Ekonomika ISSN 1392-1258 eISSN 2424-6166

2025, vol. 104(3), pp. 142–159 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2025.104.3.8

Elvira Caka

University of Prishtina, Prishtina, Kosovo

E-mail: elviracakaa@gmail.com

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-7862-8614

Juliana Imeraj

University “Aleksander Moisiu”, Durres, Albania

E-mail: julianaimeraj@uamd.edu.al

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5284-1460

Gjon Gjonlleshaj

South East European University, North Macedonia

E-mail: gg30459@seeu.edu.mk

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-9958-6007

Vlora Prenaj*

University of Prishtina, Prishtina, Kosovo

E-mail: vlora.prenaj@uni-pr.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5679-4829

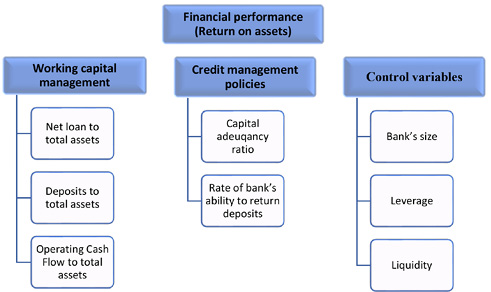

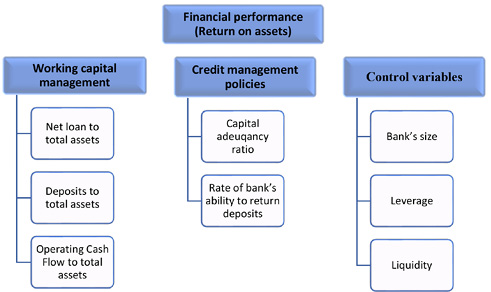

Abstract. The purpose of the study is to examine the impact of working capital management and credit management policies on the financial performance of banks in Kosovo. It is based on panel data obtained from the financial statements of commercial banks for the period of 2013–2022. The data is analyzed using fixed effect and random effect models with the best-fitting model chosen based on the Hausman test result. The dependent variable is ROA, as an indicator of performance, while net loans to total assets, deposits to total assets, operating cash flows to total assets, capital adequacy ratio, and the ratio of a bank’s ability to return deposits are independent variables used to measure the working capital management and credit management policies of banks. Meanwhile, the bank size, leverage, and liquidity are control variables. The study has revealed a positive correlation between working capital management and the financial performance of banks, except for the variables net loan to total assets, bank size, and leverage. In addition, credit management policy has a positive relationship with banks’ return on assets, with the capital adequacy ratio, the ratio of a bank’s ability to return deposits, and liquidity being statistically significant variables.

The study’s findings assess how working capital management and credit management policies impact the financial performance of banks in Kosovo. It is a new effort which tries to make the importance of working capital management and credit management policies more luciferous. Banks should manage working capital with proper planning and adequate controls.

Keywords: Credit control, profitability, banking, public policies.

_______

* Correspondent author.

Received: 29/10/2024. Revised: 24/04/2025. Accepted: 26/05/2025

Copyright © 2025 Elvira Caka, Juliana Imeraj, Gjon Gjonlleshaj, Vlora Prenaj. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The finance sector’s performance is the primary determinant of a country’s economic success. Banks are considered the vital intermediaries in a market-oriented economy and are considered the key to investment and growth (Maharjan, 2023). The bank’s asset and liability management are primarily influenced by the principles of working capital management (WCM) (Abuhommous, Alsaraireh, & Alqaralleh, 2022). Working capital management aims to maintain the ideal balance between each working capital component. WCM is the process of organizing and managing a company’s ongoing operations and financing them. Managing working capital correctly and efficiently is crucial for increasing profitability (Ahmeti & Balaj, 2023).

There is a positive and statistically significant relationship between all components of working capital and profitability, showing that an increase in each variable considered determines an improvement in performance in terms of ROA and ROE (Alvarez, Sensini, & Vazquez, 2021).

Credit management is required for a financial institution’s stability and long-term profitability, whereas declining credit quality is the most common cause of bad financial performance and condition (Kagoyire & Shukla, 2016). The authors emphasize that strong credit management is crucial for the stability and ongoing profitability of a financial institution. In contrast, the deterioration of credit quality is the most common cause of poor performance and financial instability (Kagoyire & Shukla, 2016). To enhance financial performance, according to (Olabamiji & Michae, 2018), bank management is advised to implement stricter regulations, improve client appraisal methods, and strengthen the credit risk control.

Every management team wants to maximize profits while minimizing non-performing loans and maximizing sales in the shortest amount of time. Business owners and credit policy managers know that, in order to achieve this objective, customers must also be able to pay and satisfy financial commitments on time to ensure future growth of the business. As companies face strong competition, some sales will inevitably be made to doubtful customers. Therefore, credit policy management requires good credit control routines as well as systems for monitoring accounts and procedures.

The most important objective of this study is to determine the impact of WCM and CMP on the FP of banks. The specific objectives that are related to the main object of this research are:

• What impact does WCM have on banks’ financial results?

• What is the impact of credit management policy on banks’ financial performance?

• What role does an appropriate WCM have in banks’ performance?

• What strategies should be used to ensure useful credit management policies?

The findings depict a significant effect of Kosovo’s banks’ performance and the capital management, except for net loans to total assets (NLTA), bank size (SIZE), and leverage (LEV), which have a negative relationship with ROA. Meanwhile, deposits to total assets (DTA) and operating cash flow to total assets (OCA) have a positive relationship in determining ROA. In addition, credit management policy has a positive relationship with banks’ ROA, with CAR, RBARD, and CuR being statistically significant variables.

The paper is divided into five sections, including a literature review in Section Two, followed by a section on methodology (Section Three), results, and discussion in Section Four, and research limitations, conclusion and recommendations in the final part.

