Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2025, vol. 16, no. 2(33), pp. 462–482 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2025.16.20

Through Sadness to Sustainability: How Meaning Threat Sparks Sustainable Consumption

Zivile Kaminskiene (corresponding author)

ISM University of Management and Economics, Lithuania

Vilnius university, Lithuania

zivile.kaminskiene@evaf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2655-3570

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Justina Barsyte

Vilnius university, Lithuania,

Institute for Advanced Behavioral Research AdCogito, Lithuania

justina@adcogito.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3082-4647

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Elze Uzdavinyte

Vilnius university, Lithuania,

Institute for Advanced Behavioral Research AdCogito, Lithuania

elze@adcogito.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1180-1404

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Abstract. Prior research has highlighted that negative emotions have motivational features toward positive changes; however, findings are mixed and rather limited when it comes to the consumption domain. The present research expands existing perspectives on the motivational role of the negative emotion of sadness, which serves as a mechanism directed toward preventing losses in the future. With our research, we offer evidence that exposure to a meaning threat increases sadness. Moreover, the current research shows the direct effect of meaning threat on sustainable consumption. Most importantly, we demonstrate the mediating role of sadness and test this underlying process with different sustainable products. Theoretical and managerial implications are discussed, along with suggestions for future research.

Keywords: meaning threats, sadness, sustainable consumption, motivation

Received: 28/10/2024. Accepted: 20/8/2025

Copyright © 2025 Zivile Kaminskiene, Justina Barsyte, Elze Uzdavinyte. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Emotions influence what we think and how we think by shaping our attention, perception, memory, physiological state, mood, as well as our goals and behaviors (Cosmides & Tooby, 2000). As such, emotions facilitate adaptation to the environment and serve important psychological functions (Salerno et al., 2014). Emotions help us understand goals, solve problems, protect our health, strengthen resilience, create an attachment to other people, and guide the behavior of groups, social systems, and nations (Pekrun et al., 2002).

Prior research has mostly addressed the bright side of positive emotions and has shown that positive emotions expand a person’s cognitive domain and thus nurture personal resources (Fredrickson, 2013). Furthermore, positive emotions can provide long-term benefits in important areas, including work, physical health, and relationships (Armenta et al., 2017). However, another stream of studies provides evidence that negative emotions can also serve a positive function and have a motivating effect (Forgas, 2013), leading to more cautious, calculated behavior (Tan & Forgas, 2010), indicating a need to take concrete action to deal with the situation following existing social norms (Tan & Forgas, 2010).

Interestingly, prior research suggests that, in some cases, negative emotions can be more effective than positive ones (e.g., by motivating constructive changes in target behavior; Shuman et al., 2018). In our research, we take the negative emotion of sadness as a case point and expect to capture its motivational role when coping with a meaning threat. If sadness can offer new ways to acquire meaning in the consumption domain, such meaning can be obtained by making more sustainable choices. Indeed, recent research shows that sadness evoked by reminders of social norms can lead to more sustainable behaviors, such as using an energy footprint calculator or donating larger sums for specific environment-related projects (Schwartz & Loewenstein, 2017).

Prior research has dedicated a lot of attention to how various positive and negative emotions affect behavior, including in the context of sustainability (e.g., Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Onwezen et al., 2013; Peloza et al., 2013). However, the role of the negative emotion of sadness remains poorly understood (e.g., Forgas, 2017; Garg & Lerner, 2013), as previous findings are mixed (e.g., Cryder et al., 2008). Meanwhile, the relationship between meaning threats and sustainable consumption appears to be previously unexamined. Therefore, building on prior knowledge, we propose that meaning threats will increase sadness, which, in turn, will act as a mechanism for restoring the desired state by experiencing a greater desire to purchase sustainable products.

This paper aims to contribute to the existing knowledge in two ways. First, we contribute to the scientific literature by expanding the knowledge about the motivational role of negative emotions, specifically the emotion of sadness. Although prior research has highlighted motivational features of negative emotions toward positive changes (e.g., Lazarus, 1991; Lench et al., 2011), findings regarding sadness are mixed (Cryder et al., 2008; Garg & Lerner, 2013), and it remains underexplored within the consumption domain (Forgas, 2017; Schwartz & Loewenstein, 2017). In contrast with literature highlighting the role of sadness in driving compensatory consumption—which brings negative consequences (e.g., Allard & White, 2015)—we show that this frequently experienced emotion can, in some cases, actively direct people toward positive behavior. Specifically, the current research shows that sadness elicited by meaning threat leads to sustainable consumption. Second, we expand the knowledge about the ways to reinstate a threatened sense of meaning in life. Prior research has studied how facing meaning threats in life stimulates engagement even in activities that can be unrelated to the threats’ origin, as individuals hope to strengthen their sense of life being meaningful (Heine et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2019). We contribute to the generalizability of previous findings by showing that sustainable consumption might also serve as a source to reinstate threatened meaning in life. To the best of our knowledge, this research is the first to show the link between meaning threats and sustainable consumption.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1 Meaning Threats, Sadness, and Sustainable Consumption

People have a fundamental need for their lives to be meaningful (FioRito et al., 2021). However, during a lifespan, individuals unavoidably face various meaning threats, i.e., “experiences that are inconsistent with the expectations that follow from our understandings” (Proulx & Inzlicht, 2012, p. 318). Meaning threats result in a sense of shaken or lost meaning in life (Park, 2010; Proulx & Inzlicht, 2012).

People can experience meaning threats when a sense of belonging is reduced, e.g., due to social ostracism, social exclusion, or rejection (e.g., Lee & Shrum, 2012; Twenge et al., 2003; Stillman et al., 2009; Zadro et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2019). Prior studies have also shown that the reminders of death (Abeyta et al., 2015; Baumeister, 1991; Heine et al., 2006), personal uncertainty (Randles et al., 2018), traumatic events (Steger & Park, 2012), lack of coherence in the environment (Heine et al., 2006; Heintzelman et al., 2013) have a negative impact on the sense of meaningfulness.

