Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2019, vol. 73, pp. 203–229 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2019.73.38

Diffusion of the Discourse on the Love of Reading in Europe from the 18th to the 20th Centuries

Ilkka Mäkinen

Information Studies and Interactive Media,

Faculty of Communication Sciences

FI-33014 University of Tampere, Finland

E-mail: ilkkajmakinen@gmail.com

Summary. When reading in the 18th century became an activity common among an ever growing part of the European population and thereby a socially more visible cultural phenomenon, a need arose to create concepts and linguistic terms to refer to the new types of reading behavior. The new masses of readers did not seemingly have a rational goal for their reading, they just read for the sake of reading itself. Therefore, an explanation for their behavior was that they had a love of reading. To speak about people’s love of reading became a recurrent feature of the discourse on reading, a sub-discourse of its own, the discourse on the love of reading. The birthplace of the discourse may have been in 17th century France, wherefrom it was mediated into other countries and language areas. Even the contemporaries believed that the reading mania was contagious, and expected, feared, or hoped that something similar would happen in their own country. This caused debate and the use, even invention, of words and phrases that belong to the discourse on love of reading. Even the words and phrases used for speaking about reading migrated over linguistic, political, and social borders. The initiation, growth, and diffusion of the discourse can be followed by searching the typical words and phrases that indicate the presence of the discourse. Data were obtained from Google Books Ngram Viewer and national full-text databases of books and newspapers. A map representing the geographical diffusion of the discourse in Europe until the 20th century is constructed. The historical conditions for the diffusion of the discourse are discussed. Methodological problems are discussed and future research is outlined.

Keywords: history of reading, love of reading, discourse on reading, motivation for reading, cultural history, Europe.

Meilės skaitymui diskurso sklaida Europoje nuo XVIII a. iki XX a.

Santrauka. Kai XVIII a. skaitymas tapo vis įprastesniu užsiėmimu tarp vis didėjančios daugumos europiečių, kartu virsdamas ir vis labiau socialiai akivaizdesniu kultūriniu fenomenu, atsirado poreikis kurti konceptus ir lingvistinius terminus, skirtus naujoms skaitymo rūšims apibūdinti. Naujosios skaitančiųjų masės, atrodo, užuot turėjusios racionalų skaitymo tikslą, skaitė dėl paties skaitymo. Todėl imta aiškinti, kad jų elgesio priežastis yra meilė skaitymui. Kalbėjimas apie žmonių meilę skaitymui tapo pasikartojančia skaitymo diskurso ypatybe, savaime tam tikru subdiskursu, diskursu apie meilę skaitymui. Šio diskurso atsiradimo vieta galėjo būti XVII a. Prancūzija, iš kurios tai pasklido į kitas šalis ir kalbų teritorijas. Diskurso amžininkai manė, kad skaitymo manija yra užkrečiama, ir tikėjosi, baiminosi ar vylėsi, kad kažkas panašaus gali atsirasti ir jų šalyse. Tai sukėlė diskusijas ir paskatino kūrimą bei vartoseną žodžių ir frazių, priskirtinų skaitymo meilės diskursui; net šie žodžiai ar frazės, skirti kalbėti apie skaitymą, kirto lingvistines, politines ir socialines sienas. Diskurso atsiradimą, plėtimąsi ir sklaidą galima sekti ieškant tipinių žodžių bei frazių, kurie patvirtintų diskurso egzistavimą. Šio tyrimo duomenys buvo gauti naudojantis Google Books Ngram Viewer įrankiu ir ieškant knygų bei dienraščių nacionalinėse tekstų duomenų bazėse. Taip pat buvo sukurtas žemėlapis, rodantis geografinę šio diskurso sklaidą Europoje iki XX a. Aptartos istorinės diskurso sklaidos aplinkybės, metodologinės problemos, apibrėžti ateities tyrimų tikslai.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: skaitymo istorija, meilė skaitymui, skaitymo diskursas, skaitymo motyvacija, kultūros istorija, Europa.

Received: 2/9/2019. Accepted: 18/10/2019

Copyright © 2019 Ilkka Mäkinen. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

When reading became an activity common among an ever growing part of the European population and thereby a socially more visible cultural phenomenon beginning with the 18th century, a need arose to create concepts and linguistic terms to refer to the new types of reading behavior. Some presuppositions had to be shared among those who were speaking about reading. One of the puzzles that needed a common understanding was, why all these people, even those who never before had read regularly, had started to read on a daily basis. What was the motivation for reading, when very few of the new readers had any functional necessity to read so much? It was natural that learned men, scholars and priests, read quite a lot: it belonged to their profession. Educated people in general read regularly, because they had much free time and needed to know things for their civilized conversations. But what about the rest – servants, maids, drivers, even peasants? There really was no concrete need for them to read so much as they seemed to begin to do in the late 18th century. And in many places, the outbreak of a general reading mania seemed like a contagious disease, caused by a “reading bug,” as it was called in Northern Germany.1 It would have been natural to presuppose that people start to read and keep on reading because they get practical benefits from reading, but this did not seem to be a sufficient explanation for the dramatic rise in the number of readers. There seemed to be something unexplainable, something mystical in people’s reading behavior.

One of the answers to this mystery was to say that they had a love of reading, or Leselust or goût de la lecture, a general, spontaneous, innate urge to read. It was believed to exist without a specific rational goal. For us it may seem a circular explanation that people read because they want to read, but for the (educated) people of the 18th century it was a novelty to assume that all people had a latent desire to read, a hidden, basically psychological, intrinsic reading motivation that only waited for its triggering in propitious circumstances.

Is love of reading an inherent part of the human psyche needs not bother us here (although we nowadays may falter in our belief that it is so), because we, in this article, are interested in the phenomenon as a figure of speech, part of a discourse on reading. The ways to speak about love of reading, the irrational motivation for reading, constitute a special part of the general discourse on reading. Therefore, it can be called the discourse on the love of reading, a historical phenomenon that has a beginning, a “life” and perhaps an end as well.

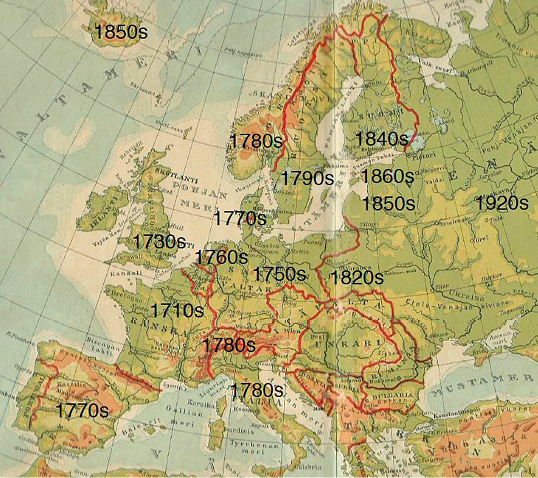

I have in a number of previous articles analyzed the birth, expansion, and present status of the discourse on the love of reading.2 The goal of this article3 is to draw a preliminary map on how the discourse on the love of reading was diffused in Europe until the 20th century.

