Kriminologijos studijos ISSN 2351-6097 eISSN 2538-8754

2024, vol. 12, pp. 93–134 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/CrimLithuan.2024.12.4

Rasita Adomaitytė

Vilniaus universitetas, Filosofijos fakultetas

Sociologijos ir socialinio darbo institutas

Kriminologijos katedra

Vilnius University, Faculty of Philosophy

Institute of Sociology and Social Work

Department of Criminology

Universiteto g. 9, LT-01513 Vilnius

Tel. (8 5) 266 7600

El. paštas: rasita.adomaityte@gmail.com

Summary. Crimes against a person’s freedom of sexual self-determination are complex and sensitive, violating fundamental rights and causing significant psychological harm. Public attitudes towards these crimes are often shaped by misconceptions and stereotypes, such as the “ideal victim” and “presumed perpetrator,” which bias perceptions. Nils Christie’s concept of the “ideal victim” highlights society’s preference for victims seen as innocent and vulnerable, fostering empathy only for those who fit this mold. Similarly, the “presumed perpetrator” stereotype frames offenders as deviant and powerful, attribution. When individuals deviate from these stereotypes, victim-blaming and bias can arise, simplifying attribution of blame. The analysis focuses on how the characteristics of victims and perpetrators influence the attribution of guilt within the context of Lithuanian society. The content analysis of mass media and criminal convictions explores how societal perceptions are shaped and how emphasising certain traits reflects ideologies surrounding “real rape” and the “ideal victim.” Additionally, qualitative semi-structured interviews examine the influence of these ideas on the attribution of guilt.

Key words: Stereotypes, Sexual violence, Social imaginaries, Media framing, Narratives

Santrauka. Asmens seksualinio apsisprendimo laisvę pažeidžiantys nusikaltimai yra itin jautri ir kompleksiška tema. Šie nusikaltimai visuomenėje vertinami kaip vieni sunkiausių ir kartu tai veikos, kurias lydi bene daugiausia stereotipais paremtų įsitikinimų. Nors neigiamos stereotipų sąsajos su seksualinio pobūdžio nusikaltimų vertinimu jau seniai yra analizuojamos užsienio mokslinėje literatūroje, visgi šių idėjų reikšmingumas Lietuvos kontekste yra mažai tiriamas. Šiame darbe pasitelkiami trys tarpusavyje glaudžiai susiję konceptai – socialinės vaizduotės, idealios aukos ir tikrojo išžaginimo. Tyrime nagrinėjama, kaip aukų ir kaltininkų savybės daro įtaką kaltės priskyrimui Lietuvos visuomenės kontekste. Žiniasklaidos priemonių ir baudžiamųjų nuosprendžių turinio analizė atskleidžia, kaip formuojasi visuomenės suvokimas ir kaip tam tikrų bruožų išryškinimas atspindi ideologijas, susijusias su „tikruoju išžaginimu“ ir „idealia auka“. Pusiau struktūruotų kokybinių interviu analizė padeda atskleisti, kaip šios idėjos veikia kaltės priskyrimo mechanizmus.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: stereotipai, seksualinis smurtas, socialinė vaizduotė, žiniasklaidos įrėminimas, naratyvai

_________

Received: 19/06/2024. Accepted: 19/09/2024

Copyright © 2024 Rasita Adomaitytė. Published by Vilnius University Press

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Stereotypes are an integral part of daily life. They simplify cognitive processes by enabling the grouping of traits, which helps individuals quickly identify objects – like tables or chairs – without excessive mental deliberation. According to the Cambridge Dictionary (2024), a stereotype is “a set idea that people have about what someone or something is like, especially an idea that is wrong”. At first glance, stereotypes may seem harmless or even practical. However, their detrimental nature emerges when applied to people. This happens when populations are no longer viewed as collections of unique individuals but are broadly characterised by certain traits or their absence. Such thinking erodes personal identity, negatively impacts self-perception, and influences societal judgment (Fraser, Nejadgholi, and Kiritchenko 2021). The stakes become significantly higher when stereotypes infiltrate the realm of criminal justice. Justice, while a profoundly human endeavour, must remain untainted by personal biases and preconceived notions. This article seeks to explore the issue of stereotyping through the lens of crimes against individuals’ sexual self-determination. By focusing on the concepts of the “ideal victim” and “stereotypical perpetrator” alongside the framework of the social imaginary, the research examines societal beliefs surrounding sexual crimes. These beliefs are contextualised through an analysis of legal rulings in criminal cases to investigate how stereotypes might influence the attribution of guilt in such contexts. The article provides an in-depth analysis of how societal stereotypes influence the perception of sexual violence and the attribution of guilt in cases involving adult victims. By narrowing the scope to adult victims, the research avoids conflating the unique stereotypes and societal attitudes associated with crimes against minors, such as predatory grooming, which is a key concept in child abuse cases, where perpetrators manipulate and prepare victims over time. While manipulation happens in adult cases, too, it is not always through the structured grooming process seen in child exploitation. Secondly, children are inherently seen as non-sexual beings, which makes their victimhood absolute, and that is not the case with adult victims. Crimes against children also often involve offenders with a specific sexual interest in minors. In adult cases, perpetrators might act out of situational factors, entitlement, or power rather than a specific paraphilia. (Socia and Rydberg 2019). The central thesis argues that mass media narratives about sexual crimes significantly shape individual perceptions and influence blame attribution.

While international scholarship has thoroughly explored the relationship between sexual violence and stereotypes, this topic has received considerably less attention in Lithuania. Two foundational studies include L. Skučas’s 1999 article “Young People and Rape Myths” in Violence against Women in Lithuania and the 2003 study by D. Bandzevičienė and R. Erentaitė, “Tendencies of Stigmatization of Sexual Violence Victims.” Skučas focused on youth attitudes toward rape and the prevalence of myths in society, primarily to emphasise the need for public awareness campaigns (Skučas’s 1999). Bandzevičienė and Erentaitė examined the views of older, working-age individuals and how stereotypes influence their assessments of sexual violence (Bandzevičienė and Erentaitė 2003). While both sources offer valuable insights into public perceptions in Lithuania, they are now dated and primarily document the existence of stereotypical thinking without deeper analysis. Therefore, a broader exploration of how such stereotypes influence the interpretation of situations and the attribution of guilt – especially through the lens of the social imaginary and legal case analysis – seeks to address a topic that remains underexamined in Lithuanian academic literature.

Crimes targeting the freedom of sexual self-determination remain a sensitive topic in society. These actions are widely condemned, reflecting a collective recognition of their profound violation of fundamental human rights and the irreparable psychological harm inflicted on victims. However, even though these crimes are condemned because of their severity, they are also deeply intertwined with societal stigmas and misconceptions. Perceptions of such offences are frequently shaped by public narratives and stereotypes rather than personal experiences, leading to potentially distorted views.

This distorted perception stems from social imaginaries – a concept explored by Charles Taylor in “Modern Social Imaginaries”. Taylor defines social imaginaries as the shared values, beliefs, and symbols shaping collective identity and social practices. It influences how individuals interpret their experiences and interact within society. These shared perceptions, often linked with stereotypes, form simplified frameworks for understanding complex realities (Taylor 2004). They are used in everyday life but are particularly significant in the context of crimes of a sexual nature. Sexual crimes do not follow a clear blueprint, making them complex and difficult to comprehend fully. Unlike other experiences, sexual crimes are not universally encountered, adding an element of mystery that exacerbates misconceptions. This lack of personal experience among the general population leads to a reliance on social imaginaries to interpret these crimes. As a result, the simplified and often inaccurate representations perpetuated by social imaginaries can profoundly influence societal perceptions and reactions to sexual crimes.

Stereotypical constructs shape and actively constrain the boundaries of societal imaginaries, influencing how people perceive and interpret reality. In the context of sexual violence, these rigid narratives dictate a narrow and often misleading framework of what such crimes “should” look like. The repeated portrayal of sexual violence in specific, often sensationalised ways – such as the stranger-in-a-dark-alley trope – creates an illusion that this is the only valid or “real” form of such crime.

