Psichologija ISSN 1392-0359 eISSN 2345-0061

2021, vol. 64, pp. 38–52 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Psichol.2021.39

The Right to Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Neringa Grigutytė

Vilnius University, Institute of Psychology

neringa.grigutyte@fsf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4750-0363

Karilė Levickaitė

NGO „Mental Health Perspectives“

karile.levickaite@perspektyvos.org

Ugnė Grigaitė

NOVA University of Lisbon, Lisbon Institute of Global Mental Health

grigaiteu@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0767-9071

Abstract. The relationship between mental health and human rights is integral and interdependent. There are clinical, social and economic reasons, as well as moral and legal obligations to advance mental health care as fundamental to human rights. Significant considerations for this matter are especially crucial when addressing the COVID-19 pandemic across the world. The aim of this research study was to analyse the responses to the ongoing pandemic, concerning the human rights of persons with psychosocial disabilities and the right to mental health of the general population, in Lithuania. Methods included online surveys, semi-structured interviews, and a focus group. This article presents the results as a complex picture, containing the lived experiences of mental health difficulties of the general population, barriers to accessing the needed support and services, as well as analysis of violations of human rights. It also highlights the need for more research on the long-term consequences of the pandemic and lockdowns on the mental health of the population and on how the human rights of persons with mental health conditions, and especially those with psychosocial disabilities, can be better ensured and protected in Lithuania.

Keywords: human rights, mental health, psychosocial disability, COVID-19 pandemic.

Teisės į psichikos sveikatą užtikrinimas COVID-19 pandemijos metu

Santrauka. Psichikos sveikata ir žmogaus teisės yra neatsiejamos sritys ir viena nuo kitos tiesiogiai priklauso. Esama klinikinių, socialinių ir ekonominių priežasčių, taip pat moralinių ir teisinių įsipareigojimų gerinti psichikos sveikatos priežiūrą, siekiant įgyvendinti žmogaus teises. Ypatinga šios srities svarba iškyla susidūrus su pasauline COVID-19 pandemija. Tyrimu siekta įvertinti, kaip COVID-19 pandemijos metu buvo užtikrinta kiekvieno žmogaus teisė į psichikos sveikatą, teisė gauti psichikos sveikatos priežiūros paslaugas, ir žmonių, turinčių psichosocialinę negalią, teisės Lietuvoje. Taikyti metodai: internetinės apklausos, pusiau struktūruoti interviu ir fokusuota grupės diskusija. Rezultatai pateikiami kompleksiškai atskleidžiant populiacijos psichikos sveikatos sunkumų patirtis, kliūtis gauti reikalingą paramą ir paslaugas, žmogaus teisių situaciją pandemijos metu. Pabrėžtina, kad reikia daugiau tyrimų, kokie yra ilgalaikiai pandemijos ir karantinų padariniai žmonių psichikos sveikatai, taip pat tyrimų, analizuojančių, kaip Lietuvoje būtų galima geriau užtikrinti ir apsaugoti psichikos sveikatos sunkumų turinčiųjų, ypač asmenų su psichosocialine negalia, žmogaus teises.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: žmogaus teisės, psichikos sveikata, psichosocialinė negalia, COVID-19 pandemija.

Received: 02/06/2021. Accepted: 20/08/2021.

Copyright © 2021 Neringa Grigutytė, Kamilė Levickaitė, Ugnė Grigaitė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For us human beings, our health and the health of those we care about is a matter of daily concern. Regardless of our age, gender, socio-economic, ethnic or other background, we consider our (mental) health to be our most essential asset. The relationship between mental health and human rights is an integral and interdependent one. For instance, human rights violations adversely affect mental health. Secondly, mental health laws, policies, programs, and practices, such as coercive treatment, may hinder human rights. Finally, the advancement of human rights benefits mental health. These benefits extend beyond solely mental health, to the close connection between physical and mental health. Thus, there are clinical, social and economic reasons, as well as moral and legal obligations, to advance mental health care as fundamental to human rights (United Nations, 2018).

The right to health is an inclusive right, extending not only to timely and appropriate health care, but also to the underlying determinants of health. It is also stipulated so in Article 12 of the UN Convenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (United Nations, 1996). The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights declares that “the right to health is a fundamental part of our human rights and of our understanding of a life in dignity”. However, in a recent report on the right to mental health, the UN special rapporteur on the right to health Pūras (2020) pointed out that despite evidence that there cannot be health without mental health, nowhere in the world does mental health have parity with physical health in terms of budgeting, or medical education and practice.

