Politologija ISSN 1392-1681 eISSN 2424-6034

2025/3, vol. 119, pp. 14–43 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Polit.2025.119.1

Vitalis Nakrošis

Professor at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University

E-mail: vitalis.nakrosis@tspmi.vu.lt

Ramūnas Vilpišauskas

Professor at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science, Vilnius University

E-mail: ramunas.vilpisauskas@tspmi.vu.lt

Abstract. This article introduces a special issue dedicated to examining the management of the polycrisis and the policy responses of Lithuanian governments and public sector organisations between 2021 and 2025. We analyse operational practices in public sector governance and strategic decisions made by national and international/supranational authorities in the domains of migration, energy, and sanctions policy, all within a broader geopolitical context. The article presents the theoretical framework for analysis and research methodology employed in the policy-specific articles of this special issue. Our research also seeks to uncover any spillover effects among individual crises, to identify differences in policy response and crisis management across different policy areas, and to provide suggestions for future research on resilience in public management in the evolving geopolitical context.

Keywords: polycrisis, paradigms of response, crisis coordination, governance capacity, operational response, strategic decisions, Lithuania.

Santrauka. Šiame įvadiniame straipsnyje pristatomas specialus numeris, skirtas daugialypės krizės valdymo ir Lietuvos valdžios institucijų atsako 2021–2025 m. nagrinėjimui. Platesniame geopolitiniame kontekste analizuojamos operacinės praktikos viešojo sektoriaus valdyme ir nacionalinių bei viršvalstybinių / tarptautinių institucijų strateginiai sprendimai migracijos, energetikos ir sankcijų politikos srityse. Straipsnyje pristatomas teorinis analizės pagrindas ir metodika, taikoma šiame specialiame numeryje publikuojamuose, į atskiras politikos sritis orientuotuose straipsniuose. Šiame tyrime taip pat siekiama atskleisti galimus persiliejimo tarp individualių krizių efektus, nustatyti galimus politikos atsako ir krizės valdymo skirtumus tarp įvairių viešosios politikos sričių, taip pat pateikti siūlymų dėl būsimųjų tyrimų, orientuotų į atsparumo stiprinimą viešajame valdyme besikeičiančioje geopolitinėje aplinkoje.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: daugialypė krizė, atsako paradigmos, krizės koordinavimas, valdymo gebėjimai, operacinis atsakas, strateginiai sprendimai, Lietuva.

_________

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for the valuable feedback on this article, as well as the interviewees who participated in the implementation of the interview programme.

Received: 01/04/2025. Accepted: 22/08/2025

Copyright © 2025 Vitalis Nakrošis, Ramūnas Vilpišauskas. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

_________

“We live in such times when crises are piled on top of each other. So we have such polycrisis times. And ‘uncertainty’ remains the key word, as we try to describe predictions for 2024.”

Ingrida Šimonytė, Prime Minister of the Republic of Lithuania,

Verslo žinios (Business News) conference Business 2024, 28 November 2023.

In recent years, many European countries, including Lithuania, have encountered many transboundary crises. Unlike the COVID-19 pandemic, recent crises such as the migration crisis, the energy (cost of living) crisis, and the still ongoing security crisis have been catalysed by the increasing aggressiveness of neighbouring authoritarian states. These crises are interconnected manifestations of a broader geopolitical crisis in Europe and beyond, including the crisis of transatlantic relations triggered by the Donald Trump administration in 2025.

As these crises overlap in time and space, their events can be defined and analysed as a single polycrisis. This term is attributed to the complexity theorist Edgar Morin, who was the first to use it in the 1990s while referring to the ecological alert that emerged in the 1970s.1 According to Adam Tooze, who recently reintroduced the concept, “in the polycrisis the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts.”2 Unlike the situation several decades ago, due to the speed and scale of transformations, as well as communication about them, it has become impossible to attribute the crises to a single cause and to offer a single solution.

Although the concept of a polycrisis was developed to enhance the understanding of interconnected global events, it is also relevant for exploring national policymaking or crisis management.3 We define a polycrisis as the simultaneous occurrence of at least two individual crises at the national level characterised by high complexity and/or spillover effects in terms of both policy domains (subsystems) and territorial boundaries.

Crises often spark significant shifts in policy and governance by exposing existing shortcomings and driving the creation of new solutions.4 They also offer crucial opportunities for learning, innovation, and reducing vulnerability to similar risks in the future,5 ultimately enhancing resilience in public management. Given the substantial pressure for change that polycrises usually generate, it is important to explore how governments specifically react to such multiple, overlapping crises.

While the nature of individual systemic threats and the specifics of managing individual (national) crises are well known, a significant research gap exists in our understanding of interconnected, transboundary crises, particularly those that overlap in time and space.6 Therefore, there is a pressing need for research that systematically analyses the management of such crises across all stages, explores their multifaceted effects on national policymaking and governance, and facilitates comparisons over time and across diverse policy areas. Besides, while most research on polycrises focuses on global issues like climate change, epidemics and financial shocks, our research examines the geopolitical crisis and its effects on interconnected public policy subsystems and levels of governance.