Exposure to meaning threats means experiencing self-discrepancy, which can produce negative emotions (Higgins, 1987; Packard & Wooten, 2013). Indeed, meaning threats are followed by cognitive and emotional processing (see Park, 2010). Cognitive processing refers to the adaptation of beliefs or assumptions (Creamer et al., 1992; Hollon & Kriss, 1984), while emotional processing, on the other hand, focuses on experiencing and exploring emotions (Foa & Kozak, 1986). Both cognitive and emotional processing overlap (Hayes et al., 2007) and are important in reinstating the sense of meaning in life (Hunt et al., 2007; Ullrich & Lutgendorf, 2002).

Previous research has shown the link between various meaning threats and negative emotions. For instance, ostracism elicits anger (e.g., Chow et al., 2008), mortality salience induces fear and anxiety (e.g., Huang et al., 2021), and perceiving oneself as unworthy is related to shame (e.g., Lynd, 2013). If the sense of meaning in life is threatened, individuals lose a sense of purpose, agency, and value in life (Heintzelman & King, 2014). Respectively, when a person learns about the loss (e.g., a goal or valued aspect of the self), this is a moment when the emotion of sadness arises, and this is one of the features that makes sadness different from other overlapping emotions such as anger, anxiety, or yearning (Dalgleish & Power, 2000; Freed & Mann, 2007). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H1: Meaning threat increases sadness.

When individuals are confronted with meaning threats, they often engage in behaviors that help them restore or reaffirm a sense of meaning. This premise is central to several theoretical frameworks.

According to the Meaning Maintenance Model, when people face a meaning threat in one domain, they may seek to restore their sense of meaningfulness by engaging in activities even in unrelated areas (Heine et al., 2006). The Meaning Maintenance Model highlights the flexibility and substitutability of compensatory sources of meaning (Heine et al., 2006). Similarly, the Pragmatic Meaning Regulation theory (Van Tilburg & Igou, 2011) proposes that people striving to regain or strengthen their sense of meaning are more attuned to potential behavioral strategies that can regulate their meaning. Next, the Meaning-Making Model (Park & Folkman, 1997) also supports these compensatory efforts, suggesting that meaning threats are understood as discrepancies in perception between specific instances and general orienting systems. These discrepancies lead to distress and motivate individuals to reduce those discrepancies (Park, 2013). Indeed, Zhang et al. (2019) pointed out that it is too painful to admit meaninglessness; thus, people start actively searching for confirmations that life has meaning after facing meaning threats. Such a mechanism might be explained by the Cognitive Dissonance theory (Festinger, 1962), revealing individuals’ flexibility regarding various sources of meaning: if one domain does not provide meaning in life anymore, alternatives start becoming more important (Zhang et al., 2019).

Engaging in prosocial or responsible behaviors, such as volunteering, spending money to benefit others (Klein, 2017), and pro-environmental actions (Jia et al., 2021), is one of the ways how individuals restore or reaffirm a sense of meaning. Indeed, prior research showed that these behaviors enhance one’s sense of meaning (Dakin et al., 2022) as well as feelings of belonging, which also significantly increases perceptions of meaning in life (FioRito et al., 2021; Lambert et al., 2013). Sustainable consumption, which involves making choices that benefit the environment and society, can be understood as an example of such meaning-restorative behavior.

Although research has started to explore the correlational link between meaning in life and sustainable consumption (Hunecke & Richter, 2019), causal mechanisms remain underexplored. In line with spillover effects observed in meaning-regulation (e.g., Zhang et al., 2019), we propose that individuals exposed to meaning threat in one domain might find engagement in sustainable consumption as a compensatory strategy. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2: Meaning threat increases willingness to buy sustainable products.

2.2 Emotions, Sadness, and Sustainable Consumption

Emotions are important drivers of behavior, including in the domain of sustainability. Prior literature has shown that both positive and negative emotions, such as hope, pride, guilt, anger, shame, and sadness, can positively impact sustainable consumption (e.g., Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Dahl et al., 2003; Ferguson & Branscombe, 2010; Harth et al., 2013; Mallett et al., 2013; Peter & Honea, 2012; Rees et al., 2015; Schwartz & Loewenstein, 2017; Van Zomeren et al., 2010; Van Zomeren et al., 2011; Wang & Wu, 2016). These emotions may motivate consumers to make more sustainable decisions as a means to regulate their negative emotional state, maintain a positive one, or even proactively avoid negative emotions (e.g., anticipated guilt or regret; Carrus et al., 2008; Onwezen et al., 2014; Peloza et al., 2013; Steenhaut et al., 2006) and because the expectations that their behavior will result in a positive emotional experience, so-called “warm glow” (Hartmann et al., 2017; Onwezen et al., 2013; Rezvani et al., 2017).

Among these emotions, sadness remains understudied, particularly in terms of its adaptive motivational functions (Forgas, 2017). If fear, shame, or guilt often provokes immediate action or avoidance (Löw et al., 2015; Schmader & Lickel, 2006), sadness, on the contrary, is related to reflective (Cryder et al., 2008), future-oriented goals such as preventing further losses or restoring coherence after a disruption (Lazarus, 1991; Forgas, 2017; Lench et al., 2011). In the consumption domain, it has been shown that one of the functions of sadness is to make a person more vigilant and thus prevent future losses (Lazarus, 1991; Lench et al., 2011).

