Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies ISSN 2029-4581 eISSN 2345-0037

2025, vol. 16, no. 2(33), pp. 435–461 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2025.16.19

Consumers’ Nostalgic Re-Engagement with Media in Emerging Markets: Emotional Needs, Content Overload, and Exposure

Rohit Yadav (Corresponding author)

IILM University, Greater Noida, India

rohit13885@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7573-8005

Linda Hollebeek

Sunway University, Sunway Business School, Malaysia

Teng Yew Huat Endowed Chair of Marketing

Vilnius University, Lithuania Professor of Marketing

Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia Professor of Marketing

Umeå University, Sweden, Guest Professor

University of Johannesburg, South Africa Distinguished Visiting Professor

lindah@sunway.edu.my

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1282-0319

Algis Gaižutis

Vilnius University, Lithuania

algis.gaizutis@evaf.vu.lt

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Mohit Yadav

O.P. Jindal Global University, India, Professor, JGBS

Visiting Scholar, International School, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam

mohitaug@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9341-2527

https://ror.org/03j2ta742

Abstract. Grounded in uses-and-gratifications (U&G) theory, this research examines how millennials (Gen Y) nostalgically re-engage with media content and its outcomes in the emerging market context of India. The authors posit that nostalgia serves as both an emotional driver and a coping mechanism for digital overload, extending U&G theory by incorporating socially moderated gratifications beyond individual motives. Drawing on survey data (n=510) and using structural equation modeling to analyze the data, the authors find that while emotional needs and time of exposure boost nostalgic media engagement, perceived content overload reduces it. This engagement, in turn, enhances social sharing and emotional content attachment, with social connectedness moderating this effect. By showing that gratifications are not just individual (but also socially moderated) and by theorizing nostalgia as a coping mechanism against digital overload, the findings underscore that nostalgic re-engagement fulfils dual personal/social roles. Overall, the results detail the pathways and moderating factors influencing nostalgic media re-engagement, offering novel insight into the effect of individual motivations and social interactions on content consumption. Finally, the results reveal pertinent managerial implications, e.g., by suggesting the importance of reducing content overload (e.g., through curated recommendations), fostering social bonding via user-generated content, and incorporating nostalgic features like “memory lanes” and throwback content.

Keywords: nostalgia, consumer engagement, uses-and-gratifications theory, generation Y (Gen Y), millennials, emotional needs

Received: 4/7/2025. Accepted: 28/10/2025

Copyright © 2025 Rohit Yadav, Linda Hollebeek, Algis Gaižutis, Mohit Yadav. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

1. Introduction

Technological advances have yielded new consumer engagement opportunities through platforms like social media and streaming services (e.g., Instagram, Netflix, or YouTube; Hollebeek & Macky, 2019; Kumar, Shankar et al., 2025). Contemporary media environments offer rich content options (Hussain et al., 2025), challenging the development of enduring emotionally resonant relationships with their audiences (Arya et al., 2025).

Gen Y (born 1981–1996) has transitioned from traditional to digital media, rendering them a unique segment to explore in terms of their nostalgic engagement (Kantar, 2020). In the collectivist emerging market context of India, exploration of nostalgia is particularly important given the people’s socially shared, community-oriented experience, distinct from Gen Y in Western, individualist settings (Hollebeek, 2018). Unlike Western cohorts, India’s Gen Y grew up in a hybrid analog–digital ecosystem within a collectivist society, rendering their nostalgic engagement uniquely socially shared and culturally embedded. Gen Y therefore represents an important market segment in this context that will tend to not only reminisce about the more traditional media environment in their younger years (e.g., “Remember when they used to get excited about the next weekly episode of our favorite television series?”; Santini et al., 2023), but they have also acquired fluency and digital literacy with new media (Prensky, 2001; Rather & Hollebeek, 2021), illustrating its unique position among current generational cohorts.

Gen Y actively re-engages with nostalgic media, investing their personal resources in content that evokes past emotions (Hollebeek et al., 2019; Schivinski et al., 2016; Demsar & Brace, 2017). Nostalgia, a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past (e.g., for a period/place with happy associations), has been widely recognized to influence consumer behavior (Holbrook & Schindler, 1991; Wildschut et al., 2006). For example, throw-back television series from the 1980s and 90s like Friends, The Love Boat, The Nanny, or Bollywood movies still receive air time, allowing them to continue engaging and fostering affect-laden connections with their viewers, who (in the case of Gen Y audiences) are likely to have first been exposed to this content in their formative years (Goulding, 1999). Relatedly, nostalgic media content refers to content consumed during one’s formative years (childhood/adolescence) that evokes positive memories. In what follows, the authors argue that nostalgic media content may serve as a buffer against content overload, offering psychological relief and familiarity in saturated digital environments.

Despite the significance of nostalgia, research on its impact on media engagement and emotional attachment remains limited (Barauskaitė & Gineikienė, 2017). For example, why do some individuals develop more profound emotional connections to nostalgic content (vs. others)? What differentiates the present study is its focus on Indian Gen Y in a collectivist, emerging market context, where nostalgia is not only personal but also socially shared. Further, the authors view nostalgia as a coping pathway against digital content overload, extending uses-and-gratifications (U&G) theory from individual motives to socially moderated processes.

This study addresses three key literature-based gaps. First, while nostalgia has been widely studied in Western contexts, little is known about how it operates in emerging markets like India. Second, while nostalgia’s emotional role has been established, its potential role as a coping mechanism (against content overload) remains under-explored. Third, while U&G theory highlights individual-level motives, the moderating influence of social connectedness in shaping nostalgic media re-engagement is yet to be tested. Addressing these gaps, this research addresses the following research questions (RQs): (1) What key consumer and content characteristics drive Gen Y’s nostalgic re-engagement with media content? (2) How does consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with media content influence their social sharing and emotional content attachment? and (3) Does social connectedness moderate the effect of consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with media content on (a) social sharing, and (b) emotional attachment?

This article makes the following contributions to the nostalgic consumption and media engagement literature. First, the study breaks new ground by (a) contextualizing nostalgia in a collectivist emerging market (India) among Gen Y, (b) theorizing nostalgia as a stress-relief pathway against content overload, and (c) expanding U&G theory to include socially moderated gratifications through the lens of social connectedness. This study tests how emotional needs, content overload, and time of exposure influence nostalgic re-engagement and its effects on social sharing and emotional attachment. These three predictors were selected as they represent distinct domains: (a) psychological (emotional needs), (b) contextual/environmental (perceived content overload), and (c) behavioral exposure (time of exposure). Together, they capture the core dimensions that are most salient for Indian Gen Y’s nostalgic media use, balancing parsimony with theoretical relevance. The findings provide important insight for academics and marketers on optimizing nostalgia-driven strategies.

Second, the authors explore the moderating role of consumers’ social connectedness in the effect of their nostalgic re-engagement with media content on their (a) social sharing, and (b) emotional content attachment, as corroborated by the findings. Specifically, higher social connectedness is found to strengthen the effect of nostalgic re-engagement. The advancement of insight into these associations matters, as it highlights the strategically pertinent role of consumers’ social connectedness in leveraging positive outcomes of their nostalgic re-engagement with media content. In other words, the proposed benefits of consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement will be realized for those displaying high (vs. low) social connectedness, in particular.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Uses-and-Gratifications Theory

Uses-and-Gratifications (U&G) theory explains how consumers engage with media to fulfil psychological needs (Katz et al., 1973). U&G theory frames media engagement as an intentional pursuit of psychological needs (Block et al., 2016), rendering its suitability for examining consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with specific media content. Accordingly, the proposed research model focuses on three theoretically grounded antecedents: emotional needs (psychological drivers), perceived content overload (contextual deterrent), and time of exposure (behavioral reinforcement), which, collectively, represent the most theoretically salient drivers of nostalgic re-engagement. Correspondingly, U&G theory has been previously applied to explain or predict nostalgia in media consumption (Lei et al., 2023; Hawk, 2020).

