Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2022, vol. 78, pp. 194–224 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2022.78.112

The Benefits and Limitations of Digital Tools to Retrieve the Emotions of Nineteenth-Century Readers of Philosophy from Manuscript Letters

Brigitte Ouvry-Vial

Le Mans Université & Institut Universitaire de France

Avenue Olivier Messiaen, 72085, 3LAM, EA 4335, LE MANS cedex 9, FRANCE

E-mail : brigitte.ouvry-vial@univ-lemans.fr

Nathalie Richard

Le Mans Université & TEMOS CNRS UMR 9016

Avenue Olivier Messiaen, 72085, LE MANS cedex 9, FRANCE

E-mail : nathalie.richard@univ-lemans.fr

Summary. This article discusses the limitations and benefits of resorting to digital tools and research methodology to explore nineteenth-century manuscript letters, written by readers to the French philosopher Victor Cousin, and to increase our understanding of how ordinary readers responded to philosophy at the time. More broadly, it examines the potential assets of the annotation interface developed in the Reading Europe Advance Data Investigation Tool (READ-IT https://readit-project.eu/ 2018–2021), a collaborative research project focusing on regenerating lost connections about the cultural heritage of reading from large volumes of highly-diverse eighteenth- to twenty-first-century sources in multiple languages. The case study describes challenges raised by attempts to detect and classify differences between female and male philosophical reading experiences as well as emotional responses, something which is largely under-explored. Along the way it provides reflexive as well as epistemological insights into the promises of big data for research on cultural history and literary archives and the current state of knowledge on emotions.

Keywords: History of reading; History of emotions; History of philosophy; Victor Cousin; gender and philosophy; Cultural heritage research; ontology databases.

Skaitmeninių įrankių privalumai ir trūkumai siekiant rankraštiniuose laiškuose atkurti XIX amžiaus filosofijos skaitytojų emocijas

Santrauka. Šiame straipsnyje aptariami skaitmeninių įrankių ir tyrimo metodologijos trūkumai ir pranašumai tyrinėjant XIX amžiaus rankraštinius laiškus, kuriuos skaitytojai rašė prancūzų filosofui Victorui Cousinui, bei siekiant geriau suprasti paprastų skaitytojų reakciją į tuometę filosofiją. Kalbant plačiau, straipsnyje nagrinėjami potencialūs anotacijų sąsajos privalumai, atskleisti bendrame mokslinių tyrimų projekte „Reading Europe Advance Data Investigation Tool“ (READ-IT https://readit-project.eu/, 2018–2021 m.), kuriame pagrindinis dėmesys skiriamas atkurti prarastus ryšius apie skaitymo kultūros paveldą iš daugybės labai įvairių XVIII–XXI amžių šaltinių, skelbiamų keliomis kalbomis. Atvejo tyrime aprašomi iššūkiai, kylantys dėl bandymų aptikti ir tam tikrai kategorijai priskirti skirtumus tarp moterų ir vyrų filosofinio skaitymo patirties bei emocinių reakcijų, o tai iš esmės yra nepakankamai ištirta sritis. Be to, straipsnyje pateikiama refleksyvių ir epistemologinių įžvalgų apie didžiųjų duomenų teikiamas viltis kultūros istorijos ir literatūros archyvų tyrimams bei dabartinę žinių apie emocijas būklę.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: skaitymo istorija, emocijų istorija, filosofijos istorija, Victoras Cousinas, lytis ir filosofija, kultūros paveldo tyrimai, ontologijos duomenų bazės.

Received: 2021 11 07. Accepted: 2022 03 17

Copyright © 2022 Brigitte Ouvry-Vial, Nathalie Richard. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

This essay evaluates the advantages of newly developed Information and Communications Tools and Digital Humanities methods to analyse heterogeneous nineteenth-century manuscript letters from readers, in order to understand how educated readers of all sorts responded to philosophy at the time. More specifically, it investigates whether we can observe differences between men’s and women’s reading experiences, emotions and judgments. The case study combines results from the Reading Europe Advanced Data Investigation Tool (https://readit-project.eu) with a distant and close reading of manuscript letters written by nineteenth-century men and women readers selected from the correspondence (5000 letters) of the French philosopher Victor Cousin (1792-1867). As both reading emotions as well as gendered reading are largely under-explored topics that require the analysis of large amounts of data, a digitally-inflected approach to our corpus seemed fitting, albeit ambitious. This article will thus describe the scientific context of the study within the emerging field of interdisciplinary emotion research, then some of its successive technical as well as hermeneutical steps, leading us eventually to evaluate the outcomes of such a methodology.

A previous article summing up the READ-IT contribution to regenerating lost connections about the cultural heritage of reading1 stated that 40 years of scholarship on written culture have provided a good understanding of what people read in the past until today and established the act of reading as a dynamic interaction between text and reader. But while striking changes affect formats, content, modes of reading today, questions remain unanswered about the pleasure of reading: Why do people read, what need or interest does it answer? How do they read, which faculties, senses are being triggered? Deep-seated reasons explain such persisting aporias in the state of our knowledge: reading is a mental activity that is hard to record.2 It appears as a multifaceted reaction to multiple stimuli, partially related to the object and content read and partially to the personal dispositions of readers. But identifying its salient features is challenging. Analysing the kaleidoscope of subjective reader-responses requires merging feelings, judgments and aesthetic emotions within a new definition of emotion, a potential cornerstone in the understanding of recreational or leisure reading, hence one that remains to be explored.3

A scattered knowledge domain

The study of readers’ emotions has today been made possible by the independent findings of distinct research domains - along with their related knowledge technologies. All potentially combine to enable a mixed approach, qualitative and quantitative, digital and traditional, to aesthetic emotions4 displayed in multiple languages, using both historical as well as contemporary resources. Although our case study is embryonic within ‘historical and digital emotion research’ as a whole, it draws on several recently developed interdisciplinary methodologies5. Therefore, it is worth highlighting the research strands - namely cultural history, cognitive studies and computational linguistics - that, in the wake of humanities-based engagement with information technology, converge and take from heterogeneous verbal (oral or written) reports6 an understanding of past and present, literary and intellectual reading experiences. The study of reading as an enlightening inner experience and the means of personal truth-seeking was first triggered, at least in France, by Barthes’ and Foucault’s seminal claims about the death of the author and the pleasure of the text7 that induced a paradigm shift in individual reading behaviour. It led to a critical revival of landmark essays by pivotal literary figures8 which first outlined the twofold perceptive-creative operation of reading. Meanwhile and coincidentally, the critically important work by reader-response theorists9 generated a shift towards a reader-centered aesthetics of literature and demonstrated that the changeable nature of individual reading affects the meaning of the text. At the same time, book historians10, along with other foundational scholarship using bibliographical, anthropological and sociological approaches11 to reading, paved the way for a vast array of studies focusing on changing modes of reading after the advent of silent reading12 and the nineteenth-century rise of a mass reading culture13, on modern national reading cultures and new reading publics among the working classes, women14 and youth. The digital revolution of the book and its startling transformations in the types of texts written, its medium, modes of appropriation and mutations in the literary sphere generated pluri-disciplinary interest in paper or screen reading, thus strengthening the evolution of research far beyond the area of book or print culture. Scholarship has thus shifted from specific historical contexts, communities and belief systems to ‘reading in the brain’ and to subjective reading15 seen as crucial to shaping empathy, facets of identity and social standing. Research covers the everlasting desire for bookish reading, its generic effects on empathy and emotional skills16, the motivational aspects of digital reading and its renewal on social media platforms. Approaches to haptic reading or to listening versus reading17 try to pinpoint the mixed impact of reading on our combined imaginations, intellects and emotions. The exploration of the ‘oceanic’ reading brain18 by scholars from cognitive and affective sciences pursue the purported danger of online reading for our faculties and lead to attempts at neuro-cognitive models of literary reading.19 This change of focus is sustained by recent access to digitised archives about the cultural heritage and contemporary practices of reading along with the development of oral history projects.20 Cumulatively the latter provide new evidence and databases about reading in the twentieth- and twenty-first-centuries. They also support novel explorations of highbrow reading by literary figures or of massive and previously unknown accounts by middlebrow, ordinary readers. Likewise, researchers engage in methodological debates in the fast growing field of cross-disciplinary emotion research.21 Contributions to a ‘global’ history of sensibilities convey theoretical scaffolding for understanding the evolution of cultural emotions, yet definitions remain unsettled and approaches are still heterogeneous.22 Finally, it is important to mention that despite intensive research in cognitive linguistics about the relation between language and emotion, much remains unknown, ‘for example, in relation to the distinctive and shared patterns among languages, the degree in which culturally salient facets shape emotive concepts, or how emotive terms relate to each other.’23 As Digital Humanities provide the means for exploring large archival sources much of emotion research is now supported by computational analysis of text, sentiment analysis, information extraction and emotion retrieval. There are different approaches and it would take too long to describe them all here. Let’s say that while sentiment analysis is now widely used to study affective states and subjective information, mining readers’ testimonies and perceptions for their emotional states challenges basic classifications of positive/negative, objective/subjective polarities. It indeed requires some methods built on Natural Language Processing and event detection in order to understand how people perceive the text they are consuming, and to analyse which aspects influence these perceptions, both on the side of the reader as well as regarding the properties of the book. Previous work on emotion analysis in natural language processing includes creating dictionaries of words associated with different psychologically relevant categories, including a subset of emotions.24 A branch of computational linguistics develops learning methods to analyse (recognise then classify) expressions of emotion that have previously been manually annotated (underlined or extracted) in texts. However, approaches using dictionaries and distant labelling commonly do not lead to the best performance achievable with automatic methods. To achieve a higher performance with automatic methods, we must rely on manually annotated data and machine learning, and require huge amounts of annotated data provided by scholars who are experts in the knowledge domain – historical testimonies of readers in this case study. The recent state of the art is the use of transfer learning from manual annotations to more specific predictions. Still, it has been shown that transferring from one domain to another is challenging, as the way emotions are expressed varies between areas. And as emotions modelling relies less on processing the ‘human’ depiction of transactions between subjects and material than on abstract models, it is still insufficiently accountable. To sum up this state of knowledge, the observation of aesthetic emotions and the reading brain from historical sources, whether supported by research in the humanities25, digital humanities or computational linguistics, substantiates the argument that reading stimulates, but also mirrors our minds.26 Yet there is so far no integrated framework of research.27 Scholars adopting a sociocultural approach tend not to rely on paradigms from psychology, while psychologists use protocols based on textual stimuli that are rarely encountered in naturalistic situations nor are they historically contextualised. Therefore, analysing historical corpora such as the nineteenth-century manuscript letters of readers to a philosopher is a scientific challenge that implies navigating between different strands of research and trying to combine them.

