Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2022/3, vol. 107, pp. 90–119 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2022.107.3

The Structure of Wartime Strategic Communications: Case Study of the Telegram Channel Insider Ukraine*

Bohdan Yuskiv

AGH University of Science and Technology in Krakow (Poland),

Faculty of Humanities; Rivne State University of Humanities (Ukraine)

Email: yuskivb@ukr.net

Nataliia Karpchuk

Lesya Ukrainka Volyn National University,

Faculty of International Relations (Ukraine)

Email: Natalia.karpchuk@vnu.edu.ua

Oksana Pelekh

Rivne State University of Humanities,

Managament Department (Ukraine)

Email: peleho@ukr.net

Abstract. This article focuses on the issue of strategic communications of Ukraine during the Russian-Ukrainian war, which began on February 24, 2022. The authors consider strategic communications as a system consisting of invariant and variable components that can be projected in media reports. The authors proceed from the fact that, on the one hand, the media are an instrument of strategic communications, and on the other, strategic communications are transformed and reflected in media reports. The study is aimed at revealing the structure of strategic communications, which is a characteristic of the period of armed conflict. Reports of the Telegram channel Insider Ukraine during the first 100 days of the war were analyzed. On the basis of a reflexive thematic analysis, using a one-way dispersion analysis, it has been found that the strategic communications of Ukraine during the war period consist of the following invariant components: interactive communications of Ukraine, operational communications of Ukraine, extraoperational communications of Ukraine, operational and extraoperational communications concerning the RF. These generalized components have their own sub-components, the intensity or total absence of which in media reports can be related to specific events of the war period. This study contributes to the understanding of the structure of strategic communications in general and during the war in particular.

Keywords: strategic communications, reflexive thematic analysis, media reports, generalized components and subcomponents, events, war, Ukraine.

Strateginės komunikacijos struktūra karo metu: „Telegram“ kanalo Insider Ukraine atvejo studija

Santrauka. Šis straipsnis tiria Ukrainos strateginę komunikaciją 2022 m. vasario 24 d. pradėto Rusijos karo prieš Ukrainą metu. Autoriai strategine komunikacija laiko tam tikrą išliekančių ir kintančių komponentų sistemą, kuri atsispindi žiniasklaidoje. Autoriai atsispiria nuo prielaidos, kad, viena vertus, žiniasklaida yra strateginės komunikacijos įrankis ir, kita vertus, pati strateginė komunikacija yra keičiama reaguojant į esamas žinutes. Šio tyrimo tikslas yra atskleisti strateginę komunikaciją, kuri yra būdinga ginkluoto konflikto metu. Siekiant šio tikslo buvo analizuojamos žinutės, skelbtos „Telegram“ kanalo Insider Ukraine per pirmąsias šimtą karo dienų. Remiantis refleksyvia tematine analize bei vienakrypte dispersine analize buvo nustatyta, kad Ukrainos strateginė komunikacija karo metu susideda iš kelių nekintamų komponentų: interaktyvios, operacinės ir ekstraoperacinės Ukrainos komunikacijos ir operacinės bei ekstraoperacinės komunikacijos, liečiančios Rusijos Federaciją. Šie bendriausi komponentai skaidomi į smulkesnius subkomponentus, kurių intensyvumas ar atsisakymas žinutėse gali būti susijęs su atskirais karo meto įvykiais. Šis tyrimas prisideda prie geresnio strateginės komunikacijos supratimo karo metu.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: strateginė komunikacija, refleksinė teminė analizė, žiniasklaidos pranešimai, apibendrinti komponentai ir sudedamosios dalys, įvykiai, karas, Ukraina.

_________

Received: 19/07/2022. Accepted: 26/09/2022

Copyright © 2022 Bohdan Yuskiv, Nataliia Karpchuk, Oksana Pelekh. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The modern media space is a sphere where states look for and develop new forms and ways of promoting (and achieving) their foreign policy goals, forming a positive attitude towards the state and its political leadership, and ensuring national security. Systematic long-term communication on these issues denotes strategic communication that “encompasses all communication that is substantial for the survival and sustained success of an entity.”1 The main, “traditional” components of strategic communication include public diplomacy, international public relations, information and psychological operations,2 which, being different in form and applied means, should be subordinated to common goals and act in a coordinated manner.

It is obvious that public diplomacy and international PR will be more relevant in peacetime; and in the period of collision and conflict, informational war operations and psychological confrontation aimed at countering hybrid threats will have greater weight, when “<...> state and non-state actors use diverse means and tools to influence different forms of decision-making, undermine citizens’ trust in democratic processes and institutions, exacerbate political polarisation and spread confusion about geopolitical events with the ultimate goal of destabilising the victim while reinforcing the political vision and values of the offender.”3 The mentioned components of strategic communications are implemented using the media (to a greater or lesser extent), in particular social media.

For Ukraine, the importance and relevance of strategic communications have become especially noticeable since the beginning of the Russian aggression in 2014. Representatives of the Security Service of Ukraine claim that “<…> properly constructed strategic communications are one of the directions of struggle in the conditions of hybrid warfare. And only by consolidating the efforts of the entire expert environment – scientists, educators and practitioners from the civil and military sectors – we will be able to achieve a joint victory.”4

The stage of the Russian-Ukrainian war, which began on February 24, 2022, is associated with new challenges not only on the battlefield, but also in terms of information. It is an escalation of the confrontation that goes beyond the traditional Russian Federation propaganda and which is fully aggressive not only against Ukraine and the Ukrainian society but also against Western values. Experts emphasize that Ukraine is winning in the informational confrontation.5 This is especially important, because Ukraine is waging an asymmetric war against a nuclear state with a superior military potential.6

Since 2014, in the conditions of the first phase of the Russian-Ukrainian war and further, since February 24, 2022 (the second stage of the war), the Ukrainian media space has been and remains a space of active information and psychological battles, where the fight is conducted not only for emotions, but for consciousness, beliefs, assessments, and behaviors of the objects of influence. The authors of the article assume that, on the one hand, the media is an instrument of strategic communications, but on the other hand, strategic communications receive a new “life” in the media space, and these transformations of strategic communications are presented in media themes.