Working capital management is a discipline of management that applies to all spheres of life, from households and businesses to the public and private sectors of production and service. Working capital is a topic that is frequently addressed and occasionally misunderstood. Confusing and contentious situations continue, even among experienced managers. Current assets are defined by financial management as gross working capital, whereas working capital is calculated by subtracting current liabilities (Bhattacharya, 2021). Though their perspectives are different, each may be true. The former takes only arithmetic factors into account when calculating the balance sheet’s two sides, whereas the financial manager considers developing a balanced financial structure by determining the necessary funds for each current asset item with the associated costs and risks. Suppose a production controller is asked, “What is working capital?” Their response is clear-cut and simple (Bhattacharya, 2021). They will explain that it is the money required to pay for supplies, payroll, and other running costs to meet daily labor expenses. Do the financial statements of the production controller, financial manager, and accountant differ from one another? In the final analysis, the latter might be accurate, but the accountant or financial manager claims that labor costs are what is locked into current assets along an organization’s production-distribution line, and the net working capital is the liquidity that covers operating costs if the line is extended for any reason (Bhattacharya, 2021).

Firm-specific factors the like size, age, profitability, market share, sales growth, operating risk, and operating cash flow dictate WCM endogenously. In contrast, macroeconomic variables such as GDP, interest rates, and tax rates are exogenous drivers. Because of having inventory, current assets, and cash, the main purpose of WCM is to produce the highest degree of liquidity and profitability. The ideal stage of working capital enhances the company’s worth, which involves a trade-off between liquidity and profitability. Excessive investment in working capital can negatively impact a company’s profitability by tying up resources that could otherwise be deployed more productively, thereby resulting in opportunity costs (Anake, Ugwu, & Takon, 2015). This underscores the importance of effective working capital management as a strategic financial decision. A critical component of such management is the company’s credit policy, which plays a central role in determining how the credit line is extended to customers. A well-defined credit policy provides a consistent framework for making credit decisions that align with broader financial objectives (Pike & Cheng, 2001). Taken together, these perspectives emphasize the balance which firms must strike between maintaining liquidity and ensuring profitability. While Anake et al. (2015) caution against over-investment in working capital, Pike and Cheng (2001) highlight the necessity of structured decision-making through sound credit policies. This suggests that firms can mitigate the risks associated with excessive working capital by implementing disciplined credit strategies that support the cash flow and enhance the overall financial stability. Therefore, aligning the credit policy with the working capital objectives is not merely a procedural formality but a strategic imperative.

The credit policy demands regular evaluation and accurate documentation, it entails selecting an organizational design for credit management or market-based lending activities (Pike & Cheng, 2001). The strategic push toward focusing on business strengths and outsourcing non-core activities has forced many firms to reconsider the role of credit and the management function, including the extent to which credit and credit activities should be subcontracted to financial intermediaries such as factoring, credit insurers, debt collectors, and information providers (Pike & Cheng, 2001). No matter the type of business, credit management is one of the most crucial tasks for any organization, which cannot be disregarded by any credit-related business. The most common reason for bad financial performance and condition is a declining credit quality, but sound credit management is necessary for a financial institution to remain stable and profitable (Gatuhu, 2013).

A crucial component for efficient credit management is the capacity to make informed decisions and skillfully oversee client lines of credit (Kagoyire & Shukla, 2016). To reduce exposure to non-performing loans, excess reserves, and bankruptcies, businesses must have more knowledge about the financial strength, credit score, and payment history of their clients. The sale marks the start of credit management, which continues until the last and complete payment has been received (Kagoyire & Shukla, 2016).

Since a sale is not considered complete until the money has been received, completing the sale is equally as important as closing the agreement. Therefore, the essentials of lending should be taken into account in order to ensure that the lender is able to make the scheduled payments, including full interest, within the required time frame. Non-performing loans (NPLs), which arise when borrowers fail to repay their debts, directly reduce or eliminate the profit that financial institutions expect to earn from interest income (Kagoyire & Shukla, 2016). This not only undermines revenue but also introduces risks that can destabilize financial performance. As (Fatihudin, 2018) explains, financial performance is a comprehensive measure of a company’s financial outcomes over time, shaped by indicators such as profitability, efficiency, solvency, and liquidity. By integrating these perspectives, it becomes evident that the occurrence of non-performing loans significantly affects key dimensions of financial performance. For instance, high levels of NPLs reduce profitability and strain liquidity, potentially threatening the firm’s solvency and capital adequacy. This underscores the importance of effective credit risk management in maintaining robust financial performance. Therefore, beyond being a technical accounting issue, NPLs represent a critical financial management concern that can impair an institution’s overall financial health if not properly addressed.

The capacity of the business to effectively manage and control its resources is referred to as financial performance. Corporate managers can use cash flow, balance sheets, profit-loss, and modify capital as the foundation for their decision-making. Understanding technical and basic analysis is crucial.

Financial and social stability, the advancement of trade and production, and the stimulation of economic growth depend on the existence and longevity of stable financial institutions. Assessing the profitability of financial institutions is the highest priority in the dynamic financial sector and is constantly changing. Profitability is a critical indicator of an institution’s overall financial health, reflecting its ability to remain competitive and generate sustainable returns over time (Mahmudova, 2023). However, profitability is just one component of broader financial performance. As (Abisola, 2022) notes, financial performance encompasses a wider set of measurements, representing the outcomes of a company’s policies and operations in financial terms. Taken together, these definitions highlight that while profitability is essential, it should be considered within the broader context of financial performance, which includes multiple dimensions such as efficiency, liquidity, and solvency. This suggests that evaluation of an institution solely based on profit may overlook other vital indicators that contribute to long-term sustainability. Therefore, a more comprehensive assessment of financial performance is necessary, particularly in sectors where strategic financial management plays a crucial role in operational success.

