Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2023, vol. 51, pp. 84–97 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2023.51.5

Ugnė Supranavičienė

Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania

ugne.supranaviciene@gmail.com

Genutė Gedvilienė

Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania

genute.gedviliene@vdu.lt

Abstract. The perception and identification of leadership are continuously being researched. However, in recent times the need for leadership has become more apparent in organisations of all kinds. The everyday reality of the present day is forcing us to rethink all the truths and theories of leadership that have been defended so far. This paper aims to reveal the challenges of middle managers in organisation towards servant leadership competencies development. A qualitative research design was used to explore the competencies of middle managers. Data was collected from seven middle managers in one of the Lithuanian Railways organisation LTG Link. These managers participated in three competency development assessments (self-confidence, emotional intelligence and leadership assessments), following focus group discussion where they were reflected on leadership concepts in the organisation, how they perceive themselves in the organisation, how they recognise servant leadership competencies and what challenges are facing in order to bring servant leadership as a dominant leadership style in the organisation. Managers were asked to reflect in three competency development layers: the reflection of middle managers’ understanding of leadership and management; understanding of the relationships between middle managers and subordinates; and understanding of relationships between middle managers and their management. According to the research findings, there are challenges in all the layers for middle managers to develop servant leadership competencies. Current leadership conception in the organisation is focused on a manager-centric approach, where the main focus is on the manager not the subordinate, in the servant leadership concept there is an employee-centric approach. The organisation’s processes and procedures are constructed to control and constrain the decision-making of middle managers. There is no working competency development and support system in the organisation to guide middle managers to become servant leaders, this leads to a nonunified leadership competency concept in the organisation, where middle managers bring their own understanding without any background. Furthermore, the hierarchical organisational structure limits the motivation of middle managers to develop their servant leadership competencies.

Keywords: adult education, competencies, leadership challenges, middle managers, servant leadership

Santrauka. Lyderystės suvokimas ir identifikavimas yra nuolat tiriamas, tačiau pastaruoju metu lyderystės poreikis tapo vis akivaizdesnis įvairaus pobūdžio organizacijose. Šių dienų kasdienybė verčia permąstyti visas iki šiol gintas lyderystės tiesas ir teorijas. Šiame straipsnyje siekiama atskleisti organizacijos viduriniosios grandies vadovams kylančius tarnaujančiosios lyderystės kompetencijų ugdymosi iššūkius. Buvo atliktas kokybinis tyrimas. Duomenų jam gauta iš septynių tyrimo dalyvių – viduriniosios grandies vadovų, dirbančių vienoje iš „Lietuvos geležinkelių“ organizacijų „LTG Link“. Šie vadovai dalyvavo trijuose kompetencijų ugdymo (pasitikėjimo savimi, emocinio intelekto ir lyderystės motyvacijos) vertinimuose, paskui vyko fokus grupės diskusijų, kurių metu jie svarstė apie lyderystės sampratą organizacijoje, apibūdino, kaip jie suvokia save organizacijoje, kaip atpažįsta tarnaujančiosios lyderystės kompetencijas ir su kokiais iššūkiais susiduria siekdami, kad tarnaujančioji lyderystė taptų vyraujančiu vadovavimo stiliumi jų organizacijoje. Vadovų buvo prašoma reflektuoti trimis kompetencijų ugdymo lygmenimis: viduriniosios grandies vadovų lyderystės ir vadovavimo sampratos refleksija; viduriniosios grandies vadovų ir pavaldinių santykių supratimas; viduriniosios grandies vadovų ir jų vadovybės santykių supratimas. Remiantis tyrimo rezultatais, visais kompetencijų ugdymo lygmenimis viduriniosios grandies vadovams kyla iššūkių ugdantis tarnaujančiosios lyderystės kompetencijas. Dabartinė vadovavimo samprata organizacijoje orientuota į vadovo požiūrį, kai pagrindinis dėmesys skiriamas vadovui, o ne pavaldiniui, tarnaujančiojo vadovavimo koncepcijoje vyrauja į darbuotoją orientuotas požiūris. Organizacijos procesai ir procedūros kuriamos taip, kad kontroliuotų ir ribotų viduriniosios grandies vadovų sprendimų priėmimą. Organizacijoje nėra veikiančios kompetencijų ugdymo ir paramos sistemos, kuri padėtų viduriniosios grandies vadovams tapti tarnaujančiaisiais lyderiais, todėl organizacijoje susiformuoja nevientisa vadovavimo kompetencijų koncepcija, kai viduriniosios grandies vadovai turi savo individualų supratimą be jokio galimo pagrindimo. Be to, hierarchinė organizacijos struktūra riboja viduriniosios grandies vadovų motyvaciją ugdyti tarnaujančiojo vadovavimo kompetencijas.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: kompetencijos, lyderystės iššūkiai, suaugusiųjų ugdymas, tarnaujančioji lyderystė. viduriniosios grandies vadovai.

