Jaunųjų mokslininkų darbai eISSN 1648-8776

2025, vol. 55, pp. 8–17 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/JMD.2025.55.1

Techniques for Handling Challenging Student Behaviour in Language Learning Classrooms

Mokinių probleminio elgesio kalbų pamokose sprendimo būdai

Mahammad Hasanov

Queen Morta school

e-mail hesenovmehemmed1998@gmail.com

Summary. Despite the numerous studies conducted on the positive discipline techniques in addressing misbehaviour in the classroom, a significant gap remains in our understanding of how these challenges and their associated techniques differ based on the specific classroom environment and the subject. This article aims to identify the common causes of misbehaviours in the foreign language classrooms and teachers’ response and techniques to deal with these challenges by maintaining positive discipline. The present study was conducted in the context of a workshop that involved eight foreign language teachers at a private school. The workshop was discussion based, and participants shared their challenges and techniques to deal with them accordingly. The research methodology applied was qualitative, with content analysis and the usage of inductive coding to analyse the data gathered from the workshop. The findings of the study indicate that the most prevalent causes of problematic behaviour in foreign language classrooms are academic challenges, attention seeking, and individual needs. The strategies employed to address these challenges include active engagement, personal talks, positive reinforcement, and classroom rules reminders.

Key words: Positive discipline techniques, foreign language classroom, causes of misbehaviour, teacher responses, classroom management.

Received: 2025-01-10. Accepted: 2025-04-13

Copyright © 2025 Mahammad Hasanov. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Challenging behavioural problems have caused a lot of stress for both educators and pupils (Parsonson, 2012). Especially within a foreign language learning environment, this challenge can be more complex due to facts such as proficiency level of students, diverse learner groups, and individual needs. When these challenges are not properly addressed, this can lead to problems such as teachers’ burnout and ineffective learning environment. To address these challenges, myriad classroom techniques are required to be applied. This paper aims to identify the main causes of the student’s misbehaviour in the foreign language classroom setting and the teacher’s techniques and responses to these challenges.

There has been quite a few research on the handling of students’ misbehaviour in the classroom. However, most of these studies have focused on general classroom settings rather than specific classrooms such as science classrooms or language classrooms. Debreli, Ishanova, and Sheppard (2019) argue that student misbehaviour is a very broad term and can be different in different classroom settings. For example, the environment of the science classroom, which is mostly lab-based, may face different student disruptions in comparison with foreign language classroom settings. As a result, the definition of student misbehaviour is very dependable on the setting.

In the classroom settings, causes of misbehaviours are generally categorised in two distinct groups: student-dependent and conditionally independent causes. Student-dependent causes are referred to as the actions of the students which are triggered by internal factors such as students’ emotional challenges, academic difficulties, lack of motivation, or special needs. Conditionally independent causes are mostly external factors, which impact the students’ behaviour. In this category, factors such as classroom environment, methods or techniques applied by the teacher, or unclear expectations within the ecology can trigger misbehaviour.

Student-Dependent Causes

There are several potential reasons why students misbehave in foreign language classrooms. One of the reasons could be linked to the difficulty of the language or academic challenges. For example, a study by Muharremi (2014) shows that students misbehave or refuse to do tasks in German language classrooms because they find the language very difficult. Another study presented by Benaissi (2021) provides results that one of the main reasons for misbehaviour in the foreign language classroom is related to the proficiency level of the students’ language. Students with lower levels of language proficiency show indifference and become reluctant in classrooms.

Conditionally Independent Causes

Another interesting cause presented in the study by Cabaroğlu and Altınel (2010) is linked to boredom. Students interviewed during the study highlighted that their misbehaviour is related to boring lessons which can result in attention-seeking behaviour. From this study, it is obvious that students who find language classes too easy are also most likely to misbehave. Similarly, a study by Shamnadh and Anzari (2019) indicates that in classroom settings, students mostly misbehave or become distracted due to a lack of interest in the subject. The same study highlights the importance of the classroom environment and its impact on students’ behaviours. Specifically, in language classrooms, students often seek visuals to comprehend language better. A lack of necessary tools and visuals may result in boredom and distractive behaviour in the classroom environment (Shamnadh &Anzari, 2019).