Since the income statement displays the business’s working success and the balance sheet displays its net worth, both are crucial documents for evaluating a company’s overall financial health. There are two ways to evaluate financial performance: descriptive and analytical. While analytical metrics may include profitability, efficiency, liquidity, and solvency ratios, descriptive metrics include total assets, total debts, shareholders’ equity, total revenues, total expenses, and net income (Adam, 2014).

Empirical data on the impact of WCM and CMP on FP is sometimes contradictory. Different studies have used different financial frameworks and measures of bank performance, while results tend to vary between studies.

In this research, we will assess WCM and credit management policies over 10 years (2013–2022) of commercial banks operating in Kosovo. For the period under analysis, secondary data were gathered from the banks’ annual reports and financial statements, particularly the income statement and the statement of financial position. Quantitative research methods deal with the collection and processing of data that are structured and can be presented in numerical form. Random effect (RE) and fixed effect (FE) models were used to analyze the data, and the Hausman test served to choose the best-fit model. To deliver the results and to obtain the conclusions of this paper, these data were processed through the statistical software package STATA. Random effect (RE) and fixed effect (FE) were used as developed in a number of earlier scholarly papers, such as (Prenaj, Miftari, & Pula, 2024), (Derbali, 2021), and (Desai, 2021).

|

Indications |

Variables |

Calculation |

Authors |

|

Financial performance |

ROA (Return on assets) |

Net income/total assets |

(Căpraru & Ihnatov, 2014); (Sujud & Hashem, 2017); (Prenaj, Imeraj, & Smajli, 2023); (Serhii, Yuliia, Tetiana, Zuzana, & Alena, 2023) |

|

Working Capital Management |

NLTA (Net loan to total assets) |

Net loan/total assets |

(Sun, Mohamad, & Ariff, 2017); (Romli, et al., 2022); (Péran & Sdiri, 2024) |

|

DTA (Deposits to total assets) |

Deposits/total assets |

(Lee, Hsieh, & Yang, 2014); (Adesina, 2020) |

|

|

OCA (Operating Cash Flow to total assets) |

Operating Cash Flow/total assets |

(Dao, Ho, Le, & Duong, 2021); (Banyen & Biekpe, 2021) |

|

|

CAR (Capital adequacy ratio) |

The bank’s total capital/risk-weighted assets |

(Cebenoyan & Strahan, 2004); (Ghosh, 2018) |

|

|

Credit Management Policy |

RBARD (Rate of bank’s ability to return deposits) |

Rate of bank’s ability to return deposits as measured by the ratio of Equity/deposits |

(AL-Zararee, Almasria, & Alawaqleh, 2021); (Maharjan, 2023) |

|

Control variables |

SIZE (Bank’s size) |

Natural Log of Total Assets |

(Bidari & Djajadikerta, 2020); (Prenaj, Miftari, & Krasniqi, 2023) |

|

LEV (Leverage) |

Total liability/Total assets |

(Poh, Kilicman, & Ibrahim, 2018); (Munangi, 2020); (Chen, 2020) |

|

|

CuR (Liquidity) |

Current assets/current liability |

(Godswill, Ailemen, Osabohien, Chisom, & Pascal, 2018); (Albertus & Mangunsong, 2021) |

The working model is based on the dependent variable (ROA), the independent variables (NLTA), (DTA), (OCA), (CAR), as well as (RBARD), and the control variables (SIZE), (LEV), and (CuR) with the objective to examine the impact of WCM and CMP on banks’ performance.

The statistical model used for this study is as follows:

ROA i,t = β0 + β1 NLTAi,t + β2 DTA i,t + β3 OCA i,t + β4 CAR i,t + β5 RBARD i,t +

β6 SIZE i,t + β7 LEV i,t + β8 CuR i,t + ε i,t (1)

Where:

ROA i,t – Return on assets for Kosovar banki timet

NLTAi,t – Net loan to total assets for Kosovar banki timet

DTA i,t – Deposits to total assets for Kosovar banki timet

OCA i,t – Operating cash flow to total assets for Kosovar banki timet

CAR i,t – Capital adequacy ratio for Kosovar banki timet

RBARD i,t – Rate of bank’s ability to return deposits for Kosovar banki timet

SIZE i,t – Bank’s size for Kosovar banki timet

LEV i,t – Leverage for Kosovar banki timet

CuR i,t – Current assets for Kosovar banki timet

βi – The coefficient of each independent variable

Ɛ i,t – Error Terms for banki timet

Statistical analysis methods help us calculate and interpret the statistics we need. Descriptive statistics for the independent and dependent variables are shown in Table 2.

|

Variables |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. deviation |

|

ROA |

-0.0598 |

0.1312 |

0.018 |

0.0191 |

|

NLTA |

0.11306 |

0.7994 |

0.386 |

0.2337 |

|

DTA |

0.17404 |

0.9231 |

0.827 |

0.10652 |

|

OCA |

-0.45131 |

0.1477 |

0.0215 |

0.07369 |

|

CAR |

0.0805 |

0.2885 |

0.1518 |

0.03497 |

|

RBARD |

0.0766 |

4.7281 |

0.2658 |

0.7078 |

|

SIZE |

9.3351 |

16.13 |

13.17 |

1.278 |

|

LEV |

0.177 |

0.9619 |

0.8714 |

0.09775 |

|

CUR |

0.5971 |

5.713 |

1.158 |

0.59679 |

The correlation coefficients between the variables are shown in Table 3. When two variables’ values fluctuate over a period of observations, such that when one variable’s value increases or decreases, the other variable’s value similarly increases or decreases (or even goes in the opposite way), the variables are said to be statistically connected.

