Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2025, vol. 16, no. 2(33), pp. 345–365 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2025.16.15

Investigation of Interplay of Meaning of Work, Job Pride, and Job Performance on Turnover Intention: Evidence from Millennial Bankers in Central Java, Indonesia

Masykur Lutfi Muttaqin (corresponding author)

Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

lutfi.muttaqin@student.uns.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-9530-9691

Sinto Sunaryo

Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia

sintosunaryo_fe@staff.uns.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1360-0238

Abstract. Retaining millennial employees in the workforce is a pressing challenge for organizations. Therefore, this research aimed to investigate the interconnections between the meaning of work, job pride, and job performance, and how job pride and job performance impacted turnover intention of millennials. Cross-sectional surveys of 250 banking employees in Central Java, Indonesia, collected through a multi-stage sampling procedure were used. In addition, Structural Equation Modeling-Partial Least Square (SEM-PLS) was used to analyze these associations. The results showed significant positive associations among the meaning of work, job pride, and job performance. However, results proposed that job pride and job performance did not negatively affect turnover intention. This research contributed valuable theoretical understanding of the concept of the meaning of work for millennials and offered practical implications for banking managers in human resource management.

Keywords: meaning of work, job performance, job pride, turnover intention, millennials, bank

Received: 11/10/2024. Accepted: 4/8/2025

Copyright © 2025 Masykur Lutfi Muttaqin, Sinto Sunaryo. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The concept of the meaning of work (MOW) is achieving scholarly attention in recent years (Grillo et al., 2021). The meaning of work has surfaced as an essential construct in the field of management research (You et al., 2021). Moreover, research is expanding, signifying that the meaning of work may offer a more enriching and satisfying work experience (Carton, 2018). The meaning of work is often prioritized over happiness and wealth, as it is tied to personal objectives and values (Soren & Ryff, 2023). This implies that work assists people to earn a living and also fulfil purpose. Meanwhile, young generations leave their jobs due to lack of interest (Caringal-Go & Hechanova, 2018).

The meaning of work is becoming increasingly important for the millennial generation, as it shapes the way they perceive and carry out their jobs (Malik & Malik, 2024). Understanding how the meaning of work contributes to the well-being and work experiences of this generation still requires further attention (Yap et al., 2022), indicating a significant research gap in the current literature. Therefore, organizations need to understand the deeper meaning and needs of employees to remain motivated (Charles-Leija et al., 2023), as the generation demands meaningful work, and when not met, employees may leave (K.-L. Tan et al., 2019). Different from earlier generations, millennials tend to place less importance on work as a central life priority, which often translates into lower levels of organizational loyalty (Park & Gursoy, 2012).

Cultivating job pride is equally crucial beyond the significance of the meaning of work. Job pride strengthens the self-esteem of employees and also catalyzes greater contributions (Van Doren et al., 2019). Pride is essentially connected to prosocial actions, as individuals are more likely to engage in such behaviors when accomplishments are associated with personal values (De Hooge & Van Osch, 2021). Consequently, higher levels of job pride are associated with lower turnover intention, as employees who take pride in work tend to value the reputation and benefits associated with organizational affiliation, thereby improving a stronger sense of identity and commitment (Le et al., 2023).

In response to ongoing demographic changes, it is necessary to study the job performance of young employees as they increasingly represent a significant portion of the workforce (Song et al., 2024). Given the importance of job performance in achieving organizational goals, identifying its determinants and consequences has long been a priority for scholars and human resource managers (Juyumaya et al., 2024). Although the relationship between job performance and turnover intention has been investigated extensively, there are still some uncertainties (Liu et al., 2024). One possible mechanism is that employees may experience satisfaction due to personal performance, which serves as a motivational factor for improved performance and reduced turnover intention (Wang et al., 2023).

For more than a century, turnover has been widely investigated, with several articles detailing the causes. Additionally, different theories and models have been developed to explain the phenomenon (Van Der Baan et al., 2025). Furthermore, Indonesia is known to experience a high rate of turnover from millennial employees (Frian & Mulyani, 2018). This generation dominates some of the largest banks in the country. At the same time, banking is an industry sector that is experiencing a loss of employees (Elian et al., 2020). Banking employees spend a lot of time, energy, and thoughts on work that requires full accuracy and caution. Employees often feel an imbalance between personal life and work risks and feel that job demands exceed individual expectations (Hasan et al., 2022).

This research will analyze the relationship between the meaning of work, job pride, and job performance on turnover intention among the millennial generation in Indonesia, specifically in the banking industry, which tends to have a high turnover rate. The study is important as managing and meeting employee expectations is crucial for the future of businesses, including the banking industry in Indonesia.

1. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

1.1 Social Identity Theory

Influential theory offers a comprehensive framework that combines individual and group psychological processes. Social identity theory has been widely applied to understand various organizational phenomena (Scheepers & Ellemers, 2019). According to the research conducted by Tajfel and Turner (1979), individual and group classification into socially constructed groupings are based on shared characteristics, such as institutional affiliation, age, gender, and religion. The reason for this theory was the identification of individuals in a social group who have significant influences on behaviors and attitudes.

The salience of personal and social identity varies with social context (Markowski & Serpe, 2025), because personal identity influences behavior when an individual is alone or with close friends. However, in a setting of peers, social identity could be more prominent. Research has proven that the salience of social identity is a significant predictor of prejudice and discrimination, hence reducing the salience of intergroup differences could limit prejudice (Kerins et al., 2022).

1.2 Meaning of Work (MOW)

The current research used the broad phrase “meaning of work” to include both “meaning” and “meaningfulness.” This suggests that the two terms are viewed as part of the same concept, namely how individuals perceive and attribute meaning to their work (Rosso et al., 2010). The meaning of work has been explained from the perspective of general beliefs about work to personal experiences and job significance (Lin et al., 2020). Based on its importance, work is seen as a central aspect of life, beyond just earning a living, and is considered crucial in daily life (Blustein, 2023). Following this context, the meaning of work can assist in connecting personal values with that of organization (Supanti & Butcher, 2019). This concept is particularly crucial for millennials, who actively seek jobs that offer meaning and purpose in life (Kodagoda & Deheragoda, 2021).

