Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2025, vol. 16, no. 2(33), pp. 412–434 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2025.16.18

Analyzing the Linkages between Diaspora Remittances, Institutions, and Self-Employed Business Activities: Insights from an Emerging Economy

Idowu Emmanuel Olubodun (corresponding author)

Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria

iolubodun@oauife.edu.ng

https://ror.org/04snhqa82

James Temitope Dada

Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria

jamesdada@oauife.edu.ng

https://ror.org/04snhqa82

Adebanji A. W. Ayeni

Wigwe University, Nigeria

North West University, South Africa

adebanjiayeni@hotmail.com

https://ror.org/053vrqh41

Kehinde Oso Osotimehin

Obafemi Awolowo University, Nigeria

kosotime@oauife.edu.ng

https://ror.org/04snhqa82

Abstract. Diaspora remittance either smooths consumption, boosts welfare among recipients, or enhances the balance of payment in economies such as developing nations. Nonetheless, institutions that support its usefulness for financing business are always a concern, as they may not encourage interest in self-employment. The study investigates the linkages between diaspora remittances, institutions, and self-employed business activities. The integration is essential for promoting entrepreneurship while solving the unemployment problem. Annual time series data sets covering the period from 1991 to 2020 were used in Nigeria. The autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) is used as the baseline. Three long-run estimate techniques are used for sensitivity analysis. The short-run coefficient of diaspora remittance on self-employment is positive and significant. In the long run, the effect of diaspora remittance on self-employment is significantly negative. It shows that diaspora remittances are used for immediate consumption, rather than translating into long-term employment generation in Nigeria. However, the impact of institutions on self-employment, in the short and long run, is significantly negative revealing poor institutions that are inadequate for employment creation. Due to poor institutional quality, diaspora remittances do not translate to long-run self-employment creation. Policymakers must strengthen the institutional environment to incentivize diasporans to remit.

Keywords: diaspora remittance, institutions, self-employment, Nigeria

Received: 18/11/2024. Accepted: 23/9/2025

Copyright © 2025 Idowu Emmanuel Olubodun, James Temitope Dada, Adebanji A. W. Ayeni, Kehinde Oso Osotimehin. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Self-employment enables individuals to follow their passions. This enables Africa to tap into the entrepreneurial potential of its population. The World Bank (2023) report reveals a steady rise in diaspora remittances, with a staggering $54 billion flowing into sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, the National Bureau of Statistics report for the first quarter of 2024 shows that 84% of the Nigerian working class is self-employed. This statistic may resemble unsecured jobs, low wages, and poor work conditions, with very few being highly skilled and well remunerated, as observed by Mourougane et al. (2020) in OECD nations, where 15% of the workforce represented self-employed persons. However, the portion of the amount remitted to sub-Saharan Africa reported by the World Bank that is used to drive and support self-employment is often unknown. Mohammed and Karagöl (2023) confirm the concern. Sometimes, one assumes that the institutional quality in different countries could be the source of the threat, which is why the utilization of remittances is inconsequential. Rodrik et al. (2004) emphasize the importance of institutional quality for economic growth. The study by Goshu (2020) notes that institutions are critical impediments to people’s ability to start their businesses. The challenge is not limited to the individual country’s environment alone; foreign competition also contributes to the obstacles to self-employment (Diez & Ozdagli, 2011). Youths receiving remittance may not have an interest in establishing their own business. This contradicts the example in Macedonia, where Petreski and Mojsoska-Blazevski (2015) found that households receiving remittances are more likely to start their businesses than their counterparts in non-receiving households.

Several African economies’ unemployment rates have not decreased despite efforts to mitigate the issue. In 2023, for instance, the unemployment rate in Eswatini stood at 37.6 percent, and it is unlikely to decrease anytime soon (Statista, 2024). This alarming rate concerns the government and policymakers, as it keeps them worrying about the effectiveness of various interventions developed and deployed to reduce unemployment. In developing countries, self-employment is prevalent because these nations often lack job opportunities (Giambra & McKenzie, 2019; Ajide et al., 2021). Providing opportunities to start businesses would be a key policy option in this situation. Government interventions, such as YOUWIN in Nigeria, YOP and WINGS in Uganda, Nairobi microfinancing, SLMS and SIYB in Sri Lanka, Ghana Microenterprises, and various interventions in African nations, are often inadequate funding sources for stimulating self-employment. Due to the increasing poverty rate, emerging economies in the African region should be more deliberate in their efforts. In 2023, poverty in Nigeria and DR Congo ranked highest, with 11.3 and 9.6 percent in the region (Statista, 2024). One way to address this is by boosting the intention of any entrepreneurial endeavour that impacts labour market outcomes (Premand et al., 2016), thereby raising the necessity for good institutional quality.

Financing issues often characterize self-employment. Additionally, institutional outlooks across nations are often unfair to individuals who aspire to start their businesses. The question around these daunting challenges remains unanswered. This study aims to investigate the following question: Do diaspora remittances and institutional quality impact self-employment in emerging economies?

Based on the foregoing, this study makes the following contributions to the literature. First, the study examines the joint roles of diaspora remittances and institutions on self-employment in Nigeria, which is largely missing in the empirical literature. Second, the study focuses on an emerging economy, Nigeria. Nigeria provides an interesting study area, being the largest recipient of diaspora remittances in sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, 2024; Dada & Akinlo, 2023). Specifically, Nigeria received a total value of $20.98 billion in diaspora remittances in 2024, which is more than 40% of the total remittance inflow into Sub-Saharan African countries (World Bank, 2024). Similarly, institutional indicators such as law and order, government stability, corruption control, democratic accountability, and bureaucratic quality are below their average value in Nigeria, suggesting weak institutions. Three, the study applies an estimation technique that captures time variation, since policy prescriptions tend to differ based on the time horizon. Precisely, the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) is used to examine both the short- and long-run effects of diaspora remittances and institutions on self-employment in Nigeria. The study’s outcome provides valuable insights for policymakers and the literature by harnessing the potential of remittances in financing self-employment. It also identifies points of concern in institutions and provides suggestions for addressing them.

The preceding section considers the research question and the study’s objective, among others. The subsequent sections, including the literature review, data and methods, discussion and empirical findings, and conclusion and policy recommendations, are addressed in sections 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Theoretical Review

The study connects with the new economics of labour migration. The theory suggests that decisions to migrate within any household are often driven by the motivation that migrants will remit money back home (Lucas & Stark, 1985). Remittances are intended to mitigate or reduce whole-family income constraints or serve as income insurance for those at home (Taylor, 1999). Taylor also establishes the importance of remittances as a positive tool for economic development. However, institutions are still considered a limitation to the effectiveness of remittances’ potential in emerging economies such as Nigeria. This may be why remittances are channeled more towards consumption (Chrysostome & Nkongolo-Bakenda, 2019; Dada & Akinlo, 2023) than towards employment generation, business creation, or the expansion of existing enterprises in developing economies. This theory predicts that such remittances should drive investment in migrants’ home countries; however, little has been realized due to weak economic policies.

