Ekonomika ISSN 1392-1258 eISSN 2424-6166

2025, vol. 104(4), pp. 95–112 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2025.104.4.6

Pavol Ochotnický

University of Economics in Bratislava

Department of Finance

Dolnozemská cesta 1, 852 35 Bratislava

E-mail: pavol.ochotnicky@euba.sk

ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9868-1590

Marek Káčer

University of Economics in Bratislava

Department of Finance

Dolnozemská cesta 1, 852 35 Bratislava

E-mail: marek.kacer@euba.sk

ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3544-0327

Daša Belkovicsová*

University of Economics in Bratislava

Department of Finance

Dolnozemská cesta 1, 852 35 Bratislava

E-mail: dasa.belkovicsova@euba.sk

ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2213-5614

Denisa Ihnatišinová

University of Economics in Bratislava

Department of Finance

Dolnozemská cesta 1, 852 35 Bratislava

E-mail: denisa.ihnatisinova@euba.sk

ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9175-8284

Abstract. The COVID-19 pandemic shock resulted in a specific global health, social and economic multi-crisis, which was an unprecedented crisis in post-WW2 history. Both in terms of the devastating consequences on the health of the world’s population of sufferers, as well as on the extent of the impact on global economy. Based on the identified transmission channels of the pandemic into the economy and by using panel regression models, the contribution provides an explanation of the transmission of the pandemic to the health status of the population, to the labor supply, and subsequently, to a Type V recession. Based on these, the paper provides empirical evidence and policy recommendations that the government strictness in regulating population mobility, economic development of countries, population vaccination against COVID-19, and COVID fiscal health care spending were the main and most effective tools for reducing the live expectancy decrease in selected EU countries. To cushion the economic shock which the pandemic has directly had on the labor supply, the only effective anti-crisis fiscal instruments have been confirmed to be the effects of government capital spending, both in cushioning the recession and inflation.

Keywords: pandemic shock, global pandemic crisis, excess mortality, fiscal policy, COVID-19 spending.

________

* Correspondent author.

Acknowledgement. This paper is an output of the research project supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency No. APVV-20-0338 Hybné sily ekonomického rastu a prežitie firiem v šiestej K-vlne (Driving forces of economic growth and survival of firms in the sixth K-wave).

Received: 24/01/2025. Accepted: 21/09/2025

Copyright © 2025 Pavol Ochotnický, Marek Káčer, Daša Belkovicsová, Denisa Ihnatišinová. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The COVID-19 pandemic shock can be seen in retrospect as a test of the resilience of the global community, individual countries, their cohesion, and their ability to withstand the worst post-WW2 health, economic, and social crisis (multi-crisis). The initial pandemic shock, which caused excess morbidity and excess mortality in the population, was followed by the transmission of the pandemic to the economy through a decrease in labor supply, a decrease in hours worked due to morbidity, isolation measures against the spread of the pandemic in the economically active part of the population, and resulted in a decline in the economic performance of countries.

Subsequent supply-demand shocks exacerbated a 15-year trend of a slowing productivity growth, induced higher transaction costs, lower factor mobility, and a short-term spike in countries’ debt levels (Baldwin et al., 2020). The pandemic shock also caused unprecedented micro-structural and substitutionary changes; in addition to the health burden, the pandemic also burdened the social system, the entire public finance system, through a decline in government revenues due to reduced economic activity of the population and production, through an increase in public spending on health, social services, and through fiscal stimulus for economic recovery. The main active tool for mitigating the consequences of the pandemic shock has become the fiscal policy of national economies or their groupings1.

Compared to the response of countries and their governments to previous post-WW2 shocks and crises, the multidimensional global pandemic crisis required interdisciplinary and creative responses by political leaders, engaging interdisciplinarily thinking scientists and experts in mitigating its health, economic, and socio-political consequences. In line with Romer and Romer (2022), the pandemic caused a return to older policy concepts, where fiscal policy, in addition to managing the aggregate demand, placed a strong emphasis on the role of the government in protecting the health of the population and in providing insurance to the population against the consequences caused by a pandemic shock. Moreover, the pandemization of the economy requires strong and credible regulators and policy makers who can provide reliable information and guidance, while at the same time inspiring credibility by setting new rules (Pompella & Constantino, 2021).

The main purpose of the paper is to generalize the positive experiences of EU countries in overcoming the pandemic shock. The first part presents theoretical foundations and findings of purposefully selected studies with the aim of identifying transmission channels of the pandemic shock on the health status of the population, economic growth and inflation. The following is a section on regulatory and fiscal measures taken by governments to cushion the pandemic shock, along with brief empirical facts. The next part presents the main hypotheses, methodology, and data used. The test results constitute the content of the third part. The final part of the paper contains learning from the COVID-19 crisis and the main general recommendations for an appropriate policy mix for successfully mitigating the health and economy impacts of pandemic shocks.

