Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2025, vol. 16, no. 1(32), pp. 56–88 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2025.16.3

Unlocking Financial Potential: Self-efficacy Transforming Capability into Well-Being for Working Women

Priya Gupta (corresponding author)

Indira Gandhi University, India

priyagupta0265@gmail.com

priya.comm@igu.ac.in

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-4887-7042

https://ror.org/044kc7a79

Mamta Aggarwal

Indira Gandhi University, India

mamta.commerce@igu.ac.in

https://ror.org/044kc7a79

Meera Bamba

Indira Gandhi University, India

Meerabamba@gmail.com

https://ror.org/044kc7a79

Abstract. The primary purpose of this study is to identify the influence of financial capabilities on women’s financial well-being and to study the mediating influence of self-efficacy in this relationship in Delhi-National Capital Region (NCR). The data were collected through purposive sampling using a questionnaire distributed from February to May 2024 to Delhi-NCR women engaged in any economic activity. Delhi-NCR is a metropolitan area encompassing Delhi and its surrounding districts in neighbouring states. Data analysis was performed on 250 responses from working women using purposive sampling. Variance-based Partial Least Square Structure Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was applied to test the conceptual model. This study operationalizes and validates financial capabilities as a reflective higher-order construct formed by two dimensions such as financial literacy and inclusion. Findings illustrate that financial capabilities directly influence working women’s financial well-being, and this relationship was partially mediated by financial self-efficacy. To improve women workers’ financial well-being, such policies and programs should be tailored to boost women’s confidence levels and beliefs, education, and inclusion in the financial dimension. This study directs policymakers, government, employers, and financial institutions to build confidence levels among women by organizing workshops and programs, which promotes their financial well-being and ultimately empowers them financially.

Keywords: financial capabilities, financial well-being, financial self-efficacy, empowerment

Received: 22/7/2024. Accepted: 23/4/2025

Copyright © 2025 Priya Gupta, Mamta Aggarwal, Meera Bamba. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

In the dynamic landscape of personal finance, understanding the factors that influence well-being has been crucial, especially for women workers who engage in economic activities and contribute to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Working women often face new opportunities and obstacles in their path to financial well-being. Women are disproportionately underrepresented in the economy due to their greater likelihood of adverse socio-economic conditions such as low education, lack of engagement in employment, high unpaid care work burden, and higher poverty rates (Seedat & Rondon, 2021). The numerous disadvantages faced by women influence their financial well-being. While the concern related to gender disparity exists all over the world, researchers indicate that India experiences a substantially higher gap due to socio-cultural norms, limited access to financial services, economic participation and restricted opportunities. According to the Worldd Economic Forum (2024), India ranks 142nd out of 146 countries in terms of economic participation and opportunities, placing it in the bottom five countries globally. At the same time, developed countries such as the United States (22nd), France (48th) and the United Kingdom (58th) exhibited higher women’s economic participation.

In contrast, developing and underdeveloped countries lag. Furthermore, in India, the female labour force participation rate stands at 24% compared to 47% globally (Ministry of Labour and Employment, 2023). Similarly, in terms of education, India stands 112th out of 146 countries in terms of gender gap in educational attainment. This gap is notably higher than in developed countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany and others (World Economic Forum, 2024). Additionally, DHS (2021) reported that the literacy rate for females in India is 71.5%, compared to that of men at 84.7%. These facts illustrate that the concern related to gender disparity is more pronounced in developing and underdeveloped nations than in developed countries, where gender parity prevails regarding better access to education, economic participation, etc.

In the context of developing economies like India, women are less likely to have some education and engage in income-generating activities than their male counterparts due to their involvement in unpaid care work at home (Biswas & Banu, 2023; Deshpande & Kabeer, 2024). Due to socio-cultural norms, pressure of care work, and low education levels, women are more likely to engage in precarious employment, which may be low-paying or lack security (Alemu et al., 2022).

Women are the most vital contributors to the development of any economy, as they constitute approximately half of the total population (Gupta et al., 2025; Selvaratnam 1988; Singh & Pattanaik, 2020; Thaddeus et al., 2022). The development of any nation can even be imagined as the significance of the role of women in the economy (Ibourk & Amaghouss, 2014). Women in the workforce are pivotal contributors who manage many responsibilities at home and in their professional lives. Due to this, there are variety of factors other than the professional attainments that influence their financial success (Koekemoer et al., 2023).

The United Nations (2008) highlights the significance of several sustainable development goals such as gender equality and women empowerment, decent work for all, good health and well-being recognizing that these are vital for building the inclusive and sustainable societies.

The first vital step in attaining the gender equality and women’s well-being is to equip them with adequate financial means and self-assurance to make independent financial decisions. The key component for being independent and accumulating wealth is financial literacy, competence, inclusivity, and self-assurance in handling them. Women with adequate financial resources and capabilities possess greater knowledge (Naami et al., 2023). They are equipped with the proper tools to manage their finances and make independent financial decisions, which contributes to narrowing the gender gap in economic engagement.

The concept of financial well-being has garnered more attention from the government, policymakers and scholars in recent times, particularly in the context of women, as it is one of the critical aspects of economic empowerment, a key to attaining sustainability (Rashid et al., 2022; Reed et al., 2021). It is pivotal for achieving gender equity and economic development (Sorgente et al., 2023; West et al., 2021). In the context of emerging economies like India, despite numerous initiatives by the government to promote women’s access to financial services, they continue to face barriers to effectively managing the financial resources and attaining the well-being. Financial well-being is a critical determinant of overall life satisfaction, particularly in the context of women who have multiple work responsibilities such as managing personal expenses, savings and financial planning (Brüggen et al., 2017; Gupta et al., 2025; Rahman et al., 2021). Despite having stable incomes, women workers in India face numerous challenges due to limited access to financial services, financial literacy gaps, limited utilization of financial services and low financial efficacy (Mishra et al., 2024; Peter et al., 2025). These critical issues prevent them from efficiently managing their finances, saving for the future and making informed financial decisions. While some research on financial literacy and well-being exists in the literature (Ahmad et al., 2024; Muleke & Muriithi, 2013; Philippas & Avdoulas, 2020), the concept of financial capabilities concerning well-being and the mediating influence of financial efficacy remains unexplored, especially in the context of working women. Addressing this critical gap is essential for policymakers, financial institutions, and governments aiming to enhance women’s economic empowerment.

To resolve the research problem, this work examines how financial capabilities (financial literacy and inclusion) directly or indirectly through financial efficacy influence financial well-being. This work provides evidence of the significance of literacy, inclusion, and efficacy in improving women’s economic safety, security, and satisfaction.

This study explores how financial capabilities impact the financial well-being of employed women, specifically focusing on the mediating influence of financial self-efficacy. First, it uniquely integrates financial capabilities with self-efficacy. It examines their impact on financial well-being, while previous work conducted by Bojuwon et al. (2023), Kumar et al. (2023), Prameswar et al. (2023), and Ahmad et al. (2024) studied these factors separately. Secondly, this work explicitly targets female workers, a vital Indian demographic often underrepresented in financial domain studies, as Giraodone et al. (2021) stated. It contributes to the academic understanding of financial well-being and has practical implications for advancing sustainable development. This work specifically focuses on working women in the Delhi-NCR region and integrates the psychological concept of self-efficacy with finances and its alignment with development goals for fostering gender equality and economic growth.

Financial behaviour includes the abilities, information, and inclusivity needed to make wise judgements that substantially influence the economic behaviour (Manda & Mwakubo, 2014). Knowing how well financial well-being, efficacy and financial capacity interact with each other might help female workers in attaining the financial security for the future. The findings from this study can inform policymakers, educators, researchers, and financial institutions about the formulation and implementation of targeted interventions that foster financial literacy, inclusion, and confidence levels among employed women. Such initiatives are vital for sustainable development and ensuring women’s equal participation in adequately navigating financial challenges and opportunities. This work derives academic inquiry and practical implications for a more equitable, inclusive, and prosperous society by providing valuable insights and targeted actionable interventions.

