Acta humanitarica academiae Saulensis eISSN 2783-6789

2025, vol. 32, pp. 35–55 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/AHAS.2025.32.3

Aspects Regarding the Voting System in Romania in the Modern Era (19th Century)

Cristina Gudin

University of Bucharest, Faculty of History, Romania

cristinagudin@yahoo.fr

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-2912-013X

https://ror.org/02x2v6p15

Abstract. The study aims to present the evolution of the voting system in Romania during the 19th century, highlighting the social and political context that led to the transition from one stage to the next. In the modern era, in Romania, the participation in the political life of the inhabitants was conditioned by the economic situation, citizenship, gender, age, and legal record.

Thus, the right to vote was granted only to men who had reached the age of 21 and who were engaged in honorable and profitable economic activities. The possession of citizenship by birth or naturalization was added, as well as the condition of not having seriously violated the laws of the country.

Although the electoral body was small and the rural population was poorly politically represented, even though it was the most numerous, exceeding 80% of the total population of Romania, it can be stated that, in general, there is a tendency to increase the number of voters. This was achieved in several moments, by reducing the electoral census, but also by expanding the number of professions whose practice ensured voting attendance without fulfilling the economic conditions.

These exceptions were based on the fact that the practitioners of the respective professions (generally freelancers) were sufficiently educated and politically mature to be able to make a conscious and informed choice without falling victim to manipulation.

These, as well as other aspects (such as women getting the right to vote), will be developed in the study.

Keywords: Romanian Principalities, voting system, evolution, electoral college, 19th century

Rumunijos balsavimo sistemos aspektai moderniojoje eroje (XIX amžius)

Anotacija. Tyrimo tikslas – pristatyti balsavimo sistemos raidą Rumunijoje XIX amžiuje, pabrėžiant socialinį ir politinį kontekstą, kuris lėmė perėjimą iš vieno etapo į kitą. Šiuolaikinėje epochoje Rumunijoje gyventojų dalyvavimą politiniame gyvenime sąlygojo ekonominė padėtis, pilietybė, lytis, amžius ir teisinė praeitis. Taigi, teisė balsuoti buvo suteikta tik vyrams, sulaukusiems 21 metų ir užsiimantiems garbinga bei pelninga ekonomine veikla. Buvo pridėta pilietybės turėjimas gimimo ar natūralizacijos būdu, taip pat sąlyga, kad asmuo nebūtų rimtai pažeidęs šalies įstatymų. Nors kaimo gyventojai buvo menkai politiškai atstovaujami, bet jie sudarė daugiau nei 80 % visų Rumunijos gyventojų, taigi galima teigti, kad apskritai pastebima tendencija didinti rinkėjų skaičių. Tai buvo pasiekta sumažinant rinkėjų surašymą, taip pat plečiant profesijų, kurių praktika užtikrino dalyvavimą balsavime, neįvykdant ekonominių sąlygų, skaičių. Šios išimtys buvo pagrįstos tuo, kad atitinkamų profesijų specialistai (dažniausiai laisvai samdomi darbuotojai) buvo pakankamai išsilavinę ir politiškai subrendę, kad galėtų priimti sąmoningą ir pagrįstą sprendimą netapdami manipuliacijų aukomis. Šie ir kiti aspektai (pvz., moterų balsavimo teisės įgijimas) bus nagrinėjami tyrime.

Pagrindinės sąvokos: Rumunijos kunigaikštystės, balsavimo sistema, raida, rinkimų kolegija, XIX amžius.

Gauta: 2024-10-22. Priimta: 2025-04-23.

Received: 22/10/2024. Accepted: 23/04/2025.

Copyright © 2025 Cristina Gudin. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction: features of the 19th century and the evolution of the concept of freedom

This material aims to present the evolution of the voting system in Romania during the 19th century, highlighting the social and political context that led to the transition from one stage to the next. This approach is significant because the mentioned period was marked by transformations that substantially changed society, mentality, and all fields of activity, including the political one.

The emergence of nation states, the establishment of political parties, the imposition of principles such as multi-partyism, alternation in government, the separation of powers in the state, the transfer of power from the hands of a person or a small group to those of the people who held it based on their sovereignty, all these became realities in the 19th century. The diversification of civil rights, as well as the expansion of access to them, were both successes of modernity.

As we anticipated, this research focuses not only on the type of voting in Romania, but also on the moments when changes occurred regarding the participation of the inhabitants in political life, in other words, in the decision-making in the state.

The change in the electoral system also required a clearer definition of the concept of citizen and the conditions that made it possible to include foreigners among the inhabitants with civil and political rights, the situations that led to the loss of this quality and the expansion of access to them, were also successes of modernity (Voinea, Bulzan, 2003, p. 17).

To begin with, we consider it necessary to provide some clarification regarding how the concept of freedom has evolved.

In this sense, we recall that the idea of political freedom that consisted in the collective and direct exercise of several parts of sovereignty is due to the classical civilization of Greece. More specifically, ancient citizens deliberated in the public square about war and peace or about alliances with foreigners. In other words, they had legislative, judicial, and financial powers.

This freedom, limited to a minority, that of citizens, was not duplicated by personal freedom, private actions being subject to the authority of the social body in terms of profession, opinions, or religion (Constant, 1996, p. 10).

In the 19th century, instead, freedom was mostly civil and personal, so that individuals were independent in private life, but their sovereignty was restricted. Thus, the power held by the people is exercised indirectly, through representatives invested with authority, according to the principle of the social contract, theorized by Jean-Jaques Rousseau in the work with the same name.

Increasing the degree of freedom, translated into citizen involvement in politics, was conditioned, among other things, by the emergence and consolidation of national consciousness, but also by the design of a new ideal regarding the citizen. This had to be: literate, educated (including patriotic and civic education), politically responsible, and economically independent (Ștefănescu-Galați, 1924, p. 31). Its appearance was favored by the intensification of secularization, which implied the involvement of the state in all areas of interest and the decrease of the Church’s authority (Isar, 2010, pp. 166-167).

Research methodology for the study of the voting system in Romania in the 19th century

In our investigation, we applied qualitative and quantitative research principles. Qualitative research collects and analyzes data from various sources to create a comprehensive picture of the subject under study. The information that formed the basis of this research comes from official documents (the Constitution of 1866, the Paris Convention of 1858, the Paris Peace Treaty of 1856, the Organic Regulations, the Developing Statute of the Paris Convention of 1864, etc.). In addition, the main works that dealt with the evolution of voting among Romanians in the 19th century, as well as statistical data, were taken into account.