READ-IT, a recently developed digital tool to explore the cultural heritage of reading

Our case-study is interestingly hybrid and resorts to several methodological approaches embedded within the Reading Europe Advance Data Investigation Tool (READ-IT https://readit-project.eu/ 2018-2021). This collaborative research project focuses on regenerating lost connections about the cultural heritage of reading through an interdisciplinary perspective and the development of innovative tools. With expertise in computer sciences, information sciences, humanities and digital humanities, its researchers address the challenges set by large volumes of highly diverse cultural heritage objects related to the complex activity of reading as well as its evolution across time and space. More specifically READ-IT aims to explore vast corpora of ordinary readers’ testimonies in multiple languages from the eighteenth to the twenty-first centuries.

This data-driven strategy aims to produce (and has by now almost completed) a toolbox of digital and conceptual solutions enabling end-users to uncover new findings on European historical as well as current reading practices. Tools include (1) a conceptual model of reading experience capturing broad aspects, e.g. who reads what?, as well as close effects, e.g. readers’ responses; (2) the Reading Experience Ontology (REO), a module for the ISO standard CIDOC-CRM for cultural heritage; (3) the annotation interface for text-based sources; (4) the Crowdsource of Experience Ontology (CEO); (5) a multimodal crowdsourcing platform for collecting reading testimonies (including during the pandemic), such as archives, postcards, chatbot conversations; (6) machine-learning services for the pre-annotation of sources and images. All components support the five initial languages of the project (English, Czech, French, German, Italian), with on-going or potential transfers and adaptations of the ontology to new languages (Russian and Dutch for example) depending on the linguistic origin of the sources. While using the toolbox, heterogeneous case studies have generated comparable results and provided new opportunities for further research.

The READ-IT project targeted a unique viewpoint on how readers record, retrace and share their readings, but the research program has given rise to significant needs in artificial intelligence and more particularly in automatic language processing in order to answer questions about Why? and How? people read. These needs involve, among other things, the mass retrieval of historical and contemporary data and their pre-annotation in order to automatically detect in the sources passages containing reading testimonies or mentions of artworks. To achieve its objectives, the READ-IT project has mobilised several technologies. Among them, Named Entity Recognition (NER), which is a classic task in automatic language processing consisting in locating and associating mentioned entities present in a text in predefined categories such as the names of persons, organisations, places, works of art. Recent approaches are based on the BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) models and more particularly ‘onto notes’ for English and ‘Multilingual Cased’ for other languages. These very complete language models allow the identification of mentions of creative works in about a hundred languages, in addition to identifying 18 other types of entities.28 Secondly, we sought to implement detection tools to enable the automatic recognition of testimonies of reading experiences. Initially, we thought of using computational deep-learning methods, but these require large amounts of annotated resources, and this requirement could not be met. As a result, we developed rule-based models for detecting reading situations in texts. The reading evidence detection system is embedded in the tool, and works in the following languages: French, English, Dutch, German, Czech, Russian, Italian. A qualitative evaluation was conducted on these models to give satisfactory results.29 In a nutshell, the READ-IT annotation tool now has the ability to automatically spot and point out specific elements in readers’ reports. This ‘pre-annotation’ highlights text passages containing reading experiences, as well as named entities in the text (especially mentions of creative works, such as names of books, plays, etc.). This technique undeniably saves time by allowing the users to concentrate on textual passages that require more detailed analysis and interpretation. Still while the READ-IT open access, enriched investigation tool does identify evidence about European reading experiences, and enables end-users to search for the main features of reading experiences (agent, resource, process, response), it is still a far cry from the detailed recognition and identification of readers’ emotional features that scholars are seeking.

We were thus interested in a use-case demonstrating the potential and accuracy of digital tools, whether specifically developed in READ-IT or already in existence. The overall design of the use-case was to combine the perspectives of cultural history and the sociology of texts with digital humanities, in order to expedite the whole technical and interpretative, quantitative and qualitative process of analysing textual sources as well as to find answers to our specific questions. Methodologically, the use-case was expected to show whether Digital Humanities tools and the READ-IT annotation interface enable a better (faster/ more accurate/ transferable/ interoperable) identification of nineteenth-century readers’ experience (i.e. agency, circumstances, sentiments, wording) than conventional close reading. Thematically, we envisaged that nineteenth-century manuscript letters by male and female readers would suggest why and how people read philosophy in nineteenth-century France, and to what extent male and female reading responses were differently or similarly reported and expressed in letters to a famous author. Both technological and thematical research questions described above involved picking the ‘right’ corpus, i.e. one providing a sufficient amount and diversity of challenges and insights in order to check the validity of the methodology for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of complex historical textual testimonies, as well as to advance the understanding of cultural/aesthetic emotions through a semantic approach to readers’ appraisals, sentiments and judgments.

Letters to Victor Cousin: a relevant corpus for the analysis of reading responses

The letters to Victor Cousin met various criteria for a valid case study in the bespoke research program. The corpus was selected because it is both massive and well catalogued, as well as easily accessible in the manuscripts department of the Sorbonne central library in Paris. Victor Cousin’s correspondence contains 5628 letters to the French philosopher from 1449 correspondents, mostly educated readers, disciples and peers, among them some 110 women (7.5%).30 Several aspects of this manuscript collection point to a promising and challenging case study for our research questions. Victor Cousin’s philosophy is particularly likely to give rise to multiple accounts of reading.