This work is structured in seven major sections. Following the study’s introduction, Section 2 provides the literature review on financial capability, efficacy and well-being. Section 3 highlights the study’s conceptual framework and provides basis for hypotheses development. Section 4 indicates the material and methods used to attain the objectives. Section 5 highlights the study’s findings and Section 6 presents the conclusion and implications. Finally, Section 7 presents some limitation of the work along with directions for conducting future research work.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Financial Capabilities

Financial capabilities refer to individuals’ knowledge, skills, and appropriate behaviour for making informed and effective financial decisions (Hoelzl & Kapteyn, 2011). They encompass the ability to manage financial services properly and the opportunities to access and use them (Allmark & Machaczek, 2015).

Sharraden et al. (2017) state that financial capabilities is the combination of the opportunities and abilities to act. This suggests that having access to opportunities is a component of financial competency, which extends beyond merely possessing of financial resources. Financial capabilities provide an individual supportive environment where they can achieve their financial well-being. Johnson and Sherraden (2007) laid the groundwork for understanding the concept of financial capabilities at the personal and structural levels. It integrates abilities and opportunities to position it as a dualistic idea encompassing personal and systematic dimensions (Naami et al., 2023). At an individual personal level, literacy and inclusion integration reflect the ability to act. Financial literacy encompasses skills, knowledge, and experience related to finance that can be adequately acquired through education, guidance, socialization, and personal experiences (Tripathi et al., 2022). Financial inclusion consists of financial access and social policies that can contribute to individuals’ financial capabilities (Nandru et al., 2021).

Financial capability is the capacity and chance to take actions, which can be based on individuals skills as well as the access, availability, usage, and dependency of financial services (Birkenmaier et al., 2013).

Based on theoretical and empirical foundations, this work conceptualizes financial capabilities as a single item which comprises financial literacy and inclusion. Financial capability framework highlights that individuals can attain financial wellness when they have access to financial services and ability required to make informed and wise decisions (Sun & Chen, 2022; Xiao & Huang, 2022). Financial capability includes the ability and opportunity to act (Birkenmaier et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2022; León et al., 2024). Previous literature highlights that access to resources does not ensure well-being unless individuals have information to use them appropriately (Khan et al., 2022; Xiao, 2015). Similarly, financial inclusion may lead to over-indebtedness unless individuals possess sufficient knowledge to manage their financial affairs (León et al., 2024; Van Nguyen et al., 2022). Numerous studies report that people with access to financial services and right information are better able to manage money and attain long-term financial security (Ahmad et al., 2024; Rashid et al., 2022).

2.2 Financial Self-Efficacy

Bandaru (1977) first introduced the self-efficacy theory as part of social cognitive theory. It refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to accomplish a task. Financial self-efficacy is a vital psychological factor affecting individuals’ responsiveness to their financial situation and their ability to make decisions (Chong et al., 2021).

It implies an individual’s confidence in their capabilities to manage their financial affairs effectively and make sound decision-making (Olajide et al., 2023). It influences individuals’ ability to handle financial matters and their engagement in financial planning (Noor et al., 2020). It encompasses several dimensions. First, it indicates an individual’s belief in managing day-to-day affairs as stated by Sabri et al. (2021). Second, it represents individual confidence in making sound financial decisions related to investment, loans, and retirement planning (Farrell et al., 2016). It also entails the individual capability to effectively address the financial obstacles in their path to financial empowerment (Pavani & Alagwadi, 2023). Overall, it represents individual confidence in planning future financial needs and goals, such as retirement and financial planning (Arafat & Leon, 2020).

2.3 Financial Well-being

Well-being is a holistic measure of an individual’s quality of life and happiness (Kun & Gadanecz, 2022). It is a multifaceted concept that consists of various dimensions of life, such as social, financial, physical, and emotional (Weziak-Bialowolska al., 2021). Financial well-being is critical, encompassing a person’s ability to manage their day-to-day financial affairs and resilience against economic shocks (Singh et al., 2019).

Financial well-being means meeting current obligations, feeling secure for the future, making choices, and enjoying life to the fullest (Kempson et al., 2017). It encompasses controlling day-to-day financial obligations and meeting financial goals to attain financial freedom. Financial well-being is not just about having financial resources (Taft et al., 2013). It comprises individuals’ ability to use resources to achieve adequate financial security and resilience. It involves effective day-to-day money management and includes budgeting, saving, and controlling spending. Proper control over finances reduces financial distress and contributes to well-being (Gerrans et al., 2014). It ensures savings for emergencies and resources for bearing crises (Philippas & Avdoulas, 2020).

Existing studies show that individuals with higher knowledge make better savings, credit and investment decisions, leading to future financial securities (Lone & Bhat, 2022; Rahman et al., 2021; Sabri et al., 2023). Ahmad et al. (2024) conducted their study on the youth in Jordan and reported that financial knowledge enhances an individual’s ability to manage financial risk and prepares them for future uncertainties. Individuals with low financial literacy scores tend to face higher financial difficulties in managing their financial affairs (Rapina et al., 2023). Higher financial knowledge is associated with more asset accumulation and proactive financial management (Kumar et al., 2023). Furthermore, financial access empowers individuals by reducing their worries due to adequate opportunities for saving money, borrowing and investing in different avenues to protect themselves from future financial risk (Binsuwadan et al., 2024; Rashid et al., 2022).

Additionally, financial efficacy, a psychological indicator, implies that an individual’s belief and confidence in accomplishing a specific task is critical in improving well-being. The study reported that individuals with high self-efficacy in managing financial matters tend to experience enhanced well-being (Nam, 2022). They feel confident by taking proactive control over their financial lives, leading to their well-being (Handayati et al., 2023). An individual with low efficacy struggles in making financial decisions, which leads to the situation of financial distress, anxiety and dissatisfaction (Farrell et al., 2016).

The concept of financial well-being has garnered much attention in recent years. However, only a limited number of studies are available in the literature which examine the influence of financial capabilities on financial wellness in the context of working women in India. Studies are mainly focused on isolated concepts such as financial literacy inclusion and overlook the broader concept of financial capabilities. However, a few studies undertaken in the context of female workers have captured the unique barriers they face. Mainly, research has been concentrated on other countries with minimal exploration in the Indian context, where socio-cultural factors play a pivotal role. This work bridges this gap by examining the influence of financial capabilities on well-being with the mediating effect of financial efficacy in the context of female workers in India.

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1 Financial Capabilities and Well-being

Financial capabilities are vital for ensuring individual and societal well-being (Sun & Chen, 2022). Financial capabilities and well-being are two vital interconnected concepts related to personal financial health (Nam, 2022). Financial capabilities encompass knowledge, skills that indicate the ability to act, and opportunities to manage financial affairs efficiently. Financial well-being means being financially safe, secure, and free from financial distress (Zyph et al., 2015). Existing studies examine the theoretical foundation and its empirical relationship with well-being in different contexts. Financial capabilities integrate literacy and inclusion, essential for ensuring financial stability, well-being, and individual development (Al Rahahleh, 2023). They encompass knowledge, skill, and attitude for optimal financial resource management, allowing people to make rational financial decisions and improving their financial well-being (Kumar et al., 2023). Financial inclusion implies accessibility of financial services to all groups, particularly the marginalized (Panakaje et al., 2023). Financial inclusion enables a person to save and earn more interest, leading to more wealth accumulation (Nandru et al., 2016). It ensures greater participation in the economy, providing more opportunities for employment and entrepreneurship (Bojuwon et al., 2023). It helps individuals build their economic status through saving and accessible funds for managing emergencies.