Moreover, persons with disabilities face discrimination and barriers that restrict them from participating in society on an equal basis with others every day. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006) signalled a ‘paradigm shift’ from traditional charity-oriented and biomedical-based approaches to disability, to one based on human rights. The Convention is a powerful tool to empower people with disabilities, local communities and governments explore ways of fulfilling the rights of all persons with disabilities by developing and implementing legal, policy and practical measures (EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2020). The Convention emphasises the movement away from viewing persons with disabilities as ‘objects’ of social and medical care, towards ‘subjects’ with rights, who are capable of claiming those rights and making decisions for their own lives based on their free and informed will and consent, as well as being active citizens and members of society.

The term ‘psychosocial disability’ acknowledges and encompasses the fact that the medical definition of a ‘mental disorder’ or ‘mental disability’ is not broad enough to describe the diversity of both the determinants of mental health conditions and the barriers that exist in society and disable people. Psychiatric research shows that those with previously diagnosed mental health conditions are at a greater risk of experiencing an exacerbation of symptoms during the pandemic (Liu et al., 2020).

In this article, ‘mental health’ (including the additional concept of ‘psychosocial disability’) is referred to and explored as a continuum of the human condition (Galderisi et al., 2015), where every single person has a spectrum of various individual needs, capabilities, capacities, and barriers that they face in society. It is based on the human rights-based approach and recovery model, rather than on any traditional psychological or psychiatric theory or context.

Research on the effects of the pandemic on mental health already shows the predicted rise in anxiety, depression, and self-reported stress (Rajkumar, 2020), as well as signs of PTSS (Liu et al., 2020). Negative affectivity is found to be related to poor sleep quality, lack of social support (Rajkumar, 2020), or social capital (Xiao et al., 2020).

Additionally, mental health services are referred to in this article as the means by which people’s mental health needs are addressed and interventions delivered. The way these services are organised has an important bearing on their effectiveness and ultimately on whether they meet the aims and objectives of any given mental health policy (World Health Organisation, 2003). World health organization (WHO) recommends that countries develop a diversity of services based on the ‘optimal mix of services pyramid’, in which mental health care services that cost the least and are the ones most frequently needed (for example, self-care and informal community care) form the base of the pyramid; while more expensive services needed by a smaller fraction of the population (for example, long-term inpatient care facilities) are at the top of the pyramid (World Health Organisation, 2007). WHO promotes the pyramid to illustrate and ensure an optimal mix of mental health services (World Health Organisation, 2003). In the context of the current situation, the mental health systems aftermath might have the most important role due to the lack of preparation to accommodate mental health needs, which have risen (Horesh & Brown, 2020).

On 18th March 2020, in reaction to the outbreak of the new coronavirus infection COVID-19, WHO published the Mental Health and Psychosocial considerations (World Health Organisation, 2020 a) for the general population including healthcare workers, team leaders, health facility managers, and those caring for children, older adults and people in isolation. There were special considerations outlined, targeting women (UN Women, 2020), other marginalised populations (Elwell-Sutton et al., 2020; Black, 2020) and those with psychosocial disabilities (World Health Organisation, 2020 b).

The aim of this research study is to analyse the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, concerning the human rights of persons with psychosocial disabilities and the right to mental health of the general population in Lithuania. This article presents an analysis dedicated to pandemic-related mental health matters salient to the general population, and mental health-and needed services-related issues possibly encountered by those with psychosocial disabilities, and those who have been dependent on institutional and residential care during the pandemic. Finally, it explores the accessibility and barriers to accessing mental health and social care services in Lithuania during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

Sample

1045 participants took part in the study. Two groups were composed:

I. 939 respondents completed the population survey (86% were women; the average age of the respondents was 40 years; 67.5% of the respondents indicated that they live in a big city, 20% live in an urban area, and 12.5% live in a rural area).

II. 106 professionals and experts composed the other group. 92 persons completed the survey for professionals: psychologists (39.6%), social workers (20.8%), psychiatrists (9.4%), volunteers of emotional support lines (9.4%), psychotherapists (7.3%), social work assistants (3%), nurses (3%), art therapists (2.1%), and others (5%). 89% of respondents worked in more than one job (including both primary and secondary positions). 12% of professionals worked only privately (82% of them psychologists or psychologists-psychotherapists), and 11% worked both privately and in the public sector). Additionally, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 8 service providers (2 from primary mental health care centres, 2 from psychiatric hospitals/units, 2 from social care institutions, and 2 from non-governmental organisations providing psychosocial services. The selection of service providers was applied according to the criteria of different regions: in each group one service provider was from one of the large cities, the other one was from the region). Moreover, 6 experts took part in a focus group discussion (4 representatives of professional associations of psychologists, psychiatrists and 2 representatives of organizations uniting people with psychosocial disabilities).