Eichenbaum, Rebelo, and Trabandt (2020) attempted to link the Kermack-McKendrick SIR model to the economy by explaining the equilibrium and interaction between the economy and the epidemic. According to the authors, although people’s decisions to reduce consumption and work reduce the severity of the epidemic, as measured by the total number of deaths, they simultaneously exacerbate the magnitude of the recession caused by the epidemic through supply-demand effects (shocks). They explain pandemic supply shocks by the fact that the epidemic supply effect arises through workers being affected by the virus, and workers respond to this risk by reducing the supply of labor. The demand effect, in turn, arises because the epidemic exposes consumers to the virus, and they respond to this risk by reducing consumption.

Based on the experience of the SARS pandemic in 2002 and 20032, Brauer (2005) has already pointed out that the real epidemic differs significantly from the idealized models. He cites the following important differences:

Rio-Chanona et al. (2020) suggest that demand during the pandemic was reduced due to efforts to avoid infection. The authors’ finding was that sectors such as transportation are likely to be constrained by demand shocks, while sectors related to manufacturing, mining, and services are more likely to be constrained by supply shocks. Sectors such as entertainment, restaurants and tourism face large shocks on both the supply and demand side. Demand shocks in the health and social services sectors have had a positive impact. At the same time, the study shows that high-wage occupations are relatively immune to the adverse effects of supply- and demand-side shocks during the global pandemic crisis, while low-wage occupations are much more vulnerable.

The global pandemic crisis, due to the restriction of mobility as a measure against the spread of the epidemic, has triggered unique changes and increased the pressure for entities to adapt to new technologies and services and their development, whether in the provision of healthcare, but also in household consumption, production and distribution of products and the way of governance. It has also been a chance to absorb revolutionary and non-revolutionary innovations and technological changes that have eliminated the risk of spreading and the consequences of the infection, mainly through the rapid development and support of digital and ICT technologies. In addition to telemedicine, this has included increased online shopping, as well as the development of robotic delivery systems, the introduction of digital and contactless payment systems, remote working and the role of technologies in distance learning, 3D printing and online entertainment (Renu, 2021).

The theoretical underpinnings of the synthetic impact of demand and supply shocks on the aggregate demand and supply are clearly explained by Blanchard (2000). He also suggests that automatic fiscal stabilizers can dampen the negative effects of shocks on the output volatility. This is on both the aggregate demand side and on the aggregate supply side. The illustrative algebraic model used by the author to explain the impact of a synthetic supply-demand shock on output is based on the following equations:

after modifying the expression for the aggregate bid AS: y = p – es.

All variables are in a logarithmic form, y and p represent the output and the price level, respectively, and ed and es represent demand and supply shocks, respectively. A higher price level reduces the demand for products (via a decline in the real money balance). A higher output leads to a higher price level. The impact of the strength of automatic stabilizers can be seen through the reduction of the coefficient c in the AD expression. Then, the output affected by both shocks is given by the expression:

Demand shocks, on the other hand, are understood as events that, when impacting the economy, move the price level and real output in the same direction as a result of either a positive or negative demand shock to consumption, investment, government spending, or net exports.

From the perspective of the shock theory link, the pandemic global supply shock did not primarily originate in a shock change in the relative prices of labor, capital, technology or energy, but in a restriction in the supply (quantity) of labor by non-economic – i.e., by pandemic factors. As a result of the temporary mass illness of the economically active population, their compulsory quarantine, as well as area or local lockdowns, a part of the labor supply in working hours by a household was significantly reduced. In a normal market-driven situation and without government intervention, businesses would quickly respond to labor shortages and exogenous supply and demand shocks caused by the pandemic by closing down businesses and service enterprises, reducing inventories, and laying off workers.

Fiscal policies of countries during the global pandemic crisis contributed significantly to cushioning such consequences, with each country individually approaching the use of fiscal stimuli for social security, population health, job preservation, and business sustainability. Following the introduction of ‘fiscal packages’ to rescue the economy and jobs through short-term temporary measures in individual countries, and after mitigating health risks, country policies have individually made progress in population and economic health (Balmford et al., 2020).

