Psichologija ISSN 1392-0359 eISSN 2345-0061

2025, vol. 73, pp. 85–94 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Psichol.2025.73.6

Psychological Distance Effects on Believing in a Just-World and Rational-Nonrational Defense Strategy Use in the Context of the Conflicts in Ukraine and Myanmar

Justinas Zokas

Vilnius University

justinaszok@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-9340-673X

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Kristina Vanagaitė

Vilnius University

kristina.vanagaite@fsf.vu.lt

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6940-647X

https://ror.org/03nadee84

Summary. People have a basic need to believe in a world that is just, that is, a place where benevolence is rewarded, and misdemeanors are punished. Experiences of unfair events (e.g., a war) bring doubts about the justness of the world leading to attempts to re-establish righteousness by objective or subjective means (defense strategies). Importantly, it has become fairly common to encounter events which are not limited to the current place, and which affect people whom one may not otherwise acknowledge because contemporary media helps to discover what is happening beyond immediate human perception. This separation between a person and a given scenario is described as psychological distance. In order to inspect how psychological distance influences beliefs in a just-world and its defense, an experimental study was conducted on 60 participants. After random assignment to proximal and distal psychological distance groups, the subjects were exposed to just-world altering news articles about war. Before and after the articles, the just-world belief was evaluated, and defensive reactions to the stimuli were assessed. The results demonstrate that people perceive psychologically proximal and distal stimuli as similarly offensive to just-world beliefs. In addition, people are prone to use more rational strategies to defend justice in psychologically close conditions, and more nonrational strategies when events are psychologically distant. This study provides insights into psychological distance effects on just-world perception and defense strategies, which may have an impact on forming a positive or negative view towards victims.

Keywords: just-world belief, psychological distance, just-world defense strategies, victim perception.

Psichologinio atstumo poveikis tikėjimui pasaulio teisingumu bei racionalių-neracionalių gynybos strategijų naudojimui konfliktų Ukrainoje ir Mianmare kontekste

Santrauka. Žmonės turi bazinį poreikį tikėti, kad pasaulis yra teisinga vieta, kurioje geranoriški poelgiai yra apdovanojami, o nusižengimai yra baudžiami. Susidūrus su įvykiais, kurie vertinami kaip neteisingi (pvz., karas), pradedama abejoti pasaulio teisingumu, todėl stengiamasi jį atstatyti taikant objektyvias arba subjektyvias priemones (gynybines strategijas). Svarbu tai, kad dažnai galima susidurti su įvykiais, neapsiribojančiais vien tuometine vieta ir paveikiančiais asmenis, kuriems įprastai neskiriama daug dėmesio, nes šiuolaikinė žiniasklaida padeda sužinoti apie tai, kas vyksta toli už tiesioginių žmogaus suvokimo ribų. Šis tarpas, skiriantis žmogų nuo sutinkamos informacijos, vadinamas psichologiniu atstumu. Siekiant ištirti psichologinio atstumo įtaką tikėjimui, kad pasaulis teisingas, bei šio požiūrio gynybai, atliktas eksperimentinis tyrimas su ٦٠ dalyvių. Atsitiktinai suskirsčius į artimo ir tolimo psichologinio atstumo grupes, buvo pateikiami pasaulio teisingumą neigiantys žiniasklaidos straipsniai apie tam tikrą karinį konfliktą. Prieš ir po straipsnių buvo išmatuotas tikėjimas pasaulio teisingumu ir įvertintos gynybinės reakcijos į stimulus. Rezultatai parodė, jog žmonės tiek psichologiškai artimus, tiek tolimus stimulus suvokia kaip panašiai pažeidžiančius pasaulio teisingumą. Taip pat žmonės yra labiau linkę naudoti racionalias strategijas teisingumui apginti psichologiškai artimesnėse sąlygose bei naudoti daugiau neracionalias strategijas, kai įvykiai randasi psichologiškai toli. Šis tyrimas suteikia įžvalgų, jog psichologinis atstumas gali daryti įtaką pasaulio teisingumo suvokimui bei gynybos strategijų pasirinkimui, kurios nuteikia teigiamam arba neigiamam požiūriui į neteisingumo aukas.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: tikėjimas pasaulio teisingumu, psichologinis atstumas, pasaulio teisingumo gynybos strategijos, aukų vertinimas.

