Problemos ISSN 1392-1126 eISSN 2424-6158

2025, vol. 107, pp. 148–162 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Problemos.2025.107.11

Andrey Gavrilin

University of Tartu, Estonia

andrey.gavrilin@ut.ee

https://ror.org/03z77qz90

Abstract. Human history is largely shaped by human actions – most historical events are man-made, despite nature also playing a role. Yet, people often see these events as alien, as if shaped by something or someone else. For instance, many view man-made climate change as unrelated to humanity, while non-deniers often see no way to influence it collectively. This disconnection mirrors Marx’s concept of alienation. I argue that alienation applies not only to labour but to all human-made outcomes, including historical events – this is a phenomenon I refer to as historical alienation. Estrangement from economic and political processes can lead people to feel that history is beyond their control. This perspective helps explain presentism and passivity in the face of crises, suggesting that increasing conscious participation in collective decision-making could mitigate these effects.

Keywords: Presentism, Alienation, Hartog, Marx, Philosophy of history.

Santrauka. Žmonių istoriją iš esmės suformavo žmonių veiksmai. Daugelis istorinių įvykių įvyko žmogaus dėka, nors gamta taip pat juose atliko savo vaidmenį. Tačiau žmonės dažnai į tokius įvykius žiūri kaip į svetimus, tarytum juos būtų suformavęs kažkoks kitas fenomenas ar veikėjas. Pavyzdžiui, žmogaus sukelta klimato kaita daugybės žmonių suvokime yra nesusijusi su žmonija, o tie, kas neneigia klimato kaitos, daugeliu atvejų nemato būdo kolektyviai paveikti šią kaitą. Šis atsietumas atspindi Marxo susvetimėjimo sąvoką. Straipsnyje teigiu, kad susvetimėjimas taikytinas ne tik darbui, tačiau ir visoms kitoms žmogaus sukeltoms pasekmėms, įskaitant ir istorinius įvykius – tai yra reiškinys, kurį vadinu istoriniu susvetimėjimu. Šis nutolimas nuo socioekonominių ir politinių procesų gali priversti žmones manyti, kad istorija yra už jų kontrolės ribų. Tokia perspektyva padeda paaiškinti prezentizmą bei pasyvumą krizių akivaizdoje. Todėl būtų galima teigti, kad augantis sąmoningas dalyvavimas kolektyviniame sprendimų priėmime galėtų sušvelninti šias pasekmes.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: prezentizmas, susvetimėjimas, Hartogas, Marxas, istorijos filosofija

_________

Received: 20/08/2024. Accepted: 07/06/2025

Copyright © Andrey Gavrilin, 2025. Published by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Philosophers of history often describe history as a human creation (Collingwood 1946, 212), but Anthropocene1 theorists challenge this view, by emphasizing the entanglement of human and natural histories and critiquing the neglect of nature’s agency (Chakrabarty 2009, 209). Yet the Anthropocene itself is anthropogenic – marked by the first nuclear test (Steffen et al. 2018; Lenton et al. 2019) – and its key crises, especially climate change, are human-made. As Bonneuil and Fressoz (2016) note, history remains predominantly human-driven unless replaced by a fully non-anthropocentric framework, such as Chakrabarty’s (2009, 197, 206).

Climate change exemplifies what I call historical alienation: despite being anthropogenic, it is often experienced as a natural, external force (Chakrabarty 2009, 221)2. Although over 90% of people in North America and Europe recognize climate change3 (Lee et al. 2015, 1016), this rarely leads to action: behavioral change is minimal (ibid., 1018). Many distance themselves psychologically, believing they cannot make a difference – individually or collectively4, and live in what Norgaard (2011, 50) calls ‘double reality’ when the threat is acknowledged, but what is presented as distant and meaningless (Spence et al. 2012, 970). This reflects Marx’s concept of alienation, where workers face the products of their labor as alien (Marx 1978, 71). Even the deeply concerned may become inert if they feel powerless (Landry et al. 2018, 19–20). This is not ignorance, but, instead, alienation from collective agency.

Such dynamics recur across man-made crises. For instance, during Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, many citizens privately opposed the war yet felt powerless – mirroring the helplessness reported by conscripts themselves (Loginova and Verstka 2024, 107)5. More broadly, contemporary societies seem trapped in an ‘endless present’, unable to imagine alternatives (Hartog 2015, 17; Fisher 2009, 5).

This article treats climate change as the paradigmatic case of historical alienation: a human-made crisis perceived as beyond human control. It shows how externalizing events obscures their collective origins – and hinders collective response. The logic of Marx’s theory of alienation extends to history: citizens encounter outcomes they have helped shape as if they were natural or inevitable. Historical alienation thus sustains presentism, political detachment, and climate inaction by undermining belief in the possibility of change. While not the sole factor shaping these perceptions, it provides an additional explanation for them.

