 2017; Asmalı, 2017a; Juriševič & Pižorn, 2013; Sougari & Hovhannisyan, 2013; Yolageldili & Arıkan, 2011). Although these significant aspects of language learning have been investigated in the context of Turkish young learners and teenagers (Arda & Doyran, 2017; Asmalı, 2017a; Kızıltan & Atlı, 2013; Maviş & Bedir, 2015), young refugee students’ perspectives as well as their comparison with those of Turkish young learners have been neglected. Considering this gap, this study tries to analyze the attitudes of Turkish and Syrian refugee young learners, and their reasons to learn English. In line with this aim, the following research questions were answered:

1. Are there any differences between Turkish and Syrian refugee young learners’ attitudes towards learning English?

2. Are there any differences between Turkish and Syrian refugee young learners’ reasons to learning English?

Literature review

Young learners

Considering their needs, expectations, and learning styles, young learners have been reported to be different from adult learners (İnci-Kavak, 2019). Their performance in foreign language learning is also considered as more successful compared to adults (Kızıltan & Atlı, 2013). This difference may stem from their physically being more involved with seeing, hearing, touching, and interacting in language classes (Harmer, 2007). Apart from this fact, young learners were observed to develop more positive attitudes toward foreign language learning compared to older age groups (Loukotková, 2011). Considering the significant impact of positive attitudes on learning a new language (Gardner, 1985), it becomes more important to examine the language learning attitudes of young learners.

Several researchers have attempted to reveal young learners’ attitudes toward foreign language learning. The findings of the study by Uluçaylı (2012) indicated that Turkish students had positive attitudes towards English. Their reasons to learn English were listed as finding a good job, communicating with native speakers, playing games, and visiting foreign countries. In another study conducted with Turkish young learners, Arda and Doyran (2017) compared the attitudes of young learners and teenagers toward English language learning. They reported that young learners demonstrated more positive attitudes. Learning English was considered as fun, colorful, and interesting. Young learners also loved their English teachers and the class. Young learners’ attitudes toward English were also investigated by Kızıltan and Atlı (2013). Fourth graders were reported to develop positive attitudes toward English language skills, textbooks, and activities. In the Turkish context, Asmalı (2017a) also found that second-grade students had positive attitudes toward English. While singing and playing games were found to be learners’ favorite activities in English classes, the attitudes of parents, teachers, and a positive learning atmosphere and activities were claimed to be the important factors determining the attitudes of second graders.

Among the studies conducted in international contexts, Sougari and Hovhannisyan (2013) compared Greek and Armenian young learners’ attitudes and motivation to learn English. Greek learners demonstrated more positive attitudes and instrumental motivation, whereas Armenian young learners’ main aims to learn English were international job opportunities, knowledge growth, and international communication. In a recent study, Wallace and Leong (2020) investigated sixth-grade Chinese learners’ attitudes and purposes to learn English. Their findings indicated a high level of motivation. Games and songs were students’ favorite activities. The learning environment, a positive relationship with the teacher, and learning activity types were found to be the important factors determining learners’ perspectives.

It is obvious that most young learners in different contexts demonstrate positive attitudes towards English language learning. Their reasons to learn English show some slight differences. However, young learners who have been through extraordinary situations like refugees may have different perspectives regarding their attitudes and reasons to learn English.

Refugee learners

The refugee exodus after the Syrian civil war has dramatically changed the life of not only the refugees but also that of people in host countries. Being home to over 1.7 million refugee children (UNICEF, 2019), Turkey has been a safe shelter for many young refugee learners. As the number of young learners increased, the education of these children started to gain more attention (Asmalı, 2017b).

In line with this fact, refugee students’ problems have been investigated from different perspectives in the related literature. Gömleksiz and Aslan (2018) investigated the problems refugee students face in public schools in Turkey. Their findings indicated various problems, such as the language of instruction, course content, lack of family support, unfamiliarity with the teachers’ techniques and school rules. The problems faced by Turkish teachers teaching refugee students were also examined (Taşkın & Erdemli, 2018). The language barrier, cultural differences between the teachers and students, and some discipline-related problems were specified as the most significant problems. Schooling experiences of refugee students from the perspective of teachers showed that refugee students have stress disorders and problems with understanding the content in the class (Tösten, Toprak & Kayan, 2017). Studies investigating options to eliminate these problems determined non-formal education activities as a strategy to cope with language and socialization problems for refugee learners (Küçüksüleymanoğlu, 2018).