A large number of men and women wrote to Victor Cousin because he was a public figure, an embodiment par excellence - in Descartes’ ‘homeland’-, of the persona of the philosopher. His reputation had grown since the 1820s, when he came to personify Liberal opposition ideology in the face of political repression. The suspension of his Sorbonne course on the history of modern philosophy in 1821 and a brief imprisonment in Germany in 1824 had established his reputation as a martyr for the cause of liberty. Granted permission to resume his course in 1828, Cousin became the quasi-official philosopher of the July Monarchy (1830–1848).31 A member of the Royal Council of Education, a State Councillor and Peer of France, in 1840 he was for some months the Minister of Public Instruction and Worship. He drew up a series of reports, gave several speeches on education, and promoted the adoption of his philosophical system by the secondary school curriculum. Thus, from the 1840s to the beginning of the twentieth century, generations of French (male) high school students were trained in the Cousinian philosophy that became, along with the classics, a shared foundation for the literate culture of the elites.32 Having retired from political affairs under the Second Empire, resigning his chair at the Sorbonne in 1855, Cousin remained an influential actor in intellectual life as a member of the Académie française and of the Académie des sciences morales et politiques. Those who were not trained in state high schools, especially women, could access Cousin’s philosophy by attending his lectures and the public sessions of the academies. They could also access Cousin’s philosophy in his books that had steadily followed one another since the beginning of the 1820s. The Sorbonne lectures were published, republished and reworked by the author or his disciples. From 1840 onwards, Cousin’s Collected Works were available from several publishers and in several formats. Cousin was also a media figure, and the circulation of his philosophy in France took advantage of the new press regime. He was a regular columnist for the famous highbrow magazine La Revue des deux mondes almost since its founding in 1829. Like fiction and other fields of knowledge, Cousin’s philosophy was partly caught up in the logic of serialisation which had an impact both on his writing process and on readers’ expectations. For example, from 1851 to 1856, Cousin published a series of portraits of seventeenth-century women which he explicitly referred to as a ‘gallery’.33 Cousin’s correspondents made frequent mention of these articles, and some of them undoubtedly approached his philosophy through the journal or through reprinted booklets: ‘It seems to me that it is in the name of all silent and reasoning women that I thank you, Sir, for the charming pages that I have just read in La Revue des deux mondes. I will join them in my memory to those on Pascal which appeared this summer in the same collection’, wrote Claire de Maillé de La Tour-Landry, Duchess of Castries, better known for her friendship with Balzac, around 1845.34

The very content of Cousin’s philosophy also seemed particularly propitious for the formulation of personally and emotionally formulated reading responses. Victor Cousin outlined a post-revolutionary philosophical project that came to be known as eclecticism.35 Three characteristics of this philosophy particularly struck Cousin’s contemporaries: firstly, it emphasised introspection as the founding methodology of philosophy. Cousin called it ‘internal’, ‘intimate’ or ‘interior’ observation, and the foreword to a synthetic edition of the Sorbonne lectures published in 1853, Du vrai, du beau et du bien [Lectures on the True, the Beautiful, and the Good] presented it as ‘the soul’ of philosophical endeavour.36 Criticising the limitations as well as the political consequences of eighteenth-century empiricism and sensualism, Cousin did not deny the primacy of observation; but he blamed these philosophical currents for not having applied it with sufficient rigour and for having ‘mislaid the method in a systematic way, by limiting it to the external world and to sensibility’. In order to reform philosophy, it was necessary, according to Cousin, to extend the bespoke method to all observable facts, that is to say to the ‘inner’ as well as to the ‘outer’ facts. Consequently, the philosopher’s primary task was to ‘enter into the consciousness’ and ‘observe the varied phenomena that are manifested there’. This introspective approach was named ‘psychological method’. Because it gave access to knowledge without the mediation of the senses, which could be misleading, its epistemological value was seen as superior to the observation of ‘external’ facts in the physical world. To designate this form of non-mediated perception, Cousin used the term ‘apperception’ and spoke of ‘the spontaneous perception of truth’.37 In line with these methodological considerations, Cousin established psychology as the foundation of modern philosophy: ‘Psychology is thus the condition and the vestibule of philosophy’, he wrote.38 The other branches of philosophy were subordinated to it. ‘Spontaneous perception’ gave true knowledge of truths which the history of philosophy proved to be universal. It made it possible to reach the True, the Beautiful and the Good: logic, aesthetics and morals followed from it. The second characteristic of Cousin’s philosophy therefore was spiritualism. ‘Our true doctrine, our true banner is spiritualism’, wrote Cousin in Du vrai, du beau et du bien.39 He underlined that eclecticism led to the true knowledge of an order of facts - moral and aesthetic in particular – pointing to spiritual transcendence. Yet his spiritualism also had a political dimension. It was designed for liberal post-revolutionary France. In the eyes of its promoter, this philosophical system was indeed the only one able to provide a stable ideology for the modern liberal regime born of the French Revolution. It was based, like the philosophy of the Enlightenment and like the new liberal political organisation, on an individualistic postulate presupposing the existence of an autonomous rational subject. But, thanks to the ‘apperception’ of values theory, reinforced by references to the Scottish philosophy of common sense, individualism was subsumed as the necessary ‘psychological method’ leading individuals to identify the same universal truths. Eclecticism substituted the consensus of enlightened spirits in place of divergent opinions, and of scepticism and relativism which had been, according to Cousin, the inevitable consequences of Enlightenment empiricism:

Our philosophy is the ally of all noble endeavours. It sustains religious sentiment; it supports true art [...]; it is the supporter of law; it also repels demagogy and tyranny; [...] and it leads human societies gradually to the true republic.40

Cousin’s emphasis on introspection and the philosophical exercise of the self, as well as on their metaphysical and political consequences, strongly appealed to contemporary readers in search of identity and stability in post-revolutionary France.41 It triggered personal, intimate philosophical endeavours as well as public careers in academia for his followers, as testified by the diversity of his correspondents.

Finally, letters to Cousin offered our study another promising dimension: the possibility of developing a gendered approach to this corpus. 110 women wrote to Cousin, most of them dealing with quite mundane matters like invitations to dinner. But some wrote about philosophy and it is interesting to situate these letters in the very context of Cousin’s work. After the end of the July Monarchy and the 1848 Revolution, Cousin was dismissed from his political functions. During the Second Empire, he became a moderate opponent of the regime, and left his position at the Sorbonne in 1855. As he increasingly depended on income from his publications, he inflected his writing correspondingly, choosing less controversial or political topics and targeting a more clearly general audience, including women. Such was the case with the series on the femmes illustres (famous women) of the Grand Siècle (seventeenth century), which brought to the fore the role of women in the literary, political and religious history of France, or with the earlier essay devoted to Pascal’s sister, Jacqueline.42 In so doing, Cousin accredited the importance of women in his readership. His correspondence with his English translator, Sarah Austin43, demonstrated the attention he paid to his female readers, in order to reach new sectors of the book market and expand his book sales. In 1849, he asked Austin to select extracts and publishing distribution channels in order to ensure the optimal diffusion of his works on the other side of the Channel:

You could give some articles and translations to certain newspapers: for example a piece from Santa Rosa to a society magazine, Mme de Longueville (very abbreviated) to a Methodist gazette, etc. The part about love would be quite suitable for your beautiful compatriots. Perhaps you could draw from my Jacqueline a curious little volume.44

Cousin’s correspondents were conscious of embodying an important part of his readership and of playing a role in his success. They often perceived themselves as representatives of his audience, like Sophie Dosne, an influential salonnière, muse and mother-in-law of (historian and politician) Adolphe Thiers, who wrote nearly 90 letters to Cousin between 1837 and 1865, and portrayed herself as ‘one of those infinitesimal elements of a parterre [theatre auditorium] which together decide the success of a work’.45 However, directing some of his publications towards women did not imply that Cousin took up an avant-garde position on their role in society. It definitely did not imply that he conceived the practice of philosophy as an endeavour open to women. Cousin defined philosophy as a ‘virile exercising of thought’.46 He criticised, as did many of his contemporaries, the ‘female author’, guilty in his eyes of transgressing the gendered division between the public and the private by ‘putting on sale to the highest bidder, exposing to the examination […] of the bookseller, the reader and the journalist, her most secret beauties, her most mysterious and touching charms, her soul, her feelings, her sufferings’.47 Thus, his female correspondents had to negotiate these contradictions: on the one hand they sent letters to an author writing about women with whom they could identify, and whom Cousin said he admired; but on the other hand, while discussing philosophy with him they were transgressing boundaries he himself had set. Caroline Angebert expressed it explicitly in a letter from 1828: ‘You do not have a more fervent disciple than me, or one who, I dare say, understands your sublime lessons better. I seek, I adore the truth, and yet I am a woman’.48

Technical and intellectual challenges

The chosen corpus of letters to Victor Cousin looked promising for a broad approach to gendered reading as well as to ‘ordinary’ readers of nineteenth-century philosophy, a largely under-explored area compared to the reading responses of peer readers and published authors.49 Yet it implied resorting to manuscript sources which raised technical issues of readability, digitisation and transcription. Practically, after random prospection in search of female correspondents in the Victor Cousin archives, we selected 35 letters amounting to 100 pages respectively from 21 men and 9 women, ranging from 1823 to 1864. The selected letters were then digitised by the Sorbonne special library services. Since the purpose was to upload the letters into the READ-IT annotation interface, a transcription into a computer accessible electronic version was necessary and there were few options. Transkribus50, an open-access, AI-powered, handwritten text recognition was an obvious one, that had been satisfyingly tested within the READ-IT consortium for the Optical Character recognition (OCR) of Czech twentieth-century handwritten diaries of primary and middle school students. For nineteenth-century French manuscript letters the process appeared more daunting.