As reported by Auerbach et al. (2023), many governments adopted unprecedented fiscal stimulus in response to the global pandemic crisis, examining how effective counter-cyclical fiscal policy was in combating recession under conditions of ‘economic lock-in’. The authors confirmed that the effects of government spending were stronger in the US economy during the peak of the pandemic recession, but only in those cities that were not subject to strong mobility bans and orders for employees to stay at home, i.e., without a strong lock-in. In contrast, anti-pandemic spending in the early part of the pandemic created inflationary pressures (Hale, Galina, Leer, & Nechio, 2023).

In the case of a global pandemic crisis, Guerrieri et al. (2022) can be considered as one of the first papers on the emergence of demand shocks during a crisis. The study views the pandemic demand shock through the explanation that the forces of supply and demand are linked: demand is endogenous and affected by the supply shock and other characteristics of the economy. The authors’ research has shown that a scenario in which the fall in demand is larger than the fall in supply is particularly likely if long-term constraints on labor supply lead to a collapse in investment.

The global pandemic crisis has created further unprecedented declines in the output and productivity in the short term. This has exacerbated the so-called productivity ‘paradox’ observed since the late 1980s, when investment in information technology did not translate into an increased productivity (Solow, 1987). However, the global pandemic crisis has contradictorily revived the expectations and hypotheses of some economists, where new technologies and expenditures, e.g., on digital transformation, offer room for more effective mediation and exploitation of the potential of ICT, especially in new business and communication models in different sectors, e.g., transport (smart and electro-mobility), energy, but also in sectors such as public services, health care, etc. (Van Ark et al., 2020). Fedirko and Zatonatska (2020), by using selected countries as examples, conclude that a key sector during a pandemic is the information and communication technology and e-commerce sector, which grows in popularity during a quarantine and becomes an integral part of business and the general public.

Ma et al. (2021) identified four trajectories for a government response against the spread of COVID-19. The authors examined how timely and vigilant governments were in their response to different initiation stages and trajectories in the spread of COVID-19 across space and time. They found that social control measures against the spread of the virus and the growth of contagiousness initially worked well for COVID-19 in areas like Singapore, Japan, and China, and reached Europe later. Xiong et al. (2020), in turn, noted an unprecedented increase in mortality early in the pandemic, but also a deterioration in mental health in the surviving population. Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant increase in mortality in Europe in 2020 on a scale not witnessed by humanity since the Second World War (Aburto et al., 2022). In doing so, multiple untreated and delayed diagnoses pose additional risks to population quality, especially in countries with less accessible healthcare and a less developed health care system.

Agostini, Bloise, and Tancioni (2024) estimated the dynamic effect of vaccination on COVID-19 mortality by using weekly data from 26 European Union countries in 2021. In the basic model specification, they showed that a 10-percentage-point increase in cumulative doses per hundred population averts 5.08 COVID-19 deaths per million population, and the average mortality reduction over an 8-week horizon is close to 50%.

The development and measurement of the COVID-19 index of government stringency has contributed significantly to research on prevention against the spread of the pandemic. This index (Hale et al., 2021) has become a frequently used measure of prevention and a strategy serving for country situation comparison. The index is based on nine indicators of a government response in the form of school closures, workplace closures, and travel bans, converted to a value from ‘0’ to ‘100’ (100 = most stringent). By using regression models, Violato et al. (2021) found that the index of government stringency had the most important effect on eliminating excess mortality. The authors confirmed the generally accepted relatively high predictive power of the impact of the restrictive measures of governments included in the stringency index on the total number of deaths per million population, on the total number of cases per million population, on the total number of deaths per million population, and on new cases per million population. In addition to the stringency index, other important factors in eliminating the impact of pandemic shock, according to the authors, were hospital ICU beds per 100,000 population, prevalence of diabetes, GDP per capita, cardiovascular mortality, and the percentage of the population aged 65 years or older.

Fiscal packages in EU countries varied in size, with one objective being to maintain corporate cash-flow (e.g., extending tax filing deadlines, tax deferral, faster tax refunds, tax and levy exemptions, tax loss clawbacks, etc.), worker retention (e.g., short-time work schemes, wage subsidies, etc.) and household income support (e.g., targeted cash benefits, simplifying and extending access to social benefits, etc.)3.

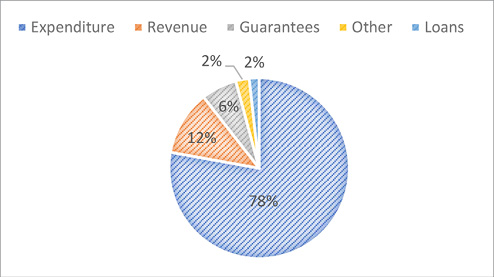

Expenditure measures dominated the structure of the government’s anti-Covid measures, as presented in Figure 1.