This article introduces a special issue examining how Lithuanian governments and public sector organisations responded to the recent polycrisis from 2021 to 2025. We analyse new operational practices in public sector governance and strategic decisions made by national and international/supranational authorities in the domains of migration, energy and sanctions policy. Our research also seeks to uncover any spillover effects among individual crises, to identify differences in policy response and crisis management across different policy areas, and to provide suggestions for future research on resilience in governance in the context of the evolving geopolitical reality in Europe and beyond.

This introductory article is divided into several sections. The first section elaborates a theoretical framework for analysis and sets out causal mechanisms for the study of the polycrisis. The second section outlines our research methodology. We finish the article by providing our overall conclusions and outlining some suggestions for further research.

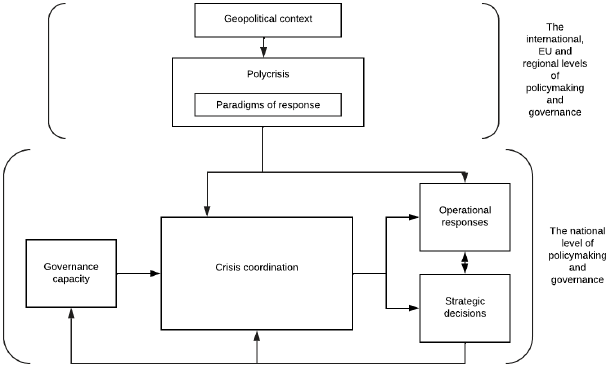

In our theoretical framework, we connect our independent variables, the polycrisis and the policy response paradigms associated with individual or multiple crises, with the intervening variables of governance capacity and crisis coordination. Crisis coordination can be affected by politicisation when policy responses become subjects of political contestation, potentially slowing down policy responses or/and leading to a reassessment of existing policy norms and institutions. These intervening variables then lead to our dependent variable: operational responses and strategic decisions (see Figure 1 below).

Source: authors of this article, based on desk research

These variables are assigned to different levels of analysis: the international, EU and regional level of policymaking and governance, within which polycrises usually emerge (taking into account the geopolitical context that shapes the nature of crisis events), and the national level of policymaking and governance, where operational responses and strategic decisions are made during the processes of crisis management. The arrows in the figure represent hypothesised mechanisms of influence (see below in this section) between individual variables, including feedback loops among them. This framework allows us to examine a multifaceted interplay between the nature of polycrises, the dynamics of crisis coordination, and the resulting operational responses and strategic decisions made and implemented by national authorities.

Since the policy problems generated by a polycrisis span across several policy subsystems and extend beyond national authorities, in our research, we adopt the analytical unit of a policy regime. Policy regimes are perceived as “governing arrangements that foster integrative actions across elements of multiple subsystems”.7 This unit of analysis is particularly well suited for our research purpose because it allows us to capture a diverse array of actors across different levels of policymaking and governance (national, regional, international/supranational) and complex interconnections among different (sectoral) policy subsystems, thus providing a more holistic understanding of the polycrisis situation.

The framework for analysis integrates insights from multiple disciplines, including public policy and administration, political economy, and international relations, as well as ideas from existing research on policy mixes and crisis management. However, we undertake to follow a comprehensive approach,8 providing an integrated assessment of multiple interconnected crises that constitute a single polycrisis, and analysing the feedback received from the implementation of operational responses and strategic decisions. This is important because modern crises are highly interconnected, and they cannot be understood or effectively managed in isolation.

The following sub-sections describe the individual elements of our theoretical framework and several links between them.

There has been some recent research on polycrises offering a conceptualisation of pathways that connect multiple global systems to synchronised crises.9 It has, however, focused on the emergence of global polycrises, particularly those related to the failure of the Earth’s natural and social systems.

In the EU context, previous research on crises has usually attempted to answer the question whether the crises strengthened or weakened the EU, and whether they led to further EU integration. Although individual studies of the EU’s response to crises such as the Eurozone and refugee crises pointed to the importance of the latter crisis taking place soon after the former, which contributed to the politicisation of crisis management in member states, and, as a result, imposed constraints on more coordinated EU-level actions, these linkages have not been explored in more detail.10 Therefore, it could be argued that this research has not sufficiently explored interactions between individual crises.

Recent research has leveraged the concept of polycrisis as an analytical lens to understand policymaking processes and outcomes in an increasingly interconnected world.11 This lens moved beyond viewing a polycrisis merely as an exogenous contextual factor by perceiving it as situations where distinct yet interacting crises amplify each other. The practical utility of this concept has also been explored at the national level, drawing on existing crisis management and crisis policymaking literature.12 Aligning with this conceptual approach, we further developed individual dimensions of the polycrisis, and suggested the main causal mechanisms between the polycrisis as a cause and its possible outcomes on national policymaking and governance.

While previous literature on crisis management explored different types of crises from different perspectives, there is no universally accepted definition of a ‘polycrisis’. Nevertheless, recent research has consistently identified several key dimensions that characterise this phenomenon.13 One crucial dimension is the simultaneous occurrence of a few crisis events in different policy fields, necessitating responses to several overlapping crises at a particular point in time. Another defining characteristic is the interconnected nature of individual crises within a polycrisis, with the potential to amplify each other’s impacts. For instance, responses to one crisis might be facilitated or constrained by the state of other ongoing crises, highlighting the complex feedback loops at play.