Methods

I. Two online surveys were structured to reflect people’s lived-experiences of mental health conditions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to analyse the available support, and barriers to receiving it. Online surveys were conducted after the first quarantine, and before the start of the second one – from September to November 2020. Both surveys were conducted on the Google Forms platform, disseminating information through social networks and sending it to target groups of professionals. The average response time was 10–15 minutes.

The population survey consisted of 25 questions addressing the following topics:

• Well-being and hardship during the pandemic: e.g. rating their mental health in the period of about half a year before the pandemic started and in the period that was the most difficult for the person during the pandemic; what mental health difficulties a person encountered during the pandemic; has a person experienced such or similar difficulties as worsened emotional, psychological wellbeing, worsened quality of social life or other mental health difficulties during the pandemic (4 questions).

• Seeking and getting help in cases of difficulties: e.g., has the person asked for support from their relatives, friends, community or other people to overcome the mental health difficulties encountered during the pandemic, and from whom; how much these people have helped and what hindered the ability to receive help from other people (4 questions).

• Use of mental health or emotional support services and barriers to accessing such services: e.g., have the respondents used mental health care or emotional support services during the pandemic, and what services; have the provided services helped; have the respondents payed for the mental health care services they received; has the person sought mental health services for the first time during the pandemic; what made using these services more difficult during the pandemic, etc. (10 questions).

• Socio-demographical information: gender, age, education, place of residence, relationship status (7 questions).

The survey for professionals was developed to target the providers of mental health care and social care services. 8 questions were formulated:

• 3 questions about the workplace and positions.

• 5 questions about the services provided (are services paid for, the provision of services during the pandemic, the barriers encountered in providing services, and suggestions for better responses to a pandemic situation).

II. Semi-structured interviews were constructed to discover deeper layers of the topic and to explore the respondents’ experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic, utilisation of mental health services, and the situation regarding human rights. Interviews were conducted during the second quarantine, in March 2021. Unfortunately, due to the quarantine restrictions, it was impossible to get access to residents of social care homes, hence, only services providers were interviewed in the end. The respondents revealed their experiences during both quarantines and reflected on the dynamics of the changes. Basic interview questions were formulated to explore the consequences of the pandemic on the services provided by segregated institutions; the main barriers to receiving services before and during the pandemic; the approach towards development of mental health or social care services for Lithuanian society.

III. A focus group discussion was organised aiming to collect independent experts’ reflections on a) the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and quarantine on society and people with lived-experience of mental health conditions and/or psychosocial disabilities, b) factors influencing access to psychosocial services, and c) human rights during the pandemic. The focus group took place online during the second quarantine, in March 2021.

Ethical Considerations. In line with research ethics, all research participants signed Informed Consent Forms. Participants were introduced to the objectives of the study, confidentiality and anonymity of the data, the possibility to terminate their participation in the study at any time, and the conditions of data processing and storage. Audio recordings of the interviews and focus group meetings were made with the consent of the participants and destroyed after the transcription process. Transcripts submitted for data analysis were depersonalised. Only members of the research team who have signed confidentiality commitments have access to the study data.

Data Analysis

Interviews and the focus group meetings were recorded. Audio recordings were transcribed. Thematic analysis was used for qualitative analysis, and IBM SPSS Statistics.23 program was used for the statistical analysis of the online surveys’ data. Thematic analysis and statistical analysis were integrated to respond to the research objectives.

Results

Population’s responses to the Covid-19 pandemic

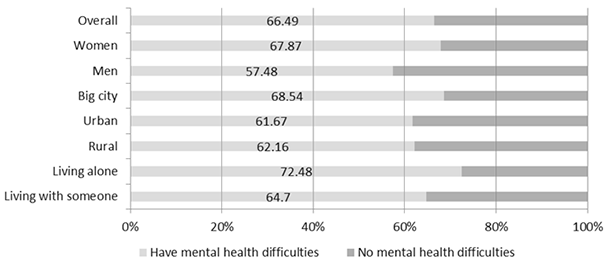

66.49% of 939 respondents experienced some kind of mental health difficulties during the pandemic period, up until the second lockdown in Lithuania. Results in Figure 1 show that the proportion of women with mental health difficulties was higher than that of men; more people living in large cities experienced mental health problems compared to those living in urban or rural areas; there were more mental health difficulties among people living alone than among those living with someone else.

