Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2023, vol. 80, pp. 175–196 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2023.80.128

Repurchased, Ordered, Inherited: The Origins of Woodcut Blocks in the Königsberg Printing House of Hans Daubmann and His Heirs

Grażyna Jurkowlaniec

University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28,

00-927 Warsaw, Poland

E-mail: g.jurkowlaniec@uw.edu.pl

---------------------------------------

This research was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant number 2018/31/B/HS2/00533. Supplementary material can be found in the online database Urus (https://urus.uw.edu.pl/), which records all the actors, publications and printing matrices referred to in this paper.

---------------------------------------

Summary. Strategies adopted by the early modern printers vis-à-vis the acquisition and use of woodcut blocks depended on various internal and external factors. One might assume that the former—a printer’s personal ambitions and convictions concerning the role of illustrations in general—were in most part dependent on the latter (i.e., the economic, political or legal circumstances). Hans Daubmann, a printer active first in Nuremberg in 1547–54 and then in Königsberg in 1554–73, is an interesting case of a fairly consistent approach to illustrations, despite the diametrically different conditions in which each of his printing houses operated. In Nuremberg, he tried—but ultimately failed—to establish his professional position, struggling against tough competition and censorship, while, in Königsberg, he easily and almost immediately dominated the local market with support from the Duke of Prussia. In both places, Daubmann issued many illustrated works and invariably minimised the associated expenditures. He was exceptionally keen on repurchasing woodblocks from various sources, which was undoubtedly much cheaper than commissioning new items. Even when he chose to order new matrices, they usually reproduced popular models. This conservative strategy was preserved until the mid-17th century by Daubmann’s heirs and followers: Georg Osterberger, Johann Fabricius and Lorenz Segebade. They mostly reused these woodblocks, some heavily worn out, and only exceptionally developed the inherited stock of printing matrices.

Keywords: Prussia, Königsberg, Nuremberg, sixteenth century, print culture, Hans Daubmann

Perpirkta, užsakyta, paveldėta: Hanso Daubmanno ir jo ainių spaustuvės Karaliaučiuje medinių spaudos plokščių kilmė

Santrauka. Strategijos, kurių laikėsi Naujųjų amžių spaustuvininkai įsigydami ir naudodami medžio raižinių blokus, buvo priklausomos nuo įvairių vidinių ir išorinių veiksnių. Būtų galima manyti, kad spaustuvininko asmeninės ambicijos bei bendrosios nuostatos iliustracijų atžvilgiu buvo didžiąja dalimi priklausomos nuo kitų veiksnių: ekonominių, politinių ir teisinių aplinkybių. Įdomus spaustuvininko Hanso Daubmanno atvejis gerai atspindi jo nuoseklų požiūrį į iliustracijas: visų pirma dirbo Niurnberge nuo 1547 iki 1554, o vėliau Karaliaučiuje nuo 1554 iki 1573 metų, nepaisant iš esmės visiškai skirtingų aplinkybių, kuriomis veikė dvi jam priklausiusios spaustuvės. Niurnberge jis bandė, tiesa, galų gale nesėkmingai, įsitvirtinti kaip profesionalas. Jam prastai sekėsi kovoti prieš stiprius konkurentus ir cenzūrą. O Karaliaučiuje jis lengvai ir beveik iš karto ėmė dominuoti vietinėje rinkoje, sulaukęs Prūsijos kunigaikščio paramos. Abiejose vietose Daubmannas išleido daug iliustruotų knygų, tačiau kiekvienu atveju kiek įmanoma labiau mažindavo su leidyba susijusias išlaidas. Jis itin entuziastingai perpirkdavo medžio raižinių plokštes iš įvairiausių šaltinių, kas, be abejo, buvo nepalyginamai pigiau nei užsakinėti naujas. Netgi tais atvejais, kuomet jis pasirinkdavo naujas matricas, tai įprastai būdavo atkartoti populiarūs to meto modeliai. Šią konservatyvią strategiją iki XVII a. vidurio ir toliau palaikė jo įpėdiniai bei verslo perėmėjai: Georgas Osterbergeris, Johannas Fabricius ir Lorenzas Segebadė. Dažniausiai jie tiesiog tas pačias plokštes (kai kuriais atvejais net ir visiškai susidėvėjusias) vėl panaudodavo iš naujo ir tik išskirtiniais atvejais praplėsdavo paveldėtų spausdinimo matricų rinkinį.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Prūsija, Karaliaučius, XVI amžius, spausdinimo kultūra, Hansas Daubmannas.

Received: 2022 12 27. Accepted: 2023 04 05

Copyright © 2023 Grażyna Jurkowlaniec. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

In the dedicatory address to Albrecht Duke of Prussia, Hans Daubmann announced a collection of Johannes Brenz’s sermons on the Resurrection and Ascension of Christ as the first fruit of his Königsberg publishing house, where he purportedly completed the printing on 19 March 1554.1 However, as several scholars have already noted, this reference raises substantial doubts.2 It is a well-known phenomenon that the imprint information given in the title pages, dedications and colophons of sixteenth-century prints occasionally prove utterly unreliable, and some references were intentionally deceitful.3 This was also most likely the case here. Daubmann started his business in Nuremberg (where he had settled down in the winter of 1545) around 1547. He constantly struggled not only against the competition but also with the local authorities and legal regulations, which informed his decision to accept Albrecht’s invitation and move to Königsberg in 1554. However, this transfer was unlikely to have occurred in the winter or even early spring of that year. In April 1554, Daubmann was recorded in Nuremberg prison, and the document through which the council allowed him to leave the city for three years is dated 28 May 1554. Therefore, researchers usually assume that Daubmann arrived in Prussia in June at the earliest. However, even before he obtained permission to leave Nuremberg, he might well have sent his agent with the equipment for the printing shop to Königsberg.4

It is precisely this equipment, in particular the woodblocks, that is the main focus of this article. Undoubtedly, several external factors, ranging from incomparably less competition to Albrecht’s support to official orders from the local university, conditioned Daubmann’s rapid career development in Prussia. Nevertheless, the internal factors, including the range of woodblocks at the printer’s disposal, must have also played a role. In Prussia, Daubmann’s equipment was, at least quantitatively, impressive against the local background. However, it also raises a series of specific questions, two of which are of particular interest in this paper. The objectives of this work are, first, to reconstruct Daubmann’s stock in Nuremberg, and, second, to assess how much of this equipment he actually took along to Königsberg.

