Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2023, vol. 50, pp. 70–87 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2023.50.5

Historical, Curricular and Conceptual Evolution of School Physical Education: A Spanish View

Pedro José Carrillo-López

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0063-7645

Teacher at the Consejería de Educación, Juventud y Deportes de Canarias, Spain

pj.carrillolopez@um.es

Andrés Rosa-Guillamón

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5679-0986

University of Murcia, Spain

andres.rosa@um.es

Eliseo García-Cantó

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6845-6835

University of Murcia, Spain

eliseo.garcia@um.es

Abstract. Current school Physical Education is the evolutionary result of a diversity of social, educational, economic, cultural, religious and military developments following transformations since primitive societies. Analysing its historical, curricular and conceptual evolution is essential for teachers, providing them with a historical basis for reflection of the challenges facing school Physical Education in the 21st century. From this analysis it can be seen that we find ourselves in a current reality with different objectives from the era that preceded it. Once the challenge of offering an education for all at the end of the 20th century has been overcome, it is necessary to carry out didactic approaches adjusted to the needs of the students; consequently, they will be aware of maintaining a progressive responsibility and autonomy in the care of their body; physically and psychologically stimulating their motor development and cognitive capacity. In this way, a didactic transposition of the learning learnt at school to its application in real life will be generated, and more specifically so that Spanish pupils will be at the same level as the European average in a future that looks very competitive. Faced with this scenario, the ever-decreasing demands placed on students, where it is increasingly easier to pass without effort, simply to eliminate failure, logically leads to a student body that is analogue, uncritical and often lacking in enthusiasm for learning. For this reason, Physical Education teachers must shed light on this situation by giving critical intentionality to their pedagogical approaches.

Keywords: Physical Education, epistemology, schoolchildren, health, motor skills.

Istorinė ir konceptuali kūno kultūros ugdymo turinio mokykloje raida: ispaniškasis požiūris

Santrauka. Kūno kultūros ugdymą mokykloje formavo socialiniai, švietimo, ekonominiai, kultūriniai, religiniai ir kariniai pokyčiai, kurie iškilo po pirmykščių visuomenių transformacijų. Mokytojams labai svarbu analizuoti kūno kultūros raidą – tiek istorinę, tiek ugdymo turinio, tiek konceptualią, nes tai suteikia istorinį pagrindą refleksijai apie kūno kultūros iššūkius XXI a. mokykloje. Mūsų analizė atskleidė, kad dabartinės realybės tikslai skiriasi nuo ankstesnių laikotarpių. Įveikus XX a. pabaigos iššūkį padaryti išsilavinimą prieinamą visiems, svarbu naudoti mokinių poreikius atitinkančius didaktinius metodus, kad mokiniai žinotų, kaip prisiimti vis didėjančią atsakomybę, ir taptų savarankiški rūpindamiesi savo kūnu fiziškai ir psichologiškai, kaip skatinti savo motorinius ir kognityvinius gebėjimus. Tokiu būdu bus pasiektas didaktinis mokykloje išmoktų dalykų perkėlimas ir pritaikymas realiame gyvenime, o tiksliau, Ispanijos mokiniai savo lygiu neatsiliks nuo Europos, kuri atrodo labai konkurencinga, vidurkio ateityje. Pagal dabartinį scenarijų dėl nuolat mažėjančių moksleiviams keliamų reikalavimų jiems tampa vis lengviau gauti įvertinimą be pastangų, tiesiog eliminuojant neigiamą įvertinimą, ir visai logiška, kad dėl to moksleiviai vienodėja, tampa mažiau kritiški ir ima stokoti entuziazmo mokytis. Dėl šios priežasties kūno kultūros mokytojai turi išanalizuoti šią situaciją ir kritiškai įvertinti savo pedagoginę prieigą.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: kūno kultūra, epistemologija, moksleiviai, sveikata, motorika

_________

Received: 16/02/2023. Accepted: 25/05/2023

Copyright © Pedro José Carrillo-López,

1. Introduction

The official historiography of school Physical Education has tended to present the process of configuration of the discipline as an evolutionary, quasi-natural and necessary succession of events, personalities, legal provisions, etc. In this evolution, the different elements that define it would have developed in a unidirectional manner until reaching the consistency and technical adequacy that Physical Education is recognised as having today (Vicente-Pedraz & Brozas-Polo, 2017). This study points out that, at present, the predominant justification of Physical Education lies in the healthy and educational nature of systematic and rational physical exercise, with its conformation as a school discipline being the consequence of the progressive systematisation and rationalisation of physical exercises; that is, the result of a process of hygienic-pedagogical purification that would have been eliminating the most spurious forms of exercise and perfecting the most correct forms – those which, in accordance with current social expectations, confer a high level of pedagogical and health relevance.

However, quality school Physical Education remains a hot topic today, as it is still difficult to establish a unified definition of what it is and what needs to be done to achieve it in our classrooms (del Val Martín et al., 2021). Furthermore, concerns that current forms of Physical Education teachers’ education do not adequately provide the tools needed to work with the realities and challenges of teaching Physical Education in contemporary schools have led some scholars to advocate for an approach that prioritises facilitating meaningful experiences in Physical Education (Gumbau, 2015); however, there is little empirical evidence of how future teachers could be taught in this area (Ní Chróinín et al., 2018).

In this sense, the need to explain the historical, curricular and conceptual evolution of Physical Education from a vision of Spain lies in the obligation to offer excellent quality to the education system as part of an unavoidable professional commitment; to do so, it is necessary to provide teachers with valid tools that allow them to make optimal decisions that improve teaching and learning processes from a holistic vision (Rosa-Guillamón et al., 2021), since as a qualitative research with teachers in Australia aimed at analysing the term Quality Physical Education has shown, the understandings of ‘everyday’ teachers can negatively affect student learning and threaten the status and credibility of our profession as the methodology taught by some of them was largely based on their individual and collective experiences and personal ‘philosophies’ about Physical Education (Williams & Pill, 2019). Likewise, the need to generate ideas that promote a conscious and profound didactic, methodological and pedagogical change has been described, as the results show a low reflective-critical attitude in Physical Education on the part of teachers due to the lack of critical intentionality of coherent proposals (Brasó i Rius & Torrebadella-Flix, 2018). Furthermore, the scarce interest aroused by studies on the history of Physical Education is a judgement of a field of research that is still open pending the re-contextualisation of this area of knowledge (Torrebadella-Flix, 2016).