The aim of this research is to reveal the structure of strategic communications, which is a characteristic of the armed conflict period. The system of strategic communications is the object of the study. The subject of the study is represented by the structure of Ukraine’s strategic communications during the war.

We assume that in the conditions of the Russian-Ukrainian war of 2022, the structure of strategic communications may depend on the period of the war, the events in and around Ukraine, and sanctions imposed on the Russian Federation. However, during the first 100 days of the war, it is difficult to speak about a clear periodization of structural changes; the influence of sanctions reaches its effect in the long term. Therefore, we intend to compare the interdependence of strategic communication components and events (presented in media reports) that have taken place in and around Ukraine during the first 100 days of the 2022 Russian-Ukrainian war, i.e. to distinguish the invariant and variable components of strategic communications.

Obviously, in wartime certain structural components of strategic communications will prevail, while others may be absent altogether. In essence, this is one of the instrumental tasks in the field of strategic communications, the implementation of which determines the potential of the effective activity of the security and defense sector in order to ensure national interests in the conditions of the war against the Russian Federation.

The initial stage of the analysis involved a verification of two hypotheses related to the components: 1) whether all components are significant; 2) whether all components contribute equally to the overall system of strategic communications.

This paper has the following structure: the introduction outlines the importance and purpose of the research; the first section describes the research methodology; the second considers Ukraine’s system of strategic communications; the final sections present the findings of the analysis and the paper’s general conclusions.

1. Research Methodology

Since media belong in the toolkit of strategic communications, these communications can be detected to a large extent through the usual study of media reports flows. Today, both traditional (print, visual, and audio) media and internet media, as well as social networks, are used to implement strategic communications. For the last year in Ukraine, a significant place among the latter has been occupied by Telegram channels, the popularity of which has increased fivefold between the beginning of the war and the end of April.7 We can single out two defining features of Telegram channels that distinguish them from traditional chroniclers of current events: 1) Telegram channels provide operational information (essentially provided in real time, i.e., the delay between the event and information about it can be as short as a few minutes) and a simplified access to the information (one only requires access to the internet and a mobile phone); 2) these channels make it possible to significantly reduce the time of searching for the necessary information and access textual, audio, video, or photo materials by following the corresponding reference.

As it is practically impossible to cover the entire media space, we chose one of the top Ukrainian political news Telegram channels – Insider Ukraine (https://t.me/joinchat/AAAAAFCg99bpFf62A_f3yA); its reports have served as the empirical material of this study. In Ukraine, as of July 1, 2022, the channel’s audience of subscribers was 1.41 million people. The channel is ranked 4th in the Top-100 Telegram channels in Ukraine (the rating is composed by Detector Media – a public organization established by Ukrainian journalists in 2004 – on the basis of TGState and Telemetrio data)8; Insider Ukraine is ranked 6th based on its reach, 5th based on citations (out of 100 Telegram channels in Ukraine), and is preceded only by the Telegram channels of the President of Ukraine V. Zelensky, the President’s Office, and the Security Service of Ukraine.9 It is not a governmental channel; it specializes in investigative political journalism. Insider Ukraine’s materials are frequently reposted and referred to even by channels with larger numbers of subscribers.

The general research methodology used in this paper consists of the following stages: reading reports from the Telegram channel and forming a sample; coding and thematic analysis of the data; analysis of the dynamics of changes in the structure of strategic communications.

Regarding the sample, we studied the reports of Insider Ukraine during the 100-day period of the second stage of the Russian-Ukrainian war (from February 24 to June 3, 2022). The total number of reports was 125,040 messages; after excluding messages that contained only video or photo materials without any comments, 9994 units were left. Since the research methodology involved a lot of manual data coding, a serial sample had to be formed. The entire study period was divided into 15 weeks, one day was randomly selected from each week, and its reports were subjected to total analysis. As a result of such screening, the sample included 1,387 messages, or 92 messages per day. The data were exported as Excel spreadsheets for further coding, synthesis, and calculation of relevant statistical characteristics.

To answer the research problem, the authors chose one of the methods of qualitative analysis, namely thematic analysis, aimed to “identify themes, i.e. patterns in the data that are important or interesting.”10 G. W. Ryan and H. R. Bernard define thematic coding as a process that occurs within “mainstream” analytic traditions (such as grounded theory) rather than as a specific approach.11

The applied analysis can be attributed to a type of thematic analysis, which is called reflexive thematic analysis (RTA).12 RTA is the most flexible among other types of thematic analysis and combines the possibilities of inductive and deductive approaches. An inductive approach involves making sense and creating themes from the data without any preconceived notions, i.e. no idea of what themes will emerge, and thus it allows the themes to be determined by (emerge from) the data. In contrast to the inductive approach, the deductive approach involves starting the analysis from a set of expected themes that can be found in the data. Reflexive thematic analysis does not use a detailed set of code descriptions; researchers can modify, delete, and add codes as they work with the data. Forming our own coding scheme (template) at the deductive stage of the research, we started from the blocks of strategic communications introduced by V. Lipkan13 (they will be considered further in the article).

Thus, thematic analysis served to categorize the studied data set by coding fragments of texts to identify and summarize important concepts in the data set. At the same time, it enabled to identify important structural elements of strategic communications present in media reports of the studied period. The latter was possible because the authors relied more on an inductive approach to see how themes emerge during the research. In other words, we observed how strategic communications are projected in the media.

In the process of analyzing the structure and structural changes, an index approach and the data visualization method were used. Calculations were performed in the R programming language using packages dplyr, tidyr, tidyquant, tidyverse, ggplot2, ggdalt, stats, matrixStats, and others (the present paper belongs to the authors’ series of studies carried out by applying thematic analysis14).