As a result, when cases do not align with this dominant script – when the perpetrator is a trusted individual, when there is no physical resistance, or when the victim does not conform to preconceived notions of innocence – society is less likely to recognise or believe that sexual violence has occurred. The more these stereotypes dominate societal imaginaries, the more difficult it becomes for victims whose experiences fall outside these constructs to be heard, believed, and supported. In this way, stereotypes do not just shape perception – they actively uphold structures of disbelief and silence, preventing justice and understanding (Yap 2017). These two elements form a self-reinforcing cycle: the social imaginary shapes and sustains stereotypes by simplifying reality and generalising groups. In turn, these stereotypes shape how society perceives and interprets the world, making them seem natural rather than constructed. This repetition normalises biases, leading individuals to unconsciously adopt and apply them, further embedding stereotypes into cultural and social structures. As a result, society continuously reproduces and reinforces these limiting narratives, making them harder to challenge or change.

This cycle not only shapes perceptions of crime but also defines societal understandings of victims and perpetrators, influencing who is seen as credible or deserving of sympathy. Nils Christie’s concept of the “ideal victim” explains how society constructs a narrow image of victimhood based on specific traits, reinforcing biases in how victims are perceived and treated. According to the author, “The ideal victim is a person or group who, when they experience crime, ‘most readily are given the complete and legitimate status of being a victim” (Christie, 1986). Central to Christie’s analysis is an examination of the specific traits that define the ideal victim, including qualities such as innocence, vulnerability, and moral rightness.

Since the concept of the ideal victim aligns with socially accepted stereotypes of victimhood, society is more inclined to recognise and empathise with those who fit this mould. This stereotypical perception of the victim creates a template against which those who have been harmed are judged, and society more readily recognises and sympathises with those who are closely associated with these characteristics. Conversely, individuals who do not fit the image of the ideal victim or whose experiences deviate from the social imaginary can become marginalised, more likely to be disbelieved, or, if the crime cannot be denied, blamed for it by society. Christie argues that the construct of the ideal victim not only shapes the victim’s perception but also influences society’s response to crime, including the allocation of resources, judicial processes, and the provision of support services. According to Christie, several key characteristics contribute to constructing the ‘ideal’ victim (Christie 1986).

First of all, the perception that they are entirely blameless for what has happened to them is crucial. Society is much more likely to look favorably on victims who are perceived as ‘accidental’ victims of crime, where their actions, in the eyes of the public, did not in any way cause the crime, provoke it, or otherwise deserve it. Thus, in order for an individual to be seen as a victim, he or she must be perceived as not being responsible for the crime that has happened to them. If the victim is perceived as having somehow contributed to or provoked the acts committed against them, they are less likely to be believed or granted full victim status.

Another significant aspect, as emphasised by Christie (1986), is perceived vulnerability – where ideal victims are typically seen as fragile and incapable of defending themselves, which is conveyed through several characteristics. The age of the individual is often used to shape the perception of a vulnerable victim, with the ideal victim being described as elderly, sick, or very young. Perceived vulnerability is also constructed by emphasising the perpetrator’s superiority, with power imbalances perceived as a positive characteristic of the victim. This vulnerability evokes sympathy from those around the victim, as society prioritises protecting and supporting those perceived as most vulnerable.

Another key characteristic of the “ideal” victim, according to Christie (1986), is moral righteousness. The victim is perceived as a morally upright person who adheres to the norms and values of society. They are often portrayed as virtuous and innocent, having not only refrained from provoking the crime against them but also adhered strictly to societal laws and norms. Such moral justice not only reinforces the belief that the crime occurred but also strengthens trust in the victim’s account of the event. When a victim aligns with societal ideals of morality and innocence, their testimony is more likely to be accepted as credible and accurate, reducing scepticism about the details of their experience. This dynamic reflects broader societal tendencies to equate moral character with truthfulness, making those who fit the “ideal victim” mold more likely to be believed without scrutiny. In contrast, victims who deviate from these moral and social expectations may face increased doubt, as their credibility is judged not only based on their testimony but also through the lens of societal biases. This distinction plays a crucial role in shaping public and institutional responses, ultimately influencing the level of support, empathy, and legal recognition that victims receive.

It is important that the victim not only adheres to the norms and values of society but also conforms to society’s expectations, especially regarding gender, race, and social status. Victims who align with traditional notions of femininity, race, and middle-class identity are often more readily accepted as real victims (Christie 1986).

As members of society, victims are influenced by socially accepted stereotypes that shape how they perceive and evaluate their own situations. If individuals cannot align with the common perception of an ideal victim, they may not see themselves as victims and might question their understanding of the situation. These reasons may lead the victim not to go to law enforcement for fear of not being perceived as a victim of crime.

Although Nils Christie primarily focuses on the characteristics and perceptions of victims, he also implicitly analyses the concept of the stereotypical perpetrator. Christie emphasises that the public’s perception of the victim is closely tied to the perpetrator’s perception, who is often seen as the opposite of the ideal victim. This stereotype constructs the perpetrator as someone who holds power, which can be understood as physical, economic, or other forms of dominance over the victim. This image of the perpetrator contributes to the narrative that frames them as stronger, more aggressive, and in control, further reinforcing the perception of the victim as vulnerable and helpless. In this way, the stereotype of the perpetrator is shaped to reflect an imbalance of power, encouraging society to view the victim as the weaker, more sympathetic party in the conflict.

According to Christie, the perpetrator is perceived as immoral, not conforming to society’s norms and social values. Such an individual is perceived as not fitting into society and is, therefore, unreliable and dangerous.

Another important feature, as noted by Christie (1986), is the perceived tendency towards deviant behaviour. Such characteristics are in complete opposition to the norms and expectations of society and, therefore, facilitate the attribution of blame and the complete condemnation of the perpetrator. This portrayal is internalised in the social imaginaries. It reinforces the dichotomy between victims and perpetrators, with victims embodying the qualities of innocence, vulnerability, and moral justice and perpetrators being portrayed as immoral and deserving of punishment. However, this superficial assessment of perpetrator and victim cannot reflect the individuals as a whole, making it difficult to assess real situations. It is worth noting that, according to N. Christie, these ideas affect public perception and the response to crime. Perpetrators who are perceived as fitting the stereotypes of the perceived perpetrator are more likely to be punished more severely, and victims who fit the stereotype are seen as more trustworthy and deserving of society’s help and support. Conversely, individuals who do not fit the stereotype of the ‘typical’ perpetrator, such as those who are well respected in society or who do not fit the prevailing stereotypes of delinquency, are likely to be treated more leniently. In contrast, victims who do not fit the stereotype of the ‘ideal’ victim are more likely to face disbelief and scepticism. The idea of the typical perpetrator can have the opposite effect to that of the ideal victim: if the perpetrator does not fit the traits attributed to him or her, society is more likely to believe in his or her innocence and, therefore, more likely to question the victim’s actions, thus enabling a culture of victim blaming (Christie 1986).

Susan Estrich further examined this stereotype-driven, idealised perception of the victim in her book Real Rape (1987), specifically focusing on societal expectations surrounding sexual crimes. She highlighted how these expectations create the belief that rape must adhere to certain defined characteristics in order to be recognised as a “real” crime. The focus of the book is the relationship between the perpetrator and the victim, with the view that rape is only real if the victim does not know the perpetrator, echoing the characteristics of the ideal victim already explored by Nils Christie. The use of excessive force and the importance of physical evidence are also emphasised, calling into question the reality of the situation and the victim’s willingness to resist in the absence of apparent injuries that would indicate resistance. This perspective became deeply ingrained, influencing societal attitudes and how law enforcement personnel assessed and interpreted situations, often shaping their judgments and decision-making processes (Estrich 1987).