Conceptual approaches to sadness show that this emotion occurs after the collapse of a very large and important plan or the loss of a personal goal (Garg & Lerner, 2013; Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987). Respectively, if the meaning is threatened, individuals lose a sense of purpose, agency, and value in life (Heintzelman & King, 2014). Therefore, it is plausible to expect individuals experiencing meaning threats to experience elevated levels of sadness, too. In line with the discrete emotion theory, which states that each discrete emotion causes changes in cognitive, judgmental, experiential, behavioral, and physiological contexts (see Lench et al., 2011 for review), we propose that sadness evoked by meaning threats can motivate individuals to restore meaning by engaging into value-driven behaviors and we take engagement in sustainable consumption as a case point.

Indeed, emerging research shows that individuals engage in prosocial and responsible behavior to restore the sense of meaning (e.g., Jia et al., 2021; Klein, 2017). Sadness may facilitate this process, since it expands the cognition (Gable & Harmon-Jones, 2010) and helps acquire new sources of meaning or appreciate existing sources of meaning more favorably (Tang et al., 2013). Recent research, indeed, shows that sadness evoked by reminders of social norms can lead to more sustainable behaviors (Schwartz & Loewenstein, 2017).

We propose that sadness will play a mediating role between meaning threats and sustainable consumption. Specifically, we argue that meaning threats will increase sadness as a signal of loss. Sadness, in turn, will act as a mechanism for restoring the sense of meaning by engaging in behavior such as sustainable consumption that helps to achieve this aim. We hypothesize:

H3: Meaning threat will increase the extent of sadness felt and, in turn, will lead to a greater willingness to buy sustainable products.

2.3 Overview of Empirical Research

We conducted four experiments and tested our hypotheses across different types of sustainable products. We chose a small, low-cost everyday product (reusable drinking straws) and a larger, more expensive electronic item (power bank) as representative examples. Both reusable drinking straws and power banks are widely recognized and available. More importantly, they are consistent with widely accepted sustainability principles, such as reducing waste and promoting renewable energy. Study 1 provides initial evidence that meaning threat (vs. control) increases the emotion of sadness (H1). Next, Study 2 demonstrates the direct effect of exposure to meaning threat (vs. control) on greater purchase intention of sustainable products (H2). Study 3 shows the downstream consequences of sadness on the purchase intentions of sustainable products. It demonstrates the robustness of our propositions by conveying that exposure to meaning threat (vs. control) increases the emotion of sadness and, in turn, leads to a higher intention to purchase sustainable products (H3). Finally, Study 4 replicates the findings of Study 3 and shows its generalizability by testing the underlying process with a different sustainable product.

Manipulation checks were significant in all experimental studies, showing that the meaning threat condition elicited greater doubt in the belief that life is full of meaning for participants exposed to the meaning threat (vs. control) condition. We did not use any screening measures in any of the studies.

3. Study 1

Study 1 aimed to test whether exposure to meaning threat (vs. control) increases the emotion of sadness.

3.1 Method and Measures

299 British participants (Mage = 32.3, SDage = 11.4, 67.9% female) were recruited from the Prolific Academic online platform to participate in the experiment in return for a small monetary compensation. This study was a part of a larger study. The extent of sadness felt was our dependent variable.

Participants were informed that they were going to be presented with 10 different sentences, one at a time. They were instructed to think about the meaning of each sentence and then rewrite it in their own words on the next page. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions. To manipulate meaning threat, participants were assigned to read and rewrite sentences about life meaninglessness (e.g., “Human life seems like a useless, meaningless treadmill”). In the control condition, sentences were about various facts that are not relevant to meaning in life (e.g., “The Nile River in Africa is the world’s longest river”). This manipulation was drawn from Park and Baumeister (2017), who adapted it from Routledge et al. (2011) and Vohs and Schooler (2008). After the reading and writing task, participants completed a four-item Discrete Emotions Questionnaire, sadness subscale (Harmon-Jones et al., 2016) with items such as “sad”, “grief”, “empty”, and “lonely”, using a seven-point scale, where 1 = “don’t harbor this feeling”, 7 = “extremely” (M = 2.74, SD = 1.41, Cronbach’s α = .80). Finally, participants completed a manipulation check (“How much did the sentences cast doubt on the belief that life is full of meaning?”; 1 = “not at all”, 7 = “very much”; M = 3.41, SD = 1.92; Park & Baumeister, 2017; Routledge et al., 2011).

3.2 Results and Discussion

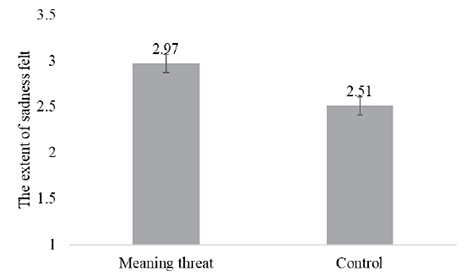

A univariate test was conducted to test the effect of meaning threat on sadness. The result indicates that the extent of sadness felt differed across the conditions. Participants in the meaning threat condition reported feeling more sadness than participants in the control condition (Mthreat = 2.97, SDthreat = 1.58 vs. Mcontrol = 2.51, SDcontrol = 1.18; F(1, 297) = 8.13, p = .005, η2 = .027; see Figure 2).

Figure 2

The Effect of Meaning Threat on Sadness

Study 1 provides initial evidence that meaning threats increase sadness and supports Hypothesis 1.

4. Study 2

With Study 2, we opted to test whether meaning threat (vs. control) has a direct effect on intentions to purchase sustainable products.