2. The System of Strategic Communications of Ukraine

In the context of growing geopolitical tensions and public concern about terrorism, strategic communications have been viewed as an essential component of an effective response to campaigns by hostile state and non-state actors seeking to shape public opinion and attitudes in pursuit of their own strategic objectives. The explorations on how identities, social roles, myths, narratives, ideas, norms, and discourses shape the political space gradually led to debates around their instrumentalization through the communications strategies of different international actors.15 The variety of contexts, as well as the variety of actors, lead to the development of various definitions of “strategic communications.” In particular, we consider the following interpretations useful for our research:

• “The state’s projection of certain vital and long-term values, interests, and goals into the conscience of domestic and foreign audiences <…> by means of adequate synchronization of multifaceted activities in all domains of social life <…>. In the realm of foreign policy, they combine the synchronization of affecting an allied state and non-state actors through friendly “deeds, words and images” and through a wide range of communications within the framework of information warfare (addressing foes and enemies)”.16

• a systematic series of sustained and coherent activities conducted across strategic, operational, and tactical levels that enable an understanding of target audiences and identify effective conduits to promote and sustain particular types of behavior.17

• “the alignment of multiple lines of operation (e.g., policy implementation, public affairs, force movement, information operations, etc.) that together generate effects to support national objectives; <…> sharing meaning (i.e., communicating) in support of national objectives (i.e., strategically). This involves listening as much as transmitting, and applies not only to information, but also to physical communication – action that conveys meaning”.18

On the basis of the above definitions, it is possible to distinguish the essential characteristics of strategic communications, in particular: 1) they are executed according to a predetermined and systematic plan, not only as a reaction to current events; 2) they involve actions at strategic, operational, and tactical levels; 3) they are developed in a competitive, and even conflictive, environment, where audiences are subject to a constant buzz that can hamper meeting t audience’s goals; 4) they demand a high level of coordination and synchronization between stakeholders; 5) they require a specific definition of the targeted audiences; 6) they require a selection of the most adequate communication channels; 7) they aim to inform, influence, or promote behavioral changes in target audiences; 8) they must be aligned with the overall goals of the promoter country or organization; 9) they must focus on both the short and long terms.19

James G. Stavridis emphasizes that the effectiveness of strategic communications depends on careful planning: “the objective of strategic communication is to provide audiences with truthful and timely information that will influence them to support the objectives of the communicator. In addition to truthfulness and timeliness, the information must be delivered to the right audience in a precise way.”20 Cristian E. Guerrero-Castro believes that the difference between strategic communications and, for example, social communications is that only strategic communications (based on strategy) pursue vital goals for the state, “strategy focuses attention on how to articulate the tools for achieving goals related to dealing with threats that lead to conflicts, and furthermore, it recognizes that the means employed must be coordinated at the highest level of the nation-state and must also understand the broad spectrum of all the resources that constitute national power.”21

The researcher claims that the missions of strategic communications (specifically in terms of security and defense) include maintaining, protecting, and achieving the national interests and objectives of the nation-state, which are divided across different temporal periods: “1) in times of peace: to achieve deterrence in the hemisphere and strategic stature in the international system, 2) in a state of crisis: to obtain credibility in the international system, 3) in a state of war: to achieve internal and external legitimacy in the international system in order to obtain freedom of action.”22

The Doctrine of Information Security of Ukraine interprets the term “strategic communications” as the coordinated and proper use of the state’s communication capabilities – public diplomacy, public relations, military relations, information and psychological operations, measures aimed at promoting the state’s goals.23 Consequently, strategic communications are social relations that are formed in the process of interaction and coordination of the activities of the system of state authorities, the Armed Forces of Ukraine, other military formations (established in accordance with the laws of Ukraine), law enforcement and intelligence agencies, state bodies of special purpose with law enforcement functions, civil defense forces, the defense-industrial complex of Ukraine, the activities of which are under democratic civilian control, in accordance with the Constitution and laws of Ukraine in the field of protection of Ukraine’s national interests from threats; as well as citizens and public associations who voluntarily participate in ensuring the national security of Ukraine, taking into account the experience of the NATO member states.24 Hence, we can conclude that strategic communications represent a process that is at the basis of ensuring the national security of Ukraine, and its implementation involves the subjects of strategic communications as well as subjects from other spheres of activity.

Therefore, V. Lipkan attributes to the tasks of the national system of strategic communications of Ukraine the following: expansion of the capabilities of the security and defense sector in the field of strategic communications at the strategic and operational levels, as well as the development of the culture of strategic communications of the state authorities of Ukraine; establishment of interdepartmental cooperation in the field of strategic communications through the introduction of modern and effective communication mechanisms and processes; creation of opportunities for strategic communication training of representatives of the security and defense sector and the Ukrainian authorities in general on the basis of multilateral and bilateral formats. From an instrumental point of view, the researcher defines such blocks of strategic communications25 as:

1) interactive: public diplomacy; involvement of a key leader; relations with mass media, with state authorities, with the public; internal communication;

2) information and psychological: information, psychological, and special operations;

3) technical: cyber security, countermeasures in the electromagnetic space;

4) military: block of military and civil-military cooperation; documentation of events, security of operations, measures of active influence.

Despite the institutionalization of strategic communications in Ukraine, in particular the functioning of the Center for Strategic Communications and Information Security under the Ministry of Culture and Information Policy, there is no document that unambiguously outlines the purpose of strategic communications in Ukraine.

Having considered the Doctrine of Strategic Communications of the Armed Forces of Ukraine,26 we believe that the main missions of Ukraine’s strategic communications are the following: to build domestic and foreign public trust in state policy, to support reforms and the course of Ukraine’s acquisition of membership in the EU and NATO; to coordinate the actions of state bodies and other participants of strategic communications while objectively informing the society on issues related to the development of the state. However, during the war, strategic communications pursue somewhat “additional” goals: to unite the Ukrainian people for an (evidently prolonged) struggle not only for freedom, but for the survival of the nation; to gather support for this struggle from the international community. It is obvious that all media-representation of the strategic communications components should be subordinated to such a goal.

Naturally, strategic communications are oriented toward a long-term perspective, but at the tactical and operational levels, they are closely related to events that develop rapidly and are not always predictable.