Additionally, we are particularly interested in various dynamic effects of a polycrisis, encompassing spillover (cascading and rippling) effects. These effects extend beyond the initial scope and policy field of individual crises, thus affecting other domains and territories. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic had far-reaching consequences across multiple dimensions, including public health, mental well-being, economic and social structures, as well as international supply chains and power dynamics between countries. Finally, the inherent complexity and uncertainty of a polycrisis make it difficult to predict the non-linear course of individual crises and their co-evolution, as well as to cope with the polycrisis having many interconnected parts and involving multiple stakeholders. Given these characteristics, examining crisis policymaking and governance necessitates the application of specific methodological approaches that allow for the analysis of several different aspects, rather than focusing on a single outcome and cause (see the following section).

Overall, we argue that a polycrisis should encompass at least two (and preferably more) interconnected crises, but they should feature a significant degree of complexity and/or generate some spillover effects across policy domains and territorial boundaries. In the absence of these features, the existing literature on disaster and crisis management should sufficiently address the analysis of individual crisis situations.

A series of crises recently faced by Lithuania resembles the aforementioned characteristics of the polycrisis. First, the country’s authorities simultaneously confronted a few interconnected crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic, a surge of illegal migration orchestrated by Belarus, and the inflow of Ukrainian refugees from Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, the crisis of increasing energy prices (or the ‘cost of living’ crisis), and escalating economic sanctions against Russia and Belarus in response to their violation of international norms. Second, all elements of this polycrisis arose from transboundary crises, and their management involved significant efforts to coordinate response measures within EU and sometimes NATO institutional formats. Since such crises blur organisational boundaries and challenge multiple actors, their management requires the involvement of both national and international institutions, as well as the development of various transboundary arrangements in crisis management.14 Third, the recent multiple crises generated several negative spillover effects. For example, the COVID-19 public health emergency led to an economic slowdown in Lithuania,15 while irregular migration and increasing energy prices strained resources in other domains. A more in-depth analysis of these spillover effects, both negative and positive, is crucial.

Furthermore, recent crises, such as the migration crisis, the energy (cost of living) crisis, and acts of sabotage against critical infrastructure, have been exacerbated by the increasing aggressiveness of neighbouring authoritarian states like Russia and Belarus. This situation further complicates crisis management, as cooperation with these authoritarian regimes is unattainable. Consequently, response efforts must prioritise national security in democratic states and focus on developing non-military strategies in response to ongoing hybrid attacks attributed to authoritarian neighbours. Therefore, while analysing the recent polycrisis, it is important to recognise the influence of the geopolitical context on crisis management and the growing reliance on economic sanctions by Western democracies as a non-military response (see the following sub-section).16 Therefore, as the article on the use of sanction argues, we contribute to the literature on crisis management by applying the geopolitical context to an analysis of policy responses by ‘front-line’ EU/NATO member states reacting to the hostile actions of authoritarian neighbours.

The role of dominant ideas in domestic and foreign policy has been explored by many scholars of public policy and international relations. Numerous studies have focused on the analysis of possible causal relationships between ideas, or policy paradigms, and policy changes,17 while also examining the limitations of historical and rational institutionalist frameworks.18

We start our analysis with the assumption that the importance of ideas about appropriate policy changes increases during times of crises, which are characterised by great uncertainty. Under such conditions, policymakers are confronted with a need for a quick response that is informed by available policy paradigms and systems of beliefs about the appropriate response in terms of changing the currently existing policies and institutions. We seek to understand how a particular policy response is adopted, by looking into dominant ideas among epistemic communities, bureaucracies and policymakers, tracing the reasoning behind concrete policy decisions in response to a crisis. Building on studies by institutionalists,19 we look into the compatibility of existing paradigms of policy response with the beliefs of policymakers in those policy subsystems and affected societal actors, as well as the administrative capacities of implementing institutions. We expect that stronger compatibility will lead to a faster, better-coordinated and more effective crisis response. Moreover, we expect that the crisis response will be faster and more consistent under the conditions of one dominant policy paradigm widely shared among policymakers rather than several competing ones.

We focus on assessing the compatibility of responses to simultaneous crises and their interrelationship, as well as identifying lessons learned from crisis management. This requires situating crisis management within the broader context of responses to overlapping crises. We explore how these overlapping crises shaped policymakers’ views of the appropriate response measures in relation to the goals of crisis management, reactions from stakeholders, and the implementation outcomes.

Thus, the dominant approach of the EU member states and other allies in responding to the aggressive actions of Russia against neighbouring countries such as Ukraine and against its own opposition activists was to impose targeted individual, financial and economic sanctions against officials and entities linked to violations of international norms. Since Russia’s aggressive military actions against Ukraine have been also accompanied by weaponising the supply of energy resources, Lithuania and most other EU member states reacted by subsidising the higher costs for consumers and enterprises, and diversifying their trade relations in order to reduce their dependence on supplies from Russia and to increase their resilience to such crises in the future. Within this broader context of geopolitical contestation, the weaponisation of migration by Belarus and Russia led policymakers to perceive the need for a physical barrier along the border with Belarus and its effective implementation.

