Kriminologijos studijos ISSN 2351-6097 eISSN 2538-8754

2024, vol. 12, pp. 33–74 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/CrimLithuan.2024.12.2

Frieder Dünkel

Prof. em. Dr., University of Greifswald, Department of Criminology

E-mail: duenkel@uni-greifswald.de

Internet: http://www.rsf.uni-greifswald.de/duenkel.html

Wolfgang Heinz

Prof. em. Dr., University of Konstanz

E-mail: wolfgang.heinz@uni-konstanz.de

Internet: http://www.jura.uni-konstanz.de/heinz/

Gintautas Sakalauskas

Assoc. Prof. Dr., Vilnius University, Faculty of Law, Department of Criminal Justice

E-mail: gintautas.sakalauskas@tf.vu.lt

Internet: http://web.vu.lt/tf/g.sakalauskas/

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0203-5496

Abstract. The incarceration rate of a country is indicative of the nature of its penal policy and the degree of repression it entails. Even in European countries, there is considerable variation. Furthermore, there are disparate trends in its evolution, which elicit disparate responses from different countries. In some countries, low prison populations are regarded as a significant indicator of a moderate and rational penal policy. As they begin to rise, efforts are made to identify strategies for reducing them. Conversely, in other countries, they are accorded less attention until overcrowding becomes a problem. Criminological research indicates that imprisonment is an ineffective and detrimental practice and should only be employed as a last resort with the objective of facilitating resocialisation. The number of individuals incarcerated on an annual basis in a specific country is primarily contingent upon political decisions. A comparison of prison populations and penal policy measures in different countries provides a more nuanced understanding of the effectiveness of the measures taken and allows for a more informed assessment of the need for, and potential for, reform in one’s own country in the context of another. This paper analyses punishment practices and trends in prison populations in Germany and Lithuania in comparison to other European countries. Despite political change and various social and economic developments, Germany has been characterised by a stable and declining prison population in recent years. This example is pertinent to countries that have invested significant resources into reducing their prison populations, such as Lithuania and other Baltic countries, and has achieved notable success. It is also relevant to countries where the prison population has shown a marked increase in recent years. The paper aims to explain the reasons for declining prison populations in Germany and Lithuania and to identify effective strategies and measures that can be implemented to ensure a consistent and sustained reduction in the prison population.

Keywords: prison population rates, sentencing and imprisonment, crime policy, criminal justice, Germany, Lithuania, Europe

Santrauka. Kalinių populiacijos lygis rodo šalies baudžiamosios politikos pobūdį ir represyvumo laipsnį. Visgi net Europos šalyse šis rodiklis labai skiriasi. Skirtingos ir jo raidos tendencijos, į kurias šalys vėlgi reaguoja labai skirtingai. Vienose šalyse mažas kalinių skaičius laikomas svarbiu nuosaikios ir racionalios baudžiamosios politikos rodikliu. Kai jis pradeda didėti, stengiamasi rasti būdų jį sumažinti. Kitose šalyse kalinių skaičiaus didėjimui skiriama mažiau dėmesio, kol kalėjimų perpildymas netampa problema. Kriminologiniai tyrimai rodo, kad įkalinimas yra neveiksminga ir žalinga praktika, kuri turėtų būti taikoma tik kraštutiniu atveju, siekiant įkalintųjų resocializacijos. Konkrečioje šalyje įkalinamų asmenų skaičius pirmiausia priklauso nuo politinių sprendimų. Palyginus įvairių šalių kalinių skaičių ir baudžiamosios politikos priemones, galima geriau suprasti taikomų priemonių veiksmingumą ir geriau įvertinti reformų poreikį ir galimybes savo šalyje, atsižvelgiant į kitos šalies patirtį. Šiame straipsnyje analizuojama bausmių taikymo praktika ir kalinių skaičiaus tendencijos Vokietijoje ir Lietuvoje, jos lyginamos su kitomis Europos šalimis. Nepaisant politinių, socialinių bei ekonominių pokyčių, pastaraisiais metais Vokietijoje kalinių skaičius yra stabilus ir mažėja. Šis pavyzdys yra aktualus šalims, kurios įgyvendino ir toliau ketina įgyvendinti įvairias kalinių skaičiaus mažinimo priemones, pavyzdžiui, Lietuva ir kitos Baltijos šalys pasiekė gerų rezultatų. Jis taip pat aktualus šalims, kuriose pastaraisiais metais kalinių skaičius žymiai padidėjo. Straipsnio tikslas – paaiškinti kalinių skaičiaus mažėjimą Vokietijoje ir Lietuvoje lemiančius veiksnius ir nustatyti veiksmingas strategijas bei priemones, kurias galima įgyvendinti, siekiant užtikrinti nuoseklų ir tvarų kalinių skaičiaus mažėjimą ilgalaikėje perspektyvoje.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: kalinių populiacijos lygis, bausmių taikymas ir įkalinimas, baudžiamoji politika, baudžiamoji justicija, Vokietija, Lietuva, Europa.

_______

Received: 25/10/2024. Accepted: 28/11/2024

Copyright © 2024 Frieder Dünkel, Wolfgang Heinz, Gintautas Sakalauskas. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The comparative analysis of the development of prison population rates and overcrowding has a long tradition in Europe. It started with the data collection by the Council of Europe in the early 1980s, first editing the ‘Prison Information Bulletin’, later by transforming it to the SPACE, annual statistics under the guidance of Marcelo Aebi (see recently Aebi, Cocco, Molnar, 2023). Another source of evidence are the data collections of the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research of Birkbeck University of London under the Heading of ‘World Prison Brief’1. The following analysis is based on these databases as well as on the European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics (Aebi et al., 2021).

On the basis of the descriptive data, we try to find explanations for the German and Lithuanian development of prison population rates in a European comparative perspective. We try to link the German and the Lithuanian prison population data with the development of criminal justice policy, sentencing practices and the underlying development of crime rates. We do not go into a detailed analysis of the sociological and political-science approaches2 on punitiveness and ‘penality’, as the German and Lithuanian development in particular may be understood quite well by studying crime policy and penal theory/human rights factors which have influenced the developments of the last 60 years in Germany3 and last 35 years in Lithuania4. Both countries could be taken as examples for explaining effective strategies to reduce prison population rates across Europe.

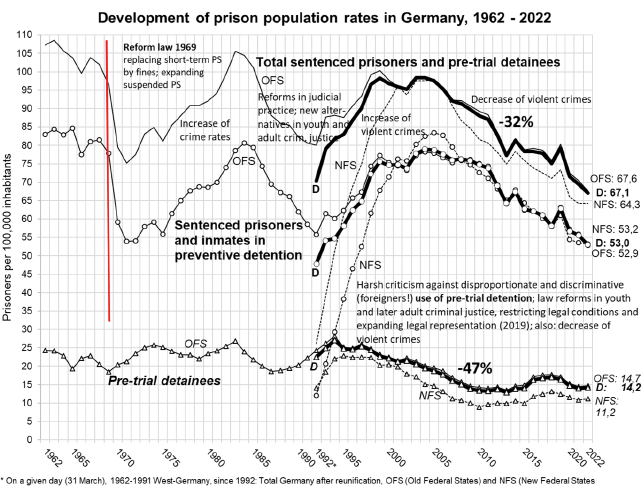

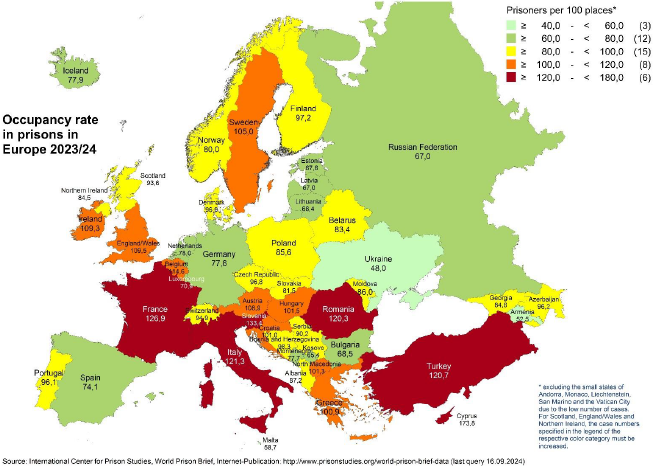

Germany – like some other European countries, including Lithuania – has experienced a major decline of the prison population rate (-32% since 2003. In Lithuania the decrease of -59% since 1999 is even more impressive, see Figures 1 and 5 below). Overcrowding therefore is not a problem. The occupancy rate in Germany 2023 was 77.6%, the situation is therefore quite relaxed as regards prison overcrowding. The occupancy rate in Lithuanian prisons were even lower (68.4%), unfortunately, this has not improved the conditions of detention very much (CPT 2023; 2024)5.

The long-term development of the prison population rate since the 1960s in Germany was influenced by a strong orientation to using imprisonment as a last resort and to the principle of ‘resocialisation’, which is enshrined in the jurisprudence of the Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht)6. Penal law reforms during the 1960s and 1970s to replace short-term imprisonment (up to 6 months) by fines (1969), and to expand suspended sentences (probation) (1969 and 1986) and youth justice reforms (1953 and 1990) were of major importance for a long-term decline of the prison population. Youth justice reforms expanded the application of the Youth Justice Act to 10-20-years-old young adults in 1953 already. The court practice widened the application considerably, in 1990 a major law reform expanded diversion and introduced a variety of alternative ‘educational’ sanctions. Later reforms in the 2000s counteracted the liberal approach only in some more or less marginal details, the educational and minimum intervention approach (and declining youth crime rates) contributed to a decrease of the youth prison population rate from 2001–2022 by 55% (Dünkel, Geng, Harrendorf, 2023; Heinz, 2023a).

