Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia ISSN 1392-5016 eISSN 1648-665X

2024, vol. 53, pp. 57–71 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ActPaed.2024.53.5

Mateusz Kamionka

Department of Polish-Ukrainian Studies

Faculty of International and Political Studies

Jagiellonian University, Poland

Email: mateusz.kamionka@uj.edu.pl

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7316-145X

Abstract. After the outbreak of a full-scale war in Ukraine, thousands of children – refugees from Ukraine – appeared in Polish schools. On 1 September 2022, there were about 800,000 school-age children and teenagers from Ukraine in Poland. This caused changes in schools where, previously, the vast majority of students were Poles, especially in small towns and the countryside. Considering the above, the article will present the results of a pilot study from the town of Olkusz which can be called a ‘typical’ medium-sized Polish town. The qualitative research involved 280 young people aged 16–21. In the study, they were asked about their attitudes towards their friends from Ukraine and about their situation at school. The research is a pilot study; according to the author, the relationship between students from Poland and Ukraine in Polish schools has not yet been sufficiently explored. The results show that young people, despite their experience in helping Ukraine, are not particularly interested in contact with their peers from Ukraine and in their culture, but, on the other hand, they would not mind if their friend had a girlfriend or boyfriend from Ukraine. They also see that their Ukrainian friends have language problems, but there is no substantial language barrier between them. Research also shows the need for young people to learn about intercultural issues. Poland, accepting thousands of immigrants, like other Central European countries, must prepare for a gradual change in educational policy.

Keywords: Immigrant, Ukraine, refugees, school, intercultural education.

Santrauka. Ukrainoje prasidėjus didžiulio masto karui, Lenkijos mokyklose atsidūrė tūkstančiai vaikų pabėgėlių iš Ukrainos. 2022 m. rugsėjo 1 d. Lenkijoje gyveno apie 800 000 mokyklinio amžiaus vaikų ir paauglių iš užpultos šalies. Tai lėmė pokyčius mokyklose, nes iki tol jose didžiąją daugumą mokinių sudarydavo lenkai, ypač mažuose miestuose ir kaimuose. Todėl straipsnyje pateikiami Olkušo mieste atlikto bandomojo tyrimo rezultatai – šį miestą galima vadinti tipiniu vidutinio dydžio Lenkijos miestu. Kokybiniame tyrime dalyvavo 280 16–21 metų jaunuolių. Tyrimo metu jų buvo klausiama apie požiūrį į draugus iš Ukrainos ir apie padėtį mokykloje. Tyrimas bandomasis – autoriaus nuomone, Lenkijos mokinių ir mokinių iš Ukrainos santykiai Lenkijos mokyklose dar nėra pakankamai ištirti. Rezultatai atskleidė, kad jaunuoliai, nepaisant jų patirties padedant Ukrainai, nėra itin suinteresuoti bendrauti su bendraamžiais iš Ukrainos ir domėtis jų kultūra, tačiau jie neprieštarautų, jei jų draugai turėtų merginą ar vaikiną iš Ukrainos. Jie taip pat mato, kad ukrainiečiai draugai patiria sunkumų dėl kalbos, tačiau tuo pat metu jie nejaučia esminio kalbos barjero. Atskleista ir tai, kad jaunimui reikia ugdyti tarpkultūriškumą. Tūkstančius imigrantų priimanti Lenkija, kaip ir kitos Vidurio Europos šalys, turi rengtis laipsniškiems švietimo politikos pokyčiams.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: imigrantai, Ukraina, pabėgėliai, mokykla, tarpkultūrinis ugdymas.

______

Received: 03/06/2024. Accepted: 20/11/2024

Copyright © Mateusz Kamionka

On 24 February 2022, the largest military operation since the end of World War II began on European soil. The Russian Federation launched the so-called ‘Special Military Operation’, which, however, in the eyes of the public of most countries worldwide, was nothing short of a full-scale war. From the first hours of the conflict, millions of refugees from war-torn Ukraine flowed to the countries neighbouring the attacked state. The humanitarian crisis that would theoretically arise on their borders could cause Ukraine to paralyse their logistics and, as an aftermath, Ukraine might capitulate faster, which was probably what Russia had been counting on. Before the operation began, Russia and Belarus had ‘tested’ Poland’s eastern border by sending (and helping with coming to Belarus) immigrants from countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. In a poll conducted by the Institute for Market and Social Research (IBRiS) for Polsat News, respondents in Poland were asked in 2021 “Should Poland let in migrants and refugees?” Almost 55% said that it should not, while 38% thought that it should. Men (62%), inhabitants of rural areas, and people with lower education levels were most likely to say it should not (Tilles, 2021). The above research could suggest that Poland would not accept an influx of refugees from Ukraine on such a massive scale. But, in February 2022, the situation was completely different, and on the first day of Russian aggression, Poland opened its borders for Ukrainian refugees (Fallon, 2022).