Typically for this kind of investigation, the principal research method is a scrutiny of impressions preserved in the surviving publications. A preliminary review of the books printed by Daubmann revealed that he had in his arsenal a significant number of rather worn-out woodblocks, which is obviously in line with the widespread phenomenon of the circulation of woodblocks among printing houses. However, this means that the investigation cannot be limited to the books issued by Daubmann himself, which leads to the delicate question regarding the reasonable demarcation of the research field. Daubmann’s potential sources are needles in a huge haystack, especially considering how vibrant the printing centre Nuremberg was in the mid-sixteenth century. Nonetheless, although a comprehensive presentation of the origins of every single woodblock which Daubmann used in Nuremberg remains an impossible mission, written accounts can still provide some fruitful directions.

Another caveat has to do with the tentative reconstruction of Daubmann’s Königsberg stock. Some designs recurring in his Nuremberg prints did not seem to appear in his Königsberg publications; however, the general truth is that the absence of evidence is not equivalent to the evidence of absence. Fortunately for our case, some of the woodblock that Daubmann used in Nuremberg have survived. Many others, however, remain unaccounted for and one cannot rule out that Daubmann brought to Prussia various blocks that he would never ultimately use. Some of these woodcuts might have remained unused, whereas others might have reappeared in a different place, or, even more likely, at another time, even after a long break, which brings Daubmann’s heirs or followers to the stage. Therefore, to trace the development of Daubmann’s stock between Nuremberg and Königsberg, one has to keep an eye on the production of several printers, including the local and those active in other milieux, as well as the contemporary and those operating earlier or later on.

Nuremberg

Daubmann’s activity as a printer was recorded in official Nuremberg documents beginning only in 1548. The dating of his earliest prints is often problematic, but there are reasons to believe that he already issued some publications in late 1547. For instance, the prognostics for 1548 must have been printed according to the common practice in the preceding year.5 This perfectly aligns with a contract he signed on 1 September 1547 with one of Nuremberg’s most prominent printers and publishers, Hans Guldenmund.6 The provision was that the latter would sell to Daubmann the equipment for his printing shop, including items labelled Gemel, which scholars usually recognise as woodblocks. The payment was arranged in two instalments, with 500 fl. recorded as the debt, which Daubmann would pay off only in mid-1549.

A comparison of Guldenmund’s and Daubmann’s publications revealed that many woodblocks, varying in terms of measures, subjects and the artistic value, were used consecutively in their printing houses. It is hardly surprising that some of these blocks had their ‘prehistory’, as Guldenmund’s stock was also heterogeneous, and it included matrices of which he was not the original owner, either. For instance, the title page of one of his prints was decorated with an Adoration of the Crucified Christ which had earlier recurred in the devotional prints of Ulrich Pinder and Friedrich Peypus of 1505 and 1507.7 Another example is the Last Judgment reappearing on the title pages of publications issued first by Peypus in 1517 and 1518,8 subsequently by Guldenmund in 15459, and finally by Daubmann in 1548.10

Some of the blocks Daubmann sourced from Guldenmund formed an unequivocal series of clearly defined boundaries, such as the set of ornamental initials. Particular letters from this series have been found to be dispersed across various prints, but the entire set may be reconstructed based on the consistency of the measures and the design. The series must have been created in the mid-1530s, considering the earliest occurrences of several letters. Admittedly, only single items may be found in books dating back to 1536, but one could safely assume that a simple ornamental alphabet was likely to have been produced as one undertaking rather than over several years.11

More ambiguous are groups of images that, although thematically consistent, cover a less clearly limited scope of items, an example being full-length likenesses of princes of the Holy Roman Empire, a genre of its own in the German printmaking of the mid-sixteenth century. Several likenesses representing this genre were signed by Michael Ostendorfer in the mid-1540s and published by Guldenmund. Two of these subsequently recurred with Daubmann’s address. These were the portraits of Wolfgang, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken, and Georg von Leuchtenberg.12 However, Daubmann also concurrently used woodblocks with full-length portraits, which are unattested in either Ostendorfer’s oeuvre or Guldenmund’s production. This is the case for the portrait of John Frederick of Saxony, impressed from the woodblock bearing Lucas Cranach the Elder’s device and the year 1546.13 The date sets the terminus post quem of the impression but is inconclusive regarding the block’s route. Guldenmund was rather unlikely and certainly by far not the only candidate for being the previous owner.

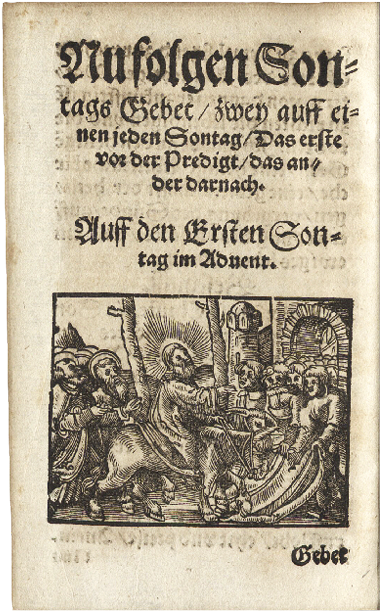

Probably the most interesting group of the blocks that Daubmann acquired from Guldenmund was the series with gospel scenes, all of a similar size (about 50 × 65 mm) but varied in style. The nucleus of this series is usually associated with Albrecht Dürer’s workshop and dated to the first or second decade of the sixteenth century.14 The cycle seems to have been originally conceived to illustrate gospel pericopes, but the most preserved impressions housed in various European collections are cut-out images with no text on the verso. Significant exceptions are ten items from this cycle used in Daubmann’s first profusely illustrated print, Veit Dietrich’s Kinderpredig, published in 1548 (Fig. 1).15

Figure 1. Entry into Jerusalem. In DIETRICH. Kinderpredig (see note 15), fol. 1r (Halle, Saale, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, AB 40 12/i, 7; https://digitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/vd16/content/pageview/1023523; urn:nbn:de:gbv:3:1-102124)

