Kriminologijos studijos ISSN 2351-6097 eISSN 2538-8754

2018, vol. 6, pp. 58–77 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/CrimLithuan.2018.6.3

Electronic Monitoring in Europe – a Panacea for Reforming Criminal Sanctions Systems? A Critical Review

Frieder Dünkel

Prof. em. dr., Universität Greifswald, Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftliche Fakultät,

Lehrstuhl für Kriminologie

duenkel@uni-greifswald.de

Abstract. First experiments with electronic monitoring emerged in Europe in the early 1990s. Within 15 years, the majority of countries in Europe reported having introduced electronic monitoring at least as pilot projects. The amazing dynamic rise of electronic monitoring in Europe may be explained by the commercial interests that become evident when looking at the activities of private companies selling the technique. Although electronic monitoring seems to have expanded in many countries, one has to realize its marginal role within the European sanctions systems compared to other sentencing or release options. On average, only about 3% of all probationary supervised persons were under electronic monitoring at the end of 2013. This article deals with questions regarding the impact of electronic monitoring on prison population rates and reduced reoffending, with net-widening effects and costs, essential rehabilitative support, human rights-based perspectives and the general (non)sense of electronic monitoring.

Keywords: electronic monitoring, punishment, international standards, human rights, criminal justice.

Received: 9/7/2018. Accepted: 10/8/2018

Copyright © 2018 Frieder Dünkel. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

The question of how to rehabilitate, control and supervise offenders effectively in a community has been of major importance since the late 19th century, when the search for alternatives to imprisonment caught the interest of crime policymakers and the reformers of the criminal sanctions system. The German Franz von Liszt influenced the debate by particularly criticizing short-term imprisonment. In consequence, during the first half of the 20th century, fines and probation or suspended prison sentences were found as an answer to cope with increasing prison populations. The demand for more effective control of offenders in the community was the side effect (Germ. Begleitmusik) of a punitive turn in the 1980s and 1990s, characterized by Garland (2001) as the “culture of control.” The latest development in this direction was possible by new surveillance techniques, first in the form of radio frequency-based devices, and more recently by using the GPS surveillance technique (see Haverkamp 2014). This area, being one of the most dynamic fields of criminal justice, deserves a critical review not only under the headline of modern penalty but also with regards to criminological evidence on what works and how; tradition penal values, such as proportionality and human dignity, must be assessed in view of this as well. The present paper is based on some of the results of an EU-funded project on the “Creativity and Effectiveness in the Use of Electronic Monitoring as an Alternative to Imprisonment in EU Member States” (Grant No. JUST/2013/JPEN/AG/4510) covering Belgium, England/Wales, Germany, the Netherlands and Scotland (see Hucklesby et al. 2016) as well as on a larger European comparative project covering 12 additional countries looking not only at the crime policy developments but the human rights-based perspectives concerning electronic monitoring as well (see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017).

2. The rise of electronic monitoring in European sanctions systems

First experiments with electronic monitoring (EM) in Europe emerged in the early 1990s in England and Wales, followed by small-scaled projects in Sweden and the Netherlands (see Nellis 2014). Within 15 years, a majority of countries in Europe (27) reported having introduced EM at least as pilot projects, whereas Nellis (2014, p. 490) found only 12 countries that had made no efforts yet to introduce it (Italy, Greece and Lithuania amongst them), which, in the meantime, have also had some small projects or experiences in the field (see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017). The Council of Europe’s SPACE II-statistics – although not always complete or accurate because of the reporting errors by some member states – indicate that EM does not exist in only 12 out of 47 jurisdictions (see Aebi, Chopin 2016, p. 18 f.). However, again, Greece and Italy are mentioned as countries where EM is not existing as a disposal, which is wrong.

Looking at numbers of EM-cases on a given day or per year seems much more difficult, as the SPACE-statistics report only about 21 out of 35 “user”-countries. Again, we can observe how the shortcomings of statistical data become evident, if, for example, 271 cases dated to December 31, 2014 are included in the list of counted instances, whereas our national report in the abovementioned EU-project revealed a little less than 14 000 cases (probably due to non-reported cases of stand-alone EM-measures outside the probation service). Renzema and Mayo-Wilson (2005, p. 215) reported an estimated number of 100 000 persons electronically supervised in the US for 2003 and a daily population of about 9 000 in Europe, of the 77% in the UK. Since then, a further considerable rise of EM has taken place.

