Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2021, vol. 22, pp. 10–36 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2021.22.1

Development Aspects of Archaeological Sites in Latvia

PhD oec. cand., Mg. sc. soc., Bac. iur., Andris Kairišs

Riga Technical University, Riga, Latvia

e-mail: kairiss.andris@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0820-2259

PhD iur. cand., LL.M, Irina Oļevska

Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands

e-mail: irina.olevska@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8255-4960

Abstract. Archaeological sites as part of cultural heritage satisfy a broad range of interests of different stakeholders. Along with satisfying cultural, social, scientific, etc., interests, their role is no less important in strategic socio-economic development.

Unlocking asocio-economic potential of archaeological sites requires clear vision of how to conserve and protect each particular site, how and by what means to maintain and manage the object as well as what to do with it next. It is widely acknowledged that archaeological sites, in particular those having the status of archaeological monuments, play a socially important role, but their maintenance and development often require significant investment. While the laws make owners of archaeological sites, both private and public, solely responsible for conservation, restoration and maintenance of cultural monuments in their property, there should be appropriate mechanisms that mitigate the financial and legal burden and support owners along the way.

Based on the review of legal regulation, scientific literature, information of the authorities and mass media, multiple expert interviews, consultations with professional archaeologists, and using an integrated socio-economic and legal approach to the researched issue, the article provides theoretical and practical insight into the actualities of archaeological heritage development potential in Latvia (making international comparisons) and possible solutions thereto.

Keywords: Archaeological sites, burden, cultural heritage, development potential, socio-economic use.

Latvijos archeologinių vietovių plėtros ypatumai

Santrauka. Nekilnojamasis kultūros paveldas, įskaitant archeologines vietoves, prisideda prie kultūrinių, estetinių ar mokslo poreikių tenkinimo, be to, tai dar ir socialinis, ekonominis išteklius. Jis gerina šalies įvaizdį, pritraukia turistus, skatina regeneraciją, daro įtaką vietos bendruomenės veiklai. Konkrečios archeologinės vietovės klestėjimu suinteresuotų asmenų ratas labai platus: nuo savininkų, kurie įpareigoti išlaikyti ir tausoti savo turtą, iki valdžios institucijų, kurios atsakingos už valdymą, stebėseną ir kontrolę. Suinteresuotųjų grupių skirtingų poreikių suderinamumas – raktas į socialiai naudingą archeologinio paveldo vietovių plėtrą.

Latvijoje archeologinėms vietovėms taikoma valstybės apsauga, kuri apibrėžiama kultūros paminklo statusu. Toks statusas archeologinių objektų savininkams nustato daugybę administracinių ir kitų teisinių apribojimų bei uždeda finansinę naštą. Straipsnyje analizuojama Latvijos teisinė ir praktinė paminklosaugos tvarka, ji palyginama su kitų šalių paminklosaugine praktika. Derinant teisinį, socialinį ir ekonominį požiūrį, straipsnyje administraciniais ir teisiniais aspektais analizuojami paveldo nuosavybės, tinkamo jo valdymo klausimai, archeologinių vietovių savininkams suteikiama finansinė ir informacinė parama, jų tarpusavio bendradarbiavimas. Ieškoma atsakymo, ar dabartinėje situacijoje nekilnojamojo archeologinio objekto nuosavybė yra savininkui našta, ar galimybė.

Straipsnyje teigiama, kad, nors skirtingų rūšių archeologinės vietovės turi skirtingą ekonominį potencialą, net ir tos vietos, kurių ekonominis potencialas nedidelis, pavyzdžiui, senovės kapinynai, tinkamai prižiūrimos ir išplėtotos gali duoti pajamų. Straipsnyje pateikiama Latvijai būdingų archeologinių vietovių panaudojimo būdų įvairovė, parodoma, kaip archeologinės vietovės gali būti panaudojamos ne tik kaip domėjimosi objektai, bet būti ir atitinkamų įvykių fonas, informacijos ir (ar) kūrybinio įkvėpimo šaltinis.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: archeologinės vietovės, administracinių ir teisinių ribojimų našta, kultūros paveldas, plėtros potencialas, socialinis ekonominis išteklius.

_________

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank the deputy director of Ventspils museum, leading researcher, Dr. hist. Armands Vijups and the head of the Department of circulation of cultural objects of the National Heritage Board, Mg. hist. Jānis Asaris for their professional advice and critical evaluation of the research results, Dr. hist., Dr. habil. art., professor Juris Urtāns and Dr. hist. Artūrs Tomsons for counselling the authors, as well as the Latvian Society of Archaeologists (the LSA), and in particular its head, PhD. hist. cand. Mārcis Kalniņš, for consultations and assistance in conducting a survey of members of the LSA. The authors would also like to thank all participants of the expert interviews and a survey of the LSA.

Received: 04/10/2021. Accepted: 02/11/2021

Copyright © 2021 Andris Kairišs, Irina Oļevska. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The concept of cultural heritage, including archaeological heritage, is closely linked to the concept of value, or, in other words, the ability to meet different interests and needs of the stakeholders. This applies to both movable and immovable archaeological heritage. However, unlike antiquities, which nonspecialist cannot usually see anywhere but in a museum, immovable archaeological objects1 are often closer to us, forming part of the environment and social life of many people. The importance of the archaeological heritage in satisfying certain interests is difficult to underestimate, although it is being increasingly considered (e.g., Muzichuk, 2017, p. 9), that the value of immovable cultural heritage, including archaeological sites, is no more limited to just satisfaction of cultural, aesthetic or scientific needs, but plays a role of a strategic socio-economic resource. While a primary objective of heritage management remains the preservation of monuments in situ (ICOMOS, 1990, Art.6; The European Convention for the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage, 1992, Art.4), it is both able and demanded to contribute substantially to place-making (e.g., enhance the image of the area, make it attractive for living), tourism, regeneration, branding, local community livelihoods, etc. (Gould and Burtenshaw, 2014, p. 3; Burtenshaw, 2014, p. 50; CIfA, 2021, p. 12). Thus, the range of stakeholders interested legally, economically, culturally, or otherwise in prosperity of a particular archaeological site is very broad: from direct owners, obliged to maintain and conserve their property, through governments, responsible for strategic management, monitoring and control, to a broader society, interested inter alia in transmission of collective memory to future generations.

Although the social function of immovable archaeological heritage is widely recognized , the maintenance and development of heritage sites may require appropriate investment from their owners, which, together with current or potential administrative and economic constraints, may foster the discrepancy or even conflict of interest between site owners and the broader society.

Latvian situation in this context has been previously analyzed, up to the authors’ knowledge, at least once. Thus about 20 years ago a study by the Institute of Economics of the Latvian Academy of Sciences (IELAS; Karnite 2002) was published, which addressed similar questions in the wider context of cultural heritage. This study concluded, inter alia, (Karnite, 2002, pp. 54, 57–58) that due to restrictions imposed on the economic activities, monument modernization opportunities, decision-making on one’s property, and some other reasons, there is lower profitability and limited opportunities to earn income from the owned cultural monuments, while these objects, including archaeological monuments, properly prepared and presented, can be a tourist attraction and thus used to generate revenue. The study showed that large part of the surveyed owners considered benefits granted by the state insignificant and therefore additional costs arising from the status of the property – a cultural monument – unrecoverable.

With the development of different aspects of life in the last 20 years and taking into account that different types of cultural heritage objects may have different development potential, the authors have decided to make a detailed analysis dividing the objects into typological groups. This paper, being the second in a series of authors’ articles2 dedicated to the development of the socio-economic potential of cultural heritage3 analyzes this potential of archaeological sites. Thus, the main question raised by the authors of the research was whether, in the current state of the legislative and practical order in Latvia, ownership of an immovable archaeological object presents a burden or an opportunity for its owner? The paper in particular analyzes administrative and legal aspects of ownership, issues of proper management and possibilities of using archaeological sites in economically beneficial activities. Consequently, the analysis makes it possible to uncover the issues that limit the owners or help them in developing the socio-economic potential of their archaeological property.

For the purposes of the present research, the authors have utilized the mixed method of research design for exploration of an under-researched topic. Different sets of data (qualitative and quantitative) have been collected. Thus, the authors have studied current statutory regulations related to obligations of the owners and usage restrictions of archaeological sites in Latvia and for comparative purposes in the neighbouring countries, analyzed scientific literature, governmental and news feed information, statistical information and reports of supervisory authorities, municipalities et al. institutions and organizations, visited a number of archaeological sites in Kurzeme (Western region of Latvia), as well as:

• conducted eleven expert interviews with municipalities, tourist information centers, National Heritage Board (NHB), NGO, professional archaeologists and a private owner;

• received ten survey responses of professional archaeologists – members of the LSA;

• received consultations on specific issues from several professional archaeologists (who have many years of experience in the field).