The adult criminal justice law reform of 1969 contributed to a decline of short-term imprisonment (up to 6 months), which was replaced by fines. This trend was counteracted by the increase of crime rates in the 1970s, followed by a decisive crime policy to expand alternatives (suspended sentences and new community sanctions in youth justice, extending alternatives to pre-trial detention). The development culminated in the new Youth Justice Act (YJA) in 1990. This year was also the year of the reunification of Germany resulting in many problems of East Germany in transition and an increasing rate of violence (not only, but particularly in East Germany). The harsh criticism against discriminatory use of pre-trial detention in the early 1990s, a large societal interest in violent crime prevention and the decrease of violent crimes since about 1995, and especially since the early 2000s, contributed to the overall decline of the total prison population by 32% and of the pre-trial detainees’ population rate by 47% (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Development of prison population rates in Germany 1962–2022

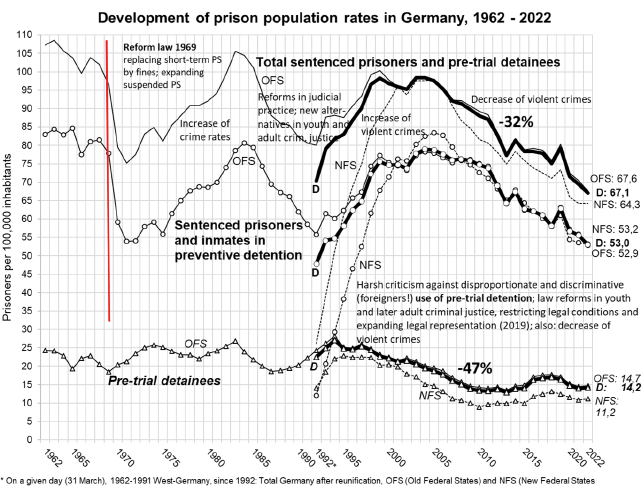

The general trend of declining prison population rates can be differentiated according to the individual Federal States. Hamburg and Berlin with a strongly urban population and higher crime rates used to have over-average prison population rates, but since 2003 and 2009 they have shown a remarkable decline, resulting in prison population rates close to the German average. Schleswig-Holstein – apart from its moderate crime rates – always followed a declared crime policy to avoid imprisonment, resulting in a prison population rate of less than 40 per 100,000 inhabitants, i. e. 45% below the German average (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Prison population rates in the German federal states, 1992–2022

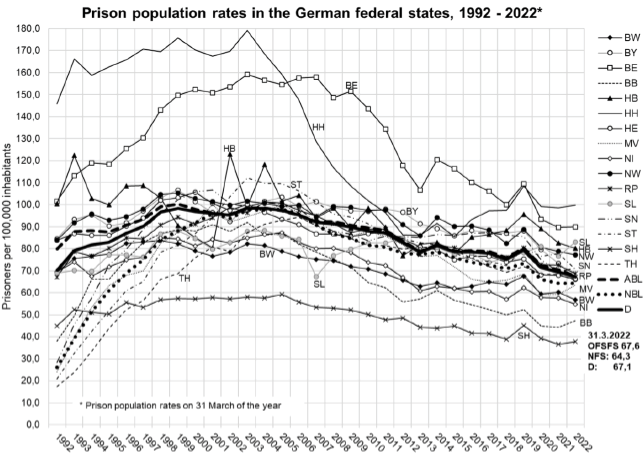

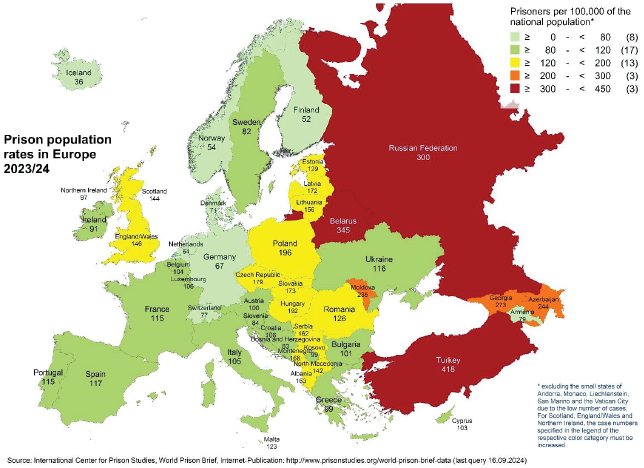

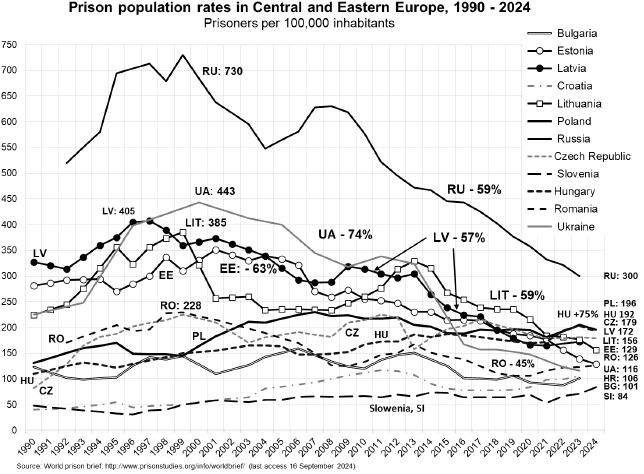

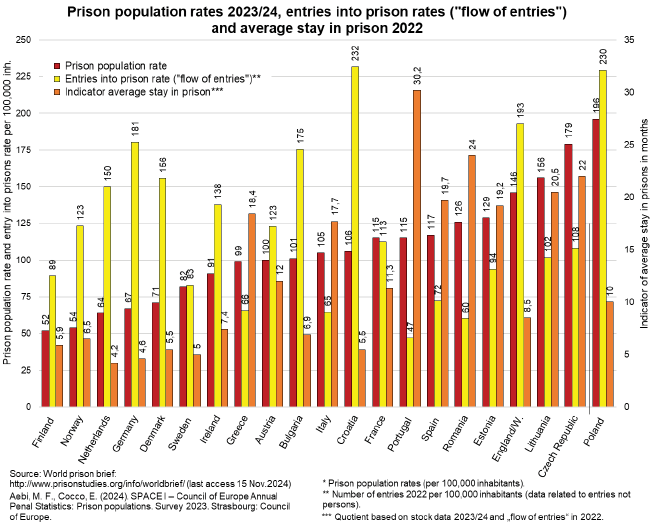

Prison population rates in 2023/24 differed in the range from 36 in Iceland, 52 in Finland, 54 in Norway up to 300 in Russia, 345 in Belarus (data available only up to 2018) and 418 in Turkey (Figure 3). Many scholars have attempted to explain these huge differences. In general, one can summarise the evidence that crime developments in most cases are not the main factor (Aebi, Linde, Delgrande, 2015)7 but rather political and socio-economic indicators as well as social and penal policy factors (Dünkel, 2017; Lappi-Seppälä, 2020; Brandariz, 2021).

Resisting punitiveness can also be linked to a strong orientation to preserve the human rights of prisoners (see the example of Germany) and a policy influenced by human rights standards, such as the principle to use imprisonment as a very last resort (Snacken, 2012; Snacken, Dumortier, 2012).

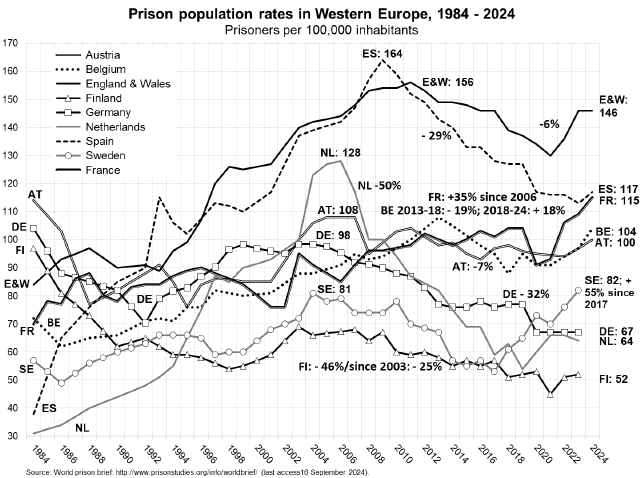

Germany (prison population rate of 67 in 2023 and 2024) has since the 2010s been among the states with a low level of prison population. Belgium’s prison population rate of 104 in 2024 was 55% higher than the German one. The development in these countries went in opposite directions. In the 1980s, the Belgian rate was around 30% lower than the German one. While the German rate declined and increased slowly later in the 1990s, the Belgian rate experienced a steady increase, overtaking the German one in 2007, and remained considerably higher in spite of a small decrease from 2012–2018. The last 6 years are the cause of the real difference of today: Germany continued to reduce its prison population during the Covid pandemic8, whereas in Belgium an increase after Covid counteracted the positive development of the former period (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 3. Prisons population rates in Europe 2023/24 (World Prison Brief)

The Western European trends are contradictory in their development from 1984–2024 (see Figure 4). Countries with a low level of imprisonment like the Netherlands and Spain, saw a decrease in their prison population rates: in the case of the Netherlands to an under-average level (64, = -50%) and a slightly above average level in Spain (117, = -29%), while in England/Wales, from an elevated starting point, the prison population rate continued its above average trend to reach the highest Western European prison population rate of 146 in 2024). There seem to be no attempts to reduce the prison population; on the contrary, the government plans a huge expansion of the prison system (Dünkel, Harrendorf, Geng, 2024).

FIGURE 4. Prisons population rates in Western Europe, 1984–2024 (World Prison Brief)

It is not possible in the context of the present paper to outline the different developments and historical phases in other Western and Eastern European countries (see Figure 5), but the remarkable reduction in prison populations in the Eastern European countries can be seen as a sign that the political will to manage the size of the prison system, supported by a decline of (in particular violent) crime rates, is successful. The strong decrease in the Baltic states since the 1990s and early 2000s (-59% in Lithuania, -57% in Latvia, and -63% in Estonia) is an expression of a crime policy oriented to abandoning the mass incarceration of Soviet times. Even Russia itself has changed its penitentiary policy (-59% since 1999), although the reduced prison population rates must be in part related to the massive expansion of the military complex since the early 2010s and the war against Ukraine (Dünkel, 2017; Dünkel, Harrendorf, Geng, 2024).

