Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2025, vol. 16, no. 2(33), pp. 366–386 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2025.16.16

The Dark Side of The Moon: Unmasking Behavioral Risk Behind Fintech Adoption Among Digital Natives

Syarief Dienan Yahya (corresponding author)

Institut Teknologi dan Bisnis Kalla, Indonesia

dienanyahya@kallainstitute.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8160-9265

Andi Fauziah Yahya

Institut Teknologi dan Bisnis Kalla, Indonesia

afyahya@kallainstitute.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4013-9839

Yogi Hady Afrizal

Institut Teknologi dan Bisnis Kalla, Indonesia

yogi@kallainstitute.ac.id

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7413-9701

Abstract. The rapid expansion of financial technology (fintech) has reshaped financial behavior, especially among digital natives in Indonesia. This study examines the impact of financial inclusion and financial literacy on online loan decisions and impulsive buying behavior, with online loan decisions serving as a mediator. A survey was conducted with 334 respondents, focusing on digital natives who have used online loan services. Using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), the study found that financial inclusion positively influences online loan decisions, while financial literacy negatively impacts both online loan decisions and impulsive buying behavior. Notably, online loan decisions partially mediate the relationship between financial inclusion, financial literacy, and impulsive buying behavior. These findings highlight the complex role of fintech in promoting financial inclusion while also introducing behavioral risks. The study underscores the importance of financial literacy in mitigating impulsive financial behaviors among digital natives.

Keywords: financial inclusion, financial literacy, online loan decisions, impulsive buying behavior, digital natives, fintech

Received: 28/12/2024. Accepted: 4/5/2025

Copyright © 2025 Syarief Dienan Yahya, Andi Fauziah Yahya, Yogi Hady Afrizal. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Financial transformation has significantly reshaped the global economy in the modern era, introducing new ways in which individuals perceive, access, and manage their finances. This transformation, powered by innovations in information and communication technology, has resulted in profound changes in financial behavior, impacting savings, investment, debt management, and general decision-making processes. The digital revolution, in particular, has given rise to new business models (Stiglitz, 2017), with financial intermediation evolving through the introduction of fintech platforms (Goldstein et al., 2019). Traditional lending models, once dominated by conventional banks, have been disrupted by fintech companies that offer faster, more efficient, and more accessible consumer experiences (Allen et al., 2023). This shift in the financial landscape has been especially pronounced in Indonesia, where the fintech industry and the digital economy have witnessed rapid growth. The Financial Services Authority (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan) Indonesia noted that from 2016, when only six fintech companies were recorded, the number grew to 101 companies by 2024, with a particular focus on peer-to-peer lending (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan, 2024) The total outstanding financing in Indonesia’s fintech peer-to-peer (P2P) lending sector reached IDR 60.42 trillion (approximately 3.77 billion USD) in January 2024, reflecting an 18.4% increase from the previous year (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan, 2024).

The proliferation of financial technology (fintech) platforms has reshaped financial behavior, especially among younger, tech-savvy consumers, often referred to as digital natives. This generation has unprecedented access to digital loan platforms and financial services via mobile devices, enabling quick and convenient financial transactions (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018; Goldstein et al., 2019). While this accessibility enhances financial inclusion, several studies have raised concerns about its unintended consequences. In particular, the real-time and easily accessible nature of fintech services may heighten the susceptibility of digital natives to impulsive borrowing and poor financial planning, especially for those with limited self-regulation and financial literacy (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; Oksanen et al., 2018). Despite growing interest in fintech’s potential to bridge financial gaps, relatively little is known about the behavioral risks associated with its usage, particularly in emerging markets like Indonesia. These behavioral risks may include impulsive buying and over-indebtedness, leading to long-term financial distress.

Among digital natives in Indonesia, online loan users are predominantly between the ages of 19 and 34 years. This demographic is particularly vulnerable to impulsive financial behaviors due to their deep engagement in digital technologies and social media. Digital natives, who have grown up with the internet, are more likely to engage in quick, convenience-driven financial decisions, often without fully assessing the long-term consequences (Palfrey & Gasser, 2011). Their ability to access online information rapidly and their reliance on digital tools to solve problems have transformed how they approach financial decisions (Teo et al., 2016). Additionally, digital natives are prime targets for digital consumerism—they are highly exposed to online marketing and are significantly influenced by peer pressure and social norms in digital spaces (Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019; Savolainen et al., 2021). This generation tends to make purchasing decisions quickly, often without considering the financial consequences, leading to higher tendencies toward impulsive buying (Iyer et al., 2020).

The phenomenon of excessive consumption, which may cause long-term financial burdens, has been well-documented in the literature (Oksanen et al., 2018), with digital natives often labeled as the “generation in debt” (Houle, 2014). In some developing countries, young people are provided easy access to consumer loans, including payday loans, which are typically associated with high interest rates and short repayment periods. These loans are often available to individuals without stable income sources, further exacerbating the potential for financial instability (Autio et al., 2009; Bhutta et al., 2015).

Several studies have examined financial transformation through the lenses of financial inclusion and literacy, particularly in relation to consumer behaviors such as impulsive buying and hedonism. For instance, research conducted in Uganda explored the connection between financial inclusion and financial behaviors marked by hedonism (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al., 2021), while studies in Finland (Nyrhinen et al., 2024) and India (Badgaiyan & Verma, 2014) have examined online impulse buying among youth. In the United States, Houle (2014) focused on the decision-making processes of young adults regarding debt, and in Indonesia, studies have observed the rising trend of online loan decisions and their relationship with financial behavior (Rahmadyanto & Ekawaty, 2023; Yana & Setyawan, 2023). However, despite these contributions, there remains a significant gap in the literature regarding the behavioral risks of fintech adoption among digital natives, particularly in the context of emerging markets like Indonesia.