According to the study by Wangdi and Namgyel (2022), there is a lack of research on how intervention techniques help to reduce misbehaviour specifically in foreign language classrooms. As stated before, most of the research has focused on the general classroom setting. There are various intervention strategies that can be followed to manage the disruptive behaviour in foreign language classrooms. For example, Wangdi and Namgyel (2022) suggest that by applying strategies such as praising, motivating, establishing good relationships with the students, and arranging a good seating plan may help educators to deal with the misbehaviour. Another study conducted by Yasin, Mustafa, and Bina (2022) suggests three classroom management techniques: seat arrangement, engagement, and participation. The study proposes six types of seating arrangement in the English classrooms. The location of the teacher and students has had an impact on the classroom management. Not having enough space for the teacher to walk around the classroom has increased the students’ distractions in the classroom (Yasin, Mustafa, &Bina, 2022). The second management strategy proposed by the study is engagement. The study suggests various types of engagement including cognitive engagement, behavioural engagement, academic engagement, etc. The study defines engagement as a process, in which pupils are in two categories: students (just participants without learning) and learners, who are literally learning. The aim of the strategy is to reinforce the students to engage with the learners (Yasin, Mustafa, & Bina, 2022). The last strategy is participation. The study defines participation as a process, in which students are all involved in the learning process in the given setting. The study proposes 4 types of participation: teacher talk, classroom talk, learner-managed talk, and turn-taking organisation (Yasin, Mustafa, & Bina, 2022). These techniques can be better explained by the perspective of Socio-Cultural theory, where one of the key concepts is Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) (McCaslin, Bozack, Napoleon, Thomas, Vasquez, Wayman, & Zhang, 2006). According to researchers (McCaslin et al., 2006), to enforce students to move through ZPD, techniques such as scaffolding, dialogue and interaction, and cultural tools can be applied.

Methodology

This research seeks to apply content analysis to analyse the causes of student misbehaviour, distraction and the teacher’s reactions and strategies to these challenges in the foreign language classroom. To conduct the research, a workshop was held with eight foreign languages teachers from the foreign languages department at a private school.

Participants

The participants were 8 female foreign language teachers: 6 English, 1 Spanish, and 1 French.

Study materials

Participants were provided with 3 scenarios, where teachers face challenges with students’ misbehaviour. These specific scenarios were the most common ones:

Scenario 1: Frequent Interruptions. A student frequently interrupts class discussions by speaking out of turn or making side comments, distracting other students, and disrupting the flow of the lesson.

Scenario 2: Refusal to Participate. A student repeatedly refuses to participate in group activities or discussions, often sitting quietly or engaging in unrelated tasks. Their lack of participation impacts the group dynamic and their overall learning experience.

Scenario 3: Attention-Seeking Behaviour. A student frequently seeks attention by making jokes or exaggerated gestures during lessons, occasionally causing other students to laugh or engage with the disruptions, impacting class focus.

Study procedure and data analysis

Step 1: Define the research questions. Research questions were formulated based on the scenarios: (1) What is the common students’ misbehaviour in the foreign language settings? (2) How do teachers address misbehaviour while promoting respect and engagement? (3) What common strategies are used to implement positive discipline techniques?

Step 2: Define the context of the generation of the document. The participants were presented with three scenarios to evaluate within 25 minutes. This was followed by a discussion and exchange of ideas (20 min). The researcher (also the workshop facilitator) took notes throughout the workshop.

Step 3: Define the units of analysis. In this specific paper, the unit of analysis is in the syntactical level. Each teacher’s response has been analysed sentence by sentence and then has been coded.

Step 4: Decide codes to be used in analysis. In this step, key themes have been identified with the inductive coding, in which meaning has been derived directly from the text. Codes have been categorised into two distinct sections: triggers of misbehaviour and teachers’ techniques to deal with these challenges. The schemes of all the codes are given in the results section.

Step 5: Construct the categories for analysis.