The objective of the research was to present the stages in the evolution of the voting system in the Romanian Principalities (called Romania since 1866).

To better understand the importance of the changes that occurred throughout the 19th century regarding the voting system, we considered it necessary to refer to the political and military context not only in the Romanian space, but also in South-Eastern Europe.

In this sense, there is no shortage of references to the involvement of the Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Great European Powers in the Romanian Principalities.

The methodology we used in investigations on the evolution of the voting system varied depending on the specific research question, objectives, and data collection techniques. We particularly used the following research methods:

• Historical contextualization was essential in analyzing the voting system. We explored the political, social, and military events that shaped the voting system.

• Content analysis involved systematically coding and categorizing the content of the official documents and statistical data to identify trends related to participation in political life.

• Close reading and textual analysis involved a detailed and careful analysis of the information regarding the voting system.

• Comparative analysis of the information allowed us to reconstruct the evolution of the population’s degree of participation in political life. It also made it possible to notice the differences that exist from one historical stage to another.

Triangulation, which involves confirming findings through different sources or methods, ensured that interpretations were well-founded and not solely reliant on a single source.

Research question 1: How did the degree of freedom, reflected in the participation of residents in political life, evolve in 19th-century Romanian society?

Research question 2: How did the evolution of the international context in the area influence the internal situation in Romania throughout the 19th century?

Hypothesis 1: The process by which the level of freedom was achieved was complex and tortuous, but, in general, it can be said that the trend was towards the consolidation of democracy.

Hypothesis 2: The dependence of the Romanian Principalities on the Russian Empire (until 1856) and the Ottoman Empire (until 1877) influenced internal political realities. However, as a result of the increasingly strong Western influence, the Romanians acted towards achieving political independence and consolidating autonomy.

The political status of the Romanian Principalities in the 19th century

Before starting the presentation of the announced subject, we consider it necessary to make a few clarifications about the legal status of the Romanian Principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia).

Until 1821, the Romanians did not have the right to choose their leaders.

This was the consequence of the reaction of the Turks to the attempts of the Romanians to ally with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire. The Romanians were under Turkish rule, which meant that they had no right to conduct their foreign policy. In exchange for political-military protection, they had economic and financial obligations to the Ottoman Empire. However, they enjoyed autonomy, having the right to legislate at the local level.

During the Phanariot regime (1711/1716-1821), the dependence on the suzerain power increased, and the rulers were appointed directly by it, independently of the will of the Romanians. Moreover, if initially the rulers came from families of Romanian origin, after 1770, the Greeks were preferred, proof of the consolidation of Turkish authority.

The situation improved after the revolution of 1821, when, dissatisfied with the Greeks’ attempt to gain independence from the Ottoman Empire, they lost the support of the Turks. For the Romanian Principalities, this meant regaining the right to have Romanian rulers.

The Ottoman Empire’s suzerainty over the Principalities ceased in 1877 when, by participating in the Russian-Turkish war of the same year, Romania obtained its political independence.

The situation of the Principalities was complicated because, since 1774, the Romanians were also under the protectorate of the Russian Empire. For the latter, this was an opportunity to repeatedly limit the autonomy of the Romanian Principalities, because the Russian Empire’s protection of the interests of the Romanians concerning the Turks was only a pretext for it to pursue its expansionist interests in the area.

The Russian protectorate over the Romanians ended after the defeat suffered in the Crimean War (1853-1856), but during 1831/1832-1856 the Russian control over the Principalities was intensified by the application of the Organic Regulations which were instruments through which the Russian Empire removed the Principalities from the influence of Turks.

After the Paris Peace Congress of 1856, the Romanians came under the collective guarantee of the Great European Powers.

The Romanian Principalities existed as distinct political entities until 1859, when they united and formed a national and modern state, named the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (between 1859 and1866) and Romania since 1866.

In light of the above information, we can say that the degree of freedom enjoyed by the Romanians depended on their powerful neighbors and/or the rest of the European powers and varied according to the balance of forces between them.

Thus, during the Russian protectorate, the autonomy of the Romanian Principalities was limited. This is proven by the episodes of military occupation in 1821-1826, 1828-1834, 1848-1851, 1853-1865. On the other hand, since the second half of the 19th century, thanks to the European collective guarantee, the autonomy of the Principalities has increased, and with it the degree of freedom.

The principle of separation of powers and participation in political life according to the Organic Regulations

The Organic Regulations marked the beginning of the opening to the consultation of the inhabitants regarding important matters, such as the election of the ruler or the laws that had to be adopted.

The Organic Regulations were introduced in 1831-1832 at the initiative of the Russian Empire and were almost identical in terms of content. Through them, the replacement of the Eastern organizational model with one of Western inspiration was achieved (Djuvara, 1995, p. 29).

These Regulations provided for an ordinary public assembly with legislative powers in each principality. To fully illustrate the principle of separation of powers in the state, we mention that the ruler was the exponent of the executive power, while the judicial power was represented by several courts, the highest being the High Divan. The head of state had powers in all spheres of power, having the right to initiate and approve laws, to lead the army, and the executive power (in the sense in which he appointed the seven ministers who made up the Administrative Council). The Court decisions were also issued in the ruler’s name (Oțetea, 1957, p. 394).

Although the name of the Ordinary Assembly (which had legislative powers) referred to the people, in reality, its members came only from among the aristocracy, which represented less than 1% of the total population.

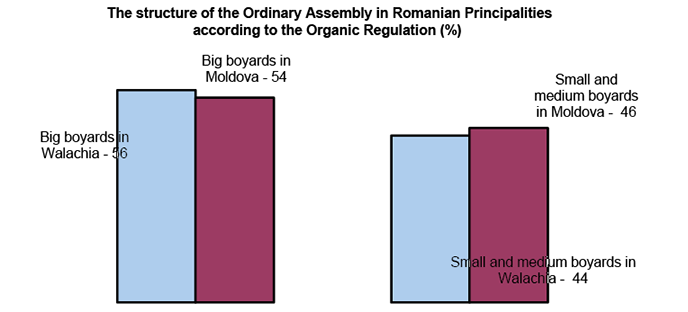

Ordinary Assemblies were convened annually, were led by metropolitans, and consisted of 35 members in Moldavia and 42 members in Wallachia. Among them, most belonged to the high aristocracy (54-56%), the rest coming from the ranks of the small and middle boyars. It can be said that a social and economic minority decided for all the inhabitants.