________

Received: 28/04/2023. Accepted: 10/08/2023

Copyright © Ugnė Supranavičienė, Genutė Gedvilienė

Historically, organisation’s effective top managers are not only those who are effective because of their competencies and qualities as professionals, but also because of their personal, human qualities. This is why managers at this level often invest in the development of effective leadership competencies. However, it is not only the top managers in an organisation’s hierarchy. As usual, middle managers are highly qualified professionals who have had no previous management experience. This means that leadership is a completely new term and status for them, accompanied by a huge sense of responsibility and accountability. They are not involved in the strategic decision-making processes of their organisations, but are responsible for the efficient, high-quality, and sustainable performance of their teams. This is an equally significant role, and one that is crucial to the long-term success of the organisation. The observable and trainable behaviors and behavioral patterns of highly effective middle managers are important to leadership writings (Weide, & Wilderom, 2004). The empirical study provided an opportunity to assess the current situation in the organisation and demonstrated the challenges middle managers face in their leadership development as servant leaders.

For a long time, middle managers have been perceived as implementers of tactical decisions without contributing to the strategic goals and vision of the organisation. They have been perceived as executors of the organisation’s strategy. The manager’s role was only to ensure that the worker adapted his/her movements to the standard model set (Parera & Fernandez-Vallejo, 2013). Increasingly, however, top managers in organizations are strengthening their delegation competencies, thus extending the range of tasks and functions to middle managers. Middle managers act on behalf of the organisation and create virtuous human systems through corporate social initiatives (Sharma & Good, 2013). Middle management is the natural result of a new organisational structure that originates in a knowledge society (Parera & Fernandez-Vallejo, 2013). In Lithuania, the number of middle managers is growing every year, more organisations are opting for flatter organisational structures (as opposed to hierarchical organisational structures), and the competences of middle managers are no longer sufficient to ensure the smooth, efficient, productive, and sustainable development of the organisation. The involvement of middle managers adds value not only to the implementation of strategy but also to its formulation (Ouakouak, Ouedraogo & Mbengue, 2014). The development of leadership competences of middle managers becomes a critical factor in ensuring that the organisation achieves its objectives. Middle managers’ orientation to their role is entangled with the process of energizing their teams in organisational learning during change (McKenzie & Varney, 2018). Developing financial and personnel expertise are common adult education topics for middle managers (Mosley, 2008). There is a popular saying that an employee does not change jobs because of the organisation, but because of the manager (McCrae, 2020). What does this mean? This can be a crucial message about the role of the leader in shaping the competences of middle managers in an organisation. The question naturally arises: does the leadership of middle managers in an organisation have an impact on the success of the organisation and how? Servant Leadership is a nontraditional leadership philosophy, embedded in a set of behaviors and practices that place a primary emphasis on the well-being of those being served (Greenleaf, 1977). This philosophy is employee-centered, a philosophy that is critically important and relevant today. The value of servant leadership education in the training of future leaders within the helping professions was supported (Fields, Thompson & Hawkins, 2015).

According to the author of (Erhart, 2004), the instrument comprises seven categories of Servant Leadership: positive relationships with subordinates; empowerment; helping subordinates to grow and experience success; ethical behaviour; conceptual skill; interest of followers before own; creating value for the community.

Furthermore, servant leadership stresses personal integrity and serving others, including employees, customers, and communities (Liden, Zhao & Henderson, 2008). There is an understanding that the development of middle managers’ competencies should be a priority for the organisations in order to create a sustainable and successful organisation in the future.

Research on servant leadership is broad, covering different contexts, cultures, and organisations. It has also been applied in diverse types of organisations: business organisations, educational organisations, nonprofit organisations. It is important to note that there is a considerable and growing body of research on servant leadership in business organisations due to the increasing business focus and perceived benefits.