U&G theory assumes that consumers intentionally choose specific media based on their needs (Katz et al., 1973), which (when effective) will yield their satisfaction and attachment (Ruggiero, 2000). The theory categorizes media needs as cognitive (knowledge-seeking), affective (emotional relief), identity (self-reflection), social (bonding), and escapism (distraction; Rather et al., 2024). The authors suggest that nostalgic media content, the content consumed during one’s formative years (childhood and adolescence) that evokes positive memories, reaffirms consumers’ personal and social identity (Shao et al., 2015). For Indian millennials, nostalgic media content tends to include 1990s–2000s Bollywood films, iconic TV series like Shaktimaan and Malgudi Days, music albums and video games from that era. It may also extend to enduring cultural heritage, such as Doordarshan broadcasts or folk songs, which function as collective memory anchors.

2.2 Nostalgia Marketing

Nostalgia marketing leverages sentimental connections to enhance brand engagement and loyalty (Hartmann & Brunk, 2019). Positive emotions tend to result from nostalgia, as it is likely to reinforce brand familiarity and help build brand attachment (Holbrook & Schindler, 1991; Marchegiani & Phau, 2011). Streaming platforms or brands like Netflix and Nintendo have successfully revived nostalgic content to strengthen consumers’ engagement. For example, while Stranger Things (Netflix) leveraged 1980s aesthetics, Nintendo relaunched its Classic Console to revive childhood gaming experiences, and Coca-Cola revived its vintage ad campaigns (e.g., 1990s jingles). These examples illustrate the commercial power of nostalgia in raising consumer engagement. Nostalgia thus plays a crucial role in shaping consumer behavior and brand attachment (Batcho, 2013).

2.3 Social Media Engagement

Social media engagement captures behavior including likes, shares, and comments on digital content (Brodie et al., 2013; Hollebeek et al., 2014; Waqas et al., 2025). Nostalgic content tends to enhance engagement, as users find joy in reminiscing about past media and sharing these experiences within their online communities (Sedikides et al., 2008; Yim et al., 2021; Batcho, 2013; Thadikaran & Singh, 2024). However, excessive content availability can weaken nostalgic engagement (Montag et al., 2022; Tian et al., 2025; Santiago et al., 2025; Moriuchi et al., 2025). Understanding these dynamics helps marketers and media platforms curate nostalgic content that fosters meaningful digital interactions while mitigating content fatigue.

Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) posits that individuals derive part of their self-concept from group memberships. Nostalgic media strengthens this identity by reviving shared cultural memories and collective experiences. In collectivist societies like India, nostalgia is not just an individual sentiment but a communal one as family TV shows, Bollywood songs, and shared school-day media often become cultural anchors. This provides the theoretical basis for hypothesizing that social connectedness moderates the relationship between nostalgic re-engagement and consumer outcomes.

3. Hypotheses Development

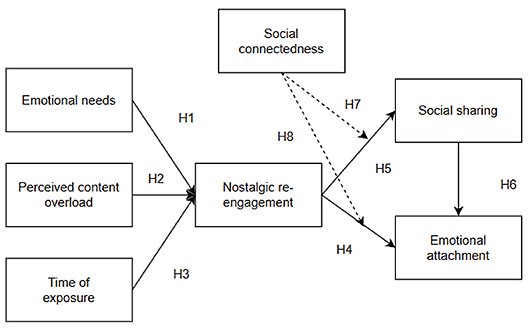

Drawing on U&G theory, the authors develop a conceptual framework and an associated set of hypotheses, as shown in Figure 1 and discussed further below.

Figure 1

Conceptual Framework

3.1 Effect of Emotional Needs on Nostalgic Re-Engagement with Media Content

U&G theory suggests that consumers selectively choose their media to fulfil their emotional needs (e.g., entertainment/social affiliation needs; Rubin, 2009). Needs may entail a nostalgic aspect, including their desire to reconnect with and rekindle feelings of the past (e.g., by reminiscing about their youth; Pennebaker & Alcaster, 2011; Wildschut et al., 2006). Prior research supports the role of nostalgia in fulfilling psychological needs, demonstrating its capacity to foster emotional resilience and enhance coping mechanisms (Batcho, 2013; Holbrook, 2021; Hollebeek et al., 2023). Nostalgia fosters emotional stability, particularly in uncertain times (Hepper et al., 2022). Emotional needs, defined as psychological requirements for emotional fulfilment, stability, and well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), serve as a key driver of consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with media content. Gen Y engages with nostalgic media for comfort and belonging (Davis, 1979; Routledge et al., 2013). Using U&G theory, the authors propose that emotional needs are a central predictor of nostalgic re-engagement with media content (FioRito & Routledge, 2020):

H1: Consumers’ emotional needs positively influence their nostalgic re-engagement with media content.

3.2 Effect of Perceived Content Overload on Re-Engagement with Media Content

Excessive digital content can overwhelm consumers, leading to engagement dormancy (Hollebeek et al., 2023; Brodie et al., 2013). For example, continuous content streams may overwhelm consumers or exhaust their (e.g., cognitive) processing abilities (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000), reducing their engagement with digital content (Gottlieb & Yu, 2021; Spiteri, 2021). Perceived irrelevant content may reduce engagement and emotional connection (Hollebeek & Macky, 2019; Mustak et al., 2024). That is, content-related fatigue brought about by perceived content overload is expected to reduce the likelihood of nostalgia-driven re-consumption (Montag et al., 2022; Tian et al., 2025; Santiago et al., 2025). The authors posit:

H2: Consumers’ perceived content overload negatively influences their nostalgic re-engagement with media content.

3.3 Effect of Time of Exposure on Re-Engagement with Media Content

Greater exposure enhances familiarity and positive associations (Zajonc, 1968). Extended exposure deepens emotional engagement with nostalgic content (Schindler & Holbrook, 2003). Correspondingly, recent investigations suggest that sustained exposure to nostalgic media content deepens emotional engagement and reinforces positive associations (Wulf et al., 2018; Chou & Singhal, 2017; Rai et al., 2023). Familiarity effects that are amplified by repeated exposure tend to evoke progressively strengthening emotional resonance, rendering nostalgic media content more appealing to users over time (Wang & Santini, 2023). The authors propose:

H3: Time of exposure positively influences consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with media content.

3.4 Media Re-Consumption, Social Sharing, and Emotional Attachment

Examining the impact of nostalgic re-engagement on emotional attachment is important. Emotional attachment refers to the bond formed between individuals and objects (e.g., media content, brands, or nostalgic experiences) due to repeated interactions that provide comfort, satisfaction, or a sense of security (Rathnayake, 2021). Emotional attachment forms through repeated interactions with nostalgic media (Thomson et al., 2005). Such emotional attachment forms when exposure to nostalgic media content that can offer relief or pleasure (Thomson et al., 2005) induces repeated interactions that provide comfort or satisfaction. Nostalgia fosters long-term brand loyalty (Stanton et al., 2021; Rathnayake, 2021). The authors propose:

H4: Nostalgic re-engagement with media content positively influences emotional content attachment.