4.1 Method and Measures

A total of 199 British participants (Mage = 36, SDage = 13.4, 70.4% female) were recruited from the Prolific Academic online platform to participate in the experiment in return for a small monetary compensation. This study was a part of a larger study. The design was a single factor between-subjects design. The independent variable had two levels: meaning threat (1) present and (2) absent. Purchase intention was our main dependent variable.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions. For meaning threat and control conditions we used the same reading and writing task as in Study 1. After the manipulation procedure participants were provided with a picture and description of sustainable drinking straws: “Reduce plastic waste with reusable drinking straws! Sustainable, reusable stainless steel drinking straws. Available in a convenient pack of 8. Two different lengths and shapes for different needs” (see Apendix A) and asked to indicate their intentions to purchase. To measure purchase intention, we used a four-item scale (adapted from Putrevu & Lord, 1994). Participants were asked to indicate the extent of agreement with each statement on a seven-point Likert scale (e.g., “If someone offered me these drinking straws, I would probably buy it”; 1 = “totally disagree”, 7 = “totally agree”; M = 4.33, SD = 1.88, Cronbach’s α = .96). Finally, participants completed a manipulation check, the same as in Study 1 (M = 2.97, SD = 1.92; Park & Baumeister, 2017; Routledge et al., 2011), were thanked and debriefed.

4.2 Results and Discussion

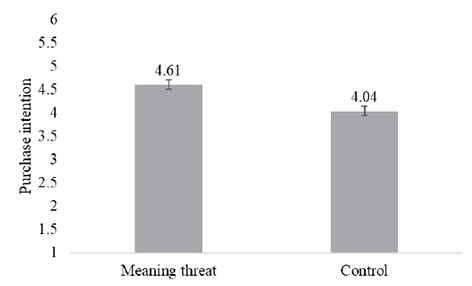

We performed a univariate analysis to evaluate the effect of meaning threat on sustainable purchase intention. The results prove the direct effect of meaning threat (vs. control) on the intention to purchase sustainable product, as a univariate test showed that the purchase intention significantly differed across the conditions. Participants in the meaning threat condition reported greater purchase intention compared to participants in the control condition (Mthreat = 4.61, SDthreat = 1.73 vs. Mcontrol = 4.04,

SDcontrol = 1.99; F(1, 197) = 4.68, p = .032, η2 = .023; see Figure 3).

Figure 3

The Effect of Meaning Threat on Sustainable Purchase Intention

Study 2 reveals the direct effect of meaning threat on sustainable purchase intention and supports Hypothesis 2, stating that meaning threat (vs. control) increases willingness to buy sustainable products.

5. Study 3

Study 3 tested the downstream consequences of meaning threat on the intention to purchase a sustainable product. More particularly, we aimed to assess the underlying mechanism by testing the emotion of sadness as a mediator between meaning threat and purchase intention.

5.1 Method and Measures

A total of 199 British participants (Mage = 35.4, SDage = 13.4, 70.4% female) were recruited from the Prolific Academic online platform to participate in the experiment in return for a small monetary compensation. This study was a part of a larger study. The design was a single-factor between-subjects design. The independent variable had two levels: meaning threat (1) present, (2) absent. Purchase intention was our main dependent variable, and the emotion of sadness was a mediator in our model.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions and had a reading and writing task for the manipulation procedure, which was identical to the one used in Study 1 and Study 2. After manipulation, participants were asked to complete the same four-item Discrete Emotions Questionnaire, sadness subscale (Harmon-Jones et al., 2016; M = 2.24, SD = 1.50, Cronbach’s α = .90) as in Study 1. Further, participants were presented with a picture and description of sustainable drinking straws identical to the one used in Study 2 and asked to evaluate their intention to purchase these straws (adapted from Putrevu & Lord, 1994; M = 4.43, SD = 2.10, Cronbach’s α = .98). Finally, participants completed a manipulation check (M = 3.20, SD = 2.02; Park & Baumeister, 2017; Routledge et al., 2011), were thanked and debriefed.

5.2 Results and Discussion

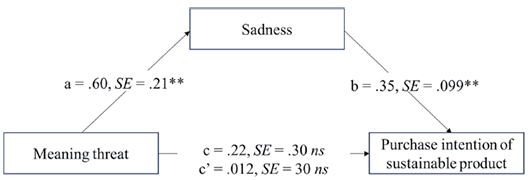

Using the PROCESS macro for SPSS, we tested the mediation model (Hayes, 2022; PROCESS; Model 4, 5000 boot-strapped samples) and observed that the relationship between meaning threat presence (dummy coded, 0 = control; 1 = threat) and intention to purchase the sustainable product was mediated by the emotion of sadness. Corroborating the analysis above, the meaning threat presence (vs. control) increases the extent of sadness felt (path a: B = .60, SE = .21, t(197) = 2.87, p = .005). In turn, the emotion of sadness increases the purchase intention of a sustainable product (path b: B = .35, SE = .099, t(196) = 3.54, p < .001). Next, the direct effect of meaning threat presence (vs. control) on the purchase intention of a sustainable product was not significant (path c’: B = .012, SE = .30, t(196) = .041, p = .97) as well as total effect (path c: B = .22, SE = .30, t(197) = .74, p = .46). Importantly, to assess whether the impact of meaning threat presence on the intention to purchase sustainable products is mediated by the emotion of sadness, we assessed the indirect effect. The analysis shows that the impact of meaning threat presence (vs. control) on purchase intention was indeed fully mediated by the emotion of sadness as the 95% confidence interval did not include zero (effect = .21, 95% CI [.053 to .41]; see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Meaning Threat Presence Effects on Intention to Purchase Sustainable Products via Emotion of Sadness

Note. * p <.05, ** p <.01, ns = non-significant.

The results of Study 3 support H3 by showing that meaning threat (vs. control) increases the extent of sadness felt and, in turn, leads to greater intention to purchase sustainable products.

6. Study 4

Study 4 aimed to replicate the findings of Study 3 by testing the processes using a different sustainable product without highlighting its sustainability benefits.