|

Variables |

ROA |

NLTA |

DTA |

OCA |

CAR |

RBARD |

SIZE |

LEV |

CUR |

|

ROA |

1 |

||||||||

|

NLTA |

-0.4533** |

1 |

|||||||

|

DTA |

0.6426*** |

-0.1816 |

1 |

||||||

|

OCA |

0.3571** |

0.0259 |

-0.0441 |

1 |

|||||

|

CAR |

0.7673*** |

-0.2559 |

-0.5606 |

0.1998 |

1 |

||||

|

RBARD |

0.6187*** |

0.0616 |

-0.7346*** |

0.0727 |

0.7747 |

1 |

|||

|

SIZE |

-0.0344 |

0.3354 |

-0.1184 |

-0.0313 |

-0.1914 |

-0.0501 |

1 |

||

|

LEV |

0.0487 |

-0.2132 |

0.5462*** |

-0.0399 |

-0.651 |

-0.8283 |

-0.0211 |

1 |

|

|

CUR |

0.0562 |

0.0407 |

-0.1894 |

0.0719 |

0.2502 |

0.3734 |

-0.5524 |

-0.2746 |

1 |

Analyzing the relationship between the variables, it has been reported that the financial performance of banks represented by ROA has a strong positive relationship with DTA, CAR, and RBARD, a weak positive relationship with OCA, LEV, and CuR, and a weak negative correlation with NLTA and SIZE. Table 4 represents the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF results indicate that multicollinearity among independent variables is not a problem. All the VIF values are less than 10, which suggests that there is no substantial correlational dependency between the independent variables in the research.

|

Variable |

VIF |

1/VIF |

|

CAR |

7.23 |

0.13832 |

|

BRARD |

3.98 |

0.25102 |

|

LEV |

3.93 |

0.254143 |

|

DTA |

2.57 |

0.389106 |

|

CuR |

1.95 |

0.511716 |

|

SIZE |

1.93 |

0.517334 |

|

NLTA |

1.8 |

0.554582 |

|

OCA |

1.11 |

0.901416 |

|

Mean VIF |

3.06 |

Table 5 presents the regression model through random effects. One method for numerically categorizing which of these variables are statistically significant is regression analysis. It responds to the query, “What are the most important factors? Which factors are we able to disregard? What are the interactions between these factors? And probably most crucially, to what extent do we have confidence in each of these factors?” In regression analysis, these factors are called ‘variables’ (Gallo, 2015).

|

ROA |

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

z |

p>|z| |

|

NLTA |

-0.0845 |

0.094 |

-1.289 |

0.705 |

|

DTA |

0.0727 |

0.001 |

1.575 |

0.323 |

|

OCA |

0.0665 |

0.065 |

1.317 |

0.195 |

|

CAR |

0.0607*** |

0.030 |

3.599 |

0.007 |

|

RBARD |

0.0050*** |

0.002 |

2.103 |

0.003 |

|

SIZE |

-0.0150 |

0.028 |

-0.58 |

0.553 |

|

LEV |

-0.0001*** |

0.000 |

-15.82 |

0.001 |

|

CuR |

0.18020*** |

0.012 |

2.502 |

0.004 |

|

R-squared |

0.4540 |

The model’s R-squared is 0.4540, meaning that 45 percent of the variance of ROA as a dependent variable is thought to be accounted for by the independent variables. The model demonstrates that the capital adequacy ratio is one of the factors that significantly affects banks’ financial performance (CAR), the rate of a bank’s ability to return deposits (RBARD), leverage (LEV), and the current ratio (Cur).

Interpretation of variables, ceteris paribus, is defined as follows:

- ROA will typically decrease by 0.0845 for every 1% increase in NLTA.

- ROA will typically rise by 0.0727 for every unit increase in DTA.

- If OCA increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase by 0.0665 on average.

- If CAR increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase on average by 0.0607.

- If RBARB increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase by 0.0050 on average.

- If SIZE increases by 1 percent, then ROA will decrease by 0.0150 on average.

- If LEV increases by 1 percent, then ROA will decrease by 0.0001 on average.

- If CuR increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase by 0.18020 on average.

Table 6 presents the regression model through Fixed Effect.

|

ROA |

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

t |

p>|t| |

|

NLTA |

-0.0261 |

0.0315 |

-0.83 |

0.411 |

|

DTA |

0.0125 |

0.1101 |

1.14 |

0.257 |

|

OCA |

0.0211 |

0.0387 |

0.55 |

0.588 |

|

CAR |

0.0196*** |

0.1254 |

4.57 |

0.010 |

|

RBARD |

0.0115*** |

0.1884 |

3.86 |

0.0039 |

|

SIZE |

-0.0615 |

0.0053 |

-1.15 |

0.0251 |

|

LEV |

-0.1497*** |

0.1497 |

-13.29 |

0.0032 |

|

CuR |

0.0011** |

0.0156 |

2.07 |

0.0444 |

|

R-squared |

0.4871 |

The model’s R-squared is 0.4871, meaning that 48.71% of the variance of ROA as the dependent factor can be understood and explained by the independent variables. While not exceedingly high, this suggests a moderate explanatory power.

All variables are included in this model to determine the most significant variables that affect ROA. The model demonstrates that the CAR, RBARD, leverage, and liquidity are the factors that significantly impact banks’ financial performance.

Interpretation of variables, ceteris paribus, is suggested as follows:

- In the case that NLTA increases by 1%, ROA is going to decrease by 0.0261.

- ROA usually increases by 0.0125 for every unit increase in DTA.

- If OCA increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase on average by 0.0211.

- If CAR increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase on average by 0.0196.

- If RBARB increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase by 0.0115 on average.

- If SIZE increases by 1 percent, then ROA will decrease by 0.0615 on average.

- If LEV increases by 1 percent, then ROA will decrease by 0.1497 on average.