FIGURE 5. Prison population rates in Central and Eastern Europe, 1990–2024 (World Prison Brief)

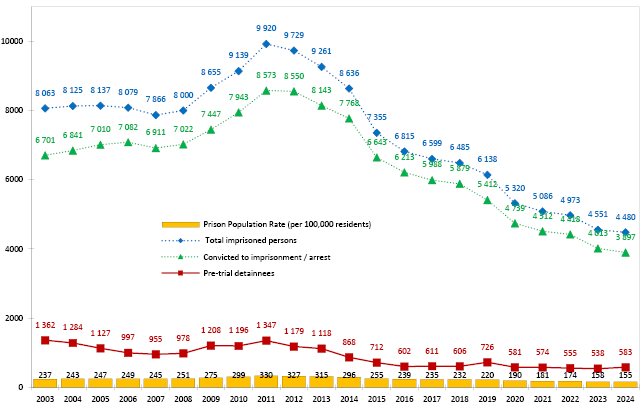

Nevertheless, it is challenging to ascertain whether the considerable decline in the incarcerated population in countries with a Soviet legacy, whose penal policy was typified by a pronounced degree of punitiveness (Sakalauskas, 2019a; 2019b) can be attributed primarily to a profound transformation in the underlying principles. While there is no straightforward correlation between the number of prisoners and general crime rates, a reduction in the incidence of serious crimes can contribute to a decline in the prison population (Figure 6). For example, in Lithuania, the number of individuals suspected or accused of criminal offences decreased by 25–29% between 2012–2013 and 2023. This decline is even more pronounced when considering serious and very serious offences, with a reduction of 29–33% over the same period, the number of individuals suspected or accused of perpetrating serious and very serious criminal acts decreased by approximately 1,700, representing a 17% reduction (10,266 in the 2014–2018 period and 8,525 in the 2019–2023 period). This decline was accompanied by a notable decrease in the number of new prison entries. The number of individuals sentenced to incarceration for homicide declined by 1,200, representing a 71% reduction (1,785 in the 2014–2018 period and 622 in the 2019–2023 period). The number of homicides registered per year in Lithuania has decreased by more than fivefold over the past 20 years (from 390 in 2005 to 73 in 2023). This decline has been particularly pronounced among prisoners convicted for a homicide, who constituted approximately 25% of the total prison population during this period. Consequently, the overall reduction in the prison population has been significantly influenced by this decrease. Furthermore, the number of serious injuries has decreased by a factor of three over the same period, while the number of robberies has decreased by a factor of fifteen. It appears that the reduction in the number of serious crimes in Lithuania has had a more significant impact on the decline in the prison population than the implementation of new legislative measures (with the exception of the reform of 2019 with the extension of electronic monitoring as a back-door strategy to shorten the part to be served in prison, see below). The temporary increase of the prison population rate between 2008 and 2011 can be attributed to the economic crisis and an increase also of longer sentences imposed and to be served, see below).

FIGURE 6. Prisoners in Lithuania, 2003–2024 (one-day snapshots at the end of every year, absolute numbers and prison population rates per 100,000 residents); Statistics of the Lithuanian Prison Service

As a result of the contradictory developments with recently increasing prison population rates in Belgium (+18% since 2018), France (+35% since 2006), Greece, Italy (+21% since 2015), Turkey9, but also in Sweden (a traditionally low-level country within the group of Scandinavian countries, +55% since 2017), overcrowding has become a serious problem in these countries (see Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. Occupancy rate in prisons in Europe 2023/2024 (World Prison Brief)

Overcrowding is defined by an occupancy rate of more than 100 prisoners per 100 places/beds, but in reality, an occupancy rate of more than 85% already means a full capacity utilisation. According to the data of the Institute of Crime & Justice Policy Research of Birkbeck University in London, in September 2024 15 out of 45 European countries (33.3%) had an occupancy rate of more than 100%, and 24 countries (= 53.3%) an occupancy rate of more than 90%10, which implies a ‘structural’ overcrowding (see above) and regularly sharing the cell with at least one or two co-inmates. The situation is most dramatic in Austria, Ireland (109 prisoners per 100 places), England/Wales (110), Belgium (115), Romania (120), Italy, Turkey (121), France (127), Slovenia (133), and Cyprus (174). Not all countries in this ‘ranking’ are high-level incarceration countries (e.g. Slovenia, Ireland), but most of them are faced by multiple socio-political and economic problems including migration and by tensions between different groups of the society.

Therefore, one must conclude that the majority of European prison systems has to struggle against overcrowding and that the development of strategies to downsize prison population rates is of major importance.

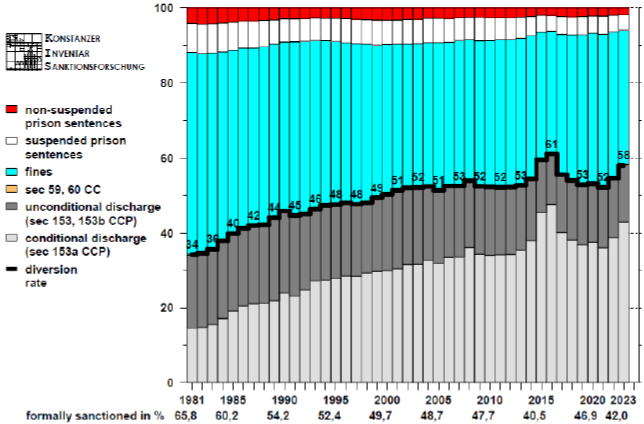

The German Criminal Procedure Act (CPA) and Penal Code (PC) provide for a rather poor system of sanctions and measures. According to § 153 ff. CPA petty offences can be dismissed (by the prosecutor or court), reform laws in the 1970s-1990s expanded diversion to middle range crimes, (if the ‘gravity of’ the offence or ‘guilt does not demand a formal adjudication’). In more serious cases, the dismissal may depend on the fulfilment of obligations such as monetary payments, an excuse or Victim-offender-mediation etc. This has led to an increase of the diversion rate from 34% in 1981 to 58% in 2023 (see Figure 8). In addition, the proportion of suspended sentences has increased (see Heinz, 2017; 2023; 2023a, see Figure 10).

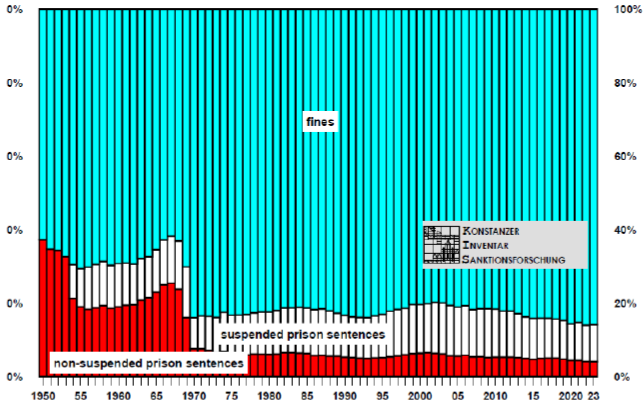

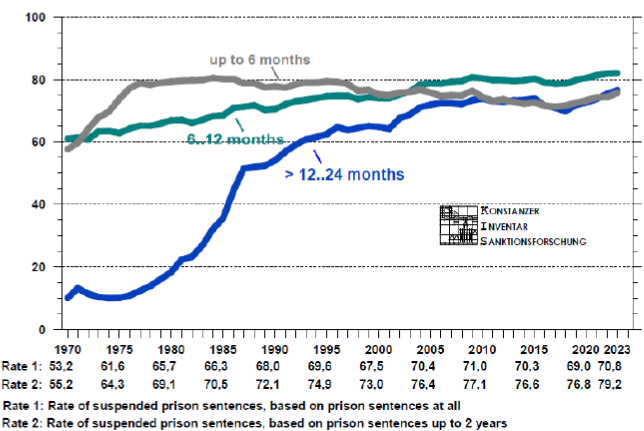

Although more than half of the cases are dismissed (mostly) at the pre-trial stage, the sentencing practice by the courts reveals a long-term decrease in unconditional prison sentences. The structure of the adult criminal justice system is rather simple (see Figure 9): Fines are the predominant sanction (2023: 85.8%), followed by suspended sentences (up to 2 years; 2023: 10.0%) and unconditional prison sentences of up to 15 years or life imprisonment (with the possibility of conditional release after 15 years) (2023: 4.1%). In addition to the increase of the use of fines, the proportion of suspended sentences as part of all prison sentences of up to 2 years increased from 55% to 79% for adults (see Figure 10) and from 55% to 74% in the youth justice system.

Community service does not exist as an independent sanction, but only as a substitute sanction to avoid fine default imprisonment.

Electronic monitoring is not seen as an appropriate (and proportionate) alternative sanction. It is restricted to a few cases of ‘dangerous’ offenders (mostly after release from preventive detention or psychiatric institutions or having served their full sentence and being evaluated as still ‘dangerous’).

FIGURE 8. Informal (diversion) and formal (court) sanctions in the adult criminal justice system in Germany, 1981–2023

FIGURE 9. Sentencing practice of criminal courts for adults in Germany, 1950–2023

FIGURE 10. Proportion of suspended prison sentences in relation to all and to prison sentences eligible for suspension (up to 2 years) in Germany, 1970–2023

TABLE 1. Length of unconditional prison sentences for convicted offenders according to the penal law for adults in Germany, 2008 and 2023

|

Year |

Convicted offenders – unconditional prison sentences |

PS –6 months, |

6 months –1 year |

1–2 years |

2–3 years |

3–5 years |

5–10 years |

10–15 years |

life im-prison-ment |

|

2008 |

41,239 |

27.8 |

30.1 |

15.8 |

12.7 |

8.9 |

4.0 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

|

2023 |

25,335 |

15.7 |

28.8 |

19.1 |

15.8 |

12.6 |

7.2 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

The absolute number of unconditional prison sentences decreased from 2008–2022 by 38.6%. Short-term sentences of up to 6 months decreased, while middle range sentences from 2-5 years increased (see Table 1), but, to a large extent, this can be explained by a changing crime structure (fewer petty offences and more serious crimes are sent to courts) and not by a more punitive sentencing practice (see Heinz, 2017; 2023). To some extent law reforms increasing the minimum prison sentences for sexual crimes since the mid-1990s may have had an impact.

The length of time served in prisons in a European comparison varies considerably. Figure 11, based on SPACE I-data (see Aebi et al. 2024) reveals that the average length in Germany was 4.7 months in contrast to 7.4 months in Belgium and 31.7 months in Portugal. These data represent all entries into prisons, also those in pre-trial detention. They can only be used indirectly as an indicator of the length of sentences imposed by the courts, but they reflect the flow of entries and length of actual stay in prisons. The administrative workload of prison staff is much influenced by the numbers of persons entering the prison system (flow of entries and releases).

FIGURE 11. Average length of imprisonment in months, SPACE I-data (see Aebi et al. 2021)

The first national Criminal Code of the Republic of Lithuania (CC) came into force on 1 May 2003 along with the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Code of Execution of Penalties (CEP). The main aim of the new legislation was to create a new penalty system with a wider range of sanctions, which allow more flexible and proportional reactions to the different types of crimes (see Čepas, Sakalauskas, 2010; Sakalauskas, 2014; 2019a; 2019b; 2021; 2025). In the last 20 years the Criminal Code has been amended almost 100 times, including also changes in the criminal sanctions system. It shows an instability of criminal policy, mostly caused by initiatives for “better deterrent reactions” to crimes and for reducing criminal behaviour. The last major amendment to the General Part of the Criminal Code was adopted in April 2024 and will come into force on 1 February 2025 (see in detail below).