6.1 Method and measures

A total of 199 British participants (Mage = 37.2, SDage = 14.8, 70.4% female) were recruited from the Prolific Academic online platform to participate in the experiment in return for a small monetary compensation. This study was a part of a larger study. The design was a single-factor between-subjects design. The independent variable had two levels: meaning threat (1) present and (2) absent. Purchase intention was our main dependent variable, and the emotion of sadness was a mediator.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions and had a reading and writing task for the manipulation procedure, which was identical to the one used in the first three studies. After manipulation, participants were asked to complete the same four-item Discrete Emotions Questionnaire, sadness subscale (Harmon-Jones et al., 2016; M = 2.33, SD = 1.43, Cronbach’s α = .88) as in Studies 1 and 3. Further, participants were presented with a picture of a portable power bank together with a description: “Be practical with a portable charger and external backup battery! Charger and portable power bank with a high-efficiency solar panel. The battery is capable of charging your tablet or smartphone several times. Protection for overdischarges allows you to use your electric devices even more efficiently!” (see Apendix B). Next, participants were asked to evaluate their intention to purchase this power bank using four statements on a seven-point Likert scale (e.g., “If someone offered me this power bank, I would probably buy it”; 1 = “totally disagree”, 7 = “totally agree”; adapted from Putrevu & Lord, 1994; M = 4.15, SD = 1.85, Cronbach’s α = .97). Finally, as in the previous study, participants completed a manipulation check (M = 3.12, SD = 2.04; Park & Baumeister, 2017; Routledge et al., 2011), answered to the control question whether they consider the power bank presented earlier to be sustainable using a seven-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all”, 7 = “very much”; M = 4.44, SD = 1.78), were thanked and debriefed.

6.2 Results and Discussion

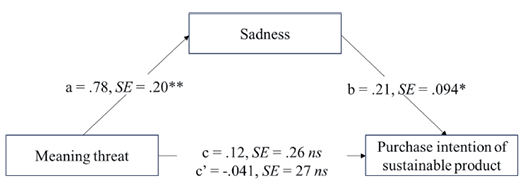

Using the PROCESS macro for SPSS, we performed mediation analysis (Hayes, 2022; PROCESS; Model 4, 5000 boot-strapped samples) and observed that the relationship between meaning threat presence (dummy coded, 0 = control; 1 = meaning threat) and intention to purchase sustainable products was mediated by the emotion of sadness. The meaning threat presence (vs. control) increases the extent of sadness felt (path a: B = .78, SE = .20, t(197) = 3.98, p < .001). In turn, the emotion of sadness increases the purchase intention of a sustainable product (path b: B = .21, SE = .094, t(196) = 2.23, p = .027). Next, the direct effect of meaning threat presence (vs. absence) on the purchase intention of sustainable product was not significant (path c’: B = -.041, SE = .27, t(196) = -.15, p = .88), as well as total effect (path c: B = .12, SE = .26, t(197) = .47, p = .64). Importantly, to assess whether the impact of meaning threat presence on the intention to purchase sustainable products is mediated by the emotion of sadness, we assessed the indirect effect. The analysis shows that the impact of meaning threat presence (vs. control) on purchase intention was indeed fully mediated by emotion of sadness as the 95% confidence interval did not include zero (effect = .16, 95% CI [.019 to .35]; see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Meaning Threat Presence Effects on Intention to Purchase Sustainable Products via the Emotion of Sadness

Note. * p <.05, ** p <.01, ns = non-significant.

The results of Study 4 support H3 by showing that meaning threat (vs. control) increases the extent of sadness felt and, in turn, leads to greater intention to purchase sustainable products.

7. General Discussion

The current research findings add to the understanding of the motivational role of the emotion of sadness in the sustainable consumption domain. Prior research has suggested that meaning threats lead to negative affect and psychological discomfort (e.g., Garg & Lerner, 2013; Heintzelman & King, 2014). Our work replicates these findings by showing that meaning threats have a strong effect on causing greater sadness. Most importantly, we expand prior knowledge and demonstrate that negative emotion of sadness not only signals psychological pain, but also performs a motivational role, sparking positive changes, specifically by increasing willingness to engage in sustainable consumption.

These findings are theoretically significant since they contribute to a longstanding debate within emotion research in consumer behavior. One line of prior research highlights the demotivating or passiveness-inducing nature of sadness (e.g., Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987). Meanwhile, more recent research emphasizes the regulatory and prevention functions of sadness (e.g., Andrade & Cohen, 2007; Forgas, 2017; Garg & Lerner, 2013). Our findings are in line with the recent stream of literature, since they suggest that sadness rooted in exposure to meaning threats may activate behaviors aiming to restore a sense of meaningful life. This contributes to a better understanding of sadness as a motivational emotion in the consumption domain, moving beyond its previously assumed maladaptive or compensatory roles (e.g., Cryder et al., 2008; Allard & White, 2015).

With our research, we also shed more light on how individuals cope when facing meaning threats. Our findings are in line with the Meaning Maintenance Model (Heine et al., 2006) and the Meaning-Making Model (Park & Folkman, 1997), as we demonstrate that individuals can re-find meaning through behaviors even in unrelated, not threatened areas. Prior research has identified several ways in which individuals seek to restore or reaffirm a sense of meaning in life, e.g., volunteering, spending money to benefit others (Klein, 2017), engagement in pro-environmental or sense of belonging inducing actions (FioRito et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021; Lambert et al., 2013). Our research is the first to show that sustainable consumption can also serve a meaning-restorative function, which not only broadens the scope of strategies for restoring the sense of meaning in life but also introduces engagement in sustainable consumption as a psychologically relevant response to meaning threat.

Finally, our work deepens knowledge by showing the underlying process between exposure to meaning threat and greater engagement in sustainable consumption. By offering experimental evidence to demonstrate causal relationships and showing how sadness explains the link between meaning threat and sustainable consumption, we advance the literature on both negative emotion and sustainable consumption. Prior research has paid attention to correlational links between meaning in life and sustainable behavior (e.g., Hunecke & Richter, 2019). Meanwhile, the current research expands the knowledge by providing causal evidence for the emotional process involved, in such a way emphasizing the value of integrating existential psychology when understanding and explaining consumer behavior, especially in the sustainability domain.

