Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2025, vol. 54, pp. 41–59 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2025.54.3

Ahmad M. Mahasneh

Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences,

The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan

dahmadmahasneh1975@yahoo.com

Ahmad M. Gazo

Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Educational Sciences,

The Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan

Abstract. This study aims to pinpoint the emotional labor strategy most frequently used by teachers and gender differences identified in the emotional labor strategies. Furthermore, it examines the causal relationship between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout. The study sample comprised (720) teachers in Jordan who completed the Emotional Labor Instrument (ELI) and the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). The results show that suppression is the most common strategy teachers use, whereas surface acting is the least commonly used strategy. No differences in surface acting and emotional consonance were diagnosed according to gender. Female teachers used deep acting, suppression, surface acting, and deep-acting negative emotions more than their male counterparts. Finally, the results of the path analysis showed that surface acting, deep acting, and surface-acting and deep-acting negative emotions were all positively related with teacher burnout, while no relationship was detected between suppression, emotional consonance, and teacher burnout. The researchers’ recommendation is to study other factors, such as teacher competence, that may potentially affect their emotional labor strategies.

Keywords: relationship, emotional labor strategies, teacher burnout.

Santrauka. Straipsnyje nagrinėjama, kurias emocinio darbo strategijas dažniausiai naudoja mokytojai ir (ar) strategijų naudojimas priklauso nuo lyties. Be to, analizuojamas mokytojų emocinio darbo strategijų ir patiriamo perdegimo ryšys. Tyrime dalyvavo 720 mokytojų iš Jordanijos, jie užpildė Emocinio darbo instrumentą (angl. The Emotional Labor Instrument (ELI) ir Maslach perdegimo klausimyną (angl. Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Rezultatai atskleidė, kad dažniausiai mokytojų naudojama strategija yra slopinimas, o rečiausiai pasitelkiamas paviršutiniškas veikimas. Tyrime nenustatyta reikšmingų lyčių skirtumų pagal paviršutinišką veikimą ir emocinę dermę, tačiau moterys mokytojos dažniau nei vyrai pasitelkia autentišką veikimą, slopinimą, paviršutinišką veikimą ir patiria dėl autentiško veikimo kylančių neigiamų emocijų. Kelio analizės rezultatai rodo, kad paviršutiniškas veikimas, autentiškas veikimas ir dėl paviršutiniško bei autentiško veikimo kylančios neigiamos emocijos prognozuoja mokytojų perdegimą, o slopinimo, emocinės dermės ir mokytojų perdegimo sąsajos nėra reikšmingos. Ateities tyrimams rekomenduojame tirti kitų veiksnių, pvz., mokytojų kompetencijos, įtaką emocinio darbo strategijoms.

Raktažodžiai: ryšys, emocinio darbo strategijos, mokytojų perdegimas

________

Received: 11/07/2024. Accepted: 30/05/2025

Copyright © Ahmad M. Mahasneh

Jordan’s education system is widely regarded as one of the most progressive in the Middle East, particularly in terms of literacy rates and gender parity in educational access. Education is considered a key pillar of national development, and the Jordanian Government has made significant investments in the sector over the years. Compulsory education in Jordan begins at the age of six and continues for ten years, thus covering the primary and lower secondary levels. The literacy rate among the youth (ages 15–24) stands at nearly 99%, according to UNESCO (2022), thereby highlighting the success of these initiatives.

The education system in Jordan is composed of both public and private institutions, with the Ministry of Education (MoE) overseeing curriculum development, teacher training, and policy implementation. Public schools, which educate the majority of students, face challenges such as overcrowding, limited resources, and teacher burnout – which are issues that are exacerbated by the influx of refugee students, particularly from neighboring Syria (UNHCR, 2023).

Burnout as a concept was first introduced by Freudenberger in the early 1970s (Freudenberger, 1974). It is a state of fatigue or frustration that results from professional relationships that failed to produce the expected rewards (Freudenberger, 1974; Freudenberger & Michelson, 1980). Maslach (2015) later defined burnout as a psychological syndrome involving, in Maslach’s view, professional and emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a diminished sense of personal accomplishment. These symptoms have been noted particularly among various professionals such as teachers, police officers, lawyers, nurses, as well as other professionals working closely with others in challenging situations.

Burnout is defined as extreme fatigue, demoralization, dissatisfaction with one’s abilities, diminished occupational motivation, and reduced enjoyment of living. This diversity is due to the occupational conditions requiring face-to-face contact and the expectation of high performance of employees (Gündüz, 2004). Burnout is a syndrome affecting physical, academic, and social performance in teaching and other stressful, personalized occupations, depending on whether such reactions are appropriate or inappropriate under stressful conditions (Shin et al., 2014).

The results of burnout, stress, and decline in work performance not only affect the person who is suffering but also those who interact with him/her. The problems of burnout are particularly damaging for teachers. The negative consequences of burnout can affect not only teachers but also students, administrators, parents, and their jobs, yielding negative impressions on the people with whom employees come into contact (Schaufeli & Taris, 2005).

Burnout can also be defined as a syndrome resulting in emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (Maslach, 2015; Montgomery & Maslach, 2019). Emotional exhaustion is a feeling of extreme emotional stress and overstrain resulting in severely depleted emotional resources, while depersonalization is a disorder whereby feelings of inadequacy, reduced personal accomplishment and inability to successfully maintain a high standard of work dominate the employee and can be highly disturbing.

Previous research shows that burnout is a major concern which is still perceived as a serious issue nowadays. It has been studied in professions characterized by frequent and highly demanding social interactions, such as working in the health care sector, social services, or educational systems. These professional groups, particularly teachers, present a particularly high risk of burnout. The first type of burnout is emotional exhaustion It leads to higher levels of depersonalization and reduced feelings of personal accomplishment (Maslach et al., 1996; Montgomery & Maslach, 2019). In particular, emotional exhaustion appears to be the burnout component predictor to best signal work performance variance (Bordbar, 2008). Kumar and Shazania (2021) also showed the link between emotional exhaustion and job performance and its relation to employee turnover. Due to its overwhelming effects and excessive stress, teacher burnout has become one of the most intensively studied topics in educational psychology. This teaching burnout includes lower levels of job satisfaction (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010), lower levels of motivation toward teaching (Hakanen et al., 2006; Schaufeli & Salanova, 2007), lower self-efficacy (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000; Evers et al., 2002; Schwarzer & Hallum, 2008; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007, 2010), a greater level of doubts regarding the ability to teach effectively (Dicke et al., 2015; Evers et al., 2002; Schwaezer & Hallum, 2008; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2010), and higher levels of intention to leave the teaching profession (Leung & Lee, 2006).