Since we are interested in the love of reading as a discursive phenomenon, which means a basically linguistic thing, we have to study what has been said about reading. As we cannot ask the people of the past about what they thought about reading, we have to read what they have written about reading. We may assume that the more something has been talked about, the more it has been written about, and the more some pertinent words and phrases appear in the printed text.

In the frame of this article, the goal to draw a map on the diffusion of the discourse on the love of reading is both simple and extremely complicated. The end result is a simple map with years marked on it. The complexity is, of course, caused by the great number of languages that I would wish to include in my presentation. A satisfactory study would demand a team of scholars with knowledge of many different languages. This has not been possible at this stage of the project, so I have had to use the knowledge I have of several languages. For more foreign languages, I have used Google Translator, Wiktionary, and other tools. I am aware that this approach easily leads to errors and superficiality, but one has to start from somewhere.

On the basis of my earlier research, I have come to the conclusion that the discourse on love of reading was born or initiated in France in the 17th century, and that it first moved to England and Germany (or the language communities in these regions). After that it spread into other language areas or countries. Already the contemporaries believed that love of reading – or its more negative forms – is contagious and that the reading mania can transgress linguistic, national, and social borders. This diffusion was something that the contemporaries learned to start waiting. When might this epidemic or blessing reach us? The diffusion happened also socially, but in this article I am concentrating on the geographical diffusion.

After thorough investigations on the appearance of the discourse in Finland, France, England and Germany (or Finnish, Swedish [spoken in Finland], French, English and German texts), I think it is safe to assume that the existence of the discourse is indicated by the appearance of certain typical words or phrases that refer to the concept of love of reading or, more theoretically, to an intrinsic motivation for reading. Thus, when such words and phrases start to appear in greater number in the texts in any language at a certain point of time, this is a sufficient indication that the discourse has entered into the linguistic universe of this textual community or this country or language area. In many cases, this is hypothetical only. Further studies, perhaps by those who really know the languages and cultures that I am writing about, may corroborate or overthrow my hypotheses.

The discourse on love of reading is closely attached to the concept of modernity. My intention is not to delve deeper into the question what modernity is, but certainly some features that are attached to it are the enlightenment, popular education, industrialization, freedom of speech, individualism, religious tolerance, etc. Freedom to read as much whatever one wishes for whatever reason is certainly part of the features of modernity, although the attitudes toward free reading have not always been too liberal even in the most advanced countries. But I would like to stress that the discourse on love of reading does not necessarily indicate much about the intrinsic qualities, intellectual level, moral character, human worth, etc. of a community. The discourse is, at its bottom, a figure of speech, a certain way to speak about something. A country, nation or linguistic community may have had long cultural traditions, a literature of its own since ancient times, wealth, vigor, etc. for centuries without the discourse on love of reading. The discourse on love of reading does not, as such, indicate anything good or bad, although it is probable that it is connected to some valuable features of modernity. It depends on us, whether we believe that the features attached to modernity are good.

The goal of this article is to visualize the diffusion of the European discourse on the love of reading. That means a Pan-European perspective, not in the first place a detailed study of the singular language areas or countries. There are many theoretical and methodological problems attached to my approach, but for the sake of economy, I first and foremost present the results with as little details as possible. For some countries, I have been able to produce a tentative historical background, which is important for the understanding of the diffusion of the discourse, but in many cases this is still insufficient. This article is a progress report towards a more voluminous study.

Google Books Ngram Viewer as a Tool

Since my goal is a general view on the historical discourse and comparison of as many as possible languages, language areas, and countries, I have had great help from Google Books Ngram Viewer (from here on: GBNgV), even if I am aware of the shortcomings – unsystematic material, doubles, errors in optical reading, etc. – of GBNgV from a strictly linguistic viewpoint. From the point of view of my goals, these shortcomings are balanced by the ease of use and availability of many languages, which, as far as I know, no other service provides.4

I have used in the first place only the most basic tools of the service. The service has been ameliorated during the years of its existence, and new tools have been added. The number of digitized books grows all the time, which means that the results of queries may change. I still believe – and hope – that the trends at large do not change much.

The set of languages available in Google Books Ngram Viewer includes English (general English, British and American English), French, German, Spanish, Russian, Italian, Chinese (simplified), and Hebrew. I have tried to include most of these languages into my study, but the problems accumulate the more the farther I glide outside my linguistic capabilities. Fortunately, modern tools available in the Web, such as Google Translator and Wiktionary, offer help. Reading websites dealing with the questions of reading and reading campaigns also has been useful for finding suitable words and phrases. I did not include Hebrew into my study because of the lack of knowledge of the language. Chinese was left out, since I am concentrating on Europe. A number of European languages have since centuries been spoken outside of Europe. It would have been interesting to include Australia, New Zealand, Quebec, South Africa, countries of Latin America, etc. in this study, but it would have made the presentation too complicated at this point of the project.

In this study, the most important goal is to find the year or period of time, when we can assume that the discourse on love of reading has entered the language area or country. I have tried to find the most unambiguous words or phrases that indicate the existence of the discourse; then, I have put these words or phrases in a string and seen what the result is when they are put into the search window of GBNgV.

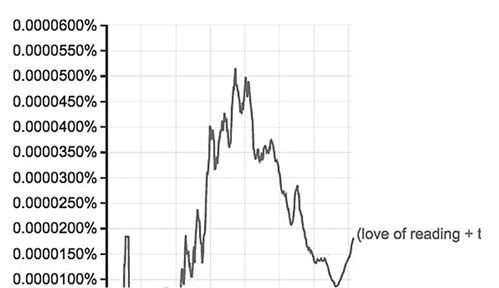

Graph 1. Phrases indicating the existence of the discourse on love of reading in the English language literature 1650–2000 according to Google Books Ngram Viewer. Moving average 3.5 Done May 14, 2019.

In the case of the English language (including both British and American English) the string of phrases used was: “love of reading+taste for reading+passion for reading+love for reading+appetite for reading+fondness for reading+relish for reading+zeal for reading+desire of reading” (Graph 1). I have left out many potential phrases because they are not really unambiguous indicators of the discourse, such as desire to read, pleasure of reading, habit of reading, etc. These phrases often are used in other contexts that have nothing to do with the discourse I am interested in. Furthermore, the search window of GBNgV allows only a limited number of characters, which means that in any case something must be left out.