A small number of studies have dealt with the language learning experiences of refugee students. In one of them, Savaşkan, (2019) investigated the perspectives of teachers in order to illustrate teaching Turkish to refugee students. Asmalı (2017b) explored the perspectives of Turkish EFL teachers regarding refugee students studying in public schools. The main problems faced were reported to be lack of a common language and suitable materials, varying English proficiency levels in the same class as well as the discrepancy of the EFL program followed by the refugee learners’ previous language skills. Moreover, two studies that were conducted in Jordan regarding Syrian refugee students’ language learning problems indicated interesting results. In one of them, Alefesha and Al-Jamal (2019) investigated refugee learners’ problems with regard to learning English through taking views of several stakeholders. In addition to economic problems, a poor educational background, a lack of motivation, the Jordanian teachers’ inability to work with refugees, and discomfort with the English language were found as the main problems. Alkhawaldeh (2018), on the other hand, investigating teachers and parents’ perspectives regarding the instructional challenges Syrian refugee students have, reported that English learning is found challenging by these learners. Refugee students were claimed to be careless and uninterested in learning English. Furthermore, the dominance of French in the Syrian educational system contradicted with that of English in the Jordanian system, which resulted in less positive attitudes towards reading and writing in English.

Studies have shown that several problems are being experienced by refugee students in host countries in their schooling experiences. However, despite the abundancy of studies dealing with the general educational problems they are facing, their English language learning, which may be significant for their future life, has been neglected. Considering this fact, this study aims to investigate the attitudes of Syrian refugee students studying in a Turkish public school toward English language. Their reasons to learn English, as well as a comparison with young learners from the host country (Turkey), are among the purposes of the present study.

Methodology

Employing a quantitative methodology, this study attempted to find out Turkish and Syrian young learners’ attitudes toward foreign language learning and their reasons to learn a foreign language by collecting survey data. Considering the purpose of the present study, a questionnaire, one of the most popular research instruments applied in the social sciences (Dörnyei, 2007), has been used to describe their attitudes and reasons.

Participants and setting

The participants were 38 Turkish (16 girls, 22 boys) and 26 Syrian refugee students (18 girls, 8 boys) with a total of 64 young learners (aged 10–11) studying in a public secondary school in the 5th grade. Syrian students and Turkish students study English for three hours (40 minutes each) in two different classes separately. Turkish students start learning English at the age of 7–8 (2nd grade), whereas no certain information can be stated for Syrians due to the unstable situation in their home country. However, 12 out of 26 refugee students started primary school in Turkey, which means that they also started learning English in the 2nd grade. The same English teacher has been teaching in both classes since the beginning of the 5th grade. Most of these students in both Turkish (61%) and Syrian groups (92.3%) have never spoken English out of school.

Data collection and analysis

The instrument that was used to gather data from young learners was a combination of the ones that were used in studies to investigate the foreign language learning attitudes of young learners (Asmalı, 2017a; Juriševič & Pižorn, 2013) and their reasons to learn English (Akçay, Bütüner-Ferzan & Arıkan, 2015). Closed-ended questions used in the study of Juriševič and Pižorn (2013) for Slovenian young learners and items used in the study by Asmalı (2017a) for Turkish young learners were revised and adapted in the present study to examine the learners’ attitudes. In addition, interview questions used in the study by Akçay et al. (2015) were transformed into a questionnaire format to investigate the young learners’ reasons to learn English.

Students’ age, class, and gender comprised the biographical information section of the questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions. Four attitude-related items were presented in a four-point Likert scale ranging from one star (meaning strong disagreement) to four stars (strong agreement). Syrian students were also asked to specify three additional Likert-type items potentially indicating their Turkish language skills and its help in learning English. Out of the 15 questions, 11 were in the format of multiple-choice. The language used in the questionnaire was Turkish.

An expert in the field of education, who has experience in teaching English to both Turkish and Syrian refugee young learners, was consulted prior to piloting the questionnaire. The questionnaire was pilot tested with the participation of a total of 10 students with an equal number of participants from both groups. Syrian students were accompanied by a teacher speaking their mother tongue both during the pilot study and the main study. Expert opinions and students’ views were collected, and necessary modifications have been made accordingly.

After informing the parents of the students about the study, the data were gathered during the students’ regular English classes in 40 minutes. The questionnaires were filled in by the students individually. The data were analyzed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics including frequencies, percentages, and mean scores were used during the data analysis process. Moreover, a Mann-Whitney U test was performed to examine the differences between Turkish and Syrian refugee students’ attitudes toward learning English, as the data were not normally distributed with a skewness of -1.225 (SE = .299) and kurtosis of 3.281 (SE = .590).

Findings

The findings will be revealed under two subsections: learners’ attitudes towards English and their reasons to learn English.

