Psichologija ISSN 1392-0359 eISSN 2345-0061

2020, vol. 62, pp. 56–68 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Psichol.2020.21

Eight Forms of Abuse: The Validation and Reliability of Two Multidimensional Instruments of Intimate Partner Violence

Zuzana VasiliauskaitėMykolas Romeris University

zuzana.vasiliauskaite@gmail.com

Robert Geffner

Institute on Violence, Abuse and Trauma;

California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant International University

bgeffner@alliant.edu

Summary. Many researchers are still relying on older and more rigid instruments focusing mostly on the physical aspect of intimate partner violence (IPV). This way multidimensionality of IPV and complex experiences of IPV survivors’ are overlooked by many researchers, practitioners and decision-makers. Therefore, our study aimed to adopt to Lithuanian two multidimensional scales: the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) and the Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA). As well as confirm its validity and reliability for the use for determining the experiences of Lithuanian women in intimate partner relationships. Through various channels 311 women, survivors of IPV were recruited. The structure of both measurements was validated using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and internal consistency using McDonald’s omega coefficient. Relying on the newest research we confirmed a five-factor structure for the CAS with the five factors being: Severe Combined Abuse, Sexual Abuse, Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, and Harassment. We also confirmed the three-factor structure for the SEA, resulting in Economic Control, Economic Exploitation, and Employment Sabotage. The instruments demonstrated high internal consistency. The validated instruments that measure multidimensionality of IPV will allow a more comprehensive data and knowledge collection of women’s experiences in abusive relationships.

Keywords: composite abuse scale, domestic violence, scale of economic abuse, Lithuania, battered women.

Aštuonios smurto formos: dviejų daugiadimensių skalių, vertinančių smurto prieš moteris šeimoje patirtį, validumas ir vidinis suderinamumas

Santrauka. Dauguma tyrėjų, besigilinančių į smurto prieš moteris šeimoje problemą, naudoja senus bei rigidiškus įrankius, iš esmės skirtus vertinti fizinio smurto patirtį, ignoruojant kitas plačiai paplitusias smurto formas ar joms skiriant nepakankamai dėmesio. Taigi įvairios išgyventos patirtys ir smurto prieš moteris šeimoje problemos įvairiapusiškumas nėra atskleidžiami bei atpažįstami ir dėl to nesulaukia tinkamo tyrėjų, praktikų bei sprendimų priėmėjų dėmesio. Šiuo tyrimu buvo siekiama į lietuvių kalbą išversti ir adaptuoti dvi daugiadimenses skales: Sudėtinę smurto skalę (SSS, angl. Composit Abuse Scale) ir Ekonominio išnaudojimo skalę (EIS, angl. Scale of Economic Abuse). Taip pat siekta patvirtinti šių skalių validumą ir patikimumą, nustatant Lietuvos moterų patirtį artimuose santykiuose. Tyrime dalyvavo 311 intymaus partnerio smurtą patyrusių moterų. Abiejų skalių struktūra buvo patvirtinta taikant patvirtinamąją faktorinę analizę, o vidinis suderinamumas – naudojant McDonaldo omega koeficientą. Remiantis naujausiais tyrimais, buvo patvirtinta penkių faktorių SSS struktūra, susidedanti iš penkių subskalių: žiauraus įvairių rūšių smurto, seksualinio smurto, emocinio smurto, fizinio smurto ir priekabiavimo. Taip pat patvirtinta trijų faktorių EIS struktūra – ekonominės kontrolės, ekonomino išnaudojimo ir karjeros sabotavimo. Abi skalės pasižymėjo geru vidiniu suderinamumu. Adaptuotos ir validizuotos skalės, kuriomis matuojama įvairiapusė smurto prieš moteris šeimoje patirtis, leis surinkti išsamesnius duomenis, geriau atspindėti įvairias moterų patirtis smurtiniuose santykiuose ir atitinkamai praplėsti problemos nagrinėjimą bei sprendimo būdų pasirinkimą akademiniu, praktiniu bei politiniu lygiu.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: sudėtinė smurto skalė, smurtas šeimoje, ekonominis smurtas, Lietuva, smurtas prieš moteris.

Received: 7/5/2020. Accepted: 2/12/2020

Copyright © 2020 Zuzana Vasiliauskaitė, Robert Geffner. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

International data reveal that one in three women worldwide at some point of their lives have experienced physical or sexual violence perpetrated by men they knew closely, mostly intimate partners (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), 2014; Smith et al., 2018; World Health Organization (WHO), 2013). Moreover, the prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) increases dramatically when all forms of IPV are taken into account, such as psychological and economic abuse, and not just physical abuse. For the purposes of this study, IPV is understood as violence or abuse against the current or previous romantic partner or spouse. For the purposes of this study, we are only focusing on male IPV against a female partner or spouse.