- If CuR increases by 1 percent, then ROA will increase by 0.0011 on average.

|

Hypothesis |

The p value for the Haussmann test |

Best-fitted model |

|

|

H0: Fitted RE model |

H1: Fitted FE model |

0.4514 |

H1: Fitted FE model |

The most appropriate model for achieving the objectives of this research according to the Hausman test, turns out to be the fixed effect (see Table 7), so we can interpret the results according to this model. Based on the fixed effect results outlined in Table 6, we can conclude that, between working capital management and the financial performance of banks in Kosovo, there is a mostly positive relationship, excluding NLTA, SIZE, and LEV, as their coefficients are negative in determining ROA, with LEV being a statistically significant variable.

NLTA is not statistically significant in influencing ROA. This suggests that non-performing loans may have a delayed impact on the bank’s profitability, and that their effect could be contingent on other factors. The same results are found in the study (Lardic & Terraza, 2019), where credit risk measured by NLTA is negatively related to ROA. This shows that banking system managers, as well as cooperative banks, seem to have adopted a risk-averse strategy, mainly through policies that improve screening and monitoring credit risk. The coefficient for SIZE is -0.0615, which means that larger banks tend to have lower ROA. This could be due to several factors, such as inefficiencies associated with scaling up operations or higher costs related to managing a large institution. As for the SIZE coefficient, we find contrary results in different studies. According to (Priharta & Gani, 2024), SIZE has a significant positive effect on ROA. Meanwhile, a negative relationship is explained as an increased size leads to inefficiency and lower performance (Hoti, Hoti, & Berisha, 2024). We have a negative relationship between LEV and ROA. More leverage significantly reduces ROA. This is consistent with the idea that high leverage increases financial risk, which can diminish profitability due to higher interest expenses and a potential for financial distress. Regarding the relationship between LEV and ROA, the study by Munangi (2020) documented that bank leverage and ROA were negatively related. However, the results of Rahim et al. (2021) research showed the significant and positive impact of leverage on banks. Banks with significant levels of financial leverage are well-positioned to benefit financially from tax revenue or from bearing the high cost of debt in terms of interest that lowers profit (Rahim, et al., 2021).

The model’s results show that DTA and OCA have a positive effect in determining ROA. DTA does not have a significant impact on ROA, suggesting that the percentage of deposits to total assets does not have a direct effect on bank profitability. Santoso et al. (2021), also conclude the positive relationship between DTA and ROA. Additionally, OCA has no apparent impact on ROA, operational cash flow as a percentage of total assets has no direct impact on bank profitability. In turn, OCA is a statistically significant variable in determining working capital requirements in research (Silva, Camargos, Fonseca, & Iquiapaza, 2019). According to their findings, companies with a greater operational cash flow (OCA) typically have shorter financial cycles.

The other variables, CAR, RBARD, and CuR, are statistically significant determinants of ROA and have a positive correlation with it. An increase in the CAR value is associated with an improvement in ROA, because banks with sufficient capital are more stable and can operate more efficiently, thereby improving profits. A positive relationship between CAR and ROA was determined by (Cebenoyan & Strahan, 2004). Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) also affects the financial performance of banks in Nigeria, according to (Mshelia & Polycarp, 2024). It was equally unveiled that networking capital has no significant effect on the financial performance of banks in Nigeria (Mshelia & Polycarp, 2024).

The positive relationship between RBARD and ROA suggests that an increase in a bank’s ability to return deposits is associated with an increase in ROA. Banks that are more successful in managing and returning deposits could generate more profits. Risk management innovations are positive and might make bank loans more accessible, but researchers suggest that regulators should not expect banks to employ these technologies to lower the risk (Cebenoyan & Strahan, 2004). Also, Al-Zararee, Almasria, & Alawaqleh (2021), in their research, found that RBARD has a positive correlation with the financial performance of a bank.

The positive correlation between ROA and CuR suggests that an increase in ROA is associated with an increase in current assets. This finding implies that banks with higher liquidity tend to be more profitable because they can take advantage of quicker and safer investment opportunities due to having more readily accessible assets. Regarding the statistically significant and positive correlation between them, (Demirgüneş, 2016) obtained similar results. Liquidity is one influential factor in determining the return on assets (Oli, 2021).

Table 8 presents the normality of the variables included in the study. The Shapiro-Wilk test evaluates whether the data for each variable follows a normal distribution. According to the test criteria, a p-value greater than 0.05 indicates that the data do not significantly deviate from a normal distribution, while a p-value below 0.05 suggests a violation of normality.

|

Variable |

W-statistic |

p-value |

Interpretation |

|

ROA |

0.6362 |

1.62E-12 |

Not normal |

|

NLTA |

0.8263 |

5.08E-08 |

Not normal |

|

DTA |

0.5204 |

1.86E-14 |

Not normal |

|

OCA |

0.7297 |

1.33E-10 |

Not normal |

|

CAR |

0.843 |

0.069 |

Normal |

|

RBARD |

0.830 |

0.063 |

Normal |

|

SIZE |

0.5418 |

3.97E-14 |

Not normal |

|

LEV |

0.939 |

0.071 |

Normal |

|

CUR |

0.821 |

0.062 |

Normal |

The results indicate that ROA, NLTA, DTA, OCA, and SIZE all have p-values well below the 0.05 threshold, indicating that their distributions are significantly non-normal. Conversely, the variables CAR, RBARD, LEV, and CUR display p-values above 0.05. This suggests that the data for these variables are approximately normally distributed and suitable for parametric tests.

The Wooldridge test is used to detect autocorrelation in panel data. Autocorrelation occurs when the residuals from a regression model are correlated over time for the same entity.

Test Outcome: p-value = 0.0428.

Since p < 0.05 was established, we reject the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation. The null hypothesis of the Wooldridge test is that there is no autocorrelation in the residuals of the panel data, and this hypothesis can be rejected. There is significant evidence of autocorrelation in the residuals of the model, which means that the errors are correlated over time for the same entity.