This article contributes to four areas. In Marxist theory, it expands the concept of alienation to encompass political and historical dimensions (Marx 1978, 71). In political philosophy, it reinterprets democratic disengagement as alienation – where institutions seem external and unresponsive (Brown 2015, 88). In the philosophy of history, it examines how fatalism and apathy emerge when change appears beyond human control (Hartog 2015, 17; Chakrabarty 2009, 221). In social theory, it connects alienation to emotional coping strategies like denial and distancing (Norgaard 2011, 50; Seeman 1959, 784). Together, these insights suggest that restoring collective agency through democratic participation is essential to confronting today’s crises of action and imagination.

The sections that follow elaborate this framework through Marx, Brown, Hartog, Chakrabarty, and others, by linking political philosophy and the philosophy of history to contemporary crises. “Economic Alienation” analyzes the Marxist logic of estrangement in labor; “Political Alienation” applies this to civic life, showing how exclusion from decision-making fosters disempowerment; “Historical Alienation” argues that these dynamics converge, making history itself appear beyond human influence. Enhancing democratic participation may help counter these effects.

Marx’s theory of alienation, developed in the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, explains how individuals become estranged from their own creations under specific social conditions. Drawing on the German philosophical tradition – where Entäusserung (externalization) and Entfremdung (estrangement) were used by Fichte6, Feuerbach7, and Hegel (Puusalu 2019, 30–35) – Marx redefined alienation in material and social terms. It arises when people are separated from their productive activity, its outcomes, their fellow humans, and the structures they co-create. These human-made realities then appear as external and dominating forces. The worker confronts the product of labor “as to an alien object” (Marx 1978, 71).

Although Marx never offered a single definition, he described alienation as having a dual character: (1) an objective loss of control over labor and its results, and (2) a subjective failure to recognize those results as products of one’s own agency. These dimensions may occur together or independently8. Sociologist Melvin Seeman (1959, 784) termed this condition ‘powerlessness’, capturing how structural and experiential elements reinforce each other. This article adopts Marx’s dual view: alienation involves both disempowerment and estrangement.

Modern theorists often emphasize one side. Bertell Ollman (1971) highlights the objective aspect, portraying alienation as the fragmentation of human life under capitalism – a severing of ties essential to freedom (Ross 2020). Rahel Jaeggi, by contrast, focuses on the subjective, defining alienation as the loss of self-determination, where one can no longer “have oneself at one’s command” (Jaeggi 2014, 32–33). For her, it reflects a rupture in the relation between self and the world, where action no longer expresses authentic will. Jan Kandiyali (2020, 564), an analytical Marxist, argues that alienation primarily prevents workers from helping one another achieve self-realization.

Marx, however, grounds his conception of labor in material conditions. Labor is not mere subsistence but a world-creating activity through which humans express their nature, the “objectification of man’s species-life” (Marx 1978, 76). Alienation disrupts this unity: labor and its products become foreign, and the world no longer feels like one’s own. Institutions, social relations, and objects confront the individual “as something alien, as a power independent of the producer” (Marx 1978, 71). Even capitalists are subordinated to the imperatives of capital, lacking true control (Marx 1978, 326, 133). A process meant to realize human essence ends up subjugating it – making it possible to extend the concept of alienation beyond the economic to political and historical spheres.

In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx presents alienation as a multi-stage process. When labor is expropriated, ontological estrangement gives rise to psychological effects (Marx 1978, 71, 4). Labor, for Marx, is not merely instrumental but a central form of self-expression. Alienation begins when the worker’s product is appropriated (Marx 1978, 72) and labor becomes something sold rather than lived (ibid, 326). The worker no longer recognizes himself9 in the outcome, confronting it “as a power independent of the producer” (ibid., 71–72).

This alienation also distorts the labor process. Lacking control over what or how they produce, workers feel that their time10 is owned by others and their creativity is estranged. Coworkers become competitors, concealing the collective nature of production (ibid., 483). Blauner (1964) found similar patterns in factory settings, where lack of control bred isolation and disempowerment. Kandiyali argues that meaningful labor supports self-realization when oriented toward others. Working only for a paycheck undermines both personal growth and collective meaning (Kandiyali 2020, 572).

As production grows more interdependent11, workers lose awareness of their ties to others (Marx 1978, 75–76)12. Commodity fetishism spreads, obscuring social and economic relations (Marx 1978, 321; Cohen 1972, 186). Understanding connections between producers and consumers requires specialized knowledge (Cohen 1972, 200–201), making the economy appear autonomous, governed by impersonal laws (ibid., 325). Even civilization13, built through collective labor, feels alien (Marx 1978, 76, 87).