Students’ attitudes towards English

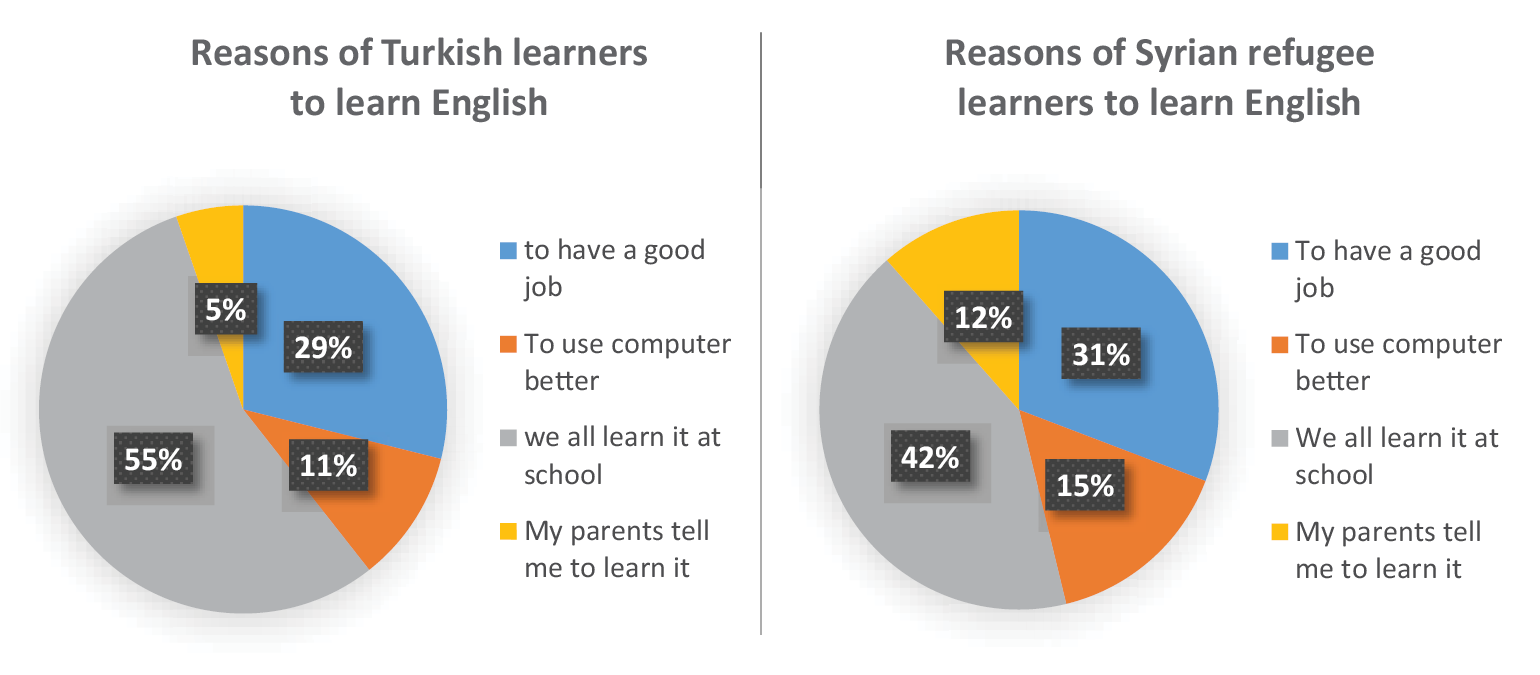

First, students’ choice of favorite school subjects indicated that only 11.5% of Syrian students’ and 18.4% of Turkish students’ favorite school subject was English. Mathematics was found to be the dominating favorite school subject of Syrian and Turkish students with 42.3% and 52.6%, respectively. Second, the students were also asked the reason why they like English classes. The responses are presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The reasons why Turkish and Syrian students like English

It is obvious that Turkish students enjoy English classes more and they consider themselves good at it. However, it makes refugee students happier. Moreover, the students’ perspectives regarding their favorite activities in English classes showed a significant difference between the two groups. While the majority of Turkish young learners favored playing vocabulary games (42%), it was singing English songs for Syrians (65%). Both groups disliked reading and vocabulary activities requiring writing. The least favorite and most difficult activity in English classes named was reading, both for Turkish (29%) and Syrian (46%) students, which was followed by dialogues (28% for Turkish and 16% for Syrians).

