Knygotyra ISSN 0204–2061 eISSN 2345-0053

2025, vol. 84, pp. 177–197 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Knygotyra.2024.84.7

Written Knowledge and its Impact on the Advancement of Society: Kosovo Case

Jehona Shala

Department of Literature, Faculty of Philology, University of Prishtina

E-mail: jehona.shala@uni-pr.edu

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0346-325X

https://ror.org/05t3p2g92

Summary. The history of publishing books in Albanian in Kosovo covers the same period as the cultural, educational and political institutionalization of the Albanian society of Kosovo. This parallel development between the book and the institutions made the publishing culture and the institutional culture grow side by side and help mature each other. Therefore, for the Albanian culture in Kosovo, the development and profiling of the book, publishing and publishing houses have a special value because it was only through the book that Kosovo Albanians could be a special cultural and social voice in the Balkan region. Given the importance that the book in Albanian has had for Kosovo Albanians, this article explores the history of Albanian book publishing in Kosovo and its significant impact on the cultural, educational, and institutional development of Albanian society in the region. Despite the lack of a comprehensive understanding of the origins and evolution of Albanian book publishing in Kosovo, this research aims to construct a detailed chronology of its development, including the establishment of the first publishing houses, and to analyse the influence these developments have had on Albanian society. Through the statistical bibliographic method, we will not only recount the history of Albanian book publishing but also uncover insights into the typology of publishing, which has evolved over the decades.

Keywords: Kosovo, Albanian book, Albanian book history, printing houses, publishers.

Rašytinės žinios ir jų poveikis visuomenės pažangai: Kosovo atvejis

Santrauka. Straipsnyje yra nagrinėjama albaniškų knygų leidybos Kosove istorija bei jos įtaka albanų tautinės bendruomenės kultūrinei, švietimo ir institucinei raidai regione. Kadangi trūksta išsamių, visapusiškų, visą vaizdą atspindinčių tyrimų apie albaniškų knygų leidybos ištakas ir raidą Kosove, šiuo tyrimu siekiama šią spragą užpildyti ir atskleisti išsamią leidybos raidos chronologiją, įskaitant pirmųjų leidyklų įkūrimą, bei išanalizuoti albaniškų knygų leidybos įtaką albanų visuomenei. Tokiam tikslui pasiekti autorė pasitelkė statistinį bibliografinį metodą, kuris leido ne tik atskleisti albaniškų knygų leidybos istoriją, bet ir pastebėti leidinių tipologijos pokyčių tendencijas, vykusias pastaraisiais dešimtmečiais.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: Kosovas, albaniška knyga, albaniškos knygos istorija, spaustuvės, leidėjai.

Received: 2024 03 08. Accepted: 2025 05 23.

Copyright © 2025 Jehona Shala. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Political and cultural histories in Balkan countries have almost been two inseparable entities, and so they have, consequently, gained or suffered from each other. Kosovo, as part of the region, has also been subjected to the political pressure of the time and, as a result, suffered in terms of the development of culture, especially in terms of Albanian written and published culture. Having not enjoyed the right to publish, Kosovo started its book publishing journey late compared to other countries of the region. Respectively, the year 1943 is the year that marks the first publication in Albanian in Kosovo. Therefore, we will start this article – which discusses the publishing of Albanian books in Kosovo – with a cultural and historical overview, in order to apprise the reader of reasons why Kosovo began publishing in the Albanian language so relatively late. The goal is to address further the history of the publication of books in Albanian in particular and its impact on the cultural and educational growth of Kosovo Albanians, accompanied by statistical data on the publication of Albanian books from 1943 to 1993. The year 1943 is the year when the first publication in Albanian in Kosovo was documented, and therefore this year represents the beginning of Albanian publishing in Kosovo.

The publishing period discussed here not only covers half a century of publications, but it rather relates more to the cultural milieu of publishing as a starting point and as a development under the dome of a large political administration, specifically, Yugoslavia, an integral part of which was Kosovo too. The half century of publications that are dealt with herein, along with the cultural and political context and the impact that the right to publish had on Kosovo’s society, are the fundamental topics of this research. The year 1993 marks the final closure of publication of books in Albanian under the Yugoslav cultural and political dome, the dissolution of publishing institutions due to political circumstances, and the emergence of private publishers in Kosovo. Thus, we are talking about a cycle of publications that directly helped develop the Albanian culture and education in Kosovo, a cycle that helped create a tradition, a tradition that was easier to sustain as opposed to the time when publications began.

Aim and objectives of the research: If we acknowledge the idea that the job of thinking about the world exists thanks to books and reading1 as true, it will allow us to reflect on the great impact that the publication of books in Albanian has had on the Albanian society in Kosovo. Owing to publishing and, as a result, reading and thinking, Albanian society in Kosovo has advanced from an isolated and rhapsodic society to an open and developed society. The opening of the society introduced herein through a presentation of the publishing history, parallel to the cultural context and the trajectory of cultural and educational enhancement of Albanian society in Kosovo, is among the main goals of this research, which, in itself, is a factual representation of how a society thinks, develops, and advances thanks to reading. Given that this is the first study of the kind in the study of culture of publishing, we have tried to provide concrete evidence of publications from a year to another, hence providing, for the first time, data on publications in Albanian in Kosovo. Numerical tables included herein do not indicate the trajectory of the growth of publishing alone, but also the trajectory of the growth of every field of culture and education related to books and written knowledge, so this article also contains names of Kosovo intellectuals and writers who were simultaneously carriers of the publishing culture and historical responsibilities in Kosovan society. Accordingly, we consider that this research will become a reference point for subsequent studies on publications in Albanian in Kosovo and serve as a valuable example to provide argumentation regarding the power of written knowledge in a society.

Methodology: This research focuses on the statistical bibliographic method, extracting numerical data regarding the publication of Albanian books in Kosovo, the establishment of the first publishing houses, and the various types of publications. It examines their growth over the years and cross-references these findings with historical sources related to the cultural, educational, and institutional development of Albanian society in Kosovo. Through an analysis of nearly 10,000 bibliographic units of books published in the Albanian language in Kosovo, encompassing both translations and original works by Albanian authors from within and outside Kosovo, we have successfully identified the publication of the first Albanian primer intended for first-grade students. This analysis also highlights the origins of the Albanian literature in Kosovo, the initial translations from world literature, preschool textbooks, the first university textbooks, the inaugural illustrated publications for children, and the first publications in Braille, among others. In addition to quantifying the number of publications, which we have presented in the tabular form, we have also uncovered the beginnings of various publication typologies that statistically correlate with the development of Albanian schools in Kosovo and the establishment of the University of Pristina.