Much later, in 2008, Jennifer Temkin and Barbara Krahé expanded on these ideas in their article “Sexual Assault and the Justice Gap: A Question of Attitude.” The authors highlighted the persistent societal perception of what constitutes a “real rape” and discussed how this stereotypical thinking contributes to the so-called “justice gap.” They supported their argument about the lack of justice with a statistical overview. Temkin and Krahé pointed to a discrepancy between the number of reports of sexual victimisation and the number of resulting convictions. This gap was analysed through interviews conducted with judges, other criminal justice professionals, and members of the public in an effort to understand the influence of the “real rape” stereotype on how such cases are handled (Temkin and Krahé 2008).

In her 2016 article “Societal Responses to Sexual Violence Against Women: Rape Myths and the ‘Real Rape’ Stereotype,” Barbara Krahé references both earlier works and emphasises that, despite changes in society and time, these problems have not diminished and are just as relevant as they were in 1987. In this publication, Krahé examines how rape myths and stereotypes influence various stages of the criminal justice process, from victims’ self-perception and reporting behaviours to police handling and jury decision-making. She emphasises that victims whose experiences do not align with the ‘real rape’ stereotype are less likely to recognise their experiences as rape and are less likely to report them. The article also highlights that police responses and jury decisions are often shaped by these stereotypes, leading to a greater likelihood that non-stereotypical cases will be dropped. Importantly, this work builds on previous research by expanding the analysis of victims’ self-understanding and illustrating how internalised myths about sexual violence affect not only institutional responses, but also survivors’ own interpretations of their experiences.

The media’s involvement is crucial in reinforcing these perceptions of perpetrator and victim. In order to create sensational news, situational representations are amplified by focusing on the abovementioned characteristics. This not only enables and encourages stereotyping but also creates a distorted perception of reality. As members of society are rarely directly exposed to crime, their perceptions are shaped by the mass media and their portrayal of reality. Stanley Cohen extensively analysed this concept of the media as the public’s contact with crimes in his 1972 book “Folk Devils and Moral Panics”. Cohen’s analysis of moral panics reveals how the media plays a key role in shaping and hyperbolising perceived threats, often leading to a heightened sense of anxiety. He coined the term “folk devils” to describe individuals or groups portrayed as embodying evil and blamed for society’s problems. The media identifies and demonises these individuals, which further fuels moral panic. This process is also an example of social constructivism, where social problems are constructed through media representations and public reactions (Cohen 2011). Mass media reflect socially acceptable realities by reinforcing the social imaginaries and, simultaneously, the stereotypes on which it is based. An excellent example of this is Schanz and Jones’ article “The Impact of Media Viewing and Victim Gender on Victim and Offender Blameworthiness and Punishment”, which analyses the impact of crime-related media viewing habits and victim gender on perceptions of guilt and punishment in sexual assault cases. Research has shown that people use media sources to learn about a wide range of topics and that what we watch on television influences our perception of the real world. Stereotypical sexual offences are often referred to as “real rape”. Potential jurors expect what they see to match the reality portrayed in TV crime dramas. The results of the study supported the hypothesis that increased media coverage contributed to a more stereotypical perception of sexual assault cases (Schanz and Jones 2024). Therefore, the role of mass media is significant in enabling stereotype-based perceptions of sexual offences. It is, therefore, important to consider the narrative shaped by the mass media to understand what specific stereotypes prevail in a given society.

Methodology

Media representations often shape public perceptions of forced sexual acts, which differ from legal interpretations. Public discourse on such crimes often leans on emotional judgments, exaggerating traits in the portrayals of both victims and perpetrators. This creates a rigid narrative of “real rape,” which influences social imaginaries and public attitudes. Therefore, this study explores the influence of societal stereotypes on perceptions of crimes against the freedom of sexual self-determination.

This research focuses on analysing online media articles to understand how sexual crimes are depicted, identifying prevalent stereotypes associated with such offences. The timeframe of 2020 to 2023 was chosen to capture recent trends in media reporting, ensuring the relevance of the analysis to current public discourse. Articles from three Lithuanian news websites – Delfi, LRytas, and Alfa.lt – were selected for their accessibility and potential influence on public opinion, as media outlets that produce the majority of articles on the topic. This selection ensures a comprehensive analysis by incorporating both mainstream and alternative perspectives. Delfi and LRytas, as leading news platforms, represent the mainstream media narrative. According to Gemius Audience data, which is widely recognised as a standard for measuring digital media consumption in the Baltic region, Delfi.lt consistently ranks as the most visited news portal in Lithuania, attracting millions of unique users each month. Meanwhile, Lrytas.lt, the digital successor to Lietuvos Rytas, once the country’s largest and most influential daily newspaper, continues to function as a dominant legacy media brand. On the other hand, Alfa.lt often publishes longer, more analytical articles, editorials, and politically nuanced content compared to the often faster, headline-driven format of Delfi or Lrytas. By including all three, the study captures a broader spectrum of reporting styles and perspectives, enriching the analysis of how media constructs public perceptions of sexual crimes. A total of 134 articles published between 2020 and 2023 were initially gathered using the keywords “rape” and “sexual violence”. After excluding duplicates and unrelated cases, 42 articles focusing on crimes against sexual self-determination were analysed using the MAXQDA2022 program. The primary analysis uses the following codes: titles of the articles, victim characteristics, perpetrator characteristics, situation description, and attribution of blame. These codes aim to categorise the most common stereotypes related to sexual crimes and how they are portrayed in online media.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Gender: The majority of articles on crimes of a sexual nature focus on female victims. Male victims are rarely featured (out of the 42 articles analysed, only two featured a male victim). The gender dynamics reveal the attitudes towards the victims of this type of crime and how their actions in the context of a given situation are evaluated in relation to their gender. The experience of the male victim is explored in detail, the facts and the reality of the incident are questioned: “But you did not write a statement about the abuse you suffered even then?”, “You could have called for help...”, “But can we trust your account of the abuse? (Sinkevičius 2023). This scrutiny of the details surrounding the incident and the victim’s actions goes beyond mere analysis. It reflects a deeper, often sceptical, examination of the victim’s account. Such scrutiny is typically reserved for cases where the victim does not conform to the socially accepted image of a “real” victim, as outlined in Nils Christie’s concept of the ideal victim. The gender of the victim plays a crucial role in determining whether they are recognised as a “real” victim, shaping the image of sexual crime victims and reinforcing the view that only women can be victims of such crimes.

While the perpetrators in all the analysed instances were male, traits commonly linked to masculinity, such as “strength” and “aggressiveness,” are not highlighted in the articles themselves. However, the titles of the articles tend to describe the perpetrators as inhuman monsters, constructing the perception that a normal human being could not act in such a way: “Target of Lithuanian sadists [...]”, “The horrifying ‘fun’ of monsters [...]”. This approach treats the gender of the perpetrator as a given, not needing emphasis since it is assumed that perpetrators will be male. Rather than focusing on their gender, the articles attempt to separate these individuals from “normal” men, pushing the idea that such crimes could only be committed by monsters, not by an ordinary person. This framing not only reflects Christie’s ideas about the perceived perpetrator but also makes it more difficult for society to accept when such crimes are committed by someone who does not fit this monstrous stereotype, reinforcing the belief that sexual crimes are committed by outliers, not everyday individuals.

Age: For female victims, the exact age of the victim is rarely focused on. The age of the victim is specifically included when the intention is to draw attention to the young age of the victim: “19-year-old girl”, “18-year-old victim”, or the significant age difference between the perpetrator and the victim: “40-year-old producer [...] 33-year-old medic [...] 22-year-old model”. In these cases, the victim’s age is often emphasised, frequently appearing in the article’s title. In other cases, the age of the victim is not mentioned explicitly but is conveyed through the description of the victim as a “young girl” or “young woman”. Young victims are considered particularly suitable to embody the personification of the ideal victim. The innocence conveyed by youth and the inability to defend oneself are more favourably accepted in society’s eyes (Christie 1986). The victim’s description through the lens of youth can be used to influence the reader’s perspective, creating an image of innocence or even a benevolent yet naïve individual who believes in the goodness of the world. The age difference further conveys a power imbalance, positioning the victim as weaker. Such portrayals in the media reinforce the impression that victims must be weak or helpless to be considered real victims worthy of sympathy and justice.