Prior research shows that nostalgic experiences promote a sense of belonging and continuity of identity (Sedikides et al., 2008), which can motivate individuals to express and validate those emotions by posting or resharing content. Huang et al. (2016) found that nostalgia-driven consumption leads to increased word-of-mouth and sharing behavior, especially when individuals wish to reaffirm shared values or cultural references with their peers. Additionally, in digital environments, nostalgic re-engagement often takes the form of sharing old songs, movies, or memories as social currency, reinforcing communal bonds (Gibbs et al., 2014). The authors propose:

H5: Consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with media content positively influences their social sharing.

According to social identity theory, sharing content enables individuals to express identity and seek validation from peers, which can strengthen emotional attachment to the content that symbolizes or supports their social self (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Moreover, social sharing creates engagement loops through feedback mechanisms such as likes, comments, and reshares, thereby enhancing psychological ownership and emotional resonance with the content (Shao, 2009; Kim & Johnson, 2016). This is particularly evident for emotionally charged content, such as nostalgic or inspirational media, as sharing becomes a form of co-creation and co-experience, which in turn fosters stronger emotional attachment (Mingione et al., 2020). Thus, the more consumers share content that resonates with them, the more emotionally attached they become to it. The authors posit:

H6: Consumers’ social sharing positively influences their emotional content attachment.

3.5 The Moderating Role of Social Connectedness

Social connectedness, an individual’s perceived sense of closeness, belonging, and positive relationships with others (Lee & Robbins, 1995), is likely to enhance group identity through nostalgic content (Yang et al., 2021). Prior research suggests that social connectedness facilitates social sharing, given its role in interpersonal interactions and psychological security (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). For the same reason, social connectedness is likely to influence emotional attachment. Social identity theory posits that individuals define themselves by their group memberships. Nostalgic content reinforces this sense of belonging to the in-group (e.g., by reviving shared cultural touchpoints). In collectivist India, nostalgia is often communal (e.g., family TV series/Bollywood music), justifying the proposed moderating role of social connectedness. Specifically, the authors examine how social connectedness moderates nostalgic re-engagement effects on sharing and attachment.

3.5.1 Moderating Role in the Effect of Nostalgic Re-Engagement on Social Sharing

Social sharing refers to the explicit expression of nostalgia through verbal or digital communication, where individuals share past-related content with others (Berger & Milkman, 2012). Prior research suggests that individuals with high social connectedness are more likely to engage in in-group sharing behavior, strengthening group identity and fostering social cohesion (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Highly connected individuals share nostalgic content to reinforce memories and bonds (Hepper & Connelly, 2021). Moreover, prior work indicates that digital nostalgia enhances community bonding, as individuals actively seek to relive and share their collective experiences (Sedikides & Wildschut, 2019). The authors propose:

H7: Social connectedness moderates the effect of consumers’ re-engagement with media content on their social sharing, such that the relationship is stronger for those exhibiting high (vs. low) social connectedness.

3.5.2 Moderating Role in the Effect of Nostalgic Re-Engagement on Emotional Attachment

Emotional attachment refers to an individual’s internal, personal connection with media content, characterized by affective bonds and enduring emotional resonance (Thomson et al., 2005). Unlike social sharing, which is external and expressive, emotional attachment is internal and experiential, rooted in repeated exposure to nostalgic media (Bowlby, 1982). Social connections enhance emotional attachment (Seppala et al., 2013). This effect is further amplified in digital nostalgia, where social connectedness enhances emotional intensity, making nostalgic re-engagement more meaningful (Lee, 2023). For highly connected individuals, nostalgic media not only evokes personal memories but also reinforces emotional bonds through collective nostalgia. The authors propose:

H8: Social connectedness moderates the effect of consumers’ re-engagement with media content on emotional attachment, such that the relationship is stronger for those exhibiting high (vs. low) social connectedness.

4. Methodology

4.1 Research Context

This study’s target population is Gen Y (millennials) in India, comprising individuals born between 1981–1996, who are approximately 27–42 years old. The study selected Gen Y, given its unique position at the intersection of the shift from analog to digital media. Gen Y is appropriate to serve our research purpose, as it has experienced both traditional and digital media, rendering them ideal to examine their nostalgic engagement. The study selected the emerging market context of India, given its expected richness for studying nostalgia. Specifically, as a collectivist culture (Hollebeek, 2018), Indian consumers are anticipated to experience nostalgia not only at the individual level, but also collectively or socially. Given its emerging nature, India has also been recognized as a mobile-first market, in which customer/firm interfaces (e.g., websites) are first designed for smaller mobile screens, followed by those for larger (e.g., desktop) devices (vs. the other way round; Khan et al., 2023). Macro-level cultural dimensions (e.g., collectivism–individualism) were excluded to maintain parsimony, though they provide a meaningful backdrop for interpreting nostalgic engagement in India.

4.2 Sampling Procedures

Stratified random sampling was used (Creswell, 2013). Participants were recruited via alumni networks, professional organizations, and social media platforms. Strata were applied to ensure gender, occupational, and city-tier diversity (see Table 1). The data was collected from major Indian urban and tier-2 cities, which were selected for their high digital adoption and diverse socio-cultural landscape (Abbasi et al., 2024).

A sample of 510 valid responses was collected, exceeding structural equation modeling with AMOS guidelines (>400 for multi-construct models; Hair et al., 2019). India was chosen for its high social media engagement (Statista, 2023), strong nostalgia trends (Mukhopadhyay, 2024), and Gen Y’s workforce presence (Met, 2025). A priori power analysis using G*Power indicated that a minimum of 384 cases was required to detect medium effect sizes (f² = 0.15) at 0.95 power and α = 0.05 for our model complexity. The sample size thus exceeds both the recommended SEM thresholds and power analysis benchmarks, ensuring its robustness.

The survey was designed to appeal to Gen Y consumers because of their visual nostalgia triggers (i.e., questions referenced popular 90s and early 2000s content, like TV shows, music, Bollywood, video games). Digital-native phrasing was used to enhance engagement.