The graph that is produced visualizes the centuries long trend of the discourse with a steep rise till the mid-19th century, an as steep a decrease till the end of the 20th century, and a dramatic new rise around the last millennium. I have analyzed the shape of the graph in another article (Mäkinen 2018), but here our concern is to pinpoint the start of the English discourse on love of reading. It seems that, as an enduring phenomenon, it is situated around the year 1750, perhaps a decade or two earlier, but certainly in the mid-18th century.

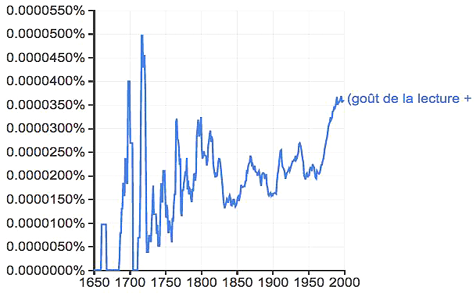

For the French language I compiled the following string of phrases: “goût de la lecture+goût de lecture+goût pour la lecture+plaisir de la lecture+passion pour la lecture+plaisir à la lecture+intérêt à la lecture+amour pour la lecture” (Graph 2).

Graph 2. Phrases indicating the existence of the discourse on love of reading in the French language literature 1650–2000 according to Google Books Ngram Viewer. Moving average 3. Done May 14, 2019

When the string of potential French phrases is put into the search window, the product is a graph that differs astonishingly from the English graph, but what interests us here the most is the fact that the French discourse seems to have begun some decades earlier that the English one. An enduring rise of the frequencies seems to start around 1710. I have argued previously (Mäkinen 2014) that the elements of the discourse were formed in France as a result of the religious campaigns between the Catholics and Protestants in the 17th century, and moved during the late 17th and beginning of the 18th into the worldly domain. Many of the common words and phrases that have been used in the European languages can be seen as translations from the original French vocabulary on reading. Thus, e.g., it is probable that amour de la lecture became love of/for reading, goût de la lecture became taste for reading, Geschmack am Lesen (later Lesegeschmack), maybe also Leselust, etc.

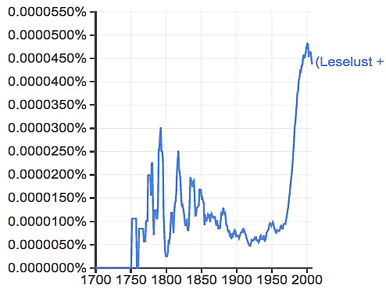

In the German language, I have used the following string of words and phrases: “Leselust + Lust am Lesen + Interesse am Lesen + Vergnügen am Lesen + Lust zum Lesen + Lust zu lesen + Lesebegierde + Neigung zum Lesen + Geschmack am Lesen + Lesegeschmack + Lesevergnügen” (Graph 3). The string includes both compound words and phrases. I have left out such negative phrases as Lesewut and Lesesucht, which have been popular in the German discourse on reading, because I want to concentrate on the positive sides of the discourse (and this applies to other languages as well).

Graph 3. Words and phrases indicating the existence of the discourse on love of reading in the German language literature 1650–2000 according to Google Books Ngram Viewer. Moving average 3. Done May 14, 2019.

The shape of the graph that is produced is somewhere between the French and the English ones. What is extraordinary are the decades around the last millennium, where a shocking rise exceeds everything that was before. In the case of the discourse on reading, Germany is the thermometer of the Western world! Most important from the point of view of the present article, though, is the fact that the start of the German discourse on love of reading is positioned at mid-18th century, some years after the English one.

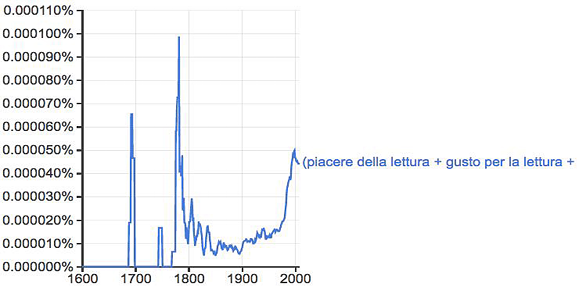

Graph 4. Words and phrases indicating the existence of the discourse on love of reading in the Italian language literature 1650–2000 according to Google Books Ngram Viewer. Moving average 3. Done May 14, 2019.

I have tried to glean Italian phrases related to love of reading from the texts and websites about reading as well as using the tools of GBNgV. So far, I have been able to build a string of phrases as follows: “piacere della lettura+gusto per la lettura+amore per la lettura+piacere di leggere+passione per la lettura+interesse per la lettura+gusto di leggere+motivazione alla lettura” (Graph 4).

When these phrases are set in the search window of GBNgV, the following graph is the result.

The enduring discourse on the love of reading seems to have come to Italy in the last decades of the 18th century.

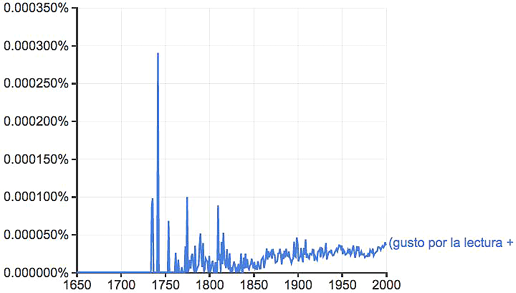

With a same kind of try and error method, a set of Spanish phrases can be gathered: “gusto por la lectura+interés por la lectura+pasión por la lectura+afición por la lectura+amor por la lectura+deseo de leer+gusto de leer” (27.8.19, moving average 0)

The Spanish discourse on the love of reading seems to have started in the mid-18th century but maybe around the 1770s as a continuing discourse.

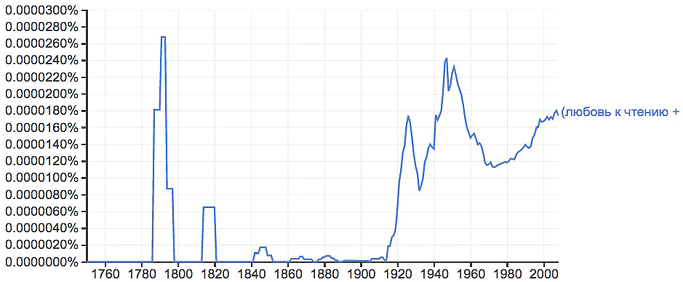

For the Russian language, I have been able to gather the following phrases: “любовь к чтению+страсть к чтению+вкус к чтению+желание читать+ охота к чтению” (Graph 6).