As for the students’ attitudes provided in a four-point Likert type, the difference between Turkish and Syrian refugee students is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Turkish and Syrian students’ attitudes towards English

|

Attitudes

|

Turkish

|

Syrian

|

|

M

|

SD

|

M

|

SD

|

|

The activities in our textbook are suitable for our interest and skills

|

3.00

|

1.06

|

3.88

|

.43

|

|

Learning English is difficult

|

2.58

|

1.00

|

2.69

|

1.37

|

|

Learning English is important

|

3.68

|

.61

|

3.50

|

.94

|

|

My parents say that learning English is important

|

3.05

|

1.27

|

2.46

|

1.30

|

With reference to the questionnaire items related to learners’ attitudes toward learning English, the results yielded that Turkish and Syrian refugee students exhibited markedly different attitudinal opinions regarding the activities in their textbook and their parents’ views concerning the importance of English. Syrian students find the activities in their textbook more interesting and convenient for themselves compared to Turkish students, whereas Turkish parents state the importance of learning English significantly more than Syrian parents. Additionally, the vast majority of the students in both groups agree on the importance of English and they find it relatively easy. Moreover, a Mann-Whitney U test was run both for the attitudes of the participants as a whole and for each item. The results indicated no statistically significant difference between the English language learning attitudes of Turkish (Mdn = 3.25) and Syrian learners (Mdn = 3) as a whole, U(NTurkish = 38, NSyrian = 26) = 489.5, z = -.062, p = .95. However, the only item that indicated a statistically significant difference between the two groups was the one showing the participants’ views concerning the suitability of the activities in their textbook for their interest and skills. The results indicated that the activities in their textbook were found significantly more suitable for their interest and skills by the Syrian learners (Mdn = 4) than Turkish learners (Mdn = 3), U(NTurkish = 38, NSyrian = 26) = 254.5, z = -3.831, p = .000. Furthermore, Syrian students were asked about their Turkish proficiency and to what extent it helps them to learn English. The results showed that 61.5% of Syrian refugee students have no problem in reading and writing in Turkish, whereas the ratio decreases to 46.2 in speaking Turkish. The number of refugee students indicating serious reading, writing, and speaking problems in Turkish is below 23%. Surprisingly, a majority of the refugee students (42.3%) think that Turkish language skills do not help them learn English.

Students’ reasons to learn English

Regarding students’ reasons to learn English, the first issue that was investigated was the students’ perspectives about where they can use English now. The findings revealed that Turkish students think about using English primarily for communication with tourists (40%), whereas refugee young learners use it for watching cartoons, series, and videos on YouTube in English (54%). The statistics also showed that Turkish students (58%) demonstrated a greater desire to visit other countries than Syrian students did (42%) as an answer for the question of where and why they can possibly use English when they grow up. For the same question, Turkish students indicated their wish to be more educated with the help of English (24%), whereas refugee students thought to use English to find a job (19%) and to make better use of computers (19%).

The students were also asked to indicate where they would like to live and the countries they would like to visit when they grow up, which may be related to their willingness to learn English. The results revealed that 85% of Turkish young learners want to live in Turkey in the future, whereas this rate is only 57% for Syrian students. However, the rate of those who plan to go back to their own country does not exceed 27%. Interestingly, France was found to be the most desired country to visit, followed by Germany and Canada, for both groups.

Another aspect that may be a reason for students to learn English is the knowledge of English among family members. A huge gap can be observed between Turkish and Syrian students with reference to this question. While the percentage of students whose family members had no contact with English was 69% for Syrian refugee learners, it was only 7% for Turkish students. Turkish students’ siblings were found to be active users of English language (68%).