The new economics of labour migration could be more effective when combined with institutional theory to address the issue of self-employment in developing nations. In this light, institutional theory represents the ‘rules of the game’ (North, 1991), which either encourage or dissuade diasporans from remitting, noting that creating an enabling environment for self-employed business activities to operate is crucial. It can further strengthen new economics of labour migration, confirming that an institutional framework can shape the scope and efficacy of interventions (OECD/ERIA, 2018), such as diaspora remittances.

2.2 Empirical Review

Past studies have lamented that self-employment has not yielded significant improvements in the overall employment rate, despite efforts in entrepreneurship education (Premand et al., 2016). A poor self-employment culture is sometimes linked to a lack of financial resources or weak institutions. For instance, strong institutions often play a significant role in driving economic growth, as former President Obama of the United States noted during his 2009 visit to Ghana (Chrysostome & Nkongolo-Bakenda, 2019). In practice, such institutions can encourage self-employment in emerging economies. A key component of employment is self-employment. However, limited paid employment openings often bedeviled and reduced job opportunities, as observed in the East African labour market, aside from insufficient finance to start new businesses (Goshu, 2020).

According to Goshu (2020), self-employment is defined as working for oneself instead of being employed in a paid position. According to Diez and Ozdagli (2011, p. 1), “Self-employment is viewed as the portion of employers or employed workers in the country’s entire workforce.” In this case, people find employment in their profession, trade, or business, exercising control and independence in their work choices while bearing business-related risks. In the opinion of Wynn (2016), self-employed individuals have a contract of rendering services to clients, which differs from those in employment who have a contract of service with their employers. Similarly, the OECD (2016) views self-employment as those working in their own business, either as unincorporated or own-account employees (without employees), whose remuneration is based on profits from goods and services produced, including their consumption. However, Hammed (2018) raises concerns that corruption in offices and unstable government politics impede self-employment in Africa, including Nigeria.

Ainembabazi and Kemeze (2022) establish a connection between remittances and the employment of household members in family-owned businesses in Nigeria and Uganda. However, the number of employed family members decreases with increased remittances, resulting in a higher proportion of non-family workers being engaged as remittances increase. Despite that, Funkhouser (1992) confirms that the possibility of self-employment tends to grow in remittance-receiving households. This contradictory trajectory is problematic; however, what accounts for the decline in households’ interest in prompting more family members to invest such funds in family-owned businesses remains unclear.

Proneness to migration is not common among self-employed people, as highlighted in Giambra and McKenzie (2021); however, it may be that remittances, as a form of finance and institutions, support this idea. However, it is never mentioned in the study. It entrenches only the importance of self-employment in any economy. In Uzbekistan, Kakhkharov (2018) confirms that diasporans often send money to support their home business projects. Noting this, the recipient’s family will only be encouraged when there are other income or savings to supplement the remittance.

The study by Goshu (2020) confirms that government quality, including stable politics, control of corruption indices, voice and accountability, and economic indicators such as electricity access and enrollment in primary education, has a significantly positive effect on East African self-employment. However, industrial employment and growth in real GDP show a negative relationship. The source of finance is not disclosed to determine whether it is exposed to any challenge. Nyame-Asiamah et al. (2020) affirms the paradoxical stance of the institutional framework, establishing that it could serve as both a push and pull factor in entrepreneurship. This indicates that institutions have the potential to either discourage or stimulate self-employment. Dada et al. (2024a) also demonstrate that institutions are crucial for diasporans to remit funds to their home country. Migrants’ decisions to remit could be enhanced where institutions complement each other.

The impact of remittances on investment is confirmed in the study of Mohammed and Karagöl (2023). However, to drive investment in Sub-Saharan Africa, a substitutional linkage between remittances and institutions was established. This diminishes the role of institutions, indicating a reduced use of remittances in promoting investment due to weak institutions in the region. This single-country study adds another dimension to this position. Also, contrary to Mohammed and Karagöl’s study, three estimation techniques are used for sensitivity analysis, which strengthens the robustness of the results from the current study.

The tendency for households to engage in self-employment diminishes with the regular receipt of remittances (Salman, 2016). Salia et al. (2022) highlight that Africa’s interest in diaspora remittances is to smooth household consumption and augment the government’s balance of payments. Nonetheless, the welfare of recipient families improved along this line, confirming that most households used the received money for consumption. This contradicts diasporans’ willingness to return to their country to start their own business (McCormick & Wahba, 2001).

Concerning the relationship between institutions and self-employment, studies have shown that improved economic freedom within an institution increases the likelihood of self-employment preferences among both existing self-employed individuals and latent entrepreneurs (Gohmann, 2012). In line with this thought, the study confirms a more significant effect for those currently engaged in self-employed business activities within such institutions. This resonates with the belief that institutions will promote self-employment in any economy, including Nigeria. In line with this, assessing the actual conditions of the institution and the perception and awareness levels among labour market actors, including self-employed business owners, is essential to policymaking (Bögenhold et al., 2024; Olubodun et al., 2025). The relevance of institutions to self-employment is somewhat chronicled. Institutions are game rules that govern or guide formal and informal endeavour (North, 1991). This reaffirms institutions’ ability to redefine anyone’s interest and desire to start a business in the shadow or formal economies.

The study by Nyström (2008) establishes a tendency for increased self-employment in areas with a minimal government sector, an improved judicial structure, and secure property rights, accompanied by limited credit regulation, labour market flexibility, and enterprise development. Less credit regulation is likely to create room for financing; however, this is doubtful in developing nations, such as Nigeria. The perception is that funds received from other sources, such as remittances, will be poorly accounted for and subject to corruption, making any funds not raised from their account insecure. However, studies in the West (see Bögenhold et al., 2024; Nyström, 2008) have focused on regional economies which differ from the single-country evidence presented in this study.

In the Eurozone, the failure of early self-employed entrepreneurs is linked to macroeconomic factors and institutions, with a negative correlation between the quality of formal institutions, entrepreneurial culture, and social norms (Del Olmo-García et al., 2020). On the contrary, successful entrepreneurs who leverage environmental support are highly respected. They confirm the paradoxical stance of Nyame-Asiamah et al. (2020), which posits that institutions either contribute to or hinder the survival of self-employed businesses. Institutional roles cannot be determined solely on face value unless empirical evidence is applied to unveil the underlying dynamics that shape institutions. It is hypothesized that:

H1: Diaspora remittances and institutions have a significant effect on self-employed business activities in Nigeria.