Additionally, research has considered the meaning of work to be associated with job pride, proposing that stronger sense of meaning is positively related to greater job pride (Le et al., 2023). It has been observed that employees with more responsibilities have the tendency to appreciate work and pursue accomplishments. The relationship between the meaning of work and job pride is further explained through the connection between pride and prosocial behavior. For instance, individuals are more inclined to participate in prosocial actions when considering personal work to be meaningful, contributing to a sense of fulfillment and accomplishment (Lin et al., 2020). Following this discussion and findings, the following hypothesis was proposed.

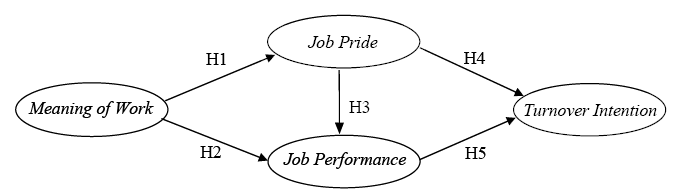

H1: The meaning of work positively affects job pride in millennials.

The meaning of work is also associated with job performance. In a research conducted by Giao et al. (2020), job performance reflects the ability of employees to complete tasks and achieve targets at a particular period. Therefore, improving a meaningful work environment by organizations is crucial particularly due to the positive correlation between the meaning of work and improved performance outcomes. In line with this research, Ahmed et al. (2022) proposed that managerial support for meaningful work can lead to increased organizational performance. This view is consistent with Setyaningrum et al. (2024), who stated that millennials are drawn to meaningful and challenging tasks, as the tasks assist in achieving ambitious career goals and also contribute to better performance. Following the discussion, Han et al. (2021) showed that meaning of work can improve job performance. According to these results, the research proposes the following hypothesis.

H2: The meaning of work positively affects job performance in millennials.

1.3 Job Pride (JP)

Although pride in the workplace has not yet received extensive scientific attention, this construct is considered an important factor for business success and also plays a central role in companies (Liao et al., 2023). This topic is defined as the self-esteem and positive self-image of employees concerning personal professional achievements or of others and membership in the organization the individual works (Ali et al., 2024). This attitude began to attract the interest of management scholars in the late 1990s and the 21st century (Durrah et al., 2021).

Job pride has been shown to have a positive and significant impact on performance (Hameed et al., 2019; Nadatien et al., 2019; Widyanti et al., 2020). Moreover, employees who feel pride are more inclined to show innovative behavior, as pride can encourage individuals to explore different strategies to reach higher personal achievements (Liao et al., 2023). One of the key factors in enhancing the innovative performance of millennial employees is promoting a sense of pride in their work (Zhang & Zhao, 2021). Based on the above, this research proposes the following hypothesis.

H3: Job pride positively affects job performance in millennials.

Job pride has been shown to have a negative relationship with turnover intention in addition to its connection with the meaning of work. Turnover intention is a psychological state that reflects the unhappiness of employees with the current role, combined with the desire, capability, and potential to find a different job (Mobley et al., 1978). Most millennials, particularly in Indonesia, are reluctant to have a long-term career at a single company because they value freedom and flexibility (Ardi & Anggraini, 2023).

Le et al. (2023) found that employees who are proud of the work are less expected to quit the jobs. This pride shows that employees strongly identify with the organization and feel a sense of achievement, believing that hard work contributes to the success of the organization (Ng et al., 2019). Pride is connected to the self-esteem of employees and causes employees to feel valued (Diwan et al., 2024). Therefore, pride includes a deep respect for emotional connection to the organization. This valuable psychological resource would be lost when employees decided to leave. Based on empirical evidence, the hypothesis is formulated as follows.

H4: Job pride negatively affects turnover intention in millennials.

1.4 Job Performance (JF)

According to Jianmin (2024), job performance refers to the actions employees display in the workplace along with the results generated from those actions. The performance of employees reflects both individual productivity and general organizational efficiency, contributing to long-term success (Hong & Zainal, 2024). In this context, organizations with a high number of millennial employees are advised to optimize their human resources in order to improve job performance (Indrayani et al., 2024).

Previous research consistently showed a negative correlation between job performance and turnover intention (Gun et al., 2021). Employees often experience essential satisfaction from work, viewing it as a motivating factor to improve performance and reduce the probability of leaving the organization. The results of Zimmerman and Darnold (2009) showed the healthy and complex nature of this relationship. Moreover, more recent research by Wang et al. (2023) confirms that job performance exerts a significant negative influence on turnover intention. In the light of the discussion of empirical evidence, this research formulates the following hypothesis.

H5: Job performance negatively affects turnover intention in millennials.

Figure 1

Conceptual Framework

2. Methodology

2.1 Sampling Method

The research sample consisted of 250 millennial employees working in the banking sector of Central Java Province. These employees were born between 1981 and 1996 (Owens et al., 2024; N. Tan et al., 2024), commonly referred to as Generation Y or Millennials, between the age of 27-42 years in 2023. The research used a multistage sampling for primary data collection. This process used probability sampling, starting with primary sampling units. From the primary units, a probability sample of secondary units was selected. Subsequently, a third stage of probability sampling was applied to the secondary units. This process was continued until the final stage, where a sample was collected from each member in the segmented units (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016).

The population for the research consisted of banking employees in Central Java Province, Indonesia, as cluster sampling was used to select 5 (five) cities in the province. The selected cities were Pemalang, Banyumas, Cilacap, Pati, and Batang Regencies. After selecting the cities, the research accessed Facebook groups consisting of banking employees in each city. Given that the research subjects were millennial banking employees, the questionnaire included an age verification question to ensure respondents met the criteria. Facebook was chosen for its reliable data and widespread use in professional and community communication in Indonesia (Patahuddin & Logan, 2019). To verify the authenticity of participants, Facebook’s real-name policy was used (Schneider & Harknett, 2022). Within those Facebook groups, members who met the criteria were randomly selected to serve as research samples.