Figure 1

Percentage distribution of experienced mental health difficulties by groups

Most commonly respondents experienced anxiety (47.5%), fear (15.5%), loneliness (15.5%), sleep problems (9.5%), sadness (7.8%), apathy (7.2%), anger (6.7%), panic attacks (5.4%), burnout (5.3%), depression (4.6%), and suicidal ideation (9.6%). 2.9% of respondents indicated that their previous mental health difficulties had deepened during the pandemic.

The results of the survey demonstrated that not everyone who experienced mental health difficulties sought help. The most frequently mentioned sources of help or support were relatives and the community (67.4%). 21% of the respondents used mental health services (most of them also approached their relatives and the community). It is important to note that 17.9% used mental health services before the pandemic. 3.1% of respondents applied for professional help for the first time during the pandemic. Respondents indicated the following help and services used: counselled by a psychologist (50%), psychotherapist (29.5%), psychiatrist (24.2%), used prescribed medication (20.4%), called helplines (7.6%), attended peer support groups (6.8%), visited a family doctor (5.3%), was in a psychiatric hospital (3.8%), and accessed day centre activities (2.3%). It is also important to emphasise that 52% of respondents paid for mental health services, 34.3% used free services, and 13.7% paid for a part of the services received.

32% of the respondents, who acknowledged health difficulties did not use mental health services and did not seek any help from relatives and/or the community.

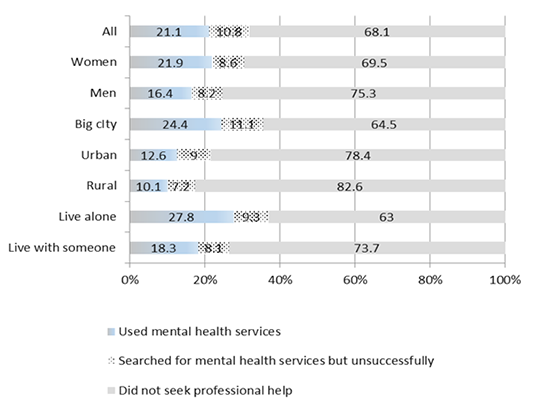

Figure 2

Percentage of people with mental health difficulties, depending on whether they used mental health services, searched for them, or did not seek professional help

The lowest percentage of people who used mental health services were among those who lived in a rural or urban area (twice less often as those who lived in a big city). It is also important to note that women were more likely to seek mental health services than men. The highest percentage of those who used mental health services were among those living in big cities and those who lived alone (see Figure 2).

Users of mental health services (21% of those who reported having had mental health difficulties) indicated barriers to receiving these services: 36.4% said that remote services were less suitable for them than in-person contact; 9.8% indicated that they did not have the conditions to receive remote assistance at home (a lack of private space, internet connection problems, etc.); 7.6% identified the lack of finances as one of the barriers to receiving consistent help (for example, a number of respondents were unable to continue counselling with the same professional as before due to the loss of income). 33.3% of those who used mental health services stated that mental health services had become inaccessible (for example, long queues, difficulties in reaching them, delayed prescriptions, shorter or interrupted consultations, breakup of support groups’ meetings). However, 20.5% of respondents noted that remote services have improved their general availability and the volume of information on mental health has increased in the public discourse.

Those who did not use mental health services (79% of those who reported having had mental health difficulties) cited a number of reasons why they did not seek help. One third of the respondents in this group said that they did not feel the need to seek help; a quarter had enough other help resources. As many as 20% of respondents in this group mentioned the unavailability of services. 5% of respondents identified a financial barrier as one of the obstacles to receiving any help. A few comments revealed the existing stigma of mental health services: 5% of participants did not dare to seek help, they did not believe in help; 2.2% said they were ashamed to seek help. 2.2% of respondents did not apply for help because they did not want to receive it remotely.

Analysing the answers of persons who unsuccessfully sought mental health services, the most common reasons were as follows: expensive and therefore inaccessible services, a lack of confidence to apply for help, and dissatisfaction with remote services. A few respondents indicated they did not seek help because they were afraid that others would find out about them visiting a mental health professional, or that “there will be a record that I have depression”. Also, it was reported that there was a lack of information on where to get mental health services.