This study aims to address this gap by focusing on the psychological and behavioral consequences of fintech adoption, especially the “dark side”—unintended behaviors such as impulsive buying. It does so by investigating how financial inclusion and financial literacy influence online loan decisions and impulsive buying behavior among digital natives in Indonesia. Financial inclusion refers to the extent to which individuals can access and use formal financial services, which has been linked to increased participation in digital financial services (Chen et al., 2023; Daud & Ahmad, 2023). Financial literacy, on the other hand, reflects an individual’s ability to make informed financial decisions, which is crucial in mitigating the risks of impulsive borrowing and overspending, particularly in complex digital financial environments (Balasubramnian & Sargent, 2020; Kumar et al., 2023). Online loan decisions represent a concrete behavioral manifestation of fintech usage, closely tied to both financial inclusion (access) and financial literacy (knowledge) (Bollaert et al., 2021; Huda et al., 2024). Impulsive buying behavior is examined in this study as a critical outcome variable, reflecting emotional and psychological dimensions that are increasingly relevant in digital consumer environments (Huang et al., 2024; Nyrhinen et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2022).

While financial inclusion and literacy have been widely studied in terms of access and capability, their influence on behavioral outcomes—such as impulsive spending and unplanned borrowing—remains underexplored, particularly among digital natives. By incorporating online loan decisions as a mediating variable, this study bridges structural financial factors with actual consumer behavior. This integrated approach offers a deeper understanding of how access and knowledge interact to shape financial risk-taking, highlighting the dual nature of fintech as both an enabler of inclusion and a potential driver of vulnerability.

While this study is grounded in the Indonesian context, its findings offer broader implications for understanding financial behavior among digital natives in emerging markets. Many developing countries are experiencing similar challenges, including low financial literacy levels, high exposure to digital credit, and weak regulatory safeguards, all of which heighten the risks of impulsive consumption and debt accumulation (Lyons et al., 2022; Nguyen, 2022; Sanga & Aziakpono, 2024). Moreover, digital natives across regions such as Southeast Asia, South Asia, and parts of Africa share common traits: early adoption of mobile technology, high responsiveness to digital marketing, and vulnerability to impulsive consumption patterns (Badgaiyan & Verma, 2014; Houle, 2014; Nyrhinen et al., 2024; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al., 2021). By exploring the psychological and behavioral dimensions of fintech usage, this study offers insights that extend beyond Indonesia, contributing to a more generalizable understanding of digital financial vulnerability in transitional economies.

This study highlights that while fintech can empower individuals by improving financial inclusion, it also introduces significant behavioral risks. The findings stress the importance of addressing these risks through integrated financial literacy programs aimed at fostering responsible borrowing and financial decision-making.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1 Financial Inclusion

Financial inclusion refers to the accessibility of financial services such as savings, credit, insurance, and payments to underserved and unbanked populations. It plays a pivotal role in empowering individuals and improving their financial well-being, particularly in emerging economies, where traditional banking services are often inaccessible. In the context of fintech platforms, financial inclusion has become increasingly significant. These platforms bridge the gap between underserved communities and essential financial services by offering easier access to online loans (Lusardi, 2019). Access to these services provides individuals with opportunities to participate fully in the financial system, facilitating better financial management, including saving, borrowing, and investment (Carpena et al., 2011).

As fintech solutions grow, particularly among digital natives, financial inclusion has enhanced the accessibility of credit and loan services. However, this access is often accompanied by risks, particularly among financially illiterate individuals who may not fully understand the implications of taking out loans. The growing availability of online loans has been shown to increase the propensity for impulsive borrowing, especially in populations with low financial literacy (Adil et al., 2022). Therefore:

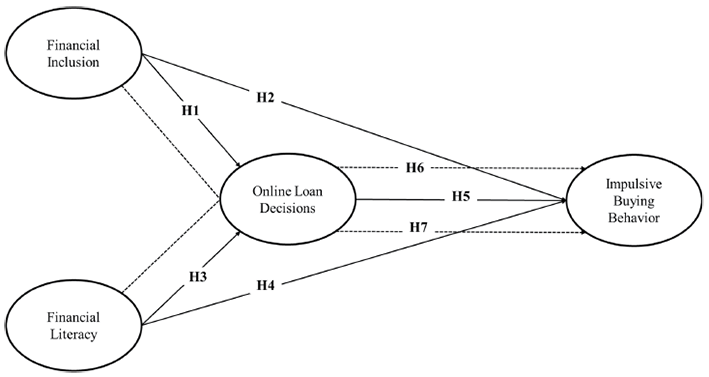

H1: Financial inclusion positively influences online loan decisions among digital natives.

H2: Financial inclusion positively influences impulsive buying behavior among digital natives.

2.2 Financial Literacy

Financial literacy encompasses the knowledge and understanding needed to make informed decisions about personal finances, including the management of credit, debt, savings, and investments (Carpena et al., 2011). It is a crucial determinant of responsible financial decision-making, which has significant implications for online loan decisions. Higher levels of financial literacy are linked to more informed, rational financial behaviors such as prudent borrowing, investing, and saving. Financially literate individuals are better able to assess the risks of digital loans and avoid making impulsive borrowing decisions (Lusardi, 2019).

However, low financial literacy is particularly concerning among digital natives, who, despite their high technological proficiency, may lack the necessary skills to make informed financial choices in the fintech environment. This gap in knowledge leads to impulsive borrowing behavior, as individuals may engage with online loan platforms without fully understanding the long-term financial consequences (Garg & Singh, 2018). Thus:

H3: Financial literacy negatively influences online loan decisions among digital natives.

H4: Financial literacy negatively influences impulsive buying behavior among digital natives.

2.3 Fintech Online Loans and Impulsive Buying Behavior

Online loans, as offered by fintech platforms, represent a shift from traditional credit models, providing consumers with fast, accessible, and convenient borrowing options. These platforms cater to digital natives, who value the ease of use and speed of obtaining credit through mobile devices and online platforms (Oksanen et al., 2018). Fintech platforms typically offer higher interest rates and shorter repayment terms compared to traditional bank loans, which, while providing convenience, also present risks. Individuals may be more likely to take out loans impulsively, particularly when faced with emotional triggers or the allure of instant gratification (Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019).