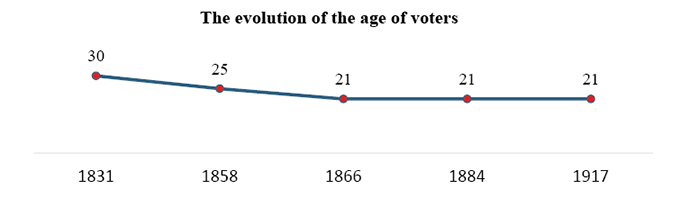

The conditions that the members of the Ordinary Assembly had to fulfill were: citizenship, minimum age of 30 years, belonging to the nobility, and being male.

The term of office was five years, and, apart from the metropolitan and the bishops who were ex officio members, the rest of the aristocrats in the Assembly were appointed after obtaining a majority of the votes cast by the boyars who had reached the age of 30. Consequently, the electoral body was very small, in Moldavia, amounting to only 303 voters (which meant 0.3% of the inhabitants of the country), and in Wallachia, to 439 voters.

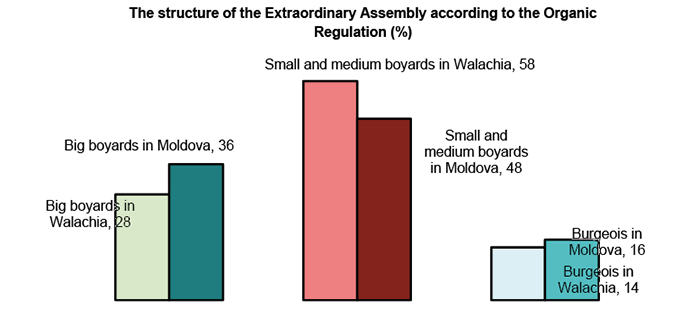

Another institution, the Extraordinary Assembly, was involved in the election of the head of state, and it had to be convened at the end of each reign. This Assembly had a wider degree of representation, being made up of aristocrats and the bourgeois. Composed of 190 members in Wallachia and 132 in Moldavia, the structure of the Extraordinary Assembly was dominated by the more modest ranks of the aristocracy. Namely, in Wallachia, 58% were small and medium boyars, 28% large boyars, and 14% bourgeois, and in Moldavia, 48% were small and medium boyars, 36% large boyars, and 16% bourgeois. The members of the Extraordinary Assembly were at least 30 years old, they were Romanians by birth, owners, and they did not have to be under the protection of any other country (The Organic Regulation, 1944, p. 1). The deputies were losing their seats after three consecutive absences (Preda, 2011, p. 38).

The elections were held by lottery on different dates for each category of members at the level of each county. The voters came only from the social category of the members to be elected.

The great boyars were chosen by drawing lots, and the winners were established in descending order of votes until reaching the number of votes provided for this category in the Organic Regulations.

Small and medium boyars were appointed through elections held at the county level, with each county having the right to elect two deputies, and the number of burgeois who reached the Extraordinary Assembly depended on how populated and economically prosperous each town was. For these reasons, the number of deputies representing tradesmen’s and merchants’ associations varied. In this sense, we recall the distribution from Wallachia, namely: 9 deputies from Bucharest, 3 from Craiova, 2 each from Ploiești, Roșiorii de Vede and Râmnicu Vâlcea, one each from Focșani, Buzău, Târgoviște, Pitești, Câmpul Lung, Slatina, Târgu Jiu, Caracal and Cerneți (The Organic Regulation, 1944, pp. 3-4).

All elections took place in the presence of electoral commissions composed of a president and a secretary who not only organized and supervised the electoral process, but also recorded the result of the vote and transmitted it to the head of state or the substitutes who provided the leadership of the country during the period when the throne was vacant.

That’s what happened in 1842, when the elections were organized by the substitutes Iordache Filipescu, Teodor Văcărescu, and Mihail Cornescu. This was the only time when the Extraordinary Assembly was convened for the election of the ruler. In the rest of the time, the head of state was imposed without consulting the Romanians, so the ruler was imposed by the Russian Empire and formally confirmed by the Ottoman Empire.

The conditions that the head of state had to fulfill were: minimum age of 40, belonging to the aristocracy for at least two generations, and Romanian citizenship. Furthermore, although it was not mentioned in the Organic Regulations, the rulers had to be favorable to the Russian Empire.

The duration of the reign varied over time, as follows: between 1829 and1849, the reign was for life, between 1849 and1856, the duration was reduced to 7 years, and after 1856, life rule was restored. However, only one ruler had the end of his reign coincide with the end of his life, and that was Charles I.

The vote took place on December 20, 1842, in the presence of 179 of the 190 members of the Extraordinary Assembly, voters not being allowed to leave the building where the elections were held until the end of the electoral process. The 21 candidates were chosen by using black and white balls that were handed to each voter by the leader of the church, who was the president of the electoral commission. Gheorghe Bibescu prevailed by obtaining 69% of the votes (Bolintineanu, 1869, pp. 62-65).

Romanian Principalities between 1848 and1856

The revolution of 1848 represents an illustrative moment for the concern of expanding the rights and freedoms of citizens, among them the right to participate in political life. In this sense, we remember that in the reform program of the Wallachian revolutionaries, entitled the Proclamation from Islaz, the rise of number of voters increased. For this reason, it was envisaged that all Romanian men by birth or naturalization would participate in the elections, and the right to be elected would depend only on the capacity, conduct, virtues and public trust of those willing to get involved in the administration of public affairs (Berindei, 1974, p. 87).

In addition to all these things, representatives of all social categories had to be included in the Ordinary Assembly, and it was considered appropriate to draft a constitution based on the principles of equality, fraternity, and freedom.

Similar provisions existed in the program of the revolutionaries from the Principality of Moldavia, the Proclamation Petition, proof that they shared the same liberal principles, such as: the election of the ruler from the whole society, the abolition of censorship, occupying positions based on professional competence, the responsibility of ministers and clerks, the taxation of all residents, the abolition of privileges (Stan, 1992, pp. 237-240).

The Revolution of 1848 was also the moment when the Organic Regulations, considered an amalgam of heterogeneous and contradictory provisions, with provisions of an ambiguous meaning, especially to leave a free way to abuses (Berindei, 1974, p. 98), were contested, as happened in Wallachia. Then the Organic Regulation was burned in the public square, with this gesture also denouncing the dependence on the Russian Empire.

Although liberal, the principles formulated in 1848 did not materialize because the revolutions were defeated by the military intervention of the Russians and the Turks, followed by the occupation of the Romanian Principalities by these two armies until 1851.