Poland is a state with a high number of displaced persons from Ukraine. This relates to the proximity of the Polish-Ukrainian border and the possibility of travelling back and forth to Ukraine from Poland1. In June 2023, there were 974,375 Ukrainian nationals actively registered for temporary protection in Poland (Zymnin et al., 2023, p. 6). The highest number of Ukrainian refugees in Poland are women (80%), often with children under 18 years old (53%). Most of them are of an economically active age and have a university degree (61%) (Ukraine Refugee Pulse, 2023). A very high percentage of refugees staying in Poland are the youth. On 1 September 2022, there were about 800,000 school-age children from Ukraine in Poland. According to the Polish Minister of Education Przemysław Czarnek, the current number of Ukrainian students in all types of Polish schools was about 200,000, of whom, approx. 40,000 were enrolled in Polish kindergartens and 160,000 in schools (Ile dzieci i młodzieży…, 2022). The education system in Poland offers three options for Ukrainian students:

• be part of the Polish education system;

• have online lessons and continue studies in the Ukrainian system;

• choose a hybrid mode and try to accommodate those two systems (students can have lessons in Polish schools, and then in the afternoon take part in online lessons in Ukrainian online schools) (Sewastianowicz, 2023).

According to the information from the (Polish) Mazowieckie Voivodeship school board, “after receiving the PESEL number (Polish individual identification number), a child is covered by the school obligation, which, admittedly, can be carried out in a remote Ukrainian school;” “A caregiver is enough if the student will go with him or her to the department of education with competence over their place of residence and submit the appropriate application about their statement” (Grudzińska, 2022). Until now (1 June 2023), a significant percentage of Ukrainian youth has returned to non-occupied or de-occupied territories of Ukraine. A year after the Russian aggression against Ukraine, almost 1 million Ukrainian citizens, mainly women and children, benefit from temporary protection in Poland. In total, 1.4 million people have valid residence permits in this country. Since 24 February 2022, the migration situation in Poland has been dominated by an increased influx of Ukrainian citizens. They are by far the largest group of foreigners in Poland, accounting for slightly more than 80% of the total number of foreigners who have settled here. Most Ukrainians stay in Poland by using temporary protection, which is confirmed by the receipt of a PESEL under the Act on Assistance to Ukrainian Citizens in Connection with the Armed Conflict on the Territory of That State. Currently, almost 1 million people are registered on this basis, with women and children accounting for about 87% of this group. Children and teenagers are approx. 43% of citizens of Ukraine with PESEL numbers. Among adults, women are 77% of all Ukrainian people in Poland (Obywatele Ukrainy w Polsce, 2023). Those numbers show, in theory, how many young Ukrainians entered the Polish education system. However, according to research, the attitude of Poles towards refugees is gradually changing. In response to the question “Would it be good or bad for Poland if people from Ukraine who are currently in Poland were to stay here for many years?” asked by the Ipsos Survey (CATI) for OKO.press and TOK.FM on 20–23 March 2023, the attitudes of the younger Polish women (aged 18–39), who are most discouraged by refugees, is surprising. As many as 48% of them assess the permanent residence Ukrainians in the country as ‘unfavourable’ or ‘very unfavourable’. On the other hand, the answer ‘favourable’ was chosen by 44% of young women, standing out from the attitudes of other women. Among those aged 40–59, positive attitudes still prevail – at 51% – over negative ones – at 37% (Theus, 2023). This is why it is of interest to investigate the attitude of young Poles towards Ukrainian refugees in schools, to check how the relations between youngsters are shaped in the first stage of building intercultural relations. The survey was conducted in the powiat2 town Olkusz located in Lesser Poland, near Kraków, in which 280 students aged 16–21 participated. The topic of school students with an immigrant background was already popular before because of the youth undertaking academic studies in ‘Old Europe’ (Asghari, 2022; Berggren et al., 2021; Atanasoska and Proyer, 2018), notably, in countries which accepted most of the immigrants in the latest refugee crises in 2015, such as Turkey (Soylu et al., 2020). In central Europe, this topic was not explored substantially because countries of the region were not the target but rather a transit point for refugees who wanted to live in Europe. The situation radically changed in February 2022.