7.1 Managerial Implications

Our research provides important managerial implications. First, given our findings that meaning threat increases sadness, which in turn boosts sustainable consumption, policymakers and managers can design campaigns highlighting that sustainable consumption can serve as a meaningful way to cope with emotionally challenging situations. More particularly, messages might promote engagement in sustainable consumption as an opportunity to reaffirm the sense of meaning in life, responding to sadness with meaningful action.

Second, sustainable consumption is related to long-term benefits that primarily concern future generations rather than immediate personal benefits (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). It also requires more effort, even sacrifice, as sustainable consumption is associated with higher costs (e.g., Zhao et al., 2014). We did not directly test the positioning of sustainable consumption; however, our findings suggest that framing sustainable consumption as a form of emotional regulation or purpose restoration may help highlight a new perspective of engagement in sustainable consumption by showing its personal relevance and benefits.

Third, findings of our work suggest that consumers exposed to meaning threats may be more receptive to messages related to sustainable consumption. While the findings are limited and do not provide information regarding such consumers’ segments, managers can provide targeted offers during situations related to meaning threats (e.g., during economic or environmental crises) and test consumers’ responsiveness to the emotional cues.

7.2 Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Despite important contributions, our study has several limitations that future research might address. First, regarding negative emotions, further research is needed to explain why the emotion of sadness increases the willingness to engage in sustainable consumption. Testing various boundary conditions could shed more light on this question. Moreover, future research could expand our findings by including other emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger, or fear) as parallel mediators, examine their relative contributions, and disentangle the complex emotional pathways linking meaning threats and sustainable consumption. Second, sustainable consumption might provide various benefits—environmental, social, or economic—, and future studies might explore whether sadness produces different effects when highlighting one or another benefit. Third, future research could explore the generalizability of current findings by testing consumers’ decisions in a field setting where the purchase choices are made in the presence of product variety, including both sustainable, regular, or even indulging choices. Fourth, in our studies, all individuals meeting the inclusion criteria could participate, regardless of gender. Therefore, the gender distribution in our samples was uneven. Although we did not find a significant moderating effect of gender on the relation between meaning treat presence (vs. control) and sadness across all studies, Study 2 showed that males had increased sustainable purchase intention when exposed to meaning threat (vs. control) condition, meanwhile, for females, the effect was not present. Prior research has demonstrated that gender may influence the frequency and intensity of emotions felt (e.g., Bradley et al., 2001; Grossman & Wood, 1993; Lench et al., 2011; Wood et al., 1989); moreover, individuals of different genders apply different sadness regulation strategies (see Zaid et al., 2021 for review). Thus, future studies could address this limitation and apply the quotas for the gender makeup of the sample when further investigating the role of sadness or other emotions in the responsible consumption domain. Fifth, in our research, we manipulated the sense of meaning in life by threatening the life purpose account. However, it is worth testing whether other meaning threats (e.g., sense of belongingness) would produce the same effects. Finally, we show the causal relationships among the constructs under investigation; however, another research method, such as qualitative interviews, would be a valuable tool to delve more thoroughly into why sadness leads to increased sustainable behavior.

References

Abeyta, A. A., Routledge, C., Juhl, J., & Robinson, M. D. (2015). Finding meaning through emotional understanding: Emotional clarity predicts meaning in life and adjustment to existential threat. Motivation and Emotion, 39, 973–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9500-3

Allard, T., & White, K. (2015). Cross-domain effects of guilt on desire for self-improvement products. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(3), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv024

Andrade, E. B., & Cohen, J. B. (2007). On the consumption of negative feelings. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(3), 283–300. https://doi.org/10.1086/519498

Antonetti, P., & Maklan, S. (2014). Feelings that make a difference: How guilt and pride convince consumers of the effectiveness of sustainable consumption choices. Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1841-9

Armenta, C. N., Fritz, M. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). Functions of positive emotions: Gratitude as a motivator of self-improvement and positive change. Emotion Review, 9(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916669596

Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Meanings of life. Guilford press.

Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Sabatinelli, D., & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation II: Sex differences in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 300. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.300

Carrus, G., Passafaro, P., & Bonnes, M. (2008). Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: The case of recycling and use of public transportation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.09.003

Chow, R. M., Tiedens, L. Z., & Govan, C. L. (2008). Excluded emotions: The role of anger in antisocial responses to ostracism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(3), 896–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.09.004

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2000). Evolutionary psychology and the emotions. Handbook of Emotions, 2(2), 91–115. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_516-1

Creamer, M., Burgess, P., & Pattison, P. (1992). Reaction to trauma: A cognitive processing model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(3), 452. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.101.3.452

Cryder, C. E., Lerner, J. S., Gross, J. J., & Dahl, R. E. (2008). Misery is not miserly: Sad and self-focused individuals spend more. Psychological Science, 19(6), 525–530. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02118.x

Dahl, D. W., Honea, H., & Manchanda, R. V. (2003). The nature of self-reported guilt in consumption contexts. Marketing Letters, 14, 159–171. DOI: 10.1023/A:1027492516677

Dakin, B. C., Tan, N. P., Conner, T. S., & Bastian, B. (2022). The relationship between prosociality, meaning, and happiness in everyday life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(6), 2787–2804. DOI: 10.1007/s10902-022-00526-1

Dalgleish, T., & Power, M. (Eds.). (2000). Handbook of cognition and emotion. John Wiley & Sons. DOI: 10.1017/S0033291799212433

Ferguson, M. A., & Branscombe, N. R. (2010). Collective guilt mediates the effect of beliefs about global warming on willingness to engage in mitigation behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.11.010

Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. Scientific American, 207(4), 93–106.