Professionals’ reports on reactions to the Covid-19 pandemic

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns on public mental health

According to the respondents, the impact on public mental health and people’s reactions to the first and second quarantine in Lithuania were very different. The first lockdown was a severe shock for the general public, requiring adaptation to the changed conditions. Uncertainty sparked fear and insecurity, especially in the absence of personal protective equipment. According to experts, even if the pandemic affected society as a whole, those who had difficulties or fewer resources before the pandemic, including financial ones (especially those who had little use of smart technologies before the quarantine), found it more difficult to switch to remote services. Social support services have become inaccessible, medical services were provided minimally; only the basic medical care was available. Experts have identified several groups of society more severely affected by the pandemic and restrictions:

• Parents raising underage children (work and life balance, caring for children at home).

• People caring for their relatives with a psychosocial disability or mental health conditions (combining working and care-giving as services declined).

• People with psychosocial disabilities or mental health conditions (mental health needs not responded to or declined services).

• Medical practitioners and psychosocial care service providers (difficulties in remaining safe and securely providing direct services and/or difficulties in switching to remote working).

The second lockdown highlighted organisational challenges faced by psychosocial services’ providers. There was a lack of legal regulation of procedures for the provision of services (for example, extension of disability status or processing of the documents of a person with a disability upon reaching the age of adulthood), which affected service users and their carers financially (they did not receive welfare benefits). Challenges for people with mental health problems using remote services (such as online-banking) have also emerged. In addition, various legal documents and information were inaccessible to individuals with intellectual disabilities and/or mental health conditions. During the second quarantine, individuals without disabilities adapted better. Experts believe that people with psychosocial disabilities will experience negative consequences of the pandemic and restrictions for a long time to come.

Mental health and psychosocial services

The analysis revealed that not all sectors of services faced the same challenges. The provision of services was not stopped in private psychotherapeutic practice, helplines, private health care institutions, non-governmental organisations, general and psychiatric hospitals, and social care institutions. However, representatives of almost all these sectors mentioned that the level of services provided had decreased and there was a temporary cessation of support provision (due to the restrictions on the flow of people, or the lack of technical possibilities for receiving remote services).

Greater difficulties to adapt to the pandemic situation occurred in primary mental health care centres, psychiatric hospitals, social care institutions for persons with disabilities, and mental health clinics, as well as addiction treatment institutions. Outpatient day services suffered the most. There was no psychosocial rehabilitation, occupational work, group and individual counselling, or planned psychiatric services available, even some departments in hospitals were closed. Some mental health professionals struggled to have the appropriate technical possibilities to work remotely, and some were forced to take unpaid leave. Non-medical, psychosocial, outpatient mental health services were significantly reduced and medical inpatient treatment predominated during the pandemic.

During both the first and second quarantines, there was a decrease in the number of people with milder mental health difficulties, but an increase in the number of people with severe conditions within mental health services. According to the respondents, the mental health status of service users was better during the first quarantine, and more relapses occurred during the second one. The flow of COVID-19 survivors, those, whose relatives died from COVID-19, and clients with increased pandemic anxiety approaching mental health services was observed during the second quarantine.

In long-term social care institutions, both staff and residents were uncertain about their health due to COVID-19 infection. When residents lost opportunities to participate in outpatient day care centres or psychosocial rehabilitation programmes, staff of long-term social care institutions had to take on more responsibilities, so the workload increased. The burden also increased due to staff illness, especially when social care institutions became the epicentres of COVID-19 outbreaks. When residents became ill with COVID-19, they were isolated: they received physical aid, but they experienced great stress due to the changed environment and forced isolation. Residents were encouraged to seek help from helplines, psychologists communicated with them over the phone. Remote services were not available to everyone due to the lack of technical possibilities and individual capabilities and personal needs.

The right to mental health

Based on the reports of professionals and experts, the state’s response to public mental health needs and the right to mental health do not appear to have been guaranteed, especially during the first lockdown. It seems that the health care system itself had to survive during the first quarantine, and only later it could take care of the needs of the users of mental health services. The health care system in Lithuania was completely unprepared for the pandemic. The large premises of health and social care institutions mostly did not meet the epidemiological standards required. Some institutions put their mental health care professionals (such as psychologists, social workers, occupational therapists) on a furlough, encouraged them to take unpaid leave or transferred them to work in other healthcare areas, without decent recognition of the need for psychosocial services. Chaotic enactment and rapid changes in laws and regulations, and requirements to react ‘immediately’ gave rise to frustration and fatigue among service providers and administration. The quality of services deteriorated. Psychosocial services were inaccessible enough for people with mental health conditions or psychosocial disabilities during the first quarantine. People who could feel an impending crisis had to wait until it got worse before they could get any help. Mental health services were closed very abruptly at the beginning of the first lockdown. These services recovered and became operational again in mid-June 2020 with the end of the first lockdown. The lack of services during the first lockdown is reflected in the current delivery rates of mental health services, as the number of clients with more severe conditions increased during the second wave of the pandemic.