During the military occupation, the autonomy of the Romanian territories was significantly reduced based on the Convention concluded in 1849 at Balta Liman by the two empires. As I have already mentioned, for the audacity to have challenged the authority of the Russian Empire, the Romanians were punished by reducing the duration of the reign to 7 years, eliminating the involvement of the Romanians in the election of their leaders, abolishing the Ordinary and Extraordinary Assemblies and replacing them with Ad-hoc Assemblies. These ones only had financial attributions and their members came only from among the great boyars, which meant that their degree of representation was very low (Isar, 2006, pp. 205-206).

It can be concluded that the situation of the Romanian Principalities worsened after the defeat of the revolutions of 1848 and remained so under the conditions in which the Crimean War (1853-1856) meant the occupation of these territories by the Russian, Turkish, and Austrian armies.

The situation after the Crimean War and the union of the Romanian Principalities

The end of the war, in 1856, allowed not only the return to normality due to the diminishing influence of the Russian Empire in the area, but also the return of the revolutionaries from exile or the obtaining by the Romanian Principalities of additional security guarantees. With the Paris Peace Congress, the European Great Powers accepted the union of Moldavia with Wallachia, after a prior consultation of the Romanians.

As a consequence, the Ottoman Empire, as a suzerain power, was tasked with organizing elections to appoint members of the Ad-hoc Assemblies. The Assemblies were to function in Iassy and Bucharest and had to represent the interests of all classes of society as accurately as possible. At the same time, they were to express the wishes of the population regarding the definitive organization of the Principalities (The Paris Peace Treaty, p. 1). In other words, their only responsibility consisted of formulating an official answer regarding the union of the two Principalities.

The holding of the elections was preceded not only by the emergence of some union committees, but also by an intensive press campaign in which newspapers like The Romanian, The National, and The Star of the Danube were involved. The former leaders of the 1848 revolutions stood out in the making of the propaganda. They all published articles explaining the importance of achieving union.

The elections for the Ad-hoc Assemblies assumed compliance with the rules established by the Turks. Thus, the voters were divided into 5 colleges corresponding to different social categories, namely: the first college consisted of the leader of the church, bishops, abbots and administrators of monasteries; the second college included all the boyars who had turned 30 years old, were citizens and owned land of at least 450.000 m², and the third college included those who owned land of at least 150.000 m².

The novelty consisted in the consultation for the first time of the peasants participating in the elections as members of the fourth college.

The fifth college was for the inhabitants of the cities over 30 years of age, citizens without the protection of any other country, and owners of a house (worth at least 20,000 piastres in Bucharest or 8,000 piastres in the rest of the cities). Also in the fifth college, there were merchants or craftsmen (three from each guild) and freelancers (teachers, engineers, architects, doctors, artists) who had lived in the respective city for at least three years.

Although the participation of the peasants in the elections deserves to be remembered, it is necessary to specify that the Ottoman Empire established rules that disadvantaged the followers of the union. Among these rules, we mention that the peasants, although the majority in society, elected the smallest number of deputies, instead the first and second colleges, which represented a small number of people, sent the most deputies to the Ad-hoc Assemblies. In addition, only men aged at least 30 could vote, so young people could not participate in the vote, as it was known that young people were unionists (Isar, 2006, pp. 230-232).

Fixed by the Ottoman Empire, the electoral rules were applied by the substitutes of rulers who temporarily administrated the Romanian Principalities. Appointed in 1856, Alexandru D. Ghica (in Wallachia) and Teodor Balș, and then Nicolae Vogoride (in Moldavia), took different positions regarding the union. Ghica supported it, which led to the winning the elections by the unionist deputies, while Balș and Vogoride were against it. Nicolae Vogoride falsified the electoral lists and the election results in favor of the anti-unionists. His gesture, however, became public and triggered protest actions, which is why the rerun of the elections was required. This time, held under the stricter supervision of representatives of the European Powers, the elections were favorable to the patriots.

Thus, the decision of the union could be included in the resolutions adopted in October 1857 in Bucharest and Iassy. For their part, the great European Powers gathered at the Paris Conference in 1858 made a convention that mentioned the union of the Romanian Principalities.

Although the political success of the Romanians is indisputable, it must be emphasized that the union was not achieved in the way they wanted, because instead of a total union1, a partial union was preferred. This meant: one leader for each principality2, distinct institutions for each principality (legislative assembly, government, army, etc.).

However, the union is reflected in the name of the state (the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia), but also the existence of two common institutions (the Central Commission and the High Court of Justice and Cassation).

Though the Paris Convention did not fully reflect the desire of the Romanians, it also included liberal provisions, such as the abolition of privileges, the imposition on all residents to pay taxes, the abolition of censorship, and the guarantee of property or equality in obtaining public positions.

Less praiseworthy was the electoral law, which supplemented the Convention and detailed the census voting system. According to it, residents exercised their right to vote to appoint deputies in the Elective Assemblies that were part of the legislative power (along with the rulers and the Central Commission). The term of office for assembly members was 7 years (Isar, 2006, pp. 238-239).

The voters were divided into three colleges. The first college was of the primary voters (who voted indirectly, that is, through delegates), and here all the people with an annual land income of at least 100 galbeni3 were included. The second college involved the direct expression of the vote and included all those who had an annual land capital of at least 1,000 galbeni. The third college consisted of the inhabitants of cities with a land, industrial, or commercial capital of at least 6,000 galbeni and who voted directly. The minimum age for all voters, regardless of college, was 25.

In other words, the voting age was reduced from 30 to 25, and city inhabitants voted directly, while rural residents voted through representatives.

We underline the fact that the wealth was maintained under the conditions that conferred the right to vote. As a result, only the rich and very rich residents could vote, the majority of the population being eliminated from participation in political life.

Eligible were all male persons who had Romanian citizenship, an annual income of at least 400 galbeni, and who had reached the age of 30.

Voters with indirect voting from the rural areas appointed three delegates from each plasă (plasa being a subdivision of the county). All the delegates from a county chose a delegate in the elective or legislative Assembly. Voters with direct vote from rural areas elected two deputies per county, and townspeople directly voted for several deputies, as before, according to the economic importance of the town. As a result, the inhabitants of Bucharest and Iassy sent 3 deputies to the Assembly, Craiova, Ploiești, Brăila, Galați, and Ismail 2 each, and the other county residences one deputy each.

Regardless of gender, age, and wealth, those under foreign jurisdiction could not vote; the same treatment also applied to unrehabilitated bankrupts or those who had been sentenced to prison.

According to the electoral law of 1858, the level of participation in political life was one voter per 1,100-1,200 inhabitants. More precisely, out of almost 4 million inhabitants, only 3,800 voted (Isar, 2006, p. 241; Iacob, Iacob, 1995, p. 62).