Teacher burnout remains a critical concern within Jordanian schools, where high workloads, low salaries, and emotional strain contribute to a decreased job satisfaction and higher attrition rates (Abu-Tineh et al., 2011). Emotional labor significantly impacts teacher burnout in Jordan’s education system, particularly through strategies like surface acting (modifying outward emotions without internal change) and deep acting (aligning internal feelings with expected displays). Research indicates that surface acting is a strong predictor of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, which are key components of burnout (Yilmaz et al., 2015; Nath & Pandey, 2025). In the context of Jordan, systemic challenges such as high workloads, overcrowded classrooms, and the integration of refugee students have exacerbated these effects (Alghaswyneh, 2012).

Any cultural or social order has rules of conduct and standards which regulate behavior. In business, customers and clients need to be approached and received positively. This positive atmosphere helps to dispel negativity (Austin et al., 2008). In people-oriented organizations, whatever their thoughts may be, staff are required to obey company rules of conduct which consider the company goals better achieved by displaying appropriate reactions and feelings. This situation places the human emotional aspect at the forefront and stimulates a new field of interest for research.

While Hawthorne was the originator of the human relations movement, researchers contributed to our understanding of how past employees had reacted and felt during interactions in their work environment (Eroğlu, 2010). The term ‘emotional labor’ means employee reactions to prompt situations while working. Professionals would generally observe their natural, mannerly disposition and control of their emotions, except in certain circumstances demanding the expression of their emotional responses professionally. In any case, emotion would become a professional attribute, and their skill and achievement would be closely linked to how they use their emotions (Oral & Köse, 2011).

The concept of emotional labor was first defined by Hochschild in (Hochschild, 1983), in his book The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feelings. This book defined emotional labor as handling emotional expression through gestures or facial expressions by employees (Hochschild, 2012; Eroğlu, 2010; Kaya & Ӧzhan, 2012). In this particular context, emotional labor is demonstrated in face-to-face confrontations and conversations in the current environment (Kaya & Ӧzhan, 2012; Zapf et al., 2021). Likewise, emotional labor is a way of showing emotions companies want their staff to publicize but in a mannerly and controlled fashion (Morris & Fieldman, 1996; Töremen & Cankaya, 2008).

There are two origins of Hochschild’s theory of emotional labor: The Goffman Dramaturgical Theory and the Marxist Theory of Alienation (Turner & Stets, 2005). Based on the dramaturgical theory, Hochschild (2012) demonstrated the emotional rules in our societies, including feelings rules and expression rules. Feelings rules specify the appropriate feelings in a given social setting, whereas expression rules apply to the overt expressions and display of the appropriate feelings in the given social setting.

In order to fulfill this social obligation, employees are required to adopt the role of social actors, by adjusting their reactions, facial expressions, and body language to the social norm. Failure to do so will result in being labeled as a social deviant (Wharton, 2009). In order to avoid this labeling, employees need to conform to the social norm, which is an act of emotion management called emotion work. Hochschild identifies as two types: (1) surface acting (changing expression according to changing feelings) and (2) deep acting (changing feelings to reflect the changing emotion) (Hochschild, 2012). Every social actor will perform the emotion work to some extent throughout his life. However, Hochschild points out that, from the socialist point of view, emotion management in post-industrial societies is not only a personal choice in private life, but also a requisite in the workplace where it is done for a wage, and which is called emotional labor. Hochschild discovered that an increasing number of enterprises, particularly service-related ones, had no qualms about using employees’ apparent emotions to boost profits (Hochschild,1983). Consequently, staff are no longer able to show their true emotions. As an example, cabin staff are required by the airline to be friendly, smiling, and helpful toward passengers at all times because passenger comfort and relaxation are the main selling points of the airline (Hochschild, 2012). Therefore, showing one’s true feelings, rather than the ones required by management, will reveal emotional dissonance, the disparity between honest feelings and those required by the management (Hochschild, 2012). Showing one’s true feelings is regarded as emotional dissonance, which is an incongruence between the real feelings and apparent displays. The higher the degree of emotional dissonance is, the higher the degree of alienation, dehumanization, and depersonalization will be (Ashforth & Tomiuk, 2000; Diefendorff et al., 2008; Hochschild, 2012; Lewig & Dollard, 2003; Zapf et al., 2021).

Emotional labor studies can be grouped into two main categories: job-focused versus employee-focused approaches (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2006). The first category mainly prioritizes job characteristics linked to emotional labor, the frequency of customer interaction, the variety, duration, and intensity of emotions required during job-related interaction). The second approach emphasizes the emotional regulation process and the internal state when employees perform emotional labor. It emphasizes how emotion is managed (effort and control) (Yadav & Pandey, 2021). Similarly, emotional labor conceptualizations or measures have emphasized different aspects of emotional processes. In this context, Glomb and Tews (2004) distinguished three main perspectives: behavioral expression, emotional dissonance, and internal process. Following Hochschild (1983), several researchers defined emotional labor while emphasizing different aspects (Grandey & Melloy, 2017; Zapf, 2002). Although there is no commonly accepted definition of emotional labor, researchers agree on the assumption that individuals can regulate their emotions and expression of emotions at work. Various researchers adopted surface acting and deep acting as the two main strategies of emotion regulation (Brie et al., 2005; Brotheridge & Grandey, 2006; Brotheridge & Lee, 2002; Grandey & Melloy, 2017; Näring et al., 2006; Zammuner & Galli, 2005; Zapf, 2002), but they also added other strategies. Ybema and Smulders (2002) and Briët et al. (2005) mentioned suppression, that is, hiding negative feelings like anger or disappointment as the most appropriate regulating strategy. Furthermore, Briët et al. (2005) and Zammuner and Galli (2005) as well as Martínez-Iñigo et al. (2007) specified emotional consonance, which is, in fact, the absence of emotional labor. In the case of emotional consonance, the emotions, experienced by an employee, are completely consistent with what the job requires. Hochschild (2012) called this form “passive deep acting”, while Zapf (2002) used the term “automatic regulation”.