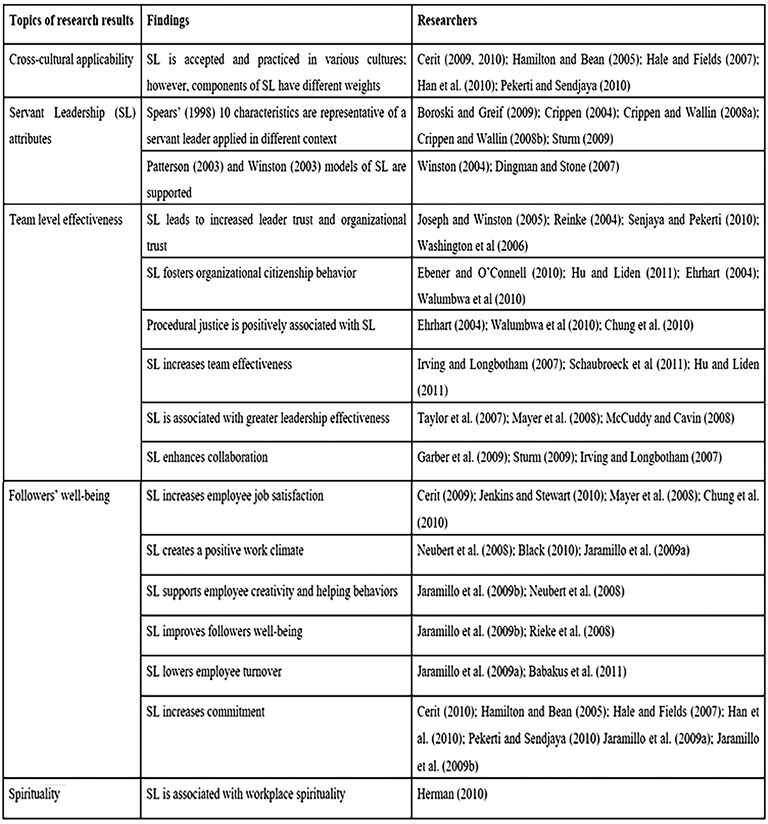

In the following, the overview of the research will be provided (see Figure 1) that examines servant leadership competencies development and its benefits to the organisation (D.L. Parris, J.W. Peachey, 2013). As can be seen in Table 1, research on servant leadership includes a broad cross-cultural context and the acceptability of servant leadership competencies development across cultures. Research investigating team effectiveness has shown that servant leadership competencies development environments adhere to principles of justice and fairness, which is positively related to procedural justice. The cultural dimension addressed is important for effective performance and the universality of servant leadership competencies practices is a critical factor in ensuring the sustainability of an organisation. This is particularly relevant in today’s global world, where, very often, the members of teams in organisations are from different countries and cultures. Despite the identified benefits of the servant leadership model, different components carry different weights in different contexts. Servant leadership attributes have been analysed in detail by Spears, who believes there are ten characteristics that define servant leadership in different contexts. Research has shown that the quality of performance of teams is directly determined by the presence of trust in the leader and the presence of cooperation within the team. Servant leadership creates greater trust in the team and is therefore linked to higher quality performance in effective teams. Further analysis of the research reveals that the servant leadership model creates a greater sense of employee citizenship in the organisation, which is especially important as it is linked to employee well-being at work. The use of this tree in an organisation is related to the effectiveness of teams, the sense of operational justice of the organisation’s employees, the promotion of cooperation and the visibility of leadership effectiveness. What is also important in the analysis is the criteria for employee well-being at work. Studies have measured and confirmed that the application of the servant leadership model in an organisation improves employee job satisfaction, creates a positive work climate, supports employee’s creativity and helping behaviours, lowers employee turnover and increases commitment. The studies also looked at spirituality, but no significant findings could be drawn, so it cannot be said that servant leadership creates greater spirituality in the organisation. This aspect is only relevant for a few types of organisations, it is not a universal criterion for managing an organisation and therefore its relevance is too narrow and not studied.

Furthermore, middle managers have long been seen as the doers of organisational performance and their influence in organisations has been underestimated. Historically, there have been times when middle managers have been the first to be dismissed because organisations have found it difficult to justify the real impact of their role on the effectiveness of the organisation. They were perceived as weak leaders and business did not invest in their leadership competences. In 1950, sociologist C. Wright Mills wrote “...You are the cog and the beltline of the bureaucratic machinery itself... and such power as you wield is a borrowed thing. Yours is the subordinate’s mark, yours is the canned talk... you are the servant of decision, the assistant of authority.” Meanwhile, there were other views where the role of middle managers was reversed and perceived as indispensable to the sustainable and effective growth of the organisation. The economic historian Alfred Chandler, in his book The Visible Hand, examines the role of middle managers from a historical perspective, in two cases: the first is that, with the advent of manufacturing at the beginning of the twentieth century, it is no longer enough for a company to have only workers to produce, but it also needs salespeople, marketers, and the development of new production systems. This demand requires leadership in specialist teams. This is why, at this stage, middle managers emerge as coordinators to ensure the company’s effective growth, and secondly, as companies started to produce more than one product, there was a need to create teams across the spectrum, to be led by middle managers. He believed that it was middle managers who were the professionals who contributed to the growth of the US economy (Chandler, 1993).