This amazing dynamic rise of EM in Europe may be explained by the commercial interests that become evident when looking at the activities of private companies selling the technology required for conducting EM. Insofar a new quality has emerged in the penal law (similar to the rise of the prison industry by privatizing imprisonment in the US) that endangers the role of the state. Traditionally, the state/government formulates the aims of punishments and the ways to enforce them. In some areas, private entrepreneurs have come into “the game,” for example, in juvenile welfare and justice. At least in the continental European jurisdictions, these “players” are non-profit organizations (often financed mainly by the communities). This changes with the involvement of the profit-oriented private sector, as the advertisement of new sanctions and measures is now proactively made by private companies, which also impose pressure on governments. Lithuania is a recent example of that (see Sakalauskas in Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017): the government rented a certain number of devices and had to pay a considerable amount of funds regardless of how much use was made of these devices by the judges. Thus, in the first years of use, a case under EM was more expensive than a place in prison. The government had to advertise a greater use of EM in order to lower the costs-per-case of EM.

A similar reluctance of the judiciary and a low acceptance of EM can be seen in Greece, where again the government has attempted to influence the judges to use EM more extensively (Pitsela in Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017).

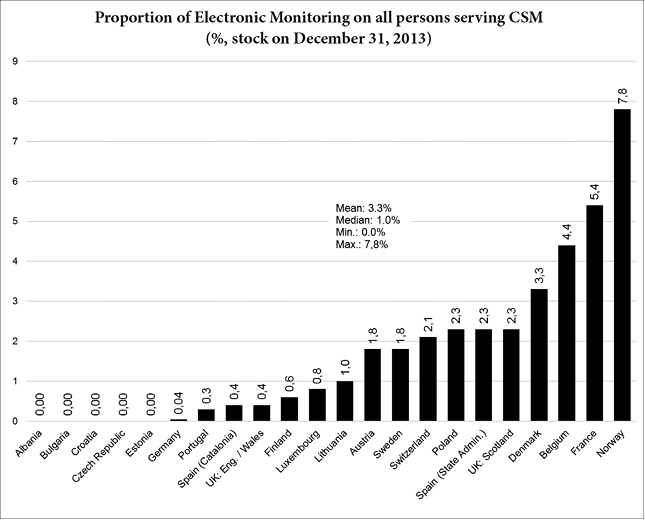

Although EM seems to expand in many countries, one has to realize its marginal role within the European sanctions systems compared to other sentencing or release options. On average, only about 3% of all probationary supervised persons were – according to the SPACE-statistics – under EM at the end of 2013 (see Figure 1). Even when considering high underreporting rates in some countries, it becomes clear that the amount of public and governmental interest in EM contrasts very strongly to its actual importance in practice. Again, this may only be explained by the pressure and publicity exercised by private companies selling the technology and services of EM.

Reference: Aebi, M. F. & Chopin, J. (2014). SPACE II – Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics: Space II survey 2013. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Table 1,1, p. 17–18.

FIGURE 1. The proportion of electronic monitoring on all persons serving community sanctions and measures (%, stock on December 31, 2013)

3. Aims and target groups of electronic monitoring – diverse approaches in the european context

The somewhat “victory” of EM in the “penal field” (Page 2013) has much to do with the emergence of surveillance technologies in general (Nellis 2017) and the privatization of penal social control in particular. The causes for introducing or expanding EM in most countries were the high pressure of prison overcrowding during the 1980s and 1990s. Therefore, in many countries, the dominating aim was to cope with increasing prison population rates. But the rehabilitation goal was of major importance as well, in particular in Scandinavia, Austria, the Netherlands and other countries that emphasize the importance of the probation service and use electronic monitoring as an additional form of controlling rehabilitative directives or supporting parole schemes in collaboration with correctional and probation services.

In contrast, England and Wales – and more recently Belgium – have introduced EM as a stand-alone measure without any involvement of social workers. EM represents only a short-term restriction of liberty punishment without any rehabilitative efforts or programs in these cases.

In some countries, the new technology of GPS-tracking offered the possibility of surveillance in order to protect (possible) victims by establishing “inclusion” and “exclusion zones” for the offenders, which is now used on a very limited scale, e.g., in England/Wales, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain.

A very different approach is to focus on particularly high-risk offenders, even if they have fully served their sentences. These men and women should be free, but society does not accept them being released without supervision. Some countries, such as France, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, have introduced a probation-like penal measure, the so-called supervision of conduct order, which allows supervision and EM in order to protect the society from severe re-offending. In the Netherlands, the respective legal base is a suspended treatment measure called TBS. In Germany, the respective law reform of 2011 was the direct result of the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights, which, in 2009, sentenced Germany for illegal punishment by the security measure of preventive detention (a measure for dangerous offenders to be served after having fully served the determinate prison sentence, for details see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017), and which allows for an EM-supervision of these offenders. In France, the focus is more on terrorist offenders and their social environment, a question which – after the events of December 2016 in Berlin – has also been discussed in Germany and was enshrined in the Police Laws of the federal states in 2018 (a supervision for the so-called “endangering persons,” regularly from an Islamic background).

