Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2022, vol. 78, pp. 17–45 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2022.78.105

Gambling on a Sale: Gift-enterprise Bookselling and Communities of Print in 1850s America

Kristen Highland

American University of Sharjah

University City, PO Box 26666, Sharjah, UAE

E-mail: khighland@aus.edu

Summary. This article explores the phenomenon of the gift enterprise bookstore in the mid-nineteenth-century United States. An early form of premium marketing, the gift-book enterprise promised to reward each book purchase with a surprise ‘gift’, ranging from pencils to dress patterns to cutlery to jewellery. A novel form of marketing books, the gift enterprise bookstore teetered on a thin line between sensation and sham. Although decried as form of illegal lottery gambling and beset by accusations of dishonesty, gift-book enterprises grew immensely popular. Drawing on extensive archival research on one of the most successful gift-book enterprises, the bookstores of G.G. and D.W. Evans—operating in urban centres from 1856–1861—this article examines gift enterprise bookselling in the context of mid-nineteenth-century American print cultures. As savvy entrepreneurs, the Evans’ leveraged the national reach and perceived authority of the newspaper by engaging in debates over the morality and legality of the business in the columns of widely-circulating papers and capitalised on editorial and reprinting practices to endorse their business model and market their bookstores. In addition, in lengthy bookseller catalogues distributed across the nation, the Evans’ created a bookstore in print and shaped inclusive imagined and real communities of reader-book buyers. Examining the print culture of Evans’ gift-book enterprise offers new insights into nineteenth-century book marketing and the ways in which gift enterprise bookselling was intimately connected to and inseparable from contemporary print forms, networks, and practices. Taking the gift-book enterprise seriously expands the histories of American bookselling and decentres the dominant focus on large publishers. In addition, the gift-bookstore phenomenon highlights how bookselling is always entwined with larger cultural dynamics.

Keywords: bookselling, bookstores, United States, book marketing, premiums, book catalogues, newspapers, nineteenth century

Loterija knygynuose: dovanomis skatinama knygų prekyba ir spaudos bendruomenės XIX a. šeštojo dešimtmečio Amerikoje

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjamas dovanomis skatinamos knygų prekybos fenomenas XIX a. viduryje Jungtinėse Valstijose. Ankstyvoji priedų prie esamos prekės rinkodaros forma, dovanų-knygų parduotuvės žadėjo nustebinti ir apdovanoti kiekvieną knygos pirkėją netikėta „dovana“ – nuo pieštuko iki suknelės, stalo įrankių ir papuošalų. Ši nauja knygų rinkodaros forma balansavo ties plona riba tarp sensacijos ir apgaulės. Nors ji ir buvo viešai smerkiama kaip nelegalių loterijų forma ir apkaltinta nesąžiningumu, dovanų-knygų prekiautojai tapo nepaprastai populiarūs. Remiantis išsamiais archyviniais tyrimais apie vieną sėkmingiausių tokių įmonių, Georgo Greeliefo ir Danieliaus W. Evansų knygynus, veiklą vykdžiusius miestų centruose 1856–1861 m., šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjama dovanomis skatinama knygų prekyba XIX a. vidurio Amerikos spaudos kultūrų kontekste. Sumanūs verslininkai Evansai išnaudojo nacionalinę aprėptį bei suvokė plačiai cirkuliuojančių laikraščių įtaką, todėl straipsnių skiltyse sukeldavo diskusijas apie verslo moralę ir teisėtumą; tokiu būdu jie susikrovė kapitalą pasinaudodami vedamųjų straipsnių bei pakartotinio spausdinimo praktika, kad galėtų paremti savo verslo modelį ir reklamuotų savo knygynus. Be to, ilguose knygų pardavėjų kataloguose, platintuose visoje šalyje, Evansai sukūrė „spausdintą“ knygyną ir suformavo įtraukias įsivaizduojamas ir tikras skaitytojų-knygų pirkėjų bendruomenes. Nagrinėjant Evansų dovanų-knygų parduotuvių spaudos kultūrą, atsiveria naujos įžvalgos apie XIX amžiaus knygų rinkodarą ir būdus, kuriais dovanomis skatinama knygų prekyba yra glaudžiai susijusi ir neatskiriama nuo šiuolaikinių spaudos formų, tinklų ir praktikų. Rimtas požiūris į dovanomis skatinamą knygų prekybą praplečia amerikiečių knygų pardavimo istoriją ir į šoną nustumia dominuojantį dėmesį stambiems leidėjams. Be to, dovanų-knygų parduotuvių fenomenas išryškina tai, kaip knygų prekyba yra visuomet susipynusi su didesne kultūros dinamika.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: knygų prekyba, knygynai, Jungtinės Valstijos, knygų rinkodara, priedai prie esamos prekės, knygų katalogai, laikraščiai, XIX amžius.

Received: 2021 11 07. Accepted: 2022 03 17

Copyright © 2022 Kristen Highland. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

In June of 1856, an advertisement appeared in the widely circulated daily newspaper, The New York Herald, for booksellers Evans & Co. At their ‘gift book enterprise’ on Broadway, the advertisement promised, patrons might ‘tempt the fickle Goddess of Fortune’ by buying a book and receiving an extra ‘present’ with their purchase.1 Though it was printed in the ‘New Publications’ column, the single-paragraph advertisement eschewed listing book titles, focusing instead on the business model of the store and its benefits to customers. In an editorial third-person voice, Evans & Co. promised that ‘theirs is the fairest enterprise yet started.’ Though this was the first year that Evans & Co. operated a store on Broadway in New York City, George Greelief (G.G.) Evans and his brother, Daniel (D.W.) were joining what had been derisively labelled ‘the gift enterprise mania’ by another newspaper the year before.2

The gift enterprise, in which tickets or goods were sold with the promise of a guaranteed prize, was an early form of premium marketing.3 Though gift enterprises could be run by anyone issuing tickets, retailers—both honest and fraudulent—recognised a marketing opportunity. Booksellers were no exception. So-called gift-bookstores popped up in cities and towns across the country in the mid 1850s. These bookstores incentivised sales by promising patrons a randomly-selected gift with each book purchase. These gifts, also referred to as ‘presents’, ‘premiums’, ‘prizes’, and ‘dividends’, might include pencils, penknives, painted pins, dress patterns, bracelets, or spoons. The Evans’, who became among the best-known and long-lasting gift-bookstore proprietors, included extensive lists of potential gifts ranging in value from 25 cents to 100 dollars in their periodical advertisements and lengthy book catalogues. The most expensive and coveted prize was the gold or silver pocket watch.

Designed as an incentive model to drive up volume sales and lower book prices, the gift-book enterprise ostensibly sought to enrich both booksellers and publishers, as Evans & Co. claimed. ‘Publishers,’ they promised, ‘could sell the best dollar book ever published for fifty cents, and grow fatter on the profits.’4 And the customer, gift booksellers asserted, would benefit from the knowledge brought by the purchase of a good book. Amid accusations of fraud and gambling, this claim to intellectual and communal benefit was the foundation of defences of the gift enterprise bookstore. As G.G. Evans argued in his catalogues: ‘No matter how the desire [for literature] arises, either from a love of study or a prospect of gain, any movement having for its end the dissemination of knowledge must be beneficial.’5

The New York Herald, in which Evans & Co. first advertised their New York bookstore, was not convinced. In an 1858 article titled ‘The Swindlers of New York’ the paper took aim: ‘a gift book enterprise proprietor has, we notice, had the impudence to advertise his own views of his roguery as a quotation from this journal. We need not say’—though, of course, the article does—‘…that no person with any sense would have anything to do with them.’6 The unnamed target of this censure was almost certainly Evans’ ‘Great Gift Book Establishment,’ which had included a quoted endorsement attributed to the New York Herald in several of their catalogues. The endorsement? A reprint of their own 1856 Herald advertisement crediting Evans’ as the ‘fairest enterprise yet started’, where ‘hundreds of patrons have been pleased by tempting the fickle Goddess of Fortune.’7

Indeed, a veritable paper war was raging between Evans & Co. and the New York press. Robert E. Bonner’s New York Ledger, a weekly story paper that published such popular writers as William Cullen Bryant, FitzGreene Halleck, and E.D.E.N. Southworth, as well as Fanny Fern’s widely read column, regularly published heated denunciations of and warnings against ‘gift concerns’. A few weeks before the Herald article, the Ledger included a note about the ‘rascality’ of the gift enterprise operators in the city. ‘It is not probable,’ the paper opined, ‘that any intelligent person will hereafter send his money to these swindlers, for their “gift books”, “gift newspapers”, “gift pencils”, &c.’8 Evans & Co. responded to this opinion in the advertising section of the New York Herald, a mere two weeks before that newspaper’s own condemnation of New York swindles. Evans objected to the ‘indiscriminate’ libel of the Ledger’s column, and in turn, derided the Ledger as a paper ‘celebrated for the trashiness, nastiness, and bad grammar of its widely puffed stories.’9 In addition to insults, Evans & Co. also defended their ‘legitimate book business’ against charges of swindling and claimed the periodical press’ acrimony arose from competition between booksellers and newsmen for readers’ patronage, as well as bitterness over the gift enterprise’s successful premium sales model.