Table 9 presents the Durbin-Wu-Hausman test values.

|

Variable |

Coefficient (OLS) |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

p-Value |

Coefficient (2SLS) |

Std. Error (2SLS) |

t-Statistic (2SLS) |

p-Value (2SLS) |

|

const |

-0.08 |

0.06 |

-1.51 |

0.14 |

0.03 |

0.10 |

0.31 |

0.76 |

|

NLTA |

0.01 |

0.01 |

1.06 |

0.29 |

-0.03 |

0.04 |

-0.62 |

0.54 |

|

DTA |

0.11 |

0.06 |

1.95 |

0.06 |

-0.01 |

0.09 |

-0.12 |

0.91 |

|

OCA |

-0.05 |

0.04 |

-1.34 |

0.19 |

0.07 |

0.40 |

0.18 |

0.86 |

|

CuR |

0.01 |

0.10 |

0.10 |

0.92 |

-0.03 |

0.36 |

-0.07 |

0.94 |

|

RBARD |

0.07 |

0.09 |

0.78 |

0.44 |

0.07 |

0.20 |

0.34 |

0.74 |

Based on the results of the DWH test, there is no strong evidence of endogeneity in the model. As such, the OLS estimates are considered consistent and unbiased and can be used for further interpretation and policy implications. This outcome suggests that while the selected variables (e.g., NLTA, DTA, etc.) were theoretically suspected to be endogenous, the available instruments and model structure do not indicate a practical endogeneity bias in this context.

Furthermore, in this paper we have conducted more tests representing the values of the significant importance of our analysis.

Breusch-Pagan for heteroscedasticity:

LM Statistic: 5.28: Since the p-value (0.383) is greater than 0.05, we fail to reject the null hypothesis of homoscedasticity. p-value: 0.383: There is no evidence of heteroscedasticity in our model. The residuals appear to have constant variance, which means that our OLS estimates are efficient and the standard errors are reliable.

F-statistic: 1.05

F p-value: 0.399

This is a robust standard error panel data regression.

|

ROA |

Coef. |

St.Err. |

t-value |

p-value |

[95% Conf |

Interval] |

Sig |

|

NLTA |

-.005 |

.02 |

-0.24 |

.818 |

-.051 |

.042 |

|

|

DTA |

.069 |

.085 |

0.81 |

.442 |

-.132 |

.271 |

|

|

OCA |

-.04 |

.053 |

-0.75 |

.479 |

-.166 |

.086 |

|

|

ERRA |

-.133 |

.062 |

-2.12 |

.071 |

-.28 |

.015 |

* |

|

RBARD |

.057 |

.143 |

0.40 |

.701 |

-.281 |

.396 |

|

|

SIZE |

0 |

0 |

-2.38 |

.049 |

0 |

0 |

** |

|

LEV |

-.129 |

.118 |

-1.09 |

.31 |

-.409 |

.15 |

|

|

CuR |

.005 |

.004 |

1.08 |

.315 |

-.006 |

.015 |

|

|

Constant |

.089 |

.184 |

0.48 |

.645 |

-.346 |

.524 |

|

|

Mean dependent var |

0.021 |

SD dependent var |

0.015 |

||||

|

R-squared |

0.074 |

Number of obs |

74 |

||||

|

F-test |

. |

Prob > F |

. |

||||

|

Akaike crit. (AIC) |

-415.580 |

Bayesian crit. (BIC) |

-399.452 |

||||

This principle is used when the model involves multicollinearity, endogeneity, heteroscedasticity, and non-normality. This way, we can solve all these problems that have occurred in our previous model results

To include a broad sample of banks and ensure a relatively long study period of 10 years, we encountered several challenges in accessing the necessary data during this research on banks in Kosovo. One significant difficulty arose during the data collection phase, as some banks did not provide complete access to their financial reports for the selected years. In general, larger banks with a longer presence in the Kosovo banking market provided comprehensive data, which greatly facilitated our ability to gather the necessary information for accurate analysis. Conversely, smaller banks exhibited data gaps, with some annual financial reports missing for several years, which were essential for the completion of our study. As a result, the number of observations is lower than it would have been had the complete data been available for all the banks included in the research.

The purpose of this research was to investigate how working capital and credit management practices affected Kosovo banks’ financial results between 2013 and 2022. A panel of data, including 80 observations from commercial banks based in Kosovo, served as the basis for the study.

With the exception of the variables net loans to total assets (NLTA), bank size (SIZE), and leverage (LEV), which increase in tandem with a decline in return on assets (ROA) of the banks in Kosovo, the study found a generally positive relationship between WCM and the financial performance of banks in Kosovo, while other WCM variables had a positive relationship with the financial performance of banks in Kosovo.

Regarding the credit management policy and the impact of its variables on the financial performance of banks, the study shows that a positive relationship is observed. Variables, Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), Bank’s Ability to Return Deposits Rate (RBARD), and Liquidity (CuR) are statistically significant to the financial performance of banks ROA, while the rest of the variables are not statistically significant to the financial performance of banks in Kosovo.

Considering the results of this study and taking note of the purpose and focus of this paper, we complete this study by giving some recommendations. This study will help banks determine their working capital and the factors that influence it, as well as the policies that banks use to manage their loans.

On the grounds of understanding the activity of banks and in line with their general objectives, we also recognize the need of banks for the factor called liquidity. Banks must pay great attention to liquidity to provide security for their customers. This study showed that management should take measures to shorten the average collection period of its debtors as a strategy for improving credit management policies, in addition to contributing to the increase of banks’ liquidity.

Managing working capital adequately is a core task of bank management, and we recommend that banks take care by establishing proper planning and adequate controls since working capital is one of the most important parts of banks’ activity. The worsening financial position of banks in Kosovo could be a significant justification, as effective working capital management may play a role in improving such conditions.

With reference to total loans to total assets, banks are advised to keep a manageable number of loans to total assets so that banks could keep the value of loans under control. By implementing effective preparation and controls to assist them in monitoring their daily operations, banks may better manage their working capital to boost performance and maximize shareholder wealth.