Sources and preliminary studies: A study of this kind is the first in Albanian culture in Kosovo, using bibliographies2 on Albanian publications in Kosovo and publishing house catalogues3 as main sources. The bibliography of 1944–1956, published in the Përparimi cultural magazine, is among the most reliable bibliographical materials regarding the topic; as it serves the basis for the National Bibliography of Albanian Books in Kosovo: 1912–1999, which has undergone a phase of editing by specialist bibliographers from the National Library of Kosovo and the Central University Library of the University of Pristina. Bibliographies and catalogues have been a valuable source to introduce the reader to the first edition of a primer, the first edition of textbooks, the first original literary publication, the first literary translations, the first university publications, etc. On the other hand, two other articles that are related to the topic of Albanian publishing in Kosovo: Albanian Books and Libraries in Kosovo4 and Publishing in Kosova/Kosovo5 are papers dealing with the beginnings of publishing in Albanian in Kosovo which direct the discussion more towards the communication between books and libraries than towards the history of publishing or the nature of publishing, and they seem more like meta-studies on books and library than a direct research based on original sources like bibliographies or catalogues. The second article – which is valuable for the historical information it provides on the development of culture of publishing in Kosovo, while discussing publishing as an industry – focuses on publications after the 1990s, by paying more attention to a broader context of the publishing culture, be it books or newspapers, rather than historical studies, with concrete data and the researcher’s direct encounter with the phenomenon of publishing and its impact on society.

Cultural and historical overview of Kosovo

In its current borders, Kosovo has existed, more or less, since 1945.6 Before these years, Kosovo’s borders were at times ethnic, and at other times political.7 This has also had an impact on the composition of Kosovo population, which is why, even nowadays, Kosovo remains rich in population belonging to various ethnic backgrounds, like most of the South-Eastern European countries,8 i.e., ethnic groups that had, inevitably, linguistic and cultural ties with their neighbouring countries, like Albania, Serbia, Macedonia and Montenegro. Given that the majority of Kosovo’s people are of the Albanian ethnicity, their linguistic and cultural ties with Albania, especially with the North of Albania, were natural, because of both geographical proximity and ethnological and anthropological similarities, but also because of coexistence of Albanians over various periods of history, coexistence that became more difficult after 1912–1913, when, as a result of political decisions made by the Great Powers, Kosovo remained outside the map of the state of Albania.9 Therefore, even today, the Albanian culture is, in its genesis, only taught and dealt with as an Albanian culture, oblivious of geographical differences.

As of 1945, Kosovo became part of the Yugoslav Confederation and got the status of an autonomous unit within Serbia. At that time, it began to lay its cultural and institutional foundations, separate from the cultures of the neighbouring countries, which had dominated Kosovo until 1945. Currently, Kosovo has been an independent State since 17 February 2008.

Given that publications in the Albanian language in Kosovo are subject of treatment herein, we will present a brief cultural panorama of Kosovo and, in parallel, some overtones of the historical context in which Kosovo Albanians have lived, so as to create a clearer picture of the importance of initial publications in Albanian and the consolidation of publishing production in Kosovo.

Given that the Albanian language did not have its own alphabet until 1908, when the Congress of Manastir, Congress of Unification of the Alphabet of Albanian Language,10 was held, the adaptation of foreign alphabets had been, in terms of writing, a practice for a long time, due to the dominance of the prevailing cultures of the time. Accordingly, the Albanian language was strongly preserved as a spoken language and as a language of the popular culture. The two biggest influences were the Latin culture, as in most of Europe, and the Oriental culture, following the conquest by the Ottoman Empire. Under these circumstances, in religious schools, such as mejteps or madrasahs, students of the Muslim faith were being taught in Arabic by Muslim clerics, whereas Latin was being when working with students of the Christian faith. It was under these circumstances that the first Albanian schools and intellectuals of Kosovo also stood out.

Though Catholic clergy schools were closed by the Ottoman authorities in the second half of the 17th century, proofs of Catholic clergy writings in Albanian have survived to the present day. The Bend of Prophets,11 authored by Pjetër Bogdani from Has, Prizren, published in Albanian and Italian in 1685 in Padua, Italy, bears proof of that. The tradition of the Catholic clergy of the 17th century was followed by their successors. The most famous of them is the Franciscan friar, Shtjefën Gjeçovi, who is mostly known for the collection of the Albanian customary code, Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit [en. Code of Lekë Dukagjini], which was published in full in 1933 in Albania (in Shkodër), already after his murder in 1929, at the age of 56, at a time when writing and publishing Albanian texts in Kosovo was deemed a violation of law, given that publishing in Albanian was prohibited in 1920–1930.12 Shkodër was a cultural centre for Kosovo and the entire North of Albania. This is also proven in the texts written by Hasan Prishtina, a prominent intellectual from Kosovo, who in 1921 published his work entitled Nji shkurtim kujtimesh mbi kryengritjen shqyptare të vjetit 1912 [en. Brief Memoir on the Albanian Uprising of 1912].13

It is based on these facts that historians’ findings that in the history of the writing of the Albanian language, Kosovo occupies a peripheral place becomes meaningful. Literate Muslims used Ottoman/Turkish, while Christians (including non-Serbs) used Serbian (Catholics were also using Italian). Therefore, until the time of the mass literacy of the population after 1945, Albanian was a language that was cultivated mainly orally, and it was dominated by Ottoman and Serbian as written languages.14

Due to finding themselves in these complex circumstances, Kosovo Albanians were forced to preserve their language and culture through oral culture until the 20th century. Folk songs or stories were created and passed down from one generation to another through memory. Paradoxically, what had happened with the work of Homer in antiquity was being applied by a small people in the Western world even in the 20th century. The people of Kosovo – who were not allowed to write in their own language – had found the language of communication through folklore: it was the song, especially the rhapsodic song, that taught generations about authentic legends and myths, about historical events, about love of bravery, ethics and canonical norms. Whereas, the popular culture, especially the song, became the main cultural and educational institution, which manifested the life of Kosovo Albanians in all its colours. It was through songs and popular culture in general that cultural and historical awareness of Kosovo Albanians was shaped.