IPV is a multidimensional phenomenon, and there are many different forms of IPV identified. However, a lack of consistent definitions impedes the way IPV is researched, recorded and measured (FRA, 2014; Howarth & Feder, 2013). Most research data reflect the prevalence of physical and sexual violence against women, leaving other forms of IPV such as psychological, economic violence, harassment and stalking, coercive control and social isolation less presented, explored. One of the reasons this continue to happen is a lack of validated measures covering all forms of violence. The most used scales, such as Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979; 1990a), Measure of Wife Abuse (Rodenberg & Fantuzzo, 1993), Index of Spousal Abuse (Hudson & McIntosh, 1981), Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (Tolman, 1989), usually focus on episodic male violence or just on one or two particular forms of violence and abuse. Through the use of such instruments, as discussed in more detail below, only a few aspects of IPV survivors’ experience are revealed and examined.

One of the newest measurements of IPV is the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) (Hegarty et al., 2005; Hegarty & Valpied, 2007), which was created by integrating the best qualities of the above-mentioned scales. The CAS demonstrates strong psychometric properties and has been translated, adapted and used in several countries across the globe with various populations (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2016; Lokhmatkina et al., 2010; Loxton et al., 2013; Rietveld et al., 2010).

Regardless of the development of newer and more encompassing measurements of various forms of IPV, many researchers are still relying on older instruments. The same tendency is observed in Lithuanian research in the field of IPV. Most used scale to determine women’s experience of IPV appears to be Conflict Tactic Scale (Kamimura et al., 2017; Tamutiene et al., 2013; Žukauskienė et al., 2014). However, this scale neglects the context, nature and meaning underlying each abusive incident (Hegarty & Valpied, 2007). Most of the researchers cherry-pick questions from existing measurements (Žukauskienė et al., 2019) or create their own questionnaires without reporting about the validity or reliability of the measurement (Grigaitė et al., 2019; Tureikytė et al., 2008). Then less informed researchers use those unvalidated measurements still without performing validity or factor structure analysis (Bakaitytė, 2019). However, there are studies that do not mention any scales, questionnaires, inventories, neither self-created nor validated (Joffe & Buksnyte-Marmiene, 2014; Stonienė et al., 2013). As the interest of IPV increased after the criminalisation of IPV in Lithuania in 2011, we saw a real need for translated and validated instruments that allow for more comprehensive data and knowledge collection of women’s experiences in abusive relationships.

For better reflection of IPV multidimensionality, we decided to adopt two scales: the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) and the Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA). Two of these measurements were chosen due to their multidimensionality. The CAS encompasses four forms of IPV: (1) severe combined abuse with questions about sexual abuse, (2) emotional abuse, (3) physical abuse, and (4) harassment. The SEA is one of the first validated instruments designed to measure economic violence and abused women experience in intimate partner relationships (Adams et al., 2015). Therefore, the study‘s objectives were to translate and adapt to Lithuanian two scales of the CAS and the SEA that reflect the multidimensionality of IPV and perform measurements’ validity and reliability analysis.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants. Four hundred forty women completed the questionnaire, though 33 did not fill it beyond socio-demographic data because they had never had a male intimate partner (N = 28) or for other undisclosed reason (N = 5). Out of 407 women, 311 (77.4%) had experienced at least one episode of IPV indicated on one of the scales that was perpetrated by a current or previous intimate partner at any time of their adult lives. Further calculations were based on the analysis of these 311 participants. The study sample is not random and is, therefore, considered convenient. The participants’ age ranged from 18 to 71 years old (M = 35.7; SD = 11.8). The majority of women had higher education (66.1%), than vocational (16.1%) and secondary (17.7%). The majority (63.5%) of women were also employed, studying (12.8%), or in some cases, studying and working (11.2%), and 12.5% neither employed nor studying. More than half of participants (59%) lived in cities, 25.8% in towns and 15.2% in small towns. Most women were at the time married (34%) or involved in intimate relationships (but not cohabiting – 28.2%), 19.7% not married, but cohabiting with their intimate partners and 18.1% of the women were single, therefore, not involved in the relationship at the time of the study.

Procedures. The data collection was carried out in 2016–2018 in several major cities of Lithuania and their districts. As the goal of the research was to translate the CAS and the SEA to Lithuanian and analyse their validity as well as reliability, various strategies for data collection were employed: (1) collecting paper questionnaires through Specialized Help Centres (SHCs) providing help and assistance to IPV survivors, (2) interviewing university students, (3) professionals from various institutions, and (4) distributing electronic questionnaires on social media. This research was conducted in accordance with national and international research ethics standards. Informed consent was obtained, considering that by filling in the survey, participants gave their consent to participate. They were informed verbally and in writing about the aims of the study and that the data will be used only for statistical purposes. Furthermore, no personal, identifiable data were collected, and the participants were informed and assured of anonymity and confidentiality.