The first important task of the Elective Assemblies consisted of electing the leaders of the two Principalities.

The elections took place in 1859 and led to the appointment on January 5 and 24 of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as monarch of both Romanian Principalities.

The Romanian Principalities and the voting system during the reign of Alexandru Ioan Cuza (1859-1866)

The election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza was possible because in the text of the Convention, it was not explicitly mentioned that the leader of Moldavia, respectively, Wallachia, must be a different person. The double election was accepted by the Great Powers only during the reign of Cuza, the duration of the reign being, according to the Convention, for life.

The solution to which the Romanians resorted was not original, even in the Habsburg Empire, the title of emperor of Austria and king of Hungary being simultaneously held by the same person.

It should be emphasized that, after the international confirmation of the quality of the monarch of both Romanian Principalities, Al.I. Cuza started an extensive reform process, which made possible, among other things, institutional unification. In this regard, we mention that on January 24, 1862, the Legislative Assemblies of Iassy and Bucharest were repealed and a single Parliament was established.

Changes to voting conditions took place after May 2, 1864, when the Developing Statute of the Convention of Paris and a new electoral law were adopted. The changes were the consequence of the coup d’état by which Al.I. Cuza dissolved the Elective Assembly because of its opposition to rural reform, by which land was given to the peasants. The Developing Statute of the Convention of Paris was validated by plebiscite and confirmed the increase in the power of the leader (Isar, 2006, p. 267)4, giving him more legislative authority.

This happened through the establishment of the Senate as a second legislative chamber in addition to the Elective Assembly. The members of the Senate were 50% elected by the voting population and 50% appointed by the ruler (Developing status of the Paris Convention, p. 207). At the same time, the head of state also appointed the president of the Elective Assembly.

As the ruler was expected to make appointments from among those who supported him, it was rightly stated that he controlled the legislative power.

As we have already mentioned, with the coup d’état, the electoral law was also changed in order to increase the number of voters. Broadening participation in political life was necessary in conditions where the ruler, losing the support of the political class, nevertheless wanted to legitimize his reforms, resorting to the support of the population for this.

It, therefore, expands the number of voters by massively reducing the wealth requirement. The two categories of voters, direct and primary (indirect), were kept.

Direct voters were all literate Romanian citizens over the age of 25 who paid a tax of at least 4 galbeni to the state (corresponding to an annual income of 100 galbeni). To them were added some professional categories (priests, teachers, civil servants, and freelancers) who were exempted from the electoral census.

Primary voters, also appointed indirectly because they voted through representatives (50 primary voters chose a delegate), had to pay a tax of 48 lei5 in villages and between 80-110 lei in cities.

Proceeding in this way, the number of voters increased to approximately 570,000, the ratio being one voter for every 8-9 inhabitants. The new electoral law ensured the population’s access to political life in an unprecedented proportion until then.

As for the eligible persons, they had to be at least 30 years old and pay an annual tax of 200 galbeni, or belong to the professional categories that did not pay the electoral census.

It follows from this that the political power was still held by the rich or by those who had reached, through their professions, a high cultural level.

The aforementioned electoral provisions were only applied for a few years, new changes appearing with the abdication on February 11, 1866, of Al.I. Cuza and with the election of another ruler, in the person of Charles I of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

The voting system during the reign of Charles I (1866-1914)

Before referring to the voting situation during the reign of Charles I, we recall that before he had officially accepted the invitation of the Romanians to become their leader, a plebiscite was organized in April 1866 through which the population was consulted in relation to bringing a foreign prince into the country. The result of the plebiscite6 confirmed the desire of the Romanians to be ruled by a foreign prince, hoping that through this Romania (the new name of the United Principalities of Moldovia and Walachia) would acquire the protection of the country where the monarch came from, it would be able to promote its interests more successfully at the international level and that it would increase its prestige (Hitchins, 1996, p. 29).

Since the beginning of the reign of Charles I, the first Constitution of Romania was adopted in 1866, which consolidated the social framework so that each individual was free within freely agreed limitations, this being the premise of classical liberalism that allowed the creation of modern democratic societies (Liiceanu, 2017, p. 77).

The Constitution, work of the Romanian nation (Tătărescu, 2004, p. 31), was notable for its liberalism, a fact also due, among others, to its inspiration from the 1831 Constitution of Belgium, considered the most democratic in Europe at that time (Filitti, 1934, p. 26).

The Constitution of 1866 changed the form of government from an elective monarchy to a hereditary constitutional monarchy, detailed the rights and freedoms of citizens, as well as the principle of separation of powers in the state. In connection with this principle, we will stop on the articles regarding the legislative power in order that the formation of the legislative Assemblies involves the vote of the population.

So, the legislative power was represented by the Parliament, composed of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies.

The voters were divided into colleges, as follows: for the Senate, there were two colleges whose members voted directly and secretly, each college electing one senator from each county. Only people with a good and very good economic situation entered these colleges, the first college being reserved for those with land income of at least 300 galbeni, and the second for those with land income of 100-300 galbeni.

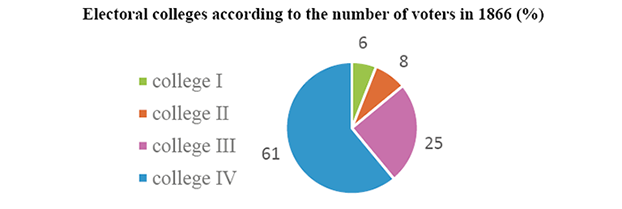

For the election of deputies, the voters were divided into four colleges, namely: the first college included those with land incomes of at least 300 galbeni, the second those with land incomes of 100-300 galbeni, the third college included the townspeople who paid to the state a tax of 80 lei, and the fourth college was reserved for all those who paid a tax to the state, no matter how small, and who did not fit into the rest of the colleges.

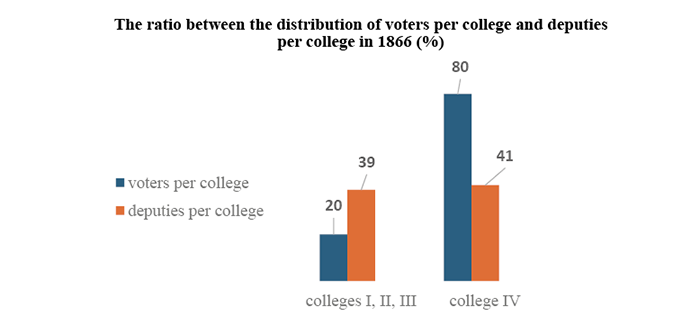

The exemptions from the electoral census were kept for freelancers, teachers, reserve officers, and former clerks. Also, the voters continued to be divided into direct voters (as were those in the first three colleges for the Assembly of Deputies) and indirect voters (each 50 voters with the right to vote appointed a representative, and all representatives in a county elected a deputy).