Basic statistical data and regulatory aspects

According to the data from the Monuments’ Register,4 archaeological monuments (2525 in total) is the second largish group of cultural monuments after the architectural monuments, making about 34.2% of all immovable cultural monuments in the country.5 Besides, its number increases over the course of time (IR, 2013), due to the application of new technologies and the work of researchers and enthusiasts. Thus, 68 new hillforts6 have been discovered in Latvia in 2018–2021 (LKA, 2021), while in May 2021, nine new hillforts were discovered in Eastern region of Latvia – Latgale (LSM, 2021) – and in summer five new hillforts were discovered in Western region of Latvia – Kurzeme alone (KM, 2021).

The most common types of archaeological sites in the country are burial grounds (accounting for about 62.5% of all archaeological monuments), hillforts, cult places, castles and their ruins, settlements and historical events places.

Depending on the level of scientific, cultural and historical, or educating significance of the particular site, it may be included in the list of State protected cultural monuments as a cultural monument of State, regional or local significance.7 According to the data from the Monuments’ Register, there is almost equal amount of archaeological objects of State (1252) and local (1259) significance, while archaeological monuments of regional significance are only 14.

As of 2014, most archaeological monuments are owned by natural persons (40%), followed by public organizations (28%), municipalities (17%), state (7.5%) and commercial organizations (7.5%). Although the latest data are not available, one can assume that the share of private property is gradually increasing.

Most professional archaeologists and a number of persons interested in archaeology are united in the LSA. Founded in 2009, in October 2021 it had 70 members (including the authors).8

Latvia has a developed regulatory framework for the protection of archaeological sites having status of a cultural monument or candidating to become such against unauthorized and criminal activities. Extensive responsibility is placed on the owners of the objects. The umbrella law for the protection of cultural heritage – the Law on Protection of Cultural Monuments (Protection Law) – provides that the owner is solely responsible for conservation, maintenance, renovation and restoration of a cultural monument (Section 24). This responsibility is accompanied by a range of administrative and other legal restrictions that are targeted at immediate and/or future protection of the site, including its historical, scientific and artistic value, its unity, access to such monument or its visual perceptibility.9 Nonconformity to the legal obligations of the owners is subject to administrative liability,10 while a range of illegal activities on cultural monuments (including their damage, destruction and desecration) is subject to criminal liability.11 On the other hand, there are certain privileges the owners of the archaeological monuments are entitled to, e.g., real estate tax reliefs, restoration cofinancing programs on municipal, state and supranational level (thus several archaeological objects were preserved/restored), the right to charge viewers for visiting the site, etc.

Socio-economic use of archaeological objects

In order to answer the question about the factors hindering or promoting the development of archaeological heritage objects, firstly it is necessary to determine how archaeological objects are used to satisfy various interests.

Thus, in order to determine the types of socio-economic use of Latvian archaeological objects, the authors performed a multi-stage inductive analysis:

1) the archaeological objects that are most typical for Latvia were determined. Publicly available statistical information of the Monuments’ Register was taken as a basis, selecting all Latvian archaeological monuments and grouping them by assigning corresponding types (there are no standardized types of archaeological monuments indicated in the Monument’s Register). In some cases, the types of archaeological sites may overlap, but the following major groups of sites were defined during the analysis (the authors consulted professional archaeologists who have long experience in the field to specify the types assigned):

• residences (e.g., castles and their ruins, hillforts etc.),

• religious/cult objects,

• burial places,

• places of historical events (e.g., battlefields, meetings’ venues),

• infrastructure and household objects,

• military objects;

2) using scientific literature, mass media publications, information of state institutions and municipalities as well as materials of expert interviews (Interviews 1–10), information on the most common examples of use of archaeological objects (the activities) was collected;

3) a connection between the types of archaeological objects and the activities has been determined. It should be noted that the activity was linked to an archaeological site of certain type, given the popularity (incidence) of the corresponding activity in relation to the site type in question. Thus, it does not unambiguously mean that a particular activity is inapplicable to other (de-linked) archaeological site types at all;

4) grouping of activities was performed, combining them into socio-economic activity groups (the subcategories). A total of 17 subcategories were defined. The most significant difficulties at this stage of the analysis were associated with the fact that an activity may relate to several subcategories. The solution was found by identifying the subcategory with which the activity is more frequently associated, as well as clarifying the attribution of these activities with professional archaeologists;

5) grouping of the specified subcategories was performed, combining them into five broad and interconnected categories (these categories correspond to the most significant types of use of archaeological objects):12

• attraction of visitors (including tourism development),

• development of scientific potential (implementation of scientific and popular-scientific activities),

• implementation of educational and informative activities,

• promotion of social belonging and cohesion,

• support for fine arts and other artistic creations;

6) the results of the performed analysis have been specified in consultation with professional archaeologists who have long-term experience in the field.

In the course of the research, it was concluded that archaeological site can be an object of direct interest (e.g., it can be visited in order to get to know the site itself, to enjoy or study it), as well as to serve as a background for corresponding events (e.g., memorial, patriotism-related events, knight tournaments, wedding ceremonies or spiritual development) or as a source of information (e.g., on aspects of ancient technology) or creative inspiration. It should be noted that even in cases where the archaeological site initially serves as a background, it may also be an object of direct interest, e.g., if a visitor comes to a city festival, he/she, charmed by the local castle, visits its exposition.