Measures

The The study’s data were collected by employing psychometric self-report questionnaires, having requested/acquired the necessary permissions. All the questionnaires were translated from English to Lithuanian by three independent experts with a psychological background, work experience with intimate partner violence survivors and excellent knowledge of English. The translations were compared with each other, and by consensus, the most relevant statements were selected. Then the scales were back-translated to English by a professional interpreter who also has training in psychology. The results were again reviewed by the first team together with the interpreter, and final edits based on the collective agreement were made.

The Composite Abuse Scale (CAS). The Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) is a self-report measure that asks women to identify the frequency of abuse they suffered by a current or previous intimate partner (Hegarty et al., 2005; Hegarty et al., 1999; Hegarty & Valpied, 2007). Thirty items comprise four subscales: Severe Combined Abuse (eight items describing incidents of severe combined violence such as sexual violence, assault with a weapon, being locked in the bedroom, kept from obtaining medical care); Emotional Abuse (11 items, which include verbal and psychological violence, insults, isolation from friends and family); Physical Abuse (seven items include being hit, slapped, thrown, pushed, etc.); and Harassment (four items describing harassment at work or over the telephone, as well as being followed). For the exact statements and the descriptive statistics, please see Table 1. Answers were measured in a 6-point scale from 0 to 5, where 0 meant “never,” 5 – “daily,” as well as other answer options such as 8 – “does not apply” (e.g., when asked about the car and the woman does not own one) and 9 – “would prefer not to answer.” Answers that were checked 8 were counted as 0 and those marked 9 – as missing. Scale scores can range from 0 to 150, the higher the score, the more severe and frequent abuse was suffered.

The Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA). The SEA measures economic abuse frequency in 5-point scale with answers ranging from 0 – “Never” to 4 – “Quite Often” (Adams, Beeble, & Gregory, 2015; Adams, Sullivan, Bybee, & Greeson, 2008). The SEA is comprised of two subscales: (a) the Economic Control – 17 items describing abusers’ tendency to restrict the women from freely accessing resources they have in their lives ( e.g., Make you ask him for money; Kept financial information from you); and (b) the Economic Exploitation subscale – 11 items reflecting abusers’ actions resulting in depletion of their own or shared funds (e.g., Refused to get a job, so you had to support your family alone; Gambled with your money or your shared money), or creating a debt under the woman’s name or ruining her credit (e.g., Paying bills late or not paying bills that were in your name or both of your names). For the exact statements and descriptive statistics, please see Table 2.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

The psychometric properties of all study instruments were verified by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). CFA model parameters were calculated using the weighted least squares means and a variance adjusted estimator (WLSMV) (Muthén, du Toit, & Spisic, 1997) in the statistical analysis programme Mplus 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2015). The WLSMV is more suitable for variables that are considered more categorical or ordered with a non-normal distribution (Brown, 2015). The model fit to the data was checked based on the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) together with the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and RMSEA 90% confidence intervals, which should not exceed 0.1 (Kline, 2016). Chi-square (χ2) statistics are provided, but will not be used to evaluate the model fit to the data due to its high sensitivity to sample size (Brown, 2015; Kelloway, 2015).

CFI and TLI ≥ 0.90 indicate adequate model fit to the data, and values above 0.95 indicate good model fit. Correspondingly, RMSEA ≤ 0.08 indicates adequate model fit to the data, and value ≤ 0.05 indicates a good model fit (Brown, 2015; Kline, 2016). In cases where the value of any of these indicators was lower than acceptable, the model was named poorly fitting and revised.

