Kalbotyra ISSN 1392-1517 eISSN 2029-8315

2025 (78) 111–137 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Kalbotyra.2025.78.5

Bernhard Fisseni

Department for Linguistics

Institute for German Studies

Faculty of Humanities

University of Duisburg-Essen

Universitätsstraße 12

D-45141 Essen, Germany

E-Mail: bernhard.fisseni@uni-due.de

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3434-8964

https://ror.org/04mz5ra38

Deniz Sarikaya

Institute for Medical Engineering

Ethical Innovation Hub

Universität zu Lübeck

Ratzeburger Allee 160

D-23562 Lübeck, Germany

E-Mail: d.sarikaya@uni-luebeck.de

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8951-8161

https://ror.org/00t3r8h32

Department of History, Archaeology, Arts,

Philosophy, and Ethics (HARP)

Centre for Logic and Philosophy of Science

Vrije Universiteit Brussels

Pleinlaan 2

BE-1050 Brussels, Belgium

https://ror.org/006e5kg04

Bernhard Schröder

Department for Linguistics

Institute for German Studies

Faculty of Humanities

University of Duisburg-Essen

Universitätsstraße 12

D-45141 Essen, Germany

E-Mail: bernhard.schroeder@uni-due.de

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7847-1393

https://ror.org/04mz5ra38

Abstract. This paper outlines a plan for designing a corpus-linguistic project from which an analysis of frames specific to mathematical proof texts shall be derived. Previous work has already developed instances of frames for mathematical texts. We have argued that these frames are well suited to model how background knowledge enriches explicitly given information. To this end, a collection of mathematical texts needs to be annotated.

We describe the idea behind the corpus annotation, frame semantics and how we adapted frames for mathematical texts in particular by distinguishing between structural proof frames and ontological ones. Ontological frames for instance correspond to proof techniques, while structural frames model domain knowledge like exact definitions of mathematical structures. We describe annotation principles, explain qualifications annotators should have and how such annotations can be evaluated.

We explain potential linguistic research questions: The corpus will allow us to study the linguistic means by which frames are introduced and signaled. We plan to generalize beyond previous case-based analyses and to provide a foundation for broader empirical research on mathematical language and practice. We argue that these can be used in deeper semantic parsing and the development of interactive theorem-proving software. We furthermore assume that this perspective on mathematical text will also have implications on the philosophy of mathematics and its practice.

Keywords: frames, mathematical language, special languages, corpus annotation, mathematical proofs, philosophy of mathematical practice

________

Submitted: 01/11/2025. Accepted: 16/12/2025

Copyright © 2025 Bernhard Fisseni, Deniz Sarikaya, Bernhard Schröder. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1 Introduction

This paper is a whitepaper for a corpus-linguistic project. We aim to apply the theoretical concept of frames to mathematical texts. The project builds on earlier work within the Naproche project1 and first applications of the concept of frames to proofs involving the mathematical concept of induction. Frames allow to model how explicitly given information is combined with expectations deriving from background knowledge (see section 2 for more context).

In the context of mathematical proofs, the frame concept can be applied to model how the expectations that mathematical readers have due to their mathematical training allow them to interpret a mathematical text and to complement it with additional relevant information. This is particularly important in the case of mathematical proofs, which notoriously contain gaps (see section 3 for a discussion of relevant research questions).

Until now, research on frames in mathematical texts has been based on case studies. To be able to generalize our findings, we want to develop a corpus of mathematical texts annotated with structural and ontological frames, especially with regard to the introduction of new frames and the linguistic means of signaling frame use. For now, we will focus on proofs from mathematical textbooks involving various basic proof strategies.

We claim that the frame project can be helpful for natural language processing in general: The frame approach for mathematical text could be helpful in mathematical text parsing and in the usage of interactive and automated theorem provers. We have also already argued that the frame approach has philosophically interesting consequences for debates about mathematics (see section 3.1).

From a cognitive perspective we consider frames a useful tool for modelling learning and understanding of mathematical structures.

In section 2, we give a more detailed introduction to the frame concept and the research context. In section 3, we discuss how the corpus may be used in research of (the philosophy of) mathematical practice and language with respect to frame acquisition and usage.

This corpus annotation goes hand-in-hand with the creation of a library of structural and ontological frames.This library will contain structural information about the logical, conceptual and linguistic relationships between the frames in the library, comparable to a tag set or a set of grammatical relations in the background of traditional linguistic corpora. We will discuss the annotations guidelines to be further developed in this corpus linguistic project in section 4 and section 5 and discuss the evaluation of the annotation procedure und its results in section 6. Finally, after the conclusion in section 7, we return to the bigger picture in section 8.

2 The concept of frames2

In the context of mathematical proofs, readers of proofs have expectations due to their mathematical training. These allow them to interpret a mathematical text and to complement it with additional relevant information. Originally developed in linguistics, cognitive science and artificial intelligence, the concept of frame – nowadays very polysemous – is employed in models of how understanding combines explicitly given information with expectations derived from background knowledge.

2.1 Related framework

Minsky (1974) introduces frames as a general “data-structure for representing a stereotyped situation, like being in a certain kind of living room, or going to a child’s birthday party” (Minsky 1974, 1); frames are part of a frame-system. Despite the reference to “situations”, frames can be used to model concepts in the widest sense, already evidenced by the examples in Minsky (1974), from vision to story understanding.3

Each frame contains slots (or features), which can be (sub-)frames again. Slots can have default values or carry constraints. They are filled by concrete values. Some formal systems such as the Frame Representation Language (FRL, cf. Roberts & Goldstein 1977) permit the ‘lazy’ calculation of values from others by attaching procedures to slots. For instance, a circle in Euclidean geometry, the centre and the radius suffice to describe the circle. Thence, we may calculate the circle diameter, if needed. Related to feature structures (see, e.g., Carpenter 1992), later formalizations of the frame concept use an inheritance hierarchy of types to constrain both the proliferation of features and their values.

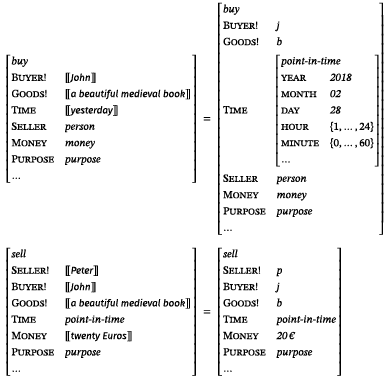

FrameNet4 is an important linguistic project using frames. Its hierarchical model of (mainly) verb semantics defines frames whose main constituents are the participants and their semantic roles. Frames are evoked by verbs; they provide roles that can be taken on by entities in the discourse universe. These roles can be either core or non-core roles, which captures the salience and optionality of the roles within a frame. For example, the FrameNet frame Commerce_buy has the core roles Buyer and Goods, while Seller, Money and Means (e.g., cash vs. check) and many others are non-core roles. Differences in role assignment capture semantic (and pragmatic) differences between verbs, as in the following example. Here, the explicitly realized frame elements are annotated with their roles:

(1) [Buyer John] bought [Goods a beautiful medieval book] [Time yesterday]. [Seller Peter] sold [Goods a beautiful medieval book] to [Buyer John] for [Money twenty Euros].