Guo and Huang (2023) stated that improved capabilities lead to positive financial behavior and outcomes, such as improved income, savings, financial security, and reduced debt. Xiao (2016) elaborates that individuals with better financial capabilities are more likely to invest, budget, and have the financial plan for their retirement, which ultimately contributes to their improved well-being. Huang and Guo (2020) stated that financial capabilities focusing on education and inclusion promote financial stability, ultimately contributing to their financial wellness. Financial capabilities are pivotal for managing daily expenses and avoiding excessive debt pressure. They also lead to better asset and investment management, enabling individuals to build their financial wealth and improve their financial security (Xiao, 2016). However, limited work has examined the influence of financial capabilities on financial self-efficacy and well-being.

3.2 Financial Capabilities, Self-efficacy and Well-being

The conceptual framework for this work is grounded on the capabilities approach adapted from Naami et al. (2023). This approach emphasizes the individual’s abilities to attain the outcome, such as financial well-being based on the resources and agency or skills. As depicted in Figure 1, financial capabilities can be achieved when an individual possesses the knowledge and skills of financial literacy to act in financial interest. Furthermore, capabilities depend on the opportunities the financial system provides for appropriate access to and usage of financial services. The framework is based on the capability approach propounded by Sen (1980). This individual-centered framework focuses on individuals’ financial capabilities along with just access to the resources. This framework is suitable for this work as it emphasizes how financial literacy, inclusion and self-efficacy enables women to live meaningful lives. The term “agency” describes individuals’ capability to make their own decisions and follow through on them in order to attain the desired objectives (Kabeer, 1999). The capability approach evaluates well-being through an individual’s quality of life, relying on resources and agency/ ability to act capabilities. This theory propounds that for attaining well-being, mere having access to resources is not enough until women have adequate capabilities in achieving the same (Sen, 1980). Building on this foundation and empirical work, this model proposes that financial capabilities are the combination of the financial knowledge and access to resources that influence the financial well-being. This study is conducted to investigate the influence of resources (financial access) and agency (financial literacy and efficacy) on women’s financial wellness. Furthermore, based on empirical evidence, financial efficacy is introduced as a mediator in this work, which implies that individuals’ confidence and belief in their abilities to handle the financial matters improves the conversion of skills into well-being. Financial services remain underutilized when individuals have access to services but need more knowledge to utilise them appropriately. Concerning working women, achieving financial capabilities requires a multifaceted approach that includes ensuring access to inclusive financial services and enhancing their financial inclusion to create an environment supporting their economic participation and financial well-being.

Figure 1

Conceptual Framework of the Study

High financial literacy boosts individual confidence in managing financial affairs effectively. Raj (2020) stated that engagement and participation in literacy programs improve personal confidence and capability for managing financial tasks. Knowledge, skill, and understanding of financial concepts bolster the confidence and ability to navigate complex financial mechanisms (Taft et al., 2013). By effectively understanding and applying the financial concepts in their personal lives, individuals can gain better control over their financial situation and reduce their financial distress (Lone & Bhat, 2022). Through the accessibility of financial services, people feel more empowered and begin to take control of their financial lives (Noor et al., 2022). Based on the existing literature, we propose Hypothesis 1:

H1: Financial capabilities positively influence financial well-being in the context of working women.

The acquisition of more knowledge, skills, and experience boosts individual confidence levels in managing financial tasks to attain their financial goals (Lone & Bhat, 2022). Improved financial literacy leads to better confidence in managing financial affairs effectively (Ariati et al., 2023). Access to banking and literacy boosts individuals’ belief, faith and confidence in effectively managing the financial affairs (Wijaya et al., 2019). Limited research work examines the collective influence of financial literacy and inclusion in the form of capabilities on financial self-efficacy. Nonetheless, this work aims to test this relationship empirically by examining the proposed hypothesis:

H2: Financial capabilities positively influence financial efficacy in the context of working women.

Financial self-efficacy is an individual’s belief in their ability to manage financial tasks to make informed decisions (Singh et al., 2019). It consists of individual belief in the ability to achieve the desired task through their action plan (Nam, 2022). Literature suggests that financial self-efficacy is vital in determining financial well-being. Fostering individuals’ confidence and equipping them with the required tools can help them make informed decisions, effectively manage their finances, and attain financial stability (Sabri et al., 2021). Education, accessibility, and confidence can substantially improve their financial well-being (Lone & Bhat, 2022). Therefore we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Financial efficacy positively influences financial well-being in the context of working women.

Existing studies report that financial literacy provides knowledge of different financial concepts, and financial inclusion ensures access. Still, belief and confidence in managing financial affairs effectively are vital, so financial efficacy becomes vital.

According to prior studies, financial inclusion guarantees access, while literacy imparts awareness and knowledge of financial concepts. However, financial efficacy becomes vital since it is crucial to have faith, belief and trust in effectively managing the financial affairs (Kiplangat et al., 2023; Lone & Bhat, 2022; Obenza et al., 2024). Without having confidence and belief, individuals with adequate knowledge and access may struggle to make informed decisions, which limits their well-being (Karystin et al., 2024; Mulasi & Mathew, 2022). Studies reported that financial efficacy strengthens the impact of financial literacy and inclusion by enabling women to have adequate control over their financial lives, contributing to their wellness (Kiplangat et al., 2023; Lone & Bhat, 2022; Nam, 2022; D. Singh et al., 2019). Based on the gap identified from the existing literature, Hypothesis 4 is formulated as follows:

H4: Financial efficacy mediates the relationship between financial capabilities and financial well-being in the context of working women.

4. Materials and Methods

This survey was conducted in the Delhi-NCR using a structured questionnaire. The participants were approached in four cities of Delhi-NCR: Gurugram, Noida, Delhi, and Rewari. The area was chosen due to its high occupational and socio-economic diversity. This area consists of communities from different regions of India. This cross-sectional survey was conducted for four months through purposive sampling, from February 2024 to May 2024. Only women currently working in any economic endeavour were considered for the study.

4.1 Data and Sampling

This study uses a quantitative cross-sectional design to evaluate the direct and indirect impact of financial capabilities on the well-being of employed women. The key criteria used for selecting the respondents was their employment. Numerous existing studies report that employed women are more likely to engage in financial activities (Barik & Lenka, 2022; Mehry et al., 2021). The study population consists of women working in IT, education, healthcare, and the corporate sector, as well as the self-employed in the significant areas of Delhi-NCR. Primary data was collected from the Delhi-NCR area using purposive sampling. This method ensures that the sample includes all relevant respondents needed for the research. The whole questionnaire is divided into three main sections. The first section elaborates on the study’s objective and significance, giving respondents assurance regarding the safety and security of their personalized information. The second section entails the respondents’ personal information, such as age, gender, income, region, household head, type of employment, income, etc. Finally, financial sections represent statements based on multiple underlying constructs of this study such as financial literacy, inclusion, self-efficacy, and well-being, on a rating scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree.

The required sample size was determined through G*Power analysis (Kang, 2021). G* power software 3.1.9.7 was used to determine the adequate sample size (Faul et al., 2007). With a power of 0.95, an effect size of 0.058, and a 5% significance level for the variables in the proposed framework, a sample size of 226 respondents was obtained with the noncentrality parameter value 3.6204972. In G*power, the noncentrality parameter measures the magnitude of the effect or deviation from the null hypothesis (Faul et al., 2007). However, this study applied data analysis to 250 respondents, which exceeded the required minimum criteria and satisfied the appropriate sample size. The estimation regarding the minimum sample requirement is reported in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 2

G* Power Analysis

Table 1

G* Power Analysis Results

|

Input Parameters |

Output Parameters |

||

|

Tails |

Two |

Noncentrality |

3.6204972 |

|

f2 |

0.058 |

Critical t |

1.9706590 |

|

α |

0.05 |

Df |

223 |

|

Power (1- β err Prob) |

0.95 |

Sample size |

226 |

|

No. of predictors |

2 |

Actual power |

0.9500045 |

Note. Table generated through G* power software. Firstly, a pilot survey was conducted with 50 working women respondents to ensure questionnaire clarity, language, acceptance, and understanding. Finally, after ensuring acceptability, further data was collected from women respondents for the final study. For this work, 400 female respondents were approached. Out of them, 280 female respondents filled the questionnaire. Among 280 responses, 30 questionnaires had missing values in certain sections related to the main variables. Therefore, these responses were removed from the final analysis part. Two hundred fifty working women filled out the questionnaire with almost all the data required for analysis. However, some optional questions, particularly related to additional income sources, were not answered by some of the mentioned respondents. These questions were included to gain further insights rather than to test the primary research model. This study offers reliable and comprehensive data for analysis using this comprehensive data technique.

