Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2019, vol. 73, pp. 79–93 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2019.73.35

The Symbolic and Propaganda Message of the Heraldic Programs in Two 17th-Century Marriage Prints (Epithalamia) of the Pacas Family

Anna Sylwia Czyż

Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University

in Warsaw Institute of History of Art

K. Wóycickiego 1/3, bud. 23, 01-938 Warszawa

aniaczyz@poczta.onet.pl

Summary. This article presents two printed epithalamia from the 17th c. related to marriages contracted in the Pacas family. Each of them was adorned with a graphic decoration conforming with the allegoric meaning of the Gozdawa coat-of-arms. This determined not only individual virtues but also, together with the relevant quotations and symbols, became a prognostic of a satisfactory marital life. It also demonstrated the connections of the Pacas family, which were crucial in terms of strengthening the position of both the family and its individuals against public and family issues.

Keywords: Pacas, epithalamium, stemmata, coat of arms, Gozdawa.

Du XVII a. santuokiniai leidiniai (epitalamijos), priklausantys Pacų šeimai: simbolinė ir propagandinė žinutės

Santrauka. Straipsnyje pristatomos dvi spausdintos epitalamijos, priklausančios XVII a. ir susijusios su Pacų šeimoje įteisintomis santuokomis. Abiejų leidinių grafiniai papuošimai sutampa su alegorine Gozdawos herbo reikšme. Tai turėjo nusakyti ne tik pavienes asmens dorybes, bet, turint omeny ir su tuo susijusias citatas bei simbolius, numatyti gerą vedybinį gyvenimą. Taip pat ši puošmena demonstravo Pacų šeimos ryšius, kurie buvo būtini siekiant sustiprinti tiek šeimos, tiek ir atskirų jos narių laikyseną susiduriant su viešomis ir šeimą liečiančiomis problemomis.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Pacai, epitalamija, stemmata, herbas, Gozdawa.

Received: 5/2/2019. Accepted: 8/10/2019

Copyright © 2019 Anna Sylwia Czyż. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

In the early modern era, a coat of arms was a clear expression of its bearer’s given place in the social and family hierarchy; it also highlighted their aspiration and views, and thus played an extremely important role. As a result, official and family advancements, or even the desire to achieve them, were linked not only to the necessity of having a well thought-out political foundation (a system of seats with a residence linked to a church-mausoleum of an adequate scale, material and exposition), but also with the obligation to use these signs in the process of individual and family self-creation. A coat of arms in that context meant a legitimizing symbol that was affixed not only to the buildings founded, their décor, and furnishings, but also on various occasional prints, including marriage prints, which became an important means of communicating particular content, given the fact that the family celebrations of the elites in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were public.

The Pacas family followed this scheme and linked their social advancement to the activity in the field of art, more so because their family had long remained outside the main political scene of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.1 At the end of the 15th c., they slowly started gaining a permanent place in the public arena of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but the whole process was really boosted by the position of Treasurer (1630) and then Lithuanian Vice-Chancellor (1635) attained by Steponas Pacas (d. 1642), who represented the older line and laid the economic and image foundations for the family’s domination in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, created in the 1660s–1680s by his son Kristupas Zigmantas (1621–1684), together with the Lithuanian Hetman Mykolas Kazimieras (1624–1682), when the majority of important civil, military, and church offices were practically in their hands.

Steponas Pacas was also the first in the family to leave substantial investments behind him, including those in the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, proof of the family’s imperial aspirations but also its well-considered foundation policy. Its activity in the field of art also included prints for special occasions, during which the symbolism of the Gozdawa coat-of-arms, the key element of the individually created heraldic programs, was interpreted.2 In a multilevel message directed at various groups of nobility and the elites of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the legend about the affinity of the Pacas family to the de’Pazzi family from Florence and the Roman origins of their common ancestor, Cosmus Pacius, was used. It was devised by the vice-chancellor himself, in a diary from his voyages in 1624–1625 together with Vladislovas Žygimantas Vaza.3

Print from the Marriage of Sofija Pacaitė and Jonas Kazimieras Chodkevičius

The wedding of Steponas Pacas’s daughter, Sofija Pacaitė (1618–1665), to the Grand Lithuanian Equerry Jonas Kazimieras Chodkevičius (1616–1660) took place on August 31, 1636 in Vilnius and was a “solemn […] sumptuous wedding” (“z wielką pompą […] huczne wesele”).4 It was accompanied by the then-customary literary works, of which at least one, the epithalamium,5 divided into songs, odes, and prognostics, was published in printed form. The author of the song who printed and delivered it during the wedding reception was Boguslavas Sluška (pl. Bogusław Słuszka), son of the Voivode of Minsk and a student at the Vilnius Academy. The publication was initiated by Steponas Pacas, which is why the Lithuanian Vice-Chancellor and his wife Ana Rudamina-Dusiackaitė (d. 1643) were cited in the title.6

The author of the epithalamium used a concept by Kasper Rudowicz,7 which had been already tried out a few years earlier, i.e., the interpretation of the Gozdawa coat-of-arms as a lily full of virtues and the family as a garden where they bloom,8 starting the work with the words: “Gryphs CHODKIEWICIANUS, in Vernantissimo PACORUM viridario Lilia demetit.”9 Consequently, in this poetic yet logical way, he incorporated the griffin – the coat of arms of the Chodkevičius family – into the image of the patio of the Pacas family.