The frames representing buying and selling can be represented in a feature-value matrix as follows. The example in Figure 1 shows the buy frame, also illustrating subframes (in the Time field). An exclamation mark indicates core roles, and the semantics of the expression is described by double brackets. Point-in-time, person, money, purpose are type labels constraining potential fillers. We abbreviate the frame, indicating this with the ellipsis dots, thus omitting slots that have not been realised explicitly. By convention, a description in this way is generally partial (and thus ellipsis dots are not really needed).

Figure 1. A frame representation buying and selling a book as in the sentences of example (1). ! marks core roles

While both sentences evoke similar frames, the Seller slot need not be filled in the first case. However, it is present and could be filled, just as the Time slot specifying when the transfer occurs is present (but usually non-core) with most verbs and can be filled with more or less specific values.5

The concept of frame has been developed further in linguistic and philosophic projects recently, most notably in Düsseldorf in the SFB 991: Die Struktur von Repräsentationen in Sprache, Kognition und Wissenschaft (see, e.g., Gamerschlag et al. 2014; Gamerschlag et al. 2015), exploring how frames are connected to the semantic category of functional concepts (see Löbner 2015), and also investigating the history of scientific language and even connecting to discourse analysis (see e.g. Ziem 2008; Ziem 2014). With respect to the formal representation of frames, Petersen (2015) develops a model using feature structures (closely related to those explored by Carpenter 1992) and highlights the connection between frames and functional concepts. In the realm of mathematics the frame concept was first used in the context of didactics by Davis (1984). From a constructivist perspective Davis (1984) models the possibly erroneous and over-generalized individual knowledge of learners by frames. In this approach frames are a tool for the modelling of individual conditions for success or difficulties in learning processes. Many of the frames causing errors are overgeneralizations of mathematical knowledge acquired up to a certain stage, as, e.g., a frame of binary operations equipped with features of addition which is transferred to multiplication and leads to invalid calculations like 4 × 4 = 8 (Davis 1984, 111–113). In other cases, Davis (1984) argues that explanations for certain mathematical phenomena given by students depend on very basic pre-mathematical frames.

Modelling inductive proofs, Fisseni et al. (2019) see frames as guiding the processing of proofs based on usual mathematical practice. Carl et al. (2021) relate the frames approach to concepts of understanding and especially Avigad’s (2008) ability-based account of understanding mathematical proofs. Fisseni, Sarikaya & Schröder (2023) discuss how the concept of frames can be used to explore and explain the notion of innovation in mathematical practice.

The approach to applying the frame concept to mathematical proofs taken in this paper builds on the three aforementioned papers. It hypothesizes, as stated in the introduction, that (at least) two kinds of frames play a crucial role. Structural frames on the one hand schematically model the structure of proofs and definitions, similar to what Engel (1999) presents as proof techniques. Ontological frames on the other hand model domain knowledge: mathematical structures and typical patterns of expressions referring to them and their elements. Even if this distinction between structural and ontological frames is assumed to be heuristic and depends on the approach and field of the proof, it is useful for the investigation of mathematical texts and therefore will underlie our annotation.

The mathematical subfield and the type of text determine expectations regarding presence and explicitness of proof elements, as attested to by the differences between, e.g., textbooks articles in a mathematical journal. Frames, formalizing these expectations, bridge the gap between the text and more formal representations. Handbook articles on specific areas often present proof techniques; these can be understood as building blocks for frames that can also be used in innovative ways.

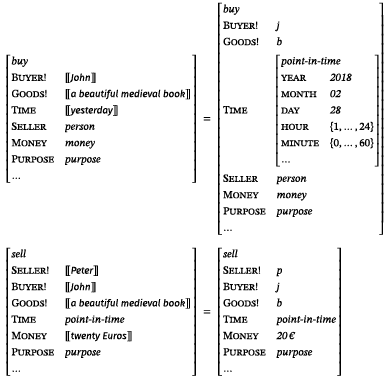

2.2 Interaction of frames, introducing the frame of induction

In frame systems, frames can interact slots of one frame can be filled from neighbouring, sub- or superordinate frames. For instance, the form of an induction depends on the underlying inductive type. The general structure in Figure 26 gives the typical parts of the induction proof such as the Base-Case, the Induction-Step and the Induction-Variable. As the form of an induction on some type is also dependent on the structure of said type, the mentioned slots are complemented by those for the Induction-Signature and the Induction-Domain. The non-recursive Base-Constructors of the latter provide the cases in the Base-Case of the induction, and it Recursive-Constructors derive the ‘successors’ of the base values, thus informing the Induction-Step.

This explicit frame structure (defined in the appendix of Fisseni et al. 2019) allows multiple Base-Constructors and Step-Constructors. Types with one base constructor and one recursive constructor allow for a simpler, more specialized frame.

Structurally, a typical induction on natural numbers will contain one Base-Case and one Induction-Step. Often Base-Case concerns the element 0 or 1 and Induction-Step refers to the successor function, λx.x + 1, which given a natural numer returns the next one. When an induction is done on all even numbers, the step function can return the next even number, λx.x + 2.7

An induction on complex formulas contains Case-Proofs for each kind of atomic formulas in the Proof of the Base-Case, and one element in the Case-Proofs for each connective of the formal language in the Proof of the Induction-Step. Ontologically, the form of hypotheses of the Base-Case and Induction-Step are constrained by the Base-Constructors and Recursive-Constructors: The former by default concerns the value of one of the Base-Constructors and the latter applications of the Recursive-Constructors.

In the view adopted in Fisseni et al. (2019) and Carl et al. (2021), frames – both ontological and structural ones – have a conceptual and a form dimension. The latter consists in text-structuring elements, notational conventions and linguistic triggers. An example of a linguistic trigger are certain plural constructions like “L1 and L2 are parallel”, which presuppose a symmetric relation (here: parallel, meaning that L1 is parallel to L2 and – due to the symmetry – also that the inverse holds: L2 is parallel to L1) and thus trigger the ontological frame of symmetric relations (see, e.g., Cramer & Schröder 2012).

