Psichologija ISSN 1392-0359 eISSN 2345-0061

2025, vol. 72, pp. 99–117 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Psichol.2025.72.8

Young Males’ Implicit Theories of Marital Relationships: A Thematic Analysis of Socialization Influences

Julija Gaiduk

LCC International University

jgaiduk@lcc.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4170-3557

https://ror.org/01rqcwn02

Jurgita Gogoi

LCC International University

jgogoi@lcc.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4032-1899

https://ror.org/01rqcwn02

Abstract. This study aimed to explore how young males formed implicit theories of a happy marital relationship and identify key socialization influences. Thirteen young adult males studying at a university in Eastern Europe participated in a qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted online or face-to-face asking the participants to describe their ideas about marriage and what influenced them. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed by using the thematic analysis method. The following key socialization influences on the formation of their ideas about marital relationships have been identified: observations of parental and other relationships, culture (own culture and the culture of others), personal characteristics of the participants, and parenting practices of their parents.

Keywords: implicit theories, young adult males, socialization influences, attitudes towards marriage, thematic analysis.

Implicitinės jaunuolių santuokos teorijos ir jas formuojantys veiksniai

Santrauka. Šio tyrimo tikslas buvo suprasti, kaip formuojasi implicitinės laimingos santuokos teorijos ir kokie socializacijos veiksniai tam turi įtakos vaikinų imtyje. Tyrime dalyvavo trylika jaunų suaugusių vyrų, studijuojančių universitete Rytų Europoje. Pasitelktas pusiau struktūruoto interviu metodas nuotoliu ir gyvai. Interviu metu dalyviai dalijosi savo mintimis apie požiūrį į santuoką ir tuo, kas turėjo įtakos tam požiūriui susidaryti. Interviu buvo transkribuoti ir analizuoti taikant teminės analizės metodą. Buvo nustatyti tokie pagrindiniai socializacijos veiksniai, formuojantys dalyvių požiūrį į santuoką: tėvų ir kitų santykių stebėsena, kultūros (savo ir kitų) įtaka, dalyvių asmeninės savybės ir jų tėvų ir motinų auklėjimo pavyzdžių svarba.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: implicitinės teorijos, jauni suaugusieji, socializacijos įtaka, požiūris į santuoką, teminė analizė.

Received: 2024-11-11. Accepted: 2025-05-14.

Copyright © 2025 Julija Gaiduk, Jurgita Gogoi. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Beliefs about the nature and malleability of relationships vary among individuals. Knee (1998) called such beliefs implicit theories of relationships because individuals may not be aware of them (Costa and Faria, 2018). Even though people may not always recognize their underlying beliefs about relationships, these beliefs may shape their behavior (Dweck, 2012). For example, whether someone views key human traits as fixed or changeable can influence how they interact with others, deal with conflicts, and pursue goals, ultimately affecting their interpersonal relationships (Finkel et al., 2007; Kammrath and Dweck, 2006; Knee, 1998).

Reflections and studies on implicit theories include discussions of both the right terminology (implicit theories, lay beliefs, mindsets) and the orthogonality of the beliefs (Lüftenegger and Chen, 2017). Although these theories are often named ‘implicit’, they are often measured and discussed explicitly (Knee et al., 2003). As a result, such terms as mindsets or lay beliefs may be more appropriate terms to be used. However, we continue to use the term implicit theories because this terminology is most commonly used to describe beliefs about the degree of malleability of relationships. Yet, it is important to acknowledge that once such beliefs are expressed, they become somewhat explicit.

Implicit theories are categorized into destiny (or entity) and growth (or incremental) belief systems (Costa and Faria, 2018). Overall, growth and destiny beliefs jointly and independently predict relational thoughts and outcomes and are not necessarily on the opposite sides of the continuum (Knee et al., 2001). People who believe that partners are either meant for each other or not believe in destiny theories. Those who view successful relationships as a product of hard work accept growth theories (Knee, 1998; Lüftenegger and Chen, 2017). Due to such beliefs, destiny theorists often focus on the initial partner compatibility while growth theorists concentrate on overcoming obstacles and growing together (Knee et al., 2003). Destiny and growth beliefs have been found to predict the affective quality of relationships (Knee et al., 2001), commitment (Knee, 1998), conflict and coping strategies (Kammrath and Dweck, 2006; Knee, 1998), and forgiveness (Finkel et al., 2007) as well as moderate the relationships between conflict and commitment (Knee et al., 2004) and perceived partner fit and willingness to forgive (Burnette and Franiuk, 2010). Thus, implicit theories of relationships predict relational behaviors and outcomes.

Although there is evidence that such beliefs are malleable (Allendorf, 2013), literature on the influences on the formation of implicit theories of marriage is scarce. Research on implicit theories of relationships mostly uses quantitative designs, analyzing implicit theories as predictors and moderators in relationships (Franiuk et al., 2002; Knee et al., 2001; Finkel, et al., 2007; Knee et al., 2004). In the few studies of predictors of implicit theories of relationships, personality characteristics (Knee, 1998), thinking styles (Gaiduk, 2015), compassionate goals (Canevello and Crocker, 2010), and preference for romantic movies (Holmes, 2007) were among the factors associated with growth and destiny theories. In addition to the individual participant characteristics and behaviors, we believe that implicit theories of a happy marriage are subject to socialization influences just like many other attitudes and beliefs. Socialization experiences inside and outside one’s family of origin have been studied as predictors of adult relational behaviors and attitudes to varying degrees (Amato and Keith, 1991; Amato and DeBoer, 2001; Franiuk et al., 2002; Hall, 2006; Hall, 2012; Carnelley and Janoff-Bulman, 1992) with implicit theories receiving very limited attention (Hall, 2012; Babarskiene and Gaiduk, 2018). Given the research-proven connection between implicit theories of marriage and relational outcomes and the malleable nature of implicit theories, it is surprising that predictors of and influences on implicit theories of marriage have so far received such modest research attention.