Stemmat in epithalamium Campus Martis et Palladis in quo […] sponso […] Ioanni Casimiro Chodkiewicz […] ista […] sponsae […] Sophiae Paciae […] florilegium. Photog. in: LIŠKEVIČIENĖ. XVI-XVIII…, p. 205.

The epithalamium is accompanied by a copperplate composition by Conrad Götke, a renowned engraver from Vilnius (Figure 1), which, although modest, fits the convention of heraldic graphics accompanying literary works that add splendor to wedding ceremonies.10 It showed two griffins holding a laurel wreath, inside which are the coats of arms of the Chodkevičius and Pacas families joined with acanthus leaves, i.e., a wedding knot. Above there is a ribbon with an epigram:

“Tela, tubae, soleae cum casto lilia flore

Asciaqu[e] aequali foedere iuncta vigent

Unde queunt duro sociari lilia martis et

Stemmata nempe suos concomitantur heros.”

Below, also on the ribbon: “Anno ad exemplum 1636.”

This verbal and visual composition thus had the form of a stemma, a genre combining literature with the plastic arts, and which now no longer exists but used to be vitally important in the early modern era in terms of social communication.11 In this case the stemma, thanks to its tripartite compositions, resembles an emblem, and its content emphasises the significance of the marital union of two great families with noted ancestry. The family relationships indicated in the text of a stemma and its accompanying graphic illustration not only bring more splendor to the young couple but also determine their bright future.

The combined coat of arms of Sofija Pacaitė shows Gozdawa and Trimitai (pl. Trąby – Rudomina variety) as well as Lapinas (pl. Lis) and Bogorija, surmounted with two helmets with crowns and mantling in the form of an acanthus flagellum, with the crest corresponding to the Leliwa and Trimitai (Rudomina variety). It was thus emphasized that the bride’s grandmothers originated from the most prominent Lithuanian families, the Sapiega and Valavičius.12 The symbols presented, especially those of Gozdawa and Lapinas, were interpreted as symbols of virtues, such as bravery and loyalty to the Catholic religion.13 Together with the laurel and acanthus, they suggested victory and life,14 and thus success and fertility for the married couple. It constituted a permanent element of the epithalamia, which is confirmed by the verses by Claudian at the occasion of Emperor Honorius IV’s wedding:

“tam iunctis manibus nectite vincula,

quam frondens hedera stringitur aesculus,

quam lento premitur palmite populus.”15

In line with previous practice in the milieu of Steponas Pacas, the crest was taken from the Leliwa coat of arms, which presented its very remote yet extremely attractive affinity with the Manvidas.16 The Pacas family were related to them through Aleksandra Alšėniškė (d. 1551/54), whose maternal grandmother was Jadvyga Manvidaitė.17 This ancestry, although very remote, was vitally important for the Pacas family in terms of their family history based on ancient origins, as it strengthened the idea of their Roman beginnings. It also included the Gozdawa, Lapinas, and Bogorija coats of arms, interpreted through ancient tradition.18

Dominik Paca’s coat of arms by the document of Union of Lublin, 1569. Photog. Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych

Interestingly, the coat of arms of the Manvidas family was used by Dominykas Pacas, who used the combined coat of arms displaying Gozdawa (field 1), Trimitai (field 2), Hipocentaur (field 3), and Leliwa (field 4) in the seal attached to the act of the Union of Lublin (Figure 2).19 Dominykas Pacas, by moving the sign of his maternal grandmother Sofija Sudimaintaitė to the second field, united it with the fourth one, where he placed the coat of arms of his maternal great-grandmother of the Manvidas. The coat of arms of Aleksandra Alšėniškė was placed in the third field. The extension of the genealogical program is not accidental, as it displays the kniaz families to which Dominykas Pacas was related through his mother. Although the Leliwa coat of arms of the Manvidas family was placed on the least prestigious fourth place, it is worth highlighting that Dominykas Pacas’s paternal grandmother, whose name remains unknown and who was not born into an influential family, was omitted here. Thus, the layout of the complex coat of arms displays the social advancement of the Pacas family, confirmed by the appropriate marriages. At the same time, it served as a reminder that part of Sofija Sudimantaitė’s legacy was in the hands of Mikalojus Steponas Pacas (d. 1545/46) and his descendants.20 The fact that Mikalojus Steponas (1623–1684), the youngest son of Steponas Pacas, called Povilas Alsėniškis “my great-grandfather, the duke […] bishop of Vilnius” [“naddziad mój ks[ią]żę […] biskup wileński”]21 is evidence that the memory about such remote relatives was still vivid in the seventeenth century.