Received: 2025-03-10. Accepted: 2025-06-27.

Copyright © 2025 Justinas Zokas, Kristina Vanagaitė. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Humans have a fundamental need to believe that the world around them is just (Lerner, 1980). This need drives people to construe their surroundings based on principles of deservingness, i.e., that people get what they deserve. Given the current state of global crises, the belief that justice principles will eventually balance out the good and the evil can serve as an important coping mechanism. However, the world at times tends to contradict justice – as can be seen in many wars where innocent lives are taken at random. If just-world beliefs are meant to help an individual make sense of their surroundings, then messages about military conflicts should induce a certain dissonance: why do people suffer undeservingly?

There is an underlying need to believe that surroundings operate in a just way, and it is not simply an explicit worldview (Lerner, 1980). That is, challenges to justice arise, and certain ways to maintain justice must be implemented. These are called just-world defense strategies (Hafer & Rubel, 2015). A person may retain justice by using rational or nonrational methods (Lerner, 1980). Rational strategies consist of acknowledgment of an injustice and a conscious effort to alleviate the damage (e.g., financial compensation). Contrarily, nonrational strategies are used to construe events in a way that injustices are not acknowledged but still fit according to deservingness. Since nonrational strategies overlook injustices, they can come up in an asocial form (e.g., victim blaming). Victim blaming has garnered much attention in research (e.g., Russell & Hand, 2017), but other strategies have been somewhat overlooked. There are many forms of nonrational strategies, including, but not limited to, physical distancing, psychological distancing, injustice minimization, making meaning of suffering, and anticipatory punishment (Lerner, 1980; Hafer & Rubel, 2015), as well as weighing of suffering. A few of them require more detailed explanation. Physical distancing describes a person’s attempts to distance themselves from the situation to make it less salient (e.g., by describing the situation as happening ‘somewhere far away’ and therefore less important). Hafer and Rubel (2015) refer to psychological distancing as a strategy, however, in the context of this paper, it was renamed to ‘social distancing’ in order to avoid confusion with the psychological distance construct described below. This strategy encompasses framing the situation to make it dissimilar to the person (e.g., by describing the characters involved as distinctly different than the person themselves is). Furthermore, the weighing of suffering is conceptualized as a form of minimization, where people try to alleviate the injustice by comparing it to people who ‘have it worse off’. A theoretical overview of rational versus nonrational strategy choice predictors is provided in a paper by Hafer and Gosse (2010), but empirical studies analyzing defense strategies are still scarce.

To expand the literature, overlap with other theories must be accounted for. In this case, psychological distancing effects are relevant. Current global crises (such as the war in Ukraine) can bring into question just-world beliefs in an indirect manner, as, in many instances, people only hear about inequities but do not experience them firsthand. In such cases, a certain gap between the momentary person and an injustice arises. Liberman and Trope (2014) conceptualize this gap as psychological distance. Each person has an egocentric starting point, from which, psychological distance can be considered null, however, when events reach out farther than the immediate position of the person, representations appear to differ. Liberman and Trope (2014) postulated the Construal Level Theory, according to which, psychologically proximal conditions become concrete representations, while distal situations are coded in abstract cognitions. Explanations of psychological distance effects through abstraction mechanisms have been quite robust (Soderberg et al., 2015). Moreover, four dimensions of psychological distance have been postulated: spatial, temporal, social, and hypothetical (Liberman & Trope, 2014). Spatial distance describes the intervening physical space between the person and the situation, temporal distance is concerned with closeness in time, social distance describes potential similarity between the person and the target, whereas hypotheticality sets the distance of a situation based on how plausible it appears to be. Each dimension provides cues about psychological distance overall, and they seem to be highly intercorrelated (Fiedler et al., 2012). However, the relationship between the dimensions is not symmetrical, as spatial distance cues lead to inferences about the other three dimensions, but not the other way around (Zhang & Wang, 2009). In this way, spatial distance can be understood as the central dimension in understanding psychological distance because changes in physical distance tend to influence the other dimensions as well. In the case of currently ongoing events, manipulations of temporal and hypothetical distance appear unsuitable and therefore spatial and social distance will garner most attention in this paper.