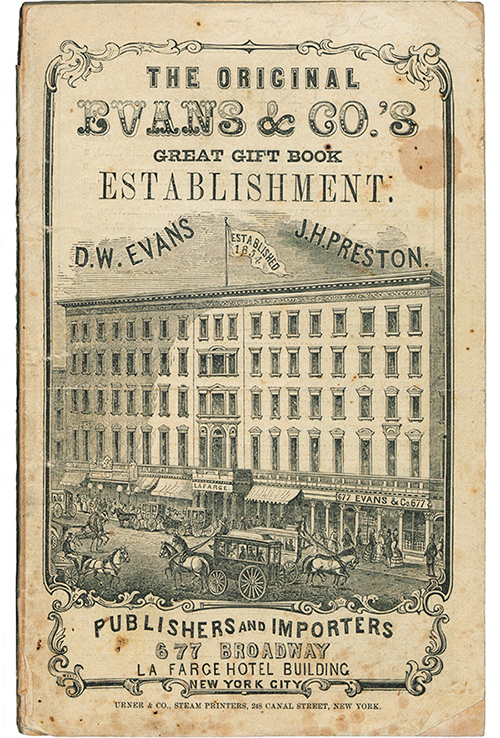

If books and newspapers competed for the eyes of the reading public in 1850s America, the gift-book enterprise—its rise, its popularity, its credibility—also depended upon the newspaper. Although booksellers and publishers had long advertised their books in advertisements and serialised fiction in the pages of newspapers and other periodicals, the gift-book enterprise expanded and deepened this cross-print engagement. Gift-book enterprises wove together a complex web of print relationships. Even as editorials lambasted gift enterprises as illegal forms of the lottery, advertising lists (sometimes on the same page) continued to promote them. For gift-book enterprises, the expanding circulation of print and specific periodical practices of reprinting were essential to business, from cultivating customers to building authority through reprinted endorsements and editors who traded puffs for prizes. In addition to engaging the print practices of newspapers, Evans’ gift-book enterprises published their own lengthy print catalogues that supported a thriving national mail-order business [Figure 1]. More than simple lists of books for sale, these dynamic catalogues acted as bookstores-in-print, marketing the gift enterprise sales model and consolidating communities of reader-customers. Although Evans maintained several permanent and seasonal bookstores in multiple cities, the gift-bookstore phenomenon was constructed more by print and its circulation.

Figure 1

Studies of book history and bookselling in the United States have overlooked the gift-enterprise bookstore. In the context of the history of consumer culture, historian Wendy Woloson productively examines gift concerns more broadly within the development of premium retailing, as well as within the ‘shadow’ urban economies of extra-legal commercial enterprise in the nineteenth century.10 From a book history perspective and as a specific model of gift concern, the gift-book enterprise highlights not only the development of new retailing models, but also connects mid-nineteenth-century bookselling practices and networks of print. All the rage—good and bad—for a time in the 1850s, the gift-book enterprise phenomenon depended simultaneously on the intimate communities of local periodicals and readers as well as the broad national reach of distribution networks. The rise and cultural significance of the gift-bookstore is thus entwined with the dynamics of nineteenth-century print culture. Drawing on extensive and original archival research, this article uses the Evanses and their ‘Great Gift Book Establishment’ as a case study to examine the ways in which the gift-book enterprise leveraged specific print forms, practices, and networks to expand the business of books in the mid-nineteenth century. In his examination of nineteenth-century urban economies of print, Paul Erickson persuasively argues for the value of studying ‘low-level entrepreneurs on the margins of respectability in the print trades’ in order to challenge received notions of nineteenth-century print capitalism and the boundaries of book history research.11 More than an aspect of the mid-nineteenth century’s cultures of sensation and speculation, the gift-book enterprise offers insights into forms of and developments in book marketing and expands histories of bookselling in the United States.

Newspaper Networks

The Evans’, and especially G.G. Evans, were shrewd promoters who exploited editorial authority and reprinting practices in an increasingly expansive and impersonal print network in 1850s America. They harnessed the various genres of the newspaper—the advertisement, editorial, letters, and public notices, even the form of the illustrated paper itself—in an integrated marketing strategy for self and company. G.G. and D.W. Evans did not come from a bookselling family. The eldest son of doctor Daniel Evans and his wife, Susan, George Greelief was born in early July 1828 in Bingham, Maine. Daniel would be born four years later, along with five additional siblings.12 The extended Evans family claimed several prominent American patriots; great-grandfather Daniel Evans sat in the Provincial Congress of New Hampshire and died in 1776 from wounds sustained at Bunker Hill and uncle George was the Honorable George Evans, a career politician in the United States House of Representatives and Senate.13 Young George and Daniel would eschew medicine and politics, however, for entrepreneurial endeavours. By 1850, 22-year-old George had left his Maine home to seek his fortune. Daniel, 17 years old and working as a labourer in his hometown, would follow in the next few years.

It is unclear when the Evans’ first entered the business of books. Their own advertisements claim an origin of ‘the first Book Enterprise ever projected’ —though this is a common claim— in 1854 in Lowell, Massachusetts.14 By 1856, the Evans brothers had moved to New York City and established their ‘Evans & Co. Gift Book Enterprise’ on Broadway.15 From there, their bookselling business (together and separately) would expand into permanent locations in Philadelphia and Boston, and either permanent or seasonal locations in cities such as Baltimore, Houston, and New Orleans. Through mail order, the Evans’ would ship their printed catalogues, books, and gifts throughout the country. By all accounts, the bookselling business of the Evans’ in the late 1850s was prosperous. R.G. Dun & Company, the credit reporting agency whose agents investigated businesses in cities and towns across the nation and wrote annual discursive assessments, remained positive about the Evans’ prospects. One agent noted the good credit of D.W. Evans in 1858 and that ‘he pays promptly’ and ‘is making money by his “Gift Enterprise.”’ The agent adds, ‘Other parties think rather favorably of him.’16 Additional entries over the next two years indicate that the Evans’ remained on good financial terms with successful businesses.

Key to their prosperity was aggressive advertising and promotion. The premium or gift was of course one mode of advertising. But to spread word of these gifts, the Evans’ exploited the meteoric growth of newspaper and magazine printing at mid-century.17 From the 1830 federal census accounting for nearly 900 newspapers, the number of weekly newspapers would grow to over 2,500 by 1850. Daily newspapers expanded from two dozen in 1820 to over 250 by 1850.18 This growth was fuelled by a number of factors, including an expanding commercial economy, new communication and transportation networks, developments in printing technology, low postal taxes, and a demand for political information, among others.19 Advertisements for the Evans’ gift-bookstores appeared in periodicals and newspapers with national reach like Harper’s Weekly and The New York Herald, and in the pages of regional and local newspapers from New Hampshire to Georgia to Ohio and Wisconsin.20 G.G. Evans claimed to advertise in over 800 weekly papers from July 1859 to March of 1860.21 For the gift-book enterprise, the copious and geographically expansive advertising was central to its reach and popularity in the 1850s.