The emblem of the Chodkevičius family on the print by Conrad Götke (Figure 1) is more developed, as it consists of five fields (Koscieša, Dombrova, Kirvis and Lapinas – pl. Kościesza, Dąbrowa, Topór i Lis) with a inescutcheon depicting the Vytis (pl. Pogoń). It was surmounted with crests appropriate to Koscieša and Dombrova. The incorrect placing of the coat of arms (moving the field with the Vytis from the fifth to the first field) was connected with the need to expose the affinity with the Olelkaitis-Sluckis family, whose heirs the Chodkevičius family aspired to be.22 It should be noted that extending the coat of arms of the Chodkevičius family in terms of the emblem of the Pacai family means highlighting the higher prestige and seniority of the groom’s family, but also Steponas Pacas’s emphasis of the importance of the marriage contracted. This idea is continued in the introduction to the work, which begins with the story of the Chodkevičius family and which evokes his most eminent representatives.23

Obviously, the author of the epithalamium did not forget about the Pacas family, emphasizing that the marriage was held in Lithuania – “Litala dignissime terra splendor et ad magnos iuvenis formate decores.”24 By evoking the specific name of Lithuania as Littala, he recalled that it was “the new name from his homeland of the Italian lands, La Italia” [“nowe imię od swej ojczyzny Włoskiej ziemie, La Italia”] given by Palemon and his companions, “and their descendants when they mixed up the Italian language and customs with the Gepid people, and the mother tongue they remembered, they spoke Litalia, Litualia” [“a potomkowie ich, gdy mowę włoską i obyczaje z ludem grubym Gepidów pomieszali, a ojczystego języka zapamiętali, mówili po tym Litalia, Litualia”].25 This modest, albeit significant allusion naturally and unequivocally re-presented the origins and the status of the Pacas family.

Wedding Print of Teresa Podbereskaitė and Jonas Kristupas Pacas

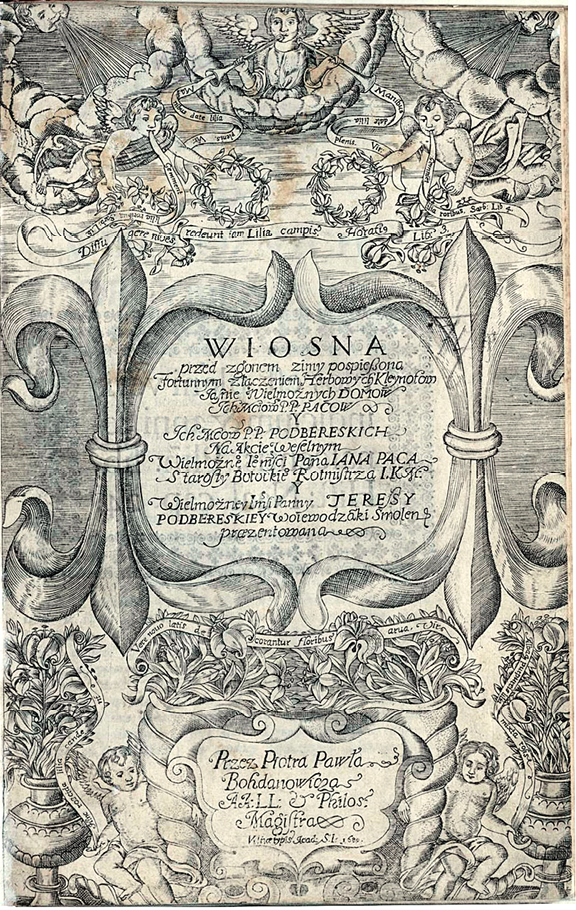

Although literary texts proclaimed during weddings in the Pacas family were published in the following years, they were not accompanied by graphic representations.26 A change only came with the frontispiece (Figure 3) of the epithalamium by Petras Povilas Bohdanovičius (pl. Piotr Paweł Bohdanowicz), a graduate of the Vilnius Academy and the rector of Saint John the Baptist and John the Evangelist Church.27 This lay graced the wedding of the daughter of the governor of Smolensk, Teresa Podbereskaitė (d. 1720), and the Starosta of Batakiai, Jonas Kristupas Pacas (after 1640–1702) from the younger, so-called hetman family line, which was minded by Mykolas Kazimieras Pacas.