FioRito, T. A., Routledge, C., & Jackson, J. (2021). Meaning-motivated community action: The need for meaning and prosocial goals and behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110462. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2020.110462

Foa, E. B., & Kozak, M. J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological bulletin, 99(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.20

Forgas, J. P. (2013). Don’t worry, be sad! On the cognitive, motivational, and interpersonal benefits of negative mood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412474458

Forgas, J. P. (2017). Can sadness be good for you?. Australian Psychologist, 52(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12232

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 1–53). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Freed, P. J., & Mann, J. J. (2007). Sadness and loss: Toward a neurobiopsychosocial model. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(1), 28–34. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.28

Gable, P., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2010). The motivational dimensional model of affect: Implications for breadth of attention, memory, and cognitive categorisation. Cognition and Emotion, 24(2), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930903378305

Garg, N., & Lerner, J. S. (2013). Sadness and consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(1), 106–113. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcps.2012.05.009

Grossman, M., & Wood, W. (1993). Sex differences in intensity of emotional experience: A social role interpretation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 1010. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.1010

Harmon-Jones, C., Bastian, B., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2016). The discrete emotions questionnaire: A new tool for measuring state self-reported emotions. PloS One, 11(8), e0159915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159915

Harth, N. S., Leach, C. W., & Kessler, T. (2013). Guilt, anger, and pride about in-group environmental behaviour: Different emotions predict distinct intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 34, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.12.005

Hartmann, P., Eisend, M., Apaolaza, V., & D‘Souza, C. (2017). Warm glow vs. altruistic values: How important is intrinsic emotional reward in proenvironmental behavior?. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 52, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.05.006

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Counterfactual/potential outcomes “causal mediation analysis” with treatment by mediator interaction using PROCESS (Canadian Centre for Research Analysis and Methods Technical Report 02204).

Hayes, A. M., Feldman, G. C., Beevers, C. G., Laurenceau, J. P., Cardaciotto, L., & Lewis-Smith, J. (2007). Discontinuities and cognitive changes in an exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(3), 409. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.409

Heine, S. J., Proulx, T., & Vohs, K. D. (2006). The meaning maintenance model: On the coherence of social motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1

Heintzelman, S. J., & King, L. A. (2014). Life is pretty meaningful. American Psychologist, 69(6), 561. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035049

Heintzelman, S. J., Trent, J., & King, L. A. (2013). Encounters with objective coherence and the experience of meaning in life. Psychological Science, 24(6), 991–998. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612465878

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Hollon, S. D., & Kriss, M. R. (1984). Cognitive factors in clinical research and practice. Clinical Psychology Review, 4(1), 35–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(84)90036-9

Huang, S., Du, H., & Qu, C. (2021). Emotional responses to mortality salience: Behavioral and ERPs evidence. Plos one, 16(3), e0248699. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248699

Hunecke, M., & Richter, N. (2019). Mindfulness, construction of meaning, and sustainable food consumption. Mindfulness, 10(3), 446–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0986-0

Hunt, M., Schloss, H., Moonat, S., Poulos, S., & Wieland, J. (2007). Emotional processing versus cognitive restructuring in response to a depressing life event. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31, 833–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-007-9156-8

Jia, F., Soucie, K., Matsuba, K., & Pratt, M. W. (2021). Meaning in life mediates the association between environmental engagement and loneliness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2897. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062897

Klein, N. (2017). Prosocial behavior increases perceptions of meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(4), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1209541

Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499186

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American psychologist, 46(8), 819. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

Lee, J., & Shrum, L. J. (2012). Conspicuous consumption versus charitable behavior in response to social exclusion: A differential needs explanation. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(3), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1086/664039

Lench, H. C., Flores, S. A., & Bench, S. W. (2011). Discrete emotions predict changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology: a meta-analysis of experimental emotion elicitations. Psychological Bulletin, 137(5), 834. DOI: 10.1037/a0024244

Lench, H. C., Flores, S. A., & Bench, S. W. (2011). Discrete emotions predict changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology: A meta-analysis of experimental emotion elicitations. Psychological bulletin, 137(5), 834. DOI: 10.1037/a0024244

Löw, A., Weymar, M., & Hamm, A. O. (2015). When threat is near, get out of here: Dynamics of defensive behavior during freezing and active avoidance. Psychological Science, 26(11), 1706–1716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615597332

Lynd, H. M. (2013). On shame and the search for identity (Vol. 145). Routledge.

Mallett, R. K., Melchiori, K. J., & Strickroth, T. (2013). Self-confrontation via a carbon footprint calculator increases guilt and support for a proenvironmental group. Ecopsychology, 5(1), 9–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2012.0067

Oatley, K., & Johnson-Laird, P. N. (1987). Towards a cognitive theory of emotions. Cognition and emotion, 1(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699938708408362

Onwezen, M. C., Antonides, G., & Bartels, J. (2013). The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology, 39, 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2013.07.005

Onwezen, M. C., Bartels, J., & Antonides, G. (2014). Environmentally friendly consumer choices: Cultural differences in the self-regulatory function of anticipated pride and guilt. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.07.003

Packard, G., & Wooten, D. B. (2013). Compensatory knowledge signaling in consumer word-of-mouth. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(4), 434–450. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcps.2013.05.002

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301

Park, C. L. (2013). The meaning making model: A framework for understanding meaning, spirituality, and stress-related growth in health psychology. European Health Psychologist, 15(2), 40–47.