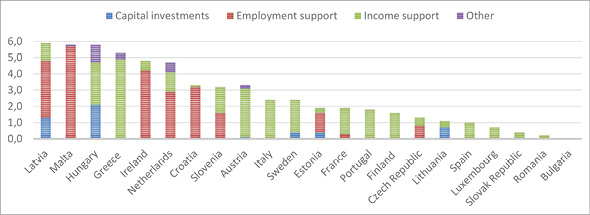

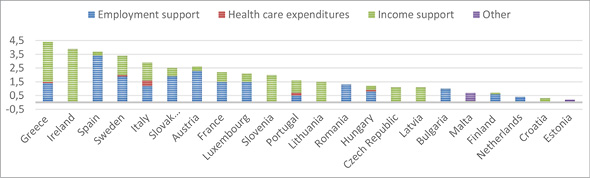

The fiscal responses of governments in the EU to the global pandemic crisis have been specific in each country. In some countries, investment and business support spending dominated, whereas, in others, transfers to households and employers were predominant. Specifically, fiscal measures in the selected EU countries surveyed with the available data to support the economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic averaged 4.89% of GDP in 2020 and 3.65% of GDP in 2021. However, fiscal policy responses to the negative impacts of the pandemic on the economies of the countries were generally swift and broad-based. Figures 2 and 3 show the difference in the scope and the mix of individual fiscal expenditures of national governments in the EU countries according to expenditure on non-financial corporations, as well as households.

Figures 2 and 3 only illustrate, by using average of the years 2020 and 2021, how different selected EU countries responded to their specific conditions and the pandemic shock, whether in terms of volume, weight of individual fiscal instruments, or different approaches to directing their spending towards households versus corporations, or to stimulating aggregate demand versus supply.

The key methodological tool of the article is panel regression and three models, developed to verify two main research questions:

a) Through which transmission channels did the pandemic affect the changes in the health status of the population, fluctuations in output and inflation?

b) What was the political response of the governments of the selected EU countries, and which policies had positive effects in cushioning the pandemic shock?

The global pandemic crisis resulted in a significant and distinct synthetic decline in the population size and a subsequent reduction in life expectancy due to the direct impact of the pandemic on the excess mortality in individual countries.

The primary and main determinant or the primary impetus for changes in the health status of the population was the intensity of transmission of the COVID-19 infection among the population of a given country (Hypothesis 1). We suppose that, on the other hand, stringent measures by governments to restrict mobility and to reduce social contact through government stringency acted in a significantly eliminative manner to counteract the spread of the disease and to tackle the increase in mortality in the country. We further hypothesize that the economic maturity of the country, the quality (accessibility) of health care, the public spending increase on health care during the pandemic, and the degree of digitalization which reduced the physical contacts between people in the country had a positive impact on the maintenance of the health status of the entire population during the global pandemic crisis. Similarly, vaccination of the population also acted to reduce the fatal consequences of the pandemic and sickness absence.

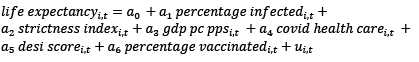

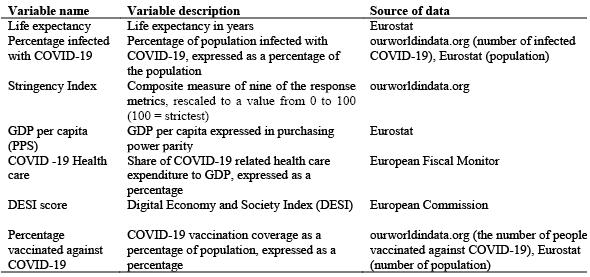

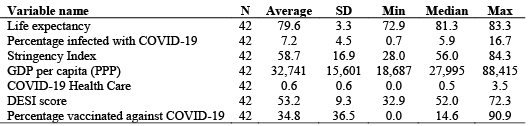

As a tool to verify Hypothesis 1 and the basic research questions of the paper, we use the different multiple regression models using a panel data structure. In line with the explanation above, we use the following basic model specification and proxy variables:

where i (j = 0, 1, 2, ... 6) are the parameters of the equation and ui,t is the random error. The model parameters are estimated by using the simple least squares method, fixed as well as random effects.

By selection of appropriate explanatory variables, the main determinant of the deterioration in population health during the global pandemic crisis was the extent to which the country’s population was affected by the COVID-19 virus. As a proxy indicator, we use the proportion of a country’s population infected with the COVID-19 virus as a proportion of the total population, which has been consistently monitored by the WHO. In contrast, we hypothesize that the method of applying lockdowns has been shown to reduce the risk of disease spread. We approximate this determinant by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre’s index of the government stringency index, which captures how governments restricted social contacts.