Step 6: Conduct the data analysis. Within the analysis process, manual coding has been applied to determine the common patterns, which are related to student misbehaviour and teachers’ strategies. Each response provided by teachers has been systematically reviewed and analysed. The frequency of usage of each code has been identified and reviewed to check if it is an indicator of their significance. According to Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (2007), the frequency of the codes may not be a sign of their importance. To deeply analyse the codes, steps such as extrapolations (trends and differences), standards (judgements and evaluations), and indices (frequencies) have been taken. These steps have been provided by Krippendorp (cited in Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007).

Study ethics

This workshop has been conducted in accordance with the principles of ethical research practice. Before the workshop, each participant has been acquainted with the agenda and context of the study and informed about the potential utilisation of their contributions in the research article. Following the provision of comprehensive information regarding the research process and the workshop, each participant has been provided with a consent form to which they have appended their signature. The consent form provides the participant a right to withdraw from the study at any time. Participants’ anonymity has been preserved, and confidentiality has been maintained.

Results and Discussion

1. Causes of misbehaviour in the foreign language setting

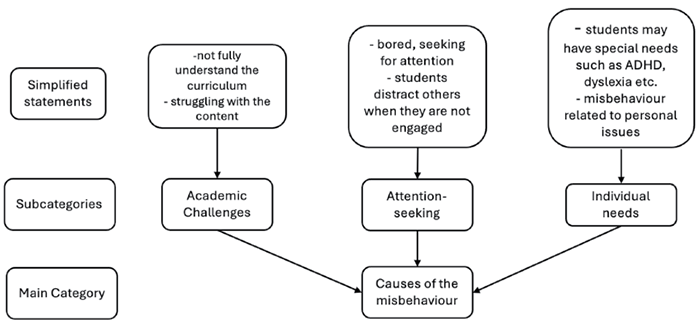

The primary factors contributing to students’ misbehaviours in foreign language settings are academic challenges, attention seeking, and individual needs. However, academic challenges have been identified as the predominant cause of misbehaviour. Participants have concluded that the majority of students avoid undertaking tasks or misbehave when they do not fully comprehend the curriculum or the task at hand. A sequential scheme for the construction of the codes is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Illustrating the process of grouping subcategories which makes the main category as ‘causes of the ’

1.1. Academic Challenges

As posited by Zhang, Huang, and Liu (2022), academic challenge is defined as a condition, in which students are expected to find equilibrium between the difficulty of the task and their academic aptitudes. The study emphasises that students who have strong academic skills and encounter tasks of minimal difficulty may experience a state of relaxation characterised by apathy. Conversely, students with weaker academic skills may encounter anxiety, a concept derived from the theoretical framework of flow.

One of the participants highlighted, ‘‘Find out about the student’s academic challenges. Maybe she/he does not fully understand the curriculum.’ Another participant went on stating, ‘Look for the reason: maybe the student has gaps or is a quick learner, and the material does not match his skills, maybe he has behaviour challenges.’ These insights and observations underscore the significance of academic challenges as a factor contributing to misbehaviour in the foreign language classroom. It is evident that the participants do not exclusively highlight the slow learners, who encounter academic challenges; they also draw attention to the fast learners, for whom the curriculum might be more suitable. In both scenarios, it is imperative to implement differentiations to address these challenges and prevent misbehaviour, as was discussed by the participants.

1.2. Attention Seeking

As a secondary contributing factor, the educators have indicated that attention seeking is a prominent issue. One teacher commented, ‘They are seeking attention, bored, struggling with the content, or testing boundaries.’ From the context of the comment, it is evident that attention-seeking behaviour is associated with a multitude of factors. While some students may seek attention due to feelings of boredom, others may require additional challenges in order to engage with the content. Nevertheless, the predominant correlation between attention-seeking behaviour and the testing of boundaries is noteworthy. Consequently, this form of misconduct may be associated with underlying factors that extend beyond the immediate context.