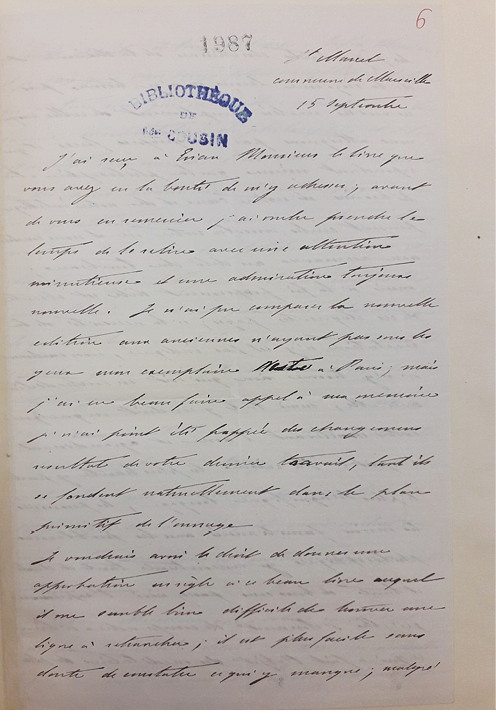

Letter from Roselyne de Forbin d’Oppède to Victor Cousin, BIU Sorbonne, nd [1859]

Although the documents have been well preserved, the scan above shows that deciphering the letters was challenging: both because of the thin paper used – the verso can be read through the recto thus making both illegible, and also because of faded ink that makes words pale or illegible. Challenges are mostly due to the variety of copperplate or English handwriting which was not standardised until the beginning of the twentieth century in France or in Italy where many correspondents of Victor Cousin originated. Furthermore, French is a language with accents. Transkribus ultimately ‘stumbled’ over several parts of these letters, leading to a time-consuming editing process for the first try. E-scriptorium, a recently developed transcription tool51 appears to be a better option but we did not have time to test it for this case study. We then resorted to another method based on a mixed machine-and-human eye approach requiring different steps: 1) a silent reading of each letter to familiarise the eye with the handwriting and content; 2) reading aloud each letter and recording it on google voice ‘speech to text’ while checking the automatic transcription on the screen – as the system ‘waits’ during vocal pauses, this process of initial transcription was fairly smooth and easy; 3) editing each transcription for main orthographic and lexical scoria. If the tone of the person recording is neutral and the voice clear, the transcription will require only light editing (such as adjusting feminine/ masculine word endings of past participles for example); 4) matching each transcribed letter with the scan of the original manuscript version to check and edit missing words, and mistaken readings of illegible parts, especially names. The difficulty of deciphering nineteenth-century handwriting, and of decrypting unfamiliar names and cultural references prevented us from fully delegating transcription to student interns lacking a good knowledge of the nineteenth-century lexicon and syntax, as well as of book, textual and cultural history in general. Therefore, the initial rough transcriptions had to be reviewed and corrected by experts through a scrupulous and lengthy re-reading. Given the cost of scanning and digitising manuscript documents outside automatic computer-assisted transcription tools, the procedure was feasible for only a small sample, and hardly seems extendable to massive corpora.

This case study raised an even bigger intellectual challenge. Reading responses to philosophy is an unknown territory. So far, research on reading experiences in READ-IT has focused on literary as well as leisure reading, with only occasional resources tracking rational or knowledge-oriented reading. Historians have so far studied scientists’ motivation and emotional research endeavours52 but not the affective responses of science readers. Yet, the notion of ‘emotional reading response’ is not exclusively related to a typically dedicated genre such as fiction, but encompasses a variety of textual perceptions and experiences. The American philosopher Martha Nussbaum maintains that readers of literature have a mixed and complex response to the ideas, situations and reasoning they encounter for example in novels. She describes it as an ‘upheaval of thoughts’53 blurring the boundaries between affective and rational effects of reading, as well as between aesthetic and intellectual appraisal. Other established critics and essayists commenting on highbrow literary reading and art contemplation, including Gaëtan Picon54, express similar notions of art and literature reading as a revelatory information experience, an emotion of knowledge or knowledge-emotion which also involves judgment.

We anticipated that because they might mix rational and subjective, judgmental and sentimental aspects, the inner effects of reading depicted by Victor Cousin’s readers would be quite complex both in their essence and in their formulations. The letters depict and discuss the readers’ experience of reading Cousin as an event making a substantial impact that involves knowledge and shakes the reader’s belief system. Both men and women readers share with Cousin the ‘upheaval of thoughts’ they felt. Both portray reading Cousin as a committed cognitive process, and their responses include admiration followed by reasoning, learning, perception, deduction, being drawn to write on one’s own and sending one’s work to Cousin. But there seems to be a difference between the external reading outcomes depicted by male readers after reading Cousin (i.e. offering to be of some help, acting out on the social or political scene, etc.) and the inner effects experienced by Cousin’s female readers while reading (‘feeling the breath of a genius’, elation, physical and mental well-being when confronted with thoughts in formal language, etc.).

Male readers mitigate the expression of their admiration with almost unemotional, considerations of their own views and engage in self-assuming peer-to-peer discussions:55

I have read with keen interest your adorable studies on some seventeenth-century women and have been most charmed to find in Madame de Chevreuse’s portrait a letter that you quote and the original of which I happen to possess. If you wished to have a look at this historical piece I would be most happy to communicate it to you. (Alphonse Baudot, a bibliophile).

I cannot think of a more equitable court than yours to hear a difficulty I encountered in reading your series of philosophical fragments. (Etienne Duriveau, military man).

You have given us here an excellent work, but one that will only reach those who least need it. (Cadet-Gassicourt, 1848, about a study of Rousseau).

In France, people want everything to be instantly very clear. In Germany, one likes some obscurity in order to bring light to it through one’s own work. I am awaiting your fragments with quite some impatience. (1828, Friedrich Wilhem Carové, philosopher).

Female readers display genuine authority in their arguments that suggest poised, pondered and matured personal views. But in contrast with the distance carefully maintained by men, women’s enthusiastic, sometimes even passionate engagement with Cousin’s philosophy stands out. It is also conveyed by the almost naive expression of their intellectual connection to the author as well as of the full impact of his work on their lives both as women and unpretentious fellow authors. While Friedrich Wilhem Carové acknowledges ‘Your studies on Plato have led you to the very centre of Greek philosophy; you may have found many things that we others have still not noticed’, Clarisse Bader confides ‘I thought I was hearing Plato’s own voice.’ In short, while men appear to express curiosity or at the most a subdued ‘keen interest’, women seem more prone to admit perceiving the whole scope of ‘knowledge emotions’ - surprise, interest, confusion and awe:

After receiving the brochure Madame de Longueville [...] having read it with avidity and such great pleasure... 56

I do not care much for Goethe as a person, I even mistreated him with conscientious delight, and yet! the way you speak about the big old man has touched me [...] I can hardly tell you the joy I felt when discovering these two renditions of the past. [...] Pages written in beautiful language and under the spell of a generous inspiration restore in me the fiery exaltations of better days.57

In ‘Emotions in art: seeing is believing’58, Greg Minnisale discusses how David Freeberg’s theory of art borrows from the discovery of ‘mirror neurons’ to suggest that ‘aesthetic experience is based on sensory and motor interpretation of figures, faces [...] as depicted in art [...] that provide a platform upon which it is possible to have richly emotional responses’. Drawing from Freeberg, Minnisale suggests that ‘this offline sensorimotor response to other people’s online sensorimotor actions is supposed to lay the basis for emotions such as empathy, anger and fear’. One could hypothesise that such a phenomenon is at work in reading experiences of Victor Cousin’s philosophical works by educated women and female authors of his time. Future studies might further analyse their letters for a deeper understanding of aesthetic emotions and emotional responses as experienced in intellectual reading as well as in the contemplation of art.

E-searching nineteenth-century emotions of reading through READ-IT

When annotating the letters to Victor Cousin, scholars are confronted with a variety of challenges and special needs. We need to account for the changing ways in which readers relate to books or texts, retrace their reading experiences, and express their personal emotions whether in cultural or ordinary-life circumstances over time. We need to compare and adapt historical and contextual variations in formulations by nineteenth-century readers to a generic data model and ontology establishing a separation between cognitive (e.g. understanding) and affective responses (e.g. emotion); and therefore, we need an extended and nuanced list of tags within a given category or class, e.g. admiration, joy, elation, etc., as sub-categories within the ‘emotion’ class. Ultimately we need to match nineteenth-century notions and expressions with concepts of the READ-IT ontology based on a twentieth-century, post- Second World War lexicon. This contemporary lexical basis remains valid for the ways of speaking of, say, today’s English-speaking online social networks of contemporary readers who post short comments that do not delve too deeply into their reading responses. But it does not reflect the sophisticated language of early readers of philosophy whose letters are not mere reading reports but substantial discussions of their own individual perception of moral theories.

