Ekonomika ISSN 1392-1258 eISSN 2424-6166

2025, vol. 104(4), pp. 43–61 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Ekon.2025.104.4.3

Jordan Kjosevski

Research Collaborator, University St. Kliment Ohridski – Bitola, Macedonia

E-mail: jordan_kosevski@uklo.edu.com.mk

ORCID: https://orcid.org//0000-0001-9608-4090

Abstract. This study investigates inflation dynamics in the Visegrád countries – specifically, Poland, Hungary, Czechia, and Slovakia – by using the Mean Group estimator for 2000–2023. Results show a strong long-run link between the wage growth and inflation, as a rising purchasing power fuels consumption. Global price factors significantly drive local inflation, underscoring vulnerability to external shocks, particularly amid geopolitical tensions like the Ukraine war. Government consumption, however, helps moderate inflation over time, suggesting that productive public spending can stabilize prices. In the short run, wage growth still impacts inflation – yet less intensely, while reflecting gradual price adjustments. The Ukraine conflict highlights persistent uncertainties influencing expectations. Policymakers should align wage policies with productivity gains and monitor external price pressures closely. Overall, the study provides insights into the ways how domestic and global factors interact to shape inflation in the Visegrád region, informing debates on economic stability and policy responses in Central and Eastern Europe.

Keywords: Inflation dynamics, Visegrád countries, MG method.

________

Received: 26/01/2025. Accepted: 21/09/2025

Copyright © 2025 Jordan Kjosevski. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Amidst the inflation surge that swept through Europe in 2021–2023, an intriguing price dynamic unfolded in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The Visegrád group of four CEE countries (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) experienced lower inflation peaks compared to the Baltic countries (Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia). However, throughout 2023, inflation rates in the Visegrád countries remained persistently high – generally above 5% – and were comparable to those observed in the Baltic countries during the same period.

A number of questions can be raised in this regard: What factors contributed to these observed price developments in the Visegrád countries? Why did these economies face challenges in bringing inflation down? And did Euro area membership affect inflation outcomes – and, if so, to what extent?

The Visegrád economies share similar political, economic, and cultural backgrounds, transitioning from centrally planned to market economies in the early 1990s, which spurred reforms, foreign investment, and growth (Visegrád Group, 2023). Inflation in Central and Eastern Europe surged from late 2021, initially driven by pandemic-related supply disruptions and fiscal measures that boosted demand amid a constrained supply (Baba et al., 2023). As restrictions eased, pent-up demand further fueled price increases.

Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine worsened the situation by destabilizing energy markets and raising costs (Arce et al., 2023). In response, non-Euro area Visegrád countries quickly implemented aggressive monetary tightening. The Czech National Bank raised rates from 0.25% to 7% (June 2021–June 2022), compared to an increase in Hungary from 0.60% to 13% (June 2021–September 2022), and in Poland from 0.10% to 6.75% (October 2021–September 2022).

By contrast, Slovakia, as part of the Euro area, was constrained by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) slower response, with the first ECB rate hike occurring in July 2022. Thereafter, the ECB increased interest rates incrementally to 4% by June 2023 in an effort to bring inflation back to its 2% medium-term target.

Understanding the underlying drivers of inflation in the Visegrád countries is critical for designing effective and differentiated policy responses. Despite a shared EU membership and similar historical trajectories, the four economies differ in their labor markets, fiscal flexibility, and monetary regimes. Hungary and Poland exhibit rigid labor market structures and widespread wage indexation mechanisms, intensifying the wage–inflation feedback loop. Conversely, Slovakia’s Eurozone status limits the scope for independent monetary interventions, thus increasing reliance on fiscal policy and structural reforms.

The effects of external shocks such as the energy crisis and global supply chain disruptions were asymmetric, given variations in energy dependency and trade integration across the Visegrád group. This highlights the necessity for tailored energy security and supply chain resilience strategies.

Furthermore, our analysis suggests that value-added tax (VAT) revenues exhibit procyclicality, reflecting broader economic fluctuations. This calls for counter-cyclical fiscal policies and targeted transfers, particularly intended to protect vulnerable households from a disproportionate burden imposed by inflation.

By linking inflation outcomes to institutional and structural characteristics, this study contributes to evidence-based policy formulation that aligns with each country’s economic configuration and constraints.

To provide a structured framework for our investigation, the following hypotheses are proposed to guide the empirical analysis in this study:

This study aims to systematically investigate the inflation dynamics within the Visegrád Group from 2000 to 2023, with a particular focus on the post-2020 inflation surge. By analyzing a broad range of domestic and global influences, the study seeks to identify the channels through which inflationary pressures materialized and persisted.

To address these hypotheses, a multi-dimensional methodological framework is adopted, combining both qualitative and quantitative techniques. Time-series and panel data econometric models are employed to explore historical inflation trends and estimate the relative impact of internal versus external drivers.

The variables incorporated in the empirical models include:

The comparative structure of the analysis allows for isolating the effects of the Euro area membership, particularly in the case of Slovakia, and for evaluating the flexibility and effectiveness of different monetary and fiscal policy regimes.

The findings are then contextualized with country-specific institutional features, by using qualitative assessments to interpret the results and provide targeted policy implications.

This research contributes to the broader literature on inflation management in emerging European economies, particularly within the context of a common monetary framework like the Euro area. By distinguishing between shared and country-specific inflation drivers, the study offers a nuanced understanding of macroeconomic resilience and policy autonomy in the face of global shocks.

Moreover, the hypotheses presented serve as a roadmap for policymakers to evaluate the effectiveness of national monetary strategies versus Euro area-wide measures. As inflation pressures evolve, especially under the ongoing energy and geopolitical uncertainties, insights from this study can guide both national governments and European institutions in tailoring interventions that are both effective and equitable.

The subsequent sections of this study are structured as follows: Section Two provides a review of the relevant academic literature. In Section Three, we delve into detail regarding our empirical approach, including the data sources and variables used in our analysis. Moving forward to Section Four, we present the empirical findings. Discussion section is integrated into this paper as Section Five. Finally, the sixth section concludes the study.