4. International standards and human rights issues, particularly recommendation 4 (2004) of the council of europe

Human rights standards concerning the criminal justice system had traditionally been developed with regards to imprisonment. Standard minimum rules for prisoners had first been issued by the UN (1955), and the so-called Mandela Rules (2015) were just recently adopted as a modern and actualized version of these standards. The Council of Europe, in 1973 and 1978, followed with its European Prison Rules, which have been updated in 2006 (see, for a comprehensive view of European Prison Law, van Zyl Smit, Snacken 2009). In the late 1980s, some evidence came up that human rights violations were not limited to sanctions depriving persons of their liberty but that the so-called community sanctions were also bearing the risk of human rights violations. Humiliating and stigmatizing forms of community service were just one example. It is evident that intrusive measures, such as electronic monitoring, have a special potential for human rights infringements. In 1992, the Council of Europe adopted Recommendation (92) 2 on Community Sanctions and Measures, a general outline on how to use and organize this area of sentencing (the correspondent UN-based rules were the so-called Tokyo-Rules from 1990). Recently, more specific Recommendations – on early/conditional release (Rec. [2003] 23), on probation, the Probation Rules (Rec [2010] 1), and, finally, on electronic monitoring (Rec. 2014) 4 – have been issued.

The following remarks concentrate on these Recommendations on electronic monitoring, however not without citing two important regulations contained in the 2010 Probation Rules: it is stated in No. 57 that “when electronic monitoring is used as part of supervision, it shall be combined with interventions designed to bring about rehabilitation and to support desistance.” EM is, therefore, brought in line with the Council of Europe’s orientation toward the rehabilitation and social reintegration of offenders. Furthermore, No. 58 of the Probation Rules refers specifically to the principle of proportionality by stating that “the level of technological surveillance shall not be greater than is required in an individual case, taking into consideration the seriousness of the offence committed and the risks posed to community safety” (Council of Europe 2010).

The aim of rehabilitation is taken up in the EM-Rules of 2014, e.g., in Rule 8: when considering the possibility of EM as a stand-alone measure, Rule No. 8 says: “Electronic monitoring may be used as a stand-alone measure in order to ensure supervision and reduce crime over the specific period of its execution. In order to seek longer term desistance from crime it should be combined with other professional interventions and supportive measures aimed at the social reintegration of offenders.” In the commentary, the empirical evidence on what we know about EM and its possible effects and desistance from crime is outlined (see Part 7 below).

The EM-Recommendation (2014) 4 emphasizes that the “use, as well as the types, duration and modalities of execution of electronic monitoring in the framework of the criminal justice shall be regulated by law” (Basic Principle No. 1). This is not self-evident, as our study has also revealed that the conditions and target groups are not clearly described by law in many countries. This is important, as in its several rules, the Recommendation “warns” the users that EM is an intrusive measure that can violate basic human rights and therefore is to be applied cautiously and with respect to possible human rights infringements (including data protection rights, which particularly in Germany are of major importance, see Dünkel et al. in Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017, p. 11 ff.). The EM-Recommendation, therefore, is a further good document stating that crime policy should be moderate in imposing intrusive sanctions or measures. The Rules specifically address the problem that EM may contribute to an unnecessary and therefore disproportionate net-widening if it is used a measure for avoiding pre-trial detention (see Rules No. 2 and 16). If there is no real risk of escape, pre-trail detention would not be legitimate; therefore, EM is also not justifiable. If there is a strong risk of escape, EM would not be appropriate in hindering a person from disappearing. Practical experience in many countries demonstrates that these restrictions against imposing pre-trail detention (and EM) are not strictly observed. Therefore, one could assume that an “illegitimate” use of EM is widespread if it is used in this field. Countries who follow these considerations logically do not find any suitable cases for the application of EM (see, e.g., Germany in the Hesseproject, or Switzerland). In Switzerland – as far as can be seen – since 2011, only two cases of replacing pre-trial detention with EM have been registered (see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017).

The issue of proportionality is further addressed in the Basic principles 4. and 5., when stating that EM “shall be proportionate in terms of duration and intrusiveness to the seriousness of the offence alleged or committed” (No. 4) or that EM “shall not be executed in a manner restricting the rights and freedoms of a suspect or an offender to a greater extent than provided for by the decision imposing it” (No. 5). The “rights of families and third parties in the place to which the suspect or offender is confined” must be considered (No. 6).

5. Expanding social control – net-widening or reducing prison population rates?

One of the crucial questions for empirical research is to what extent the aim of reducing prison population rates has been reached, and to what extent EM is only another alternative in the list of alternatives. In that case, it can be an additional element in the scope of community sanctions, intensifying social control beyond the “normal” probation work. Such intensification may be justified if the traditional probation work and supervision was insufficient and if evidence shows that an additional need for supervision and control of this (more technical) kind would be helpful. Advertisers of EM promote the idea that EM helps unstructured and instable offenders to adapt to a more structured daily routine, which indeed may be true in individual cases. But what happens after the (mostly short) period of EM, if the devices are removed?