The perpetrator’s age is often conveyed as a symbol of maturity and responsibility for one’s actions. The perpetrator is far more often described as a “grown man”. This description of the perpetrator creates an image of masculinity that the perpetrator is more ‘powerful’ than the victim because of his age and maturity. It should be noted that, in contrast to the victim, the young age of the culprit is not seen as a positive characteristic. The authors of the article do not tend to present the young age of the perpetrator as a symbol of innocence, but rather, in such cases, they emphasize the age as a kind of attempt to escape criminal responsibility: “One of the perpetrators was a minor - he was only more than a year shy of 18 years of age, so the court had decided to have him remain free”.

Education and Employment: Education and employment are not mentioned in most articles. One article refers to the victim as a “student”, but this is more likely to be used to highlight the young age of the victim. Depiction of the victim’s occupation can serve different purposes. It can be used to portray the victim as a young, promising individual, for example, describing them as a “22-year-old model [...]”. In the second case, employment is framed critically, emphasizing socially unacceptable activities and associating the victim with their occupation: “Young girls […] provided sexual services for a monetary reward.” While the article does not explicitly blame the victims, it portrays them differently by referring to them as ‘prostitutes’ throughout, shifting the focus away from their victimhood and implying a less sympathetic narrative.

In contrast, other analysed articles focus on the individuals as victims without defining them by their occupation, emphasising their experience instead. This subtle blame-shifting is not very common among the analysed articles, but is noteworthy in its implications. More often than not, victims are portrayed in a positive light, but when their circumstances deviate too far from the ideal victim stereotype and cannot be overlooked, the narrative shifts. In these instances, the focus turns to the victim’s behaviour, choices, or background, which are framed as contributing factors to the crime. This shift in narrative serves to delegitimise the victim’s experience and reduce public sympathy, suggesting that they somehow played a role in their victimisation.

The perpetrator’s educational background is rarely mentioned in the articles, with a greater focus placed on their employment. Unlike the portrayal of victims, the employment of the perpetrator is highlighted, particularly when they are seen as socially accepted, well-regarded, or even respected members of society, such as politicians, doctors, or psychologists. This emphasis on their professional status constructs an image of authority and power.

Prior Offences: Another aspect that is the opposite of how the victims are characterised is the emphasis on previous transgressions. The articles often suggest that the perpetrators might have a history of prior offences, even when they do not have a criminal record, making it seem surprising or unusual that they have not been previously convicted. The perpetrator’s potential history of offences is constantly questioned, often suggesting that their past behaviour could have predicted the current crime. This approach aligns with Nils Christie’s concept of the “perceived perpetrator,” in which the individual’s criminality is seen as immediately apparent, either through their appearance, past behaviour, or actions. According to Christie, society expects perpetrators to be identifiable, and their criminal nature should be clear, often linked to some overt characteristic or social deviance. This idea reflects the notion that those who commit crimes must be outwardly distinct from others – individuals whose criminality is seen as predictable or self-evident. By constructing the perpetrator this way, the articles reinforce a simplistic and exaggerated view of criminality, where perpetrators are seen as outliers with a clear, trackable history of transgression.

Summarising, male victims of sexual offences are largely overlooked in media coverage, with their stories rarely receiving the same depth of attention as those of female victims. When male victims are mentioned, their descriptions are minimal and lack the emotive detail that might foster empathy from readers. In contrast, female victims are described more thoroughly, often characterised primarily by their age. They are frequently portrayed as young girls, a framing that emphasises their innocence and fragility. This disparity in representation suggests a tendency within the media to construct narratives that evoke greater sympathy for female victims. In contrast, the experiences of male victims remain overlooked and less relatable to the audience.

When analysing the portrayal of victims and perpetrators in media coverage, it becomes evident that different characteristics are selectively highlighted to create distinct narratives, emphasising certain traits of one group while disregarding the same aspects in the other. Victims are often portrayed as young, regardless of their actual age, to align with the ideal victim stereotype of innocence and vulnerability. In contrast, perpetrators are depicted as older or more mature, even when the age difference is minimal, to emphasise power, control, and premeditation. Details about victims’ employment and education are seldom mentioned, leaving these aspects of their lives largely unexplored. In contrast, significant attention is given to perpetrators’ employment status, especially when these details can be used to underscore a position of power and authority. Even without a criminal record, articles suggest a history of transgressions, reinforcing the idea of perpetrators as identifiable outliers whose deviance is predictable.

Methodology

To address the prevalence of stereotypes, this research also examined verdicts in criminal cases, as these verdicts offer a grounded perspective on the realities of sexual crimes. While the mass media focus primarily on preliminary reports and often downplay actual outcomes, court verdicts provide a critical context for understanding offender profiles, motives assessed during legal proceedings, and the real consequences of these crimes.

This study analysed verdicts collected from the Lithuanian Court Information System website, covering the period from 2017 to 2023. The time period was selected to ensure both the relevance and manageability of the dataset. These years represent the most recent full set of available court verdicts at the time of research and allow for the observation of potential changes or consistencies in judicial practices over time. The focus was exclusively on Articles 149(1), 149(2), 150(1), and 150(2) of the Criminal Code, selected for their relevance to the research objectives. Article 149 defines rape as engaging in sexual intercourse against a person’s will through physical violence, threats, or by exploiting their helpless condition, including cases involving multiple perpetrators. Article 150 defines sexual assault as satisfying sexual desire against a person’s will through anal, oral, or other physical contact using violence, threats, or by exploiting the victim’s helpless state, also including cases involving multiple perpetrators. The search criteria were consistently applied throughout the research to ensure accuracy and reliability.

To ensure random selection, the selected verdicts were coded by issuance date as unique case numbers, enabling ranking and systematic sampling. Every second verdict was included in the analysis, resulting in a total of 68 analysed verdicts. The search criteria were consistently applied throughout the research to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Although this method cannot capture the full scope of these crimes due to their high latency and the large number of unreported cases, it remains one of the most effective, at least in quantitative terms, for analysing prosecuted incidents. By examining court verdicts, this approach provides structured insights into the socio-demographic profiles of offenders, the circumstances under which these crimes are committed, and the legal reasoning used in assigning responsibility.

Criminal Court Verdicts on Sexual Violence (2017–2023)

The analysis of criminal verdicts on sexual crimes in Lithuania provides crucial insights that complement media content analysis by addressing gaps where certain facts are omitted or receive less emphasis. Court rulings serve as a primary source of information for the media, shaping public understanding of these crimes. By examining real case details, offender characteristics, and judicial reasoning, this analysis not only enhances the understanding of how such offences are prosecuted but also contributes to a broader perspective on criminal liability. These findings will be particularly relevant in assessing vignette-based interviews, offering a more comprehensive view of the legal and social dimensions of sexual crimes.

Official statistics on registered cases of rape and sexual coercion indicate a general decline between 2017 and 2023 (Information and Communications Department, 2024). While this trend might suggest a reduction in incidents, it is crucial to consider how broader social and geopolitical factors may have influenced both reporting patterns and the judicial process. For example, the 2021 – 2022 migrant crisis along the Belarus border diverted public attention and government resources toward national security, potentially shifting law enforcement priorities and straining institutional capacity to address other legal matters, including sexual violence. Similarly, national lockdowns and curfews during the COVID-19 pandemic – particularly in spring 2020 and late 2020 to early 2021 – likely limited victims’ ability to seek help or report crimes. The gradual easing of pandemic restrictions may have further shaped public behaviour, access to support services, and institutional responses, all of which could have impacted the number of reported cases.

An analysis of verdicts issued for sexual crimes during the period from 2017 to 2023 reveals fluctuations in the number of cases processed by the courts. The highest number of analysed verdicts was recorded in 2017 (13 verdicts), while the lowest occurred in 2022 (4 verdicts). These variations may not only reflect changes in crime reporting and case initiation but also shifts in judicial efficiency, prosecutorial focus, and broader systemic challenges affecting the progression of cases through the legal system.