Table 1

Demographic Respondent Profile

|

Category |

Sub-category |

Percentage |

Total number |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender |

Male |

47% |

239 |

|

Female |

53% |

271 |

|

|

Education level |

High school |

12% |

61 |

|

Undergraduate |

53% |

270 |

|

|

Postgraduate |

35% |

178 |

|

|

Household income |

Below 30K Rupees |

12% |

61 |

|

30-60K |

28% |

143 |

|

|

60-100K |

32% |

163 |

|

|

> ₹100K |

28% |

143 |

|

|

Occupation |

Corporate/private sector |

40% |

204 |

|

Government/public sector |

15% |

77 |

|

|

Self-employed |

20% |

102 |

|

|

Student |

15% |

77 |

|

|

Freelance/contract |

5% |

26 |

|

|

Unemployed |

5% |

26 |

|

|

Preferred platforms |

YouTube |

33% |

168 |

|

Netflix |

27% |

137 |

|

|

Amazon Prime |

18% |

92 |

|

|

|

15% |

77 |

|

|

Others |

7% |

36 |

|

|

Social media usage |

Several times a day |

50% |

255 |

|

Daily |

30% |

153 |

|

|

Weekly |

15% |

77 |

|

|

Rarely |

5% |

26 |

|

|

Favorite media formats |

TV shows |

28% |

143 |

|

Movies |

42% |

214 |

|

|

Music |

18% |

92 |

|

|

Games |

7% |

36 |

|

|

Social media content |

5% |

26 |

|

|

Total |

100% |

510 |

4.3 Measures

The constructs were measured using five-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The survey items were adapted from established, validated scales (Sedikides et al., 2008; Thomson et al., 2005) and contextualized to Indian millennials’ nostalgic media. To ensure cultural relevance, references to popular 1990s–2000s content (e.g., Bollywood films, TV serials such as Shaktimaan, music albums, Nintendo video games) were incorporated into examples shown in the questionnaire. An overview of the measurement items is provided in Table 2. To assess the potential existence of common method bias (CMB), Harman’s one-factor test was conducted. The first factor accounted for less than 40% of the variance, indicating that CMB was not a serious concern in this study (Harman, 1976). In order to improve the efficiency of respondents and their contextual fit, some of the multi-item scales were slightly reduced after piloting. The redundant items and the ones that had low factor loadings (less than 0.40) were dropped without compromising conceptual integrity (Hair et al., 2019). All the things that are held reflect on the theoretical meaning of the original constructs. An example of this is: Social Connectedness scale (Lee & Robbins, 1995) was reduced to 4 items after eliminating redundant questions which were similar to the Emotional Needs construct in our culture. To increase the content validity of the scale, the Emotional Attachment scale (Thomson et al., 2005) was extended to 4 items to incorporate an item that cited, specifically, the inimitable value of childhood media that was considered pertinent to the nostalgic consumption in the Indian Gen Y context.

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1 Exploratory Factor Analysis

Since a number of measurement items were contextualized to suit the Indian millennial media context, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed to ascertain item loadings and dimensional organization followed by confirmatory evaluation. This initial EFA was a diagnostic measure to make sure that modified scales had construct validity in a culturally specific environment in line with Hair et al. (2019). The authors first conducted an EFA to test the validity of the constructs and ensure that items were loading properly onto their respective factors, as shown in Table 2. The authors used principal component analysis with varimax rotation to identify the underlying structure of the data. The loadings are indicative of the extent to which each item contributes to its respective underlying factor. A loading of >0.4 suggests a strong association with the factor (Field, 2013). The observed loadings on each factor exceeded the value of 0.69, suggesting the items have a relatively strong relationship with their respective latent construct (Hair et al., 2014). No significant cross-loadings were found. Therefore, the factors loaded heavily onto their respective factor. Moreover, the KMO value (0.812) indicated the adequacy of the results.

Table 2

Exploratory Factor Analysis Results

|

Variable |

Item |

Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

|

Emotional needs Sedikides et al. (2008), Wildschut et al. (2006) |

“I seek out media that feels familiar when stressed.” |

0.73 |

|

“During challenging times, I find comfort in re-watching media.” |

0.78 |

|

|

“I use media to help manage feelings of loneliness.” |

0.81 |

|

|

“When feeling lonely, I turn to past media for comfort.” |

0.69 |

|

|

Perceived content overload Eppler & Mengis (2004), Keller & Staelin (1987) |

“I feel overwhelmed by the amount of new media.” |

0.75 |

|

“There is so much new content that it’s difficult to decide.” |

0.8 |

|

|

“The vast amount of media makes it hard to appreciate older content.” |

0.72 |

|

|

“New media options make it hard to choose what to engage with.” |

0.77 |

|

|

Time of exposure Zillmann & Bryant (1985), Bartsch & Viehoff (2010) |

“How often do you spend time re-watching media from your past?” |

0.82 |

|

“I tend to watch nostalgic content over long periods.” |

0.76 |

|

|

“I engage with nostalgic media regularly over long periods.” |

0.79 |

|

|

“When revisiting nostalgic media, I watch for extended periods.” |

0.74 |

|

|

Social connectedness Lee & Robbins (1995), Baumeister & Leary (1995) |

“I feel connected to others when we share nostalgic experiences.” |

0.81 |

|

“Sharing nostalgic media enhances my sense of belonging.” |

0.77 |

|

|

“I enjoy discussing nostalgic media as it brings us closer.” |

0.83 |

|

|

“I feel a stronger connection to nostalgic media when shared.” |

0.8 |

|

|

Nostalgic Re-engagement Goulding (2002), Zhao et al. (2019) |

“I frequently re-watch shows or movies I enjoyed in the past.” |

0.78 |

|

“I go back to familiar media rather than exploring new content.” |

0.72 |

|

|

“I revisit media that reminds me of positive experiences.” |

0.81 |

|

|

“I prefer re-engaging with media that feels familiar.” |

0.77 |

|

|

Social sharing Tanskanen & Danielsbacka (2012), Belk (1988) |

“I often share nostalgic media experiences with friends.” |

0.79 |

|

“Discussing nostalgic content makes it more enjoyable.” |

0.82 |

|

|

“Sharing past media strengthens my connection with others.” |

0.8 |

|

|

“I feel more connected to nostalgic media when I share it.” |

0.76 |

|

|

Emotional attachment Thomson et al. (2005), Russell & Levy (2012) |

“I feel a strong emotional connection to past media.” |

0.85 |

|

“The media I grew up with holds a special place in my heart.” |

0.83 |

|

|

“Certain childhood media feels irreplaceable to me.” |

0.78 |

|

|

“I feel deeply attached to media from my past.” |

0.82 |

Note. All measurement items were adapted from previously validated scales; citations refer to the original conceptual sources from which the constructs were derived.

5.2 Measurement Model Results

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) demonstrated excellent model fit (χ² = 425.81, df = 350, p = 0.06; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.05, p< = 0.09; SRMR = 0.04), exceeding conventional thresholds (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Construct reliability and validity were determined by assessing the internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the constructs (i.e., by using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and the Average Variance Extracted; Hair et al., 2014). All factor loadings exceeded 0.70, CR values were > 0.80, and AVE values were > 0.50, confirming convergent validity. Discriminant validity was established using the Fornell–Larcker criterion.

5.2.1 Reliability

Construct reliability was analyzed using Cronbach’s alpha and Composite reliability (CR) (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). All constructs show values greater than 0.70 for Cronbach’s Alpha. As shown in Table 4, each fall in the acceptable to high range: 0.79 (Perceived content overload), and 0.88 for emotional attachment. Similarly, the composite reliability values range from 0.82 to 0.91, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70, further supporting construct reliability. The results suggest that the constructs consistently measure the intended latent variables (Hair et al., 2010).

5.2.2 Convergent Validity

To examine convergent validity, the AVE produced suitable values. As shown in Table 3, all constructs have an AVE > 0.50, with the lowest value (0.60) being attained for social sharing, and the highest value (0.68) being attained for emotional attachment. The AVEs suggest that over 50% of the variance in the indicators is explained by the respective constructs, thus providing satisfactory convergent validity. Further, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) values range from 0.41 to 0.53 (which is close to each construct’s AVE value), validating the convergent and construct validity of the measurement model.