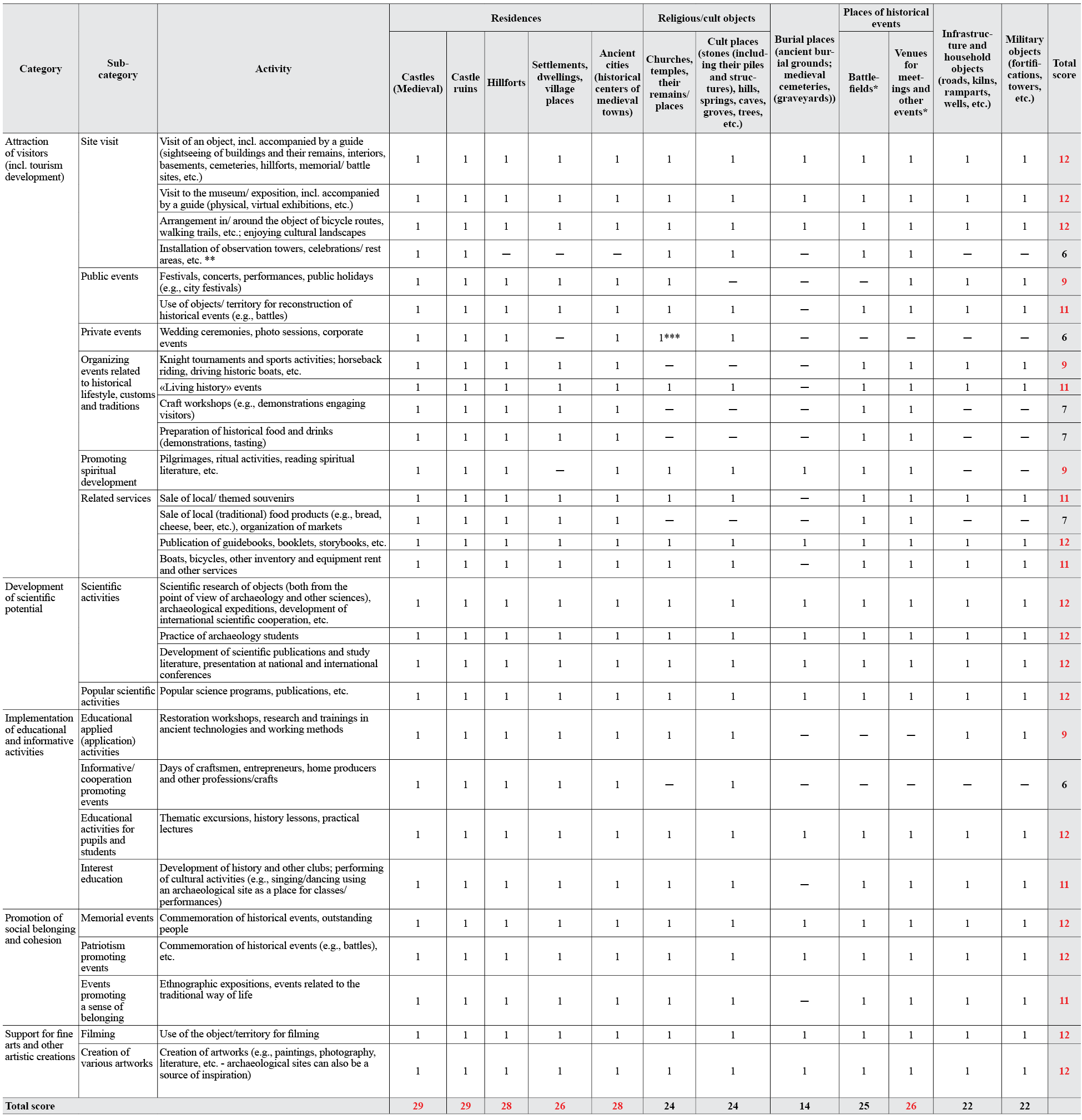

The type of socio-economic use of an archaeological object depends to a large extent on the type of this object, mainly due to such reasons as, e.g., protection, usefulness or ethics. For instance, observation towers are not (or should not be) installed in places where they may “disturb” the cultural layer (e.g., hillforts) due to preservation reasons; festivals and corporate events are not usually held in ancient cemeteries (ethical component); craft workshops are not held in cult places (like caves etc.) (usefulness component); church ruins and the like are not usually suitable for fairs and tastings of historical food (ethical/religious reasons). Thus, while all groups of archaeological objects can be used for the purposes of development of scientific potential and supporting creation of works of art, certain activities within other categories, taking into account, e.g., the above examples, are not that largely applicable. Without diminishing the importance of any type of object, it should be noted that in Latvian context residences have the largest socio-economical usage potential, while burial places have the most modest one (see Appendix 1 “Examples of socio-economic use of archaeological sites”). At the same time, it should be noted that the possibilities of using a particular object, even being of the most “usable type”, depend to a large extent on its recognizability (including attributable historical events, outstanding personalities, etc.), differences from other similar objects, preservation and orderliness, quality and diversity of provided services (e.g., to tourists and other visitors), attractiveness, location and accessibility of the object (including surrounding infrastructure), development of the surrounding area and other factors. Thus, the belonging of a particular archaeological object to this or another group of objects cannot in itself be the only determining factor in the realization of its development opportunities.

Restrictions on the rights and administrative obligations of the owners

There is a number of restrictions and administrative obligations related to the owners of archaeological monuments. While restrictions provided for in the Protection Law apply to all groups of cultural monuments, a few primarily concern archaeological sites (e.g., those related to on-land economic activities, since taking into account the location of archaeological sites in rural areas and forests, the use of relevant land plots in agriculture and forestry is more intensive).

State’s right of first refusal

State has a pre-emptive right over any cultural monument of State significance being alienated.13 The owner is entitled to independently decide on time, terms and conditions of the deal, but is obliged to submit the agreement to the NHB prior to registration of the property rights in the Land Register to the potential buyer.14 In practice it means that the seller and the buyer should fully agree on the terms of the agreement, but they cannot realize their deal unless the state authority takes its final decision, which is either to accept the contract terms as they are (de facto, replace the potential buyer) or refuse to use its pre-emptive right and allow the deal to progress. If there is no direct positive or negative reply from the state authority regarding the usage of pre-emptive rights, the seller and the buyer may proceed with registration of the deal in the Land Register not earlier than in 68 days from the date of submission of the agreement to the NHB (in this case it is presumed that the State has refused to use its pre-emptive right). This requirement, however, is not applicable to the monuments of regional and local significance.

Restrictions on division and alienation of a cultural monument

The owner is not allowed to alienate separate parts of one cultural monument or a complex of monuments, as well as to divide or join land if, as a result, preservation of a cultural monument is endangered.15 Besides, the owner is also not allowed to sell the land of the cultural monument separately from its protection zone, if both are owned by the same person.16 Nonconformity to these rules may lead to invalidation of the deal.17

The owner is also obliged to inform the NHB about the intent to alienate cultural monument prior to the deal. Alienation can take place if an NHB inspector, where necessary, has inspected the cultural monument, and its future owner has received instructions and explanations from the NHB on the use and preservation of the cultural monument.18 Administrative liability (in a way of a warning or fine up to 250 EUR19) may be applied to the owner for the failure to provide information about alienation of the cultural monument.20

Works on the territory of cultural monument

Prior to any research work, including archaeological research, as well as conservation, restoration and/or renovation works, a written permission of NHB should be obtained. These works are to be performed under the control of NHB. The use of devices for the detection of metal objects and material density (e.g., metal detectors) also requires prior permission of NHB.21

The owner has to ensure surveying of cultural values before commencing construction (incl. road infrastructure), land amelioration, extraction of mineral resources, and other economic activity on the territory of the cultural monument.22 Besides, if any archaeological or other objects with cultural and historical value are discovered occasionally or due to any economic activity on the land plot, the owner is to immediately notify the NHB and suspend any further activity.23 In this case, the newly-discovered objects come under protection of the State until the decision to include such objects in the Monuments’ Register has been taken. The decision-making process can take up to 6 months.24 As mentioned by several experts (Interviews 3, 10; Diena 2021), some private owners, even despite the possible liability provided for in the law, tend to hide the fact that archaeological objects have been uncovered on their land, so that any potentially damaging activity (including agricultural or forestry) is not frozen during and after the inspection of the place and the property is not recognized as the newly-discovered cultural monument, thus immediately becoming subject to the above restrictions and limitations. Thus, potentially valuable archaeological finds may not come to the attention of scientists and the public, as well as the identification of newly discovered archaeological monuments may suffer.

Inscription in the Monuments’ Register

A proposal to grant the status of a protected cultural monument and its inclusion in the list of State protected cultural monuments shall be submitted to the Minister of Culture (in case of monuments of state or regional significance – by NHB, in case of monuments of local significance – by the local government or NHB25). The process can be started, based upon the state initiative (by NHB itself), the owner of the object or any other interested party. In the latter case (the so-called “bottom-up initiative” by, e.g., an archaeologist, for additional protection of a particular object), the range of formal steps expected to be performed by the initiator is quite resource-intensive and time-consuming (Interview 10). Thus, the complexity of the formal procedure may discourage the interested party from proposing of the otherwise valuable object for inclusion in the Monuments’ Register.

Another issue worth to be mentioned, is the effect of the owner’s opinion on the decision-making process. When the owner is not the initiator, he/she, nevertheless, is to be informed about the proposal. Even though the opinion of the owner (possessor) is to be ascertained, his/her consent is not necessary for the inclusion of an object in the list of State protected cultural monuments.26 The Protection Law provides that the owner in this case is to be granted with tax relief or compensation for losses if such have occurred as a result of restrictions on the use of the land or the object.27 Both these mechanisms of supporting the owners can be found in the laws of other countries. Thus, compensation mechanisms for restricted ownership rights due to public inscription are provided for in the laws of, e.g., Portugal28 and Finland,29 whereas deductions of different tax types (for maintenance, investment in conservation, repair, etc.) are provided for in the laws of, e.g., Spain30 or Lithuania.31 In Latvia, real estate tax relief for the cultural monuments is a common practice, while the authors are unaware of any compensation cases for losses caused to the owner due to the enlisting of his property into the list of State protected cultural monuments.

Restrictions on economic activities

As a general principle, cultural monuments are to be used for purposes of science, education and culture. Economic activities shall be permitted only if such activities do not damage the monument and do not reduce the historical, scientific and artistic value thereof.32 Economic activity in the protection zones (protection strips) around cultural monuments (which, if not specially fixed, are 500 metres in rural areas and 100 metres in cities33) may only be performed with a permit from NHB.34 Exact instructions on restrictions of economic activities are to be issued by NHB to the owner of a cultural monument.35

Since certain types of archaeological monuments are mostly or solely located underground (e.g., ancient burial grounds) or their topography allows performance of agricultural or forestry activities (e.g., battlefields, hillforts), there is no uniform attitude of NHB on whether these activities endanger the underground monument or not. Generally, at least until the end of investigation and adoption of the final decision on newly-discovered monument, any activity at the territory is suspended. In certain cases, such decisions may be too restrictive (e.g., if there had been potato field upon the burial ground for many years and the cemetery has just been detected, there is no need to immediately terminate any activity since there is little risk of earlier unexperienced damage (Interview 5)). On the other hand, the issue of additional consideration in this respect is of ethical nature – how ethical it is to grow crops above the burial ground and what is the attitude of the landowner and buyers of agricultural products toward the harvest coming from the grave land?