Based on these precedents and following this line of argument, it is necessary to develop a critical framework to rethink quality Physical Education in the current educational framework. In this sense, it is impossible to understand Physical Education if we do not know where it comes from and how it has changed from its origins to the present day. Our hypothesis is that today’s Physical Education is the evolutionary result of a diversity of social, educational, economic, cultural, religious and military developments following transformations since primitive societies. The analysis of its evolution, both historical, curricular and conceptual, is essential for teachers, providing them with a historical basis with which to reflect on the challenges facing Physical Education in the 21st century. Therefore, we will delve into the historical perspective in Section 2, into the curricular perspective in Section 3 and into the conceptual perspective in Section 4 in order to understand where we come from and where we are going in school Physical Education.

2. Method

Type of study

The methodology has been based on a literature review – always limited – of those articles related to the field of Physical Education and that have transcended in their analysis towards ideological approaches about the Theory and Critical Pedagogy of Physical Education, as has been done in previous studies (Brasó i Rius & Torrebadella-Flix, 2018; Rosa-Guillamón et al., 2021).

Search strategy

The search process did not focus on a specific period. The search was carried out in the following databases: Google Scholar, SCOPUS and Web of Science. In addition to the term Physical Education, the following keywords were used: history, curriculum, pedagogy, didactics, intervention and teaching, among others.

Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were used: I) the aim was to analyse the subject matter in the area of Physical Education; II) original articles or theoretical reviews; III) written in Spanish or English; and IV) articles that showed full text in their digital version.

Selection of studies

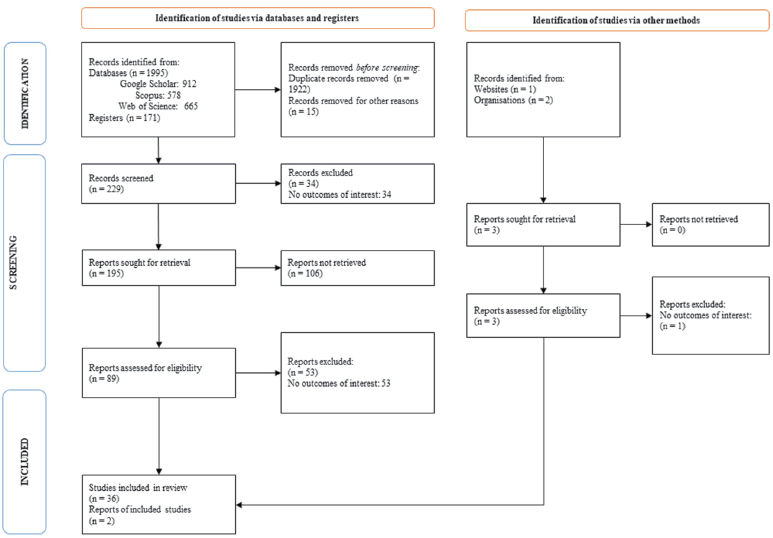

Of the 2169 manuscripts that were exported to the bibliography manager EndNote (X4, Thompson, NY, USA), only a total of 38 articles representative of the subject were considered for inclusion. This selection was carried out by a panel of experts made up of 11 teachers with at least five years of teaching experience in the field of school Physical Education. A summary of what was established in this point can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources

3. Discussion

Analysis of Physical Education from a Historical Perspective

Although health-related issues are currently in vogue, due to the epidemiological reality of many countries in the world, which have a marked tendency to suffer from chronic noncommunicable diseases, concern for self-care and reversing habits such as sedentary lifestyles is not exclusive to modern societies (Luarte et al., 2016). This article reflects that in order to try to understand health-oriented physical activity, an orientation shared by current Physical Education, it is necessary to situate ourselves in the nature of the human species, it is there where we can identify its biological development and its primary cultural attitude. That is to say, in its beginnings, the human being sought to be biologically fit, regardless of environmental influences and socio-cultural dimensions, responsible for future differentiation.

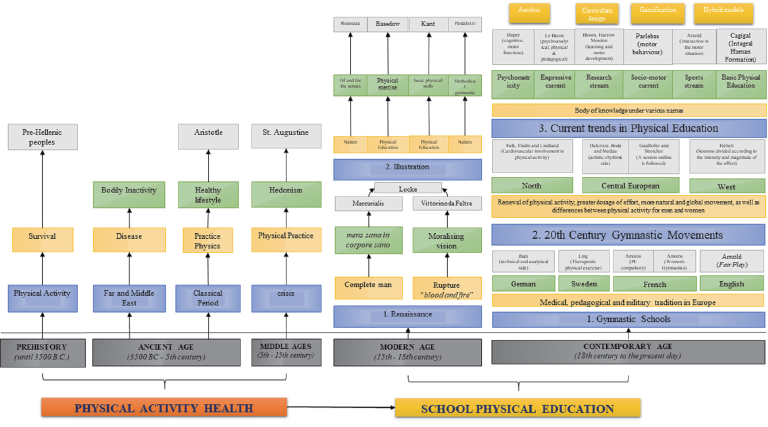

With the passing of history, physical activity has acquired more complexity and organisation, until today we find many expressions, such as: dance, wrestling, recreation and even sports initiation (Blázquez, 2010). The following is a description of the ideas, mentalities and value systems that have influenced what is currently understood as Physical Education associated with each period of history according to the literature consulted (Rosa, 1992; Pérez-Ramírez, 1993; Pastor-Pradillo, 1997; Burgos, 2009; Barbero-González, 2012; Rosa-Guillamón et al., 2018; Vicente-Pedraz & Torrebadella-Flix, 2019; Johnson, 2019; Rosa-Guillamón et al., 2021; Carrillo-López et al., 2021).

