Kalbotyra ISSN 1392-1517 eISSN 2029-8315

2025 (78) 89–110 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Kalbotyra.2025.78.4

Baiba Egle

Liepaja Academy

Riga Technical University

Lielā iela 14

LV-3401 Liepāja, Latvia

E-mail: baiba.egle@rtu.lv

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6207-7789

https://ror.org./00twb6c09

Dzintra Lele-Rozentāle

Liepaja Academy

Riga Technical University

Lielā iela 14

LV-3401 Liepāja, Latvia

E-mail: dzintra.lele-rozentale@rtu.lv

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3181-6929

https://ror.org./00twb6c09

Agnese Dubova

Liepaja Academy

Riga Technical University

Lielā iela 14

LV-3401 Liepāja, Latvia

E-mail: agnese.dubova@rtu.lv

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7428-1824

https://ror.org./00twb6c09

Gints Jēkabsons

Institute of Applied Computer Systems

Riga Technical University

Zunda krastmala 10

LV-1048 Rīga, Latvia

E-mail: gints.jekabsons@rtu.lv

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9575-2488

https://ror.org./00twb6c09

Abstract. The paper discusses the problems identified in the early stages of an interdisciplinary project that focuses on the creation of a bilingual abstract corpus of bachelor’s theses from a linguistic point of view. The aim of this paper is to summarize the identified problem cases and to show the perspective of linguistic analysis of the corpus to be formed based on the research of special literature on the abstract types, the methodology of abstract analysis of bachelor’s theses and problems of text creation, as well as the results of the pilot study.

From the annotated corpus of texts, 25 Latvian abstracts and their corresponding 25 English translations were randomly selected. The texts were obtained from the Registry of Final Theses of Riga Technical University (RTU) (2023–2024). When looking at the abstracts in correlation with the RTU methodological instructions, it can be established that the text type ‘abstract’ is mentioned and briefly described, but the descriptions and scope of their structure differ between faculties and study programs. In the pilot study, based on the modified models by Swales and Feak (2009) and Hyland (2000/2004) concerning the structure of abstracts consisting of different moves and steps, the abstracts’ text-internal sequence as well as quantitative indicators, such as detailed breakdowns of moves used, the length of an abstract, etc., were determined. Moreover, the relationship between moves forming patterns and the model of moves was adapted to the needs of researching texts written by Latvian students, and problems encountered during the intentional and deliberate annotation of the corpus were identified. These problems are mainly related to the lack of in-depth academic writing courses and the often-overgeneralized style of methodological instructions. The sequence of the moves and steps in the corpus is diverse. As abstracts constitute an internationally standardized text type, it does not seem purposeful to interpret differences in an intercultural context. This study has also found that the editing of abstract translations should be taught to students due to the way these translations are performed. The results of the pilot study show the need for modern academic writing support, which is the focus of further research.

Keywords: academic writing, undergraduate abstracts, bilingual text corpus, translation, Latvian, English

_________

Submitted: 24/02/2025. Accepted: 30/09/2025

Copyright © 2025 Baiba Egle, Dzintra Lele-Rozentāle, Agnese Dubova, Gints Jēkabsons. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1 Introduction

The study is part of the project Towards AI-Based Thesis Abstract Writing Aid: Bilingual Text Corpus Preparation, Analysis, and Model Development, which was launched in late 2024 by RTU Liepaja Academy. The aim of the project is to prepare and analyse a bilingual abstract text corpus formed by the abstracts of the bachelor’s theses of Riga Technical University (RTU) in Latvian and English over the last two years (2023–2024) in order to further develop a general abstract text model and its variants as a basis for the development of an academic writing tool to support the writing of the bachelor’s thesis abstract.

In parallel to the work with the corpus, we study whether the structure of the abstracts complies with the instructions provided in the methodological materials of the RTU faculties. The project is currently still in its early stages, and therefore this paper will focus on the problems found in the early stages of a pilot study on 50 randomly selected abstracts, while also taking into account the research results of undergraduate student writing skills in other countries and languages. The corpus for the research project consists of over 1000 abstracts written by RTU students in 2023 and 2024. To gain insight into the corpus and what to expect in further research, we randomly selected 25 abstracts (each abstract has a Latvian and English version) to ensure that true randomness is achieved, and that there is no bias regarding the study programme or department. The years 2023 and 2024 were selected to show the latest trends in abstract writing at RTU. Although abstracts are a standardized text type, they are far from a simple text to write, as students write an abstract usually for the first time writing their bachelor’s thesis since they do not typically write abstracts for other assignments during their studies. The aim of this paper is to summarize the identified problem cases and to show the perspective of linguistic analysis of the corpus to be formed based on the research of special literature on abstract types, the methodology of abstract analysis of a bachelor’s thesis along with problems of text creation, as well as on the results of the pilot study.

2 Theoretical framework

The analysis of abstracts as a text type is a current issue in academic writing within many linguistic cultures, whereas the number of publications devoted to this genre of text has become almost uncountable, which can be explained by the process of globalization and, in connection with this, the internationalization of studies and research. Studies on non-English abstracts of different study or academic career levels are relatively rare, although it is possible that these studies have not been published in English (for research on abstracts in the humanities in Lithuanian, English, and Russian, see Gobekci 2023, 33). In Latvian, abstracts have been studied as a type of secondary text in comparison with texts in German (Dubova 2009, 83–100). No research on abstracts of student papers has been published so far.1

This text type in Latvian and English has become an obligatory requirement for all final works such as bachelor’s and master’s theses. This aspect of academic writing in Latvia has not been looked at in research previously, and RTU, as one of Latvia’s largest universities, has a sufficient amount of final works that can be used as an example of the bigger picture in specific academic writing scenarios.