Further, as indicators of a country’s economic maturity, we use GDP per capita in purchasing power parity as the health system quality proxy indicator, which could lead to dampening the excess mortality, and finally to life expectancy changes4. Internet users, fixed broadband subscriptions, internet bandwidth and mobile broadband subscriptions as a sub-index of a country’s digitalization readiness, which not only indicates the ability of countries to adopt and use current information and communication technologies. We consider that the DESI country score appropriately describes the degree of the application of telemedicine and modern non-contact care, which could have had a dampening effect, especially in the early stages of an outbreak, as well as at the peaks of the spread of the epidemic. Population vaccination rates with COVID-19 vaccines are also thought to be an eliminating factor in the effect of the pandemic on the probability of survival. Likewise, COVID-19 health care expenditures should be considered.

In explaining the causes of changes in the life expectancy as a dumping proxy dependent fiscal variable, we hypothesize that the negative effects of the pandemic on the population health changes in countries were buffered by the degree of using COVID-19 fiscal spending to GDP.

In the analyses, we use panel data for the selected EU countries for which consistent public expenditure data were available for research purposes5. The data are for the period 2020–2021, and we view the panel as being relatively small.

Regarding the dependent variable, in this sample, the mean life expectancy is 79.6 years, with values ranging from 72.9 to 83.3 years. Regarding the main explanatory variables, the mean value of the percentage of the population infected with COVID-19 is 7.2%, with values ranging from 0.7% to 16.7%; the mean value of the stringency index in the sample is 58.7, with values ranging from 28 to 84.3; and, finally, the mean value of the percentage vaccinated against COVID is 34.8%, with values ranging from 0% to 90.9%.

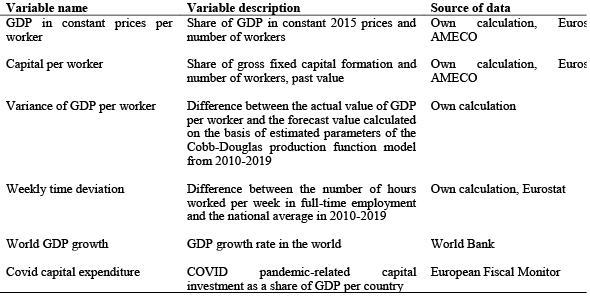

Given the above specificities of the global pandemic crisis, we attempt to explain the hypothesis through modified dependent variables in the form of deviations of labor productivity and inflation from pre-pandemic developments. To test the transmission mechanism of the pandemic shock on changes in economic growth and inflation, the following methodological procedures were applied in the paper.

Relative to the recession in 2020 and the recovery of economic growth in 2021, we assume (Hypothesis 2) that the supply shock via the decline in hours worked by the labor force was the primary and decisive factor in the decline in GDP across countries, with pre-pandemic levels of employment and wages being sustained by fiscal spending during the initial shock. We argue that the global impact of the pandemic translated into a subsequent supply and demand shock to the domestic and external environment, which caused supply-side constraints in national economies and a decline in demand for goods and services in the world economy. We assume that the elimination of demand-supply shocks and the dampening of the recession in 2020 had a positive impact on the aggregate supply side of COVID-19 capital spending, while pandemic public spending to support households could lead by the supply constrain likely to inflationary effect.

In testing H2, we used two steps model approach. The impact of the pandemic labor supply constraint on the quantities of output we expressed via using a two-factor Cobb Douglas production function form as follows:

∆Yt/Lt = Yf (Kt, / Lt) – Yf (Kt /(Lt – ∆Lt))

where ∆Yt/Lt expresses the labor productivity difference caused by the pandemic shock via change in hours worked in time of pandemic crisis, Kt, respectively, Lt is the capital stock with regard to labor in the number of hours worked, ∆Lt expresses the reduction of labor hours worked due to workers getting sick, quarantine, treating family members, etc., in comparison to the pre-pandemic level.

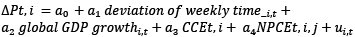

In the second step, we formulate the model for the explanation of the changes in the labor productivity (in t=2020, 2021, in country i) by using the following formula:

where i (j = 0, 1, 2, 3) are the parameters of the equation, and ui,t is the random error.