To mitigate Common Method Variance (CMV) in the cross-sectional survey, preventive measures were applied based on Chang et al. (2010). First, the survey was conducted anonymously to reduce social desirability bias and encourage honest responses. Second, the question order was randomized to disrupt logical patterns between independent and dependent variables, minimizing systematic bias and enhancing data objectivity.

2.2 Measurement

The research scales were adapted from previous research, as the meaning of work was measured using a six-item questionnaire adapted from May et al. (2004), which assesses the meaningfulness of work. The instrument developed by May et al. (2004) was well-suited for measuring the meaning of work, as both concepts shared a common focus on how individuals understood and assigned meaning to their work, particularly in relation to personal significance, value, and life purpose. Job pride was assessed with a seven-item scale adapted from Guy (2014). Moreover, employees personally reported job performance using a five-item measure, similar to Shan et al. (2015). Turnover intention was measured with a five-item questionnaire adapted from Poddar and Madupalli (2012). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3. Data Analysis and Result

3.1 Demographic Analysis

Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the respondents relating to this research. The sample was nearly split between males (48%) and females (52%). Additionally, respondents ranged in age from 27 to 44 years, with a majority (52.4%) falling in the 27–31 age group. The majority (82.8%) held a bachelor’s degree, and in terms of work experience, nearly half (49.6%) of the respondents had less than 5 years in the current role.

Table 1

Demographic Information of the Respondents

|

Demographic variables |

Frequency |

% |

|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

120 |

48 |

|

Female |

130 |

52 |

|

Age |

||

|

27–31 |

131 |

52.4 |

|

32–36 |

64 |

25.6 |

|

37–41 |

33 |

13.2 |

|

42–44 |

22 |

8.8 |

|

Education |

||

|

High school |

21 |

8.4 |

|

Diploma 1 |

1 |

0.4 |

|

Diploma 3 |

8 |

3.2 |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

207 |

82.8 |

|

Master’s degree |

12 |

4.8 |

|

Doctoral degree |

1 |

0.4 |

|

Tenure |

||

|

<5 years |

124 |

49.6 |

|

6-10 years |

71 |

28.4 |

|

11-15 years |

40 |

16 |

|

>16 years |

15 |

6 |

3.2 Measurement Model Assessment

Table 2 shows convergent validity assessed through the loading factors, signifying that all items were above 0.60, except for indicator TI1 (0.399), which was subsequently removed from the model. Composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha values (α) were more than 0.60. Additionally, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all constructs was greater than 0.50, the specific criterion suggested by Hair (2019) for adequate convergent validity.

VIF values ranged from 1.463 to 4.243 (Table 2), all falling less than the commonly accepted threshold of 5.0 (Hair, 2019). These results showed that multicollinearity was not a significant issue in our partial least squares (PLS) model.

Table 2

Reliability and Validity of the Construct

|

Construct with items |

Loading factor |

VIF |

|---|---|---|

|

MOW α = 0.948; CR = 0.958; AVE = 0.794; mean = 4.188 |

||

|

(MOW 1) |

0.859 |

2.932 |

|

(MOW 2) |

0.904 |

4.243 |

|

(MOW 3) |

0.887 |

3.390 |

|

(MOW 4) |

0.907 |

4.376 |

|

(MOW 5) |

0.921 |

4.813 |

|

(MOW 6) |

0.865 |

3.194 |

|

JP α = 0.911; CR = 0.929; AVE = 0.653; mean = 4.180 |

||

|

(JP 1) |

0.805 |

2.330 |

|

(JP 2) |

0.866 |

3.107 |

|

(JP 3) |

0.860 |

2.824 |

|

(JP 4) |

0.687 |

1.672 |

|

(JP 5) |

0.779 |

2.054 |

|

(JP 6) |

0.802 |

2.266 |

|

(JP 7) |

0.843 |

2.595 |

|

JF α = 0.802; CR = 0.863; AVE = 0.558; mean = 4.201 |

||

|

(JF 1) |

0.770 |

1.606 |

|

(JF 2) |

0.755 |

1.565 |

|

(JF 3) |

0.678 |

1.463 |

|

(JF 4) |

0.767 |

1.570 |

|

(JF 5) |

0.760 |

1.559 |

|

TI α = 0.851; CR = 0.898; AVE = 0.690; mean = 2.635 |

||

|

(TI 1)* |

0.399 |

1.240 |

|

(TI 2) |

0.921 |

3.250 |

|

(TI 3) |

0.909 |

3.215 |

|

(TI 4) |

0.792 |

1.747 |

|

(TI 5) |

0.678 |

1.493 |

Note. *Below the minimum threshold. MOW = Meaning of Work; JP = Job Pride ; JF = Job Performance; TI = Turnover Intention.

This research also tested discriminant validity using heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) method described by Henseler et al. (2015). Table 3 shows HTMT results, which were all less than 0.90 threshold, signifying that discriminant validity between the two reflectively measured constructs had been achieved without issues.

Table 3

Discriminant Validity

|

Construct |

JF |

JP |

MOW |

TI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) |

||||

|

JF |

||||

|

JP |

0.868 |

|||

|

MOW |

0.826 |

0.865 |

||

|

TI |

0.314 |

0.293 |

0.345 |

|

Note. MOW = Meaning of Work; JP = Job Pride; JF = Job Performance; TI = Turnover Intention.

3.3 Structural Model Assessment

Table 4 shows the results of the assessment of the model fit to evaluate how well the estimated model corresponded to the observed data using PLS-SEM with standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Smaller SRMR values signify a better fit between the model and the data. Using SRMR of 0.060, the model showed a good fit, which is below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.080 (Hu & Bentler, 1998).