Capitalists too are bound by capital’s logic, forced to prioritize profit over social aims (Marx 1978, 326). Alienation affects all classes by obscuring collective agency (ibid., 156). Øversveen (2022, 442) emphasizes that capitalism turns labor into impersonal force, making economic structures seem self-operating. Attempts to address crises like climate change often feel futile – if individual impact seems negligible, why act?

For example, this is how economic alienation complicates climate action:

1) Workers struggle to see how their labor contributes to climate change due to opaque, complex systems.

2) Production structures appear externally imposed, reinforcing the belief that economic processes are immutable.

3) Consumers, shaped by commodity fetishism, fail to connect goods to their ecological costs.

4) Producer-consumer relations remain obscured; even ethical consumers often feel powerless. Markets appear indifferent to collective moral concerns.

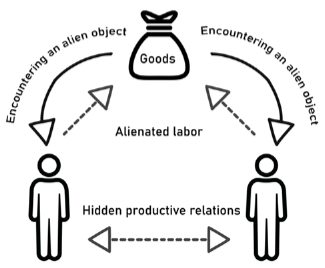

Producers and consumers alike often doubt the effectiveness of personal or collective action. Here, alienation is not just detachment from outcomes, but a loss of shared agency. A hypothetical scenario of non-alienated labor clarifies the contrast: individuals would choose what and when to produce, retain ownership over their work, and recognize the human effort embedded in goods14 (Figure 2). They would also see how their labor supports others’ well-being (Kandiyali 2020, 572). While full de-alienation may be unrealistic in complex economies – and perhaps not even optimal (ibid., 557–558) – greater workplace democratization could reduce alienation and enhance ecological awareness.

Alienation also distorts how people perceive their power. Ideology (Brown 2015, 95), beliefs, and material conditions may mediate or override it. Those with economic or political leverage may still act as agents of change. Even those alienated from labor can feel politically empowered through voting or activism.

This complexity shows that alienation manifests politically, where exclusion from decision-making deepens disempowerment. Politics, in turn, shapes economic dynamics and historical trajectories. Perceptions of historical impotence often arise from both economic alienation and political marginalization.

Marx and Engels argued that political institutions emerge from and reflect the economic base: “the totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real basis from which rises a legal and political superstructure” (Marx 1978, 150–51). Engels later recognized that laws, ideologies, and constitutions can also in their turn temporarily shape historical development before economic forces reassert their own primacy (Engels 1890/1978).

This dialectical view allows political alienation to be treated as a distinct, though economy-conditioned, phenomenon. Like labor, political participation is a mode of human agency. Aristotle called humans ‘political animals’, and Wendy Brown argues that people shape the world through both production and decision-making (Brown 2015, 88).

Brown agrees that political decisions can reshape the economy (Brown 2015, 207–208). Even amid economic alienation, political agency endures, making politics central to collective life. If alienation involves collective powers appearing external, then politics becomes a primary site of inquiry. In Undoing the Demos, she describes politics and economics as interdependent domains: the former enables collective rule, whereas the latter governs material life (ibid., 81, 202). Unlike Marx, she argues that politics can transform the economic base (ibid., 207–208).

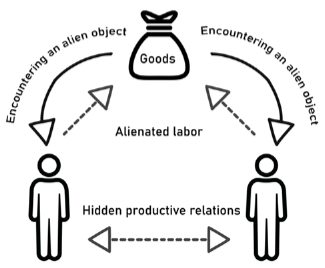

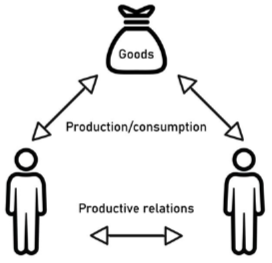

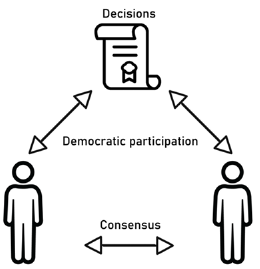

It mirrors economic alienation structurally: decisions, like products, become estranged – from citizens instead of workers (ibid., 88, 202). In a non-alienated democracy, outcomes reflect the collective will; whereas, in an alienated one, technocratic processes prevail, reducing participation to symbolic acts. When engagement lacks impact, decisions feel imposed. This echoes Lukács’s reification theory: institutions appear autonomous, obscuring their human origins (Lukács 1923). Cohen (1978) similarly argues that the state constructs a false unity through symbols and law, masking the labor behind social order. Political ideology, like commodity fetishism, portrays politics as a detached realm.