In this bilateral sign-like conception frames deviate from Fillmore’s original understanding of frames as a mere representation of meaning. We chose this approach because structural frames in mathematics do not just define slots and their semantic relation, but also on different levels abstraction influence how proofs are “told”. This comprises, e.g., the choice of variables and notation at lower levels of abstraction, and the conventional order of proof parts at higher levels. The latter reminds of event sequences in narrative texts and is clearly related to aspects of cognitive organization.

Figure 2. InduInduction-Domain and Induction-Variable are displayed as sub-frames and connected to different places in the Proof sub-frame by structure sharing (indicated by boxes)

In this respect our frames resemble linguistic constructions in the sense of construction grammar as advocated by Goldberg (2006) and others: Like constructions, frames are organized in type hierarchies of more general and more specialized frames. Similar to the acquisition of linguistic constructions in constructivist language acquisition approaches (cf. Tomasello 2005), more general frames are usually acquired by generalization from more specific frames. Despite these parallel conceptualizations, frames differ from usual concepts of linguistic constructions as the restrictions on the form side are less strict. Most frames can be evoked by a huge range of formal realizations and hints, such as certain argumentation patterns. The form-concept relation is less transparent and more abstract compared with constructions usually discussed in linguistics.

3 Research questions

In this section, we present some research questions we want to address, and which would profit from a corpus such as the one we are designing.

3.1 Philosophical research questions

Since mathematical texts play a role in what mathematicians do, it can be expected to make a contribution for the study of mathematical practice. This means that we can expect results relevant to the (relatively) newly formed discipline of the philosophy of mathematical practice, which is currently stressing the need to incorporate the work of mathematicians into philosophical considerations on mathematics. Or in the words of a founding member of the Association for Philosophy of Mathematical Practice created in 2009, P. Mancosu:

[A]nyone familiar with contemporary philosophy of mathematics will be aware of the need for new approaches that pay closer attention to mathematical practice. (Mancosu 2008, preface)

While this community is still a minority, it is constantly growing. If we begin to focus more on the practice of working mathematicians, rather than focusing on purely metaphysical questions of the status of numbers, it becomes interesting to use existing frameworks from philosophy of science. We can note here that the frame approach has already been used in philosophy of science in general (Kornmesser 2018). This opens up the possibility to discuss the issues raised in the SFB 991 at the University of Düsseldorf8 for the philosophy of mathematics.

Text is a crucial medium for the transfer of mathematical ideas, agendas and results in the scientific community and in the context of education. This makes the focus on mathematical texts a natural and important part of the philosophical study of mathematics. Moreover, it opens up the possibility to apply a huge corpus of knowledge available from the study of texts in other disciplines to problems in the philosophy of mathematics. Big data studies of the corpus of all texts in the ArXiV are reported by Sørensen et al. (2024) and Johansen et al. (2022). But these texts are of course not meaningfully annotated, even though there is some structure gained from those articles that also upload their LaTeX code, like the proof environment (\begin{proof} … \end{proof}) often annotating which part of the text corresponds to proofs.

In earlier articles we already sketched parts of the philosophical impact of the frame approach. Carl et al. (2021) argued that many aspects of a prominent operationalization of understanding can be explained in terms of frames, for instance frame-identification as the ability to give a high-level outline. Fisseni, Sarikaya and Schröder (2023) talked about aspects of novelty and the connection of far-apart fields of mathematics. Here frames were used to explain, among others, how different perspectives on an object can make different questions salient and how notational systems and metaphors can motivate new steps that can then later be properly embedded into a theory. We suspect that many philosophical debates might benefit from the concept of frames, including questions on explainability, notations, questions of (national) styles of mathematics. We also sketched some future case studies, like the development of the forcing technique in set theory.

Finally, the frame approach may motivate the semantic view of theories. This view states that a theory can be identified with a collection of its models, rather than with a set of its true statements. Some of those models have another status than other, they are intended models. This can be read in straight forward Tarskian style, i.e. we read model as defined in the mathematical discipline of model theory. This relates to ontological frames, as ontological frames do not only capture the definition of an object, but we could develop a routine that ‘guesses’ what would be expected fillers. For instance, when dealing with a topological space, we may assume that in addition this space is likely a Hausdorff space. A reader could simply then fill in a metric space or even R as their paradigmatic example for a space. This would be wrong, at least in full generality, but it could work in many cases. Anyhow it might simply show that the frames of the author (or a community at large) are non-ideal, and hence do not actually capture the theory fixed by the axioms, for instance when non-topologists most of the time (wrongly) implicitly assume that topological space is a metric space.

This also shows in another notion related to structuralism, namely theory-nets. As frames are organized in an inheritance hierarchy, we can map out whole theories of mathematical structures. This is highly parallel to thoughts of specialization discussed for empirical theories.

Specialization introduces another type of relation among theory-elements to account for the inner structure of theories. A large number of scientific theories, in the ordinary sense of the term, have been reconstructed in the form of a tree-like structure with a basic theory-element at the top and several branches of more special theory-elements. The underlying idea is that any intended application of any specialized theory-element T is also an intended application of the more basic theory-elements being higher up in the hierarchy. Through specialization, the substantial laws of different theory-elements can be superimposed (Andreas & Zenker 2014).

To take an example take the theory-net of algebraic structures. We do not start with the group axioms per se, but with different models or examples. This mimics how we learn and also the historical developments. We study the integral numbers long before the algebraic structure of a ring and before the group structure of (ℤ, +). Frames are learned by examples, and we keep paradigmatic examples in our mind. This semantic view of theories can be associated with structuralist thinking, where a theory is not just seen as a set of truths (or a set of axioms and its deductive closure) but putting models forefront and the relation with each other. So each theory comes with paradigmatic examples. Groups are introduced after and relying on the study of natural numbers, whole numbers and symmetries. Often, we observe additional structure (namely the ring structure), but time shows that there are non-ring groups that are interesting as well. We can even study algebraic structures which are weaker than groups, but those have been less successful, i.e. are not much used, in current practice.

A few further directions we also mentioned as possible future works in the quoted papers are questions of the identity of proofs. It is clearly not necessary for the actual text of two proof texts to be identical. Being subsumed under the same frame and having (in some sense) equivalent fillings of the slots may be a better identity criterion.

Frames can also help to think about the discussion around the derivation-indicator view (see, e.g., Azzouni 2004; Carl & Koepke 2010), as it describes a possible intermediate step. Whether this is really an intermediate step to a derivation is of course up to discussion.

Finally, it is to be stressed that frames might well relate to something cognitively real opening a window to many questions of the epistemology of mathematics.

3.2 Linguistic research questions

As mentioned in the introduction, we want to study the acquisition and usage of frames in mathematical texts.

One point of departure is the differentiation between ontological and structural frames sketched in section 2.1. As this distinction is heuristic, we can characterize annotation in the following way: High-level annotation mainly concerns the identification of structural frames, and determining potential triggers (for instance, by induction) and fillers of frame slots (for instance, the induction anchor).