Table 4

Model Fit

|

Category |

Values |

|

SRMR |

0.060 |

|

NFI |

0.864 |

Note. SRMR = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual; NFI = Normed Fit Index.

Normed Fit Index (NFI) was used to evaluate the model fit in this investigation. NFI scores range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 showing a better fit (Hair, 2019). In this research, NFI of 0.864 recommended a reasonably good fit between the proposed model and the observed data.

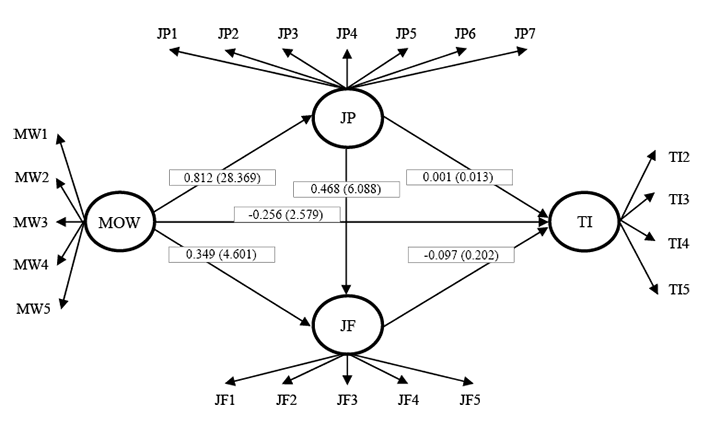

Bootstrapping method in SmartPLS 3.0 application was used to obtain t-statistics and p-values to determine whether the hypothesized paths in the research are significant enough to test the hypotheses. The correlation between variables was considered significant when the t-statistic was > 1.96 and p-values < 0.05. During this investigation, Figure 2 and Table 5 showed the hypotheses results.

3.4 Result of Hypotheses Testing

Figure 1

Path Analysis

Note. Beta (β) and t-values were shown along the arrows. MOW = Meaning of Work; JP = Job Pride; JF = Job Performance; TI = Turnover Intention.

The effect of the meaning of work on job pride was significant (β = 0.812, t-values = 28.369, p < 0.000), supporting H1. Subsequently, the meaning of work significantly affected job performance (β = 0.349, t-values = 4.601, p < 0.000), which supported H2. The effect of job pride on job performance was significant (β = 0.468, t-values = 6.088, p < 0.000), which supported H3. Job pride did not significantly affect turnover intention (β = 0.001, t-values = 0.013, p < 0.495), not supporting H4. Lastly, the effect of job performance on turnover intention was not significant (β = -0.097, t-values = 0.834, p < 0.202), which did not support H5. In conclusion, H1, H2, and H3 were supported, as H4 and H5 were rejected. Additionally, although the direct effect between the meaning of work and turnover intention was not part of the initial hypothesized model, an exploratory analysis was conducted after preliminary data patterns indicated a possible association between the two constructs. This additional test revealed a statistically significant negative relationship (β = –0.256, t-values = 2.579, p < 0.005).

Table 5

Path Coefficient

|

Hypothesized relationship |

Β |

t-values |

p-values |

Decision |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H1 |

MOW -> JP |

0.812 |

28.369 |

0.000 |

Supported |

|

H2 |

MOW -> JF |

0.349 |

4.601 |

0.000 |

Supported |

|

H3 |

JP -> JF |

0.468 |

6.088 |

0.000 |

Supported |

|

H4 |

JP -> TI |

0.001 |

0.013 |

0.495 |

Not Supported |

|

H5 |

JF -> TI |

-0.097 |

0.834 |

0.202 |

Not Supported |

Note. MOW = Meaning of Work; JP = Job Pride; JF = Job Performance; TI = Turnover Intention.

4. Discussion

The results of this research showed that the meaning of work positively affected job pride among millennials. The result was consistent with Le et al. (2023), stating that employees who considered work as important would dedicate more time and effort to jobs. Therefore, the perceived meaning of work by employees was an important factor in improving job pride, as it helped employees feel more connected to work and brought a sense that placing value and importance on work was essential (Lin et al., 2020). The meaning of work had a positive effect on job performance, consistent with Han et al. (2021), who explained that meaning of work improved job performance and the quality of work. This attitude has a significant impact on the behavior of employees, aiding employees to go beyond routine tasks, thereby improving performance. During this investigation, job pride had a positive effect on job performance. This result supported Hameed et al. (2019) and Widyanti et al. (2020), who indicated that job pride improved job performance. Employees who felt proud were expected to be motivated to work well. This showed that pride was about general positive feelings and also related to specific performance achievements and success (Buechner et al., 2019).

In this study, job pride did not demonstrate a significant negative relationship with turnover intention among millennials. Job pride assessed by participants had a high mean value, while turnover intention was moderate, indicating that high job pride did not prevent the desire to change jobs. This phenomenon could be attributed to Indonesia’s collectivism culture (Koentjaraningrat, 1974; Kurniati et al., 2020), which also characterizes the millennial generation in Indonesia (Hamdi et al., 2023). Similarly, Le et al. (2023) found that in collectivism cultures like Vietnam, job pride did not significantly influence turnover intention, as individuals in such societies are shaped by social and environmental factors (Yang et al., 2024). Millennials in collectivism cultures actively explore career opportunities for professional growth (Holtschlag et al., 2020). Career decisions are influenced not only by personal pride but also by social identity, family expectations, and group norms (Nipu, 2020). Additionally, significant career decisions tend to be made collectively, as individual choices are heavily influenced by important others (Jain, 2019). Consequently, rather than remaining loyal to a single organization, millennials prioritize career paths that suit their social networks and long-term aspirations, reinforcing the dynamic nature of turnover intention within this demographic.