The theoretical basis of this article consists of abstract standards based on ISO and ANSI that give the international definitions of what an abstract should be as well as previous research, which:

1) are attributable to the abstract as text type and its subtypes, as well as 2) research that focuses on bachelor’s theses, 3) describes the methodology of abstract analysis of bachelor’s theses, and 4) identifies text formation and writing problems at the macro- and microstructure level of the text. These aspects are especially important in the first stage of corpus formation, annotation, and analysis.

2.1 Abstracts as a standardized text type

The International Standard (ISO) for abstracts, which is also recommended for the description of a thesis that could be written by an undergraduate student, is defined as a term for a text that “signifies an abbreviated, accurate representation of the contents of a document, without added interpretation or criticism and without distinction as to who wrote the abstract” (ISO, 1). According to the ISO Standard, 3 abstract types are described: 1) informative, which “present(s) as much as possible of the quantitative and/or qualitative information contained in the document”, 2) indicative or descriptive, which can be a guide to the type of document the principal subjects covered, and the way the facts are treated, and 3) informative-indicative, “when limitations on the length of the abstract or the type and style [...] make it necessary to confine informative statements to the primary elements of the document and to release other aspects to indicative statements” (ibid.). The choice of a certain type is therefore influenced by the type of the main text.

The distinction between informative and indicative abstracts is also made by the American national standard developed by the National Information Standards Organization (ANSI/NISO) describing informative abstracts as “generally used for documents pertaining to experimental investigations, inquiries, or surveys” and containing “the purpose, methodology, results, and conclusions presented in the original document” (ANSI/NISO). Indicative abstracts, in turn, “are best used for less-structured documents, such as editorials, essays, opinions or descriptions; or for lengthy documents [...]” (ibid.) and present the “purpose or scope of the discussion or descriptions” as well as “essential background material, the approaches used, and/or arguments presented in the text” (ibid.).

In addition to these three types, there is an extended list, which is not relevant in the context of an undergraduate bchelor’s thesis as this classification refers to another specific document or a different text type context, such as critical abstract and slanted abstract (ANSI/NISO, 18), or highlight abstract (Asikuzzaman 2024).

Abstracts can also be distinguished by form as either paragraphing or structured abstracts (ANSI/NISO, 5).

The description of the text type abstract was detailed by Busch-Lauer (2012). Her research focuses on the communicative aspects of this text type and authorship, content and positioning. Busch-Lauer based her abstract categorization on ISO, ANSI, as well the German Committee for Terminology and Language of the German Documentation Association, and the German Institute for Standards definitions for informative, indicative, informative-indicative, as well as structured abstracts.

Busch-Lauer describes 6 types from the communicative point of view:

1. depending on the time of writing the text – retrospective (written after the primary text) and prospective abstracts (for example, conference abstracts);

2. by the author – as the sole author of the abstract (Autorenabstract), an abstract created by someone else (Fremdabstract), and machine created abstracts (maschinell erstelltes Abstract);

3. by content – informative, indicative and mixed form abstract;

4. by place in the text, for example, as a subtext between the title and the body text, as an abstract in a foreign language at the end of a journal or collection, and as an autonomous text in an Abstracting Journal;

5. by form and layout – text, structured and Schlagwortabstract (based on keywords) (Text-, Struktur- and Schlagwortabstracts); and

6. abstract in the language of the document and in a foreign language (Busch-Lauer 2012, 7).

Following this classification, the bachelor’s thesis abstracts analysed in our study are characterized by the following traits: retrospective, they are Autorenabstracts – written by the authors of the theses, content – informative, indicative or informative-indicative, they are paratexts in the full version of the bachelor’s thesis, created in text or in a structured form in the language of the document (bachelor’s thesis) as well as in a foreign language (English)2.

2.2 Bachelor’s thesis abstracts in research

Research devotes less attention to bachelor’s theses than to master’s theses, doctoral theses and journal articles. Without denying the fact that published article abstract research can provide theoretical support, for example, to creation of study materials for bachelor’s students, however, it is necessary to emphasize the different prerequisites that distinguish bachelor’s students from other target groups. Students have relatively little experience in research, discourse and text formation of research questions; as also, a limited (and short) period of time is devoted to the acquisition of the basics of the discipline, which is usually 3 years. For this reason, the creation of the corpus planned in the project is focused on the bachelor’s level of education, considering the gradualness in the acquisition of text formation.

In part, this may be due to the different requirements of universities in different countries. For example, in Indonesia, as well as in Latvia, students must write abstracts to bachelor’s theses in two languages, specifically, in their mother tongue, i.e., Indonesian, as well as in English. Therefore, the question of the equivalence of abstracts in both languages arises. The structure of native language texts translated into English is not necessarily equivalent to the target language abstract genre (Suryani & Rismiyanto 2019, 193). When explaining the lack of research on bachelor’s thesis abstracts, Suryani and Rismiyanto emphasize that “the students are still considered new to the academic community and are still guided in conducting research. That can be the reason why few, even might be none [sic!], studies are found on bachelor’s thesis abstract” (Suryani & Rismiyanto 2019, 192).

Swales and Feak’s book Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts (2009) highlights the ‘pedagogical consequences’ (Swales & Feak 2009, xi) by pointing to the global increase in the role of the English language and the research literature devoted to it. Their book is addressed to “graduate students and junior researchers” (ibid., xiii), but it is also relevant for undergraduate students, especially if the text type of abstracts is included in the study program.

Abstract analysis is based on the structure of 5 rhetorical moves described by Swales and Feak (2009, 5). A move is explained here as “a stretch of text that does a particular job. It is a functional, not a grammatical term. A move can vary in length from a phrase to a paragraph” (ibid.). These 5 moves, corresponding to the IMRaD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) structure, are as follows:

Move 1: Background, introduction, situation;

Move 2: Present research, purpose;

Move 3: Methods, materials, subjects, procedures;

Move 4: Results, findings;

Move 5: Discussion, conclusion, implications, recommendations (ibid.).