“Instead of being trapped in stultifying bureaucracies, middle managers are now free to be “entrepreneurs,” to take charge of their own careers and, like many other professionals, to enjoy the benefits of mobility and portable skills” (Osterman “The Truth about Middle Managers”, p. 12). Flexibility and mobility are critical factors currently of changing perceptions of the workplace through technology and increasing worker mobility. The role of middle managers as an effective link between the organisation and the workforce has been highlighted during the pandemic. During the pandemic period, organisations had to interrupt their normal work and move their operations as far as possible to telework. This created a critical need for increased communication with employees to ensure that the organisations’ work could continue uninterrupted. A new term, “Connecting Leaders,” emerged. Table 2 shows four types of Connecting Leader, which are differentiated according to leadership practices, risks and mitigation. These diverse types of Connecting Leader describe their communication style with their team and the organisation. What is particularly important to note is that the risks of most of the types are linked to the lack of servant leadership skills. Managers take on development and learning as main collective work tasks because they want to influence knowledge creation (Wang, 2013). Therefore, it is important for middle managers to develop servant leadership competences.

As the literature review has shown, servant leadership is referred to as a multidimensional construct, but there is no clear and reliable instrument of servant leadership that maintains a stable factor structure and is suitable for measuring it across different samples.

To assess the potential servant leadership competencies of middle managers in the organisation, the emotional intelligence, self-confidence and leadership motivation assessments were made for middle managers in the organisation.

In this paper a qualitative research design was chosen to measure the competences of middle managers through focus groups. The aim of the focus groups is to create an environment where actual competences can be identified rather than desired ones. It is important that the focus group interviews provide authentic responses and conversations from which real conclusions can be drawn about the competences that middle managers have and want to acquire. One focus group was planned for middle managers.

The focus group interview questionnaire was designed to give participants the opportunity to discuss their perception of leadership, their relationship with their subordinates and their management.

Seven middle managers in the organisation who met the criteria (location, size of the team, and work experience) participated in the assessments and focus group interview.

LTG Group is a large organisation, and for this study middle managers from one of the LTG Group companies were used. Specifically, LTG Link was chosen as the company whose business is passenger transport. Companies’ employees are professionals with diverse backgrounds, ranging from train stewards to mechanics.

Figure 2 below shows the results of the answers given by middle managers in three individual competency development assessments on their leadership motivation, emotional intelligence, and self-confidence.

The assessment of leadership motivation was conducted accordingly, with a score of 4 or more indicating a high motivation to lead, 2 to 4 indicating an unclear motivation to lead, and less than 2 indicating a low motivation to lead. The results of the Leadership Motivation Assessment showed that most middle managers have unclear motivation, with one manager standing out the most, with the highest motivation to lead. It should also be noted that the responses of people differed. Female managers had significantly lower motivation to lead, none of them reaching four, whereas all male managers were motivated to lead of four or more.

The self-confidence competency assessment was designed to identify the extent to which managers have a sense of self-efficacy and the extent to which they are confident in their ability to succeed when faced with challenges. The self-confidence scoring system is similar to the leadership motivation scoring system: four and above indicates a sense of self-efficacy, two and below indicates a weak sense of self-efficacy, i.e., a general lack of confidence in one’s ability to succeed when faced with challenges. The results of this competency development assessment showed that most middle managers do not have a powerful sense of self-confidence, which means that they have doubts about whether they would succeed when faced with difficulties. It should be mentioned that only one manager out of seven has a powerful sense of self-efficacy. This result suggests that, despite their leadership motivation scores, self-confidence is not directly related.