Seeman identifies ‘political powerlessness’ as a measurable form of alienation. When people say, “People like me don’t have any say in what the government does”, they express a defining symptom (Seeman 1959, 786). New taxes or war policies passed without public input feel imposed – “they decided”, “they are doing”.

Marxist theory sees this as ideological mystification: capitalism fosters civic fetishism as it does commodity fetishism (Marcuse 2007, 172). Institutions appear abstract and autonomous. As Lukács noted, people treat the state “as if it were a thing”, while forgetting that it is a collective product. Cohen (1978) adds that, in class societies, cohesion stems not from shared agency but from state-imposed illusions. Political alienation thus blends subjective resignation with structural exclusion (see Figure 3).

People often assign political power to vague abstractions like ‘the masses’, as remote as the market15. This occurs even in democracies, where formal rights remain but often feel ineffectual. Brown argues that neoliberalism intensifies this alienation by redefining citizens as market actors. Democratic institutions begin to resemble managerial structures, policies mimic market transactions, and confidence in collective agency declines (Brown 2015, 17–19, 88–90). Neoliberalism further casts the economy as self-regulating and beyond political reach16 (ibid., 81–82). A feedback loop forms: economic alienation fuels political alienation17 – and vice versa (ibid., 129–30).

When decisions appear controlled by elites or faceless institutions, individuals withdraw. Slothuus defines this fatalism as the conviction that change is futile, which leads to resignation and disengagement (Slothuus 2025, 41–43). This externalization aligns with Marx’s view of alienation as structural disempowerment, not natural passivity. Just as alienated workers feel isolated, alienated citizens experience political life as atomized. Voting and expression occur individually, social trust erodes; ‘the people’ becomes a distant abstraction – akin to how ‘the market’ appears in economic life.

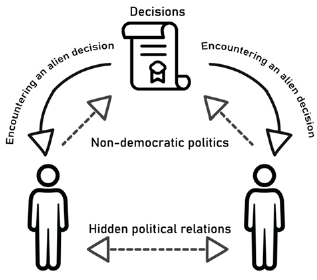

This dynamic helps explain why many, even in democracies, doubt the state’s ability to act – especially on climate change. Political alienation stems from exclusion from decision-making. In a non-alienated democracy, decisions would reflect the collective will, and both the state and society would be seen as shared creations (Figure 4).

Democracy requires more than voting – it depends on continuous engagement. When citizens are reduced to passive roles, politics feels distant, fueling cynicism and disempowerment (Pateman 1970, 25–30). Participatory institutions – cooperatives, town halls, deliberative forums – foster a sense of ownership and help counter alienation (ibid 1970., 130–35). Dictatorships, even when they mimic democratic forms, keep power centralized. But there, alienation can affect rulers too: despite their authority, they may feel constrained by institutional or ideological structures, like capitalists in Marx’s theory (Marx 1978, 326), yet alienation persists – concentrated rather than resolved.

In flawed democracies or hybrid regimes, alienation is visible when citizens see no path to reform. Climate change offers a case in point:

1) People feel powerless to shape the climate policy;

2) Even where influence exists, they doubt it produces results;

3) If reform demands challenging an ‘untouchable’ economy, policy appears futile.

Economic and political alienation share a structure, yet political alienation is wider. Together, these forms obscure human agency – not only in shaping the present but in pursuing alternative futures. This brings us to historical alienation, which, though grounded in these dynamics, must be examined on its own terms.

Since economic and political forces largely drive historical development, alienation from these domains fosters alienation from history, from the mechanisms of change. But why treat historical alienation as a distinct phenomenon rather than a derivative of economic or political estrangement? Although it may originate in those, it manifests uniquely – in how people perceive time, agency, and meaning. It describes a specific disconnection from historical transformation and has distinct psychological and cultural effects.

I define historical alienation as a distinct estrangement in which individuals perceive history as unfolding beyond human agency or comprehension, feeling that large-scale developments occur autonomously, as if they “just happen” (Beck 1992, 33–34; Cohen 1972, 200–201). Although our actions shape events, many do not feel they are making history. The present appears immovable, and since avoiding future crises requires changing the present, such change feels impossible. Slothuus describes it as both a cognitive denial of agency and an emotional stance of resignation (Slothuus 2025, 41–43). In this state, people feel powerless to shape history’s course. Because historical developments are diffuse and offer little individual feedback, the sense of participation often fades. History is seen as something that happens to us, and not something we make.