Structural frames are high-level structures because these frames generally connect several phrases across the proof, which fill different slots one by one. Ontological frames tend to act as fillers, and their slots are mostly filled immediately in definitions or declarations.

We assume that slots follow certain structural patterns. For instance, a typical induction anchor contains fixing a variable, a typical induction step contains a predication about two discrete values a natural ‘step’ apart; these two patterns also indicate the higher-level frame of induction. We call such structurally marked constructions frame indicators; these give less clear indication of frames, but a combination of indicators with a suitable context may be sufficient to trigger a frame. (Instances of) ontological frames are used/presupposed as fillers and therefore referenced in formulaic or linguistic expressions. Structural frames, on the contrary, are assumed to be expressed across several sentences.

Frames model how explicit and implicit information are combined with background knowledge. This connects well with a typical feature of mathematical proof texts: They often contain many gaps that are left – to quote a classic phase ‘as an exercise to the reader’. Omissions may include non-trivial steps or even the full omission of (large parts of) proofs. The reader is expected to be able to ‘fill in the details’.

Another particularity of mathematical proofs is that they often contain explicit marking, often combined with numbering, for text structure such as definitions, theorems, and proofs, at times even of single formulas. Broader study of these patterns will allow us to shed some light on the question how pervasive these patterns are, and how they interact with the introduction and use of frames.

On the linguistic side of things, the outlined project aims to provide insights into the structuring of texts and the management of discourse referents by frames for mathematical (proof) texts. This goal already started early in the mentioned Naproche project (Schröder & Koepke 2003; Fisseni 2003).

Unlike many other text types, the intended semantic meaning of a proof text can often be reconstructed quite unambiguously. This makes this text type an ideal research case for studying the interplay between text/process structuring and ontological frames. Therefore, we claim that this work will be a great test case for Natural Language processing in general. This application scenario allows for studying the feasibility of algorithmically constructing a (logically) largely unambiguous text interpretation (e.g., in the sense of Proof Representation Structures as described in Cramer et al. 2009; Cramer, Koepke & Schröder 2011) using frame-based techniques in a relatively ideal domain.

Basically, our hypothesis is that basic frames are introduced by various explicit indicators. For ontological frames, we expect introduction by definitions and the explicit introduction of notational means. In the case of structural frames, we expect initially the explicit marking of the structuring of the proof and explanations of this structure. It is an empirical question to which extent the order of elements follows a conventional order or is varied in mathematical text.

For frames that are already known to the reader, we want to study how they are signaled. We expect that this is done by a variety of linguistic means, including anaphoric references, conventions of function or variable names and potentially typical triggers or indicators. The corpus will allow us to evaluate the conditions under which these means are used, and whether they depend on context.

4 Corpus annotation: General considerations

The corpus as envisaged in this article is designed to allow linguistic and philosophical investigation of frame usage in mathematical texts.

The corpus will be annotated using standard formats to ensure interoperability and reusability.9 In our area, the relevant specifications are the TEI10 guidelines for text encoding, but also the MMT11 framework for mathematical knowledge representation. We focus on TEI compatibility here (see section 4.2).

To start in as theory-neutral a way as possible, initial annotation will be surface-oriented. This means that we only annotate stretches of text with respect to the role they play in mathematical frames we assume they represent. Specifically, we do not annotate information that is only implicitly given or must be supplemented by semantic inference and type-shifting (see next section for examples).

We thus distinguish the following components of annotation process: Going bottom-up, identifying shallow frame constituents (structural patterns) that, by default, can be viewed as slot fillers (among these, indicators) and frame triggers. Due to the recursivity of frames, however, not all fillers can be shallow constituents, but sometimes even full frames will fill a slot.

Structural frames are not necessarily explicitly introduced by any fixed lexical items. In a proof by induction any overt reference to induction, inductivity etc. may be missing. In some cases, the relevant frame can only be inferred by the logical properties and the relation of its arguments. In this respect frame annotation may resemble the proposal of a “‘loose’ layer” of inferred frames in addition to a “‘strict’ FrameNet-compatible lexical layer” (Remijnse & Minnema 2020, 13). The essential difference to these layered approaches is that our inferred structural frames do not overlay lexical frames. Contrary to the flat conception of lexical frames structural mathematical frames are recursively nested with a increasing tendency of lexical grounding of frames closer to the leaves of this nested structure.

Determining frames, which is a mixed process of top-down hypotheses and bottom-up pattern recognition (triggers, configurations of indicators), including assigning shallow and recursive constituents to slots. The latter includes identifying those fillers which are not explicit in the text.

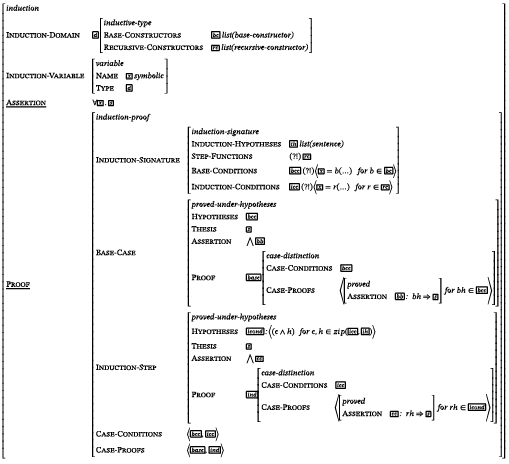

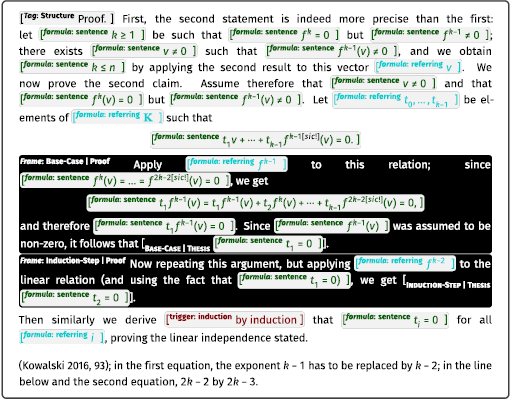

In the example proof of Figure 312, the fact that it is a proof by induction is mentioned explicitly only in the very last sentence. For the expert reader the proof strategy becomes clear in the course of reading by the type of claim, by the subgoals of the proof, by the demand to repeat the argument, and finally the explicit mention of the trigger word induction. So, the structural frame of a proof by induction could assumed as a top-down hypothesis, and its slots can be filled by the respective proof parts.

Figure 3. Example proof without annotation

Figure 4. Example proof from Figure 3 with annotations

To lay a good foundation for the high-level annotation, it is desirable to develop a surface-level annotation which provides categories that are candidates for triggers and ontological frames, but also treats mathematical formulas and uses linguistic preprocessing to guide annotators (see next section).