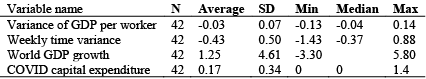

As the special experimental variable, we use and include in the model the percentage variable of COVID-19-related capital expenditures (CCEt.i) and other different (j) non-capital types of anti-pandemic government spending (NCCEt.i,j) to GDP. We use data for the selected EU countries, for which, consistent data on relevant variables were available for the period of 2020–2021. Data description contains Table 3 and Table 4. Since non-capital government expenditures proved to be insignificant in preliminary tests of the model, we no longer include them in the description of the variables.

In explaining the inflation of the pandemic shock, we assume (Hypothesis 3) that the supply-side pandemic shock caused downward pressure on prices due to a decrease in the labor supply itself and disruptions in world trade. Since unemployment did not act as a regulator of wage pressures, falling labor and production prices, while maintaining employment and dampening unemployment in European countries through significant fiscal spending, it was not appropriate to use the traditional concept of the Phillips curve as a traditional modelling approach. We also believe that, under conditions of limited supply, fiscal spending to increase demand caused upward pressure on inflation.

We attempted to test this hypothesis with another model, where the dependent variable was the deviation from inflation (∆Pt,i) in 2020 and 2021 and from the 2010 to 2019 on average for each country (i). In each group of models, the first model was given an estimation by using the simple least squares method, whereas the second model used fixed effects, and the third model used random effects. Variables expressing the supply shock as a change in hours worked and world GDP were used as explanatory variables. As experimental variables, the percentage variable of COVID-19-related capital expenditures (CCEt.i) and other different (j) non-capital types of anti-pandemic government spending (NCCEt.i,j) to GDP were similar to those in Equation (5) used for testing.

The basic model form is as follows:

where i (j = 0, 1, 2, 3) are the parameters of the equation, and ui,t is the random error. Data sources and descriptive statistics have already been presented in the previous tables.

We attempted to test this hypothesis with another group of models. In each group of models, the first model was estimated by using the simple least squares method, whereas the second model used fixed effects, and the third model used random effects.

In all three models, the percentage of those infected with COVID-19 is negatively correlated with life expectancy. The models differ in the magnitude of the effect. In the continuous regression model, the effect is the largest, that is, a one-percentage-point increase in the percentage of the infected reduces the life expectancy by 0.33 years on average, ceteris paribus. In fixed or random effects models, the magnitude of the effect is smaller, where an increase in the number of infections induces a reduction in the life expectancy by slightly less than 0.2 years. As for the other variables, in all models, the DESI score and the percentage of those vaccinated against COVID-19 are statistically significant variables. Both variables are positively correlated with the life expectancy, which is in line with expectations. In the pooled regression model, the government stringency index and GDP per capita are additionally statistically significant variables.

Usually, with panel data, an important question is whether the dependent variable is determined by some other unobserved explanatory variable that is constant across the countries involved. In our research, a test of the pooled statistical significance of the fixed effects suggests that this is the case. In determining the final specification, it remains to be decided whether it is more appropriate to use fixed or random effects. The results of the Hausman test suggest that the random effects model is more accurate in the sense of more efficient parameter estimation. That is, in this case, the random effects model is the most accurate (the number of estimated parameters relative to the number of observations, among other things, speaks against the fixed effects model).

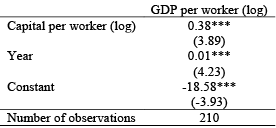

The results of the Cobb-Douglas model test for productivity (Step 1) are presented in Table 6.

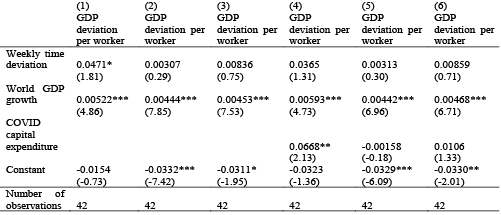

Contrary to expectations regarding Step 2, the deviation of weekly working hours from the long-run average turns out to be a relatively weak predictor of the change in the dynamics of GDP per worker growth during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Table 7). The estimated parameter of this variable is statistically significant only in Model 1, and, even then, only at a 10% significance level. This implies that this variable weakly affects differences in productivity and GDP growth between countries, but not within countries. In contrast, world GDP growth has been found to be an important determinant of differences in GDP per worker across countries. As expected, the direction of the effect is positive, i.e., when the world GDP increases, GDP within countries also increases. In quantitative terms, a 1-percentage-point increase in the world GDP is, on average, associated (ceteris paribus) with an increase in GDP per worker at around 0.5%. Models 4 to 6 also include a variable for the share of capital investment in GDP in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The results suggest that countries with a higher share of this expenditure have higher deviations from GDP, while, within countries, this variable does not prove to be a significant predictor of GDP dynamics.