Analysing the content of the verdicts, it is notable that while media articles often emphasise major cities, criminal cases frequently originate from smaller towns and rural areas.

Interestingly, during the analysed period, the highest number of court verdicts for sexual crimes was issued in Panevėžys, a city of approximately 85,000 residents. This is notable because Panevėžys surpassed Lithuania’s largest cities – Vilnius (with around 600,000 residents), Kaunas (about 300,000), and Klaipėda (roughly 150,000) – in the number of adjudicated court verdicts. Another unexpected trend is that Šiauliai, a city of about 100,000 people, had the same number of cases as Kaunas and even exceeded Klaipėda in court verdict volume. A possible explanation for this pattern is that courts in larger cities may face consistently heavier caseloads, which could contribute to longer processing times for sexual crime cases. Rather than being temporary fluctuations, these delays may reflect enduring structural challenges – such as high case volumes, limited judicial capacity, or the greater complexity of cases typically seen in urban jurisdictions. This raises concerns about whether victims in such areas experience disproportionately delayed access to justice, potentially undermining confidence in the legal system and affecting the overall effectiveness of judicial responses to sexual violence.

Additionally, nearly half of the incidents analysed in court took place in towns and smaller cities with populations below 100,000, significantly smaller than Lithuania’s five largest urban centres. This distribution suggests that sexual crimes are not solely concentrated in major metropolitan areas but are also prevalent in smaller communities. These trends raise important questions about regional differences in crime reporting, judicial efficiency, and access to legal resources (Official Statistics Portal, 2024).

Socio-demographic features

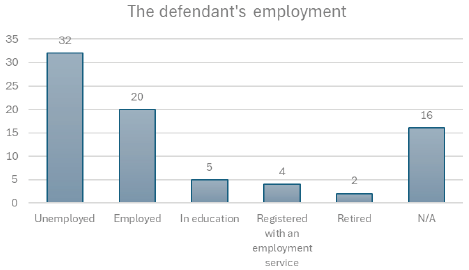

In the analysis of the mass media, it is noticeable that employment is only mentioned in relation to the perpetrator when employment is perceived as significant and respected in society. However, it is worth noting that, in the analysed court verdicts, a significant number of defendants were unemployed, not pursuing education, and not registered with employment services at the time of the incident. This reinforces the notion that employment, in this type of media coverage, is leveraged to shape public perception of the perpetrator, portraying them as a powerful and influential figure rather than providing an accurate depiction of the individual. (Table 1).

TABLE 1. The defendant’s employment

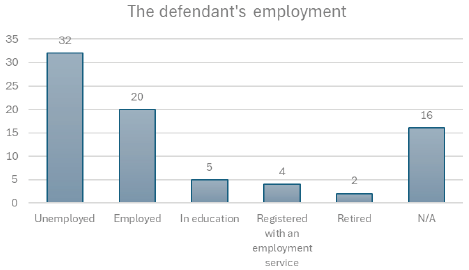

The analysed media content gives minimal attention to the personal characteristics of the perpetrator, such as marital status. While this aspect is frequently explored in academic literature, loneliness and a compulsion to forcefully achieve desired intimacy are often highlighted as key explanations for sexual offences. The analysis of criminal convictions reveals that a significant proportion of defendants are either single or divorced. Such aspects of the perpetrator’s personal life, including marital status, may hold relevance to understanding the nature of the offence and the underlying factors contributing to their actions. (Table 2).

TABLE 2. The defendant’s marital status

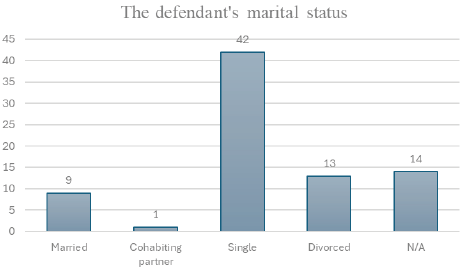

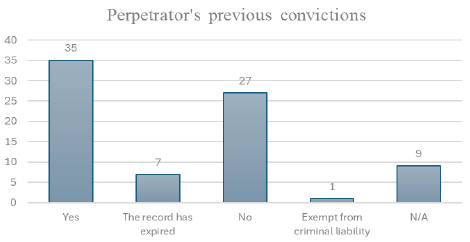

One notable feature highlighted in the analysed publications is the perpetrator’s prior criminal record. This aspect is frequently mentioned in media articles, regardless of whether the individual has a criminal history. Additionally, the nature of the previous offence for which the perpetrator was convicted is not considered or clarified. When analysing criminal case verdicts, it is noticeable that, although a large proportion of defendants have previous convictions, only a relatively small portion of them have previous convictions for a sexual offence. It is also worth noting that a correspondingly high proportion of defendants have no previous convictions, although the media’s emphasis on the defendant’s criminal record gives the impression that the individuals committing these offences are “hardened criminals”. (Table 3)

TABLE 3. Perpetrator’s previous convictions

Sentencing

In criminal cases, sentencing is guided by legal frameworks that ensure fairness and proportionality. According to Article 61 of the Lithuanian Criminal Code, courts determine sentences based on the nature of the crime, its consequences, and the degree of guilt of the offender. A key aspect of this process is the consideration of aggravating and mitigating factors. Aggravating factors, such as repeated offences, cruelty, or targeting of vulnerable victims, can lead to stricter penalties. Conversely, mitigating factors, such as sincere remorse, cooperation with authorities, or acting under duress, may result in a more lenient sentence. Unlike aggravating factors, which are explicitly defined in law, mitigating factors are more flexible and can include a variety of case-specific elements that may reduce an individual’s level of responsibility.

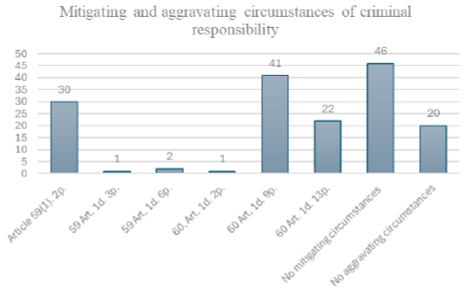

One of the most commonly identified mitigating factors in the analysed verdicts was based on Article 59(1)(2) of the Lithuanian Criminal Code (LR BK). This provision applies when an offender acknowledges their guilt, expresses genuine remorse, or assists in identifying others involved in the crime. Recognising this mitigating factor reflects the offender’s willingness to take responsibility for their actions and an understanding of the harm caused. It should be noted that applying this mitigating factor does not require the victim’s forgiveness – only a formal apology from the perpetrator. This is problematic because it allows the offender to potentially receive a reduced sentence simply by offering an apology, regardless of the victim’s feelings or willingness to forgive. It also overlooks the victim, treating them more like evidence in the case rather than an individual whose experience and voice should be central to the process. This practice does not align with a victim-centred approach or principles of restorative justice, which prioritise the needs, dignity, and healing of the victim. Instead, it places more emphasis on the offender’s actions without adequately considering the emotional and psychological impact on the victim, potentially allowing for a more lenient sentence without fully acknowledging or addressing the harm caused.

Of the 68 cases analysed, two instances identified mitigating circumstances under Article 59(1)(6) of the Lithuanian Criminal Code, where the victim’s provocative or risky behaviour was considered to have influenced the occurrence of the offence. While the court rarely acknowledges such circumstances, defendants frequently attempt to justify their actions by highlighting the victim’s provocative or risky behaviour. This tactic was particularly evident in appeals, where defendants sought to discredit the victim by introducing additional witnesses and scrutinising the victim’s actions. For example, in one case, the defendant’s lawyer argued: “Throughout the evening, as on previous occasions, [the victim] acted in an overtly sexually provocative manner – pinching, stroking, sitting on and sleeping on [the defendant’s] lap, voluntarily consuming alcohol and recalling what she drank, stepping outside to smoke cannabis and cigarettes, interacting normally with others, and agreeing to stay overnight at the apartment. She undressed herself and did not cry out or resist, despite having the opportunity. The next morning, she made no complaints to her friend about rape and continued to socialise before fabricating a story about the incident to justify her absence to her strict parents.” (E.N. v. D.G., 2022). Similarly, in another case, the defence argued: “Late-night drinking, interacting with two strangers, and willingly going to their apartment led to the conflict and the potential offence. Such behaviour was clearly provocative and risky.” (Ž.J. v. M.P., 2020). Despite these attempts, courts rarely acknowledge such victim behaviour as a mitigating factor.