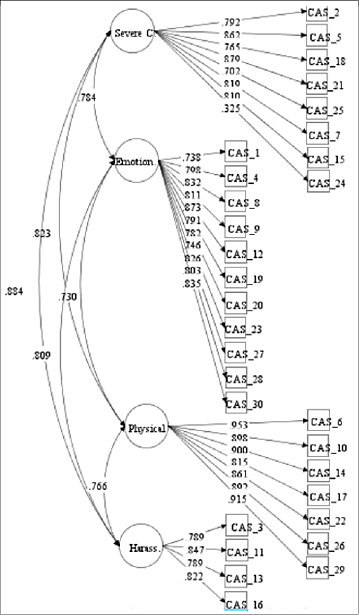

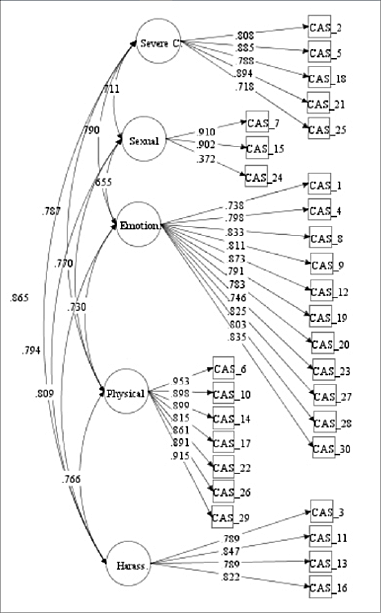

CFA of the Composite Abuse Scale: Original four-factor structure vs new five-factor structure. We conducted CFA to test if CAS scale’s factor structure provided by Hegarty et al. (2005) fit to our data and found an adequate model fit – χ2 (399) = 829.52, p = .001, CFI = 0.979, TLI = 0.977, RMSEA = 0.059; RMSEA 90% CI [0.053–0.065] (See Figure 1). However, since in many other studies, items reflecting sexual violence were considered as a separate factor (Ford-Gilboe et al., 2016) or as stand-alone questions (Loxton et al., 2013), it was felt that both theoretically and practically it was important to have sexual violence as a separate factor. Therefore, the five-factor model that fit the data was checked where the first CAS factor, ‘Severe combined abuse,’ was divided into two factors: ‘Severe combined abuse’ and ‘Sexual violence.’ The CFA of this new model fit the data better than the original one – χ2 (395) = 798.46, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.980, TLI = 0.978, RMSEA = 0.057; RMSEA 90% CI [0.052–0.063]. Therefore, we confirmed a five-factor structure for the CAS with the five factors being: Severe Combined Abuse, Sexual Abuse, Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, and Harassment (See Figure 2). The new five-factor model fitted the data well. Moreover, as we used the WLSMV estimator, two models were compared by using the Chi-square test of differences testing. For testing procedures see Muthén and Muthén (1998–2017). The results indicated that the Chi-square difference was significant (χ2 (4) = 29.98; p < .001) meaning that the first model that had fewer parameters has a significantly worse model fit. Therefore, we retained the more parsimonious model (i.e. the five-factor model).

Figure 1. The CSA original four-factor structure and factor loadings

Note. Severe C. – Severe Combined Abuse; Emotion. – Emotional abuse; Harass. –Harassment.

Figure 2. The CSA new five-factor structureand factor loadings

Note. Severe C. – Severe Combined Abuse; Emotion. – Emotional abuse; Harass. – Harassment.

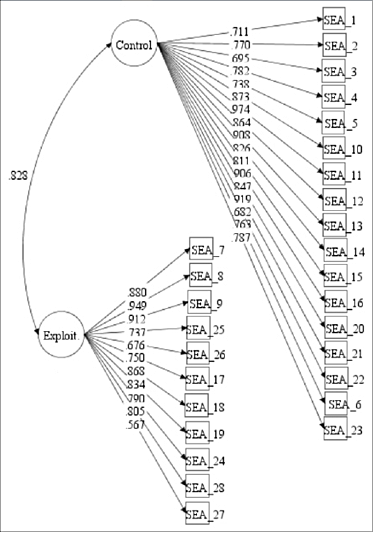

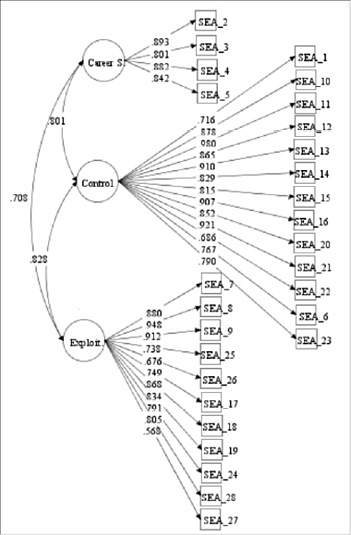

CFA of the Scale of Economic Abuse: Original two-factor structure vs new three-factor structure. CFA was conducted for SEA original factor structure provided by Adams et al. (2008) to test whether the model fits our data. The model was adequately fitted – χ2 (349) = 926.08, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.073; RMSEA 90% CI [0.067–0.079] (See Figure 3). However, expecting a better fit we followed the revised model proposed by Postmus et al. (2016), and extracted the third factor, employment sabotage. Even though revisions were made with a reduced number of items in the factor, the three-factor model fitted to the data was better than original and was accepted – χ2 (347) = 874.29, p = 0.001, CFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.962, RMSEA = 0.070; RMSEA 90% CI [0.064–0.076]. As we also used WLSMV estimator, two models were compared by using the Chi-square test of differences testing. The results indicated that the Chi-square difference was significant (χ2 (2) = 36.85; p < .001) meaning that the first model that had fewer parameters has a significantly worse model fit. Hence, we retained more parsimonious model (i.e., the three-factor structure; see Figure 4), resulting in factors: Economic Control, Economic Exploitation, and Employment Sabotage (four items suggesting abusers’ efforts to restrict women from obtaining their own resources through employment).

Figure 3. The SEA original two-factor structure and factor loadings

Note. Control – Economic Control, Exploit. – Economic Exploitation.

Figure 4. The SEA new three-factor structure and factor loadings

Note. Career S. – Career Sabotage, Control – Economic Control, Exploit. – Economic Exploitation.