4.2 Measures

This study used a variety of measurement scales to examine the relationship between underlying constructs. Financial capabilities are a higher-order construct measured through financial literacy and the inclusion as lower-order constructs. Financial capabilities are taken as independent variables in this study, measured through financial literacy and inclusion. Financial literacy was measured through an eight-item scale adapted from Noor et . (2022). An eight-item scale was adapted from Arafat and Leon (2020) to measure financial inclusion. Financial capabilities were assessed based on financial inclusion and literacy level, as indicated by Naami et al. (2023). Financial self-efficacy was measured using a five-item scale adapted from Mindra and Moya (2017). Financial well-being, which served as a dependent variable, was assessed using a six-item scale adapted from FPB Financial Well-Being Scale (2017). A Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5) was used to measure all the relevant constructs of the study. Variable categories, their classification, and scale adoption are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Underlying Constructs and Their Measurement

|

Variable Type |

Variable Name |

Scale Adoption |

|

Independent Variables |

Financial Literacy |

Scale adapted from Noor et al. (2022) |

|

Financial Inclusion |

Scale adapted from Arafat and Leon (2020) |

|

|

Dependent Variable |

Financial Well-being |

Scale adapted from CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale (2017) |

|

Mediating Variables |

Financial Self-efficacy |

Scale adapted from Mindra and Moya (2017) |

4.3 Common Method Biasness (CMB)

The possible results of the reliability and validity tests are threatened by common method biases, which arise when there is inaccuracy in gathered responses rather than any statistical error (Jordan & Troth, 2020). In order to distinguish the findings, it is vital to control these typical method biases, particularly when measuring both dependent as well as independent variables using data derived from the same survey. Kock (2017) suggests two primary methods to control the survey-based CMB: statistical and procedural control methods. The statistical method requires calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) to assess the CMB. When the VIF value is less than 3.33, bias control is deemed to be adequate. Procedural control entails giving respondents adequate information about the anonymity of their responses and the significance of their active participation in the survey, with questions presented after establishing their content validity. Statistical as well as procedural steps were undertaken in the research work to lessen the likelihood of these kinds of biases. All the items with VIF less than 3.33 pass the bias control requirement and confirm that no issue persists regarding the multicollinearity. Both positive and negative items were included in the procedural procedure to adjust the effect of acquiescence and dissent bias (later on reversed during data analysis).

4.4 Tools and Techniques

PLS-SEM, which is based on nonparametric variance, is employed for data analysis and hypotheses testing (Ringle et al., 2015). It is most suitable for researchers in social and behavioural science to make predictions. PLS-SEM is chosen over covariance based SEM (CB-SEM), because it can handle the complex models and higher order structures and produces accurate predictions (Hair et al., 2019). This technique is more versatile because it works with small and medium sample sizes and does not require that the data have a normal distribution (Saari et al., 2021). This technique emphasizes prediction and explains variance in the endogenous constructs (Sarstedt et al., 2017). In order to predict the financial well-being based on capabilities and self-efficacy, this work uses PLS-SEM, which is more in line with these study goals. This study aims to predict financial well-being based on capabilities and self-efficacy, and using PLS-SEM aligns more with the objectives.

5. Results

This section provides an overview of the results obtained by analyzing the primary data.

5.1 Respondent Profile

Table 3 provides a detailed overview of respondents’ profiles, related to the respondents’ demographics. Findings report that most working women belong to the age group of 26 to 35 (nearly 36.4%), closely followed by the age group 14 to 27 (almost 90%). Meanwhile, the minority working women group consists of the women who are 45–60 years old (nearly 8.8%). The highest number of working women in the dataset completed their Master’s degree (almost 50.4%), followed by Bachelor’s degree (21.65%). Additionally, the smallest number of women completed their doctoral degree, making 11.15% of the sample. The distribution indicates a substantial prevalence of advanced degrees among the working women in the dataset. While analyzing the region, most working females in the dataset belong to the urban area (about 56%), followed by the semi-urban region (16.4%). The highest number of the working women in the dataset are full-time workers (about 50%), followed by self-employed (about 26.4%). A high proportion of working women in the dataset earn below Rs 2,50,000 (48.8%), followed by the income group of Rs 2,50,000 to 5,00,000 (about 32.4%). The highest number of women report that male family members head their households. About 48.8% of the respondents are married, closely followed by single women in the dataset. Along with this, a large proportion (about 50.4%) of working women reported from 5 to 7 members in their family. In the initial stage of this work, the subgroup analysis of financial well-being based on the socio-economic and demographic profiles were carried out, however, it was found out that financial well-being does not vary substantially across the different groups. The results align with existing studies that provide that these factors don’t influence the financial well-being (Bhatia & Singh, 2024; Prameswar et al., 2023). As the differences are not substantial, this work does not emphasize these factors while interpreting the results.

Table 3

Respondents Information

|

Variable |

Specification |

No. |

% |

Financial well- |

|

Age |

14-25 |

90 |

36% |

0.470 |

|

26-35 |

91 |

36.4% |

||

|

36-45 |

47 |

18.8% |

||

|

45-60 |

22 |

8.8% |

||

|

Education |

Secondary |

10 |

4% |

0.510 |

|

Senior Secondary |

32 |

12.8% |

||

|

Bachelor’s |

54 |

21.65% |

||

|

Master’s |

126 |

50.4% |

||

|

PhD or another professional course |

28 |

11.15% |

||

|

Employment |

Part-time |

59 |

23.6% |

0.066 |

|

Full time |

125 |

50% |

||

|

Self-employed |

66 |

26.4% |

||

|

Annual Income |

Below 2,50,000 Rs |

122 |

48.8% |

0.136 |

|

2,50,000- 5,00,000 Rs |

81 |

32.4% |

||

|

5,00,000-10,00,000 Rs |

37 |

14.8% |

||

|

Above 10,00,000 Rs |

10 |

4% |

||

|

Region |

Urban |

140 |

56% |

0.274 |

|

Rural |

69 |

27.6% |

||

|

Semi-Urban |

41 |

16.4% |

||

|

Marital Status |

Single |

103 |

41.2% |

0.125 |

|

Married |

122 |

48.8% |

||

|

Divorced/separated |

16 |

6.4% |

||

|

Widowed |

9 |

3.6% |

||

|

Household Head |

Male |

176 |

70.4% |

0.698 |

|

Female |

74 |

29.65 |

||

|

No. of Members |

1-4 |

96 |

38.4% |

0.539 |

|

5-7 |

126 |

50.4% |

||

|

More than seven members |

28 |

11.2% |

5.2 Measurement Model

The literature review shows that financial capability is a second-order construct with two sub-dimensions. Hence, the measurement model consists of a second-order reflective-reflective model validated using a two-stage disjoint analysis. The first stage involved examining the reliability and validity of all lower-order constructs.

5.2.1 Assessment of Lower-Order Construct (LOC)

The reliability and validity of the lower-order construct were initially examined. Measures such as Factor Loading, Cronbach’s alpha, VIF, rho, and AVE were calculated to test the construct’s internal consistency, reliability, and convergent validity (see Table 4). Cronbach’s alpha tested the internal consistency of the data obtained during the primary survey. The value of Cronbach’s alpha is more than 0.7 and satisfies the threshold requirement stated by Hensen (2001).