To better understand implicit beliefs about marriage, Babarskiene and Gaiduk (2018) attempted to explore socialization influences on implicit theories of a happy marriage qualitatively, by developing a grounded theory. Parental relationships, individual parental characteristics, observation of other relationships, gender role ideology, education, media, and experiences of own relationships emerged as influences among young adults (primarily women from intact families). In that study, the authors proposed a need to study males. In this study, we attempted to do this. Increasingly, males seem to have been underrepresented in research on relationships. Women seem to be more willing to talk about emotional and family-of-origin issues and participate in research. Yet, females are not the only contributors to relational well-being. Additionally, men and women differ in their adjustment in response to family-of-origin experiences (Diamond and Muller, 2004; Lopez, Campbell, and Watkins Jr., 1986; Akun and Batigun, 2019; Ali, Khaleque, and Rhohner, 2015), use and perception of relational maintenance strategies (Legkauskas and Razniokaite, 2018; Stafford and Canary, 1991) and both personality and behavioral factors predictive of relationship satisfaction (Price, Leavitt, and Allsop, 2021; De Andrade, Wachelke, and Howat-Rodrigues, 2015). Thus, we find the lack of male representation in research concerning, especially in qualitative research as the stories of young males might be different from the stories of young females, as represented in Babarskiene and Gaiduk’s study. A qualitative study with male participants could offer new insights into the dynamics of the mindset or lay belief formation, refining the grounded theory previously developed, as well as opening up opportunities for further qualitative and quantitative research.

Methods

This qualitative study aimed to gain insights into what young male adults believed about marital relationships and to understand different aspects of their implicit theories. The objectives were to identify and analyze the key socialization factors that may influence those beliefs and to examine their impact on the participants’ ideas about marital relationships. Thus, the researchers sought to understand how young adult male students conceptualized marriages, to identify the key influences on the development of their implicit marital theories, and to explore how such beliefs shaped their attitudes and expectations about relationships.

Two researchers gathered data in the spring of 2021 by using semi-structured interviews. Reflexive Thematic Analysis (Reflexive TA) by Braun and Clarke (2022; 2020) was chosen to analyze the participant data. Since the aim was to analyze culturally embedded and socially constructed beliefs of male university students, the rationale for choosing Reflexive thematic analysis was based on the flexibility of the approach and its constructivist epistemology (Braun and Clarke, 2022; 2020). In addition, Reflexive TA emphasizes deep interpretation, reflexivity, and the researcher’s active role in shaping the analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2022; 2020). Themes in Reflexive TA do not emerge out of nowhere; to the contrary, they are a result of the creative, reflexive, and reiterative analysis of data (Braun and Clarke, 2022; 2020). It is also a suitable approach due to the exploratory nature of this study because young males’ ideas about marriage can be explored in detail and with richness. Finally, this method is appropriate for studying under-researched areas, as it helps uncover unique thought processes which may fail to surface in structured quantitative surveys (Braun and Clarke, 2006). As Braun and Clarke (2019) emphasize, the method is not a rigid, step-by-step formula like following a baking recipe, but it is rather a flexible process which values reflexivity, creativity, and strong theoretical engagement.

Participants

Because it is often difficult to recruit male participants for social science studies, we chose young male adults to help understand the intricacies of young male adults’ beliefs about marital relationships. We recruited 13 male participants, aged 18-28, who were interviewed face-to-face and online. The number of participants was determined by data saturation. When the key ideas related to the questions started to repeat, and no more new data was coming, it was decided to stop recruiting more interviewees. Studies confirm that data saturation numbers can vary, and researchers identified samples of 7 to 39 interviews, with an average saturation happening between 10 and 12 interviews (Lu, et al., 2024), while more homogenous samples reach saturation within the range of 9–17 interviews (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022).

The participants came from diverse backgrounds to ensure that the findings show a wide spectrum of socialization influences instead of being limited to a single cultural background. Our participants were students at a liberal arts university in Eastern Europe. They majored in international business, psychology, or linguistics (specializing in English). They came from the following countries: Lithuania, Estonia, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, India, and Georgia. Ten students grew up in intact families, which means that their parents were happily married and living together when the participants were growing up, and three participants came from families with parents who were divorced. We included participants from both intact and divorced families to better understand how different family structures and experiences may influence beliefs about marriage.

The interviews were conducted in English because all the students involved in our research had high proficiency in English, and English was the method of instruction at their university. Informed consent was obtained, explaining the purpose of the study, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of the study. Those who agreed to participate proceeded to semi-structured interviews.

Procedure

Permission to collect data was obtained from the university’s Institutional Review Board (approval number F181). Students were invited to participate in the study through psychology and other classes, university social media posts, or the snowballing technique, when participants referred others to the study. Interviews took place via online platforms (due to the Coronavirus-related restrictions) and face-to-face. The interviews were conducted in English, recorded, transcribed verbatim, coded, and analyzed for themes. Each interview took between 30 minutes and one hour.

During this study, the researchers sought to understand students’ implicit theories about marriage and what influenced such beliefs. After welcoming the participants and creating rapport, the researchers invited the participants to talk about the topic by asking the following question: “Please tell me about your ideas about marriage”. Additional questions explored where those ideas came from, what – in the perception of these students – was a happy marriage, and finally, focused on the examples of marriages which the students shared, including both parental and other marriages, and how marriage was portrayed in films. The interview questions included such questions as: “Would you please talk about a happy marriage you know that is not your parents’ marriage.” “What do you think makes this marriage happy?” “How similar to or different from this marriage would you like your own marriage to be?” “What are your ideas about a happy marriage?” “How likely is a happy marriage for you?” “How would you describe the quality of your parents’ marriage?” “How do the movies you usually watch portray marriage?” “What were the most significant influences on your ideas about marriage?” Thus, during the interviews, the students talked about their beliefs about marriage and the factors that influenced their ideas about marriage.

Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis was used for this research (Braun and Clarke, 2022; 2020). The method was chosen due to its flexibility and suitability, since it provides “robust process guidelines, not rules” (Braun and Clarke, 2022, p. 10). In addition, subjectivity is seen as a resource of the researcher, and reflexivity is the key practice in Reflexive TA (Braun and Clarke, 2022). This approach examines the data and describes the researcher’s role in data analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2020). In this study, the researchers focused on a detailed account of developing implicit theories of marital relationships, making the analysis theoretical and realist (essentialist), and choosing semantic themes. Once the data had been collected, the researchers followed the six phases of the process suggested by Braun and Clarke (2022): familiarizing themselves with the data, data coding, generating initial themes, reviewing the themes, refining, defining and naming the themes, and producing a report. As the themes were named, they were analyzed for reoccurrence, repetition, and forcefulness, as suggested by Scharp (2021).

Researcher’s role and limitations

Trustworthiness or validity is a critical research criterion when doing a qualitative study. Since the researchers had carried out research study about implicit theories before, they had to be mindful of their preconceived ideas about the topic that might affect the study. In addition, since both researchers agreed more with the growth theories, it was important to acknowledge this subjectivity or bias, especially when the participants expressed contrary beliefs. Several techniques were used to deal with the researcher’s bias. First, the researchers were aware of their own biases and used peer debriefing to discuss them (Hays and Singh, 2012). Second, they used reflexivity and carefully documented the data collection process (Creswell and Poth, 2018). It was important to pay attention to the context and nature of the participant stories so that to remain aware of how researcher’s bias might affect interpretation (Creswell and Creswell Báez, 2020). Furthermore, the researchers made sure that the themes came from the participant data, rather than being dictated by the researchers themselves (Silverman, 2005). Finally, the researchers triangulated the study data with the findings in the literature, field notes, and observations in order to have multiple sources of data (Creswell and Creswell Báez, 2020).

Results

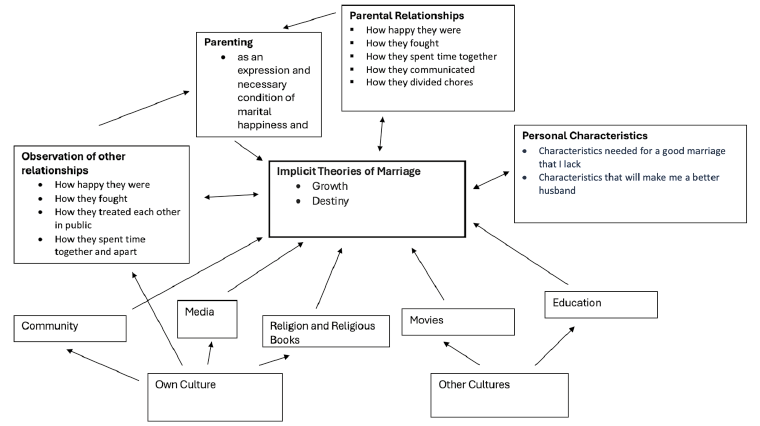

As the participants discussed their implicit theories of happy marital relationships, several factors emerged as socialization influences: observations of parental and other relationships, culture (that of their own and of others), personal characteristics of the participants, and parenting practices of their parents. Figure 1 refers to the socialization influences identified in the study and their interconnections. In addition, the participants expressed examples of both growth and destiny beliefs with more emphasis given to the growth aspect. However, destiny was often a prerequisite for growth ideas about relationships. Thus, both beliefs were voiced, which may suggest that, possibly, both perspectives may co-exist within the participants’ understanding of marriages.

Figure 1

Influences on male young adults’ implicit theories of marriage

Growth vs. destiny beliefs

Growth vs. destiny beliefs

Analysis of the participants’ interview data showed that most participants adhered to the growth theory, focusing on the efforts and work needed to maintain happy marital relationships. Yet, some contributors also expressed some belief in destiny, which was often a prerequisite to putting effort into making marriage work. However, cultural and family influences may be instrumental in influencing this mix of beliefs, considering that students described both happy and unhappy examples of marriages in their lives. In addition, some of the beliefs may have been shaped by broader cultural influences, such as the media and personal experiences they had. For instance, one participant emphasized efforts: “Well, constant, constant, constant trying. We try constantly to make it work. It’s never a thing that you have achieved and now you stay happy forever after.” On the other hand, the following quote is more illustrative of a participant who believed more in the destiny theory: “Before marriage, there’s one person who will match you. That’s why you’re kind of dating with that person, you’re checking if you are ready to live with this person or not.”

At first, the participants’ most ‘automatic’ responses to what makes a happy marriage aligned with the growth approach. After the initial responses, however, ideas representing the destiny theory surfaced as an addition to what makes a marriage happy. Furthermore, the participants’ implicit theories of relationships also emerged as they were discussing socialization influences. Thus, there was a reciprocal interaction between implicit theories and perceptions of agents of socialization. In other words, implicit theories that were expressed explicitly appeared to be not only subject to socialization influences but also influence the perceptions of the agents of socialization. Hence, several of the arrows in Figure 1 are two-way.

Role of parental relationship

One of the crucial influences on young males’ beliefs about relationships appeared to be the relationship between the participants’ parents. As the participants observed how happy or unhappy their parents were, how they quarreled, how they spent time together, how they communicated, and how they divided the chores and agreed on the gender roles, the young men formed their own ideas about what a happy marital relationship could and should be. What the participants’ parents did to build and maintain their marital relationship was as important as the way how they did it.