Fortunately for Kosovo Albanians, that situation changed after World War II. The first publication in Albanian appeared in Kosovo in 1943, even before the war was over, and the situation improved after the end of the war in terms of publications and, consequently, schools in the Albanian language were opened all over the country, given that until the days of the capitulation of the old Yugoslavia, the Albanian population not only had no schools and books in the Albanian language, but did not even dare to read anything in their mother tongue.15 That contributed to the inception and stabilisation of publishing in the Albanian language and paved the way for Kosovo to create and represent its authentic culture.

The Albanian book in Kosovo – a brief history

Although the beginning of publishing in the Albanian language in Kosovo can be related to the need for political propaganda, since the first text recorded as a publication in the Albanian language in Kosovo in 1943 is an article by Josip Broz Tito entitled Çështje nacjonale në Jugosllavi në dritën e Luftës Nacional-Shlirimtare [en. National Issues in Yugoslavia in the Light of the National Liberation War],16 such propaganda was more acceptable to Kosovo Albanians, for it entailed more an inclusion than a reality in which they lived, which was basically an exclusion until those years.

The history of publications in the Albanian language in Kosovo began with that article, mimeographed in 120 copies, and it was with thousand troubles and dangers, almost at gunpoint,17 that the Proleter Issue 16, v. XVIII of the Serbo-Croatian edition dealt with in December 1942, and then it was translated into Albanian and multiplied in the first quarter of 1943.18 The article not only marks the first Albanian publication in Kosovo, but also a break from the cultural isolation of Kosovo Albanians, an isolation that was overcome owing to the need for political propaganda. Today we only have a facsimile of that edition, presented in the catalogue of publications of the Rilindja Publishing House.

Two other articles, also translated, came out after Tito’s 1943 article: one of these was a historical article on the Communist Party, whereas the other was a text with fragments from Çështje të leninizmit [en. Matters of Leninism].19 In 1944, 4 more articles were published, also translated and published in Pristina by the Provincial Committee of the Yugoslav Communist Party for Kosmet, mimeographed by the Technical Joint National Liberation Front of Kosmet, each in a print run of 500 copies.20

In 1944, a press and book distribution institution for the territory of Kosovo was also founded in Kosovo: Agitprop of Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia for Kosmet. Agitprop and Kosmet – as an explanation for the reader – is a combination of words: for the first – Agitation and Propaganda, whereas for the second – Kosovo and Metohija. It appears that this institution ended its mission in the wake of the war, because it was no longer mentioned as a publishing institution afterwards. The prominent publishing institutions succeeding the latter included the Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia for Kosmet, which issued publications on politics and seems to have operated under that name from 1944 to 1946, and the Educational Directorate for Kosmet, under whose signature My First Singing21 or the first Albanian Primer in Kosovo was published. In 1945, the Educational Directorate for Kosmet was named the Educational Directorate of Provincial People’s Council for Kosovo and Metohija and it was renamed again as the Kosmet State Publishing House in 1946. In 1945, the first printing house for publications in Albanian was established in Kosovo, and its name in the publications of the time appears in two variants: the State Press and the State Printing House, which was ultimately named the Progress Printing House in 1947.

While 1943 and 1944 are the years marking the beginning of publishing in Albanian in Kosovo, 1945 is the year that marks the publication of the first textbook in Kosovo, entitled Këndimi im i parë [en. My First Singing]. That primer, prepared by the Educational Directorate for Kosmet, in Prizren, and printed in the Luarasi printing house in Tirana, was published in 20,000 copies. A total of 17 texts were published that year, 13 of them mimeographed and 4 of them printed, 1 in Tirana – as we saw above – while the other 3 were printed at the State Printing House in Prizren.

With the exception of the two texts: Këndimi im i parë [en. My First Singing] and Metodë për mësimin e gjuhës Shqipe, fëmijëve 5-7-vjeçarë [en. Albanian Language Teaching Method for 5–7-Year-Old Children), authored by Ibrahim Riza, all other texts were translated texts of a political nature. As of 1946, a total of 16 Albanian publications were registered, among them Abetare për të rritun [en. Primer for Adults], published in Prizren by Educational Directorate of the Provincial People’s Council for Kosovo and Metohija, printed at the State Printing House, with a press run of 50,000 copies.

