Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2025, vol. 16, no. 2(33), pp. 329–344 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2025.16.14

Distribution of Constitutional Funds and Rural Credit in Brazilian Midwest Region

Raysa Palheta Borges (corresponding author)

Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia (UFRA), Brazil

rayborg06@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-8266-4706

https://ror.org/02j71c790

Marcos Rodrigues

Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia (UFRA), Brazil

marcos.rodrigues.adm@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3879-6115

https://ror.org/02j71c790

Abstract. Access to credit in agriculture is an important mechanism for increasing farms’ technological level and productivity, while the Fundo Constitucional do Centro-Oeste (FCO) policy also includes a reduction in regional disparities. In this study, we aimed to investigate whether the FCO resources in rural credit are increasing access to rural credit by municipalities in the Brazilian Midwest region. This study covers a panel data of 467 municipalities from 1995 to 2022. To measure credit distribution, we employed inequality indices and an OLS regression to determine the main factors affecting credit demand. The results demonstrated a major concentration of resources, including FCO, in more developed regions where consolidated grain production is predominant. A slight tendency toward diffusing resources was observed, mainly in livestock production financial resources. Structural and institutional constraints in more backward municipalities are responsible for the huge gap in total credit obtained yearly, which the FCO policy is unable to completely surpass, limiting the fund’s intention to promote regional development. This study confirms that the FCO policy for the agricultural sector is market-oriented, funding mainly grains and cattle ranching, which occur more frequently in developed municipalities. We demonstrated that few changes have occurred to transform this pattern over the decades, reducing the effectiveness of this policy.

Keywords: credit constraints, inequality index, rural development, spatial data

Received: 24/6/2024. Accepted: 28/10/2025

Copyright © 2025 Raysa Palheta Borges, Marcos Rodrigues. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Increasing farmers’ access to financial markets is an important mechanism to stimulate technological adoption, increase productivity, and raise rural income. Rural credit is responsible for funding activities through coverage of production costs and stimulating investments, which improves rural household output and income (Kuhn & Bobojonov, 2023; Nadolnyak et al., 2017). This assertion is even more noticeable in developing countries, such as Brazil, where agriculture is a vital sector, as they are the most important grain, coffee, cotton, and cattle producers worldwide (Mueller & Mueller, 2016), largely contributing to economic growth (Muhongayire et al., 2013). Owing to constraints, credit access is often limited in less developed regions within a country, reducing farm investment, and consequently, its efficiency, establishing different patterns of development.

To support Brazilian agriculture, an official rural credit policy was established in the 1960s through the National System of rural credit (Sistema Nacional de Crédito Rural, SNCR). This policy was based on government subsidies to lower interest rates, providing an attractive financial source for farmers to improve agricultural systems, which were technologically outdated. However, with the deterioration of Brazil’s government budget, this policy was redesigned in the 1990s, reducing the participation of public resources and stimulating market-oriented policy (Belik & Paulillo, 2009). This shift largely increased the total resources available in rural credit yet favored the disparity between municipalities by offering more means of obtaining financial resources in regions where agriculture is consolidated and introducing more constraints to those that are most backward in terms of technology and productivity.

Rural credit in Brazil is funded from several sources, including agricultural credit bills, bank deposits, and rural saving accounts, which are responsible for a large part of the total available resources annually, and are complemented by governmental sources, generally aiming for lower special conditions and/or promoting social and productive changes. The Constitutional Funds, created by the Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil in 1988, are the governmental sources aiming to develop the most backward Brazilian regions through the funding of productive and sustainable activities, both urban and rural, reducing inter- and intra-regional economic inequalities (Oliveira et al., 2019). The resources of the Constitutional Funds mainly originate from federal taxes on Industrialized Products (IPI) and income (IR) (Filgueiras et al., 2017) and are rated between three main Constitutional Funds: i) to the Northeast region (FNE); ii) to the North region (FNO) and iii) to the Midwest region (FCO; In English: Mid-West Constitutional Funds).

The Brazilian Midwest region consists of three states (Goiás, Mato Grosso, and Mato Grosso do Sul) and Distrito Federal. It has comprised the most productive agricultural frontier in the last decade, highlighting soybean, maize, cotton as crop production, and cattle, chicken, and pig in livestock activities. The FCO resources are destined to fund activities in municipalities in this region and are managed by the Banco do Brasil S.A., according to priorities established in the National Regional Development Policy (PNDR) formulated by the Ministry of Integration and Regional Development and Midwest Development Superintendence (SUDECO). These priorities aim to promote sustainable activities, the expansion, modernization, and diversification of the region’s economic base, and strengthening of local strategic arrangements.

Previous studies have pointed out that Constitutional Funds contribute to an increase in total output, wages, and employment in funded regions (Oliveira et al., 2018, 2019; Resende, 2014; Ribeiro et al., 2020); however, their results showed that the effects are more evident in developed municipalities. Lopes et al. (2021) analyzed recent changes in PNDR and pointed out that the funds are being market-oriented to short-term instead of long-term regional development projects. However, there is a notable gap in the analysis of rural credit distribution, particularly regarding resources allocated through policies aimed at fostering regional development.