Graph 5. Words and phrases indicating the existence of the discourse on love of reading in the Spanish language literature 1650–2000 according to Google Books Ngram Viewer. Moving average 3. Done August 27, 2019.

Graph 6. Phrases indicating the existence of the discourse on love of reading in the Russian language literature 1650–2000 according to Google Books Ngram Viewer. Moving average 3. Done July 25, 2019.

There have been some tentative appearances of these phrases in the Russian literature since the end of the 18th century, and during the 19th century there has been sporadic low discursive activity, but an enduring and voluminous discourse has only started after the Russian Revolution.

Using National Full-Text Databases

Since further languages within my reach are not included in Google Books Ngram Viewer service, other methods to extend the analysis into new languages must be found. There are ways to do this, even if it is much more tedious work than with the GBNgV. Most of the European countries have digitized large parts of their books and newspapers. The national libraries present often their databases of digitized publications free on the Web, which enables one to get at least a summary picture of the diffusion of the discourse on love of reading. The negative side is that the picking of the data often has to be done more or less manually.

I have been able to include the following countries or language areas into my study: the Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and Poland. The order is accidental. Each of the countries or areas present challenges stemming from the availability of data, i.e., the technical qualities of the databases, but also from the historical background and the presence of multiple languages in the areas.

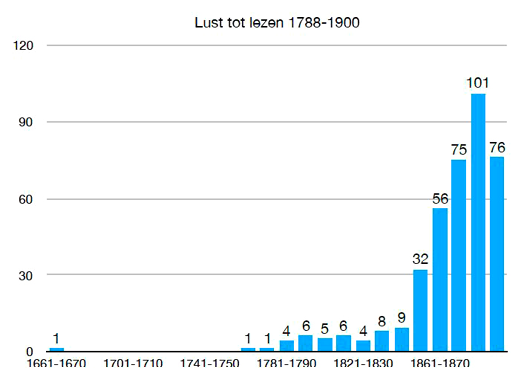

The Netherlands

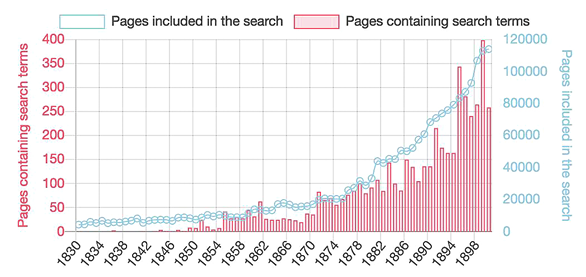

The most popular phrase when talking about love of reading in the Dutch language seems to be lust tot lezen. Another term, although much less used, is leeslijst (or leeslust). Other potential phrases, such as liefde voor lezen, passie voor lezen and smaak voor lezen seem to appear only sporadically (and they are not included in Graph 7), which is the case also of the German word Leselust that sometimes has appeared in Dutch newspapers in the 19th century. Through searches in the Delpher6 database of the Dutch Royal Library (comprising of books, periodicals and newspapers), I have been able to construct the following graph on the early phase in the discourse on love of reading.

The decisive difference between the graphs done with GBNgV and this one that must be borne in mind is that GBNgV displays relative values, i.e., what is the percentage of the phrases or, more precisely, ngrams including the phrases of the total number of ngrams, whereas the graph on the appearance of lust tot lezen and leeslijst displays absolute figures, as do all graphs in the rest of the article.

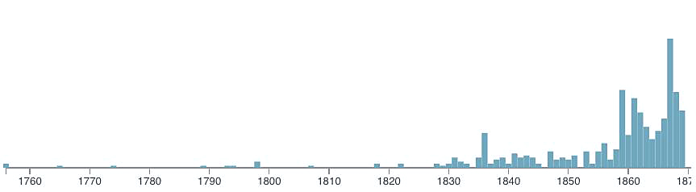

Graph 7. Lust tot lezen and leeslijst in Dutch literature in 1761–1900. Data obtained from the database Delpher of the Dutch Royal Library. Done October 16, 2019.

The first appearance of leeslijst seems to have come already in 1668, and of lust tot lezen in 1788, but an enduring rise in the appearances of the terms starts first in the 1850s. The Dutch case highlights the question of how do we interpret the data: when can we say that a discourse on love of reading starts? Does it start when the suitable words or phrases are printed for the first time, or do we demand that there should be some kind of solid increase in the number of the appearances? There is nothing special in these words and phrases, and they consist of ordinary words, so it is reasonable to assume that the word leeslijst or the phrase lust tot lezen or some equivalent can be used without the existence of a genuine discourse, or as part of other discourses. In this case, we could decide that the discourse on love reading in the Netherlands starts in the 1760s.

On the other hand, there is reason to believe that the entering of the discourse happened twice as a two-step process. The proximity to France, Great Britain, and Germany made it possible and probable that the discussions on reading were known also in the Netherlands. The Dutch literature and newspapers were, on a sufficient level, able to transmit this to the Dutch public already in the 17th century, but a new wave of discussions, this time as a genuine discourse, started to bloom in the 1850s, when the new forms of mass society demanded again the public debate on the issues of reading.

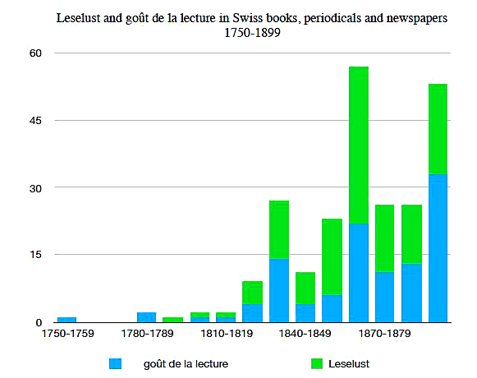

Switzerland

Switzerland is really an interesting case, because it is a country with more than one language (French, German, Italian, Romansh), although this time we must limit our presentation to two of them, French and German. The full-text database of the Swiss National Library for digitized newspapers does not cover all cantons and newspapers, so the researcher is compelled to use multiple regional databases and even then there is little hope of completeness. In any case, using the database for digitized books, periodicals and newspapers of the Swiss National Library and regional databases of digitized newspapers,7 I was able to construct the following graph, where the appearances of the French goût de la lecture and the German Leselust are counted.

Graph 8. Goût de la lecture and Leselust in Swiss books, periodicals and newspapers 1750‒1899 according to data from various databases accessed through the website of the Swiss National Library.