This subdivision coincides with the functional moves, as listed by Hyland (2000): Introduction, Purpose, Method, Product, and Conclusion, which underlies a large number of abstract analyses (Darabad 2016; Pratiwi, Hermawan & Muniroh 2021; Putri, Hermawan & Muniroh 2021; Ramadhini et al. 2021, etc.).

We use a slightly modified division in our annotation (see description of methodology in Section 4.2).

Šulovská’s (2022) paper, dedicated to the study of academic writing, including the abstract as a genre in English, describes mainly Slovak undergraduate students’ abstract writing in ESP classes at the Faculty of Arts, Comenius University, Bratislava. She describes informative abstracts as ‘complete’, and indicative abstracts as ‘limited’. The informative abstract structure consists of 5 moves – background, purpose, methods, results, and conclusions – but, in the abbreviated case of the ‘reduced abstract’, there are only 3 moves: purpose, methods, and results. Abstracts consist of one paragraph, and the word limit is between 100–500. According to Šulovská, the language of abstracts is characterized by an impersonal style, i.e., passive forms are used, while avoiding pronouns of persons, which, however, depends on the discipline. The abstract typically uses the formal academic style, and, for the acquisition of this style, its typical vocabulary is offered: key verbs, nouns, adverbs, and adjectives (Šulovská 2022, 76).

Descriptive abstracts, which are often written in philosophy, are described as consisting of the background, purpose and focus of the paper or article, without specifying the methods, results and conclusions (Šulovská 2022, 77–86). Šulovská associates moves with the function expressed in a certain style by questions as well as with the use of their characteristic tense. In informative abstracts, the move Background (What?) is implemented with the Present Simple tense form, the Purpose (Why?) uses the Present Simple, Present Perfect and Past Simple tenses, the Methods (How?) use the Past Simple tense, the Results (What?) employ the Past Simple (and Past Perfect), and the Conclusion is presented in the Present Simple tense; tentative verbs, adverbs, adjectives and modals. Descriptive abstracts characterize the Background (What?) with Present Simple, the Purpose (Why?) with Present Simple, and the Focus (What?) is implemented with the Present Simple, tentative verbs, adverbs, adjectives and modals (Šulovská 2022, 87–88).

Frydrychova Klimova wrote about the acquisition of the abstract genre in English to “demonstrate how to teach formal writing, particularly the writing of abstracts in English” (Frydrychova Klimova 2015, 908), by offering guidelines and reflecting the typical mistakes of Czech students and academics when writing English abstract texts.

Student thesis abstracts from the Department of English Education in UIN Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta were analysed by Luthfiyah, Alek and Fahriany at the level of text cohesion and moves, by rating the use of cohesive devices based on their gradual technique (high, medium, low) as medium (Luthfiyah, Alek & Fahriany 2015, 148). Moves patterns mostly do not follow the pattern outlined by Swales and Feak (2009), and errors are detected in the tense and passive voice usage, which is explained by the students’ “lack of knowledge about the abstract features” (ibid., 157).

Undergraduate thesis abstracts are also viewed interlingually and intralingually. When emphasizing that “analysis of rhetorical moves of abstracts written in two languages is still scarce”, Putri, Hermawan and Muniroh (2021), based on Hyland’s 5 moves patterns, studied the abstracts of undergraduate as well as graduate theses and dissertations created by students at 3 different educational levels in Indonesian, as well as their English translations. The number of moves in Indonesian and English was slightly different (284 moves in Indonesian and 281 in English). Apart from move 3 (method) and move 4 (results), all other moves showed differences in different levels of education. At the first two study levels, less attention is paid to conclusions (Putri, Hermawan & Muniroh 2021, 164–166). These results show that the usage of moves in Indonesian and English is relatively similar.

The results of research on scientific articles are also considered important for the acquisition of English writing proficiency. A number of articles focus on abstracts of scientific articles, emphasizing that the results of the analysis will also be useful for students when learning text creation in English without differentiating the level of study: “Finally, the results suggest some key implications for teachers, learners, and all practitioners working in the field of Discourse Analysis (DA), English for Specific Purposes (ESP), and English for Occupational Purposes (EOP).” (Darabad 2016, 137)

The approach to writing bilingual abstracts can be different, and the emphasis is most often on writing English texts. Thus, for example, Frydrychova Klimova analyses the errors of 3rd year Czech part-time students of the University of Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic bachelor’s work in English abstract texts. She found influence of the Czech language arising in the translation process and concluded that the errors stem “from the linguistic-stylistic point of view”, and that Czech students have difficulties in English “word order and objectivity of one’s abstract”, as well as a variety of common grammatical and language use issues that are typical in texts by foreign language learners (Frydrychova Klimova 2013, 514). As a result, “the methodological message for the teachers is to make students first summarize any English text before they start writing any abstract which might be based on the Czech text” (ibid., 516).

The writing process and contents of bachelor’s paper abstracts should be seen as a separate text type as the requirements, writer experience, and context are different from master’s, doctoral and scientific research. A bachelor’s paper abstract is a type of scientific text that a student has to produce for their final thesis as a required part for all students of Riga Technical University, which is a requirement for all study programmes and fields. This might be the first time the student encounters the need for an abstract to be written. While, throughout their studies, students read scientific texts, they might not pay attention to the abstracts of those texts, and especially to the finer structural aspects of an abstract. The goal of a bachelor’s paper abstract can be seen as significantly different from an abstract of a scientific paper written by an experienced researcher – as the bachelor’s student does not need to ‘sell’ the idea of the research to entice the readers. Commonly, bachelor’s thesis abstracts reflect the student’s research, which is, in most cases, more practical than theoretical – for example, a student might describe a plan to increase employee motivation in one specific company without claiming (or attempting) to have found a ground-breaking theory or application. Another factor to consider is the limited readership. While the abstracts are made publicly available in Latvia, it is not legally required to make the bachelor’s thesis itself publicly available. Thus, the initial readership of the bachelor’s thesis abstract consists of the advisor, the reviewer and the bachelor’s defence committee. Later, successfully defended bachelor’s theses might be of interest for other students of the same study program, but, usually, a bachelor’s thesis abstract might not have the larger potential reader public like a peer-reviewed scientific article published in a journal.