Frontispiece of epithalamium Wiosna przed zgonem zimy pośpieszona fortunnym złączeniem herbowych klejnotów [...] domów […] Paców i […] Podbereskich na akcie weselnym […] Pana Jana Paca […] i […] Panny Teresy Podbereskiej wojewodzianki smoleńskiej prezentowana. Vilnae, 1680. Photog. Vilniaus universiteto biblioteka

Both the Podbereskis and the Pacas family used the Gozdawa as their coat of arms. Martynas Symkevičius (pl. Marcin Szymkiewicz), an engraver from Vilnius, then created a cartouche out of two heraldic lilies fused together, and he placed the title of the work there. Below there are lily flowers in symmetrically placed vases and horns of plenty supported by putti. Above the lily cartouche there is a personification of Fame with two trumpets and two putti with flowers and lily wreaths in their hands. Moreover, the top corners of the copperplate show the personifications of winds, which the author calls “gentle Zephyrs” [„łagodnych Zephirów”]28 in the introduction to the epithalamium. There are two streamers coming out of Fame’s trumpets: “Manibus date lilia plenis, Vir[gilius],”29 whereas the putti say “Gemment lilia roribus. Sarb[ievius] Lib. 4.”30 Below is the text “Diffugere nives redeunt iam Lilia campis? Horati[us] Lib. 3.”31 The putti by the horns of plenty hold streamers with the inscriptions “Hinc roscida lilia candent” and “Albaq[us] purpureis lilia mixta rosis.” Below them and the cartouche with the title there is an inscription: “Vere novo laetis decorantur floribus arva, Vir[gilius].”32

The verses by Horace, Virgil, and Motiejus Kazimieras Sarbievijus paraphrased in the frontispiece glorify the vitality of the lily, as well as the end of winter and the flowering of spring.33 It thus alludes to the married couple and their fertility. The words spoken by Fame are directed at Teresa Podbereskaitė and Jonas Kristupas Pacas. Their relationship was based on their beauty, which was somehow prophesied by the Gozdawa coat of arms itself, and which is recalled by the words said by the putti depicted in the top of the composition. It is bonded by love, hence the emphasis on the heraldic lily, the flower which grows beautiful in the spring and shines with dew, as well as the motif of red roses,34 which serve to cement conjugal love, and into which is interwoven a quotation:

“When lifetime long-lasting courtesy

A union of lilies of excellent whiteness

They connect with each other”35

[„Gdy dożywotniej trwałym uprzejmości

Związkiem lilie wybornej białości

Łączą się z sobą”].

Petras Povilas Bohdanovičius drew upon a tried and tested topos of panegyrists who perceived the lily as a flower full of virtues, blossoming in a garden understood symbolically as the family and the homeland. In this case, the allusions are equally to the Podbereskis family, who also used the Gozdawa as their symbol, as

“they are both equal in decoration.

One born in honorable

Garden of the Pacas family, the second begotten in a flourishing patio

of the Podbereskaitis family,

they sow with a pleasant smell”36

[“są obie równe w ozdobie.

Jedna w przezacnym Pacowskim zrodzona

Dziardynie, druga w kwitnącym spłodzona

Cnych Podbereskich Wirydarzu, wonią

Przyjemną ronią.”].

Thus the epithalamia were equally divided into two families. “Whiteness of hereditary lily” [“Białość Dziedzicznej Liliej”], and then its “vigor” [“czerstwość”] and “scent” [“wonność”] were described.

* * *

The heraldic programmes discussed and added to two epithalamia of the Pacas family are part of the Baroque customs of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in which ostentation and staging went in hand with political and family propaganda. An important part of this was the symbolic reading of coats of arms, primarily in a moralizing spirit, together with preparing the heraldic constructions that would evoke the past period and family connections. Both discussed prints accompanied wedding receptions, and may also be construed as prognostics for a happy married life.

Sources

1. Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych, sygn. 5627.

2. Archiwum Krakowskiej Prowincji Zakonu Karmelitów Bosych, sygn. AKBW 13.

3. Lietuvos dailės muziejus, sygn. B-5 Ap-1 b-15.

References

1. BOHDANOWICZ, Piotr Paweł. Wiosna przed zgonem zimy pośpieszona fortunnym złączeniem herbowych klejnotów [...] domów […] Paców i […] Podbereskich na akcie weselnym […] Pana Jana Paca […] i […] Panny Teresy Podbereskiej wojewodzianki smoleńskiej prezentowana. Vilnae, 1680.

2. BURNIEWICZ, Kazimierz Szymon. Łabędź […] Panny […] Konstanciey Zawiszanki […] przy weselnym akcie kwitnącey wiosny […] Feliksa Paca…, Wilno, 1651.