Finally, job performance was not found to have a negative impact on turnover intention among millennials during the investigation. This result showed that good employee performance did not guarantee a reduction in the desire to leave the job. Well-performing employees are expected to leave their jobs due to their strong influence in the labor market (Zimmerman & Darnold, 2009), and the ease of movement resulting from the availability of alternative employment opportunities (Liu et al., 2024). Additionally, there could be a possibility that employees intended to leave, but the organization responded to the concerns of employees, such as low salaries or lack of meaningful work, keeping employees at the company.

4.1 Theoretical Implications

This study provided several contributions to the academic literature, particularly in the fields of human resource management, strategic management, and organizational behavior in emerging economies. The results showed no statistically significant effect while the initial hypothesis proposed that job pride and performance would reduce turnover intention. These results inspired a re-examination of prevailing assumptions, specifically in collectivism culture contexts and among millennial workers rather than weakening the theoretical foundation. The exploration of job pride was extended by this study beyond the traditional focus in the medical, hospitality and public services industry, with the relevance examined in the banking sector in a collectivism society and among millennials. The results proposed that the mechanisms might not have functioned as expected in collectivism cultures such as Indonesia, although job pride had often been associated with stronger organizational commitment and lower turnover intention (Pereira et al., 2021).

In such contexts, career decisions were influenced not only by personal pride in the work of an individual but also by social identity, family expectations, and group norms (Nipu, 2020). Emotional attachment to work was reflected in job pride but it had no direct influence on the decisions of employees to stay. The result implied that reducing turnover intention might not have been ensured by job pride alone. Therefore, it was thought that job pride should be reconceptualised beyond an individualistic perspective considering how employees were connected to broader social groups outside the workplace such as community or family, following the framework of Social Identity Theory by Tajfel and Turner (1979). The findings of this study also confirm the assertion of Le et al. (2023) regarding the crucial role of culture in shaping the relationship between job pride and turnover intention, while also affirming that the meaning of work consistently exerts a positive influence on job pride across diverse cultural contexts.

The non-significant effect of job performance on turnover intention did not imply that performance was unimportant but offered a deeper understanding. Good-performing employees tended to have greater career mobility and autonomy, particularly millennials, perceiving external job opportunities as more associated with personal development objectives (X. Han et al., 2025). In this context, job performance might not serve to reduce turnover intention, but it can signal readiness to explore alternative roles, which was an aspect not fully explained by traditional retention models.

The meaning of work originated as a significant predictor in reducing turnover intention, despite not being a hypothesized path. This unexpected yet strong result reinforced the theoretical role of the meaning of work as an intrinsic motivator that remained influential even in high-pressure and collectivism environments. According to Baumeister and Landau (2018), the experience of meaning was still deeply personal while importance was shaped culturally. Individuals in collectivism societies continued to internalize purpose in work, associating personal and group values in ways that anchored employees to jobs.

4.2 Managerial Implications

Based on a significant increase in the productive-age population, Indonesia was projected to enter the demographic bonus period from 2020 to 2035 (Musrayani Usman et al., 2024). Companies in Indonesia need to adapt quickly to meet the needs of the millennial generation. A more human-centered and employee-focused approach is both a global trend and highly relevant to Indonesia’s cultural values (Wijaya et al., 2023). The result showed the central role of the meaning of work in shaping positive employee outcomes, particularly among millennial workers. A major implication for human resource practices was the strong impact of the meaning of work in improving both job pride and performance. When millennials perceived work as meaningful, employees were more expected to pride in the roles and perform at higher levels. This showed that organizations should invest in designing jobs and work environments in helping employees connect tasks to a larger purpose, follow personal values, and enable individual contributions to be socially and organizationally significant.

The meaning of work in this study showed a direct role in lowering turnover intention. This indicated that improving a sense of purpose at work could serve as a strategic retention tool, specifically for younger generations pursuing meaning in individual professional lives (Barhate & Dirani, 2022). Managers should prioritize initiatives that improve the personal significance of daily tasks and inspire millennials to contribute meaningfully beyond being solely driven by financial rewards by linking their daily work to broader societal contributions (Sun & Sohn, 2021).

Job pride did not significantly reduce turnover intention despite having a positive effect on performance. Therefore, managers should be cautious in assuming that increasing job pride alone would ensure lower turnover intention in collectivism-oriented cultures. Relational and communal factors might play a more dominant role in the decisions of employees to stay or leave the organization (Nipu, 2020). Job performance did not significantly reduce turnover intention, which might be attributed to labor market dynamics. Well-performing employees tended to have greater access to external opportunities, making individuals more expected to leave despite high productivity (Liu et al., 2024). This showed the importance for organizations not only to encourage individual performance, but also meaningfully engage employees as well as improve a sense of job pride that strengthened connection to the organization. Finally, the banking industry pursuing to retain millennial talent should primarily focus on building a strong foundation of the meaning of work, which has been shown to cultivate pride among millennials, improve performance, and reduce turnover intention, even in a collectivism cultural context.

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

In conclusion, this study found that the meaning of work had a significant and positive influence on both job pride and performance. Employees who perceived work as meaningful tended to feel proud and show better performance. Relating to the discussion, job pride positively contributed to job performance. However, job pride and performance did not significantly reduce turnover intention. These results implied that even employees who performed well and pride in the work might still intend to leave the organization. This could occur when strong performance formed external opportunities or when the work did not associate with the social values of the environment employees considered important. In the banking sector, despite millennials expressing pride, this pride did not often translate into organizational loyalty. Based on Social Identity Theory, individuals formed identity through membership in social groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), which can include external communities such as peer groups. In the context of this study, millennial career decisions were more strongly influenced by social affiliations, which contributed to the generational tendency toward frequent job changes (Qadri et al., 2022). Therefore, job pride might be insufficient to reduce turnover intention when reference groups inspired career mobility or prioritized different values.