Instead, the Bachelor’s paper abstract could be treated as a type of a stepping stone towards academic writing – where the writer needs more guidance and assistance to learn the skills they need. Bachelor’s level students may have some experience of writing essays and other homework tasks set by their teachers, but, most often, homework does not require the writing of an abstract. The guidelines provided by their university are often the main, and possibly only, document which the students consult when writing their bachelor’s paper abstract. That is why some institutions will give a template for an abstract to aid students in their writing, but even the templates are not given with extensive descriptions and tips on how to write the abstract.

Good guidelines could be a way to improve the writing quality of the abstracts that BA students submit. The writers of the guidelines should take into account the amount of experience the students have, how the material they can access is laid out, and what requirements are set for the students, so that abstracts match the requirements and expectations of the institution and the study program.

3 Abstract in bachelor’s theses in Latvian universities: The example of RTU

The Latvian education system requires that bilingual abstracts are written for the bachelor’s thesis.

RTU is one of the largest universities in Latvia, and its main fields of study are natural sciences, engineering and technology, social sciences and humanities, and art sciences. Consequently, our corpus consists mainly of the abstracts of bachelor’s theses in the field of engineering, which is expected for a university that traditionally used to focus on a large variety of engineering-related fields and added a strong Humanities branch only in 2024. In accordance with the requirements in force in Latvia, abstracts are included in the full text of the bachelor’s thesis and are available in universities’ repositories. bachelor’s theses and abstracts have been collected in the Registry of Final Theses of the RTU since 2010.

While RTU does have scientific writing courses for students regardless of their study program, there are no specific lectures for the study of abstract writing, and the only sources of information on abstract writings are the methodological instruction offered by the faculty, materials available on the internet, information obtained in consultations, and, of course, the exchange of experience with course mates.

RTU methodological guidelines for the development of final papers have been developed both for individual faculties, such as the Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology (DITF 2023), as well as for specific study programs, such as the Professional Bachelor’s Study Program “Heat, Gas and Water Technology” (BMF PBSP 2024) of the Faculty of Construction and Mechanical Engineering. The instructions stipulate that an abstract in Latvian and its English translation are a mandatory part of the bachelor’s thesis. DITF (2023, 5) describes an abstract as consisting of four parts: keywords, a brief description of the content of the work with an introduction to the study, the purpose and results, and data on the scope of the work. The abstract specified in BMF (2024, 9) must contain four parts: the name of the author of the work, as well as the title; then, the topic, content, main results and conclusions; moreover, the language of the work must be indicated, and, finally, the length of the work must be stated. Keywords must be specified after the text of the abstract. The length of the abstract in both instructions differs: DITF (2023, 5) restricts it to no more than one page, while BMF (2024, 9) limits the text to no more than three-quarters of a page. Differences thus appear both in the structure and length of the abstract. Therefore, presumably, abstract texts will be different, which may also be determined by the specifics of the field of science. All the methodological instructions of RTU on the development of the final papers studied indicate that the abstract in Latvian, followed by an analogue abstract in English. Therefore, we presume that the English abstract is a subsequent translation of the Latvian abstract.

4 Methodology

4.1 Description of the material

50 abstracts (25 in Latvian and 25 in English) from the hitherto annotated corpus (2023–2024) were randomly selected with the following aims:

1) determine the number of words in Latvian and English abstracts;

2) determine the implementation of moves and steps based on the Moves and Steps models by Swales and Feak (2009), Hyland (2000/2004), etc., and our modified model (see below);

3) explore the patterns forming moves, and explain their relationship with the role of external factors in text formation;

4) infer perspectives for further research.

Metadata is excluded from the further analysis. This metadata incorporates keywords, as well as the description of the length of the work, number of pages, number of chapters, number of attachments, number of literature sources, number of images, number of tables, etc., which are marked with [[len]] when annotating the corpus. Also, information about the author, supervisor, title, type of work, language, etc., which obtains a marker in the annotation of the corpus [[meta]], is excluded from this analysis.

The abstracts in both languages were annotated; however, the Latvian abstract can be considered the original source material, even though abstracts in both Latvian and English were analysed.

4.2 Description of the analysis

The following steps are taken during the analysis:

1) anonymizing and annotating the selected texts, which, in this pilot study, was carried out manually in a group of 3 annotators. This made it possible to immediately discuss the encountered problems and agree on a solution;

2) tabular compilation of detected moves and steps;

3) preparation of texts for qualitative and quantitative analysis with Sketch Engine;

4) linguistic (genre) analysis of texts with the aim of analysing how coherence is implemented;

5) verifying the equivalence of the translated abstracts.

The annotation of the whole corpus takes place, based on the 5-moves-model of Hyland, and adapted to the specifics of this research project, for example, by having move 2 split into 3 different steps so that to enhance the clarity of the annotation process and to ensure that the annotation process matches the guidelines that the students receive:

An example of an annotated abstract in Latvian and English is given in Table 1.