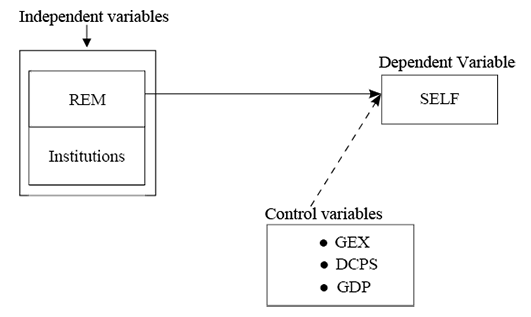

Figure 1 presents the authors’ conceptualization of the relationship among the variables in the study.

Figure 1

Conceptual Model

3. Data and Methods

3.1 Data

The Nigerian annual time series data set spanning from 1991 to 2020 was utilized in the study. The availability of data for the core variables guides the study’s time frame. Using Nigerian data for the study is more appropriate and strategic. In Sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria leads the list of countries receiving foreign remittances, with $20.98 billion received in 2024 (World Bank, 2024). Nigeria received more than 40% of the remittances inflow into the Sub-Saharan African countries. Furthermore, the country’s institutional architecture is relatively weak, allowing sharp practices and opportunistic behaviour among various economic agents. However, despite the vast volume of remittances inflow, many of Nigeria’s growing population still wallow in poverty.

The measurement of variables includes percentages of total employment and GDP, as well as employee compensation and personal transfers for the self-employed and diaspora remittances, respectively. Institutional quality is generated from an average of five indices: corruption control, law and order, government stability, bureaucracy quality, and democratic accountability. Details of how this index is constructed are presented in the Appendix. Other control variables include government expenditure, calculated as a percentage of GDP, domestic credit to the private sector, and per capita income. Data on self-employed individuals, diaspora remittances, government expenditure, domestic credit to the private sector, and per capita income are extracted from the World Bank’s Development Indicators. Institutional quality data are obtained using the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG).

3.2 Model Specification

This study investigates the linkages between diaspora remittance, institutions, and self-employed business activities in Nigeria. The general functional form of the specific self-employed activities model is expressed in Equation 1 as follows:

SELF = f(REM, INS, X) (1)

where SELF, REM, and INS are self-employed business activities, diaspora remittances, and institutional quality. X is another control variable that influences self-employed business activities.

These variables are transformed into a logarithmic model since log-linear models are more consistent and reliable than linear models. Thus, Equation 1 is stated in its specific form:

lnSELF = α + βlnREM + γlnINS + δlnGEX + ζlnDCPS + ηlnGDP + ε (2)

where GEX, DCPS, and GDP represent government expenditure, domestic credit to the private sector, and per capita income, respectively, which are used as the control variables in the study. ln is the logarithmic form, and ε is the unobserved random term, which is normally distributed. From Equation 2, the positive (negative) and significant coefficients of the independent variables suggest that the variable increases (decreases) self-employment business activities in Nigeria.

3.3 Estimation Technique

Based on the stationarity properties of time series data, which are usually I(0) and I(1), the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) is used as the baseline estimation technique. This approach benefits the study by accommodating I(0) and I(1) variables and providing both the short- and long-run estimates of the parameters. Similarly, ARDL resolves the endogeneity problem by using the lag of the dependent variable (Fabiyi & Dada, 2017; Ahmed et al., 2019; Arnaut et al., 2023). Lastly, this technique offers policy variation in both the short and long term. The ARDL is expressed in Equation 3:

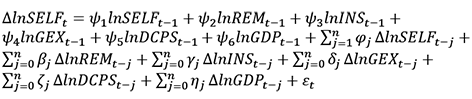

(3)

(3)

From Equation 3, n is the optimal lag length chosen using the SIC. ∆ is the change operator, ψj (j = 1, 2…, 3) is the long-run estimate; φj, βj, γj, δj, ζj ∧ ηj are the short-run estimates. The null hypothesis of no cointegration among the series is specified as H0 : ψj = 0, and verified against the alternative hypothesis of H1 : ψj ≠ 0. Using the Pesaran et al. (2001) approach, the F-statistic is compared to the lower and upper bounds of the critical values. No conintegration hypothesis is valid if the F-calculated is below the lower bound. Otherwise, the alternative of cointegration is accepted, as indicated by the F-statistic being above the upper critical bound, which signifies a long-run relationship between the variables. Nevertheless, the result is inconclusive if the F-calculated value lies between the lower and upper bounds.

Apart from the ARDL, other long-run estimates, such as canonical cointegrating regression (CCR), dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS), and fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS), are used for sensitivity analysis. The models for these cointegrations are not stated due to space constraints.

4. Discussion of Empirical Findings

Before discussing the results from the model estimates, it is essential to scrutinize the descriptive and statistical characteristics of the dataset employed in the study. The descriptive statistics and pairwise correlation between the variables are shown in Table 1. The mean value of self-employment is 82.951, which is a bit greater than the median value. This suggests that the distribution of self-employment in Nigeria is positively skewed, a finding also reinforced by the skewness statistic. The Jarque-Bera statistics for self-employment also show that it is normally distributed. The mean value of diaspora remittance during the period under study is 3.564, with minimum and maximum values of 0.118 and 8.312, respectively.

Furthermore, diaspora remittance is positively skewed, with a peak of 1.684. Similarly, institutional quality is evenly distributed, with mean and median values of 4.108 and 4.201, respectively. In addition, other variables, such as government expenditure, domestic credit to the private sector, and per capita income, have mean values of 94.801, 11.089, and 1913.605, respectively. Likewise, the average values of these control variables fall between their minimum and maximum values. The Jarque-Bera statistic suggests the series is evenly distributed.

The kurtosis statistic is also employed to examine the distribution’s peakness or evidence of outliers. The results in Table 1, as indicated by the kurtosis statistic, suggest that self-employment, remittances, and per capita income are platykurtic, as their values are less than three. On the other hand, institutions, government expenditure, and domestic credit to the private sector are leptokurtic since their value are less than three. However, none of the variables is mesokurtic. The outcome of the kurtosis shows the absence of outliers in the dataset.

At the lower part of Table 1, the correlation shows that the variables are moderately correlated. Thus, the postulation of multicollinearity or near multicollinearity between the series can be discarded. Hence, multicollinearity does not present any risk to our model estimates. Regarding the direction of the correlation, all the variables positively correlate with self-employment, and their coefficients are significant.