Internal consistency

McDonald’s omega (ω) coefficient (McDonald, 1978), which is considered more advanced than Cronbach’s α (Cho & Kim, 2015) and is more appropriate for the multidimensional data, was used to assess the internal consistency of the scales. The McDonald’s ω and Cronbach’s α values are interpreted in the same way (Geldhof et al., 2014). In any case, we included both Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω. JASP 0.11.1 program was used for calculating the instrument’s reliability. All subscales demonstrated high internal reliability (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and reliability for Composite Abuse Scale

|

Type of abuse |

Abusive behaviour |

Mean |

S. D. |

Skew. |

Kurt. |

|

Severe Abuse |

Kept me from medical care. |

0.32 |

0.90 |

3.51 |

13.50 |

|

Locked me in the bedroom. |

0.25 |

0.84 |

4.04 |

17.65 |

|

|

Used a knife or gun or other weapons. |

0.24 |

0.72 |

3.74 |

16.31 |

|

|

Took my wallet and left me stranded. |

0.28 |

0.76 |

3.06 |

9.87 |

|

|

Refused to let me work outside the home. |

0.32 |

0.94 |

3.40 |

11.81 |

|

|

Sexual Abuse |

Raped me. |

0.32 |

0.84 |

3.31 |

12.75 |

|

Tried to rape me. |

0.38 |

0.89 |

2.72 |

8.30 |

|

|

Put foreign objects in my vagina/anus. |

0.09 |

0.47 |

6.28 |

48.58 |

|

|

Emotional Abuse |

Told me that I wasn’t good enough. |

1.95 |

1.66 |

0.40 |

–1.04 |

|

Tried to turn my family, friends and children against me. |

1.15 |

1.54 |

1.15 |

0.21 |

|

|

Told me that I was ugly. |

1.16 |

1.47 |

1.07 |

0.12 |

|

|

Tried to keep me from seeing or talking to my family. |

0.71 |

1.27 |

1.92 |

3.07 |

|

|

Blamed me for causing their violent behaviour. |

1.24 |

1.62 |

1.09 |

0.00 |

|

|

Told me that I was crazy. |

1.31 |

1.52 |

1.02 |

0.15 |

|

|

Told me that no one else would want me. |

1.08 |

1.55 |

1.23 |

0.31 |

|

|

Did not let me socialise with my female friends. |

0.84 |

1.35 |

1.68 |

2.05 |

|

|

Tried to convince my friends, family or children that I was crazy. |

0.69 |

1.21 |

1.86 |

3.02 |

|

|

Told me that I was stupid. |

1.33 |

1.56 |

0.98 |

–0.09 |

|

|

Became upset if dinner/housework wasn’t done when they thought it should be. |

1.16 |

1.20 |

0.75 |

–0.18 |

|

|

Physical Abuse |

Slapped me. |

0.54 |

1.00 |

2.03 |

4.19 |

|

Threw me. |

0.62 |

1.03 |

1.72 |

2.84 |

|

|

Shook me. |

0.73 |

1.16 |

1.67 |

2.52 |

|

|

Pushed, grabbed or shoved me. |

0.86 |

1.19 |

1.32 |

1.27 |

|

|

Hit or tried to hit me with something. |

0.56 |

1.01 |

1.94 |

3.83 |

|

|

Kicked me, bit me or hit me with a fist. |

0.48 |

0.91 |

2.00 |

3.93 |

|

|

Beat me up. |

0.44 |

0.94 |

2.49 |

6.71 |

|

|

Harassment |

Followed me. |

0.94 |

1.48 |

1.48 |

1.60 |

|

Hung around outside my house. |

0.60 |

1.15 |

1.93 |

3.12 |

|

|

Harassed me over the telephone. |

1.18 |

1.70 |

1.23 |

0.15 |

|

|

Harassed me at work. |

0.42 |

1.00 |

2.76 |

7.86 |

Note. a % – per cents, S. D. – Standard Deviation, Skew. – Skewness, Kurt. – Kurtosis.

b Reliability measured by McDonald’s ω and Cronbach’s α.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and reliability for Scale of Economic Abuse

|

Type of abuse |

Abusive behaviour |

Mean |

S. D. |

Skew. |

Kurt. |

|

Employment Sabotage |

Do things to keep you from going to your job. |

0.54 |

1.05 |

1.88 |

2.52 |

|

Beat you up if you said you needed to go to work. |

0.14 |

0.51 |

4.39 |

21.13 |

|

|

Threaten you to make you leave work. |

0.30 |

0.84 |

3.05 |

8.96 |

|

|

Demand that you quit your job. |

0.52 |

1.08 |

2.00 |

2.88 |

|

|

Economic |

Steal the car keys or take the car so you couldn’t go look for a job or go to a job interview. |