Emotional labor strategies are associated with many psychological variables such as burnout, which results from prolonged stress related to work intensity, leaving the individual incapable of functioning effectively (Cetin et al., 2018). This inability to deal with the negative stress conditions can be considered as the last stage of the process. In order to survive, people need jobs to earn money, but if the working conditions are poor, and the pay is inadequate, it will be difficult for employees to succeed against all the problems that face them, while battling against depersonalization and striving for personal accomplishment and competence because the feeling of emotional and physical exhaustion leads to a number of emotions and feelings, ultimately hurting one’s entire life (Maraşli, 2005). This situation can be described as a brief burnout. Burnout is common in professions entailing face-to-face interaction (Barutcu & Serinkan, 2008). The teaching profession is a commonly provided example. Although the reasons may differ, all teachers may likely experience work-related stress (Jennett et al., 2003).

The teaching process requires a great deal of emotional control. Teachers are expected to display a variety of emotions while avoiding over-expressing emotions, whether positive or negative, in order to better manage the classroom, achieve discipline, and interact with students, which ultimately leads to achieving the ultimate goals of the educational process. Hence, teacher engage in the emotional labor, and the cognitive reappraisal process is considered an effective method for reducing negative emotions and increasing positive emotions, and it exerts a less negative impact on the teachers, whereas suppression or attempts to eliminate negative emotional experiences and control consume a teacher’s energy and cognitive abilities needed to perform other activities, including the teaching itself (Lee et al., 2018).

Within the educational process, emotional labor is the process by which the teacher exerts effort to control, express, and manage their emotions and emotional expressions in accordance with the known standards and expectations regarding their profession as a teacher (Yin et al., 2013). In the light of the increasing pressures that teachers are exposed to, including job burdens, time constraints, and lack of social support for teachers, there is need to study the various factors that affect job satisfaction, and the teacher acceptance of the teaching profession, including burnout, which includes the teacher’s feeling of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment (Kim, 2016).

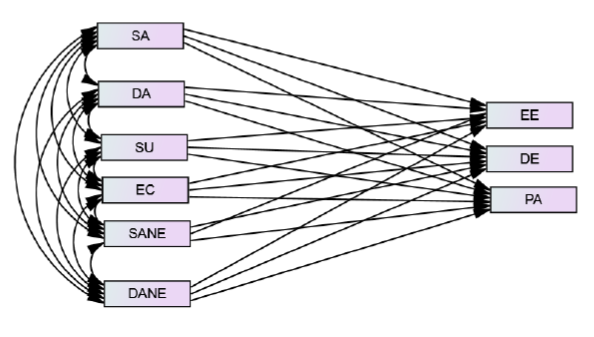

The current study model for the causal relationship between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout has been proposed as a consequence of previous studies (Akin et al., 2014; Anomneze et al., 2016; Baism et al., 2013; Khalil et al., 2017; Tsang et al., 2021; Yao et al., 2015; Zaretsky & Katz, 2019). It aims to connect emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout. Figure 1 shows the causal relationship between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout.

Note: SA: Surface acting, DA: Deep acting, SU: Suppression, EC: Emotional consonance, SANE: Surface acting negative emotion, DANE: Deep acting negative emotion, EE: Emotional exhaustion, DE: Depersonalization, PA: Personal accomplishment.

Emotional labor strategies such as surface acting and deep acting are frequently employed by teachers in order to cope with the psychological demands of their profession. These strategies involve either modifying outward emotional expressions without changing internal feelings (surface acting) or attempting to align internal emotions with expected displays (deep acting), both of which have been shown to impact teacher stress and burnout (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). Understanding these coping mechanisms within the socio-cultural and systemic context of Jordan’s education system is essential for developing targeted interventions and support structures that foster teacher well-being and retention.

Teachers in Jordan who frequently use surface acting report higher emotional exhaustion and depersonalization. For example, a 2015-dated study on Jordanian special education teachers found moderate emotional exhaustion and low personal accomplishment, with emotional intelligence inversely correlated with burnout (Al-Bawaliz et al., 2015). Over 95% of Jordan’s Tawjihi (12th-grade) teachers describe their work as stressful, citing factors like parental pressure, administrative demands, and large class sizes (Alghaswyneh, 2012). Refugee influx strained resources, thereby increasing teacher workloads and emotional demands (Alghaswyneh, 2012). Teachers often rely on indirect coping strategies (e.g., seeking social support) rather than direct actions to manage stress (Alghaswyneh, 2012). Emotional intelligence, including skills like empathy and emotional regulation, may mitigate burnout but is underutilized due to limited institutional training (Al-Bawaliz et al., 2015; Nath & Pandey, 2025). In summary, emotional labor – especially surface acting – interacts with Jordan’s systemic challenges to drive teacher burnout. Addressing this requires institutional recognition of emotional labor’s role and targeted support for educators. This study aims to answer the following questions:

Q1: What are the emotional labor strategies used by Jordanian teachers?

Q2: Do the emotional labor strategies differ by teacher gender?

Q3: What is the optimal level for causal relationship between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout?

This study is important for the following reasons: (1) it addresses one of the factors related to burnout syndrome among teachers, which is emotional labor, due to its role in promoting positive mental health for individuals. (2) It provides an opportunity for researchers in the Jordanian and Arab environment to become familiarized with the concept and strategies of emotional labor and to provide a measure of emotional labor in the Arab environment. (3) The research links the actual reality of the teacher and the psychological and professional pressures they face with the aim of finding solutions and making recommendations. (4) The research provides a comprehensive picture of the actual reality of job burnout and emotion labor among teachers in Jordan, which helps develop a better and clearer understanding that contributes to advancing the scientific research process. Finally, (5) the results of this study may be useful in assisting specialists and workers in the psychological and educational fields in designing and providing guidance interventions for teachers with the aim of raising their awareness of the nature of the psychological and emotional pressures they are exposed to during the educational process, while informing them how to manage their positive and negative emotions within the classroom environment.

This study uses a structural equation model to test the causal relationship between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout.