Marx famously observed, “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please” (Marx 1978, 595). Today, historical alienation stems as much from the present as from the past. A financial metaphor clarifies this: the past is inherited capital – wealth or debt – but empowerment depends on present capacity to act. A poor person with opportunities may feel more empowered than a rich one trapped in stasis.

The future depends on present political and economic agency. Through decisions and actions, people can redirect history – waging war, forging peace, advancing industrial18 or technological revolutions (Simon 2018, 107). As Simon notes, change becomes possible when people “participate in an effort to move history in a certain direction” (Simon 2018, 106–107). Restoring collective agency is essential to overcoming political fatalism. The capacity to imagine a future different from the present enables “feasible stories to act upon” (Simon 2018, 116). Without such narratives, alternatives collapse into a status quo so entrenched that ‘realistic’ futures become indistinguishable from the present (Marcuse 2007, 75, 150). In this state, people no longer “make history as they please”, but merely hope to adjust its course – if at all19.

In economics, the ‘atom’ of production from which people are alienated is the commodity; in politics, it is the decision. Historical alienation implies a similar loss – estrangement from the production of ‘atoms’ of historical change: events. Yet all events are different and unequally susceptible to alienation.

While a full ontology of historical events20 lies beyond this article’s scope, I define them as events that shape human history and enter its narrative. Previously, I likened them to products of deliberate collective action. But many events are unintended or non-human in origin and relate differently to alienation.

To clarify this, I propose a heuristic classification – ideal types (Weber 1949, 90), not ontological categories (most real events fall on the spectrum between them):

1) Deliberate events: consciously planned and executed, aimed at redirecting history. Analogous to manufactured goods.

2) Unintentional events: unintended outcomes of human action. Chakrabarty (2009, 210, 221) frames climate change this way, though others see it as a product of deliberate economic decisions (Bonneuil and Fressoz 2016). Other examples include Mao’s sparrow campaign famine or the Chornobyl disaster.

3) Non-artificial events: natural occurrences not caused by humans but historically significant – volcanic eruptions, pandemics, the sudden death of a leader.

The typology clarifies how alienation distorts interpretation. Even carefully orchestrated events, for example, a war, may be viewed as an outcome of faceless geopolitical forces. Such misreadings flatten narratives, erasing the visibility of human agency. Deliberate acts may appear accidental; unintended consequences are seen as natural – this cognitive downgrading of human agency reinforces fatalism. Beck notes that modern catastrophes are often understood only in hindsight – by which point they seem ‘inevitable’ (Beck 1992, 33–34). Even deliberately engineered developments may seem impersonal to those detached from their origins, echoing the resignation described by Slothuus (2025, 42–43), where agency feels unreachable.

Deliberate events offer the clearest case for analyzing historical alienation, as they resemble consciously produced outcomes. Using the structure of economic alienation, I can model the dynamics here. In a non-alienated condition, individuals recognize their role in shaping history. They see themselves as active participants in historical events, aware of the collective agency shared with others. This recognition also makes them more likely to interpret historical developments as the result of conscious human effort, and to imagine which outcomes are still possible if the collective will aligns.

By contrast, an alienated individual, lacking belief in their capacity to influence the present, fails to perceive their participation in ongoing historical processes. The idea that one could deliberately shape history – even collectively – becomes implausible. As a result, deliberate events are increasingly misread as unintentional or natural. This perception weakens both the motivation and the perceived feasibility of historical change.

Perceptions of unintentional events are shaped by how people understand deliberate ones. In a non-alienated state, individuals acknowledge humanity’s historical agency and tend to trace even unexpected outcomes back to human decisions or errors – depending on their knowledge.

Under historical alienation, however, people underestimate agency and become less attuned to historical processes (Beck 1992, 22–27)21. A large enough unintentional event may seem ‘too big’ for humans to ever cause, and thus non-artificial (Beck 1992, 19). This makes it harder, for example, to believe that climate change stems from human activity, which appears negligible compared to vast natural forces.

Some may accept that climate change is anthropogenic but still misattribute its origins22 – viewing it as a gradual consequence of millennia of human existence rather than a result of recent industrial development (Broswimmer 2002, 4–6). In this view, unintended outcomes appear as inevitable byproducts of life, to be endured rather than addressed (Beck 1992, 33, 41, 80)23.

Although non-artificial events are not caused by humans, historical alienation can still distort their perception. Man-made events like climate change may be misclassified as natural, while alienation also affects how people assess the severity, historical relevance, and controllability of such events.

In a non-alienated context, individuals better grasp the scope of human agency and can more clearly evaluate responses to natural events. But if an alienated person underestimates the scope of human agency, such events appear as overwhelming, external forces – disasters from ‘outside’ history24, which humanity cannot avoid or successfully mitigate25. The COVID-19 pandemic illustrates this: although it posed no existential threat and was manageable, many experienced it as apocalyptic, and few accepted major countermeasures (Žižek 2020, 110–111).