The rapid approval processes of online loans are often coupled with minimal checks on an individual’s financial behavior, making it easy for borrowers to access credit without fully evaluating the potential risks. For digital natives, this ease of access and convenience can drive impulsive buying behaviors, further exacerbating financial instability, especially when combined with low financial literacy (Adil et al., 2022). Thus, understanding the role of Fintech in facilitating online loan decisions is essential for identifying risks and promoting responsible borrowing. Impulsive buying behavior refers to unplanned, spontaneous purchases often driven by emotional responses, rather than rational decision-making (Iyer et al., 2020). This behavior is particularly prevalent among digital natives, who are heavily exposed to digital marketing, personalized advertisements, and social media influences. The ease of access to credit via fintech platforms and online loans makes these consumers more susceptible to impulsive spending decisions. Research suggests that the combination of instant credit and emotional triggers significantly influences impulsive buying behavior, especially in a digital context (Savolainen et al., 2021).

The rapid approval processes offered by fintech platforms enable digital natives to access loans quickly, facilitating immediate purchases. However, this ease of borrowing can lead to financial instability if not managed responsibly. Financial literacy plays a critical role in mitigating these risks by helping individuals evaluate the long-term consequences of borrowing (Katauke et al., 2023; Lührmann et al., 2015; Potrich & Vieira, 2018). Based on these results, we develop the following hypotheses:

H5: Online loan decisions positively influence impulsive buying behavior among digital natives.

H6: Online loan decisions mediate the impact of financial inclusion on impulsive buying behavior among digital natives.

H7: Online loan decisions mediate the impact of financial literacy on impulsive buying behavior among digital natives.

A conceptual framework has been developed to illustrate the relationships and influence between variables based on theoretical and empirical reviews. The conceptual model for this study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Research Conceptual Framework

3. Research Methodology

This study adopts a quantitative research approach to examine the relationships between financial inclusion, financial literacy, online loan decisions, and impulsive buying behavior among digital natives in Indonesia. Data collection is conducted through a survey method using a structured questionnaire measured on a 5-point Likert scale with a total of 334 respondents who have used online loan services within the past year. These respondents are classified as digital natives, born between 1980 and 2005, representing the age group legally eligible to access online lending platforms under Indonesian law.

The measurement of variables in this study is based on established scales, adapted from previous research and refined through questionnaire testing. The Financial Inclusion (FI) variable is measured using three dimensions: Accessibility (FI.1), Availability (FI.2), and Usage (FI.3), based on the Index of Financial Inclusion (IFI) (Sarma & Pais, 2011), which has been widely used in financial inclusion research and adapted for Indonesian contexts. The Financial Literacy (FL) variable is treated as a multidimensional construct, incorporating three dimensions: Financial Knowledge (FL.1), Financial Behavior (FL.2), and Financial Attitude (FL.3), as suggested by Bajaj and Kaur (2022) and Méndez-Prado et al. (2023). These dimensions are correlated and together form a unified concept of financial literacy, which has been shown to influence financial decision-making (Lusardi, 2019).

The Online Loan Decision (OLD) variable is measured by three key indicators: Attitude (OLD.1), Subjective Norms (OLD.2), and Perceived Behavioral Control (OLD.3), adapted from the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991). This theory has been widely applied to understand consumer decision-making in financial contexts, including online lending behavior. The Impulsive Buying Behavior (IB) variable is adapted from Badgaiyan et al. (2016), focusing on measuring impulsive purchasing tendencies using eight items across two dimensions: Cognitive Factor (e.g., unplanned purchases, lack of control) and Affective Factor (e.g., excitement, emotional pleasure). These items were carefully chosen based on the relevance of these dimensions to the digital native population.

Each measurement instrument was carefully selected and validated. For example, the Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion scales have been extensively used and validated in similar studies, while the Impulsive Buying Behavior scale was adapted and validated through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to ensure its reliability and construct validity. Additionally, the scales were pre-tested through a pilot study to refine the questionnaire and confirm its relevance for the study’s context, ensuring that the instruments effectively capture the intended constructs in the digital native’s context.

The study employs descriptive statistics and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) for data analysis. SEM is conducted using SmartPLS version 3, which allows for the evaluation of both the inner model (structural relationships) and the outer model (measurement reliability and validity). The outer model testing includes assessments for convergent validity, discriminant validity, and construct reliability, while the inner model evaluates path coefficients, coefficient of determination (R²), effect size (f²), and predictive relevance (Q²) (Hair et al., 2019). Additionally, a moderation analysis was performed to identify the influence of moderating variables.

4. Result

4.1 The Description of the Respondents

The gender distribution shows that 154 respondents (45.5%) were male, while 181 respondents (54.2%) were female. In terms of age, the majority of respondents fell within the age range of 19 to 31 years (54.2%), highlighting the dominance of the digital native generation, who are considered highly adept at using technology and engaging with digital financial services.

Regarding occupational background, respondents were primarily employed in the private sector, with 164 individuals (49.1%) reporting this as their main source of employment. This finding underscores the significance of private-sector workers as key users of online loan platforms, likely driven by their financial needs and familiarity with digital financial tools. Other occupations, though not as dominant, also contributed to the diversity of the sample, ensuring a balanced representation across various professional backgrounds.

These demographic insights provide a foundational understanding of the respondents’ profiles, reflecting their relevance to the study objectives. A detailed breakdown of the respondents’ characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic Data of the Research Sample (n=334)

|

Demographic Characteristics |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