|

Latvian version |

|

Katrā valstī un nācijā ir neredzīgi un vājredzīgi cilvēki, taču šai iedzīvotāju grupai informācijas uztveršana un piekļūstamība internetā ir ierobežota. Pirms mājaslapu uzlabošanas, tajās ir jānoskaidro piekļūstamības problēmvietas. To var izdarīt, testējot attiecīgās mājaslapas. Mājaslapu piekļūstamības iespējas var testēt gan manuāli, gan izmantojot kādu automatizētu rīku. [[back]] Bakalaura darba mērķis ir salīdzināt pieejamos tīmekļa piekļūstamības testēšanas rīkus, pamatojoties uz to spēju identificēt mājaslapu neatbilstības WCAG vadlīnijām, darboties dažādās tehnoloģijās un vidēs, kā rezultātā izstrādāt vadlīnijas šādu rīku izvēlei. [[aim]] Bakalaura darbā tika izvirzīti automatizēto piekļūstamības testēšanas rīku salīdzināšanas kritēriji, balstoties uz literatūras analīzi. Vadoties pēc izvēlētajiem kritērijiem, tika veikti eksperimenti, kas ietver testēšanas rīku ātrdarbību, precizitāti, spēju noteikt neatbilstības WCAG vadlīniju pamatprincipiem un darboties dažādās vidēs, interneta pārlūkos u.c. [[meth]] Pēc eksperimentu pabeigšanas darba autors izstrādā vadlīnijas piekļūstamības testēšanas rīka izvēlei. [[res]] Ņemot vērā uz bakalaura darba autora veikto eksperimentu rezultātiem izstrādātās vadlīnijas, to lietotājiem būs iespēja izdarīt pamatotu piekļūstamības testēšanas rīka izvēli atbilstoši savām vajadzībām un prasībām. [[conc]] |

|

English version |

|

Blind and visually impaired people are part of every country and nation, but this group has limited to information and the Internet. Before improving websites, problem areas need to be identified. This can be done by testing the websites. Website Accessibility can be tested either manually and or using automated tools. [[back]] The aim of this thesis is to compare available web Accessibility testing tools based on their ability to identify non-compliance of websites with WCAG guidelines, to work in different technologies and environments, and to develop guidelines for the selection of such tools. [[aim]] Based on a literature analysis the author sets out criteria for comparing automated Accessibility testing tools. Based on the selected criteria, experiments were carried out, which included the speed of the tools, the accuracy of the tools, the ability of the tools to detect inconsistencies with the basic principles of the WCAG guidelines, the ability of the tools to operate in different environments, web browsers, etc. [[meth]] After the completion of the experiment, the author of the work puts forward guidelines for the selection of Accessibility testing tools. [[res]] Following the results of the experiment carried out by the author, the user of the guidelines can choose the appropriate tool for his situation. [[conc]] |

Table 1. Example of an annotated abstract in Latvian and English

The pilot study was carried out in parallel with the initiated annotation of the corpus, which takes place in several stages, and which has not yet been completed. Its preliminary results are also partially reflected in this article. The pilot study offers a detailed and broader review of the texts with the aim of recording the problems expected in a more extensive corpus analysis in the future.

5 Results of the pilot study

5.1 Quantitative results

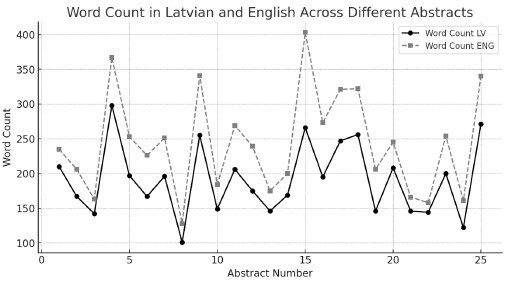

The average number of words in Latvian abstracts is 191 words, with the longest abstract comprising 298 words, and the shortest abstract comprising 101 words. The number of abstract words translated into English is higher than in the original Latvian abstracts. On average, English abstracts consist of 243 words, with a maximum of 406 and a minimum of 128 words (see Figure 1). The length of the analysed abstracts corresponds to the length specified by ISO 214.

Figure 1. Number of words in abstracts in Latvian and English

RTU general requirements for a bachelor’s thesis and other final theses contain an indication that the requirements for the structure and scope of the thesis are determined by the faculties (Guidelines for RTU 2014). This could explain the different abstract lengths in the Registry of Final Theses. The aim of this research is to give insight into various engineering-related abstracts without specifying the exact fields or subfields of science.

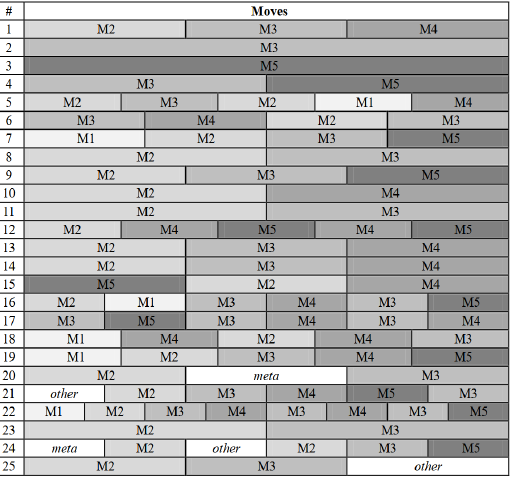

Regarding the annotation of moves, no differences were found between the Latvian and English texts as they are direct translations, however, in the larger corpus of abstracts that is not part of this study, some differences may exist. The results of this process are summarized in Table 2 for each selected text with the aim of visualizing the structure of the texts. Moves are arranged in the order in which they are found in the text. In some cases, one move breaks down if it has another move in the middle. This usage of atypical, repeated moves has been described in Luthfiyah, Alek and Fahriany (2015), where they call it ‘move cycling’, while other authors have called it a ‘hybrid move’, but we use ‘split’ for conciseness and to match the moves found in the Latvian student writing, see Table 2 below.

Table 2. Move patterns

Move patterns show great diversity in the structure of texts, and this applies not only to the representation of moves, but also to the order in which they appear in the text. Only one of the 25 texts contained the traditional order of moves from 1 to 5 (see No. 19, Table 2), and only 2 more contained all five moves, but in a mixed or divided order. Surprising is a group with 1 move – in two cases, M5 [[conc]], whereas in one – M3 [[meth]]. The dominant structure is with 2 moves: there are 7 texts containing 2 moves; 5 with M2M3, excluding a split with [[meta]]. There were 8 texts with 3 moves, of which, only 2 are with identical structures, specifically, M2M3M4. It is obvious that one cannot speak of a certain textual tradition, and the question that arises is whether this affects the coherence of the text. The variety of models and divisions of moves suggests potential difficulties in text creation and serve as an incentive for the creation of teaching materials.