Limited possibilities for modification of a cultural monument

Substantial part of Latvian archaeological monuments is overground (e.g., castles, their remains, etc.). The owner is responsible for proper renovation and restoration thereof.36 Current regulation provides for strict limitations on reconstruction works prescribed by law,37 Cabinet or municipal regulations, and instructions issued by NHB to the new owners of the cultural monuments.38 Modification of a cultural monument or replacement of the original parts thereof with new parts shall be permitted only if it is the best way to preserve the monument or if the cultural and historical value of the monument does not decrease as a result of the modification.39 Restoration, reconstruction, repair and conservation works of a cultural monument may be performed only under the management of a competent specialist (for the works on archaeological monument archaeologist should be engaged).40 Thus, restoration of a cultural monument requires higher quality and more professional work, than an ordinary building (Karnite, 2002, pp. 24–25). Several experts have mentioned that system of construction regulations applicable to cultural monuments is not flexible so tailor-made solutions should be introduced for renovation of cultural objects in conformity with modern standards (Interview 3).

Maintenance of archaeological monuments

Maintenance of archaeological monuments, which is to be determined by instructions of NHB,41 is one of the main duties of the owner.42 It is prescribed that maintenance, which does not modify the cultural monument and does not reduce its cultural and historical value, does not require a special permit, however, the owner is to inform the NHB in writing ten days before the commencement of the works referred to, if it is not specified otherwise in the issued instructions.43

Neither legal acts, nor instructions of NHB (generally44) provide for specific maintenance works, their type or frequency, related to archaeological monuments. It might be therefore unclear what maintenance within the context of archaeological sites is exactly implied. Some other countries approach this issue differently. Thus, Lithuanian law, for instance, provides that the manager of an immovable cultural property must keep up an object of cultural heritage, the territory thereof, timely remove emerging defects and protect structures against adverse environmental impact; maintain adequate microclimate conditions in premises with valuable interior; timely renew vegetation, remove volunteer plants, mow grass and trim trees, clean debris and eliminate sources of pollution within the territory; keep up and maintain historical green areas which are objects of cultural heritage in compliance with the heritage maintenance regulations.45 In England and Wales maintenance includes fencing, repairing, and covering, of a monument and the doing of any other act or thing which may be required for the purpose of repairing the monument or protecting it from decay or injury.46

In Latvia there have been attempts to determine and structure the maintenance works of archaeological monuments depending on the type of the monument. Thus, e.g., there have been recommendations prepared within Estonian–Latvian cross-border co-operation program project “Unknown cultural heritage values in common natural and cultural space”,47 however, these recommendations have not been widely accepted/implemented. Moreover, from the conservation point of view, lack of maintenance taking the form of unkept or overgrown, etc., ancient burial ground or a hillfort does not damage the site as such, but rather provides visual discomfort and limits accessibility to the monument. The experts acknowledge that currently there is no state policy on proper management of, e.g., hillforts (LSM 2021).

Treasure hunting and unearthing of antiquities

The archaeological heritage in Latvia, despite the significant progress made since 2016, is still threatened by illegal diggers. It is recognized, that ancient burial grounds are most vulnerable to attacks of treasure hunters, as they have the richest range of antiquities (IR, 2013) and are often located in sparsely populated areas, forests, etc., making them easier to access unnoticed and therefore attractive to carry out illegal activities (Kairiss, Olevska, 2021 (1), p. 297).

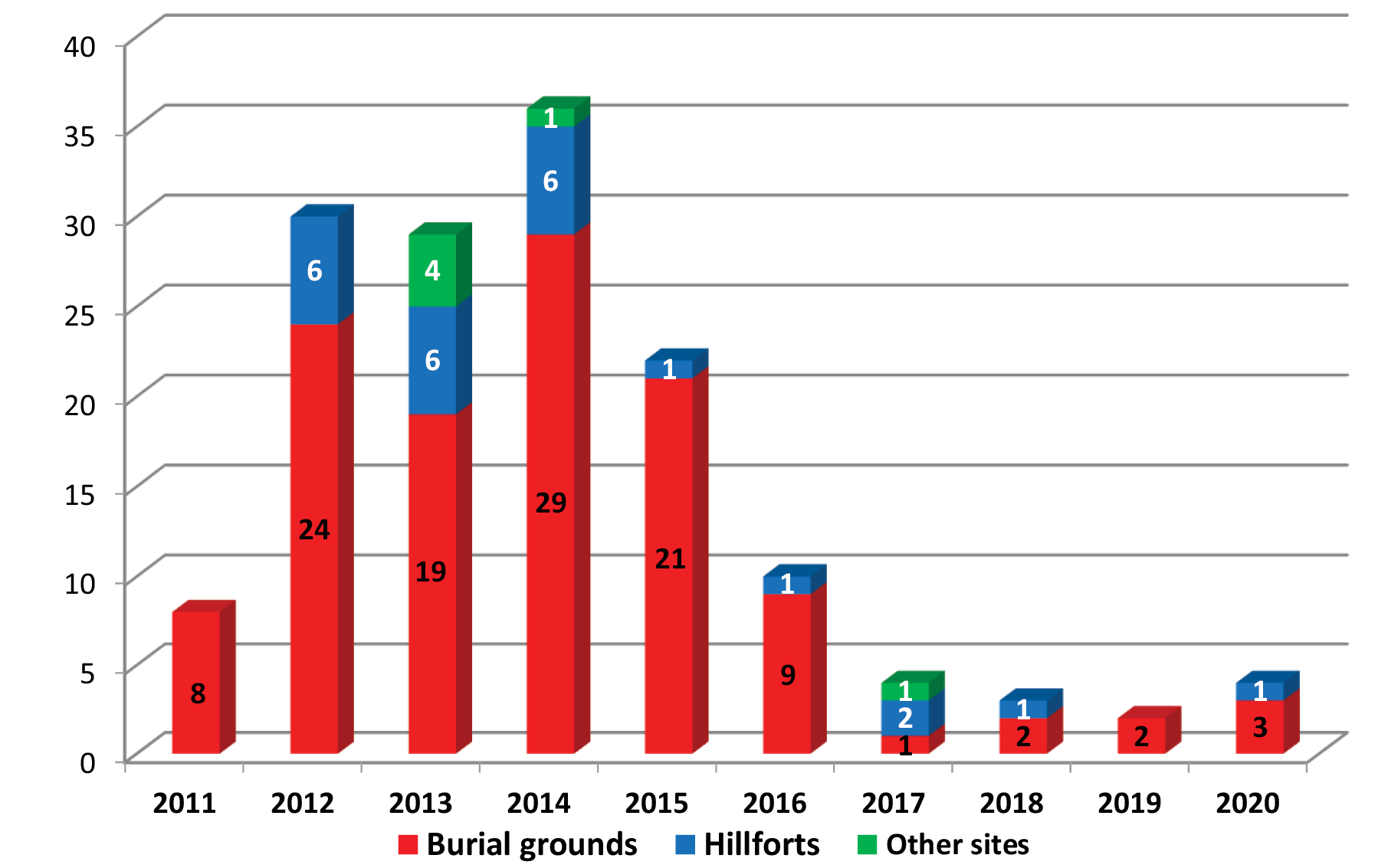

Fig. 1. Detected damage cases (as a result of treasure hunting) of archaeological monuments in Latvia (Kairiss, 2020, p. 60; National Heritage Board data48).

1 pav. Nustatyti pažeidimų atvejai dėl archeologinių paminklų lobių medžioklės Latvijoje (Kairiss, 2020, p. 60; Nacionalinės paveldo tarybos duomenys)

Figure 148provides data on the fixed cases of monument’s damage found in Latvian archaeological sites, which have been classified as criminal offenses and served as a basis for initiation of criminal proceedings. Figure 1 shows the number of offenses rather than looted burial places, though several (sometimes even hundreds) individual burial places can be destroyed as a result of a single crime. It should be noted that the number of registered criminal offenses related to illegal activities against cultural monuments is usually higher than the amount of respectively initiated criminal proceedings,49 while significant part of the initiated criminal proceedings are suspended and only a few are sent to prosecution and go to court (Kairiss, Olevska 2021, p. 311).

There are no direct legal obligations of the owners of archaeological sites to protect their property from illegal diggers or prevent illegal intervention, except for the general rule of proper maintenance. Thus, for instance, it is generally accepted that the owners are to put in order the burial sites damaged by treasure hunters at their own expense. It is a general practice of NHB to not punish the owners for insufficient protection and the following damage to their sites if the damage has been caused by third parties and there is no direct fault of the owner (NHB information).