Here we question whether the resources from the FCO policy are equitably distributed among municipalities or whether there is a concentration of resources in certain spatially clustered activities, thereby restricting the development of other regions. To address this issue, we aimed to investigate whether the FCO policy, designed to mitigate regional disparities through agricultural financial resources, effectively enhances credit access in Brazilian Midwest municipalities. Our findings were derived from the application of inequality indices and spatial data analyses. Furthermore, we estimate the primary factors influencing the demand for rural credit in Brazilian Midwest municipalities.

2. Data and Methods

2.1 Data

This study employed data from 467 municipalities in the states of Brazilian Midwest region (Distrito Federal, Goiás, Mato Grosso, and Mato Grosso do Sul). Data on Brazilian Official Rural credit were obtained from the Brazilian Central Bank (Central Bank of Brazil, 2023). The resources available to rural credit have multiple origins, and to measure how Constitutional Funds influence the distribution of resources, we grouped them into two categories: a) FCO: contracts that originate from the FCO resources; b) other sources of credit: all other contracts that do not have Constitutional Funds as sources of credit. We classified the credit into two categories according to the activities: i. Crop production, consisting of all temporary and permanent vegetal production; ii. Livestock production, for animal-based activities. Data on the number of rural households and agricultural area were used as weights for inequality measures and were obtained from the 1995, 2006, and 2017 Brazilian Agricultural Census (IBGE, 1996, 2006, 2017). The data of the forest area was obtained from the maps of land-use and land-cover of Mapbiomas database (Mapbiomas, 2025). Due to limitations of Brazilian Agricultural Census data, the number of rural households and agricultural areas between 2018 and 2022 is not available. Variables in the Brazilian currency were adjusted using the IGP-DI index from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation to the 2022 base rate.

2.2 Inequality Measures

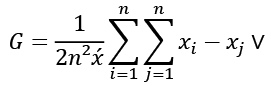

To verify whether the resources of FCO contribute to the spread of rural credit throughout the Midwest region municipalities, two indicators of inequality were employed: a) The Gini Coefficient (Hoffmann et al., 2019); b) Theil’s T (Cowell, 2011). Considering that agricultural production is heterogeneous in the Midwest territory, we also considered three different weights for each inequality indicator: i) equally distributed between municipalities, ii) weighted by the municipality share in agricultural area, and iii) weighted by the municipality share in the number of farms. Rural credit is an individual (farmer) decision, the aggregate value at municipality level is the sum of each individual decision (Castro & Teixeira, 2012) and therefore is influenced by the number of borrowers –farms– (Hartarska et al., 2015) and extent of agricultural production (area). The Gini Coefficient (G) is an inequality measure of the extent of deviation from the perfect distribution of resources among all municipalities (Bowles & Carlin, 2020; Cowell, 2011) expressed as

(1)

(1)

where G is the Gini coefficient; n represents the sample size (municipalities); x is the value of rural credit, for each i municipality in the Midwest region. The Gini coefficient ranges from zero (perfect distribution), where all individuals (municipalities) share an equal amount of the variable x, to one, where a single municipality holds all resources measured by x.

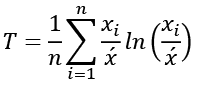

The Theil index (T) has origin in the concept of redundancy, which is the subtraction of actual entropy of the variable x from the maximum possible value of the entropy (Equation 2). Like the Gini Coefficient, the lowest value of T is zero, where all municipalities share the same amount of rural credit. However, the maximum value, where one municipality captures all resources in rural credit, is dependent on sample size and is represented by lnn.

(2)

(2)

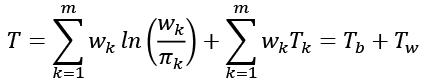

One advantage of the T index is that it can be decomposed to between-group (Tb) and within-group (Tw) inequality, considering the possibility of splitting the municipalities into groups and subgroups (Equation 3).

(3)

(3)

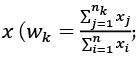

In Equation 3, wk is the share of group k in the total of variable  πk is the share of municipalities in group k in the total population

πk is the share of municipalities in group k in the total population  Tk is the Theil index (Equation 2) calculated for each group k. In this study, the groups were the states in Midwest Brazil.

Tk is the Theil index (Equation 2) calculated for each group k. In this study, the groups were the states in Midwest Brazil.

2.3 Spatial Data Analysis

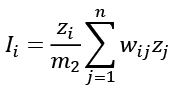

While inequality measures identify the degree of rural credit concentration between municipalities, Spatial Data Analysis (SDA) methods detect geographical clusters, outliers, and groups according to the spatial dependence between neighboring municipalities. Global Moran’s I (Equation 4) analyzes all municipalities simultaneously to determine whether the analyzed variable has a random spatial distribution (Lloyd, 2010). When Moran’s I is positive, there is evidence of spatial autocorrelation, with clusters of high–high or low–low neighboring municipalities. A negative Moran’s I indicates a pattern of high-low or low-high clusters (Xiong et al., 2022).