In our study on 17 European countries (see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017), we could only rarely and, in such a case, to a very limited extent find “indicators” for the reductionist potential of EM concerning prison population rates. A good example are the Netherlands. The “dramatic” decline of the prison population rate (from 128 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2006 to about 85 in 2012 and 53 in 2015, see Dünkel 2017) took place before EM got quantitatively important. The increase of numbers of monitored offenders and the average time of about 4 months under EM may have somehow contributed to the further reduction of the prison population since 2012, but the major part apparently has to do with the decline of registered (serious) offending and the strong emphasis given to other sentencing options than EM-programs – the suspension of (conditional) sentences (without EM) in particular.

On any given day, Germany has no more than about 70 serious offenders under GPS monitoring (as an additional control element to the probation service after having fully served a long-term prison sentence or being released from preventive detention or a psychiatric security measure, see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017a) and another 80 offenders under “regular” EM in one of the 16 Federal states (Hesse), a state which happens to be the only one to practice EM in this form. The question of reducing prison population rates by introducing EM has never been an issue in Germany but with regards to specific sentencing strategies in the area of traditional community sanctions. As in the Netherlands, the decline in registered (serious) crime rates is the main reason for the decline in the German prison population since the mid-2000s (see Dünkel 2017).

In our comparative study on 17 jurisdictions in Europe (see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017), we found indicators for influences on the size of prison population rates only in countries that explicitly provide legal safeguards to really replace terms of imprisonment by EM-supervision, in particular if the probation services are involved preventing excessive net-widening structures. This safeguard does not work in England and Wales, where the probation services are widely excluded, and where the private companies providing the technology are also responsible for executing the sanctions.

Good examples for avoiding net-widening are Austria, Finland, Sweden, and to some extent, the Netherlands (see above).

In Austria, EM is provided for prisoners during their last stage of imprisonment, who can serve their sentence in house arrest. In Finland, EM, as a judicial sanction, is only provided if fines and community service seem to be inappropriate; in other words, EM is the very last resort before imprisonment. Also, in the case of early release from prison, the Finnish legislator follows a real reductionist approach by giving prisoners the opportunity to serve up to six months before receiving a “regular” early release (a kind of quasi-automatic parole). Therefore, prison capacities are saved in these cases. However, Finland also has some doubtful practices that can be judged as a net-widening strategy. Since the past few years, prisoners in open prison facilities wear electronic devices (when they go out for work or leisure time activities) in order to unburden staff members from controlling their activities. This is a clear additional (and, in most cases, probably unnecessary) social control measure.

Also, in Sweden, the legislator has emphasized that EM should only replace unconditional prison sentences and no other alternatives. Insofar one could think of EM as contributing to the recent decline of the prison population. However, only short-term imprisonment of up to 6 months is considered, and, in practice, the periods of EM are regularly very short: 50% of EM sanctions during 2013–2015 have replaced a prison sentence of up to one months, another 30% – of up to 3 months, and only 20% – of 3–6 months (see Yngborn in Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017). The Swedish policy can only be understood in terms of the long tradition of imposing short-term unconditional prison sentences for relatively minor crimes, such as drunk driving. In Germany, the legislator – already in 1969 and by a major law reform – has replaced short-term prison sentences with fines. EM does therefore not play an important role in Germany. In Sweden, changes have taken place in sentencing by expanding fines; therefore, the importance of EM is little.

One other critical question relates to the target groups of EM. The group of “dangerous” offenders are in the scope of electronic monitoring only in Germany, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland. In all other countries, EM is used for middle-range crimes and low-risk offenders. This raises the question of whether the traditional and less intrusive forms of supervision and control by the probation agencies are not sufficient or if other community sanctions and measures are less “credible.” The latter seems to be characterizing the English sentencing policy under the so-called “punitive turn.” Indeed, the call for more “credible” and “tough” alternatives has opened the floor to expand technical solutions and to exclude the traditional probation services. To some extent, English probation services have contributed to this development by categorically refusing to take part in any EM-based sanctions (see Nellis 2017).

The core question of taking the principle of proportionality seriously reveals very different approaches in Europe and often within the crime policy of a single given country.

In Belgium, for example, EM is used in different forms. In the case of longer prison sentences of more than 3 years, EM can be used the prepare release by serving the sentence at home for up to 6 months before following a regular parole release, thus replacing a definite prison term with EM. Probation services are involved in these cases, and EM supports their work. On the other hand, a new policy came into effect just recently that allows a stand-alone EM supervision of offenders sentenced with up to one year of imprisonment without any support from the probation services and without any regulation based on which other community services should or could be prioritized.

In Denmark, the back-door-strategy to serve the last 6 months of a prison sentence is a reductionist measure, whereas EM, as an immediate community sanction, is probably more often used more as an alternative to other community sanctions than to imprisonment.