0.28 |

0.84 |

3.15 |

9.37 |

|

Make you ask him for money. |

0.80 |

1.30 |

1.41 |

0.60 |

|

|

Do things to keep you from having money of your own. |

0.70 |

1.24 |

1.63 |

1.36 |

|

|

Decide how you could spend money rather than letting you spend it how you saw fit. |

0.37 |

0.96 |

2.76 |

6.76 |

|

|

Take your paycheck, financial aid check, tax refund check, disability payment, or other support payments from you. |

1.33 |

1.37 |

0.62 |

–0.84 |

|

|

Demand to know how money was spent. |

1.20 |

1.36 |

0.73 |

–0.78 |

|

|

Demand that you give him receipts and/or change when you spent money. |

0.61 |

1.12 |

1.79 |

2.09 |

|

|

Keep you from having the money you needed to buy food, clothes, or other necessities. |

0.82 |

1.28 |

1.42 |

0.74 |

|

|

Hide money so that you could not find it. |

1.43 |

1.49 |

0.57 |

–1.11 |

|

|

Keep you from having access to your bank accounts. |

0.25 |

0.78 |

3.52 |

12.09 |

|

|

Keep financial information from you. |

1.35 |

1.44 |

0.68 |

–0.91 |

|

|

Make important financial decisions without talking with you about it first. |

1.68 |

1.42 |

0.31 |

–1.18 |

|

|

Threaten you or beat you up for paying the bills or buying things that were needed. |

0.28 |

0.81 |

3.14 |

9.63 |

|

|

Economic (ω = 0.92; α = 0.91) |

Take money from your purse, wallet, or bank account without your permission and/or knowledge. |

0.45 |

0.98 |

2.28 |

4.47 |

|

Force you to give him money or let him use your chequebook, ATM card, or credit card. |

0.61 |

1.15 |

1.79 |

2.06 |

|

|

Steal your property. |

0.30 |

0.82 |

3.09 |

9.31 |

|

|

Gamble with your money or your shared money. |

0.26 |

0.77 |

3.28 |

10.76 |

|

|

Have you ask your family or friends for money but not let you pay them back |

0.32 |

0.86 |

2.89 |

7.74 |

|

|

Convince you to lend him money but not pay it back. |

0.54 |

0.99 |

1.84 |

2.54 |

|

|

Spend the money you needed for rent or other bills. |

0.45 |

0.90 |

2.22 |

4.63 |

|

|

Pay bills late or not pay bills that were in your name or in both of your names. |

0.67 |

1.12 |

1.67 |

1.86 |

|

|

|

Build up debt under your name by doing things like use your credit card or run up the phone bill. |

0.59 |

1.16 |

1.97 |

2.63 |

|

Refuse to get a job so you had to support your family alone. |

0.16 |

0.60 |

4.27 |

19.15 |

|

|

Pawn your property or your shared property. |

0.17 |

0.65 |

4.25 |

18.23 |

Note. a % – per cents, S. D. – Standard Deviation, Skew. – Skewness, Kurt. – Kurtosis.

b Reliability measured by McDonald’s ω and Cronbach’s α.

Discussion

The need for multidimensional instruments that help to reveal the complex experiences of women has been evident for several years, especially after the subject caught more people’s attention and interest following IPV criminalisation. This study attempted to translate to Lithuanian two multidimensional scales, analyse their validity and reliability while incorporating findings of original research as well as newer validation studies.

The original CAS has four dimensions: severe combined abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, harassment. A few later studies that looked at the factor structure of the CAS as well as our study found different factor structures than original study. Some of the studies reduced or reworded some items, which resulted in fewer factor structured measurements. Most of them did not confirm the severe combined abuse dimension. It is possible that due to the difficulty to conceptualise what exactly constitutes severe combined abuse, the dimension did not receive proper attention and effort to be deeper explored in prior studies. Loxton et al. (2013) aimed at adapting the CAS to measure IPV prevalence in a community. The items related to sexual abuse were condensed into one (e.g., Partner forced me to take part in unwanted sexual activity vs Tried to rape me), which resulted in the severe combined abuse scale no longer being evident, thus making a three-dimensional scale measuring physical abuse, emotional abuse, and harassment. Ford-Gilboe et al. (2016) study also found a three-factor structure; however, they extracted different dimensions than Loxton’s et al. (i.e., psychological, physical and sexual abuse). In comparison to the study by Loxton et al. (2013), Gilboe et al. (2016) did not condense sexual abuse items but reworded them (e.g., Tried to force me to have sex vs Tried to rape me). It is possible that different researchers’ approaches towards IPV as well as the cultural background had resulted in different outcomes. Informed by previously mentioned studies, our study confirmed the original factor structure with an additional factor: Sexual Abuse, resulting in a five-factor scale measuring Severe Combined Abuse, Sexual Abuse, Physical Abuse, Emotional Abuse and Harassment. Our study also confirmed good internal reliability. Previous studies have reported it to be high (Cronbach’s α > 0.85), while our study found McDonald’s ω ranging from 0.78 to 0.95 (Cronbach’s α – 0.73–0.95), which is just a bit lower, but still reflecting a strong internal consistency.