(4)

(4)

where wij is the weight assigned to municipality i in relation to its distance from municipality j; zi is the difference between the observed value of the variable and its mean; s0 is the sum of all wij weights. The weight matrix W was obtained using the queen methodology, in which any municipality that has at least one point in common to its neighborhood is assigned the value 1, while the others that do not have any surrounding border or point have a value of 0 (Silva et al., 2022).

Although Moran’s I indicates spatial autocorrelation, regional patterns and clusters can still be present between municipalities. The Local Indicator of Spatial Association (LISA), or Local Moran’s I, was proposed by Anselin (1995) to verify noteworthy cluster spots (Equation 5).

(5)

(5)

where  LISA values can be applied to a Moran scatterplot to identify four spatial autocorrelation patterns (clusters) between the municipality and its bordering neighbors: High-High; High-Low; Low-High; Low-Low.

LISA values can be applied to a Moran scatterplot to identify four spatial autocorrelation patterns (clusters) between the municipality and its bordering neighbors: High-High; High-Low; Low-High; Low-Low.

2.4 Econometric Approach

To investigate the main factors affecting the demand for rural credit in municipalities of Midwest region, we estimated an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) with panel data (Equation 6). The Hausman test was employed to decide between the random and fixed effects models, and we used the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation for the variables of panel model, interpreting the coefficients as elasticities, given the reduced presence of zeros (Bellemare & Wichman, 2020).

Yt = α + Xitβ + ϵit (6)

where Yt is the dependent variable, Xt is the matrix of independent variables and its β coefficients, and ϵ is the error term. Given the nature of the panel data and number of cross-sections (municipalities), we estimated the robust standard errors of coefficients to address heteroskedasticity and serial correlation.

The independent variables are the agricultural production value (APV) and the agricultural gross domestic product per capita (AGDPpc), both in thousands of Brazilian currency; the number of rural households (FARMS); the area of preserved forest (FOREST), pastureland (PASTURE), and crop production (CROP), all expressed in km². We have also added a dichotomous variable (D) that has a value of 1 in municipalities with presence of bank branches.

3. Results

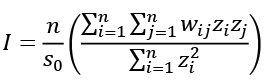

The total rural credit obtained by municipalities in the mid-west region increased from 12.18 billion (in Brazilian currency, 2012 prices) to 95.74 billion in 2022, a mean increase of 7.9% per year in the period (Figure 1). Goiás obtained the largest share of rural credit in 1995 (40.0%), followed by Mato Grosso (35.0%). Since 2013, the positions inverted, and Mato Grosso has the largest share of rural credit yearly, although, between states, the relative distribution did not significantly change, with Mato Grosso owning 39.5% of total credit in 2022, followed by Goiás (37.0%), Mato Grosso do Sul (23.1%) and Distrito Federal (0.4%).

Brazilian rural credit has origins in different sources and funds. FCO resources originate from fiscal funds and are destined for the Brazilian Midwest states. FCO resources grew from 1.289 billion in 1995 to 6.03 billion in 2022 (with a peak in 2019 at 11.85 billion). However, the relative participation of the FCO in total credit decreased over time, mainly because of the huge increase in credit supplied by other sources. During the 28 years analyzed, Goiás state contracted the largest share of FCO in 21 years, while Mato Grosso led for seven years. The structural change in the distribution of FCO resources among activities is noteworthy. In 1995, the crop production share was 21.0% (79.0% for livestock), which increased to 49.4% in 2022 (50.6% for livestock).

Figure 1

Evolution of Rural Credit in the Midwest Region of Brazil

Brazilian Midwest states are famous for their crop and livestock production, highlighting grain production, which has been expanding in the last decades, and cattle ranching. In 1995, the rural credit contracts to pay production costs in cattle ranching corresponded to 22.0% of total credit, while maize and soybean together represented 42.5% of total credit. This structure of concentration of credit in such activities remained over time, with funding costs in cattle ranching representing 33.2%, 29.5%, and 24.4% of total credit in 2006, 2017, and 2022, respectively. Maize and soybean contracts to pay production costs totaled 29.7%, 40.2%, and 43.8% in 2006, 2017, and 2022, respectively.

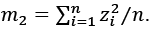

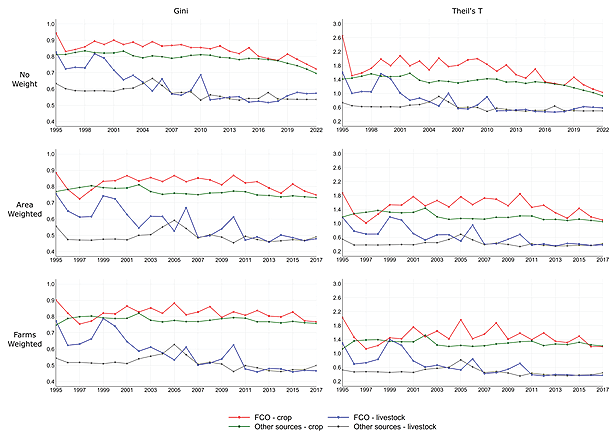

The distribution of rural credit resources among municipalities in the Brazilian Midwest is influenced by several variables. To measure the inequality in resource distribution, we employed the Gini coefficient and Theil T, subdivided into two groups: a) FCO resources, b) other credit sources, and a comparison of crop and livestock activities. Considering the structural differences between municipalities, we employed three different weightings and compared the results between 1995 and 2017. We used no weight for the period between 2018 and 2022 since no data of the number of rural households and farm area is available (Figure 2).