3. BURNIEWICZ, Kazimierz Szymon. Vernuptiale inter […] Felicem Pac […] et […] Constantiam Zawiszanka…, Vilnae, 1651.

4. KOJAŁOWICZ WIJUK, Wojciech. Herbarz rycerstwa W. X. Litewskiego…, ed. PIEKOSIŃSKI Franciszek. Kraków, 1897.

5. KRASOWSKI, Bartłomiej. Życzliwa usługa na przezacny akt wesela […] Jana Kazimierza Paca […] i […] Heleny Steckiewiczówny…, [Wilno, 1621].

6. LITUANUS, Michalon. De moribus Tartarorum, Lituanorum et Moschorum…, Basileae, 1615.

7. MAFFON, Aleksander. Hymen wesoły […] na wesele przezacnych osób […] P. Kryspina […] i […] Anny Pacówny..., Wilno, 1622.

8. NIESIECKI, Kacper. Herbarz Polski, ed. Bobrowicz Jan Nepomucen. Lipsk, 1839, vol. 4.

9. OKOLSKI, Szymon. Orbis Poloni…, Kraków, 1641, 1643, 1645, vol. 1–3.

10. PAPROCKI, Bartosz. Gniazdo cnoty, skąd herby rycerstwa sławnego […] początek swój mają. Kraków, 1578.

11. RADZIWIŁŁ, Albrycht Stanisław. Pamiętnik o dziejach w Polsce. transl. and ed. by PRZYBOŚ, Adam, ŻELEWSKI, Roman. Warszawa, 1980, vol. 1.

12. RUDOWICZ, Kacper. Funesta liliorum messis praepropero letho succisorum […] D. Samuelis Pac…, Vilnae, [1627].

13. SŁUSZKA, Bogusław, Campus Martis et Palladis in quo […] sponso […] Ioanni Casimiro Chodkiewicz […] ista […] sponsae […] Sophiae Paciae […] florilegium…, Vilnae, 1636.

14. STRYJKOWSKI, Maciej. Kronika polska, litewska, żmudzka i wszystkiej Rusi…, ed. MALINOWSKI, Mikołaj. Warszawa, 1846, vol. 1.

1. BOBIATYŃSKI, Konrad. Michał Kazimierz Pac – wojewoda wileński, hetman wielki litewski. Działalność polityczno-wojskowa. Warszawa, 2008.

2. CZARSKI, Bartłomiej. Stemmaty w staropolskich książkach, czyli rzecz o poezji heraldycznej. Warszawa, 2012.

3. CZYŻ, Anna Sylwia. Fundacje artystyczne rodziny Paców: Stefana, Krzysztofa Zygmunta i Mikołaja Stefana Paców. „Lilium bonae spei ab antiquitate consecratum”. Warszawa, 2016.

4. CZYŻ, Anna Sylwia. Kościół świętych Piotra i Pawła na Antokolu w Wilnie. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków, 2008.

5. CZYŻ, Anna Sylwia. Przekaz symboliczny i propagandowy programów heraldycznych w siedemnastowiecznych żałobnych drukach Pacowskich, czyli „Liliaci” i ich Gozdawa. Przegląd Wschodni, 2018, vol. 14, Nr. 4(56), p. 739–765.

6. KAŁAMAJSKA-SAEED, Maria. Wilno jako ośrodek graficzny w XVII w. Postulaty badawcze. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki, 1993, Nr. 2/3, p. 199–211.

7. KOBIELUS, Stanisław. Florarium christianum. Symbolika roślin – chrześcijańska starożytność i średniowiecze. Warszawa, 2006.

8. LIŠKEVIČIENĖ, Jolita. Mundus emblematum: XVII a. Vilniaus spaudinių iliustracijos, Vilnius, 2005.

9. LIŠKEVIČIENĖ, Jolita. XVI-XVIII amžiaus knygų grafika: herbai senuosiuose Lietuvos spaudiniuose. Vilnius, 1998.

10. MROCZEK, Katarzyna. Epitalamium staropolskie. Między tradycją literacką a obrzędem weselnym. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk-Łódź, 1989.

11. PATIEJŪNIENĖ, Eglė. Brevitas Ornata. Mažosios literatūros formos XVI–XVII amžiaus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės spaudiniuose. Vilnius, 1998.

12. Polski słownik biograficzny, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk, 1979, vol. 24.

13. STANKIEWICZ, Aleksander. Tradycje militarne Chodkiewiczów w świetle grafiki oraz stemmat w drukach ulotnych z pierwszej połowy XVII w. In Studia nas staropolską sztuką wojenną. ed. HUNDERT, Zbigniew, ŻOJDŹ, Karol, SOWA, Jan Jerzy. Oświęcim, 2014, vol. 3, p. 61–93.