Recent inflation dynamics in Europe have drawn growing scholarly and policy interest, especially in the context of multiple overlapping shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic, energy price volatility, supply chain disruptions, and geopolitical instability. Yet, the academic literature remains fragmented in terms of country coverage, time periods examined, methodological consistency, and benchmark comparisons. Most prominently, studies tend to examine either the entire European Union (EU), the Euro area, or broader regional clusters, while often neglecting sub-groups such as the Visegrád countries (specifically, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) as a distinct analytical unit.

From a theoretical standpoint, inflation dynamics are shaped by both demand- and supply-side factors, as well as by expectations and policy credibility. The New Keynesian Phillips Curve (NKPC) framework posits that inflation depends on expected future inflation, output gaps, and cost-push shocks (Galí & Gertler, 1999). In transitioning economies, inflation expectations tend to be more volatile and less anchored due to a lower credibility of the central bank and higher fiscal dominance, particularly in times of crisis.

Moreover, recent advances in behavioral macroeconomics suggest that adaptive expectations and incomplete information may also play a role in inflation persistence (Coibion & Gorodnichenko, 2015). These insights are especially relevant for the Visegrád countries, where institutional frameworks and communication strategies have evolved significantly while remaining uneven in terms of effectiveness.

Early studies on inflation convergence in the EU typically focused on compliance with the Maastricht criteria. One of the most cited studies, notably, Broż and Kočenda (2017), investigated inflation convergence across the 28 EU member states from 1999 to 2016 by using the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). They tested convergence against multiple benchmarks, such as the European Central Bank’s (ECB) 2% target, Germany’s inflation rate, and the Maastricht threshold. Their results revealed nominal convergence, but with ambiguities regarding whether this trend was driven primarily by EU accession, or by broader monetary policy coordination.

Beyond convergence, Nagy and Tengely (2018) focused specifically on Hungary, while using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Structural Vector Autoregression (SVAR) with the objective to identify key inflation drivers from 2003 to 2017. Their main finding pointed to a flattening of the Phillips curve post-2012, with external factors such as the EU output gap playing an increasingly prominent role. The study implicitly raised concerns about the diminishing effectiveness of the domestic monetary policy in smaller, open economies integrated into larger economic blocs.

Recent studies have increasingly shifted attention to structural determinants of inflation, such as wage growth, labor market conditions, energy prices, and monetary policy regimes. Čaklovica and Efendic (2020), by using dynamic panel modeling for 28 European countries from 2005 to 2015, found that unemployment and real wage growth were among the most robust long-term predictors of inflation. They also identified energy prices as a significant external factor, particularly in the post-2008 period.

Meanwhile, Brukwicka and Dudzik (2021) provided a country-specific perspective by analyzing Poland’s inflation in 2021. The study highlighted energy price shocks, food price dynamics, and inflation expectations as the primary inflation drivers. These were exacerbated by pandemic-induced fiscal expansion and ultra-loose monetary policies. This reflects an emerging consensus that inflation expectations – particularly when unanchored – can amplify and prolong inflationary episodes (Blanchard, 2021).

Whereas, Binici et al. (2022) offered a broader post-pandemic perspective, examining 30 European countries over the period of 2002–2022. They demonstrated that although global factors (e.g., commodity prices, international interest rate cycles) continued to influence inflation, the role of national-level fiscal and monetary policies became more prominent during the pandemic. Their findings suggest that the inflationary response to global shocks varied significantly depending on institutional settings, including inflation targeting credibility and fiscal discipline.

The methodological heterogeneity across studies is another challenge in building a cohesive understanding of inflation dynamics. Studies have employed diverse techniques ranging from panel unit-root tests and cointegration analysis to wavelet methods and Bayesian models. Erdogan et al. (2020), for instance, investigated inflation determinants across 28 European countries by using a spatial econometric framework during the early COVID-19 period. Their results emphasized the importance of monetary aggregates and exchange rates, with spatial linkages further amplifying inflation shocks across countries.

While valuable, many of these studies treat Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries as a homogeneous block or as part of broader EU aggregates. This masks potential differences in inflation transmission mechanisms, monetary policy effectiveness, and structural vulnerabilities, especially in transitioning economies like those in the Visegrád group. Furthermore, few studies utilize econometric techniques that distinguish between short-run dynamics and long-run relationships, which is critical when analyzing countries undergoing structural and institutional transformation.

The inflation experience of the Visegrád countries presents a unique case for several reasons. First, despite some convergence in price levels and institutional harmonization following EU accession, inflation trajectories in these countries have been far from uniform. For example, Hungary and Poland have been facing persistent inflationary pressures since the late 2010s, while Slovakia – by virtue of having adopted the Euro – exhibits different inflation dynamics. Second, these economies exhibit varying degrees of monetary policy independence. While Czechia, Hungary, and Poland operate under inflation targeting regimes, Slovakia has ceded its monetary policy to the ECB.

Third, structural differences – such as reliance on energy imports, wage-setting institutions, and the size of the informal economy – contribute to the divergent inflationary responses to common shocks. These nuances have not been fully captured in existing literature, which often favors pooled specifications or cross-sectional analyses that assume homogeneity across countries.

This study addresses several critical gaps in the existing literature. First, it isolates the Visegrád group – which is often subsumed within broader regional studies – to provide a more detailed understanding of inflation dynamics in these four countries. Second, it employs a panel ARDL approach, which is particularly suited for examining both I(0) and I(1) variables in settings where long-run relationships and short-run dynamics may differ across units.

By using three estimators, specifically, PMG, MG, and DFE, the study allows for comparisons across methodologies that assume varying degrees of parameter homogeneity. While MG captures full heterogeneity, PMG assumes common long-run effects, and DFE restricts both long- and short-run coefficients to be equal. This is critical in assessing how inflation drivers differ across countries with shared historical trajectories but divergent economic policies.

Moreover, this study employs robust panel unit root tests (IPS, ADF, PP) and cointegration diagnostics (Kao test) in order to ensure methodological soundness. This layered approach not only provides new empirical evidence but also offers methodological guidance for future research on inflation in transitioning economies.