In contrast, courts are more likely to recognise aggravating circumstances in criminal liability. A common aggravating factor, cited under Article 60(1)(9) of the Lithuanian Criminal Code, is when the offender committed the offence under the influence of alcohol, drugs, or other psychotropic substances. This reflects the significant role substance use plays in sexual offences, as intoxication can impair impulse control, leading to misinterpretation of victim behaviour and the excessive use of force (Horwath and Brown 2006). Similar to media narratives, substance use is viewed negatively only in relation to the offender.

The second most frequent aggravating factor was repeat offences under Article 60(1)(13) of the Lithuanian Criminal Code. As previously noted, prior convictions significantly influence both judicial proceedings and media narratives, shaping perceptions of offenders. (Table 4).

TABLE 4. Mitigating and aggravating circumstances of criminal responsibility

In Lithuania, when determining a sentence for a crime, the court first considers the minimum and maximum penalties specified in the Criminal Code for that offence. It then calculates the average of these two values, which serves as the starting point for the sentence. The court may adjust the sentence within this range, depending on the presence of aggravating or mitigating factors, such as the severity of the crime or the offender’s behaviour. This approach ensures that the punishment is proportional to the crime while still allowing flexibility based on case-specific circumstances.

Article 149 of the Criminal Code deals with rape. The punishment for this crime can range from a maximum of 7 years in prison for the least severe cases to up to 10 years if the crime was committed by a group of offenders. Article 150 addresses sexual coercion. The punishment for this crime can range from arrest to up to 6 years in prison. If the offence is committed by a group of offenders, the punishment can increase to up to 8 years.

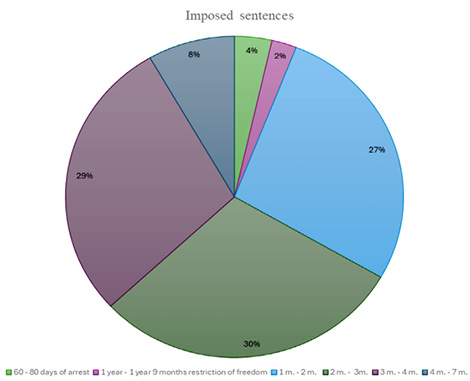

In the analysed court verdicts, custodial sentences are the most common. For the most serious offences assessed – Article 149(2) and Article 150(2) of the Criminal Code, which involve crimes committed by a group of accomplices – the sentencing outcomes are varied. While the most common sentences are 3 and 4 years of imprisonment, sentences exceeding 4 years are less frequent. The average sentence, derived from the sanction outlined in the articles, is between 4 and 5 years. However, more than half of the sentences imposed fall well below this average.

For the other two offences, governed by Articles 149(1) and 150(1) of the Criminal Code, the ranges of imprisonment are identical, with Article 150(1) also allowing for an alternative penalty of arrest. Despite this provision, the alternative penalty is rarely applied. The most common custodial sentences for these offences are 2 and 3 years of imprisonment, with sentences of 4 years being less frequent. While the average sentence for these offences is 3.6 years, a significant proportion of sentences fall below this average. Across all the offences analysed, the average sentence is 3 years and 2 months, with 3 years of imprisonment being the most frequently imposed sentence, lower than the average prescribed by the sanctions.

It is important to note that sentences below the average require the presence of mitigating circumstances. However, in this analysis, no mitigating circumstances were identified for 46 defendants. This highlights the individualisation of sentencing based on case-specific details and the role of statutory guidelines in shaping judicial outcomes. (TABLE 5).

Summarising, there are significant differences between the media’s portrayal of the perpetrator and the actual characteristics of the perpetrator. The analysis of court verdicts in criminal cases shows that most of the perpetrators are unemployed and not registered with the employment service. However, such individuals are not highlighted in the media. Occupation is often emphasised when it is perceived as significant or respectable. This portrayal can be used to create a more powerful image of the perpetrator. It is important to note that this choice not only presents the perpetrator as being in a position of power but also may be aimed at creating sensational articles. Previous convictions of the perpetrator are emphasised in many publications, but the type of crime for which the previous conviction was issued is often ignored. Many perpetrators have prior convictions, but few have been convicted of sexual crimes. It is also observed that a significant portion of the perpetrators have no prior convictions, yet the media creates an image of them as “hardened criminals.” These aspects reflect a distorted reality constructed by the mass media.

Table 5. Imposed sentences

Analysing criminal court verdicts is essential not only to gain a broader understanding of elements overlooked by mass media but also to establish a benchmark for evaluating how informants assign punishments in these cases and how these compare to real-life outcomes. While sentences are often de-emphasised in media coverage, they play a critical role in shaping public perceptions of the seriousness and societal impact of such crimes. These narratives can influence how the public views the nature of the crimes, their importance from the state’s perspective, and the roles of both the victims and the perpetrators.

Methodology

To analyze the connection between stereotypes and the attribution of guilt in sexual crimes, it is crucial to assess how manifestations of stereotypical traits within specific scenarios influence individuals’ opinions. Therefore, vignette-based interviews were selected as the research method. This approach allows for the creation of controlled and standardized scenarios that closely resemble real-life situations involving sexual crimes. By presenting vignettes to participants, the method evaluates how stereotypes affect the perception and assessment of specific situations, as well as the attribution of guilt in realistic contexts. It offers insight into participants’ thought processes and decision-making.

The main aim of this study is to reveal the influence of stereotypes on the attribution of guilt in situations shaped by stereotypes, focusing on understanding how individuals perceive and assign blame in various scenarios.

Selection of Groups

1. General Population (Laypersons)

This group comprises individuals from diverse demographic backgrounds who are not directly associated with law enforcement or journalism. Their perspective is crucial because they represent the broader societal understanding of crime, justice, and victimhood, unshaped by professional training or institutional biases. Unlike police officers, who operate within the legal system, or journalists, who frame crime narratives for the public, laypersons rely on personal experiences, cultural norms, and media portrayals to form their views. Including them ensures a more comprehensive understanding of public attitudes and potential gaps between professional and societal perceptions of criminal justice. The ‘snowball’ sampling method was used, where participants recommended others for the study. This ensured a diverse range of participants with varied experiences and opinions, better reflecting societal views. The method also ensured that participants were aware of the sensitive topics beforehand, enabling them to recommend others based on their comfort with such discussions (responses from this group are coded as I1, I2, I3, and so on).

2. Police Officers

This group consists of law enforcement officials of various ranks and years of experience. They were chosen because police officers serve as the first point of contact between victims and the criminal justice system, playing a crucial role in how cases are handled from the outset. Their initial response, attitudes, and decision-making can significantly influence a victim’s willingness to cooperate, the quality of evidence collected, and, ultimately, the outcome of a case, as the ones responsible for gathering statements, securing forensic evidence, and determining whether an investigation proceeds, their perceptions, and biases can shape the trajectory of justice. Understanding their views provides insight into potential systemic challenges, the implementation of legal protections, and the overall effectiveness of law enforcement in addressing these crimes. A criterion-based selection method was used, focusing on police officers as participants (responses from this group are coded as P1, P2, P3, and so on).

The sample size for each group was not predetermined and was based on data saturation during the study. A total of 11 vignette-based interviews were conducted, 4 with police officers and 7 with members of the public.