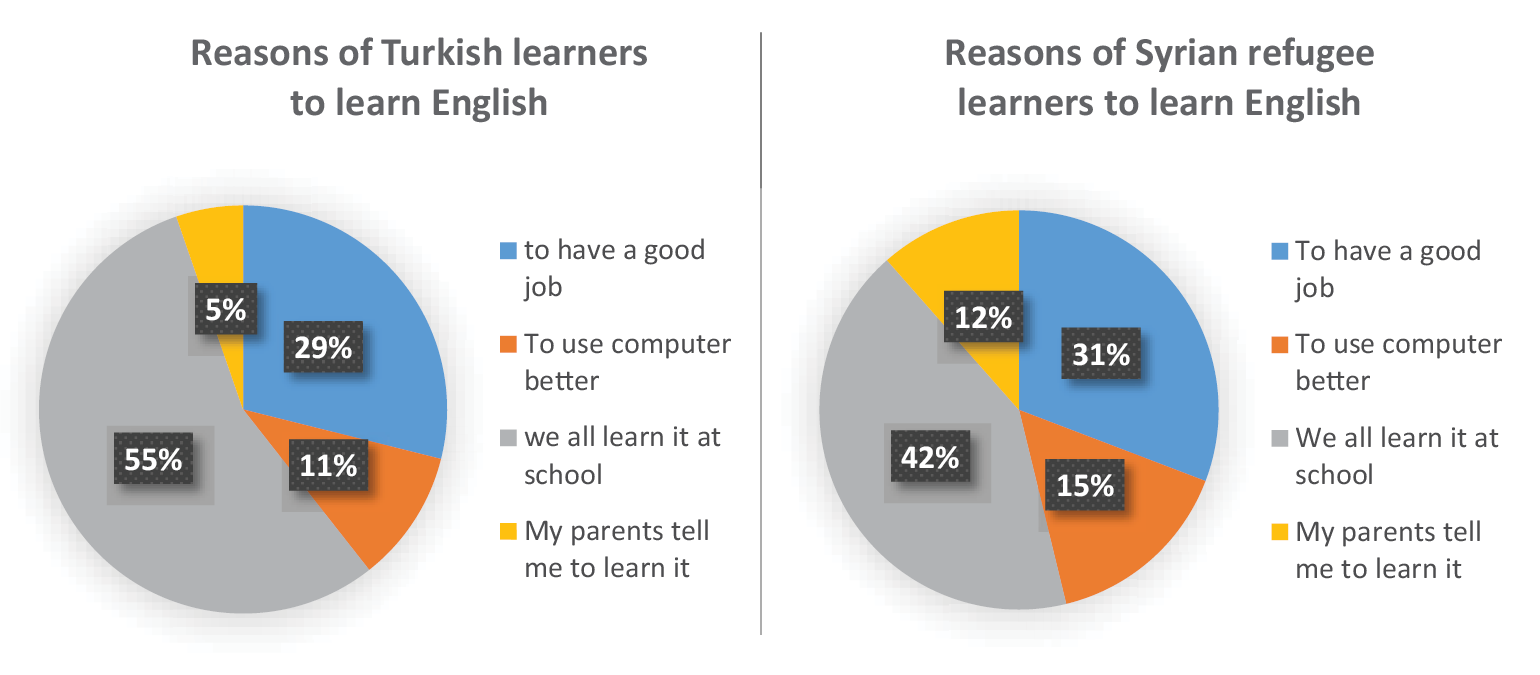

The main reason for learning English for both groups was the fact that they all learn it at school. Following this, to have a good job was preferred by the students in both groups as the second most important reason to learn English. Statistics for learning English just to satisfy parents’ needs and to use computers more efficiently, such as watching videos or playing games, are slightly higher for Syrian refugee learners compared to Turkish learners.

Figure 2. Reasons of Turkish and Syrian young learners to learn English

Surprisingly, when students were asked to choose a foreign language other than English to learn, a majority of the Turkish (31%) and Syrian (45%) students claimed no other foreign language. Moreover, while German, Russian, and French were equally preferred as the second foreign language by Turkish students (23% for each), French was the leading second foreign language for Syrian young learners (24%).

Discussion

This study attempted to reveal Turkish and Syrian young learners’ attitudes towards learning English as well as their reasons to learn English. As for students’ attitudes towards English classes, English was not even chosen as the students’ second favorite course in both groups. Mathematics was both Syrian and Turkish young students’ favorite school subject, as it was the case for young learners in the related literature (Asmalı, 2017a). This shows that English does not take their attention as much compared to other classes, such as mathematics and arts. Turkish students feel slightly more self-confident in English compared to Syrian refugee learners as stated for the reasons why they like English classes. However, the learners in both groups agreed on the first reason and asserted the idea that the activities in English classes are fun. The results are in line with those of Kızıltan and Atlı (2013) as the young learners had fun and developed positive attitudes towards English, especially in writing, art, and crafting activities in their study. The only reason why Syrian young learners scored higher is English classes being a source of joy and happiness for them. This may coincide with post-traumatic stress disorders affecting many Syrian refugee students (Tösten et al., 2017), as they may try to overcome trauma with the help of activities in English classes.

The findings also indicated a difference regarding Turkish and Syrian students’ favorite activities in English classes. Turkish students enjoyed vocabulary games most, whereas refugee students liked singing in English classes. Although not in English classes, refugee students’ pleasure of learning and singing songs could also be seen in the schooling experiences of refugees in Turkey learning Turkish (Erden, 2017). On the other hand, playing games in English classes has always been the most enjoyable activity for Turkish young learners (Asmalı, 2017a).