According to the Criminal Code11, a penalty shall be a ‘measure of compulsion’ applied by the State, which is imposed by a court’s judgement upon a person who has committed a crime or misdemeanour (Para 1, Article 41). The actual redaction (from February 2025) of the Criminal Code provides the following 6 penalties for natural persons:12

1) community service for a period from one month up to one year for 10–40 hours per month with a maximum of 480 hours for a crime and 240 hours for a misdemeanour in total (Articles 42, 46 CC); the penalty of community service may be imposed only with the consent of the accused person;

2) a fine in the amount from 15 to 6 000 minimum standards of living (MSLs)(Articles 42, 47 CC) for crimes of varying severity; since the 1st of January 2018 the one minimum standard of living is 50 euros, so the maximum of a fine for a grave crime is 300,000 euros; even the maximum of a fine for a minor crime is 100,000 euros – 10 times more than the average of annual personal (net) income in Lithuania; one of the main shortcomings of the regulation and application of the fine penalty in the Lithuanian criminal law system is that the amount of the fine penalty is not directly linked to the income of the person being tried, as is the case in Germany (day-fine, in German – Tagessätze); where a person does not possess sufficient funds to pay a fine imposed by a court, the court may replace this penalty with community service (Para 7, Article 47 CC); where a person evades voluntary payment of a fine and it is not possible to recover it, a court may replace the fine with restriction of liberty (Para 8, Article 47 CC); it is one of very positive amendments of the Criminal Code, which came into force on the 5th of July 2019, that there is no replacement of evaded fine with an arrest penalty provided;

3) restriction of liberty for a period from three months up to two years (Articles 42, 48 CC); the persons sentenced to restriction of liberty shall be usually under control of the electronic monitoring and under the different obligations and prohibitive injunctions; where a person evades the serving of the penalty of restriction of liberty, this penalty shall be replaced with arrest (Para 8, Article 48 CC);

4) arrest for a period of 15 to 90 days for a crime and of 10 to 45 days for a misdemeanour (Articles 42, 49 CC); the court may suspend an arrest penalty imposed for a first time committed criminal offence for a period of three months up to one year and may impose (before 1 February 2025 it was a “must”-obligation) an electronic monitoring for this period together with other penal sanctions or obligations (Para 1, Article 75 CC);

5) fixed-term prison sentence for a period of three months to 20 years (Articles 42, 50 CC); the court may suspend a custodial sentence of up to four years for one or several minor crimes or less serious13 premeditated crimes and up to six years for one or several crimes committed through negligence; the court may suspend the execution of the imposed sentence for a period ranging from one year up to three years; the execution of the sentence may be suspended where the court rules that there is a reasonable ground for believing that the purpose of the penalty will be achieved without the sentence actually being served; since the 5th of July 2019 there is also a possibility to suspend a part of a custodial sentence, but just for crimes committed through negligence of more than six years, also a custodial sentence of more than four years for one or several minor crimes or less serious premeditated crimes, even a possibility to suspend a part of custodial sentence up to five years for some serious crimes (Para 3, Article 75 CC);

6) life sentence; until April 2019 the Lithuanian law did not provide for (early) release in life custodial cases, it was possible just like an exception by a way of an amnesty (Article 78 CC) or clemency (Article 79 CC); according to the judgment of 23 May 2017 of the European Court for Human Rights this regulation had been held as a violation of the Article 3 of the Convention of Human Rights;14 there is now a possibility after 20 years served sentence to replace it with fixed-term sentence for a period of 5 to 10 years with a possible early release after a half of the sentence served (Sakalauskas 2021; 2025).

All these penalties shall be imposed by the court in the case provided for in the Special Part of the Criminal Code. Only one penalty may be imposed on a person for the commission of one crime or misdemeanour15 (Para 3, Article 42 CC).

The purpose of a penalty shall be: 1) to prevent persons from committing criminal acts; 2) to punish a person who has committed a criminal act; 3) to deprive the convicted person of the possibility to commit new criminal acts or to restrict such a possibility; 4) to exert an influence on the persons who have served their sentence to ensure that they comply with the law and do not reoffend,; 5) to ensure implementation of the principle of justice (Para 2, Article 41 CC). This eclecticism of different purposes makes it possible to impose very different penalties, because the main purpose is not clear, all the more so as one of the purposes is simply to punish a person who has committed a criminal act. Nevertheless, the Code of Execution of Penalties (CEP) in Para 2, Article 1 establishes just one general purpose, the resocialization (re-integration) of convicts – the promotion of a person’s ability to ‘live a law-abiding life’ (see more Sakalauskas 2019b).

An adult person released from criminal liability or released from a penalty (probation) or early released from a correctional institution may be subject to additional penal ‘sanctions’ (obligations, directives or restrictions of liberty, Para 2, Article 67 CC), such as restrictions in employment, directives to pay compensation to the victim or a crime victim fund, to community service, or to participate in rehabilitative and/or drug and alcohol prevention programmes16.

According to the Para 1, Article 67 CC penal ‘sanctions’ (obligations etc.) must support the purpose of a penalty. This statement is controversial, because the main idea of penal ‘sanctions’ was to create a system of measures instead of penalties. The original version of the Criminal Code, which came into force on 1 May 2003, provided only five of actual 12 penal ‘sanctions’ and only the confiscation of property might be imposed together with a penalty. Actually, all penal ‘sanctions’ can be imposed together with a penalty, with an exception of a payment to the fund of crime victims, which cannot be imposed together with a fine.

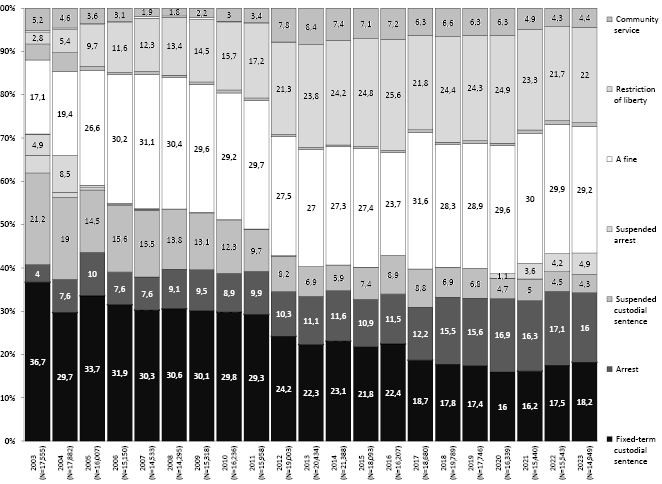

Figure 12 shows, that in 2012–2023 the custodial sanctions (arrest and fixed-term prison sentences) accounted for about 33% of all sentences. Furthermore, for about 5-10% of suspended fixed-term custodial sanctions were revoked because of non-compliance with the conditions of the probation sentence. Also, approximately 5% of the sentence of restriction of liberty because of non-compliance were replaced by the arrest penalty. So, at the end the part of prison sentences is even a few percent higher than 33%.

FIGURE 12. Penalties imposed for sentenced persons in the first courts level in Lithuania 2003–2023 (percentages); Statistics of the Lithuanian National Courts Administration17

For the period 2003–2011 after the new Criminal Code was in place, the penalty of restriction of liberty has become not an alternative to custodial sentences but a replacement for suspended custodial sentences, which in 2011 comprised only about 10% (1,543 of 15,958 penalties) compared with 21% in 2003. Fines increased during this time from 17% to 30% of all penalties imposed. Unfortunately, there are no statistics in Lithuania about the amount of the fines imposed and about fines replaced by fine default imprisonment (concerning convicts not able or not willing to pay the fine).

At the end of 2011 the new Law on protection against domestic violence came into force and it caused ‘a tectonic refraction’ in the structure of applied penalties. According to the new law all cases of domestic law became a social significance and must be prosecuted without the complaint of the victim. This new regulation caused approximately 10,000 new suspected persons, approximately 40% of them were sentenced, mostly to a non-custodial sentence or arrest.

Another important new amendment of the Criminal Code was the criminalisation of driving a vehicle under the influence of alcohol, where the blood alcohol level exceeds 1.5 per mil (Para 7, Articles 281 CC and later – Article 281(1) CC). Such persons shall be punished by a fine or by arrest or by a custodial sentence for a term of up to one year. But the big part of these suspected approximately 6,000 persons per year were also released from criminal liability and penal ‘sanctions’ (obligations etc., see above) were imposed.

It is difficult to explain the rising and fall of prison population rates by the sentencing practice as shown in Figure 12, because the proportion of unconditional prison sentences since 2003 is in a steady decline. However, the explanation may be found by the changing length of prison sentences imposed by the courts, which increased from an average of 59 months in 2003 to 70 in 2011 and 87 in 2020 (+47%). A slight reverse trend can be seen by a reduction of the average length of unconditional prison sentences to 82 months in 2023 (see Sakalauskas 2024a, 144, Fig. 24). A further explanation of the increase of the time served before a release: The proportion of those prisoners serving the full time of their sentence raised from 40% in 2005 to 80% in 2019. After the reform of 2019 with the increased possibility to replace the last quarter of the sentence by electronic monitoring the proportion of prisoners fully serving their sentence fell to 50% (see Figure 92 in Sakalauskas, 2024b, 81), which explains in part the strong decline of the prison population during the last few years (see above Figures 5 and 6 showing a decline of the prison population rate from 220 in 2019 to 158 in 2023, = -28%; Statistics of the Lithuanian Prison service).

On 1 February 2025, a number of amendments to the Criminal Code of the Republic of Lithuania will come into force (which were due to enter into force on 1 November 2024, but were delayed). Some of them could lead to a further reduction of the prison population in Lithuania.

First of all, the provision of Para 2, Article 61 CC, according to which the court used to calculate the amount of the sentence from the average of the sentence provided by law, was abolished. This provision was clearly contrary to the ultima ratio principle (see also last chapter of this paper).

Para 4, Article 61 has been supplemented by a provision according to which, if the perpetrator has voluntarily confessed to the offence, is sincerely remorseful, has actively contributed to the detection of the offence and there are no aggravating circumstances, the court will normally sentence him or her to the minimum term of imprisonment provided for in the article sanctioning the offence, or to a penalty which does not involve imprisonment. Under the conditions set out in the first sentence of this paragraph, the court may impose a custodial sentence exceeding the minimum penalty provided for in the offence, but must give reasons for its decision. For a serious or very serious offence, the court shall, in the circumstances referred to in this paragraph, impose a sentence of deprivation of liberty not exceeding the average penalty provided for in the sanction of the Article for the offence, or a sentence which does not involve deprivation of liberty, except where the sanction of the Article provides for a sentence of life imprisonment.