Historically economic abuse was seen as an extension of psychological abuse, and in many instruments, the questions reflecting economic abuse would be clustered together with the psychological abuse items. The first comprehensive questionnaire measuring economic abuse in intimate relationships was the Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA) (Adams et al., 2008). The scale has two dimensions: Economic Control, which reflects abusers’ tendency to restrict women from freely accessing resources, and Economic Exploitation, with items reflecting abusers’ actions resulting in the depletion of their own or shared funds. Even though the scale is relatively new, its validity and reliability were supported by several studies (Adams et al., 2008; Adams et al., 2015). However, Postmus et al. (2016) proposed a shorter version of the SEA (SEA-12) after the initial CFA of the two-factor model indicated a poor fit to the data. The SEA-12 consists of two original and one new factor: Employment Sabotage, which reflects abusers’ attempts to restrict women from obtaining their own resources through employment. In our study, we were able to confirm both two- and three-factor structures; however, the three-factor structure yielded a better model fit to the data. Moreover, our analysis showed a greater internal consistency of three subscales than previous studies did before (Cronbach’s α > 0.91 (Adams et al., 2008) and Cronbach’s α > 0.86 (Postmus et al. (2016)). Therefore, informed about previous studies, we confirmed that the Lithuanian version of SEA is a three-dimensional instrument with high internal reliability that reflects complex IPV survivors’ experiences related to economic abuse.

Previous studies reported a good construct validity of both scales. However, it would be beneficial to confirm this for the Lithuanian version as well. Therefore, future research could continue the validation analysis of both scales for the Lithuanian population. Additionally, attempts to reach a representative study would also be beneficial, as the current study’s sample was convenient, making the generalisation of the results to all survivors of IPV, female or male, cautioned. Notwithstanding the above, the findings are still meaningful and informative.

The Lithuanian versions of the CAS and the SEA showed good validity and reliability. These psychometrically robust measurements will allow for a more comprehensive understanding of women’s experiences in abusive relationships while focusing on more than just aspects of physical violence. These instruments determining the severity and frequency of eight different forms of intimate partner violence and abuse the Lithuanian women might be experiencing could be the first step to addressing the lack of continuity and comparability of the research on IPV carried out in Lithuania. Therefore, the instruments will have positive implications for researchers, practitioners, help-providers as well as law enforcement officers and other professionals coming into contact with female survivors of intimate partner violence in recognising different aspects of an abusive relationship.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our very great appreciation to all the women who participated in the study as well as all the Specialized Help Centres’ employees who helped to collect the data. We are particularly grateful for help, support and encouragement given by Vilnius Women’s House president L.H. Vasiliauskė, manager E. Zelionkaitė and specialized psychologist E. Dirmotaitė. Discussions with and advice given by dr. M. Naudi has been a great help in broadening an understanding of the phenomenon of violence against women and the role of this phenomenon’s researcher. Our grateful thanks are also extended to dr. R. Vosylis, dr. G. Kaniušonytė, dr. M. Poškus, and dr. I. Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė for their help in understanding the MPlus statistical analysis program.

References

Adams, A. E., Beeble, M. L., & Gregory, K. A. (2015). Evidence of the construct validity of the scale of economic abuse. Violence and Victims, 30 (3), 363–376.

Adams, A. E., Sullivan, C. M., Bybee, D., & Greeson, M. R. (2008). Development of the Scale of Economic Abuse. Violence against Women, 14 (5), 563–588.

Bakaitytė, A. (2019). Intymaus partnerio smurtą patyrusių moterų potrauminis augimas. Socialinis darbas, 17 (2), 209–225.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press.

Cho, E., & Kim, S. (2015). Cronbach’s coefficient alpha: Well known but poorly understood. Organizational Research Methods, 18 (2), 207–230.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA). (2014). Violence against women: An EU-wide survey–Main results. Luxembourg City, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-eu-wide-survey-main-results-report

Ford-Gilboe, M., Wathen, C. N., Varcoe, C., MacMillan, H. L., Scott-Storey, K., Mantler, T., …, Perrin, N. (2016). Development of a brief measure of intimate partner violence experiences: The Composite Abuse Scale (Revised)-Short Form (CASR-SF). BMJ Open, 6 (12), e012824. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012824

Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J., & Zyphur, M. J. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19 (1), 72–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0032138.

Grigaitė, U., Karalius, M., & Jankauskaitė, M. (2019). Between experience and social ‘norms’, identification and compliance: Economic and sexual intimate partner violence against women in Lithuania. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 3 (3), 303–321.