At first glance, rural credit resources (regardless of the sources and activities) showed a tendency to reduce concentration, even though it was small, with both the Gini coefficient and Theil T showing lower values in 2022 (and 2017 to weighted values) when compared to 1995. The other Sources of Credit showed more stability in concentration indices than FCO resources, which showed large fluctuations over the analyzed period.

Figure 2

Indices of Inequality

Note. No weight = we assume equal weighting between municipalities; Area = weighted according to each municipality’s share in total agricultural area; Farms = weighted according to each municipality’s share in rural properties.

Crop activities have a high concentration of credit. In 1995, only 24.6% of municipalities obtained crop FCO credit, whereas 10 municipalities contracted 64.7% FCO (Gini coefficient of 0.944). In 2022, the concentration decreased, rising to 79.9% the number of municipalities that obtained the Constitutional Fund resource, and the 10 first municipalities in credit ranking contracted 22.6% of the total crop FCO (Gini coefficient reduced to 0.723).

When weighing the total contracted resources by the share of the area and rural properties, the concentration does not vary significantly when compared to no weighting. The fluctuations in coefficients during the analyzed period are more related to sectorial and institutional changes than to shifts in concentration patterns. The results suggest that some municipalities with more developed agricultural sectors act as gravitational forces, capturing more resources while developing policies to spread credit struggle with such forces.

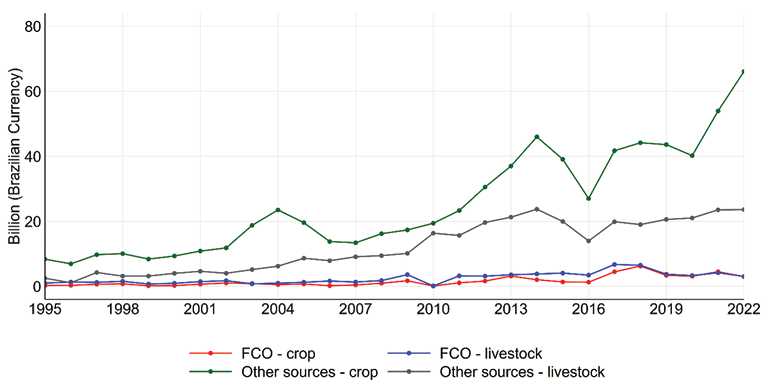

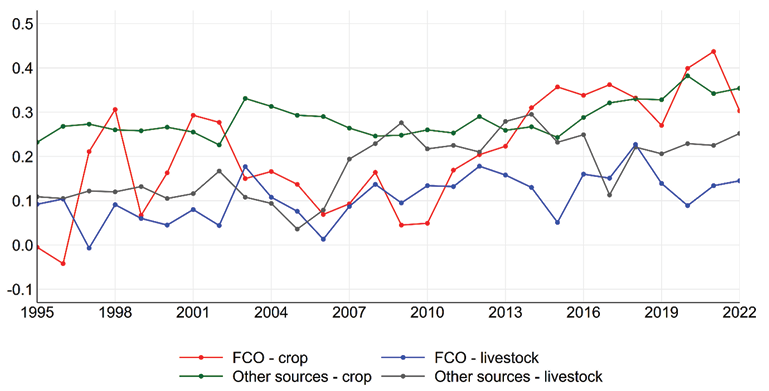

To test this gravitational force in some locations, we estimated the global Moran’s I (Figure 3). Spatial dependence in rural credit is expected, since some activities, mainly crop commodities (such as soybean, maize, and cotton) and cattle ranching, are highly demanding of capital and geographically concentrated in the Mid-west region –spatially dependent on industry or support sectors. Consequently, some high–high and low–high clusters of rural credit may appear in municipalities with these characteristics. Our results demonstrate a tendency of growth in the spatial concentration of credit between 1995 and 2022, with the crop production again showing higher values than the livestock sector, and the FCO resources presenting more fluctuation than other sources.

Figure 3

Global Moran’s I.