From prehistoric times (up to 3500 BC), in the pre-Hellenic peoples, man empirically realised the value of an efficient body for his survival. At this time, physical activity made its appearance, basically focussed on war, hunting and rites with religious reminiscences.

Later, in the Ancient Age (3500 BC – 5th century) there are two periods; I) the Primitive Societies, in which we find the Temazcalli or Aztec primitive sauna (for healing purposes) in Mesoamerica; the Kung-fu (as a form of balance of the person and fight against illness) and the Tsu-kuh (as physical exercise for military purposes) in China; and a system of exercise similar to intervallic training (for war purposes) in Mesopotamia, Persia; II) secondly, in the Classical Period, where three civilisations stand out: in Athens physical exercise is oriented towards integral development while in Sparta its orientation is purely warlike; in Rome we find the Republican period, with a warlike orientation and the Imperial period, where physical exercise acquires a new dimension as entertainment for the masses with the gladiatorial fights. It is worth noting that the principles of Hippocratic medicine were valid throughout antiquity and carried over into the Middle Ages, where they were also the basis of medicine both in the West and in the Arab world. In turn, Aristotle emphasises the healthy lifestyle: “Acquiring such and such habits from a young age is not of little importance: it is of absolute importance”.

Later, in the Middle Ages (5th–15th century), there was a time of crisis for physical activity, as the importance given to the physical aspect was attenuated in order to glorify spiritual development; because of the hatred of any kind of hedonism (due to the dualistic thought of St. Augustine), recreational games in the form of jousting and circus tournaments arose in the upper social classes, which spread throughout the Western world.

Later, in the Modern Age (15th century – 18th century), Physical Education arose from the institution of the Gymnasium (from the German, school), being in the Renaissance very faithful to the idea of the complete man, exalting the cult of the body. In the 15th century, Vittorino da Feltre, a great humanist and educator, in his moralising vision (breaking with medieval pedagogy “by blood and fire”) established the need to incorporate physical exercise into man’s education, being the first to establish a Physical Education programme. In the 16th century, on the one hand, Mercurialis, a doctor and pedagogue, with his work “De arte gymnastica”, recovers Galen’s ideas and promotes what is known as modern medical gymnastics; on the other hand, we have Luis Vives, a philosopher and humanist pedagogue, who considers the need for physical exercise as a way of vivifying the body and replenishing the mind.

Later, in the Enlightenment, authors such as Rousseau (in his work “Emilio”, encouraging people to be of and for the senses in nature), Basedow (proposing physical exercises as part of an educational plan in Germany from his “Philantropinum centre in Dessau”), Kant (laying the foundations of today’s basic physical abilities) and Pestalozzi (combining methodical gymnastics with exercises for application in the natural environment and establishing general didactic principles with a psychological basis through practice) stand out. For Pestalozzi, physical education for schoolchildren is as important as intellectual or moral education and he tried to put into practice a system that would integrate and globalise the whole educational process.

Sharing these premises, in the Contemporary Age (18th century to the present day), Salzman together with Guths Muths (precursor of the rhythmic system) were the first to consider that physical activity should be carried out according to physiological and anatomical laws, giving rise to different national schools all over the world. These schools of gymnastics, which came from the medical, pedagogical and military traditions, became the main branches of all subsequent developments, with these five schools being particularly noteworthy:

– German. It is represented mainly by Jahn (the other great promoter of the rhythmic system), who established his own method of gymnastics, the technical and analytical aspect. For Jahn, the creative character of exercises and apparatus of artistic movements were based on a pedagogical stance aimed at the salvation of the fatherland. This German gymnast, with his ultra-nationalist, militaristic tendencies, succeeded in establishing his own method of gymnastics, known as “Turkunst”.

– Swedish. It is represented by Nachtegall and his successor Henrik Ling (a great precursor of the analytical system), who in his work “Reglemente för gymnastik” interprets physical exercise from a therapeutic point of view, based on three principles: the specific location of the body part being developed, the alternation in the training of these body parts and the logical progression of intensity. This trend has been criticised for its rigidity and formalism, with so-called gymnastic tables with free and aesthetic exercises.

– French. It is divided in two: I) an analytical side developed by Amorós, precursor of modern gymnastics; he established the compulsory nature of Physical Education in schools, and II) a natural side contributed by Clias, creating a Female Gymnastics. As always, the analytical aspect is developed to a greater extent as the natural one, probably due to military support, which finds in it a training model that obtains more tangible results.

– English. Arnold’s contribution is decisive for the current concept of Physical Education, as a precursor of the sports system and introducing the concept of Fair Play in schools. This phenomenon will give a spectacular boost to physical activity, offering a leisure point of view, which brings it closer to what we know today as integral education. This school was a pioneer in self-governing pedagogical methods, with the pupils organising their own games and sports. For Arnold, sport, more than a game, is a gentleman’s way of life.

As a result of these schools, the Gymnastic Movements of the 20th century arose, generating a renewal of physical activity, a greater dosage of effort, a more natural and global movement, as well as differences between physical activity for men and women.

Divided along geographical lines, the most significant of these are:

– Northern movement. It is heir to the Swedish school and its most important representatives are Falk, Thulin and Lindhard, who developed the synthetic method. The keys to understanding this movement are that they try to offer greater dynamism, greater amplitude of movements, they play with body swaying, achieving a cardiovascular involvement in physical activity that is much more important than with its predecessor.

– Western movement. Its main bastion was Hébert, who renewed the methods of the French school by creating a global method. It is based on activity in nature, with sessions divided according to the intensity and magnitude of the effort. He based his studies on the relationship between primitive man and his environment, reaching the conclusion that primitive man is better developed and physically adapted than civilised man. This naval officer and physical education instructor created his own behaviour: to be strong in order to be useful.