In the process of functioning of any system, orderly and stable structures arise in it. In the general sense, the structure of a system can be defined as a set of permanent and significant connections among the elements of the system from the point of view of the goals of its functioning. It is in the structure that the system reproduces itself, and continues to exist for a certain time in a relatively unchanged form, and it is through the structure that its functions, which the system performs in an external environment, are determined. From an internal, systemic point of view, the structure determines the relations among the components of the system. In the system of strategic communications of the state, the structure of strategic communications can be defined as a system of established proportions and interdependencies that have developed among types of communications in the process of system functioning. Therefore, in a simplified version, to determine the structure of a system means (1) to identify its components and (2) to determine the proportions between them. If the first is considered to a greater extent as an invariant part of the structure, then the second can be attributed to its variable part.

3. Research Findings

On the basis of a thematic analysis of the empirical material (reports), in the process of coding, a system of analysis categories was gradually developed, which, in our opinion, reflects the structural components. These components are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Strategic communications structural components revealed in the media space of Ukraine

|

Generalized components |

Subcomponents |

|

Interactive communications (Ukraine) |

• public diplomacy • involvement of a key leader • media relations • relations with state authorities • PR • domestic communication • international support |

|

Operational communications (refer to Ukraine) |

• information operations (cyberspace) • psychological operations (human dimension) • special operations (military actions) |

|

Operational communications (refer to the RF) |

• information operations (cyberspace) • psychological operations (human dimension) • special operations (military actions) |

|

Extraoperational communications (refer to Ukraine) |

• military cooperation and military-civilian cooperation • consequences of military operations (human, military, material) • consequences of military operations (economic, technological, prospective) • security of operations • negotiation processes |

|

Extraoperational communications (refer to the RF) |

• military cooperation and military-civilian cooperation • consequences of military operations (human, military, material) • consequences of military operations (economic, technological, prospective) • security of operations • negotiation processes |

The variability of the structure is quite well observed when comparing it with the events. A reflexive thematic analysis of media reports from the Telegram channel Insider Ukraine made it possible to identify statistical indicators of each of the components of strategic communications and their criteria (Annex A). A comparison with the events in and around Ukraine enables to conclude the following:

1. The interactive communications of Ukraine were the most powerful at the beginning of the war; in particular, the largest number of reports fell on the subject of international support (14.1%), relations with state authorities (9.1%), and the involvement of a key leader (4.5%). We claim that the following events influenced this distribution:

• Starting from February 25, 2022 President V. Zelensky addressed the peoples and Parliaments of the countries of the world (Israel, Great Britain, Poland, the USA, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Japan, France, Sweden, the Netherlands, etc.), as well as the intellectual communities of the USA and France, with a call to condemn the Russian Federation and to provide support, especially military, to Ukraine; there were days when he spoke three times before the global community. At the beginning of April, such a powerful information presence in the public space of the states decreased precisely because of the adequate reaction of the global community. At the end of May, the presence increased again due to active calls by V. Zelensky to grant Ukraine the status of an EU candidate-state.

• Since February 26, US and UK officials have acknowledged that Russia has faced tougher-than-expected resistance in Ukraine. The UN General Assembly, as well as the world’s politicians and intellectual elite, express their support for Ukraine; the EU announces a new package of sanctions, and international support for Ukraine continues to grow: the help of Anonymous hackers, humanitarian aid, new sanctions against the RF, and aid with weapons (the largest number of reports fall on the first four weeks of the war, when Ukraine sought international support in the fight against a powerful enemy). In mid-May (the 12th week), there is a rapid growth of the international support topic as president of the United States J. Biden signs a lend-lease agreement for Ukraine, and Sweden and Finland announce their desire to join the NATO, which once again vividly demonstrates Putin’s false ideas about a “special operation in Ukraine” to “prevent the expansion of NATO to the borders of the Russian Federation.”

• Regarding “relations with state authorities,” the intensity of reports in the first 4–6 weeks of the war is caused by the fact that the heads of regional military administrations begin to inform on events in the conflict zones and temporarily occupied territories and to provide information about evacuation or humanitarian aid; the second half of May is characterized by further restoration of business activity in the non-occupied territory of Ukraine for restoring the state’s economy, active cleaning operations, and the reconstruction of liberated cities and towns.

2. In terms of operational communications (concerning Ukraine), psychological operations dominate the sample (18.7%). Their intensity during the second week and at the end of March is connected with the need 1) to reassure citizens and reduce the level of panic; 2) to convince citizens of the strength and reliability of the Armed Forces, Territorial Defense, National Guard, and State Emergency Service; 3) to mobilize citizens to fight, if necessary – for a prolonged period; 4) to prevent the formation of thoughts about capitulation. The events that affected the subject of operational communications in Ukraine are the following:

• The information operations in the cyberspace are a top topic during the first week of the war: all Ukrainians are called to join the “cyber army” to convey the truth about the war to the Russian population and to attack the enemy’s information infrastructure.

• The theme of psychological operations dominates during the second week – forming citizens’ mental resistance in the face of the casualties of war, during the sixth week – the liberation of Bucha and Irpen towns and testimony about the atrocities committed by the Russian army; the eighth week – restoration of the state border in Kyiv, Chernihiv and Sumy regions; May – calls to save the defenders of “Azovstal” and their subsequent evacuation to the territory of the DPR.

• The topic of military operations is actively spread during the first week; at the end of March it refers to the gradual liberation of Irpin, Bucha, Hostomel; the subsequent decrease is probably related to the general call to “keep quiet” and not to discuss the current actions of the Ukrainian military (this is also regulated by a number of new orders27 and even criminal liability28).