Based on previous work on frames and mathematical language, the following correspondences between linguistic structure and frame structure are expected; in these, we must take into account that mathematical text uses formulas both as referring and as sentence-valued expressions. Therefore, mathematical formulas will be annotated and tentatively tagged for both uses. A deep annotation of formulas is not intended at this stage. To a large extent the syntactic structure of formulas could be parsed automatically, but semantic ambiguities remain to be resolved. a(b − 1) could mean a function a applied to the argument b − 1 or the product of a and b − 1. For our purposes the annotation of frame indicators (see below) within formulas and of parts of formulas which are targets of slot references (e.g., “the sum on the left side of the formula”) could be relevant.13

First, a structural frame that is explicitly realized must be connected to a span of text, at least several sentences. Its slots can be of different size. Secondly, ontological frames are by default realized as referring expressions, i.e. noun phrases or variables. Of course, other realizations are possible (see Tanswell & Inglis 2022 for a discussion of some cases). Third, triggers (structural and ontological frames) must be connected to individual words or phrases. These, of course can be discontinuous, as German particle verbs (umformen, formen… um ‘transform an equation’) or analytic verb forms (wird… gezeigt ‘is shown’) which can be extended by adverbs (‘is presently transformed’). Fourth, indicators correspond to propositional units, i.e. at least one sentence or sentence-valued formula. Indicators may be discontinuous, as they may be separated by other indicators or fillers.

4.1 An example proof

The example proof from Kowalski (2016, 93) is shown in two versions: in Figure 3 without annotation, and in Figure 4, we illustrate the frame annotation without showing any XML; the annotation principles are sketched below. Chunking and pos-tagging are also omitted, but formulas are tagged as referring or sentence-valued. “Lexical units that do not play a role as triggers or indicators for the specific frames under discussion (e.g., let, since, therefore), have not been annotated in the example to keep it readable.

While the proof uses induction on natural numbers, it just mentions the induction frame (trigger!) late after giving an example for the step from the base case to the immediate successor. The clearest trigger thus is the phrase “by induction” in the last sentence. But there are several indicators before that like the step from t1 = 0 to t2 = 0 in the preceding sentence. That i is to be the Induction-Variable with i = 1 as the Base-Condition can be inferred from the step from t1 to t2 and the universal quantification. Only the Assertion is stated explicitly. The whole proof has to be reconstructed from the hint that in the step from i = 1 to i = 2 f k-2 has to be applied instead of f k-1, which leads to the general term f k-(i+1) for the step from i to i + 1.

4.2 Annotation principles

Annotation will be TEI-compatible, using stand-off annotation, i.e. annotations will be linked to the text by pointers. This allows us to add annotation layers that are structurally very different from the original structure.

The text will be recorded using standard-TEI segments and specific mathematical annotation, taking special care of numbering and labelling to allow for research on text structure. Mathematical text is usually written in the LaTeX14 system. As the TEI stylesheets15 do not allow conversion from (but only to) LaTeX format, we will have to build our own conversion, building on Pandoc’s16 TEI Simple conversion.

The following annotation will be in-line, as we consider it part of the text, and no structural divergence can arise: Text structure will be annotated using standard TEI elements, formulas will be annotated as such, and there will be linguistic annotation on the level of chunking.

Stand-off annotation will contain the following layers: First, linguistic annotation on the word level. To achieve optimal alignment between linguistic structure and annotation, we will annotate the text linguistically using chunking and POS-tagging (for the rationale, see below). Secondly, formula annotation. Formulas will heuristically be classified as sentence-valued or referring expressions (see below, section 4.3). Thirdly, frame annotation. Based semantically on typed feature structures (see, e.g., Carpenter 1992), this annotation layer will be implemented using TEI feature structures to the extent possible.

Coreference will not be annotated in the first phase, as this task can be complicated in cases such as plural entities (e.g., y and f(x)). This layer of annotation may be added in a later phase, and may be necessary to resolve certain slot fillers.

4.3 Before manual annotation

The following automatic linguistic preprocessing will be applied and provides goals for pointers of stand-off annotation. In cases linguistic preprocessing leads to inadequate results, it will have to be corrected in manual annotation.

First, sentences will be annotated with parts of speech (POS) to help identify referring expressions and hence reference to ontological frames. Also, trigger candidates (e.g., by induction, by contradiction) shall be marked. As such expressions may be formulaic, formulas and mixed expressions must be annotated and heuristically classified as sentence-valued (e.g., equations as in hence, a + b = 0) or referring expressions (e.g., simple variables or appositions like the equation a + b = 0). Interpretation of formulas is outside the scope of this step; it will be taken up later in frame analysis.

5 Annotation guidelines

Writing annotation guidelines is not trivial. In our case, the task is complicated by the fact that the goal structure is not necessarily close to the surface structure of the text, but is rather oriented towards a higher-level representation of proofs.

Lemnitzer & Zinsmeister (2015) list the following criteria for good annotation guidelines:

a) a list of all tag names (mostly descriptive abbreviations) together with their full names (category names),

b) definitions of the categories,

c) prototypical annotation examples for the categories,

d) tests that help to decide whether a category applies,

e) problematic examples with [correct] annotations,

f) typical confusion categories (i.e. competing tags) with examples. (Lemnitzer & Zinsmeister 2015, 102, our translation)

We will strive to meet these criteria. For reasons of space and avoidance of boredom, we cannot provide a full set of annotation guidelines here. Instead, we will discuss some of the challenges that arise in writing such guidelines and sketch our approach to these challenges. We will not give examples of tests or confusion categories here yet, but we will discuss some problematic examples.

As explained earlier, the resulting frame structure will (by default, but not necessarily) be much more complete than the text – filling the gaps –, so that both sub-frame structure and fillers may have to be inferred. This is different from, for instance, the linguistic annotation in FrameNet, which focusses on non-recursive structures with the verb as the base (and explicit trigger) of the frame, while our frames are recursive and need not have a unique and unequivocal trigger: an induction need not contain any explicit reference to induction.

5.1 Annotators

Annotators must be able to build up the frame structure for themselves. As this is a hermeneutic process guided partly by the proof text, but also by mathematical culture, annotators must be educated enough in mathematics to understand the text and supplement the missing parts. These aspects of mathematical practice can be imparted in training workshops or self-paced learning.

It is questionable whether it is possible to find annotators with advanced competence. Hence, annotators will be instructed to stick to the units determined by preprocessing if possible.

5.2 How to start manual annotation

In the beginning, annotators will be presented with the text of the proof. Annotation spans will be aligned with certain linguistic categories.