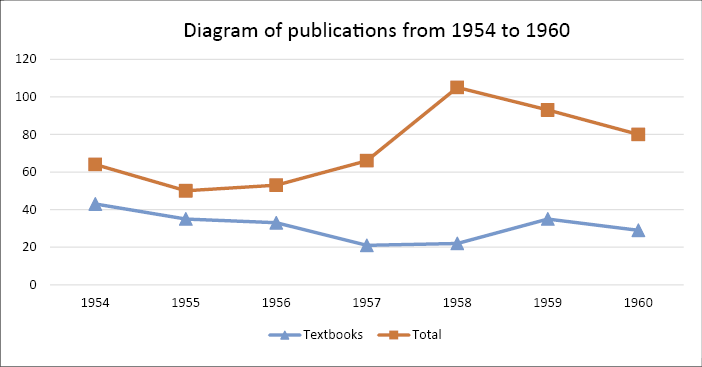

The other texts are, as in the previous year, political texts for and about the Communist Party. This is roughly the nature of the publications of 1947: out of 19 books published in that year, 4 of them were textbooks, one of them a primer, with a print run of 50,000 copies, and a book of poems dedicated to the school age, titled Vjersha për shkolla fillore e paragjimnaze [en. Poems for Primary and Pre-Gymnasium Schools], published in Pristina by the Pedagogical Commission, the first of its kind published in Kosovo by a professional commission, which indicates that not only the publication of books, but also the thematic horizon were expanding, and which thus signals the fact that the mission of the book was not only academic or political, but attractive too. It turns out that 34 book titles were published in the Albanian language in 1948, 10 of them were textbooks with a print run of 30,000–50,000 copies for the elementary school level, while Abetare për të rritun [en. Primer for Adults] was reprinted in 100,000 copies. The translation of literary texts, be they literature for children or adults, began in this period. In 1949, the number of publications in the Albanian language doubled compared to the previous year, reaching 71 books, 17 of them textbooks, and it was for the first time in 1949 that school publications for the secondary school level or, as they are known in Kosovo, high-school textbooks, were published. This was the highest number of textbooks published in the post-war decade. The figures were similar in 1948: it turns out that 78 titles were published, of which 11 were textbooks. Surprisingly, the number of publications began to decline in subsequent years. However, compared to previous publications, the publication of textbooks increased year-by-year in the 1950s: there were 59 titles published in Albanian in 1951, and 14 of them were textbooks for primary and secondary levels. 42 publications were registered in 1952, 23 of them textbooks, among them Këngë popullore shqiptare [en. Albanian Folk Songs], in two editions. 54 books were published in the Albanian language in 1953, 24 of which were textbooks. We have approximate figures of publications in the following years, while in 1958 the number of publications in Albanian language exceeded 100.

In counting publications in Albanian, the textbooks were divided for the purpose of analysing parallelism of publications, because, until those years, more than a half of the publications in Albanian were political textbooks, and the rest were school textbooks. There was a dire need for textbooks, because Kosovo students did not have the luxury of learning in their mother tongue until the end of World War II. The few people who were educated attended classes in Serbian and, therefore, studied with Serbian texts. Accordingly, to Kosovo Albanians, the right to receive education in the Albanian language and learn from Albanian books, let alone written by Kosovo authors, was impossible and unimaginable as little as two decades earlier. Thus, the right to read, learn and write Albanian in Kosovo contributed not only to the stabilization of publishing institutions, but also to the cultural consolidation of Kosovo. It rendered laying the foundations of the Albanian culture in Kosovo possible. In these years, Kosovo Albanian authors began to publish literary works, and, as a result, in 1953, we have the first poetic work titled Nji fyell ndër male [en. A Flute in the Mountains], written by Martin Camaj, who is considered as the pioneer of Albanian poetry in Kosovo.22 The first novel titled Rrushi ka nisë me u pjekë [en. Grapes have Started to Ripen], authored by Sinan Hasani, was published in 1957. The first children novel titled Lugjet e Verdha [en. Yellow Vales], authored by Rexhep Hoxha, was published in 1959. Works from Yugoslav literature were also being translated and published in Albanian, and short versions of works by Victor Hugo, Jack London and Mark Twain were also translated later on. Kosovo was communicating with the world culture and manifesting it through translations of publications in Albanian. Though, the number of books published in the 1950s was not that high, and even those that were published in Albanian were mostly translated texts. For example, as indicated in an analysis of publications from 1943 to 1963, over 50% of publications were translations, mainly from Serbo-Croatian. Out of 1230 texts published from 1943 to 1963, 655 were translations, not counting political propaganda texts that are likely translations but do not contain the authorship of the translator. There were multiple translated texts even after these years, especially among school textbooks, which were also translated and used in teaching in accordance with a curriculum that was applicable across the former Yugoslavia.

Certainly, those publications were still valuable on account of cultural signs that they were offering and owing to the fact that the publishing of Albanian books was creating its own tradition, separate from other cultures in Yugoslavia. Therefore, the subsequent period of the 1960s transformed the nature of publications on behalf of the local culture. In this period, there was a return to the cultural connection with Albania, thus restoring the communication with the Albanian literary tradition, which had been natural until 1912. The Rilindja Publishing House published the works of authors of Albanian romanticism or, as it is known in the Albanian culture, the National Renaissance, i.e., authors like: Jeronim de Rada (1967), Naim Frashëri (1968), etc., and the works of the two most popular modernists of the Albanian literature, Mitrush Kuteli and Lasgush Poradeci (1968). The literary works of the world’s most famous authors were translated and published, such as those by: Ivan Turgenev (1967), Albert Camus (1968), William Shakespeare (1968), Dante Alighieri (1969), Fyodor Dostoevsky (1970), Samuel Beckett (1970), Ernest Hemingway (1970), etc.

At the beginning of this decade (in 1962), non-mandatory textbooks, which were still related to the curriculum, known as School Reading Materials, came to light. In the same decade, in 1967, Bazat e Sociologjisë së Përgjithshme [en. Basics of General Sociology], which turns out to be the first text associated with the university text nomination, was published. The first book in the Braille alphabet was published in 1974. The first illustrative texts dedicated to pre-schoolers were published in 1976. Thus, publishing was expanding its horizon, and becoming available for use for all of the residents.

Seen from today’s perspective, the freedom to write, translate and publish in Albanian helped advance the Albanian culture and society in Kosovo immensely.

Every decade after 1943 – when the first Albanian publication in Kosovo came out – brought about positive changes in the field of publications. Publications increased year by year, and publishing houses became more and more profiled. For instance, if, in the first years of publishing in Albanian, textbooks were issued by the Educational Directorate or Pedagogical Committee within that directorate, or even by the Belgrade Enterprise for Textbooks and Learning Tools of People’s Socialist Republic, which published almost all the textbooks in the Albanian language in Belgrade (this publishing house is also known as the Institute of School Publications of Serbia and the Institute of Textbooks and Teaching Aids of Serbia), a sub-branch of this publishing house was established in 1964, in Pristina, under the name of Department of Pristina and, in late 1969, that department became the main institution for school publications in the Albanian language in Kosovo and was named the Institute of Textbooks and Teaching Aids of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, based in Pristina, Kosovo.