This study has several limitations similar to all empirical findings. The results were confined to the banking sector in Indonesia, which was an industry characterized by high pressure and high turnover (Getaneh Mekonen et al., 2022). Although the findings focused on the banking sector, the relevance of meaning of work extends across various industries where it helps employees cope with stressors like heavy workloads, irregular hours, and demanding tasks, such as healthcare (Caroccini et al., 2024), military (Smaliukienė et al., 2023), tourism (Guzeller & Celiker, 2019), and hospitality (Le et al., 2023), all of which are considered high pressure or high turnover industries. Therefore, future research should examine how meaning of work functions in different occupational contexts to validate and expand the findings.

Despite the rigorous multistage sampling approach used in the current research, certain methodological limitations were acknowledged. The reliance on Facebook groups for participant recruitment may have introduced self-selection bias, as only banking employees active in online communities were included. As a result, the perspectives of individuals less engaged with these platforms might have been excluded. Therefore, future research needs to address this limitation by incorporating multiple recruitment channels, such as LinkedIn, professional banking associations, or offline networking events, in order to capture a more diverse sample and enhance external validity.

Future research should consider employing marker variable analysis to further assess potential Common Method Variance (CMV) and enhance result accuracy. While this study has implemented preventive measures, incorporating statistical techniques such as marker variables could provide additional validation and strengthen methodological rigor. Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study limited the ability to infer causality or observe changes over time in the examined variables. Future longitudinal designs should be considered to better capture the temporal dynamics and potential causal mechanisms between meaning of work, job pride, performance, and turnover intention.

The theory contributed by inspiring a more context-sensitive understanding of employee attitudes. Building on this, the analysis invited scholars to explore universal assumptions and examine how cultural as well as generational dynamics shaped the way work experiences such as pride, performance, and meaning were translated into intention to stay with or leave an organization, including across different cultural and generational contexts.

References

Ahmed, U., Yong, I. S.-C., Pahi, M. H., & Dakhan, S. A. (2022). Does meaningful work encompass support towards supervisory, worker and engagement relationship? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71(8), 3704–3723. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-06-2020-0321

Ali, F., Nawaz, Z., & Kumar, N. (2024). Internal corporate social responsibility as a strategic tool for employee engagement in public organizations: Role of empathy and organizational pride. Human Systems Management, 43(3), 391–406. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-230118

Ardi, R., & Anggraini, N. (2023). Predicting turnover intention of indonesian millennials workforce in the manufacturing industry: A PLS-SEM approach. Industrial and Commercial Training, 55(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-08-2021-0056

Barhate, B., & Dirani, K. M. (2022). Career aspirations of generation Z: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(1/2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-07-2020-0124

Baumeister, R. F., & Landau, M. J. (2018). Finding the Meaning of Meaning: Emerging Insights on Four Grand Questions. Review of General Psychology, 22(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000145

Blustein, D. L. (2023). Why Work Matters: A Personal, Contextual, and Forward-Looking Exploration of Psychology of Working. The Counseling Psychologist, 51(8), 1149–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000231208939

Buechner, V. L., Stahn, V., & Murayama, K. (2019). The Power and Affiliation Component of Achievement Pride: Antecedents of Achievement Pride and Effects on Academic Performance. Frontiers in Education, 3, 107. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2018.00107

Caringal-Go, J. F., & Hechanova, Ma. R. M. (2018). Motivational Needs and Intent to Stay of Social Enterprise Workers. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1468352

Caroccini, T. P., Balsanelli, A. P., & Neves, V. (2024). The meaning of work for hospital unit nurses: A scoping review. Revista Brasileira de Medicina Do Trabalho, 22(03), 01–09. https://doi.org/10.47626/1679-4435-2023-1116

Carton, A. M. (2018). “I’m Not Mopping the Floors, I’m Putting a Man on the Moon”: How NASA Leaders Enhanced the Meaningfulness of Work by Changing the Meaning of Work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 63(2), 323–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839217713748

Chang, S.-J., Van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88

Charles-Leija, H., Castro, C. G., Toledo, M., & Ballesteros-Valdés, R. (2023). Meaningful Work, Happiness at Work, and Turnover Intentions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043565

De Hooge, I. E., & Van Osch, Y. (2021). I Feel Different, but in Every Case I Feel Proud: Distinguishing Self-Pride, Group-Pride, and Vicarious-Pride. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 735383. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.735383

Diwan, K. A., Chung, J. M., Meyers, C., Van Doeselaar, L., & Reitz, A. K. (2024). Short-term dynamics of pride and state self-esteem change during the university-to-work transition. European Journal of Personality, 38(3), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070231190255

Durrah, O., Allil, K., Gharib, M., & Hannawi, S. (2021). Organizational pride as an antecedent of employee creativity in the petrochemical industry. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(2), 572–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-08-2019-0235

Elian, S., Paramitha, C. D., Gunawan, H., & Maharani, A. (2020). The Impact of Career Development, Work-Family Conflict, and Job Satisfaction on Millennials’ Turnover Intention in Banking Industry. Journal of Business Management Review, 1(4), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.47153/jbmr14.422020

Frian, A., & Mulyani, F. (2018). MILLENIALS EMPLOYEE TURNOVER INTENTION IN INDONESIA. Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.12959/issn.1855-0541.IIASS-2018-no3-art5

Getaneh Mekonen, E., Shetie Workneh, B., Seid Ali, M., Fentie Abegaz, B., Wassie Alamirew, M., & Aemro Terefe, A. (2022). Prevalence of work-related stress and its associated factors among bank workers in Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia: A multi-center cross-sectional study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 16, 100386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2021.100386

Giao, H. N. K., Vuong, B. N., & Tushar, H. (2020). The impact of social support on job-related behaviors through the mediating role of job stress and the moderating role of locus of control: Empirical evidence from the Vietnamese banking industry. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1841359. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1841359

Grillo, P. M., Almeira, D. P. de, & Silva, É. R. P. da. (2021). Job, career or calling: A qualitative exploration of the meaning of work among Brazilian undergraduate architecture students. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, 18(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14488/BJOPM.2021.002

Gun, I., Soyuk, S., & Ozsari, S. H. (2021). Effects of Job Satisfaction, Affective Commitment, and Organizational Support on Job Performance and Turnover Intention in Healthcare Workers. Archives of Health Science and Research, 8(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.5152/ArcHealthSciRes.2021.21044

Guy, M. E. (2014). Emotional Labor: Putting the Service in Public Service: Putting the Service in Public Service (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315704852

Guzeller, C. O., & Celiker, N. (2019). Examining the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention via a meta-analysis. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2019-0094

Hair, J. F. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (Eighth edition). Cengage.