According to the newly formulated Para 3, Article 54 CC, if the imposition of the penalty provided for in the sanction provided for in the Article would be manifestly contrary to the principle of justice, the court may, in accordance with the purpose of the penalty, give reasons for imposing a lighter penalty, or for postponing the execution (probation), in whole or in part, of the sentence imposed, except in the case of a very serious offence. This provision also allows for the suspension of a sentence for a serious offence, which is generally not possible according to the Para 2, Article 75 CC.

It is also important to mention that at the beginning of 2025, a single national Parole Board will be launched, consisting of 11 members, including 4 criminal law and criminology scholars, as well as representatives of the Caritas, various institutions involved in the integration of convicted prisoners, and the Lithuanian Prison Service. It is hoped that this commission will ensure a more uniform parole practice in Lithuania (previously, parole boards were established in every prison) and create conditions for a more consistent integration of former prisoners. Representatives of the municipality where the prisoner plans to live are always invited to remote meetings of the commission.

The total conviction rates per 100,000 inhabitants differ between the countries presented in the following tables (Aebi, et al., 2021). Belgium, Finland, England & Wales and Switzerland have the highest total conviction rates, in Belgium and Switzerland owing to the convictions for major traffic offences. The lowest conviction rates can be seen in Austria, the Netherlands and Estonia. Interpretation limits are given by possible differences in the diversion rates, which we could not consider in a European comparison (the European Sourcebook contains only limited information).

Interestingly, the total rate decreased in the reference period 2011–2016 in 10 of the 13 countries, specifically in Poland, Sweden (-31%), Estonia (-24%, Finland (-23%) and Austria (-20%). Belgium (+9%) and Switzerland (+4%) revealed a slight and only Spain a major increase (+31%, see Table 2).

However, looking at specific crimes, even in Spain convictions for robbery and sexual assault were not increasing. The increase there results from bodily injury and theft. Most countries showed an above average decline in the conviction rate for violent crimes, which may partly explain the decline in the prison population rates during that period.

Looking at the conviction rates in a comparative European perspective, it appears that Finland, Spain and Estonia (2016) lead the ranking for bodily injury and Belgium and Finland the one for robbery. For sexual assault, above average rates can be seen in France, England & Wales and Finland; the lowest rates are in Spain, Germany, Estonia and Sweden. Differences between the countries mostly remain marginal.

TABLE 2. Conviction rates per 100,000 of the total population according to specific crimes, 2011 and 2016 in selected European countries (Aebi, et al., 2021, 174–195)

|

Country |

Kind of offence |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

Bodily injury |

Robbery |

Sexual assault |

Theft |

Fraud |

Drug offences |

Major road traffic offences |

Total |

% change of total crimes 2011-2016 |

|

|

Austria |

2011 |

67 |

8.9 |

4.9 |

87 |

31 |

53 |

no inf. |

435 |

- 20 |

|

2016 |

49 |

7.4 |

4.4 |

72 |

26 |

46 |

no inf. |

350 |

||

|

Belgium |

2011 |

59 |

24.9 |

7.1 |

81 |

22 |

50 |

1,428 |

2,002 |

+ 9 |

|

2016 |

52 (2014) |

18.6 |

5.3 |

72 |

20 |

54 |

1,570 (2012) |

2,184* |

||

|

Czech Rep. |

2011 |

26 |

12.9 |

4.7 |

154 |

29 |

18 |

162 |

669 |

- 13 |

|

2016 |

28 |

8.6 |

5.6 |

115 |

30 |

27 |

140 |

582 |

||

|

England/ |

2011 |

55 |

16.6 |

10.6 |

249 |

27 |

110 |

8 |

2,339 |

- 9 |

|

2016 |

50 |

7.0 |

12.9 |

153 |

18 |

73 |

9 |

2,124 |

||

|

Estonia |

2011 |

121 |

20.5 |

3.5 |

222 |

27 |

37 |

254 |

769 |

- 24 |

|

2016 |

110 |

13.3 |

4.0 |

105 |

24 |

54 |

242 |

582 |

||

|

Finland |

2011 |

199 |

10.5 |

9.4 |

616 |

80 |

155 |

368 |

3,776 |

- 23 |

|

2016 |

142 |

10.3 |

10.2 |

429 |

78 |

162 |

315 |

2,899 |

||

|

France |

2011 |

88 |

7.4 (2012) |

15.2 |

140 |

13 |

77 |

368 |

930 |

- 6 |

|

2016 |

88 |

5.0 |

13.3 |

137 |

12 |

98 |

315 |

874 |

||

|

Germany |

2011 |

96 |

12.4 |

4.4 |

171 |

124 |

69 |

215 |

1,007 |

- 11 |

|

2016 |

74 |

8.4 |

3.4 |

161 |

108 |

70 |

188 |

898 |

||

|

Lithuania |

2011 |

52 |

39.7 |

10.5 |

196 |

39 |

47 |

13 |

574 |

- 2 |

|

2016 |

170 |

22.7 |

7.2 |

112 |

41 |

53 |

10 |

563 |

||

|

Netherlands |

2011 |

78 |

18.2 |

6.1 |

150 |

6 |

37 |

92 |

589 |

- 17 |

|

2016 |

62 |

12.2 |

5.1 |

146 |

4 |

35 |

69 |

489 |

||

|

Poland |

2011 |

88 |

21.1 |

3.8 |

167 |

88 |

55 |

365 |

1,113 |

- 31 |

|

2016 |

71 |

14.9 |

3.8 |

113 |

74 |

51 |

168 |

763 |

||

|

Spain |

2011 |

72 |

19.6 (2013) |

1.3 |

74 (2013) |

17 (2013) |

no inf. |

247 |

587 |

+ 34 |

|

2016 |

119 |

17.0 |

0.9 |

168 |

38 |

no inf. |

187 |

786 |

||

|

Sweden |

2011 |

100 |

10.4 |

5.0 |

274 |

19 |

239 |

303 |

1,448 |

- 31 |

|

2016 |

57 |

7.5 |

4.1 |

198 |

11 |

218 |

211 |

999 |

||

|

Switzerland |

2011 |

44 |

9.5 |

7.3 |

167 |

33 |

202 |

723 |

1,417 |

+ 4 |

|

2016 |

38 |

7.9 |

7.6 |

153 |

39 |

244 |

737 |

1,481 |

||

The largest differences are in major road traffic offences. Some countries, like Belgium, Switzerland, Finland and France, send traffic offenders to court, which will impose a fine, whereas in other countries traffic offences are sanctioned by administrative procedures with similar monetary sanctions.

These data can only be interpreted with caution (see in general Harrendorf, 2018; 2019), as one should consider more information about the diversion practice and the differentiation concerning the seriousness of the crimes within a specific kind of offence (e. g. theft, bodily injury).

Therefore, we can only find indicators that might explain different prison population rates based on different sentencing styles.

As to Lithuania, we can identify an overall stable conviction rate (-2%) in the period 2011-2016, but looking at the crime specific data, the decline of robbery, sexual assault, theft and fraud conforms to the reduced prison population rate at the same time (see Table 2 in connection with Figure 5 above).

The rate of sentenced offenders who receive an unconditional prison sentence varies considerably (see Table 3).

In total in Finland, Germany and Belgium the proportions are 2.8%, 4.8% and 6.1%, which in part may be explained by traffic offences and middle range property offences, which – if they are not diverted at the pre-trial stage – regularly receive a fine or suspended sentence.

TABLE 3. Unconditional prison sentences for different offences in 2010 and 2015 (in %) in selected European countries (Aebi, et al., 2017, 196–214; Aebi, et al., 2021, 217–234)

|

Country |

Year |

Intentional homicide (including attempts) |

Aggrava-ted bodily injury |

Sexual assault |

Robbery |

Theft (total) |

Drug offences (total) |

Major road traffic offences |

Total |

|

Austria |

2010 |

78.8 |

33.3 |

57.5 |

no inf. |

71.9 |

no inf. |

no inf. |

50.4 |

|

2015 |

100.0 |

32.9 |

55.1 |

70.6 |

45.3 |

39.5 |

no inf. |

29.1 |

|

|

Belgium |

2015* |

67.1 |

no inf. |

no inf. |

43.1 |

49.3 |

32.7 |

no inf. |

6.1 |

|

Croatia |

2010 |

59.3 |

16.3 |

51.5 |

53.4 |

21.8 |

18.8 |

10.9 |

15.6 |

|

2015 |

93.6 |

23.3 |

54.2 |

70.4 |

26.4 |

48.6 |

11.0 |

21.8 |

|

|

Czech Rep. |

2010 |

96.3 |

27.3 |

29.5 |

50.2 |

30.1 |

30.3 |

no inf. |

16.7 |

|

2015 |

97.4 |

33.5 |

21.4 |

49.5 |

29.2 |

25.0 |

6.5 |

14.5 |

|

|

Finland |

2010 |

91.8 |

51.3 |

23.6 |

48.6 |

2.5 |

7.5 |

1.6 |

3.1 |

|

2015 |

87.6 |

49.9 |

30.3 |

49.0 |

2.5 |

6.6 |

1.2 |

2.8 |

|

|

France |

2010 |

98.3 |

36.5 |

41.8 |

no inf. |

33.6 |

25.8 |

no inf. |

17.8 |

|

2015 |

98.3 |

45.8 |

38.7 |

81.1 |

38.7 |

25.7 |

10.8 |

22.1 |

|

|

Germany |

2010 |

91.9 |

10.6 |

31.6 |

35.5 |

9.7 |

11.6 |

1.0 |

5.4 |

|

2015 |

95.4 |

11.6 |

31.3 |

38.8 |

9.0 |

8.2 |

1.3 |

4.8 |

|

|

Hungary |

2010 |

91.1 |

11.4 |

59.5 |

64.9 |

18.1 |

13.7 |

10.3 |

11.6 |

|

2015 |

89.0 |

20.4 |

59.8 |

81.0 |

25.1 |

23.6 |

1.3 |

10.7 |

|

|

Lithuania |

2010 |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

52.7 |

|

2015 |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

no inf. |

28.4 |

|

|

Netherlands |

2010 |

86.4 |

33.8 |

47.6 |

74.9 |

34.8 |

43.0 |

7.0 |

23.0 |

|

2015 |

84.0 |

42.3 |

65.8 |

67.8 |

44.7 |

39.4 |

11.1 |

28.5 |

|

|

Poland |

2010 |

96.2 |

32.8 |

51.1 |

50.8 |

15.7 |

11.3 |

2.0 |

9.2 |

|

2015 |

96.3 |

36.7 |

44.8 |

51.7 |

21.7 |

11.1 |

8.3 |

13.1 |

|

|

Sweden |

2010 |

98.8 |

70.6 |

74.7 |

54.1 |

7.5 |

8.9 |

12.2 |

9.6 |

|

2015 |

80.8 |

71.8 |

65.7 |

59.0 |

9.6 |

6.4 |

12.7 |

10.2 |

|

|

UK: E/W |

2010 |

67.8 |

30.2** |

56.9 |

58.1 |

18.4 |

15.8 |

33.6 |

7.5 |

|

2015 |

67.4 |

88.0** |

76.5 |

68.2 |

31.2 |

18.6 |

43.0 |

7.2 |

|

|

UK: SCO |

2010 |

99.3 |

51.2 |

48.1 |

51.7 |

30.6 |

18.7 |

6.3 |

20.7 |

|

2015 |

no inf. |

54.4 |

59.0 |

78.4 |

31.9 |

14.1 |

11.7 |

19.0 |

On the other hand, the Netherlands with a very low total conviction rate, because of a diversion rate of 49% (Aebi et al., 2021, 130) shows a higher rate of unconditional prison sentences (28.5%), as the cases brought to court are presumably more serious ones than in other countries. The same is probably the case in Austria.