Until 2022, Poland, especially its small towns, was relatively mono-national, and national and ethnic minorities were a negligible phenomenon. The change that occurred with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine transformed the image of a typical Polish county school. This led to a discussion about intercultural education and the level of tolerance of the Polish youth towards refugees, especially when new peers with refugee experience appeared at school. The main approach to the analysed results of the survey is the thesis that intercultural education, which can already start at the stage of building mutual relations between youngsters, shows them how to be tolerant and open-minded to one another at school. That is very important at the first stage of the coexistence of young students. Culturally responsive pedagogy is a student-centred approach to teaching that includes cultural references and recognises the importance of students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences in all aspects of learning (Ladson-Billings, 1995). The Polish researcher Jerzy Nikitorowicz believes that the basic purpose of intercultural education is to shape the needs of entering cultural borderlands to stimulate cognitive and emotional needs, such as surprise, discovery, dialogue, negotiation, exchange of values, and tolerance. This allows people of different races, religions, nationalities and traditions to communicate on an international scale and be open to the world. According to Nikitorowicz (2005, p. 124), intercultural communication means “transcending one’s own culture, going to borderlands, establishing cultural contacts in order to become internally richer and to consciously orient culture in a direction that allows comparisons and, as a result, will lead to cultural pluralism.” A similar approach is also taken by Geneva Gay (2010) who defines culturally responsive education as the use of cultural knowledge, previous experiences and performance styles to make learning more relevant and effective for students. She underlines that the elementary idea in the model of culturally responsive education is that culture influences the learning styles of students. On the other hand, the Polish specificity slightly departs from the classic approach to intercultural education. It remains an open question whether the refugees will return home at some point (which partly happened already after the collapse of the Russian offensive). On the other hand, Poland and Ukraine are similar in terms of culture (Prokopenko & Kryvoruchko, 2017), even taking into account their common history as part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This reinforces the deeply rooted post-colonial attitudes not only in schools but also in relationships between adults, mostly in connection to difficult historical issues between those two nations. Also, students from Ukraine have problems with the Polish language (Levchuk et al., 2022), but it should be perceived as a ‘problem’, not as a lack of knowledge of the language (because they do not have a good accent, or they make mistakes), which will be discussed in the next part of the article. It is very important because – as Hassan Sharif (2016) underlines – immigrant students’ inability to use the official language at school at the same level as native students leads to their knowledge in many subjects being undervalued. A more important problem, however, may be that Polish students do not understand the reasons for the stay of their Ukrainian peers in Poland, and why Poland as a country provides so much help to Ukraine. In recent years, Ukrainians in Poland have been perceived more as economic migrants, which gave rise to many stereotypes and anti-Ukrainian sentiments among Polish citizens (with stereotypes of taking jobs from native-born workers etc.), while, currently, emigration has a completely different background, which often causes problems with understanding the wider situation. Young people may also fail to understand the attention given to students from Ukraine by their teachers, but also by the general public, which is due to their refugee status, especially, which should be emphasised, in the era of propaganda attacks, which are also directed against the youngest on the Internet, where refugees from Ukraine are presented not as war victims, but rather as aggressors (especially by foreign propaganda).

The article is the result of a pilot study aimed at answering the question about the attitude of Polish school students towards their Ukrainian peers (as illustrated by a case study of Olkusz town). Nationwide research confirms changes in attitudes towards refugees, especially among young people. There is also the issue of attention given to young refugees not only by the authorities and schools but often even by the students themselves. The results will confirm or disprove the hypotheses that the first national differences are observed and conflicts occur at the school level. The main hypothesis of the article is that Olkusz school students do not have hostile attitudes towards their Ukrainian peers at school even in the absence of activities related to intercultural education in the Polish education system.