In the present study, 720 teachers in Jordan completed the study instruments. The study sample was derived from 45 schools affiliated with the Educational Directorate of Amman. The sample consisted of 400 (55.6%) males and 320 (44.4%) female teachers. 352 (48.9%) of the total were primary school teachers, and 368 (51.1%) were secondary school teachers. Their years of teaching experience ranged from 3 to 23, whereas their ages ranged from 23 to 55 years.

Emotional Labor Instrument (ELI): ELI was developed by Näring et al. (2011). It consists of 17 items distributed into six dimensions: surface acting (5 items, e.g., I put on a show at work), deep acting (3 items, e.g., I work hard to feel the emotions that I need to show to others), suppression (2 items, e.g., I hide my anger about something someone has done), emotional consonance (2 items, e.g., I react to patients’ [i.e., students’] emotions naturally and easily), surface acting negative emotion (3 items, e.g., I pretend that I am angry with a student), and deep acting negative emotion (2 items, e.g., I work hard to actually feel sad). Näring et al. (2011) checked the internal consistency by Cronbach alpha, which yielded (0.74, 0.73, 0.63, 0.52, 0.73, and 0.64), respectively, for surface acting, deep acting, suppression, emotional consonance, surface acting negative emotion, and deep acting negative emotion. To respond to the ELI items, a 5-point Likert scale was used, with ‘1’ referring to ‘never’ and ‘5’ representing ‘always’.

In the present study, the researchers checked the internal consistency by Cronbach alpha, and it was calculated as (0.79, 0.81, 0.73, 0.78, 0.80, and 0.71), respectively, for surface acting, deep acting, suppression, emotional consonance, surface acting negative emotion, and deep acting negative emotion.

MBI was developed by Maslach et al. (1996). It consists of 21 items distributed into three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (8 items, e.g., I feel used up at end of the workday), depersonalization (8 items, e.g., I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally), and personal accomplishment (5 items, e.g., I can easily understand how my recipient feels). Maslach and Jackson (1981) checked the internal consistency by using Cronbach alpha, and it was 0.90, 0.76, and 0.76, respectively, for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. To answer the MBI items, a 6-point Likert scale was used, with ‘1’ denoting ‘very mild’ and ‘6’ referring to ‘very strong’.

In this study, the researchers checked the internal consistency by using Cronbach alpha, and it was 0.76, 0.70, and 0.73, respectively, for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.

The data collection process lasted for two months. To analyze the data, SPSS was used for descriptive statistics, independent sample t-test, and Pearson correlation, while the Amos program was used for path analysis.

Q1: What are the emotional labor strategies used by Jordanian teachers?

To find out the emotional labor strategies used by the designated Jordanian teachers, the mean and standard deviations were used, as presented in Table 1.

|

Strategies |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

|

Surface acting |

3.07 |

0.91 |

|

Deep acting |

3.68 |

0.94 |

|

Suppression |

3.89 |

0.84 |

|

Emotional consonance |

3.78 |

0.92 |

|

Surface acting negative emotion |

3.49 |

1.13 |

|

Deep acting negative emotion |

3.35 |

1.25 |

Table 1 shows that the strategy, used by most teachers, was suppression (M = 3.89), followed by emotional consonance (M = 3.78), deep acting (M = 3.68), surface acting negative emotion (M = 3.49), deep acting negative emotion (M = 3.35), and surface acting (M = 3.07).

Q2: Do the emotional labor strategies differ by teacher gender?

To answer this question, descriptive statistics and independent sample t-tests for emotional labor strategies according to the teachers’ gender were used, as presented in Table 2.

|

Variables |

Gender |

M |

SD |

df |

t |

Sig |

|

Surface acting |

Male |

3.02 |

0.86 |

718 |

-1.409 |

0.15 |

|

Female |

3.12 |

0.98 |

||||

|

Deep acting |

Male |

3.60 |

0.88 |

718 |

2.049 |

0.04 |

|

Female |

3.75 |

1.01 |

||||

|

Emotional consonance |

Male |

3.92 |

0.78 |

718 |

0.910 |

0.36 |

|

Female |

3.86 |

0.90 |

||||

|

Suppression |

Male |

3.71 |

0.87 |

718 |

-2.575 |

0.01 |

|

Female |

3.88 |

0.96 |

||||

|

Surface acting negative emotions |

Male |

3.17 |

1.09 |

718 |

-8.844 |

0.00 |

|

Female |

3.89 |

1.06 |

||||

|

Deep acting negative emotion |

Male |

3.03 |

1.30 |

718 |

-7.986 |

0.00 |

|

Female |

3.75 |

1.05 |

The results show no differences in surface acting and emotional consonance according to gender. The female teachers used deep acting, suppression, surface acting, negative emotions, and deep acting negative emotion more frequently than the males. The t value scored (2.049, 2.575, -8.844, and -7.986), respectively, for deep acting, suppression, surface acting negative emotions, and deep acting negative emotion.

Q3: What is the optimal level for the causal relationship between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout?

Pearson correlation was used to answer this question, as shown in Table 3.

|

Variables |

Emotional exhaustion |

Depersonalization |

Personal accomplishment |

Burnout |

|

Surface acting |

0.24* |

0.32* |

0.07** |

0.37* |

|

Deep acting |

0.24* |

0.16* |

0.01 |

0.26* |

|

Suppression |

0.05 |

0.13* |

-0.12* |

0.04 |

|

Emotional consonance |

0.03 |

0.09 |

0.05 |

0.09* |

|

Surface acting negative emotion |

0.20* |

-0.05 |

0.37* |

0.29* |

|

Deep acting negative emotion |

0.19* |

-0.07** |

0.50* |

0.33* |

Note. *p = 0.01, **p = 0.05.

Table 3 shows a positive relationship between surface acting, deep acting, surface acting negative emotion, and deep acting negative emotion with teacher burnout. However, no relationship was found between suppression, emotional consonance, and teacher burnout.