Factor loading represents the strength or relation between the item and the specified construct. The higher the loading, the better the indicator represents the underlying construct. The factor loading of one item, FWB3, was 0.325, indicating low loading, and has more influence on AVE for financial well-being, which initially stands at 0.489. Due to low loading, this item has been removed from the analysis. Deleting this item ensures a higher AVE of the construct financial well-being, enhancing the overall construct validity. In all other cases, the loading of all items exceeds 0.708 except item FI1 (loading 0.672) and FWB 6 (loading 0.604). However, the loading of these two items was below 0.708. Still, the AVE for the construct remains above 0.5. Sarstedt et al. (2017) highlight that the items whose loading lies within the range of 0.4 to 0.7 are still acceptable for running the measurement model if the AVE of the underlying construct is more significant than 0.5. Convergent validity of the construct was measured through AVE. It is validated using AVE greater than 0.5, specified by Hair et al. (2022). VIF was used to detect multicollinearity; VIF less than 3 confirms no multicollinearity problem in the dataset.

Table 4

Construct Reliability, Validity and Multi-Collinearity

|

Construct |

Items |

Loading |

VIF |

Mean |

SD |

Cronbach’s |

CR |

CR |

AVE |

|

Financial Inclusion |

FI1 |

0.672 |

1.599 |

3.752 |

1.009 |

0.867 |

0.879 |

0.898 |

0.558 |

|

FI2 |

0.757 |

2.047 |

4.204 |

1.153 |

|||||

|

FI3 |

0.608 |

1.767 |

3.840 |

1.226 |

|||||

|

FI4 |

0.785 |

2.014 |

3.836 |

1.089 |

|||||

|

FI5 |

0.787 |

1.963 |

3.816 |

1.113 |

|||||

|

FI6 |

0.830 |

2.573 |

4.004 |

1.119 |

|||||

|

FI7 |

0.769 |

2.275 |

3.868 |

1.204 |

|||||

|

Financial Literacy |

FL1 |

0.826 |

2.664 |

4.116 |

0.916 |

0.931 |

0.932 |

0.943 |

0.676 |

|

FL2 |

0.830 |

2.739 |

4.032 |

1.046 |

|||||

|

FL3 |

0.768 |

2.149 |

3.676 |

1.056 |

|||||

|

FL4 |

0.813 |

2.425 |

3.984 |

0.946 |

|||||

|

FL5 |

0.832 |

2.576 |

3.948 |

1.036 |

|||||

|

FL6 |

0.857 |

3.006 |

4.172 |

0.911 |

|||||

|

FL7 |

0.836 |

3.034 |

4.028 |

0.990 |

|||||

|

FL8 |

0.813 |

2.548 |

4.008 |

1.008 |

|||||

|

Financial Self-efficacy |

FSE1 |

0.788 |

1.695 |

3.700 |

0.931 |

0.842 |

0.847 |

0.888 |

0.614 |

|

FSE2 |

0.765 |

1.670 |

3.660 |

1.012 |

|||||

|

FSE3 |

0.728 |

1.574 |

3.796 |

0.997 |

|||||

|

FSE4 |

0.845 |

2.120 |

3.784 |

0.956 |

|||||

|

FSE5 |

0.788 |

1.827 |

3.588 |

1.036 |

|||||

|

Financial Well-Being |

FWB1 |

0.736 |

1.576 |

3.288 |

1.022 |

0.807 |

0.832 |

0.866 |

0.567 |

|

FWB2 |

0.843 |

2.037 |

3.612 |

1.080 |

|||||

|

FWB4 |

0.817 |

1.875 |

3.548 |

0.971 |

|||||

|

FWB5 |

0.742 |

1.554 |

3.564 |

0.991 |

|||||

|

FWB6 |

0.604 |

1.309 |

3.480 |

1.005 |

Note. CR= Composite Reliability; SD= Standard Deviation; AVE= Average Variance Extracted; VIF= Variance Inflation Factor. Results were obtained using PLS-SEM.

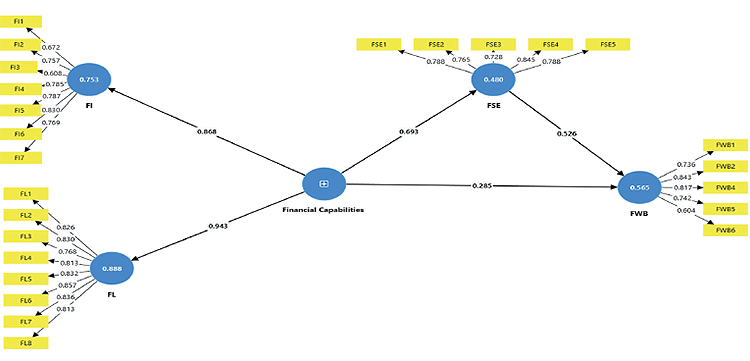

Figure 3

Measurement Model

Note. Results were obtained using Smart PLS.

Additionally, Henseler et al. (2015) specified that discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio and FornellLarcker criteria. A threshold of less than 0.9 was used to confirm the discriminant validity. Based on the findings reported in Table 5, all the underlying constructs meet the criteria by confirming the discriminant validity. All the constructs were found to be reliable and valid. FornellLarcker’s criteria compare the square root of each construct’s average variance explained (AVE) with correlations between that and other constructs in the model. The model confirms the discriminant validity as the square root of AVE for each construct is higher than the higher correlations between the constructs.

Table 5

Discriminant Validity Using FornellLarcker and HTMT

|

Constructs |

FI |

FL |

FSE |

FWB |

|

Fornell and Larcker criteria |

||||

|

FI |

0.747 |

|||

|

FL |

0.652 |

0.822 |

||

|

FSE |

0.553 |

0.685 |

0.784 |

|

|

FWB |

0.548 |

0.620 |

0.723 |

0.753 |

|

HTMT ratio |

||||

|

FI |

||||

|

FL |

0.712 |

|||

|

FSE |

0.635 |

0.772 |

||

|

FWB |

0.647 |

0.700 |

0.856 |

|

Note. PLS-SEM results. FI= Financial Inclusion, FL= Financial Literacy, FWB= Financial well-being, FSE= Financial Self-efficacy.

Table 6 reports the items’ cross-loading, highlighting that each item represents higher loading in their intended latent variable than another. This pattern indicates a solid discriminatory power of the constructs. This elaboration distinguishes the constructs under investigation and boosts confidence in the specified model.

Table 6

Cross Loading

|

FI |

FL |

FSE |

FWB |

|

|

FI1 |

0.672 |

0.372 |

0.374 |

0.420 |

|

FI2 |

0.757 |

0.424 |

0.342 |

0.343 |

|

FI3 |

0.608 |

0.331 |

0.298 |

0.329 |

|

FI4 |

0.785 |

0.519 |

0.422 |

0.477 |

|

FI5 |

0.787 |

0.560 |

0.449 |

0.480 |

|

FI6 |

0.830 |

0.628 |

0.510 |

0.425 |

|

FI7 |

0.769 |

0.508 |

0.457 |

0.385 |

|

FL1 |

0.543 |

0.826 |

0.529 |

0.477 |

|

FL2 |

0.555 |

0.830 |

0.539 |

0.565 |

|

FL3 |

0.498 |

0.768 |

0.602 |

0.477 |

|

FL4 |

0.507 |

0.813 |

0.542 |

0.478 |

|

FL5 |

0.546 |

0.832 |

0.599 |

0.586 |

|

FL6 |

0.550 |

0.857 |

0.566 |

0.514 |

|

FL7 |

0.574 |

0.836 |

0.582 |

0.505 |

|

FL8 |

0.516 |

0.813 |

0.548 |

0.473 |

|

FSE1 |

0.445 |

0.540 |

0.788 |

0.651 |

|

FSE2 |

0.454 |

0.556 |

0.765 |

0.545 |

|

FSE3 |

0.343 |

0.556 |

0.728 |

0.482 |

|

FSE4 |

0.501 |

0.582 |

0.845 |

0.609 |

|

FSE5 |

0.410 |

0.440 |

0.788 |

0.527 |

|

FWB1 |

0.411 |

0.401 |

0.521 |

0.736 |

|

FWB2 |

0.503 |

0.600 |

0.661 |

0.843 |

|

FWB4 |

0.411 |

0.507 |

0.613 |

0.817 |

|

FWB5 |

0.422 |

0.451 |

0.501 |

0.742 |

|

FWB6 |

0.289 |

0.324 |

0.374 |

0.604 |

Note. PLS-SEM results.