The Emotional Intelligence competency assessment consisted of four parts: perception, appraisal, and expression of emotions; understanding and analysing emotions and using emotional knowledge; self-discipline; reflective regulation of emotions; and an overall assessment of emotional intelligence skills. Managers with a score of 4 and above have developed emotional intelligence and the ability to apply it in practice, while those with a score of 2 and below do not have emotional intelligence competences. The results obtained from the middle managers who participated in the study suggest that all managers lack emotional intelligence competences and sometimes find it difficult to express their own emotions and to accept the emotions of others. This may make it difficult to collaborate effectively with subordinates to ensure that the emotional climate in the team is acceptable to all.

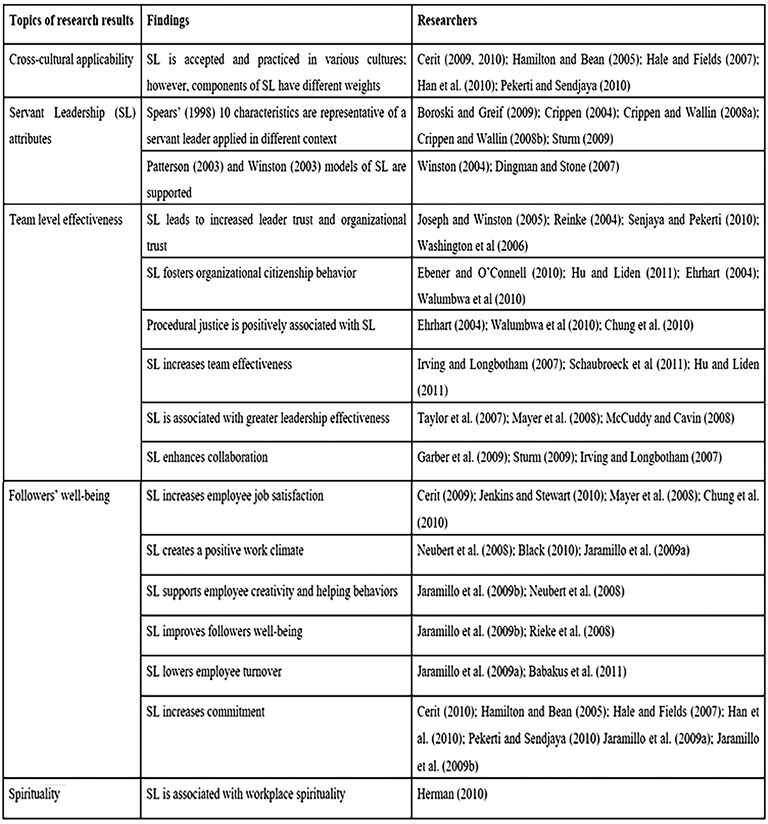

Seven middle managers were invited to the meeting, three of them came to the meeting and the other four joined remotely. The focus group discussion was therefore organised in a mixed mode, using the organisation’s multimedia equipment. Discussion with the participants was constructed in three competency development layers (Figure 3): 1. Middle managers’ understanding of leadership and management; 2. Relationship between middle managers and subordinates; 3. Relationship between middle managers and management.

Middle manager’s understanding of leadership and management. The questionnaire aimed to find out how participants became managers, how they understand leadership and what they think about the role of the manager in an organisation. When asked about their chosen managerial path and how they became a manager, Middle Manager No. 4 mentioned “I will mention my parents at the beginning, they had strong influence, both have several higher education degrees, both have a master’s degree, but both are not working in their specialities. My dad has been a mechanic in a garage all his life and my mum has been a manager all her life. And my leadership started at an early age when I became a young shooter at 14. By the age of fifteen, I had already been noticed and appointed as a section commander. Further on in the army I had, shall we say, success and recognition. The career up to commander was more a matter of luck... I fired the warehouse manager and had no one to fill that hole, let’s say, of a manager. They put me in temporarily, and it just so happened that I stayed...” Meanwhile, Middle Manager No. 2 said “I never wanted to be a manager, but I must have had that path since the first grade, when I had to be a schoolboy, a pioneer and a Communist Party member, and in the district I had these positions when I came to work for the railways... 30 years ago... I have been through a lot of positions, vastly different... I have risen to the position of regional manager; I would like to be more in my life... I would be more interested in technical work... designing, drafting. If I could choose a speciality today, I would choose IT. I am more enthusiastic about that kind of work than I am about management.”

The interviewees took vastly different paths towards leadership positions, some made a conscious choice, others took the opportunity when it came, and others did not make a choice that came naturally. It is therefore not surprising that the results of the assessment of the motivation for leadership, for example, of Middle Manager No. 2 are not high (3.2), because even today, a managerial position is not a goal for this manager. However, it is important to note that even though this middle manager would choose a different profession today, his motivation score is not low, indicating a potentially high work culture and ethic and a sense of responsibility.