5.2.3 Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was tested using both the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) and the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio (Henseler et al., 2015), as shown in Table 3. According to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square root of each construct’s AVE (i.e., diagonal values) exceeded its respective inter-construct correlations (i.e., off-diagonal values) for all constructs. For instance, the square root of the AVE for emotional needs (0.62) was greater than its correlation with perceived content overload (0.31) and time of exposure (0.34), confirming discriminant validity. Moreover, the HTMT ratios were examined as a more stringent measure of discriminant validity. All HTMT values were found lower than the conservative threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015), further confirming that the constructs exhibit sufficient discriminant validity. Overall, the analysis demonstrates the model’s acceptable internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity across both Fornell-Larcker and HTMT criteria.

Table 3

Validity and Reliability Testing Results

|

Constructs |

EN |

PCO |

TE |

SC |

MRC |

SS |

EA |

CA |

CR |

AVE |

MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Emotional needs (EN) |

0.62 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.81 |

0.84 |

0.62 |

0.48 |

|

Perceived content overload (PCO) |

0.31 |

0.61 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.79 |

0.82 |

0.61 |

0.41 |

|

Time of exposure (TE) |

0.34 |

0.27 |

0.65 |

|

|

|

|

0.85 |

0.88 |

0.65 |

0.52 |

|

Social connectedness (SC) |

0.29 |

0.25 |

0.32 |

0.63 |

|

|

|

0.83 |

0.85 |

0.63 |

0.45 |

|

Media Re-engagement (MRC) |

0.35 |

0.29 |

0.36 |

0.31 |

0.66 |

|

|

0.86 |

0.89 |

0.66 |

0.51 |

|

Social sharing (SS) |

0.3 |

0.26 |

0.33 |

0.34 |

0.38 |

0.6 |

|

0.8 |

0.83 |

0.6 |

0.44 |

|

Emotional attachment (EA) |

0.37 |

0.3 |

0.39 |

0.36 |

0.42 |

0.41 |

0.68 |

0.88 |

0.91 |

0.68 |

0.53 |

Note. Diagonal values in bold represent squared correlations. CA= Cronbach Alpha, CR= Composite Reliability, AVE = Average Variance Extracted, MSV= Mean Squared Error (MSE).

5.3 Structural Equation Modeling Results

Model fit was assessed using multiple fit indices, with the results indicating strong model fit. Specifically, the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) both exceed the value of 0.90, indicating a good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The RMSEA value (0.05) remains well below the 0.08 threshold, showing excellent fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) also remains below 0.08, further supporting the overall model fit. Model fit indices for the structural model were satisfactory (χ² = 425.81, df = 350, p = 0.06; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.05, p<= 0.09; SRMR = 0.04), indicating close correspondence between the hypothesized and observed covariance structures.

5.4 Hypotheses Testing Results

The authors next tested the hypotheses (see Table 4). The findings reveal that each of these was supported, as discussed further below. To ensure the robustness of the findings, the authors also tested alternative model specifications initially (e.g., excluding non-critical paths). These alternatives yielded poorer fit indices, supporting the stability and robustness of the proposed model.

Table 4

Path Analysis Results

|

Hypothesis |

Standardized |

p-value |

Result |

|---|---|---|---|

|

H1: Emotional needs positively influence nostalgic re-engagement with media content. |

0.68 |

< 0.01 |

Supported |

|

H2: Perceived content overload negatively influences nostalgic re-engagement with media content. |

-0.45 |

< 0.01 |

Supported |

|

H3: Time of exposure positively influences nostalgic re-engagement with media content. |

0.53 |

< 0.01 |

Supported |

|

H4: Nostalgic re-engagement with media content positively influences emotional attachment. |

0.61 |

< 0.01 |

Supported |

|

H5: Nostalgic re-engagement with media content positively influences social sharing. |

0.57 |

< 0.01 |

Supported |

|

H6: Social sharing positively influences emotional attachment. |

0.48 |

< 0.01 |

Supported |

|

H7: Social connectedness moderates the effect of nostalgic re-engagement with media content on social sharing. |

0.28 |

< 0.05 |

Supported |

|

H8: Social connectedness moderates the effect of nostalgic re-engagement with media content on emotional attachment. |

0.34 |

< 0.05 |

Supported |

Emotional needs significantly influence nostalgic re-engagement with media content (β = 0.68, p < 0.01), in line with U&G theory, as nostalgic media may provide comfort and emotional support. Conversely, perceived content overload is found to negatively impact nostalgic re-engagement with media content (β = -0.45, p < 0.01), as cognitive fatigue from excessive content may diminish consumers’ interest in familiar media. Moreover, time of exposure was found to positively affect nostalgic re-engagement with media content (β = 0.53, p < 0.01), with prolonged engagement fostering familiarity and stronger sentimental ties. Nostalgic re-engagement with media content significantly enhances emotional content attachment (β = 0.61, p < 0.01), deepening bonds over time by solidifying nostalgic re-engagement. It also promotes social sharing (β = 0.57, p < 0.01), fostering community and collective identity, in line with U&G theory’s social motives for media or content consumption (Block et al., 2016). Social sharing further strengthens emotional content attachment (β = 0.48, p < 0.01) by reinforcing shared nostalgic experiences.

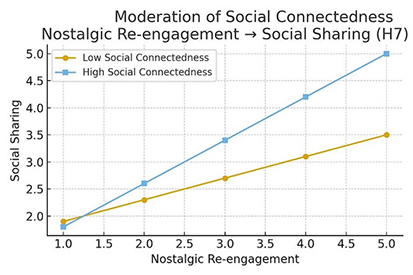

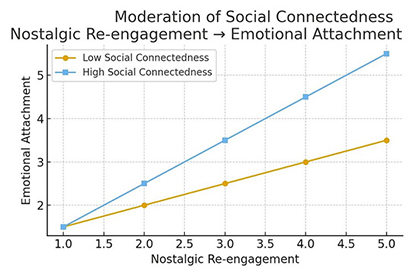

Moderation (H7 and H8) was tested using a Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) framework in AMOS, consistent with prior applications of group-comparison techniques in CB-SEM (Hair et al., 2019) and empirical work employing the S-O-R paradigm (Yadav & Mahara, 2020). This involved conducting a median split on the latent moderator variable (Social Connectedness) to create two groups (high vs. low social connectedness). We then compared the unconstrained model (where paths were allowed to vary) to the constrained model (where the paths were set equal) to assess the significance of the difference using the Δχ2 statistic, thereby testing the path differences in the latent structural model. This approach avoids issues of measurement error common in factor score multiplication and provides robust estimates of moderating effects. Moderation analysis confirms the role of social connectedness in impacting the effect of nostalgic re-engagement on social sharing (β = 0.28, p < 0.05), with a stronger effect being observed for those displaying high (vs. low) social connectedness (total effect β = 0.86; high connectedness slope = 0.68, vs. low = 0.45). Similarly, social connectedness was found to moderate the effect of nostalgic re-engagement with media content on emotional content attachment (β = 0.34, p < 0.05), with even greater total effects (β = 0.95; high connectedness slope = 0.75, vs. low = 0.50). These findings emphasize the critical role of social bonds in enhancing consumers’ emotional and social nostalgic re-engagement with media content, as shown in Table 5. The moderating effect of social connectedness was found to be significant for both relationships. To aid interpretation, interaction plots were generated (see Figures 2 and 3), which illustrate that the positive effects of nostalgic re-engagement on social sharing and emotional attachment are stronger when social connectedness is high.