Table 1

Descriptive and Correlation Matrix

|

SELF |

REM |

INS |

GEX |

DCPS |

GDP |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean |

82.951 |

3.564 |

4.108 |

94.801 |

11.089 |

1913.605 |

|

Median |

82.395 |

3.849 |

4.201 |

93.874 |

9.395 |

1888.825 |

|

Maximum |

85.066 |

8.312 |

4.611 |

111.267 |

22.289 |

2563.900 |

|

Minimum |

81.151 |

0.118 |

3.417 |

76.949 |

5.241 |

1348.681 |

|

Std. Dev. |

1.447 |

2.425 |

0.292 |

7.362 |

4.271 |

464.658 |

|

Skewness |

0.273 |

0.116 |

-0.697 |

0.096 |

0.881 |

0.074 |

|

Kurtosis |

1.339 |

1.684 |

3.011 |

3.470 |

3.203 |

1.346 |

|

Jarque-Bera |

3.823 |

2.232 |

2.426 |

0.322 |

3.936 |

3.448 |

|

Probability |

0.148 |

0.328 |

0.297 |

0.851 |

0.140 |

0.178 |

|

SELF |

1 |

|||||

|

REM |

0.537*** (0.000) |

1 |

||||

|

INS |

0.002* (0.091) |

0.155** (0.041) |

1 |

|||

|

GEX |

0.339* (0.067) |

0.246 (0.190) |

0.090 (0.635) |

1 |

||

|

DCPS |

0.420*** (0.000) |

0.651*** (0.000) |

0.068 (0.720) |

0.329* (0.075) |

1 |

|

|

GDP |

0.341*** (0.000) |

0.525*** (0.000) |

0.067 (0.726) |

0.438** (0.015) |

0.530*** (0.000) |

1 |

Note. SELF is self-employed, REM is remittance, INS is institutional quality, GEX is government expenditure, DCPS is domestic credit to the private sector, and GDP is per capita income. ( ) is the probability value, *, ** and *** represent 10%, 5% and 1% level of significance, respectively.

In addition to the descriptive statistics, the econometric characteristics of the variables are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Table 2 presents the stationarity properties of the variables. Two estimation approaches are used to investigate these stationarity properties – Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Philip and Perron (PP) unit root tests. The results of the ADF and PP unit root tests suggest that all the series possess a unit root at the level; however, they become stationary at the first difference. This hints that the series is integrated of order one (I(1) variables). The stationarity of the variables at first difference gives the likelihood of long-run cointegration between the variables.

To account for the evidence of long-run cointegration, the Johansen cointegration test and ARDL bounds testing are used, and their results are displayed in Tables 3 and 4. According to Table 3, the Johansen cointegration test indicates evidence of at most three cointegration equations. Similarly, the ARDL bounds test in Table 4 also established the evidence of a long-run relationship among the variables, with the significant value of the F-statistic (7.229) greater than the upper bound critical value. Cointegration and long-run relationships indicate that, although the variables tend to diverge in the short run, they converge to a steady state in the long run.

Table 2

Unit Root Test

|

Variables |

ADF |

PP |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Level |

Difference |

Level |

Difference |

|

|

T-Stat. |

T-Stat. |

T-Stat. |

T-Stat. |

|

|

SELF |

-1.219 |

-3.231** |

-1.120 |

-3.175** |

|

REM |

-1.872 |

-5.538*** |

-1.812 |

-7.752*** |

|

INS |

-1.784 |

-3.347*** |

-1.783 |

-3.481*** |

|

GEX |

-1.652 |

-7.948*** |

-2.527 |

-11.754*** |

|

DCPS |

-2.107 |

-4.186*** |

-1.738 |

-6.059*** |

|

GDP |

-1.577 |

-5.300*** |

-1.262 |

-6.306*** |

Note. ** and *** represent 5% and 1% levels of significance.

Table 3

Cointegration Test

|

Hypothesized |

Eigen |

Trace |

5% Critical |

Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

None |

0.815 |

156.344 |

95.753 |

0.000*** |

|

At most 1 |

0.754 |

109.042 |

69.818 |

0.000*** |

|

At most 2 |

0.679 |

69.707 |

47.856 |

0.000*** |

|

At most 3 |

0.622 |

37.890 |

29.797 |

0.004*** |

|

At most 4 |

0.266 |

10.632 |

15.494 |

0.235 |

|

At most 5 |

0.067 |

1.946 |

3.841 |

0.163 |

Note. *** denotes a 1% level of significance.

Table 4

ARDL Bounds Testing for Cointegration

|

Model |

Optimum Lag |

F-statistic |

|---|---|---|

|

lnSELF = f(lnREM, lnINS, lnGEX, lnDCPS, lnGDP) |

(1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 3) |

7.229*** |

|

Significance level |

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|

10% |

2.26 |

3.35 |

|

5% |

2.62 |

3.79 |

|

1% |

3.41 |

4.68 |

Note. *** represents significance at 1%.

The short-run and long-run estimates of the coefficients of the error-correction version of ARDL (1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 3) are reported in Table 5. The coefficient of the error-correcting term (ECT) is significant and negative, thus reaffirming the evidence of long-run linkages among the series. The significant value of the ECT suggests that, though the variables tend to diverge in the short term, they return to their long-run steady-state equilibrium annually by 51.1%. The short-run coefficient of diaspora remittance on self-employment is significantly positive, with a coefficient of 0.148. This result reveals that diaspora remittances benefit small business expansion in the short term by easing the financial constraints available for investment and consumption. Similarly, this aligns with the New Economics of Labour Migration proposition that low-income households or those vulnerable to shocks use migration as a coping strategy to mitigate shocks (Stark & Bloom, 1985). The findings from this short-run result corroborate the conclusions of studies in Latin America and the Caribbean countries (Kshetri et al., 2015), Nepal (Devkota, 2016; Adhikari, 2017), Uzbekistan (Kakhkharov, 2018), and Nigeria (Kotorri et al., 2020; Akinlo & Dada, 2022).

However, in the long run, the influence of diaspora remittance on self-employment is significantly negative. This result indicates that diaspora remittances are primarily used for immediate consumption in the long run, which does not translate to long-term employment generation in Nigeria. As documented by Zheng and Musteen (2018), remittance has a positive impact on necessity entrepreneurs and a negative impact on opportunity entrepreneurs because the former require little capital for start-up, while the latter involve a significant amount of capital for creativity and innovation. Furthermore, studies (see Dada & Akinlo, 2023; Ajide et al., 2021; Ajide & Osinubi, 2020; Laniran & Adeniyi, 2015) have shown that remittance, basically in developing countries like Nigeria, contributes to consumption and poverty reduction in recipient countries, but does not result in wealth creation and productive activities. The negative impact of diaspora remittances on self-employment is related to similar works by Chami et al. (2005), Shapiro and Mandelman (2016), Ajide and Osinubi (2020), and Asiedu and Chimbar (2020).

The influence of institutional quality on self-employment is significantly negative in both periods. Specifically, in the short term, remittance (lags 1 and 2) has a coefficient of -0.994 and -0.589, respectively, while in the long run, the coefficient is -0.165. This finding suggests that institutional quality in Nigeria is not conducive to self-employment. Additionally, it indicates that the level of institutional development is weak and does not provide an enabling environment for employment creation. Institutional mechanisms, including corruption control, bureaucratic quality, rule of law, democratic accountability, and government stability, remain low, as indicated by the average value of the institution index in Table 1. This negatively affects the operations of small-scale businesses and self-employment. For instance, corruption affects the effective functioning of business law and regulation, which in turn increases the bureaucratic procedures in implementing government policies regarding employment creation.