A different result from the requirements of the writing guidelines that demand all moves to be present in the abstract is observed when summarizing the number of moves in the analysed texts and calculating their percentage (see Table 3).

|

Moves |

Absolute frequency (split moves) |

Percentage |

|

Move 1 |

6 |

24% |

|

Move 2 |

20 |

80% |

|

Move 3 |

20 (5) |

80% |

|

Move 4 |

13 (4) |

52% |

|

Move 5 |

13 (1) |

52% |

Table 3. Moves frequency relative to the number of texts

None of the five moves are represented ideally in all 25 (50) texts. The dominant moves are Move 2 and Move 3, so it can be said that, most often, attention is paid to the goal (also motivation) and methods (also structure). Surprisingly few abstracts contain background information. Since none of the moves reaches at least 90% in all texts, it is not possible to talk about any obligatory category based on Hüttner’s breakdown, according to which, 90–100% means that the category is Obligatory, 50–89% stands for Core, 30–49% is within the range of Ambiguous, while 1–29% is perceived as Optional (Hüttner 2010, 205). In the selected texts, M2 and M3 are to be interpreted as the core, M4 and M5 as ambiguous, and M1 as optional. When compiling this assessment with the requirements of the methodological instructions, a discrepancy can be observed as the abstracts do not match the requirements. It is possible that incorporating a larger number of texts would change these percentages.

Texts differ in the number of moves represented in them. The percentage is shown in Table 4.

|

Number of moves (from all possible 5 moves) |

Number of texts |

Percentage |

|

5 |

3 |

12% |

|

4 |

4 |

16% |

|

3 |

8 |

32% |

|

2 |

7 |

28% |

|

1 |

3 |

12% |

Table 4. Number of moves represented in texts

As the proportion reflected in the table shows, the corpus of the pilot study is dominated by texts containing 2 and 3 moves, which are present in 28% and 32% of texts, respectively. 4 texts contain 4 moves (16%). 3 texts represent all 5 moves; also, three texts contain 1 move, which, in the latter case, stands at 12%. This number should be viewed together with the diverse layout of moves in the text shown in Table 2.

Steps form a subcategory of moves. In the corpus, steps are divided in M2 and M3, and the quantitative results are presented in percentages in Table 5. The numbers in brackets denote steps that have been split, where, besides the original function, they have signs of another step.

|

Steps |

Step: motiv |

Step: aim |

Step: struct |

Step: meth |

|

Number of texts |

5 |

18 |

18 (4) |

13 (1) |

|

Percentage |

20% |

72% |

72% (16%) |

52 (4%) |

Table 5. Steps of Move 2 and 3. The number in brackets represents the corresponding step splits

Step [[motiv]], found in 5 texts, in four cases is considered to be an addition to the goal, but in one case it replaces the wording of the goal, which usually appears explicitly with the signal word goal. The formulation of the goal was found only in 18 texts, although, in the methodological instructions, it is emphasized as an essential component of the abstract. The relatively high proportion of step [[struct]] – at 72% – is due to two reasons. Traditionally, in texts of abstracts, as in the introductions to bachelor’s theses, tasks are formulated to which the structure of the work is subject, and therefore they coincide. The second reason is the use of the indicative abstract, which includes a description of the textual structure. Step [[meth]], one of the three most important constituent parts of abstracts next to aim and results, appears in only 52% of texts. Again, the reason can be found in the fact that these abstracts are of the indicative type, which allows an indication of the use of methods, but does not specify them, thus resulting in the label [[struct]].

5.2 Equivalence of translations

Translations are often studied in connection with scientific article abstracts, emphasizing the usefulness of the acquired knowledge, also “when it comes to designing material for students […] with a view to helping new entrants into the academic discourse community who face difficulty with producing clear and coherent abstracts” (Pezzini 2003, 97).

Previous research also expresses the opinion that students who are not native speakers of English and are not studying English professionally should not abandon translation but instead create an abstract by using the 5-move model, as developed by Hyland, so that to ensure that they are “following the conventional English rhetorical moves’’ (Suryani & Rismiyanto 2019, 197).

All students at RTU are required to submit an abstract in English, and therefore students have to find a way to create the English text. Most of the time, students focus on the Latvian version of the abstract text and then use the Latvian version as the basis for the English text. As the English text is a requirement but not a distinct writing priority, students are likely to choose various machine translation tools to produce the English text, which is not forbidden as per the guidelines. Some of the abstracts analysed in this paper had a reasonably acceptable English version. Despite some awkward textual choices, the text could overall be seen as acceptable in terms of lexis, grammar, and overall content. In this context, it should be noted that Latvian students focus more on what was required in the university guidelines and not on the English language tradition of writing an abstract; therefore, the abstracts may fit the requirements set by the institution, but not the overall concept of what an abstract and its writing process is like in English.

Overall, the Latvian and English language abstracts were similar in length, and all of them contained the same information in both language versions. While most English versions of the abstracts seem to have at least some post-machine translation editing, as the majority of the texts are reasonably coherent in English, there were some linguistic issues that the authors might have failed to notice, perhaps due to time constraints. Sometimes, the wrong choice of verbs/grammatical constructions might cause confusion. For example, the sentence the construction of the smart private house wiring was created implies to the reader that the wiring in this project was physically completed, but, in the Latvian version of the abstract, it is only a draft of potential wiring that could be implemented.