It is important to assess not only the paradigms of direct responses to those crises, typically involving efforts to upload crisis management to the EU level and diversify national economic links to reduce dependencies and related vulnerabilities, but also their broader impact. Those interrelated crises and their escalation also had an impact on various other public policies, such as employment, migration, social support, energy, transport, security and defence, EU and NATO enlargement, and others, producing a more complex policymaking environment and adding to the need for effective coordination (see the following sub-section). For instance, in migration policy, the response paradigm exposed tensions between a securitised approach to the illegal migration crisis (treating illegal migration as a part of hybrid aggression with migrants’ pushbacks) and the view that focuses on the humanitarian aspects of immigration. Besides, when some crisis management decisions were politicised, they tested the cohesion of the ruling coalition and relations between the government and the president, sometimes leading to the reform of existing policy norms and institutions, as seen in the rapidly expanding sanctions regime.

To sum up, global or regional paradigms of policy response usually inform the process of crisis policymaking and governance, thus influencing the content of operational responses or strategic decisions. It is important to assess the alignment between operational objectives and strategic goals, along with examining the effectiveness of the policy instruments used for their implementation. Additionally, it is essential to consider spillover effects in terms of interactions across interrelated policy domains that are affected by crises and their management, particularly in the context of unforeseen events and consequences.

Coordination is crucial in responding to large-scale crises and disasters.20 Crisis management requires both vertical coordination across different levels of government and horizontal coordination within different policy domains, as well as with other countries, often through the institutions of the EU. This is even more critical when managing polycrises, especially those of a transboundary nature, because of their complexity. In such situations, greater integrative capacity is required for the effective coordination of multiple government activities and stakeholders.21

However, the potential for integrative problem solving and consensus seeking can be hindered by politicisation strategies pursued by political actors within a policy regime.22 Politicisation as a strategy occurs when political actors deliberately subject a policy issue (crisis management, in our case) to political modes of policymaking and control.23 In the wider context of confrontational politics, politicisation can lead to high polarisation and entrenched partisanship, hindering coordination efforts across different political institutions or parliamentary groups, and making crisis management more contested and complicated. However, politicisation can also lead to learning and upgrading the legal and institutional framework for crisis coordination (see the conclusions of this article below).

It has been observed that there is no single institutional set-up that favours effective coordination. Hierarchy, network, and various hybrid arrangements can be applied in practice. Incumbent governments can centralise power in their hands to drive their crisis responses from the top.24 When a transboundary crisis requires an international or supranational response, close coordination with the country’s transatlantic or European partners will be necessary. When a crisis spills over to other policy domains, governments are more likely to implement network-based coordination (see the following sub-section on spillover effects).

The ability of governments to react to individual crises also depends on a well-functioning state apparatus and the governance capacity of individual institutions. Governance capacity refers to both the formal structural and procedural features of the administrative apparatus and its informal elements that determine its actual functioning and results.25 There are different types of governance capacity, including coordination capacity, which is about bringing together different actors in the pursuit of joint action.26

A mismatch between the existing governing capacity and the capacity required to effectively manage a crisis presents a challenge to adopting and executing credible immediate responses. Therefore, the mobilisation of additional resources from diverse sources, including governmental and even non-governmental entities, such as NGOs, businesses or media, might become inevitable. This mismatch also defines the need for developing greater resilience in governance during the recovery phase. We expect that the likelihood of decisions being adopted in the aftermath of a crisis is strongest when this mismatch is high, the crisis persists for a long period of time, and the country is confronted with a polycrisis involving a few interconnected crises.

Analysing the management of a polycrisis requires carefully considering its complexities and spillover effects, while distinguishing it from the management of single crises. This can be achieved by integrating insights from complexity theory and new institutionalism.27

In low-complexity settings (e.g., those involving a single crisis affecting one policy field), institutional or policy change is driven by professional self-organisation in response to normative pressures or political control in reaction to coercive pressures. In contrast, in complex environments like a polycrisis, professional interdependence and non-linear interactions drive change when normative pressures prevail, while multi-level bargaining among different political actors dominates when under coercive pressures.28

This difference in complexity also affects predictability. In low-complexity settings, institutional or policy change is more predictable, with governments typically following standard crisis management procedures. Conversely, in more complex settings, interactions among various factors are harder to model, and new structural or procedural properties may emerge organically within the system.29

Furthermore, when a crisis spills over to other policy domains and territories, it becomes more probable that governments will introduce more inter-institutional arrangements of management or more network-based coordination, going beyond hierarchy. These strategies aim to create a more cohesive crisis management network by connecting individuals and information across policy areas and public sector organisations. Important changes are also likely to occur if spillover effects strain the already insufficient physical, financial, or human resources of public sector organisations, thus constraining an effective crisis response or delivery of public services.

Our main dependent variable is the strategic decisions by national and international/supranational authorities that address multiple interconnected crises and systemic future threats, as well as new operational practices in public sector governance developed within the broader policy and institutional framework.