Upon undertaking to examine key determinants of inflation in the Visegrád countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia), we analyze yearly data from 2000–2022 by using time series and panel regressions. Annual data capture long-term relationships between inflation, fiscal policies, and economic growth, while avoiding short-term volatility. These countries constitute a uniform group with similar political and economic backgrounds and are often cited as successful transitions to market economies (Ivanová & Masárová, 2018; Bieszk-Stolorz & Dmytrów, 2020).

The analysis draws on major theories: Demand-Pull (Rudebusch & Svensson, 1999), the Monetary Theory (Friedman, 1963), Exchange Rate Pass-Through (Gagnon & Ihrig, 2004), Cost-Push (Blanchard, 1986), the Taylor Rule (Taylor, 1993), and inflation expectations (Mankiw & Reis, 2002). Fiscal influences (Romer & Romer, 2010) and global factors (Ciccarelli & Mojon, 2010) are also considered to be of importance in understanding inflation dynamics.

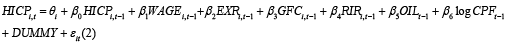

Based on these theories, a generic model for inflation can be formulated as:

HICPi, t = αi + β1WAGEi, t + β2GFCi, t + β3EXRi, t + β4RIRi, t + β5OILt + β6GPFt + β7DUMMY + εi, t (1)

i = 1, ... N, t = , ...T

where:

HICP – Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices in the country i and in period t;

WAGE – Average annual wages Constant prices in the country i in period t;

GFC – General government final consumption expenditure (% of GDP) in the country i in period t;

EXR – Exchange Rate Regime in the country i and in period t;

RIR – Real Interest Rates in the country i and in period t;

OIL – Brent Crude Oil price in period t (transformed in logarithm);

GPF – Index of Global Food Prices in period t (transformed in logarithm);

β1– parameters to be estimated;

αi – random effect;

εi, t– standard error.

The Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) is commonly used as the dependent variable in inflation studies, reflecting the general price level (Staehr, 2010). While some studies use GDP deflator changes (Alfaro, 2005) or money value depreciation rates (Chrigui et al., 2011), the HICP, compiled by Eurostat, offers a more accurate measure for international comparisons (Petkovski et al., 2024). Logarithmic transformations of the inflation rate (logINF) are often employed to mitigate outliers and non-linearities (Catao & Terrones, 2005).

Wage growth, a key component of cost-push inflation, affects purchasing power and inflation dynamics. Studies show mixed results on the wage-inflation relationship, with some suggesting a leading role for prices (Chang & Emery, 1996), while others find no causal link (Hess and Schweitzer, 2000). In the Visegrád countries, understanding wage growth is crucial for managing inflation.

The Exchange Rate Pass-Through theory highlights how exchange rate regimes impact import prices and inflation (Gagnon & Ihrig, 2004). Domestic currency depreciation will increase import prices, which, in turn, will increase the inflation from rising prices of imported goods in domestic currency. The effect of domestic currency appreciation can reduce import prices and inflation, but, with a non-identical effect size, allowing asymmetric exchange rate pass-through (Arintoko et al., 2024)

Guided by the Taylor Rule, real interest rates are pivotal in shaping inflation (Taylor, 1993). Low or negative real rates encourage borrowing and spending, thereby potentially increasing inflation, while high rates dampen demand and inflation. According to a recent article authored by Ahmić and Isović (2023), which examines shifts in the European Union’s monetary policy conducted by the European Central Bank, it is underscored that there has been a rise in interest rates aimed at curbing the upward movement of inflation’s core rates. For the Visegrád countries, managing real rates is critical for balancing growth and inflation control. The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level posits fiscal policies, rather than monetary ones, shape inflation (Woodford, 2003). The Ricardian Equivalence Theory suggests that government spending may not cause inflation if future tax expectations lead to higher savings (Barro, 1979).

The energy and food crises are characterized by soaring world energy and food prices due to limited supply, which can then increase the burden on the household income (Guan et al., 2023). Cost-push inflation is also affected by oil prices (Dua & Goel, 2021), whereas global food price trends can influence domestic inflation (Ciccarelli & Mojon, 2010). In other words, we included oil prices in the model due to their strong theoretical and empirical justification as an exogenous driver of inflation, especially in small open economies. Their inclusion allows us to capture the impact of global supply shocks, even though they are not part of the cointegrating relationship in the strictest sense.

A dummy variable for 2022–2023 accounts for inflationary effects of geopolitical events, such as the war in Ukraine, on energy and food prices.

The data in use in this paper have been obtained from various sources such as the World Development Indicators (WDI) database, AMECO database of the European Commission classification of exchange rate regime developed by Ilzetzki et al. (2022), Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Trading economics and oecd.stat. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for all the variables used in the regressions.

|

Variables |

Symbol |

Units |

Source |

|

Harmonized index of consumer prices |

HICP |

2015=100 |

World Development Indicators |

|

Average annual wages |

WAGE |

Constant prices |

oecd.stat |

|

Exchange rate regime |

EXR |

Classification code of various exchange regimes |

Ilzetzki et al., 2022 |

|

General government final consumption expenditure |

GFC |

(% of GDP) |

World Development Indicators |

|

Real interest rates |

RIR |

(percent %) |

World Development Indicators |

|

Brent Crude oil |

OIL |

(dollar $) |

Trading economics |

|

Index of Global Food Prices |

GPF |

Index 2016=100 |

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis |

We also present descriptive statistics for all countries, and we additionally discuss the main trends in the evolution of the selected variables over time.

|

|

HICP |

WAGE |

EXR |

GFC |

RIR |

OIL |

GPF |

|

Mean |

95.14 |

48.50 |

7.95 |

19.64 |

2.61 |

63.57 |

99.17 |

|

Median |

98.00 |

48.50 |

8.00 |

19.56 |

2.38 |

59.92 |

102.31 |

|

Maximum |

161.55 |

96.00 |

12.00 |

23.01 |

19.00 |

111.11 |

136.47 |

|

Minimum |

6.70 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

17.14 |

-4.17 |

19.90 |

57.54 |

|

Observations |

96 |

96 |

96 |

96 |

94 |

96 |

96 |

Summary statistics for all variables used in the analysis, as presented in Table 2, demonstrate considerable heterogeneity across the countries under consideration and over time.