Misuse or potential false friends were also observed, most strikingly in this example: The graphic part consists of 5 pages. With this, the student means five pages of drawings and graphs, and not explicit content. In two separate English translations, where the author means to describe the content of the thesis, there is a translation mishap calling it the job which is a literal translation from the Latvian word darbs used in the original paper=work. Similarly, typically used Latvian noskaidrot which means ‘to find out’, was most often translated to clarified in various tenses. While it is not a significant mistake overall, it appears several times in texts by various authors.

The quality of the translation also heavily depends on the quality of the original text in Latvian. Confusing original sentences hardly ever get clearer after translation, especially if the author chose not to re-read and edit the text. It can be found, for instance, in the following example of language use:

More extensive consideration is given to mobile verifiers, as they are based on the work itself. This example shows that the author was unable to explain their idea in the abstract – from this line, it appears as if there are mobile verifiers that are based on the findings of the bachelor’s paper research, when, in fact, the author’s research focused on evaluating the already existing mobile verifying apps.

Another issue that machine translation cannot solve and which solely depends on the human editor’s efforts are spelling errors that can occur in the original text. For example, one of the abstracts annotated for the corpus had a misspelling of the Latvian – tirgus ‘market’, the misspelling tigrus instead of tirgus turning into tiger in English. Some students might have too much trust in machine translation capabilities, without double-checking the results and the original text. In traditional translation study theory, it is often advised that a translation should be reviewed not only by the translator themselves, but also by a native speaker of the target language for correctness. The reviewing and editing process for the translation is likely quite short, or perhaps even non-existent, depending on the student’s perception of the importance of the English abstract of their bachelor’s thesis. Students know that their work will be definitely read by the reviewer and their advisor, but they likely do not treat the English version of their abstract as a significant text that represents their work. For graduate studies, especially at the doctorate level, abstract writing skills are important, and these skills should theoretically consistently improve, but, for bachelor’s students, this might be the only time they are tasked with translating an abstract to English.

This highlights the need to have a more in-depth look at the English language versions of the abstracts that will be annotated for this research project beyond the selected 25 texts discussed in this paper. While the abstracts are almost equivalent, with move-for-move and step-for-step matching in the Latvian and English versions, the language quality and editing importance could be another factor to include in the prospective AI tool to help the students write, especially while taking into account their level of experience with abstracts and their potentially limited experience with post-editing the scientific text machine translation output.

6 Conclusions and suggestions regarding corpus annotation and future work

Abstracts are an important, but so far undervalued text type in the programs of Latvian universities, and the annotation and more detailed analysis of the corpus in the pilot study makes it possible to draw several conclusions divided into two groups. First of all, there are some possible solutions to improve student academic writing: a detailed methodological instruction, including familiarization with the types of abstracts, and the lack of special in-depth academic writing courses at the undergraduate level. Since the abstract of the bachelor’s thesis is the first contact with this text type, and as the writing of the text most likely takes place within a limited period of time, the great diversity of moves patterns, multiple split cases and observed moves inconsistencies for signal words such as aim, results, conclusion are inevitable. As a result, in the process of annotating texts, it was necessary to focus on the content of the text, and, if necessary, to adapt to the fact that students used an atypical order of the moves at times. As a result, the annotation process is time-consuming, which is also reinforced by the fact that most abstracts consist of one paragraph and are relatively rarely structured. The issue of annotating informative and indicative abstracts according to the same criteria is debatable. For informative abstracts, it is possible to evaluate all moves and steps, whereas, for indicative abstracts, instead of methods, results and conclusions, there may be an indication of the structure, which is therefore the dominant move in the analysed corpus. Looking at the results of the analysis of the Latvian abstracts, it seems that there is no need to raise such a question of differences between an indicative and informative abstract in the language combination Latvian – English because:

1) there is no established genre tradition in Latvian;

2) often, in writing guidelines/instructions there is a requirement to translate close to the original text, and thus it results in awkward abstract texts in two languages, and neither of those actually meets the guidelines;

3) the type of text is standardized, and the orientation toward ISO requirements takes place regardless of the language used.

Differences between Latvian and English are possible at the microstructure level by selecting the appropriate phrases for each language.

The second group of conclusions summarizes the possibilities in regard to future research, both in terms of external factors and in terms of working with the corpus. The following should be added to the external factors in this context:

1) systemic and systematic error analysis;

2) development of methodological tools that would allow students to learn this process independently;

3) in the first stages of higher education, when writing semester papers and bachelor’s theses, the choice should fall in favour of the structured abstract form, as they have an easier-to-understand content which students can reproduce more easily and learn the basics of the text type;

4) teaching students the meaning of the type of text: focusing on learning logical text formation and how a publicly available text, such as an abstract, can be useful in their further careers;

5) a special set of academic writing classes with exercises in Latvian and English, including abstract types, signal words and related key phrases, verb tenses and order usage moves.

The question of dividing abstracts into study levels is debatable. Since students at the bachelor’s and master’s/doctoral levels have different prerequisites for abstract writing, it is desirable to separate the bachelor’s level in text formation from the other two. This does not preclude the use of the experience gained from the scientific article abstract research and adaptation to the level of undergraduate studies.

Acknowledgments

This article has been supported by research and development Grant No. C4835.ZPD.PI.0024P1 under the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility funded Project No. 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/003 “Implementation of Consolidation and Management Changes at Riga Technical University, Liepaja University, Rezekne Academy of Technology, Latvian Maritime Academy and Liepaja Maritime College for the Progress towards Excellence in Higher Education, Science, and Innovation”.

Data Sources

Registry of Final Theses of RTU – Rīgas Tehniskā universitāte. [Riga Technical University]. 2010–2025. Noslēgumu darbu publiskā datu bāze. [Public database of final theses]. Available at: https://www.rtu.lv/lv/studijas/bakalaura-limena-studijas/noslegumu-darbu-registrs. Accessed: 10 February 2025.