The owners approach the question of prevention and protection differently. As a method of prevention, some owners, for instance, scatter small metal objects to make metal detectors incapable of identifying (distinguishing) antiquities (Interview 9). Prevention function can also be performed by raising social awareness. Thus, e.g., one of the most positive examples is the one of Grobiņa town. About ten years ago the systematic work of development of its archaeological ensemble began and the local inhabitants were actively engaged (in studies, information dissemination, volunteer works, etc.) in the process.50 As a result, they have achieved the high level of self-regulation in the society, since the locals are the first to inform the police about suspicious activities or metal detectorists on the territory of the archaeological site (Interview 2).

In order to put the ancient burial grounds in order, some owners do it by themselves (Interview 9), others address the Cultural monuments conservation and restoration program discussed below (LVM 2019). It should be noted that in the absence of strong support from the State or municipality, precise obligations and clear instructions how and when to put the damaged site to order, sometimes the site remains unkept or keeping up happens years after the accident (e.g., in 2018 JSC “Latvijas valsts meži” performed cleaning/maintenance works on the ancient burial ground of state significance three years after it was damaged by illegal diggers, LVM 2019).

While the above relates to intentional illegal digging, accidental unearthing of antiquities is not less important issue that is worth mentioning. Protection Law provides that antiquities found in archaeological sites (dated until 17th century included) shall belong to the State.51 This is the only legal norm that might be considered rendering state ownership rights over undiscovered cultural objects.52 According to the official interpretation of the law by NHB, “archaeological sites are considered to be ancient sites which have been included in the list of state protected cultural monuments as archaeological monuments or which have been granted the status of a newly discovered cultural (archaeological) monument.”53 At the same time, Protection Law provides that private ownership of antiquities of 17th century or older is allowed in case of proper registration thereof before 30 March 2013, or after that date, if legal origin of the antiquity has been proved and NHB has issued a written certificate confirming it.54 Ownership of antiquities, unregistered according to the above procedure, is considered to be illegal (LV Portals 2018). Taking into account the above, it is unclear, whether antiquities found outside the enlisted archaeological sites (in the previously unknown ancient place or outside of any ancient context) can be privately owned.55

Besides, if the object that might have historical, scientific, artistic or other cultural value is found, the finder is to inform NHB in writing about the fact, location and conditions of the finding within five days.56 Protection Law, being the special law in relation to the Civil Law, does not provide for any finder’s fee or procedure of attribution of legal ownership rights over the valuable object and/or antiquity. At the same time general rules of Civil Law state that if the object (concealed property) is found on one’s own or ownerless land the object belongs to the finder, if the object is accidentally found on the other’s land the ownership is dual (half belongs to the finder, half to the land owner), whereas if the object is looked for intentionally (without knowledge and permission of the owner) on the other’s land (which is forbidden) the full ownership acquires the land owner. Thus, for instance, money deposits, that sometimes are being found in Latvia, shall typically be acknowledged concealed property according to Civil Law (Grutups, Kalnins, 2002, p. 53). At the same time, according to ICOMOS 2021, in order to properly protect and manage the site, the stray finds collected by the land owners should be inventoried and included in museum collections (ICOMOS 2021, p. 51). Taking into account the above, unclear rules over private ownership of antiquities (the place of finding may be later recognized the newly-discovered monument with automatic State’s ownership of antique objects), absence of finder’s fee (no obligation of the State or museum to buy the object from the finder) and opportunity to avoid liability might deter finders from proper notification on the finding to the NHB. The aforementioned therefore might lead to inability of unveiling/registration of new ancient places requiring protection (newly-discovered cultural monuments).

The countries approach the issue of finder’s fee differently. For instance, Swedish law provides that ancient finds become the property of the finder, who is however (in certain cases) obliged to offer the State the opportunity to acquire it in return for payment.57 Norway provides for finder’s fee (equally divided between the finder and the land owner) to be set (in case of golden or silver finds) at least to the metal value by weight, with a supplement that must not be less than 10 per cent of the metal value.58 Poland entitles a finder of archaeological object to receive a prize.59

The above leads to the conclusion that the effectiveness of preventive activities, proper following the antiquities’ protection rules and combatting crimes against the archaeological heritage is largely based on legal certainty, public support measures for site owners, proper compensation to (legal) accidental finders and the development of the socio-economic potential of heritage sites, which in turn is based on public, private and nongovernmental cooperation.

Conservation v. Conservation & Development

Archaeological monuments, due to their fragile and unique nature, not only suffer from many of the same threats that impact other forms of heritage objects but also from particular risks specific to archaeological heritage, e.g., loss of in situ excavated archaeological objects (due to lack of maintenance plan or resources for their protection, conservation or management), loss of unidentified archaeological heritage (due to urbanization; road widening; railway building; dam constructions; underground parking in historic cities and modern agricultural deep ploughing), loss of archaeological potential (due to tight deadlines, improper information recording, and total destruction of the site caused by commercial or development projects), loss of diversity of archaeological heritage (due to the difference in value perception of certain types of heritage objects), etc. (ICOMOS 2001). Therefore, conservation of the archaeological heritage is one of the most important tasks (ICOMOS 1990, Art. 6) of all the stakeholders engaged and interested in the future of the monuments.

While conservation is undoubtedly a necessary step to prevent damage to archaeological sites, other important aspects must also be taken into account, e.g., is conservation alone sufficient to develop the potential of the archaeological heritage and by what means can the preserved site be maintained in the future? The problem is unlikely to exist, if the state or municipality has sufficiently large budget (or access to other funding) and the conservation of cultural heritage sites can be carried out without diverting significant resources from other areas (e.g., health protection, infrastructure development, etc.). However, in practice the situation is usually different. While the state and municipalities, as well as local residents are aware of the need of conservation, funding is often insufficient to address current social issues, so investment in conservation (especially in the sites located in sparsely populated areas, which are relatively seldom-visited and thus economically unattractive) can also be perceived as a kind of burden. Let’s imagine an archaeological site, e.g., a castle ruin, which is preserved and open to the public, but no measures are taken to promote it, visitors are not offered relevant services, events are not organized at the site, etc. In other words, little is done to promote its attendance and related direct and indirect economic effect (e.g., Kairiss, Olevska, 2020, p. 59) – in this case, the object is temporarily maintained (kept up) in the best possible condition, but its socio-economic effect and compliance with the interests of various stakeholders is insignificant (about stakeholders’ interests, see, e.g., Kairiss, Olevska, 2020, pp. 51–54). Thus, instead of eventually becoming a facilitator of the socio-economic development, the archaeological site becomes another expenditure item in the budget. Thus, there should be a clear understanding who is the real beneficiary of the conserved heritage, who, how and by what means is to maintain/repair the site and what to do with it next.

Latvia has best practice examples of the efficient use of properly preserved archaeological sites – besides already mentioned archaeological heritage of Grobiņa, there are at least the old city of Kuldīga or the castles of Cēsis, Turaida, Ventspils, Dobele, etc. Success stories of the development of these sites are largely related to conservation being implemented with the vision of future development. As mentioned above, the economic return of an object is not immediate and investments in it may outweigh the economic benefits for a long time, but, as it is known, in the long run cultural objects have a pronounced indirect income character positively impacting the socio-economic development. Therefore conservation, proper management60 and development of archaeological sites are equally essential.

In order for all these three components of a successful development to satisfy interests of different stakeholders, decisions on them cannot be unilaterally decided by one separate category (e.g., only by the State, or only by the owners). It should be a collaboration of at least those primarily concerned – owners, land managers, developers, local society and authorities, NGOs, etc.61 As mentioned by several researchers, this collaboration is assumed to promote the unified vision and strategic management and development plan, which might comprise, inter alia, appropriate use of the site, scope and limits to conservation, visitation (allowed amount of people, parts of the site allowed to be visited, charging for visitations), extent and nature of excavation and research, rules of maintenance and monitoring, facilities and infrastructure, consultations and further engagement of stakeholders (Teutonico&Gaetano 2002, p. 45).

The role of prioritizing and story-telling

Immovable archaeological object is closely connected to the place. It was created/used, developed and left as a result of a certain set of circumstances. It carries “history” and “culture” which is a motivating force for visitors, who want to know more about it, feel it, or even become part of it. For instance, even though it is not known exactly where the Battle of Durbe took place in 1260, events dedicated to the memory of the battle often take place in particular location in Durbe municipality, which are widely attended by local and foreign visitors (Interview 1; Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Durbe Castle ruins and recreation area. Photo by A. Kairišs.