– Central European movement. It is derived from the German School, it is divided into two strands.On the one hand, the artistic and rhythmic side, represented by Dalcroze (rhythmic, which gave rise to the concept we understand today as dance), Bode (expressive, which gave rise to corporal expression), Medau (modern, which uses instruments and apparatuses, giving rise to rhythmic gymnastics) and Duncan (dance). On the other hand, the technical side, which is shown by the Austrian Natural Gymnastics of Gaulhofer & Streicher, whose most significant peculiarity is the creation of a functional method with a session outline consisting of animation, school of posture and movement, skills and calming exercises.

The historical analysis carried out gives rise to a body of knowledge with different names. The terms physical activity, physical exercise, movement, sport, physical education, motor action and expressions of motor skills are presented as interdependent phenomena, although they are based on different theories and ideologies. Consequently, they all lead to humanisation, to the construction of values and habits that dignify the quality of life of the students. From the analysis of these concepts, the most important current trends can be included, and if we were to detail them as much as possible, we would precisely delimit what today makes up what is known as school Physical Education. These currents are:

– Psychomotricity. The term is coined by Ernest Dupré in 1913, which refers to a method of general education based on the parallelism between the cognitive functions of human beings and their motor functions. The most important representatives of this trend are Picq & Vayer (psycho-pedagogical tendency), Le Boulch (psychokinetics), or Lapierre & Acoutourier (experiential education). Its implementation has enabled students to master their body movement, improve their memory, attention, concentration and creativity, as well as their interaction with their environment.

– Motor skills. The current of American origin which fills in some of the psychomotor deficiencies. Mainly promoted by psychologists, it emphasises the role of the development of certain skills that they call basic, and other skills called perceptual-motor skills.

- The expressive current. It opens the school to creativity, allowing aspects of imagination, representation and emotion to be addressed, with the aim of communicating sensations, ideas and states of mind with the body. This current, according to Le Baron, has in turn four other aspects: scenic, psychoanalytical, metaphysical and pedagogical.

– The research current, basically based in the USA. In its more didactic side, we find authors such as Bloom (motor, social, affective and cognitive), Harrow (taxonomy) and Mosston (methodology). On the fundamentalist side, we find authors such as Cratty & Singer, who have developed numerous studies on motor learning and development.

– The sociomotor current, promoted by Parlebas, who differentiates sociomotor games (collective) from psychomotor games (solitary), considering movement as motor behaviour in society.

– The sport current. It promotes an institutionalised competitive motor situation. Approached from a formative point of view, it can be accommodated within the school. That is, it has to be process-based rather than goal-based, characterised by the fact that learning includes decision-making processes, social interaction and cognitive understanding.

– Basic Physical Education. Included by Cagigal (1975), as a core subject in the INEF of Madrid, it is positioned around educational values, using points in common with psychomotricity, but criticising the dualism that is implicit in this denomination. It is understood as a way of approaching movement, using it as an educational tool, whose aim is to improve the ability to perceive, make decisions and execute movements. In this sense, Cagigal maintains the importance of the human body in its anthropological character. In addition, he distinguishes a spiritual dimension that each person can enrich, so that he does not reduce human existence to its physical reality and, in turn, opposes the bodiliness and the spirituality. Thus, Cagigal contributes to the importance of the body in an integral human formation, although he bases his ideas on a dualism similar to the Cartesian idea.

– Other currents to be taken into account are Gangey’s Integrating, Delgado’s Fitness, Cooper’s aerobics and Fernández & Navarro’s curricular design, as well as the latest trends arising in the 21st century, such as functional training related to the field of physical activity and health, as well as the horizontal model of comprehensive teaching of sport endorsed by Méndez-Giménez in which the following phases can be distinguished: modified sports games phase, transition phase and introductory phase to standard sports, constituting the most suitable for Physical Education work in Primary Education. Finally, it is prescriptive to point out that there has been an increased interest in alternative methodologies such as gamification, i.e. game strategies linked to technology that are applied to educational practices. A summary of what has been established in this point can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Analysis of Physical Education from a Historical Perspective

Source: own elaboration

Having briefly analysed the historical evolution of Physical Education, we continue with its curricular evolution in Spain.

Analysis of Physical Education from a curricular perspective in Spain

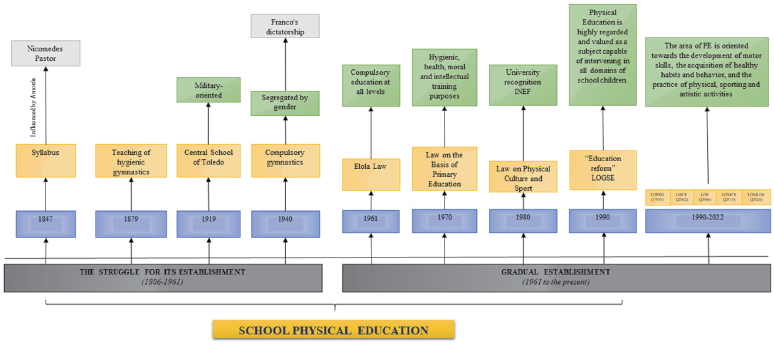

Physical Education in Spain has evolved as a discipline within education in two main stages – the first stage (18th and 19th centuries, i.e. from 1806 to 1961) in which Physical Education is incorporated into schools and has a structured content, and the second (1961 to the present day), in which this discipline, already established in the different educational systems, begins to be the subject of detailed study from different fields. Therefore, this evolution is marked by two other periods: the struggle for its establishment and its progressive establishment (Pastor-Pradillo, 1997; Boyd, 2001; Ramos de Balazs, 2010; Blázquez, 2010; Torrebadella, 2014; Torrebadella-Flix, 2020; Torrebadella-Flix & Pérez, 2021; Torrebadella-Flix, 2021). Based on these works, we will analyse their curricular evolution in Spain.