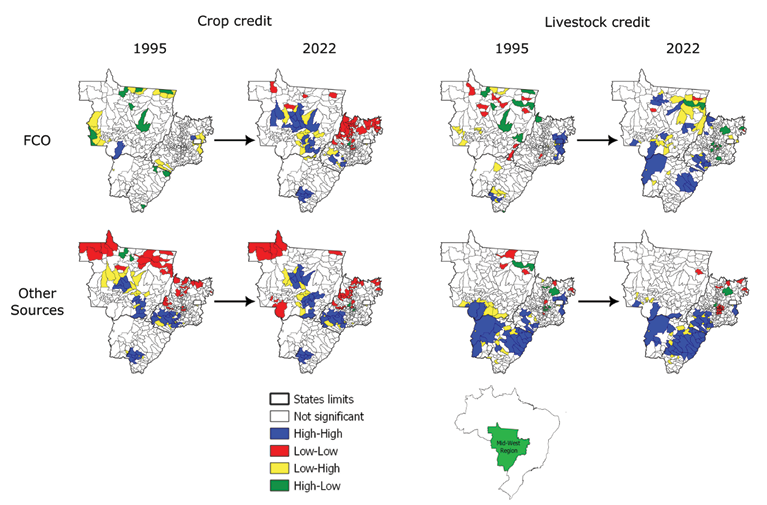

We estimated the LISA scores to analyze the spatial distribution of rural credit and the presence of clusters in the Midwest region of Brazil. The results demonstrated an increase in high-high municipality clusters for all credit sources between 1995 and 2022, especially for FCO funds in agriculture (Table 1). There is a noticeable shift in the spatial allocation of resources (regardless of source) in agricultural credit to the central region of Mato Grosso and Southern of Goiás and Mato Grosso do Sul (Figure 4), where grain production is predominant.

Table 1

Evolution of Municipalities in Each Cluster

|

Rural Credit Source |

Cluster |

1995 |

2004 |

2013 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

FCO: Crop |

High-High |

2 |

25 |

26 |

29 |

|

Low-Low |

0 |

33 |

81 |

44 |

|

|

Low-High |

25 |

27 |

18 |

21 |

|

|

High-Low |

9 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Not significant |

431 |

381 |

341 |

372 |

|

|

FCO: Livestock |

High-High |

11 |

25 |

28 |

26 |

|

Low-Low |

11 |

30 |

27 |

5 |

|

|

Low-High |

25 |

26 |

20 |

31 |

|

|

High-Low |

8 |

2 |

7 |

9 |

|

|

Not significant |

412 |

384 |

385 |

396 |

|

|

Other Sources: Crop |

High-High |

30 |

42 |

41 |

35 |

|

Low-Low |

32 |

53 |

59 |

39 |

|

|

Low-High |

27 |

17 |

17 |

17 |

|

|

High-Low |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

|

Not significant |

376 |

352 |

348 |

374 |

|

|

Other Sources: Livestock |

High-High |

33 |

23 |

46 |

42 |

|

Low-Low |

10 |

13 |

16 |

28 |

|

|

Low-High |

30 |

20 |

23 |

24 |

|

|

High-Low |

7 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

|

|

Not significant |

387 |

401 |

372 |

371 |

Figure 4

LISA Clusters to Rural Credit in Midwest Municipalities

The results of livestock production credit distribution show a different pattern from that of crop sources. The FNO shows a major high-high cluster east of Goiás in 1995 and isolated patterns over the Midwest region. In 2022, the spatial distribution of the FCO and other sources are similar, with two major high-high clusters, the first located in the west of Mato Grosso do Sul and south of Mato Grosso states, while the second is predominant in east of Mato Grosso do Sul and south of Goiás states. The inequality indexes and Global Moran’s I already demonstrated that livestock credit is less concentrated than resources obtained in the crop sector.

The low-low municipalities were predominant in the Goiás and Mato Grosso states, mainly in the peripheral areas. However, some municipalities stand out in such areas as high-low cluster, especially in the central Goiás state, indicating more influence in credit contracts in such regions. It is also observable that low-high municipalities are close to the high-high or high-low clusters in all cases, indicating that some constraints may interfere with the municipality’s capability to obtain FCO resources.

To determine the main factors affecting the municipality demand for credit, we estimated a panel data OLS (Eq. 6). We preferred the effects model considering the Hausman test results (chi-squared = 129.8, p-value < 0.05). The main results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

OLS Panel Data Estimates (Fixed Effects): Total Rural Credit as Dependent Variable

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

|

APV |

0.486 * |

0.050 |

|

AGDPpc |

0.490 * |

0.170 |

|

FARMS |

0.435 |

0.811 |

|

FOREST |

-1.319 * |

0.535 |

|

PASTURE |

0.080 |

0.720 |

|

CROP |

0.323 * |

0.048 |

|

D |

-0.008 |

0.097 |

|

R² |

0.394 |

Note. Robust standard errors are estimated to account for heteroscedasticity and serial correlation. * means significant at 5%.

The coefficients of OLS panel data are interpretable as elasticities. Therefore, a 1% increase in APV, AGDPpc or crop area would increase the total credit obtained in the municipality by 0.486%, 0.49% and 0.323%, respectively. The total coverage of forest area by its turn demonstrate an inverse relationship (elasticity of -1.319%), while the pasture area and the presence of agency branches do not have significant effects in credit contracts.