|

|

HICP |

WAGE |

EXR |

GFC |

RIR |

OIL |

GPF |

|

HICP |

1.00 |

0.38 |

-0.33 |

-0.17 |

-0.50 |

0.47 |

0.72 |

|

WAGE |

0.38 |

1.00 |

0.49 |

-0.10 |

-0.01 |

0.15 |

0.32 |

|

EXR |

-0.33 |

0.49 |

1.00 |

-0.04 |

0.51 |

-0.14 |

-0.35 |

|

GFC |

-0.17 |

-0.10 |

-0.04 |

1.00 |

-0.08 |

-0.18 |

-0.11 |

|

RIR |

-0.50 |

-0.01 |

0.51 |

-0.08 |

1.00 |

-0.12 |

-0.43 |

|

OIL |

0.47 |

0.15 |

-0.14 |

-0.18 |

-0.12 |

1.00 |

0.70 |

|

GPF |

0.72 |

0.32 |

-0.35 |

-0.11 |

-0.43 |

0.70 |

1.00 |

Before analyzing the regression panel model, a correlation matrix was formed between the dependent and the independent variables, and an analysis of Pearson’s correlation coefficients was carried out. Namely, we estimate the correlation between selected determinants to check for possible problems of multicollinearity between them. We have a multicollinearity problem if the correlation between selected determinants is above 0.80 (cf. Gujarati & Porter, 2009), and simultaneous inclusion of the variable in the model should be avoided. According to the results listed in Table 3, there are no multicollinearity problems between the selected determinants.

This study analyzes inflation dynamics in the Visegrád countries (Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland) by using panel ARDL models. Panel data enable testing those assumptions which cross-sectional analyses may overlook (Maddala & Wu, 1999). Stationarity is assessed via IPS, ADF, and PP tests, followed by the Kao cointegration test so that to confirm long-run relationships.

The ARDL approach, suitable for variables integrated at I(0) and I(1) (Pesaran & Shin, 1997), employs three estimators: Pooled Mean Group (PMG), Mean Group (MG), and Dynamic Fixed Effect (DFE). PMG assumes common long-run relationships but allows short-run heterogeneity, while MG captures full cross-country differences (Pesaran & Smith, 1995). DFE imposes uniformity across panels.

The Hausman test guides estimator selection. Overall, this study underscores the need for tailored econometric methods to reflect the complex inflation processes in these transitioning economies.

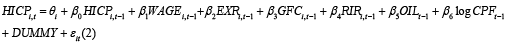

The MG model for testing a long-run relationship between variables is defined as follows:

Equation (2) shows that the MG estimator with a high order of lag that can estimate long-run average parameters consistently. The MG estimator introduced by Pesaran and Shin (1999) has standard features between the MG estimator and the DFE estimator. The MG estimator can estimate long-run and short-run coefficients for each country, while the DFE estimator can only estimate the overall short-run and long-run coefficients. Besides, the PMG estimator cannot estimate long-run coefficients for each country.

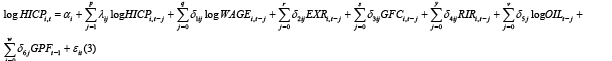

The long-run relationship models, estimated by using the PMG and DFE approaches, illustrate the impact of each variable over time, as presented in Equation (3):

In these models, i represents the number of countries (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4), t represents the number of years, i.e., the temporal scope of analysis (e.g., 2000–2023), whereas the country-specific effects are denoted by αi, and εit refers to the error terms.

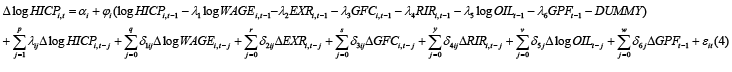

For the short-run relationship, an error correction model (ECM) is used as shown in Equation (4).

In this model, λi represents the long-run parameters, and φi is the parameter for the error-correction term, which measures the speed of adjustment to the long-term equilibrium of HICP due to changes in WAGE EXR GFC RIR OIL and GPF. A negative and significant value of φi refers to the existence of a long-run co-integrating relationship among HICP WAGE EXR GFC RIR OIL and GPF. The ECM dynamics allow for free variation of short-run terms, ensuring consistent and asymptotically normal parameter estimates for both stationary and non-stationary regressors (I(1)).

The first step of our empirical analysis is to perform panel unit root tests (Table 4). As already mentioned in the previous section, we applied panel-IPS unit root tests and Fisher-type tests by using ADF and PP-test, as outlined by Maddala and Wu (1999).

|

Variables |

Im, Pesaran and Shin W-stat |

ADF-Fisher Chi-square |

PP-Fisher Chi-square |

Conclusion |

|||

|

At a level of |

First differentiation |

At a level of |

First differentiation |

At a level of |

First differentiation |

||

|

HICP |

3.35 |

-2.08*** |

8.82 |

23.4*** |

0.58 |

45.4*** |

I(1) |

|

WAGE |

0.3 |

-2.92*** |

3.63 |

23.1*** |

9.87 |

70.2*** |

I(1) |

|

EXR |

0.91 |

-2.09*** |

2.97 |

16.58*** |

2.99 |

38.61*** |

I(1) |

|

GFC |

-1.24 |

-1.91*** |

11.7 |

16.08*** |

9.46 |

14.63*** |

I(1) |

|

RIR |

0.44 |

-3.61*** |

6.64 |

28.2*** |

23.6 |

45.7*** |

I(1) |

|

OIL |

-1.59** |

-3.79*** |

13.27 |

28.9*** |

13.6 |

66.2*** |

I(1) |

|

GPF |

0.06 |

-5.43*** |

5.20 |

42.2*** |

3.50 |

62.1*** |

I(1) |

As we can see from Table 4, HICP WAGE EXR GFC RIR OIL and GPF were stationary at first differentiation. Next, we continue with the cointegration test, whose results are presented in Table 5.

|

|

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

|

ADF |

-4.3005 |

0.0000 |

|

Residual variance |

102.47 |

|

|

HAC variance |

71.95 |

The p-value of 0.0012 is less than the 0.05 threshold, thereby indicating that we can reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration. This suggests that there is a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables in our model.