The pooled fixed effects statistical significance test indicates that there are unobserved variables which do not change over time and affect the dependent variable. Again, the results of the Hausman test suggest that the random effects model is more accurate, in the sense of more efficient parameter estimation.

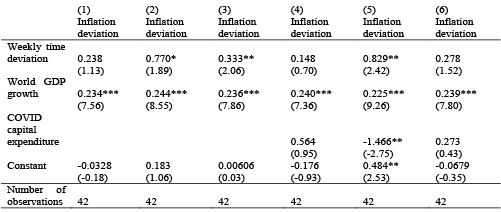

As the results (see Table 8) of the model estimations showed, the models were consistent with the theory and hypotheses in only giving sufficient confidence in the impact of world trade demand on growth – on the deviation of inflation from the average pre-covariance value. In terms of the fiscal impact on inflation, only the growth in COVID-19 capital spending dampened inflationary pressures, while other experiments on the post-inflationary impact of COVID-19 demand-led spending were not credibly confirmed over the period.

The global pandemic crisis of 2020 and 2021 affected all analyzed European countries by the widespread cross-border spread of the COVID-19 virus. Nevertheless, these countries managed to overcome or eliminate the negative consequences of the global multi-pandemic crisis, which caused a broad spectrum of changes in the health status of the population, as well as the depth of the short-term recession, with varying degrees of success.

The negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was reflected in a reduction in life expectancy virtually for all EU countries surveyed. Life expectancy in the pre-pandemic period averaged 80.6 years, ranging across countries from 75.6 years to 84 years. Due to the pandemic, life expectancy decreased by 1.9 years in 2021 compared to 2019 on average across countries; the shift ranged from 0 years (Malta) to -3 years (Slovakia). Based on theoretical considerations, as reflected in hypotheses and models, it has been shown quite plausibly that the number of infected populations for COVID-19 negatively influenced changes in life expectancy. Despite the relatively small set of observations, health and economic impact research for selected countries has confirmed and complemented the findings of other authors during pandemic episodes that the avoidance of a reduced life expectancy during a pandemic can be effectively prevented, particularly by targeted government stringency and population discipline in limiting social contact and by vaccinating the population. The maturity of the economy, the health system, the penetration of digitalization, and public spending on health care, in turn, buffer the fatal consequences in a segment of the infected population.

In terms of recession and the subsequent recovery, the model estimates are relatively robust in confirming that the pandemic shock, which hit the gross domestic product of national economies through a decline in both hours worked and labor productivity per worker, was negatively affected by an external supply/demand fluctuation in the world economy. COVID-19 capital spending contributed to the recovery from the recession. Other types of COVID-19 spending (health care expenditures, income support, employment support) aimed at stimulating demand did not prove significant in the experiments, which is in line with the theoretical assumption of a supply-side constraint, especially during the first year of the pandemic shock.

In line with the theory and Hypothesis 3, the model for explaining inflation only gave sufficient confidence in the effect of the world trade demand on growth – the deviation of inflation from the average pre-inflation value for the selected countries. In terms of the fiscal impact, only the COVID-19 growth in capital spending had anti-inflationary effects. The presumed inflationary effect of COVID-19 spending in supporting the demand has not been credibly confirmed over the period. An explanation to be offered is that it had different effects on inflation during the initial phase of the global pandemic crisis and during the growth recovery in 2021, and there were no constraints on the aggregate supply side in the recovery phase form the pandemic shock.

Fiscal policy, which not only dampened but also actively supported the health of the population during and after the pandemic, as well as economic growth, became a key tool for overcoming and eliminating the impacts of the pandemic multi-crisis. Although many fiscal responses of governments and fiscal instruments of the selected countries were similar, their concept and combination in terms of scope, as well as direction and priorities, e.g., for households, businesses or towards healthcare, differed in individual countries.

The conclusions of the paper show that government activities during the fight against the pandemic should be focused on targeted restriction of population mobility and transmission of the infection, whether at the national or regional level, but also on raising awareness about the positive effects of preventive protective measures and vaccination. The key determinant of successfully overcoming the health dimension of the pandemic was not only the level of quality of the health system and the level of economic maturity, but also the digital maturity of the respective countries. According to the findings of the paper, a successful mix of fiscal policies to mitigate the recession during the pandemic crisis was a policy focused on supporting capital expenditures and not consumption expenditures, which also had positive dampening effects on inflationary pressures during the crisis. Fiscal measures, primarily focused on capital public expenditure of the supply type, also dampened the consequences of inflationary pressures in European economies.