While growing up, the participants were able to observe and judge whether their parents were happy or not. For those parents who were perceived as happy, the participants expressed genuine admiration, which could be heard verbally and seen nonverbally, as the participants were smiling and using a higher pitch for emphasis. For example, one participant said, “They are just happy together […] They can spend time together and are not hiding anything from each other.” Another participant illustrates the appreciation they have for the parents for making their marriage work: “So, I would rate them as a happy marriage who’ve been through a lot and they’ve been trying, they’ve been learning how to be parents, how to be a married couple and a married couple with a lot of kids.”

On the other hand, for those who saw parental marriage as one involving struggles, the researchers could hear a note of disappointment and critique, especially since these participants also shared examples of other happy marriages: “I think their quality of marriage is okay, fair enough.” Another participant put it this way: “I cannot say that the quality of marriage is very best, I cannot say it’s the very worst [...] It is somewhere in the middle. And they have not always been happy; there have been fights, a lot of fights as I remember.”

The participants also spoke about signs of whether their parents’ marriage was happy or not. One such sign was communication. To illustrate, one student emphasized the ability to maintain harmony: “They are a very good match, because my mother is very agreeable, and my father is not.” Another sign was to be able to talk about problems and solve them, as one participant noted: “Obviously, every family has problems at some point, there is always something to work out, but, at the end of the day, they do still love each other a lot, and they do communicate.” Another participant emphasized the need to ask for the other’s input in marriage: “So, they discuss things, they talk about things […] Even if he wants to start something, he asks my mother what to do […]” Overall, the ability to openly communicate was perceived as important for happiness: “I think they are [happy] because they can talk to each other.” To add, parents who showed respect and tried to understand each other were viewed as happier: “There is always respect in casual communication, simple communication. So, they always understand each other […] Always.” Thus, communication was an important aspect in beliefs about marital relationships.

The frequency, number, and nature of parental conflicts was another marker of marital success that taught young men about happy relationships. Again, we can observe admiration expressed for those parents who rarely had conflicts: “I hardly see them ever fight, I can say that. It is not believable but they live in such harmony.” Lack of explicit arguments was viewed positively: “Until this day, I saw them only once, when they were arguing. Only once. I’m happy that they don’t like conflicting a lot.” In addition, another participant realized that as long as disagreements were managed well, their parents were doing well: “Sometimes they do have different goals or different ideas about parenting, and that will cause tension at some point, but they did a good job.”

On the other hand, even if the participants rated their parents’ relationship positively, they still expressed sadness and disappointment when their parents had many conflicts: “So, I would rate them very high, but still, I cannot close my eyes on the other factors like fights and emotional struggles. It’s troubled but successful.” Even if conflicts were not loud, the participant noted them: “Sometimes they are arguing but in, like, very silent way I would say.” The biggest critique was expressed when the parents had very different positions and disagreed often: “They have strict definitions of their positions. So, they might argue very often on something.”

Another expression of marital happiness and success which the participants observed was how the parents were spending time together. For example, one young man said, “It seems they really loved each other and they […] spent a lot of time together. And I remember they would laugh a lot.” Another participant agreed: “I think they’re happy and because they’re always together and they’re doing some things, like, together. She just stays there and talks with him, just stays close.” Still another young man admired their parents for doing things together: “They have a lot of things in common, and they like to spend time together just talking.”

Division of responsibilities between the parents was also mentioned as something that the participants observed and learned from. For example, “They have defined roles, like who is going to handle what”, or “The main, like, feature of their marriage is they both have equal rights. They are both equal. Of course, they have different responsibilities but still.”

Finally, the fact of either being together or divorced seemed to emerge as a sign of whether the parental marriage was happy or not. When describing intact marriages, the participants stressed the length of the relationship as an indication of marital success. Again, a lot of admiration is expressed for happy marriages that lasted. For example, one participant said, “My parents have been married for 30 years,” while another remarked, “They have been together for a very long time”. When describing unhappy marriages, the participants focused on the fact of divorce as a sign of marital success or lack thereof.

Young males also learned ideas about relationships in conversations with their parents about relationships and the other gender. The participants not only observed parental relationships; they also talked to their parents about marriage. Participants said things like “My dad talked to me,” and “I talk with my mom quite a lot about it, like, marriage life”. Thus, implicit theories of a happy marital relationship were not only obtained through observations but also by direct teaching by the parents. It also seems that the participants’ current implicit theories of marriage colored their recollections of parental relationships and their happiness. For example, when describing growth and destiny ideas, they used parental marriages as illustrations. Thus, the corresponding arrows in Figure 1 are two-way.

Influence of other observed relationships

In describing happy relationships other than their parents’, the participants mentioned marriages of relatives (siblings, grandparents, cousins, aunts, and uncles) and friends. These families served as role models for the participants. As the participants observed how these happily married spouses cooperated, communicated, argued and quarreled, spent time together and apart, treated each other in public, divided the chores, and acted out their gender roles, their own ideas about relationships were being formed. Similarly to the discussions of parental marriages, here, the participants either admired or criticized other marriages.

Happy marriages served as models of communication, acceptance, cooperation, and respect. For example, when describing what characteristics he would like to ‘borrow’ from the observed happy marriages, one participant described, “The chemistry between them, like, understanding each other, knowing each other’s thoughts or positions in very detailed ways […]”. Another participant shared, “They worked at different places but when they were back at home, they would spend time together and go away on weekends. They also made decisions together.”