Table 5

Moderating Role of Social Connectedness (H7–8)

|

Hypothesis |

Path |

Direct effect |

Indirect effect |

Total effect |

Low social connectedness |

High social connectedness |

p- |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

H7 |

Nostalgic re-engagement with media content — Social Sharing |

0.57 |

0.29 |

0.86 |

0.45 |

0.68 |

< 0.05 |

|

H8 |

Nostalgic re-engagement with media content — Emotional attachment |

0.61 |

0.34 |

0.95 |

0.5 |

0.75 |

< 0.05 |

Figure 2

Moderating Effect of Social Connectedness on the Association of Nostalgic Re-Engagement and Social Sharing

Figure 3

Moderating Effect of Social Connectedness on the Association of Nostalgic Re-Engagement and Emotional Attachment

6. Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

6.1 Discussion

The findings provide significant insight into the drivers and effects of consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with media content. These interpretations are supported by confirmatory factor analysis results that established strong model fit, thereby reinforcing the robustness of the structural relationships. While a plethora of prior studies have addressed consumer engagement (e.g., Kumar, Hollebeek et al., 2025; Brodie et al., 2011), scholarly acumen of their nostalgic re-engagement (e.g., reminiscing by re-engaging with specific media content) remains sparse, warranting the undertaking of this research. Given the power of nostalgia (marketing) to re-engage consumers (Hartmann & Brunk, 2019), the authors expect its findings to hold strategic value.

In line with U&G theory, the results suggest that Gen Y consumers’ emotional needs significantly shape their nostalgic re-engagement with media content, confirming its role as a psychological haven providing comfort and continuity in today’s increasingly fast-paced, stressful lives (Sedikides & Wildschut, 2018). The strong negative correlation between perceived content overload and nostalgic re-engagement indicates that when consumers feel overwhelmed by the range of content choices, they may experience cognitive overload and be unable (or less able) to invest additional cognitive resources in their interactions with specific content (Hollebeek et al., 2019). Overload can paradoxically also amplify nostalgia, as consumers retreat to familiar, comforting content when overwhelmed. This positions nostalgia as a coping pathway in saturated digital environments. These two factors may also interact: Extended exposure could itself increase perceptions of overload, which in turn may dampen nostalgic re-engagement. While not modeled here, this reciprocal relationship represents an important direction for future research.

The positive effect of time of exposure on nostalgic re-engagement with media content suggests that consumers’ re-engagement may sharpen their media awareness, enhance their positive affective responses, and stimulate their media use (Hartmann & Brunk, 2019). Moreover, the significant effect of nostalgic re-engagement with media content on emotional attachment indicates that repeated interactions with nostalgic content deepen emotional bonds, rendering such media an integral part of consumers’ identity and reinforcing the enduring value of nostalgic content in cultivating emotional attachment.

The authors also found that nostalgic re-engagement with media content significantly boosts social sharing. Shared experiences of nostalgic content may strengthen group identity and foster social belonging (Turner et al., 1987; Xiang et al., 2023). Millennials often share nostalgic content on platforms like Instagram or during social gatherings, reinforcing collective memories and social bonds. The positive effect of social sharing on emotional attachment underscores the social construction of nostalgic re-engagement. Sharing nostalgic content raises emotional connections with both content and one’s social circle, revealing nostalgia as a personal and socially mediated phenomenon.

Social connection moderates the effect of nostalgic re-engagement with media content on social sharing on the one hand, and with emotional attachment on the other. Importantly, in collectivist India, nostalgia resonates more strongly at the communal level compared to Western, individualist contexts where nostalgia is often personal. This finding suggests that cultural context shapes both the intensity and social function of nostalgia. These effects are likewise intensified for people scoring high on social connections, indicating that social relationships may boost the degree of positive emotional framing along with consumers’ social interactions. Overall, this study shows how consumer and content factors jointly shape their nostalgic re-engagement with media content, exposing pertinent new insight.

6.2 Theoretical Implications

The findings contribute to the literature by confirming that nostalgia positively impacts both social sharing and emotional attachment. In collectivist emerging market contexts like India, nostalgia often functions at the community level (e.g., shared Bollywood films/family TV shows), while in Western, more individualist contexts, nostalgia tends to be more personally-oriented (e.g., individual hobbies/music). It is therefore key to contextualize the socio-cultural roles of nostalgia. Specifically, nostalgia is found to act as a powerful tool in influencing consumers’ perceptions and stimulating their engagement (Hartmann & Brunk, 2019), rendering the strategic importance of understanding their re-engagement with specific media content in the emerging market context. The study thus explored nostalgic re-engagement with media content in its broader nomological network comprising key antecedents (e.g., time of exposure) and consequences (e.g., emotional content attachment), augmenting acumen of the phenomenon. Our analyses raise important implications for further theory development. For example, what might nostalgic re-engagement with media content dynamics look like in other (e.g., contextual or cultural) settings? How do the behavioral outcomes (e.g., purchase behavior) differ across those exhibiting high (vs. low) nostalgic re-engagement?

Second, the study explored the moderating role of social connectedness (H7-H8), which were both supported. Specifically, more (vs. less) socially connected consumers were found to experience a stronger effect of their nostalgic re-engagement with media content on their (a) social sharing, and (b) emotional content attachment, suggesting this moderator’s strategically important role. These results also offer key implications for further theory development. For example, what is the relative importance of nostalgic re-engagement’s personal (vs. social or communal) role in shaping desired consumer behavior? To what extent does nostalgic re-engagement with media content shape consumers’ social identity?

6.3 Managerial Implications

This research also raises pertinent implications for media companies, marketers, and content creators, particularly in emerging markets. First, the findings can help organizations design strategies to build deeper connections with audiences by understanding nostalgic re-engagement with media content and its key drivers, outcomes, and moderators. Media companies should focus on creating and promoting nostalgic content according to the preferences of consumers with different demographic and psychographic profiles. Memorable media content from their formative years is expected to evoke substantial emotional responses and help build customer loyalty. Facilitating content accessibility (e.g., curated playlists, thematic collections, and personalized recommendations) may help individuals cope with content overload and enhance their re-engagement (Viswanathan et al., 2017).

Second, social media campaigns sharing nostalgic content, group collaboration platforms, and community events can be leveraged to reinforce group identity to enhance the reach and performance of nostalgic content. Adding nostalgic elements to brands can instigate consumers’ energy toward the brand, producing brand loyalty and long-term brand engagement (So et al., 2024). Moreover, shared, collaborative, or communal platforms may provide opportunities for consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement, enabling brands to revive collective experiences through digital communities.

Overall, deploying these strategies is likely to enable organizations to capitalize on consumers’ nostalgia to establish more meaningful and enduring relationships with their audiences in contemporary increasingly cluttered, competitive media environments (Charry et al., 2024). The strategic power of creating shareable nostalgic campaigns and interactive experiences that appeal to Gen Y consumers’ interests and lifestyles should be leveraged, as they are highly involved in digital content. Finally, by using data analytics, data can be sorted according to specific nostalgia trends, targeting particular groups to provide tailored marketing campaigns.