4. Discussion

The states of the Midwest region are prominent in the agricultural sector, with the largest effective cattle herd in Brazil, a high growth rate in recent years in pork and poultry production, and the largest production of grain, especially soybean and maize. Along with other productions, these activities are highly demanding of capital, and consequently, rural credit plays an important role in regional development (Pereira & Brisola, 2022; Rausch & Gibbs, 2016). Considering the large extension of this region, some areas have more favorable conditions for high capital-intensive agriculture, which supports local development, while some municipalities present lower development indices, requiring more public policy support.

FCO resources are funded by the government resources with origin in a share of federal taxes and have the main objective of developing economically backward municipalities in Midwest states (Resende, 2013). Therefore, it is expected that FCO resources will reduce the overall concentration of rural credit through the funding of less-favored municipalities. Comparing the inequality index results between 1995 and 2022, we demonstrated that this expectation is partial. FCO resources are concentrated in the areas with a predominance of more developed agriculture, whereas livestock credit is more equally distributed, reducing the effectiveness of this policy. An interesting fact at local scale is that the three municipalities (Rio Verde, Sorriso and Jataí) that obtained more credit resources during the entire analyzed period remained in the same rank position and gave grain production as their main activity.

The rural credit obtained by each municipality, yearly, is the sum of local farmers’ contracts, which are influenced by several variables (e.g., willingness to raise funds, production characteristics, access to the financial system, and existence of technical assistance). Our regression model results showed that the presence of bank branches does not have influence on total credit demand in municipalities, while the forest area, as a limiting factor of agriculture area expansion, reduces the volume of credit. Other structural factor variables, such as the available infrastructure and institutional constraints (limitations due to the forestry code, farm compliance with legal titling, and climate conditions for some crops) may reduce the capacity of some municipalities to raise funds for rural credit and were not tested in this study.

Therefore, an uneven distribution of credit is expected between municipalities affected by more constraints and those with highly developed agriculture. However, the weighted inequality index results show that some municipalities obtain more credit than their expected demand (share of the area and rural properties), which restrains the ability of rural credit to reach more municipalities.

When comparing the LISA high-high clusters in 2022, the FCO resources and other sources of rural credit show a similar pattern. The high-high clusters evidenced in rural credit are the main spots of grain production, which are mainly based on economies of scale, with high costs of production and investment in machines and production systems (Cacho, 2016; Rodrigues & Campos, 2019), or cattle ranching, which have higher costs associated with maintenance of the activity. The concentration coefficients, when weighed by the share of the area of each municipality, showed lower yet minor values than non-weighted indexes, demonstrating that other characteristics may influence credit demand, such as land tenure or spatial characteristics.

Municipalities with large farms cultivating grains and raising cattle demand more credit per area than other activities, and consequently also have a higher demand in credit contracts, acting as gravitational forces to rural credit; part of this demand is supplied by the FCO resources forming geographically evident clusters. The regression results confirmed that crop area is an important factor to increase demand of credit, especially in Brazilian Midwest states where the grain production is growing annually.

During the analyzed period, fluctuations were observed in the FCO inequality results and Moran’s I index, while the other sources of credit presented a stable trajectory. While the other sources of credit are subject to fluctuations mainly in the function of market conditions (sector expansion or crisis, interest rate) (Castro & Teixeira, 2012), the FCO resources are also dependent on several other variables–yearly fund available resources, distribution between rural and urban activities, priority areas selected by the fund management committee, guidance of development policies, and farmers’ demand, which explains the year-by-year instability of inequality measures in this fund. Frequently, the impact of such variables is more intense in small farms (Ely et al., 2019) which are more abundant in low-low clusters, while large farms (especially in high-high clusters with grain production) have more access to capital, technology, and assistance.

Agricultural Moran’s I increased positively during the same period, indicating a spatial concentration of credit. Oliveira et al. (2016) analyzed the FCO Rural resources in Goiás state between 2004 and 2011 and noticed that Moran’s I also had a growth trend in the period (shifting from 0.079 to 0.144), as well as the high-high clusters concentrated in the southern municipalities of this state. We observed that the livestock production Moran’s I and concentration indexes showed lower values, explainable by the wide distribution of this sector in the Midwest region, even though with a higher presence of cattle ranching in areas outside the grain production and in Mato Grosso do Sul state.

Some studies have already demonstrated that Brazilian Constitutional Funds have positive effects on income, wages, and employment (Oliveira et al., 2019; Resende et al., 2018); from a different perspective, Pereira et al. (2022) found slightly significant effects of the FCO funds in agricultural employment. Ribeiro et al. (2020) analyzed the impact of the Constitutional Fund in Northeast Brazil and concluded that the fund incentivized investments, increasing the GDP and reducing inequalities with other regions. Silva-Filho et al. (2023) estimated a Spatial Auto-Regressive Model and concluded that Brazilian Constitutional Funds have a positive impact –although minor and year-limited– on regional income. The role of Brazilian rural credit in increasing rural families’ income and farm productivity is evidenced by Neves et al. (2020), who estimate an unconditional quantile regression and income decomposition. On the other hand, studies have demonstrated that soybean production contributed to reducing poverty in regions that are frequently more developed than other locations (Weinhold et al., 2013).