Based on this, annotators will mark up triggers and indicators as well as (corresponding) structural frames, and will build up the frame structure by assigning fillers to slots. The frame structure will be built up according to the structural frames, referencing triggers and indicators. Ontological frames will be marked up as they are encountered, but only those structures that are explicitly realized in the text will be annotated.

5.3 The frame library and the challenge of new frames

The annotation guidelines will contain a description of frames. The frame library will not be expanded during the project to achieve consistency. If frames are missing, annotators will be instructed to mark these cases and skip annotation. Later, the respective proofs will be reinspected, and the frame library will be revised and expanded if necessary. This may lead to re-annotation of other proofs, as well.

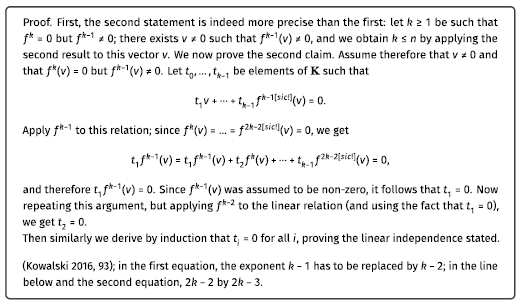

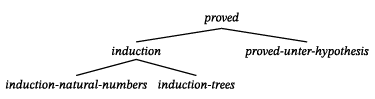

An excerpt of the inheritance hierarchy of frames in the proved family is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Inheritance hierarchy of frames in the proved family

5.4 Challenge avoided: Bridging structural and logical gaps

Logical gaps can occur on different levels, and are often covered by the classical statements left to the reader, is obviously true etc. Filling these gaps corresponds to completing the goal frame; however, there may be more than one way to do it.

Structural gaps occur in two cases. First, slots or sub-frames may be only partially realized, i.e. only a slot of a sub-frame is realized. This can be annotated by linking the realization to its slot, but it begs the question how to resolve sub-frame types etc. Secondly, slot fillers may differ in abstraction from the slot value they must provide. An example is the step function. We again distinguish two cases. The step statement is often given by an instance of its application, i.e. in the induction step; alternatively, the step statement may be expressed by referring in a very abstract way (the next element, or similar). In either case, reconstructing the step function involves fine-grained interpretation and semantic typing.

How to bridge such gaps can be considered an empirical question. We have therefore decided not to annotate such gaps in the first phase. How to fill them best will be one of the first uses of the corpus.

5.5 Challenge avoided: Variable use

Certain values such as induction variables occur many times in a proof text. Annotating all instances manually is tedious but annotating them automatically may lead to incorrect results.

Complications arise from using variables of the same name in different scopes of the same text. For instance, a variable may be bound to a value in the induction anchor, but then used as a free variable in the induction step. Similarly, a variable may be fixed in a hypothesis, but then used as unbound in the conclusion.

We have therefore decided not to annotate variable use for now. Investigating how to best deal with variable use will be one of the first uses of the corpus.

5.6 Challenge: Resolving typing ambiguities

Annotation guidelines must give indications on how to deal with ambiguities. We now discuss examples of ambiguities, also sketching our approach to avoiding them or resolving them in context.

In annotating induction proofs, ambiguities arise between the step, the domain of induction and the function. This is based on an inner-theoretical choice: If the domain is constructed in a way that its constructor corresponds to the step function, one gets a proliferation of domains, i.e., induction on odd or even numbers, on numbers divisible by ten etc. If, on the other hand, one takes a number of basic types and treats the function as independent of the constructor, this results in many step functions. Logically, both approaches are equivalent, but they lead to different annotation strategies.

We have decided to follow the surface structure of the proof as much as possible, i.e., when an induction is performed on a certain type, we annotate this type as the domain of induction, and the step function is inferred from the text of the induction step. In case the proof is so sketchy that we cannot decide which approach is used, we follow the second approach, i.e., use a small number of basic types and infer the step function.

6 Evaluation

Whether annotation guidelines have the desired effect of leading to correct annotations and as few deviations as possible between different annotators should be evaluated in any corpus building project.

The evaluation can be based on metrics for inter-annotator comparisons. However, this cannot be done on the basis of kappa values such as Cohen’s kappa or Fleiss’ kappa alone, since it is not only a matter of categorizing data by assigning it to frames and slots, but also of annotating the textual extension on the form side of the frames and the relational assignment of slots to frames.

Since the requirements for a comparison of frame annotations are similar to those for the evaluation of parser output, the metrics of parser evaluation will be discussed here. We distinguish the mere comparison of two or more annotations from the evaluation relative to a gold standard as a reference annotation. Parser evaluation is usually done against a gold-standard. For our scenario we consider the greatest possible inter-annotator agreement based on the annotation guidelines to be developed and refined in an iterative process as the goal of the first step of the evaluation. If a high degree of agreement is attained, a gold-standard could be devised on this basis.

In our corpus annotation we will limit ourselves to structural frames and a flat annotation of ontological types at the structural leaves and annotation of frame triggers, as elaborated in the two preceding sections. This leads to non-cyclic tree graphs with possibly crossing edges.

If we disregard evaluation metrics which take specific error types of syntactic parsing into account, we essentially have four types of metrics (cf. Romanyshyn 2021).

In leaf-ancestor evaluation (cf. Sampson & Babarczy 2003), the paths from the root node to the leaves in the parse tree are compared for each word. The distances are measured by the minimum edit distance relative to the number of nodes in the parse tree of the gold standard. In this metrics errors near the tree root have a great impact because they affect more paths than errors lower in the tree.

Cross-bracketing (as e.g. defined in Caroll, Briscoe & Sanfilippo 1998) counts how many text parts are subsumed (bracketed) differently under frame slots by determining how many beginnings and ends of text parts do not match for the annotations to be compared. So, it can be used to determine whether the text parts that can be assigned to slots and frames match in different annotations. It is therefore a measure mostly for quality of the leaf-related parts of the annotation.

While the leaf-ancestor evaluation only determines the minimum editing distance for the paths from the terminal nodes to the root nodes, the minimum tree edit distance (TED)17 measures how many editing steps (adding, deleting and renaming nodes) are required to transform the given tree into the gold standard. Variants arise depending on the weighting of different editing operations. In the case of strongly divergent frame analyses, however, it can be difficult to find suitable editing strategies that lead to a minimization of the editing steps.

The ParsEval measures determine the number of constituents that have the same extension in the parse tree as those in the gold standard.18 The precision is defined as the ratio of the correctly determined constituents to the constituents in the parser output, the recall is the number of correctly determined constituents in the parser output in relation to the number of constituents in the gold standard. An F-score can be calculated on the basis of precision and recall as the harmonic mean of both values which could be weighted in favour of one or the other value. This measure only provides information about the extent of the text parts corresponding to the nodes in the parse tree and the number of nodes between root and leaves.