6.4 Limitations and Further Research

Despite its contribution, this research also has limitations that offer additional research avenues. First, consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement is expected to differ across cultural contexts (Hollebeek, 2018), necessitating the replication of our analyses in other cultural settings. Our data is limited to Indian millennials, based on data from urban and semi-urban settings. Future studies are thus advised to compare the studied associations in or across different cultural contexts (e.g., to examine how nostalgic engagement and social connectedness are shaped in different cultural contexts). Moreover, recall bias may influence how participants evaluate nostalgic media, given reliance on self-reports. Relatedly, future research could explore the impact of emerging technologies like virtual, augmented, or mixed reality on consumers’ nostalgic re-engagement with media content (Arya et al., 2025).

Second, while the study explored the modeled associations for Gen Y in the emerging market context of India, replication of our analyses with other generational cohorts (e.g., Baby Boomers/Gen Z) may yield different results, also warranting further exploration. Third, our cross-sectional analyses gauged the modelled constructs at a particular point in time, obscuring insight into their development over time. Therefore, researchers may wish to conduct future longitudinal assessments of the proposed model to track potential changes in the studied constructs and their relationships (So et al., 2024).

References

Abbasi, A., Hollebeek, L., Hassan, M., Ting, D., Salm, E., & Dikcius, V. (2024). The impact of consumer engagement with gamified branded apps on gameful experience in emerging markets: An empirical study. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 15(2), 216–247. https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2024.15.11

Arya, V., Sethi, D., & Hollebeek, L. (2025). Using augmented reality to strengthen consumer–brand relationships: The case of luxury brands. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. 24(2), 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.2419

Barauskaitė, D., & Gineikienė, J. (2017). Nostalgia may not work for everyone: The case of innovative consumers. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 8(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2017.8.1.14195

Bartsch, A., & Viehoff, R. (2010). The Use of Media Entertainment and Emotional Gratification. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 2247–2255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.444

Batcho, K. I. (2013). Nostalgia: Retreat or support in difficult times? The American Journal of Psychology, 126(3), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.3.0355

Baumeister, R., & Leary, M. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Belk, R. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

Berger, J., & Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(2), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0353

Block, M., Malthouse, E., & Hollebeek, L. (2016). Sounds of music: Exploring consumers’ musical engagement. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(6), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2016-1730

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

Brodie, R., Hollebeek, L., Ilic, A., & Juric, B. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions and implications for research in service marketing. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703

Brown, J., & Reingen, P. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1086/209118

Charry, K., Poncin, I., Kullak, A., & Hollebeek, L. (2024). Gamification’s role in fostering user engagement with healthy food-based digital content. Psychology & Marketing, 41(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21892.

Chou, H., & Singhal, D. (2017). Nostalgia advertising and young Indian consumers: The power of old songs. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(3), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2016.11.004

Collins, N., & Feeney, B. (2004). Working models of attachment shape perceptions of social support: Evidence from experimental and observational studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 363–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.363

Creswell, J. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Danielsbacka, M., & Tanskanen, A. O. (2012). Adolescent grandchildren’s perceptions of grandparents’ involvement in the UK: An interpretation from life course and evolutionary theory perspective. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0240-x

Davis, F. (1979). Yearning for yesterday: A sociology of nostalgia. Free Press.

Demsar, V., & Brace-Govan, J. (2017). Sustainable disposal and evolving consumer–product relationships. Australasian Marketing Journal, 25(2), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.04.010

Eppler, M., & Mengis, J. (2004). The concept of information overload: A review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, MIS, and related disciplines. The Information Society, 20(5), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240490507974

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

FioRito, T., & Routledge, C. (2020). Is nostalgia a past or future-oriented experience? Affective, behavioral, social cognitive, and neuroscientific evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 542198. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.542198

Gibbs, M., Meese, J., Arnold, M., Nansen, B., & Carter, M. (2015). #Funeral and Instagram: Death, social media, and platform vernacular. Information, Communication & Society, 18(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.987152

Gineikienė, J. (2013). Consumer nostalgia literature review and an alternative measurement perspective. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 4(2), 112–149. https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2013.4.2.14252

Gottlieb, J., & Yu, A. (2021). Understanding the impact of information overload on cognitive functioning. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 22(10), 703–717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-021-00521-w

Goulding, C. (1999). Heritage, nostalgia, and the “grey” consumer. Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science, 5(6/7/8), 177–199.

Goulding, C. (2002). An exploratory study of age-related vicarious nostalgia and aesthetic consumption. Advances in Consumer Research, 29, 542–546.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis (8th ed.). Pearson.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

Harman, H. (1976). Modern factor analysis (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Hartmann, B., & Brunk, K. (2019). Nostalgia marketing and (re-)enchantment. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(4), 669–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.02.004

H awk, E. (2020). Take those old records off the shelf: A uses and gratifications study of different music platforms (Master’s thesis). Rochester Institute of Technology. https://repository.rit.edu/theses

Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hepper, E., & Connelly, R. (2021). Shared nostalgia as a social glue: Implications for social connectedness. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(4), e12591. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12591

Hepper, E., Wildschut, T., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Nostalgia as a psychological resource: Theory, evidence, and directions for future research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(3), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214221075789

Holbrook, M. (2021). Nostalgia and consumption: Reflections on the past as a resource for the present. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(6), 1423–1434. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1961

Holbrook, M., & Schindler, R. (1991). Echoes of the dear departed past: Some work in progress on nostalgia. Advances in Consumer Research, 18, 330–333.

Holbrook, M., & Schindler, R. (2003). Nostalgic bonding: Exploring the role of nostalgia in the consumption experience. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 3(2), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.127

Hollebeek, L. D. (2018). Individual-level cultural consumer engagement styles: Conceptualization, propositions, and implications. International Marketing Review, 35(1), 42–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-11-2017-0267

Hollebeek, L. D., & Macky, K. (2019). Digital content marketing’s role in fostering consumer engagement, trust, and value: Framework, fundamental propositions, and implications. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 45, 27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2018.07.003

Hollebeek, L. D., Hammedi, W., & Sprott, D. E. (2023). Consumer engagement, stress, and conservation of resources theory: A review, conceptual development, and future research agenda. Psychology & Marketing, 40(5), 926–937. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21902

Hollebeek, L. D., Srivastava, R. K., & Chen, T. (2019). S-D logic–informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(1), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0494-5

Hollebeek, L., Glynn, M., & Brodie, R. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, J., Huang, M.-H., & Wyer, R. (2016). Slowing down in the good old days: The effect of nostalgia on consumer patience. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(3), 372–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw030

Hussain, A., Hollebeek, L., Marder, B., & Ting, D. (2025). In-game content purchase motivations (IGCPMs): Conceptualization, scale development, and validation. Information & Management, 62(7), 104207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2025.104207

Katz, E., Blumler, J., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/268109

Keller, K. L., & Staelin, R. (1987). Effects of quality and quantity of information on decision effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1086/209106

Khan, I., Hollebeek, L., Fatma, M., Islam, J., Rather, R., Shahid, S., & Sigurdsson, V. (2023). Customer engagement and experience through mobile app- vs. desktop browser-based platforms. Journal of Marketing Management, 39(3–4), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2022.2106290

Kim, J., & Johnson, K. (2016). Power of consumers using social media: Examining the influences of brand-related user-generated content on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.047

Klein, A., & Moosbrugger, H. (2000). Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika, 65(4), 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296338

Kumar, A., Shankar, A., Hollebeek, L., Behl, A., & Lim, W. (2025). Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) revolution: A deep dive into B2B firms’ genAI adoption. Journal of Business Research, 189(Feb), 115160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.115160

Kumar, V., Hollebeek, L., Sharma, A., Rajan, B., & Srivastava, R. (2025). Responsible stakeholder engagement marketing. Journal of Business Research, 189, 115143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.115143

Lee, R, & Robbins, S. (1995). Measuring belongingness: The Social Connectedness and the Social Assurance Scales. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(2), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232

Lee-Won, R., Lee, E., & Lee, J. (2023). Nostalgic social media use and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 26(2), 90. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2022.0281

Lei, C., Ubaldino, S., Lourenço, F., Wu, C., & Mak, C. (2023). Virtual music concert attendance motives and experience through the lens of uses and gratification theory. Event Management, 27(4), 607–624. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599522X16419948695134

Li, Y., Lu, C., Bogicevic, V., & Bujisic, M. (2019). The effect of nostalgia on hotel brand attachment. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 691–717. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2017-0797

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 1–55.