A significant number of social care institutions have become epicentres of COVID-19 infection. Personnel experienced an increased workload due to COVID-19 illness in both residents and staff. It was difficult to ensure safety requirements in care institutions because the communities inside those were large, the premises of institutions were not adapted, and usually there were no opportunities to move to different premises. According to staff, the mental health state of the population deteriorated, outbreaks of aggression among residents increased, it was difficult to explain to the residents the need to comply with safety requirements, services were fragmented. Some residents were forbidden to go for a walk or were locked-up in their rooms without access to a shower when there was a higher risk of infection. Carers and relatives could not visit residents in social care institutions, which caused great emotional suffering, especially for those who had been in hospitals or institutions for several months. There were cases where residents of social care institutions were kept in isolation even after the end of the first lockdown to prevent outbreaks of COVID-19. Such situations were completely disregarding human rights.

After reports in the media about the lock-up of a care home resident behind bars and other violations of the rights of people with psychosocial disabilities (Žmogaus teisių komitetas, 2020), some specialists directly answered that “We have little knowledge of human rights” or that “Human rights are taboo and do not reach practice”.

After COVID-19 outbreaks in psychiatric hospitals, patients were not allowed to go home for self-isolation, which further increased the risk of infection. The provision of information to persons on their treatment and health status has reduced significantly.

Discussion

Mental health during the pandemic

67% of respondents (n = 939) have experienced some kind of mental health difficulties during the pandemic period up until the second lockdown in Lithuania. Most commonly, participants experienced anxiety (48%), fear (16%), loneliness (16%), suicidal thoughts (10%), sleep problems (10%), sadness (8%), apathy (7%), anger (7%), panic attacks (5%), etc. Mental health problems were more prevalent among three populations, as follows: women, people living in large cities, and people living alone. These results are in line with other studies (Skruibis, 2021; Geležėlytė et al., 2021). However, this study revealed that another group that was particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic were those with psychosocial disabilities or experiencing mental health difficulties before the pandemic.

The results show that the second lockdown resulted in more people experiencing serious mental health conditions and larger numbers of relapses. Specific population groups that are more severely affected by the pandemic and restrictions, according to experts, are parents raising minors, medical practitioners and psychosocial care service providers, as well as individuals with psychosocial disabilities or experiencing mental health difficulties and their carers. The last two groups seem unnoticed and forgotten about by politicians, even though experts state that the pandemic restrictions and their consequences will affect people with psychosocial disabilities to the largest extent.

A fifth of individuals experiencing mental health difficulties approached mental health care services: 80% appealed to psychologists or psychotherapists, 24% to psychiatrists, 8% called helplines and fifth used prescribed medication. Still, this data uncovers a long-standing problem, as 66% of people had paid for mental health care services, at least in part. It seems the use of paid mental health services, such as sessions with psychologists or psychotherapists, has grown significantly during the pandemic. The need for psychological services increased during the pandemic, as evidenced by practice and research (Bagdonas et al., 2020). The government reacted and during the first quarantine, alongside other means, 5 low-threshold consultations with a psychologist were available for people in public health offices and a free national unified emotional support line was established (LR SAM No. V-1596).

Provision of services during the pandemic

There were some pre-existing barriers related to provision and receiving of mental health care services before the pandemic in Lithuania: the existing demand for services and support within communities did not match the scope of provision, accessibility and affordability of especially the psychotherapeutic services (Grigaitė, 2017a). Independent living services for people with disabilities were also difficult to access and relied mostly on institutional and segregated care, often with regular and complex violations of human rights (Grigaitė, 2017b; Human Rights Monitoring Institute, 2020).

The first lockdown completely disrupted social support and mental health care services. Outpatient day hospitals and psychosocial rehabilitation services were suspended. People could only access necessary basic medical care and get services at long-term care institutions. Hospitals capacity reduced significantly due to the structural changes made to meet safety demands and avoid future infection outbreaks. Psychosocial support services were suspended until the end of the first lockdown. This time-off was used to reorganise the system and prepare it for remote working. This reorganisation combined with patient flow control and other safety measures created a better working system with a combination of remote and in-person services. The system continued to work during the second lockdown. New private initiatives for psychological remote help arose (for example, mindletic.com, pasiklabek.lt, medo.lt).

People with psychosocial disabilities or experiencing mental health conditions were practically restricted from all services during lockdowns. Even during the second lockdown, when outpatient and social care services became more accessible, people with psychosocial disabilities still reported having had difficulties getting the required support. Newly created psychosocial services for mental health crisis management were customised for the general population. Overall, continuity of services has not been ensured.

Psychosocial support providers also faced difficulties during the pandemic, such as no proper remote working conditions; constant uncertainty together with unclear and rapidly changing orders for service provision; difficulties complying with rapidly changing legislation and regulations; a lack of official regulations of specific parts of services, for example, regarding the extension of disability claims and benefits; a lack of teamwork and democratic decision-making; a lack of information regarding work specificity. Some mental health care professionals (for example, psychologists, social workers) working in health care institutions were forced to fight for the opportunity to work remotely. Others received a furlough or were encouraged to take unpaid leave without recognising the need for psychosocial services during the quarantine. This confirms the predominant biomedical approach instead of a biopsychosocial one (Patel et al., 2018).

Human rights in mental health and social care services during the pandemic

Governmental policies regarding mental health and social care services have been mainly temporary and focused on pandemic management. They were usually customised to adjust to the needs of the general population, who did not have a disability or had not experienced mental health problems before. Legislation and regulations of psychosocial care services during lockdowns did not ensure the protection of human rights. Rather, they prioritised carrying out safety measures and strictly monitoring the flow of service users and visitors (Levickaitė, 2021).

During the pandemic, and especially during the first lockdown, the right to (mental) health was violated. It had a huge negative impact on the accessibility and quality of mental health services, especially psychosocial services. Some institutions put their mental health care professionals on a furlough, encouraged them to take unpaid leave or transferred them to work in other healthcare areas. Such actions revealed the attitudes that those institutions have towards mental health care, i.e., disrespectful and indifferent together with a lack of acknowledgment for its importance. Moreover, existing shortcomings of the mental health system in Lithuania were triggered, demonstrating that a significant part of mental health services among those in need was privately paid for.

The first lockdown restricted access to psychosocial support required by people with psychosocial disabilities or mental health conditions. Access to services remained partially restricted during the second lockdown too. There is alarming evidence of human rights violations during lockdown in long-term social care homes and psychiatric hospitals: disrespecting human dignity, the right of choice, freedom, and independence, right to participate in all decision-making regarding their treatment and other areas of life.

In conclusion, the pandemic, as every crisis, brings opportunity for change. The pandemic prompted the development of remote care and support services and in this way increased the accessibility to mental health and social care services in general. Remote services are likely to remain after the pandemic is over too. Cooperation of professionals from different fields and the use of online learning courses was increased. Government has given more priority and some financing for mental health: several new initiatives and psychosocial services have been created in the field (e.g., mobile crisis response teams and psychological help provided in public health offices). Mental health has become a common topic covered in the media and in public discourse. However, more research is necessary for analysing the long-term consequences of the pandemic and lockdowns on the mental health of the population, as well as on how the human rights of persons with mental health conditions, and especially those with psychosocial disabilities, can be better ensured and protected in Lithuania.

Acknowledgements

The development of this article was partially financially supported by the FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (UI/BD/151073/2021). The research study was implemented by NGO Mental Health Perspectives and Human Rights Monitoring Institute, with financial support from the Open Society Foundations. The authors would like to express appreciation and gratitude for their contributions to Aurelija Auškalnytė, Rima Balkūnė, Rūta Simutytė, Viktorija Paškauskaitė, Kotryna Sipko, and Rūta Drakšaitė.

References

Bagdonas, A., Remeikienė, R., Davulis, T., Gasparėnienė, L., ir Raistenskis, E. (2020). VU Teisės fakulteto mokslininkų tyrimas: kovos su COVID-19 fronte ir užfrontėje nieko naujo. Delfi. Paimta iš https://www.delfi.lt/verslo-poziuris/teisininko-patarimai/vu-teises-fakulteto-mokslininku-tyrimas-kovos-su-covid-19-fronte-ir-uzfronteje-nieko-naujo.d?id=86002464

Black, M. (2020). How COVID-19 Is Impacting People Experiencing Homelessness. Global Citizen. Paimta iš https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/coronavirus-impact-on-homessless-population/.