154 |

45.5% |

|

Female |

181 |

54.2% |

|

Age Group |

||

|

19–24 years |

86 |

25.7% |

|

25–30 years |

141 |

42.2% |

|

31–35 years |

107 |

32.0% |

|

Marital Status |

||

|

Single |

136 |

40.7% |

|

Married |

93 |

27.8% |

|

Divorced |

57 |

17.1% |

|

Widowed |

48 |

14.4% |

|

Employment Status |

||

|

Employed |

237 |

71.0% |

|

Not employed |

97 |

29.0% |

|

Monthly Income |

||

|

No income |

98 |

29.3% |

|

Less than $187.50 |

57 |

17.1% |

|

$187.50 – $374.99 |

70 |

21.0% |

|

$375 – $624.99 |

49 |

14.7% |

|

$625 – $937.49 |

15 |

4.5% |

|

$937.50 – $1562.49 |

18 |

5.4% |

|

More than $1562.50 |

27 |

8.1% |

|

Regional Classification |

||

|

Sumatera Island |

48 |

14.4% |

|

Java Island |

76 |

22.8% |

|

Kalimantan Island |

55 |

16.5% |

|

Sulawesi Island |

122 |

36.5% |

|

Papua Island |

17 |

5.1% |

|

Other Islands |

16 |

4.8% |

|

Borrowing Experience |

||

|

First-time Borrowers |

194 |

58.1% |

|

Repeat Borrowers |

140 |

41.9% |

In terms of monthly income, a significant proportion of respondents, 29.3% (98 individuals), reported having no income. This figure indicates a substantial segment of the population that may lack stable sources of earnings, making them more likely to seek alternative financial solutions such as online loans. Respondents earning less than IDR 3,000,000 (approximately $187.50) per month account for 17.1% (57 respondents), while those in the IDR 3,000,000–5,999,999 range (approximately $187.50 – $374.99) represent 21.0% (70 respondents). Respondents earning between IDR 6,000,000 and IDR 9,999,999 (approximately $375– $624.99) account for 14.7% (49 respondents), and those earning between IDR 10,000,000 and IDR 14,999,999 (approximately $625–$937.49) account for 4.5% (15 respondents). A smaller group of individuals with higher monthly incomes—IDR 15,000,000–24,999,999 (approximately $937.50–$1562.49) and more than IDR 25,000,000 (approximately $1562.50)—comprises 13.5% (45 respondents). This income distribution reflects significant economic diversity among respondents, which may influence their financial behavior and reliance on credit facilities.

The regional classification of respondents illustrates a broad geographical distribution across Indonesia’s major islands. Sulawesi Island accounts for the largest proportion of participants, with 36.5% (122 respondents), indicating considerable engagement with online loan platforms in this region. This is followed by Java Island, which represents 22.8% (76 respondents), a figure likely driven by the island’s dense population and higher access to financial and technological infrastructure. Kalimantan Island contributed 16.5% (55 respondents), while Sumatera Island represented 14.4% (48 respondents). Smaller proportions were recorded for Papua Island at 5.1% (17 respondents) and Other Islands at 4.8% (16 respondents). These figures highlight regional variations in the adoption of digital financial services, potentially influenced by differing levels of economic development, internet accessibility, and financial inclusion across the country.

When examining marital status, the largest group of respondents—40.7% (136 individuals)—are single. This group likely includes younger individuals who are in the early stages of financial independence and may use online loans to meet lifestyle-related needs. Married respondents account for 27.8% (93 individuals), reflecting their likely engagement with credit for family-related financial obligations. Divorced respondents represent 17.1% (57 individuals), while widowed individuals make up 14.4% (48 respondents). These findings suggest that marital status may play a role in financial behaviors, as individuals in different stages of life face distinct financial pressures and borrowing motivations.

The borrowing experience of respondents reveals two key categories: first-time borrowers and repeat borrowers. A majority of respondents, 58.1% (194 individuals), reported borrowing through online platforms for the first time. This figure highlights the growing popularity and adoption of online loan services among new users, particularly in a digitally connected generation. In contrast, 41.9% (140 individuals) are classified as repeat borrowers, indicating continued reliance on digital lending platforms. This group may represent individuals who find online loans to be a convenient and accessible source of credit for recurring financial needs.

Overall, this data reflects that the decision to use online loan services is largely influenced by the financial needs of young, productive individuals, particularly those with significant economic responsibilities or limited income. Additionally, online lending platforms have successfully attracted new users across different regions and economic backgrounds, demonstrating their broad reach and accessibility in addressing diverse financial needs.

4.2 Outer Model Testing (Validity and Reliability Test)

The collected data were evaluated to ensure the validity and reliability of the measurement model. The assessment involved testing Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s Alpha to determine the internal consistency of the data. According to Hair et al. (2014), the CR value must exceed 0.7, while Cronbach’s Alpha should also surpass the threshold of 0.7 to indicate acceptable internal consistency. As shown in Table 2, all latent variables meet these criteria, demonstrating strong internal reliability across the constructs.

To further validate the research instrument, a two-step approach was employed, comprising convergent validity and discriminant validity tests. Convergent validity was assessed through two key indicators: the outer loadings of each observed variable and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values. For adequate convergent validity, the outer loading values for all observed indicators must exceed 0.7, and the AVE values for each latent construct must be greater than 0.5. The results presented in Table 2 confirm that all observed variables meet these thresholds, supporting strong convergent validity of the constructs.

Discriminant validity was evaluated using two key methods: cross-loading analysis and the Fornell-Larcker criterion. In cross-loading analysis, each indicator’s loading on its respective construct must be higher than its loading on any other construct, ensuring that the indicators measure their intended constructs uniquely. The Fornell-Larcker criterion further verifies discriminant validity by confirming that the square root of the AVE for each latent variable is greater than its correlations with other constructs. The results demonstrate that the measurement model successfully meets the discriminant validity requirements, indicating that the constructs are distinct and not overly correlated with one another.

The final step in ensuring reliability involved calculating Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s Alpha values for each construct. Both metrics are used to test the internal consistency of the instrument, with acceptable thresholds set at > 0.7.

Table 2

Validity and Reliability Test Result

|

Variables |

Items |

Loadings |

AVE |

Composite Reliability |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Financial Inclusion (FI) |

FI1 |

0.78 |

0.583 |

0.88 |

0.82 |

|

FI2 |

0.81 |

||||

|

FI3 |

0.72 |

||||

|

FI4 |

0.84 |

||||

|

FI5 |

0.76 |

||||

|

FI6 |

0.69 |

||||

|

Financial Literacy (FL) |

FL1 |

0.82 |

0.679 |

0.92 |

0.85 |

|

FL2 |

0.79 |

||||

|

FL3 |

0.87 |

||||

|

FL4 |

0.74 |

||||

|

FL5 |

0.88 |

||||

|

FL6 |

0.83 |

||||

|

FL7 |

0.77 |

||||

|

FL8 |

0.71 |

||||

|

FL9 |

0.85 |

||||

|

Online Loan Decision |

OL1 |

0.80 |

0.759 |

0.89 |

0.81 |

|

OL2 |

0.73 |

||||

|

OL3 |

0.76 |

||||

|

OL4 |

0.81 |

||||

|

OL5 |

0.84 |

||||

|

OL6 |

0.78 |

||||

|

Impulsive Buying |

IB1 |

0.79 |

0.664 |

0.92 |

0.83 |

|

IB2 |

0.82 |

||||

|

IB3 |

0.70 |

||||

|

IB4 |

0.86 |

||||

|

IB5 |

0.74 |

||||

|

IB6 |

0.88 |

||||

|

IB7 |

0.83 |

||||

|

IB8 |

0.76 |

Note. Results from Smart PLS 3.