Ethical Considerations

Given the sensitivity of the topic, strict adherence to ethical research principles was maintained throughout the study. While the vignette-based interview method minimizes potential harm by creating a safe and controlled environment for discussion, participants were not forced to share personal experiences that could trigger negative reactions.

At the start of the interview, all participants were informed about the nature of the study and the themes of the vignettes. This enabled them to assess the potential emotional impact and decide whether to participate. Participants were also informed of their right to withdraw at any stage. Confidentiality was ensured throughout the study.

Interview Tool

A semi-structured interview guide, incorporating scenario descriptions (vignettes), was used to gather responses about attributing guilt and stereotypes. Interviews were conducted individually with each participant. Two different vignettes, supplemented with variations, were presented to each participant. These scenarios reflected key stereotypes about sexual crimes. Each vignette, along with its additional details, was presented sequentially. Participants were verbally introduced to the scenario and given a physical card describing the situation.

After hearing the scenario, participants were asked open-ended questions, such as:

1. How would you assess this situation?

2. How would you attribute responsibility for this situation?

3. If you believe this was a crime, what punishment would you consider appropriate?

This approach aimed to understand how participants perceive the attribution of guilt in specific situations.

The Vignettes

Vignette 1

A young woman studying at the university and living with her parents reports to the police that she was raped. She claims the perpetrator is her neighbor, a married businessman she knows well. The neighbor denies the allegations, claiming the woman misunderstood his friendly behavior, tried to seduce him, and is now retaliating out of anger. According to the woman, the assault occurred while she was home alone; the man came over, learned her parents were not home, made vulgar remarks, and sexually assaulted her on the couch. There are no direct witnesses, and she did not tell anyone about the incident.

Alternative Detail:

1. The suspect is unemployed, divorced, and has a history of domestic violence. He was intoxicated when he visited the woman’s home.

This vignette was designed to evaluate the importance of changes in the perpetrator ‘s characteristics within the scenario. Its construction drew upon findings from the analysis of criminal case verdicts, which highlighted the significance of traits such as employment status, social ties, marital status, and substance use. Additionally, insights from media analysis were incorporated, focusing on aspects that tend to receive greater attention in portrayals of the perpetrator. The victim’s description aligns with the ‘ideal victim’ stereotype – a young woman engaged in socially acceptable activities. This profile remained unchanged throughout the scenario to assess how judgments of actions vary based on specific changes in the perpetrator’s characteristics.

Vignette 2

A middle-aged woman reports to the police that she was drugged and raped. She claims she did not know the perpetrator beforehand. According to her, the man bought her drinks at a bar, encouraged her to drink, and offered to walk her home when she felt dizzy. As she entered her home and walked through the door, he forced his way in behind her, gaining entry. Once inside, he dragged her to the bedroom and sexually assaulted her. She suspects she was drugged because the level of intoxication she experienced that night was far greater than what she typically feels after consuming a similar amount of alcohol. The perpetrator is described as a young, promising university student who volunteers at an animal shelter. He denies the allegations, claiming he does not remember meeting the woman. Bar staff recall the woman leaving the bar unsteadily, leaning on the suspect.

Alternatives:

1. The man acknowledges that the sexual encounter took place but asserts it was consensual. He explains that both he and the woman were intoxicated, which makes it difficult for him to recall specific details. However, he remains confident that their actions were mutually agreed upon.

2. The woman is revealed to engage in sex work.

3. The woman is portrayed as a frequent club-goer, dressed provocatively, and seen dancing with various men.

4. Traces of drugs are found in the woman’s system, but she is uncertain whether she took them herself, as she has experimented with drugs in the past, or if she was unknowingly drugged by the man.

This vignette focused on variations in the victim’s characteristics and their influence on perceptions. Its design drew on findings from media and verdict analysis, where factors such as provocative behavior and substance use were often criticized.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using MAXQDA 2022 software, applying qualitative content analysis. Responses were grouped by vignette variations and categorized based on three criteria:

1. Scenario evaluation

2. Attribution of guilt

3. Evaluation of consequences

Limitations

The findings are specific to stereotypes prevalent in Lithuania and reflect the opinions of individuals living in this context. Vignettes, even well-designed ones, may not fully capture the complexity of real-life situations. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into how stereotypes influence perceptions of guilt in sexual crimes.

Interview Analysis

Due to the nature of the interviews, the informants’ responses were categorized into three essential segments: assessment of the situation, attribution of responsibility, and evaluation of consequences. These three aspects were analyzed within the context of the discussed scenarios, with the primary objective of examining how perspectives evolved in relation to specific situations.

Assessment of the Situation

Firstly, after familiarizing themselves with the vignette details, all informants were asked to evaluate the situation. This part aimed to understand the informants’ perception of the situation’s realism through the aspect of the crime’s ‘authenticity.’ Trust and belief in the victim’s account were pivotal in such evaluations.

For most informants, assessing the situation was significantly easier regarding the first vignette than the second. When evaluating the first vignette, some informants were inclined to believe that the crime had occurred, justifying their stance by their willingness to trust the victim’s account: ‘[…] My initial opinion is that the crime did happen, and the girl […] must have had a reason to report to the authorities […]’ (I2), ‘[…] At first glance, it seems like it could have happened. […] I’d like to trust the girl; otherwise, why would she report it to the police?’ (I3), ‘[…] Statistically, it’s more likely that a man would assault a woman than a woman lying about it.’ (I4).

Police officers also shared a similar perception: ‘[…] If the girl perceives it this way, I would probably believe her.’ (P4).

However, some informants mentioned that evaluating the situation based on the given details was challenging, emphasizing the need for further investigation to identify physical injuries: ‘[…] For me, there’s not enough detail to say for sure because it’s just one word against the other – it means nothing.’ (I4), ‘I’d be curious to know how much time passed before she reported it and if any physical tests could confirm whether there was sexual contact or signs of violence. If there was resistance, there should be marks.’ (I5).

Informants who felt the situation lacked sufficient details were also more likely to suspect possible deception by the victim, suggesting that her motives behind the report could stem from financial gain or a desire for retaliation: ‘Maybe the girl has motives […] she just wants revenge or something like that.’ (I5).

It is noteworthy that two of the four police officers interviewed stated they would consider not only physical evidence but also assess the victim psychologically when evaluating her testimony: ‘[…] You’d look at the person from a psychological perspective as well, observing her behavior and body language to see if she might not be entirely truthful.’ (P2), ‘It depends on how she tells the story – her physical and emotional state plays a big role in this.’ (P4).

Although the suspect’s characteristics were not initially highlighted as a significant factor in this evaluation, they gained significance during reassessment when positively perceived traits were replaced with negative ones. In such cases, most informants were more likely to trust the victim’s account: ‘At this point, I have no doubt […] it’s obvious. I think the man is guilty, and the crime definitely occurred.’ (I4).

Factors such as alcohol consumption were also emphasized as influencing criminal behavior: ‘[…] He was drunk, so you can expect less rational behavior from him.’ (I6), ‘He arrived intoxicated […] I wouldn’t doubt the man’s guilt.’ (I2).

Previous offenses were also cited as a reason to view the suspect as prone to committing crimes: ‘[…] The man is probably inclined to criminal activity since he has a prior record.’ (I5), ‘Because he has past convictions, it’s likely he hasn’t changed […]’ (I6), ‘Considering his history, it increases the likelihood […]’ (I7).

This view was also reflected among some officers: ‘He’s divorced and has been convicted before, so this is a pattern for him […]’ (P4).

When shifting to the second vignette, informants displayed a notable change in evaluation. While they were more inclined to believe a crime had occurred in the first vignette, this belief was now motivated less by trust in the victim and more by distrust toward the suspect: ‘It sounds suspicious when the student says he doesn’t remember the woman or being at the bar – it sounds like he’s lying […]’ (I3), ‘He denied being at the club, but employees saw him there.’ (I4), ‘[…] It’s suspicious that the guy doesn’t admit he actually escorted the woman out […]’ (I5).

A similar perspective was shared by officers: ‘[…] I detect […] some lying […] The guy is lying – he’s guilty.’ (P4).