For the Evans’, the genres of the newspaper, its printing practices, and its circulation networks became core tools in a marketing strategy that both disavowed and traded on the sensationalism of gift enterprises and gambling. In the columns of national newspapers, the Evans’ adjudicated their legal status and engaged in veiled debates with editors; in advertisement pages, they marketed their business model, books, and gifts. The core concern was the proximity of gift enterprises, including the gift-enterprise bookstore, to the lottery. Though lotteries had for years been chartered by governments and private entities for causes such as infrastructure improvements, education, and health institutional development, as well as for settling debts, disbursing estate property, and for pure entertainment, public opposition had grown in the 1830s.22 Charges of corruption, mismanagement, and moral degradation dogged lottery enterprises. Awards were not delivered as promised; lottery agents raked in scandalous profits from overpriced tickets; lottery spending syphoned profits from and spending in businesses. Concern grew over the lottery’s perceived threat to enlightenment models of the rational, disciplined individual who, seduced by the thrill of a winning ticket or the desperation of a losing one, could become trapped in a spiralling cycle of risk. Lotteries, it was feared—like other modes of gambling—might quickly lead a respectable clerk (or successful businessman) into financial ruin and moral decay.23 The ‘anxiety to win’, as it was called, risked individuals and society.24 Editorials accumulated; pamphlets circulated. Yet, while some local legislatures began prohibiting the government charter of lotteries, this did little to discourage private lotteries and increasingly, those originating in other states.25 Amid mounting public opposition, the persistent popularity of the lottery toed the fluid—and lucrative—line between recreation and vice.

Nineteenth-century bookstores already had a direct tie to lotteries; many stores hosted lottery offices. In New York City, for instance, J.A. Burtus ran a joint bookstore and lottery office near the East River docks for years until 1828. A few streets away Richard Scott dealt in books, lottery, and paper goods on Fulton Street. Additional booksellers marked a logical transition from selling lottery tickets to selling books and vice versa. Ezekial Petty of New York City expanded his lottery store into a bookstore in 1823.26 In smaller towns as well, bookstores might sell tickets for various lotteries. While the gift enterprise model was used (honestly or fraudulently) to sell a range of goods from pens to art prints to property, the bookstore and its books were associatively and physically linked with the lottery.27 The rise of the gift-enterprise bookstore melded these retail and speculative markets and attracted the same legal and moral resistance as other forms of lottery.

The push-pull of condemnation and sensation was a central appeal of the gift-enterprise, in which the popularity of the lottery and the sensationalism of gambling allowed gift enterprise proprietors to channel public curiosity into profits. Though the Evans brothers prominently and repeatedly lauded the honesty and integrity of their gift-bookstores in bookseller commentaries, customer testimonials, and publisher endorsements in their newspaper ads, they also leveraged—even encouraged—the persistent doubts over the credibility of gift enterprises. ‘If you do not wish to be deceived,’ quipped one Evans & Co. advertisement, ‘get it in the right store.’28 Nodding toward the potential for deception allows the Evans’ to assert their store as the ‘right’ honest one. Even that first advertisement in 1856 for Evans & Co. acknowledged a kernel of credibility doubt as the ‘fairest enterprise yet started.’ It was their immense success and popularity, the Evans’ regularly claimed, that prompted fraudulent imitators.29 The potential for fraud could thus be harnessed as a marketing tool. It could slyly promise the excitement of winning and risk-taking while distancing itself from actual deceit or humbug. In disclaiming any connection between their gift-book store and the ‘mock Dry Goods and pamphlet Gift Concerns about or near the City Hall,’ Evans & Co. sows a seed of doubt and reaps heightened interest. By referencing fraud in their marketing—even if to disavow it—the Evans’ invite the curious or dubious individual to come and inspect the premises and participate in the gift-book sale in order to judge its authenticity. Rather than a challenge or hindrance to their business, G.G. and D.W. Evans transformed the editorial condemnations of the lottery and gift enterprises into strategic marketing opportunities for their gift-book stores. All the better when their own gift-book enterprise advertisements appeared in the same newspaper.

In addition to exploiting the print discourse around lotteries and gift enterprises as a marketing tool, G.G. Evans used the newspaper and its editorial and printing practices to forge and burnish his own reputation. As Evans’ expansive business—stretching from North to South, from urban cities and rural eastern towns to settlements in Texas—depended on volume sales, it was imperative that people, many people, trust him. Postal reforms between 1845 and 1851 had reduced the cost of mailing letters, established a national standard of currency in stamps, and eventually, a registry system to regulate the sending of money.30 These reforms, as well as the expansion of road and rail networks to facilitate shipping, provided the material conditions for both honest and fraudulent sales-by-mail. Accompanying these reforms was a wave of anxiety about privacy and anonymity and the maintenance of social mores.31 ‘Send to someone [you] know in large cities,’ the New York City-based Pomeroy’s Democrat begged one subscriber in Kentucky, complaining that every year ‘honest people in the country lose millions of dollars’ to city swindles.32 An anonymous, amorphous postal culture heightened the potential for corruption and swindling and challenged public trust.

Local media ecologies, headed by known and trusted editors, acted as guides through this storm of anxiety, though they were not indifferent to influence. For gift enterprises, editors granted legitimacy to the schemes that crossed their desks by endorsing them in print. The gift enterprise tapped into this endorsement potential by exchanging free prizes or chances in exchange for a positive puff in print columns. When William H. Hall was arrested at a New York City post office for running a fraudulent gift enterprise scheme under the company name C. E. Todd Jewelers and Gold Pencil Manufacturers, investigators found nearly forty letters received in a single day from country newspaper editors requesting chances in the gift enterprise in exchange for a favourable recommendation.33 In one of the letters, the editor of the Perry County, Pennsylvania Democrat—also a member of the United States House of Representatives—enclosed a copy of his advertisement for C.E. Todd & Co, which had a run for a month in his newspaper. Once the gift enterprise forwarded a prize, the editor promised that ‘the week after its reception the “prize” will be noticed editorially.’34 Henry Catlin, the editor of the True American, an abolitionist paper published in Erie, Pennsylvania, was rather less sanguine, detailing a compounding editorial commitment that threatened to sink his own integrity: ‘The last of January you sent me one pencil and pen, and I inserted your advertisement. You wrote me that if I would give you a puff you would draw me one of your prizes in payment.’ Catlin did this, penning a ‘lengthy notice stating unequivocally that I knew [C.E. Todd & Co.] were reliable.’ Yet after mailing copies of these notices and letters to follow up on the prize, Catlin had been ignored. ‘Now how is this?’ he exclaimed, ‘am I to pass for a liar in the community by recommending parties that fail in their engagements? Must I be compelled to retract all that I have said, and warn the public against you?’35 The public here serves as leverage to gain the promised puff prize, as well as an untapped market to which access is controlled by editorial key. If editors in distant towns traded on their position to wheedle prizes and money from dubious city schemes, gift enterprise operators recognised and utilised the authority of these local editors—often an individual well known in the community—to provide a patina of legitimacy to their business.

While there is no extant evidence that G.G. or D.W. Evans engaged in this practice of presents for puffs, it is entirely probable. A number of editorial endorsements praise the integrity and honesty of the ‘Great Gift Bookstore’. An April 1859 reprinted column in the Weekly Wisconsin Patriot attests that in G.G. Evans ‘we find an enterprising man—the originator of a business which he has followed with the greatest energy and strictest integrity.’ To counter ‘unmerited censure’, the long column highlights his gift-enterprise’s encouragement of authors and publishers, his contribution to manufacturers and employment, and the intellectual benefits of his books to readers. ‘The fairness and honesty of the business,’ the article attests, ‘is not to be doubted.’36 The Trenton State Gazette was a bit more circumspect and ostensibly neutral. Of G.G. Evans’ Gift Book Enterprise, the paper proclaims to know ‘little or nothing about the principle upon which these “enterprises” are conducted, and hence are not prepared to recommend or condemn them.’ But just after this hedge, a sly wink: ‘We may say, however, that if, in addition to getting books at regular prices, one can get a “gift” for nothing, we can see no possible objection to it—especially if the “gift” happens to be a gold watch.’37 One wonders if the editor of the Gazette was admiring his own new timepiece.