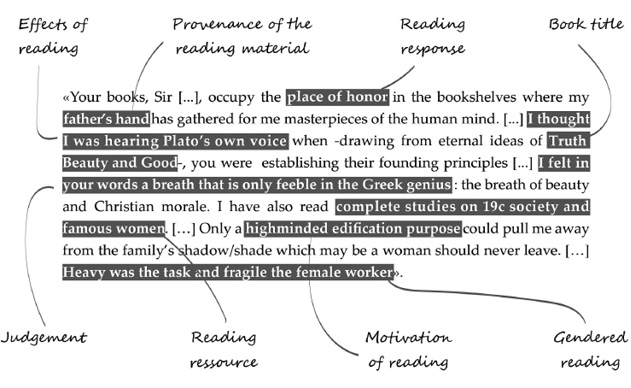

Textual and semantic search systems in READ-IT are precisely designed to meet such challenges raised by the linguistic diversity of reading testimonies. The purpose is to explore textual resources, to validate the categories of reading experiences identified in the data model, and ultimately to refine the formal ontology through a critical review of the categories and an iterative as well as collaborative editing of the annotations. In the figure below an excerpt of a letter (translated for this article) has been empirically and manually annotated prior to being uploaded in the annotation interface. The tags or comments attached to some expressions reflect a preliminary empirical observation and characterisation of the main, frequently expressed components of reader-response.

Clarisse Bader (1840–1902, female journalist, writer and historian). Paris, May 1864)

The tags manually attached to expressions also reflect the broad research interests and questions of scholars aiming to identify generic patterns in reading experience testimonies over a long period of time (from the eighteenth century to the present), and across vast amounts of statements in multiple languages from a huge diversity of people. In the last sentence of this excerpt the author of the reading report self-identifies as a fragile woman engaged in a heavy task, something which at first sight is tagged as evidence of gendered reading. Yet, a closer and more careful reading might produce a different interpretation. Clarisse Bader was herself a writer.59 Along with her letter, she sends Cousin her first book, namely an essay on women in ancient India (La femme dans l’Inde antique, 1864), the objective of which she explains as ‘seeking in ancient India the seeds that Christian civilisation was eventually bound to plant in modern India’. The ‘heavy task’ she complains about is that of writing her own book, not the mere reading of Cousin’s book. This sheds light on the previous sentence. Bader wrote for the edification of her contemporaries, especially women, a self-assigned duty that compelled her to leave the reassuring confines of her home and to step into the spotlight of the public sphere – a move deemed improper for any woman of the bourgeoisie, especially a conservative Christian woman. Reading Cousin’s work is thus experienced and described through the filter of Clarisse Bader’s own intellectual project and social trajectory and the formulation suggests a mixed – and rare for women of her times – writing/reading experience.

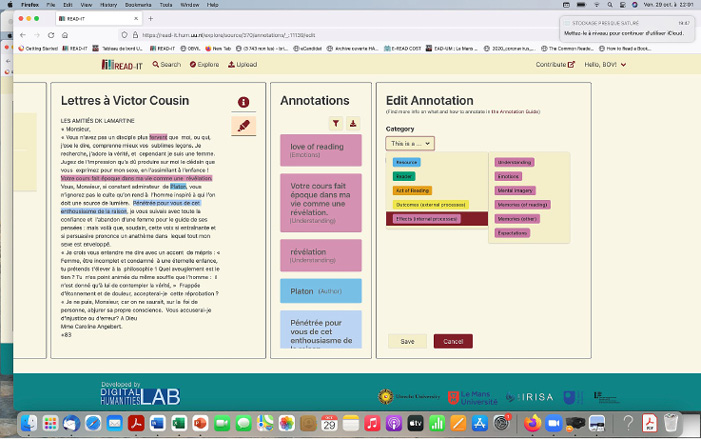

Through close reading - without the help of digital tools - insightful scholars might come up with a detailed understanding of what is expressed here as well as of its implicit background. But computer-assisted search tools can provide a step forward. The Reading Europe Advanced Data Investigation Tool text-mines resources through a pioneering semi-automatic semantic search - e.g. concept detection. The interface functions as follows: Resources (e.g. letters to Victor Cousin) are uploaded in the annotation portal (open access, https://read-it.hum.uu.nl) then annotated on screen by means of the interface functionalities. With its pre-existing ontology and repository of embedded concepts the READ-IT annotation interface allows for multiple exploration of uploaded documents: browsing resources; reusing and/or revising previously annotated sources and annotations; a collaborative annotation process; comparisons between different annotations of a resource: all tasks being undertaken either by the same individual scholar or by any number of other users interested in a concept and seeking to retrieve its typical or alternately varied expressive modalities. Depending on places, times, cultural contexts, people, etc., a concept will be diversely formulated through different words or series of words yet relate to a single and singular reality. Within READ-IT the semantic search, possibly combined with a textual search for reading testimonies in multiple languages, can lead for example to mapping a commonly held and shared notion or value hidden within and by the infinite diversity of its description by readers. The ontology and algorithms within the reading experience annotation interface encompass most of the empirical notations marked in the manually annotated example above. But its generic classes have been selected in a non-empirical process defining logical relations between terms and concepts, according to a rigorous, theoretical, inductive hierarchy. When using the annotation interface, scholars select any chain of words exhibiting a specific semantics and subsequently relate to a concept in a ‘controlled vocabulary’60 ensuring a minimal margin of error in the interpretation.

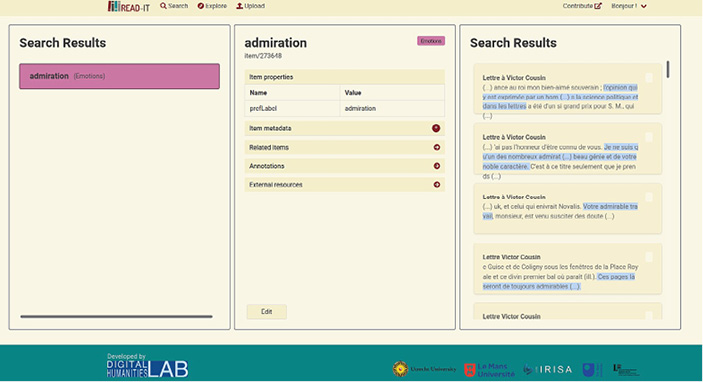

What remains to be seen is whether computer-assisted semantic searching can correctly identify as well as label both the broad lines of reading experiences reported in the letters and their individual variations and nuances from one correspondent to another. Or is it rather either the broad lines or the variations? Let’s take the example of ‘admiration’, a seemingly obvious and frequent notion in reader responses. Through the textual search system, the request is fairly straightforward: the word ‘admiration’ entered in the search window leads to extract the following results (from the corpus of letters to Victor Cousin selected):

The left column shows that ‘admiration’ has been tagged as a sub-category of Emotions; the middle column shows the metadata attached to the annotation; the right column shows different letters to Victor Cousin where the word admiration or admirable or the verb admire, etc., are used.

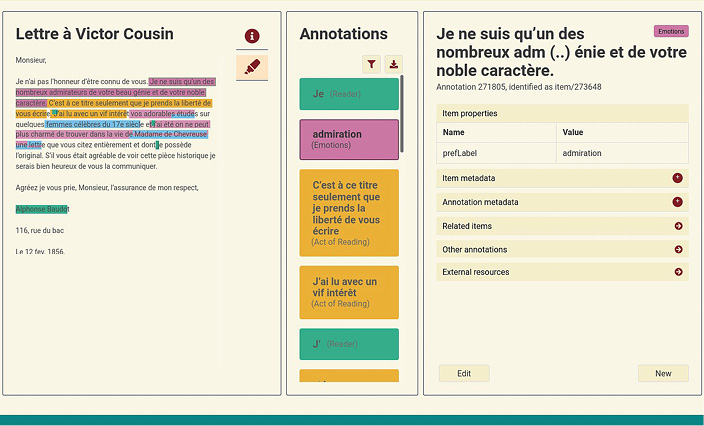

Through the semantic search system offered on the portal’s landing page, the request consists of a well-defined algorithm leading to linked data items based on the semantic features requested; in our example the request is to find expressions where ‘emotions’ is exactly related to or interpreted as ‘admiration’ (despite the absence of explicit terms). The following screen capture shows one of the letters and its annotations: on the left is the letter with textual selections in colours corresponding to different identified concepts: green for ‘Reader’, pink for ‘Effects’, yellow for ‘Act of reading’, etc. The middle column of annotations shows the labels and the class to which they belong; the right column focuses on the first sentence highlighted in the left column and its metadata.