Elwell-Sutton, T., Deeny, S., & Stafford, M. (2020). Emerging findings on the impact of COVID-19 on black and minority ethnic people. The Health Foundation. Paimta iš https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/emerging-findings-on-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-black-and-min

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020). EU Framework for the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Paimta iš https://fra.europa.eu/en/cooperation/eu-partners/eu-crpd-framework.

Galderisi, S., Heinz, A., Kastrup, M., Beezhold, J., & Sartorius, N. (2015). Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 231–233. doi: 10.1002/wps.20231.

Geležėlytė, O., Nomeikaitė, O., Kvedaraitė, M., ir Kazlauskas, E. (2021). Psichikos sveikata COVID-19 pandemijos eigoje. Paimta iš https://www.fsf.vu.lt/psichologijos-institutas/psichologijos-instituto-struktura/centrai/vu-traumu-psichologijos-grupe#covid-19

Grigaitė, U. (2017). The Deinstitutionalization of Lithuanian Mental Health Services in Light of the Evidence-based Practice and Principles of Global Mental Health. Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika, 15, 7–26. https://doi.org/10.15388/STEPP.2017.15.10806

Grigaite, U. (2017b). Human Rights Conditions and Quality of Care in ‘Independent Living Homes’ for Adults, who have Intellectual and/or Psychosocial Disabilities, in Vilnius: Analysis of Good Practice Examples, Systemic Challenges and Recommendations for the Future. MSc Thesis/WHO Quality Rights Assessment. Paimta iš http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/quality_rights/QRs_Lithuania.pdf?ua=1

Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. (2020). Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(4), 331–335. doi: 10.1037/tra0000592.

Human Rights Monitoring Institute (2020). Human Rights in Lithuania 2018–2019: Overview. Paimta iš http://hrmi.lt/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ZmogausTeises_170x249mm_EN-FINAL.pdf

Levickaitė, K. (2021). Psichikos sveikata COVID-19 pandemijos metu: įžvalgos, patirtys ir rekomendacijos. [Pranešimas konferencijoje]. Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. Paimta iš https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mSsZMWrbzks

Liu, C. H., Stevens, C., Conrad, R. C., & Hahm, H. C. (2020). Evidence for elevated psychiatric distress, poor sleep, and quality of life concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic among US young adults with suspected and reported psychiatric diagnoses. Psychiatry Research, 292, Article 113345. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113345.

Liu, N., Zhang, F., Wei, C., Jia, Y., Shang, Z., Sun, L., ..., Liu, W. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Research, 287, Article 112921. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921.

LR sveikatos apsaugos ministro įsakymas „Dėl ilgalaikių neigiamų covid-19 pandemijos pasekmių visuomenės psichikos sveikatai mažinimo veiksmų plano patvirtinimo“. 2020 m. liepos 3 d. Nr. V-1596.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., ..., UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet, 392(10157), 1553–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X.

Pūras, D. (2020). Right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. United Nations General Assembly. Paimta iš http://www.infocoponline.es/pdf/A_HRC_44_48_E.pdf

Rajkumar, R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, Article 102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066.

Skruibis, P. (2021). Visuomenės psichikos sveikata COVID-19 pandemijos metu [Pranešimas konferencijoje]. Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. Paimta iš https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mSsZMWrbzks

World Health Organization (2003). Organization of services for mental health. Paimta iš https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/4_organisation%20services_WEB_07.pdf?ua=1

World Health Organization (2007). The optimal mix of services for mental health. Paimta iš https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/2_Optimal%20Mix%20of%20Services_Infosheet.pdf.

World Health Organization (2020a). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Paimta iš https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf

World Health Organization (2020b). Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak.

United Nations (1966). International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. Paimta iš https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-3&chapter=4

United Nations (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Paimta iš https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

United Nations (2018). Mental health is a human right. Paimta iš https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/MentalHealthIsAhumanright.aspx

UN Women (2020). UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women.

Žmogaus teisių komitetas (2020). Žmogaus teisių komitetas išklausė informaciją apie padėtį socialinės globos namuose – pagarbaus požiūrio į žmogų trūkumas bado akis. Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas. Paimta iš https://www.lrs.lt/sip/portal.show?p_r=35436&p_k=1&p_t=272670

Xiao, H., Zhang, Y., Kong, D., Li, S., & Yang, N. (2020). Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in January 2020 in China. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 26, Article e923921-1. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923921.