Because of the fragmentation of the databases, the graph can only give a rough picture of the evolution of the discourse on love of reading in Switzerland. As in the case of the Netherlands, there is a long incubation period for the discourse on love of reading in Switzerland. A more decisive increase in the number of appearances of the pertinent words and phrases begins in the 1820s.

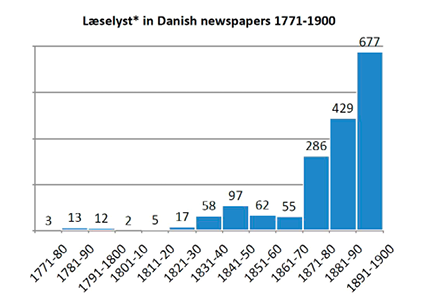

Denmark

The term denoting love of reading in the Danish language, læselyst, has apparently been adopted from the German Leselust in the 18th century (the etymology should be studied separately). The service Mediestream8 of the Danish National Library allows us to draw the following graph (Graph 9).

Graph 9. Læselyst, læselysten etc. in Danish newspapers 1771‒1900. Data from the database Mediestream of the Danish Royal Library.

It seems that in Denmark, the concept of the love of reading (or words denoting it) was known already since the 1770s, and not in negligible numbers, but perhaps the turbulent years during the first decade of the 19th century discouraged a steady rise in the use of the term. A new beginning came in the 1820s and 1830s. In the final decades of the 19th century, after the dramatic decades 1850s and 1860s, the discourse soars into unprecedented heights. It would seem that the discourse on the love of reading experienced a three-step evolution in Denmark. Still, I would say that the factual discourse in Denmark did start already in the 1770s, which is rather early in comparison with other comparable countries.

Why did the discourse enter Denmark so early? The proximity of Germany is an important explanation. The border against the German Reich was porous. In fact, Denmark was, until the mid-19th century, a mixed Danish-German state, because the German duchy Holstein and the mixed German-Danish duchy Schleswig were under the Danish crown. German was widely spoken and understood in Denmark. There was something peculiar and original in Denmark in the 18th century. David Kirby has characterized Denmark as “model example of a liberal state,” even if it formally was an absolute kingdom until 1848. Censorship was moderate, there was religious tolerance, and the enlightened administration was engaged in social and economic reforms.9 The Danish case is worth more study, but this time we must move forward. What we can say is that the discourse on the love of reading found a fruitful ground in Denmark.

Sweden

The other traditional Scandinavian kingdom, Sweden, shows a bit slower start for the discourse. The strategic term, läselust (nowadays läslust ) appears to have been adopted from German, perhaps via Danish, at least in its meaning of love of reading. The term läselust had appeared in a Swedish printed book as early as 1741,10 but it was then used in a different pedagogical meaning than what we are interested in. But the second time the term appeared in print was in 1765 in an article in Götheborgska Nyheter (27.12.1765), and this time perfectly with the same meaning as the German Leselust, which means that the word and the concept were known in the language, as well as the discussion on reading that was going on in Germany. The quotation from the newspaper article of 1765 is worth reading:

Foreigners admit that the Swedish scholars are not inferior to them when knowledge is considered; therefore, they wonder, why so little is written in Sweden. But they don’t take into account the difference in demand and love of reading [läselust] in the public. When in other countries reading is so common that also drivers and lackeys, when they are waiting for their masters and mistresses outside the gate, take up a comedy, a history, a biography or something of that sort to read, there are many good people in Sweden that, besides the hymnbook, catechism, and perhaps the Bible and a book of homilies, never have taken a book in hand. Here and there reigns still such a darkness that many of the Capitalists would forget how to read in a book, if not, fortunately, we didn’t have any other money than printed banknotes.11

Still, additional appearances of the word came slowly. Often the word läselust was used in pedagogical discussions meaning “eagerness for study.” There also were sporadic appearances of phrases that mediated the meaning of the love of reading in one way or another, such as läsebegär (passion for reading), lust att läsa (desire to read), håg till läsning (desire for reading), läshåg (desire for reading), but they seem not to have added much to the discourse.

If we put one after another, as many as possible of the Swedish words or phrases related to love of reading, e.g., like this: “läselust OR läselusten OR läslust OR läslusten OR läsebegär OR läsebegäret OR läsbegär OR läsbegäret OR lust at läsa OR lust att läsa OR håg till läsning,” we automatically get the following graph from the digital newspaper archive of the Swedish Royal Library (Graph 10) 12.

Graph 10. The words and phrases related to love of reading in Swedish newspapers 1755‒1870 according to the graph produced by the database of digitized newspapers of the Swedish Royal Library.

There is a modest concentration of words and phrases related to love of reading in the 1790s, but a more active discussion seems to first have started in the 1830s. During the 1830s, there were altogether 45 appearances of these words. A more dramatic rise in the discourse came in the 1860s, probably even here as a result of political and social reforms as well of the increase in the number of newspapers.

Norway

The literary language used in Norway was since the old times the same as the literary Danish, because Norway was an integral part of the Danish realm until 1814, when the country came under the Swedish throne, but with a wide autonomy. In the course of the 19th century, the linguistic circumstances changed in Norway, but during the period we are interested in this article the strategic term for the love of reading used in Norway was the same as in Danish, namely læselyst. For the latter part of the 19th century leselyst must also be taken into account.

With the help of the digitized collection of newspapers of the Norwegian National Library,13 the following graph can be made (Graph 11).

Graph 11. Different forms of the words læselyst and leselyst in Norwegian newspapers 1780‒1879. Data from the newspaper database of the Norwegian National Library.

We can deduct from the graph that the discourse was introduced into Norway already in the 1780s, but an enduring discourse on the love of reading was started in the 1820s. It is, of course, so that during the time when Norway was part of Denmark, Norwegians were part of the publicity of the whole realm. In this sense, they were part of the discourse on the love of reading that flourished in Denmark. On the other hand, the discourse that seems to have started in Norway in the 1820s probably had a new national character. Norway is our first example of many European countries and nations that were at some point of their history part of another state, realm, or country. The networks of linguistic and political power shifted greatly during the centuries.