The articles by which the first two colleges voted for one deputy from each county also continued to apply, while the third college appointed a predetermined number of deputies calculated according to the economic importance and the number of its inhabitants. The capital of the country, Bucharest, elected 6 deputies each, Iassy – 4, Craiova, Galați, Ploiești, Focșani, Bârlad and Botoșani 3 each, Pitești, Bacău, Brăila, Roman, Turnu Severin 2 each, and the other cities elected only one deputy each (Constitution of 1866, p. 3).

According to the electoral law that accompanied the Constitution, all men, citizens by birth or naturalization (in this sense, the seventh article of the Constitution mentioned that Christian foreigners could become Romanian citizens), all men participated in political life as voters. They had to achieve the electoral census conditions or be among the exceptions.

We note that the age at which a person could exercise the right to vote decreased from 25 to 21 years.

However, the number of voters did not increase; on the contrary, it decreased 10 times compared to the previous period, the increase in the electoral census contributing to this, which led to the ratio of one voter to 83 inhabitants.

More precisely, of the approximately 4 million inhabitants of the country, 3,388 formed the first college, 4,814 – the second college, 15,382 – the third college, and 37,070 – the fourth college. In other words, the voters from the first college represented 6%, those from the second college – 8%, in the third college there were 25% of the total number of voters which amounted to 60,654 people, and in the fourth college there were 61% of the residents with right to participate in political life.

Most parliamentarians were elected by the big landowners who composed the first two colleges, although they represented the least numerous social category.

Instead, although the majority of voters were in the fourth college, this college sent the smallest number of parliamentarians, because they voted indirectly. More specifically, of the 157 deputies, 124 (80%) were elected by the residents belonging to the first three colleges, while only 33 deputies, or 20%, came from the fourth college (Isar, 2006, p. 296).

The quality of voters was denied to Romanians under foreign protection, servants, beggars, bankrupts, criminals, and owners of casinos and houses of prostitution.

For eligible persons, the Constitution contained different conditions for each legislative chamber.

Thus, deputies had to be citizens who lived in Romania, enjoyed civil and political rights, and be at least 25 years old. Senators had to, apart from the conditions regarding residence, citizenship, and the preservation of civil and political rights, be at least 40 years old and have an income of at least 800 galbeni (because, unlike deputies, they were not paid).

There were other differences between the two chambers of Parliament. For example, the Assembly of Deputies decided regarding the budget and military laws, apart from this distinction, both assemblies that formed the Parliament had the same attributions related to the proposal, discussion, and voting of laws.

In addition, the deputies had a mandate of 4 years and the senators of 8 years (but after 4 years, the composition of the Senate was changed in proportion of 50% by drawing lots). Another specificity consisted in the fact that all the members of the Assembly of Deputies were elected, while in the Senate, there was, excluding the elected members, also a minority represented by the ex-officio members. The ex-officio members were: the heir to the throne after reaching the age of 18, a professor each from the Universities of Bucharest and Iassy, the metropolitans, and the bishops.

The amendment of the Constitution in 1879 by removing the religious restriction in the case of foreigners who intended to become citizens theoretically created the premises for increasing the number of voters. This amendment was reduced to the seventh article and represented one of the conditions imposed by the Great Powers for the international recognition of Romania’s state independence.

The condition established during the Berlin Congress of 1878 meant a violation of Romania’s autonomy, which is probably the reason why, although the change was made in the sense desired by the Great Powers, the naturalization procedure included criteria such as: living in the country for at least 10 years, good economic situation, appropriate moral profile, request for naturalization through an application analyzed by the Parliament, etc.

The listed criteria were difficult to accomplish, proof that until the First World War, fewer than 1,000 Jews received citizenship, Jews being the foreigners most concerned about this aspect.

Another amendment to the Constitution took place in 1884 and consisted in the reduction of the number of electoral colleges for the Assembly of Deputies from 4 to 3, but also in the reduction of the electoral census, as follows: in the first college the census was reduced from 300 galbeni7 or 4,000 lei to 1,200 lei, which allowed the entry in this college of the upper and middle bourgeoisie; at the second college (mainly of townspeople who practiced trade and crafts) the census dropped from 80 to 20 lei; at the third college the conditions remained unchanged regarding the census for the peasants. However, at the third college, teachers and priests were exempted from the electoral census, while literate voters were given the right to vote directly (Focșeneanu, 1992, p. 18). It resulted that only the illiterate, the majority at the third college, continued to vote indirectly.

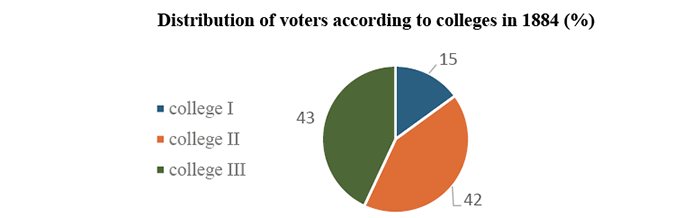

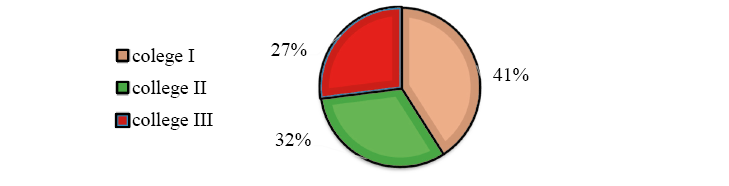

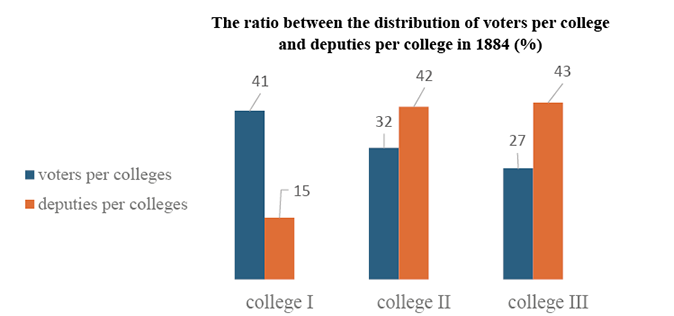

The distribution of the 59,477 voters according to electoral colleges was in 1884: 9,151 voters in the first college (15%), 24,750 – in the second college (42%), and 25,576 – in the third college (43%).