The students who participated in the research are residents of the town of Olkusz and the surrounding villages. Olkusz is a town of nearly 40,000 inhabitants in the Małopolskie (Lesser Poland) Voivodeship in southern Poland. It can safely be called a ‘typical’ Polish city. The questionnaire was sent to all schools of the Olkusz district with the help of the local administration and in cooperation with schoolteachers from schools that took part in the study. The survey was completed by students between 23 and 30 May 2023. A total of 280 students participated in the study, of whom almost 97% attend schools in the Olkusz powiat. The survey was conducted online (CAWI), it was fully anonymous and in compliance with full-scale ethical standards. The questionnaire was posted on an open group for school students, and aimed at people over 16 years of age, and the questions did not concern intimate topics. Participation was completely voluntary, and the study itself was agreed upon with the teaching staff of the schools involved in the research. Students were asked to fill in the survey in their free time, and they received information for what reason they were doing the task. Over 91% of the respondents were students aged 16–18, and 6.5% were 19–21-year-olds and were probably students in the last year of technical high schools (‘technikum’, which in Poland takes longer to graduate from than secondary schools of general education – ‘liceum’). This shows that virtually all people participating in the study were still at school. The surveys were sent not only to schools and form groups in which students from Ukraine were studying, but also to schools where the number of students from Ukraine was not large. Taking into account all schools and form groups in the Olkusz district, the research can be considered representative of the town of Olkusz. The questionnaire was prepared with Google Forms and sent to all students in Olkusz, it contained 36 questions, of which, four were about the respondents. Almost 57% were boys, whereas 43.4% were girls, 96.4% of them were studying in the Olkusz region, and almost 92% were aged 16–18. Interestingly, 49.5% of them lived in villages, and only 21.5% were from towns between 30 and 100 thousand inhabitants. Summing up, the research is not representative of all students nationwide. Nevertheless, it provides an engaging approach to the topic of the attitudes of Polish students to their peers from Ukraine in schools.

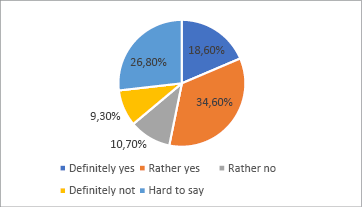

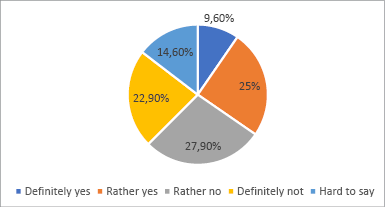

For the analysis in this article, 16 questions from a CAWI method questionnaire were chosen which most fit the topic of the attitudes of youth to their peers from Ukraine. The first question the young people were asked was: In your opinion, should Poland receive Ukrainian refugees from conflict areas? As can be seen in the first diagram, about 53% of the surveyed young people believe that refugees from war zones should be received, while 20% have a different opinion. Interestingly, almost 27% of students could not answer this question. The CBOS research centre asked Poles a similar question in April 2023, and the results were significantly different. Then, seventy-three per cent of those surveyed believed that refugees should be received (25% definitely yes, 48% rather yes) – which is already 10 percentage points higher than one month before in a similar CBOS survey (conducted in March 2023), in which 19% were opposed (14% rather opposed, and 5% definitely opposed), which was 8 percentage points less than in the case of students. This was the highest result since the outbreak of the war, but it was very similar to the research conducted in schools. Eight per cent of the respondents had no opinion, which is almost 20% less than in the case of students) (W Polsce ubyło…, 2023). It should be underlined that almost 27% of students who do not have an opinion on this topic during their school education should be educated about the situation of migrants. This question gives an insight into the situation and shows the attitude of young people towards the issue being discussed.

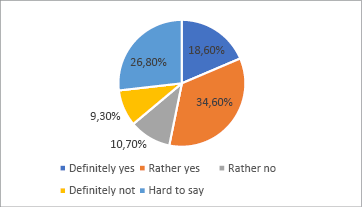

The next question was In your opinion, what is the attitude of Poles towards refugees from Ukraine in general? It was supposed to show not only the opinions of students about the attitudes of Poles towards Ukrainians, but also to find out what their attitudes are, which they could reveal when the question was asked not about them, but rather about the collective. The results are also somewhat different, as, according to the respondents, only 25% of Poles react positively to refugees from Ukraine in Poland, almost 30% of reactions are neutral, and as many as 27% are negative. As many as 18.6% of young people answered: ‘hard to say’. Those numbers are probably also related to the massive influence of anti-Ukrainian propaganda and anti-Ukrainian content that young people can find on the Internet. The negative content about Ukrainians on the Internet forms their views about the collective attitude of Poles.