It is remarkable, that Germany with a diversion rate of 52% has one of the lowest rates of unconditional prison sentences in most of the crimes listed in the following table.

Belgium on the other hand has one of the highest proportions of unconditional sentences for the crimes for which information was available.

There are few differences in sentencing homicide, but for aggravated bodily injury the range in 2016 was from 11.6% (Germany) to 55.4% (Scotland) and no less than 71.8% in Sweden.

Similar differences appear for sexual assault: 30.3% and 31.3% unconditional imprisonment in Finland and Germany versus 65.8% in the Netherlands and even 76.5% in England & Wales.

For robbery, the range is from 38.8% in Germany to 78.4% (Scotland) and 81% in Hungary and France (see Table 3).

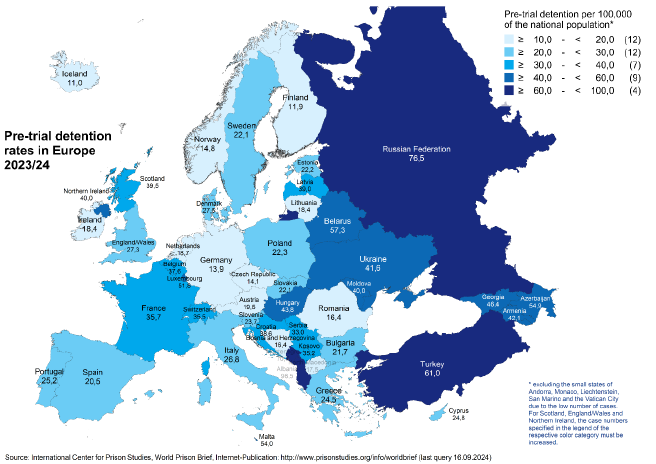

Prison population rates, at least in some countries (see Morgenstern, 2018) are much influenced by the number of pre-trial detainees. Pre-trial detention in Germany has decreased by 47% since 1994 the proportion of pre-trial detainees was 21% (2023). Germany (apart from Austria (20%) had the lowest pre-trial detention rate in Western Europe, strongly contrasting e. g. Belgium (36%) Denmark (39%), Northern Ireland (41%), Switzerland (46%) or Luxembourg (49%), whereas in many Eastern European countries the percentage in 2023/24 was below 15% (e.g. Czech Republic, 8%; Poland 11%; Lithuania 12%; or Romania and Slovakia 13%, see http://www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief, last query: 16 September 2024).

Figure 13 relates not to the proportion of pre-trial detainees of the total prison population, but to the rate per 100,000 inhabitants. Finland (11.9) together with Germany (13.9), the Czech Republic (14.1) and Norway (14.8) have the lowest pre-trial detention rates per 100,000 inhabitants in contrast to Turkey (61.0), Russia (76.5), and Albania (98.5). The variation within Europe is similar to the ones for the total prison population rates (see Figure 3 above), but the regional distribution is different, as many high level-prison population countries in Eastern Europe have only moderate pre-trial detention rates (see above the percentages scale).

FIGURE 13. Pre-trial detention rates in Europe 2023/24 (World Prison Brief)

The proportion of foreigners among the group of sentenced prisoners was 34% in 2022. The proportion of foreigners is higher in pre-trial detention, up to 40–50% in some regions and prisons (Morgenstern, 2018; Dünkel, Harrendorf, Geng, 2024). Additionally, there is an unknown proportion of prisoners with a German passport, but with a migration background.

The median of sentences to be served of the stock population in prisons for adults in October 2022 was about two and a half years; only 23.9% had to serve more than 5 years. The data in Table 4 indicate longer sentences than the ones in Table 1 presented above, as Table 4 covers all sentences imposed on individual offenders, including revoked suspended sentences etc. Nevertheless, this database indicates that the length of total prison terms on average is no more than 3 years.

TABLE 4. Total length of prison sentences to be served in German prisons for adults, 31 October 2022

|

<3 m. |

3-<6 m. |

6 m.-1 year |

>1-2 years |

>2-3 years |

>3-4 years |

>4-5 years |

>5-10 years |

>10-15 years |

> 15 years* |

Life imprisonment |

Total |

|

|

Abso-lute |

1,993 |

2,514 |

4,697 |

6,746 |

6,632 |

5,143 |

3,225 |

6,479 |

1,299 |

200 |

1,757 |

40,685 |

|

Percentages |

4.9 |

6.2 |

11.5 |

16.6 |

16.3 |

12.6 |

7.9 |

15.9 |

3.2 |

0.5 |

4.3 |

100 |

* According to § 38 of the German Criminal Code, the maximum determinate sentence is 15 years. In a few cases it can happen that recidivist offenders are convicted for several crimes summing up to more than 15 years.

One big problem of the German prison system is the large group of prisoners who were sentenced to a fine and who were not able or not willing to pay it (fine defaulters). They constituted a considerable minority of 12.8% of the adult prison population on 31 October 2023(in youth justice fine default imprisonment does not exist). Table 5 shows that in 2020 the prison administrations of all Federal States decided not to execute fine default imprisonment in order to prevent infections through the high numbers of entries and releases of these short-term prisoners. Temporarily the proportion of fine default prisoners dropped to 3.5%, but after the pandemic it rose again to an unexpected new maximum, higher than before the pandemic18. The reform law of 7 July 2023 has reduced the convergence rate of fine default imprisonment from one day fine per one day of imprisonment to two day fines per one day of imprisonment. This reform applies to fines imposed after 1 March 2024, i. e. a further decline of the prison population may be expected, as fine defaulters have to serve only half the amount of days compared to the time before the law reform (see section below for a crime policy to prevent or at least reduce fine default imprisonment).

TABLE 5. Sentenced adult prisoners serving fine default imprisonment in the German adult prison system, 2004–2022 (and the impact of non-execution during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020–2021)

|

Date |

Sentenced prisoners in adult prisons |

Of them: Serving fine default imprisonment |

Percentages |

|

08/31/2004 |

54,015 |

3,625 |

6.7 |

|

08/31/2010 |

51,015 |

3,880 |

7.6 |

|

08/31/2013 |

45,923 |

3,964 |

8.6 |

|

08/31/2018 |

42,873 |

4,753 |

11.1 |

|

02/02/2020 |

45,062 |

4,773 |

10.6 |

|

06/30/2020 |

38,644 |

1,335 |

3.5 |

|

06/30/2021 |

40,783 |

2,891 |

7.1 |

|

11/30/2021 |

41,152 |

4,652 |

11.3 |

|

06/30/2022 |

40,199 |

4,411 |

11.0 |

|

10/31/2022 |

40,737 |

5,224 |

12.8 |

|

06/30/2023 |

40,833 |

4,863 |

11.9 |

|

10/31/2023 |

41,177 |

5,258 |

12.8 |

|

06/30/2024 |

40,180 |

4,143 |

10,3 |

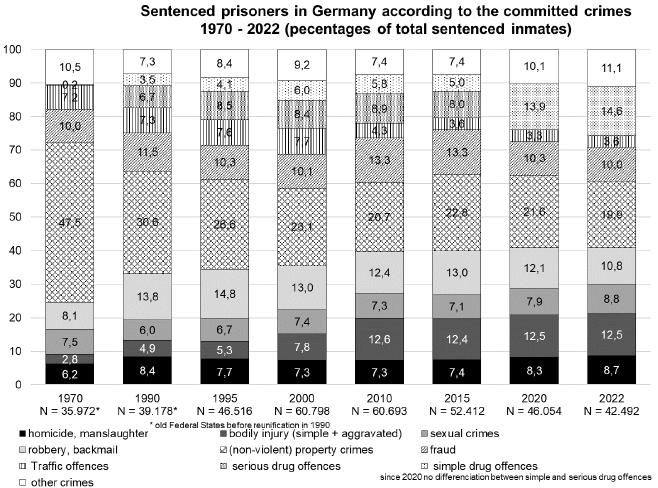

Another challenge for prison administrations in Germany is the inmate structure according to the crimes underlying imprisonment. The structure has changed since the 1970s with an increase of violent offenders and a decrease of non-violent property offenders (see Figure 14). The proportion of sentenced prisoners convicted for violent crimes in 2022 was 40.8%. It has been stable since 2010, but it has increased considerably since 1970 (24.6%).

This structure causes many problems of treatment (preferably in so-called social-therapeutic departments), security and of how to prepare these prisoners for release and provide sufficient aftercare (see Dünkel, Harrendorf, Geng, 2024).

FIGURE 14. Sentenced prisoners in Germany according to crimes committed 1970–2022 (percentages of total sentenced inmates)

As has already been said under section 1, the decline of the prison population in Germany is also remarkable from a European comparative perspective.

With periodical increases and decreases, Germany has had a stable, and since 2003, a declining prison population rate (-32%). The increases may be explained by the crime rates during the 1970s and after the reunification of Germany (1990) some societal anomia (in the former East-Germany).

The decreases may be explained by legal and practical reforms (1969/1974) and in the 1980s by the declared aim to reduce the prison population. Judicial practice has widened the application of diversion.

The decrease in the 2000s is not based on a declared penal policy but is mainly the result of declining (violent) crime rates and changes in sentencing practices (widening diversion, reducing pre-trial detention, expanding the use of suspended sentences etc.).

Apart from these explanations, political and socio-economic factors (according to Lappi-Seppälä’s model, see above Fn. 2 in the Introduction) fit Germany very well; it now has a low prison population rate, similar to the ‘exceptionalist’ Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands and Slovenia (Dünkel, 2013; Lappi-Seppälä, 2020).