France uses a lot of different EM options; again, only a back-door-strategy of an earlier release combined with EM has a potentially reductionist effect. Although positive numbers are increasing in this case, the prison system suffers from one of the highest overcrowding rates in Europe.

One could extend the number of examples, but so far one may conclude the following:

• that the introduction and expansion of EM in Europe did not have any major impact on prison population rates and, in most cases, failed to resolve the problems of overcrowding (e.g., England/Wales, France, Italy, Poland and, at least until recently, Belgium);

• that in many cases it just formed an additional or intensified form of social control;

• that it contributed in some countries to eliminating or diminishing the importance of the traditional social support schemes, such as probation services, by establishing EM as a stand-alone sanction (in England/Wales, Belgium or Scotland, with a reverse trend in crime policy in the last case);

• that in other cases, it became part of a rehabilitation-oriented community sanction under the dominant role of the probation or correctional services (Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland or, increasingly, Scotland).

6. Does electronic monitoring save costs for the criminal justice system?

Closely related to the question of whether EM really contributes to a reductionist approach concerning the use of imprisonment is the question of costs. Is EM saving costs as widely advertised by its promoters, in particular the private companies selling the technology?

One, at first glance, convincing argument is that the daily costs of EM are far smaller than a day costs in prison. All reports of our European comparative project on 17 countries demonstrate that the daily costs of EM vary considerably, between some 5€ in Poland and about 100€ in Denmark or Norway, and that they are indeed lower than imprisonment. However, this calculation is only valid if (1) EM is really replacing imprisonment and (2) a cheaper alternative, such as simple early release measures, probation or parole (without EM) are not available or appropriate.

The second consideration – whether any other options of sanctions could be used – is often neglected. One of the fatal consequences in this direction is the implementation of EM as a stand-alone sanction (e.g., in Belgium or England and Wales) for low-risk offenders. It is evident that other sentencing options, such as fines or community work orders, have not been sufficiently taken into consideration. EM then takes the place of a cultural gap in developing “creative” appropriate community sanctions or measures. Therefore, it is somehow tragic that the EU-funded EM-project referred in this paper (see under Part 1 above) ran under the heading of “Creativity […] in the Use of EM” and generally excluded the whole range of criminal sanctions, where more creativity could have come to different solutions than to thinking about how to increase the use of EM.

Having presented these mixed results, the main research question remains open – could EM also contribute to reducing reoffending and promoting social integration?

7. Criminological theory and electronic monitoring – why should electronic monitoring reduce crime?

From a theoretical point of view, one must differentiate and isolate EM as an integrated rehabilitative measure that cannot be easily evaluated, as it is combined with the rehabilitative work of the correctional and probation services. The “plus”-effect of EM is difficult to isolate. However, one could build comparable groups of probationers with and without EM even in a randomized experiment.

EM, as a stand-alone measure, could be evaluated more easily. The problem is that the theoretical assumptions are not really convincing: why should EM reduce crime in the cases where no other social support is provided? The only theoretical aspect is that the offender calculates that they will be detected when reoffending and that they do not want be moved to a prison population. This is the classic question of general prevention (or deterrence), which cannot be addressed exhaustively here (see, in general, Nagin 1998; Pratt, Cullen 2005; Pratt et al. 2006). In general, one can say that getting-tough-policy strategies (more police density and prosecution, increasing incarceration rates and the severity of punishment) have the lowest effects on crime rates (Pratt, Cullen 2005). Deterrence research differentiates between the perceived severity of punishment in case of reoffending and the certainty of being detected and reconvicted. It can be taken as a general validated result that certainty has a more important deterrent effect than the severity element. In general, criminal law and crime policy factors, as well as the sentencing practice, are of less importance than other social environment factors, such as social bonds etc. Pratt et al. (2006) reviewed 40 micro-level studies of deterrence and compared the factors of severity, certainty of punishment, deterrence theory composites and non-legal sanctions (loss of working place, negative consequences in the social environment). Severity and the deterrence composites factors had the lowest mean size effects compared to the factor certainty and, in particular, to non-legal factors. If further variables from other criminological theories are considered, such as self-control, peer-influences and the like, the strength of deterrence variables is further weakened. The factor “certainty” seems to have differential effects and is of more importance in the case of white-collar crime and of higher-level educated persons.

In taking these results into account, one may expect some deterrent effect of EM, as it increases the probability of being detected, in particular while being under GPS tracking. On the other hand, there are also negative effects, such as the stigmatization of wearing devices that persons in the public might recognize, or other restrictions of daily life that might endanger the compliance. For example, it was reported that the compliance for EM replacing pre-trial detention is lower because the time under EM, as an alternative to pre-trial detention, does not count for a prison sentence the offender may later receive in the court judgement.