5.2.2 Assessment of higher order reflective constructs (HOC)

The precursor to the second stage, the latent score of the lower-order construct (LOC) associated with financial capability, was included in the dataset. The two latent variables, financial inclusion and literacy, were indicators of higher-order construct (HOC) financial capabilities in the second stage. Reliability and validity were assessed for the second-order construct’s financial ability. Consistency, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity were tested through Cronbach’s alpha, item loading, composite reliability, and AVE. Loading exceeds 0.708, VIF is less than 3, Cronbach’s alpha is greater than 0.7, and AVE is more than 0.5, which confirms the reliability and validity of the higher order construct (HOC), financial capability based on the latent score of the lower order constructed. The detailed results are reported below in Table 7 and Figure 4.

Table 7

Higher Order Construct Reliability and Validity (PLS-SEM Results)

|

Construct |

Item |

Loading |

VIF |

Cronbach’s |

CR |

CR |

AVE |

|

Financial Capabilities |

FI |

0.892 |

1.741 |

0.790 |

0.806 |

0.904 |

0.825 |

|

FL |

0.925 |

1.741 |

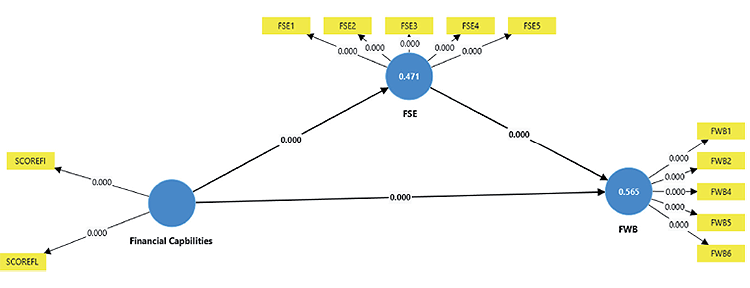

Figure 4

Measurement Model (Smart PLS)

Two measures were undertaken to test the discriminant validity of the higher-order construct (HOC) financial capabilities. Firstly, Fornell-Larcker criteria were used to compare the square root of each construct’s Average Variance explained (AVE) with the correlation between the constructs. The square root of AVE for each construct exceeds its corresponding construct correlation, satisfying the discriminant validity. Furthermore, HTMT values below the threshold criteria 0.9 confirm the discriminant validity. This analysis confirms that higher-order constructs maintained distinctiveness from other constructs and confirms the discriminant validity.

Table 8

Discriminant Validity Regarding Higher Order Construct ( PLS-SEM Results)

|

Constructs |

FSE |

FWB |

Financial capabilities |

|

HTMT criteria |

|||

|

Financial capabilities |

0.831 |

0.792 |

|

|

FornellLarcker criteria |

|||

|

Financial capabilities |

0.686 |

0.646 |

|

|

Cross Loadings |

|||

|

FI |

0.553 |

0.548 |

0.892 |

|

FL |

0.684 |

0.620 |

0.925 |

5.3 Structural Model Assessment

The PLS path model shown in Figure 4 helps to elucidate the direct influence between the specified constructs and helps in understanding the direct impact of financial capability on well-being and the mediating role of financial self-efficacy in this relationship. This section comprises the model’s predictive relevance, validity, and direct and indirect effects.

5.3.1 Predictive Relevance and Validity

Henseler et al. (2012) stated that R2 helps to assess the model’s predictive validity. Financial self-efficacy (FSE) has an R2 of 0.471, indicating that approximately 46.9% of variations in FSE are explained by its antecedent variables, financial capabilities based on financial literacy and inclusion. Financial well-being (FWB) has an R2 of 0.565, indicating that about 56.5% of variations in well-being were explained by financial capabilities and self-efficacy. Model fit indices were also considered to ensure model fitness. SRMR (Standardised Root Mean Square Residual) is 0.070, below the threshold requirement of 0.10, indicating a good fit. Meanwhile, an NFI (Normed Fit Index) of 0.832 indicates an acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Predictive relevance was tested through Q2. For both endogenous constructs, Q2 is above 0.15, which supports the model’s predictive relevance, as presented in Table 9.

Table 9

Relevance and Validity (PLS-SEM Results)

|

Latent |

Q 2 |

RMSE |

R 2 |

Adjusted R2 |

|

FSE |

0.460 |

0.743 |

0.471 |

0.469 |

|

FWB |

0.409 |

0.775 |

0.565 |

0.561 |

5.3.2 Direct effect and effect size

A 5000-sample bootstrapping was used to validate the measurement model, which includes the reflective higher-order construct financial capability. The statistics in Table 10 indicate that the hypothesis based on direct paths was accepted when the p-value was less than 0.05. The path coefficient (β) indicates the strength of influence of a particular antecedent on its subsequent endogenous variables. The statistics reported in Figure 5 and Table 10 suggest that financial capabilities have a higher influence on financial self-efficacy, with a β of 0.686, compared to financial well-being, whose β stands at 0.282. Financial self-efficacy significantly influences well-being, as suggested by β value 0.529.

Moreover, the effect size (f2) reported in Table 10 is indicated by measures of the influence of predictor constraints on the endogenous variables. The f2 of financial capabilities on financial well-being stands at 0.097, which is considered a small effect. In contrast, the f2 of financial capabilities on financial well-being is 0.890, which signifies a significant impact. The effect of self-efficacy on the financial well-being of 0.341 represents a moderate effect.

Figure 5

PLS Path Model (Smart PLS)

5.3.3 Indirect and Mediation effect

Financial capabilities have a significant indirect influence on financial well-being mediated by financial self-efficacy as defined by path coefficient (β) 0.363, t value 6.056, and the p-value 0.000 indicated in Table 10.

VAF (Variance Accounted for) was calculated using indirect effect/total effect to test the mediation effect. Here, the direct effect is 0.282, and the indirect effect is 0.363 (0.686* 0.529). Total effect is the combination of both direct and indirect effects. Here, VAF is 0.562 or 56.2, indicating that financial self-efficacy partially mediates the path FC<FSE<FWB.

Table 10

Direct, Indirect Effect and Effect Size

|

Hypothesis |

Path |

Beta |

Sample |

S. D |

T |

VIF |

P value |

F2 |

Decision |

|

Direct Effects |

|||||||||

|

H1 |

FC - > FWB |

0.282 |

0.279 |

0.074 |

3.796 |

1.890 |

0.0000 |

0.097 |

Accepted |

|

H2 |

FC- > FSE |

0.686 |

0.687 |

0.052 |

13.170 |

1.000 |

0.0000 |

0.890 |

Accepted |

|

H3 |

FSE - > FWB |

0.529 |

0.534 |

0.070 |

7.577 |

1.890 |

0.0000 |

0.341 |

Accepted |

|

Indirect Effects |

|||||||||

|

H4 |

FL - > FSE - > FWB |

0.363 |

0.367 |

0.060 |

6.056 |

0.0000 |

Accepted |

||

Note. Based on PLS-SEM results.

5.3.4 Predictive Relevance and Validity

Henseler et al. (2012) stated that R2 helps to assess the model’s predictive validity. Financial self-efficacy (FSE) has an R2 of 0.471, indicating that approximately 46.9% of variations in FSE are explained by its antecedent variables, financial capabilities based on financial literacy and inclusion. Financial well-being (FWB) has an R2 of 0.565, indicating that about 56.5% of variations in well-being were explained by financial capabilities and self-efficacy. Model fit indices were also considered to ensure model fitness. SRMR (Standardised Root Mean Square Residual) is 0.070, below the threshold requirement of 0.10, indicating a good fit. Meanwhile, an NFI (Normed Fit Index) of 0.832 indicates an acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Predictive relevance was tested through Q2. For both endogenous constructs, Q2 is above 0.15, which supports the model’s predictive relevance, as presented in Table 11.