The classification of the constituents is not taken into account in the ParsEval base measure. In labelled precision and labelled recall, however, it is possible to determine how many matches there are in text extension and label.

In a more refined metrics of ParsEval, the errors in nodes can also be weighted depending on how far they are from the leaves. This is based on the assumption that faults closer to the root are more serious than faults closer to the leaves. In the evaluation of frames other forms of weighting could be taken into consideration.

In section 2, we mentioned the similarities and differences between our conception of structural frames and linguistic constructions. While both share their bilateral structure of form and meaning, we conceive frames as much less bound to the surface structure of the text. The textual borders of certain frames and their fillers may be more disputable than in the case of grammatical constructions. Therefore, essentially text extension-based metrics as cross-bracketing and ParsEval seem less suited for our purpose than metrics highlighting the tree structure as leaf-ancestor evaluation and TED.

Any metrics taking into consideration the node labels of the tree, i.e. frame types and slots, should regard that the types are differently distant from each other. A frame subtype is to be treated differently from a completely contradictory type assignment. Hierarchy-based measures for frame type distances could be a suitable approximation for the assessment of the quality of frame type matching. So, recognizing a proof correctly as an induction proof but being mistaken in the type of induction (e. g. induction-natural-numbers instead of induction-trees in the hierarchy fragment of figure 2 would nevertheless allow for a correct detection of slot fillers and would not make the annotation useless as a whole.

But it seems well motivated that any metrics should take the root distance into consideration. Mistakes higher up in the frame structure tree, i.e., principal misinterpretations of the proof structure, have more serious effects on the whole annotation than mistakes closer to leaves.

7 Conclusion

We have shown why the systematic creation of a corpus of mathematical texts annotated with structural and ontological frames can contribute to several research goals in linguistics, philosophy of mathematics and natural language processing and highlighted the challenges of designing annotation for this corpus.

8 Outlook

The corpus will allow us to study the linguistic means by which frames are introduced and signalled. We sketched the hypotheses above, and expect that using the corpus, we will be able to test and refine these hypotheses.

In section 5, we discussed the challenges of writing annotation guidelines for frame annotation, and we had to postpone some important aspects such as the filling-in of proof gaps and the study of ambiguities. The corpus will allow us to study these aspects in a broader context and refine the annotation and the guidelines for taking a next step in the hermeneutic spiral.

References

Andreas, Holger & Frank Zenker. 2014. Basic concepts of structuralism. Erkenntnis 79 (S8), 1367–1372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-013-9572-y

Artstein, Ron & Massimo Poesio. 2008. Inter-coder agreement for computational linguistics. Computational Linguistics 34 (4), 555–596. https://doi.org/10.1162/coli.07-034-R2

Avigad, Jeremy. 2008. Understanding Proofs. The Philosophy of Mathematical Practice. Paolo Mancosu, ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 317–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199296453.003.0013

Azzouni, Jody. 2004. The derivation-indicator view of mathematical practice. Philosophia Mathematica 12 (2), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/philmat/12.2.81

Bille, Philip. 2005. A survey on tree edit distance and related problems. Theoretical Computer Science 337 (1–3), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcs.2004.12.030

Black, E., S. Abney, D. Flickenger, C. Gdaniec, R. Grishman, P. Harrison, D. Hindle, et al. 1991. A Procedure for Quantitatively Comparing the Syntactic Coverage of English Grammars. Speech and Natural Language: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at Pacific Grove, California, February 19–22, 1991. Patti Price, ed. San Mateo, California: Morgan Kaufmann. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/H91-1060/. Accessed: 8 December 2025.

Carl, Merlin, Marcos Cramer, Bernhard Fisseni, Deniz Sarikaya & Bernhard Schröder. 2021. How to Frame Understanding in Mathematics: A Case Study Using Extremal Proofs. Axiomathes 31 (5), 649–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-021-09552-9

Carl, Merlin & Peter Koepke. 2010. Interpreting Naproche – an algorithmic approach to the derivation-indicator view. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Mathematical Practice and Cognition, 7–10.

Caroll, John, Ted Briscoe & Antonio Sanfilippo. 1998. Parser evaluation: A survey and a new proposal. International Conference on Language Resources and Ealuation. European Language Resources Association. 447–454. Available at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:7042755. Accessed: 8 December 2025.

Carpenter, Bob. 1992. The Logic of Typed Feature Structures. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511530098

Cramer, Marcos, Bernhard Fisseni, Peter Koepke, Daniel Kühlwein, Bernhard Schröder & Jip Veldman. 2009. The Naproche project: Controlled natural language proof checking of mathematical texts. Controlled Natural Language. Norbert E. Fuchs, ed. Berlin & Heidelberg: Springer. 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-14418-9_11

Cramer, Marcos, Peter Koepke & Bernhard Schröder. 2011. Parsing and Disambiguation of Symbolic Mathematics in the Naproche System. Intelligent Computer Mathematics. James H. Davenport, William M. Farmer, Josef Urban & Florian Rabe, eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-22673-1_13

Cramer, Marcos & Bernhard Schröder. 2012. Interpreting Plurals in the Naproche CNL. Controlled Natural Language. Michael Rosner & Norbert E. Fuchs, eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31175-8_3

Davis, Robert B. 1984. Learning mathematics. The Cognitive Science Approach to Mathematics Education. Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Engel, Arthur. 1999. Problem-solving strategies. New York: Springer.

Fisseni, Bernhard. 2003. Die Entwicklung einer Annotationssprache für natürlichsprachlich formulierte mathematische Beweise. Bonn: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Philosophische Fakultät Magisterarbeit. https://naproche-net.github.io/downloads/2003-Magister_Fisseni.pdf. Accessed: 8 December 2025.

Fisseni, Bernhard, Deniz Sarikaya, Martin Schmitt & Bernhard Schröder. 2019. How to Frame a Mathematician. Modelling the Cognitive Background of Proofs. Reflections on the Foundations of Mathematics: Univalent Foundations, Set Theory and General Thoughts. Stefania Centrone, Deborah Kant & Deniz Sarikaya, eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15655-8_19

Fisseni, Bernhard, Deniz Sarikaya & Bernhard Schröder. 2023. How to frame innovation in mathematics. Synthese 202 (4). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04310-3

Gamerschlag, Thomas, Doris Gerland, Rainer Osswald & Wiebke Petersen, eds. 2014. Frames and Concept Types. Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01541-5

Gamerschlag, Thomas, Doris Gerland, Rainer Osswald & Wiebke Petersen, eds. 2015. Meaning, Frames, and Conceptual Representation. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110720129

Goldberg, Adele. 2006. Constructions at Work. The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268511.001.0001

Hovy, Eduard. 2015. Corpus Annotation. Oxford Handbook of Computational Linguistics. Ruslan Mitkov, ed. 2nd edn. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199573691.013.011

Ide, Nancy & James Pustejovsky, eds. 2017. Handbook of Linguistic Annotation. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-0881-2

Johansen, Mikkel Willum & Josefine Lomholt Pallavicini. 2022. Entering the valley of formalism: Trends and changes in mathematicians’ publication practice – 1885 to 2015. Synthese 200 (3), 239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03741-8

Kornmesser, Stephan. 2018. Frames and concepts in the philosophy of science. European Journal for Philosophy of Science 8 (2), 225–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-017-0183-3

Kowalski, Emmanuel. 2016. Linear Algebra. Lecture Notes, ETH Zürich. Available at: https://people.math.ethz.ch/~kowalski/script-la.pdf. Accessed: 8 December 2025.