Although Spain at the beginning of the 19th century had the possibility of advancing towards the so-called renaissance of European physical culture with the creation of the Royal Pestalozzian Military Institute (1806), the project represented an ephemeral dream. It is therefore worth noting that in 1847 gymnastics was incorporated into Nicomedes Pastor’s syllabus, the greatest influence in terms of physical activity being that of Amorós, who directed the Royal Pestalozzian Institute. The departure of Amorós from Spain was a crucial event, an aspect that caused a Spanish backwardness in the field of Physical Education or school gymnastics due to the contradictions of an insufficient and chaotic educational legislation. Nevertheless, there was an attempt by various people to extend the “Amorosian School”, with Francisco de Aguilera y Becerril and the 13th Count of Villalobos standing out above all for their numerous contributions to the configuration of the practice and theory of gymnastics, in their commitment to the development of a scientific awareness of Physical Education. During this period, a Royal Order imposed physical exercise work and the creation of gymnasiums in secondary schools; however, although these instructions were approved, they were not put into practice.

In 1879, a bill was submitted to the Palace of Congress for approval, declaring the teaching of hygienic gymnastics to be official. Later, the Central School of Gymnastics (1887–1892) was created by the Law of 9 March 1883, making gymnastics compulsory for the first school year in 1893; it was modified in 1899, becoming voluntary in schools and colleges. In 1933, a school of Physical Education was created within the San Carlos Faculty of Medicine of the Central University of Madrid, which separated it from the militaristic sense it had taken on at that time.

Subsequently, in 1901, a Royal Decree was drawn up, declaring six courses of gymnastics with two hours a week in secondary schools and corporal games in elementary schools, on a daily basis. Later, in 1919, the Central School of Toledo was created, oriented towards the military, and in 1924 the Children’s Gymnastic Booklet was introduced, being the first methodological reference aimed at unifying the gymnastic pedagogy offered to children and young people.

During the period of the dictatorship, Gymnastics was introduced as compulsory in all secondary school classes. From 1940 onwards, Physical Education for boys was taken over by the “Frente de Juventudes” (Youth Front) and that for girls by the women’s section, with a military perspective. The National Academy of José Antonio for the men and the National School of Isabel la Católica for the women were the schools of trainers at that time. Gymnastics was based on the Swedish model, i.e., fundamentally analytical.

With the appearance of the Elola Law in 1961, Physical Education was definitively introduced in our country, being compulsory at all levels of nonuniversity education. The National Institutes of Physical Education were also created in Madrid and Barcelona (1966 and 1971), and in the General Law of 1970, where special value was given to rhythm. Through the Law of Bases of Primary Education and the Law of Secondary Education, an evolution aimed at the educational sphere is detected, with a hygienic, health and moral and intellectual training purpose.

With the Law on Physical Culture and Sport in 1980, the INEFs received university recognition and trained future secondary school teachers. In its most recent evolution, it can be observed that with the so-called “Educational Reform” initiated in 1990, Physical Education is highly considered and valued as a subject capable of intervening in attitudes and cognitive aspects. The term Basic Motor Skills appears, the student is considered as a fundamental part of learning and sport initiation is fully integrated in the educational curricula. Physical fitness is associated with aspects related to health and corporal expression, working the body as a unit that transmits information. Activities in nature are promoted as a way of using free time, becoming an important part of leisure education.

These changes have persisted in the different regulatory provisions until the current law that governs the regulatory framework for curricular proposals, Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December, which modifies Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education. (LOMLOE), aimed at preventing school failure and improving the quality of education. Specifically, in Physical Education, it is aimed at valuing hygiene and health, accepting one’s own body and that of others, respecting differences and using physical education, sport and food as means to favour personal and social development. Likewise, at national level, the regulations governing curricula (Royal Decree 95/2022, of 1 February, Royal Decree 157/2022, of 1 March and Royal Decree 1105/2014, of 26 December) recognise the value of Physical Education, which maintains continuity and progression in the different educational stages.

Specifically, at the infant stage (Royal Decree 95/2022, of 1 February), the basic knowledge of the area is presented in four large blocks: the first two focus on the development of one’s own identity, in its physical and affective dimensions; the third, on self-care and care of the environment; and the fourth deals with interaction with the civic and social environment. It is also expected to initiate reflection on the responsible consumption of goods and resources, as well as to promote physical activity as a healthy behaviour.

At the primary stage (Royal Decree 157/2022, of 1 March), it is determined that the area of Physical Education is oriented towards the development of motor skills, the acquisition of healthy habits and behaviour, and the practice of physical, sporting and artistic activities. This learning or basic knowledge in the area of Physical Education is organised into six blocks. This knowledge should be developed in different contexts with the intention of generating varied learning situations: I) Active and healthy life; II) Organisation and management of physical activity; III) Problem solving in motor situations; IV) Emotional self-regulation and social interaction in motor situations; V) Manifestations of motor culture; and VI) Efficient and sustainable interaction.

For its part, at the Secondary and Baccalaureate stage (Royal Decree 1105/2014, of 26 December) it is proposed to use Physical Education and sport to promote personal and social development. A summary of this point can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Analysis of Physical Education from a curriculum perspective

Source: own elaboration

This historical and curricular analysis of Physical Education throughout the article will allow us to understand the conceptual evolution of this area. These aspects are developed in the following section.

Analysing Physical Education from a conceptual perspective

The interest awakened in Europe in the second half of the 18th century in Physical Education gave rise to the birth of a new educational discipline that prioritised physical exercise and care of the body with a hygienic-pedagogical purpose (Jurado & Torrebadella-Flix, 2022). Therefore, before the 18th century there is no room to talk about or define Physical Education as such, since until then there were various forms of physical activity in all civilisations, as we have seen above. This utilitarian physical activity for work, training of warriors or for recreational purposes cannot be considered as a historical permanence of the area of Physical Education as it does not share common objectives. In this sense, the concept of Physical Education varies according to the utility given to the body in each era. This discipline has undergone the changes of its social environment at each moment, so it is impossible to detach the pedagogical conceptions from the dominant culture. The essence of education is influenced by these ways of understanding reality at each historical stage.