2 pav. Durbės pilies griuvėsiai ir rekreacinis plotas. A. Kairišs’o nuotrauka

Similarly, even it is not known where exactly Couronian King’s Lamekins Castle was located, the description of Lagzdiena hillfort states that it was there.62 Therefore, real or, sometimes, realistically created story plays an important role in the development and attendance of the site (Interviews 4, 5), especially if it is well studied (both through documental and archaeological research) and reflects (or at least pretend to reflect) the particular period in details (Interview 6). The latter requires commitment of time, staff and finances in identification of cultural heritage objects at the territory and strategic decision on the basic site/historical period/event the future story is to be based on. Thus, especially in the areas rich in cultural heritage of different periods and types, this decision will also show what exactly is to be primarily developed, respectively what is to be the object of resource investments. Thus, e.g., Kuldīga emphasizes the heritage of the Duchy of Courland, but does not largely use two Viking sites, unlike, e.g., Grobiņa, which intensively develops archaeological sites related to Viking era (Figure 3). Also, the Veckuldīga hillfort is not being developed in Kuldīga (Interview 5).

Fig. 3. One of the typical bicycles parkings in Grobiņa town. Photo by A. Kairišs.

3 pav. Viena iš tipinių dviračių aikštelių Gruobinioje. A. Kairišs’o nuotrauka

Development of infrastructure

It is generally accepted, that contribution of archaeological heritage to the livelihood of local community is often achieved through tourism (Gould and Burtenshaw 2014, p. 3), whereas one of the most important aspects in increasing number of tourists is investment in tourism infrastructure (Jovanovic and Ilic 2016, p. 288). Even such seemingly low-maintenance sites as ancient burial grounds or hillforts, in terms of tourism development, still request certain degree of investment in laying a path, installation of benches, informational stand, waste bins with regular maintenance, lawn mowing and tree/shrub cutting, etc. However, not all the owners are willing to invest in or stimulate development of infrastructure around their site precisely because of the risk of increased inflow of tourists: the costs of managing and keeping up of the site generally (without government’s support) exceed the modest revenue of its public use. Here the important role plays mutual cooperation between the owner (and other stakeholders directly interested in the development and respective economic benefits from the site) and municipality/the State (interested in increasing the quality of life, creating positive image of the area, cohesion and cultural patriotism, etc.).

More complex approach implies connection of communications (water, heating system, sanitary facilities, etc.), access roads, catering and accommodation. This is mostly characteristic of above-the-ground sites which based on their type (e.g., castles or castle ruins) and state of conservation can be used for accommodation and/or long-term stay. Absence of minimal level of comfort narrows the development opportunities of these sites. Thus, e.g., in the absence of a working heating system, castle in Alsunga has only seasonal visiting (Interview 4, Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Alsunga Castle. Photo: A. Kairišs.

4 pav. Alsunga’os pilis. A. Kairišs’o nuotrauka

The role of scientific research

The development of the archaeological heritage potential is significantly related to the development of scientific research. It should be taken into account that archaeological research not only enriches science as such, but also provides valuable information and ensures evidence base for the development of the archaeological potential of the site or area, including facilitating the discovery of new monuments (Figure 5). Carrying out scientific research is one of the most important aspects of proving the significance of an archaeological site: thus, for instance, Grobiņa archaeological ensemble, despite its importance, was not accepted for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List because, according to ICOMOS, the current state of knowledge and research on the object and its context is not sufficiently well advanced to justify the proposed Outstanding Universal Value.63

Fig. 5. Drone fixation of the place of archaeological excavations at Bulduru hillfort, July 2021. Photo: A. Kairišs.

5 pav. Dronu užfiksuota archeologinių kasinėjimų vieta Bulduri’ių piliakalnyje, 2021 m. liepa. A. Kairišs’o nuotrauka

Although there are examples of best practice in collaboration between owners of archaeological sites (e.g., municipalities) and researchers, the initiators of the archaeological research are usually archaeologist himself/herself, his/her represented scientific/research institution or other history/culture-related institution. Municipalities or private owners are not so frequent initiators of archaeological research, if it is not prescribed by the law (LSA survey). At the same time, the surveyed archaeologists themselves indicate (LSA survey) that the results of research are most often (except for scientific purposes) used for (top 3 responses; multiple choice responses):

• granting the status of an archaeological monument (70% of respondents),

• marketing activities, better recognition of the object/territory, increase of tourist potential (60% of respondents),

• obtaining evidence of the archaeological significance of the site/area, as well as preserving the archaeological monument (50% of respondents).

It is worth noting that the main difficulties faced by archaeologists when they come forth as research initiators (LSA survey; multiple choice responses) are lack of funding (60% of respondents), refusal of landowners to cooperate (40%) and lack of interest of local government (20%). This indirectly indicates that:

• landowners and local governments may not have sufficient information or understanding about the possibilities of using the results of archaeological research in promoting the significance and recognizability of an archaeological site (if the research object is an archaeological monument);

• landowners may be concerned about possible administrative and economic restrictions if an archaeological site is discovered on their land.

In cases when an object or territory requires archaeological research and this research is not mandatory (e.g., in case of construction of infrastructure objects), the archaeologist most often (50% responses, multiple choice responses) finds out about it through personal contacts. There is no timely information available on the scope and type of work, where an archaeologist is needed, therefore the ordering customers cannot find archaeologists and archaeologists do not know that their services are needed. The solution could be that the responsible institution (e.g., NHB), according to the information provided by the customers, compiles a public list of places and objects where archaeological research is needed (LSA survey).

The development of scientific research requires the involvement of professional archaeologists, but the number of archaeologists (especially – experienced) doing fieldwork in Latvia is probably insufficient (40% responses64). The insufficient number of archaeologists is also mentioned as the reason why the competition of field archaeologists in Latvia does not exist or is low (40% responses) or average (40% responses). Moreover, the possibilities of obtaining high-quality archaeological education in the country are limited: there is, e.g., no master’s level programmes in archaeology, there is a lack of specialized education programmes (and a lack of corresponding teaching stuff), there are limited practice options for students, limited options to work with modern technologies, etc. (LSA survey).

Among the main obstacles to the development of high-quality archaeological research in Latvia, professional archaeologists mentioned65 (LSA survey):

• weak interest from the state, local governments and private landowners,

• weak (higher) education opportunities for archaeologists and insufficient professional qualifications of some existing archaeologists,

• lack of understanding of the need for archaeological research and general public ignorance about archaeology and its contribution to society,

• lack of funding for research and low salaries of archaeologists,

• destruction of archaeological sites as a result of illegal activities of treasure hunters.

Among the main contributing factors for the development of high-quality archaeological research in Latvia, professional archaeologists mentioned66 (LSA survey):

• a large number of unexplored archaeological sites,

• archaeologists’ own initiative to regularly self-educate, improve their qualifications, study abroad,

• possibility to attract funding for research,67

• good cooperation between specialists in the field,

• good cooperation with state (cultural) institutions and municipalities,68

• freedom of research work, as the existing regulatory framework is quite general.

Public attitude and engagement

Statistical information shows that in 2017 Latvia ranked 3rd, while in 2018 and 2019 2nd, in Europe at visiting museums per 100 000 inhabitants.69 In addition, it should be noted that in 2009–2020 the majority of the most visited museums70 contained archaeological collections. Research71 shows that visiting cultural and historical places (many of which represent archaeological objects) is gradually increasing. It should be noted that the involvement of the local community plays an important role in Latvia’s most developed archaeological sites. Thus, e.g., ICOMOS points to the active involvement of the local community in the development of the Grobiņa Archaeological Ensemble.72 Thus, it can be assumed that in Latvia there is public interest in the archaeological heritage.

The local and broader community is one of the most important stakeholders in the use of benefits provided by cultural (including archaeological heritage) sites. Thus, e.g., from the point of view of economic interests (Kairiss, Olevska, 2020, p. 52, 54), representatives of local community are often involved in tourism related economic activities (e.g., production of souvenirs, local food, crafts, develop catering, hotels services etc., organize events in the locations of cultural objects, establish private museums, organize guided tours etc.), work on heritage sites (e.g., legitimate excavations) and in museums. Broader public is interested in promoting quality of life and standard of living through society’s development in larger business opportunities (e.g., management of cultural heritage significantly impacts development in other fields, e.g., catering and hotels), and gains benefits in terms of development of scientific and educational potential, creating job opportunities, etc. Without the support of the local and wider community, as well as the private and nongovernmental sectors, the development of archaeological heritage potential is not only impossible, but also, in fact, meaningless, as it is the community that is the primary beneficiary of this development.