1.3. Individual needs

During the observation of the workshop, the attendees noted that instances of student misbehaviour are not necessarily indicative of academic challenges but rather may be attributed to unique individual needs. In some cases, students with strong academic skills encounter difficulties in maintaining concentration or completing tasks due to their individual needs. One teacher commented, ‘Maybe there are some issues which are not related to you as a teacher or school in general. A student needs to know that you are here to help him/her and find the best way for them to study’, while another participant specifically highlighted, ‘If the student has some personal need: ADHD, dyslexia, etc., it could be an indicator.’ The final remark in the commentary makes it clear that individual differences, including but not limited to ADHD and dyslexia, can result in students demonstrating inappropriate behaviour or underperforming during lessons.

In conclusion, it is evident that these causes were given greater emphasis during the workshop in comparison to other factors. Academic challenge was identified as the most prevalent cause, while individual needs were noted as a less frequent cause but nevertheless significant, particularly as they provide assistance for teachers to address these issues.

2. Positive discipline techniques proposed by foreign language teachers

During the workshop, the teachers were invited to consider the challenges and misbehaviours that had been identified. Nevertheless, the primary objective was to uphold and implement positive discipline in the face of these challenges. In response to these challenges, which are encountered on a daily basis by teachers, a plethora of techniques were proposed. Upon conclusion of the coding process, techniques such as active engagement, personal talks, positive reinforcement, and classroom rules reminders were identified as being more frequently employed. A sequential scheme for the construction of the codes is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Illustrating the process of grouping subcategories which makes the main category as ‘positive discipline techniques’.

2.1. Active Engagement

During the workshop, it was observed that when students are actively engaged in the classroom, they are less likely to misbehave or distract their peers. One of the participants highlighted, ‘Assigning them as a leader of a group, giving more responsibility and this way they can remain active, though in a productive way.’ Another participant stated, ‘assign specific tasks or responsibilities to help channel their energy productively, like being a helper during activities.’ From the comments, it is evident that the most effective methods for fostering active engagement techniques in the classroom are the allocation of specific roles or responsibilities and the incorporation of teamwork activities. During the coding process, it was observed that educators have identified active engagement as a primary strategy for addressing misbehaviour. This approach was referenced on six occasions throughout the discourse.

2.2. Personal talks

Furthermore, the educators in the workshop emphasised the significance of conducting individual dialogues with students exhibiting disruptive behaviour, as opposed to issuing public condemnation. One participant commented, ‘Talk personally after the lesson, show I care. Take him for tea in cafeteria one day and show I really care and see the reason.’ This comment suggests that teachers are inclined to favour a more humanistic approach when it comes to misbehaviour. Another participant commented, ‘Have a non-confrontational, one-on-one conversation to understand why they are disengaged. Ask open-ended questions such as, ‘I’ve noticed you seem distracted in class—can you tell me what’s going on?’ .’ In this scenario, the teacher demonstrates a preference for individual talks, utilising a professional interrogation technique to ascertain the underlying causes of the student’s misbehaviour.

2.3. Positive reinforcement

Positive reinforcement is regarded as a form of engagement that aims to promote desired behaviour and emphasise the positive outcomes of such behaviour (Pettit, 2013). Positive reinforcement has been emphasised as a clear indicator of positive discipline in the classroom. However, in practice, educators may be inclined to focus exclusively on negative behaviours, while positive actions are often overlooked. The use of positive reinforcement, or the acknowledgement and praise of exemplary behaviour, has been posited as a means to engender a more conducive environment in the context of foreign language learning.

Teachers emphasised the importance of positive reinforcement to maintain positive discipline in the classroom. One of the participants commented, ‘Praising the student who was waiting for his/her turn. I appreciate how he/she waited for his/her turn to speak.’ It is clear that appreciating the student to follow the established rules can set a positive example for others from this context. Another educator commented, ‘I ensure that I frequently praise and reinforce positive actions to show that good behaviour earns attention, not disruptions.’ This comment suggests that educators have adopted a positive behavioural approach with the aim of demonstrating to students, who are motivated by attention seeking, that the only way to gain attention is to behave in a certain way.

2.4. Classroom rules reminders

In the discourse, it was posited that on occasion, the most efficacious approach to address inappropriate behaviour is to remind the students of the established norms that govern classroom conduct. Violations of these rules typically result in consequences, as asserted by the teaching professionals in the workshop.