The validity and reliability testing of the measurement model were conducted to ensure the constructs used in this study exhibit sufficient accuracy and consistency. The analysis involved four constructs: Financial Inclusion, Financial Literacy, Online Loan Decisions, and Impulsive Buying Behavior. Convergent validity was evaluated using the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Outer Loadings, while reliability was assessed through Composite Reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha.

For the Financial Inclusion construct, the results indicate that the outer loadings of the indicators range from 0.69 to 0.84. Although FI6 reported a loading value of 0.69, which is marginally below the ideal threshold of 0.7, it remains acceptable due to its contribution to the overall reliability of the construct. Through model refinement, the AVE value improved from 0.483 to 0.583, which now meets the minimum criterion of 0.5 for convergent validity. Furthermore, the construct demonstrated strong reliability, with a Composite Reliability of 0.88 and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.82. These results confirm that the indicators adequately explain the variance within the construct and exhibit good internal consistency.

For the Financial Literacy construct, all indicators demonstrated strong loadings, ranging from 0.71 to 0.88, thereby fulfilling the requirements for convergent validity. The AVE value was 0.679, indicating that a significant portion of the variance is explained by the construct. The reliability measures were equally robust, with a Composite Reliability of 0.92 and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.85, reflecting excellent internal consistency. These findings affirm that the measurement items are reliable and valid for capturing the concept of financial literacy.

The Online Loan Decisions construct exhibited outer loadings ranging between 0.73 and 0.84, confirming their substantial contribution to the construct. The AVE value of 0.759 indicates a high level of convergent validity, as more than 75% of the variance is explained by the construct. Reliability measures were also satisfactory, with a Composite Reliability of 0.89 and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.81. These results demonstrate that the indicators are consistent and reliable in measuring individuals’ online loan decisions.

The Impulsive Buying Behavior construct similarly exhibited satisfactory results, with outer loadings ranging from 0.70 to 0.88. The AVE value of 0.664 confirms strong convergent validity, as it exceeds the 0.5 threshold. Furthermore, the reliability measures, comprising a Composite Reliability of 0.92 and a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.83, indicate excellent internal consistency. These results suggest that the indicators reliably capture the impulsive buying behavior construct.

In conclusion, the results of the validity and reliability tests confirm that all constructs meet the required statistical criteria. The AVE values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.5, ensuring adequate convergent validity. Similarly, the high values of Composite Reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha (all above 0.7) demonstrate strong internal consistency for each construct. The refinement process significantly improved the Financial Inclusion construct, aligning it with acceptable standards of validity and reliability. Therefore, the measurement model is considered robust, valid, and reliable, making it suitable for further structural model analysis to evaluate the relationships among constructs in the study.

4.3 Inner Model Testing (The Structural Model)

Following the successful evaluation of the measurement model, which established the validity and reliability of the constructs through convergent and discriminant validity, the next step is to evaluate the structural model or conduct inner model testing. This stage is essential to assess the relationships between latent variables and determine the explanatory and predictive power of the model.

In addition, the path coefficients are evaluated to analyze the strength and direction of the hypothesized relationships. Their statistical significance is determined through the bootstrapping procedure, where the results are assessed using the t-statistic (t > 1.96 for α = 0.05) and p-value (p < 0.05) to confirm the robustness of the relationships (Hair et al., 2019).

Table 3

Results of the Structural Model

|

Hypothesis |

Relationship |

Path |

t-Statistic |

p-Value |

Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H1 |

FI > OLD |

0.193 |

3.612 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

H2 |

FI > IB |

0.071 |

2.588 |

0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H3 |

FL > OLD |

-0.315 |

3.842 |

0.000 |

Accepted |

|

H4 |

FL > IB |

-0.287 |

3.512 |

0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H5 |

OLD > IB |

0.108 |

3.753 |

0.001 |

Accepted |

|

H6 |

FI > OLD > IB |

0.122 |

2.981 |

0.003 |

Accepted |

|

H7 |

FL > OLD > IB |

-0.162 |

2.745 |

0.006 |

Accepted |

This study offers valuable insights into the role of financial inclusion, financial literacy, and online loan decisions in shaping impulsive buying behavior among digital natives. The findings reveal the complex relationships between these factors, contributing to the growing body of literature on the unintended consequences of fintech adoption.

The relationship between financial inclusion and online loan decisions (H1) is found to be positive and significant, with a path coefficient of 0.193 (t-statistic = 3.612, p-value = 0.000). This suggests that increased access to financial services, particularly through fintech platforms, significantly boosts digital natives engagement in online lending. The findings are consistent with studies by Demirguc-Kunt et al. (2018), which argue that financial inclusion leads to greater participation in formal financial services. However, this access alone, without proper financial education, can raise concerns about irresponsible borrowing behavior (Ozili, 2020).

While financial inclusion positively influences online loan decisions, its direct effect on impulsive buying behavior (H2) is found to be weak yet significant, with a path coefficient of 0.071 (t-statistic = 2.588, p-value = 0.001). This result suggests that financial inclusion may indeed contribute to impulsive consumption patterns, but its effect is not as strong as other factors like financial literacy. This supports the findings of Xiao and Porto (2017), who suggested that access to credit can influence consumption behaviors, albeit the impact can be moderated by other factors such as self-control.

The relationship between financial literacy and online loan decisions (H3) is negative and significant, with a path coefficient of -0.315 (t-statistic = 3.842, p-value = 0.000). This finding indicates that individuals with higher financial literacy are less likely to make impulsive online loan decisions, aligning with Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) research that emphasizes the importance of financial education in preventing poor borrowing decisions. Financially literate individuals tend to be more cautious about borrowing, thus making more informed and prudent loan decisions.