Furthermore, a weak rule of law reduces the confidence and participatory level of economic agents in an economy. In addition, weak institutions lead individuals and households to seek funds through self-financing, especially from friends and family living abroad (Plaza et al., 2011; Bjuggren & Dzansi, 2008). In addition, weak institutions limit the opportunities available to entrepreneurs and fail to support their interest in creating a favorable business environment (Elert & Henrekson, 2020; Dada et al., 2024b). Similar studies (such as Ajide & Osinubi, 2020; Dada & Fanawopo, 2020; Chrysostome & Nkongolo-Bakenda, 2019; Ajide & Aderemi, 2014) have shown that most developing countries tend to have poor institutional quality, which retards the growth process. Furthermore, the empirical study by Fredstrom et al. (2021) demonstrates that governance quality has a negative impact on entrepreneurial activity. Likewise, LêKhang and Thành (2018) and Fuentalsaz et al. (2015) obtained a negative connection between institutions and entrepreneurship. On the other hand, Harbi and Anderson (2010) found that investment freedom as a measure of institutional quality boosts the self-employment rate. Similarly, Herrera-Echeverri et al. (2014), Crnogaj and Hojnik (2016), and Aparicio et al. (2016) found that strong institutional quality is beneficial to entrepreneurship activity.

On the other hand, government spending (GEX) had a significantly positive impact on self-employment generation in both periods. A percentage rise in government expenditure increases self-employment by 0.023% and 0.094% in the short and long run, respectively. This result indicates that government spending has a positive impact on employment creation in Nigeria. However, domestic credit to the private sector negatively impacts self-employment in the short run. In contrast, the long-run effect is not significant. This implies that a percentage rise in domestic credit to the private sector reduces self-employment by 0.043% in the short run. As documented by Vaaler’s (2013) study, remittances should strengthen and make the financial environment more conducive to entrepreneurship. However, studies (Dada & Akinlo, 2023) in developing countries have shown that most remittances are not retained in the financial sector and thus have a limited contribution to entrepreneurship development. This result is not surprising as most empirical studies in Nigeria have established the presence of loopholes and lapses in the financial system (Olaniyi et al., 2023; Abanikanda & Dada, 2023). Additionally, the country’s institutional framework enables sharp practices and the diversion of funds from the productive sector (Olaniyi et al., 2023).

Similarly, per capita income (economic growth) has a positive and significant influence on the growth of self-employment in both periods. However, the result shows a time lag before economic growth can improve self-employment. This result highlights the significance of income/ economic growth in fostering self-employment in Nigeria. This conclusion supports the empirical postulation of Yavuz and Bahadir (2022) that economic growth increases entrepreneurship in developing countries. However, Ajide and Osinubi (2020) found the negative impact of income on enterprise creation in Africa.

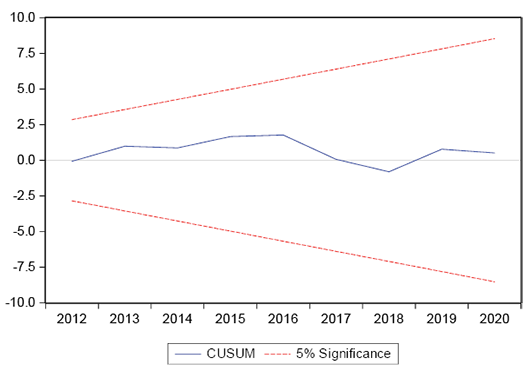

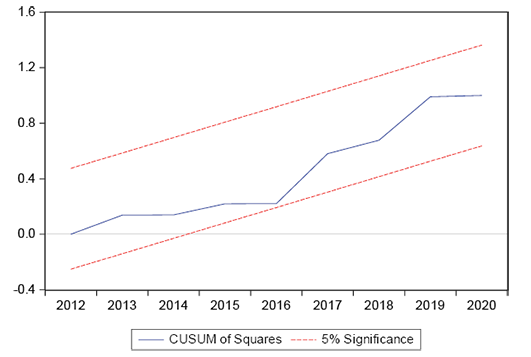

The stability of the model parameters is also validated using the cumulative sum (CUSUM) and the cumulative sum of squares (CUSUMSQ), as shown in Figures 2 and 3. The findings from the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ imply that the model and estimated parameters are stable, as their values fall within the 5% critical values. Furthermore, other diagnostic tests are used to validate the result of the ARDL. The results reported in the lower part of Table 5 indicate that the model does not exhibit heteroscedasticity problems, serial correlation, or multicollinearity. Thus, the results obtained from the estimates can be used for policy inference.

Table 5

Estimate using ARDL (1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 3): Dependent Variable SELF

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

t-statistic |

Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Short Run |

|||

|

∆REM |

0.148** |

2.682 |

0.025 |

|

∆INS |

0.212 |

1.347 |

0.211 |

|

∆INS(-1) |

-0.994*** |

-4.738 |

0.001 |

|

∆INS(-2) |

-0.589** |

-3.186 |

0.011 |

|

∆GEX |

0.023** |

3.007 |

0.014 |

|

∆DCPS |

0.017 |

0.899 |

0.391 |

|

∆DCPS(-1) |

-0.043* |

-2.034 |

0.072 |

|

∆GDP |

0.001 |

0.355 |

0.731 |

|

∆GDP(-1) |

0.002* |

1.856 |

0.096 |

|

∆GDP(-2) |

0.003** |

2.496 |

0.034 |

|

∆@trend |

0.074** |

2.426 |

0.038 |

|

Ect(-1) |

-0.511*** |

-3.293 |

0.001 |

|

Long Run |

|||

|

REM |

-0.188*** |

-3.826 |

0.004 |

|

INS |

-0.165* |

-2.097 |

0.066 |

|

GEX |

0.094** |

2.357 |

0.042 |

|

DCPS |

-0.034 |

-1.014 |

0.337 |

|

GDP |

-0.001 |

-0.628 |

0.545 |

|

C |

5.549*** |

18.783 |

0.000 |

|

@trend |

-0.145** |

-2.852 |

0.019 |

|

Diagnostic Test |

|||

|

J-B normality test |

0.361 |

0.701 |

|

|

B-G serial correlation LM test |

3.189 |

0.214 |

|

|

ARCH test |

0.721 |

0.384 |

|

|

Ramsey |

0.154 |

0.492 |

Note. ***, **, * represent 1%, 5% and 10% significance, respectively.