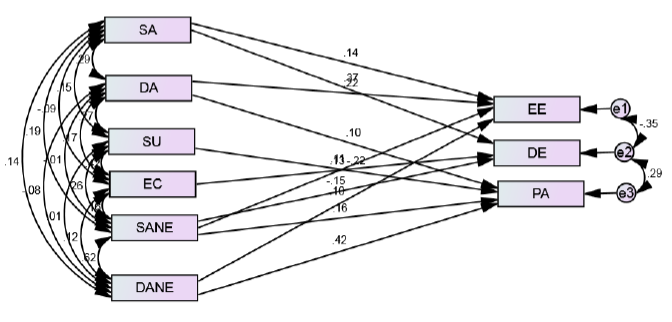

The results of the path analysis show the value of Chi-square = 10.273, df = 8, and sig = 0.24, the comparative fit index (CFI) = .998, Root mean square error of approximation (RMR) = 0.02, Goodness fit index (GFI) = .997, Normed fit index (NFI) = .993, and Root mean square residual (RMSEA) = 0.02. These values mean that the data match the model study. Based on the model modification indicators, the first model of the study was modified. Figure 2 shows the final model of causal relationships between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout.

Note. SA: Surface acting, DA: Deep acting, SU: Suppression, EC: Emotional consonance, SANE: Surface acting negative emotion, DANE: Deep acting negative emotion, EE: Emotional exhaustion, DE: Depersonalization, PA: Personal accomplishment.

|

Variable |

Unstandardized estimates (SE) |

Standardized |

P-value |

|

SA→EE |

.230(.06) |

0.140 |

0.00 |

|

SA→DE |

.431(.04) |

0.369 |

0.00 |

|

DA→EE |

.353(.05) |

0.221 |

0.00 |

|

DA→PA |

.163(.05) |

0.100 |

0.00 |

|

SU→PA |

-.398(.06) |

-0.217 |

0.00 |

|

EC→DE |

.152(.03) |

0.131 |

0.00 |

|

SANE→EE |

.151(.05) |

0.114 |

0.00 |

|

SANE→DE |

-.141(.03) |

-0.149 |

0.00 |

|

SANE→PA |

.224(.05) |

0.165 |

0.00 |

|

DANE→PA |

.518(.04) |

0.420 |

0.00 |

|

DANE→EE |

.127(.05) |

0.105 |

0.01 |

The results show a positive direct effect of surface acting on emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. There is also a positive direct effect of deep acting on emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment, a direct effect of suppression on personal accomplishment, a positive direct effect of emotional consonance on depersonalization, and a positive direct effect of surface acting negative emotion on emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. On the other hand, there is a negative direct effect of surface acting negative emotion on depersonalization and a positive direct effect of deep acting negative emotion on emotional and personal accomplishment.

The results of the first question showed that teachers most frequently used suppression, followed by emotional consonance, deep acting, surface acting negative emotion, deep acting negative emotion, and lastly, surface acting. This is constructive because engaging in deep acting and genuine emotion has a more positive impact on both their personal success and that of their organization. Consequently, teachers with high empathy naturally prefer to display deep and genuine behavior rather than surface acting because of the effect it has on the individual concerned and those in the school who only practice surface acting. Deep-acting emotional labor has a greater effect than surface acting does, or it has no effort of emotional labor whatsoever that impedes job performance.

Savas (2012) revealed the levels of emotional labor of school principals, respectively, as emotive effort, genuine acting, emotive conflict, and emotive dissonance. Yilmaz et al. (2015), in their study on teachers, also concluded that teachers showed their true emotions at the highest level, followed by deep, and then, surface acting emotional effort. In addition, the study demonstrated that people instinctively displayed deep and emotional behavior instantly and that managers who do not react genuinely and resort to displaying false feelings may strongly feel stress and exhaustion at the highest level (Humphrey et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2009).

Teachers’ emotional labor theory consists of three modes: surface acting, deep acting, and expression of spontaneously felt emotions. It was found that teachers used the expression of the naturally felt emotions most, followed by deep acting, whereas the least commonly used strategy was surface acting. Mou (2014) concluded that elementary and middle school teachers’ emotional labor consists of four expression modes: deliberative dissonance action, surface acting, deep acting, and expression of naturally felt emotions. He pointed out that teachers used expression of naturally felt emotions and active deep action most, and surface acting least of all. Contrarily, Xu et al. (2020) found that teachers used surface acting more than deliberative dissonance acting. Liu (2007) found discovered that few teachers used only one kind of emotional labor strategy, whereas most teachers often used two or more strategies. Hu et al. (2013) chose junior middle school teachers as their research subject and found that there were three kinds of teachers’ emotional labor strategy combinations: low deep acting, low expression of naturally felt emotions and high surface acting, medium level of surface acting, deep acting and high expression of naturally felt emotions, high deep acting, and low surface acting groups. The first strategy combination had the highest health risks for the teacher, while the other two combinations had more reduced health risk levels.

The results showed no differences in surface acting and emotional consonance according to genders. This result may be explained by the unified cultural factor among male and female teachers. Culture is one of the factors that influence emotional labor, as it is linked to socialization in terms of time and manner in which children are able to express their emotions; the process of regulating emotions and how they are expressed is influenced by an individual’s experience of emotions and the way they express them. It is also influenced by the culture and nature of the profession and institution in which individuals work. There are many professions, such as teaching, that involve dealing with and interacting with others, which requires teachers to have the ability to apply a number of rules specific to the profession in order to be able to master them and to deal with the accompanying pressures (Lv et al., 2012)

The results of the study question number two showed that female teachers used deep acting, suppression, surface acting negative emotions, and deep acting negative emotions more than their male counterparts. These gender differences in emotional labor strategies are due to the fact that females are more skilled than males in this regard; they engage in emotional regulation strategies more than males. This result is also demonstrated by females who are more able to correctly infer what other people are thinking or feeling, and women are also more likely to exert emotional labor strategies. The sociocultural theory explains emotions and personality manifestations between the two genders and describes how environmental, psychological, cultural, and social factors lead to variances in emotions between genders. Similar to gender theories, the sociocultural theory highlights how biological and social motives contribute to gender differences (Wood & Eagly, 2012). Meanwhile, Cetin et al. (2018) found that females engage in emotional labor strategies more than males.