Hamdi, M., Indarti, N., Manik, H. F. G. G., & Lukito-Budi, A. S. (2023). Monkey see, monkey do? Examining the effect of entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge sharing on new venture creation for Gen Y and Gen Z. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(4), 786–807. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-08-2021-0302

Hameed, Z., Khan, I. U., Islam, T., Sheikh, Z., & Khan, S. U. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and employee pro-environmental behaviors: The role of perceived organizational support and organizational pride. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 8(3), 246–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-10-2018-0117

Han, S.-H., Sung, M., & Suh, B. (2021). Linking meaningfulness to work outcomes through job characteristics and work engagement. Human Resource Development International, 24(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1744999

Han, X., Himmelstern, J., & VanHeuvelen, T. (2025). The contribution of work values to early career mobility. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 95, 100996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2024.100996

Hasan, H., Nikmah, F., & Sudarmiatin. (2022). Bank employees’ problems due to the imbalance of work and family demands. Banks and Bank Systems, 17(1), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.17(1).2022.15

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Holtschlag, C., Masuda, A. D., Reiche, B. S., & Morales, C. (2020). Why do millennials stay in their jobs? The roles of protean career orientation, goal progress and organizational career management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 118, 103366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103366

Hong, L., & Zainal, S. R. M. (2024). The role of mindfulness skill and inclusive leadership in job performance among secondary teachers in Hong Kong. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 18(3), 609–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABS-08-2023-0313

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Indrayani, I., Nurhatisyah, N., Damsar, D., & Wibisono, C. (2024). How does millennial employee job satisfaction affect performance? Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 14(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-01-2023-0004

Jain, S. (2019). Exploring relationship between value perception and luxury purchase intention: A case of Indian millennials. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 23(4), 414–439. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-10-2018-0133

Jianmin, S. (2024). Job Performance. In The ECPH Encyclopedia of Psychology (pp. 1–1). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-6000-2_1222-1

Juyumaya, J., Torres-Ochoa, C., & Rojas, G. (2024). Boosting job performance: The impact of autonomy, engagement and age. Revista de Gestão, 31(4), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/REGE-09-2023-0108

Kerins, J., Smith, S. E., & Tallentire, V. R. (2022). ‘Us versus them’: A social identity perspective of internal medicine trainees. Perspectives on Medical Education, 11(6), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-022-00733-9

Kodagoda, T., & Deheragoda, N. (2021). War for Talent: Career Expectations of Millennial Employees in Sri Lanka. Millennial Asia, 12(2), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976399621990542

Koentjaraningrat. (1974). Pengantar Ilmu Antropologi (Introduction to Anthropology). Aksara Baru.

Kurniati, N. M. T., Worthington, E. L., Widyarini, N., Citra, A. F., & Dwiwardani, C. (2020). Does forgiving in a collectivistic culture affect only decisions to forgive and not emotions? REACH forgiveness collectivistic in Indonesia. International Journal of Psychology, 55(5), 861–870. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12648

Le, L. H., Hancer, M., Chaulagain, S., & Pham, P. (2023). Reducing hotel employee turnover intention by promoting pride in job and meaning of work: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 109, 103409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103409

Liao, Z., Wu, L., Zhang, H. J., Song, Z., & Wang, Y. (2023). Exchange through emoting: An emotional model of leader–member resource exchanges. Personnel Psychology, 76(1), 311–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12506

Lin, P. M. C., Au, W. C., Leung, V. T. Y., & Peng, K.-L. (2020). Exploring the meaning of work within the sharing economy: A case of food-delivery workers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102686

Liu, Y., Han, R., Mao, Y., & Xiao, J. (2024). The indirect relationship between employee job performance and voluntary turnover: A meta-analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 101039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2024.101039

Malik, P., & Malik, P. (2024). Should I stay or move on—Examining the roles of knowledge sharing system, job crafting, and meaningfulness in work in influencing employees’ intention to stay. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 11(2), 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-08-2022-0229

Markowski, K. L., & Serpe, R. T. (2025). Continued Refinements of Identity Salience: A Multidimensional Specification. Social Psychology Quarterly, 01902725241311016. https://doi.org/10.1177/01902725241311016

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892

Mobley, W. H., Horner, S. O., & Hollingsworth, A. T. (1978). An evaluation of precursors of hospital employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(4), 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.63.4.408

Musrayani Usman, Hasbi Hasbi, Mario Mario, Ria Renita Abbas, & Rahmat Muhammad. (2024). Women’s Opportunities to Migrate at a Young Age: Taking Advantage of the Momentum of Demographic Bonus. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 1(2), 01–10. https://doi.org/10.62951/ijss.v1i2.22

Nadatien, I., Handoyo, S., Pudjirahardjo, W. J., & Probowati, Y. (2019). The Influence of Organizational Pride on the Performance of Lecturers in Health at the Nahdlatul Ulama University in Surabaya. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, 10(1), 538. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2019.00105.0

Ng, T. W. H., Yam, K. C., & Aguinis, H. (2019). Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Effects on pride, embeddedness, and turnover. Personnel Psychology, 72(1), 107–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12294

Nipu, N. J. (2020). Influence of collectivist societal culture on career choice: A study on the prospective job candidates of Bangladesh. Dynamics of Public Administration, 37(2), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-0733.2020.00010.3