Manipulations of psychological distance may affect how a person rates justness of the world, and which strategies are chosen to maintain it that way. Some studies link psychological distancing effects to spontaneous justice inference (Zhang et al., 2022) and salience of justice evaluations (Eyal et al., 2008) by showing that distal conditions can activate related justice beliefs. Other studies demonstrate that social proximity can appear more offensive to just-world judgements (Modesto & Pilati, 2017). Certain authors point out that the relationship between psychological distance and justice is not unanimous, as it can be argued that not only closer but also further conditions influence righteousness judgments (Alper, 2020). As such, studies on the relationship between psychological distance and justice interpretations seem to be unclear. What is more, other research shows that temporal distance (Warner et al., 2012), as well as social distance (Cao & Decker, 2015), can have an impact on the defense strategy choice, in this way demonstrating that psychological distance can play a significant role in rational-nonrational strategy use differentiation. Overall, the currently existing research points towards psychological distance as an important construct when evaluating and defending just-world beliefs. However, the research is limited, especially for analysis of defense strategies.

The aim of the study is to determine the effect of psychological distance on belief in a just-world and how it is defended.

The following hypotheses have been raised:

1. Psychologically distal condition, when compared to proximal, will reduce just-world belief more distinctively.

2. Psychologically proximal condition will prompt more rational defense strategies.

3. Psychologically distal condition will prompt more nonrational defense strategies.

Methodology

Participants

60 participants were included (23 male), age mean – 28.19 years (SD = 8.8); two participants did not disclose their age. The subjects were randomly assigned into two equal groups which did not differ by gender, age, religiosity or education, as checked with the χ2 homogeneity test (p > 0.05). Recruitment was established via convenience and snowball sampling – specifically, the study was sent to available participants, while sharing with acquaintances was encouraged.

Stimuli

Four third-year psychology Bachelor’s students were recruited by using convenient sampling to establish stimuli appropriateness. After a brief theoretical explanation of psychological distance, the subjects rated psychological distance of news articles (21 excerpts overall). The article inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) a non-fictional issue had to be described; 2) the article had to be from a trustworthy Lithuanian news platform and written in Lithuanian; 3) the articles had to describe ongoing events; 4) the content had to be concerned with severe consequences for civilians. These articles described humanitarian issues in current-day Haiti, Ukraine, Sudan, Gaza Strip, and Myanmar. For illustration purposes, images, locations, and national flags (except for Gaza Strip) were shown next to each article. Each region had four articles associated with it (except for Ukraine having an extra article for social distance manipulation). The texts were slightly modified in order to focus on study concerns, the keywords were written in bold, the articles came with sources, and dates of publication. The raters had to evaluate how physically and temporally close the events appeared, as well as to identify whether the events seemed to affect their social group or themselves, and whether the messages appeared hypothetically real or not. In the end, the participants provided their judgement on psychological distance overall. Questions had to be answered in a five-point Likert scale. The raters agreed that the closest situation was that of Ukraine, whereas the furthest was that of Myanmar (Table 1). Not all the conflicts mentioned have the same sociopolitical context, but, in the case of civilian suffering, they were considered equal.

Table 1

Stimuli evaluation results showing rating means

|

Haiti |

Ukraine |

Sudan |

Gaza Strip |

Myanmar |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Physical distance* |

2.00 |

4.25 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

1.50 |

|

Temporal distance |

4.00 |

5.00 |

3.75 |

5.00 |

3.75 |

|

Social group* |

1.50 |

4.00 |

1.50 |

2.75 |

1.50 |

|

Social identification* |

1.50 |

4.75 |

1.25 |

2.75 |

1.25 |

|

Hypotheticality |

3.75 |

4.75 |

4.25 |

4.50 |

4.00 |

|

Psychological distance overall* |

2.00 |

4.75 |

1.75 |

3.25 |

1.50 |

Note. * indicates which variables were purposefully manipulated when using the articles. The highest ratings are bolded, the lowest ratings are italicized.

Inter-rater reliability was tested by using Two-way random Intraclass Correlation. The criterion showed excellent reliability (ICC = 0.93, 95% CI [0.87, 0.97], p < 0.001).