The participants learned many other positive things by observing other marriages. For instance, one participant admired their relatives’ marriage: “They’re always happy, they always understand each other very well.” Another young adult was also impressed by the way the couple treated each other: “I think they know how to treat each other in public […] If still they don’t agree, they are like, ‘ok, let’s agree to disagree and we’ll talk about it later’.” The ability to maintain friendship and agreement is also admired: “They seem to be very close friends […] They always seem to come to a consensus.” Finally, examples of marriages taught another participant about trust and sharing: “They have a lot of things in common. They share everything. They trust each other.” Thus, the participants indicated that they would like their own marriages to be denoted by similar characteristics.

In addition to serving as role models, the happy marriages which the participants observed gave ideas on what the participants wanted to do differently in their own marriages. For example, when talking about the ways in which they wanted their own marriage to be different, the participants said things like “I don’t like miscommunication”, “maybe, like, more activities which are based together”, “we would spend a little less time together”, or “I think I do not want to always have more patience than my wife” (when speaking of a relative who did seem to have a lot of patience for his wife). Several participants mentioned their own unsuccessful relationships as influences on their ideas about marriage. These relationships seemed to serve as lessons and ‘anti-models’. Again, there seemed to emerge a reciprocal relationship between the participants’ implicit theories of marriage and observations of other relationships.

Influence of culture (that of one’s own and of others)

One of the very strong influences on the participants’ implicit theories about marriage was culture in its several expressions. Such expressions of culture were religion and religious books, community, mass media, the participants’ experiences of their own culture, and exposure to other cultures through education and movies.

As young men spoke of factors affecting their theories of marriage, several participants mentioned religion and religious books. The religions listed were Christianity, Islam and Hinduism. What religion and religious books taught about marriage emerged as an important factor which affected the development of young adults’ beliefs about marriage. For example, “The ideas of our holy books like the Mahabharata and Ramayana”, or “We would go to church, and a common topic in the church is family and marriage”.

The participants also talked about how their culture affected their views on marriage through media and community experiences. Unfortunately, some participants saw many unhappy relationships: “I saw a lot of examples of unhappy marriage in my culture and every time I saw it, I thought that I don’t want my marriage to look like this.” Some participants expressed an opinion that marriage was no longer needed or appreciated: “I think that most of my generation think that marriage is an unnecessary thing in our modern life,” and “The current society is not in favor of marriage.” In addition, observation of how things are done in the community impacted participant beliefs: “[…] Just being an observer in my society in all these years has influenced me.” Some of those influences were related to traditions: “I respect my traditions. I respect the family.” Finally, one of the participants had an especially negative attitude toward marriage, and especially toward married women: “She [mother] had a lot of married friends, married women friends, and since I was in these women circles, I saw and heard a lot of stuff that proved my point that they manipulate men.” To summarize, what the participants saw and heard around them in their immediate communities taught them about the troubled nature of marital relationships, and the participants seemed to be well aware of the influence.

Finally, one’s own culture was not the only cultural influence on implicit theories of marriage. Other cultures were a factor too. The participants spoke of other cultures affecting their ideas through movies and education. All movies described by the participants as influential on their ideas about marriage were foreign to the participants (i.e., these were North American movies). The participants were also students at an international North-American-style university which was located in a country that is foreign to all but one participant.

When talking about movies, several participants stated that movies were not realistic portrayals of relationships. For example, “I certainly believe that what we see in movies about marriage and what we go through in real life is totally different”, and “It’s bulls**t […]; yeah, romantic stuff that women like”. On the other hand, several participants also claimed that movies influenced their ideas about marriage. For example, “Probably the foundation for my position about marriage came from movies […]”, and “I guess, lastly, it would be the influence of movies and TV shows”. In several cases, these conflicting ideas were expressed by the same individual. One quote is especially representative of this tendency:

Influences like movies I think have had a great impact on my perception of marriage…. Sometimes I disagree [with how the movies show relationships] but when I think about it, I think “Hmm, maybe those people who watched this movie, for example, they thought that their marriage will be different also” but they still have the same pattern of marriage.

Thus, the participants recognized the influence of movies while at the same time being skeptical about how accurately the movies portrayed marriage.

Some participants noticed realistic portrayals of marriage in movies, such as the fact that marriage is hard work, and that problems need to be solved together and not ignored, and that partners need to stick together despite difficulties. Thus, movies were acknowledged as an influence on beliefs about marriage both as realistic portrayals of relationships and as illusion-creating fiction.

Education as a way of exposure to a different culture was also recognized as an influence on implicit theories of marriage. For example, “I haven’t had much of psychology but I did have full classes…And it helped me shape the understanding […] that I have now […]” and “Ever since I’ve come into psychology, and also, other subjects, like the Western subjects, have also influenced me as much as my Eastern culture.” In addition to culture and education, beliefs about one’s own personality traits were influential in the participant’s beliefs about marriage.

Influences of the participants’ own characteristics

The participants’ own characteristics seemed to emerge as a factor affecting their views on marriage and future relationships. Since parents came out as one of the major agents of socialization, it could be that parents also modeled and taught how to communicate, what/which traits are important for relationships, and how to regulate emotions in a particular cultural context. Thus, while forming ideas about marriage, the participants not only looked outside for ideas and role models but also employed introspection. The participants spoke of personal qualities that would make them good husbands as well as characteristics that they were lacking. For example, “They say I’m a very difficult person. It requires a long time for people to get used to my way of communication.” Another participant, similarly to his parents, disliked conflicts: “Because there is my character…, like personality, I’m very calm, and I don’t like any conflict.” Still, another participant emphasized independence: “When I’m in a relationship, I think it’s really hard for me to be healthily dependent on the partner, I try to be really individualistic and independent”.