The Government elected in 2021 (Social Democratic, Green and Liberal Party) agreed in the coalition contract to a major reform of the law governing penal sanctions. Apart from the liberalisation (decriminalisation) of cannabis (which was passed in spring 2024) the reform law of 7 July 2023 introduced some important regulations with the aim of reducing fine default imprisonment (see for a comment to the draft legislation Dünkel, 2022). The conversion rate between one day of fine default imprisonment to one day-fine was changed from 1:1 to 1:2, which led to the number of these prisoners being halved (according to the Federal Bureau of Statistics the reform law shows first effects only by mid-2024 as the new conversion rate came into effect for fines imposed after 1 March 2024).

In addition, the use of the substitute sentence of community service and other alternatives will be expanded by involving the probation services before a court decision on fine default imprisonment.

Furthermore, the court may combine a suspended sentence (probation) with a requirement (obligation) to undergo therapy. The legislator trusts that such therapies are successful, and in many cases do not require imprisonment.

On the other hand – as in the past – amendments to the general sentencing provision (§ 46 penal law) may contribute to harsher punishments, by considering hate crime or gender-oriented motives as aggravating circumstances in sentencing.

The reform law is a typical product of a bifurcation strategy by providing more severe punishments for violent and sexual offenders on the one hand and a moderation approach for the others.

However, the guiding principle of resocialisation has been kept and even reinforced, also for the most serious and ‘dangerous’ offenders, in particular those sent to preventive detention after having served the full determinate sentence (§ 66–66c Penal Law).

Currently, further pressure to reduce the prison population comes from the prison administration reflecting the situation on the labour market. Many prison officers and also psychologists or psychiatrists have left the Prison Service, a large proportion is registered sick, and finding new staff is very difficult, due to the general shortage of skilled personnel in the labour market. Therefore, prison administrations think about possibilities to reduce the prison population, i. a. by expanding open prisons or closing down facilities that are not fully used (see the occupancy rate of 77% in Germany mentioned above). The daily costs for one prison place in Germany are about 230 € (!), e. g. 50 € in Lithuania.

National strategies to limit overcrowding in prisons should be oriented to the specific problems of the sentencing practice and the resulting inmate structure.

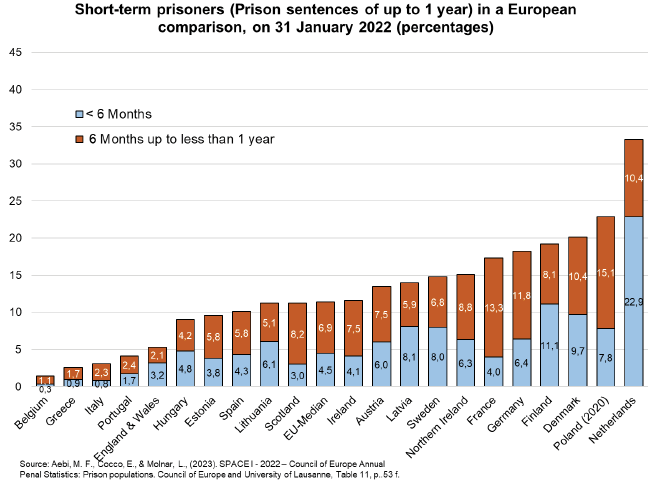

If short-term imprisonment plays an important role (see Figure 15), alternative sanctions or forms of executing such sentences may be a promising strategy (Dünkel et al., 2019a, 499; Dünkel, Snacken, 2022, 670). The German reform efforts by the law of 2023 to avoid fine default imprisonment may be seen as a step in the right direction. To illustrate, in Lithuania until 2019, evasion of a fine resulted in its conversion into an arrest (up to 90 days, with one day of arrest equating to a fine of 100 €)19. Despite the absence of statistical data regarding the number of cases, this option was terminated in 2019, and currently, only a limitation of liberty (house arrest) can be imposed for evading a fine. It is noteworthy that this reform has not been subjected to extensive criticism by the authorities responsible for the administration of criminal justice. Thus far, there have been no indications that it has resulted in the emergence of new challenges, such as an increase in the number of instances of evasion of payment of fines.

Belgium was quite effective in the past in avoiding short-term imprisonment, but the present high pre-trial detention rate and severe sentences for some property and violent crimes are a major challenge. The actual policy to reverse the strategy not to execute prison sentences of up to three years, may aggravate the problems of overcrowding. On the other hand, the use of electronic monitoring for short-term offenders as a ‘stand-alone’ measure is questionable as the needs of offenders for personal (social work) support are not met that way (Dünkel, 2018). In 2019, the Lithuanian Criminal Code introduced a provision enabling the suspension of the execution of an arrest sentence through the implementation of electronic monitoring20. Nevertheless, as evidenced by the sentencing statistics, this has not resulted in a reduction in the proportion of actual imprisonment, but has led to a reduction in the proportion of alternative sentences.

FIGURE 15. Short-term prisoners in a European comparison, on 31 January 2022 (Aebi, Cocco, Molnar 2023, 53)

An additional illustrative good example is the recent abolition of the rule of sentencing on the basis of the average sentence by the Lithuanian Criminal Code at the beginning of 2025. This rule had been in force for over two decades and was deemed incompatible with the principle of the ultima ratio, resulting in longer prison sentences. It is interesting to see that the German Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof) in several decisions since 1976 emphasised that the punishment in mid-range cases (‘average’ seriousness) have to be chosen from in the lower part of the (statutory) range of punishments, resulting in a sentencing practice oriented to the minimum range of punishments21, whereas in many Eastern European countries it used to be around the median point. The same sentencing rules as in Germany apply also in Finland and Scandinavia (see Vinkannen & Lappi-Seppälä, 2011).

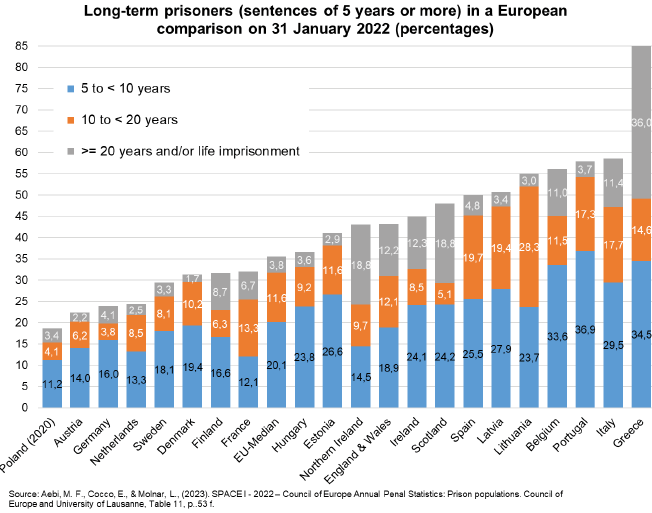

If long-term imprisonment is the major problem (see Figure 16), a solution could be expanding early release and considering it at an earlier stage, e. g. after half the sentence has been served in prison, in combination with structured transition management (Dünkel et al., 2019a, 499; Dünkel, Snacken, 2022, 670–680). To illustrate, in Lithuania, the possibility of automatic parole after serving three-quarters of the sentence for certain crimes was scheduled for implementation in 2020, contingent upon the use of electronic monitoring. This has resulted in a 25% increase in the number of individuals under parole supervision (see Sakalauskas, 2024, 81).

There is evidence that in many countries the length of prison terms has increased, in particular for violent and sexual offences as well as for terrorism. In Lithuania, despite the considerable decline in the incidence of serious criminal offences, the prosecution of domestic violence has been intensified since 2011 (no longer necessitating a complaint from the victim), and in 2017 driving under the influence of alcohol (over 1.5 per mil) became a criminal offence. In the same year, the possession of small amounts of narcotic drugs became a criminal offence, whereas previously it could also be an administrative offence. These three decisions have resulted in an estimated 15,000 additional individuals being suspected or accused of criminal activity annually. While the majority of these individuals are initially granted release from criminal liability or non-custodial sentences, courts have increasingly resorted to incarceration when such behaviour is repeated. The evidence indicates that this approach has not been effective in addressing the issues of domestic violence, drunk-driving, and drug use, despite the fact that some of these individuals are subject to criminal liability.

FIGURE 16. Long-term prisoners in a European comparison on 31 January 2022 (Aebi, Cocco, Molnar 2023, 53)

It will be difficult to reverse this development, but perhaps reducing the numbers of offenders who should not be in prison (fine defaulters, offenders with repetitive small property or drug crimes, failing to pay for public transport etc.) and concentrating on longer-term prisoners with rehabilitation programmes, including structured transition and aftercare, could be a promising strategy (Dünkel, Snacken, 2022).

Literature

Aebi, M. F., et al. (2017). European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics 2014. 5th ed., 2nd revised printing, Helsinki: European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI).

Aebi, M. F., et al. (2021). European Sourcebook of Crime and Criminal Justice Statistics 2021. 6th ed., Göttingen: Göttingen University Press.

Aebi, M. F., Linde, A., Delgrande, N. (2015). Is There a Relationship Between Imprisonment and Crime in Western Europe? European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 21, 425–446.

Aebi, M. F., Cocco, E., Molnar, L. (2024). SPACE I – 2022 – Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics: Prison populations. Strasburg, Lausanne: Council of Europe and University of Lausanne.

Brandariz, J. A. (2021). Beyond the austerity-driven hypothesis: Political economic theses on penality and the recent prison population decline. European Journal of Criminology 18, 349–367.

CPT (2023). Report to the Lithuanian Government on the periodic visit to Lithuania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 10 to 20 December 2021. CPT/Inf (2023) 01. Strasbourg, 23 February 2023.

CPT (2024). Report to the Lithuanian Government on the visit to Lithuania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 12 to 22 February 2024. CPT/Inf (2024) 25. Strasbourg, 18 July 2024.

Čepas, A., Sakalauskas, G. (2010). Lithuania. In Newman, R. G. (gen. ed.), Aebi, M. F., Jaquier, V. (vol. ed.), Crime and punishment around the world. Europe. Volume 4. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2010, 197–207.

Dünkel, F. (2013). Slovenian Exceptionalism? – Die Entwicklung von Gefangenenraten im internationalen Vergleich. In Ambrož, U. M., Filipčič, K., Završnik, A. (Eds.), Essays in Honour of Alenka Šelih. Criminal Law, Criminology, Human Rights. Ljubljana: Institute of Criminology at the Law Faculty, University of Ljubljana, 61–93.

Dünkel, F. (2017). European penology: The rise and fall of prison population rates in Europe in times of migrant crises and terrorism. European Journal of Criminology 14, 629–653.