Loh, H., Gaur, S. S., & Sharma, P. (2021). Demystifying the link between emotional loneliness and brand loyalty: Mediating roles of nostalgia, materialism, and self-brand connections. Psychology & Marketing, 38(3), 537–552. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21452

Marchegiani, C., & Phau, I. (2011). The value of historical nostalgia for marketing management. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 29(2), 108–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501111117575

McQuail, D. (1983). Mass communication theory: An introduction. SAGE.

Met (2025). Decoding Gen “Y”. Met.edu. https://www.met.edu/knowledge_at_met/decoding_gen_y.

Montag, C., Sindermann, C., & Becker, B. (2022). Cognitive overload in the digital age: Implications for media and consumer behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107203.

Moriuchi, E., Hollebeek, L., & Lim, W. (2025). Consumers’ smartphone addiction: Impact of engagement and app type on wellbeing. Journal of Business Research, 194(May), 115379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2025.115379

Mousavi, S., Roper, S., & Keeling, K. (2017). Interpreting social identity in online brand communities: Considering posters and lurkers. Psychology & Marketing, 34(4), 376–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20995

Mukhopadhyay, M. (2024). Nostalgia marketing: A systematic literature review and future directions. Journal of Marketing Communications, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2024.2306551

Mustak, M., Halikainen, H., Plé, L., Hollebeek, L., & Aleem, M. (2024). Using machine learning to develop customer insights from user-generated content. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 81(Nov), 104034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.104034

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd d). McGraw-Hill.

Rather, R. & Hollebeek, L. (2021). Customers’ service-related engagement, experience, and behavioral intent: Moderating role of age. Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services, 60(May), 102453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102453

Rather, R., Hollebeek, L., Loureiro, S., Khan, I., & Hasan, R. (2024). Exploring tourists’ virtual reality-based brand engagement: A uses-and-gratifications perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 63(3), 606–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875231166598

Rathnayake, D. (2021). Gen Y consumers’ brand loyalty: A brand romance perspective. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 39(6), 761–776. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-09-2020-0421

Routledge, C., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Juhl, J. (2013). Nostalgia as a resource for psychological health and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(11), 808–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12070

Rubin, A. (2009). Uses-and-gratifications perspective on media effects. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 165–184). Routledge.

Ruggiero, T. E. (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Communication & Society, 3(1), 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0301_02

Russell, C., & Levy, S. (2012). The temporal and focal dynamics of volitional reconsumption: A phenomenological investigation of repeated hedonic experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(2), 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1086/662996

Santiago, J., Borges Tiago, M., & Tiago, F. (2025). Social media challenges: Fatigue, misinformation and user disengagement. Management Decision. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2024-0868

Santini, F., Lim, W., Ladeira, W., Costa Pinto, D., Herter, M., & Rasul, T. (2023). A meta-analysis on the psychological and behavioral consequences of nostalgia: The moderating roles of nostalgia activators, culture, and individual characteristics. Psychology & Marketing, 40(10), 1899–1912. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21872

Schivinski, B., Christodoulides, G., & Dabrowski, D. (2016). Measuring consumers’ engagement with brand-related social-media content: Development and validation of a scale that identifies levels of social-media engagement with brands. Journal of Advertising Research, 56(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2016-004

Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2019). The sociality of personal and collective nostalgia. European Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 123–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2019.1630098

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2008). Nostalgia: Past, present, and future. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5), 304–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00595.x

Seppala, E., Rossomando, T., & Doty, J. (2013). Social connection and compassion: Important predictors of health and well-being. Social Research, 80(2), 411–430. doi:10.1353/sor.2013.0027

Shao, G. (2009). Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Research, 19(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240910927795

Shao, W., Ross, M., & Grace, D. (2015). Developing a motivation-based segmentation typology of Facebook users. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(7), 1071–1086. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-05-2014-0089

Singh, S. (2010). The Indian way: Understanding the cultural differences that shape our lives. Penguin.

So, K., Li, J., King, C., & Hollebeek, L. (2024). Social media-based customer engagement and stickiness: A longitudinal investigation. Psychology & Marketing, 41(7), 1597–1613. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21999

Statista. (2025). Internet and social media users in the world 2025| . https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

Tanskanen, A., & Danielsbacka, M. (2012). Beneficiary-dependent effects of social support: An evolutionary perspective. European Journal of Ageing, 9(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0202-7

Thadikaran, G., & Singh, S. (2024). Fostering inclusion in digital marketplace: Vistas into the online shopping experiences of consumers with visual impairment in India. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 15(1), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.15388/omee.2024.15.5

Thomson, M., MacInnis, D., & Park, C. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1501_10

Tian, Y., Chan, T., Liew, T., Chen, M., & Liu, H. (2025). Overwhelmed online: Investigating perceived overload effects on social media cognitive fatigue via stressor–strain–outcome model. Library Hi Tech. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-03-2024-0145

Turner, J., Hogg, M., Oakes, P., Reicher, S., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell.

Viswanathan, V., Hollebeek, L.D., Malthouse, E., Maslowska, E., Kim, S., & Xie, W. (2017). The dynamics of consumer engagement with mobile technologies. Service Science, 9(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1287/serv.2016.0161

Waqas, M., Wajid, N., Khan, A., Hollebeek, L., & Urbonavicius, S. (2025). Enhancing brand equity through sublime experience: The mediating role of consumers’ branded content engagement. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/cb.70002

Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2006). Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 975–993. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.975

Wulf, T., Rieger, D., & Schmitt, J. B. (2018). Blissed by the past: Theorizing media-induced nostalgia as an audience response factor for entertainment and well-being. Poetics, 69, 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2018.04.004

Xiang, P., Chen, L., Xu, F., Du, S., Liu, M., Zhang, Y., Tu, J., & Yin, X. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nostalgic social media use. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1431184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1431184

Yadav, R., & Mahara, T. (2020). Exploring the role of E-servicescape dimensions on customer online shopping: A stimulus-organism-response paradigm. Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, 18(3), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.4018/JECO.2020070104

Yang, Y., Hu, J., & Nguyen, B. (2021). Awe, consumer conformity, and social connectedness. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 39(7), 893–908. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-01-2021-0017

Yii, H., Tan, D., & Hair, M. (2020). The reciprocal effects of loneliness and consumer ethnocentrism in online behavior. Australasian Marketing Journal, 28(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2019.08.004

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025848

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

Zillmann, D., & Bryant, J. (1985). Selective exposure to communication. Lawrence Erlbaum.