The participants seemed to have an understanding that their characteristics affected their relational outcomes. On the one hand, the way they described their personal characteristics was a reflection of their implicit theories of marriage. To illustrate, if they believed that relationships were a product of work and effort, then, they thought they needed certain characteristics to make them work. On the other hand, personal characteristics influenced the participants’ ideas about happy marital relationships. If they believed they had certain difficult characteristics, they thought that relationships would take much effort.

Role of parenting

When discussing their parents’ and other marriages, the participants repeatedly spoke of their parents’ attitudes towards and involvement with children as signs of happy marriages. For example, “They’re happy because they have children and they have granddaughters and they are happy for that” or “For me, it‘s a kind of bad marriage [speaking of a marriage in which the parents went to work abroad and left the child]. You‘re not supposed to desert a child when he‘s young”, and “They together managed to raise their children well, and also they managed to manage their household very well”. All the participants said something about having or raising children as indicators of marital success and happiness. It seems that, in the participants’ views, parenting success was an integral part of marital success. Parenting was described as both an expression and a prerequisite for a happy marriage.

Discussion

A finding that stood out in this study was the power which the participants attributed to the parenting practices of the couples they had observed. When describing happy marriages, all the participants spoke about parenting. The answers ranged from having children as one of the most important meanings of marriage to how much time parents spend with children as being an indicator of happiness in a marriage. Parenting, thus, was a reason and a measure of marital success.

One could assume that the participants attributed such great power to parenting because of egocentrism. It is possible that they were not able to remove themselves from their memories of parental marriages, and the way how they felt with their parents colored their perceptions of how happy their parents’ marriages were. While this might have been the case, most participants also mentioned parenting when describing happy marriages that were not their parents’. It would be a stretch to say that the participants’ memories of other happy relationships were colored by their feelings in relationships with their parents. It appears that the young males in the study expressed awareness of the marriage-parenting spillover documented by various studies (Kuo and Johnson, 2021; Vafaeenejad et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2019; Erel and Burman, 1995). They also seemed to appreciate the importance of children and the effect that parenting has on marital relationships, as documented by Noya et al. (2020), Kowal et al. (2021), Chiş (2022) and others. Parenting and marital satisfaction seem to be reciprocally related, and our participants seemed to be well aware of it.

Intriguingly, this theme did not appear among female participants in an earlier similar study of a predominantly female sample (Babarskiene and Gaiduk, 2018). It seems that, for young women in that study, parenting was neither an indication of marital success nor necessary for a happy marriage in contrast to the males in this study. There is some evidence for the different marriage-parenting spillover patterns for men and women (Kopystynska et al., 2020; Kuo and Johnson, 2021). Evidence, however, is conflicting (Kuo and Johnson, 2021; Erel and Burman, 1995) and not conclusive enough to explain our findings. More research is needed to explore the differential effects of attitudes towards children on the implicit theories of marriage developed by young men and young women.

Another intriguing difference between young women and young men in the context of Babarskiene and Gaiduk’s (2018) research and the current study is in the area of the gender role ideology. The gender role ideology themes circled around equality in both studies. However, for women in the earlier study (Babarskiene and Gaiduk, 2018), the focus was on being independent, taking care of and providing for themselves. For men in both studies, gender role ideas centered on equality and listening to the wife as well as the distribution of chores. While for women in the study mentioned above, the gender role ideology was an important issue which affected the participants’ implicit theories of marriage, yet, among young men in our study, it only received a brief mention when equality was cited as a sign of a happy marriage. Further investigation into the differential influences of ideas around the gender on relational attitudes and dynamics for different genders is in order.

Consistent with previous research (Babarskiene and Gaiduk, 2018), observations of parental relationships emerged as an important socialization influence on young adults’ implicit theories of marriage. This was not a surprising finding as many studies have provided evidence for the relationship between parental marriage quality and young adults’ attitudes toward marriage (Cunningham and Thornton, 2006) and intergenerational transmission of attitudes (Willoughby et al., 2020; Willoughby et al., 2012; Kapinus, 2004) and relational outcomes (Perren et al., 2005; Wolfinger, 2003; Amato and DeBoer, 2001). Thus, parental marriage remains a strong influence on young adults’ implicit theories of marriage.

Another interesting finding of this study was the influence of culture in its different expressions. The participants’ own culture, and also other cultures seemed to affect young males’ implicit theories of marriage. While growing up, children learn about their culture through interactions with and observations of other members of the same culture. Community, media, and religion were mentioned as expressions of own culture which are influential for the formation of implicit theories of marriage. As marital relationships are important elements of cultures, it is not surprising that community, media, and religions as expressions of cultures have much to say about marriage. They convey the messages clearly and overtly, and people internalize them and are aware of the process of internalization.

In addition to their own culture, the participants mentioned the influence of other cultures. Education and movies were mentioned as expressions of cultures other than the participants’ own culture that influenced the formation of implicit theories of marriage. The movies that the participants mentioned were North American by origin, which is the culture that none of the participants belonged to. In addition, they were receiving education from a North-American-style university. Consistent with Babarskiene & Gaiduk (2018), the participants were aware of both overt and covert influences of movies on the formation of their beliefs about marriage. Both studies seem to support Appel and Richter’s (2007) claim that fictional framing influences ideas about marriage, and the influence seems to be long-term. Additionally, the participants’ skepticism about the accuracy of happy marital relationship portrayals in movies and yet awareness of the influence of movies on their beliefs points both to cognitive dissonance and the implicit nature of beliefs, even those expressed explicitly. This cognitive dissonance is an intriguing area for further research.

Interestingly, the theme of cultural influences seemed to be more prominent for the young males in this study than for the predominantly female sample of Babarskiene and Gaiduk’s (2018) earlier study. It is especially true for religion and one’s own culture as these themes did not emerge in Babarskiene and Gaiduk’s study. More research is needed in order to find out if this was an accidental difference or if men are indeed more aware of and susceptible to the influences of their immediate culture than women.

The theme of personal characteristics having a reciprocal relationship with implicit theories of a happy marriage was not a surprising finding. It echoed the findings of Babarskiene and Gaiduk (2018). The findings are consistent with Bandura’s (1978) reciprocal determinism and self-efficacy theories (Bandura, 1997). What people think of themselves influences and is influenced by behaviors and attitudes (such as implicit theories of marriage). Additionally, this theme may have emerged as a result of upward social comparison (which may affect self-evaluation both positively and negatively (Collins, 1996)) since it emerged in answers to questions like “How likely is a happy marriage for you?” after the participants had discussed happy marriages known to them.

Observations of other marriages as an influence on one’s own ideas about marriage was another finding of our study that was not surprising. It is consistent with both the social-cognitive theory and Babarskiene and Gaiduk’s (2018) grounded theory developed in a similar study. Interestingly, although role models are an important element of the social-cognitive theory, scientific studies on non-parental role models of marriages and their connections to attitudes toward marriage were not found. The way(s) how social comparison and social learning mechanisms work in the relationship between observations of other marriages and views on marriage is an intriguing question for further research.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. The greatest concern is in the sample. Though we were able to study males (which is a sample that is often difficult to collect), we would have liked to have more males from divorced families. Additionally, though our participants were of similar age and all studied in English at a university in Europe, there was much heterogeneity in our sample. However, since the study was exploratory, trying to identify key socialization influences on the ideas about marriage among a male population, a homogenous sample was not the goal. Hopefully, further studies could have groups of participants from specific cultures studied both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Implications

This study is not unique in implicating the need for parents to protect and sustain their positive relationship in order (among many other reasons) to help their children develop more positive and working attitudes toward marriage. In this, our study is simply another voice in the choir. An implication for counselors would be the importance and utility of exploring issues learned by their clients while observing other relationships. Such explorations could increase self-awareness and foster the development of more productive implicit theories. Additionally, education about relationship messages portrayed in movies and more productive ideas about marriage would be beneficial for young adults and even teenagers. Finally, exploring personal characteristics in counseling and education to raise self-awareness and boost self-efficacy about relationships could help young adults develop more productive implicit theories of marriage, incorporating growth and destiny beliefs.

Areas for further study

For further research, it would be worthwhile to study the differences between young men and women in viewing parenting as a prerequisite or a sign of a happy marriage. Reasons for and consequences of the differences could be explored. Another area for further study is specific ways in which observation of other marriages affects young adults’ attitudes toward marriage. Much research has already been conducted on the correlates and influences of parental relationships on offspring’s attitudes toward marriage, while the mechanisms at play when other relationships are being observed (including one’s own relationships) are not known. Additionally, since culture appeared to bear influence on implicit theories of marriage, it would be relevant to analyze specific cultural influences on attitudes toward marriage quantitatively. Further, cognitive dissonance processes involved in being exposed to fiction media are an intriguing field of study. Finally, it would be interesting to explore how young males’ attitudes toward marriage are formed in divorced families.

Author contributions

Julija Gaiduk: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft, writing - review and editing, visualization.

Jurgita Gogoi: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing original draft, writing review and editing.

References

Akün, E., & Batıgün, A. D. (2019). Negative symptoms and recollections of parental rejection: The moderating roles of psychological maladjustment and gender. Psychiatry Research, 275, 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.042

Allendorf, K. (2013). Schemas of marital change: From arranged marriages to eloping for love. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(2), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12003

Ali, S., Khaleque, R., & Rhohner, R. P. (2015). Pancultural gender differences in the relation between perceived parental acceptance and psychological adjustment of children and adult offspring: A meta-analytic review of worldwide research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(8), 1059–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115597754

Amato, P., & DeBoer, D. (2001). The transmission of marital instability across generations: Relationship skills or commitment to marriage? Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1038–1054. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0701_3

Amato, P., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and adult wellbeing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53, 43–58.

Andrade, A., Wachelke, J., & Howat-Rodrigues, A. B. C. (2015). Relationship satisfaction in young adults: Gender and love dimensions. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 9(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.5964/ijpr.v9i1.157

Appel, M., & Richter, T. (2007). Persuasive effects of fictional narratives increase over time. Media Psychology, 10(1), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701301194

Babarskiene, J., & Gaiduk, J. (2018). Implicit theories of marital relationships: A grounded theory of socialization influences. Marriage & Family Review, 54(4), 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2017.1347547

Bandura, A. (1978). The self system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33(4), 344–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.33.4.344

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy. Harvard Mental Health Letter, 13(9), 4–6.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Burnette, J. L., & Franiuk, R. (2010). Individual differences in implicit theories of relationships and partner fit: Predicting forgiveness in developing relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(2), 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.09.011

Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2010). Changing relationship growth belief: Intrapersonal and interpersonal consequences of compassionate goals. Personal Relationships, 18(3), 370–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01296.x

Carnelley, K., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Optimism about love relationships: General versus specific lessons from one’s personal experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407592091001

Chiş, R. M. (2022). A Critical review of the literature on the relationships between personality variables, parenting and marital satisfaction. Postmodern Openings, 13(1), 17–46. https://doi.org/10.18662/po/13.1/383

Collins, R. L. (1996). For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51

Costa, A., & Faria, L. (2018). Implicit theories of intelligence and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00829

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell Báez, J. (2020). 30 essential skills for the qualitative researcher (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage Publications.

Cunningham, M., & Thornton, A. (2006). The influence of parents’ marital quality on adult children’s attitudes toward marriage and its alternatives: Main and moderating effects. Demography, 43(4), 659–672. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0031

Diamond, T., & Muller, R. T. (2004). The relationship between witnessing parental conflict during childhood and later psychological adjustment among university students: Disentangling confounding risk factors. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 36(4), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087238

Dweck, C. S. (2012). Implicit theories. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 43–61). Sage.

Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 108–132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108

Finkel, E. J., Burnette, J. L., & Scissors, L. E. (2007). Vengefully ever after: Destiny beliefs, state attachment anxiety, and forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 871–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.871

Franiuk, R., Cohen, D., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2002). Implicit theories of relationships: Implications for relationship satisfaction and longevity. Personal Relationships, 9(4), 345–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.09401

Gaiduk, J. (2015). Thinking styles and parental relationship as predictors of implicit theories of relationships [Doctoral dissertation, Regent University].

Gao, M., Du, H., Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (2019). Marital conflict behaviors and parenting: Dyadic links over time. Family Relations, 68(1), 135–149. https://doi-org.libproxy.lcc.lt/10.1111/fare.12322

Hall, S. S. (2006). Parental predictors of young adults’ belief systems of marriage. Current Research in Social Psychology, 12(2), 22–37.

Hall, S. S. (2012). Implicit theories of the marital institution. Marriage & Family Review, 48(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2011.619298

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings. Guilford Press.

Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, Article 114523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Holmes, B. M. (2007). In search of my “one and only”: Romance-oriented media and beliefs in romantic relationships destiny. Electronic Journal of Communication, 17(3-4). http://www.cios.org/EJCPUBLIC/017/3/01735.HTML

Kammrath, L. K., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Voice in conflict: Preferred conflict strategies among incremental and entity theorists. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(11), 1497–1508. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206291476

Kapinus, C. A. (2004). The effect of parents’ attitudes toward divorce on offspring’s attitudes: Gender and parental divorce as mediating factors. Journal of Family Issues, 25(1), 112–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X02250860

Knee, C. R. (1998). Implicit theories of relationships: Assessment and prediction of romantic relationship initiation, coping, and longevity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.360

Knee, C. R., Nanayakkara, A., Vietor, N. A., Neighbors, C., & Patrick, H. (2001). Implicit theories of relationships: Who cares if romantic partners are less than ideal? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 808–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201277004

Knee, C. R., Patrick, H., Vietor, N. A., & Neighbors, C. (2004). Implicit theories of relationships: Moderators of the link between conflict and commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(5), 617–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203262853

Knee, C. R., Patrick, H., & Lonsbary, C. (2003). Implicit theories of relationships: Orientations toward evaluation and cultivation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0701_3

Kopystynska, O., Barnett, M. A., & Curran, M. A. (2020). Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, parenting, and coparenting alliance. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(4), 414–424. http://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000606

Kowal, M., Groyecka-Bernard, A., Kochan-Wójcik, M., & Sorokowski, P. (2021) When and how does the number of children affect marital satisfaction? An international survey. PLoS ONE, 16(4), Article e0249516. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249516

Kuo, P. X., & Johnsnon, V. J. (2021). Whose parenting stress is more vulnerable to marital dissatisfaction? A within-couple approach examining gender, cognitive reappraisal, and parental identity. Family Processes, 60(4), 1470–1487. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12642

Legkauskas, V., & Pazniokaitė, G. (2018). Gender differences in relationship maintenance behaviors and relationship satisfaction. Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach, 8(2), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.21277/sw.v2i8.367

Lopez, F. G., Campbell, V. L., & Watkins Jr., C. E. (1986). Depression, psychological separation, and college adjustment: An investigation of sex differences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(1), 52–56.

Lu, Y., Jian, M., Muhamad, N. S. A., & Hizam-Hanafiah, M. (2024). Data saturation in qualitative research: A literature review in entrepreneurship study from 2004–2024. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(12), Article 9753. https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v8i12.9753

Lüftenegger, M., & Chen, J. A. (2017). Conceptual issues and assessment of implicit theories. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 225(2), 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000286

Noya, A., Taubman – Ben-Aria, O., Moragb, I., & Kuintb, J. (2020). Intergenerational relations, circumstances, and changes in mothers’ marital quality during two years following childbirth. Health Care for Women International, 41(1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1590358

Perren, S., Von Will, A., Burgen, D., Simoni, H., & Von Klitzing, K. (2005). Intergenerational transmission of marital quality across the transition to parenthood. Family Process, 44(4), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00071.x

Price, A. A., Chelom, E., Leavitt, C. E., & Allsop, D. B. (2021). How gender differences in emotional cutoff and reactivity influence couple’s sexual and relational outcomes. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 71(1), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1800541

Scharp, K. M. (2021). Thematic co-occurrence analysis: Advancing a theory and qualitative method to illuminate ambivalent experiences. The Journal of communication, 71(4), 545–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqab015

Silverman, D. (2005). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Stafford, L., & Canary, D. J. (1991). Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender and relational characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8(2), 217–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407591082004

Vafaeenejad, Z., Elyasi, F., Moosazadeh, M., & Shahhosseini, Z. (2020). The predictive role of marital satisfaction on the parental agreement. Nursing Open, 7(6), 1840–1845. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.571

Willoughby, B. J., Carroll, J. S., Vitas, J. M., & Hill, L. M. (2012). “When are you getting married?” The intergenerational transmission of attitudes regarding marital timing and marital importance. Journal of Family Issues, 33(2), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11408695

Willoughby, B. J., James, S., Marsee, I., Memmott, M., & Dennison, R. P. (2020). “I’m scared because divorce sucks”: Parental divorce and the marital paradigms of emerging adults. Journal of Family Issues, 41(6), 711–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19880933

Wolfinger, N. H. (2003). Parental divorce and offspring marriage: Early or late? Social Forces, 82(1), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0108