Keeping in mind that all determinants in all models are co-integrated, in the next step, we evaluate and interpret the results of panel PMG, MG and DFE estimators. The results are presented in Table 6.

The Hausman tests comparing PMG vs. MG and MG vs. DFE both yield p-values of 0.000, rejecting the null hypothesis that PMG or DFE estimators are consistent and efficient. Thus, the MG model is preferred, as it allows for full heterogeneity in both short- and long-run coefficients, accommodating differences in economic structures and inflation responses across the Visegrád countries (Pesaran & Smith, 1995).

The MG model results for the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) provide important insights. The long-run wage growth coefficient (0.407***) confirms a strong link between wages and inflation, which is consistent with demand-pull inflation theories (Blanchard & Galí, 2007). Wage dynamics are particularly relevant in these transitioning economies, where rising incomes fuel consumption (Krause & Lubik, 2007).

|

Variable |

PMG |

MG |

DFE |

|||

|

Long Run |

Short run |

Long Run |

Short run |

Long Run |

Short run |

|

|

LWAGE |

0.186*** (0.0073) |

0.631 (0.549) |

0.407*** (0.110) |

0.183 (0.218) |

0.465*** (0.077) |

0.569*** (0.235) |

|

LEXR |

0.080** (0.043) |

0.156 (0.122) |

-0.040 (0.226) |

0.224 (0.144) |

0.125*** (0.048) |

0.134 (0.111) |

|

GFC |

-0.006 (0.012) |

-0.008*** (0.001) |

-0.033*** (0.004) |

-0.081*** 0.043 |

-0.086*** (0.023) |

0.041 (0.044) |

|

RIR |

-0.004*** (0.0001) |

-0.003 (0.003) |

-0.009 (0.007) |

0.002 ( 0.002) |

-0.001 (0.001) |

-0.001 (0.002) |

|

LOIL |

0.023 (0.028) |

0.159 (0.160) |

0.104 ( 0.150) |

0.211 ( 0.202) |

0.007 (0.101) |

0.024 (0.132) |

|

GPF |

0.002*** (0.0001) |

-0.002 (0.003) |

0.001*** (0.002) |

-0.003 (0.004) |

0.003 (0.002) |

0.001 (0.003) |

|

DUMMY |

4.998*** (1.041) |

0.631 (0.549) |

0.438*** (0.160) |

0.361 (0.465) |

0.130 (0.084) |

0.203 (0.132) |

|

Constant |

-2.049 (1.758) |

-0.361 (0.465) |

-6.336*** (1.083) |

|||

|

Error Correction |

0.526 (0.438) |

1.554*** (0.133) |

0.416 (0.633) |

|||

|

Hausman test (p-value) |

0.000 |

0.017 |

||||

The positive global price factor coefficient (0.002***) highlights the impact of international commodity prices on domestic inflation, reflecting openness to global supply shocks (Kaldor, 2016). The negative GFC coefficient (-0.033***) suggests that productive government spending can ease inflationary pressures by enhancing capacity (Baldacci & Kumar, 2010).

A large positive coefficient (4.998***) on the war dummy variable indicates the sharp inflationary impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, thus echoing Guriev and Mian’s (2022) findings on geopolitical disruptions.

In the short run, the wage growth coefficient (0.183) shows a weaker immediate effect as firms partially absorb costs (Dornbusch & Fischer, 2005). The short-run insignificance of GPF (-0.003) suggests delays in passing global price changes to consumers, which is consistent with price stickiness (Mankiw, 2001). Similarly, the small negative coefficient of GFC (-0.002) implies that fiscal effects on inflation take time to materialize.

The short-run coefficient of the war dummy (0.631) reflects an initial but less pronounced impact, though persistent uncertainty continues to affect expectations.

While the panel approach leverages similarities among these countries, their differences remain significant. Notably, Slovakia belongs to the Eurozone; Hungary has continued energy purchases from Russia; and Poland, with a much larger, more diversified economy, faces unique dynamics. Upon recognizing this heterogeneity, Table 7 reports results by country to account for these variations more accurately.