Looking at the evaluation research on EM, Renzema and Mayo-Wilson come to the conclusion that EM may suppress the committing of crimes during the period under supervision but – with few exceptions – not beyond it (Renzema, Mayo-Wilson 2005, p. 231; Renzema 2013, p. 258 ff., 260 f.). Studies by Canadian scholars revealed that there was no reduction of crime for electronically supervised probationers compared to regular probationers supervised by conventional surveillance techniques (Wallace-Capretta, Roberts 2013, p. 51). Furthermore, the said scholars they state that “[a] significant proportion of the offenders who had been placed on EM had low-risk scores, and may well have been managed equally successful” by conventional probation supervision, which raises the question of net-widening (ibid, p. 51).

The result that reoffending during the EM-period remains the exception is consistent with the deterrence perspective under the realistic presumption that EM increases the risk of detection when being under electronic surveillance. However, as Renzema concludes also in his recent evaluation report, “EM is now mainly about punishment on the cheap, not rehabilitation. Yet, in the attempt to deter and punish humanely and inexpensive, most users of EM are not even trying to use it as a tool for rehabilitation” (Renzema 2013, p. 266). The studies existing so far for evaluating the effects of EM do not show any superior effect on preventing reoffending better than other traditional community sanctions, but quite a lot of problems in other areas of daily life (stress in the families, EM as a serious burden, possibly stigmatizing in the outside community etc.). This corresponds also with the evaluation of high-risk offenders under EM that was conducted by German scholars (see Bräuchle in Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017).

Another more favorable study was a Swedish project evaluated by Marklund and Holmberg (2009). However, the positive outcomes for EM-clients have to be seen in the Swedish rehabilitation model, as EM is embedded in the whole range of rehabilitative support (employment, housing and other probation and community services; see also Renzema 2013, p. 259; and Wennerberg 2013, p. 121 ff.). Another important research result is that EM is more promising for medium and high-risk offenders than for low-risk offenders, where no significant reduction of reoffending could be found (see Renzema, Mayo-Wilson 2005; Renzema 2013). As the commentary to the EM-Rules states,

Location monitoring technology cannot in itself bring about a change of attitude or behaviour in the way that a number of probation initiatives and programmes dealing with offending behaviour are designed to do. Some evidence suggests that wearing a monitoring device can have a ‘shaming effect’ but by itself this is insufficient to bring about long-term change. If reintegration and desistance are to be achieved electronic monitoring must be used in conjunction with measures which can accomplish this, tailored to individual offenders’ circumstances (drug treatment, alcohol treatment, anger management, employment skills training, helping with finding jobs and shelter, etc. (Council of Europe 2014, Commentary to Rule 8, referring to Wennerberg 2013, see above).

This result is also underlined by a recent study conducted in France by Henneguelle, Monnery, Kensey (2016). They compared EM-cases (all 580 cases in the years 2000–2003) with possibly eligible prisoners 5 years after release. The EM-cases showed a 14–15% lower recidivism rate than the ex-prisoners’ group. However, under control of a rather strong selection bias (EM-cases were on average lower-risk cases, more than the ex-prisoners’ group), only 6–7 percentage points of difference remained. The differential analysis showed that the main reasons for a lower recidivism rate of the EM group was that they were strongly supported by home visits of probation officers and employment programs that they had to participate in. Unfortunately, the study did not compare the alternative of suspended sentences with probationary supervision but without EM. The data indicate that the factors of probationary and other support probably had the major impact on reduced reoffending rates; therefore, it could be said that it is not EM but just the traditional care and supervision in the context of suspended sentences that make the difference in incarceration rates. This is plausible because the length of EM supervision on average was just 73 days (median: two months, see Henneguelle, Monnery, Kensey 2016, p. 650 ff.), and there were no differences in recidivism in the first and the later terms of supervision. During the later development of EM in France (after 2003), the practice of home visits almost totally disappeared, and the length of EM declined to less than 50 days in average, which might further undermine the claimed positive effects of EM (Henneguelle, Monnery, Kensey 2016, p. 655). So, the French data give no evidence that EM is superior to traditional forms of supervision by the probation service, although it may possess a potential in being superior to custody. The consequences with regards to the principle of proportionality are discussed in Part 8.

There is, however, some evidence (also in the French study) that there might be cases, in particular those of younger offenders, where EM could contribute to establishing daily routines and structures and could therefore help stabilize the lives of offenders who would otherwise not have completed their rehabilitative programs and who thereby benefit from them. This is somehow confirmed by the German project in Hesse, where, in individual cases, EM serves as a control that the supervised persons follow the activity plan agreed with the probation services when they go out (see Rehbein in Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017).