Figure 2

CUSUM

The accuracy of the long-run estimates is verified using the FMOLS, DOLS, and CCR methods. Tables 6, 7, and 8 show the sensitivity analysis results. The results from these methodologies are similar to the long-run estimates obtained using the ARDL methodology. Thus, it could be inferred that the long-run estimated coefficients are reliable and stable. Specifically, the coefficient of diaspora remittance in all the estimates is negative and statistically significant, with coefficients ranging from 0.193 to 0.232. Nevertheless, the coefficient of institutional quality is significantly positive at 10 percent in FMOLS and CCR estimates. Furthermore, government expenditure and per capita income increasingly impact self-employment, respectively. Moreover, the results also established a negative and significant impact of domestic credit on the private sector’s self-employment in Nigeria.

Figure 3

CUSUM of Squares

Table 6

Robustness Estimate Using FMOLS: Dependent Variable SELF

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

t-statistic |

Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

|

REM |

-0.193*** |

-6.431 |

0.000 |

|

INS |

0.454* |

1.746 |

0.072 |

|

GEX |

0.007 |

1.018 |

0.319 |

|

DCPS |

-0.050*** |

-2.989 |

0.006 |

|

GDP |

0.002*** |

10.784 |

0.000 |

|

C |

5.349 |

5.342 |

0.000 |

|

Adj. R-sq |

0.948 |

||

|

Long run variance |

0.063 |

||

|

Mean dep. variance |

82.878 |

||

|

SE of Reg. |

2.386 |

Note. ***, * represent 1% and 10% significance, respectively.

Table 7

Robustness Estimate Using DOLS: Dependent Variable SELF

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

t-statistic |

Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

|

REM |

-0.232*** |

-10.729 |

0.000 |

|

INS |

0.103 |

0.428 |

0.690 |

|

GEX |

-0.013 |

-1.880 |

0.133 |

|

DCPS |

-0.087** |

-4.201 |

0.014 |

|

GDP |

0.001** |

4.186 |

0.014 |

|

C |

8.129 |

12.467 |

0.000 |

|

Adj. R-sq |

0.996 |

||

|

Long run variance |

0.002 |

||

|

Mean dep. variance |

82.849 |

||

|

SE of Reg. |

0.024 |

Note. ***, ** represent 1%, and 5% significance, respectively.

Table 8

Robustness Estimate Using CCR: Dependent Variable SELF

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

t-statistic |

Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

|

REM |

-0.198*** |

-6.008 |

0.000 |

|

INS |

0.467* |

1.854 |

0.062 |

|

GEX |

0.004 |

0.461 |

0.649 |

|

DCPS |

-0.048** |

-2.741 |

0.012 |

|

GDP |

0.002*** |

10.436 |

0.000 |

|

C |

5.538*** |

7.680 |

0.000 |

|

Adj. R-sq |

0.947 |

||

|

Long run variance |

0.064 |

||

|

Mean dep. variance |

82.878 |

||

|

SE of Reg. |

2.446 |

Note. ***, ** and * represent 1%, 5% and 10% significance, respectively.

5. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

The paper examines the relationship between remittances and institutional quality in Nigeria from 1991 to 2020 as well as their impact on self-employment. As an estimation technique, the autoregressive distributed lags (ARDL) model is employed to examine both the short- and long-run effects. FMOLS, DOLS, and CCR (the other cointegration regressions) are utilized to validate the long-run estimates.

In the short run, the empirical outcome indicates that diaspora remittances, government expenditure, and per capita income positively influence self-employment, whereas domestic credit to the private sector has a negative impact. Yet, the effect of institutions on self-employment is not significant. In the long run, however, diaspora remittances and domestic credit to the private sector have a negative impact on the growth of self-employment. In contrast, government expenditure and per capita income significantly contribute to the growth of self-employment in Nigeria. This result indicates that diaspora remittances do not lead to long-term self-employment creation due to poor institutional quality, which hinders business start-ups. Weak economic and political institutions could lead recipients of diaspora remittances to use them for immediate consumption, thereby negatively impacting long-term investment and employment generation.

These empirical outcomes have important policy implications that can help policymakers in Nigeria and other developing countries. Policymakers in the region must fortify the institutional environment so diasporans can be incentivized to remit. Diasporans living in the developed world are used to strong institutional quality; hence, institutions’ indicators, e.g., improved bureaucratic quality, enforcement of contracts, property rights, reduction in the cost of business start-up, and transparency in government activity should be strengthened, as they motivate them to remit and invest in the economy through enterprise creation and self-employment. Furthermore, policymakers should prioritize value reorientation, especially in building trust and promoting collaboration between diasporans and their home countries. The Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NiDCOM) can be utilized in reorientation, enhancing the confidence of the diasporans to remit.

Promoting fintech-enabled remittances (Sohst, 2024) can reduce costs, boost employment generation, and contribute to long-term economic growth by increasing the amount remitted to the country. Similarly, lowering the cost of sending remittances will enable it to be channeled through the financial sector, leveraging fintech, rather than the informal channel (shadow economy). On the other hand, the financial sector, which is responsible for transferring diaspora remittances, will facilitate the creation of cost-effective and reliable products and services for remittance beneficiaries, enabling new business creation. Further, remittances could be used to increase available credit to the bank for business activities in Nigeria.

While this study makes significant policy contributions to the literature, it is not without limitations, including its single-country focus, which future studies will address. The scope of the study is limited to the period 1991–2020 due to the availability of data on the essential variables of the study. Future studies should overcome this limitation as reliable data become readily available. The research output can be complemented by investigating the link at the microeconomic level. Including other political and social variables will be useful when examining the determinants of self-employment. Lastly, this study can be extended to other developing nations.

Appendix

Institutional Index

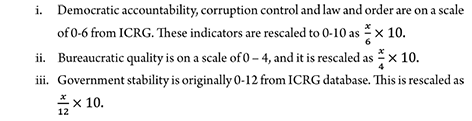

This study follows the approach of Dada et al. (2025b), Dada et al. (2024a), Olaniyi and Adedokun (2022), and Aluko and Ibrahim (2020) to generate the institutional index. The process of rescaling the five indicators on an ordinal scale of 0–10 is described as follows:

where x is the score obtained from each of the indicators, out of the maximum point. Afterward, the five indicators are average to generate an index of institutional quality as

INS is the aggregate institutional quality index, n is the number of institutional quality measures, j denotes each individual institutional quality index, and t is the time series observations.

References

Abanikanda E. O., & Dada J. T. (2023). External Shocks and Macroeconomic Volatility in Nigeria: Does Financial Development Moderate the Effect? PSU Research Review.https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-07-2022-0094

Adhikari, N. (2017). Linkage between labor migration, remittance and self employed business activities in Nepal. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Economic Issues, 1(1), 39–51.