Banks should incorporate effective risk management strategies to improve working capital management, while addressing risks such as credit, interest rate, and market volatility, which can substantially affect liquidity and financial stability.

The implementation of advanced technological instruments, including digitalization and data analytics, is essential for enhancing financial forecasts, cash flow management, and the overall liquidity oversight.

Moreover, investing in employee training and development, especially in financial management and credit analysis, will enable personnel to make educated decisions and improve financial controls. Additionally, banks should concentrate on diversifying their loan portfolios to reduce risks and guarantee stability in times of economic depression. Finding inefficiencies, ensuring compliance, and preserving flexibility in a changing market all depend on routine financial audits and evaluations of working capital and loan management plans.

Lastly, banks will be able to find a balance between long-term stability and profitability by implementing policies that support sustainable growth, while guaranteeing continued success without risking liquidity or financial health.

Abisola, A. (2022). The nexus between bank size and financial performance: Does internal control adequacy matter? Journal of Accounting and Taxation, 14(1), 13-20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5897/JAT2021.0501

Abuhommous, A. A., Alsaraireh, A. S., & Alqaralleh, H. (2022). The impact of working capital management on credit rating. 8(72). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-022-00376-z

Adam, M. H. (2014). Evaluating the Financial Performance of Banks using financial ratios-A case study of Erbil Bank for Investment and Finance. European Journal of Accounting Auditing and Finance Research, 2(6), 162-177. Retrieved from http://www.ea-journals.org/

Adesina, K. S. (2020). How diversification affects bank performance: The role of human capital. Economic Modelling, 94, 303-319. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.10.016

Ahmeti, A., & Balaj, D. (2023). Influence of Working Capital Management on the SME’s Profitability-Evidence from Kosovo. Calitatea, 24(192), 154-162. doi:10.47750/QAS/24.192.18

Albertus, R. H., & Mangunsong, H. L. (2021). The effect of current ratio, total assets turnover and earnings per share on stock prices in banking sub-sectors listed on the Indonesia Atock Exchange 2018-2019. Strategic Management Business Journal, 1-10. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.55751/smbj.v1i02.19

Alvarez, T., Sensini, L., & Vazquez, M. (2021). Working capital management and profitability: Evidence from an emergent economy. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, 32-39. https://www.iris.unisa.it/handle/11386/4759950

AL-Zararee, A., Almasria, N. A., & Alawaqleh, Q. A. (2021). The effect of working capital management and credit management policy on Jordanian banks’ financial performance”. Banks and Bank Systems, 16(4), 229-239. doi:10.21511/bbs.16(4).2021.19

Anake, F., Ugwu, J., & Takon, S. (2015). Determinants of working capital management theoretical review. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 3(2), 1-11. Retrieved from http://eprints.gouni.edu.ng/1360/1/fidelis%20james%20takon.pdf

Banyen, K., & Biekpe, N. (2021). Financial integration and bank profitability in five regional economic communities in Africa. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 16(3), 468-491. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-08-2018-0435

Bhattacharya, H. (2021). Working capital management: Strategies and techniques. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.

Bidari, G., & Djajadikerta, H. G. (2020). Factors influencing corporate social responsibility disclosures in Nepalese banks. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 5(2). Retrieved from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/AJAR-03-2020-0013/full/html#sec003

Căpraru, B., & Ihnatov, I. (2014). Banks’ Profitability in Selected Central and Eastern European Countries. Procedia Economics and Finance, 16, 587-591. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00844-2

Cebenoyan, A. S., & Strahan, P. E. (2004). Risk management, capital structure and lending at banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 28(1), 19-43. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00391-6

Chen, Z. (2020). Promotion Incentive, Employee Satisfaction and Commercial Bank Performance. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 8(4). Retrieved from https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=99440

Dao, O. L., Ho, T. T., Le, H. D., & Duong, N. Q. (2021). Multimarket Contact and Risk-Adjusted Profitability in the Banking Sector: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(3), 1171-1180. Retrieved from 10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no3.1171

Demirgüneş, K. (2016). The Effect of Liquidity on Financial Performance: Evidence from Turkish Retail Industry. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 8(4), 2016. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v8n4p63

Derbali, A. (2021). Determinants of the performance of Moroccan banks. Journal of Business and Socio-economic Development, 1(1), 102-117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JBSED-01-2021-0003

Desai, R. (2021). Impact of priority sector lending on financial profitability: segment wise panel data analysis of Indian banks. Management & Accounting Review (MAR), 20(1), 19-38. doi:https://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/eprint/47752

Fatihudin, D. (2018). How measuring financial performance. International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET), 9(6), 553-557. Retrieved from http://www.iaeme.com/ijciet/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=9&IType=6

Gallo, A. (2015, 11 04). Harvard Business Review. doi:https://online210.psych.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/PSY-210_Unit_Materials/PSY-210_Unit12_Materials/Gallo_HBR_Regression_2015.pdf

Gatuhu, R. N. (2013). The effect of credit management on the financial performance of microfinance institutions in Kenya. Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi. Retrieved from http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/60220

Ghosh, A. (2018). Implications of securitisation on bank performance: evidence from US commercial banks. International Journal of Financial Innovation in Banking, 2(1), 1-28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJFIB.2018.092417

Godswill, O., Ailemen, I. O., Osabohien, R., Chisom, N., & Pascal, N. (2018). Working capital management and bank performance: empirical research of ten deposit money banks in Nigeria. Banks and Bank Systems, 49-61. Retrieved from https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=695801

Hoti, A. H., Hoti, H., & Berisha, A. (2024). Examining the Interconnectedness of Corporate Governance (CG), Non-performing Loans (NPLs), and Bank Size (BS) on the Financial Performance (FP) of Banks in Kosovo. The Framework for Resilient Industry: A Holistic Approach for Developing Economies, 109-119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83753-734-120241008

Kagoyire, A., & Shukla, J. (2016). Effect of credit management on performance of commercial banks in Rwanda (A case study of Equity bank Rwanda LTD). International Journal of Business and Management Review, 1-12.