3. Operational communications (relating to the RF): special operations (military operations) dominate the sample (6.0%), especially during the first three weeks – the period of the RF’s rapid offensive, the capture of populated areas, large-scale air and missile strikes on the military and civilian infrastructure of Ukraine; and during the fifth week – attacks on fuel storage facilities to make it difficult for Ukrainians to provide logistical support and to create a humanitarian crisis. Special operations are accompanied by psychological operations (6.1%, most of them within 3–5 weeks, aimed at intimidating civilians) – preventing evacuation from the occupied territories, an airstrike on a hospital and a drama theater in Mariupol, firing on civilians queueing for bread in Chernihiv, the dispersal of peaceful protests in the occupied cities (Kherson, Kakhovka, Berdyansk, Energodar) etc.;

4. Extraoperational communications (concerning Ukraine): 11.5% are devoted to the consequences of military operations (human, military, material), and 6.9% (second place) – military and military-civilian cooperation. The events reflected in these communications are the following:

• During the second to fourth weeks, Ukrainians and the world are shocked by the RF Army’s shootings of civilians and the destruction of Ukraine’s architectural and cultural heritage; the media pay a lot of attention to the village of Chornobayivka in the Kherson region, where the Armed Forces of Ukraine (as of February 19, 2022) defeat groups of the RF Armed Forces nine times in a row (the occupiers need the village as a platform for the offensive on Mykolaiv); the top topic of the seventh week is the liberation of Kyiv, Zhytomyr, Chernihiv and Sumy Regions, the beginning of infrastructure restoration, and the restructuring of logistics chains to launch the economy of these regions;

• President V. Zelensky awards military personnel for their courage and effective actions in repelling enemy attacks; on March 6, by the Decree of the President of Ukraine V. Zelensky No. 111/2022, cities that have offered the most steadfast resistance to the Russian invaders are awarded the status of hero cities: Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Mariupol, Kherson, Hostomel, Volnovakha;

• The negotiation process appears to be relevant only during the first week, when Ukraine’s political elite understand the need for a peaceful settlement in the conflict, but the incompatibility of the parties’ positions, as well as the RF’s overestimation of its negotiating positions, make the idea of negotiations hopeless; therefore, the topic disappears.

5. Extraoperational communications (regarding the RF): the consequences of military operations (human, military, material) (7.4%) and military and military-civilian cooperation (2.7%) dominate. We believe that this is connected to the following events:

• During the second to fourth weeks, emphasis is made on the daily number of neutralized Russian soldiers and destroyed equipment, including the number of prisoners and deserters (significantly raising the Ukrainian fighting spirit); the arrival of the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Karim Khan, to Ukraine to investigate war crimes committed by Russia, and the subsequent joining of other countries in the investigation.

• Using the territory of Belarus for missile attacks to target the northern regions of Ukraine, further involving Belarus in the war (since the first day of the war).

• The seventh to tenth weeks – the Armed Forces of Ukraine destroy the missile cruiser “Moskva”; the Russian media report on the shelling of objects of infrastructure in the Bryansk and Belgorod regions in Russia by the Ukraine’s Armed Forces; the media reports recognize that the economic situation of Russian citizens is deteriorating.

Based on the coding of each report for each day (according to the code system), the proportions between the components and subcomponents of the structure are determined (the share of each as the ratio of the number of reports related to a specific component to the total number of reports). The results of the calculations are given in Appendix A.

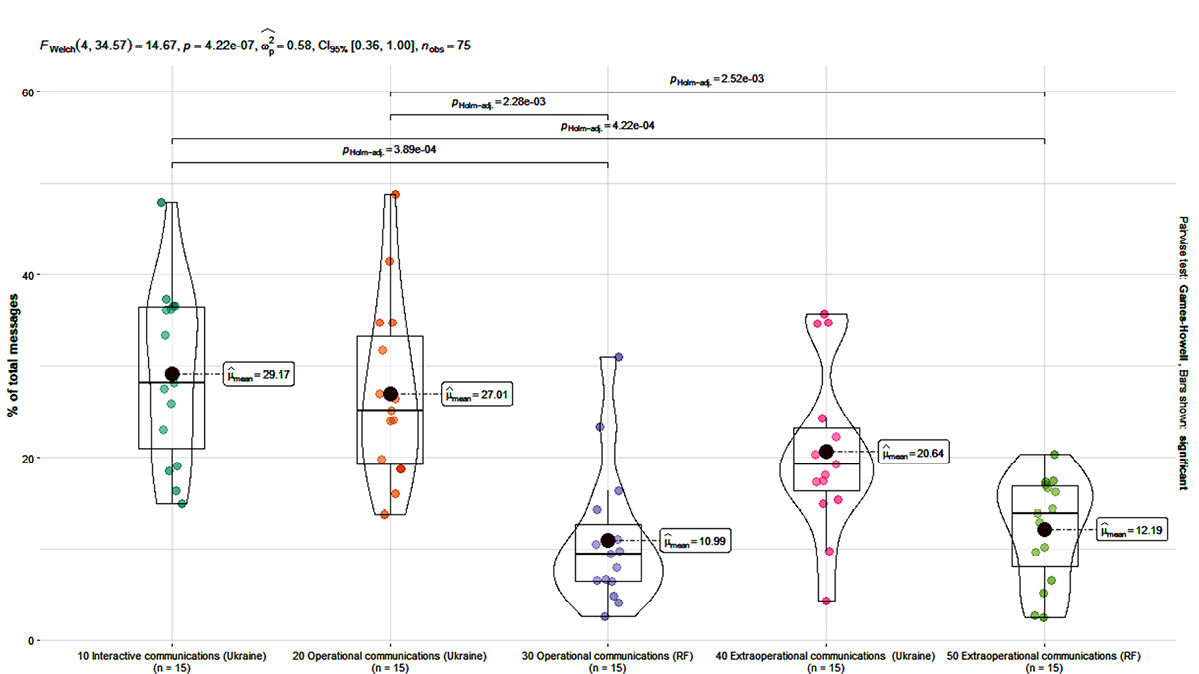

Visualization and the results of hypothesis verification are presented in Fig. 1. They refer to each component of the structure and their comparisons. Each plot consists of a violin plot (which shows the shape of the distribution of the variables) and a box plot (where the rectangle is divided by the median and bounded by the first and third quartiles of the distribution), as well as jittered raw datapoints. The large dot indicates the mean values of μ̂. Only significant pairwise comparisons are shown with accompanying p-values.