A full reconstruction of the history of this series between the early sixteenth century and 1548 is definitely beyond the scope of this article, but two points are essential to our case. First, the series, as reconstructed by Campbell Dodgson in 1909, initially lacked the many scenes needed to adequately illustrate an entire plenarium or a postil covering all Sundays and feasts of the liturgical year. Second, the earliest, although fragmentary, evidence of the use of this series in a plenarium may be dated only to the 1530s and referred to no one else but Hans Guldenmund. As Dodgson has already noted, among the few impressions that were cut out from a printed book is the Entry into Jerusalem housed in the British Museum, originally decorating the verso of the title page of Evangelia und Epistel … mit schönen figuren provided with the date 1534.16 One may complement Dodgson’s observation by adding that a plausible printer of this book was Hans Guldenmund, especially considering another fragment of a similar—or perhaps the same—publication preserved in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. The latter snippet contains no title page, but it ends with the colophon ‘Gedrückt zu Nuernberg durch Hans Guldenmund’.17

The origins of many other woodblocks which Daubmann had at his disposal in his early years in Nuremberg remain obscure, as is the case with those used in Caspar Huberinus’s catechism printed in 154918 or decorations of various calendars.19 Most of these designs appear as isolated occurrences. Furthermore, at least in some instances, Daubmann might have employed borrowed blocks rather than his own. However, there is a reason to assume that, from 1549 onwards, he substantially expanded his equipment. A prominent example is a set of woodblocks he repeatedly used to illustrate editions of the popular anthology of medical texts titled Artzneibuch.

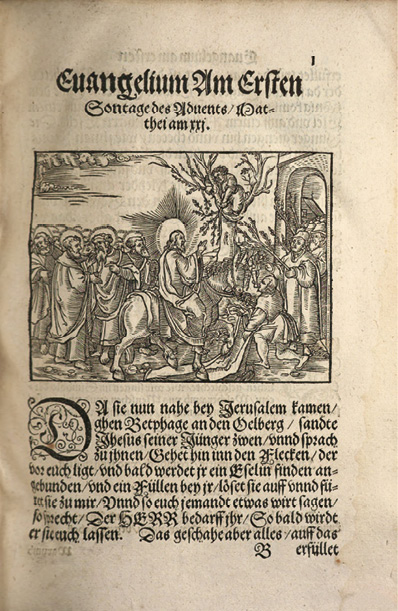

The designs of the woodcuts illustrating the Artzneibuch faithfully reproduce the respective compositions from the earlier edition of this anthology issued by Melchior Sachse in Erfurt in 1546.20 The link between Daubmann and Sachse invites us to consider the possibility of other relationships between these two printing houses, leading us beyond Nuremberg. Indeed, a series of gospel illustrations of ca. 55 × 70 mm were first employed by Sachse in 1548 and subsequently reused by Daubmann in 1550 in a collection of sermons by Michael Caelius (Fig. 2).21 The question remains whether Daubmann—who had just recently paid Guldenmund back on 10 June 154922 —purchased Sachse’s set or merely borrowed it. Either way, Sachse died in 1551, and the blocks remained with Daubmann, who, meanwhile, was further developing his stock.

Figure 2. Entry into Jerusalem. In CAELIUS. Ein Danck, Beicht und Betbüchlein (see note 21), fol. E6v (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Asc. 1028; https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00019316?page=80; urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00019316-5)

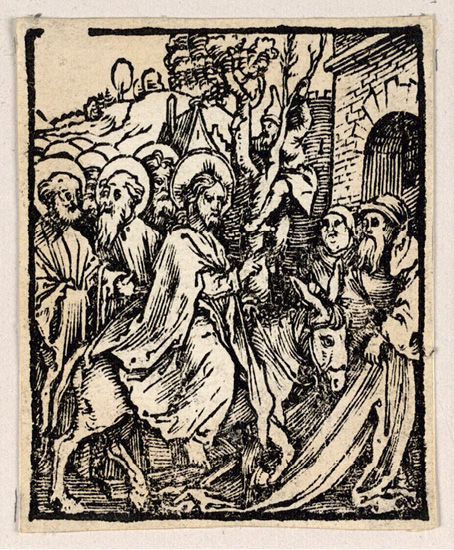

Some woodblocks were produced specifically for Daubmann, or, at the very least, he was the original user. Specifically, these include a set of initials with mythological scenes traceable in his prints from 1552. A particularly prominent group among the matrices most likely commissioned by Daubmann himself ca. 1550 is yet another cycle of gospel scenes. Vis-à-vis the series purchased from Guldenmund, and also that acquired from Sachse, this third set is distinguishable as having a much larger size—around 110 × 140 mm—which is suitable for publication in folio. In Nuremberg, Daubmann used this series between 1550 and 1553, namely in the postils by Johann Spangenberg and Caspar Huberinus, and also in a collection of passion sermons by Johannes Brenz (Fig. 3).23

Figure 3. Entry into Jerusalem. In SPANGENBERG. Postilla Teutsch (see note 23), fol. 1r (Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, 2Th Pr 220; https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb11204941?page=13; urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb11204941-3)

The individual scenes in the large set of woodcuts with gospel scenes were modelled on woodcuts from a popular series by Hans Brosamer. The latter recurred in various postils, beginning with Luther’s Church postil, published in Leipzig in 1544.24 The success of Brosamer’s designs specifically in Nuremberg comes as no surprise considering that the original blocks were used in the local printing house of Johann vom Berg and Ulrich Neuber from 1549,25 which points to the next direction of investigation regarding Daubmann’s network in Nuremberg.

Daubmann must have maintained close relationships with vom Berg and Neuber. They are likely to have provided Daubmann with inspiration concerning the design of the printer’s device. From the late 1540s, Daubmann used, among other title page borders in octavo, a frame with a medallion with a wild man, plausibly alluding to his name, which was occasionally written ‘Taubmann’. At that time, this meant not only ‘deaf’ but also ‘numb’, ‘stupid’ and ‘wild’, in a sense.26 The idea of including a personal device in a title page border was not original, but, in the local milieu, it was particularly prominent in vom Berg and Neuber’s printing house, as testified to by innumerable title page borders depicting the scene of Transfiguration on Mount Tabor alluding to vom Berg’s name (due to ‘Berg’ meaning ‘mount’ in German). Daubmann’s most widespread emblem, Christ as the Good Shepherd, produced in three sizes, appears to have been inspired by vom Berg and Neuber’s respective devices, especially regarding the smallest and biggest versions. However, the only instance of a woodblock recurring in both printing houses is the title page border featuring the Allegory of Law and Grace, employed by vom Berg and Neuber in 1550 and subsequently used repetitively by Daubmann in the early 1550s.27

Thus, by the spring of 1554, Daubmann had already accrued a substantial number of woodcut blocks of diverse sizes covering assorted thematic cycles and stemming from various sources. Still, compared to other Nuremberg printing houses, Daubmann’s equipment was certainly not exceptional, either in terms of quality or quantity. The question now arises as to which part of this stock he brought to Königsberg and how he developed his equipment in Prussia.