A similar trend of growth and profiling was followed by other publishing houses in Kosovo. This becomes even more evident if we try to take a look at the history of publishing houses for non-school texts that were produced by the Progress Publishing House and Printing House, based in Pristina, which started to operate in Pristina in 1947 and continued as such until 1950. From 1950, the Mustafa Bakija Publishing House took the lead in publishing in Kosovo, and cooperated with the Miladin Popović Printing House, both based in Pristina. This cooperation continued until 1956, then, these two institutions operated only under the name of Miladin Popović for two years (that is, until 1958), when it joined Rilindja and when Rilindja became the biggest publishing house in Kosovo.23

The year 1958 can be considered as an important year in the history of publishing in Kosovo, because the Rilindja Publishing House not only set high professional standards in the field of publishing – in terms of both the selection of authors, publications preparation staff, printing, binding, high technical accuracy and the quality of publications – but also in the organization (i.e., management) of distribution of books throughout the country, among all the libraries of all levels. So, for a short period of the history of publications in Albanian in Kosovo, the institutional care for written knowledge reached the highest stage of development. Rilindja became the largest publishing organization that Kosovo had ever had, which also had its own printing house bearing the same name and in which almost over 80% of Kosovo’s publications were produced. Rilindja, which, in addition to publishing books under its own name, also published the largest daily newspaper in the country, bearing the same name, also published the most popular cultural magazines in the country, such as Jeta e Re [en. New Life], Përparimi [en. Progress], the well-known social magazine named Kosovarja [en. Kosovan Woman], as well as the Pioneri [en. Pioneer] children magazine.

The colossal work that was done in Rilindja could not have been a coincidence for sure, because Rilindja was made of the intellectual elite of the time, and the most famous writers of Kosovo took care of its publications, either as an editorial board, or as editors, translators, etc., such as Rrahman Dedaj, Azem Shkreli, Rexhep Qosja, Muhamedin Kullashi, Rexhai Surroi, Ali Rexha, Anton Pashku, Nazmi Rrahmani, Sabri Hamiti, Rifat Kukaj, Fahredin Gunga, Ali Podrimja and many others.

The aforementioned and many other intellectuals of Kosovo had already understood that knowledge is not an entity – but a constantly negotiated understanding of the world that is collectively negotiated and considerate of ideological positions,24 which is why they worked hard to change the cultural position that had been imposed on them through the ideology of oppression, and they translated knowledge into an ideology of freedom of creation and knowledge of the world. This intellectual and institutional freedom was shaped only owing to the book and the cultural development that followed as a result of written knowledge and dissemination thereof.

The University of Pristina (1970), the first university in Kosovo, was founded in that surge of cultural development. The opening of the university can certainly be considered the greatest educational and cultural achievement in the country. Students from all over Kosovo already had their own home, in their own country. The establishment of the university also changed the structure of publications, thus increasing the number of university-related publications and research, as well as cultural and literary publications produced by the University of Pristina departments year after year. In 1975, the Kosovo Academy of Sciences and Arts was founded, which also published its publications under the institutional signature. Also, besides the major publishing houses, such as Pristina-based Institute of Textbooks and Rilindja, there were also other, conditionally speaking, smaller publishers, who were specializing in specific publications and were scattered throughout Kosovo. For instance, many literary clubs which also operated as publishers were founded, like Trepça in Mitrovicë/a, Gjon Nikollë Kazazi in Gjakovë, and De Rada in Ferizaj. Likewise, the Hivzi Sylejmani Cultural Centre in Ferizaj and the Çajupi Literary Club in Gjilan also functioned as publishers, mainly publishing young local writers, and promoting their literary efforts.

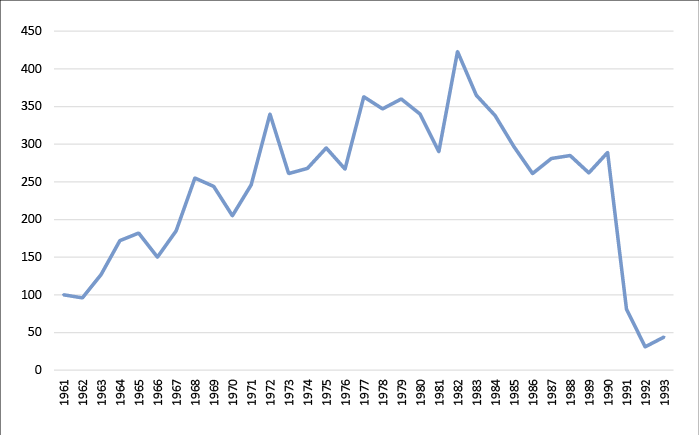

Then there were publishing institutions like Miniera e Trepçës [en. Trepca Mine] with its informational and scientific publications on the Trepca Mine; Kosovo Health Services, which exclusively published health advisory and/or informational texts; and the Drita [en. Light] Publishing House in Ferizaj, which still exists nowadays, and which published texts of a religious nature, etc. Hence, the scene of publications in the Albanian language in Kosovo became richer and more diverse. Based on various catalogues and bibliographies, we have the following statistics of publications in the Albanian language in Kosovo for the period of 1961–1993.

Diagram of publications in Kosovo: 1961–199325

This counting does not include publications in the Albanian language in Macedonia, or even in Croatia and Slovenia, though publications in Albanian in the two latter countries are symbolic publications, given that publications in Albanian in these countries – especially those in Macedonia – were dedicated to the Albanian citizens of those countries, and they did not have a conclusive role in the development of the cultural, political and educational environment in Kosovo. However, publications in Albanian that were produced in Belgrade are included, most of which are, number wise, textbooks that were produced according to the Yugoslav system curricula,26 a system from which Kosovo gained some independence after the amendment of the Yugoslav Constitution in 1974.27 That constitution guaranteed Kosovo equal rights with all other federal units of Yugoslavia, an independence that lasted just over a decade, because political changes in, and the dissolution of Yugoslavia added to political attacks on Kosovo. Those attacks targeted Albanian intellectuals above all, because the Rilindja newspaper was closed in June 1990, and, with it, the Rilindja Publishing House was shut down as well. The Academy of Sciences was also closed, and Albanian students and pupils were expelled from their schools. Most cultural institutions in Kosovo were also closed. Even those that were not officially closed were practically non-functional, because more than 80,000 Albanians were fired from their jobs in the wave of the Serbian repression against Kosovo.28

Therefore, even in the statistics provided above, there is a change in the number of publications from 1990 to 1993, because the cultural, educational and institutional closure in Kosovo also included the culture of publications. Politically, this period for Kosovo almost amounted to a backtrack to the pre-World War II situation, but cultural and educational awareness had taken root among Kosovo Albanians and, therefore, institutional closure did not entail a total closure. As a result, private publishing houses were opened: In this same year, the Buzuku Publishing House (1990) republished – for the first time after sixty years in Kosovo – the epic work Lahuta e Malcis [en. Highland Lute], authored by Gjergj Fishta, who was ostracised following the advent of the Communist system to power in Albania; then, we have the publishing houses: Zëri [en. Voice, 1991), Iliricum (1991), Dielli [en. The Sun, 1991), Fjala [en. Word, 1991), Dukagjini29 (1992) and others.