8. Perspectives for a proportionate and human

rights-based use of electronic monitoring

In summary, it is clear that EM is not a panacea – neither for reducing prison population rates nor for reducing reoffending rates or promoting the social integrating of offenders. It is the task of critical empirical research to explore under what conditions and with whom EM can play a constructive role in arriving at the aims described by its promoters. Beyond empirical evidence, the human rights approach has largely been neglected. EM is an intrusive measure and must be justifiable against less intrusive measures or sanctions. Therefore, policymakers should use EM only in cases where other community options are not sufficient or effective for reaching the abovementioned goals of preventing crime and promoting social reintegration.

A concrete policy recommendation would be to implement EM only in cases where (1) otherwise imprisonment would be unavoidable and (2) other community options would not be sufficient. The second part of the conditions under which EM can be acceptable is mostly neglected; therefore, a strong overuse of EM can be identified. The issue is not in why EM is “underused” and how to “further develop its potential,” which can be seen as the underlying research question of the abovementioned EU-funded project on “Creativity […] in the Use of EM […]” (Hucklesby et al. 2016), but how it can be reduced to a justifiable extend. Germany insofar should not be stigmatized as an outsider who has to reconsider its policy, but instead be seen as a country that has taken the principle of proportionality seriously as required per international standards and recommendations. A few countries in our research are in the same line, however not consequently enough in all aspects (see the example of Finland above).

If the principle of proportionality is taken seriously, EM must be used only in the few cases where no other alternative to custody is available or appropriate. The result in the Federal state of Hesse in Germany (trying to follow this approach) is that about 80 offenders out of 16 000 offenders under regular probationary supervision qualify for EM (without having excluded the net-widening effects in all cases).

Empirical evidence furthermore reveals that EM can only be promising in reducing reoffending if the electronic surveillance is embedded in the work of probation and aftercare services under the rehabilitative goal, as practiced in Sweden and the Netherlands (and, in a few cases, in Germany; see Dünkel, Thiele, Treig 2017a and Part 7 above). As a stand-alone sanction for low-risk offenders, EM is the policy and practice in England and Belgium, and therefore should definitely be rejected.

There is one other group of cases where EM can be justified. Again, Germany uses this option in a very restrictive manner for offenders who, for certain reasons (end of sentence, constitutional grounds, in particular – a disproportionate length of executing a preventive or psychiatric sentencing option), have to be released but who present a special and concrete danger for the life or health of others: the supervision of conduct order for “dangerous” offenders after having fully served their sentence (France and the Netherlands have similar options in their law). Important is the quantitative dimension. Out of about 37 000 offenders under supervision of conduct orders (see DBH 2016), about 60–70 are under electronic supervision, which may be justifiable for the sake of safety in the general society. The “Rechtsstaat,” however, must always be keen to provide regular reviews with regards to this kind of surveillance. The famous Dutch penologist, Constantijn Kelk, has always emphasized that prisoners, too (and today one must add: those released but under intensive supervision like EM), are “Rechtsburger” with their own human rights (“legal citizens,” see van Zyl Smit, Snacken 2009, 69 ff., which became the jurisprudence of the German Federal Constitutional Court since 1972).

Although Germany may be seen as an exception in this reductionist and human rights-oriented approach in using EM, it is worth to emphasize such penal values as the principle of proportionality in times where fashionable technical “solutions” claim to be promising perspectives.

References

Aebi, M. F., Chopin, J. (2014). SPACE II – Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics: SPACE II survey 2013. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

DBH, Fachverband für Soziale Arbeit, Strafrecht und Kriminalpolitik (2016). 40 Jahre Führungsaufsicht. Evaluation, Geschichte und Zahlen. DBH-Materialien Nr. 75. Köln: Eigenverlag DBH.

Dünkel, F. (2018). European Penology – The rise and fall of prison population rates in Europe. European Journal of Criminology 14 (in preparation). https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370817733961

Dünkel, F., Thiele, C., Treig, J. (2017). Elektronische Überwachung von Straffälligen im europäischen Vergleich – Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven. Mönchengladbach: Forum Verlag Godesberg.

Dünkel, F., Thiele, C., Treig, J. (2017a). “You’ll never stand-alone”: Electronic monitoring in Germany. European Journal of Probation 9, p. 28–45. Internet-publication: http://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/kpuVBex3FqFAuF2yZkSm/full. https://doi.org/10.1177/2066220317697657

Haverkamp, R. (2014). Electronic monitoring. In: Bruinsma, G., Weisburd, D. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. London, New York: Springer, p. 1329–1338. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5690-2_570

Henneguelle, A., Monnery, B., Kensey, A. (2016). Better at Home than in Prison? The Effects of Electronic Monitoring on Recidivism in France. Journal of Law and Economics 59, p. 629–676. https://doi.org/10.1086/690005

Hucklesby, A. (2008). Vehicles of Desistance? The impact of electronically monitored curfew orders. Criminology and Criminal Justice 8, p. 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895807085869

Hucklesby, A., et al. (2016). Creativity and Effectiveness in the Use of Electronic Monitoring as an Alternative to Imprisonment in EU Member States. Final Report. Internet publication: http://emeu.leeds.ac.uk/.