Iceland

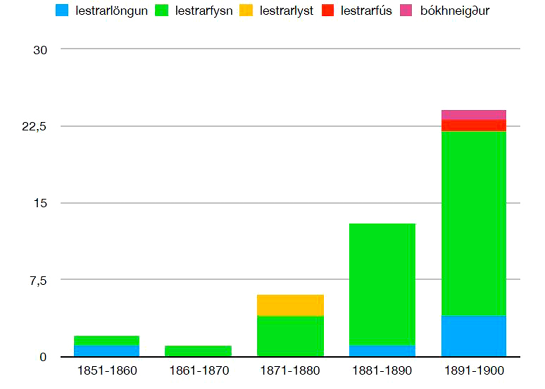

Iceland is another example of this circumstance. It belonged to Denmark during the whole 18th and 19th centuries, but during the 19th century, Icelandic newspapers began to appear. Based on searches in the database of the Icelandic National and University Library,14 it seems that terms related to the love of reading (lestrarlöngun, lestrarfýsn) start to appear in small numbers in the 1850s; later, other similar terms begin to appear (lestrarlyst, lestrarfús, bókhneigður). A more voluminous discourse seems to have started in the 1870s (Graph 12).

Graph 12. The appearance of words related to love of reading in Icelandic literature 1851‒1900. Data from the database Timarit of the Icelandic National and University Library.

Latvia

When we move to the eastern shores of the Baltic See, questions of nationality, domination, cultural deprivation, etc. become even more acute than with the regions mentioned above.

In Latvia, the cultural and economic power was, in the 18th and 19th centuries, in the hands of a German minority. All cultural novelties, reforms, etc. had to come through the German-speaking elite, even those that were propagated in Latvian, because it was the German priests and other progressive people that edited even the newspapers in the Latvian language. That is why any discussion about the readin g behavior of the Latvians was conducted by German speakers. Only during the latter part of the 19th century the Latvian-speaking majority started to gain more visibility as subjects and not, in the first place, as objects of discourse.

In German language newspapers appearing in Latvia (in reality the borders of the regions did not follow national or linguistic borders) there were writings about the reading behavior of the Latvians beginning with the 1850s. The status of Leselust among the Latvians was written about at least in 1858, 1861 (twice), 1862, 1863 (twice), etc. In the Latvian language, phrases related to love of reading (such as luste us lassischanu, patikschana us grahmatu lassischanu and lusti us grahmatahm – all in old orthography15) appeared in 1805, 1845, 1853, 1855, 1867, etc. From these sporadic data, we can estimate that the discourse on the love of reading about Latvians began earnestly in the 1850s. Of course, the discourse concerning the Leselust of the German-speaking population followed closely the debate in Germany proper.

Estonia

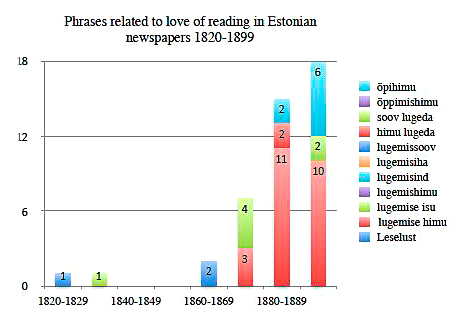

The situation with the German cultural domination was rather similar in Estonia, although both the present day Latvian and Estonian territories belonged to the Russian realm. Judging by the data obtained from the database Digar16 of the Estonian National Library, the discourse on the love of reading was initiated in Estonia in the 1820s, but got a firm position in the 1860s and 1870s (Graph 13).

Graph 13. Words and phrases related to love of reading in Estonian newspapers 1820‒1899. Data from the database Digar of the Estonian National Library.

There is a variety of words that denote the love of reading in Estonian, but during the late 19th century, lugemise himu, the love or passion for reading, was the most popular.

Finland

Finland was in the 19th century a Grand Duchy in the Russian realm, but even there the society was dominated not by Russians but by a Swedish-speaking elite, a reminiscence of the centuries long attachment to the Swedish realm that ended in 1809, when Russia took over. Only towards the end of the century the Finnish-speaking majority began to have something to say on the cultural and political mat ters in the country, but even in Finland it was the progressive elements of the Swedish-speaking elite that opened the discourse on the love of reading among the Finns or the rural population in general, both in Swedish and Finnish. In Swedish, the discussion, in the spirit of popular enlightenment, started at the beginning of the 1840s. The Swedish speaking elite was aware of the international discourse decades earlier, but they constituted only a few percent of the total population.

Finland is a peculiar case, because we know rather precisely when a Finnish word for love of reading was born or coined. It was Wolmar Schildt, originally a Swedish-speaker as well, known by his Finnish pen-name Kilpinen, who among many other useful words introduced into the Finnish language the word lukuhalu, literally “reading desire” or “reading lust.” It was for the first time printed in a short newspaper article in the newspaper Kanava (no. 27, July 12, 1845) about a poor landless man who so eagerly wanted to read that he proposed to the pastor of the parish that they could divide the subscription fee of a newspaper. The word was adapted from the Swedish word läselust. The concept of love of reading was known in Finnish even before 1845, but it was expressed in more clumsy phrases in the few cases when it had appeared in print.

After Schildt-Kilpinen’s invention, the discourse on love of reading in Finnish really got air under its wings, of course aided by other favorable trends, such as the rise of the nationalistic movement, the more liberal political atmosphere after the Crimean War (1854–1856), economic progress, etc.17

Lukuhalu is a concise term that comprises an idea of a personal reading activity above the level of mechanic literacy. Its importance lies in the fact that it connected the Finnish vocabulary on reading with a Pan-European discourse on love of reading.

Still, the discourse on love of reading was conducted in Finland in two languages, Swedish and Finnish.

Graph 14. Lukuhalu, läselust and läslust in Finnish newspapers 1830‒1900 according to the database of digitized newspapers of the Finnish National Library.18

Based on this data (Graph 15), we may safely conclude that the discourse on love of reading entered into Finland in the 1840s, although even here a greater increase occurred in the 1850s. This applies both the discussion concerning and visible to the Finnish speaking majority but the considerable Swedish speaking rural population as well.

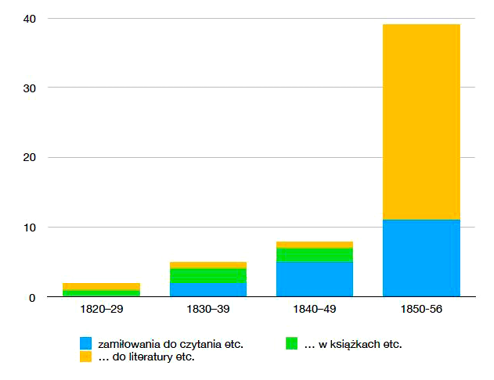

Poland

I would have wished to include into this study the birth of the Lithuanian discourse on love of reading as well, but this must be left for the future. On the other hand, Lithuania had since middle ages been attached to Poland, and the land-owning class, as well as the cultural elite, were Polish-speaking still in the 19th century. We can perhaps assume that the discourse on love of reading appeared in Lithuania approximately at the same time as in Poland. Poland was, during the 19th century, divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria, but there was a lively newspaper production in the Polish language, which is available in the database Polona of the Polish National Library.19 By trial and error, I have come to the conclusion that the Polish phrase for love of reading may be zamiłowania do czytania (literally: passion for reading), although another phrase, zamiłowania do literatury (passion for literature), seems to appear more often. These phrases appeared even already during the 1830s and the 1840s, but, at least in the newspapers, the Polish discourse on love of reading seems to have started voluminously in the 1850s. Of course, in this, as in many other cases, a more linguistically competent researcher may get more precise results.20

Graph 15. Phrases related to love of reading in Polish language newspapers 1820‒1856. Data from the database Polona of the Polish National Library.