Kagoyire, A., & Shukla, J. (2016). Effect Of Credit Management On Performance Of Commercial Banks In Rwanda (A Case Study Of Equity Bank Rwanda Ltd). International Journal of Business and Management Review, 4(4), 1-12. Retrieved from http://www.eajournals.org/

Lardic, S., & Terraza, V. (2019). Financial Ratios Analysis in Determination of Bank Performance. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 9(3), 22-47. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.32479/ijefi.7888

Lee, C.-C., Hsieh, M.-F., & Yang, S.-J. (2014). The relationship between revenue diversification and bank performance: Do financial structures and financial reforms matter? Japan and the World Economy, 29, 18-35. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2013.11.002

Maharjan, S. (2023). Effect of working capital management and credit management policy on financial performance of commercial banks in Nepal. Perspectives in Nepalese Management, 133-147. Retrieved from https://uniglobe.edu.np/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Perspectives-in-Nepalese-Management-Inner_compressed.pdf#page=133

Mahmudova, N. (2023). Determinants Influencing Financial Performance of Financial Institutions in Azerbaijan. TURAN-SAM, 160-169. Retrieved from https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1136057

Mshelia, A. H., & Polycarp, S. U. (2024). Effect of working capital management on financial performance of listed deposit money banks in Nigeria. FULafia International Journal of Business and Allied Studies, 2(1), 37-57. Retrieved from https://fijbas.org/index.php/FIJBAS/article/view/51

Munangi, E. (2020). An empirical analysis of the impact of credit risk on the financial performance of South African Banks. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 24(3). Retrieved from https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/75798685/An-Empirical-Analysis-of-The-Impact-of-Credit-Risk-on-1528-2635-24-3-554-libre.pdf?1638795033=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DAn_Empirical_Analysis_of_The_Impact_of_C.pdf&Expires=1732364776

Olabamiji, O., & Michae, O. (2018). Credit Management Practices and BankPerformance: Evidence from First Bank. South Asian Journal of Social Studies and Economics, 1-10. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.9734/sajsse/2018/v1i125772

Oli, S. K. (2021). Financial leverage and performance of Nepalese commercial banks. Journal of Asia Social Science, 1-22. doi:http://doi.org/10.51600/jass.2021.2.3.49

Péran, T., & Sdiri, H. (2024). Comparing the performance of Qatari banks: Islamic versus conventional, amidst major shocks. Finance Research Letters, 59. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.104776

Pike, R., & Cheng, N. (2001). Credit management: an examination of policy choices, practices and late payment in UK companies. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 28(7-8), 1013-1042. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5957.00403

Poh, L. T., Kilicman, A., & Ibrahim, S. N. (2018). On intellectual capital and financial performances of banks in Malaysia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1453574

Prenaj, V., Imeraj, J., & Smajli, S. (2023). Albania and Kosovo with Development Potential, but Limited Support from the Banking Sector. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 18(5), 1377-1383. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.18280/ijsdp.180507

Prenaj, V., Miftari, I., & Krasniqi, B. (2023). Determinants of the capital structure of non-listed companies in Kosovo. Economic Studies journal, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences - Economic Research Institute, 32(1), 36-50. Retrieved from https://www.iki.bas.bg/Journals/EconomicStudies/2023/2023-1/03_Vlora-Prenaj.pdf

Prenaj, V., Miftari, I., & Pula, L. (2024). The impact of capital structure on company performance: empirical evidence from Kosovo. Romanian Journal of Economic Forecasting, 27(1). doi:https://ipe.ro/new/rjef/rjef1_2024/rjef1_2024p87-102.pdf

Priharta, A., & Gani, N. A. (2024). Determinants of bank profitability: Empirical evidence from Republic of Indonesia state-owned banks. Contaduría y Administración, 69(3). doi:http://www.cya.unam.mx/index.php/cya/article/view/4999

Rahim, A., Ashraf, S., Iftikhar, W., Khan, M. M., Mehmood, S., & Siddique, M. (2021). The effect of financial leverage on the islamic banks’ performance in Asian Countries. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Governmen, 27(1). doi:https://cibg.org.au

Romli, N., Asma, W. N., Anuar, H., Isa, A., Mohamed, S., Haris, S., & Hasan, N. N. (2022). The Internal and External Factors That Determine the Performance of Islamic Banks in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Menagement Sciences, 12(3), 330-343. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARAFMS/v12-i3/14686

Santoso, W., Yusgiantoro, I., Soedarmono, W., & Prasetyantoko, A. (2021). The bright side of market power in Asian banking: Implications of bank capitalization and financial freedom. Research in International Business and Finance, 56. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101358

Serhii, L., Yuliia, S., Tetiana, Z., Zuzana, J., & Alena, K. (2023). The impact of financial performance on the profitability of advertising agencies in the Slovak Republic. Strategic Management, 28(1), 41-50. Retrieved from https://scindeks.ceon.rs/article.aspx?artid=1821-34482301041L

Silva, S. E., Camargos, M. A., Fonseca, S. E., & Iquiapaza, R. A. (2019). Determinants Of The Working Capital Requirement And The Net Operating Cycle Of Brazilian Companies Listed In B3. Revista Catarinense da Ciência Contábil, 1-16. doi:10.16930/2237-766220192842

Sujud, H., & Hashem, B. (2017). Effect of Bank Innovations on Profitability and Return on Assets (ROA) of Commercial Banks in Lebanon. International journal of economics and finance, 9(4). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v9n4p35

Sun, P. H., Mohamad, S., & Ariff, M. (2017). Determinants driving bank performance: A comparison of two of banks. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 42, 193-203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2016.02.007