Ahmed, Z., Wang, Z., Mahmood, F., Hafeez, M., & Ali, N. (2019). Does globalization increase the ecological footprint? Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26, 18565–18582.

Ainembabazi, J. H., & Kemeze, F. H. (2022). Remittances and employment in family-owned firms: Evidence from Nigeria and Uganda (Working Paper Series N° 366, African Development Bank, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire).

Ajide, F. M, Osinubi, T. T., & Dada J. T. (2021). Economic Globalization, Entrepreneurship, and Inclusive Growth in Africa. Journal of Economic Integration, 36(4), 689–717.

Ajide, F. M., & Aderemi, A. A. (2014). The effects of earnings management on dividend policy in Nigeria: An empirical note. Financial & Business Management, 2(3), 145–152.

Ajide, F. M., & Osinubi, T. T. (2020). Foreign aid and entrepreneurship in Africa: The role of remittances and institutional quality. Economic Change and Restructuring, 55, 193–224, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-020-09305-5

Akinlo T., & Dada J. T. (2022). Remittances–Financial Development–Poverty Reduction in Sub-Saharan African. Iranian Economic Journal, 29(1),50–85. https://doi.org/10.22059/IER.2023.92229

Aluko, O. A., & Ibrahim, M. (2020). Institutions and the financial development–economic growthnexus in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Notes, 49(3), e12163. doi: 10.1111/ecno.12163

Aparicio, S., Urbano, D., & Audretsch, D. (2016). Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technolological Forecasting and Social Change, 102, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.04.006

Arnaut, M., Dada, J. T., Sharimakin, A., & Al-Faryan M. A. S. (2023). Does environmental quality respond (a)symmetrically to (in)formal economies? Evidence from Nigeria. Society and Business Reviews, 18(4), 646–667.

Asiedu, E., & Chimbar, N. (2020). Impact of remittances on male and female labor force participation pat-terns in Africa: Quasi-experimental evidence from Ghana. Review of Development Economics, 24, 1009–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12668

Bjuggren, P. O., & Dzansi, J. (2008). Remittances and investment. In 55th Annual Meetings of the North American Regional Science Association International, New York, November, 2008.

Bögenhold, D., O’Hagan-Luff, M., Parastuty, Z., & Van Stel, A. (2024). Perceptions of the Self-employed and Wage-employed regarding Institutional Conditions affecting Entrepreneurship. In Research Handbook on Self-Employment and Public Policy (pp. 282–295). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800881860.00024

Chami, R., Fullenkamp, C., & Jahjah, S. (2005). Are Immigrant Remittance flows a source of Capital for Development?. IMF Staff papers, 52(1), 55–81.

Chrysostome, E., & Nkongolo-Bakenda, J. M. (2019). Diaspora and international business in the homeland: From impact of remittances to determinants of entrepreneurship and research agenda. In M. Elo & I. Minto-Coy (Eds.), Diaspora networks in international business: Perspectives for understanding and managing diaspora business and resources (17–39). Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2019.

Crnogaj, K., & Hojnik, B. B. (2016) Institutional determinants and entrepreneurial action. Management, 21, 131–150.

Dada, J. T., & Akinlo, T. (2023). Remittances-Finance-Growth Trilogy: Do Remittance and Finance Complement or Substitute Each other to Affect Growth in Nigeria? Economic Annals, 68(236), 105–138 https://doi.org/10.2298/EKA2336105D

Dada J. T. & Fanowopo O. (2020). Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction: The Role of Institutions. Ilorin Journal of Economic Policy, 7(1), 1–15.

Dada J. T., Awoleye E. O, Al-Faryan M. A. S., & Tabash M.I. (2024a). The Absorptive Capacity of the institution in the link between Remittances and Financial Development in Africa: An Advance Panel Regression. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 17(3), 533–456. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFEP-02-2024-0058

Dada J. T., Ajide F. M., Arnaut M., & Al-Faryan M. A. S. (2024b). The moderating roles of economic complexity in the entrepreneurship-sustainable environment nexus for the Gulf Cooperation Council economies. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 30(4), 3395–3410 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.3069

Dada J. T., Awoleye E. O., Tabash M. I., Samrat R., & Al-Faryan M. A. S. (2025b). The criticality of institutions in the link between natural resources rents and informal economy: Insight from a panel of African countries. Mineral Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-025-00515-9

Dada, J. T., Ajid,e F. M., Tabash M. I., Samrat, R., & Al-Faryan, M. A. S. (2025a). Enterprise creation for sustainable environment: The criticality of financial development in African economies. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, Forthcoming https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-11-2024-0238

Del Olmo-García, F., Crecente, F., & Sarabia, M. (2020). Macroeconomic and institutional drivers of early failure among self-employed entrepreneurs: An analysis of the euro zone. Economic Research-Ekonomska istraživanja, 33(1), 1830–1848. DOI: 10.1080/1331677X.2020.1754268

Devkota, J. (2016). Do return migrants use remittances for entrepreneurship in Nepal. Journal of Economic Development Studies, 4(2), 90–100.

Díez, F. J., & Ozdagli, A. K. (2011). Self-Employment in the Global Economy (Working Paper, No. 11-5, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Boston, MA). https://hdl.handle.net/10419/55621

Elert, N., & Henrekson, M. (2021). Entrepreneurship prompts institutional change in developing economies. The Review of Austrian Economics, 34, 33–53.

El Harbi, S., & Anderson, A. R. (2010). Institutions and the shaping of different forms of entrepreneurship. The Journal of Socio-economics, 39(3), 436–444.

Fabiyi, R. O., & Dada, J. T. (2017). Fiscal Deficit and Sectoral Output in Nigeria. American Journal of Social Sciences, 5(6), 41–46.

Fredstrom, A., Peltonen, J., & Wincent, J. (2021) A Country-level Institutional Perspective on Entrepreneurship Productivity: The Effects of Informal Economy and Regulation. Journal Business Venturing, 36(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106002

Fuentalsaz, L., Gonzalezm, C., Maicas, J. P., & Montero, J. (2015). How different formal institutions afect opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 18(4), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2015.02.001

Funkhouser, E. (1992). Migration from Nicaragua: Some Recent Evidence. World Development, 20(8), 1209–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(92)90011-J

Giambra, S., & McKenzie, D. (2019). Self-Employment and Migration (World Bank Group, Development Economics Development Research Group, Policy Research Working Paper 9007, 1–72).

Giambra, S., & McKenzie, D. (2021). Self-employment and Migration. World Development, 141, 105362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105362

Gohmann, S. F. (2012). Institutions, Latent Entrepreneurship, and Self‐Employment: An International Comparison. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 36(2), 295–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00406.x

Goshu, F. B. (2020). The Effects of Government Quality and Economic Indicators on Self-employment in East Africa: Panel Data Analysis. Research Square, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-33950/v1

Herrera-Echeverri, H., Haar, J., Estévez-Bretón, J. B. (2014). Foreign direct investment, institutional quality, economic freedom and entrepreneurship in emerging markets. Journal of Business Research, 67(9),1921–1932.