Putting the Love of Reading on a Map

Graph 16. Diffusion of the discourse on love of reading in Europe till the 20th century. Map from I. K. Inha: Kansakoulun karttakirja. 2nd ed. Helsinki:Valistus, 1909, p. 22‒23.

At this point it is possible to draw a preliminary map of the diffusion of the discourse on love of reading. The map, where the dates are set, is itself part of history. It is taken from a Finnish school atlas designed by I. K. Inha, a Finnish geographer and photographer. The atlas was printed in 1909 and reflects the political realities of the 19th century.21 This may help the reader to avoid automatically projecting the present day borders and national identities on the situation for more than a hundred years ago. It was a different world then.

Discussion

When looking back at the data used in this article, it seems that there have been at least two waves of the discourse on the love of reading in Europe. The first wave followed directly after the initial launching of the discourse in France and other cultural “great powers.” This is seen in the data from, e.g., the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden. This phase of the discourse did not, however, produce a more voluminous debate on love of reading, because social, political and economic conditions were not developed enough. The great wave of the discourse came in the 19th century, when it really penetrated the whole of Europe. Among the background factors we can count industrialization, democratization, mass education, a freer press, as well as an emerging book market with affiliated institutions, such as bookshops and popular libraries.22 A factor not to be neglected was the invention of making paper out of wood, which made the making of publications much cheaper.23 One of the most important factors was the emergence of the language-based nationalism. In many areas, a need for literature in the hitherto neglected languages was felt, and this entailed the necessity to create a public that would read this literature. There was a social demand for love of reading. The history of the discourse on love of reading also is a story of the social, linguistic and ethnic as well as gendered emancipation.

It is probable that concerning many countries, a more detailed research would set the date of the arrival of the discourse on love of reading earlier. In this article, there was no possibility to detect “weak signals.” Of course, quite a lot depends on the criteria that are chosen for the identification of the start of the discourse.

Conclusion

In any case, what is essential in this article is that it seems to be possible to study the migration of this kind of discourses transnationally and multi-linguistically, and that the result can be presented visually. It is almost needless to state that the methods need refining and that the historical background research needs deepening. The use of methodically constructed linguistic corpora would be desirable, but it is not enough to study a language at a time. It should be possible to compare the corpora of multiple languages, perhaps to build a multilingual corpus, especially concerning areas with a multilingual history. A team of scholars from different fields (history, linguistics, geography, statistics, computer science) should be engaged, and other discourses than the one that has been targeted here should be studied. It is possible to study the whole life span of the discourses and visualize the enormous network of cultural discourses on a global scale.

Bibliography

1. AIDEN, Erez & MICHEL, Jean-Baptiste. Uncharted: Big Data and an Emerging Science of Human History. New York: Riverhead Books, 2014.

2. INHA, I. K. Kansakoulun karttakirja. 2nd ed. Helsinki:Valistus, 1909.

3. KIRBY, David. The Baltic World 1771-1993. Europe’s Northern Periphery in an Age of Change. London and New York: Longman, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr/101.4.1230

4. Langenbucher, Wolfgang R. Die Demokratisierung des Lesens in der zweiten Leserevolution. Dokumentation und Analyse. In GÖPFERT, Herbert G. [et al.] (eds.). Lesen und Leben. Eine Publikation des Börsenvereins des Deutschen Buchhandels in Frankfurt am Main zum 150. Jahrestag der Gründung des Börsenvereins der Deutschen Buchhändler am 30. April 1825 in Leipzig. Frankfurt a.M.: Buchhändler-Vereinigung, 1975, p. 12-35. https://doi.org/10.1086/620751

5. LYONS, Martin. New Readers in the Nineteenth Century: Women, Children, Workers. In Cavallo, Guglielmo & Chartier, Roger (eds.). A History of Reading in the West. Translated by Lydia G. Cochrane. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999, p. 313–344. https://doi.org/10.1086/427573

6. MÄKINEN, Ilkka. Leselust, Goût de la Lecture, Love of Reading: Patterns in the Discourse on Reading in Europe from the 17th until the 19th Century. In NAVICKIENĖ, Aušra et al. (eds.). Good Book, Good Library, Good Reading. Studies in the History of the Book, Libraries and Reading from the Network HIBOLIRE and Its Friends. Tampere: Tampere University Press, 2013. 315 p. ISBN 978-951-44-9142-9. Access through Internet <http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:uta-201404021299> (Aug 31, 2019).

7. MÄKINEN, Ilkka. Why People Read: Jean-Jacques Rousseau on the Love of Reading. In GUSTAFSSON, Dorrit; LINNOVAARA, Kristina (eds.). Essays on Libraries, Cultural Heritage and Freedom of Information. Festschrift published on the occasion of Kai Ekholm’s 60th birthday on 15 October 2013. Helsinki: The National Library of Finland, 2013, p. 127-136. Access through Internet <http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:uta-201402171136> (Aug 31, 2019).

8. MÄKINEN, Ilkka. Reading Like Monks: The Death or Survival of the Love of Reading? In LAURISTIN, Marju; VIHALEMM, Peeter (eds.). Reading in Changing Society. Tartu 2014. S. 13-27. ISBN 9789949325757. Access through Internet <http://www.tyk.ee/admin/upload/files/raamatud/1400157894.pdf> (Aug 31, 2019). https://doi.org/10.26530/oapen_496790

9. MÄKINEN, Ilkka. From Literacy to Love of Reading: The Fennomanian Ideology of Reading in the 19th-century Finland. Journal of Social History, 2015, Vol 48, p. 287-299. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/shv039

10. MÄKINEN, Ilkka. Love of Reading Meets PISA Assessments: Historical Insights in the Discourse on Reading Motivation. Knygotyra, 2018, vol. 70, p. 57-77. https://doi.org/10.15388/knygotyra.2018.70.11808

11. MICHEL, Jean-Baptiste et al. Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books. Science, 2011, Vol. 331, Issue 6014, p. 176-182.