|

Long-run estimation |

|||||||

|

Countries |

WAGE |

EXR |

GFC |

RIR |

OIL |

GPF |

DUMMY |

|

Czech Republic |

0.398 (0.325) |

0.089 (0.157) |

-0.040 (0.034) |

-0.001 (0.001) |

0.099 (0.119) |

0.003* (0.002) |

0.514 (0.276) |

|

Hungary |

0.484*** (0.129) |

-0.550** (0.308) |

-0.039 (0.051) |

0.001 (0.001) |

0.019 (0.117) |

0.003 (0.002) |

0.276** (0.099) |

|

Poland |

0.110 (0.139) |

-0.214 (0.270) |

-0.019 (0.024) |

0.0035*** (0.0006) |

0.017 (0.046) |

0.003 (0.001) |

0.111 (0.033) |

|

Slovakia |

0.638*** (0.286) |

0.514*** (0.197) |

-0.033 (0.098) |

0.033*** (0.014) |

0.552 (0.429) |

0.006 (0.014) |

1.744 (1.188) |

|

Short-run estimation |

|||||||||

|

Countries |

Error Correction |

WAGE |

EXR |

GFC |

RIR |

OIL |

GPF |

DUMMY |

Constant |

|

Czech Republic |

-0.291 (0.235) |

0.075*** (0.034) |

0.005 (0.027) |

-0.007 (0.005) |

-0.0001 (0.0003) |

0.010 (0.021) |

0.0001 (0.0007) |

0.150*** (0.050) |

1.135 (1.026) |

|

Hungary |

-0.828 (0.627) |

-0.222 (0.227) |

0.095 (0.323) |

0.020 (0.040) |

0.0006 (0.001) |

0.028 (0.062) |

-0.0006 (0.001) |

0.229** (0.121) |

3.655 (3.457) |

|

Poland |

0.734*** (0.122) |

0.270*** (0.049) |

0.1483 (0.146) |

-0.020 (0.015) |

0.0005*** (0.0002) |

0.012 (0.019) |

0.002*** (0.0006) |

0.082*** (0.035) |

-3.495*** (0.554) |

|

Slovakia |

2.050*** (0.371) |

0.761 (1.240) |

0.650 (0.491) |

0.173 (0.243) |

0.009 (0.035) |

0.818 (0.719) |

-0.016 (0.022) |

1.744 (1.188) |

-4.776 (6.053) |

In the long run, the Global Food Price (GPF) and wage coefficients are positive but statistically insignificant, indicating only a limited influence on inflation. While rising wages may fuel inflation (Galgóczi, 2017), other factors like productivity or monetary policy could offset this impact. In the short run, wage effects are significant (0.075), thus supporting the presence of a wage-price spiral (Égert, 2017). A significant dummy variable (0.150) implies that structural factors also affect inflation (Krešič et al., 2020). Exchange rate and government consumption are not significant, which points to institutional resilience against external shocks.

Wages have a strong and significant long-run impact on inflation (0.484), thus confirming wage-push dynamics (Bénassy-Quéré et al., 2018). A marginally significant negative exchange rate coefficient (-0.5505) suggests that currency appreciation lowers imported inflation (Kovács, 2016). Short-run wage effects are negative but insignificant, possibly due to short-term frictions (Bátora & Driessen, 2019). The significant dummy (0.276) hints at structural or policy shifts (Huszar, 2020). Other variables, such as government consumption and oil prices, lack significance.

The long-run real interest rate has a small positive effect (0.0035), which contradicts theory but is consistent with studies suggesting that rate hikes may signal inflation expectations or trigger distributional effects (Brzoza Brzezina, 2002; ECB, 2018). Government purchases also positively influence inflation (0.003) (Gornicki, 2018). Significant short-run wage effects (0.270) indicate that rising labor costs feed into prices (Piątkowski, 2019). The dummy variable (0.111) reflects structural or external shocks (Sztandar-Sztanderska, 2017). Exchange rate and oil price impacts are negligible.

Wages (0.638) and exchange rate (0.514) have strong positive long-run impacts on inflation. These results highlight the role of domestic demand and imported inflation, especially under Eurozone conditions (Deutsche Bundesbank, 2020). A positive real interest rate effect (0.033) suggests that borrowing costs may raise prices (Klein, 2021). Government consumption and oil prices are insignificant. Across the Visegrád countries, wages consistently influence inflation, while the effects of exchange rates, interest rates, and structural variables vary. These divergences reflect each country’s unique economic structure, thereby underscoring the need for tailored inflation control policies.

To empirically evaluate the proposed hypotheses, the analysis draws on pooled estimators (PMG, MG, and DFE), allowing for both long-run homogeneity and short-run heterogeneity across the Visegrád countries. The findings highlight that inflation persistence in the region is driven by a combination of external shocks, domestic policies, and institutional factors.

Hypothesis 1 posits that the ECB’s delayed monetary tightening contributed to more persistent inflation in Slovakia compared to its peers. The long-run coefficient on wage growth (0.407***) confirms a strong inflationary effect, particularly in Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland. These findings are consistent with the Phillips Curve (Friedman, 1968) and recent studies that link tight labor markets to price pressures (Darvas & Wolff, 2021). Wage indexation and centralized bargaining in Slovakia and Hungary intensified pass-through effects, while the Czech Republic’s more flexible labor market and inflation-targeting regime moderated this link. A 10% rise in real wages results in an estimated 4 percentage point (pp) inflation increase in Hungary, compared to 2 pp in Czechia.

Hypothesis 2 examines whether independent monetary policies were more effective in mitigating inflation. Evidence supports this, as countries with autonomous policy tools, particularly the Czech Republic, demonstrated more timely interest rate responses and lower exchange rate pass-through (ERPT). Slovakia, bound by the ECB’s common monetary stance, experienced delayed reactions. Notably, ERPT is significant in Hungary and Slovakia, but muted in Poland and Czechia, aligning with Burstein and Gopinath (2014), who find that credible inflation-targeting regimes dampen exchange-rate effects.

Hypothesis 3 addresses the role of external shocks. The long-run significance of global price variables substantiates the hypothesis that energy prices and supply chain disruptions were stronger inflation drivers than domestic policies. The inflationary impact of the Ukraine war (dummy coefficient: 4.998***) underscores this. Hungary and Poland, with their greater dependence on Russian energy, were most affected. Bachmann et al. (2022) also affirm the inflationary transmission of geopolitical shocks. A 50% energy price increase is estimated to raise inflation by 1.5–2 pp over 6–12 months.

Hypothesis 4 centers on Slovakia’s Euro area membership and the resulting inflation dynamics. The constrained monetary autonomy under ECB policy – characterized by a slower tightening cycle in 2022 – limited Slovakia’s ability to react to inflation surges. In contrast, the Czech National Bank raised rates early, thus curbing inflation more effectively. These structural differences validate the divergent inflation paths across the V4 countries.

Hypothesis 5 relates to country-specific characteristics such as fiscal frameworks and labor market structures. The significant negative coefficient on government spending (-0.033***) suggests that productive fiscal expenditures, and particularly capital investment, can reduce inflation by crowding in private activity (Auerbach & Gorodnichenko, 2012). Real interest rates correlate positively with inflation in Poland and Slovakia, likely due to policy lags and reverse causality (Taylor, 1993), as hikes followed inflation surges rather than preempting them.

In conclusion, while external shocks explain shared inflationary pressures, institutional and monetary regime differences are key to understanding divergent inflation persistence in the Visegrád region. These findings emphasize the importance of policy flexibility, fiscal effectiveness, and energy diversification in addressing inflation in heterogeneous monetary environments.