The cultural needs were met to some extent by the publications of these publishing houses, which were stored and distributed non-institutionally, given that the legal deposit of publications in Albanian could not be stored at the National Library of Kosovo due to the expulsion of Albanians from institutions. The greatest shortage was that of textbooks, because the so-called parallel education system that Kosovo had set up to protect the development of Albanian education after the expulsion of Albanians from schools lacked, besides, there were major issues with school facilities, and also reprinting of textbooks.

Publishing in Yugoslavia’s Successor States, i.e., a chapter thereof on publications in Serbia, reads that Kosovo received textbooks from Albania at the time of the parallel system.30 As a matter of fact, in 1996, a collaboration had been initiated between educational institutions of Kosovo and Albania to design school curricula,31 which only remained an agreement on paper, because, one year later, in 1997, Kosovo became a war zone. Therefore, from 1993 to 1999, Kosovo, namely Kosovo schools, conducted classes by using the already existing texts published by the Institute of Textbooks and Teaching Aids of Kosovo.

All those who attended classes in Albanian schools in Kosovo from 1993 to 1999, including the author of this text, know that classes were held either by using old books that had been published earlier – of which students took special care, wrapping their covers in protective paper, and knowing that the same books would have to serve other generations in the following years – or else they would have to do without any books at all. To create a clearer idea of the situation, you may imagine a large room that served as a classroom to the students, who would keep pencils and notebooks on their hands, and to a teacher or a professor, who would dictate a text which the students would write down in their notebooks in order to learn it at home later on. Albanian schools and publishing houses in Kosovo had to cope with such a situation until 1999. Though there was a decrease in the number of publications from 1990 to 1999, the tradition of publishing had already gained ground. The only thing that we lack now is a clear picture of publications in those years: the data are approximate, based on titles that the National Library of Kosovo has managed to collect, but the awareness that books could not escape the fires of the war either and the lack of full knowledge of publications of the period remain the biggest concerns when it comes to the history of the book in Kosovo.

Conclusion

This research on Albanian book publishing in Kosovo is preceded by a historical overview of Albanian society, which clarifies the discussion surrounding the subject matter of this article. Although Albanian book publishing in Kosovo began in 1943, which may seem late compared to neighbouring countries, the establishment of the right to publish in Albanian and the opening of Albanian schools significantly transformed a society that once faced over 50% illiteracy into a more educated and civilized community. The inception of Albanian book publishing in 1943 marked a natural progression, evolving from a single article in Albanian to the establishment of publishing institutions in 1944 and to a rise in the number of publications. From 1943 to 1963, 1230 books were published, whereas, from 1964 to 1974, 2478 books were published, and from 1975 to 1985, the number increased significantly to 3689, from 1986 to 1990, 1378 books were published, while in 1991–1993, when the political system in the country had changed, the number of publications was reduced by 80% without counting the reprints which were numerous, especially those of text books. Initially reliant on translations from Serbo-Croatian, the culture of translation persisted until the emergence of local experts proficient in various foreign languages, who translated essential educational texts and a substantial portion of world literature. The growth of publishing institutions in Kosovo not only enhanced the quantity and quality of publications but also fostered the development of the local talent, leading to the creation and publication of works by local authors at Rilindja, the most renowned publishing house in Kosovo’s cultural history. Even today, Rilindja’s publications are held in high regard within Albanian society, reflecting their enduring value and quality. Over the past fifty years, Kosovo has witnessed a fascinating evolution in its publishing culture, characterized by a period of stabilization and rapid growth in the 1970s and 1980s, followed by a sharp decline in the 1990s due to the political turmoil. Nevertheless, the culture of publishing has persisted, and half a century of its existence has positively transformed Albanian society in Kosovo, connecting it with the civilized Western world and facilitating its transition from a culture that primarily consumed external influences to one that actively produces its own cultural output.

Literature

1. 30 [tridhjetë] vjet të veprimtarisë botuese në Kosovë. Prishtinë: Biblioteka Popullore dhe Universitare e Kosovës, 1975.

2. AHMETI, Sevdie. Bibliografia e Librit Shqip në Jugosllavi: (botimet e vitit 1967). Prishtinë: Biblioteka Popullore dhe Universitare e Kosovës, 1973

3. AHMETI, Sevdie. Bibliografia e Librit Shqip në Jugosllavi: (botimet e vitit 1968). Prishtinë: Biblioteka Popullore dhe Universitare e Kosovës: Shërbimi Bibliografik, 1973

4. AHMETI, Sevdie. Bibliografia e Librit Shqip në Jugosllavi: (botimet e vitit 1966). Prishtinë: Biblioteka Popullore dhe Universitare e Kosovës, 1972.

5. BERISHA, Ibrahim; BASHOTA, Sali. Albanian Book and Libraries in Kosovo. Journal of Balkan Libraries Union, 2015, Vol. 3(2), p. 54–60.

6. BIGGINS, Michael, CRAYNE, Janet (eds.). Publishing in Yugoslavia’s Successor States. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2000.

7. BOGDANI, Pjetër: Cvnevs Prophetarvm de Christo Salvatore mvndi, et eivs evangelica verita, italice et epiroticè contexta, et in duas Partes divisa a Petro Bogdano Macedone Sacr. Congr. de Prop. Fide Alvmno Philosophiæ, & Sacre Theologiæ Doctore, olim Episcopo Scodrensi, & Administratore Antibarensi; nunc verò Archipiscopo Scvporvm, ac totivs Regni Serviæ administratore, Pars prima Patavii: Ex Typographia Seminarii. Opera Avgvstini Candiani, M.DC.LXXXV [1685].

8. DEADAJ, Rrahman (ed). Dyzet vjet veprimtari botuese: 1943–1983: katalog. Prishtinë: Rilindja, Redaksia e botimeve, 1983.

9. GËRGURI, Mehmet, AHMETI, Sevdije, GËRGURI, Musa. Një pasqyrë e veprimtarisë botuese në Kosovë, Prishtinë: Biblioteka Popullore dhe Universitare e Kosovës, 1973.