The development of the archaeological heritage is related not only to economic but also to other essential factors, e.g., an element of national pride (Interviews 5, 6) and the perception of the archaeological heritage one’s own. It should be borne in mind, however, that both local and broader population must be sufficiently informed about the national archaeological heritage and its significance, thus, e.g., public communication of the results and conclusions of archaeological research increases the involvement of the local community (Interview 6). The well-known Latvian manors’ researcher V. Mašnovskis (Interview 11), inter alia, notes that an important precondition for public involvement and support is the development of intellectual society and ensuring of appropriate education (involving professionals who know how to provoke corresponding interest) in the field of cultural heritage (already from school).

Support

It is generally accepted that the key to achieving the appropriate balance between private and public interest in heritage conservation and development depends on the application of objective, consistent, and thorough procedures for heritage assessment, and the provision of adequate resources for compensation of the restrictions introduced due to them (Throsby 2019). These resources or support can be in a form of tax reliefs or direct subsidies to the owners of the archaeological sites. Let’s look at the situation in the field of support for owners of archaeological objects currently in Latvia.

Tax regime

Cultural (including archaeological) monuments are not subject to any special tax treatment, except for the real estate tax. Thus, with certain exemptions (not generally applicable to archaeological sites), cultural monuments are exempt from the real estate tax.73

It is worth mentioning that real estate tax is calculated on the basis of cadastral value of the property.74 As far as many archaeological sites are located in rural areas where cadastral value is rather small, the corresponding real estate tax is small as well. Therefore, this tax exemption in certain cases does not substantially support or motivate the owners of the archaeological site. On the other hand, costs of maintenance, construction and repair works are high and do not fluctuate that much throughout the country, which makes it even harder for those owners, who are less financially protected. Some experts have mentioned, that state support in a way of other tax discounts (e.g., VAT on site’s restoration works) would be of great help to the archaeological sites’ owners (Interview 3).

The other countries approach these issues differently. Spain provides for Income tax deductions depending on the amount of investments the taxpayers make in the acquisition, conservation, repair, restoration, dissemination and exhibition of assets declared of cultural interest, as well as there is Income tax deduction from donations in goods that are part of the Spanish Historical Heritage.75 Romania exempts the owners of agricultural lands from paying the agricultural land tax for the archaeological research surfaces for the excavation time.76 According to its Resolution of 2015 towards an integrated approach to cultural heritage for Europe, European Parliament, inter alia, invited the Member States to look into possible fiscal incentives in relation to restoration, preservation and conservation work, such as reductions in VAT or other taxes, given that European cultural heritage is also managed by private bodies.77

State and supranational subsidies

There are several State supporting financial programmes currently available to the owners of the cultural monuments, including archaeological sites. These include, for instance:

• Cultural monuments conservation and restoration program, developed based on Protection Law, which promotes and supports the research, conservation and emergency restoration of cultural monuments. Under the programme, funding is allocated to cultural monuments of national and regional significance.78

• Competitions announced and administered by the State Culture Capital Foundation (SCCF)79 in several cultural industries, including tangible cultural heritage. The SCCF supports restoration of cultural objects with the aim of preserving the original substance, authenticity and mood created by the set of cultural and historical values.

Other targeted sources of financial support are also available. Thus, e.g., the Rural Support Service, responsible for implementation of a unified state and EU support policy in the sector of, inter alia, rural development, may be of help in cofinancing projects in rural area (Rural Support Service Law). The other option is availability of EU funds supporting cultural objects’ development processes.

Municipal subsidies and participation

Besides state or supranational support, a number of municipalities are also supporting and actively participating in the development of cultural heritage objects on their territory. It is acknowledged that local governments are increasingly recognizing the socio-economic role of cultural heritage and highlighting the importance of protecting cultural monuments in local government development programs (LV Portals 2014).

A number of municipalities implements a cofinanced project competitions every year in the field of restoration of historical objects, where archaeological research is the position of eligible costs (e.g., Cēsis municipality cofinances the costs of research and development of the archaeological inventory of the monument located on their territory or a part thereof80). Certain municipalities are active in international projects. Thus, e.g., Lūdza81 and Alūksne82 municipality participated in the international cross-border cooperation project within which, inter alia, 17 rescue excavations and a great number of field inventories were carried out, 4 digital archaeological databases were produced, a big amount of new archaeological information was gathered, recovered and preserved for future studies, etc.83

Even those monuments, which usually do not require restoration or renovation works (e.g., ancient burial grounds or hillforts), still need certain maintenance, including mowing, bushes’ pruning, setting the monument to order after visiting of treasure hunters, etc. Thus, since the legal requirements of protection and preservation of cultural (including, archaeological) heritage is the form of State imposed obligations, the respective support mechanisms (both when the owner faces unexpected restrictions in cases of newly-discovered monuments on his/her property (discussed above) and when the object is already known to the owner and needs ongoing repair and maintenance) should be available to the owners to mitigate top-down imposed financial burden. As is generally accepted and confirmed by, e.g., ICOMOS 1990 Charter,84 the provision of adequate funds for the supporting programmes necessary for effective archaeological heritage management should be ensured in order to proper perform the obligation of heritage protection. And if the law makes no provision for fair economic distribution, it “stands the chance of being perceived by a large constituency as irrelevant at best and oppressive at worst” (Brodie, 2010, p. 274). Nevertheless, according to several experts, the existing limitations overweight the available economic benefits offered by the current Latvian legislation (Interviews 3, 9, 10).

Conclusions and recommendations

1. Archaeological sites, provided they are properly managed and developed, play an important socially useful role and contribute to the socio-economic development of the surrounding area. Cultural monument status, which is typical to archaeological sites in Latvia, however impose a range of administrative and other legal restrictions, as well as financial burden (primarily – due to restrictions of economic activity) to the owners of these objects. The maintenance and development of archaeological sites requires time, labor and financial resources, but the existing compensation mechanisms available to the owners are inadequate to cover the relevant (including maintenance-related) costs. Insufficient cooperation between the owners of archaeological sites, the private, nongovernmental, municipal and public sectors, as well as the lack of economic support for the owners, create a mismatch between the interests of the site owners and the public. Consequently, the development of the potential of archaeological objects is hindered. Best practice examples show that cooperation and involvement of the local community is a key to unlocking the development potential of archaeological sites.

Recommendation: it must be ensured at the state policy level, that owners of archaeological objects do not at least suffer losses from the ownership of such property, implementing adequate mechanisms of support and compensation of the restrictions imposed on the owners. The mechanisms should include:

• incentive and supporting tax regime, providing discounts based on the amount of investments made in conservation, maintenance and restoration of archaeological sites,

• compensations for the restricted/suspended economic activity,

• support for conservation measures,

• free of charge consultations on the socio-economic development aspects of archaeological heritage objects.

2. The accessibility and development of archaeological sites depends significantly on the development of local infrastructure. This works vice versa as well (e.g., an increase in the number of visitors of the site affects the development of catering, accommodation, etc. services).

Recommendation: mutually beneficial cooperation between the owners of archaeological objects and local governments should be established and facilitated. This is not only a precondition for the development of archaeological objects, but also a factor of the socio-economic development of the municipal territory.

3. While different types of archaeological sites have different economic potential, even those sites with modest potential, e.g., ancient burial grounds, when properly maintained and developed can not only fulfil their basic scientific and cultural functions, but also generate revenue. The owners of archaeological objects are not always informed about the possibilities of socio-economic use of their objects, therefore, conservation (as a necessary and controlled measure) is brought to the fore, without sufficient attention to the means by which the preserved object will be further maintained. Archaeological sites (depending on the particular situation) can be used (types of use are not mutually exclusive):

• as objects of direct interest (e.g., they can be visited in order to get to know the sites themselves, to enjoy or study them),

• to serve as a background for corresponding events (e.g., memorial, patriotism-related events, public and private celebrations or spiritual development),

• to serve as a source of information (e.g., on aspects of ancient technology) or creative inspiration.

Recommendation: the conservation of archaeological sites must be carried out from the outset, paying close attention to their further use, as conservation alone does not ensure the development of the socio-economic potential of the sites. Raising the awareness of owners of archaeological sites (both private and public) should become part of public policy, shifting the emphasis from the conservation of cultural heritage to the development of its potential. This would promote the preservation of heritage sites, finding means for their maintenance and more efficient performance of the socially useful function of these objects.