One of the educators commented, ‘I will pause and remind the students about the importance of taking turns and not interrupting other students while speaking or responding to the questions asked.’ This remark suggests that prompt responses to unruly behaviour, such as the immediate interruption of the lesson, can serve as an ultimatum and a reminder of the established rules. Other comments stated by an educator, ‘I remind kindly all the class about our class rules that we agreed all together at the beginning of the course’ suggests that educators must remind the initial agreement not only to the misbehaving student but to the whole class to assure that they are all on the same page.

Looking at the results of the study, two aspects have emerged. First, the results indicated that academic challenges, attention seeking, and individual needs are the most common causes as the teachers discussed. These causes have also been highlighted in the research by Muharremi (2014). Another finding by Benaissi (2021) emphasises the proficiency level of the students in the language and its direct impact in classroom participation. This research is directly linked to the foreign language classroom challenges. Therefore , these two findings highlight academic challenge as a main cause of misbehaviour in the classroom, which coincides with the results of the workshop by the teachers as indicated in the results section.

Second, the results have sought to identify the positive discipline techniques to deal with these challenges. The findings indicate that active engagement has stood out as the most effective strategy. The study conducted by Yasin, Mustafa, and Bina (2022) also emphasises the importance of active engagement and its role to manage the misbehaviour.

Conclusion

This article has aimed to identify the major misbehaviours in the foreign language classrooms and teachers’ responses and strategies to these challenges by maintaining positive discipline. Participants have indicated that students’ misbehaviours are normally rejecting doing the tasks, talking without waiting for their turn, distracting classmates, etc. The findings of the study indicate that the most common causes of these kinds of misbehaviours in the foreign language classrooms are academic challenges, attention seeking, and individual needs. These causes have stood out mostly discussed by eight foreign language teachers in the workshop. Participants have provided techniques such as active engagement, personal talks, positive reinforcement, and classroom rules reminder as main positive discipline strategies to avoid such challenges.

References

Apaydın, S. (2022). The Effect of Positive Discipline Parenting Program on Parental Disciplinary Practices, Parenting Stress and Parenting Self-Efficacy [Ph.D. - Doctoral Program]. Middle East Technical University, 47-64.

Benaissi, A. (2021). Misbehaviour in Moroccan EFL classrooms: Exploring the causes and strategies for prevention. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 6(7), 74-78.

Cabaroğlu, N., & Altınel, Z. (2010). Misbehaviour in EFL Classes: Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives. Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 99-119.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2002). Research methods in education. Routledge.

McCaslin, M., Bozack, A. R., Napoleon, L., Thomas, A., Vasquez, V., Wayman, V., & Zhang, J. (2013). Self-regulated learning and classroom management: Theory, research, and considerations for classroom practice. In Handbook of classroom management, 233-262.

Muharremi, A. (2014). Disruptive Behaviours in the Class of the Foreign Language. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 4,495-499.

Parsonson, B. S. (2012), Evidence-Based Classroom Behaviour Management Strategies. Kairaranga, 13(1), 16-23.

Pettit, M. J. (2013). The Effects of Positive Reinforcement on Non-Compliant Behaviour (Doctoral dissertation, Northwest Missouri State University).

Shamnadh, M., & Anzari, A. (2019). Misbehaviour of school students in classrooms ̶ main causes and effective strategies to manage it. International Journal of Scientific Development and Research (IJSDR), 4(3), 318-321.

Wangdi, T., & Namgyel, S. (2022). Classroom to reduce student disruptive behaviour: An action research. Mextesol Journal, 46(1), 1-11.

Yasin, B., Mustafa, F., & Bina, A. M. S. (2022). Effective classroom management in English as a foreign language classroom. PAROLE: Journal of Linguistics and Education, 12(1), 91-102.

Zhang, X., Huang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2022). Enhancing language task engagement in the instructed language classroom: Voices from Chinese English as a foreign language students and teachers. International Journal of Chinese Education, 11(2).