The young people were also asked about the further fate of refugees from Ukraine in Poland; they were enquired if they think that Most refugees from Ukraine who found shelter in Poland will come back to Ukraine after the end of the war. According to the respondents (43.6%), the immigrants will stay in Poland, and only 22.5% of students believe otherwise. On the other hand, almost 34% of the respondents have no opinion. The result, of course, is not surprising, since the study was carried out almost a year and a half after the initiation of the Russian attack on Ukraine, and most of the refugees who stayed in Olkusz either stayed permanently, starting a new life, or came from areas still occupied by the Russian army and had no way back at that moment. It is worth emphasising that the presence of Ukrainian citizens in Poland clearly increases the need to introduce intercultural education in schools.

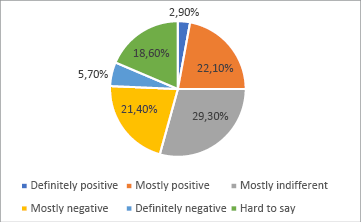

It was also of interest to know the opinions of young people about their attitudes towards their peers from Ukraine (Figure 3). When asked how they would describe their relations with peers from Ukraine, over 50% of students answered that they were positive or rather positive.

Only over 13% of the respondents have negative attitudes with a large number of students answering Hard to say, which may be the result of the lack of contact with peers from Ukraine (e.g., when there is no one from Ukraine in their form group). The result is optimistic, despite the 13% of negative responses. It is therefore worth including topics related to intercultural education in the curriculum, in order to better familiarise young people with the culture of their peers, which will significantly affect their attitudes towards them. The next question was asked to check if the students had experienced any contact with citizens from Ukraine before the start of the full-scale war. Most of them (57.1%) had not had any contact with Ukrainians, but, on the other hand, more than 16% had close relations, and almost 23% had some relations. This shows that most of them had no occasion to experience relationships with their geographically eastern neighbours. However, at the same time, it proves that Ukrainians, even in small towns like Olkusz, had already been present before. Therefore, not only after 24 February 2022 have youngsters had an opportunity to meet people from across the eastern border for the first time. (It should be underlined that less than a half of the students taking part in the research were from villages around the city of Olkusz.)

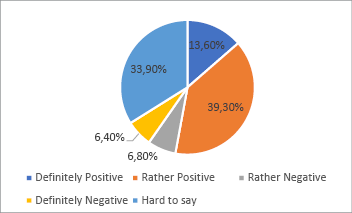

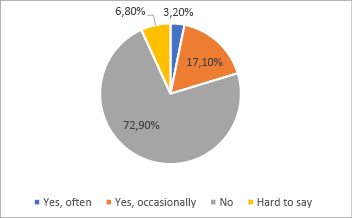

In intercultural education, contact between young people from different cultures outside of school is also important. However, as it can be seen from the research (Figure 4), the vast majority of the surveyed students – almost 73% – do not meet their friends from Ukraine outside of school, while more than 6% meet them occasionally, and only 3.2% meet them often in out-of-school contexts. A total of 17.1% answered that they had no opinion because they apparently had no contact with people from Ukraine. The lack of contact between students of these two nationalities outside of school may cause young people from Ukraine to close themselves only within their environment, which, in the long term, may have negative effects on the integration of immigrants into the Polish society.

On the other hand, youngsters were asked the question Did friends from Ukraine ask you for help at school or outside it? Most of the students answered No (73.9%), 17.1% Yes, and 8.9% responded Hard to say. This is one of the reasons why the youth from Ukraine are not looking for some relationship with their Polish peers at school. Schools, in cooperation with local non-governmental organisations and also with local authorities, should encourage contact between students to avoid the ‘ghettoisation’ of young people with refugee experience.

It is also worth noting that Polish students are not interested in the culture or history of people who came from Ukraine (Figure 5). Over 50% of young people are not interested in this topic at all. More than 35%, however, are. Almost 15% answered that it is difficult to say. Of course, one should not expect young people to be interested in the subject of refugees, but it is worth thinking in the long term about the interest of young people in the causes of the conflict in Ukraine, and also to get them familiarised with the culture of immigrants to Poland to help them better understand their peers. This result undoubtedly shows that intercultural education classes providing students with knowledge about minority cultures are needed. When students are afraid of the unknown, it will negatively affect their attitudes not only towards their peers from Ukraine, but it will also negatively affect their tolerance towards minorities in adult life.

Students from Olkusz were also asked if they would mind if their friends had girlfriends or boyfriends from Ukraine. The question was aimed at analysing their attitude towards peers from Ukraine. In both cases, over 80% of the respondents would not see it as a problem. At the same time, about 8% of the respondents would be against such a relationship. In both cases, 10% of students had no opinion on the subject. This answer is important in the context of the entire study because it shows that the Polish youth from Olkusz have no prejudices regarding their personal relations with young people with refugee experience.