The further study used these psychological distance news stimuli (about Ukraine and Myanmar), a collection of questions from just-world questionnaires translated to Lithuanian, and just-world defense strategy statements.

Just-world belief

Just-world belief statements were combined from different questionnaires to distinctly measure personal and global dimensions, as this may be important when psychological distance manipulations occur. Personal belief in a just-world mainly concerns the individuals’ position when making justice judgements, while global beliefs reflect the world as a whole. Three items were taken from the Global Belief in a Just-world Scale (“I feel that rewards and punishments are fairly given”, “I feel that people earn the rewards and punishments they get”, and “I basically feel that the world is a fair place”) (Reich & Wang, 2015), two items were sourced from the Personal Belief in a Just-world Scale (“I am usually treated fairly”, and “I believe that most of the things that happen in my life are fair”) (Dalbert, 1999). The items were chosen to encourage the least amount of overlap between the statements themselves and defense strategies (e.g., “I feel that people who meet with misfortune have brought it on themselves” was excluded because of similarity with victim blaming), as well as for briefness. The Cronbach’s alpha test showed good reliability scores (α = 0.84). For the structural validity of the questions, exploratory factor analysis was conducted. By using Principal Component Analysis with the Varimax rotation method, the model showed a statistically significant two-factor solution explaining 76.8% of dispersion (KMO = 0.78, χ2 = 135.53, df = 10, p < 0.001). The statements were grouped into factors resembling global and personal belief in a just-world (minimal weight 0.58).

Defense strategies

Defense strategies were created for the study by the researchers in accordance with the context of the stimuli, based on the strategies defined by Lerner (1980), as well as Hafer and Rubel (2015). The statements were laid out from the perspective of other people to reduce social desirability based on discernable face validity. From the rational strategies, financial support, and direct support were evaluated. The participants had to rate their intentions to contribute on a six-point Likert scale. Rational strategy items showed moderate internal reliability (α = 0.65), however, due to there being only two items, this score was considered sufficient. The nonrational strategies consisted of physical distancing, social distancing, victim blaming, minimization of suffering, weighing of suffering, ascribing meaning to suffering, and anticipatory perpetrator punishment. The participants had to rate each statement on a six-point Likert scale, while only the edges of the dimensions were described. Nonrational strategy items showed good reliability scores (α = 0.81). Moreover, exploratory factor analysis using Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation method showed a statistically significant two-factor solution explaining 63.4% of dispersion (KMO = 0.79, χ2 = 235.94, df = 36, p < 0.001). The items were grouped into factors resembling rational and nonrational defense strategy groups (the minimal weight for rational strategies was 0.81, while the smallest weight coefficients for nonrational strategies were 0.4 for Anticipatory punishment and 0.57 for Physical distancing).

The participants started by completing the just-world belief items, after which, the articles were presented. After reading, just-world items were answered once more, and defense strategies were evaluated. Lastly, the participants were questioned about the demographic variables.

Data analysis

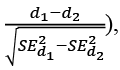

The IBM SPSS Statistics 27 software was used for statistical analysis. To compare just-world scale scores among the groups, the Paired-Samples T Test was used (with normality assumptions verified). Concerning the defense strategy comparison, the Mann-Whitney U Test was utilized. Testing for prior knowledge about the situation in the conditions, a χ2 test and ANCOVA analysis was conducted (assumptions about normality, homoscedasticity, linearity, and homogeneity were verified). Effect sizes for t tests were analyzed via Cohen’s d Point Estimates. In the Paired sample t test, Difference in Cohen’s d was calculated using a z measurement (z =  ), with the value of p calculated from a standard normal distribution table.

), with the value of p calculated from a standard normal distribution table.

Figure 1

Just-world belief scores before and after exposure to just-world threatening information in psychological distance conditions

![[Figure 1 shows the differences in just-world belief scores between the proximal and distal condition. The figure is divided vertically into two parts, with the left part showing distal scores, while the right part illustrates proximal scores. The x-axis is divided into pretest and posttest, while the y-axis shows just-world acceptance scores ranging from 0 to 25 in increments of 5.

Three different markings are used to indicate the score sum, the global just-world belief, and the personal just-world belief. Statistically significant scores, where p is less than one one-hundredth, are shown as continuous lines, while statistically insignificant scores, where p is bigger than five one-hundredths, are shown in dashed lines.