Hegarty, K., Bush, R., & Sheehan, M. (2005). The composite abuse scale: Further development and assessment of reliability and validity of a multidimensional partner abuse measure in clinical settings. Violence and Victims, 20 (5), 529–547.

Hegarty, K., Sheehan, M., & Schonfeld, C. (1999). A multidimensional definition of partner abuse: Development and preliminary validation of the Composite Abuse Scale. Journal of Family Violence, 14 (4), 399–415.

Hegarty, K., & Valpied, J. (2007). Composite abuse scale manual. Department of General Practice, University of Melbourne. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266041480_Composite_Abuse_Scale_Manual

Howarth, E., & Feder, G. (2013). Prevalence and Physical Health Impact of Domestic Violence. In L. Howard, G. Feder, R. Agnew-Davies (Eds.), Domestic Violence and Mental Health (p. 1–17). London, United Kingdom: Royal College of Psychiatrists publications.

Hudson., W., & McIntosh, S. (1981). The assessment of spouse abuse: Two quantifiable dimensions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 43 (4), 873–888.

Joffe, R., & Buksnyte-Marmiene, L. (2014). Abuse in adult intimate relationships in Lithuania and its influence on subjectively perceived health. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 159, 584–588.

Kamimura, A., Chernenko, A., Nourian, M. M., Assasnik, N., & Franchek-Roa, K. (2017). Factors associated with perpetration of physical intimate partner violence among college students: Russia and Lithuania. Deviant Behavior, 38 (2), 130–140. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2016.1196954

Kelloway, E. K. (2015). Using Mplus for structural equation modeling: A researcher’s guide. Second Edition. Sage Publications.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford publications.

Lokhmatkina, N. V., Kuznetsova, O. Y., & Feder, G. S. (2010). Prevalence and associations of partner abuse in women attending Russian general practice. Family Practice, 27 (6), 625–631. doi: https://doi.org/110.1093.

Loxton, D., Powers, J., Fitzgerald, D., Forder, P., Anderson, A., Taft, A., & Hegarty, K. (2013). The Community Composite Abuse Scale: Reliability and validity of a measure of intimate partner violence in a community survey from the ALSWH. J Womens Health Issues Care, 2 (10.4172), 2325–9795.

McDonald, R. P. (1978). A simple comprehensive model for the analysis of covariance structures. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 31, 59–72.

Muthén, B., du Toit, S. H. C., & Spisic, D. (1997). Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modeling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Technical report. Retrieved from: https://www.statmodel.com/download/Article_075.pdf

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén

Postmus, J. L., Plummer, S. B., & Stylianou, A. M. (2016). Measuring economic abuse in the lives of survivors: Revising the Scale of Economic Abuse. Violence against Women, 22 (6), 692–703.

Rietveld, L., Lagro-Janssen, T., Vierhout, M., & Wong, S. L. F. (2010). Prevalence of intimate partner violence at an out-patient clinic obstetrics–gynecology in the Netherlands. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 31 (1), 3–9.

Rodenberg, F., & Fantuzzo, J. (1993) The Measure of Wife Abuse: Steps toward the development of a comprehensive assessment technique. Journal of Family Violence, 8 (3), 203–217.

Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M. J., & Chen, J. (2018). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2015 data brief–updated release. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf

Stonienė, L., Aguonytė, V., ir Narkauskaitė, L. (2013). Intymaus partnerio smurtą patyrusių moterų tipai. Visuomenės sveikata, 2 (61), 38–44.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intramarital conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41 (7), 5–8.

Straus, M. A. (1990). The Conflict Tactics Scale and its critics: An evaluation and new data on validity and reliability. In M. A. Straus, R. J. Gelles (Eds.), Physical Violence in American Families. Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 families (49–73). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Tamutiene, I., De Donder, L., Penhale, B., Lang, G., Ferreira-Alves, J., & Luoma, M. L. (2013). Help seeking behaviour of abused older women (cases of Austria, Belgium, Finland, Lithuania and Portugal). Filosofija. Sociologija, 24 (4), 217–225.

Tolman, R. (1989). The development of a measure of psychological maltreatment of women by their male partners. Violence and Victims, 4 (3), 159–177.

Tureikytė, D., Žilinskienė, L., Davidavičius, A., Bartkevičiūtė, I. ir Dačkutė, A. (2008). Smurto prieš moteris šeimoje analizė ir smurto šeimoje aukų būklės įvertinimas. Tyrimo ataskaita. Retrieved from: https://socmin.lrv.lt/uploads/socmin/documents/files/pdf/761_tyrimas_smurto_pries_moteris2008.pdf

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/

Žukauskienė, R., Kaniušonytė, G., Bergman, L. R., Bakaitytė, A., & Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I. (2019). The role of social support in identity processes and posttraumatic growth: A study of victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519836785

Žukauskienė, R., Laurinavičius, A., & Singh, J. P. (2014). Violence risk assessment in Lithuania. Journal of Psychiatry, 17 (4), 2–6.