12. SAOB. Ordbok över svenska språket utg. av Svenska akademien. 16. bandet. Stockholm: Svenska Akademien, 1942, spalt L 1743. Access through Internet: <https://www.saob.se/artikel/?seek=l%C3%A4slust&pz=1#U_L1519_250298> (Oct 17, 2019).

13. Wittmann, Reinhard. Was There a Reading Revolution at the End of the Eighteenth Century? In Cavallo, Guglielmo & Chartier, Roger (eds.). A History of Reading in the West. Translated by Lydia G. Cochrane. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999, p. 284–312. https://doi.org/10.1086/427573

1 Wittmann, Reinhard. Was There a Reading Revolution at the End of the Eighteenth Century? In Cavallo, Guglielmo & Chartier, Roger (eds.). A History of Reading in the West. Translated by Lydia G. Cochrane. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999, p. 284–312.

2 Mäkinen, Ilkka. Leselust, Goût de la Lecture, Love of Reading: Patterns in the Discourse on Reading in Europe from the 17th until the 19th century. In Navickiene, Aušra [et al.] (eds.). Good Book, Good Library, Good Reading. Studies in the History of the Book, Libraries and Reading from the Network HIBOLIRE and Its Friends. Tampere: TUP, 2013, p. 263–287.

MÄKINEN, Ilkka: Why People Read: Jean-Jacques Rousseau on the Love of Reading. In GUSTAFSSON, Dottit and LINNOVAARA, Kristina (eds.). Essays on Libraries, Cultural Heritage and Freedom of Information. Festschrift published on the occasion of Kai Ekholm’s 60th birthday on 15 October 2013. Helsinki: The National Library of Finland, 2013. 127–136.

Mäkinen, Ilkka. Reading like Monks: The Death or Survival of the Love of Reading? In: Lauristin, Marju and Vihalemm, Peeter (eds.). Reading in Changing Society. Tartu: University of Tartu Press, 2014, p. 13-27. Access through Internet: <http://www.tyk.ee/admin/upload/files/raamatud/1400157894.pdf>

Mäkinen, Ilkka. From Literacy to Love of Reading: The Fennomanian Ideology of Reading in the 19th-century Finland. Journal of Social History (2015), pp. 1–13.

MÄKINEN, Ilkka. Love of Reading Meets PISA Assessments: Historical Insights in the Discourse on Reading Motivation. Knygotyra, 2018, vol. 70, p. 57–77.

3 This article is part of a larger project that I am conducting together with Jukka Tyrkkö (Linnæus University, Växjö, Sweden). Its working title is “‘Nature has implanted in you a Love and Taste for reading’: New corpus-driven approaches to studying longitudinal trends and geographical diffusion in the history of reading.”

4 Google Books Ngram Viewer is freely available in <https://books.google.com/ngrams>.The principles and goals of GBNgV are presented in <https://books.google.com/ngrams/info> . More information: <http://storage.googleapis.com/books/ngrams/books/datasetsv2.html> . Information in depth about the construction of Google Books Ngram Viewer, see Michel, Jean-Baptiste [et al.]. Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books. Science, 2011, Vol. 331, Issue 6014, p. 176-182. Access through Internet: <https://science.sciencemag.org/content/331/6014/176>. See also Aiden, Erez and Michel, Jean-Baptiste. Uncharted: Big Data and an Emerging Science of Human History. New York: Riverhead Books, 2014.

5 In GBNgV it is possible to set a moving average for a chosen number of years. E.g., the moving average of 3 means that the values of three years in both directions, left and right, from the chosen year are counted as an average. This makes the curve smoother and helps to detect more persistent trends.

7 The following databases were used: <https://www.e-helvetica.nb.admin.ch/>, <https://www.e-periodica.ch/>, <https://www.e-newspaperarchives.ch/> and a selection of databases in <https://www.e-newspaperarchives.ch/?a=p&p=onotherplatforms&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN--------0----->.

9 Kirby, David (1995). The Baltic World 1771–1993. Europe’s Northern Periphery in an Age of Change. London and New York: Longman, p. 87.

10 SAOB. Ordbok över svenska språket utg. av Svenska akademien. 16. bandet. Stockholm: Svenska Akademien, 1942, spalt L 1743. Access through Internet: <https://www.saob.se/artikel/?seek=l%C3%A4slust&pz=1#U_L1519_250298>.

11 Translated from English by the author. The original quotation: “Utlänningar medgifwa, at de Swenske Lärde, ej eftergifwa dem i lärdom; undra därföre, hwarföre i Swerige så litet skrifwes. Men de betänka intet en olika afsätning och läselust hos Almänheten. Då i andra Länder är så almän läsning, at ock Kuskar och Laquaier, medan de utanför hus-porten wänta på sit Herrskap, taga de up en Commödie, en Historia, en Memoire och dylikt, at läsa på; så finnes i Swerige mycket godt Folk, som, utom Psalmbok, Cateches, och kanske Bibel och Postilla, aldrig taget bok i hand. Här och där fins wäl ännu sådant mörker, at mången Capitalist kunnat glömt läsa i bok, om icke, til all lycka, wi ej haft andra pengar, än tryckta Banco-sedlar.”

14 <timarit.is>.

15 Thanks to Pauls Daija for the help he gave me with the Latvian terms.

17 For a closer look at the Finnish case, see MÄKINEN 2015.

20 The end year 1856 is there because, when I found a certain saturation of the phrases I was looking for, I ended the search.

21 A remarkable fact is that in the map there is a border between Finland and Russia as thick as the other national borders. Finland was, at the time of the printing, a Grand Duchy attached to Russia, certainly with an internal autonomy, but still part of the Russian Empire.

22 See for example LYONS, Martin. New Readers in the Nineteenth Century: Women, Children, Workers. In Cavallo, Guglielmo & Chartier, Roger (eds.). A History of Reading in the West. Translated by Lydia G. Cochrane. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999, p. 313–344.

23 Langenbucher, Wolfgang R. Die Demokratisierung des Lesens in der zweiten Leserevolution. Dokumentation und Analyse. In GÖPFERT, Herbert G. [et al.]. Lesen und Leben. Eine Publikation des Börsenvereins des Deutschen Buchhandels in Frankfurt am Main zum 150. Jahrestag der Gründung des Börsenvereins der Deutschen Buchhändler am 30. April 1825 in Leipzig. Frankfurt a.M.: Buchhändler-Vereinigung, 1975, p. 12-35.