4. Despite the developed regulatory framework in the field of protection of cultural (including archaeological) heritage, there are several uncertainties in the regulatory enactments related to the obligations of owners of archaeological objects concerning objects’ maintenance and keeping up, as well as notification of found antiques and their belonging (if found outside ancient sites/territories, which have not yet been granted protection status). Thus, for example, the sites damaged as a result of treasure hunters may be kept up late, and the discovery of new archaeological monuments may suffer.

Recommendation: improvements in the legal framework should apply to:

• adoption of guidelines for the maintenance of archaeological monuments, taking into account the types of sites;

• development of the procedure for keeping up archaeological monuments if they have been damaged by treasure hunters and the perpetrators have not been identified (or before they have been identified);

• improvement of regulation of the obligation to notify (and liability for undue notification) of the antiquities accidentally found outside state protected cultural monuments or newly-discovered cultural monuments under investigation;

• clarification of property rights over newly discovered antiquities found outside state protected cultural monuments or newly-discovered cultural monuments under investigation.

5. Despite the progress made in recent years, treasure hunting is still one of the significant threats to archaeological sites in Latvia. As best practice examples (e.g., in Grobiņa) show, the involvement of the local community in the protection of sites and the provision of information on suspicious activities is one of the key elements in preventing and combating this threat.

Recommendation: raising awareness of the local community (regarding inter alia the significance and vulnerability of archaeological heritage) and involvement of local inhabitants in enjoyment, popularization and protection of archaeological sites should be promoted at the highest possible level.

6. Scientific research, publication of its results and accessibility to the local community play an essential role in the development of the socio-economic potential of archaeological sites. At present, there are certain gaps in the awareness of municipalities and private owners of archaeological sites about the role and importance of scientific research, the mechanism for engaging archaeologists in conducting research, as well as higher education in archaeology and the (insufficient) number of practicing archaeologists.

Recommendation: explaining the practical significance of scientific research, arranging a mechanism for cooperation between owners of archaeological sites (private and public) and archaeologists, and increasing the educational/training opportunities for archaeologists should become a part of public policy. Important role in fulfilling this task have NGOs (including LSA) and higher education institutions, as well as the Ministry of Culture and the NHB. Best practice examples show that when developing the potential of the archaeological heritage on the particular territory, it is useful to focus on certain periods of time and objects. Archaeological objects are often associated with significant historical events or personalities – it is important to rely on the results of scientific research to make such links.

7. The most important factor in promoting the development of archaeological objects is the public interest in them and the understanding of their significance.

Recommendation: development of intellectual society and ensuring appropriate education in the field of cultural heritage (already from school) as well as development of feelings of respect for cultural heritage from early childhood (e.g., in the family) is a necessary precondition for gaining public understanding and interest. Such development must become a priority of public policy in the field of culture, involving cultural and educational institutions, the NGOs, as well as religious and other organizations.

Research limitations and future research directions

The conducted research has several limitations that should be taken into account. The first is presented by insufficient prior research studies on the topic of development of the socio-economic potential of archaeological sites in Latvia. Thus, current research seeks to cover a large number of related aspects and, therefore, cannot provide a sufficient level of detail in each of the aspects. The other limitation is related to the insufficient number of interviews held with private owners of archaeological heritage sites – in Latvia there is no association uniting them and no organization representing their interests at the central level. At the same time, this is also a recommendation from the authors of the research to establish an association of owners of archaeological sites in Latvia, both to represent their interests and to promote more effective cooperation with other stakeholders.

Future research directions would be related to the more detailed study of the best practice examples, as well as case studies of untapped opportunities in order to provide practical recommendations in the field of the socio-economic development of the archaeological heritage objects.

Bibliography

Burtenshaw P. 2014, Mind the Gap: Cultural and Economic Values in Archaeology, Public Archaeology, Vol.13 Nos 1–3, pp. 48–58

Brodie, N. (2010). Archaeological Looting and Economic Justice. In P. M. Messenger and G. S. Smith (Eds.), Cultural Heritage Management: A Global Perspective, p. 261–277. Internet access: DOI: https://doi.org/10.5744/florida/9780813034607.001.0001 [accessed: 2021 17 October]

Gould P.G. & Burtenshaw P., 2014, Archaeology and Economic Development, Public Archaeology, 13:1–3, 3–9, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1179/1465518714Z.00000000075

Grutups A., Kalnins E., 2002. Civillikuma komentāri. Trešā daļa. Lietu tiesības. Īpašums. Otrais papildinātais izdevums. Rīga: Tiesu namu aģentūra, pp.353

Jovanovic S., Ilic I., 2016. «Infrastructure As Important Determinant Of Tourism Development In The Countries Of Southeast Europe,» EcoForum, «Stefan cel Mare» University of Suceava, Romania, Faculty of Economics and Public Administration – Economy, Business Administration and Tourism Department., vol. 5(1), pages 1–34

Kairiss, A., 2020, Latvijas arheoloģiskā mantojuma aizsardzības un sociāli ekonomiskās attīstības faktori. LZA Vēstis A daļa, 2020.g. 74.sējums 3. numurs, pp.52–79. Internet access: http://www.lasproceedings.lv/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/5_Andris-Kairiss.pdf [accessed 2021 13 October]

Kairiss, A., Olevska, I., 2020. Damage to Archaeological Sites: Assessment Criteria and Situation in Latvia. Baltic Journal of Real Estate Economics and Construction Management 8, 45–82. Internet access: https://doi.org/10.2478/bjreecm-2020-0005 [accessed 2021 13 October]

Kairiss, A., Olevska, I., 2021, Development aspects of manors as a part of cultural heritage in Latvia, Culture Crossroads, vol. 19 (2021), 153–185. Internet access: http://www.culturecrossroads.lv/pdf/333/en

Kairiss, A., Olevska, I., 2021 (1), Evaluación del riesgo del patrimonio arqueológico en Letonia: marco jurídico y aspectos socioeconómicos, in a book ¿CUÁNTO VALEN LOS PLATOS ROTOS? Teoría y práctica de la valoración de bienes arqueológicos, Ana Yáñez Ignacio Rodríguez Temiño (eds.) JAS Arqueologia, 2021, ISBN: 978-84-16725-33-5

Karnīte, R., 2002. Kultūras pieminekļu īpašnieku attieksme pret kultūras pieminekļu statusu kā apgrūtinājumu, Research commissioned by Public Administration Institution, Institute of Economics of the Latvian Academy of Sciences. Internet access: https://www.km.gov.lv/sites/km/files/kulturas_piemineklu_statuss_lza_ei1.pdf [accessed 2021 13 October]

Król, K., 2021. Assessment of the Cultural Heritage Potential in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126637

Muzichuk V.J., 2017, Sohranenie kulturnogo nasledija v kontekste socialjno-ekonomicheskogo razvitija Rossii, Vestnik Instituta ekonomiki Rossijskoj akademii nauk 2/2017, pp.8–31

Teutonico, J. M., Gaetano P., eds. 2002. Management Planning for Archaeological Sites: An International Workshop Organized by the Getty Conservation Institute and Loyola Marymount University, 19–22 May 2000, Corinth, Greece. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. Internet access: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/gci_pubs/planning_arch_sites [accessed 2021 13 October]

Throsby, D. 2019. ‘Heritage Economics: Coming to Terms with Value and Valuation’. In Values in Heritage Management: Emerging Approaches and Research Directions, by Erica Avrami, Susan MacDonald, Randall Mason, and David Myers, 199–209. Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Conservation Institute

Official and mass media information

Aluksnesnovads 2014 – „Arheoloģija, vara un sabiedrība: sadarbība arheoloģiskā mantojuma saglabāšanai”, Uzsākta pārrobežu projekta īstenošana, Internet access: https://aluksne.lv/projekti/realizacija_esosie_projekti/018.htm [accessed 2021 13 October]

CIfA 2021, Professional archaeology: a guide for clients, Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, Internet access: https://www.archaeologists.net/sites/default/files/CIfA21_FINAL_72dpi.pdf [accessed 2021 13 October]

Diena 2021, Pilskalnu sprādziens, 27.02.2021. Internet access: https://www.diena.lv/raksts/sestdiena/sestdienas-salons/pilskalnu-spradziens-14257695 [accessed 2021 13 October]

EST-LV cross-border co-operation program 2011 – Estonian–Latvian cross-border co-operation program project “Unknown cultural heritage values in common natural and cultural space”, Internet access: https://www.zm.gov.lv/public/ck/files/Apsaimniekosanas_rekomendacijas.xls [accessed 2021 13 October]