Table 11

Relevance and Validity (PLS-SEM Results)

|

Latent |

Q 2 |

RMSE |

R 2 |

Adjusted R2 |

|

FSE |

0.460 |

0.743 |

0.471 |

0.469 |

|

FWB |

0.409 |

0.775 |

0.565 |

0.561 |

6. Findings and Discussion

Existing studies have extensively examined financial inclusion and literacy in isolation as enablers of better financial outcomes. Still, these studies had limited focus on the combined influence of financial capabilities and the role of financial efficacy, which implies an individual’s confidence in managing financial affairs and strengthening associations. This work bridges this gap by focusing on financial capabilities and efficacy as a mediator in the association.

The study’s results illustrate that financial capabilities significantly influence well-being in the context of working women. Inclusion and literacy are two vital dimensions of financial capabilities that contribute to promoting the financial well-being of working women. Similarly, financial self-efficacy has a positive significant influence on financial well-being. Findings are based on the capabilities theory, which implies that mere access to resources is not enough to secure well-being until women can utilise them properly (Sean, 1985). Results depict that resources and agency/ ability to act contribute to women’s long-term financial wellness, which supports the theory’s results. This means that along with literacy and inclusion in the financial system, women need appropriate confidence in their abilities to ensure their well-being and the attainment of financial goals. Results report that financial efficacy improves women’s confidence in their ability to handle the financial actions well, contributing to their financial independence and producing better financial outcomes. It acts as a psychological facilitator for transforming capabilities into desired well-being. This work offers fresh insights that emphasize that mere possessing of financial information and resources is not enough to attain the long-term financial wellness unless they have adequate confidence and belief in their capability to handle the financial affairs. The findings align with the results reported in the existing studies conducted by Ariati et al. (2023), Bojuwon et al. (2023), Lone and Bhat (2022) and Obenza et al. (2024). This perspective is in line with behavioural finance studies, which imply that mere knowledge and access are insufficient. Confidence and belief in their abilities are vital for securing better financial outcomes. The results are in line with Rahman et al. (2021), Lone and Bhat (2022) and Rashid et al. (2022), which show that literacy and inclusion drive financial well-being. The study findings of Rahman et al. (2021) showed that financial literacy equips individuals with the knowledge and skills to make informed decisions. Understanding the concepts of saving, investment, account opening, and others allows individuals to manage their finances adequately (Philippas & Avdoulas, 2020). Financially literate individuals are more likely to save, invest, and budget wisely. The literate individual takes advantage of growth opportunities that lead to wealth accumulation and financial security (Kiplangat et al., 2023). Financial inclusion ensures individuals’ access towards affordable products and services like banks, insurance, and credits. This access helps them manage their financial affairs and protects them against financial risks (Rashid et al., 2022). Having access to financial services provides long-term financial securities to the individuals and enables them to adequately manage their financial shocks.

Additionally, findings of this work show that a financial capability, which is largely mediated by the financial efficacy, has substantial and considerable influence on well-being. Women with confidence and belief in their abilities reported greater financial well-being. The results validate the findings indicated by Lone and Bhat (2022) and Ariati et al. (2023). Self-efficacy implies individual belief in their ability to attain a specific task. In the context of financial well-being, it represents how confidently women manage their finances to achieve their financial goals. This implies that boosting women’s confidence is one of the vital elements to promote their financial security. By enhancing their confidence level, individuals are more likely to apply their knowledge and skills and utilize financial services to attain financial well-being (Bojuwon et al., 2023). An individual’s confidence in managing the financial affairs is boosted by the financial literacy. To secure their financial stability in future, these people are more likely to pursue the financial planning.

6.1 Theoretical Contribution

Focusing on the mediating role of financial efficacy, this work provides novel insights about the financial capabilities of working women and how they affect their financial well-being. First and foremost, this work primarily focuses on female workers, who are often underrepresented in terms of their abilities and financial well-being, particularly in context of developing countries like India, as they lack opportunities, accessibility to markets, or encounter barriers to education and excessive pressure of care giving work at home as stated by Bau et al. (2022) and Biswas and Banu (2023). Secondly, this study provides more conceptual clarity by operationalizing and validating the financial capability as a reflective higher-order construct (HOC) comprising two dimensions using the variance-based SEM technique. This work established a direct linkage between financial capability (access to and ability to manage financial resources) and financial well-being. It enhances the theoretical understanding by validating the influence of financial skill and knowledge on the financial situation of working women. This nuanced understanding ensures the accurate measurement of financial capabilities. Thirdly, this study examines the mediating influence of financial self-efficacy on the relationship between capabilities and well-being and deepens the understanding of how confidence in managing financial affairs influences financial health. The introduction of the psychological component in the disclosure of financial well-being indicates that confidence in own abilities influences the effectiveness of financial well-being outcomes.

6.2 Practical Implications

By focusing on underserved sections of society, this study provides unique insights related to barriers and obstacles faced by women in the workforce. Women in the workforce often face unique challenges, such as the wage gap, discrimination, undue burden of unpaid care work, and others. The findings can inform multiple stakeholders, policymakers, government officials, educators, employers, and organizations that aim to promote gender equity in the financial dimension. Policies and programs should be tailored to contribute to financial knowledge and inclusion and to boost women’s confidence in making effective decisions. Results underscore the need for tailoring financial education programs specifically for working women to impart financial knowledge, foster confidence in making effective decisions, and address their unique needs and challenges. More focus should be given to promoting practical skills among women, such as debt management, investment in the stock market, mutual funds, budgeting, etc. Employers should organize programs that provide the possibility for the women workers to improve their financial knowledge, organize one-on-one financial counselling, and provide tools for adequate financial planning.

Financial efficacy development training initiatives should be undertaken along with financial literacy programs to ensure long-term financial wellness. These programs can help women employees to manage their finances adequately to improve their financial well-being and ensure women’s easy and broad access to a range of financial products. Policies should be framed to address the obstacles women face in entering the financial system, such as simplifying the account opening process, KYC norms, and low-cost financial products. Financial institutions should design products that can cater to the unique requirements of women workers, like creating investment products that provide more returns, flexibility, and security. More use of digital apps and platforms should be promoted to be easily accessible and user-friendly to help women manage their day-to-day financial affairs. Also, it is recommended to continuously evaluate financial program effectiveness using feedback forms from the women participants to make further improvements. Collectively, the practical implications of this study underscore the significance of more targeted policies and interventions in enhancing the financial well-being of working women.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This empirical work is limited to only working women. Hence, further research is needed to study other deprived and marginalized groups of society. Additional work within this area can be performed using a qualitative rather than a quantitative approach. Furthermore, longitudinal research can be conducted to understand the long-term influence of financial capabilities on financial well-being. This can help identify how financial literacy, inclusion, and confidence evolve and influence women’s financial stress management. This study is limited to the Delhi-NCR area of India. More research can be conducted on women’s financial well-being in other regions of India or different parts of the world. Cross-cultural studies can be performed to compare the financial capabilities across different socio-economic and demographic settings. Further research can examine the influence of digital financial services such as mobile banking, digital payment, and Fintech services such as AI, block chain, and machine learning in enhancing financial capabilities, especially for the underserved population. More work can be performed to evaluate the effectiveness of various financial education programs and interventions. Experimental research design can be used to assess which policy and program most effectively contributes to financial capabilities and leads to improved financial outcomes. Researchers can promote a comprehensive understanding of financial capabilities by addressing these future directions.