While strategic and operational aspects of crisis management may overlap, we distinguish between them analytically based on their scope, time horizon, and decision-makers. Strategic decisions have a broader scope and longer-term focus, and involve high-level decision-makers (politicians and senior executives). Operational responses are narrower in scope, they focus on immediate actions, and are often made by managers responsible for day-to-day crisis management or ‘front-line’ professionals. While the operational level focuses on more technical and primary mitigation or recovery efforts, the strategic level usually addresses the social and economic consequences of crises, or their secondary impacts through political decision-making.30

In assessing crisis responses, we differentiated between strategic policy goals and instruments used to advance them in a particular policy field, as well as operational objectives and their implementation. In terms of policy content, the crisis response could lead to a reassessment of the strategic goals, the revision of instruments to advance them, or the implementation of previously agreed policy measures, aligning them with the dominant paradigm of policy response.

Disagreements on policy responses are likely to complicate crisis management with potential revisions after the next elections and a change in the ruling coalition and government. Another type of complication can arise when, due to a lack of capacity or insufficient policy coordination, inconsistencies become public, providing a basis to question the effectiveness of a policy response, or even the paradigm of response itself.

As a result of strategic decisions and operational responses, new governance practices can be introduced in national public administrations. They can encompass new forms of coordination and collaboration that could be facilitated through networks and stakeholder engagement.31 Collaborative governance that involves the mobilisation of new actors and the facilitation of working together can face some ‘downstream’ challenges during implementation, when it is necessary to develop joint solutions and achieve specific results.32

Another governance practice is agile or adaptive methods that are often employed by public sector organisations while responding to changing situations. If agility is related mainly to the speed of governance based on the application of soft or hard agile practices (such as agile mindset or Scrum), adaptivity implies that more system-level changes are needed to better align the functioning of different organisations with the changing environment.33 However, there are many challenges in importing agile and adaptive practices into traditional bureaucracies, especially in scaling new agile practices or applying successful experiments to the rest of the public administration or individual organisations.34

Governments can also embrace emerging technologies and new information solutions during periods of crisis. For instance, many digital tools were developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, after switching to online activities in education and public administration or introducing specific solutions for contact tracing. Although digitally induced change is usually pursued as part of the digital transformation agenda, a systematic literature review indicates that the implementation of digital technologies usually brings incremental change.35

The introduction of new governance practices can indicate the extent to which individual state institutions or public sector organisations actually pursue progressive goals and proactively embrace innovations in public office.36 However, these new practices are unlikely to have a transformational effect on the public administration system if there is limited progress during implementation or if they face important challenges scaling up.

Methodologically, we adopt the case study approach by focusing on processes of crisis policymaking and governance at the national level. This includes an examination of operational responses and strategic decisions within the crisis regime (at different levels of policymaking and governance), and individual policy subsystems.

We conducted three case studies on the country’s response to the crisis of illegal migration from Belarus (covering to some extent the influx of war refugees from Ukraine), the crisis of high energy prices, and the challenges associated with the implementation of international/EU economic sanctions against Russia and Belarus. These case studies were conducted under the Livia project funded by the Research Council of Lithuania.37 On the grounds of employing the embedded case study method,38 these empirical studies enabled the exploration of multiple units of analysis, while ensuring diverse empirical evidence and facilitating the exploration of links between individual crises.

Additionally, two case studies (the migration study and the analysis of the energy crisis) employed the process tracing method39 to trace causal mechanisms and explain their operation in specific cases. Meanwhile, due to its specific nature as an instrument for responding to geopolitical crises, the use of economic sanctions was analysed only by testing causal mechanisms derived from our analytical framework. This analysis was structured around the critical junctures that led to revisions in Lithuania’s sanctions policy and its institutional structure.

We used a theory-oriented version of causal process tracing,40 enabling us to validate whether our theoretical explanations align with the actual mechanisms at play ‘on the ground’. Given the historically unprecedented nature of interactions among individual crises41 and the limited existing knowledge about the mechanisms linking causes and outcomes in such scenarios, we explored theoretical expectations concerning several different aspects of crisis management and its outcomes (instead of focusing on a single outcome and cause).

This approach aligns with a minimalist version of the theory-testing process tracing by conducting a series of plausibility probes to determine if there is any empirical evidence supporting a hypothesised process.42 While acknowledging that causal inferences from the minimalist process tracing tend to be weaker compared to other types of causal process tracing, the primary goal is to identify common patterns in institutional responses to simultaneous crises and explore their interrelationships.

Our approach involved semi-structured interviews with key decision-makers and participants in Lithuania’s crisis management, focusing on the challenges posed by the polycrisis and its individual elements. In total, we conducted 22 interviews with 23 different interviewees, including six politicians, 15 civil servants and other public sector employees, and two business managers from various policy domains. About 35% of the interviews were with top-level decision-makers (government politicians and heads of state institutions and public sector organisations) in Lithuania.

Our interview programme adhered to the requirements of personal data protection, with explicit verbal consent obtained from each interviewee. The interviews were recorded and transcribed literally, and then analysed by using an open coding methodology.

We also conducted an analysis of documents and media reports, which allowed us to better trace the processes of crisis management. The results of our desk research were used for triangulating the interview data in order to avoid any potential biases associated with the dominance of (high-level) government representatives in our interview programme. Taken together, the mix of information sources used during our research ensures their triangulation and contributes to the reliability of our research findings.