Kiral (2016) discovered that no significant differences in the administrators’ level of emotional labor are based on gender. Similarly, Kaya and Özhan (2012) studied emotional labor and burnout and found no significant variation in the level of emotional labor based on the administrator’s gender. On the other hand, Liu (2007), in his study on primary and middle school teachers, found significant gender differences in the expression of naturally felt emotions. Female teachers scored higher than male teachers, but the gender differences were not significant in the surface-acting and deep-acting categories. Chen (2010) chose young university teachers for his study and found no significant gender differences in emotional labor, including surface acting, deep acting, and expression of naturally-felt emotions. However, males, in his study, scored significantly higher than females for surface acting. The female expression of naturally-felt emotions was significantly higher than that of males. Likewise, Tian et al. (2009) found no significant gender difference in the emotional labor of special education teachers. Nevertheless, surface acting and deep acting by females was higher than that by males, and the females’ emotional labor load was higher than that of their male counterparts.

The results showed no association between suppression, emotional consonance and teacher burnout. The researchers explain that the absence of any association between suppression, emotional consonance and teacher burnout, the teachers’ expression of their genuine emotion without their need for external or internal effort to modify their emotions or apparent expressions, has a minimal effect on the teachers, which reflects that neither male nor female teachers experience high levels of burnout. In addition, the teachers’ expression of their emotions in a genuine way strengthens their relationship with their students, makes them feel more credible in their field of work, and helps them feel success, accomplishment, and satisfaction, and found that teachers’ genuine emotion is associated with a low level of burnout.

The findings showed a negative direct effect of suppression on personal accomplishment. Suppression included the teachers’ ability to control and manage their emotions, which may result in their inability to deal effectively with all the situations they confront, and this inability is naturally associated with the teachers’ feelings of low personal accomplishment. However, there is a positive direct effect of emotional consonance on depersonalization. The emotional conscience includes the teacher’s ability to interact with students’ feelings naturally and easily, and to deal with their students’ positive feelings genuinely according to what the teacher feels and without altering or faking their feelings, thereby regarding their students in a positive rather than in a negative way.

The results showed that surface acting and surface acting negative emotion are associated positively with teacher burnout. There is also a positive direct effect of surface acting on emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. The researchers explain this result by pointing out that those teachers who use the surface acting strategy are more likely to feel emotional contradiction and lack of credulity. This expression is due to hiding their true emotions or trying to show positive emotional expressions, such as smiling, to show acceptance and satisfaction, which leads to burnout as a result of emotional exhaustion. The results also showed that deep acting and deep acting negative emotion are associated positively with teacher burnout, and that these factors had a positive direct effect on emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. The researchers explain this result by suggesting that deep acting is one of the emotional regulation strategies which involves depletion of teachers’ emotional and cognitive energies even despite the absence of a state of emotional contradiction among teachers. In addition, the effort made by teachers to make emotions suit different situations through the process of cognitive change and re-evaluation of the situation constitutes a great burden on the teachers from an emotional standpoint. It strongly depletes their emotional energies, leading to a high level of burnout.

While some studies found that surface acting indicated a positive prediction of emotional exhaustion, deep acting and expression of natural emotions were negative predictors (Basim et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2009; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2013). Sun (2013) found that the deep acting of the first test was negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion evidenced six months and one year later. Deep acting was significantly negatively correlated with emotional exhaustion in test three, and a reciprocal relation between emotional labor and emotional exhaustion was the outcome. Therefore, a relatively low possibility of emotional exhaustion can be inferred if teachers maintain a high level of deep acting in the coming year, whereas Omar et al. (2023) found personal accomplishment to be an added dimension of psychological burnout among specialist teachers in Egypt. Nonetheless, Saqr (2020) found no association between emotional labor strategies (surface acting, deep acting, and genuine emotions) and teacher burnout subscales (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment) among teachers in Egypt.

There may be other factors that affect emotional labor strategies, such as teacher competence, job satisfaction, motivations to teach, and teaching strategies which were not included within the scope of the study. To measure emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout, pen-and-paper, as a self-report method, was used, although this process may be affected by teachers’ bias or social aspiration. Emotional labor strategies are affected by many factors, including the marital status, gender, school level, number of the years of teaching experience, teacher competence, job satisfaction, and motivations to teach. In this study, differences in emotional labor strategies were revealed according to gender. Future studies may include more variables that affect emotional labor strategies.

The present study aimed to model the causal relationship between emotional labor strategies and teacher burnout. The results showed the effect of surface acting negative emotion on emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. At the same time, we observed a negative direct effect of surface acting negative emotion on depersonalization. We determined a positive direct effect of deep acting and deep acting negative emotion on emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment. Suppression had a negative direct impact on individual accomplishment. The emotional analysis of surface acting and consonance showed a positive direct impact on depersonalization. This means that teachers, engaging in high levels of emotional labor strategies, are exposed to high levels of burnout. Also, the results showed that female teachers, engaged in emotional labor strategies, are at higher levels than their male counterparts.

References

Abu-Tineh, A. M., & Khasawneh, & S., Khalaileh, H. A. (2011). Teacher self-efficacy and classroom management styles in Jordanian schools. Management in Education, 25(4), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020611420597

Akın, U., Aydın, ˙I., Erdoğan, Ç., & Demirkasımo, N. (2014). Emotional labor and burnout among Turkish primary school teachers. Australasian Educational Researcher, 41, 155–169. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13384-013-0138-4

Al-Bawaliz, M., Arabeyat, A., & Hamadneh, B. (2015). Emotional intelligence and its relationship with burnout among special education teachers in Jordan: An analytical description study on the Southern Territory. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(34), 88–95. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1086102.pdf

Alghaswyneh, S.A. (2012). Teacher stress among Tawjihi teachers in Jordan and their adopted coping strategies to reduce stress. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. https://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/17520/1/Final_Thesis_-_November_2012.pdf

Anomneze, E.A., Ugwu, D.I., Enwereuzor, I.K., & Ugwu, L.I. (2016). Teachers’ emotional labor and burnout: Does perceived organizational support matter. Asian Social Sciences, 12, 9–22.

Ashforth, B. E., & Tomiuk, M. A. (2000). Emotional labor and authenticity: Views from service agents. In S. Fineman (Ed.), Emotion in organizations (2nd ed. pp 184-203). London: Sage Publications.

Austin, E. J., Dore, C. P., & O’ Donovan, K. M. (2008). Association of personality and emotional intelligence with display rule perceptions and emotional labor. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 677–686.