Alongside leveraging editorial authority, the Evans’ capitalised on the widespread practice of reprinting in mid-nineteenth American periodical print culture. Editors regularly copied poetry, fiction, local news, and reviews from other papers, sometimes with authorial or source attribution, but more often not. As scholars such as Meredith McGill and Ryan Cordell have shown, this ‘culture of reprinting’ was maintained by a complex web of regional and transatlantic interpersonal, kin, and business relationships among editors in a decentralised print system.38 Readers in Tennessee might read—knowingly or not—the same poems or editorials as a reader in New Hampshire. As a bookseller, Evans employed this print practice to shape a recognisably national reputation. In May 1859, a two-paragraph news item appeared in the Weekly Wisconsin Patriot published in Madison recommending Mr. Evans’ ‘Great Gift Book Store.’ The final paragraph certified,

We have dealt with Mr. Evans for years, personally, and conversed with scores of others who have sent him their money and orders, and received Book and valuable Gifts in return [. . .] and in no single instance have we ever heard the first word of dissatisfaction expressed.39

Yet these were not the words of the Patriot; the news item is introduced with the attribution ‘From the Columbia Democrat, an old and well established journal.’ The Columbia Democrat probably refers to the Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania’s Columbia Democrat and Bloomsburg General Advertiser, founded in 1837 as the Columbia Democrat and renamed in 1850. Most of these two paragraphs, including the quoted endorsement, was then reprinted in The Weekly Georgia Telegraph in Macon, Georgia in June that year, where the heading attributed the paragraphs—here, longer with more on George Evans’ biography—to the Philadelphia Inquirer, ‘a newspaper which has stood in the foremost rank of public journals in the United States for over sixty years.’40 Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Georgia—and most likely places in between. Additional reprinted items appearing in country newspapers attribute original publication to periodicals in cities and towns in Alabama, New Orleans, Illinois, Rhode Island, New York, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Minnesota (‘not yet a State’), among others, even venturing internationally to Canada. Evans drew not only on the local influence of editors, but also on the perceived authority of the medium of the press and its expansive networks of printing and circulation.41

In an additional effort to engage the authority and marketing potential of the newspaper, G.G. Evans created his own paper. Joining other large publishers of the time, like Harper & Brothers and G. P. Putnam & Co., who issued their own periodicals in an effort to support house publications, G. G. Evans published the Geo. G. Evans’ Illustrated Times in March, 1860.42 This first, and apparently only, issue includes in its eight pages poetry, biographies of prominent Americans, jokes and sketches, and a multiple-page illustrated article on Montreal’s Victoria Bridge, intercut with Evans’ own remarks about his gift-book business, endorsements, and large woodcuts of his Philadelphia store. Considered together, these contents engage in an effort to convert readers to customers and customers to readers. By this time, G.G. Evans had expanded his bookselling business from retail and wholesale to publishing. He published popular romance and adventure novels, biographies of prominent Americans, as well as high-selling etiquette guides and popular songbooks. He is perhaps best known as the publisher of prolific temperance author Timothy Shay (T.S.) Arthur and numerous editions of The Illustrated History of the United States Mint. Evans’ Illustrated Times paper served not only to advertise his publications and bookstore, but also to reinforce his personal credibility. A reprinted notice in the paper describes him as ‘the soul of generosity’ for a thousand-dollar donation benefitting workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts affected by a tragic mill collapse and fire. ‘[B]ecause he had himself in early life, worked in a Massachusetts cotton mill,’ the note explained, ‘he desired to help those who had suffered while engaged in a similar occupation.’43 In shaping his personal biography as a trustworthy and benevolent individual, he was also, of course, shaping his business brand as trustworthy and benevolent.

In fact, by this time in 1860, George G. Evans was also working to distinguish his name and brand from that of his brother. In April 1858, G.G. Evans announced his ‘Great Gift Book store’ on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, where he would permanently settle. A few months before in late August 1857, an ad for the New York Evans & Co. gift-book store listed only D.W. Evans and a partner, J.H. Preston, as proprietors.44 Whatever the reason for the split, it soon turned hostile and the brothers battled it out—where else?—in the newspapers. In an April 1859 issue of the Rockland County Journal in New York—repeated in other journals in New York and as far away as San Antonio, Texas—Daniel Evans corrects the name Evans & Co. to D.W. Evans & Co. ‘to prevent all confusion in the future.’ He explains ‘many have taken the advantage of our popularity to advertise under the same name as originators, to increase their trade’ and his firm has ‘no connection with any other Gift Book House.’45 Readers may have noticed G.G. Evans’ own separate advertisement on the same page. Brother George responded in the Lowell Daily Citizen and News a couple months later denouncing the New York Evans & Co. as deceitful imitators ‘indebted to me not only for their first idea of conducting the business, but for stock to commence with and a place to commence in.’ He did not go so far as to claim outright fraud by these supposed imposters; rather, that they are guilty of ‘deceptive advertising’ in claiming to be the ‘Oldest in the business’ when it was he, George G. Evans, ‘the Originator of the Gift Book Enterprise in the United States—who established it and brought it to its present high position, by constant labor, unwearied application, and large expenditure of money.’46 Other advertisements in country papers reiterate G.G. Evans’ disassociation with ‘New York Gift Stores,’ a near-transparent reference to Evans & Co. of New York City.47

Both Evans’ brothers, and G.G. Evans in particular, leveraged the expanding reach of the mid-nineteenth century press, its editorial and printing practices, and the very form of the newspaper itself in order to market themselves and their bookstores. Pioneering an aggressive form of advertising previously unknown in the book world, the bookstores of the Evans brothers are indissociable from larger networks of print. This extensive print and mail network, integral to the Evans’ business, unravelled with the declaration of civil war in April 1861. The lucrative southern market was practically severed. In 1861, G.G. Evans shifted his business into premiums, advertising a ‘new enterprise’ with the promise ‘Hard Times Made Easy; Good News for the Unemployed.’ He mentions a premium catalogue, but no books.48 For his part, D.W. Evans, who had renamed his New York establishment the ‘Pioneer Gift Book Store’ added a similar header to his gift-bookstore ads: ‘Now! When Times are Hard!!’ is the time to buy books asserts an April 1861 advertisement.49 The gift-book enterprise of D.W. Evans disappears from the public record after that. G.G. Evans briefly reappears as a gift-bookseller in March 1863, and in December 1865, some seven months after the official end of the Civil War, he announced the ‘reopening of the G.G. Evans Gift Book Store.’50 It is unclear how long his renewed business lasts, though he does trumpet the firm’s longevity in an 1880 advertisement for the ‘Philadelphia Premium Book Company’ that begins, ‘A quarter of a century ago…’51

Catalogue Communities

If newspapers gave the Evans’ a medium for capitalising on the contentious cultural dynamics of gambling to market their bookstore’s incentive sales model and build their own credibility as entrepreneurial booksellers, the printed book catalogue smoothed the rough edges of controversy. Newspapers may have helped the Evans’ build their bookstore; the catalogue helped them populate the bookstore. More than a list of books, readers would find within the pages of the Evans’ catalogues imaginary readers buying books and winning prizes, actual watch-winners in towns near and far, as well as opportunities to engage in their own bookselling. As they were delivered along post roads and in towns newly accessible through rail, Evans’ catalogues created and consolidated imagined and real communities of book buyers and book readers.

The catalogues themselves are a miscellany of content and forms. Ranging in length from twelve to seventy-two pages, with most falling near fifty pages, the catalogues open with a lengthy manifesto-like introduction from D.W. or G.G. Evans, detailing the business model of the bookstore and its philosophy of books and reading. Echoing the diverse content of nineteenth-century magazines, the catalogues include letters from readers and customers, poems and imaginative prose advertising the Evans’ store, reprinted newspaper articles endorsing the gift-book store, recommendations and letters from previous customers, and a list of prominent publisher endorsements. In addition to the conventional list of books for sale, catalogue readers would also find directions for mail orders, a commission plan for agents, and a list, often several pages long, of possible gifts.52

More than immersive advertising—though it is that—the diverse contents of Evans’ catalogues work to create and shape a sense of book buying and book reading community. This community-building begins with the front and back covers of the catalogue. Engravings of the New York or Philadelphia stores—the front façade on the front cover of the catalogue and the store interior on the back cover—first connect distant catalogue readers as potential customers. The image of the storefront from the perspective of the street figuratively invites the catalogue reader into the bookstore, making explicit the link between the physical bookstore and the catalogue as a print stand-in for the store. Readers holding the 1858 catalogue for ‘The Original Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Establishment’ in New York, for instance, would initially note the monumental architecture of the building and the busy surrounding street life asserting the bookstore’s prosperity [Figure 1]. Genteelly-dressed men and women mingle by the front door and peer into the store through large windows on a bustling Broadway, much as the catalogue reader is about to turn the page for a look into Evans’ store.53 This image incorporates the removed catalogue reader into a larger consumer community. Technological advances in lithography in the 1840s and 50s allowed merchants to increasingly include images of their storefront and its interior in advertisements.54 Labelled ‘retail-scapes’ by historical Johanna Cohen, these store images bridge the space between scene and spectator and invite the viewer into the scene.55 A purchase from the store would purchase the viewer’s own place in the scene and in the larger consumer community.