14. Szesnastowieczne epitalamia łacińskie w Polsce, transl. BROŻEK, Mieczysław, ed. NIEDŹWIEDŹ, Jakub. Kraków, 1999.

15. TALBIERSKA, Jolanta. Grafika XVII wieku w Polsce. Funkcje, ośrodki, artyści, dzieła. Warszawa, 2011.

16. WOLFF, Józef. Pacowie. Materyjały historyczno-genealogiczne. Petersburg, 1885

17. WRÓBEL, Wiesław. Krąg rodzinny Zofii z Chożowa Holszańskiej i jej testament z 29 lipca 1518 r. In: Rody, rodziny Mazowsza i Podlasia. Źródło do badań genealogicznych. ed. REMBISZEWSKA, Dorota Krystyna, KRAJEWSKA, Hanna. Łomża, 2013, p. 345–366.

1 Primary sources regarding the Pacas family include: WOLFF, Józef. Pacowie. Materyjały historyczno-genealogiczne. Petersburg, 1885; Polski słownik biograficzny, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk, 1979, vol. 24, s. 691-749; BOBIATYŃSKI, Konrad. Michał Kazimierz Pac – wojewoda wileński, hetman wielki litewski. Działalność polityczno-wojskowa. Warszawa, 2008.

2 For more on this topic, see CZYŻ, Anna Sylwia. Fundacje artystyczne rodziny Paców: Stefana, Krzysztofa Zygmunta i Mikołaja Stefana Paców. „Lilium bonae spei ab antiquitate consecratum”. Warszawa, 2016, p. 73-154; CZYŻ, Anna Sylwia. Przekaz symboliczny i propagandowy programów heraldycznych w siedemnastowiecznych żałobnych drukach Pacowskich, czyli „Liliaci” i ich Gozdawa. Przegląd Wschodni, 2018, vol. 14, Nr. 4(56), p. 740-747.

3 This arose from Lithuanian ethnogenesis, and was extremely prestigious as it built up the Pacai family’s elitism and thus aligned it with the foremost Lithuanian families, such as the Alsėniškis, Sapiega and Radvila, who were also in search of their ancestors among the fugitives from Rome led by Palemon. The Pacas family legend was most probably devised in the 1570s-1580s, in the generation of Steponas Pacas’ grandfather Dominykas (d. 1579), among his brothers Mikalojus (c. 1527–1585), Kiev’s nominee; Stanislovas (d. 1588), governor of the province of Vitebsk; and Povilas (d. 1595), governor of the province of Mstsislaw, to whom Maciej Stryjkowski dedicated fragments of Kronika polska, litewska, żmudzka i wszystkiej Rusi (Books VII and IX). They were educated people connected with the Academy of Cracow and the Vilnius Academy, and who may be referred to as humanists. At the same time, Mikalojus was seen as extraordinarily educated and Stanislovas as one of the most prominent members of the Lithuanian council. Their public activity came during a period of heated discussion on the provenance of the Lithuanian nation from the ancient Romans. It was led by scholars educated at the Academy of Cracow as well as at Western universities, just like the Pacas family members connected with the court of Žygimantas Augustas. Czyż, Fundacje..., p. 57–66.

4 RADZIWIŁŁ, Albrycht Stanisław. Pamiętnik o dziejach w Polsce. transl. and ed. by PRZYBOŚ, Adam, ŻELEWSKI, Roman. Warszawa, 1980, vol. 1, p. 558.

5 The epithalamium, in line with its antique counterpart, was a poetic, lyrical, or epic work, but during the early-modern era, particular countries devised their own forms of this now non-existent genre. They were sometimes hybrid in nature, as on occasion they were given the prose form. Epithalamia, in line with wedding speeches, were sometimes printed and adorned with graphic images of coats-of-arms or allegorical compositions. They were distributed to guests during the ceremony, which demonstrated not only the family’s cultural experience but also their wealth. MROCZEK, Katarzyna. Epitalamium staropolskie. Między tradycją literacką a obrzędem weselnym. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk-Łódź, 1989, p. 7-46, 59-63; Szesnastowieczne epitalamia łacińskie w Polsce, transl. BROŻEK, Mieczysław, ed. NIEDŹWIEDŹ, Jakub. Kraków, 1999, p. 12–22.

6 The work was dedicated to the young couple and their fathers, Kristupas Chodkevičius and Steponas Pacas.

7 This was the funeral speech devoted to Samuelis Pacas (1590–1627), the vice-chancellor’s brother. RUDOWICZ, Kacper. Funesta liliorum messis praepropero letho succisorum […] D. Samuelis Pac…, Vilnae, [1627]. CZYŻ. Przekaz…, p. 741-744.

8 CZYŻ, Anna Sylwia. Kościół świętych Piotra i Pawła na Antokolu w Wilnie. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków, 2008, p. 189-195; CZYŻ. Fundacje…, p. 67-68, 194-205, 369-370.