Similarly, financial literacy is found to negatively influence impulsive buying behavior (H4), with a path coefficient of -0.287 (t-statistic = 3.512, p-value = 0.001). This result is consistent with Fernandes et al. (2014), suggesting that higher levels of financial literacy help individuals make better spending decisions and resist impulsive consumption. The findings highlight that financial literacy serves as a protective factor against impulsive buying, aligning with research that associates financial knowledge with sound financial behavior (Atkinson & Messy, 2012).

The relationship between online loan decisions and impulsive buying behavior (H5) is positive but not statistically significant (path coefficient = 0.108, p-value = 0.081). This finding suggests that while online loan decisions may influence impulsive behavior, the effect is insignificant in this study. This could be attributed to the self-control mechanisms and sophistication of digital natives, who, despite their engagement with fintech platforms, may not always translate access to credit into impulsive consumption. This result differs from earlier studies that found a stronger link between credit access and impulsivity (Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019). However, it is important to recognize that psychological and social factors may also contribute to impulsive behaviors, and these factors need further exploration.

The study confirms that online loan decisions mediate the relationship between financial inclusion and impulsive buying behavior (H6), with a path coefficient of 0.122 (p-value = 0.003). This suggests that while financial inclusion increases access to credit, online loans indirectly encourage impulsive consumption behavior, particularly when individuals lack financial literacy. Similarly, online loan decisions also mediate the relationship between financial literacy and impulsive buying behavior (H7), with a path coefficient of -0.162 (p-value = 0.006). This indicates that financial literacy indirectly helps curb impulsive behaviors by encouraging individuals to make better loan decisions.

5. Discussion

The study’s findings emphasize the dual role of financial literacy and financial inclusion in influencing online loan decisions and impulsive buying behavior among digital natives. While financial inclusion increases access to financial services, it does not directly lead to impulsive consumption. Instead, it exerts an indirect influence through online loan decisions, which act as a mediator in this relationship. On the other hand, financial literacy serves as a protective factor by reducing both impulsive borrowing and impulsive spending behaviors. These findings highlight the need for integrated approaches that not only expand financial inclusion but also enhance financial literacy to mitigate the behavioral risks of fintech adoption.

The positive and significant relationship between financial inclusion and online loan decisions (H1) supports previous research by Demirguc-Kunt et al. (2018), who emphasized that access to formal financial services enhances engagement with digital financial platforms. As Fintech platforms provide easy and quick access to credit, the study demonstrates that greater access to such services directly encourages digital natives to make online loan decisions. However, it is crucial to recognize that while financial inclusion facilitates access to financial products, it does not guarantee that individuals make informed financial decisions. This highlights the need for complementary financial literacy programs to help users make responsible borrowing choices.

Interestingly, while financial inclusion positively influences impulsive buying behavior (H2), the effect is weak and moderate. This finding contrasts with previous studies by Xiao and Porto (2017), which suggested a stronger link between access to credit and impulsive consumption. The weak effect observed in this study could be attributed to moderating factors such as individual differences in self-control and spending behavior, as well as socioeconomic factors that might influence impulsivity. Digital natives may also demonstrate a higher degree of financial awareness, which can act as a buffer against impulsive spending, even when credit is more easily accessible.

The negative relationship between financial literacy and online loan decisions (H3) is a key finding of this study, and it aligns with research by Lusardi and Mitchell (2014), which argues that higher levels of financial literacy are associated with more prudent borrowing behavior. Financially literate individuals tend to understand the risks involved in borrowing, especially from online platforms, where interest rates tend to be higher. This result suggests that financial literacy serves as a safeguard against impulsive loan-taking decisions, as individuals with greater knowledge of financial products are more likely to evaluate loan options carefully and avoid over indebtedness.

Similarly, financial literacy negatively influences impulsive buying behavior (H4), which supports Fernandes et al. (2014), who found that financially literate individuals are better at managing their finances and less likely to make spontaneous purchases. This finding highlights the importance of financial education in promoting responsible spending habits, particularly in environments where digital financial products such as online loans are readily available. The study underscores that financial literacy not only helps individuals manage debt but also curbs impulsive financial behaviors, thereby contributing to long-term financial well-being.

While online loan decisions are hypothesized to directly influence impulsive buying behavior (H5), the path coefficient for this relationship is not statistically significant. This finding suggests that while access to online loans may make it easier for individuals to engage in impulsive buying, other factors such as self-control, peer influences, and psychological triggers may play a more significant role in driving impulsive consumption. This supports the notion that impulsive buying behavior is not solely determined by credit access but is also influenced by psychological and social factors (Dhanesh & Duthler, 2019).

The results also show that online loan decisions partially mediate the relationship between financial inclusion and impulsive buying behavior (H6) as well as between financial literacy and impulsive buying behavior (H7). These findings suggest that financial inclusion increases access to credit through online loans, which in turn influences impulsive buying behavior. Similarly, financial literacy helps mitigate impulsive behaviors, but its effect is still indirectly influenced by online loan decisions. This aligns with Xiao and O’Neill (2016), who proposed that financial decisions, including borrowing, act as intermediaries between access to financial services and consumer behavior. Furthermore, Brüggen et al. (2017) emphasized that financial literacy and spending control are crucial for reducing impulsive financial behaviors.

6. Conclusions and Limitations of Study

This study provides valuable insights into the complex relationships between financial inclusion, financial literacy, online loan decisions, and impulsive buying behavior among digital natives in Indonesia. The findings reveal that financial inclusion facilitates greater access to online loans (Gallego-Losada et al., 2023; Tay et al., 2022), while financial literacy plays a significant role in mitigating impulsive behaviors such as unplanned spending and borrowing (Bhat et al., 2025). Specifically, while financial inclusion encourages engagement with fintech platforms, it does not directly foster impulsive buying behavior but rather influences it indirectly through online loan decisions. Additionally, financial literacy reduces impulsive buying behavior both directly and through its impact on online loan decisions. The study emphasizes the importance of integrating financial literacy programs alongside financial inclusion efforts to promote responsible borrowing and reduce impulsive financial behavior (Katauke et al., 2023), particularly in the context of the growing adoption of digital financial services.