References

Ahmad, M., Yaser, A., & Hamshari, M. (2024). The impact of financial literacy on financial inclusion for financial well-being of youth : Evidence from Jordan. Discover Sustainability, 5, 528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00704-6

Al Rahahleh, N. (2023). Determinants of the Financial Capability: The Mediating role of Financial Self-efficacy and Financial Inclusion. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 13(6), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijefi.14531

Alemu, A., Woltamo, T., &Abuto, A. (2022). Determinants of women participation in income generating activities: Evidence from Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 11(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-022-00260-1

Allmark, P., &Machaczek, K. (2015). Financial capability, health and disability. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1589-5

Arafat, N., & Leon, F. M. (2020). The Effect of Self-Efficacy Financial Mediation on Factors Affecting Financial Inclusion in Small Businesses in West Jakarta. JurnalEkonomi : Journal of Economic, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.47007/jeko.v11i1.2910

Ariati, Y., Dharma Buchdadi, A., &Gurendrawati, E. (2023). Financial Literacy and Family Financial Socialization: Study of Its Impact on Financial Well-Being as Mediated by Financial Self-Efficacy. The International Journal of Social Sciences World, 5(2), 123–140. https://www.growingscholar.org/journal/index.php/

Bandaru, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Barik, R., & Lenka, S. K. (2022). Demand-Side and Supply-Side Determinants of Financial Inclusion in Indian States: Evidence from Post-Liberalization Period. Emerging Economy Studies, 8(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/23949015231207926

Bau, N., Khanna, G., Low, C., Shah, M., Sharmin, S., &Voena, A. (2022). Women’s well-being during a pandemic and its containment. Journal of Development Economics, 156, 102839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102839

Bhatia, S., & Singh, S. (2024). Exploring financial well-being of working professionals in the Indian context. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 29(2), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-023-00215-x

Binsuwadan, J., Elhaj, M., Bousrih, J., Mabrouk, F., &Alofaysan, H. (2024). The Relationship between Financial Inclusion and Women’s Financial Worries: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 16(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/su16198317

Birkenmaier, J. M., Sherraden, M. S., & Curley, J. C. (2010). Financial Capability: What is It, and How Can It Be Created? (CSD Working Paper No. 10-17). St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for Social Development).

Biswas, B., & Banu, N. (2023). Economic empowerment of rural and urban women in India: A comparative analysis. Spatial Information Research, 31(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-022-00472-3

Bojuwon, M., Olaleye, B. R., &Ojebode, A. A. (2023). Financial Inclusion and Financial Condition: The Mediating Effect of Financial Self-efficacy and Financial Literacy. Vision, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629231166200

Brüggen, E. C., Hogreve, J., Holmlund, M., Kabadayi, S., &Löfgren, M. (2017). Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 79, 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.03.013

CFPB. (2017). Financial Well-Being Scale: Scale development technical report, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Chong, K. F., Sabri, M. F., Magli, A. S., Rahim, H. A., Mokhtar, N., & Othman, M. A. (2021). The Effects of Financial Literacy, Self-Efficacy and Self-Coping on Financial Behavior of Emerging Adults. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(3), 905–915. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no3.0905

Deshpande, A., & Kabeer, N. (2024). Norms that matter: Exploring the distribution of women’s work between income generation, expenditure-saving and unpaid domestic responsibilities in India. World Development, 174, 106435. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106435

DHS. (2021). National family health survey (NFHS-5) India 2019-21. The DH.S Program. https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-541.cfm

Farrell, L., Fry, T. R. L., &Risse, L. (2016). The significance of financial self-efficacy in explaining women’s personal finance behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology, 54, 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2015.07.001

Faul, F., Erdfelde, E., Land, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences FRANZ. Behaviour Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191.

Gerrans, P., Speelman, C., & Campitelli, G. (2014). The Relationship Between Personal Financial Wellness and Financial Wellbeing: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9358-z

Guo, B., & Huang, J. (2023). Financial Well-Being and Financial Capability among Low-Income Entrepreneurs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16030181

Gupta, P., Aggarwal, M., & Bamba, M. (2025). Exploring Financial Well-being of Working Women in the Indian Context. Agenda, 0(0), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2025.2452601

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., &Sarstedt, M. (2022). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publishing.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., &Ringle, C. M. (2019). The Results of PLS-SEM Article information. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24.

Handayati, P., Restuningdyah, N., Ratnawati, &Meldona. (2023). The Role of Self-efficacy and Financial Attitude to Financial Well-Being: Mediation of MSME Financial Behavior.In Proceedings of the BISTIC Business Innovation Sustainability and Technology International Conference (BISTIC 2022). Atlantis Press International BV. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-178-4_30

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. &Sarstedt, M. (2012). Using Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in Advertising Research: Basic Concepts and Recent Issues. In S. Okazaki (Ed.), Handbook of Research on International Advertising (pp. 252–276). Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham.

Henson, R. (2001). Understanding Internal Consistency Reliability Estimates: A Conceptual Primer on Coefficient Alpha. Measurement and Evalution in Counseling and Development,34(3), 177–189. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2002.12069034

Hoelzl, E., & Kapteyn, A. (2011). Financial Capability. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(4), 543–545. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.04.005

Hu, L. T., &Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, J., & Guo, B. (2020). The Financial Capability and Financial Well-Being of Low-Income Entrepreneurs.(CSD Research Brief No. 20-01). St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Center for Social Development.

Ibourk, A., &Amaghouss, J. (2014). Impact of migrant remittances on economic empowerment of women: A macroeconomic investigation. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 4(3), 597–611.

Johnson, E. E., &Sherraden, M. S. (2007). From Financial Literacy to Financial Capability among Youth. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 34(3), 119–145. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.15453/0191-5096.3276

Jordan, P. J., & Troth, A. C. (2020). Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Australian Journal of Management, 45(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871976

Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’ s Empowerment. Development and Change, 30, 435–464.

Kang, H. (2021). Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 18, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3352/JEEHP.2021.18.17

Karystin, Y., Suade, M., & Hartono, P. G. (2024). JurnalProaksi Financial Self-Efficacy and Financial Well-Being : Insights from Western Java University Students. JurnalProakshi, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.32534/jpk.v11i3.6245

Kempson, E., Finney, A., & Poppe, C. (2017). Financial Well-Being: A Conceptual Model and Preliminary Analysis. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.18737.68961

Khan, K. A., Çera, G., & Alves, S. R. P. (2022). Financial Capability As a Function of Financial Literacy, Financial Advice, and Financial Satisfaction. E a M: Ekonomie a Management, 25(1), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2022-1-009

Kiplangat, M. D., Tuwey, J., &Maket, L. (2023). Financial self – efficacy, Financial Literacy and Subjective Financial Well- being of University Staff in Kenya. International Journal of Finance and Accounting, 2(1), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.37284/ijfa.2.1.1595

Kock, N. (2017). Common Method Bias: A Full Collinearity Assessment Method for PLS-SEM. In H. Latan&R.Noonan (Eds.), Partial Least Squares Path Modeling(pp. 245–257). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3_11

Koekemoer, E., Olckers, C., &Schaap, P. (2023). The subjective career success of women: The role of personal resources. Frontiers in Psychology, 14(March), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1121989

Kumar, P., Pillai, R., Kumar, N., & Tabash, M. I. (2023). The interplay of skills, digital financial literacy, capability, and autonomy in financial decision making and well-being. Borsa Istanbul Review, 23(1), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2022.09.012

Kun, A., &Gadanecz, P. (2022). Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian Teachers. Current Psychology, 41(1), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00550-0

León, W. F. D., Chaparro, O. L. M., & Rojas, C. A. R. (2024). Development of a Battery for the Measurement of Financial Capabilities in Young People. Social Indicators Research, 172(3), 1041–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-024-03336-5

Lone, U. M., & Bhat, S. A. (2022). Impact of financial literacy on financial well-being: a mediational role of financial self-efficacy. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 0123456789. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-022-00183-8

Manda, D. K., &Mwakubo, S. (2014). Gender and economic development in Africa: An overview. Journal of African Economies, 23(1 SUPPL1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejt021