Psichologija ISSN 1392-0359 eISSN 2345-0061

2025, vol. 72, pp. 84–98 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Psichol.2025.72.7

“Not Entirely Myself”: Young Women’s Verbalized Experiences of Self in Social Context

Junona S. Almonaitienė

Lithuanian University of Health Sciences

junona.almonaitiene@lsmuni.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4674-1464

https://ror.org/0069bkg23

Rasa Paulauskaitė

Lithuanian University of Health Sciences

lolarasa@inbox.lt

https://ror.org/0069bkg23

Abstract. The aim of the qualitative research presented in the article was to disclose young adult women’s experience of Self in a social context, which was inspired by a wider problem of subjectively experienced interiority in young adults. In the introduction, the authors clarify their understanding of the Self and justify the relevance of the empirical study. The acquired data consists of 6 semi-structured interviews with 6 well-educated unmarried Lithuanian women of an average age of about 23. Reflexive thematic analysis was applied to the data, which led to the extraction of 4 themes: Not entirely myself, Barriers to being open, Pursuit of authenticity, and Possibilities in society. The first two were interpreted as the disclosure of reticence-inducing forces, whereas the next two as the disclosure of inclination to openness. Thus, the entirety of the data led to the identification of an internal dilemma. The abundant 2nd theme induced thinking about the strong feeling of the pressure of social environment characteristic to young women. However, the study cannot answer the question whether the dilemma is specifically related to gender, age, education, as well as other social and cultural characteristics. As the dilemma may be related to subjective wellbeing, experiencing loneliness, social phobias or excessive conformity, further research can be initiated on the basis of this study. The overall impression from the transcripts also allows suggesting that the participants had experience of their inner Self as persistent phenomena, the essence of a personhood, which is not reducible to the totality of social roles, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and other aspects of the Self.

Keywords: young adult, women, reflexive thematic analysis, Self, self-disclosure, feminist studies.

„Nesu visiškai savim“: įžodintos jaunų moterų savojo Aš patirtys socialiniame kontekste

Santrauka. Straipsnyje pristatomas kokybinis tyrimas, kurio tikslas – atskleisti jaunų suaugusiųjų moterų savojo Aš patyrimą socialinių santykių kontekste. Įvade pristatoma autorių pasirinkta savojo Aš (angl. Self) samprata ir tyrimo kontekste aktualūs ypatumai, pagrindžiamas empirinio tyrimo aktualumas. Taikant reflektuojamosios teminės analizės metodą, interpretuojama šešių pusiau struktūruotų interviu medžiaga. Tyrime dalyvavusių moterų amžiaus vidurkis – apie 23 m., jos buvo netekėjusios, neturinčios vaikų, penkios studijuojančios universitete, viena jį baigusi. Analizės rezultatas – identifikuotos keturios temos: Nesu visiškai savimi, Kliūtys atsiverti, Autentiškumo siekis ir Sociumo teikiamos galimybės. Pirmosios dvi temos interpretuotos kaip užsisklendimą skatinančių postūmių įvardijimas, o antrosios – kaip atvirumą skatinančių. Taigi duomenų visuma leido įžvelgti vidinę dilemą: prieštarą tarp savo ir kitų autentiškumo siekio ir atsivėrimą kitiems ribojančių išgyvenimų. Dažnai minėtos įvairios atsiverti trukdančios kliūtys (šešios 2-osios temos potemės) atskleidžia jaunų moterų subjektyviai patiriamą stiprų socialinės aplinkos spaudimą. Tačiau tyrimas neleidžia atsakyti į klausimą, ar ši dilema sietina su lytimi, amžiumi, išsilavinimu, kitomis socialinėmis ir kultūrinėmis ypatybėmis. Ji gali būti susijusi su socialinėmis fobijomis, vienišumo išgyvenimais ar perdėtu konformiškumu, todėl šis tyrimas gali paskatinti tolesnius šiai dilemai skirtus įvairių socialinių grupių tyrimus. Surinktų duomenų visuma leidžia teigti, kad savasis Aš patiriamas kaip tolydus vidinis reiškinys, netapatus dažnai empiriškai tiriamų tam tikrų jo aspektų, pavyzdžiui, savivertės, saviveiksmingumo ar socialinių vaidmenų, visumai.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: jauni suaugusieji, moterys, reflektuojamoji teminė analizė, Aš, atsiskleidimas, moterų studijos.

Received: 2025-02-04. Accepted: 2025-04-16.

Copyright © 2025 Junona S. Almonaitienė, Rasa Paulauskaitė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

One’s sense of Self and identity is one of the most important characteristics of a human being. The popularity of encouragements to “nurture one’s own true self” and similar linguistic constructions confirms the existence of the notion of Self in the heads of the general public, and many psychologists in academic writings also accept it.

Self has been widely inquired by philosophy (names such as Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, David Hume, Daniel C. Dennett can be mentioned here), personality, social and cognitive psychology (James M. Baldwin, Gordon Allport, Harry S. Sullivan), neuropsychology (Julian Jaynes, Antonio Damasio), sociology (George H. Mead, Manford H. Kuhn, Thomas S. McPartland, Herbert Blumer, Erving Goffman) as well as by other human sciences. Thus, numerous social, social cognitive, and neuropsychological models of the Self-development and functioning have been created. Accordingly, the perspective in which research is embedded, and the researcher’s aim determines the definition and meaning of the term Self, as it is noted by Dumont (2010). Doubts have also been raised on whether such a phenomenon as Self exists at all, or it is just a convenient construction for everyday use as well as in the field of sciences. As Dumont (2010, 219) put it “by way of conclusion” to the chapter titled “The puzzle of the self”1:

“(…) All of these investigations and the sophisticated instrumentation that the modern scientist uses to study the elements of self have still not provided compelling, and universally accepted, evidence of its existence. Even though it is more than a substance, a way of being, empirically “the self” is still found as a term of convenience in all the languages of the world. If everyone talks about it, one may be excused for thinking that it must exist.”

Nonetheless, it can be concluded that the Self is a well-established longtime construction in science, and this is a phenomenon which people subjectively experience in everyday life.

For the purposes of the research presented in this article, while relying on the analysis of Dumont (2010), Rens (2019), Guo (2007), Zahavi and Zelinsky (2024), we define Self as a largely conscious and relatively stable result of one’s own life-long biopsychosocial history, which has boundaries perceived by oneself and others, and which establishes one’s identity.

Identity, personality, as well as interiority, and personhood, which are not so widely used in psychology, are the other polysemous terms, which have been interpreted ambiguously in relationship to the Self. Identity may be “understood as internal, subjective concept of oneself as an individual” (Reber, 1995, p. 341). However, “the concept of identity is defined at the level of the person as well as at the level of collective”, as suggested by Rens (2019, p. 2), and, in the opinion of Corfield (2021, p. 2), “an individual may have – indeed most do have – many overlapping identities”. The quotes clearly convey the idea that the two concepts are only partially overlapping, and, again, that it is not possible simply to replace Self by identity. A similar comparison with the construct of personality could be done in a nutshell, by adopting the view that personality can be “judged from outside”, while lacking the component of self-reflection.

William James is usually credited with the earliest conceptualization of Self in psychology, which is still widely discussed. Without going into his ideas in detail, it is worth noting that James stressed the multidimensionality of Self, distinguishing its spiritual, material, social aspects, and the pure Ego. The social self, according to James (1890, p. 294):

“(…) has as many different social selves as there are distinct groups of persons about whose opinion he cares. He generally shows a different side of himself to each of these different groups. Many a youth who is demure enough before his parents and teachers, swears and swaggers like a pirate among his “tough” young friends.”

James’ idea of a socially constituted Self (speaking in contemporary terms) served as a basis for numerous developments of influential schools in sociology and social psychology (those of G. H. Mead and M. H. Kuhn among others). As Dumont (2010, p. 200) accurately observed, the 20th century’s “has favoured a more sociologically oriented approach to an understanding of the human” (and the James’s ideas had essential influence on the Zeitgeist itself). Due to their great impact, the understanding that “some dimensions of Self are clearly social” (Zahavi and Zelinsky, 2024, p. 9), i.e., ‘born’ and active in social interaction is beyond doubt in contemporary social sciences.

Still, the theoretical positions that do not take into consideration one’s agency (or the feeling of one’s central active Self, according to James) in relationship with the environment are seen as quite extreme. Although a person’s sense of Self is undoubtedly related to the roles one plays and one’s memberships in certain social groups (nations, families, professional and confessional), some aspects of the Self are more individual, private, core or nuclear. These are the terms used by different researchers to name the essential part of the Self which is subjectively experienced as one’s deep interiority and a unique element of inner life.

As an example, Robins et al. (2010) differentiates several layers of the Self – personal, relational, social and collective – with regard of different ‘audiences’, or contexts of functioning. The personal layer is related to values, traits and abilities, whereas the relational layer refers to experiences in direct personal relationships, the social layer relates to a wider scope of roles and reputation, whereas the collective layer includes oneself into social categories such as ethnicity. Dumont (2010) finds background for adding more dimensions, e.g., being a Homo sapiens, terrestrial, or a galactic self.

In the research presented here, we focus on the private layer of the Self, however, without using the special term for that. One important reason for the choice is the fluent boundaries of the layers. In some sense, we use a narrow meaning of the Self term. Its understanding is close to phenomenological, with an emphasis on private experiences. However, in a strict sense, our study is not phenomenological because of its methodology which allows not only to reveal the uniqueness of an individual person, but also to explore certain trends; for details, see the Methods section.

The new knowledge is expected from this research because of the method applied. The private Self and its experiences, historically, were studied more by philosophers, without relying on empirical evidence. The theorizing on Self in psychology, e.g., in personality theories, also usually lack empirically based verification. The quantitative approach which dominated throughout the 20th century in psychology was unfavorable for assessing the deeper, private layers of the Self. However, we find that this is one of the topics for which a qualitative approach is well suited. The qualitative analysis of empirical data can shed light on the experiences related to the private levels of the Self and add new facets to understanding of what is assumed as ‘one’s own true self’ in subjective reality.

Attempts by psychologists to assess selfhood in the 20th century were focused mainly on the ‘obviously’ social layers, such as social roles and identities. One popular measure for these more accessible parts of Self is the Twenty Statements Test (TST, Kuhn and McPartland, 1954; see more in Almonaitienė, 2018), which potentially allows to grasp the private layer of selfhood. Also, psychologists prefer focusing on quite narrow aspects of Self, such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-monitoring, etc. in their empirical research (see more in Paulauskaitė, 2023). Still, they fail to reveal the whole picture of selfhood. Therefore, the research presented here has sought to give voice to people themselves while inviting them to share their experiences of their inner Self.

Next, we assumed that different layers of Self may have dynamic relationships, as well as the changing social environment with the private layer of the Self. Thus, we were interested in the me among others question, which is not just a scientific problem. How ‘being oneself’ fits in with the demands of diverse environment is a question which arises for many in their everyday life. Do people experience the dynamics, and, if so, how do they experience the dynamics? In the field of empirical research of this problem, the investigation of social comparison (started by Leon Festinger, see Festinger, 1954), the individualism-collectivism dimension (Marcus and Kitayama, 1991), and self-monitoring (Snyder, 1974) are among the best-known directions. Yet, these are different, and again, quite narrow aspects of the relationship in comparison with the aim of our study.

So, we put the aim of our qualitative research in the following way: to disclose young adults’ experience of Self in the social context.

Method

Procedure, data collection and software use

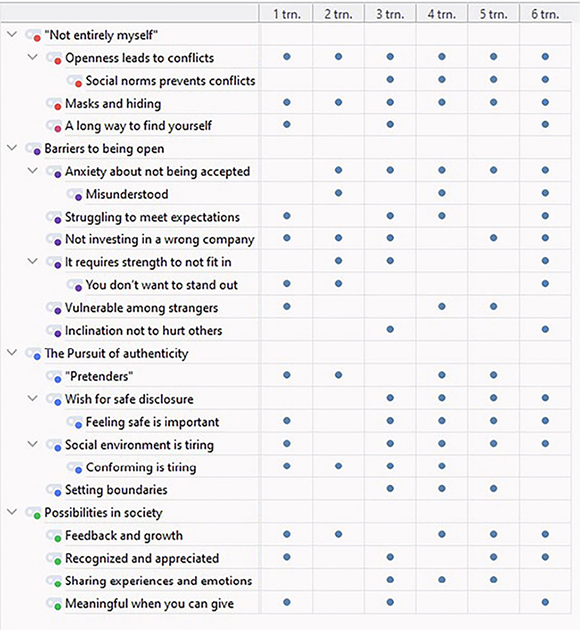

Semi-structured interviews were chosen to collect the data for this qualitative study. The Bioethics Center of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences approval Nо. BEC-SP(B)-34 was obtained prior to it. The interviews were conducted between December 2022 and January 2023. Eight key questions were asked, e.g.: What does it mean to you to be yourself? What does it mean to you to be among others? In some cases, additional questions were included, e.g.: What is most important to you when you are with others? The average duration of one interview was 34 minutes. The digital audio records of the interviews were made, which were transcribed by using Microsoft Word and corrected manually. The MaxQda 2024.1.0 software was used for coding and creating the coded items summary grid (Figs. 2 and 3).

Participants

The criteria of the participants’ inclusion were the age of the young adult and their willingness to contribute. They were invited by distributing the invitation through social networks, on the snowball principle. After the sample was created in the intended way, all the participants were well-educated young females. They could be more likely to reflect on the Self and have better ability to verbalize that reflection than the average member of society. We also believe that it was easier for young women than men to accept an invitation for the interview on selfhood from a young female researcher. The challenges faced by female researchers when the participants of qualitative research are male were explored by Lefkowich (2019); invisible power structures and gender norms were named in her article as the reasons of relevance. Similar factors could have had an impact on the composition of the sample in our research. The sample size was usual for this type of research and consisted of 6 women. Five of the participants were university students, and one was a graduate, all unmarried, without children, Lithuanian, of an average age of about 23.

Relation to feminist paradigms

This research contributes to feminist studies because of the composition of its sample. As discussed above, it was conceived neither as based on binary thinking, nor on the essentialist position2. Our approach is non-asymmetrically gendered and close to the post-feminist perspective3. However, we assume that women’s problems may be not identical to those faced by men in various social contexts in Lithuania, because of the culturally formed concepts of gender roles. Thus, the article can give inspiration for selfhood and identity research from the feminist perspective as well. We would like to pay attention that, in the early 2020s, the socialization of adolescent girls and young adult women takes place in an environment where the conceptions of gender roles are often questioned, but also tensions are growing between conservative and liberal views on gender roles. It is worth investigating whether, and how, young adult women are experiencing this.

Data analysis and interpretation

Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) was applied for the analysis of the transcripts. The first author analyzed the interview transcripts by relying on individual experience of the researcher interested in the Self psychology. An important incentive for the decision on such role distribution was the rapidly changing methodology of qualitative research, encouraging not to shy away from unconventional solutions (Brinkmann, 2022), and especially the recently updated approach to thematic analysis, as developed by Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. Braun and Clarke (2019, 2021, 2023) gave a systematic basis for the method, ready to overstate their own claims made in the widely acknowledged article of 20064. According to them, in case of RTA themes, they “are not identified, found or discovered, and they definitely don’t just “emerge” from data like a fully-grown Venus arising from the sea and arriving at the shore in Botticelli’s famous painting” (Braun and Clarke 2023, p. 4–5). The main features of RTA are the actuation of a researcher’s individual perspective and her theoretical background. So, RTA is a creative process of original interaction between the research data and the researcher’s individuality. This principle was followed throughout the analysis.

Results

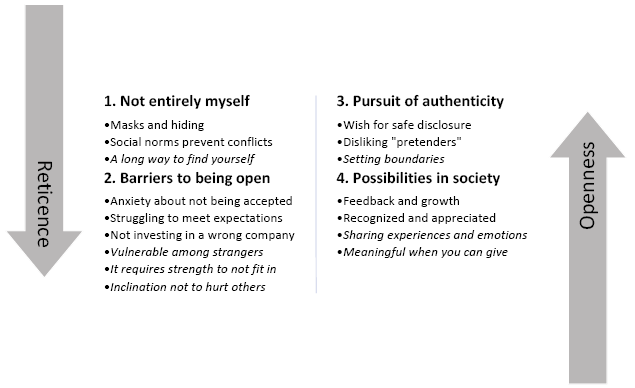

After analyzing the transcripts, I singled out 4 main themes (see Figure 1)5. In the first theme, Not entirely myself, I collated verbalizations on the experiences of being oneself among others, from a broad perspective. Here, I found that the women laid out their way of thinking about being a human and coexistence in general. The essence of the topic is well-reflected in the quote: “Maybe it’s rare that I’m completely myself. Maybe only with my closest people? Yet...” (3, 64)6. I identified two subthemes in most of the transcripts, and the third subtheme was less common, however, I found it important to mention as well (see Figure 2, which represents a summary of the coded items).

Figure 1

Results of RTA. The subthemes less frequent than 4 out of 6 are submitted in italics

To the Masks and hiding (6/6)7, I attributed those data items in which, directly or not so much, masks for hiding the true Self were named. “(…) society... [Pause] (...) [It] does not accept you the way you would like to be accepted. And... sometimes it seems better to put on a kind of mask, something like that, and just show what people like, and keep it for yourself, just keep that Self for yourself (...)” (2, 22). “(...) the less accepting the environment, the more you... the thicker the mask, so to speak, or the more masks you put on. So... yes, that being yourself depends on that social environment (...)” (3, 70).

I also found positive attitudes expressed towards not showing oneself openly and constructed subtheme Social norms prevent conflicts (6/6): “(...) I believe in that partially evolutionary approach. That we still... repress very much our instinctive… instinctive impulses. And that we are human beings [smiles] because we learned to communicate with each other in a civilized way, according to certain social norms. And it seems to me if we take it all away... then it would be a very poor situation. Because that’s where all that aggression would manifest itself, and everything that is destructive in us” (5, 28).

The verbalizations about difficulties of knowing your true Self were classified as a subtheme A long way to find yourself (3/6): “(...) there is still a long way to go, to discover who you are... (...) I could say that... [only] when I met... the right person... I discovered myself and understood who I am; well, I’m still learning, but...” (1, 16). “I think that being yourself is such a difficult thing (...), you need to be able to accept and see yourself. Well, what do you really want? Not what the world has imposed on you, the environment, but exactly what you want. Mm, what I want as a woman, as a person, as a daughter, as an employee” (6, 52).

Figure 2

The coded items summary grid

Note: Created by using MaxQda 2024.1.0 software.

In the second theme, Barriers to being open, I classified sharing personal experiences about some specific obstacles preventing them from opening among others.

Anxiety about not being accepted (5/6), when a specific reason for it was not named, seemed to me the most often expressed option. “That very, very strong feeling of vulnerability. And... you’re timid and perhaps uncomfortable, and you’re still afraid of not being accepted, being rejected, not being understood, because it’s really, really scary to reveal all of yourself, and... and to show, and just be yourself” (5, 66). I merged the Misunderstood here also: “I adapt, I try not to show my true face because... I think they won’t understand me” (2, 30).

Struggling to meet expectations (4/6) seemed associated with perfectionism, fear of criticism and underestimation, e.g.: “(...) maybe a little that perfectionism, but basically, those effort to please others (…), the supervisors, (...) university teachers, other students, friends, relatives, brothers, sisters… simply” (3, 36).

Not investing in a wrong company (5/6) experiences seemed to me most accurately expressed in the following statement: “(...) If you are among people who... you see that they will not understand you and are completely... different from you, then... you just put on a mask, or you are invisible, and... You ignore that fact, you go home understanding why you did that, and... you don’t invest your... time and your energy in people who are simply not worth it, and that’s it...” (1, 46–47).

Some women emphasized communication with strangers, in particular: “(...) among the people you know... there is no such instinct that... you... you are shy, or you are uncomfortable... But when you go out among people you do not know right now that factor comes into play that... you must protect yourself, maybe, from something. That... well, I don’t know... it’s hard to really name exactly that feeling.” (1 tr., 28). I collated such data items in Vulnerable among strangers (3/6).

I collated It requires strength to not fit in with You don’t want to stand out into one subtheme (4/6): “Well, to be a black sheep, I think it really takes some strength here. Having that different opinion really requires, well, such determination, strong self-confidence” (6, 66). “(...) it happens that everyone just gets on your nerves, so... you want to be invisible” (2, 52).

Some verbalizations were interpreted as the personal disposition not to offend others, without linking it to the observance of social norms and integrating them into the subtheme Inclination not to hurt others (2/6): “I don’t know, maybe it’s a little bit like protecting people, especially when people are... more modest or... less self-confident, that’s the desire to protect that people…” (3, 38). Although infrequent, I find that it draws attention to individual differences of the respondents, as I also found the subtheme Meaningful when you can give in the same two transcripts (see Fig. 2).

The Pursuit of authenticity theme deals with the desire for openness that I have revealed alongside with the forces inducing reticence. I found some verbalizations related to Wish for safe disclosure (6/6). The subtheme can be illustrated by the following subtle verbalization: “[Being yourself] probably means a kind of relaxation. When, finally, you can just sit down and relax and just... [to say for yourself] I feel this way, and (…) I think this way, and nothing [bad] happens!” (4, 16).

Next, social environment is tiring (6/6) seemed to me also unmissable and reasonable to place here. I interpreted it as a desire for authenticity in relationships, relying on the context. “In general, it might be useful to be alone sometimes... When you get tired of socializing, because we really do get tired, some of us have less, others more” (5, 78). I collated such verbalizations with more specific conforming is tiring (4/6), e.g., in this sequence: “[Being among others means] tension maybe... such as fatigue maybe, because simply, that anxiety and fear that you won’t be accepted, and the like... Well, it’s depressing... and, well, it takes away a lot of energy from you...” (4, 22). “And, I don’t like and I’m tired of pretending, I really don’t know how to pretend” (1, 30).

I also attributed comments about others to this theme, the Disliking ‘pretenders’ (4/6): “I (…) really don’t like those people who pretend... and they make me very... I lose my patience and it seems that I immediately want to... tell them – why do you act like that (...)?” (1, 44). “Well, that openness, sincerity, being your own Self. That’s the most important thing, that’s what I first notice in a person (...)” (2, 36).

The subtheme Setting boundaries (3/6) deals with seeking the balance between Me and others, reflecting the need to cherish one’s own Self. “You need to respect your values, have your own values, you should set those boundaries of yours, and to know where your personal boundaries end, and where that kind of... social learning from others begins, and the desire to be (…) a part of a team...” (3, 96). “A kind of not separating one’s own desires and one’s own values and one’s own needs, and too much identification with others, and considering only them, well, that also seems very harmful. That is, when a person feels that she can no longer distinguish where I am, where we are, and where the other person is... then it is also valuable to step back” (5, 78).

In Possibilities in society, I collated verbalizations on the positive sides of communicating and identified four subthemes. The Feedback and growth (5/6) was manifested as follows: “Another person, or people, can help you better understand who you are...” (4, 32). “That’s it, you can get to know yourself through it; that old saying – tell me who your friends are, I’ll tell you who you are” (5, 88). Recognized and appreciated (4/6): “Well, I also like the attention that being among people brings” (6, 44). Sharing experiences and emotions (3/6): “I think we need time with others, we need that closeness and warmth” (5, 76). The already mentioned meaningful when you can give (3/6): “Sometimes you just give. And, well, it gives that feeling of completeness, that you can just give.” “Where I work (...) I like to help [others] (...). It just fills me a lot” (6, 58 and 44).

Last, but not least, I summarized the social environments mentioned by women when they gave examples or some context for (not) expressing their Self (see Fig. 3). While analyzing the summary grid along with the content of the interviews, I found that the environments were seen as supportive or restrictive in most cases. Although this study is not quantitative, it is of interest to note that being in solitude or with pets was seen by women as the most favorable for being ‘themselves’. Next, women also indicated that they usually feel ‘themselves’ in the family of their parents and with their partners. Educational institutions, and especially work environments were seen as the most limiting. The virtual social networks were mentioned only once, as an example of distorted public presentation of Self.

Figure 3

The environments mentioned in the interviews

Norte: Summary grid was created by using MaxQda 2024.1.0 software). The numbers indicate how often the environment was mentioned in the transcript, but the value (seen as supportive or restrictive) is not represented

Discussion

The overall analysis of the transcripts allows suggesting that the participants had experience of their inner Self as a persistent phenomenon, the essence of a personhood, which is similar to the private layer deduced by Robins et al. (2010). The Twenty Statements Test (TST, Kuhn and McPartland, 1954) can be remembered here, which is a handy tool for the assessment of Self in the social context (Almonaitienė, 2018). However, when applying it, the respondents often define their Self through social roles. Still, in our research, the participants disclosed that some social roles were experienced as restrictions to the private Self. This shows the limitations of TST: it can reveal quite obvious identifications at the moment of inquiry but may fail to disclose the deeper layers Self, or the dynamics of the interrelationship of the layers involved.

We deduce inner dynamics while interpreting the results of the reflexive thematic analysis. As an indicator, we want to stress the contradiction in the entirety of the data. On the one hand, the women disclosed that they often were “not entirely themselves” among others, and mentioned various barriers for self-disclosure (themes 1–2, Fig. 1). On the other hand, they longed for more authenticity in relationships and communication and understood that important needs can only be met through self-disclosure (themes 3–4, Fig. 1). Thus, we conclude that the experience of inner dilemma and the tension related to it were characteristic to the women.

Is that internal dilemma related to gender, age, education, other social and cultural characteristics? And, if so, how much and in what way? This study is not sufficient to answer these questions. However, the specificity of the sample requires at least a short comment related to femininity and the young adult age.

Regarding femininity, we find it somewhat confusing that only one interviewee mentioned it directly. However, it fits well with the idea of the gender equality ideology and non-asymmetrically gendered feminist studies.

The abundant 2nd theme makes us think about the strong feeling of pressure from the social environment, which was characteristic among the women. Through the prism of ‘natural attitudes’ about girls, they want to be liked, but it comes at a price. Whether it is only typical of young females is an open question.

One more question which we raise is whether the dilemma is related to individualism and seeking to maintain independence from others (Marcus and Kitayama, 1991). Wong et al. (2021), Yu and Wong (2024), while relying on the ideas of Viktor Frankl, other existential and humanistic psychologists and non-Western spiritual practices, claim that the shifting focus from the Self to others may contribute to inner peace and subjective wellbeing. Further research is needed to shed light on these multifaceted culture-sensitive issues.

We got impression of the interviewees’ engagement and deep self-reflection during the analysis of the transcripts. As young adulthood is associated with self-discovery (see more in Paulauskaitė, 2023), we believe this can be the reason, and the decision to choose young adults for the study proved to be right. Delving more profoundly into the age differences of self-reflection and exploring ‘one’s true self’ may be interesting for developmental psychologists. However, the interviewees’ education could also be a potentially significant factor, as well as the individuals’ willingness to spend time discussing selfhood. Therefore, we assume that the participants do not represent the entire age group.

Also, we would like to discern the women’s expectations towards friends, romantic partners, and family. These aspects are useful to understand for all sides in relationships and for practicing psychologists. As a practical implication, we presume that the experience of the tension, when it is being felt acutely, can cause social phobia. Also, experience of loneliness or excessive conformity can be determined by the perceived pressure on private Self from outside.

Our main reflection on the method itself, i.e., reflexive TA, is the appreciation of Braun and Clarke’s (2019, p. 594) idea that themes “are creative and interpretive stories about the data, produced at the intersection of the researcher’s theoretical assumptions, their analytic resources and skill, and the data themselves”. It encouraged us to interpret the entirety of the data and concentrating on the internal dilemma, which would not be the result of other types of TA because of their principles (for the types, see Braun and Clarke, 2006; Braun and Clarke, 2019). In general, the method applied here opened out what kind of knowledge can be obtained by qualitative analysis of empirical data related to experiences of selfhood.

Conclusions

Based on the relevant scientific literature, we defined Self as a largely conscious and relatively stable result of one’s own life-long biopsychosocial history, which has boundaries perceived by oneself and others, and establishes one’s identity. While relying on theoretical deduction, different researchers name the essential part of the Self which is subjectively experienced as one’s deep interiority and a unique part of inner life. The overall analysis of the transcripts allows suggesting that the participants had experience of their inner Self as a persistent phenomenon and the essence of personhood.

After applying reflexive thematic analysis to the data of semi-structured interviews, we claim that the internal dilemma is the core of the creative and interpretive story about it. The participants of the study, young adults, well educated, unmarried women, on the one hand, were reluctant to disclose their Selves in many social situations. On the other hand, they longed for authenticity in interpersonal relationships. The anxiety about not being accepted, struggling to meet expectations and ‘not investing’ in a company which seems ‘completely different from you’ were the main obstacles for self-disclosure. Thus, the subjective feeling of a strong pressure from the social environment among the young women can be deduced. The research does not answer whether this is unique to that particular social group. It encourages further empirical qualitative research, as it can lead to contribution into psychology of the Self as well as wider social, cultural, feminist studies. The research of social phobias can also benefit from further exploration of the identified dilemma.

Author contributions

Junona S. Almonaitienė: analyzed the transcripts with the MaxQda 2024.1.0 software and interpreted the data by relying on the RTA principles, connected the data to the theoretical background of the Self research (as presented in the Introduction); provided the idea of this article, wrote its text and administrated the process of publication.

Rasa Paulauskaitė: created the final version of the interview questions, interviewed the participants, and transcribed the data8.

The Discussion part and Conclusions were discussed among both authors, and mutually approved. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We, the authors, are grateful to the formal and informal reviewers and editors of this article whose valuable comments were helpful in creating its final version.

References

Almonaitienė, J. (2018). Aš ir socialinis kontekstas. Socialinės psichologijos pratybos // Self in a Social Context. Practicum in Social Psychology. ITMC.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2023). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

Brinkmann, S. (2022). Qualitative Interviewing: Conversational Knowledge Through Research Interviews. Oxford University Press.

Corfield, P. (2021). Being Assessed as a Whole Person: A Critique of Identity Politics. Academia Letters, Article 101. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL101

Dhammadinnā, B. (2019). When Womanhood Matters: Sex Essentialization and Pedagogical Dissonance in Buddhist Discourse. Religions of South Asia, 12(3), 274–313. https://doi.org/10.1558/rosa.39890

Dumont, F. (2010). A History of Personality Psychology: Theory, Science, and Research from Hellenism to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Guo, J. (2007). Multiple selves and thematic domains in gender identity: Perspectives from Chinese children’s conflict management styles. In M. Bamberg, A. De Fina, & D. Schiffrin (Eds.), Selves and identities in narrative and discourse (pp. 181–227). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/sin.9.10guo

James, W. (1890). Principles of Psychology. Classics in the History of Psychology. [An internet resource developed by Christopher D. Green.] https://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/Principles/prin10.htm

Kuhn, M. H., & McPartland, T. S. (1954). An empirical investigation of self-attitudes. American Sociological Review, 19(1), 68–76.

Lefkowich, M. (2019). When Women Study Men: Gendered Implications for Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919872388

Lewis, P., Benschop, Y., & Simpson, R. (2017). Postfeminism, Gender and Organization. Gender, Work & Organization, 24(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12175

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the Self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Paulauskaitė, R. (2023). Jaunų suaugusiųjų savojo Aš patyrimas socialinių santykių kontekste / Young adults’ experience of Self in the context of social relationships [Sveikatos psichologijos bakalauro baigiamasis darbas, Lietuvos sveikatos mokslų universitetas / Bachelor’s thesis in health psychology, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences].

Reber, A. S. (1995). Dictionary of psychology (2nd ed.). Penguin Books.

Rens, S. E. (2019). “Who am I, really?” – Self-help consumption and self-identity in the age of technology. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies, 75(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i1.5336

Robins, R. W., Tracy, J. L., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2010). Naturalizing the Self. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 421–447). Guilford Press.

Snyder, M. (1974). Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30(4), 526–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037039

Magnusson, E., & Haavind, H. (2011). Feminist approaches to psychology in the Nordic countries: The fates of feminism in psychology in modern welfare societies. In A. Rutherford, R. Capdevila, V. Undurti, & I. Palmary (Eds.), Handbook of international feminisms: Perspectives on psychology, women, culture, and rights (pp. 151–174). Springer New York.

Wong, P. T. P., Arslan, G., Bowers, V. L., Peacock, E. J., Kjell, O. N. E., Ivtzan, I., & Lomas, T. (2021). Self-Transcendence as a Buffer Against COVID-19 Suffering: The Development and Validation of the Self-Transcendence Measure-B. Frontiers in psychology, 12, Article 648549. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648549

Yu, T. T. F., & Wong, P. T. P. (2024). Existential wellbeing may be of utmost importance to many people. Academia Mental Health and Well-Being, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.20935/MHealthWellB7416

Zahavi, D., & Zelinsky, D. (2024). Experience, Subjectivity, Selfhood: Beyond a Meadian Sociology of the Self. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 54(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12396

1 Quoted directly from his book on the history of personality psychology (Dumont, 2010).

2 We follow the notion of ‘essentialization’ as the “process by which a given entity, in this case ‘woman’, is socially and ideologically constructed as being endowed with a specific, natural and unchangeable, essence” (Dhammadinnā, 2019, p. 275).

3 Post-feminism is a broad umbrella term for explorations of gender in the postmodern stance, which revises and depoliticizes many essential feminist standpoints by connecting it to more general issues of diversity and inclusion and seeking to maintain equilibrium between the two extremes of masculinity and femininity. For wider discussion, see Lewis et al., 2017.

4 More than 106,870of its CrossRef citations were accrued to the date of this article’s final revision.

5 In the Results, the first author intentionally chooses to write in the first person singular.

6 The numbers of transcripts and paragraphs in them are indicated after the quotes, e.g., (3, 64) means transcript 3, paragraph 64.

7 6/6 means that I identified the item in 6 transcripts out of 6, 4/6 – in 4 of 6, etc.

8 It must be said as an acknowledgement that we, the authors of the article, collaborated as a supervisor and a student in the initial phase of this study. I, the first author of this article, found the data collected by Rasa fascinating in the way how the participants reflected on that complicated topic. I highly appreciate Rasa’s input for her interviewing the women with sensitivity and patience on the topic which required mental and emotional efforts from both sides.