Conversely, others downplay the impact of such events. If humans are viewed as historically powerless and disasters are perceived as recurring facts of life, one might reason that if such threats were truly catastrophic, humanity would already be extinct. Since past plagues were endured with little intervention, current action seems unnecessary. Even catastrophes become normalized (Debord 1998, 13). Žižek (2020, 51) captures this fatalism: “Humanity has survived much worse plagues – why bother?”

Having examined how alienation distorts perceptions of event types – and shaped public responses to climate change and COVID-19 – I now turn to its broader temporal effects: how alienation reshapes our perception of history and time, contributing to what is often called presentism.

Alienation distorts the perception of history by undermining belief in human agency. History appears less a product of collective action and more the outcome of impersonal forces (Simon 2018, 117). The status quo then feels immovable, and change is implausible (Marcuse 2007, 149–150; Fisher 2009, 59). When systems like the market26 are viewed as holding historical power, current conditions seem inevitable (Brown 2015, 67, 81), enclosing “the horizons of the thinkable” (Fisher 2009, 8).

This sense of stagnation marks what Hartog (2015, 16–18, 108–111, 200–203) calls presentism: history as an ‘endless present’ dictated by structural laws or natural forces. Alienation shapes how futures are imagined – either as total collapse or stasis. If agency seems too weak, crises like climate change appear apocalyptic and unthinkable (Simon 2018, 110–111)27; if manageable, they still fail to disrupt the status quo.

Such conditions make meaningful change seem implausible (Simon 2018, 113), echoing Jameson and Fisher’s paradox: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism” (Jameson 2003, 76). Even outside capitalism, it may be easier to envision extinction than global coordination.

Gradual crises like climate change are particularly alienating. Their effects unfold imperceptibly – masked as local weather until a catastrophe erupts (WWF 2018, 7; Beck 1992, 33–34; Simon 2018, 120; Hellerma 2020, 13; Timofeeva 2014). If disruption does not fully overturn the system, it feels more like a temporal gap than real historical rupture – much like the pandemic experience.

Historical alienation, grounded in economic and political estrangement, thus shapes not only event perception but how people relate to history itself. It fosters apocalyptic fatalism, civic withdrawal, and denial of human impact. Yet alienation is not invincible. Critical reflection can expose its mechanisms (Cohen 1972, 200–201). Social movements and revolutions show that agency can be reclaimed. Still, for many, history remains something that happens to them – sustained by entrenched political and economic structures.

This article explored why people often perceive human-made historical events as alien or uncontrollable. Drawing on Marx’s theory of alienation, it applied that logic to the ‘production’ of history, arguing that economic and political estrangement fosters a sense of powerlessness. As democratic participation declines, political life comes to resemble alienated labor – disconnected from outcomes and devoid of agency. These forms of alienation undermine belief in collective capacity, reinforcing presentism and making crises like climate change appear inevitable.

This framework clarifies widespread historical apathy and fatalism while suggesting that deeper democratic engagement could restore agency. As Puusalu (2019, 2) notes, in a digitally connected world, individuals may be ‘overconnected’ but ‘under-engaged’, exacerbating rather than alleviating alienation. Without tangible avenues for action, online participation can reinforce feelings of futility.

By integrating Marxist theory with present-day crises, the article contributes to political philosophy and the philosophy of history. It reframes democratic disengagement as political alienation, extends this concept into the historical domain, and links both to growing disconnection. Cases such as climate inaction and civic withdrawal underscore the urgency of reviving collective agency.

Distinguishing between economic, political, and historical alienation reveals how human agency is undermined across different spheres. Understanding these layers also points to remedies: expanding meaningful democratic participation may help counter passivity. While ideology and belief shape perceptions of agency, confronting alienation remains essential. If alienation constrains imagination and impedes action, its reduction is a critical step toward addressing today’s crises.

AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, 2022. More Americans are pessimistic about the impact they can have on climate change compared to three years ago. [online]. Available at: https://apnorc.org/projects/more-americans-are-pessimistic-about-the-impact-they-can-have-on-climate-change-compared-to-three-years-ago/ [Accessed 21 Apr. 2024].

Aviva, 2023. Over-65s top poll of climate-conscious behaviours. [online] www.aviva.com. Available at: https://www.aviva.com/newsroom/news-releases/2023/10/over-65s-top-poll-of-climate-conscious-behaviours/. [Accessed 21 Apr 2024].