Fig. 1. Visualization and verification of hypotheses about the equality of the average shares of the strategic communications structure components

A One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)29 was used to examine questions of differrences among all data groups (a component). The analysis revealed a highly significant main effect, FWelch(4, 34.57) = 14.67, p < 0,001 (= 4.22e-07); it indicates that not all components had the same average score in the structure. The estimated ω2 (= 0.58) indicated that approximately 58% of the total variation in average score was attributed to differences among the five components of the structure.

As we can see, the null hypothesis was were not confirmed, that is, each component of the structure is significant, although the contribution of each is different. Fig. 1 helps conclude that the most significant are the components that concern Ukraine. First of all, these are the interactive communications of Ukraine (the average value for the entire period is 28.3%), including public relations, public diplomacy, and other components of strategic communications. This is followed by operational communications related to the conduct of war (23.5%) and extraoperational communications related to the consequences of war (22.3%). The share of strategic communications concerning the RF is half as much as the previous ones. It is interesting that extraoperational communications (13.1%) are higher than operational communications (12.8%).

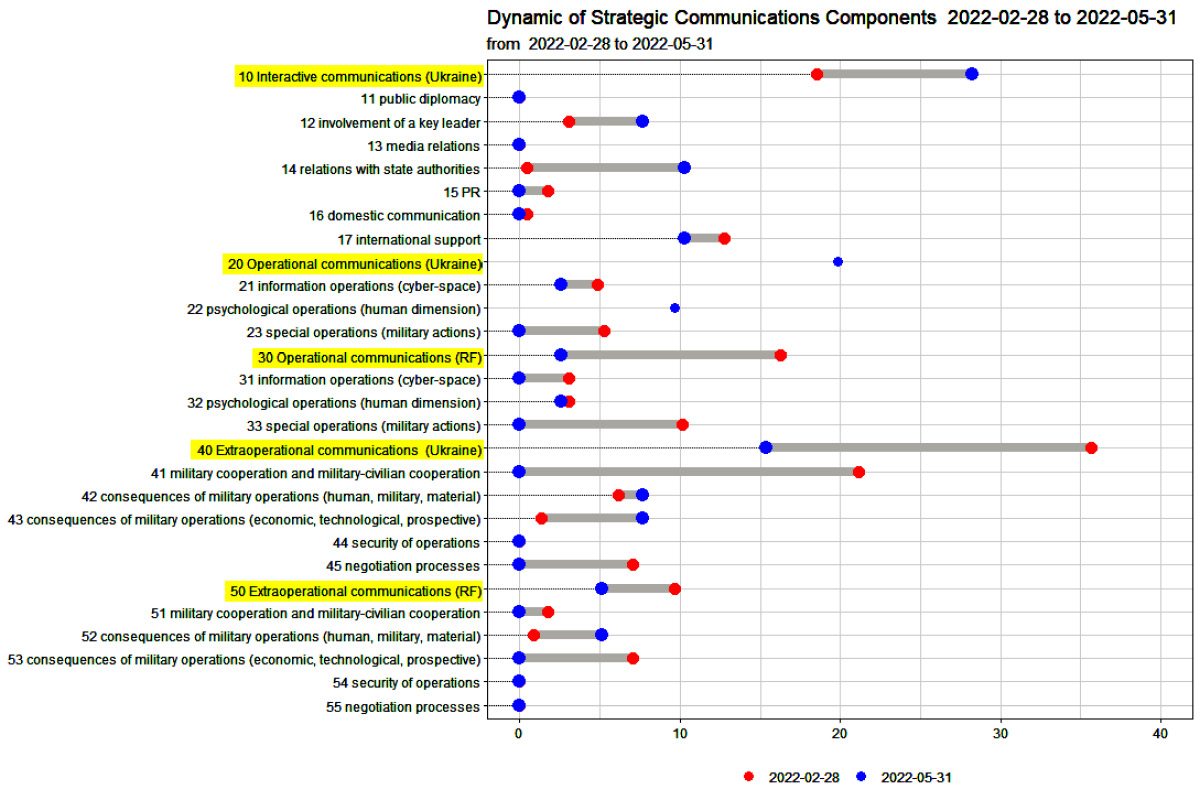

The analysis of the dynamics of strategic communication components (Figs. 2, 3, and Appendix A) enables us to conclude the following:

1) Completeness of communications: the reports refer to all generalizing categories of the model – interactive, operational, and extraoperational. They are fully represented in the reports, i.e., their specific weight varies from 12.8% to 28.3%. This refers to both sides of the conflict. The largest specific weight in different sub-periods falls on interactive communications of Ukraine (28.3%), operational communications of Ukraine (23.5%), and extraoperational communications of Ukraine (22.3%).

2) Dynamics of generalized communications (Fig. 3): at the beginning of the studied period, the greatest attention was paid to extraoperational communications of Ukraine, in the middle of the period – to interactive and operational communications of Ukraine, at the end of the period – to operational and extraoperational communications of Ukraine. Such emphases are quite logical: Ukraine first needed to establish a proper defense system and organize interaction within the society. Consequently, the Ukrainian society was concerned about the actions of the RF within their special operations and psychological operations. It was also necessary for receiving support and proper aid from Western countries. At the end of the research period, Ukraine concentrated most on countering the RF’s operational efforts.

3) emphases in communications (subcomponents): communications can be divided into 4 groups based on the specific weight of their appearance in reports:

• with the greatest attention (specific weight is over 12%) – psychological operations (human dimension) of Ukraine, international support for Ukraine;

• with significant attention (from 10% to 12%) – the consequences of military operations (human, military, material) for Ukraine;

• attention is paid (from 6% to 10%) – relations with state authorities in Ukraine, the RF’s psychological operations, the RF’s special operations, military and military-civilian cooperation of Ukraine, consequences of military operations (human, military, material) which concern the RF;

• attention is mostly not paid – the security of operations for Ukraine and the RF, their relations with the mass media, public diplomacy, etc.