Marklund, F., Holmberg, S. (2009). Effects of early release from prison using electronic tagging in Sweden. Journal of Experimental Criminology 5, p. 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-008-9064-2

Nagin, D. S. (1998). Criminal Deterrence Research at the Outset of the Twenty-First Century. In: Tonry, M. (Ed.). Crime and Justice: A Review of Research. Vol. 23. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1086/449268

Nellis, M. (2014). Understanding the Electronic Monitoring of Offenders in Europe: expansion, regulation and prospects. Crime, Law and Social Change 62, p. 489–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-014-9540-8

Nellis, M. (2015). Standards and Ethics in Electronic Monitoring. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

Nellis, M. (2017). Die elektronische Überwachung von Straftätern: Standards, ethische Grundlagen und Kriminalpolitik im digitalen Zeitalter. In: Dünkel, F., Thiele, C., Treig, J. Eds.). Elektronische Überwachung von Straffälligen im europäischen Vergleich – Bestandsaufnahme und Perspektiven. Mönchengladbach: Forum Verlag Godesberg, p. 267–289. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-00430-4/22

Page, J. (2013). Punishment and the Penal Field. In: Simon, J., Sparks, R. (Eds.). The Sage Handbook of Punishment and Society. Los Angeles et al.: Sage, p. 152–166. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446247624.n8

Pratt, T. C., Cullen, F. C. (2005). Assessing Macro-Level Predictors and Theories of Crime: A Meta-Analysis. In: Tonry, M. (Ed.). Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, Vol. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 373–450. https://doi.org/10.1086/655357

Pratt, T. C., Cullen, F. T., Blevins, K. R., Daigle, L. E., Madensen, T. D. (2006). The empirical status of deterrence theory. In Cullen, F. T., Wright, J. P., Blevins, K. R. (Eds.). Taking stock: The status of criminological theory, advances in criminological theory. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, p. 367–395. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315130620-14

Renzema, M. (2013). Evaluative Research on Electronic Monitoring. In: Nellis, M., Beyens, K., Kaminski, D. (Eds.). Electronically Monitored Punishment: international and critical perspectives. London: Routledge, p. 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv016

Renzema, M., Mayo-Wilson, E. (2005). Can Electronic Monitoring Reduce Crime for Medium to High Risk Offenders? Journal of Experimental Criminology 1, p. 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-005-1615-1

van Zyl Smit, D., Snacken, S. (2009). Principles of European Prison Law and Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wallace-Capretta, S., Roberts, J. (2013). The evolution of electronic monitoring in Canada. From corrections to sentencing and beyond. In: Nellis, M., Beyens, K., Kaminski, D. (Eds.). Electronically Monitored Punishment: international and critical perspectives. London: Routledge, p. 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-014-9541-7

Wennerberg, I. (2013). High level of support and high level of control. In: Nellis, M., Beyens, K., Kaminski, D. (Eds.). Electronically Monitored Punishment: international and critical perspectives. London: Routledge, p. 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azv016

Elektroninė stebėsena Europoje – panacėja reformuojant baudžiamųjų sankcijų sistemas? Kritinė apžvalga

Frieder Dünkel

Santrauka

Pirmieji bandymai taikyti elektroninę stebėseną (monitoringą) Europoje prasidėjo praėjusio amžiaus dešimtojo dešimtmečio pradžioje. Pastaruosius 15 metų dauguma Europos šalių skelbia taikančios elektroninę stebėseną ar bent jau bandomąsias jos versijas. Tokį stulbinamą elektroninės stebėsenos pakilimą Europoje galima aiškinti komerciniu interesu, kuris tampa akivaizdus, žvelgiant į privačių įmonių, parduodančių įrangą, veiklą. Nors atrodytų, kad elektroninė stebėsena paplito daugelyje šalių, būtina suprasti, kad ji Europos sankcijų sistemose atlieka nereikšmingą vaidmenį palyginti su kitomis bausmių ar paleidimo iš laisvės atėmimo vietų alternatyvomis. 2013 m. duomenimis, vidutiniškai tik apie 3 proc. visų probuojamų asmenų buvo stebimi elektroniškai. Šiame straipsnyje nagrinėjami klausimai, susiję su elektroninės stebėsenos įtaka kalėjimų populiacijos dydžiui ir sumažėjusiam pakartotinių nusikaltimų skaičiui, su besiplečiančio stebėsenos tinklo pasekmėmis ir kaštais, būtina reabilitacine pagalba, žmogaus teisėmis grįstomis perspektyvomis ir apskritai elektroninės stebėsenos (ne)prasmingumu.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: elektroninė stebėsena (monitoringas), bausmė, tarptautiniai standartai, žmogaus teisės, kriminalinė justicija.