The empirical results offer several critical insights into inflation dynamics across the Visegrád countries. The selection of the Mean Group (MG) estimator – based on Hausman tests – highlights the necessity of allowing full heterogeneity in both long-run and short-run relationships. This modeling choice reflects the differing economic structures, monetary regimes, and external exposures in these transitioning economies.

The strong long-run relationship between wage growth and inflation across most countries supports classical demand-pull and wage-push inflation theories (Blanchard & Galí, 2007). This is particularly relevant for economies undergoing structural transformation, where wage growth often outpaces productivity improvements, contributing to inflationary pressures. In the short run, however, the muted wage effect aligns with theories of price stickiness and cost absorption by firms (Mankiw, 2001).

Global commodity prices exert significant long-run influence, especially in open economies like Hungary and Slovakia. This confirms previous findings that inflation in small, open economies is increasingly shaped by external supply shocks (Binici et al., 2022). However, the lagged or insignificant short-run effects suggest that transmission is gradual, and that it filters through domestic price-setting behavior.

Interestingly, the study identifies a large inflationary impact associated with geopolitical disruptions, specifically, the war in Ukraine. This aligns with Guriev and Mian’s (2022) work and emphasizes the importance of non-economic shocks in shaping inflation expectations and market behavior.

Country-level differences further validate the heterogeneous panel approach. For example, the significance of exchange rate movements in Hungary and Slovakia contrasts with their limited role in Czechia and Poland. Similarly, the positive inflation response to the real interest rates in Poland and Slovakia contradicts the conventional expectations, possibly reflecting expectation effects or structural rigidities (Brzoza-Brzezina, 2002).

These results highlight the limits of a one-size-fits-all monetary policy. While inflation-targeting frameworks remain relevant, their effectiveness is contingent on institutional credibility, policy coordination, and external vulnerabilities. Importantly, the findings contribute to the broader literature by demonstrating that, even within a geographically and historically aligned group, inflation processes remain deeply country-specific.

This study examines inflation dynamics in the Visegrád countries – Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia – from 2000 to 2023 by using the Mean Group estimator to capture country-specific long- and short-run effects. Our findings highlight how wages, global prices, and government consumption shape inflation, thus reflecting structural and institutional differences.

Wage growth is a clear long-term inflation driver, especially in Poland and Hungary, where pay increases have outpaced productivity. Aligning wages with productivity is essential to prevent persistent demand-pull inflation. In contrast, Slovakia and the Czech Republic show more moderate wage dynamics, which implies lower domestic inflationary risks.

Global price shocks, notably in energy, are significant inflation sources across all four economies. Slovakia’s Eurozone membership limits its monetary policy flexibility, while increasing reliance on fiscal measures and energy diversification. Hungary’s independent monetary policy allows more active interventions but has yielded mixed results due to policy lags and credibility challenges.

Government consumption has a dual impact: it fuels inflation in the short term when tied to current spending but stabilizes prices over time when invested productively. This underscores the need to shift fiscal priorities toward infrastructure and innovation so that to strengthen supply-side capacity and contain structural inflation pressures.

Since 2020, especially after the outbreak of the Ukraine war, inflation expectations have grown and become more volatile, thus exposing gaps in policy coordination and forecasting. This period reinforces the urgency of improving institutional frameworks and adopting forward-looking strategies.

However, the study has limitations. It does not fully capture structural breaks during major crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or the year 2022 energy shock. While the MG estimator reflects cross-country heterogeneity, it does not account for spillover effects or interconnectedness among the Visegrád economies. Additionally, micro-level factors like firm pricing behavior or household expectations remain unexplored.

Overall, inflation in the Visegrád region results from intertwined domestic pressures, external shocks, and diverse institutional arrangements. Effective management will require tailored policies that align wages and productivity, reduce dependence on volatile global prices, and target government spending toward long-term competitiveness. Future research should integrate real-time monitoring and microeconomic drivers with the objective to equip policymakers with timely, adaptable tools to maintain price stability.

Ahmić, A., & Isović, I. (2023). The impact of regulatory quality on deepens level of financial integration: Evidence from the European Union countries (NMS-10). ECONOMICS-Innovative and Economics Research Journal, 11(1), 127-142. https://doi.org/10.2478/eoik-2023-0004

Arce, Ó., Ciccarelli, M., Kornprobst, A., & Montes-Galdón, C. (2023). What caused the euro area post-pandemic inflation? ECB Occasional Paper Series, 343.

Arintoko, A., Badriah, L.S. and Kadarwati, N. (2024) “The Asymmetric Effects of Global Energy and Food Prices, Exchange Rate Dynamics, and Monetary Policy Conduct on Inflation in Indonesia”, Ekonomika, 103(2), pp. 66–89. doi:10.15388/Ekon.2024.103.2.4.

Arratibel, O., & Michaelis, H. (2013). The impact of monetary policy and exchange rate shocks in Poland. ECB Working Paper No. 1636.

Auerbach, A. J., & Gorodnichenko, Y. (2012). Measuring the output responses to fiscal policy. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4(2), 1–27. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.4.2.1

Baba, C., Duval, R., Lan, T., & Topalova, P. (2023). The inflation surge in Europe. IMF Working Paper, WP/23/30.

Bachmann, R., Baqaee, D., & Wolf, C. (2022). The war in Ukraine and inflation dynamics. NBER Working Paper No. 30117. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30117

Baldacci, E., & Kumar, M. S. (2010). Fiscal deficits, public debt, and growth in the long run. Journal of International Money and Finance, 29(8), 1468-1482.

Binici, M., Kara, H., & Özlü, P. (2022). The post-pandemic inflation dynamics in Europe: Global or domestic factors? Economic Modelling, 116, 105982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2022.105982

Bieszk-Stolorz, B., & Dmytrów, K. (2020). Influence of accession of the Visegrad group countries to the EU on the situation in their labour markets. Sustainability, 12(16), 1-16.