Fig. 2. Change in the percentage ratio between the strategic communications components at the beginning (February 28, 2022) and at the end of the studied period (May 31, 2022)

Fig. 3. Dynamics of generalizing components during the entire period (from February 28 to May 31, 2022)

Conclusions

Strategic communications are coordinated, short- and long-term communication efforts to disseminate information, ideas, values, actions, etc. to a mass target audience in order to achieve a predetermined goal (to explain and promote national interests; to form and maintain a positive image of the government, state, and army; to counteract destructive information and psychological influences, etc.). Strategic communications use media as a means to influence audiences. However, in the media space, in particular under the conditions of war, strategic communications are transformed namely in way that some of their components will be more pronounced, while some even less or may be absent at all.

The thematic analysis of media reports of the Telegram channel Insider Ukraine demonstrate that all the discussed components of strategic communications, as related to Ukraine, are presented in the media space of Ukraine. It should be mentioned that since February 24, 2022, Telegram has turned into a key platform for Ukrainians to obtain information about the war (yet it was popular before the war as well). Its attraction and specificity are associated with the provision of operational information and a simplified access to events. Besides that, the reputation of Telegram channels in Ukraine is one of providing firsthand and truthful information.

Due to the analysis of empirical data, we revealed the structure of strategic communications in wartime. The structure includes communication components that refer to Ukraine – interactive, operational, and extraoperational communications – and those that refer to the RF (the enemy) – operational and extraoperational communications. All the listed components are substantial, but differ in weight. The share of components concerning Ukraine is more than twice as large as the share of the RF components. The highest share falls on interactive communications, which are a combination of communications related to public relations, public diplomacy, etc. These communications occupy the first position: primarily, topics concerned with seeking international support and the relations with state authorities, which is characteristic of the development of democratic countries in the period of globalization. The second position belongs to operational communications, in particular psychological operations; the third position – to extraoperational communications, specifically to consequences of military operations (human, military, material). Regarding the RF, operational (consequences of military operations (human, military, material)) and extraoperational communications (special operations) dominate the sample.

We can speak both about the invariance (constancy) and variability of these structural components. Invariance, in our opinion, is related to the immutability and consistency of the components of the structure when the conditions change (the situation in the country, the course of hostilities, international events, etc.). Variability is dependent on the situation: on the one hand, not all topics are always given increased attention, and secondly, not all topics are covered in the media.

The authors assume that the defined components and subcomponents of strategic communications during wartime may be applied to any situation of an armed conflict, and the verification of such an assumption may be the subject of further research.

References

Bozhuk, Ludmyla. “Sutnist' yavyshcha «stratehichni komunikatsiyi». PR yak riznovyd stratehichnoho menedzhmentu” [The essence of the “strategic communication” phenomenon. PR as a type of strategic management]. Repository of the National Aviation University (2022). https://er.nau.edu.ua/handle/NAU/53949.

Butler, Michael. “Ukraine’s information war is winning hearts and minds in the West.” The Conversation, May 12 (2022). https://theconversation.com/ukraines-information-war-is-winning-hearts-and-minds-in-the-west-181892.

Cornish, Paul, Julian Lindley-French, and Claire Yorke. Strategic communications and national strategy. Chatham House Report, September (2011). https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/r0911stratcomms.pdf.

Crosley, Jenna. “What (Exactly) Is Thematic Analysis? A Plain-Language Explanation & Definition (With Examples).” GradCoach, April (2021). https://gradcoach.com/what-is-thematic-analysis/.

Feiner, Lauren. “Ukraine is Winning the Information War against Russia.” CNBC, March 1 (2022). https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/01/ukraine-is-winning-the-information-war-against-russia.html.

García, Juan Pablo Villar, Carlota Tarín Quirós, and Julio Blázquez Soria. “Strategic communications as a key factor in countering hybrid threats.” European Parliamentary Research Service (Brussels, March 2021). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/656323/EPRS_STU(2021)656323_EN.pdf.

Guerrero-Castro, Cristian E. “Strategic Communication for Security & National Defense: Proposal for an Interdisciplinary Approach.” The Quarterly Journal 12, no. 2 (2013): 27–51. http://connections-qj.org/article/strategic-communication-security-national-defense-proposal-interdisciplinary-approach.

Izvoshchikova, Anastasiya. “Rada vvela kryminal'nu vidpovidal'nist' za foto- ta videozyomku peremishchen' ZSU” [The Council introduced criminal liability for photo and video shooting of the Armed Forces]. Suspilne. News, March 25 (2022). https://suspilne.media/221239-rada-vvela-kriminalnu-vidpovidalnist-za-foto-ta-videozjomku-peremisen-zsu/.

Korsunskiy, Serhiy. “Informatsiyna skladova viyny: yak Rosiya namahayet'sya poslabyty pidtrymku Zakhodu” [The information component of war: how Russia is trying to weaken support of the West]. Radio Svoboda, April 20 (2022). https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/informatsiyna-viyna-rosiyskyy-vplyv/31811302.html.

Lipkan, Volodymyr. “Ponyattya ta struktura stratehichnykh komunikatsiy na suchasnomu etapi derzhavotvorennya” [Concept and structure of strategic communications at the modern stage of state formation]. Global Organisation of Allied Leadership (2016). https://goal-int.org/ponyattya-ta-struktura-strategichnix-komunikacij-na-suchasnomu-etapi-derzhavotvorennya/.

Liskovych, Myroslav. “Informatsiyno-psykholohichna viyna: Ukrayina yiyi tochno ne prhraye” [Information and psychological warfare: Ukraine definitely does not lose it]. Ukrinform, May 28 (2022). https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-ato/3494447-informacijnopsihologicna-vijna-ukraina-ii-tocno-ne-prograe.html.

Mackenzie, Ruairi J. “ANOVA.” Technology Networks. Informatics (2022). https://www.technologynetworks.com/informatics/articles/one-way-vs-two-way-anova-definition-differences-assumptions-and-hypotheses-306553.