Owens, A., Beattie, E., & Irvine, T. (2024). The Impact of Social Media Use Among Millennial Couples. The Family Journal, 10664807241286804. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807241286804

Park, J., & Gursoy, D. (2012). Generation effects on work engagement among U.S. hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1195–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.02.007

Patahuddin, S. M., & Logan, T. (2019). Facebook as a mechanism for informal teacher professional learning in Indonesia. Teacher Development, 23(1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2018.1524787

Pereira, L., Patrício, V., Sempiterno, M., Da Costa, R. L., Dias, Á., & António, N. (2021). How to Build Pride in the Workplace? Social Sciences, 10(3), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10030104

Poddar, A., & Madupalli, R. (2012). Problematic customers and turnover intentions of customer service employees. Journal of Services Marketing, 26(7), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876041211266512

Qadri, S. U., Bilal, M. A., Li, M., Ma, Z., Qadri, S., Ye, C., & Rauf, F. (2022). Work Environment as a Moderator Linking Green Human Resources Management Strategies with Turnover Intention of Millennials: A Study of Malaysian Hotel Industry. Sustainability, 14(12), 7401. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127401

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

Scheepers, D., & Ellemers, N. (2019). Social Identity Theory. In K. Sassenberg & M. L. W. Vliek (Eds.), Social Psychology in Action (pp. 129–143). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13788-5_9

Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2022). What’s to Like? Facebook as a Tool for Survey Data Collection. Sociological Methods & Research, 51(1), 108–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119882477

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill-building approach (7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Setyaningrum, R. P., Ratnasari, S. L., Soelistya, D., Purwati, T., Desembrianita, E., & Fahlevi, M. (2024). Green human resource management and millennial retention in Indonesian tech startups: Mediating roles of job expectations and self-efficacy. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2348718. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2024.2348718

Shan, S., Ishaq, H. M., & Shaheen, M. A. (2015). Impact of organizational justice on job performance in libraries: Mediating role of leader-member exchange relationship. Library Management, 36(1/2), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-01-2014-0003

Smaliukienė, R., Bekesiene, S., Kanapeckaitė, R., Navickienė, O., Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I., & Vaičaitienė, R. (2023). Meaning in military service among reservists: Measuring the effect of prosocial motivation in a moderated-mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1082685. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1082685

Song, J., Shi, X., Zheng, X., Lu, G., & Chen, C. (2024). The impact of perceived organizational justice on young nurses’ job performance: A chain mediating role of organizational climate and job embeddedness. BMC Nursing, 23(1), 231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01898-w

Soren, A., & Ryff, C. D. (2023). Meaningful Work, Well-Being, and Health: Enacting a Eudaimonic Vision. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(16), 6570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20166570

Sun, J., & Sohn, Y. W. (2021). The Influence of Dual Missions on Employees’ Meaning of Work and Turnover Intention in Social Enterprises. Sustainability, 13(14), 7812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147812

Supanti, D., & Butcher, K. (2019). Is corporate social responsibility (CSR) participation the pathway to foster meaningful work and helping behavior for millennials? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.001

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.

Tan, K.-L., Lew, T.-Y., & Sim, A. K. S. (2019). An innovative solution to leverage meaningful work to attract, retain and manage Generation Y employees in Singapore’s hotel industry. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 11(2), 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-11-2018-0075

Tan, N., Khan, M. I., & Saleh, M. A. (2024). The intersection of big data and healthcare innovation: Millennial perspectives on precision medicine technology. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(4), 100376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2024.100376

Van Der Baan, N. A., Meinke, G., Virolainen, M. H., Beausaert, S., & Gast, I. (2025). Retention of newcomers and factors influencing turnover intentions and behaviour: A review of the literature. Education + Training, 67(1), 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2023-0240

Van Doren, N., Tharp, J. A., Johnson, S. L., Staudenmaier, P. J., Anderson, C., & Freeman, M. A. (2019). Perseverance of effort is related to lower depressive symptoms via authentic pride and perceived power. Personality and Individual Differences, 137, 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.044

Wang, C.-Y., Lin, Y.-K., Chen, I.-H., Wang, C.-S., Peters, K., & Lin, S.-H. (2023). Mediating effect of job performance between emotional intelligence and turnover intentions among hospital nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A path analysis. Collegian, 30(2), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2022.09.006

Widyanti, R., Irhamni, G., Ratna, S., & Basuki. (2020). Organizational Justice and Organizational Pride to Achieve Job Satisfaction and Job Performance. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University, 55(3), 47. https://doi.org/10.35741/issn.0258-2724.55.3.47

Wijaya, C. N., Mustika, M. D., Bulut, S., & Bukhori, B. (2023). The power of e-recruitment and employer branding on Indonesian millennials’ intention to apply for a job. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1062525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1062525

Yang, Y., Yuan, Y., Liu, P., Wu, W., & Huo, C. (2024). Crucial to Me and my society: How collectivist culture influences individual pro-environmental behavior through environmental values. Journal of Cleaner Production, 454, 142211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142211

Yap, W. M., Badri, S. K. Z., Yunus, W. M. A. W. M., & Mansilla, O. (2022). Empowering Millennials Working in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)’ Affective Wellbeing: Role of Volition, Justice and Meaning at Work. In T. Hunt & L. M. Tan (Eds.), Applied Psychology Readings (pp. 163–177). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5086-5_8

You, J., Kim, S., Kim, K., Cho, A., & Chang, W. (2021). Conceptualizing meaningful work and its implications for HRD. European Journal of Training and Development, 45(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-01-2020-0005

Zhang, M., & Zhao, Y. (2021). Job characteristics and millennial employees’ creative performance: A dual-process model. Chinese Management Studies, 15(4), 876–900. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-07-2020-0317

Zimmerman, R. D., & Darnold, T. C. (2009). The impact of job performance on employee turnover intentions and the voluntary turnover process: A meta‐analysis and path model. Personnel Review, 38(2), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480910931316