9 SŁUSZKA, Bogusław, Campus Martis et Palladis in quo […] sponso […] Ioanni Casimiro Chodkiewicz […] ista […] sponsae […] Sophiae Paciae […] florilegium…, Vilnae, 1636, p. 7. For more on the print in the light of the propaganda content exclusively related to the Chodkevičiai family: STANKIEWICZ, Aleksander. Tradycje militarne Chodkiewiczów w świetle grafiki oraz stemmat w drukach ulotnych z pierwszej połowy XVII w. in Studia nas staropolską sztuką wojenną. ed. HUNDERT, Zbigniew, ŻOJDŹ, Karol, SOWA, Jan Jerzy. Oświęcim, 2014, vol. 3, pp. 82-84. First reflections on the epithalamium in question against the Pacas family: CZYŻ. Fundacje…, p. 82-85.

10 The specimen with the engraving is in a block in Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka [The Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Art] (ref. L-17/2-3/1-21), as well as in Biblioteka Zakładu Narodowego im. Ossolińskich [the Ossolinski National Library] (ref. XVII-15762-IV) and in Biblioteka Jagiellońska [the Jagiellonian Library] (ref. 14087/III). The print is recorded without any formal or ideological analysis in: LIŠKEVIČIENĖ, Jolita. XVI-XVIII amžiaus knygų grafika: herbai senuosiuose Lietuvos spaudiniuose. Vilnius, 1998, p. 205; LIŠKEVIČIENĖ, Jolita. Mundus emblematum: XVII a. Vilniaus spaudinių iliustracijos, Vilnius, 2005, p. 191-192; TALBIERSKA, Jolanta. Grafika XVII wieku w Polsce. Funkcje, ośrodki, artyści, dzieła. Warszawa, 2011, p. 333-334.

11 Though a stemma could function on its own (a poem written on a coat of arms), most frequently it was a verbal and visual composition consisting of a coat of arms (icons) and a rhymed literary work. On occasion, a stemma was composed of three elements, and the use of a lemma (motto) made it close to an emblem. As an element of the so-called publishing frame, the stemma played the role of a paratext, i.e., a structure embracing the actual text. Stemmata were prepared not only for noble coats of arms, but also instead of emblems of cities or monasteries. Extensively on the subject: CZARSKI, Bartłomiej. Stemmaty w staropolskich książkach, czyli rzecz o poezji heraldycznej. Warszawa, 2012.

12 Sofija Agata Sapiegaitė (d. c. 1630), mother of Steponas Pacas, was the daughter of the governor of Minsk; his daughter took her name after her. In turn, Ana Rudomina-Dusiackaitė’s mother, Feliciana Valavičienė, was the daughter of Ivan, Marshal of Lithuania and sister to Eustachijus, Bishop of Vilnius from 1616.

13 OKOLSKI, Szymon. Orbis Poloni…, Kraków, 1641, vol. 1, p. 52, 55-56; Kraków 1643, vol. 2, p. 50, 56-57, 138-140; Kraków 1645, vol. 3, p. 225.

14 KOBIELUS, Stanisław. Florarium christianum. Symbolika roślin – chrześcijańska starożytność i średniowiecze. Warszawa, 2006, p. 24, 123-124, 211-212.

15 Wedding poetry by Claudian was very popular and often served as a model for Polish-Lithuanian authors. Szesnastowieczne…, p. 17-18, 22, 26-29, 31.

16 PAPROCKI, Bartosz. Gniazdo cnoty, skąd herby rycerstwa sławnego […] początek swój mają. Kraków, 1578, p. 1160-1166; OKOLSKI. Orbis Poloni…, Kraków 1643, vol. 2, p. 88-89; KOJAŁOWICZ WIJUK, Wojciech. Herbarz rycerstwa W. X. Litewskiego…, ed. PIEKOSIŃSKI Franciszek. Kraków, 1897, p. 132. This kind of crest next to Gozdawa appeared on seals and prints connected with Steponas Pacas, the epitaph of Samuelis Pacas in the cathedral in Vilnius (1627–1630) founded by the vice-chancellor, as well as on his son Kristupas Zigmantas’s seals. Kasper Niesiecki referred to the Gozdawa with a crescent and a star in a crest identified exclusively with the Pacas family as a heraldic variety (NIESIECKI, Kacper. Herbarz Polski, ed. Bobrowicz Jan Nepomucen. Lipsk, 1839, vol. 4, p. 253). It is worth mentioning that such a crest appeared also on the seals of Vincentas Aleksandras Gosievskis, son of Ieva Pacaitė (d. after 1647), sister of the vice-chancellor. Archiwum Krakowskiej Prowincji Zakonu Karmelitów Bosych [Archives of the Cracow Province of the Order of Discalced Carmelites], ref. AKBW 13 (Document from 16th September 1654, Vilnius), p. 99.