Harbi, S. E., Anderson, A. R. (2010) Institutions and the shaping of different forms of entrepreneurship. Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 436–444.

Herrera-Echeverri, H., Haar, J., & Estévez-Bretón, J. B. (2014). Foreign direct investment, institutional quality, economic freedom and entrepreneurship in emerging markets. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 1921–1932.

Hammed, A. A. (2018). Corruption, political instability and development Nexus in Africa: A call for sequential policies reforms (Munich Personal RePEc archive, MPRA paper No. 8527). https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/85277/ Kakhkharov, J. (2019). Migrant remittances as a source of financing for entrepreneurship. International Migration, 57(5), 37–55. DOI:10.1111/imig.12531

Kotorri, M., Besnik A., Krasniqi B. A., & Dabic, M. (2020). Migration, Remittances, and Entrepreneurship: A Seemingly Unrelated Bivariate Probit Approach. Remittances Review, 5(1), 15–36

Kshetri, N., Rojas-Torres, D., & Acevedo, M. C. (2015). Diaspora networks, non-economic remittances and entrepreneurship development: Evidence from some economies in Latin America. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 20(01), 1550005.

Laniran, T. J., & Adeniyi, D. A. (2015). An evaluation of the determinants of remittances: Evidence from Nigeria. African Human Mobility Review, 1(2), 129–152.

LêKhang, T., & Thành, N. C. (2018, April). Economic growth, entrepreneurship, and institutions: evidence in emerging Countries. In The 5th IBSM international conference on business, management and accounting (pp. 19–21).

Lucas, R. E. B. & Stark, O. (1985). Motivation to Remit: Evidence from Botswana. Journal of Political Economy, 93(5), 901–918.

OECD. (2016). Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2016. OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2016-en

Olaniyi, C. O., Dada, J. T., Odihambo, N. M., & Xuan V. V. (2023). Modelling asymmetric structure in the finance-poverty nexus: Empirical Insights from An Emerging Market Quality and Quantity, 57(1), 453–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01363-3

Olaniyi, C. O., & Adedokun, A. (2022). Finance-institution-growth trilogy: Time-series insights from South Africa. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17(2).

Olubodun, I. E., Dada J. T., Omodara O. D., & Tabash M. I. (2025). Ease of Doing Business and Enterprise Creation in Africa: A Cross-Country Panel Analysis. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 34(1), 151–180.

McCormick, B., &. Wahba, J. (2001). Overseas Work Experience, Savings and Entrepreneurship Amongst Return Migrants to LDCs. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 48, 164–178.

Mohammed, U., & Karagöl, E.T. (2023). Remittances, institutional quality and investment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Business and Socio-economic Development, 3(4), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBSED-07-2022-0077

Mourougane, A., Égert, B., Baker, M., & Fülöp, G. (2020). The Policy Drivers of Self-Employment: New Evidence from Europe (CESifo Working Paper, No. 8780, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich, 1–16). https://hdl.handle.net/10419/229598

National Bureau of Statistics (2024). NBS says 84% of working-class Nigerians are self-employed - Nairametrics. https://nairametrics.com/2024/09/25/nbs-says-84-of-working-class-nigerians-are-self-employed/#:~:text=The National Bureau of Statistics,2024 report by the NBS.

North, D. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5, 97–112.

Nyame-Asiamah, F., Amoako, I. O., Amankwaah-Amoah, J., & Debrah, Y. (2020). Diaspora entrepreneurs’ push and pull institutional factors for investing in Africa: Insights from African returnees from the United Kingdom. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152, 119876. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119876

Nyström K. (2008). The Institutions of Economic Freedom and Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Panel Data. Public Choice, 136(3/4), 269–282. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40270760

OECD/ERIA (2018). SME Policy Index: ASEAN 2018: Boosting Competitiveness and Inclusive Growth. OECD Publishing, Paris/Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, Jakarta. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264305328-en

Petreski, M., & Mojsoska-Blazevski, N. (2015). Youth Self-Employment in Households Receiving Remittances in the Republic of Macedonia. Czech Journal of Economics and Finance, 65(6), 499–523. https://ideas.repec.org/a/fau/fauart/v65y2015i6p499-523.html

Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326.

Plaza, S., Navarrete, M., & Ratha, D. (2011). Migration and remittances household surveys in sub-Saharan Africa: Methodological aspects and main findings. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Premand, P., Brodmann, S., Almeida, R., Grun, R., & Baroun, M. (2016). Entrepreneurship Education and Entry into Self-Employment Among University Graduates. World Development, 77, 311–327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.08.028

Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: the primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 131–165. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000031425.72248.85

Salia, S., Hussain, J. G., Alhassan, Y., & Ibrahim, M. (2022). The Impact of Entrepreneurship Framework and Behaviour on Diaspora Remittance: An African Perspective. In The Palgrave Handbook of African Entrepreneurship (pp.145–169).

Salman, K. K. (2016). Have Migrant Remittances Influenced Self-Employment and Welfare among Recipient Households in Nigeria? (African Growth and Development (AGRODEP) Working Paper 0030, 1-30).

Shapiro, A. F., & Mandelman, F. S. (2016). Remittances, entrepreneurship, and employment dynamics over the business cycle. Journal of International Economics, 103, 184–199.

Statista. (2024). Countries with the highest unemployment rate 2023 | Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264656/countries-with-the-highest-unemployment-rate/

Statista. (2024). African countries with the highest share of global population living below the extreme poverty line in 2024. Africa: share of global poverty by country 2024 | Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1228553/extreme-poverty-as-share-of-global-population-in-africa-by-country/

Sohst, R. (2024). Leaving No One Behind: Inclusive Fintech for Remittances. Migration Policy Institute. Research: Leaving No One Behind: Inclusive Fintech. | migrationpolicy.org

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The New Economics of Labor Migration. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 173–178.

Taylor, J. E. (1999). The New Economics of Labour Migration and the Role of Remittances in the Migration Process. Internattional Migration. 37(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00066

Vaaler, P. M. (2013). Diaspora concentration and the venture investment impact of remittances. Journal of International Management, 19(1), 26–46.

Wynn, M. T. (2016). Chameleons at large: Entrepreneurs, Employees and Firms – the changing context of Employment Relationships. Journal of Management and Organization, 22(6), 826–842. .https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.40

Yavuz, R. I., & Bahadir, B. (2022). Remittances, Ethnic Diversity, and Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries. Small Business Economics, 58, 1931–1952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00490-9

Zheng, C., & Musteen, M. (2018) The Impact of Remittances on Opportunity-Based and Necessity-Based Entrepreneurial Activities. Academy Entrepreneurship Journal, 24, 1–13.