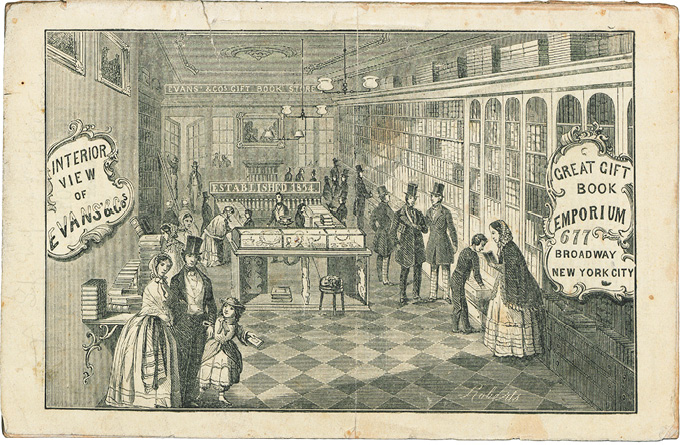

Entering the pages of the catalogue, then, is to be entering—if not the physical—then the figurative and ideological space of the bookstore. The engravings of the interior of the bookstore on the back covers of many of Evans’ catalogues extend the performative link between store and catalogue [Figure 2]. Long rows of books line the walls and are piled up to the ceiling, emphasising the scale and depth of the store; its respectable patrons browse the stock. To the right in the engraving closing the same 1858 New York catalogue, a woman reads, while a boy selects a book from a drawer behind her. A pair of men engage in some friendly literary sociability by the shelves, and a dozen others peruse the merchandise. Dominating the foreground, an eager young reader gestures with her new book while pulling her parents and, by extension, the viewer further into the store. Though the gift counter attracts conspicuously little attention from the customers, it is spotlighted for viewers in the centre forefront of the image. This dominant placement acts as a visual corollary for the pages-long list of potential prizes catalogue readers will encounter near the front of the catalogues.56

Figure 2

Though these pictorial frames for the catalogue are marketing strategies designed to encourage patronage and a degree of brand recognition and loyalty, they also model an array of consumer and social practices for book buying. Presenting a ‘geography of refinement’—to use historian Richard Bushman’s term—these images frame the bookstore with middle-class values of market engagement and prescribe specific models for behaviour when shopping for books.57 Most customers are solitary; the only social interactions are the two men in quiet conversation and the child ushering her family into the store. Those browsing the shelves and possibly sampling a book are dressed well, echoing the elegant built environment. The message: stepping into Evans’ gift-book store—or by extension, opening the pages of his catalogue—is to enter a refined, contemplative space for genteel reading practices.

Yet this vision of the bookstore and book buying sits uneasily beside the one actually offered inside the catalogue. In letters from customers, reprinted vignettes and poetry, and newspaper excerpts printed in the catalogues, an alternative vision of the bookstore community emerges. Here, rural farmers brush shoulders with young urbane couples, unaccompanied children browse and buy, crowds jostle and shout inside the store and throng the pavement outside, and everyone is enthralled with the gifts. A promotional poem printed in this same catalogue describes the scene:

And loud and long the laughter

As fortune’s game we thus did press

[. . .]

Watches, and cameo-drops, and rings

Flow round the room on glittering wings—

[. . .]

There ladies stood in rich attire

[. . .]

Here country farmers, all agape

At fortune in this novel shape,

[. . .]

A laugh ran round the merry throng,

Which frescoed beams re-echoed long,

In every gilded rafter:

While rippling jost, and whispering sigh,

And good Dame Fortune’s genial cry,

Renewed the brilliant laughter.58

This fluid, Barnumesque spectacle stages a motley book-buying public and a carnivalesque atmosphere. Emphasised in the two-column, full-page poem are both the communal euphoria associated with the awarded gifts as well as the specific book titles purchased by the diverse customers in the store. This inclusive vision seeks to incorporate a variety of reading publics—labourers and clerks, women and children, rural farmers and urban immigrants—into a book-buying and book-owning community. By both deploying and then disavowing the associations of the book with dearness and refined culture, the Evans’ catalogues open the gift-bookstore as a space for a diverse public and book buying as lively entertainment.

The catalogues are also invested in portraying how the gift-book phenomenon could reinforce local community and interpersonal relationships. In a fictional sketch printed in an 1858 catalogue for G.G. Evans’ Great Gift Bookstore in Philadelphia, a pressing crowd in Evans’ ‘far-famed’ store witnesses Mr. Covet approach the counter to purchase a ‘fashionable Annual’ with the expressed intention of receiving a ‘good present.’59 When he is rewarded with a lady’s neck chain, he is appalled, claiming scandalous thievery. While the clerk tries to assuage his anger by emphasising the value of the book he has just purchased, ‘Mrs. Venture’ sidles up to the desk and wins a gold watch with her purchase of the compilation One Thousand Anecdotes. Inspired by this luck, other customers make their purchases. We are introduced to a pair of sisters, whose prize of a gold locket becomes the occasion for one sister to declare her love for her fiancé: ‘How lucky! Just the thing in which to enclose my daguerreotype to Ch--.’ Another young boy and his sister purchase little books for their friends and vow to distribute their free gifts among their friends as well. Unlike the misguided and maligned ‘Mr. Covet’, customers express a spirit of generosity and the intention of using the prizes as gifts for others. In this reframing of the lottery gamble, instead of winnings being used for personal enrichment, the rhetoric of the gift invokes moral virtues of charity and generosity and begets more gifting, initiating a cycle designed to enrich the social good and consolidate community.

Alongside these imagined book buyers, Evans also included real customers in some catalogues in an effort to bridge the geographical distance of mail order sales. Included an 1859 catalogue for his Great Gift Bookstore in Philadelphia was an eight-page list entitled, ‘Names and Residences Of persons who have received Gold and Silver Watches as gifts for the year ending December 31st, 1859, at G.G. Evans’ Original Gift Book Store.’60 Divided first by gold then silver watches, the list is organised chronologically, giving the date, subscriber and subscriber’s location by city, county, and state. Over 500 entries are listed. This list draws on the print form of the directory, an informational genre that thrived in the mid-nineteenth century with the rapid expansion of urban centres and business concerns. The directory itself works to consolidate community, connecting unknown persons through their inclusion on the list and generating new relationships by name or address or profession. In Evans’ directory, the list is organised by the winning date, privileging consumer participation over region or class categories. As a marketing ploy, it offers the enticing possibility of seeing one’s own name listed and it mitigates concerns of fraud associated with a distant company that relied on sensation and the spectre of gambling. Importantly, the list also offers readers connective threads in a national network of book consumers. These connections spanned the developing nation: Dr. T.B. Moody, a leading citizen of the mill and frontier town of Gotton Gin Port, Mississippi; A.L. Sellers, merchant, postmaster, and son of the founder of tiny Sellersburg, Indiana; William Green and D.C. Goodlett, young twenty-somethings in Moulton, Alabama; Caroline Maynard of Providence, Pennsylvania, an English immigrant and thirty-nine year old wife to miner John Maynard and mother to five sons.61 Of course, readers in 1860 wouldn’t be this intimately connected, but they would see individuals listed from Camp Hudson and Waco, Texas, north to Wisconsin and over to Maine, and south to Georgia, with every state in between. They might see a winner in the neighbouring town. And by including full names, not simply the towns or states where watches were won, Evans not only establishes credibility and generates enthusiasm for his gift-book business, but also fosters a sense of shared community as readers of the catalogue and patrons of the gift-bookstore.62