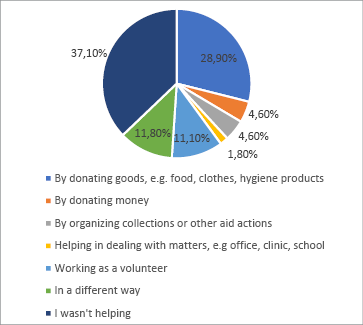

Another thought-provoking issue was the involvement of young people in helping refugees (Figure 6). Interestingly, more than 60% of the respondents provided help in various ways. This is a relatively large proportion when considering the age of the students. This involvement undoubtedly shows that the youth from Olkusz were ready to help during the refugee crisis, and this experience should therefore be used during classes.

Interestingly, by using a 1-to-5 scale (where 1 = poor, and 5 = very good), students assessed the knowledge of the Polish language by young people from Ukraine rather positively. More than 41% rated it at ‘3’ because it was sufficient, and more than 36% believed that their knowledge is good or very good. Only nearly 23% assessed it as poor or very poor. This shows that the language problem is not as serious as it could seem, and students do not experience a substantial communication barrier.

The next question was intended to gain some insight into the opinions of young people on the help provided by teachers to students from Ukraine. More than 42% of them assess it as sufficient, and over 31% have no opinion because they probably do not have peers from Ukraine in their form groups. It is also worth noting the 20% of the students think that too much help is being provided. This can cause jealousy, related not only to attention but also to the facilities that young people from Ukraine can use. The results regarding the help from the school for students from Ukraine are similar. More than a half of the respondents believe that the help is appropriate (54.3%) and, as in the previous question, almost 18% believe that the school helps students from Ukraine too much, while 23.3% have no opinion.

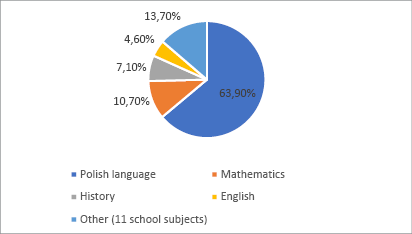

Young people were also asked with which subject their Ukrainian friends have the greatest problem at school (Figure 7). Here, more than 63% of the respondents clearly indicated that it is observed with the Polish language. Mathematics, which is often least liked by young people, was indicated by only over 10% of the respondents.

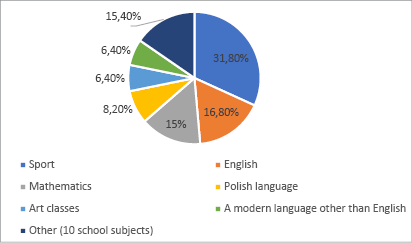

Very interesting, however, is the answer to the question with which subject they have the least problem (Figure 8). These are sports activities at school, which were indicated by over 30% of the respondents, while over 16% believe that young people from Ukraine have no problem with English, whereas 15% mentioned mathematics.

The final question was to show whether students think that separate form groups should be organised for Ukrainian classmates. Almost 30% answered positively. At the same time, over 40% believe that classes should be held together, while more than 27.3% have no opinion. This result shows that, still, a large number of students would see their peers from Ukraine in separate classes, which completely contradicts the ideal of intercultural education.

The large influx of Ukrainian refugees and their children has led to a more diverse student community in Polish schools. Intercultural learning helps these young people, many of whom are struggling with trauma, to adapt and get integrated into the school environment. It provides a framework for understanding their experiences and challenges, while helping Polish students empathise with and support their Ukrainian peers. The surveyed youth from schools in Olkusz are more sceptical about receiving immigrants than Poles in general. Unfortunately, this is sad news considering the general difficulty of the entire society in helping Ukraine. Interestingly, young people also believe that Poles do not have a positive attitude towards refugees, which may be due to the anti-Ukrainian narrative on the Internet. There is a lot of anti-Ukrainian content on social media such as TikTok or Facebook which targets Polish youngsters, posted mostly by ‘actors’ from other countries (Kamionka, 2022). As can be seen from research results, even if students are not willing to receive Ukrainian refugees, still they believe that Poles in general are willing to receive them, which is completely false when one looks at the official statistics. On the other hand, they believe that they have good relationships with their peers from Ukraine and would not mind their friends having a girlfriend or boyfriend from Ukraine (which shows deep acceptance for them). However, at the same time, they are not interested in the culture of their neighbours, even though they mostly helped immigrants during the start of the conflict in Ukraine. It can be a substantial achievement for schoolteachers to try to stimulate interest in Polish students in the culture of the refugees even at a basic level, while showing and using their own (or their family) experience in humanitarian aid. Polish students should not just passively support their Ukrainian peers, but they should be actively involved in providing support at school.