Beardsworth, J., 2022. We Don’t Need War: Shock, Anger and Defiance on Moscow’s Streets as Russia Invades Ukraine. [online] The Moscow Times. Available at: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2022/02/24/we-dont-need-war-shock-anger-and-defiance-on-moscows-streets-as-russia-invades-ukraine-a76574. [Accessed 21 Apr. 2024].

Beck, U., 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: SAGE Publications.

Bell, J., Poushter, J., Fagan, M. and Huang, C., 2021. Climate Change Concerns Make Many Around the World Willing to Alter How They Live and Work. [online]. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/09/14/in-response-to-climate-change-citizens-in-advanced-economies-are-willing-to-alter-how-they-live-and-work/. [Accessed 21 Apr. 2024].

Blauner, R., 1964. Alienation and Freedom: The Factory Worker and His Industry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bonneuil, C. and Fressoz, J.B., 2016. The shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us. London: Verso Books.

Broswimmer, F., 2002. Ecocide: A Short History of the Mass Extinction of Species. London: Pluto Press.

Brown, W., 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books.

Chakrabarty, D., 2009. The Climate of History: Four Theses. Critical Inquiry 35(2): 197–222. https://doi.org/10.1086/596640

Chakrabarty, D., 2021. The Climate of History in a Planetary Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cohen, G. A., 1972. Karl Marx and the Withering Away of Social Science. Philosophy & Public Affairs 1(2): 182–203. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2264970.pdf

Cohen, G. A., 1978. Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Collingwood, R. G., 1946. The Idea of History. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Debord, G., 1998. Comments on the Society of the Spectacle. New York: Verso.

Fisher, M., 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?. Winchester: Zero Books.

Hartog, F., 2015. Regimes Of Historicity: Presentism And Experiences Of Time. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hellerma, J., 2020. History on the Move: Reimagining Historical Change and the (Im)possibility of Utopia in the 21st Century. Journal of the Philosophy of History 15(2): 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1163/18722636-12341442

Jaeggi, R., 2014. Alienation. New York: Columbia University Press.

Jameson, F., 2003. Future City. New Left Review 21: 65–79. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii21/articles/fredric-jameson-future-city

Kandiyali, J., 2020. The Importance of Others: Marx on Unalienated Production. Ethics 130(4): 555–587. https://doi.org/10.1086/708536

Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C.-Y. and Leiserowitz, A., 2015. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change 5: 1014–1020. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2728

Lenton, T. M. et al., 2019. Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against. Nature 575(7784): 592–595. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-03595-0

Marcuse, H., 2007. One-Dimensional Man. New York: Routledge Classics.

Marlon, J., Neyens, L., Jefferson, M., Howe, P., Mildenberger, M. and Leiserowitz, A., 2024. Yale Climate Opinion Maps 2023 - Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. [online] Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Available at: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us/. [Accessed 21 Apr. 2024].

Marx, K. and Engels, F., 1978. The Marx-Engels Reader. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Moore, J. W., 2017. The Capitalocene, Part I: on the nature and origins of our ecological crisis. The Journal of Peasant Studies 44(3): 594–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1235036

Norgaard, K. M., 2011. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ollman, B., 1971. Alienation: Marx’s Conception of Man in Capitalist Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Øversveen, E., 2022. Capitalism and alienation: Towards a Marxist theory of alienation for the twenty-first century. European Journal of Social Theory 25(3): 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310211021579

Pateman, C., 1970. Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Puusalu, J., 2019. Overconnected, under-engaged: When Alienation Goes Online. PhD dissertation, University of Exeter. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10871/37249

Seeman, M., 1959. On The Meaning of Alienation. American Sociological Review 24(6): 783–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/2088565

Simon, Z. B., 2018. (The impossibility of) acting upon a story that we can believe. Rethinking History 22(1): 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2017.1419445

Slothuus, L., 2025. Political fatalism and the (im)possibility of social transformation. Contemporary Political Theory 24: 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-024-00685-1

Steffen, W. et al., 2018. Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115(33): 8252–8259. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1810141115

Timofeeva, O., 2012. The End of the World: from Apocalypse to the End of History and Back. E-flux Journal 56: 29–38. https://editor.e-flux-systems.com/files/60324_e-flux-journal-issue-56.pdf

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) and University of Oxford, 2021. Peoples’ Climate Vote 2021 [online]. New York: UNDP. Available at: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2021-10/UNDP-G20-Peoples-Climate-Vote-2021-V2.pdf. [Accessed 21 Apr. 2024].