Annotating the next example - the 1828 letter by Caroline Angebert previously quoted in this essay61 – requires second thoughts both in close and distant reading since the broad notion of admiration is scattered and diluted in a diversity of indirect expressions suggesting an emotional response to knowledge: the reader is a ‘fervent disciple’ of Cousin; when reading Cousin she feels ‘penetrated by rational enthusiasm’; attending his lectures or reading his work constitute ‘revelatory’ life-changing events. The ontology offers the choice between several concepts, and in the expressions quoted above the concept ‘effects’ of reading (internal processes) is relevant. Then using the ‘edit annotation’ functionalities in the right column allows us to browse the algorithm and to further detail the preliminary identifications in the annotation column: e.g. ‘revelation’ can be labelled as an intense ‘understanding’, a subcategory of the class of ‘Effects (internal processes)’62 of reading. Further editing the annotation could lead to having a mandatory preferred label ‘understanding’ and a secondary label, thus ‘emotion’.

But it is possible for another annotator to see things differently: to select ‘emotion’ as a preferred label and ‘understanding’ as a secondary label. The word ‘revelation’ indeed highlights the mixed character, both emotional and rational, of responses to philosophy.63 It is highly polysemic and may assume different meanings depending on the cultural contexts in which it is situated as well as in a gender perspective. The term may evoke ecstasy and the experience of divine love, and locate the experience of reading in line with the Christian tradition of ecstatics and visionaries. The word may also take on a more theological meaning and refer to the classical opposition between the imperfect science of human matters and the perfect knowledge of God achieved through a combination of reason and faith. In a Catholic context, this second meaning pointed to the division between clerics and laymen which was also a gender division. Within Cousin’s philosophy, this second meaning was somewhat altered by developments related to ‘apperception’ or ‘the spontaneous perception of truth’, mentioned above. It took on a more secular (and masculine) colouring so that ‘revelation’ may be associated with a range of other words and sentences such as ‘Love’ (capitalised) or ‘divine love’, ectasia, vision, faith, ‘rational faith’, true knowledge or ‘Truth’ (capitalised). Or even ‘apparition’ as when ‘truth appears to someone’s mind’. In fact, while this section of the letter attributes a positive value to a surprising understanding, another sentence states the opposite: ‘Mais voilà que soudain…’ (But all of a sudden…). The reader then explains that Cousin’s deprecating comments on women take her aback as a breach of author-reader confidence.

The whole letter suggests an overarching experience covering the whole scope of knowledge emotions (surprise, interest, confusion and awe). Attaching ‘revelation’ to a preferred concept - such as ‘understanding’ - rather than to ‘emotion’ or even to ‘expectations’, undermines the effects of reading described here. Only a long list of additional suggestions or labels could account for the richly intricate meanings and contents of the word ‘revelation’ here, which encompasses positive as well as negative appraisal, and mixes ‘admiration and deceit’. But recovering the full extent of what lies behind the word ‘revelation’ implies resorting to a broader understanding of women’s reading in the nineteenth century.64 And as the annotation portal allows for a detailed list of suggestions, the very purpose of the exploration and annotation tools such as READ-IT consists conversely in reducing the infinite variety of expressions to the closest possible, albeit imperfect, common denominator. Future research steps should ideally involve the development of a dynamic ontology that will enrich itself through machine learning and ultimately incorporate an infinite variety of suggested labels as well as verified interpretations by scholars in the relevant knowledge domain.

To conclude...

Ultimately, it would seem that our research faced initial difficulties similar to those encountered by the promoters of the first collective projects in the field of digital humanities in the 1960s and 1970s. While computers made it possible to save a lot of time in the calculation phase and in the processing of data, the time required to encode these same data proved to be extremely long. This was true, for example, for the first French collective project launched by medieval historians from the Ecole pratique des hautes études for a computer-assisted study of the Florentine catasto (land survey) of 1427, which lasted more than ten years (1966-1978).65 So much so that it is possible to ponder, at the end of the analysis, whether such an undertaking really saved time! More seriously, time lost or gained is here a matter of perspective: the research time of individual scholars undertaking such project ab initio is certainly duplicated by the technical handling of sources; but for future scholars taking over, accessing historical sources that are now made readily available by previously developed visualisation and exploration tools represents a major time as well as research gain.

Along the way, this essay has underlined what could be the contribution of Digital Humanities and Information and Communication Technologies for research in cultural history and the exploration of such archival sources. Assessing the balance between benefits and limitations means acknowledging that the interpretative, qualitative approach of humanities scholarship can make the most of dealing with large amounts of structured data. Applying digital technology to complex research questions in the humanities, as displayed in the READ-IT project, fosters the co-construction, with scholars in computer sciences, of online annotation tools for the collaborative study of empirical sources. It also leads to the computational analysis of large corpora of textual data, which significantly enhances the exploration of large corpora and provides a rigorous as well as panoramic view of what is at stake. Yet, as observed by Kaltenbrunner, ‘The use of digital technology thus creates exciting new possibilities to supplement and extend humanistic knowledge production, but it also entails uncommon requirements regarding the epistemic, social, and material organization of research.’66 This case study, like others in the field, confirms that Digital Humanities methods and digital tools do not stand alone; they must be augmented by manual methods and by traditional close reading in order to produce the expected findings. But they also engage humanist scholars in a reflexive process that is crucial to advance the state of their disciplines. As noted by founding scholars in the ‘Mapping the Republic of Letters Project’, ‘The point is [...] that computational methods provide novel insights into your sources. We designed and developed data visualisations not to do our work for us, but rather to point out where our work lies.’67

Reference list

ADLER, Laure and BOLLMANN, Stefan. Les femmes qui lisent sont dangereuses. Paris, Flammarion, 2011.

AFFLERBACH, Peter and JOHNSTON, Peter. On the Use of Verbal Reports in Reading Research. Journal of Reading Behavior 16 (4), Dec. 1984, p. 307–322. DOI: 10.1080/10862968409547524

BRAIDA, Lodovica, OUVRY-VIAL, Brigitte (dir.), Lire en Europe. Textes, Formes, lectures (XVIIIe-XXIe siècle), Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, coll. « Histoire », 2020, 378 P., avec la collaboration d’Elisa Marazzi et Jean-Yves Samacher, ISBN :978-2-7535-8046-6.

BURKE, Michael. Literary reading, cognition and emotion. New York, Routledge, 2011.

CAVALLO, Guglielmo and CHARTIER, Roger (eds.). A History of Reading in the West. Trans. Lydia Cochrane. Cambridge UK, Polity, 1999.

CERTEAU, Michel de. L’invention du quotidien, 1. Paris, Gallimard, 1990.

CHARTIER, Roger. Pratiques de la lecture. Paris, Payot, 1993.

COUSIN, Victor. Cours de philosophie. Introduction à l’histoire de la philosophie. Paris, Pichon et Didier, 1828-9.

COUSIN, Victor. Les femmes illustres du dix-septième siècle. Revue des deux mondes, 15 janvier 1844.

COUSIN, Victor. Du vrai, du beau et du bien. Paris, Didier, 1853.

DARNTON, Robert. First Steps Toward a History of Reading. Australian Journal of French Studies, 1986, vol. 23, p. 5–30.

ECO, Umberto. Lector in fabula: la cooperazione interpretative nei testi narrative. Milan, Bompiani, 1979.

FINKELSTEIN, David and McCLEERY, Alistair. Scottish Readers Remember. Edinburgh Napier University, 2006-10. Access through Internet: https://www.napier.ac.uk/research-and-innovation/research-search/projects/scottish-readers-remember

FLAM, H. and KLERES, J. (eds.). New Methods of exploring emotions. New York, Routledge, 2015.

FLINT, Kate. The Woman Reader, 1837–1914. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993.

ISER, Wolfgang, The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978.

JACOBS, Alan. The pleasures of reading in an age of distraction. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011.

JACOBS, Arthur. Towards a Neurocognitive Poetics Model of literary reading. In WILLEMS, R.M. (ed.), Towards a cognitive neuroscience of natural language use [online]. Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 135–195. DOI 10.1017/CBO9781107323667.007

JAUSS, Hans Robert. Aesthetic experience and literary hermeneutics. Minnesota-St Paul, University of Minnesota Press, 1982.

LAHIRE, Bernard. La culture des individus. Paris, La Découverte, 2004.

LYONS, Martyn. Readers and Society in Nineteenth-Century France. Basingstoke UK, Palgrave, 2001.

LYONS, Martyn and TAKSA, Lucy. Australian Readers Remember, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1992.