In summary, Physical Education can be conceived from two approaches: heuristic (laws, theories, hypotheses and principles interrelated by combining a single science) or through a juxtaposition of disciplines. This terminological dispersion is a consequence of the diverse knowledge that has influenced it throughout history, causing this specific subject in the primary, secondary and Baccalaureate stages, according to Royal Decree 157/2022, of 1 March and Royal Decree 1105/2014, of 26 December, to bear a certain burden that the rest of the curricular areas do not bear as they have a well-defined scope of action and work.

Scientific evidence points to John Locke (1634–1704) as the first author to introduce from England the concept of Physical Education through more regulated games in schools. At the end of the 19th century, Physical Education was considered a branch of the medical sciences, which had an epistemological approach that identified it as an independent science with its own object of study, trying to group knowledge under a single descriptor, since, as Uriel Simri states, the term Physical Education is understood in up to sixty different ways all over the world.

In this sense, providing a current definition of Physical Education is a complex task, as it is a polysemy term, the interpretation of which is the result of the content assigned to it, the context in which it is used and the values given to the body. Therefore, after a global definition, we analyse both terms according to the “Real Academia Española” – Royal academy of Spanish language (2022):

– The concept of “education” is related to two distinct but complementary processes, that of hetero-education and that of self-education. Hetero-education, from the Latin educatio, is the process of guidance, construction and edification from the outside, in which the educator is in charge. Self-education, from the Latin ex-ducere, means to draw from within or to do from within.

– The concept of “physics” refers to “phisis” or “matter”, so the Physical Education teacher can be considered as a guide to the subject.

In a global vision, the Royal academy of Spanish language (2022) states that Physical Education is a “set of disciplines and exercises aimed at achieving bodily development and perfection”. Therefore, it can be seen why the area of Physical Education can be analysed from two very different perspectives: a curricular perspective, derived from two aspects, traditional (of a directive nature) and pedagogical (affecting the formation of the whole being); and a historical perspective, where the changes in the vision of Physical Education over time can be observed.

In this sense, Seybold (1974) argues that it is the different fields of science that demand very different conditioning factors from this educational discipline, for example, doctors working on postural habits related to health education, clubs and federations as a breeding ground for athletes, pedagogues as a social escape valve, and dieticians as a complement to their projects.

For Cagigal (1975), Physical Education is the art, science, system or technique of helping to develop in the individual his or her faculties for dialogue with life, with special attention to his or her nature and physical faculties.

Blázquez (2010) points out that the purpose of Physical Education is education and the medium used is motor skills, and that it is an action that affects individuals and not content. It is not the movement that occupies the central place, but the person who moves.

For his part, Rey (2014) identifies it as any intervention with motor skills, with the conscious intention of promoting human development that is conveyed through the experience of corporeality.

López-Pastor et al. (2016) point out that Physical Education is a specific curricular area within a universal, compulsory and public education system, responsible for the physical-motor development of students; for the creation and recreation of their physical culture and comprehensive development, creating citizens for the development of a democratic society. At the same time, they indicate that Physical Education should favour the transfer of school learning to life, provide authenticity in school knowledge during and after school, acting as an institution of social transformation.

Brasó i Rius & Torrebadella-Flix (2018) indicate that Physical Education should contribute to a critical education: not discriminating by gender, valuing the environment and being ecological, seeking an education for peace and reflecting on the predominant model of activities imposed by society. Likewise, teachers, based on their values, ideals and their analysis of reality, must favour certain initiatives, always seeking the emancipation of students, their capacity for critical reasoning and, in short, maximum autonomy so that they can decide for themselves the decisions they can make. At the same time, this study points out that education often promotes a model of human being with characteristics similar to the Orteguian mass-man, with a great deal of knowledge but without the capacity to reflect, dialogue and doubt. And this is what happens in the current educational model, where it is increasingly easier to pass without effort, for the simple reason of eliminating failure, which logically also leads to the elimination of success, as everyone becomes equal, analogous, uncritical and often with little enthusiasm for learning.

In this sense, Arufe-Giráldez, (2020) points out that Physical Education from the earliest age stages plays a major role in the optimal development of each of the schoolchildren’s spheres: physical, social, affective-emotional and psychic. Providing future teachers with a great deal of information and training by teaching content in relation to these four constructs is vital in the educational curriculum puzzle, and the importance of play as a vehicle for generating learning is essential, not only for the content of the area itself but also for other subjects in the curriculum.

In this thread of argument, a nefarious policy means that school Physical Education is caught between two opposing forces: the promises of politicians and the realities in schools. In this sense, Gumbau (2015) points out a series of problems that remain unresolved to this day: Planning without implementation; Marginal status of physical education; Governmental lack of coordination; Serious damage to health; Dissociated intervention model, in which Physical Education is reduced on the one hand and, on the other, attempts are made to make up for it with breaks, active breaks or extracurricular activities; Necessary revision of the physical education curriculum; Search for patches for physical education; Advice by experts at the service of political interests that in many cases do not address social demands; Lack of greater pedagogical attention to the school sport phenomenon; Deficiencies in teacher training; Doubtfully qualified school sport professionals; Lack of incentives for Quality Physical Education professionals; Unstructured continuous professional development; Omission of functions of the collegial organisation; Lack of commitment of the educational community; Unsafe environments and insufficient resources; Strategies without budgetary provision; Failure to take advantage of partnerships with the community; and Lack of quality control and evaluation.