Reading, on the other hand, has been chosen as the most difficult activity by Turkish and Syrian students, the rate being much higher among refugee young learners. It is not surprising for the refugee students since reading and writing have been found to be among the main reasons of their complaints in the literature (Gömleksiz & Aslan, 2018). Moreover, considering their mother tongue, Arabic, students may take more time to get acquainted with the Latin alphabet and perform better in reading and writing activities (Alefesha & Al-Jamal, 2019).

There were two other items on which Turkish and Syrian refugee young learners’ views differed significantly. First, Syrian students were found to be more satisfied with their textbooks compared to Turkish learners. The results of one of the rarest studies investigating Syrian refugee students’ challenges and problems in learning English in Jordan, which, like Turkey, is a country hosting large numbers of refugees, contradict with the results of the present study with reference to textbooks in English classes (Alefesha & Al-Jamal, 2019). The participants of the study of Alefesha and Al-Jamal (2019) were adults, yet the unfamiliarity with the language used in the textbooks made it difficult for them to understand and created dissatisfaction. Second, Turkish young learners’ parents emphasized the significance of learning English more than the parents of refugee learners. Despite refugee parents’ awareness of the importance of education for their children’s future (Gömleksiz & Aslan, 2018), this may be related to a lack of high qualifications among them (Alkhawaldeh, 2018). The students’ attitude toward English was also represented in their responses regarding how important and difficult it is for them. The majority of the young learners in both groups reported that learning English is quite easy for them, which is also supported by younger Slovenian students (Juriševič & Pižorn, 2013) and Turkish young learners (Asmalı, 2017a).

Considering young learners’ reasons to learn English, the first discrepancy was found in their perspectives regarding where to use English. Turkish students are inclined to use English in communicating with tourists, whereas Syrian refugee students use it for entertainment, such as videos, cartoons, and songs. As for Turkish young learners’ reasons, the findings are in accordance with those of Akçay et al. (2015). In their study with Turkish young learners aged 11–12, they also found communication with foreigners and tourists as the leading reasons to learn English. The learners from this perspective are considered as intrinsically motivated to learn English as their purpose is to communicate in English. However, Turkish and Syrian refugee students agreed on the potential use of English while visiting other countries when they grow up, which is in line with the findings of Uluçaylı (2012), who also investigated the attitudes and motivations of young learners to learn English. Another considerable difference was observed in the responses of the learners for the country where they would like to live in the future. A majority of Turkish young learners want to live in Turkey, whereas only almost half of Syrian students desire to continue living in Turkey, and one-fourth of them are determined to go back to their country in the future. One reason for their dissatisfaction with living in Turkey may be related to the results of the study of Tösten et al. (2017) indicating social and emotional polarization in some regions they live in, creating problems in meeting their needs and social injustices eventually aggregating the feelings of isolation. This may also be understood from the results presenting Turkish parents’ claims, showing that Turkish students are less valued compared to Syrian students. Considering the fact that these Syrian refugee students will have the potential of becoming either Turkey’s social capital or social problem, in order not to have a lost generation, educational steps should be taken to help these learners develop the feeling of integration and sense of belonging (Küçüksüleymanoğlu, 2018).

Another remarkable difference among young learners came into the picture in terms of their parents’ contact with the English language. The majority of Syrian students claimed that their parents had no contact with English, whereas this rate was just 7% in Turkish group. First, it is claimed that refugee children learn the home country’s language and cultural skills faster compared to their parents (Işık-Ercan, 2012). On the other hand, considering the positive correlation between refugee parents’ educational backgrounds and the academic success of their children (Mullen, 2014), it is inevitable that refugee students’ attitudes and motivation toward learning English will be affected by their parents (Ahmed, 1989). Hence, refugee students’ hardship in learning English and relatively more negative attitudes towards English may be attributable to their parents’ lack of background in English.

Students’ direct responses for the reason of learning English showed similarity in both groups. The majority of the students in both groups claimed that they learn English just because it is a school subject, the ratio being higher in the Turkish group. In a similar study, Slovenian young learners’ claims indicated that they learn it to speak, watch cartoons, and read books, while learning English just because it is a school subject was the least important reason (Juriševič & Pižorn, 2013). Turkish participants’ responses in the present study for the reason of learning English also contradicted those of the previous studies, including those discussing Turkish young learners (Akçay et al., 2015; Asmalı, 2017a).

As a final remark, Syrian students’ lack of Turkish proficiency as a problem to be overcome has been mentioned in several studies demonstrating the problems that refugee students face in Turkey (Asmalı, 2017b; Küçüksüleymanoğlu, 2018; Taşkın & Erdemli, 2018; Tösten et al., 2017). It is interesting that most Syrian young learners did not find Turkish language skills helpful for their English learning, which contrasts with the views of some teachers of English to young learners, positing the significance of L1, Turkish in this case, as a factor affecting young learners’ readiness to learn a foreign language (Gürsoy, Korkmaz & Damar, 2013).