In the econometric approach, the variables of agricultural production value (APV) and rural mean income (AGDPpc) are positively correlated with credit demand (Katuka et al., 2023). This relationship creates an escalating effect in regions with advanced agricultural production, where these variables are typically high, reinforcing the high demand for credit and leading to areas of spatial concentration. Policies must adapt to these realities to distribute resources more efficiently, attracting them from more developed locations to other areas that need these resources to stimulate local activities.

Funding agricultural activities contributes to farm output and income, surpassing local constraints in obtaining FCO. Reducing inequalities in contracted values may contribute to the fund objective in stimulating Brazilian Midwest region development. Since borrowing credit is farmers’ individual decision, policy implications to better distribute rural credit should stimulate the demand for financial resources, including direct actions, e.g., expanding the financial system network to more municipalities, and technical assistance; and indirect actions, such as infrastructure and logistics investments to increase the flow of inputs and outputs in municipalities.

5. Conclusion

This study analyzed the distribution of rural credit in the Brazilian Midwest region, with a major focus on the FCO resources. In summary, the results demonstrate that FCO resources are: i) poorly allocated between municipalities (throughout the analyzed period it was noted that the inequalities indexes remained at high rates); ii) the majority of resources are being directed to highly productive activities in agriculture, especially grain production; iii) there is spatial concentration of FCO on crop production in developed regions, while livestock production is more equally and spatially distributed. Some municipalities act as gravitational forces for rural credit, concentrating resources in each territory, which grows as high-high clusters over time.

The results show that the share of area and number of rural properties slightly reduces the inequality indices for rural credit, demonstrating that distribution of credit may be related with characteristics such as land tenure, agricultural production, and spatial distribution of farms. Future studies may check institutional and structural constraints that also may influence the capacity of some municipalities to obtain credit, such as legal restrictions to the advancement of agricultural areas, farm compliance with environmental laws, and climate conditions.

References

Anselin, L. (1995). Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geographical Analysis, 27(2), 93–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4632.1995.tb00338.x

Belik, W., & Paulillo, L. F. (2009). O Financiamento da produção agrícola brasileira na década de 90: ajustamento e seletividade. In S. P. Leite (Ed.), Políticas públicas e agricultura no Brasil (pp. 97–122). Editora da UFRGS.

Bellemare, M. F., & Wichman, C. J. (2020). Elasticities and the Inverse Hyperbolic Sine Transformation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 82(1), 50–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12325

Bowles, S., & Carlin, W. (2020). Inequality as experienced difference: A reformulation of the Gini coefficient. Economics Letters, 186, 108789. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2019.108789

Cacho, M. M. y T. G. (2016). Soybean agri-food systems dynamics and the diversity of farming styles on the agricultural frontier in Mato Grosso, Brazil. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 43(2), 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1016917

Castro, E. R., & Teixeira, E. C. (2012). Rural credit and agricultural supply in Brazil. Agricultural Economics, 43(3), 293–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2012.00583.x

Central Bank of Brazil. (2023). Rural Credit Data Matrix. https://www.bcb.gov.br

Cowell, F. A. (2011). Measuring Inequality (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Ely, R. A., Parfitt, R., Carraro, A., & Ribeiro, F. G. (2019). Rural credit and the time allocation of agricultural households: The case of PRONAF in Brazil. Review of Development Economics, 23(4), 1863–1890. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12606

Filgueiras, G. C., Bentes, E. dos S., Carvalho, A. C., Araújo, A. C. de S., & Oliveira, C. D. C. (2017). O papel do Fundo Constitucional de financiamento do Norte e do Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar para a região Norte do Brasil. Agroecossistemas, 9(1), 116–130.

Hartarska, V., Nadolnyak, D., & Shen, X. (2015). Agricultural credit and economic growth in rural areas. Agricultural Finance Review, 75(3), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-04-2015-0018

Hoffmann, R., Botassio, D. C., & Jesus, J. G. (2019). Distribuição de renda: medidas de desigualdade, pobreza, concentração, segregação e polarização (2nd ed.). Editora da USP.

IBGE. (1996). Censo Agropecuário 1995-1996. https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-agropecuario/censo-agropecuario-1995-1996

IBGE. (2006). Censo Agropecuário 2006. Segunda Apuração. https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-agropecuario/censo-agropecuario-2006/segunda-apuracao

IBGE. (2017). Censo Agropecuário 2017. Resultados Definitivos. https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-agropecuario/censo-agropecuario-2017

Katuka, B., Mudzingiri, C., & Vengesai, E. (2023). The effects of non-performing loans on bank stability and economic performance in Zimbabwe. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 13(6), 396–405.

Kuhn, L., & Bobojonov, I. (2023). The role of risk rationing in rural credit demand and uptake: lessons from Kyrgyzstan. Agricultural Finance Review, 83(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-04-2021-0039

Lloyd, C. D. (2010). Spatial Data Analysis: An introduction for GIS users. Oxford University Press Inc.