For Evans’ gift-enterprise bookstore, community is capital. While the fictional anecdotes in the catalogue frame an inclusive bookstore space and the watch-winner list attempts to bridge geographic distance to consolidate a social network of book-buyers, the catalogues also deploy and reinforce actual community relationships by incentivising the formation of local book buying clubs. To form a club, informal agents would pool local book orders and receive added incentives for their labour. Book publishers had long used hired agents as the backbone of subscription sales, whereby the agent would canvass local towns with a sample or dummy book to gather subscriptions to fund publication of the book. In addition, periodical publishers used ‘clubs’ with incentive structures as a way to generate volume subscriptions. Evans & Co expands these models in new directions. Rather than official agents employed by publishers, the Evans’ deputise community members who might activate their networks for book orders. Some ads highlight expected professional actors—‘Country booksellers, postmasters, and all others whose business throws them much in contact with the reading public, are respectfully solicited to become our Agents.’63 Others move to broaden the possibilities for who might be successful agents: ‘and any individual, whether male or female, who may desire to act as Agents for us in getting up Clubs, are invited to do so.’64 One catalogue highlights the ease of forming a book buying club: ‘by showing it to a few friends a Club may be easily procured.’65 And the back cover of a Boston catalogue directly addresses the reader: ‘you are respectfully invited to act as our Agent in forming Clubs … If you cannot act yourself please show this to some friend who can.’66

While local media ecologies—the editorial endorsements, the reprinted testimonials and advertisements, and the circulating catalogues—helped grant the firm legitimacy, so too did these local community entrepreneurs acting as club organisers. Club organisers offered access to their own personal or professional networks, both using existing communities and creating new ones around a shared experience of books and prizes. In October 1859, D.W. Evans & Co. filled an order for ten books submitted by Miss Laura Deming of Wethersfield, Connecticut.67 The books ordered ranged from the domestic novel Married Not Mated: How They Lived at Woodside and Throckmorton Hall, published by Derby and Jackson, publishers with whom the Evans’ had a long-standing relationship, to the jokebook Mrs. Partington’s Carpet Bag of Fun to a biography of George Washington. The order invoice includes a handwritten list of club members’ names with their book title and prize code to aid the organiser in distributing the prizes. Census records reveal that Laura Deming was the 39-year-old wife of stonemason Erastus Deming, who is probably the E.B. Deming listed on the invoice who ordered a copy of the popular Frank Wildman’s Adventures on Land and Water.68 Sarah Kilby, who ordered the book Life of Christ, was Deming’s next-door neighbour. The nearby farming family of the Griswolds also joined the club. In Laura Deming’s club order list, we see how ties of family and proximity enabled local and micro-communities of book buying. In another order to G.G. Evans’ Great Gift Book Establishment in Philadelphia in November, 1859, G.R. Wells from Stone Mountain in DeKalb County, Georgia included additional members of his own family, as well as brothers William H. and G.W. Braswell from a nearby town in the same county, and the married R.M. Braden and his wife.69 It is likely that this is the same R.M. Braden who was postmaster of neighbouring Gwinnett County, Georgia.70 These clubs, which drew on geographical, professional, and kinship networks, circulated the print catalogue and generated book sales. In so doing, they also created a shared book buying and gift winning experience, one so riotously celebrated in the pages of the catalogue itself.

Conclusion

The success of the mid-century gift enterprise bookstores of D.W. and G.G. Evans can be located in a complex web of print forms and practices. As they built their gift-book empire through print, the Evans’ not only marketed their store in the advertising pages of newspapers, but also leveraged the feverish reporting columns on gift enterprises and lotteries to adjudicate debates about their sales model and exploited common reprinting practices and editorial authority to build professional and personal credibility. Equally important in this print blitz were their magazine-like book catalogues, in which book lists took second place to bookseller manifestos, creative prose and poems about their bookstore, letters from readers, and a dynamic cast of imagined and real customers. These catalogues acted as bookstores in print, recreating the spaces, books, and activities in a bookstore. Crucially, the catalogues utilised and facilitated distant imaginative and local physical community formation and engaged contemporary debates over, among other things, the cultural status of the book and the forms of connection in a rapidly expanding nation and consumer economy. Although book catalogues have traditionally been used in literary and book history as a functional genre to trace provenance or bibliographic data, a close study of the Evans’ catalogues reveal the untapped potential of this print form. When read as a discursive form—as a text in itself the book catalogue emerges as a vibrant and vital print genre that can offer insights into diverse literary and social contexts.

Gift enterprise bookstores in general, and those of G.G. and D.W. Evans in particular, also provide an opportunity to enlarge our understanding of the forms and practices of bookselling in America. While their liminal legal status and proximity to the ‘shadow economies’ of fraud and speculation have defined the frame of analysis for these stores, entirely dismissing gift-book enterprises from traditional examinations of book marketing limits the kinds of questions we ask about these stores and our larger understanding of the history of the book market in America. For example, we might ask about the Evans’ role in the rise of premium marketing in bookselling and draw a straight line from the Evans’ to today’s Scholastic Books catalogues with their profusion of non-book items. When members of a parent watchdog group complained in 2009 that Scholastic was using its book club ‘to push video games, jewellery kits, and toy cars,’ they echoed those nineteenth-century critiques of the gift enterprise bookstore in their concern that children would be persuaded ‘to choose books based not on the content but on what they get with it.’71 The president of Scholastic Book Clubs might have been channelling G.G. and D.W. Evans when he countered that no matter why they choose a book, for the book or its prize poster or stickers, the premium ‘helps kids engage’ in books and reading. Alternatively, we might ask how Evans catalogues reveal a larger scope of women’s involvement in the mid-nineteenth century book trades as booksellers and entrepreneurs. After all, offering women the opportunity for direct sales and commission earnings in the 1850s is a preliminary step in the emergence of women-driven multi-level marketing, which grew after the founding in 1886—notably, by a former bookseller—of the California Perfume Company, better known today as Avon.72 Taking seriously the gift-book enterprise in book history can illuminate these paths and others, enriching not only our understanding of the history of bookselling in America, but also the relationships between bookselling and other market and cultural dynamics.

Reference List

Arrest in New York of the Proprietor of a Gift Enterprise. The Barre Gazette 26 March 1858, p. 2.

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Stanford CA, Stanford University Press, 1998.

BUSHMAN, Richard. The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities. New York: Vintage Books, 1993. ISBN: 9780307761606.

COHEN, Joanna. Promoting Pleasure As Political Economy: The Transformation of American Advertising, 1800 to 1850. Winterthur Portfolio, 2014, vol 48, no 2–3, p. 163–190. ISSN: 0084–0416.

CORDELL, Ryan. Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers. American Literary History, 2015, vol 27, no 3, p. 417–445. https://doi.org/10.1093/alh/ajv028

Current Items. New York Ledger 13 March 1858, p. 4.

The Early Nineteenth-Century Newspa per Boom. The News Media and the Making of America, 1730–1865. American Antiquarian Society. Online Exhibition. https://americanantiquarian.org/earlyamericannewsmedia/

Dunbar Rowland, A-K.- v. 2. L-Z.- v. 3. Contemporary biography. Mississippi: Southern Historical Publishing Association, 1907.

D.W. Evans. The Pioneer Gift Book Store. D.W. Evans & Co. 677 Broadway, New York. [Oct 20] 18[59] M[iss] Laura Diming. New York, 1859. American Antiquarian Society, Ephemera Bill 0223.

Easton Gazette [MD] 25 May 1861, p. 3.

Enterprise in Business Exemplified. Macon Weekly Telegraph 28 June 1859, p. 1.

ERICKSON, Paul. Economies of Print in the Nineteenth-Century City. In LUSKEY, Brian P. and WOLOSON, Wendy (eds). Capitalism By Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, p. 190–214. DOI: 10.9783/9780812291025

EVANS, G.G. G.G. Evans’ Original Gift book store and Publishing house, no. 439 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia. Library Company of Philadelphia, AM 1859 Evans 12318.F (Woloson).

Evans & Co. The Original Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Establishment [catalogue]. New York, 1858. Winterthur Library and Museum.

Evans & Company. [Catalogue]. New York, ca. 1860. Winterthur Museum and Library.

FABIAN, Ann. Card Sharps and Bucket Shops: Gambling in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Routledge, 1999. ISBN: 9781138402447

G.G. Evans’ Great Gift Book Sale [Catalogue]. Philadelphia, 1858. Hagley Museum and Library.

G.G. Evans’ Great Gift Book Store [catalogue]. Philadelphia, 1859, p. 1–8. Winterthur Library.

G.G. Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Sale! Head Quarters for the Northern United States [catalogue]. Boston, 18--, p. 1.

G.G. Evans & Co. Great Gift Bookstore [catalogue]. Boston, ca. 1860. University of Delaware.