Weber, M., 1949. The Methodology of the Social Sciences. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

White, H. V., 2014. Metahistory: the historical imagination in nineteenth century Europe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature), 2018. Living Planet Report - 2018: Aiming Higher [online]. Grooten, M. and Almond, R.E.A.(Eds). Switzerland: Gland WWF. Available at: https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-10/LPR2018_Full%20Report.pdf. [Accessed 21 Apr. 2024].

Žižek, S., 2020. Pandemic!: COVID-19 shakes the world. New York: Polity Press.

1 Crutzen, Paul J., Stoermer, Eugene F., The “Anthropocene”. IGBP Newsletter, 2000.

2 Chakrabarty’s ideas are explained in more detail in his more recent monograph, The Climate of History in a Planetary Age (2021). However, his main ideas remained the same as in the quoted article. Since the article represents them more densely, I mostly refer to it for the sake of the reader’s convenience.

3 Also, around two-thirds of the world’s population recognize climate change as an urgent threat (UNDP 2021, 7).

4 AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research (August 2022).

5 And it is unclear whether the Russian Government, who started the war, sees a way to end it and feels control over it.

6 In Attempt at a Critique of All Revelation (1792).

7 The Essence of Christianity (1841).

8 Examples: 1) The worker is alienated from the produced goods, but clearly understands his role in this process, without succumbing to commodity fetishism. 2) He has control over the fruits of his labor (self-employed), but his perception of labor is affected by commodity fetishism.

9 “For in the first place labor, life-activity, productive life itself, appears to man merely as a means of satisfying a need <…> yet the productive life is the life of the species” (Marx 1978, 75–76).

10 “The worker puts his life into the object; but now his life no longer belongs to him” (Marx 1978, 72).

11 Especially taking into account that Marx considered all social relations to be productive relations (ibid., 4, 261).

12 “Within the relationship of estranged labor, each man views the other in accordance with the standard and the position in which he finds himself as a worker” (ibid., 77)

13 “It is just in the working-up of the objective world, therefore, that man first really proves himself to be a species being. This production is his active species life. Through and because of this production, nature appears as his work and his reality. The object of labor is, therefore, the objectification of man’s species life: for he duplicates himself not only, as in consciousness, intellectually, but also actively, in reality, and therefore he contemplates himself in a world that he has created” (ibid., 76).

14 There are doubts that productive relations can be totally transparent (Cohen 1972, 183).

15 Similar to the mode of perceiving ‘history as tragedy’ (White 2014, 64–65) which Hayden White has connected to liberalism dealing with big data and slow social processes (ibid., 59–62).

16 States are “subordinated to the market, govern for the market, and gain or lose legitimacy according to the market’s vicissitudes; states also are caught in the parting ways of capital’s drive for accumulation and the imperative of national economic growth” (ibid., 108).

17 “The figuration of human beings as human capitals eliminates the basis of a democratic citizenry, namely a demos concerned with and asserting its political sovereignty” (Ibid., 65).

18 Sometimes people change politics and economy without an intent to make history; this intent may be separate.

19 “It has become difficult to tell stories in order to facilitate desired future outcomes, regardless of the grandiosity of the stories” (Simon 2018, 111)

20 Works on this question are numerous. For example: Badiou, Alain, Philosophy and the Event (2013); Badiou, Alain, Being and Event (2005); Braudel, Fernand, On History (1980); Collingwood, Robin G., The Idea of History (1956); Heidegger, Martin, The Event (1936–1944); Ricoeur, Paul, Time and Narrative, Volumes I & III (1984, 1988); Simon, Zoltán Boldizsár, The Epochal Event: Transformations in the Entangled Human, Technological, and Natural Worlds (2020); Tamm, Marek (ed.), Afterlife of Events: Perspectives on Mnemohistory (2015); Wagner-Pacifici, Robin, What Is an Event? (2017); Žižek, Slavoj, Event (2014).

21 In Risk Society (1992), Beck reflects on how uneasy it is to know what unintended consequences of human activity are being produced and what, overall, this activity is, focusing on techno-industrial risks.

22 For instance, they may attribute historical agency to something in favor of which human agency seems to be alienated – like abstract ‘capitalism’ (Moore 2017, 3).

23 “One acts physically, without acting morally or politically. The generalized other – the system – acts within and through oneself” (ibid., 33)

24 “Future vision of unprecedented change simply defies story form” as it “cannot simply be conceived of as gradually developing from preceding states of affairs” (Simon 2018, 113).

25 “The motivation for action no longer derives from a desired best outcome. Societal action today aims at avoiding the worst prospects of unprecedented change, which are characteristically dystopian and apocalyptic” (Simon 2018, 110).

26 And thus is alienated in favor of this ‘something’.

27 “What remains are stories that end in the present and are told from a present point of view” (ibid., 111)