In this regard, in order to respond to the current problem, according to UNESCO and NASPE, it is necessary to increase the teaching load of Physical Education, guaranteeing a minimum real learning time, during school hours, of between 180 minutes and 225 minutes per week, moving towards five hours per week (Espinosa & Cebamanos, 2016), an aspect that would improve ‘physical literacy’ or the ‘transfer’ of what students have learned to their present and future life, which is essential (Devís-Devís, 2018). For example, in this study it is noted that they need to transfer learning about planning and carrying out physical activities into everyday life. They should also apply the tactics learned in games to standard sports and the observation of sport as spectators who value tactical and aesthetic aspects over victory. In this sense, there is no better way to gain legitimacy and social respect from teachers than the commitment and responsibility that each professional maintains to his or her teaching activity.

In turn, the teacher must act as a guide in learning. To this end, the study by Ní Chróinín et al. (2018) identifies five pedagogical principles that reflect how meaningful experiences can be facilitated in Physical Education. Pedagogy includes: planning, experiencing, teaching, analysing and reflecting on meaningful participation. In this sense, the implementation of pedagogies aligned with these five pedagogical principles can help participants learn why meaningful participation should be prioritised and how to facilitate meaningful PE experiences. Along these lines, the Physical Education session should seek to:

1. Social interaction, emphasising positive participation shared with others;

2. Challenge, involving participation in activities that are ‘just right’ (not too easy, not too difficult);

3. Increased motor competence, including opportunities to learn and improve skill in an activity;

4. Fun, which encompasses the immediate enjoyment of the moment;

5. Delight, experiencing more sustained pleasure or joy as a result of meaningful engagement and commitment.

These aspects are endorsed from a regulatory perspective (LOMLOE, Royal Decree 95/2022, of 1 February and Royal Decree 157/2022, of 1 March) and from the available scientific evidence (Bull et al,, 2020), where it is extracted that the concept of school Physical Education in the 21st century is oriented towards achieving the health of students in all its dimensions (physical, social, mental, social and spiritual) since an unhealthy lifestyle can contribute to the development of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes or obesity.

These chronic diseases are the leading chronic diseases in terms of premature deaths, tend to be long-lasting and are the result of a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural factors (Carrillo-López et al., 2021b). This study shows that more than 50% of children and adolescents in southern European countries, including Spain, maintain behaviours that are far from national and international recommendations on healthy lifestyle habits such as maintaining a balanced weight (energy balance), insufficient levels of physical activity (calorie expenditure) or following an optimal diet (calorie intake). In this respect, childhood obesity is a pressing challenge and a public health priority in the 21st century, with more than one third of school children worldwide experiencing overweight or obesity by the end of primary school. In this regard, teachers need to understand the importance of the main factors influencing an increase in obesity and equip students with strategies to reverse this situation (Sánchez et al., 2021). For this reason, the World Health Organisation considers both the lack of physical activity and inadequate nutrition to be a global public health problem and has set it in the Sustainable Development Goals for its reduction by 2030 (Bull et al., 2020).

Once the challenge of acquiring a degree of adherence to an optimal, reflective and autonomous healthy lifestyle by all students has been overcome, it is possible that the area of Physical Education may redefine itself and set other priority objectives related to body education.

4. Conclusion

Throughout the article, the evolution of Physical Education from its origins to the present day has been analysed, highlighting its most relevant moments from the Spanish perspective. It has shown that Physical Education is the evolutionary result of a diversity of social, educational, economic, cultural, religious and military events as an outcome of transformations that have occurred since primitive societies. Analysing its historical, curricular and conceptual evolution is essential for teachers, providing them with a historical basis for reflection of the challenges facing Physical Education in the 21st century. In the educational context, it is vital for teachers to be aware of this historical progress in order to avoid past mistakes and try to improve what currently exists, allowing for a didactic transposition that improves the competence profile of the students in order for them to make better academic use of it. Consequently, students will benefit from a didactic approach adjusted to their needs, being aware of maintaining a progressive responsibility and autonomy in the care of their body, physically and psychologically, stimulating their motor development and cognitive capacity.

The current shift in Physical Education is precisely the training in values, ethics and morals, which brings the educational framework closer to a democratic physical practice that promotes the introduction in schools of comprehensive education and the acquisition of an autonomous responsibility for the care of the human body on the part of the students.

We find ourselves, then, in a current reality with objectives different to the one that preceded it. In this sense, once the challenge of offering an education for all at the end of the 20th century has been overcome, it is necessary to carry out didactic approaches that allow a didactic transposition of the learning learnt at school to its application in real life, and more specifically so that Spanish pupils are at the same level as the European average in a future that looks very competitive. For this reason, Physical Education teachers must shed light on this situation by giving critical intentionality to their pedagogical approaches.

Finally, a quote from the Spanish poet and philosopher Jorge Agustín Nicolás Ruiz de Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. His phrase is written at the entrance to block number 4 of the Auschwitz camp.

References

Arufe-Giráldez, V. (2020). ¿Cómo debe ser el trabajo de Educación Física en Educación Infantil? Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 37, 588–596. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v37i37.74177

Barbero-González, J. I. (2012). El darwinismo social como clave constitutiva del campo de la actividad física educativa, recreativa y deportiva. Revista de Educación, 1(7), 588–596.

Blázquez, D. (2010). La iniciación deportiva y el deporte escolar. Barcelona: Inde.

Boyd, C. (2001). El pasado escindido: La enseñanza de la historia en las escuelas españolas, 1875–1900. Hispania, 61(209), 859–878. https://doi.org/10.3989/hispania.2001.v61.i209.280

Brasó i Rius, J., & Torrebadella-Flix, X. (2018). Reflexiones para (re) formular una educación física crítica. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte. https://doi.org/10.15366/rimcafd2018.71.003

Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., et al. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

Burgos, I. (2009). De la Educación Física de Herbert Spencer, 1861. Ágora para la Educación física y Deportes, 10, 119–134.

Cagigal, J.M. (1975). El deporte en la sociedad actual. Madrid: Editorial Prensa Española.