Regarding the level of representation calculated according to the number of deputies appointed by each college, the official statistics mention that out of the total of 183 deputies, 75 deputies (41%) were elected in the first college, 70 (32%) – in the second college and 38 (27%) – in the third college.

Representatives in the assembly of deputies according

to the college in 1884 (%)

As for the Senate, its members began to be remunerated, and although the two electoral colleges were maintained, the electoral census was reduced for voters. Thus, at the first college the census decreased three times compared to 1866, reaching 2,000 lei, and at the second college it was reduced 8 times, reaching 800-2,000 lei (Focșeneanu, 1992, p. 18).

However, although the 1884 amendments to the Constitution marked progress in terms of the level of the electoral census, they did not lead to a significant increase in the number of voters. Probably similar effects would have occurred if all the electoral colleges had been replaced by a single college reserved only for people who could read and write.

This idea appeared in 1882 in one of the most influential newspapers of the time, The Romanian, but it did not materialize. Despite the good intentions of liberal politician Constantin A. Rosetti, who initiated that campaign, it should be noted that the illiterate people were the majority, especially among the peasants.

With the application of the Constitution to the inhabitants of Dobrogea (territory entered into the possession of Romania in 1878), they were granted the right to have representatives in the Parliament, which is why the number of senators increased from 112 to 118, and the number of deputies from 183 to 191 (Mamina, 2000, p. 59).

As for the replacement of the census vote with the universal, mandatory, direct, and secret vote, this was provided for in the Constitution in 1917, but only for men who were at least 21 years old and were Romanian citizens.

The change in the type of vote occurred in the context of the First World War, when half of Romania’s territory was occupied by German, Bulgarian, and Turkish armies, and the Romanian soldiers were quite demotivated by the military failures of 1916. For this reason, the introduction of universal suffrage was accompanied by the mention in the Constitution of a future rural law, knowing that the soldiers, mostly peasants who faced the lack or insufficiency of land, were receptive to these subjects.

It should also be remembered that Romanian political life became more dynamic after the emergence of political parties, the most important being the National Liberal Party (formed in 1875) and the Conservative Party (founded in 1880), which succeeded each other in the government in the 19th century.

Other smaller parties were added to them, such as: the Moderate Liberal Party, the Free and Independent Faction, the Party of Honest Liberals, the Liberal-Conservative Party, the Radical Party, the Democratic Conservative Party, the Social-Democratic Party of Romanian Workers, the Party Nationalist-Democrat, etc., each with his sympathizers among the electorate.

Concerning women’s participation in political life, it was not legislated throughout the modern era, although aristocratic women participated in it unofficially, through the discussions held in the salons they held or through the influence they exercised over men.

The lack of legislative provisions regarding women’s involvement in politics was considered natural because women were considered intellectually and physically inferior to men, economically dependent on their parents and husbands. They took over the husband’s social status as well as his citizenship. For these reasons, women were assimilated to minors from a legal point of view.

In the 19th century, it was believed that a woman could not do anything without at least the tacit permission of her husband (Mill, 1895, p. 70). Furthermore, women are brought up with the idea that the ideal of their character is the very opposite of that of men; they are trained not to will by themselves, not to be governed by their own will, but to submit to the will of others. We will be told in the name of morality that a woman has to live for others and in the name of the feeling that her nature demands it (Mill, 1895, p. 45).

However, in the second half of the 19th century, women began to fight for their rights. In Romania, the priority is access to education, regardless of school level, and to work to become financially independent. It was only at the end of the 19th century that women began to claim political rights as well. All the requests were the result of the awareness that: The inequality of the rights of men and women has no other origin than the right of the strongest (Mill, 1895, p. 31).

After the First World War, when women distinguished themselves by their activities for the benefit of the military and civilians in need, several societies appeared to obtain the right to vote, such as the Association for the Civil and Political Emancipation of Romanian Women, established in Iassy in 1918 (Statutes of the Association for the civil and political emancipation of Romanian women, 2006, p. 508).

The first successes were recorded in 1929 when, through the administrative law, they received the right to vote and be elected in the municipal and county elections. Far from being universal, the right was conditioned, in addition to age and incompatibility limitations also valid for men, women being required to be graduates of gymnasium, normal or vocational school; clerks; war widows; decorated for wartime activity and participating, at the time of the promulgation of the law, in the management of societies that had supported social claims, cultural propaganda or social assistance (Administrative law, 1929, p. 2). Although the conditions were difficult to accomplish, the administrative law represented a chance for a political career for women.

It was only with the adoption of the Constitution of 1938 that political rights were granted to the inhabitants of both sexes, subject to the conditions regarding literacy, age, and field of activity.

Concluding remarks

In conclusion, we consider it necessary to draw attention to the fact that in the 19th century, everywhere in the world, the census vote was applied. It can be stated that no people in the modern period considered as citizens of the state all the individuals who lived in its territory as citizens of the state. Consequently, on one side were foreigners and those who did not have the legal age to exercise citizenship rights, and on the other side were people who had reached this age and were born in that country. Thus, some residents were citizens and others were not, a situation considered acceptable because a certain degree of openness and common interest with other members of society was assumed to be necessary.

In other words, those who were not of legal age (21) were considered not to possess the required degree of wisdom, and foreigners were considered to have no common interests with citizens. Although discriminatory, their situation is rectified in the case of some once they reach the age prescribed by law, and of others when, through residence, property, or relationships, they have reached the necessary degree of common interest and thus become citizens. However, the fact of being born in the country to parents belonging to the predominant ethnic group or the maturity of age were not sufficient conditions for someone to fulfill the necessary qualities to exercise citizenship rights. Poverty, lack of access to information, and lack of civic education made people as skilled in public affairs as children and no more interested in common matters than strangers. In conclusion, the additional condition that was imposed was that of economic independence, for it gave the people the free time they needed to reflect and exercise their political rights in an informed manner (Constant, 1996, pp. 79-80).

These findings also apply to Romanians during the analyzed period.

However, some conclusions strictly related to the situation in Romania are necessary.

After the end of the Phanariot regime, the political situation in the Romanian space improved in the sense that Romanians regained the right to choose their leaders, even though the rulers were validated in Constantinople by the sultan, and their election was made only from among the great aristocracy.