Further attempts were made to elaborate and further identify the concept of leadership of managers by asking how you understand leadership, what are the responsibilities, what are the limits, what are the opportunities from their experience. Middle Manager No. 1 said “You know how I tell my staff, I’m not here to punish you or do anything else, and I’m here to give you every opportunity to do your job properly, on time and to a high standard... A manager is a person who helps, who makes it possible for his employees to do what the manager asks them to do... to advise, to scold the next time, to praise, to do something for him the next time... to show.” Middle Manager No. 5 agrees with the previous opinion and states that “the manager must show the direction in which the employee should move, not to punish, not to scold..., just to guide him in the right direction.” Middle Manager No. 6 understands leadership in the following way: “We are like glue that has to stick the team together like a ball.” Meanwhile, Middle Manager No. 3, agreeing with all the previous speakers, added another term to the concept of leadership: “Visionary and forward-looking, looking at how things are going to change and preparing for those changes immediately to make the impact as gentle as possible and when I generate work for people, I try to take into account those future challenges and so in a way reduce turbulence for the employees. But it doesn’t always work, because often there is a lot of lead from all sides, and that, let’s say, visionary quality gets a lot of flak... without visionary, it’s difficult because it shows you where you’re going and... how it sticks to one final decision, because the staff gets lost... keeping the direction of the manager, being a helper when something is not clear and you need to empower someone somewhere, that’s the mission I have.” In the following discussion, Middle Manager No. 4 shared his perception of being a leader: “I’m shaking off the supervisor title, I want to be more of a leader, it’s more about being at the front and being with your team... to go forward with them and to help them if necessary.”

During the interviews, managers expressed their perception of leadership, some clearly understand the concept of leadership, others want to move away from the term and see themselves more as supervisors. Despite the desire to show a positive and friendly attitude towards leadership, some managers do not shy away from terms such as punishment or reprimand. Moving on to the next layer of questions, the survey sought to find out how participants perceived the relationship between manager and subordinates, what kind of relationship with an employee is acceptable to them, where the boundaries of friendship and professionalism lie, and whether partnership is a good basis for the manager–employee relationship. The managers’ reflections were the following: Am I the same for everyone? If I am the same for everybody, then I am probably balanced, if I am very protectionist towards somebody, then I will probably already have a protectionist view towards them,” while another Middle Manager No. 3 said “I think it’s a very, very individual thing, with each member of your team personally, because really, as I said, I had 60 people under me, and maybe I’ll put it in a trivial way, there were some people who...you can have a bottle together, but when you come to work, there’s always going to be... there are certain steps between a manager and a subordinate... and there were some people you can’t cross the barrier with... he will accept familiarity... as a sign that he can get discounts or something like that... but you really need to spend more than a month with someone to get to know them... A thin red thread with each individual.” Another manager’s experience gave him the opportunity to take a different approach with his subordinates. Middle Manager No. 4: “When I have some ideas, and they know how to do it, so then I only make a decision, I would always ask them for their opinion, and usually we would have a clash of opinions. They would find ten reasons why not to do it and I have to find at least one reason why it should be done and I would try to convince them, it isn’t that I say that this is the way it’s going to be, I try to convince them why it should be done, and 95% of the time I get my point across and the employees left with a good feeling.”

During the interviews, all participants agreed that the effectiveness of the team and the quality of the work directly depends on how much the manager knows his/her team members, the individual approach to each one, but at the same time the manager’s equal and fair treatment of each employee is equally important.

The third layer of the focus group interview focused on the relationship between middle managers and the organisation. Participants discussed their current position in the organisation, the extent of their influence, their involvement in decision-making, the influence that middle managers can exert in the organisation, and how and in what ways they would like to influence the organisation’s future activities.