Dünkel, F. (2017). Electronic monitoring – Some critical issues. In Bijleveld, C., van der Laan, P. (Eds.), Liber Amicorum Gerben Bruinsma. Den Haag: Nederlands Studiecentrum Criminaliteit en Rechtshandhaving (NSCR), 108–117.

Dünkel, F. (2018). Electronic Monitoring in Europe – a Panacea for Reforming Criminal Sanctions Systems? A Critical Review. Kriminologijos studijos 6, 58–77. https://doi.org/10.15388/CrimLithuan.2018.6.3.

Dünkel, F. (2019). Reforms of the Criminal Sanctions System in Germany – Achievements and Unresolved Problems. Juridica International (Estonia) 28, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.12697/JI.2019.28.05).

Dünkel, F. (2022). Abschaffung oder Reform der Ersatzfreiheitsstrafe? Schleswig-Holsteinischer Verband für Soziale Strafrechtspflege: Zeitschrift für Soziale Strafrechtspflege 22, 5–20.

Dünkel, F., et al. (2019a). Comparable aims and different approaches. Prisoner Resettlement in Europe – concluding remarks. In Dünkel et al. (Eds.), Prisoner Resettlement in Europe. London, New York: Routledge, 481–519.

Dünkel, F., Geng, B., Harrendorf, S. (2021). Gefangenenraten im internationalen und nationalen Vergleich – Entwicklungen und Erklärungsansätze. In Schäfer, L., Kupka, K. (Eds.), Freiheit wagen – Alternativen zur Haft. Freiburg i. Br.: Lambertus Verlag, 18–52.

Dünkel, F., Harrendorf, S., van Zyl Smit, D. (Eds.) (2022). The Impact of COVID-19 on Prison Conditions and Penal Policy. London, New York: Routledge.

Dünkel, F., Harrendorf, S., Geng, B. (2024). Strafvollzug. In Hermann, D., Pöge, A. (Eds.), Kriminalsoziologie. Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Praxis. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlag, 529–575.

Dünkel, F., Snacken, S. (2022). What could we learn from COVID-19? A reductionist and penal moderation approach. In Dünkel, F., Harrendorf, S., van Zyl Smit, D. (Eds.), The Impact of COVID-19 on Prison Conditions and Penal Policy. London, New York: Routledge, 665–691.

Harrendorf, S. (2017). Sentencing Thresholds in German Criminal Law and Practice: Legal and Empirical Aspects. Criminal Law Forum 28, 501–539.

Harrendorf, S. (2018). Prospects, Problems, and Pitfalls in Comparative Analyses of Criminal Justice Data. Crime and Justice: A Review of Research 47, 159–207.

Harrendorf, S. (2019). Criminal Justice in International Comparison – Principal Approaches and Endeavors. In Dessecker, A., Harrendorf, S., Höffler, K. (Eds.), Angewandte Kriminologie – Justizbezogene Forschung. 12. Kriminalwissenschaftliches Kolloquium und Symposium zu Ehren von Jörg-Martin Jehle, 22./23. Juni 2018. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen, 323–347.

Heinz, W. (2017). Kriminalität und Kriminalitätskontrolle in Deutschland – Berichtsstand 2015 im Überblick. Stand: Berichtsjahr 2015; Version: 1/2017. Konstanzer Inventar Sanktionsforschung. http://www.ki.uni-konstanz.de/kis/.

Heinz, W. (2019). Sekundäranalyse empirischer Untersuchungen zu jugendkriminalrechtlichen Maßnahmen, deren Anwendungspraxis, Ausgestaltung und Erfolg. Konstanz: Universität Konstanz. https://www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/ Service/Fachpublikationen/Sekundaeranalyse_jugendkriminalrechtliche-Ma%C3%9Fnahmen.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4).

Heinz, W. (2023). Bewährungshilfe im Spiegel der Statistik. Forum Strafvollzug 72, 303–310.

Heinz, W. (2023). „Blindflug“?! Normsetzung und Normanwendung in der Jugendkriminalrechtspflege im Lichte der empirischen Sanktions- und Wirkungsforschung. Konstanz: Konstanzer Inventar zur Sanktionsforschung (KIS). https://www.jura.uni-konstanz.de/ki/sanktionsforschung-kis/.

Hinkkanen, V., Lappi-Seppälä, T. (2011). Sentencing Theory, Policy, and Research in the Nordic Countries. Crime and Justice 40(1), (Crime and Justice in Scandinavia), 349–404.

Lappi-Seppälä, T. (2007). Penal Policy in Scandinavia. In Tonry, M. (Ed.), Crime, Punishment, and Politics in Comparative Perspective. Crime and Justice 36. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 217–295.

Lappi-Seppälä, T. (2010). Vertrauen, Wohlfahrt und politikwissenschaftliche Aspekte – Vergleichende Perspektiven zur Punitivität. In Dünkel, F., et al. (Eds.), Kriminalität, Kriminalpolitik, strafrechtliche Sanktionspraxis und Gefangenenraten im europäischen Vergleich. Mönchengladbach: Forum Verlag Godesberg, 937–996.

Lappi-Seppälä, T. (2011). Explaining Imprisonment in Europe. European Journal of Criminology 8, 303–328.

Lappi-Seppälä, T. (2020). Regulating Prison Populations – Exploring Nordic Experiences with Frieder Dünkel and his Comparative Project. In Drenkhahn, K., et al. (Eds.), Kriminologie und Kriminalpolitik im Dienste der Menschenwürde. Festschrift für Frieder Dünkel zum 70. Geburtstag. Mönchengladbach: Forum Verlag Godesberg, 161–184.

Morgenstern, C. (2018). Die Untersuchungshaft. Eine Untersuchung unter rechtsdogmatischen, kriminologischen, rechtsvergleichenden und europarechtlichen Aspekten. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlag.

Sakalauskas, G. (2014). Lithuania. In Drenkhahn, K., Dudeck, M., Dünkel, F. (Eds.), Long-Term Imprisonment and Human Rights (Routledge Frontiers of Criminal Justice). Routledge, 198–217.

Sakalauskas, G. (2019a). Criminal policy and imprisonment. The case of Lithuania: open prisons, prison leave and release on parole. In Van Kempen, P. H., Jendly, M. (Eds.), Overuse in the Criminal Justice System. Cambridge, Antwerp, Chicago: Intersentia, 229–249.

Sakalauskas, G. (2019b). Prisoner resettlement in Lithuania – Between Soviet tradition and challenges of modern society. In Dünkel, F., Pruin, I., Storgaard, A., Weber, J. (Eds.), Prisoner Resettlement in Europe. London, New York: Routledge, 219–239.

Sakalauskas, G. (2021). Non-custodial sanctions and measures in Lithuania: a large bouquet with a questionable purpose and unclear effectiveness. In: Instituto Jurídico Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra (Ed.), Promoting non-discriminatory alternatives to imprisonment across Europe. Non-custodial sanctions and measures in the member states of the European Union. Coimbra: Instituto Jurídico Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra, Colégio da Trindade. https://www.uc.pt/site/assets/files/2181008/lithuania.pdf.

Sakalauskas, G. (2024a). Bausmių vykdymo politikos įgyvendinimo ir nuteistųjų teisių užtikrinimo problemos. In Leonaitė, E. (red.), 2023 m. žmogaus teisių padėties Lietuvoje stebėsenos ataskaita. Vilnius: Lietuvos Respublikos Seimo kontrolierių įstaiga, 141–154. https://www.lrski.lt/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ZmogausTeises_2024_web-new.pdf

Sakalauskas, G. (2024b). Nuteistųjų resocializacijos problematika. In Žmogaus teisės Lietuvoje 2002–2023 m. Žmogaus teisių stebėjimo institutas, 79–83. https://hrmi.lt/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2022-2023-Zmogaus-teises-Lietuvoje-apzvalga.pdf

Sakalauskas, G. (2025). Lithuania. In Dünkel, F., Lehmkuhl, M., Păroşanu, A., Pruin, I. (Eds.), Restorative Justice in Penal Matters in Europe. The Hague: Brill (in print).

Snacken, S. (2012). Conclusion: Why and How to Resist Punitiveness in Europe? In: Snacken, S., Dumortier, E. (Eds.), Resisting Punitiveness in Europe? Welfare, human rights and democracy. London: Routledge, 247–260.

Snacken, S., Dumortier, E. (Eds.) (2012). Resisting Punitiveness in Europe? Welfare, human rights and democracy. London: Routledge.

Spieß, G. (2020). Sanktionspraxis in Deutschland – Entwicklung und Struktur, Bewährung und Probleme. In Drenkhahn, K. et al. (Eds.), Kriminologie und Kriminalpolitik im Dienste der Menschenwürde. Festschrift für Frieder Dünkel zum 70. Geburtstag. Mönchengladbach: Forum Verlag Godesberg, 485–506.

Travis, J., Western, B., Redburn, S. (Eds.) (2015). The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, D. C.: The National Academies Press.

1 Available at https://www.prisonstudies.org/world-prison-brief-data.

2 Theories for the explanation of the rise and fall of prison population rates in Europe have extensively been described by Dünkel 2017, referring to the model of Lappi-Seppälä 2007; 2010; 2011 (see also Lappi-Seppälä 2020). According to Lappi-Seppälä long-term developments of prison population rates can be explained by political science indicators such as the neo-liberal model (with high level prison population rates) vs. conservative corporatist systems (moderate rates) vs the social democratic welfare approach (solidarity with minorities etc., associated with low-level prison population rates). Socio-economic factors (e. g. a high Gini-index characterising societies with a large discrepancy between rich and poor social classes are associated with high prison populations. Welfare, legitimacy of and trust in judicial institutions and confidence in the political system are of importance in this respect as well. In addition, the political culture based on either consensus or conflict orientation seems to determine crime policy. In a democratic system with coalition-based governments, policy will never sharply shift from one to the other extreme as it could be the case in jurisdictions such as in England. Germany as well as the Scandinavian countries have always been governed by coalitions, which resulted in a rather stable and moderated crime policy. The Scandinavian “exceptionalism” with uniform low level prison population rates may be explained by these factors. These basic findings of the last 20 years penological debates are confronted with new developments in Eastern European countries with strongly declining prison population rates, which primarily can be explained by shifts in crime policy in the context of changes in crime rates and sentencing practices. These changes are in the focus on the present chapter.

3 See for the development of German crime policy and its impact on prison population rates Heinz, 2017; 2023; Dünkel, 2019; Spieß, 2020.

4 See for the development of the Lithuanian crime policy and its impact on prison population rates Sakalauskas, 2014; 2019a; 2019b; 2021; 2025.