General Catalogue of Bowdoin College and the Medical School of Maine. 1912, p. 65.

Geo. G. Evans’ Illustrated Times. Vol 1, issue 1, Philadelphia: March 1860.

Gift Book Enterprise. Trenton State Gazette 7 April 1858, p. 3.

Gift Enterprises. History and Mystery of Swindles and Swindlers. Pomeroy’s Democrat 10 November 1869, p. 3.

GREENSPAN, Ezra. George Palmer Putnam: Representative American Author. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2000. ISBN: 9780271020051

GROVES, Jeffrey D. Periodicals and Serial Publication: Introduction. In CASPER, Scott E., GROVES, Jeffrey D., NISSENBAUM, Stephen W., and WINSHIP, Michael P. (eds.). A History of the Book in America. Vol 3: The Industrial Book, 1840–1880. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007, p. 224–230. ISBN: 9780807830857.

Harper’s Weekly, 29 August 1857, p. 560.

HENKIN, David. City Reading, Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998. ISBN: 9780231107457.

HENKIN, David. The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN: 9780226327228.

History of the Ohio Falls Cities and Their Counties. Clark County, in: L. A. Williams & Company, 1882.

JOHN, Richard R. Spreading the News: The American Postal System From Franklin to Morse. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN: 9780674833425.

Lineage Book, Daughters of the American Revolution. Vol 37, The Society, 1913.

Lowell Daily Citizen and News 27 June 1859, p. 3.

LUSKEY, Brian P. and WOLOSON, Wendy (eds). Capitalism By Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, p. 190–214.

MANKO, Katina. Ding Dong! Avon Calling!: The Women and Men of Avon Products, Incorporated. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2021.

MAUSS, Marcel. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, London, Routledge Classics, 2002 [1925].

MCGILL, Meredith. American Literature and The Culture of Reprinting, 1834–1853. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. ISBN: 9780812209747

New York Herald 8 June 1856, p. 5.

Official Register of the United States: Containing a List of Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1862.

Philadelphia Inquirer 15 December 1865, p. 8.

Philadelphia Inquirer 3 January 1880, p. 5.

R.G. Dun & Co. credit report volumes. Baker Library, Harvard Business School. New York, Vol 193.

Rockland County Journal 23 April 1859, p. 3.

RICH, Motoko. Scholastic Accused of Misusing Book Clubs. New York Times, Feb 9, 2009. Accessed through Internet: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/10/books/10scho.html

‘State v. Clarke,’ Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Judicial Court of New Hampshire, Volume 33. (G. Parker Lyon), 1873.

SWEENEY, Matthew. The Lottery Wars: Long Odds, Fast Money, and the Battle Over an American Institution. New York: Bloomsbury, 2009. ISBN: 9781596913042.

The Book Trade. Weekly Wisconsin Patriot 30 April 1859, p. 3.

The Farmer’s Cabinet 18 May 1859, p. 3

The Gaming Spirit. New York Ledger 29 May 1858, p. 4.

The Gift Enterprise Mania. The Pittsfield Sun 29 November 1855, p. 2.

The Legitimate Gift Enterprise Defended, Evans & Co. in Reply to a Libellous Weekly. New York Herald 28 March 1858, p. 5.

The Lottery Mania. New York Herald 20 March 1858, p. 1.

The Swindlers of New York. New York Herald 15 April 1858, p. 6.

The Ohio State Journal 21 April 1858, p. 4

TUCHER, Andie. Newspapers and Periodicals. In GROSS, Robert A. and KELLEY, Mary K. (eds.). A History of the Book in America. Vol 2: An Extensive Republic: Print Culture and Society in the New Nation, 1790–1840. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010, p. 389–408. ISBN: 9780807833391.

United States Federal Census, 1860, Wethersfield, Hartford, Connecticut. Roll M653_77; p. 39.

VALLANDIGHAM, Edward N. Lotteries in the United States. The Chautauquan: a weekly newsmagazine, 1890, vol 10 p. 689–693.

WOLOSON, Wendy. Wishful Thinking: Retail Premiums in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America. Enterprise & Society, December 2012, vol 13, no 4, p. 790–831. ISSN: 1467-2227.

WOLOSON, Wendy. Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

1 New York Herald 8 June 1856, p. 5. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers. The ‘gift book’ of the gift book enterprise is distinct from the popular antebellum genre of the gift book or literary annual which were specialised mass-produced literary anthologies or miscellanies that compiled poems, prose and engravings into an attractively bound volume designed for gift-giving.

2 The Gift Enterprise Mania. The Pittsfield Sun 29 November 1855, p. 2. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

3 WOLOSON, Wendy. Wishful Thinking: Retail Premiums in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America. Enterprise & Society, December 2012, vol 13, no 4, p. 790–831.

4 Evans & Co. The Original Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Establishment [catalogue]. New York, 1858, p. 2. Winterthur Library and Museum.

5 Ibid.

6 The Swindlers of New York. New York Herald 15 April 1858, p. 6. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

7 Evans & Company. [Catalogue]. New York, ca. 1860, p. 60. Winterthur Museum and Library. This catalogue was probably published in 1856, based on the company name and address. The Herald ‘endorsement’ was published in additional catalogues as well.

8 Current Items. New York Ledger 13 March 1858, p. 4. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers. In May of that year, The Ledger published a brief paragraph condemning the gift book enterprise not only for encouraging a ‘gaming spirit’, but for decking people out in false jewelry, which fostered ‘a spirit of display among those who can not afford to indulge it legitimately.’ See The Gaming Spirit. New York Ledger 29 May 1858, p. 4.

9 The Legitimate Gift Enterprise Defended, Evans & Co. in Reply to a Libellous Weekly. New York Herald 28 March 1858, p. 5. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

10 WOLOSON, Wendy. Wishful Thinking, p. 790–831; WOLOSON, Wendy. Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020, especially Chapter 5; LUSKEY, Brian P. and WOLOSON, Wendy (eds). Capitalism By Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, p. 190–214.

11 ERICKSON, Paul. Economies of Print in the Nineteenth-Century City. In LUSKEY, Brian P. and WOLOSON, Wendy (eds). Capitalism By Gaslight: Illuminating the Economy of Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, p. 190–214, 192. Although Erickson’s chapter does not specifically mention gift-book enterprises and his larger point is to highlight the multifaceted and overlapping capitalist practices occurring under the umbrella term ‘print trade’, I take seriously this assertion of the value of examining the less ‘respectable’ aspects of the trade alongside traditional subjects.

12 Genealogical research conducted in online database Ancestry.com. Specific documents consulted include Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates Index, 1803–1915; United States Federal Census, 1850, Brighton, Somerset, Maine. Roll M432_269, p. 233A, Image 452; United States Federal Census, 1860, New York Ward 15 District 1, New York, New York. Roll M653_805, p. 629, Image 609.

13 Lineage Book, Daughters of the American Revolution. Vol 37, The Society, 1913, p. 228; General Catalogue of Bowdoin College and the Medical School of Maine. 1912, p. 65. Accessed through Ancestry.com. G.G. Evans would later claim these distinguished kin in biographical descriptions associated with his gift-book store.

14 Enterprise in Business Exemplified. Macon Weekly Telegraph 28 June 1859, p. 1. The 1853 Lowell city directory lists George G. and Daniel W. Evans working as a sashmaker and in the carpet mills, respectively. They both appear first in the 1856 New York City directory with the occupation of “books.”

15 New York Herald 8 June 1856, p. 5. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

16 R.G. Dun & Co. credit report volumes. Baker Library, Harvard Business School. New York, Vol. 193, p. 646.

17 GROVES, Jeffrey D. Periodicals and Serial Publication: Introduction. In CASPER, Scott E., GROVES, Jeffrey D., NISSENBAUM, Stephen W., and WINSHIP, Michael P. (eds.). A History of the Book in America. Vol 3: The Industrial Book, 1840–1880. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007, p. 224-230.