10. HALIMI, Destan. Bibliografi e publikimeve Mësimore Universitare të botuara në periudhën 1970–1985. Prishtinë: Universiteti i Kosovës në Prishtinë, 1985.

11. HYSA, Mahmud. Hyrje në Letërsinë Shqiptare. Prishtinë: Enti i Teksteve dhe i Mjeteve Mësimore i Kosovës, 2000.

12. KOLIQI, Hajrullah. Historia e Arsimit dhe Mendimit Pedagogjik Shqiptar. Prishtinë: Libri Shkollor, 2012.

13. KOLIQI, Hajrullah., Sistemi i Arsimit në Kosovë, Pristina: Libri Shkollor, 2004, 49 p.

14. KRAJA, Mehmet (ed). Fjalori Enciklopedik i Kosovës I: A-K. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe e Arteve e Kosovës, 2018.

15. KRASNIQI, Nysret. Letërsia e Kosovës: 1953-2000. Pristina: 99 AIKD, 2016.

16. MALCOLM, Noel. Kosovo: A Short History. Pristina: Koha, 2001

17. RAMAJ, Abdyl. Bibliografia e librit shkollor në Kosovë: 1945-1985. Prishtinë: ETMMK, 1985.

18. REXHA, Ali. Bibliografi publikimesh në gjuhën shqipe në Kosovë e Metohi: 1944–1958. Year 5, n. 7–12 (July–December, 1959) – Year 6, n. 1-8, (January-August 1960) – Year 7, n. 1–3 (January–March 1961). Prishtinë: NBGB Rilindja, 1959–1976

19. SCHMITT, Oliver Jens. Kosovo: A Short History of one Central Balkan State. Pristina: Koha, 2012

20. VALLEJO, Irene. Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World. New York: Penguin Random House (Vintage Books), 2025. ISBN 978-0 593-31890-4

21. VELIU, Veli. Bibliografia e Librit Shqip në Jugosllavi: (botimet e vitit 1969). Prishtinë: Biblioteka Popullore dhe Universitare e Kosovës, 1973.

22. WAGONER Brady, JENSEN, Eric, OLDMEADOW, Julian A. (eds). Culture and Social Change: Transforming Society through the Power of Ideas Charlotte (N. C.): Information Age Publishing, 2012.

1 Vallejo, Irene: Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World. New York: Penguin Random House (Vintage Books), 2025, 85 p.

2 Bibliography of Publications in Albanian Language in Kosovo and Metohija: 1944–1958], authored by Ali Rexha and published in several issues of the Përparimi cultural magazine in 1959–1960; from Bibliografi e publikimeve Mësimore Universitare të botuara në periudhën 1970–1985 [en. Bibliography of University Teaching Publications Published from 1970 to 1985] by the University of Kosovo in Pristina, 1985; from Bibliografia e Librit Shkollor në Kosovë: 1945–1985 [en. Bibliography of School Books in Kosovo: 1945–1985], published by the Institute of Textbooks and Teaching Aids of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, Pristina, 1985; and from the Bibliography of Albanian Books: 1944–1999 – Manuscript bibliography compiled by the Bibliography Department of the National Library of Kosovo.

3 Një pasqyrë e veprimtarisë botuese në Kosovë [en. An Overview of Publishing Activity in Kosovo], published by People’s and University Library of Kosovo in 1973; from 30 vjet të veprimtarisë botuese në Kosovë [en. 30 Years of Publishing Activity in Kosovo], published by People’s and University Library of Kosovo in 1975; from Dyzet vjet veprimtarie botuese: 1943–1983 [en. Forty Years of Publishing Activity: 1943–1983], a catalogue of Rilindja publications published in 1983; from Katalog i botimeve: 1984 [en. Catalogue of Publications: 1984], published by Rilindja in 1984

4 Berisha, Ibrahim; Bashota, Sali. Albanian Book and Libraries in Kosovo. Journal of Balkan Libraries Union, 2015, Vol. 3(2), p. 54–60.

5 Trix, Frances. Publishing in Kosova/Kosovo. In Biggins, Michael; Grayne, Janet (eds.). Publishing in Yugoslavia’s Successor States. New York: Routledge and Taylor & Francis Group, 2000, p. 159–183.

6 Schmitt, Oliver Jens. Kosovo: A Short History of one Central Balkan State. Pristina: Koha, 2012, 21 p.

7 Malcolm, Noel. Kosovo: A Short History. Pristina: Koha, 2001, p. 3–5.

8 Schmitt, Oliver Jens, Kosovo: A Short History of one Central Balkan State. Pristina: Koha, 2012, 101 p.

9 Krasniqi, Nysret. Letërsia e Kosovës: 1953–2000 [en. Literature of Kosovo: 1953–2000]. Pristina: 99 AIKD, 2016, 10 p.

10 Kraja, Mehmet (ed). Fjalori Enciklopedik i Kosovës I: A–K [en. Kosovo Thesaurus] (Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe e Arteve e Kosovës, 2018), 844–845 p.

11 Bogdani, Pjetër. Cvnevs Prophetarvm de Christo Salvatore mvndi, et eivs evangelica verita, italice et epiroticè contexta, et in duas Partes divisa a Petro Bogdano Macedone Sacr. Congr. de Prop. Fide Alvmno Philosophiæ, & Sacre Theologiæ Doctore, olim Episcopo Scodrensi, & Administratore Antibarensi; nunc verò Archipiscopo Scvporvm, ac totivs Regni Serviæ administratore, Pars prima [en. The Bend of Prophets... compiled in Italian and Albanian [epirotice] and divided into two parts by Pjetër Bogdani... doctor of philosophy and theology, former bishop of Shkodër and former administrator of Tivar, today archbishop of Skopje and administrator of the whole Kingdom of Serbia]. [Padua]: Patavii: Ex Typographia Seminarii. Opera Avgvstini Candiani, M.DC.LXXXV [1685]. The original edition of this work is stored at the National Library of Kosovo.

12 Trix, Frances. Publishing in Kosova/Kosovo. In Biggins, Michael; Grayne, Janet (eds.). Publishing in Yugoslavia’s Successor States. New York: Routledge and Taylor & Francis Group, 2000, p. 160.