MÄKINEN, Ilkka. Leselust, Goût de la lecture, Love of Reading: Patterns in the Discourse on Reading in Europe from the 17th until the 19th century. In NAVICKIENĖ, Aušra et al (eds.), Good Book, Good Library, Good Reading: Studies in the History of the Book, Libraries and Reading from the Network HIBOLIRE and its Friends. Tampere, Tampere University Press), 2013, p. 263–285.

MANGEN, Anne and VAN DER WEEL, Adriaan. The evolution of reading in the age of digitisation: an integrative framework for reading research. Literacy [online], 2016, vol. 50, no. 3, p. 116–124.

McKENZIE, Donald. Bibliography and the sociology of texts. Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press, 1999.

MENNINGHAUS, Winfried et al. What Are Aesthetic Emotions? Psychological Review, 2018, 126. DOI: 10.1037/rev0000135

MINNISALE, Greg. Emotions in Art: Seeing is believing. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core on 07 July 2018.

NUSSBAUM, Martha C. Cultivating humanity: a classical defense of reform in liberal education. Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, 1997.

NUSSBAUM, Martha C. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions [online]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001 [Consulted 14 May 2019]. DOI 10.1017/CBO9780511840715.

OUVRY-VIAL, Brigitte and ANTONINI, Alessio. Reconnecting with the evolving journey of reading. 2021. Access through Internet: https://www.culturalpractice.org/article/reconnecting-with-the-evolving-journey-of-reading

PENNEBAKER, J. W., BOOTH, R. J., BOYD, R. L., and FRANCIS, M. E. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC2015. Austin TX, Pennebaker Conglomerates (www.LIWC.net), 2015.

PICARD, Michel. La lecture comme jeu: essai sur la littérature. Paris, Editions de Minuit, 1986.

PICON, Gaëtan. L’usage de la lecture. Paris, Mercure de France, 1960.

PLAMPER, Jan. The history of emotions: an introduction. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017.

PROUST, Marcel. Sur La lecture, preface to John Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies. Paris, Mercure de France, 1906.

ROSENWEIN, Barbara H. Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions. Passions in Context I [online]. Vol. 1, 2010. Access through Internet: https://www.passionsincontext.de/uploads/media/01_Rosenwein.pdf.

ROUXEL, Annie. Oser lire à partir de soi. Enjeux épistémologiques, éthiques et didactiques de la lecture subjective. Revista Brasileira de Literatura Comparada [online], 2018, vol. 20, no. 35, p. 10–25.

TROWER, Shelley. Memories of Fiction: An Oral History, 2014-18. Access through Internet: https://memoriesoffiction.org.

VEMEUREN, Patrice. Victor Cousin, Le jeu de la philosophie et de l’État. Paris, L’Harmattan, 1995.

VINCENT, David. Literacy and popular culture: England 1750–1914. Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

WOOLF, Virginia. How Should One Read a Book? In WOOLF, Virginia. The Common Reader, Second Series. London, Hogarth Press, 1932 [1926].

1 OUVRY-VIAL, Brigitte and ANTONINI, Alessio. Reconnecting with the evolving journey of reading. 2021. Access through Internet: https://www.culturalpractice.org/article/reconnecting-with-the-evolving-journey-of-reading

2 DARNTON, Robert. First Steps Toward a History of Reading. Australian Journal of French Studies, 1986, vol. 23, p. 5–30.

3 The ludic posture of fiction readers has been well established by ECO, Umberto. Lector in fabula: la cooperazione interpretativa nei testi narrativi. Milan, Bompiani, 1979, and PICARD, Michel. La lecture comme jeu: essai sur la littérature. Paris, Editions de Minuit, 1986. However the ‘love of reading’, ‘plaisir de lire’, ‘Leselust’ – unremitting buzzwords for lay critics, is seen as an implicit feature of reading – see JACOBS, Alan. The pleasures of reading in an age of distraction. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011. MÄKINEN, Ilkka. Leselust, Goût de la lecture, Love of Reading: Patterns in the Discourse on Reading in Europe from the 17th until the 19th century. In NAVICKIENĖ, Aušra et al (eds.), Good Book, Good Library, Good Reading: Studies in the History of the Book, Libraries and Reading from the Network HIBOLIRE and its Friends. Tampere, Tampere University Press, 2013, p. 263–85.

4 MENNINGHAUS, Winfried et al. What Are Aesthetic Emotions? Psychological Review, 126, 2018. DOI: 10.1037/rev0000135.

5 The state of knowledge below tries to convey as briefly and still as comprehensively as possible recent contributions to the historical, theoretical as well as computational study of reading emotions. Obviously we cannot quote the many enlightening works contributing to advances in the field. However, we would like to acknowledge the significance of fruitful and friendly discussions held over the years with several colleagues involved in European reading or readership studies. Coming from different venues and various disciplinary or methodological approaches, those were essentially members of READ-IT.eu, of COST action E-READ and its Vilnius conference, and of course SHARP members at large. While the pioneering UK Reading Experience Database was an early incentive, fresh perspectives and sources also came from Central European archives in Prague and from North European special funds for which Finnish colleagues such as Kati Launis, Eva Pyrhönen, Kirstin Salmi-Niklander, Ilka Mäschinen were specially helpful.

6 Verbal reports are general descriptions of subjects’ cognitive processes and experiences. See AFFLERBACH, Peter and JOHNSTON, Peter. On the Use of Verbal Reports in Reading Research. Journal of Reading Behavior 16 (4), Dec. 1984, p. 307–322. DOI: 10.1080/10862968409547524.

7 BARTHES, Roland. Le plaisir du texte. Paris, Seuil, 1973; BARTHES, Roland. La mort de l’auteur. Essais critiques IV. Paris, Seuil, 1984; FOUCAULT, Michel. Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur? Dits et écrits, t. I. Paris, Gallimard, 1969, p. 789–821.

8 PROUST, Marcel. Sur la lecture, preface to John Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies. Paris, Mercure de France, 1906. WOOLF, Virginia. How Should One Read a Book? In WOOLF, Virginia. The Common Reader, Second Series. London, Hogarth Press, 1932 [1926].

9 ISER, Wolfgang, The Act of Reading: a Theory of Aesthetic Response. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978. JAUSS, Hans-Robert. Aesthetic experience and literary hermeneutics. Minnesota-St Paul, University of Minnesota Press, 1982.

10 CHARTIER, Roger. Pratiques de la lecture. Paris, Payot, 1993. CAVALLO, Guglielmo and CHARTIER, Roger (eds.). A History of Reading in the West. Trans. Lydia Cochrane. Cambridge UK, Polity, 1999.

11 McKENZIE, Donald. Bibliography and the sociology of texts. Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press, 1999. LAHIRE, Bernard. La culture des individus. Paris, La Découverte, 2004.

12 BRAIDA, Lodovica and OUVRY-VIAL, Brigitte (eds.), Lire en Europe. Textes, formes, lectures (XVIIIe-XXIe siècle), Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2020.

13 LYONS, Martyn. 2001. Readers and Society in Nineteenth-Century France. Basingstoke UK, Palgrave, 2001. VINCENT, David. Literacy and popular culture: England 1750–1914. Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

14 FLINT, Kate. The Woman Reader, 1837–1914. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993. ADLER, Laure and BOLLMANN, Stefan. Les femmes qui lisent sont dangereuses. Paris, Flammarion, 2011.

15 ROUXEL, Annie. Oser lire à partir de soi. Enjeux épistémologiques, éthiques et didactiques de la lecture subjective. Revista Brasileira de Literatura Comparada [online], 2018, vol. 20, no. 35, p. 10–25.

16 MAR, Raymond and OATLEY, Keith. The Function of Fiction is the Abstraction and Simulation of Social Experience. Perspectives on Psychological Science [online], 2008, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 173–192.

17 RUBERY, Matthew (ed.). Audiobooks, literature, and sound studies. New York, Routledge, 2011.

18 BURKE, Michael. Literary reading, cognition and emotion. New York, Routledge, 2011.

19 JACOBS, Arthur. Towards a Neurocognitive Poetics Model of literary reading. In WILLEMS, R. M. (ed.), Towards a cognitive neuroscience of natural language use [online]. Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press. 2015, p. 135–195. DOI 10.1017/CBO9781107323667.007

20 LYONS, Martyn and TAKSA, Lucy. Australian Readers Remember. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1992; TROWER, Shelley. Memories of Fiction: An Oral History, 2014-18. Access through Internet: https://memoriesoffiction.org. FINKELSTEIN, David and McCLEERY, Alistair. Scottish Readers Remember. Edinburgh Napier University, 2006-10. Access through Internet: https://www.napier.ac.uk/research-and-innovation/research-search/projects/scottish-readers-remember

21 ROSENWEIN, Barbara H. Problems and Methods in the History of Emotions. Passions in Context I [online]. 2010, vol. 1. Access through Internet: https://www.passionsincontext.de/uploads/media/01_Rosenwein.pdf. FLAM, H. and KLERES, J. (eds.). New Methods of exploring emotions. New York, Routledge, 2015.