In terms of the scope of middle managers’ responsibilities and the required competencies Middle Manager No. 1 said: “There are certain tasks where we can make decisions ourselves, but there are also tasks, say on some bigger projects, where we consult with our regional manager and if the manager agrees, it’s good for us, we agree, and then it’s decided,” According to this participant, his position as a middle manager gives him limited room for manoeuvre, but nevertheless decisions are not taken without the expert opinion of the middle management, which means that the middle manager needs to have not only expertise but also managerial competencies. According to the organisation’s internal procedures, when a new recruit is added to the team, the middle manager is involved in the recruitment process as the initial contact for interviewing potential candidates, and it is only after the middle manager has approved the candidate that he or she moves on to the next stage, where a more senior manager interviews the potential employee. The final decision is made by the senior manager, as Middle Manager No. 4 said “...we do the selection, we choose the employee, we talk to the employee, then our line manager talks to the candidate and it’s more of a manager’s decision, it’s our manager’s decision to accept the person or not,” and Middle Manager No. 2 added. It is not like they said it and it is sacred and that is it, our opinion is not important... We have our own opinion, we can express it, we have the possibility to express our ideas, and to make our proposals... to bring suggestions from our team members... here is one of our main jobs.” Thus, the managers who participated in the discussion said that their opinion is important in decision-making and they can influence and even change decisions in the organisation, they feel that they can influence the decision-making of those who directly affect their work, the team they lead, etc. Despite the examples given where managers are involved in decision-making, I see the negative side of this process: according to the organisation’s internal procedures, the final decision on a new team member is taken by a senior manager, and in this case, the organisation demonstrates that middle managers do not have enough competencies to properly assess and decide on the most suitable new team member.

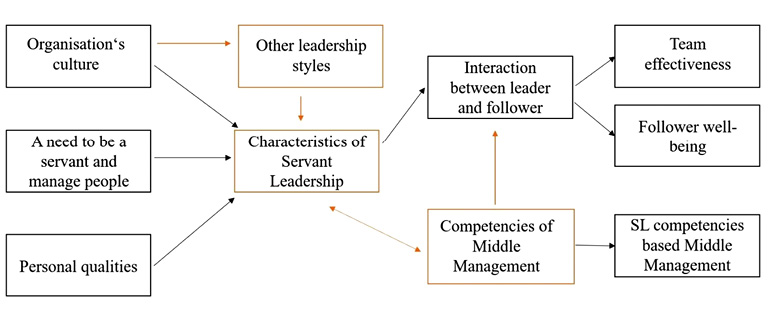

The focus group interviews took into account participants’ responses and discussions and identified the importance of considering other leadership styles used by managers to ensure the competencies of a servant leader for middle managers. This is important because managers lead teams of diverse types and competencies. Therefore, the theoretical model also includes such other leadership styles and their attributes (democratic leadership and autocratic leadership). The model illustrates the strong link between the culture of the organisation and other leadership styles, as these are dictated by the culture of the organisation, which directly influences the competencies of the servant leader. The strong link and correlation between servant leadership and the competencies of middle managers, which was discussed earlier, can be seen below (Figure 4). This link is crucial for quality and sustainable leadership in an organisation. Meanwhile, linking the competencies of servant leadership and middle management creates a new link with the interaction between leader and follower. This creates a different view of the leader himself, his role, and his relationship with his subordinate.

In order for an organisation to be efficient and innovative in order to ensure sustainable operations, it is necessary to develop new models of competence development for middle management, which are systematic, consistent, sustainable and measurable. The research revealed the challenges faced by middle managers in the development of competencies and their motivation, which is critical for the servant leadership competency development. In other researches the findings of the challenges were that middle managers lead others, but are also led. As such, their leadership behaviour may depend upon the leadership style of their own superior. Middle managers are oftentimes responsible for executing a strategy and, thus, have little autonomy in setting direction themselves. In particular, being assigned difficult goals and translating these—via their own leadership behaviour into action is challenging. Furthermore, middle managers’ roles are typified by dependency on both organisational human resource procedures and on external developments that can impact their career paths (Voorn, 2018). Middle managers require support in induction into the middle management role and ongoing mentoring and appraisal (Chetty, 2007). Analysis of other studies and review of the findings of this study lead to a discussion that, in order to motivate and ensure the sustainable development of the competencies of middle management, their involvement in strategic decision-making processes should be ensured first and foremost, and leadership support programs should be established for middle management. Leadership competencies should also be developed not only for middle managers but also for their managers. Furthermore, caught in the middle, middle managers often receive training on competencies intended to help them manage issues that arise from this situation. Yet this training tends to be temporarily helpful at best-and harmful at worst. Competency training, because it focuses on changing behaviour, fails to address a foundational element necessary to consistently and effectively resolve their challenges. That foundational element is mind-set. Providing training and tools to shift their mind-set regarding their management objectives better prepares mid-level leaders to be more effective in their challenging positions (Otocki & Turner, 2020). Therefore, it is necessary and very useful not only for the organisation, but also for its employees to develop the Servant Leader competency development program for middle managers. Combining personal learning and organisational action without compromising academic standards is a powerful program design to address multiple learning loci (Bergren & Soderlund, 2010).