The introductory article elaborated a theoretical framework for analysis and set out causal mechanisms that relate to the nature of policy response, the existence of governance capacity, the incidence of inter-institutional coordination, and the establishment of new governance practices.

The three articles in the special issue analysed the operational practices of public sector governance and the strategic decisions of Lithuanian and international/supranational authorities across migration, energy and sanctions policies, highlighting the country’s evolving policy responses and crisis management practices. They also explored links and spillover effects among individual crises within a broader geopolitical polycrisis.

Two articles in the special issue (the migration study and the analysis of the energy [cost of living] crisis) followed the methodology of minimalist process tracing, while the third case study (the analysis of economic sanctions) adopted a different approach tailored to the nature of this policy as an instrument for responding to the geopolitical crisis, i.e., undertaking the testing of the causal instruments structured on the basis of the critical junctures that led to the revision of Lithuania’s sanctions policy and its institutional structure.

The migration study demonstrated a shift towards a more securitised approach during the crisis of irregular migration that started in 2021 in Lithuania. After securing the tacit agreement of the European Commission on this approach, Lithuania adopted strategic decisions such as implementing migrant pushbacks and constructing a physical barrier on the border with Belarus. The migration crisis also strengthened Lithuania’s influence on EU migration policy, contributing to the adoption of the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum in 2024, which notably includes a clear definition of instrumentalised migration.

The analysis of the energy (cost of living) crisis showed that, on the operational level, the Lithuanian government adopted simple-to-administer, horizontal-relief measures to support households and businesses, an approach deemed effective from its use during the COVID-19 pandemic. On a strategic level, the crisis led to an increased support for the transition to renewable energy and a new energy security strategy focused on domestic generation of renewable energy. There was also a shift in the energy security paradigm, from decoupling from Russia through diversification and integration into the EU electricity and natural gas networks, to self-sufficiency based on domestic generation capacities. This shift was facilitated by the EU targets of transitioning to renewable energy and the reduction of pollution, as well as funding for installing solar and wind energy generation capacities provided by the NextGenerationEU instrument, a collective EU response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The analysis of economic sanctions adopted by Lithuania shows that its use was driven by perceived security concerns related to the potential escalation of Russia’s war beyond Ukraine into EU/NATO ‘Eastern Flank’ countries. In other words, the dominant paradigm of response focused on a future worst-case scenario and its effects, rather than on a cost-benefit analysis of sanctions introduced in response to the current violations of international norms by the aggressor. This allowed the country’s authorities to forge a stronger political and societal consensus, and to act faster. However, this paradigm diverged from the dominant policy paradigm among Lithuania’s strategic partners in the EU and NATO, thereby complicating the formulation of coordinated sanctions and their implementation.

On a strategic level, diversification away from authoritarian countries and the dominant view among policymakers that businesses should deal with geopolitical risks if they engage in transactions with such countries shaped the ideational context of sanctions policy, characterised by a drive to implement ‘as much as possible as soon as possible’. As the use of sanctions expanded and the consistent application of them became more challenging, the Lithuanian government revised its institutional set-up for coordinating sanctions policymaking and increased its capacities.

Concerns regarding a potential military escalation in Europe coupled with the ‘values-based’ foreign policy of the Lithuanian government led by Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė (2020–2024) played a key role in managing the spillovers of different episodes of the geopolitical polycrisis. For example, after Minsk responded to Lithuania’s and the EU’s sanctions by instrumentalising illegal migration in the summer of 2021, the country’s authorities reinforced the use of sanctions, and, after initial hesitation, constructed a physical barrier on the border with Belarus.

Across these crises, the primary spillover effect of the geopolitical crisis was to reinforce a widespread perception of policymakers across various interconnected policy domains that a strategic decoupling from authoritarian powers is required, more effective coordination with partners inside the EU and NATO is necessary, and the urgent need for more resilient domestic institutions and society should be addressed. This heightened awareness directly influenced major policy decisions and other modifications in areas ranging from economic diversification to national security.

Our case studies revealed a high degree of compatibility between existing policy paradigms and the beliefs of both policymakers and the affected societal actors. We observed a strong alignment in the areas of energy subsidies and sanctions. However, the migration policy paradigm presented a notable divergence in compatibility, with significant differences between governmental and civil society perspectives. This made it possible for the Lithuanian authorities to make strategic decisions across migration (implementing migrant pushbacks and constructing a physical barrier), energy (focusing on full energy independence in the country), and sanctions (supporting the adoption and implementation of EU-wide sanctions against Russia and Belarus), leading to significant and enduring changes in policy content.

During the pre-crisis period, Lithuania’s approach to coordination relied primarily on traditional or informal mechanisms, which proved insufficient for managing a polycrisis. As individual crises escalated and impacted various policy areas, Lithuania pivoted towards more centralised and inter-institutional crisis management. This shift necessitated the development of new, more effective cooperation mechanisms across government institutions. More specifically, the country’s lessons learned during the management of the COVID-19 pandemic and the migration crisis informed the formal establishment of the National Crisis Management Centre (NCMC) within the Government Office.43 Following parliamentary approval, the NCMC commenced operations on 1 January 2023. Operational since 1 January 2023, the NCMC also integrated the Ministry of the Interior’s Joint Situations Centre that was created in 2021 for enhancing inter-institutional coordination in the field of migration.