18 The Early Nineteenth-Century Newspaper Boom. The News Media and the Making of America, 1730-1865. American Antiquarian Society. Online Exhibition. https://americanantiquarian.org/earlyamericannewsmedia/

19 TUCHER, Andie. Newspapers and Periodicals. In GROSS, Robert A. and KELLEY, Mary K. (eds.). A History of the Book in America. Vol 2: An Extensive Republic: Print Culture and Society in the New Nation, 1790–1840. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010, p. 389-408; JOHN, Richard R. Spreading the News: The American Postal System From Franklin to Morse. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

20 The Farmer’s Cabinet 18 May 1859, p. 3; Enterprise in Business Exemplified. Macon Weekly Telegraph 28 June 1859, p. 1; The Ohio State Journal 21 April 1858, p. 4; The Book Trade. Weekly Wisconsin Patriot 30 April 1859, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

21 Geo. G. Evans’ Illustrated Times. Vol 1, issue 1, Philadelphia: March 1860, p. 6.

22 SWEENEY, Matthew. The Lottery Wars: Long Odds, Fast Money, and the Battle Over an American Institution. New York: Bloomsbury, 2009; FABIAN, Ann. Card Sharps and Bucket Shops: Gambling in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Routledge, 1999, p. 108–118.

23 VALLANDIGHAM, Edward N. Lotteries in the United States. The Chautauquan: a weekly newsmagazine, 1890, vol 10, p. 689–693.

24 Gift Enterprises. History and Mystery of Swindles and Swindlers. Pomeroy’s Democrat 10 November 1869, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

25 Vallandigham, 691.

26 Names and locations compiled from New York City directory listings.

27 There is much more to say here, although outside the scope of this article, on the role of books as objects of commodity exchange when, within the context of the gift enterprise, they act largely as tickets in a lottery. An 1855 New Hampshire court case found the proprietors of a gift-book enterprise guilty of engaging in a lottery because the gift sale ‘appealed to the same disposition for engaging in hazards and chances with the hope that luck and good fortune may give a great return for a small outlay.’ The speculative engagement of the book buyer, in other words, trumps his market engagement. He’s not buying a book; he’s buying a chance. This case raises fascinating questions about the (im)proper value of books and appropriate venues for their sale. See ‘State v. Clarke,’ Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Judicial Court of New Hampshire, Volume 33 (G. Parker Lyon, 1873), 329–336. In addition, another lens might examine gift theory and the ways in which the rhetoric of the gift associated with the gift enterprise negotiates cultural value and forms of social exchange. See MAUSS, Marcel. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, London, Routledge Classics, 2002 [1925]; BOURDIEU, Pierre. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Stanford CA, Stanford University Press, 1998.

28 Harper’s Weekly, 29 August 1857, p. 560. Access through HarpWeek.

29 See, for instance, advertisement in The Constitution [Middletown, CT] 13 July 1859, p. 3 and ‘Enterprise in Business Exemplified’, Macon Weekly Telegraph 28 June 1859, p 1. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

30 HENKIN, David. The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006, p. 2–3. See also JOHN, Richard R. Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

31 Henkin, p. 63–90.

32 Gift Enterprises. History and Mystery of Swindles and Swindlers. Pomeroy’s Democrat 10 November 1869, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

33 Arrest in New York of the Proprietor of a Gift Enterprise. The Barre Gazette 26 March 1858, p. 2; The Lottery Mania. New York Herald 20 March 1858, p. 1. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

34 Arrest in New York of the Proprietor of a Gift Enterprise, p. 2.

35 The Lottery Mania. New York Herald 20 March 1858, p. 1. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

36 The Book Trade. Weekly Wisconsin Patriot, 30 April 1859, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

37 Gift Book Enterprise. Trenton State Gazette 7 April 1858, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

38 MCGILL, Meredith. American Literature and The Culture of Reprinting, 1834-1853. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013; CORDELL, Ryan. Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers. American Literary History, 2015, vol 27, no 3, p. 417–45.

39 Great Gift Book Store. Weekly Wisconsin Patriot 7 May 1859, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

40 Enterprise in Business Exemplified, 1.

41 Some of these reprinted testimonials, whether penned by editors or Evans himself, also reappeared in his own book catalogues (the example of which inflamed The New York Herald), completing an integrated marketing feedback loop. Fellow New York gift-bookseller J. A. Andrews took a veiled jab at these tactics in his own classified ad in an 1867 issue of Harper’s Weekly, stating that ‘we do not believe it to be good policy to pay for an advertisement, and then copy it into our circular as the “opinions of the press.”’ Harper’s Weekly 19 September 1857, p. 608. Access through HarpWeek.

42 GREENSPAN, Ezra. George Palmer Putnam: Representative American Author. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2000, p. 285-–322.

43 Geo. G. Evans’ Illustrated Times, March 1860.

44 Harper’s Weekly 29 August c1857, p. 560. Access through HARPWeek.

45 Rockland County Journal 23 April 1859, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

46 Lowell Daily Citizen and News 27 June 1859, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

47 See, for instance, The Constitution [Middletown, CT] 13 July 1859, p. 3.

48 Easton Gazette [MD] 25 May 1861, p. 3. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

49 Harper’s Weekly 20 April 1861, p. 256. Access through HarpWeek.

50 Philadelphia Inquirer 15 December 1865, p. 8. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers. The 6 May 1862 issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer advertises ‘G.W. Pitcher’s Gift Book Store, formerly G.G. Evans.’ By March 1863, G.G. had reopened his ‘Original Gift Book Emporium, and an Inquirer ad indicates G.W. Pitcher had opened his own independent bookstore a few blocks away on Chestnut Street—no mention of gifts (11 March 1863). The 1865 re-opening also mentions a partner, Frank Bayley, as proprietor.

51 Philadelphia Inquirer 3 January 1880, p. 5. Access through America’s Historical Newspapers.

52 Extant book catalogues for the Evans’ bookstores are located in several archives, including the Library Company of Philadelphia, Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library, The University of Delaware Library, Hagley Museum and Library, and the Grolier Club.

53 Evans & Co. The Original Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Establishment [catalogue]. New York, 1858, p. 2. Winterthur Library and Museum.

54 HENKIN, David. City Reading, Written Words and Public Spaces in Antebellum New York. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 95–97.

55 COHEN, Joanna. Promoting Pleasure As Political Economy: The Transformation of American Advertising, 1800 to 1850. Winterthur Portfolio, 2014, vol 48, no 2–3, p. 163–90.

56 Evans & Co. The Original Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Establishment, p. 2.

57 BUSHMAN, Richard. The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities. New York: Vintage Books, 1993, p. 379.

58 Evans & Co. The Original Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Establishment, p. 57.

59 G.G. Evans’ Great Gift Book Sale [Catalogue]. Philadelphia, 1858. Hagley Museum and Library.

60 G.G. Evans’ Great Gift Book Store [catalogue]. Philadelphia, 1859, p. 1–8. Winterthur Library.

61 In addition to census records from 1850 and 1860 accessed through Ancestry.com, individuals were identified in Dunbar Rowland, A-K.- v. 2. L-Z.- v. 3. Contemporary biography. Mississippi: Southern Historical Publishing Association, 1907. Accessed through Google Books; History of the Ohio Falls Cities and Their Counties. Clark County, IN: L. A. Williams & Company, 1882. Accessed through Google Books.

62 The idea of building community in and through print is foundational to Benedict Anderson’s and Jürgen Habermas’ work.

63 Evans & Co. The Original Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Establishment, p. 53.

64 G.G. Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Sale! Head Quarters for the Northern United States [catalogue]. Boston, 18--, p. 1. University of Delaware.

65 G.G. Evans & Co. Great Gift Bookstore [catalogue]. Boston, ca. 1860. University of Delaware.

66 G.G. Evans & Co.’s Great Gift Book Sale! Head Quarters for the Northern United States [catalogue], p. 11.

67 D.W. Evans. The Pioneer Gift Book Store. D.W. Evans & Co. 677 Broadway, New York. [Oct 20] 18[59] M[iss] Laura Diming. New York, 1859. American Antiquarian Society, Ephemera Bill 0223.

68 United States Federal Census, 1860, Wethersfield, Hartford, Connecticut. Roll M653_77; p. 39; Accessed through Ancestry.com.

69 G.G. Evans, G.G. Evans’ Original Gift book store and Publishing house, no. 439 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia. Library Company of Philadelphia, AM 1859 Evans 12318.F (Woloson).

70 Official Register of the United States: Containing a List of Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1862, p. 199. Accessed through Google Books.

71 RICH, Motoko. Scholastic Accused of Misusing Book Clubs. New York Times 9 February 2009. Accessed through New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/10/books/10scho.html

72 MANKO, Katina. Ding Dong! Avon Calling!: The Women and Men of Avon Products, Incorporated. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2021.