Königsberg

As in the case of the equipment used in his Nuremberg printing house, this investigation also examines books issued by both Daubmann and various other printers operating in Königsberg and elsewhere. Furthermore, one has to consider Daubmann’s heirs in Prussia, taking into account Georg Osterberger (1542–1602) and the subsequent generation consisting of Johann Fabricius (fl. 1593–1623) and Lorenz Segebade (1584–1638). To give just one, probably the most spectacular, example, in Daubmann’s prints issued either in Nuremberg or in Königsberg, I have so far never come across the letter Q from the series of ornamental initials he must have acquired from Guldenmund in 1547. It is rather implausible that the latter would keep a single letter from the alphabet for himself. A much more likely and perfectly reasonable alternative would be to assume that the letter Q was simply lost. This assumption is corroborated by the absence of this design in Osterberger’s prints as well. However, this was not the case here, as the letter Q from the discussed set unexpectedly reappeared in Königsberg only in the early seventeenth century, namely, in publications issued by Johann Fabricius.28

Nonetheless, various parts of Daubmann’s Nuremberg stock remain untraceable in Königsberg. Moreover, in some exceptional cases, there is not only negative but also positive evidence confirming that some woodblocks never arrived in Prussia. The most prominent example is that of the oldest series of 50 × 65 mm gospel scenes. Neither its nucleus cut in Dürer’s workshop in the early sixteenth century, nor the addenda plausibly commissioned by Guldenmund ca. 1530—both employed by Daubmann in 1548—recur in the latter’s Königsberg prints. This comes as no surprise considering that some woodblocks from this series were in a bad state in 1548. However, it would be premature to conjecture that they might have simply been destroyed or abandoned. In fact, more than two dozen of woodblocks that Daubmann had used in Nuremberg survived and may be found in the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin. They are part of the impressive collection of printing matrices which Hans Albrecht von Derschau purchased in Nuremberg in the late 18th century.29 (Fig. 4.)

Figure 4. Twenty four woodblocks used by Hans Guldenmund and Hans Daubmann in Nuremberg (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, Derschau 336,14; https://id.smb.museum/object/1922415/leben-christi%0D%0A24-st%C3%B6cke CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Moreover, some items from the discussed series were still in use after 1548, as revealed by examinations of some impressions, which demonstrate a higher degree of wear and tear than the illustrations in Daubmann’s 1548 publication. Suffice it to compare the broken-off sections of the frame of the Entry into Jerusalem in Daubmann’s publication and, for instance, in the exemplar in Albertina (inv. No. DG1961/27). (Fig. 5.) Admittedly, one cannot rule out that Daubmann himself, after he had printed Dietrich’s Kinderpredig in 1548, issued single prints from this series while still in Nuremberg. Nonetheless, the material evidence in Berlin confirms that he must have passed the set to yet another printer before leaving Nuremberg, also between 1548 and 1554.

Figure 5. Entry into Jerusalem (cf. Figure 1) (Vienna, Albertina, DG1961/27; https://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/?query=search=/record/objectnumbersearch=[DG1961/27]&showtype=record)

The two other gospel series, the one measuring 55 × 70 mm acquired from Sachse, and the 110 × 140 mm series plausibly commissioned by Daubmann himself, do recur in Königsberg. Concerning the former series, Daubmann incidentally utilised only single woodcuts (e.g., on title pages), and only Georg Osterberger employed significant parts of this cycle in a plenarium of 1587 and some also in Jonas Bretkūnas’s postil published in 1591.30 Interestingly, in these two publications issued by Osterberg, some scenes from Sachse’s set that are absent from Daubmann’s books may be found, thereby confirming that the above-mentioned phenomenon of not using the woodblocks remaining at a printer’s disposal should be taken into account not only as a purely theoretical possibility.31

In contrast, the biggest series of gospel scenes remains unaccounted for in Osterberger’s and his followers’ publications, after it had reappeared a few times in Daubmann’s Königsberg prints, beginning with Johannes Brenz’s collection of sermons mentioned at the outset as the publication that Daubmann presented as the first fruit of his printing house in Prussia. Scholars usually regard this publication as issued in Königsberg, before Daubmann was able to come to Prussia himself.32 One might consider another equally hypothetical scenario: Daubmann could have sent to Prussia some copies of the book printed in Nuremberg with the anticipated Königsberg address, diligently given on the title page, in the dedication and colophon. This conjecture might be indirectly corroborated by another example: Caspar Huberinus’s Spiegel der Hauszucht. As Gunther Franz posited, Daubmann brought to Königsberg some unsold copies of the Spiegel der Hauszucht originally printed in Nuremberg in 1553. Provided with a new title page, the publication was disseminated with Daubmann’s Königsberg imprint and the date 1555.33

It is tempting to consider a similar scenario with respect to Brenz’s sermons on the Resurrection and Ascension of Christ, allegedly printed in Königsberg in March 1554, especially considering the strict relationships between this publication and Brenz’s sermons on the Passion of Christ, printed by Daubmann in 1551 in Nuremberg. Both respective title pages have a similar layout decorated with Daubmann’s device and invariably inform the audience that, for the sake of pious readers unfamiliar with Latin, the work was decorated with illustrations,34 notably the assorted scenes from the 110 × 140 mm gospel series. Both publications provided dedications edited in a similar way, which was all the easier, as the dedicatees were brothers from the House of Hohenzollern. The Nuremberg collection was addressed to Georg Friedrich Margrave of Ansbach, whereas the Königsberg print was dedicated to Albrecht of Prussia. Finally, the Passion sermons conclude with Homilia 67, and the first sermon on the Resurrection and Ascension is labelled ‘Die erste Predigt und LXVIII Homilia’. These two publications were thus presented as a continuum and simultaneously two pillars of the bridge spread between Daubmann’s Nuremberg and Königsberg printing houses, regardless of—or, perhaps, despite—wherever the latter collection was actually printed.