Blanchard, O. J. (1986). The wage price spiral. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 101(3), 543-565.

Blanchard, O. (2021). In defense of concerns about inflation. Peterson Institute for International Economics. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/defense-concerns-about-inflation

Blanchard, O., & Galí, J. (2007). The macroeconomic effects of oil price shocks: Can policy make a difference? Macroeconomic Dynamics, 11(1), 1-14.

Broż, L., & Kočenda, E. (2017). Inflation convergence in the European Union: Empirical evidence. Journal of International Money and Finance, 70, 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2016.08.006

Brukwicka, I., & Dudzik, I. (2021). Causes and effects of inflation in Poland. VUZF Review, 6(3), 119-125. https://doi.org/10.38188/2534-9228.21.3.13.

Brzoza-Brzezina, M. (2002). The Relationship between Real Interest Rates and Inflation. NBP Working Paper No. 23.

Burstein, A., & Gopinath, G. (2014). International prices and exchange rates. Handbook of International Economics, Vol. 4, 391–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-54314-1.00007-0

Čaklovica, K., & Efendic, A. (2020). Determinants of inflation in Europe: A dynamic panel approach. Economic Review – Journal of Economics and Business, 18(1), 49–64.

Chang, C. P., & Emery, K. M. (1996). Do wages help predict inflation? Economic and Financial Policy Review, Q1, 2-9.

Ciccarelli, M., & Mojon, B. (2010). Global inflation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(3), 524-535.

Coibion, O., & Gorodnichenko, Y. (2015). Information rigidity and the expectations formation process: A review of recent developments. In Handbook of Economic Expectations. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21092

Darvas, Z., & Wolff, G. B. (2021). Labour market slack and wage dynamics in the euro area. Bruegel. https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/labour-market-slack-and-wage-dynamics-euro-area

Dornbusch, R., & Fischer, S. (2005). Macroeconomics (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Dua, P., & Goel, D. (2021). Determinants of inflation in India. The Journal of Developing Areas, 55(2).

ECB. (2018). Monetary policy and household inequality. ECB Working Paper No. 2170.

Eberhardt, M., & Teal, F. (2011). Econometrics for grumblers: A new look at the literature on cross-country growth empirics. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25(1), 109–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00610.x

Égert, B., & Kočenda, E. (2014). The impact of oil prices on inflation: Evidence from advanced and emerging economies. Energy Economics, 44, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2013.10.008

Erdogan, S., Yıldırım, D. Ç., & Gedikli, A. (2020). Monetary transmission and inflation in the EU: A spatial approach. The European Journal of Comparative Economics, 17(2), 277–298.

Friedman, M. (1963). Inflation: Causes and consequences. Asia Publishing House, New Delhi.

Fröhling, A., & Gornicka, L. (2020). Wage dynamics and inflation in CEE. ECB Working Paper No. 2488.

Gagnon, J. E., & Ihrig, J. (2004). Monetary policy and exchange rate pass-through. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 9(4), 315-338.

Galí, J., & Gertler, M. (1999). Inflation dynamics: A structural econometric analysis. Journal of Monetary Economics, 44(2), 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(99)00023-9

Gnocchi, S., & Pappa, E. (2022). Do wages lead prices? Evidence from the euro area. European Economic Review, 144, 104176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104176

Guan, Y., Yan, J., Shan, Y., Zhou, Y., Hang, Y., Li, R., Liu, Y., Liu, B., Nie, Q., Bruckner, B., Feng, K., & Hubacek, K. (2023). Burden of the global energy price crisis on households. Nature Energy, 8, 304-316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-023-01209-8

Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Basic econometrics (5th ed.). McGraw Hill Inc., New York.

Guriev, S., & Mian, A. (2022). Geopolitical risks and inflation. Economics of Transition and Institutional Change.

Hess, G. D., & Schweitzer, M. (2000). Does wage inflation cause price inflation? FRB of Cleveland Policy Discussion Paper, 1.

Ilzetzki, E., Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2022). Rethinking exchange rate regimes. Handbook of International Economics, 6, 91-145.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2023). Fiscal policy and inflation in emerging Europe (Working Paper No. WP/23/21). https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/01/24/Fiscal-Policy-and-Inflation-in-Emerging-Europe-528507

Ivanová, E., & Masarova, J. (2018). Performance evaluation of the Visegrad group countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 31(1), 270-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2018.1429944.

Kjosevski, J., & Petkovski, M. (2017). Non-performing loans in Baltic states: Determinants and macroeconomic effects. Baltic Journal of Economics, 17(1), 25-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1406099X.2016.1246234.

Krause, M. U., & Lubik, T. A. (2007). The transmission of monetary policy in a low inflation environment. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 31(8), 2722-2742.

Maddala, G. S., & Wu, S. (1999). A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(S1), 631-652. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.61.s1.13.

Nagy, S., & Tengely, A. (2018). Determinants of inflation in Hungary: A structural approach. Economic Review, 65(7–8), 769–790.

Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1997). An autoregressive distributed lag modeling approach to cointegration analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1999). Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94(446), 621–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1999.10474156

Pesaran, M. H., & Smith, R. (1995). Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 79–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01644-F

Petkovski, M., Kjosevski, J., Stojkov, A., Petkovska, K. B: (2024) Examining Country-specific and Global Factors of Inflation Dynamics: The Curious Case of Baltic States. Politická ekonomie, 72(6), 896–992. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.polek.1444

Shaji, S., Varman, P. M., & Karunakaran, N. (2024). Macroeconomic determinants of inflation in Asian inflation-targeting nations: An empirical panel data analysis. MSW Management - Multidisciplinary, Scientific Work and Management Journal, 34(2), 90-108.

Taylor, J. B. (1993). Discretion versus policy rules in practice. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 39, 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2231(93)90009-L

Ujkani, X., & Atdhetar, G. (2023). Determinants of the inflation rate: Evidence from panel data. Economics – Innovative and Economics Research Journal, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.2478/eoik-2023-0054

Woodford, M. (2003). Interest and prices: Foundations of a theory of monetary policy. Princeton University Press.