In contrast, ad-hoc informal coordination formats were mainly used for the management of the energy crisis and for responding to the increased geopolitical risks following Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine in 2022. This shows that an increased prevalence of institutionalised arrangements for crisis coordination at the centre of government can co-exist with more informal coordination practices in the adjacent policy domains in Lithuania’s public administration. However, such ad-hoc formats are likely to be temporary and depend on both the persistence of the specific crisis (functional demand) and political willingness (supply).

New governance practices adopted during the polycrisis included collaborative governance, agile management, and digital governance, as anticipated in our theoretical approach. Examples include a swift recruitment or deployment of additional personnel, mobilisation of national and EU financial resources, and integration of IT innovations (such as the Migris platform in the Migration Department under the Ministry of the Interior) in the policy domain of migration. The energy domain witnessed a rapid digitisation and robotisation of the implementation of energy policy measures. In the realm of economic sanctions, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs established a dedicated sanctions group and an inter-institutional commission to better coordinate international sanctions policy, while the State Data Agency started tracking export flows to sanctioned and transit countries. These actions highlight the importance of enhancing governance capacity for effective crisis response, and exhibit important differences across various policy domains. They also reveal important differences in the adoption of specific governance practices across policy domains, depending on the actual needs of each field and the specific responses of the responsible policymakers.

These governance developments reflect the Lithuanian government’s proactive approach to innovation in governance and commitment to progressive goals.44 However, it remains too early to determine whether these practices will have a lasting transformational impact on public administration, given the sustainability risks. Nonetheless, the ongoing security crisis and the application of these measures suggest a positive outlook for their long-term effectiveness.

The horizontal support measures and institutional practices adopted in response to the energy crisis were based on lessons learned from the management of economic support measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the instruments developed during the migration crisis proved appropriate and effective to the management of subsequent crises, such as the influx of war refugees from Ukraine. This demonstrates an effective transfer of lessons learned from previous crises to the management of subsequent similar events.

Lithuania framed the migration crisis as an EU external border issue, promoting coalition-building and policy advocacy at the EU level. The efforts resulted in successfully applying the policy response to instrumentalised migration to the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum. Similarly, previous efforts by Lithuanian authorities to diversify the supply of energy resources from Russia, which allowed the country to declare complete decoupling from Russia in the spring of 2022, were used as evidence of a successful energy diversification policy in discussions with its EU/NATO partners to back proposals for more sanctions against the aggressor in the energy sector (and to support the proposal of the European Commission for the EU to end all fossil fuel imports from Russia by 2027). These examples illustrate how the management of the polycrisis extended to the adoption of important decisions at the international/supranational level within the broader regime of crisis management.

Our research also points to a number of specific directions for future research. For instance, a comparative analysis of crisis management reforms in a few European countries characterised by variation in contextual, political, policy or institutional conditions could shed some light on the importance of different conditions and resulting operational responses or strategic decisions. Further analysis could explore the cooperation of Lithuanian authorities with their EU and NATO partners in managing transboundary crises, focusing on factors that enable the effective application of its policy preferences.

Also, it is important to conduct a more in-depth analysis on the impact of policy responses and crisis management practices on enhancing resilience in governance. In the current context of strained transatlantic relations and the deteriorating security situation in Central and Eastern Europe, the ability of governance systems to ‘bounce forward’ is crucial. This involves absorbing shocks, adapting to new crisis situations, and transforming to be better prepared for future systemic threats. Finally, future research should explore how political cycles in Lithuania and its strategic partners, especially the US after President Donald Trump’s election, affect the management of the geopolitical polycrisis and the associated continuity and change of policy responses amid the growing uncertainty.

Vitalis Nakrošis: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, visualisation.

Ramūnas Vilpišauskas: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Main references

Anghel, Veronica and Erik Jones. “Is Europe really forged through crisis? Pandemic EU and the Russia – Ukraine war.” Journal of European Public Policy 30, No. 4 (2023): 766–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2022.2140820

Bang, Henrik and David Marsh. “Populism: A major threat to democracy?” Policy Studies 39, No. 3 (2018): 352–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2018.1475640

Beach, Derek and Rasmus Brun Pedersen. Process-Tracing Methods: Foundations and Guidelines. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor (Mich.): University of Michigan press, 2019.

Birkland, A. Thomas. Lessons of Disaster: Policy Change after Catastrophic Events. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Birkland, A. Thomas. “Learning and Policy Improvement after Disaster: The Case of Aviation Security.” American Behavioral Scientist 48, No. 3 (2004): 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0002764204268990.

Blyth, Mark M. “Any more bright ideas?” The ideational turn of comparative political economy.” Comparative Politics 29, No. 2 (1997): 229–250.