Basim, H. N., Begenirbaş, M., & Yalçin, R. C. (2013). Effects of teacher personalities on emotional exhaustion: Mediating role of emotional labor. Educational Consultancy and Research Center, 13, 1488-1496.

Barutçu, E., & Serinkan, C. (2008). Burnout syndrome as one of the important problems of today and research in Denizli. Ege Academic Review,8(2),541-561.

Bordbar, A. R. (2008). Job burnout and how to deal with it. Reform and Education, 74, 12–26.

Briët, M., Näring, G., Brouwers, A., & van Droffelaar, A. (2005). Emotional labor: The development and validation of the Dutch questionnaire on emotional labor. Description: Time for Psychology and Health, 33(5), 318–330.

Brotheridge, C., & Grandey, A. (2006). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives on “People work”. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1),17–39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1815

Brotheridge, C., & Lee, R. T. (2002). Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(1), 57–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.7.1.57

Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2000). A Longitudinal Study of Teacher Burnout and Perceived Self-Efficacy in Classroom Management. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(2), 239–54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00057-8

Cetin, I., Icoz, O., & Gokdeniz, A. (2018). Factors affecting the emotional labor in food services: The case of van as a tourism destination. Turizam, 22(4), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.5937/turizam22-19040

Chau, S. L., Dahling, J. J., Levy, P. E, Diefendorff, J. M. (2009). A predictive study of emotional labor and turnover. Journal Organizational Behavior, 30(8),1151–63.

Chen, X. N. (2010). The empirical study of Yong University teachers’ emotional labor. Heilongjiang Researches on Higher Education, 12, 23–26.

Dicke T., Parker P. D., Holzberger D., Kunter M., Leutner D. (2015). Beginning teachers’ efficacy and emotional exhaustion: latent changes, reciprocity, and the influence of professional knowledge. Contemporary Educational Psychology, ٤١, ٦٢–٧٢. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.11.003

Diefendorff, J. M., Richard, E. M., & Yang, J. (2008). Linking emotion regulation strategies to affective events and negative emotions at work. Journal Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 498–508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.09.006

Eroğlu, E. (2010). Effects of organizational communication on the management of the labors’ expressing their emotions. Selçuk University Faculty of Communication Academic Journal, 6, 18–33.

Evers, W. J. G., Brouwers, A., & Tomic, W. (2002). Burnout and Self-Efficacy: A Study on Teachers’ Beliefs when Implementing an Innovative Educational System in the Netherlands. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(2), 227–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/000709902158865

Freudenberger, H. J. (١٩٧٤). Staff burnout. Journal of Social Issues, 30, 159–165.

Freudenberger, H.J., & Richelson, G. (1980). Burnout: The- cost of & achievement. Garden -City, NY: Doubleday.

Glomb, T. M., & Tews, M. J. (2004). Emotional labor: A conceptualization and scale development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 1–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00038-1

Grandey, A., & Melloy, R. (2017). The state of the heart: emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 407–422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000067

Gündüz, B. (2004). Exhaustion in primary school teachers. Journal of Education Faculty, 1(1), 152–166.

Hakanen, J.J., Bakker, A. & Schaufeli, W. (2006). Burnout and engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 495–513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hochschild, A.R. (2012). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Oakland: University of California Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/9780520951853

Hu, Y. H., Cao, X. M., & Luo, Z. H. (2013). What is composite mode of junior middle school teachers’ the emotional labor strategy and how to manage teachers. Modern Primary and Secondary Education, 4, 81–84.

Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., & Hawver, T. (2008). Leading with emotional labor. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810850790

Jennett, H. K., Harris, S. L., & Mesibov, G. B. (2003). Commitment to philosophy, teacher efficacy, and burnout among teachers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 583–593. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JADD.0000005996.19417.57

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Rubenstein, A. L., Long, D. M., Odio, M. A., Buckman, B. R., Zhang, Y., et al. (2013). A meta-analytic structural model of dispositonal affectivity and emotional labor. Personal Psychology, 66, 47–90. doi: 10.1111/peps.12009

Kaya, Ö., & Özhan, Ç.K. (2012). Emotional labor and burnout relationship: A research on tourist guides. Journal of Labor Relation, 3, 109–130.

Khalil, A., Khan, M.M., Raza, M.A., & Mujtaba, B.G. (2017). Personality Traits, Burnout, and Emotional Labor Correlation among Teachers in Pakistan. Journal of Service Science Management, 10, 482–496. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jssm.2017.106038

Kim, Y. (2016). Emotional labor and burnout among public middle school teachers in South Korea (٢٠١٦٠٤٢٦٢٣١٨) [Master’s thesis, University of Jyväskylä]. JYX Digital Repository.

Kiral, E. (2016). Psychometric properties of the emotional labor scale in a Turkish sample of school administrators. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 63, 71-88. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2016.63.5

Kumar, S., & Shazania, S. (2021). The effect of emotional exhaustion towards job performance. Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, 27, 54–72.

Lee, M., Pekrun, R., Taxer, J. L., Schutz, P. A., Vogl, E., & Xie, X. (2016). Teachers’ emotions and emotion management: Integrating emotion regulation theory with emotional labor research. Social Psychology of Education, 19(4), 843–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9359-5

Lewig, K. A, & Dollard, M. F. (2003). Emotional dissonance, emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in call center workers. European Journal Work and Organizational Psychology. 12(4), 366–392. doi:10.1080/13594320344000200

Leung, D. Y. P., & Lee, W. W. S. (2006). Predicting intention to quit among Chinese teachers: differential predictability of the components of burnout. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 19, 129–141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10615800600565476

Liu, Y. L. (2007). Research on teacher’s emotion work in elementary and middle school. Ph.D. Thesis, Chongqing: Southwest University.

Liu, W. L., Chen, R., Lou, X. M., Liu, X., & Liu, Y. L. (2013). Relationship between primary and middle school teachers’ emotional work strategies and occupational well-being: On moderating effects of psychological capital. Journal of Southwest China Normal University: Natural Science Edition, 38, 152–157.

Lv, Q., Xu, S. & Ji, H. (2012). Emotional labor strategies, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intention: an empirical study of Chinese hotel employees. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 11(2), 87–105.

Maraşlı M. (2005). Burnout levels of high school teachers according to some features and learned strength levels. Turkish Doctors Union Journal of Occupational Health and Safyey,3, 27–33.