Carrillo-López, P. J., García-Cantó, E., & Rosa-Guillamón, A. (2021). Escape Room Coronavirus COVID-19 en escolares de Educación Primaria. Sportis. Scientific Journal of School Sport, Physical Education and Psychomotricity, 7(1), 218–238. https://doi.org/10.17979/sportis.2021.7.1.6911

Carrillo-López, P. J., Rosa Guillamón, A., & García Cantó, E. (2021b). Estudio transversal sobre la relación entre la actividad física y la calidad de la dieta en escolares de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética, 25(1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.14306/renhyd.25.1.1139

del Val Martín, P., Sebastiani, E., & Blázquez, D. (2021). ¿Qué es y cómo se mide la calidad en Educación Física? Una revisión de literatura. Sportis. Scientific Journal of School Sport, Physical Education and Psychomotricity, 7(2), 300–320. https://doi.org/10.17979/sportis.2021.7.2.7181

Devís-Devís, J. (2018). Los discursos sobre las funciones de la Educación Física escolar: Continuidades, discontinuidades y retos. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 1(2).

Espinosa, F. J., & Cebamanos, M. A. (2016). Educación física de calidad en el sistema educativo español. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 414, 69–82.

Gambau, V. (2015). Las problemáticas actuales de la educación física y el deporte escolar en España. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 411, 53–69.

Johnson, F. N. (2019). El dualismo cuerpo y alma en la Educación Física: análisis de las ideas de José María Cagigal. EmásF: revista digital de educación física, 60, 116–126.

Jurado, M. Á., & Torrebadella-Flix, X. (2022). La bibliografía gimnástica extranjera en el proceso de institucionalización de la educación física española del siglo XIX (1807-1883). Traducciones y adaptaciones. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 43, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v43i0.89003

López-Pastor, V. M., Pérez Brunicardi, D., Manrique Arribas, J. C., & Monjas Aguado, R. (2016). Los retos de la Educación Física en el Siglo XXI. Retos, 29, 182–187. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i29.42552

Luarte, C., Garrido, A., Pacheco, J., & Daolio, J. (2016). Antecedentes históricos de la Actividad Física para la salud. Revista Ciencias de la Actividad Física, 7(1), 67–76.

Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., & O’Sullivan, M. (2018). Pedagogical principles of learning to teach meaningful physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2017.1342789

Pastor-Pradillo, J. L. (1997). Historia de la educación física en España, el ámbito profesional (1883–1961). Génesis y formación. Alcalá de Henares: Universidad de Alcalá.

Pérez-Ramírez, C. (1993). Evolución histórica de la Educación física. Apunts, 33, 24–38.

Ramos de Balazs, A. C. (2010). Educación física, currículum y práctica escolar. Tesis Doctoral. Universidad de León.

Rey, A. (2014). Ciencia y motricidad. Madrid: Dykinson.

Rius, J. B., & Torrebadella-Flix, X. (2022). La libertad vigilada. En torno a la invención del juego educativo en España. Márgenes Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Málaga, 3(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.24310/mgnmar.v3i1.12795

Rosa, M. (1992). Historia de la educación física. Cuadernos de sección. Educación, 5, 27–47.

Rosa-Guillamón, A., Carrillo-López, P. J., Cantó, E. G., García, J. E., & Madrona, P. (2021). Revisión bibliográfica de los métodos enseñanza en educación física. Acciónmotriz, 27, 46–56.

Rosa-Guillamón, A., García-Cantó, E., & Carrillo-López, P. J. (2018). La educación física como programa de desarrollo físico y motor. EmásF: revista digital de educación física, 52, 105–124.

Sánchez, G. L., Llussà, A. S., & Bautista, C. V. (2021). La obesidad. Un enfoque multidisciplinar como paradigma para enseñar en el aula. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 42, 353–364. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v42i0.87153

Seybold, A. (1974). Principios pedagógicos en la Educación Física (No. 372.86 S519p). Buenos Aires, AR: Kapelusz.

Torrebadella, X. (2014). La educación física comparada en España (1806-1936). Social and Education History, 3(1), 25–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/hse.2014.02

Torrebadella-Flix, X. (2016). La historia de la educación física escolar en España. Una revisión bibliográfica transversal para incitar a una historia social y crítica de la educación física. Espacio, Tiempo y Educación, 3(2), 4(1), 1–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.14516/ete.2017.004.001.76

Torrebadella-Flix, X. (2020). La escolarización de la educación física: un análisis de cinco imágenes publicadas en la prensa de Barcelona de principios del siglo XX (1910-1913). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 20. https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e115

Torrebadella-Flix, X. (2021). El gimnasio en casa (1861–1912): ¿De una moda a estilo de vida saludable? MHSalud: Movimiento Humano y Salud, 18(1), 24–53. https://doi.org/10.15359/mhs.18-1.6

Torrebadella-Flix, X., & Montes, J. A. D. (2018). El deporte en la educación física escolar. La revisión histórica de una crítica inacabada. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, 34, 403–411. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v0i34.57963

Torrebadella-Flix, X., & Pérez, A. (2021). Noticias de la gimnasia o educación física en los colegios privados de Madrid (1833-1883). Cabás, 25, 3–32.

Vicente, M., & Brozas-Polo, M. P. (2017). El triunfo de la regularidad: gimnasia higiénica contra acrobacia en la coniguración física escolar en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX. Revista Brasilera do Sporte, 39(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbce.2015.10.006

Vicente-Pedraz, M., & Torrebadella-Flix, X. (2019). Los primeros gimnasios higiénicos: espacios para sanar y corregir el cuerpo. Disparidades. Revista de Antropología, 74(1), e011-e011 https://doi.org/10.3989/dra.2019.01.011

Williams, J., & Pill, S. (2019). What does the term ‘quality physical education’mean for health and physical education teachers in Australian Capital Territory schools? European Physical Education Review, 25(4), 1193–1210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18810714