Thus, it is worth formulating a few recommendations. First of all, young people at school should be taught about the role of Poles and Poland in the humanitarian aid for Ukraine, which is valued all over the world. Poland and Poles have been taken as an example of grassroots humanitarian aid for war victims. Young people, however, build their opinions on online fake news, which may lead to social problems between Poles and immigrants from the East in the future. Meanwhile, it is not about individuals who are accepted and tolerated by young people, but primarily about the negative narrative created on the Internet. The Ministry of Education, school boards and schools themselves should prepare some additional classes showing Polish aid for the refugees (even drawing on the experience of the young people themselves), but also show young people the causes of the war and Russia’s totalitarian activities in the conflict. Intercultural education can challenge and dismantle stereotypes about Ukrainians and other minority groups. Polish students may have a limited understanding of Ukraine and its culture, and sometimes misconceptions can lead to discrimination or exclusion. By fostering intercultural dialogue, schools can create spaces where students from both backgrounds can share their perspectives and learn to see each other as individuals rather than through stereotypes. Moreover, it is worth creating an educational path based on showing the role of Ukrainians in the Polish history, not based on the neo-colonial subtext, but as a historical common past, which was the First Republic of Poland (the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth). It would also be worth introducing additional classes for the Ukrainian youth not only in the Polish language but also in the Polish literature, which will allow them to minimise problems with the educational material in the Polish language classes (including the Polish literature). Research clearly shows that young people do not have a negative attitude towards their peers from Ukraine, but additional measures must be introduced now to explain to young people why refugees are here, and that they are not a threat as in the stereotype of ‘taking jobs’ or ‘places at the doctor’s’ from Poles. If this knowledge is not instilled in the course of education, this may cause anti-Ukrainian sentiments in the future unless intercultural teaching is introduced in the education system. A large number of immigrants, as the surveyed youth themselves are aware, will stay in Poland, and end up starting a new life. Many Ukrainian children come from war zones, and they may have experienced trauma or loss. Schools can play a key role in supporting their mental health and well-being through a sensitive and culturally informed approach. Intercultural learning programmes can raise awareness among teachers and students about the psychological impact of displacement and war, and help create a supportive environment for the students to heal. Currently, there is enough time before problems can arise between the inhabitants of Poland in the future, as is often nowadays in some cases in Western Europe. School education should respond to these challenges.

References

Asghari, H. (2022). Teacher’s stories about teaching newly arrived refugee youths at a vocational upper secondary school in Sweden. Educare, 3, 160–185. https://doi.org/10.24834/educare.2022.3.7

Atanasoska, T., & Proyer, M. (2018). On the brink of education: Experiences of refugees beyond the age of compulsory education in Austria. European Educational Research Journal, 17(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904118760922

Berggren, J., Torpsten, A., & Berggren, U. J. (2021). Education is my passport: experiences of institutional obstacles among immigrant youth in the Swedish upper secondary educational system. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(3), 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1728239

Fallon, K. (2022, February 26). European nations throw open borders to Ukrainian refugees. News | Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/26/european-countries-open-borders-for-ukrainian-refugees

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.), New York, NY: Teachers College

Grudzińska, Z. (2022). Jaka powinna być polityka edukacyjna wobec uchodźców z Ukrainy? [What should be the educational policy towards refugees from Ukraine?], https://www.batory.org.pl/wpcontent/uploads/2022/05/Z.Grudzinska_Jaka.powinna.byc_.polityka.edukacyjna.wobec_.uchodzcow.z.Ukrainy.pdf

Ile dzieci i młodzieży z Ukrainy będzie się uczyć w polskich szkołach od września? Czarnek podał nową liczbę - Głos Nauczycielski. [How many children and teenagers from Ukraine will study in Polish schools from September? Czarnek announced a new number ](2022, June 10). Głos Nauczycielski. https://glos.pl/ilu-uczniow-z-ukrainy-bedzie-sie-uczyc-w-polskich-szkolach-od-wrzesnia-czarnek-podal-nowa-liczbe

Kamionka, M. (2022). Wpływ wojny na Ukrainie na trendy portalu społecznościowego TikTok [The impact of the war in Ukraine on the trends of the social networking site TikTok]. Youth in Central and Eastern Europe, 9(14), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.24917/ycee.9636

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159-165.