Park, C. L., & Folkman, S. (1997). Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of general psychology, 1(2), 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.1.2.115

Park, J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2017). Meaning in life and adjustment to daily stressors. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(4), 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1209542

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4

Peloza, J., White, K., & Shang, J. (2013). Good and guilt-free: The role of self-accountability in influencing preferences for products with ethical attributes. Journal of Marketing, 77(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0454

Peter, P. C., & Honea, H. (2012). Targeting social messages with emotions of change: The call for optimism. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 31(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.11.098

Proulx, T., & Inzlicht, M. (2012). The five “A” s of meaning maintenance: Finding meaning in the theories of sense-making. Psychological Inquiry, 23(4), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2012.702372

Putrevu, S., & Lord, K. R. (1994). Comparative and noncomparative advertising: Attitudinal effects under cognitive and affective involvement conditions. Journal of Advertising, 23(2), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1994.10673443

Randles, D., Benjamin, R., Martens, J. P., & Heine, S. J. (2018). Searching for answers in an uncertain world: Meaning threats lead to increased working memory capacity. PloS one, 13(10), e0204640. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204640

Rees, J. H., Klug, S., & Bamberg, S. (2015). Guilty conscience: motivating pro-environmental behavior by inducing negative moral emotions. Climatic Change, 130, 439–452. DOI: 10.1007/s10584-014-1278-x

Rezvani, Z., Jansson, J., & Bengtsson, M. (2017). Cause I’ll feel good! An investigation into the effects of anticipated emotions and personal moral norms on consumer pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Promotion Management, 23(1), 163–183. DOI: 10.1080/10496491.2016.1267681

Routledge, C., Arndt, J., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Hart, C. M., Juhl, J., Vingerhoets A. J. J. M., & Schlotz, W. (2011). The past makes the present meaningful: Nostalgia as an existential resource. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 638. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024292

Salerno, A., Laran, J., & Janiszewski, C. (2014). Hedonic eating goals and emotion: When sadness decreases the desire to indulge. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(1), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1086/675299

Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2006). The approach and avoidance function of guilt and shame emotions: Comparing reactions to self-caused and other-caused wrongdoing. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 42–55. DOI:10.1007/s11031-006-9006-0

Schwartz Perlroth, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2017). The chill of the moment: Emotions and proenvironmental behavior. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 36(2), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.16.132

Shuman, E., Halperin, E., & Reifen Tagar, M. (2018). Anger as a catalyst for change? Incremental beliefs and anger’s constructive effects in conflict. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(7), 1092–1106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217695442

Steenhaut, S., & Van Kenhove, P. (2006). The mediating role of anticipated guilt in consumers’ ethical decision-making. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 269–288. DOI: 10.1007/s10551-006-9090-9

Steger, M. F., & Park, C. L. (2012). The creation of meaning following trauma: Meaning making and trajectories of distress and recovery. In R. A. McMackin, E. Newman, J. M. Fogler, & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Trauma therapy in context: The science and craft of evidence-based practice (pp. 171–191). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13746-008

Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 686–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007

Tan, H. B., & Forgas, J. P. (2010). When happiness makes us selfish, but sadness makes us fair: Affective influences on interpersonal strategies in the dictator game. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(3), 571–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.01.007

Tang, D., Kelley, N. J., Hicks, J. A., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2013). Emotions and meaning in life: A motivational perspective. In J. A. Hicks & C. Routledge (Eds.), The experience of meaning in life: Classical perspectives, emerging themes, and controversies (pp.117–128).

Twenge, J. M., Catanese, K. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Social exclusion and the deconstructed state: time perception, meaninglessness, lethargy, lack of emotion, and self-awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 409. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.409

Ullrich, P. M., & Lutgendorf, S. K. (2002). Journaling about stressful events: Effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(3), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10

Van Tilburg, W. A., & Igou, E. R. (2011). On boredom and social identity: A pragmatic meaning-regulation approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(12), 1679–1691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211418530

Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Bettache, K. (2011). Can moral convictions motivate the advantaged to challenge social inequality? Extending the social identity model of collective action. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(5), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430210395637

Van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., & Leach, C. W. (2010). Experimental evidence for a dual pathway model analysis of coping with the climate crisis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.02.006

Vohs, K. D., & Schooler, J. W. (2008). The value of believing in free will: Encouraging a belief in determinism increases cheating. Psychological Science, 19(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02045.x

Wang, J., & Wu, L. (2016). The impact of emotions on the intention of sustainable consumption choices: evidence from a big city in an emerging country. Journal of Cleaner Production, 126, 325–336. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.119

Wood, W., Rhodes, N., & Whelan, M. (1989). Sex differences in positive well-being: A consideration of emotional style and marital status. Psychological Bulletin, 106(2), 249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.249

World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future (Brundtland Report). United Nations. http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm

Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(4), 560–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2003.11.006

Zaid, S. M., Hutagalung, F. D., Bin Abd Hamid, H. S., & Taresh, S. M. (2021). Sadness regulation strategies and measurement: a scoping review. PLoS One, 16(8), e0256088. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256088

Zhang, H., Sang, Z., Chan, D. K. S., & Schlegel, R. (2019). Threats to belongingness and meaning in life: A test of the compensation among sources of meaning. Motivation and Emotion, 43, 242–254. DOI: 10.1007/s11031-018-9737-8

Zhao, H. H., Gao, Q., Wu, Y. P., Wang, Y., and Zhu, X. D. (2014). What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. Journal of Cleaner Production, 63, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.05.021

Appendix A

Picture and Description of Sustainable Drinking Straws.

|

Reduce plastic waste with reusable drinking straws! Sustainable, reusable stainless steel drinking straws Available in a convenient pack of 8 Two different lengths and shapes for different needs |

|

Appendix B

Picture and Description of Sustainable Power Bank.

|

Be practical with portable charger and external backup battery! Charger and portable power bank with high efficiency solar panel Battery capable of charging your tablet or smartphone for several times Protection for overdischarges allows you to use your electric devices even more efficiently! |

|