The modernization process entered a new stage with the intensification of contacts with the West, especially with France, which supported the national and reform projects of the Romanians. The Organic Regulations corresponded to some extent to the Romanians’ need for reform, as demonstrated by the articles regarding the separation of powers in the state or the emphasis on secularization. With the Organic Regulations, several clarifications regarding the participation of residents in political life appeared. Thus, by the characteristics of the time, participation targeted aristocrats (boyars) and only exceptionally city inhabitants, completely ignoring the peasants. More precisely, the boyars made the decisions in the state, while the inhabitants of the cities only contributed to the election of the rulers. It can be said that the peasantry, which represented the majority of the population (over 80%), was forbidden to participate in voting and political life. Moreover, the modern provisions of the Organic Regulations were inoperative in some cases due to the abuses of that period by the rulers, but also by the Russian Empire, which exercised its protectorate over the Romanians.

For this reason, it is not surprising that in 1848 the revolutionaries wanted to abolish the Organic Regulation in Wallachia and expand the population’s participation in political life. For this, it was envisaged that all social categories would have members in the assembly with a legislative role. Also, during the revolution of 1848, demands were resumed such as: the abolition of privileges, the filling of positions according to professional competence, and the submission of all to the payment of taxes. This demonstrated the desire to impose the principle of equality of all citizens before the law, which implied identical rights and obligations for all residents.

The removal of the Russian protectorate in 1856 coincided with the intensification of modernization thanks to the proximity to the West. From that moment on, the situation of the Romanians improved because, against the backdrop of the collective guarantee of the Great European Powers, the possibility of the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire violating the rights of the Romanians diminished.

Thus, the unification of the Romanian Principalities became possible in 1859, after (in 1857) Romanians from all social categories were able to express their views on this political project.

During the reign of Alexandru Ioan Cuza, the level of population participation in political life increased to an unprecedented level, with one voter for every 8-9 inhabitants. As a result, the electoral body expanded, corresponding to the ruler’s need to obtain popular legitimacy for his reforms.

And during the reign of Charles I, the modernization process continued and even intensified. The principle of separation of powers in the state was better defined, the rights and freedoms of citizens were provided for and guaranteed by the Constitution of 1866. All social categories were able to elect representatives in Parliament, even though the degree of political representativeness was conditioned by the economic situation of citizens, this being a limitation resulting from the type of voting system, namely the census-based one.

Although at the beginning of Charles I’s reign the number of voters decreased as a result of the increase in the census rate, reaching one voter per 83 inhabitants, progress was not lacking. Among these progresses we mention the lowering of the census (1884); the exemption from the census of several professional categories (freelancers, priests, teachers, former state officials, etc.); the lowering of the age from which a citizen could vote.

Consequently, it can be stated that, gradually, the number of residents with the right to vote increased, culminating in the introduction of universal suffrage in 1917.

Another stage, equally important, but exceeding the period analyzed in this study, was the granting of the right to vote to women in 1938.

Bibliography

Berindei, D. (1974). The Revolution of 1848 in the Romanian Principalities. Bucharest: Academy Publishing House.

Bolintineanu, D. (1869). The Rulers of the regulation period and the history of the 3 years from February 11 until today. Bucharest: National Printing Office.

Constant, B. (1996). About freedom in the ancients and in the moderns. Bucharest: European Institute.

Constitution of 1866. https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/26844.

Djuvara, N. (1995). Between East and West. Romanian countries at the beginning of the modern era (1800-1840 ). Bucharest: Humanitas Publishing House.

Filitti, I.C. (1934). The Sources of the 1866 Constitution. Bucharest: Typography of the Universul newspaper.

Focșeneanu, E. (1992). The constitutional history of Romania (1859-1991). Bucharest: Humanitas Publishing House.

Hitchins, K. (1996). Romania (1866-1947). Bucharest: Humanitas Publishing House.

Iacob, G., Iacob, L. (1995). Modernization - Europeanism. Iassy: Al.I. Cuza University Publishing House.

Isar, N. (2006). The modern history of the Romanians. 1774/1784-1918. Bucharest: University Publishing House.

Isar, N. (2010). Romania under the sign of modernization. From Alexandru Ioan Cuza to Charles I. Bucharest: University Publishing House.

Law no. 167/1929. Administrative law, https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/gezdiobuge/art-375-alegatori-eligibili-lege-167-1929?dp=gm3tmnrxguzdq.

Liiceanu, G. (2017). The continents of insomnia. Bucharest: Humanitas Publishing House.

Mamina, I. (2000). Constitutional monarchy in Romania. Political encyclopedia. 1866-1938. Bucharest: Encyclopedic Publishing House.

Mill, J. S. (1895). The slavery of women. Bucharest: Publisher of the Socec&Co Bookstore.

Oțetea, A. (1957). Genesis of the Organic Regulation in History studies and articles, II, 387-402.

Preda, C. (2011). Happy Romanians. Iassy: Polirom Publishing House.

The Organic Regulations of Wallachia and Moldavia. (1944). vol. I. Bucharest: Eminescu Enterprises S.A. https://bibl-dlr.solirom.ro/baza-extra/Regulamentele-organice-ale-valahiei-si-moldovei-1831-1832%20%28ed.%201944%29.

Stan, A. (1992). The Romanian Revolution of 1848. Bucharest: Albatros Publishing House.

Statutes of the Association for the civil and political emancipation of Romanian women, in Mihăilescu, Ș. (2006). The emancipation of the Romanian woman. Bucharest: Polirom Publishing House.

Developing status of the Paris Convention. 057-058-studii-si-articole-de-istorie-LVII-LVIII_1988_1988.

Ştefănesu-Galaţi, A. (1924). Education and political culture - a national problem. Findings and guidelines. Cernăuţi: The voice of Bucovina Publishing House.

Tătărescu, G. (2004). Electoral and parliamentary regime in Romania. Bucharest: PRO Foundation Publishing House.

The Paris Peace Treaty. https://content.ecf.org.il/files/M00934_TreatyOfParis1856English.pdf.

Voinea, M., Bulzan, C. (2003). Sociology of human rights. Bucharest: Bucharest University Publishing House.

1 A complete union implied: a single leader from a European monarchical family, common institutions, neutrality and the inclusion in the legislative Assembly of representatives of all social categories.

2 Chosen from among Romanians over 35 years old, owner of land that produced an income of at least 3,000 galbeni and who had held public positions for at least 10 years.

3 Name given to several foreign gold coins, of variable values, which also circulated in the Romanian Principalities.

4 Approximately 690,000 people participated in the plebiscite, of which 682,621 voted favorably, and 1,307 declared against, the remaining 70,220 votes being abstent.

5 Leu, lei is the monetary unit of Romania.

6 Of the 686,193 voters, 685,696 agreed with bringing a prince from a European ruling family to the throne of Romania.

7 1 galben = 11,75 lei.