17 Jadvyga, daughter of Jonas Manvidas, was the first wife of Alekna Sudimantaitis. The couple had three daughters: Sofija, who married Aleksandras Alsėniškis before 1473, Jadvyga, and Anna. The Leliwa coat-of-arm denoting the Manvidas family was also used in the heraldry of Bishop Povilas Alsėniškis (for example on his grave in the cathedral in Vilnius), Aleksandra’s brother. WRÓBEL, Wiesław. Krąg rodzinny Zofii z Chożowa Holszańskiej i jej testament z 29 lipca 1518 r. in Rody, rodziny Mazowsza i Podlasia. Źródło do badań genealogicznych. ed. REMBISZEWSKA, Dorota Krystyna, KRAJEWSKA, Hanna. Łomża, 2013, p. 349-351, 353-355.

18 E.g. in Orbis polonus Szymon Okolski compared the Lapinas coat of arms with the arrows of Hercules, Xerxes, and Artaxerxes, but also to the arrow that terminally wounded Achilles. OKOLSKI. Orbis Polonus, vol. 1, p. 53; vol. 2, p. 49-50, 139-140.

19 Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych [The Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw], ref. 5627.

20 WRÓBEL, p. 361.

21 Lietuvos dailės muziejus [Lithuanian Art Museum], ref. B-5 Ap-1 b-15 (Mikalojus Steponas Pacas’ testament, 4th March 1682, Vilnius), p. 6v

22 STANKIEWICZ, p. 83-84.

23 SŁUSZKA, p. 2-6.

24 SŁUSZKA, p. 11.

25 STRYJKOWSKI, Maciej. Kronika polska, litewska, żmudzka i wszystkiej Rusi…, ed. MALINOWSKI, Mikołaj. Warszawa, 1846, vol. 1, p. 81. Michalon Lituanus added: “quibus exacti sunt a parentibus nostris Italis, qui postea Litali, deinde Lituani appellati sunt.” De moribus Tartarorum, Lituanorum et Moschorum…, Basileae, 1615, p. 24.

26 E.g. BURNIEWICZ, Kazimierz Szymon. Łabędź […] Panny […] Konstanciey Zawiszanki […] przy weselnym akcie kwitnącey wiosny […] Feliksa Paca…, Vilnius, 1651; BURNIEWICZ, Kazimierz Szymon. Vernuptiale inter […] Felicem Pac […] et […] Constantiam Zawiszanka…,Vilnius, 1651.

27 BOHDANOWICZ, Piotr Paweł. Wiosna przed zgonem zimy pośpieszona fortunnym złączeniem herbowych klejnotów [...] domów […] Paców i […] Podbereskich na akcie weselnym […] Pana Jana Paca […] i […] Panny Teresy Podbereskiej wojewodzianki smoleńskiej prezentowana. Vilnius, 1680. The print in question, together with a graphic frontispiece, are located in Lietuvos mokslų akademijos Vrublevskių biblioteka (ref. L-17/2-19, slightly trimmed at the bottom and top) and Vilniaus universiteto biblioteka [Vilnius University Library] (ref. III 14490). It was recorded without any formal or ideological analysis. KAŁAMAJSKA-SAEED, Maria. Wilno jako ośrodek graficzny w XVII w. Postulaty badawcze. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki, 1993, Nr. 2/3, p. 210; LIŠKEVIČIENĖ. XVI-XVIII…, p. 60, 62; PATIEJŪNIENĖ, Eglė. Brevitas Ornata. Māžosios literatūros formos XVI-XVII amžiaus Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės spaudiniuose. Vilnius, 1998, p. 246, 248; TALBIERSKA, p. 95, 359.

28 BOHDANOWICZ, k. 1.

29 This paraphrases Book VI of the Aeneid by Virgil. The whole section is worded: “Manibus date lilia plenis, purpureos spargam flores animamque nepotism his saltem accumulem donis et fungar inani munere.”

30 These words are taken from Lyricorum libri IV by Motiejus Kazimieras Sarbievijus, published in 1632 in Antwerp: “Jesu, dulce tuis ora natant sonis, / Infuso veluti pocula Caecubo, / Aut humecta caducis / Gemment lilia roribus.”

31 This is a paraphrase of an ode by Horace. The fragment is worded: “Diffugere nives: redeunt iam gramina campis.”

32 A quotation from Virgil.

33 Meanwhile, a passage from Historia naturalna by Pliny the Elder became the motto of the epithalamium: [Arborum] “flos est pleni veris indicium et anni renascentis” [flos gaudium arborum].

34 KOBIELUS, p. 122-123, 185.

35 BOHDANOWICZ, p. 2v.

36 BOHDANOWICZ, p. 2v-3.