Boin, Arjen and Paul ’t Hart. “From crisis to reform? Exploring three post-COVID pathways.” Policy and Society 41, No. 1 (2022): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc

Boin, Arjen. “The Transboundary Crisis: Why we are unprepared and the road ahead.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 27, No. 1 (2019): 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12241

Boin, Arjen and Fredrik Bynander. “Explaining success and failure in crisis coordination.” Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography 97, No. 1 (2015): 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoa.12072

Bortkevičiūtė, Rasa, Patricija Kalkytė, Vytautas Kuokštis, Vitalis Nakrošis, Inga Patkauskaitė-Tiuchtienė, Ramūnas Vilpišauskas. Nuo greitų pergalių prie skaudžių pralaimėjimų: Lietuvos viešosios politikos atsakas į COVID-19 pandemiją ir šios krizės valdymas 2020 m. Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2021.

Borzel, Tanja A. and Thomas Risse. “From the euro to the Schengen crises: European integration theories, politicization and identity politics.” Journal of European Public Policy 25, No. 1 (2018): 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310281

Christensen, Tom, Per Lægreid, Lise H. Rykkja. “Organizing for Crisis Management: Building Governance Capacity and Legitimacy.” Public Administration Review 76, No. 6 (2016): 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12558

Coaffee, Jon. Futureproof: How To Build Resilience In An Uncertain World. Yale University Press, 2019.

Davies, Mathew and Christopher Hobson. “An Embarrassment of Changes: International Relations and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 77, No. 2 (2023): 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2022.2095614.

Dinan, Shannon, Daniel Béland, Michael Howlett. “How useful is the concept of polycrisis? Lessons from the Development of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Policy Design and Practice, 7, No. 4 (2024): 430–441. DOI: 10.1080/25741292.2024.2316409

Feindt, Peter H., Sandra Schwindenhammer, Jale Tosun. “Politicization, Depoliticization and Policy Change: A Comparative Theoretical Perspective on Agri-food Policy.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 23, No. 5–6 (2020): 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2020.1785875

Gerrits, Lasse and Peter Marks. “How the complexity sciences can inform public administration: an Assessment.” Public Administration 93, No. 2 (2015): 539–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12168

Hall, Peter A. “Policy paradigms, social learning and the state: the case of economic policy making in Britain.” Comparative Politics 25, No. 3 (1993): p. 275–296.

Hannah, Adam, Erik Baekkeskov, Tamara Tubakovic. “Ideas and crisis in policy and administration: Existing links and research frontiers.” Public Administration 100, No. 3 (2022): 571–584, DOI: 10.1111/padm.12862

Haug, Nathalie, Sorin Dan, Ines Mergel. “Digitally-induced change in the public sector: a systematic review and research agenda.” Public Management Review 26, No. 7 (2023): 1963–1987. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2023.2234917

Homer-Dixon, Thomas, Ortwin Renn, Johan Rockström, Jonathan F. Donges, Scott Janzwood. A Call for An International Research Program on the Risk of a Global Polycrisis. July 20, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4058592

Janssen, Marijn and Haiko van der Voort. “Agile and Adaptive Governance in Crisis Response: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Information Management 55, December (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102180

Jochim Ashley E. and Peter J. May. “Beyond Subsystems: Policy Regimes and Governance.” Policy Studies Journal 38, No. 2 (2010): 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00363.x

Kay, Adrian and Phillip Baker. “What Can Causal Process Tracing Offer to Policy Studies? A Review of the Literature.” Policy Studies Journal 43, No. 1 (2014): 1–21. DOI: 10.1111/psj.12092

Lawrence, Michael, Thomas Homer-Dixon, Scott Janzwood, Johan Rockstrom, Ortwin Renn, Jonathan F. Donges. Global polycrisis: The causal mechanisms of crisis entanglement, June 18, 2023. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4483556

Lodge, Martin and Kai Wegrich (eds.). The Problem-solving Capacity of the Modern State: Governance Challenges and Administrative Capacities. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Mergel, Ines, Sukumar Ganapati, Andrew B. Whitford. “Agile: A New Way of Governing.” Public Administration Review 81, No. 1 (2021): 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13202

Mulder, Nicholas. The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2022.

Nakrošis, Vitalis and Ramūnas Vilpišauskas. “The Impact of the Polycrisis on Systemic Change in Lithuania: Centralisation and Inter-institutional Cooperation Amid Geopolitical Turbulence.” Paper for the IIAS-DARPG 2025 conference, New Delhi, India, February 10–14, 2025.

Nohrstedt, Daniel, Fredrik Bynander, Charles Parker, Paul ’t Hart. “Managing Crises Collaboratively: Prospects and Problems – A Systematic Literature Review.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1, No. 4 (2018): 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppmgov/gvx018

Scholz, Roland W. and Olaf Tietje. Embedded case study methods: Integrating quantitative and qualitative knowledge. Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2002.

Sørensen, Eva and Jacob Torfing. “Radical and disruptive answers to downstream problems in collaborative governance?” Public Management Review 23, No. 11 (2021): 1590–1611. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1879914

Tooze, Adam. “Welcome to the world of the policrisis.” Financial Times. October 28, 2022. Accessed March 13, 2025. https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33

Zaki, Bishoy L., Valérie Pattyn and Ellen Wayenberg. “Policymaking in an age of polycrises: emerging perspectives.” Policy Design and Practice 7, No. 4 (2024): 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2024.2432048