Conclusion

The results indicated both similarities and differences between Turkish and Syrian young learners’ attitudes toward learning English and their reasons to learn English. Beyond the differences between the two groups, with respect to the reason to learn English, students should be encouraged to learn English as a way to enjoy learning a new language rather than it being an obligation at school. The students’ horizons may be broadened in terms of English use to a change in their perspectives. Moreover, considering the responses of the refugee students, the feeling of belonging should be developed in these learners through formal and informal activities (Küçüksüleymanoğlu, 2018). Another major problem was refugees’ coming to Turkey at a relatively high educational disadvantage, since one-third of Syrians were illiterate and another 13% were literate without a school degree (Erdoğan & Erdoğan, 2018). Given that parents’ have a significant impact on the learning developments of their children (Mullen, 2014), education provided by the government should not only be limited to those students who regularly attend public schools.

Regarding students’ attitudes toward learning English, although English is thought to be quite easy, Syrian students reported that they had problems with written activities, but they enjoyed singing the most. Therefore, more verbal activities can take place in English classes in public schools where just refugee students are taught.

Finally, the results of this small-scale study are limited in its scope, as the shared responses are only of Turkish learners and Syrian refugee learners aged 10–11 studying at a public school in separate classes in the western part of Turkey. A small sample and lack of in-depth data can be listed among the limitations as well. A more comprehensive, nationwide study may involve several stakeholders’ perspectives regarding young learners’ attitudes towards English and their reasons of learning English. A combination of personal interviews with the young learners and picture-drawing tasks may be helpful to delve into the perspectives of young learners regarding language learning.

References

Ahmed, H. (1989). The role of attitudes and motivation in teaching and learning foreign languages. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Stirling, Scotland, UK). Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/47ce/b9ae43a48ccd62230e2ac917bc049aaa5958.pdf

Akçay, A., Bütüner-Ferzan, T., & Arıkan, A. (2015). Reasons behind young learners’ learning of foreign languages. International Journal of Language Academy, 3(2), 56–58. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED576678.pdf

Alefesha, M. N. H., & Al-Jamal, A. H. D. (2019). Syrian refugees’ challenges and problems of learning and teaching English as a foreign language (EFL): Jordan as an example. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 6(1), 117–129. Retrieved from: http://www.ejecs.org/index.php/JECS/article/view/235

Alkhawaldeh, A. (2018). Syrian refugees’ children instructional challenges and solutions in Jordan: Teachers’ and parents’ perspectives. Border Crossing, 8(2), 311 – 331. Doi: https://doi.org/10.33182/bc.v8i2.448

Arda, S., & Doyran, F. (2017). Analysis of young learners’ and teenagers’ attitudes to English language learning. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 9(2), 179–197. Retrieved From: http://ijci.wcci-international.org/index.php/IJCI/article/view/81

Asmalı, M. (2017a). Young learners’ attitudes and motivation to learn English. Novitas- ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language, 11(1), 53–68. Retrieved from: http://www.novitasroyal.org/Vol_11_1/asmali.pdf

Asmalı, M. (2017b). Effort to create hope for ‘lost generation’: Perspectives of Turkish EFL teachers. Studies of Foreign Languages, 31, 102–112. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5755/j01.sal.0.31.19078

British Council (2018). Language for resilience: The role of language in enhancing the resilience of Syrian refugees and host communities. Retrieved from: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/language_for_resilience_report.pdf

Culbertson, S., & Constant, L., 2015. Education of Syrian refugee children: Managing the crisis in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan. Santa Monica: RAND corporation [online]. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR859.readonline.html

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in Applied Linguistics. Oxford, NY: OUP.

Erden, Ö. (2017). Schooling experience of Syrian child refugees in Turkey (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Indiana University, Indiana, the USA). Retrieved from: https://search.proquest.com/openview/c31431c353c4f9ab113d4265efe25173/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Erdoğan, A., & Erdoğan, M. M. (2018) Access, qualifications and social dimension of Syrian refugee students in Turkish higher education. In: Curaj, A., Deca, L., Pricopie, R. (Eds) European higher education area: The impact of past and future policies (pp. 259–276). Springer, Cham, Switzerland.

Gardner, R. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning. London: Edward Arnold.