Some informants were also critical of the victim’s state and ability to accurately recall and interpret the event’s details: ‘She might exaggerate to get money out of him or for revenge.’ (I6), ‘If she was staggering, it could have been the alcohol; she might be imagining things or even hallucinating depending on what she consumed.’ (I7).

This skepticism was further amplified when the vignette was supplemented with additional details, creating a possibility for misunderstanding or misinterpretation. Informants increasingly leaned toward the suspect’s perspective, attributing the victim’s perception of the situation to alcohol consumption and a change of heart after the fact: ‘[…] They both drank, went home, and had consensual sex. Later, maybe he insulted her, and now she wants revenge […]’ (I6), ‘Just regretting sleeping with someone doesn’t mean it was rape.’ (I5), ‘Both were intoxicated – it’s likely mutual, and the woman might simply not remember and now feels guilty.’ (I2), ‘I would lean toward the guy’s side, thinking he was falsely accused.’ (I3).

‘Some informants, although not fully willing to believe the suspect’s position, emphasized the importance of physical evidence in confirming the victim’s account: ‘[...] she should be able to prove that the crime was committed against her.’ (I5). Officers expressed similar thoughts: ‘[...] the whole set of evidence should be considered, whatever they may be.’ (P2).

A significant focus was placed on the victim’s socially unacceptable actions in assessing the situation. This is evident in the inclusion of elements in the vignettes, such as the victim providing sexual services for money, frequently visiting nightclubs, and wearing provocative clothing.

A large portion of the informants used these elements to justify the victim’s desire to profit or deceive the suspect in some way: ‘She just wanted his money and did not get it [...] he ordered and did not want to pay, and in this case, she just wanted to get her money back or take revenge for not getting paid.’ (I6), ‘They sat down, both drank, and she took him home.’ (I5), ‘[...] maybe he just didn’t pay, and now she is lying.’ (I5), ‘It really changes the perception when she is providing sexual services for money [...] maybe the guy did not pay.’ (I2), ‘According to witnesses [...] the victim drinks and dances with all sorts of men, so in this case, maybe the girl was not raped, but just like the previous middle-aged woman, she is lying to profit from the guy.’ (P4).

Although the informants saw the possibility that the situation could have occurred regardless of the victim’s occupation or leisure activities, they again stressed the need for physical evidence to confirm the victim’s account. This conveys a sense of distrust arising from negatively evaluated aspects, such as socially unacceptable employment, alcohol consumption, and frequent visits to nightclubs. Still, it is worth noting that even partial physical evidence, such as the detection of narcotic substances in the victim’s body, despite the absence of direct proof that she took them herself, encouraged informants to place more trust in the victim’s position. Although the possibility of intoxication was mentioned in all variations of the second vignette, the actual discovery of these substances in the victim’s system had a significant impact on the assessment of the situation: ‘[...] maybe he put something in her drink.’ (I6), ‘Even if drugs were found, I think it could have been the guy is doing [...]’ (I3), ‘Since drugs were found, I am inclined to think she was drugged [...]’ (I2).

It is also notable that in this situation, the informants were more critical of the suspect’s actions, despite the actions themselves remaining unchanged: ‘Another interesting thing is that the guy thinks consent is when they drank together and she took him home. That is not consent in essence; if those were the only acts of consent, the guy clearly did not understand the situation [...]’ (I5), ‘[…] I think the guy will be guilty [...] it was all because of the guy’s initiative.’ (P4).

Attribution of Responsibility

The second aspect was the division of responsibility for the situation. The goal here was not only to assess whether the suspect was guilty but also to evaluate the roles of individual actions that may have contributed to the incident.

In the first vignette, while the suspect was blamed for the crime, some informants noted a lack of self-protection on the victim’s part, such as inviting the man into her home. However, these actions were viewed more through the lens of naivety rather than culpability: ‘Why did she let him into her home?’ (I2), ‘It is unsettling to invite a neighbor over when alone. [...] I would assign about 30% of the blame to the girl for inviting him without thinking it through.’ (I3). ‘20% to the girl for letting him in, even if he is a neighbor.’ (I4), ‘[...] 100% the man is to blame, but again, some safety measures could have been taken, like, for example, not letting the man in.’ (I5). In the extended vignette, it is observed that the victim’s actions are more often justified by emphasizing the unpredictable behavior of an intoxicated person: ‘I would not resist an intoxicated person if they came to me [...]’ (I2), ‘[...] the girl just, I do not know, for some reason invited him home, but it sounds like she had no intention, no desire to have sex with that guy.’ (I3).

Again, a slightly different perspective on the situation emerges within the framework of the second vignette. Regardless of whether the informants believed that the crime occurred or not, they were inclined to critically assess the victim’s actions and their significance in the context of the situation. This focus was on the fact that the victim was alone and went home with the suspect from the bar: ‘But I would partly say the girl is also at fault because she was drunk and went home with a stranger, did not call her friends or trusted acquaintances, and just let him escort her home.’ (I4).

There is also much emphasis on alcohol consumption, associating it with irresponsibility. It is worth mentioning that within the context of this vignette, the intoxication of both the victim and the suspect is assessed differently. In the case of the victim, it is seen as a sign of irresponsible behavior, with the focus on the fact that the girl consumed alcohol by choice, and that influenced the outcome of the situation: ‘So, I think, in reality, the guy would be about 65% at fault, and the rest is the woman’s fault, again because of the alcohol and the lack of memory, and because she acted irresponsibly.’ (I3), ‘[...] the girl drank too much and should have just not overdone it with the alcohol, and maybe this would not have happened then.’ (I3), ‘[...] she was not forced, nobody poured alcohol into her [...] so neither is completely innocent.’ (I5), ‘[...] the woman allowed herself to be drunk [...] they were in a public place, she could have refused in any case [...]’ (I5).

In the case of the suspect, alcohol consumption is viewed as a mitigating factor for his actions. Although it is stated that one should not engage in sexual relations while intoxicated, it still provides the possibility of the situation being misinterpreted from the guy’s side. Therefore, the actions are not seen as right, but rather as the result of alcohol, not the individual’s actions: ‘[...] when considering both of their intoxications, I would say that neither side is to blame [...]’ (I2).

It is noteworthy that in the case of a woman providing sexual services for money, The man’s responsibility is not acknowledged, regardless of whether the informants were inclined to believe the victim’s account or thought she made a false accusation due to unpaid money, the informants were more likely to shift the responsibility for the situation onto the woman: ‘The blame is entirely on the woman because she is involved in illegal business, selling herself.’ (I2), ‘I think the fault here would be the woman’s.’ (I3), ‘[...] this will be the woman’s fault that this situation happened.’ (I6).

Although most informants placed greater responsibility on the victim in the vignette where the girl’s provocative clothing was mentioned, they frequently felt compelled to stress that, regardless of her attire, it should not be a factor in justifying or influencing the commission of a criminal act. They emphasized that the crime itself remains unjustifiable, regardless of how the victim presents herself: ‘I really do not want to be that stereotypical person who says that if you dress like this, then you are to blame [...]’ (I2), ‘The first thing is provocative clothing [...] if you want to protect yourself from that, I think you should dress more modestly. However, if you like it, why not?’ (I6). This sentiment is especially evident among the interviewed officers: ‘How she is dressed does not change anything, not at all [...] that way of dressing and interacting with other people does not say anything about a person.’ (P2), ‘[...] in my opinion, people can dress however they want [...] that should not increase the risk [...]’ (P1).

Consequences of the Situation

The final task that the informants were asked to do was to evaluate the consequences of the situation. In this step, the informants were asked to assume the role of a full authority judge to make the most appropriate decision based on their discretion. The question was intentionally phrased so that it did not lead them to think that punishment had to be assigned. Instead, they were asked how they would choose to resolve the incident if they were a judge and this particular case was presented to them. This approach encouraged the informants to think critically about the situation without expecting a specific outcome, allowing them to focus on the broader implications of the case and how they would handle it from a judicial perspective.