Aburto, J. M. et al. (2022). Quantifying impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic through life-expectancy losses: a population-level study of 29 countries. International Journal of Epidemiology, 51(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab207

Agostini, E., Bloise, F., Tancioni, M. (2024). Vaccination policy and mortality from COVID-19 in the European Union, The Econometrics Journal, 27(2), 299–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/ectj/utae005

Blanchard, O. (2000). Commentary. FRBNY Economic Policy Review, April 2000, http://economics.mit.edu/files/719

Blinder, A. S., Rudd, J. B. (2013). The Supply-Shock Explanation of the Great Stagflation Revisited. In The Great Inflation: The Rebirth of Modern Central Banking. University of Chicago Press. https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/great-inflation-rebirth-modern-central-banking/supply-shock-explanation-great-stagflation-revisited

Centre For European Policy Studies (2022). European Fiscal Monitor: January 2022, https://www.euifis.eu/publications/25

Eichenbaum, M., Rebelo, S. T., Trabandt, M. (2020). The Macroeconomics of Epidemics (March 2020). CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14520, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3560328

Fedirko, O., Zatonatska, T. (2020). Development Strategies for National Economies After Covid-19 Pandemic. Ekonomika, 99(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2020.2.6

Guerrieri, V. et al. (2022). Macroeconomic Implications of COVID-19: Can Negative Supply Shocks Cause Demand Shortages? American Economic Review, 112 (5), 1437–1474. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20201063.

Hale, T. et al. (2021). A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker), Nat Hum Behav 5, 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

IMF (2020). Fiscal Monitor, October 2020: Policies for the Recovery, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/10/27/Fiscal-Monitor-October-2020-Policies-for-the-Recovery-49642

Kermack, W., McKendrick, A. (1927). A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. In Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, series A 115:700–721.

Keshky, M. et al. (2020). Getting Through COVID-19: The Pandemic’s Impact on the Psychology of Sustainability, Quality of Life, and the Global Economy – A Systematic Review. Front Psychol, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.585897.

Ma, Y. et al. (2021). The relationship between time to a high COVID-19 response level and timing of peak daily incidence: an analysis of governments’ Stringency Index from 148 countries. Infect Dis Poverty, 10(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-021-00880-x.

OECD (2011). Health at a Glance, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2011_health_glance-2011-en

OECD (2023). Social Expenditure (SOCX) Update 2023: The rise and fall of public social spending with the COVID-19 pandemic, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/OECD2023-Social-Expenditure-SOCX-Update-Rise-and-fall.pdf

Pompela, M., Constantino, L. (2021). Financial Innovation and Technology after COVID-19: a few Directions for Policy Makers and Regulators in the View of Old and New Disruptors. In Ekonomika, 100(2), 40–62. https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2021.100.2.2

Renu, N. (2021). Technological advancement in the era of COVID-19. Sage Open Medicine, 9. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121211000912.

Rio-Chanona, R. M. et al. (2020). Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic: an industry and occupation perspective. In Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(1), 94–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/graa033

Romer, CH., Romer, D. H. (2022). A Social Insurance Perspective on Pandemic Fiscal Policy: Implications for Unemployment Insurance and Hazard Pay. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36(2), 3–28.

Solow, R. M. (1987). We’d Better Watch Out. New York Times Book Review, New York Times, New York, July 1987, pp. 36.

Van Ark, B., de Vries, K., Erumban, A. (2021). How to not miss a productivity revival once again. National Institute Economic Review, 255, 9–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/nie.2020.49.

Violato, C. et al. (2021). Impact of the stringency of lockdown measures on covid-19: A theoretical model of a pandemic. PLOS ONE, 16(10), e0258205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258205

Xiong, J. et al. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord, (277), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001.

Zitikytė, K. (2022). The Initial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Older Workers in Lithuania. Ekonomika, 101(2), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2022.101.2.4

1 According to the OECD (2023), with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ratio of public social spending to GDP increased from 20% of GDP on average across the OECD in 2019 to 23% in 2020, with more than 80% of this growth being driven by the increase in spending rather than the decline in GDP.

2 Let us note that the SARS pandemic and other epidemic episodes were incomparably less extensive and devastating than COVID-19.

3 Based on EU Fiscal Monitor.

4 According to the EUROSTAT data, there are huge differences between the EU countries, and the selected countries also coped with the pandemic with varying degrees of change: from a decrease of -4.1% to an increase of 11.8% in terms of GDP in purchasing power parity, on average, for 2020 and 2021 and compared to the year 2019 levels.

5 The sample includes data for the following countries: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Austria, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.