Gömleksiz, M. N., & Aslan, S. (2018). Refugee students’ views about the problems they face at schools in Turkey. Education Reform Journal, 3(1), 45–58. Retrieved From: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED586389.pdf

Gürsoy, E., Korkmaz, S. Ç., & Damar, A. E. (2013). Foreign language teaching within 4+4+4 education system in Turkey: Language teachers’ voice. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 53/A, 59–74. Retrieved from: http://ejer.com.tr/public/assets/catalogs/0527491001578658390.pdf

Harmer, J., (2007). How to teach English. Harlow. Pearson Education Limited.

Isık-Ercan, Z. (2012). In pursuit of a new perspective in the education of children of the refugees: Advocacy for the “family”. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12(4), 3025–3038. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1002997.pdf

İnci-Kavak, V. (2019). Teaching English to young learners in a British multilingual classroom. Cumhuriyet International Journal of Education, 8(3), 609–634. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.30703/cije.518963

Juriševič, M., & Pižorn, K. (2013). Young foreign language learners’ motivation – A Slovenian experience. Porta Linguarum, 19, 179–198. Retrieved from: https://www.ugr.es/~portalin/articulos/PL_numero19/12%20%20Mojca.pdf

Kızıltan, N., & Atlı, I., (2013). Turkish young language learners’ attitudes towards English. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 28(2), 266–278. Retrieved from: http://www.efdergi.hacettepe.edu.tr/yonetim/icerik/makaleler/181-published.pdf

Küçüksüleymanoğlu, R. (2018). Integration of Syrian refugees and Turkish students by non-formal education activities. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 7(3), 244–252. Doi: 10.11591/ijere.v7.i3.14118

Loukotková, E., (2011). Young learners and teenagers – analysis of their attitudes to English language learning. (Diploma thesis – Masaryk University, Brno, Czechia). Retrieved from: https://is.muni.cz/th/vmfsn/Loukotkova_Diploma_Thesis.pdf

Maviş, Ö. F., & Bedir, G. (2015). 2nd year students’ and their teacher’s perspectives on English language program applied for the first time in 2012–2013 academic year. International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications, 4, 205–215. Retrieved from: http://www.ijonte.org/FileUpload/ks63207/File/18a..mavis.pdf

Mullen, K. (2014). A holistic approach to promoting student engagement: Case studies of six refugee students in upper elementary. (Unpublished Master’s thesis, Bosie State University, Bosie, Idaho). Retrieved from: https://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1823&context=td

Ombudsman Institution of the Republic of Turkey (2018). English version of the special report on Syrians in Turkey. Retrieved From: https://www.ombudsman.gov.tr/syrians/report.html#p=4

Regional Refugee & Resilience Plan (2020). Regional refugee and resilience plan in response to the Syria crisis. Retrieved from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/74179

Savaşkan, M. (2019). Teaching Turkish to Syrian refugee students: Teacher perceptions. (Unpublished Master’s thesis, İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey). Retrieved from: http://repository.bilkent.edu.tr/handle/11693/52319

Sougari, A. M., & Hovhannisyan, I. (2013). Delving into young learners’ attitudes and motivation to learn English: Comparing the Armenian and the Greek classroom. Research Papers in Language Teaching and Learning, 1, 120–137.

Soylu, A., Kaysılı, A., & Sever, M. (2020). Refugee children and adaptation to school: An analysis through cultural responsivities of the teachers. Education and Science, 45(201), 313–334. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15390/EB.2020.8274

Taşkın, P., & Erdemli, Ö. (2018). Education for Syrian refugees: Problems faced by teachers in Turkey. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 75, 155–178. Doi: 10.14689/ejer.2018.75.9

Tösten, R., Toprak, M., & Kayan, S. M. (2017). An investigation of forcibly migrated Syrian refugee students at Turkish public schools. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 5(7), 1149–1160. Doi: 10.13189/ujer.2017.050709

Uluçaylı, E. (2012). Attitudes, motivation and anxiety of young EFL learners. (Unpublished masters’ thesis, Eastern Mediterranean University, Gazimağusa, North Cyprus). Retrieved from: http://i-rep.emu.edu.tr:8080/jspui/handle/11129/1848

United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF] (2019). Turkey humanitarian situation report. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/turkey/media/7091/file/UNICEF%20Turkey%20Humanitarian%20Situation%20Report%20-%20Jan-March%202019.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR] (2019). Global trends Forced Displacement in 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.unhcr.org/5d08d7ee7.pdf

Wallace, M. P., & Leong, E. I. L. (2020). Exploring language learning motivation among primary EFL learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 11(2), 221–230. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1102.10

Yolageldili, G., & Arıkan, A. (2011). Effectiveness of using games in teaching grammar to young learners. Elementary Education Online, 10(1), 219–229. Retrieved from: http://ilkogretim-online.org.tr/index.php/io/article/view/1668/1504