13 Prishtina, Hasan: Nji shkurtim kujtimesh mbi kryengritjen shqyptare të vjetit 1912 [en. Brief Memoir on the Albanian Uprising of 1912] (Shkodër: [s.n], 1921 (the book is stored at the National Library of Kosovo).

14 Schmitt, Oliver Jens, Kosovo: A Short History of one Central Balkan State. Pristina: Koha, 2012, 100 p.

15 Rexha, Ali. Bibliografi publikimesh në gjuhën shqipe në Kosovë e Metohi: 1944–1958 [en. Bibliography of Publications in Albanian in Kosovo and Metohija]. Përparimi: Cultural magazine, year 5. no. 9 (1959), p. 563–566.

16 Dyzet vjet veprimtarie botuese: 1943–1983: katalog [en. Forty Years of Publishing Activity: Catalogue] (Prishtinë: Rilindja, Publication Editorial Office, 1983), 5 p.

17 Newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, published in 1929–1944 (the information is based on a bibliographic description of the National Library of Serbia).

18 Dyzet vjet veprimtarie botuese: 1943–1983 [en. Forty Years of Publishing Activity: 1943–1983], Pristina: Rilindja, Publication Editorial Office, 1983), 5 p.

19 Ibid., p. 6.

20 All the data are a result of bibliographic descriptions of units included in Bibliografi Publikimesh në Gjuhën Shqipe në Kosovë e Metohi 1944–1958 [en. Bibliography of Publications in Albanian in Kosovo and Metohija 1944–1958], published in several issues of the Përparimi magazine, Year 5, Issues 7–12 (July-December 1959) – Year 6, Issues 1–8, (January-August 1960) – Year 7, Issues 1–3 (January-March 1961). Pristina: Cultural Magazine: Pristina: NBGB Rilindja, 1959–1976; 22 cm; also, from the foreword of the book Dyzet vjet veprimtarie botuese: 1943–1983 [en. Forty Years of Publishing Activity: 1943–1983], catalogue of publications of Rilindja Publishing House, also published by Rilindja in 1983.

21 Këndimi im i parë (en. My First Singing), ([Prizren]: [Educational Directorate for Kosmet], [1945]) (The book is stored at the National Library of Kosovo)

22 Krasniqi, Nysret. Letërsia e Kosovës 1953–2000 [en. Kosovo Literature]. Prishtinë: 99-AIKD, 2016, p. 27.

23 Information about the history of the Mustafa Bakija, Miladin Popović and Rilindja publishing houses was taken from the book titled Dyzet vjet veprimtarie botuese: 1943–1983 [en. Forty Years of Publishing Activity: 1943–1983], whereas information about other publishing houses was extracted from the research entitled Bibliografi publikimesh në gjuhën shqipe në Kosovë: 1944–1958 [en. Bibliography of Publications in the Albanian Language in Kosovo: 1944–1958], authored by Ali Rexha, and published in the Përparimi magazine; from the Bibliografia e Librit Shqip në Jugosllavi: 1966–1969 [en. Bibliography of the Albanian Book in Yugoslavia: 1966–1969], published in separate editions with the respective years, and from the manuscript bibliography owned by the National Library of Kosovo, prepared by the Department of Bibliography of the National Library of Kosovo and titled Libri Shqip: 1944–1999 [en. Albanian Book: 1944–1999].

24 Wagoner, Brady; Jensen, Eric; Oldmeadow, Julian A. (eds.). Culture and Social Change: Transforming Society Through the Power of Ideas. Charlotte, (N. C.): Information Age Publishing, 2012), X p.

25 The data may not be fully accurate, due to the lack of records of publications in Kosovo. These figures have been extracted from: Bibliografi publikimesh në gjuhën shqipe në Kosovë e Metohi: 1944–1958 [en. Bibliography of Publications in the Albanian Language in Kosovo and Metohija: 1944–1958], authored by Ali Rexha and published in several issues of the Përparimi cultural magazine in 1959–1960; from Një pasqyrë e veprimtarisë botuese në Kosovë [en. An Overview of the Publishing Activity in Kosovo], published by the People’s and University Library of Kosovo in 1973; from 30 vjet të veprimtarisë botuese në Kosovë [en. 30 Years of the Publishing Activity in Kosovo], published by the People’s and University Library of Kosovo in 1975; from Dyzet vjet veprimtarie botuese: 1943–1983 [en. Forty Years of Publishing Activity: 1943–1983], a catalogue of Rilindja publications published in 1983; from Katalog i botimeve: 1984 [en. Catalogue of Publications: 1984], published by Rilindja in 1984; from Bibliografi e publikimeve Mësimore Universitare të botuara në periudhën 1970–1985 [en. Bibliography of University Teaching Publications published from 1970 to1985] by the University of Kosovo in Pristina, 1985; from Bibliografia e Librit Shkollor në Kosovë: 1945–1985 [en. Bibliography of School Books in Kosovo: 1945–1985], published by the Institute of Textbooks and Teaching Aids of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, Pristina, 1985; and from the Bibliography of Albanian Books: 1944–1999 – Manuscript bibliography compiled by the Bibliography Department of the National Library of Kosovo.

26 Koliqi, Hajrullah, Historia e Arsimit dhe mendimit Pedagogjik Shqiptar [en. History of Education and Albanian Pedagogical Thought] (Pristina: Libri Shkollor, 2012), 486 p.

27 Malcolm, Noel. Kosovo: A Short History. Pristina: Koha, 2001), 340–341 p.

28 Ibid., 361 p.

29 In Publishing in Yugoslavia’s Successor States, the year 1989 appears as the date of establishment of this publishing house (see p. 164). According to the book registry at the National Library of Kosovo, Dukagjini published the earliest book in 1992, while, in the background presented on the website of the publishing house, the date of establishment is given as 1994.

30 Trix, Frances. Publishing in Kosova/Kosovo. In Biggins, Michael; Grayne, Janet (eds.). Publishing in Yugoslavia’s Successor States. New York: Routledge and Taylor & Francis Group, 2000, p. 96.

31 Koliqi, Hajrullah. Sistemi i Arsimit në Kosovë [en. Education System in Kosovo], Pristina: Libri Shkollor, 2004, 49 p.