However, this study also has some limitations that should be addressed in future research. Firstly, the data is cross-sectional, which limits the ability to infer causal relationships over time. Longitudinal studies could provide a deeper understanding of how financial inclusion and financial literacy evolve and influence financial behaviors in the long term (Carpena & Zia, 2020). Secondly, the study focuses on digital natives in Indonesia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other countries or age groups. Future research could explore whether these findings hold in different cultural and economic contexts (Henrich et al., 2010). Additionally, the study relies on self-reported data, which may be susceptible to biases such as social desirability and recall bias, issues frequently cited in survey research (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002; Podsakoff et al., 2003). Future studies could consider alternative data collection methods, such as behavioral tracking or experimental designs, to complement the findings. Finally, while this study focuses on the direct and indirect effects of financial inclusion and financial literacy, other variables such as psychological traits, peer influence, and social media exposure may also play crucial roles in shaping financial behavior and should be explored in future studies (Bursztyn et al., 2014; Duckworth & Seligman, 2005).

In conclusion, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on fintech adoption and its impact on consumer behavior (Gomber et al., 2017). By emphasizing the role of financial literacy in curbing impulsive consumption and highlighting the indirect effects of financial inclusion, the study offers important implications for policymakers and fintech platforms. Ensuring that digital natives have access not only to financial products but also to financial education is critical for promoting sustainable financial behaviors in the digital age.

References

Adil, M., Singh, Y., & Ansari, M. S. (2022). How financial literacy moderates the association between behavioral biases and investment decisions. Asian Journal of Accounting Research, 7(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJAR-09-2020-0086/FULL/PDF

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Allen, L., Shan, Y., & Shen, Y. (2023). Do FinTech mortgage lenders fill the credit gap? Evidence from natural disasters. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 58(8), 3342–3383. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002210902200120X

Atkinson, A., & Messy, F.-A. (2012). Measuring financial literacy. Results of the OECD / International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study. (OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance, and Private Pensions, Vol. 15). https://doi.org/10.1787/5k9csfs90fr4-en

Autio, M., Wilska, T. A., Kaartinen, R., & Lähteenmaa, J. (2009). The use of small instant loans among young adults – A gateway to consumer insolvency? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(4), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1470-6431.2009.00789.X

Badgaiyan, A. J., & Verma, A. (2014). Intrinsic factors affecting impulsive buying behavior—Evidence from India. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(4), 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRETCONSER.2014.04.003

Badgaiyan, A. J., Verma, A., & Dixit, S. (2016). Impulsive buying tendency: Measuring important relationships with a new perspective and an indigenous scale. IIMB Management Review, 28(4), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IIMB.2016.08.009

Bajaj, I., & Kaur, M. (2022). Validating a multi-dimensional model of financial literacy using confirmatory factor analysis. Managerial Finance, 48(9–10), 1488–1512. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-06-2021-0285

Balasubramnian, B., & Sargent, C. S. (2020). Impact of inflated perceptions of financial literacy on financial decision making. Journal of Economic Psychology, 80, 102306. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOEP.2020.102306

Bhat, S. A., Lone, U. M., SivaKumar, A., & Krishna, U. M. G. (2025). Digital financial literacy and financial well-being – Evidence from India. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 43(3), 522–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-05-2024-0320

Bhutta, N., Skiba, P. M., Tobacman, J., Bhutta, N., Skiba, P. M., & Tobacman, J. (2015). Payday loan choices and consequences. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 47(2–3), 223–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/JMCB.12175

Bollaert, H., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Schwienbacher, A. (2021). Fintech and access to finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 68, 101941. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCORPFIN.2021.101941

Brüggen, E. C., Hogreve, J., Holmlund, M., Kabadayi, S., & Löfgren, M. (2017). Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 79, 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2017.03.013

Bursztyn, L., Ederer, F., Ferman, B., & Yuchtman, N. (2014). Understanding mechanisms underlying peer effects: Evidence from a field experiment on financial decisions. Econometrica, 82(4), 1273–1301. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA11991

Carpena, F., Cole, S., Shapiro, J., & Zia, B. (2011). Unpacking the causal chain of financial literacy (Policy Research Working Paper WPS 5798 (Word Bank). https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5798

Carpena, F., & Zia, B. (2020). The causal mechanism of financial education: Evidence from mediation analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 177, 143–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEBO.2020.05.001

Chen, W., Wu, W., & Zhang, T. (2023). Fintech development, firm digitalization, and bank loan pricing. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 39, 100838. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBEF.2023.100838

Daud, S. N. M., & Ahmad, A. H. (2023). Financial inclusion, economic growth, and the role of digital technology. Finance Research Letters, 53, 103602. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FRL.2022.103602

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1259-0

Dhanesh, G. S., & Duthler, G. (2019). Relationship management through social media influencers: Effects of followers’ awareness of paid endorsement. Public Relations Review, 45(3), 101765. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PUBREV.2019.03.002

Donaldson, S. I., & Grant-Vallone, E. J. (2002). Understanding self-report bias in organizational behavior research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019637632584/METRICS

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychological Science, 16(12), 939–944. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-9280.2005.01641.X

Fernandes, D., Lynch, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Management Science, 60(8), 1861–1883. https://doi.org/10.1287/MNSC.2013.1849

Gallego-Losada, M. J., Montero-Navarro, A., García-Abajo, E., & Gallego-Losada, R. (2023). Digital financial inclusion: Visualizing the academic literature. Research in International Business and Finance, 64, 101862. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RIBAF.2022.101862

Garg, N., & Singh, S. (2018). Financial literacy among youth. International Journal of Social Economics, 45(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-11-2016-0303/FULL/XML

Goldstein, I., Jiang, W., & Karolyi, G. A. (2019). To FinTech and beyond. The Review of Financial Studies, 32(5), 1647–1661. https://doi.org/10.1093/RFS/HHZ025

Gomber, P., Koch, J. A., & Siering, M. (2017). Digital finance and FinTech: Current research and future research directions. Journal of Business Economics, 87(5), 537–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11573-017-0852-X/METRICS

Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. C. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. Cengage Learning.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128/FULL/XML

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Houle, J. N. (2014). A generation indebted: Young adult debt across three cohorts. Social Problems, 61(3), 448–465. https://doi.org/10.1525/SP.2014.12110

Huang, S. C., Silalahi, A. D. K., Eunike, I. J., & Riantama, D. (2024). Understanding impulse buying in e-commerce: The big five traits perspective and moderating effect of time pressure and emotions. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 15, 100157. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TELER.2024.100157

Huda, M., Ajizah, N., Nuzil, N. R., & Fachruddin, W. (2024). The influence of financial inclusion and financial technology on the intention to use online loans: Financial behavior as an intervening variable. Journal of Ecohumanism, 3(8), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.62754/JOE.V3I8.4722

Iyer, G. R., Blut, M., Xiao, S. H., & Grewal, D. (2020). Impulse buying: A meta-analytic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 384–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11747-019-00670-W/TABLES/9

Katauke, T., Fukuda, S., Khan, M. S. R., & Kadoya, Y. (2023). Financial literacy and impulsivity: Evidence from Japan. Sustainability, 15(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/SU15097267

Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. (2024). Statistik P2P Lending Periode Januari 2024. In Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. https://ojk.go.id/id/kanal/iknb/data-dan-statistik/fintech/Pages/Statistik-P2P-Lending-Periode-Januari-2024.aspx

Kumar, P., Pillai, R., Kumar, N., & Tabash, M. I. (2023). The interplay of skills, digital financial literacy, capability, and autonomy in financial decision making and well-being. Borsa Istanbul Review, 23(1), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIR.2022.09.012

Lührmann, M., Serra-Garcia, M., & Winter, J. (2015). Teaching teenagers in finance: Does it work? Journal of Banking and Finance, 54, 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBANKFIN.2014.11.009

Lusardi, A. (2019). Financial literacy and the need for financial education: Evidence and implications. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics, 155(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/S41937-019-0027-5/FIGURES/2

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/JEL.52.1.5

Lyons, A. C., Kass-Hanna, J., & Fava, A. (2022). Fintech development and savings, borrowing, and remittances: A comparative study of emerging economies. Emerging Markets Review, 51(A), 100842. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EMEMAR.2021.100842

Méndez-Prado, S. M., Rodriguez, V., Peralta-Rizzo, K., Everaert, P., & Valcke, M. (2023). An assessment tool to identify the financial literacy level of financial education programs participants’ executed by Ecuadorian financial institutions. Sustainability, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/SU15020996

Nguyen, T. A. N. (2022). Does financial knowledge matter in using fintech services? Evidence from an emerging economy. Sustainability, 14(9), 5083. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU14095083

Nyrhinen, J., Sirola, A., Koskelainen, T., Munnukka, J., & Wilska, T. A. (2024). Online antecedents for young consumers’ impulse buying behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 153, 108129. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2023.108129

Okello Candiya Bongomin, G., Yosa, F., & Mpeera Ntayi, J. (2021). Reimaging the mobile money ecosystem and financial inclusion of MSMEs in Uganda: Hedonic motivation as mediator. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(11), 1608–1628. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-09-2019-0555/FULL/PDF

Oksanen, A., Savolainen, I., Sirola, A., & Kaakinen, M. (2018). Problem gambling and psychological distress: A cross-national perspective on the mediating effect of consumer debt and debt problems among emerging adults. Harm Reduction Journal, 15(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12954-018-0251-9/TABLES/6

Ozili, P. K. (2020). Theories of financial inclusion. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.3526548

Palfrey, J., & Gasser, U. (2011). Born digital: Understanding the first generation of digital natives. Read How You Want. https://books.google.com/books/about/Born_Digital.html?hl=id&id=wWTI-DbeA7gC

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Potrich, A. C. G., & Vieira, K. M. (2018). Demystifying financial literacy: A behavioral perspective analysis. Management Research Review, 41(9), 1047–1068. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-08-2017-0263

Rahmadyanto, B., & Ekawaty, M. (2023). Tren Pinjaman Online Dalam Milenial: Telaah Kontributor Internal Dan Eksternal. Journal of Development Economic and Social Studies, 2(2). https://jdess.ub.ac.id/index.php/jdess/article/view/157

Sanga, B., & Aziakpono, M. (2024). FinTech developments and their heterogeneous effect on digital finance for SMEs and entrepreneurship: Evidence from 47 African countries. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 17(7), 127–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-09-2023-0379

Sarma, M., & Pais, J. (2011). Financial inclusion and development. Journal of International Development, 23(5), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1002/JID.1698

Savolainen, I., Oksanen, A., Kaakinen, M., Sirola, A., Zych, I., & Paek, H. J. (2021). The role of online group norms and social identity in youth problem gambling. Computers in Human Behavior, 122, 106828. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHB.2021.106828

Stiglitz, J. E. (2017). The revolution of information economics: The past and the future (NBER Working Paper 23780). https://doi.org/10.3386/W23780

Tay, L. Y., Tai, H. T., & Tan, G. S. (2022). Digital financial inclusion: A gateway to sustainable development. Heliyon, 8(6), e09766. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E09766

Teo, T., Kabakçı Yurdakul, I., & Ursavaş, Ö. F. (2016). Exploring the digital natives among pre-service teachers in Turkey: A cross-cultural validation of the Digital Native Assessment Scale. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(6), 1231–1244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.980275

Wang, Y., Pan, J., Xu, Y., Luo, J., & Wu, Y. (2022). The determinants of impulsive buying behavior in electronic commerce. Sustainability, 14(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/SU14127500

Xiao, J. J., & O’Neill, B. (2016). Consumer financial education and financial capability. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 40(6), 712–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/IJCS.12285

Xiao, J. J., & Porto, N. (2017). Financial education and financial satisfaction: Financial literacy, behavior, and capability as mediators. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(5), 805–817. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-01-2016-0009/FULL/XML

Yana, N., & Setyawan, I. R. (2023). Do hedonism lifestyle and financial literacy affect students’ personal financial management? International Journal of Application on Economics and Business, 1(2), 880–888. https://doi.org/10.24912/IJAEB.V1I2.880-888