Levchuk, P., Bihunova, S., & Vorobiova, I. (2022). An Evaluation of the Power of Polish Language by Ukrainian Modern Language Students. Cognitive Studies | Études Cognitives, 22. https://doi.org/10.11649/cs.2622

Nikitorowicz, J. (2005). Pogranicze, tożsamość, edukacja międzykulturowa. Obywatele Ukrainy w Polsce – aktualne dane migracyjne - Urząd do Spraw Cudzoziemców [Borderland, identity, intercultural education. Citizens of Ukraine in Poland - current migration data - Office for Foreigners] - Portal Gov.pl. (2023, February 24). Urząd Do Spraw Cudzoziemców. https://www.gov.pl/web/udsc/obywatele-ukrainy-w-polsce--aktualne-dane-migracyjne

Prokopenko, O., & Kryvoruchko, L. (2017). Podobieństwa i różnice kulturowe jako podstawa rozwoju wzajemnie korzystnych stosunków między Polską a Ukrainą. Perspektywy Kultury [Cultural similarities and differences as the basis for the development of mutually beneficial relations between Poland and Ukraine. Cultural Perspectives], 17(2), 7-16. https://czasopisma.ignatianum.edu.pl/pk/article/view/1849

Sewastianowicz, M. (2023). Oświadczenie rodzica zwalnia ukraińskiego ucznia z obowiązku szkolnego, a wymogu rejestracji nie ma [The parent’s declaration exempts the Ukrainian student from compulsory schooling, and there is no registration requirement]. Prawo.pl. https://www.prawo.pl/oswiata/obowiazek-szkolny-a-zdalna-nauka-w-ukrainie,514199.html

Sharif, H. (2016). Ungdomars beskrivningar av mötet med introduktionsutbildningen för nyanlända. – Inte på riktigt, men jätteviktigt för oss [Young People and the Introductory Programme for Newly Arrived – Not for Real, but Important to Us] (pp. 65–91). In P. Lahdenperä & E. Sundgren (Eds.), Skolans möte med nyanlända [School Approaches to Immigrant Youth] (pp.92–110). Liber.

Soylu, A., Kaysılı, A., & Sever, M. (2020). Refugee Children and Adaptation to School: An Analysis through Cultural Responsivities of the Teachers. Eğitim Ve Bilim. https://doi.org/10.15390/eb.2020.8274

Theus, J. ( 2024, April 4). Coś się zmienia: młode kobiety tracą serce do ukraińskiej obecności w Polsce [Something is changing: young women are losing heart towards the Ukrainian presence in Poland] [SONDAŻ IPSOS], https://oko.press/ukraincy-w-polsce-sondaz-ipsos.

Tilles, D. (2021, August 26). Most Poles opposed to accepting refugees and half want border wall: poll. Notes From Poland. https://notesfrompoland.com/2021/08/26/most-poles-opposed-to-accepting-refugees-and-half-want-border-wall-poll

Ukraine Refugee Pulse, (2023, September 12): Social Progress Imperative. https://www.socialprogress.org/ukraine-refugee-pulse/

W Polsce ubyło zwolenników przyjmowania uchodźców z Ukrainy [In Poland, there have been fewer supporters of accepting refugees from Ukraine] (2023, May 10). www.pulshr.pl. https://www.pulshr.pl/po-godzinach/w-polsce-ubylo-zwolennikow-przyjmowania-uchodzcow-z-ukrainy,97376.html

Zymnin, A., Wierzchowski, M., & Sielewicz, M. (2023). From Poland to Germany. New Trends in Ukrainian Refugee Migration, Warsaw: University of Warsaw.

1 From 24 Feb. 2022 to 25 Oct. 2023, over 16.66 million people from Ukraine crossed the Polish border. During that time, 14.84 million people crossed the border on their way back. This shows the scale of the refugee crisis after the start of full-scale war.

2 The powiat is the second-level unit of local government and administration in Poland, equivalent to a county, district or prefecture in other countries. The term ‘powiat’ is most often translated into English as ‘county’ or ‘district’ (sometimes, ‘poviat’).