22 PLAMPER, Jan. The history of emotions: an introduction. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2017.

23 SURH, Carla. Language and cognition in the construction of emotive stereotypes. In BERNARDEZ, E., JABONSKA-HOOD, J. and STADNIK, K. Bern, Peter Lang, 2019, p. 174–193.

24 See the early and influential work of PENNEBAKER, J. W. et al. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC2015. Austin, TX: Pennebaker Conglomerates (www.LIWC.net), 2015.

Also the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) dictionary by MOHAMMAD, Saif M. and TURNEY, Peter D. Crowdsourcing a word–emotion association lexicon.

Computational intelligence, 2013, 29 (3), p. 436–465, which offers more than 14,000 words for a set of discrete emotion classes.

25 As presented in a recent released comprehensive study; CHAUVAUD, Frédéric, DEFIOLLE, Rodolphe and VIGARELLO, Georges. La palette des émotions. Collection Essais, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2021.

26 ‘The mirror system is the mechanism whereby an observer understands a perceived action by simulating, without executing, the agent’s observed movements’ – JACOB, Pierre and JEANNEROT, Marc. The motor theory of social cognition: A critique. Trends in Cognitive Science, 2005, 9, p. 21–25.

27 MANGEN, Anne and VAN DER WEEL, Adriaan. The evolution of reading in the age of digitisation: an integrative framework for reading research. Literacy [online], 2016, vol. 50, no. 3, p. 116–124.

28 Person, facility, organisation, location, product, event, work of art, law, language, date, time, percent, money, quantity, ordinal, cardinal.

29 The NLP work in the READ-IT project described here was conducted by Guillaume Le Noé-Bienvenu at IRISA (CNRS, France) in close collaboration with Dr. François Vignale who handled the qualitative evaluation campaigns at Lab-3LAM (Le Mans University, France).

30 Biblothèque Interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne (henceforth BIU), Victor Cousin papers (henceforth MSVC) 214–256.

31 VEMEUREN, Patrice. Victor Cousin, Le jeu de la philosophie et de l’État. Paris, L’Harmattan, 1995.

32 BROOKS, John I. The Eclectic Legacy. Academic Philosophy and the Human Sciences in Nineteenth-Century France. Newark DE, University of Delaware Press, 1998.

33 COUSIN, Victor. Les femmes illustres du dix-septième siècle. Revue des deux mondes, 15 janvier 1844, p. 194.

34 Duchesse de Castries to Victor Cousin, Paris, 19 janvier [1845?], BIU Sorbonne MSVC 221.

35 GRONDEUX, Jérôme. Raison, politique et religion au XIXe siècle: le projet de Victor Cousin, unpublished habilitation thesis, Université Paris IV-Sorbonne, 2008; VEMEUREN, Victor Cousin, op. cit.

36 COUSIN, Victor. Du vrai, du beau et du bien. Paris, Didier, 1853, p. ii.

37 Ibid., p. 55–62.

38 COUSIN, Victor. Préface de la première édition (1826). Fragments philosophiques, Paris, Ladrange, 3e édition, 1838, vol. 1, p. 54.

39 COUSIN. Du vrai, du beau et du bien, op. cit., p. iii.

40 Ibid., p. v.

41 GOLDSTEIN, Jan. The Post-Revolutionary Self. Politics and Psyche in France, 1750–1850, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, 2005.

42 COUSIN, Victor. Jacqueline Pascal. Paris, Didier, 1845.

43 JOHNSON, Judith. Sarah Austin and the Politics of Translation in the 1830s. Victorian Review. 2008, 34/1, p. 101–113.

44 71 letters from Victor Cousin to Sarah Austin, BIU Sorbonne MSVC 209, 45, nd [1849].

45 76 letters from Sophie Dosne to Victor Cousin, 1837–1865, BIU Sorbonne MSVC 210, Lille, 16 octobre 1846.

46 COUSIN, Victor. Cours de philosophie. Introduction à l’histoire de la philosophie. Paris, Pichon et Didier, 1828–9, vol. 1, p. 34 and p. 19.

47 Ibid., p. 8.

48 Caroline Angebert to Victor Cousin, letter from Dunkerque, 30 septembre 1828, BIU Sorbonne MSVC 214, reprinted in SECHE, Léon. Les amitiés de Lamartine, première série. Paris, Mercure de France, 1911, p. 182. See GOLDSTEIN, Jan. Saying ‘I’: Victor Cousin, Caroline Angebert, and the Politics of Selfhood in 19th-Century France. In ROTH, Michael S. (ed). Rediscovering History. Stanford CA, Stanford University Press, 1994, p. 240–275.

49 ALLEN, James Smith. In the Public Eye. A history of reading in modern France, 1800–1940. Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1991.

52 Recent examples are: GUIGNARD, Laurence and FAGES, Volny (eds.) Libido sciendi. L’amour du savoir (1840–1900), special issue, Revue d’histoire du 19e siècle, 2018, 57; and WAQUET, Françoise. Une Histoire émotionnelle du savoir, XVIIe-XXIe siècle. Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2019. Or even HEAS, Stéphane, ZANNA, Omar. Les émotions dans la recherche en sciences humaines et sociales, épreuves du terrain, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2021.

53 NUSSBAUM, Martha C. Cultivating humanity: a classical defense of reform in liberal education. Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press, 1997. NUSSBAUM, Martha C. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions [online]. Cambridge UK, Cambridge University Press, 2001 [Accessed 14 May 2019]. DOI 10.1017/CBO9780511840715.

54 PICON, Gaëtan. L’usage de la lecture. Paris, Mercure de France, 1960.

55 We translate a selection of excerpts from different letters to Victor Cousin, BIU Sorbonne.

56 Julienne Le Cat d’Hervilly, Comtesse Caffarelli, Letter to Victor Cousin, BIU Sorbonne, MSVC 221, nd [1852].

57 Antoinette Dupin, Letter to Victor Cousin, BIU Sorbonne, MSVC 226, nd [1841].

58 MINNISALE, Greg. Emotions in Art: Seeing is believing, downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core on 7 July 2018.

59 ERNOT, Isabelle. Des femmes écrivent. L’histoire des femmes au milieu du XIXe siècle: représentations, interprétations. Genre et Histoire, 4, Printemps 2009, consulted 22 October 2021 at http://journals.openedition.org/genrehistoire/742

60 A carefully selected list of words and phrases with standardised meaning and definitions, which are used to retrieve and tag units of information.

61 We translate: ‘Sir, you do not have a more fervent disciple than I, or one who, I dare say, understands your sublime lessons better. I seek, I adore the truth, and yet I am a woman. I let you judge the effect on me of your contempt for my gender which you associate with childhood! […] Penetrated by your rational enthusiasm, I was following you with all the trust and abandonment of a woman looking for a guide for her thoughts. But all of a sudden, this so very persuasive and stirring voice pronounces an anathema shrouding all my gender.’

62 As shown on the screen capture, the ‘Effects (internal processes)’ category leads to options of sub-classes: Understanding; Emotions; Mental Imagery; Memories (of Reading); Memories (other); Expectations.

63 Aesthetic emotions interestingly blur the lines between feelings and judgmental reactions SCHINDLER, I. et al. Emotion in aesthetics. Dordrecht, Springer Netherlands, 1995.

64 For example, as they react to Cousin’s work about women more readily than to other more abstract works, they appear to match Michel de Certeau’s definition of the reader as a ‘poacher’ in CERTEAU, Michel de. L’invention du quotidien, 1. Paris, Gallimard, 1990, p. 251. A deeper analysis of their letters might also reveal how the order in which they read Cousin’s works influences their emotional understanding and response, as well as the interplay between lived experience and its verbal articulation in the letters. See FULLER, Danielle and RAK, Julie. ‘True Stories’, real lives: Canada Reads 2012 and the effects of reading memoir in public. Studies in Canadian Literature [online], 2015, vol. 40, no. 2, p. 25–45.

65 LEJEUNE, Edgar. Médiévistes et ordinateurs. Organisations collectives, pratiques des sources et conséquences historiographiques (1966–1990). [unpublished doctoral dissertation], Université de Paris, 2021.

66 KALTENBRUNNER, W. Reflexive inertia: reinventing scholarship through digital practices. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Centre for Science & Technology Studies (CWTS), Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Leiden University, 2015.

67 EDELSTEIN, Dan et al. Historical research in a Digital Age: Reflections from the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project. Oxford, Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association, 2017.