Martinez-Iñigo, D., Totterdell, P., Alcover, C. M., & Holman, D. (2007). Emotional labor and emotional exhaustion: Interpersonal and intrapersonal mechanisms. Work & Stress, 21, 30–47. doi:10.1080/02678370701234274

Maslach, C. (2015). Burnout, Psychology of. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition. 2, 929–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.26009-1929.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E. & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory. (3rd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Pres.

Montgomery, A., & Maslach, C. (2019). Burnout in Health Professionals, 3rd ed.; Ayers, S., McManus, C., Newman, S., Petrie, K., Revenson, T., Weiman, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Morris, J. A., & Feldman, D. C. (1996). The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Academy of Management Journal, 21, 989–1010.

Mou, T. Y. (2014). The research on relationship among primary and secondary school teachers’ psychological capital, emotion labor strategies and job burnout. Master’s Thesis, Changsha: Hunan Normal University.

Näring, G., Briët, M., & Brouwers, A. (2006). Beyond demands-control: Emotional labor and symptoms of burnout in teachers. Work & Stress, 20(4), 303–315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02678370601065182

Näring, G.W.B., Canisius, A.R.M, & Brouwers, A. (2011). Measuring emotional labor in the classroom: The darker emotions. In A. Caetano., S. Silva, & M.J. Chambel (eds). New challenges for a healthy workplace in human services. (series: Organizational Psychology and Health Care, vol. 6, edited by W. Schaufeli & J. M. Peiro). (pp. 127–139). Munich: Rainer Hampp Verlag.

Nath, R., & Pandey, C. P. (2025). The Hidden Burden: Emotional Labor and Well-Being of School Teachers. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 51(2), 500–510. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajess/2025/v51i21802.

Omar, M., Ibrahim, T., & Radi, M. (2023). Psychological burnout and its relationship to professional self-esteem, emotional labor and motivation among a sample of especial education teachers. Journal of Psychological Counseling, 74, 59–122.

Oral, L., & Köse, S. (2011). A research on physicians use of emotional labor and the relationship between their job satisfaction and burnout levels. Suleyman Demirel University Journal of Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, 16, 463–492.

Saqr, H. (2020). Emotional labor and its relationship to psychological burnout among teacher. Educational and Psychological Studies, 108, 291–340.

Savaş, A. C. (2012). The effect of school principals’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor competencies on teachers’ job satisfaction levels. Doctoral dissertation, Gaziantep University-Gaziantep. National Thesis Center of the Council of Higher Education.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2007). Work engagement: An emerging psychological concept and its implications for organizations. In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.), Research in Social Issues in Management (Volume 5): Managing social and ethical issues in organizations (pp. 135–177). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishers.

Schaufeli, W.B. & Taris, T.W. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: Common grounds and worlds apart. Work and Stress, 19(3), 256–262

Schwarzer, R., & Hallum, S. (2008). Perceived teacher self-efficacy as a predictor of job stress and burnout: Mediation analyses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 152–171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00359.x

Shin, H., Park, Y. M., Ying, J. Y., Kim, B., Noh, H., & Lee, S. M. (2014). Relationships between coping strategies and burnout symptoms: A meta-analytic approach. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(1), 44- 56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0035220

Skaalvik, E.M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 611–625. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.611

Skaalvik E. M., & Skaalvik S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001

Sun, Y. (2013). The developmental characteristics of preschool teachers’ emotional labor and its relation to emotional exhaustion. Ph.D. Thesis, Changchun: Northeast Normal University.

Tian, X. H., Zhou, H. Y., & Chen, D. W. (2009). A Survey on emotional labor of special education teachers. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 8, 50–56.

Töremen, F., Çankaya, İ. (2008). An effective approach at management: Emotional management. Theoretical Educational Sciences, 1, 33–47.

Tsang, K.K., Teng, Y., Lian, Y., Wang, L. (2021). School Management Culture, Emotional Labor, and Teacher Burnout in Mainland China. Sustainability, 13, 9141. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su13169141

Turner, J. H, & Stets, J. E. (2005). The sociology of emotions. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. PP. 36–46.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2022). Jordan: Education and Literacy. Retrieved from https://uis.unesco.org/en/country/jo

UNHCR. (2023). Education in Jordan. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/jo/education

Wharton, A.S. (2009). The Sociology of Emotional Labor. Annual Review Sociology, 35, 147–165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115944

Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2012). Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 55–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394281-4.00002-7

Xu, S. T., Cao, Z. C., & Huo, Y. (2020). Antecedents and outcomes of emotional labor in hospitality and tourism: A meta-analysis. Tourism Management, 79, 104099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman. 2020.104099

Yadav, M., & Pandey, A. (2021). An exploring of relationship between emotional labor, it antecedents and outcomes. Webology, 18(6), 2817–2831.

Yao, X., Yao, M., Zong, X., Li, Y., Li, X., Guo, F., & Cui, G. (2015). How school climate influences teachers’ emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of emotional labor. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12, 12505–12517. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph121012505

Ybema, J., & Smulders, P. (2002). Emotional demand and the need to hide emotions at work. Gedrag en Organisatie, 15(3), 129-46.

Yilmaz, K.; Altinkurt, Y.; Guner, M.; & Sen, B. (2015). The Relationship between Teachers’ Emotional Labor and Burnout Level. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 59, 75–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2015.59.5

Yin, H., Lee, J. C. K., Zhang, Z., & Jin, Y. (2013). Exploring the relationship among teachers’ emotional intelligence, emotional labor strategies and teaching satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35, 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.06.006

Zammuner, V. L., & Galli, C. (2005). Wellbeing: Causes and consequences of emotion regulation in work settings. International Review of Psychiatry, 17(5), 355–364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540260500238348

Zapf, D. (2002). Emotion work and psychological well-being: A review of the literature and some conceptual considerations. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 237–268.

Zapf, D., Kern, M., Tschan, F., Holman, D., & Semmer, N. K. (2021). Emotion work: A work psychology perspective. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8, 139–172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062451

Zaretsky, R., & Katz, Y.J. (2019). The relationship between teachers’ perceptions of emotional labor and teacher burnout and teachers educational level. Athens Journal of Education, 6(2), 127–144. http://dx.doi.org/10.30958/aje.6-2-3