Nevertheless, there are obstacles to this training of the servant leadership in the organisation, which directly affect the process and priorities.

The current conception of leadership in the organisation is more focused on the manager, whereas the core principle of the servant leadership model is to serve the subordinates, to put their needs above the manager’s, which means that in order to apply the competency model of the servant leader, the first step would be to change the approach of the object of leadership from a manager-centric approach to a follower-centric approach. In order to create an effective adult education environment for the middle managers, it is important to solve the challenges which were identified during this research. Such a change would require a review of the organisation’s entire strategy, objectives, organisational structure, matrix of authority and responsibility, business processes as well as human resources strategy. Furthermore, middle managers mentioned limitations within the organisations’ internal processes and procedures, which directly affects the motivation and further possibilities for middle managers to develop servant leadership competencies in the organisation. The lack of unified leadership competency development concept and approach for the middle managers in the organisation also acts like a limitation and will not contribute to the sustainable organisation development in the future. The hierarchical organisational structure limits the motivation of middle managers to develop their servant leadership competencies.

References

Berggren, C., & Söderlund, J. (2010). Management Education for Practicing Managers: Combining Academic Rigor with Personal Change and Organizational Action. Journal of Management Education, 35(3), 377–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562910390369

Chetty, P. (2007). The role and professional development needs of middle managers in New Zealand secondary schools. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-role-and-professional-development-needs-of-in-Chetty/06aee98f156ecca1b84ad6a7f0213e6b97540b16

Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit‐level organizational citizenship behaviour. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 61–94.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. New York: Paulist Press.

Fields, J. W. F., Thompson, K. C. T., & Hawkins, J. R. H. (2015). Servant Leadership: Teaching the Helping Professional. Journal of Leadership Education, DOI: 10.12806/V14/I4/R2, https://journalofleadershiped.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/14_4_Fields.pdf.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. C. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

McCrae, E. B. (2020). Do Employees Leave Companies or Do Employees Leave Managers? Performance Improvement, 59(8), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21933

McKenzie, J., & Varney, S. (2018). Energizing middle managers’ practice in organizational learning. The Learning Organization, 25(6), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/tlo-06-2018-0106

Mid-Level Manager Competency Development Guide Mid-Level Manager Competency Development Guide Introduction and Overview. (2013.) https://www.leadingage.org/sites/default/files/Mid-Level%20Manager%20Competency%20Development%20Guide_Final_0.pdf

Mosley, P. A. (2008). Staying Successful as a Middle Manager. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Staying-Successful-as-a-Middle-Manager-Mosley/fea46ba4a7a32e302cbcce2714f26455bfdbe715

Parera L. B. and A. M. Fernández-Vallejo (2013). Changes in the Role of Middle Manager: A Historical Point of View - Volume 3 Number 3 (Jun. 2013) - ijiet. http://www.ijiet.org/show-38-315-1.html

Parris, D. L., & Peachey, J. W. (2012). A Systematic Literature Review of Servant Leadership Theory in Organizational Contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(3), 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1322-6

Sharma, G., & Good, D. (2013). The Work of Middle Managers. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 49(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886312471375

Osterman, P. (2015). The Truth about Middle Managers: Who They Are, How They Work, and Why They Matter [Review of The Truth about Middle Managers: Who They Are, How They Work, and Why They Matter].

Otocki, A. C., & Turner, B. F. (2020). Behavior Training is Not Enough: Empowering Middle Managers by Shifting Mindset. Military Medicine, 185(Supplement_3), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usaa134.

Ouakouak, M. L., Ouedraogo, N., & Mbengue, A. (2014). The mediating role of organizational capabilities in the relationship between middle managers’ involvement and firm performance: A European study. European Management Journal, 32(2), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.03.002

Van Der Weide, J. G., & Wilderom, C. P. (2004). Deromancing leadership: what are the behaviours of highly effective middle managers? International Journal of Management Practice, 1(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijmp.2004.004867

Voorn, B. (2018). Dependent leaders: Role-specific challenges for middle managers. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Dependent-leaders%3A-Role-specific-challenges-for-Voorn/12be426dcef9ecd30ed91e13a06c5aeda9189af2

Wang, S. (2013). Technology integration and foundations for effective leadership. Information Science Reference.