Lopes, G. C. L. de A., Macedo, F. C. de, & Monteiro Neto, A. (2021). Propostas recentes de mudanças nos fundos constitucionais de financiamento: em curso a desfiguração progressiva da Política Nacional de Desenvolvimento Regional (PNDR). Revista Brasileira de Gestão e Desenvolvimento Regional, 17(3), 398–410. https://doi.org/10.54399/rbgdr.v17i3.6302

Mapbiomas. (2025). MapBiomas Project - Collection 10 of the Annual Land Use Land Cover Maps of Brazil. https://brasil.mapbiomas.org/

Mueller, B., & Mueller, C. (2016). The political economy of the Brazilian model of agricultural development: Institutions versus sectoral policy. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 62, 12–20. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2016.07.012

Muhongayire, W., Hitayezu, P., Mbatia, O. L., & Mukoya-Wangia, S. M. (2013). Determinants of Farmers’ Participation in Formal Credit Markets in Rural Rwanda. Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 4(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/09766898.2013.11884706

Nadolnyak, D., Shen, X., & Hartarska, V. (2017). Farm income and output and lending by the farm credit system. Agricultural Finance Review, 77(1), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-03-2016-0020

Neves, M. de C. R., Freitas, C. O., Silva, F. de F., Costa, D. R. de M., & Braga, M. J. (2020). Does Access to Rural Credit Help Decrease Income Inequality in Brazil? Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 52(3), 440–460. https://doi.org/DOI: 10.1017/aae.2020.11

Oliveira, G. R., Lima, A. F. R., & Arriel, M. F. (2016). Fundo Constitucional de Financiamento do Centro-Oeste (FCO) em Goiás: Uma aplicação econométrica-espacial. Revista Brasileira de Economia de Empresas, 16(1), 7–23.

Oliveira, G. R., Menezes, R. T., & Resende, G. M. (2018). Dose response effect of the constitutional financing fund of middle west (FCO) in the Goias state. Nova Economia, 28(3), 965–1000.

Oliveira, G. R., Resende, G. M., Silva, D. F. C. da, & Gonçalves, C. N. (2019). Micro-impacts of the Brazilian Regional Development Funds: Does lending size matter? Review of Development Economics, 23(1), 293–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12539

Pereira, B. M., & Brisola, M. V. (2022). Techno-economic Evolution of Soybean Production in Brazil and Argentina. Journal of Agricultural Science, 14(8), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v14n8p145

Pereira, E. B., Souza, C. C. de, Frainer, D. M., & Silva, D. C. G. (2022). The Contribution of the Constitutional Financing Fund of the West Center of Brazil (FCO) in Generation of Employment. Desafio Online, 10(2), 386–407. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.55028/don.v10i2.12290

Rausch, L. L., & Gibbs, K. H. (2016). Property Arrangements and Soy Governance in the Brazilian State of Mato Grosso: Implications for Deforestation-Free Production. Land 5(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/land5020007

Resende, G. M. (2013). Regional development policy in brazil: a review of evaluation literature. Redes, 18(3), 202–225. https://doi.org/10.17058/redes.v18i3.3565

Resende, G. M. (2014). Measuring Micro- and Macro-Impacts of Regional Development Policies: The Case of the Northeast Regional Fund (FNE) Industrial Loans in Brazil, 2000–2006. Regional Studies, 48(4), 646–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.667872

Resende, G. M., Silva, D. F. C., & Silva Filho, L. A. (2018). Evaluation of the Brazilian regional development funds. Review of Regional Research, 38(2), 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-018-0123-5

Ribeiro, L. C. S., Caldas, R. M., Souza, K. B., Cardoso, D. F., & Domingues, E. P. (2020). Regional funding and regional inequalities in the Brazilian Northeast. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 12(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12230

Rodrigues, M., & Campos, I. (2019). Soybean cropping by family farmers: A new institutional path for rural development in Brazilian Central-West. Italian Review of Agricultural Economics, 74(22), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.13128/rea-10851

Silva, G. S. da, Amarante, P. A., & Amarante, J. C. A. (2022). Agricultural clusters and poverty in municipalities in the Northeast Region of Brazil: A spatial perspective. Journal of Rural Studies, 92, 189–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.03.024

Silva-Filho, L. A., Azzoni, C. R., Chagas, A. L. S., & Castro, G. (2023). Favorable credit to private agents and the local economies in the deprived regions of Brazil: A spatial panel analysis. Letters in Spatial and Resource Sciences, 16(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-023-00363-7

Weinhold, D., Killick, E., & Reis, E. J. (2013). Soybeans, poverty and inequality in the Brazilian Amazon. World Development, 52, 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.11.016

Xiong, N., Yang, X., Zhou, F., Wang, J., & Yue, D. (2022). Spatial distribution and influencing factors of litter in urban areas based on machine learning – A case study of Beijing. Waste Management, 142, 88–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2022.01.039