The actual location of the 1554 collection’s printing remains obscure. The book’s woodcut decoration provides some intriguing but also equivocal hints. On the one hand, in both collections, an identical tailpiece concludes the dedication, representing a design absent in Daubmann’s Königsberg prints. One might thus conjecture that the sermons on Resurrection and Ascension were printed in Nuremberg. On the other hand, the woodcut figure after the dedication would suggest otherwise. In the 1554 publication, the verso of the page after the dedication is decorated with the coat of arms of Albrecht of Prussia, which replaced the full-page Crucifixion scene in the analogous place of the 1551 collection.35 Albrecht’s coat of arms was yielded from the matrix whose other user was, also in 1554, Aleksander Augezdecki—a Czech printer who ran a printing house in Königsberg at that time (Fig. 6).36

Figure 6. Coat of Arms of Albrecht of Prussia. In BRENZ. Von der Herrlichen Aufferstehung (see note 1) (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 2 Hom. 29#Beibd.1; https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10143871?page=6; urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10143871-2)

An obvious question arises regarding the precedence of using the woodblock with Albrecht’s coat of arms. Daubmann’s dedication to Brenz’s sermons on the Resurrection and Ascension bears the date of 19 March 1554. Augezdecki’s publication, decorated with the same woodcut, a hymnal translated into Polish by Walenty Brzozowski, includes the printer’s dedication dated 15 March 1554.37 This coincidence is intriguing as an omen of Daubmann’s and Augezdecki’s subsequent competition, but it also renders difficult a clear answer to the questions concerning the original owner of the block. The subsequent course of events remains completely obscure, as I could not identify any other impressions of this design hitherto. It seems rather unlikely that the block was commissioned by Daubmann in Nuremberg and brought by his agent to Prussia, where it was almost simultaneously used in two prints signed by Augezdecki and Daubmann, respectively. A tentative conclusion thus arises: the woodblock was commissioned by Augezdecki, who then lent or sold it to Daubmann’s agent in Königsberg. Either way, Daubmann soon stocked up on several designs and sizes of Albrecht’s coat of arms, beginning in September 1554, while, in subsequent years, he substantially enriched his stock of woodblocks in general.

In Königsberg, as in Nuremberg, Daubmann occasionally borrowed or repurchased blocks from other printers. An instance of an incidental loan was most likely the portrait of Johannes Draconites signed with the monogram HG, recurring in various editions of his works printed in Lübeck, Rostock and, by Daubmann, in Königsberg.38 An example of a repurchase is a series of elegant floral initials whose earlier impressions may be found in books printed in Königsberg by Hans Lufft. The latter, one of the most prominent Wittenberg printers, established a branch in Prussia in 1549, which he closed in 1553, just before Daubmann’s arrival. It is somewhat obscure what then happened with Lufft’s equipment, as the alphabet under discussion only reappears in Daubmann’s prints in the 1560s, as if it had remained unused for almost

a decade.39

In the 1560s, Daubmann commissioned a significant number of woodblocks. Some were individual scenes conceived to illustrate a particular work, such as an allegorical depiction of the relationship between Prussia and the Kingdom of Poland.40 Meanwhile, others were parts of series suitable to illustrate a specific work, as is the case of the Prussian Chronicle decorated with a set of coats of arms of the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Order. Furthermore, within this same period, Daubmann ordered a significant number of biblical scenes suitable to illustrate postils and catechisms in small formats of 4° or 8°, which coincides with the growing number of catechetical writings he published in various languages at that time.41 However, these biblical scenes are rather mediocre in terms of artistic quality and are unoriginal in design. For the most part, they follow the popular models from the 1540s, most notably the designs elaborated by Hans Brosamer and widely received in Europe, including Daubmann’s printing house, as the large gospel series demonstrates.

Conclusion

Early modern printers attached varied importance to illustrations and, consequently, adopted diverse strategies for acquiring and using woodcut blocks. At one end of the spectrum we may find the printers who were apparently completely insensitive to visual imagery, whereas, at the other end, we find those who evidently cared for the artistic quality of their publications and thus tirelessly ordered sets of woodblock diverse not only in terms of measures but also varied in design. In between are those who must have recognised the role of the illustrations but remained concerned with quantity rather than quality and followed the popular models rather than promoting original concepts. Daubmann’s practices are undoubtedly representative of this third, middle, group. His consistent strategy of repurchasing rather than commissioning new woodblocks reveals his intention to acquire the largest possible number of blocks at the lowest cost.

This approach was certainly understandable for the early years of his career. As a newcomer to the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg, Daubmann had no ‘founding capital’ of woodblocks. Assuming that he regarded illustrations as a means of attracting patrons, he made a reasonable choice to rely on systematic repurchases from various local and, occasionally, foreign sources. Significantly, however, his attitude regarding this practice did not change in Königsberg, where his professional position was diametrically different. In Prussia, he had a decent stock of woodblocks at his disposal and struggled with incomparably fewer worries in terms of both competition and the local power. He practically, and at some point also legally, monopolised the local print market, with his main patrons being the Duke of Prussia, Königsberg University and the Lutheran clergy. The latter were especially concerned with publishing religious literature not only in German and Latin but also in the local vernacular languages, most notably Polish, which created further opportunities, notably the opening of new markets in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Nevertheless, Daubmann’s strategy vis-à-vis illustrations did not change much, as he remained moderate in ordering new matrices while occasionally repurchasing or borrowing woodblocks from other printers. Even if he commissioned new woodblocks, they often followed well-established models.

The publication that symbolically concludes Daubmann’s activity in Königsberg is one of his most prominent undertakings, which also turned out to be his last, brought to an end only posthumously by his heirs in 1574: the Polish translation of Luther’s Hauspostille.42 At the same time, this publication proves the last record of the most prominent woodblocks Daubmann had brought from Nuremberg: the big series of gospel scenes after Brosamer, utilised consistently to illustrate the pericopes and the border with the Allegory of Law and Gospels found on the title pages of the second (summer) and the third (festival) parts of the collection. The main title page of the Polish translation of the Hauspostille, in turn, was decorated with another design: a depiction of Luther and the Elector of Saxony adoring a crucifix.43 This iconography, created in the mid-sixteenth century in the Wittenberg milieu of Hans Lufft, enjoyed considerable popularity in German editions of Luther’s writings but was unknown in the Duchy of Prussia until 1574. The direct model of the design on the title page of the Königsberg print was the woodcut employed multiple times by Lufft, beginning in 1551.44 The Polish translation of the Hauspostille thus symbolically captures Daubmann’s approach to book decoration: an inclination towards multiple reuses rather than commissioning new woodblocks and an attachment to popular, even heterogeneous, models, rather than an ambition to develop original patterns.

Reference list

Sources

1. BRENZ, Johannes. Von(n) der Herrlichen Aufferstehung vnd Himelfart vnsers Herrn Jhesu Christi. Königsberg: Daubmann, 1554, VD16: B 7930.

2. BRENZ, Johannes. Passio unsers Herren Jesu Christi. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1551. VD16: B 7796.

Secondary sources

3. ARP, Ingrid. Die Drucke aus der Offizin Hans Daubmanns im Spiegel der Konfessions – und Literaturgeschichte Königsbergs in der 2. Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts. Mit einer kommentierten Bibliographie. Magisterarbeit Germanistik, 2002, überarbeitete und erweiterte Fassung, Osnabrück 2011.

4. ARP, Ingrid. Hans Daubmann und der Königsberger Buchdruck im 16. Jahrhundert – Eine Profilskizze, In WALTER, Axel E. (ed.). Königsberger Buch- und Bibliotheksgeschichte, Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2004, pp. 87–126.

5. BIERENDE, Edgar. Demut und Bekenntnis – Cranachs Bildnisse von Kürfurst Johann Friedrich I. von Sachsen. In LEPPIN, Volker, SCHMIDT, Georg, WEFERS, Sabine (eds.). Johann Friedrich I. – der Lutherische Kurfürst. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2006, pp. 327–357.

6. DODGSON, Campbell. Holzschnitte zu zwei Nürnberger Andachtsbüchern aus dem Anfange des 16. Jahrhunderts. Berlin, 1909.

7. FRANZ, Gunther. Huberinus, Rhegius, Holbein: Bibliographische und druckgeschichtliche Untersuchung der verbreitesten Trostund Erbauungsschriften des 16. Jahrhunderts. Nieuwkoop: B. De Graaf, 1973.

8. GEISBERG, Max. The German Single-Leaf Woodcut: 1500–1550, revised and edited by Walter L. Strauss, vol. 1. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1974.

9. GRIEB, Manfred H. Nürnberger Künstlerlexikon. Bildende Künstler, Kunsthandwerker, Gelehrte, Sammler, Kulturschaffende und Mäzene vom 12. bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts. Munich, 2007.

10. HERBST, Klaus-Dieter (ed.). Bibliographisches Handbuch der Kalendermacher, vol. 3. Jena: Verlag HKD, 2020.

11. KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, Alodia; KOROTAJOWA, Krystyna (eds.). Drukarze dawnej Polski od XV do XVIII wieku, vol. 4: Pomorze. Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1962.

12. KORDYZON, Wojciech. Production of Vernacular Catechisms in Early Modern Königsberg (1545–1575), Its Dynamics and Goals Defined by the Print Agents. Knygotyra, 2023, Is. 80, pp. 147–174.

13. KROLL, Renate. Holzstöcke des 16. Jahrhunderts aus dem Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, In PIESKE, Christa e.a. (ed.). Arbeitskreis Bild, Druck, Papier. Tagungsband Kassel 1998. Münster: Waxman, 2000, pp. 29–38.

14. LOHMEYER, Karl. Geschichte des Buchdrucks und des Buchhandels im Herzogthum Preussen (16. und 17. Jahrhundert). Archiv für Geschichte der deutschen Buchhandels, 1896, t. 18.

15. NAGLER, Georg Kaspar. Die Monogrammisten und diejenigen bekannten und unbekannten Künstler aller Schulen…, vol. 3. Munich: Franz, 1863.

16. SCHÄFER, Bernd; EYDINGER, Ulrike; REKOW, Matthias. Fliegende Blätter. Die Sammlung der Eiblattholzschnitte des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts des Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein Gotha. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2016.

17. SCHOCH, Rainer; MENDE, Matthias; SCHERBAUM, Anna (eds.). Albrecht Dürer. Das druckgraphische Werk, vol. 3: Buchillustrationen. Munich: Prestel, 2004.

18. SCRIBNER, Robert W. For the Sake of Simple Folk. Popular Propaganda for the German Reformation. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994.

19. THOMAS, Drew B. The Industry of Evangelism. Printing for the Reformation in Martin Luther’s Wittenberg. Leiden: Brill, 2022.

20. TIMANN, Ursula. Untersuchungen zu Nürnberger Holzschnitt und Briefmalerei in der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Hans Guldenmund und Niclas Meldeman. Münster: Lit, 1993.

21. WEBER, Dmitrii I. Knigoizdatel’skaya deyatel’nost’ v Pribaltike XVI v. Iogann Daubmann – tipograf iz Kenigsberga. Cursor Mundi. Chelovek Antichnosti, Srednevekov‘ya i Vozrozhdeniya, 2016, t. 8, p. 218–228.

22. WEBER, Dmitrii I. Pamphlet as a means of a propaganda in Baltic Region in Early Modern Time. Vestnik SPbGU. Istoriya, 2017, t. 62/2, pp. 291–298. DOI: 10.21638/11701/spbu02.2017.206.

1 BRENZ, Johannes. Von(n) der Herrlichen Aufferstehung vnd Himelfart vnsers Herrn Jhesu Christi. Königsberg: Daubmann, 1554, [fol. 3]. Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachbereich erschienenen Drucke des 16. Jahrhunderts = VD16: B 7930.

2 On Daubmann’s printing house: KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, Alodia; KOROTAJOWA, Krystyna (eds.). Drukarze dawnej Polski od XV do XVIII wieku, vol. 4: Pomorze, Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1962, p. 70–92; ARP, Ingrid. Hans Daubmann und der Königsberger Buchdruck im 16. Jahrhundert – Eine Profilskizze, In WALTER, Axel E. (ed.). Königsberger Buch- und Bibliotheksgeschichte, Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2004, p. 87–126; WEBER, Dmitrii I. Knigoizdatel’skaya deyatel’nost’ v Pribaltike XVI v. Iogann Daubmann – tipograf iz Kenigsberga. Cursor Mundi. Chelovek Antichnosti, Srednevekov’ya i Vozrozhdeniya, 2016, t. 8, p. 218–228; WEBER, Dmitrii I. Pamphlet as a means of a propaganda in Baltic Region in Early Modern Time. Vestnik SPbGU. Istoriya, 2017, t. 62/2, p. 291–298; Unpublished MA thesis by Ingrid Arp (ARP, Ingrid. Die Drucke aus der Offizin Hans Daubmanns im Spiegel der Konfessions – und Literaturgeschichte Königsbergs in der 2. Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts. Mit einer kommentierten Bibliographie. Magisterarbeit Germanistik, 2002, überarbeitete und erweiterte Fassung, Osnabrück 2011) is rather unreliable in many respects, especially regarding the bibliographic annex.

3 THOMAS, Drew B. The Industry of Evangelism. Printing for the Reformation in Martin Luther’s Wittenberg, Leiden: Brill, 2022, esp. p. 108–165.

4 LOHMEYER, Karl. Geschichte des Buchdrucks und des Buchhandels im Herzogthum Preussen (16. und 17. Jahrhundert). Archiv für Geschichte der deutschen Buchhandels, 1896, t. 18, note 41.

5 HEURING, Simon. Almanach und Practica. Nuremberg: Daubmann [1547]. VD16: H 3288 (the only identified copy in London, British Library, C.54.a.6.[3.]); Practica Teutsch auf das M.D.XLVIII. Jar. Nuremberg: Daubmann [1547]. VD16: B 8426.

6 TIMANN, Ursula. Untersuchungen zu Nürnberger Holzschnitt und Briefmalerei in der ersten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Hans Guldenmund und Niclas Meldeman. Münster: Lit, 1993, p. 175; Daubmann (Taubmann), Hans (Johann) In GRIEB, Manfred H. Nürnberger Künstlerlexikon. Bildende Künstler, Kunsthandwerker, Gelehrte, Sammler, Kulturschaffende und Mäzene vom 12. bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Munich 2007, p. 242 (see also ibidem: Guldenmund, Hans, p. 530).

7 REISSNER, Adam. Ein schönes neues geistliches Lied zu singen in des Berners Weise. Nuremberg: Guldenmund, 1540, fol. A1r. VD16: R 1045; cf. Der beschlossen gart des rosen-

kra[n]tz marie, vol. 2. Nuremberg: Ulrich Pinder, 1505, fol. Cv, CCXXXVv, CCLXVIv and CCLXXIIIv. VD16: P 2806; PINDER, Ulrich. Speculum Passionis Domini Nostri Ihesu Christi, Nuremberg: Friedrich Peypus, 1507, fol. IXr. VD16: P 2807.

8 STAUPITZ, Johann. Libellus de Executione eterne predestinationis. Nuremberg: Friedrich Peypus, 1517. VD16: S 8702; STAUPITZ, Johann. Ein nutzbarliches büchlein von der entlichen volziehung ewiger Fürsehung, transl. Christoph Scheurl. Nuremberg: Friedrich Peypus 1517. VD16: S 8703; Richardus de Sancto Victore. De Trinitate libri sex. Nuremberg: Friedrich Peypus, 1518. VD16: R 2155.

9 BRUNFELS, Otto. Der Christen Practica. Nuremberg: Guldenmund, 1545. VD16: ZV 16166.

10 BRUNFELS, Otto. Der Christen Practica, Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1548. VD16: B 8484.

11 Letter E in LINK, Wenzeslaus. Eyn Sermon von geistlichem und weltlichem Regiment. Nuremberg: Guldenmund, 1536, fol. A2r. VD16: L 1833; letter L in Eyn Veldtgeschrey des Almechtigsten un unüberwindtlichsten Keysers. Nuremberg: Guldenmund, 1536, fol. A2r. VD16: F 698; letter Q in KÖRBER, Otho. De Consolantissimo usu, Istorum verborum Christi, Nuremberg: Guldenmund, 1536, fol. A1v. VD16: ZV 18009.

12 GEISBERG, Max. The German Single-Leaf Woodcut: 1500–1550, revised and edited by Walter L. Strauss, vol. 1. New York: Hacker Art Books, 1974, Nos. 974 and 976. Wolfgang, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken with Guldenmund’s address: Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Graphische Sammlung, Inventar-Nr. H 4697, Kapsel-Nr 46; with Daubmann’s address: London, British Museum, inv. No. 1927, 1008.400; Georg von Leuchtenberg with Guldenmund’s address: Austin, TX, Harry Ransom Center, 388, box 10; with Daubmann’s address: Berlin; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinet.

13 Copy with Daubmann’s address: Gotha, Schloss Friedenstein, inv. No. G42,5 reproduced in SCHÄFER, Bernd, EYDINGER, Ulrike, REKOW, Matthias. Fliegende Blätter. Die Sammlung der Eiblattholzschnitte des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts des Stiftung Schloss Friedenstein Gotha. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2016, p. 104; cf. an almost identical design from another woodblock, also with Cranach’s device: GEISBERG. The German Single-Leaf Woodcut, No. 662.

14 First described by DODGSON, Campbell. Holzschnitte zu zwei Nürnberger Andachtsbüchern aus dem Anfange des 16. Jahrhunderts. Berlin, 1909, then discussed several times, most recently in SCHOCH, Rainer, MENDE, Matthias, SCHERBAUM, Anna (eds.). Albrecht Dürer. Das druckgraphische Werk, vol. 3: Buchillustrationen. Munich: Prestel, 2004, p. 512-23, cat. No. A.38.1–43.

15 DIETRICH, Veit. Kinderpredigt. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1548. VD16: D 1573.

16 London, British Museum, inv. No. 1909,0403.5.

17 Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, shelf mark Libri impr. rari oct. 162; VD16: ZV 30893.

18 HUBERINUS, Caspar. Der Catechismus mit viel schönen sprüchen der heiligen schrifft gegründet. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1549. VD16: H 5371.

19 BROTBEIHEL, Matthias. Practica Teutsch auf das M.D.XLVIII. Jar. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1547. VD16: B 8426; Planeten Büchlein. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1549 (copy in Moscow, Margarita Rudomino All-Russia State Library for Foreign Literature, shelf mark R R 336 Allig.); Schreib Kalender … auff das Jar Christi MDLIII. Nuremberg: Daubmann 1552, noted by HERBST, Klaus-Dieter (ed.). Bibliographisches Handbuch der Kalendermacher, vol. 3. Jena: Verlag HKD, 2020, p. 15.

20 Artzneybuch. Erfurt: Sachse, 1546. VD16: A 3872; Artzneybuch. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1549. VD16: A 3873.

21 DIETRICH, Veit. Summaria Christlicher Lehr. Erfurt: Sachse. VD16: D 1631; CAELIUS, Michael. Ein Danck, Beicht und Betbüchlein. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1550. VD16: C 1820. The set included an earlier scene with three men counting at the table, originally on the title pages of a treatise on accounts: RIES, Adam. Rechnung auff der Linien und Federn. Erfurt: Sachse, 1529. VD16: R 2364; subsequent editions in 1533 – VD16: E 2369, and 1537 – VD16: R 2374. Subsequently, both Sachse and Daubmann used this scene to illustrate the Parable of the Unjust Steward.