References

ANSI/NISO – ANSI/NISO Z39.14-1997 (R2015). An American National Standard. Developed by the National Information Standards Organization. Published by the National Information Standards Organization Baltimore, Maryland, USA. https://doi.org/10.3789/ansi.niso.z39.14-1997R2015

Asikuzzaman, Md. 2024. What is an Abstract? Definition, Purpose, and Types Explained. Available at: https://www.lisedunetwork.com/what-is-an-abstract-definition-purpose-and-types-explained/. Accessed: 10 February 2025.

BMF PBSP – RTU Būvniecības un mašīnzinību fakultātes (BMF) profesionālās bakalaura studiju programma “Siltuma, gāzes un ūdens tehnoloģija”. [RTU Faculty of Construction and Machinery, study programme “Heating, gas and water technologies’’]. 2024. Metodiskie norādījumi bakalaura darba ar projekta daļu izstrādāšanai un aizstāvēšanai. [Methodological quidelines for the development and defense of bachelor papers with a project part]. Rīga: RTU Izdevniecība. Available at: https://ebooks.rtu.lv/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2024/09/Metodiskie-noradijumi-bakalaura-darba-ar-projekta-dalu-izstradei-un-aizstavesanai.pdf. Accessed: 10 February 2025.

Busch-Lauer, Ines. 2012. Abstracts – eine facettenreiche Textsorte der Wissenschaft. Linguistik online 52 (2), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.52.293

Darabad, Ali Mohammadi. 2016. Move Analysis of Research Article Abstracts: A Cross-Disciplinary Study. International Journal of Linguistics 8 (2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v8i2.9379

DITF – RTU Datorzinātnes un informācijas tehnoloģijas fakultāte. [Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology]. 2023. Norādījumi studiju noslēgumu darbu noformēšanai. [Guidelines for formatting of final student works]. Rīga: RTU Izdevniecība. Available at: https://ebooks.rtu.lv/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2023/03/9789934226960-DITF_metodiskie_norad-2021-LV.pdf. Accessed: 10 February 2025.

Dubova, Agnese. 2009. Sekundārie teksti vācu un latviešu valodā. [Secondary texts in Latvian and German]. Zinātniskā komunikācija starpkultūru kontekstā. [Scientific communication in an intercultural context]. Agnese Dubova, Māra Leitāne & Dzintra Lele-Rozentāle, eds. Ventspils: Ventspils Augstskola. 83–100.

Frydrychova Klimova, Blanka. 2013. Common Mistakes in Writing Abstracts in English. 3rd World Conference on Learning, Teaching and Educational Leadership (WCLTA 2012). Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 93 (1), 512–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.09.230

Frydrychova Klimova, Blanka. 2015. Teaching English Abstract Writing Effectively. 5th World Conference on Learning, Teaching and Educational Leadership, WCLTA 2014. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 186, 908–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.113

Gobekci, Erika. 2023. Rhetorical structure and linguistic features of research article abstracts in the humanities: the case of Lithuanian, English, and Russian. Taikomoji kalbotyra 19, 33–56. https://doi.org/10.15388/Taikalbot.2023.19.4

Guidelines for RTU – Rīgas Tehniskā universitāte. Studiju departaments. [Riga Technical University]. 2014. Norādījumi studiju noslēgumu darbu noformēšanai. [Guidelines for the formatting of final theses]. Rīga: Rīgas Tehniskā universitāte. Available at: https://www.rtu.lv/writable/public_files/RTU_nordjumi_studiju_noslgumu_darbu_noformanai.pdf. Accessed: 10 February 2025.

Hüttner, Julia. 2010. The potential of purpose-built corpora in the analysis of student academic writing in English. Journal of Writing Research 2 (2), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2010.02.02.6

Hyland, Ken. 2000/2004. Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. Michigan Classics Edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

ISO – International Organization for Standardization. Documentation – Abstracts for publications and documentation. Documentation – Analyse pour les publications et la documentation. IS0 214–1976 (E), 1976.

Luthfiyah, Alek & Fahriany. 2015. An Investigation of Cohesion and Rhetorical Moves in Thesis Abstracts. IJEE (Indonesian Journal of English Education) 2 (2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.15408/ijee.v2i2.3086

Pezzini, Ornella Inês. 2003. Genre Analysis and Translation – an Investigation of Abstracts of Research Articles in Two Languages. Cadernos de Tradução 2 (12), 75–108.

Pratiwi, Dian, Budi Hermawan & Rd. Dian Muniroh. 2021. Rhetorical Move Analysis in Humanities and Hard Science Students’ Undergraduate Thesis Abstracts. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 546. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Conference on Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 2020), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210427.019

Putri, Fanny, Budi Hermawan & Rd. Dian Muniroh. 2021. Rhetorical Move Analysis in Students’ Abstracts Across Degrees. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 546. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Conference on Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 2020), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210427.025

Ramadhini, Tasya Maharani, Isti Tri Wahyuni, Nida Tsania Ramadhani, Eri Kurniawan, Wawan Gunawan & R. Dian Dia-an Muniroh. 2021. The Rhetorical Moves of Abstracts Written by the Authors in the Field of Hard Sciences. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 546. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Conference on Applied Linguistics (CONAPLIN 2020), 587–592. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.210427.089

Suryani, Fitri Budi & Rismiyanto. 2019. Move Analysis of the English Bachelor Thesis Abstracts Written by Indonesians. Prominent Journal of English Studies 2 (2), 192–199.

Swales, John M. & Christine B. Feak. 2009. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts. Vol. 1 of the Revised and Expanded Edition of English in Today’s Research World. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Šulovská, Denisa. 2022. Selected topics from academic writing. Comenius University in Bratislava, Faculty of Arts, Bratislava: STIMUL.

1 At the 29th international scientific conference The Word: Aspects of Research (2024), Laiveniece and Helviga presented the topic “Abstract of the study paper as a text genre: Main issues of structure and content”.

2 Exceptions are certain works written by foreign students in English. Their abstracts are translated into Latvian.