Lemnitzer, Lothar & Heike Zinsmeister. 2015. Korpuslinguistik. 3rd edn. Tübingen: Narr.

Löbner, Sebastian. 2015. Functional concepts and frames. Meaning, Frames, and Conceptual Representation. Studies in language and cognition. Thomas Gamerschlag, Doris Gerland, Rainer Osswald & Wiebke Petersen, eds. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press. 15–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110720129

Mancosu, Paolo, ed. 2008. The Philosophy of Mathematical Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199296453.001.0001

Minsky, Marvin. 1974. A Framework for Representing Knowledge. MIT AI Laboratory Memo. Cambridge, MA, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology/MIT.

Petersen, Wiebke. 2015. Representation of concepts as frames. Meaning, Frames, and Conceptual Representation. Vol. 2. Thomas Gamerschlag, Doris Gerland, Rainer Osswald & Wiebke Petersen, eds. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press. 43–67. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110720129

Remijnse, Levi & Gosse Minnema. 2020. Towards Reference-Aware FrameNet annotation. Proceedings of the International FrameNet Workshop 2020: Towards a Global, Multilingual FrameNet. Tiago T. Torrent, Collin F. Baker, Oliver Czulo, Kyoko Ohara & Miriam R. L. Petruck, eds. Marseille, France: European Language Resources Association. 13–22. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/2020.framenet-1.3/. Accessed: 8 December 2025.

Roberts, R. B. & Ira P. Goldstein. 1977. The FRL Manual. Cambridge, MA, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology/MIT.

Romanyshyn, Mariana. 2021. The Dirty Little Secret of Constituency Parser Evaluation. Available at: https://www.grammarly.com/blog/engineering/the-dirty-little-secret-of-constituency-parser-evaluation/. Accessed: 8 December 2025.

Ruppenhofer, Josef, Michael Ellsworth, Miriam R. L. Petruck, Christopher R. Johnson & Jan Scheffczyk. 2006. FrameNet II: Extended Theory and Practice. Berkeley, California: International Computer Science Institute.

Sampson, Geoffrey & Anna Babarczy. 2003. A test of the leaf-ancestor metric for parse accuracy. Journal of Natural Language Engineering 9 (4), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324903003243

Schank, Roger C. & Robert P. Abelson. 1977. Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding: An Inquiry into Human Knowledge Structures. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum.

Schröder, Bernhard & Peter Koepke. 2003. ProofML – eine Annotationssprache für natürliche Beweise. Sprachtechnologie für die multilinguale Kommunikation – Textproduktion, Recherche, Übersetzung, Lokalisierung – Beiträge der GLDV-Frühjahrstagung 2003. Uta Seewald-Heeg, ed. St. Augustin: Gardez! 428–441. https://doi.org/10.21248/jlcl.18.2003.48

Sørensen, Henrik Kragh, Sophie Kjeldbjerg Mathiasen & Mikkel Willum Johansen. 2024. What is an experiment in mathematical practice? New evidence from mining the Mathematical Reviews. Synthese 203 (2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04475-x

Tanswell, Fenner Stanley & Matthew Inglis. 2022. The Language of Proofs: A Philosophical Corpus Linguistics Study of Instructions and Imperatives in Mathematical Texts. Handbook of the History and Philosophy of Mathematical Practice. Bharath Sriraman, ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19071-2_50-1

Tomasello, Michael. 2005. Constructing a Language. A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press.

Ziem, Alexander. 2008. Frame-Semantik und Diskursanalyse – Skizze einer kognitionswissenschaftlich inspirierten Methode zur Analyse gesellschaftlichen Wissens. Methoden der Diskurslinguistik. Ingo H. Warnke & Jürgen Spitzmüller, eds. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter. 89–116. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110209372.2.89

Ziem, Alexander. 2014. Von der Kasusgrammatik zum FrameNet. Grammatik als Netzwerk von Konstruktionen. Sprachwissen im Fokus der Konstruktionsgrammatik. Alexander Lasch & Alexander Ziem, eds. Berlin: De Gruyter. 261–290. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110353693.263

1 Available at: http://www.naproche.net. Accessed: 5 December 2025.

2 The text of this section is closely based on the corresponding section 2 of Carl et al. (2021).

3 Schank & Abelson (1977) develop the related concept of scripts, which adds a temporal dimension. Our use of frames also resembles scripts if one reads the constituents of certain proof structural frames (as introduced below) as a plan for linear text organisation.

4 See, e.g., Ruppenhofer et al. (2006) and the project’s website at https://framenet.icsi.berkeley.edu. Accessed: 1 December 2025.

5 Even core roles can be omitted sometimes, as in John finally sold his car. Salience and optionality must hence be considered to be gradual.

6 The structure is adjusted to multiple Base-Constructors and Step-Constructors, taken from the appendix of Fisseni et al. (2019); a simpler version can be defined for types with one base constructor and one recursive constructor.

7 Alternative formalizations are possible, see section 6.

8 See https://frames.phil.uni-duesseldorf.de/ and the publications cited in the previous section.

9 As is standard by now, software tools for annotation and management of the corpus will be released as open source wherever possible.

10 Available at: https://tei-c.org/. Accessed: 1 December 2025.

11 Available at: https://uniformal.github.io. Accessed: 1 December 2025.

12 The annotated version is shown in Figure 4.

13 A reviewer of this paper asked about annotation of formulas “as they are read”. This would be a kind of “normalization” of mathematical texts, which could lead to lexical targets for FrameNet-frames. As we do not assume that there exists a canonical reading for formulas in general, the definition of special formal triggers and indicators seems more feasible at this stage.

14 Available at: https://www.latex-project.org/. Accessed: 1 December 2025.

15 Available at: https://github.com/TEIC/Stylesheets. Accessed: 1 December 2025.

16 Available at: https://pandoc.org/. Accessed: 1 December 2025.

17 For a survey of problems related to computing the TED see Bille (2005).

18 For the original introduction of the ParsEval concept see Black et al. (1991).