Maguire, Moira and Brid Delahunt. “Doing a Thematic Analysis: A Practical, Step-by-Step Guide for Learning and Teaching Scholars.” AISHE-J 9, no. 3 (2017): 3351–33514. https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335.

Michelsen, Nicholas and Mervyn Lowne Frost. “Strategic Communications in International Relations: Practical Traps and Ethical Puzzles.” Defence Strategic Communications 2 (2017): 9–33. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/strategic-communications-in-international-relations(36b55dee-049f-4d89-b3c7-46297d1f9def).html.

“Nakaz Holovnokomanduvacha Zbroynykh Syl Ukrayiny No.73 vid 03.03.22 Pro orhanizatsiyu vzayemodiyi mizh Zbroynymy Sylamy Ukrayiny, inshymy skladovymy syl oborony ta predstavnykamy zasobiv masovoyi informatsiyi na chas diyi pravovoho” [Order of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine No.73 of 03.03.22 On the organization of interaction between the Armed Forces of Ukraine, other components of the Defense Forces and representatives of the media during the legal regime of martial law]. Ministry of Defence of Ukraine (2022). https://www.mil.gov.ua/content/mou_orders/nakaz_73_050322.pdf.

Pro rishennya Rady natsional'noyi bezpeky i oborony Ukrayiny vid 29 hrudnya 2016 roku «Pro Doktrynu informatsiynoyi bezpeky Ukrayiny»: Ukaz Prezydenta Ukrayiny vid 25 lyutoho 2017 r. №47/2017 [On the decision of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine as of December 29, 2016 “On the Information Security Doctrine of Ukraine”: Decree of the President of Ukraine as of February 25, 2017 No. 47/2017]. https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/472017-21374.

Rating of Telegram Cnannels, TGState, 2022. https://uk.tgstat.com/en/ratings/channels?sort=members.

Riaboshtan, I., O. Pivtorak, and K. Iliuk. “From “Trukha” to Gordon: The Most Popular Channels of the Ukrainian Telegram.” Detector Media, September 20 (2022). https://detector.media/monitorynh-internetu/article/202968/2022-09-20-from-trukha-to-gordon-the-most-popular-channels-of-the-ukrainian-telegram/.

Ryan, Gery W. and H. Russell Bernard. “Data Management and Analysis Methods”. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed., 769–802. Sage Publications, 2000. http://qualquant.org/wp-content/uploads/text/2000%20Ryan_Bernard.denzin.pdf.

Stavridis, James G. “Strategic Communication and National Security.” JFQ 46, 3d quarter (2007). https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA575204.

Strategic Communication in EU-Russia Relations: Tensions, Challenges and Opportunities, ed. Evgeny Pashentsev, 19–20. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.https://www.academia.edu/40959010/Strategic_Communication_in_EU_Russia_Relations_Strategic_Communication_in_EU_Russia_Relations_Tensions_Challenges_and_Opportunities_Ed_Evgeny_Pashentsev_Cham_Palgrave_Macmillan_2020.

Tatham, Steve. “Strategic Communications: A Primer.” ARAG Special Series 8/28, 7. Shrivenham: Defence Academy of the UK, 2008. https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/94411/2008_Dec.pdf.

“Telegram reytynh. Top korysnykh ukrayins'kykh telehramm-kanaliv novyn ta dlya biznesu” [Telegram rating. Top useful Ukrainian Telegram channels for news and business]. Marketer, July 2 (2022). https://marketer.ua/ua/telegram-rating-top-useful-ukrainian-telegram-channels/.

US Department of Defense, Strategic Communication: Joint Integrating Concept, ii. Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 7 October 2009. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA510204.pdf.

“V Akademiyi SBU prezentuvaly monohrafiyu pro stratehichni komunikatsiyi v umovakh hibrydnoyi viyny” [A monograph on strategic communications in the conditions of hybrid warfare was presented at the SSU Academy]. Ukrinform, October 23 (2021). https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-antifake/3337964-v-akademii-sbu-prezentuvali-monografiu-pro-strategicni-komunikacii-v-umovah-gibridnoi-vijni.html.

“Yak zhurnalistam pratsyuvaty v mistakh, de zaraz perebuvaye voroh i tochat'sya boyi?” [How can journalists work in cities where there is the enemy now and fighting is going on?], NSJU.org. (2022). https://nsju.org/novini/zhurnalisty-vsi-na-vijni-prosto-odni-u-vijskovij-formi-inshi-v-studiyi-sekretar-nszhu-volodymyr-danylyuk/.

Yuskiv, Bohdan and Nataliia Karpchuk. “Dominating Concepts of Russian Federation Propaganda against Ukraine (Content and Collocation Analyses of Russia Today).” Politologija 102, no. 2 (2021): 116–152. https://www.journals.vu.lt/politologija/article/view/24506.

Yuskiv, Bohdan, Nataliia Karpchuk, and Sehii Khomych. “Media Reports as a Tool of Hybrid and Information Warfare (the Case of RT – Russia Today).” Codrul Cosminolui 1, 27 (2021): 235–258. http://codrulcosminului.usv.ro/CC27/1/12.html.

Zerfass, Ansgar, Dejan Verčič, Howard Nothhaft, and Kelly Page Werder. “Strategic Communication: Defining the Field and its Contribution to Research and Practice.” International Journal of Strategic Communication 12, 4 (2018): 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485.

Zolotukhin, Dmytro. “Shcho konkretno (i chomu) ne mozhna povidomlyaty i pokazuvaty v media pid chas viyny” [What exactly (and why) cannot be reported and shown in the media during the war]. Detector Media, March 30 (2022). https://detector.media/infospace/article/197960/2022-03-30-shcho-konkretno-i-chomu-ne-mozhna-povidomlyaty-i-pokazuvaty-v-media-pid-chas-viyny/.

ВКП 10-00(49).01. Doktryna zi stratehichnykh komunikatsiy [Doctrine of strategic communications]. Kyiv, 2020.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29