22 See note 6.

23 SPANGENBERG, Johann. Postilla Teutsch. Nuremberg: Hans Daubmann, 1550. VD16: ZV 26781; HUBERINUS, Caspar. Postilla Teutsch. Nuremberg: Hans Daubmann, 1552–1553. VD16: H 5396–5398; 5400; BRENZ, Johannes. Passio unsers Herren Jesu Christi. Nuremberg: Daubmann, 1551. VD16: B 7796.

24 LUTHER, Martin. Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien. Leipzig: Nikolaus Wolrab, 1544. VD16: L 5605–5606; KNAUER, Martin. Hans and Martin Brosamer, KAULBACH, Hans-Martin (ed.). Oudekerk aan den IJssel 2015, No. 1001–1062 (The New Hollstein German Engravings, Etchings and Woodcuts, 1500–1700).

25 LUTHER, Martin. Haußpostil. Nuremberg: vom Berg and Neuber, 1549. VD16: L 4847.

26 ‘TAUB, adj.’ In Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm, digitalisierte Fassung im Wörterbuchnetz des Trier Center for Digital Humanities, Version 01/21, <https://www.woerterbuchnetz.de/DWB?lemid=T01302>, accessed: 10 September 2022.

27 Biblia. Das ist: die gantze heylige Schrifft: Deudsch. Nuremberg: vom Berg and Neuber, 1550. VD16: ZV 1483; HUBERINUS, Postilla Teutsch (see note 23).

28 HALBACH, Daniel. Collegium Ethicum Doctrinam Aristoteleam. Königsberg: Fabricius, 1618. VD17: 1:066038H; LOTH, Georg. Disputatio Problematica. Königsberg: Fabricius, 1621. VD17: 5119:741729K.

29 Berlin; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, inv. Nos Derschau 051; Derschau 336, 14 (24 items); Derschau 485; KROLL, Renate. Holzstöcke des 16. Jahrhunderts aus dem Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, In PIESKE, Christa e.a. (ed.). Arbeitskreis Bild, Druck, Papier. Tagungsband Kassel 1998, Münster: Waxman, 2000, p. 29–38.

30 Evangelia und Episteln, aus dem deutschen in undeutsche Sprache gebracht. Königsberg: Osterberger, 1587; BRETKŪNAS, Jonas. Postilla tatai esti trumpas. Königsberg: Osterberger, 1591. VD16: ZV 2454.

31 Daubmann apparently never used the Temptation of Christ and the Journey to Emmaus, both known from DIETRICH, Summaria (see note 21), fol. D6r and F2v and recurring in Evangelia und Episteln…, Königsberg: Osterberger, 1587, fol. G4v and O2r. Interestingly, in Bretkūnas’s postil, Osterberger used another Temptation of Christ, earlier attested in CAELIUS, Ein Danck, Beicht und Betbüchlein (see note 21), fol. H4v; Osterberger also employed another Journey to Emmaus, unattested in earlier Daubmann’s publications.

32 LOHMEYER. Geschichte (see note 4); cf. KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, KOROTAJOWA, Drukarze dawnej Polski (see note 2), p. 71.

33 FRANZ, Gunther. Huberinus, Rhegius, Holbein: Bibliographische und druckgeschichtliche Untersuchung der verbreitesten Trostund Erbauungsschriften des 16. Jahrhunderts. Nieuwkoop: B. De Graaf, 1973, p. 62–63. Daubmann’s edition of 1553 is unacknowledged in VD16; Daubmann’s Königsberg edition of 1555 – VD16: B 4088.

34 BRENZ, Vonn der herrlichen Aufferstehung (see note 1).

35 This Crucifixion design appears isolated in Daubmann’s production in general.

36 Augezdecki was active in Prussia from 1549 to 1558, when he moved to Szamotuły in Greater Poland – KAWECKA-GRYCZOWA, KOROTAJOWA, Drukarze dawnej Polski (see note 2), p. 19–28.

37 Cantional Albo Księgy chwał Boskych, transl. Walenty Brzozowski. Königsberg: Augezdecki, 1554.

38 DRACONITES, Johannes. Eine Trostpredigt Von der Christenheit: Uber der Leiche: Eulalia von der Marthen M. Capels Gemahel. 14. Februarij. 1547, Marburg: Andreas Kolbe, 1547. VD16: D 2518; DRACONITES, Johannes. Gottes Verheissunge Von Christo Jesu, Lübeck: Georg (II) Richolff, 1549. VD16: D 2495; DRACONITES, Johannes. Von dem Bunde Gottes mit der Christenheit. Rostock: Ludwig Dietz, 1552. VD16: ZV 4723; DRACONITES, Johannes. Die Passio Jesu Christi: nach den vier Evangelisten ausgeleget, Königsberg: Hans Daubmann, 1561. VD16: D 2510. NAGLER, Georg Kaspar. Die Monogrammisten und diejenigen bekannten und unbekannten Künstler aller Schulen…, vol. 3. Munich: Franz, 1863, No 947.

39 Among other publications, this set was used extensively in MĄCZYŃSKI, Jan. Lexicon Latino-Polonicum. Königsberg: Daubmann, 1564. VD16: M 55.

40 SOLIKOWSKI, Jan Dymitr. Prussia regi optimo maximo, patri patriae foelicitatem. Königsberg: Daubmann, 1566.

41 KORDYZON, Wojciech, Production of Vernacular Catechisms in Early Modern Königsberg (1545-1575), Its Dynamics and Goals Defined by the Print Agents, Knygotyra, 2023, t. 80, p. 147–174.

42 LUTHER, Martin. Postilla domowa, transl. Hieronim Malecki, Königsberg: Heirs of Hans Daubmann, 1574 (VD16: L 4901).

43 SCRIBNER, Robert W. For the Sake of Simple Folk. Popular Propaganda for the German Reformation. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1994, p. 221; BIERENDE, Edgar. Demut und Bekenntnis – Cranachs Bildnisse von Kürfurst Johann Friedrich I. von Sachsen. In LEPPIN, Volker, SCHMIDT, Georg, WEFERS, Sabine (eds.). Johann Friedrich I. – der Lutherische Kurfürst. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2006, p. 327–357.

44 LUTHER, Martin. Der Erste Teil Der Bücher D. Mart. Luth. Wittenberg: Lufft, 1551. VD16: L 3313.