The figure shows that both the distal and the proximal condition showed statistically significant differences in global just-world belief, and summed the scores before and after the stimuli. Personal just-world belief did not show statistically significant differences. In the figure, it can be seen that summed scores in the distal condition dropped from approximately 20 to approximately 18, while, in the distal condition, this drop was from approximately 20 to approximately 16, which indicates a steeper slope. The same can be seen in global just-world belief: the distal condition dropped from approximately 10 to 9, while the proximal condition dropped from approximately 10 to approximately 7. Personal just-world belief was seen as an almost straight line, where no difference can be visually identified.]](https://www.zurnalai.vu.lt/psichologija/article/download/39229/version/35371/40520/124381/justis1.png)

Note. BJW – Belief in a Just-world

Results

The results indicate that both distancing conditions had statistically significant effects on just-world beliefs (Figure 1). It is of note that both conditions showed differences in just-world acceptance scores before and after the stimuli (proximal: t = 3.75, df = 29, p < 0.001, d = 0.69; distal: t = 3.04, df = 29, p < 0.01, d = 0.56), although statistical analysis of the effect sizes did not indicate a statistically significant difference between the conditions (z = 0.46, p = 0.64). Differences were mainly seen in global just-world belief (proximal: t = 4, df = 29, p < 0.001, d = 0.73 vs. distal: t = 2.8, df = 29, p < 0.01, d = 0.52), but not personal just-world belief (p > 0.05). Analysis of the global just-world belief impact showed that the conditions did not differ by the size of effect (z = 0.75, p = 0.45).

Moreover, the groups used different amounts of summed defense strategies, where the proximal condition tended to engage in more defense (Mean RankProximal = 35, Mean RankDistal = 26, U = 585, Z = 2, p < 0.05). Figure 2 shows differences in rational and nonrational strategy use. The proximal group put more effort into rational strategies (Mean RankProximal = 40.43, Mean RankDistal = 20.57, U = 748, Z = 4.45, p < 0.001), while the respondents in the distal condition tended to use more nonrational strategies (t = 4.3, df = 58, p < 0.001). Differences were found among physical (Mean RankProximal = 18.77, Mean RankDistal = 42.23, U = 98, Z = -5.4, p < 0.001), social distancing (Mean RankProximal = 22.07, Mean RankDistal = 38.93, U = 197, Z = -4.1, p < 0.001), victim blame (Mean RankProximal = 25.23, Mean RankDistal = 35.77, U = 292, Z = -2.6, p < 0.01), and minimization scores (Mean RankProximal = 24.67, Mean RankDistal = 36.33, U = 275, Z = -3.15, p < 0.01), while suffering weighing, ascribing meaning to suffering and anticipatory perpetrator punishment did not show statistically significant differences (p > 0.05).

Furthermore, knowledge about situation analysis is provided to account for potential confounding variables. Although there were statistically significant differences in knowledge among the groups, (χ2 = 45.29, df = 3, p < 0.001), where 96% of the proximal distance group members at least somewhat knew about the situation, as compared to only 13% in the distal condition, the ANCOVA test showed there were no statistically significant interactions between knowledge about a conflict in the conditions and just-world belief scores (p = 0.33), as well as the rational strategy (p = 0.13) and the nonrational strategy use (p = 0.27). This means that there were differences in the knowledge about the conditions, however, this did not yield any statistically significant effects on the results.

Figure 2

Rational and nonrational defense strategy comparison in psychological distance groups

![[Figure 2 illustrates defense strategy endorsement scores between the distal and the proximal condition via a bar chart. The x-axis shows the type of defense, from left to right reading financial support, direct support, physical distancing, social distancing, victim blame, minimization, weighing of suffering, ascribing meaning to suffering, and anticipatory punishment. Each defense strategy has two bars: one in white, and one in black. The white bar describes the distal condition, while the black bar describes the proximal condition scores. The y-axis shows endorsement mean ranks scores ranging from 0 to 50, in increments of 10. The bars are also marked with two or three stars, showing statistical significance and p values (two stars indicate p values less than one one-hundredth, whereas three stars indicate p scores of less than one one-thousandth). Rational and nonrational strategies are separated with a line.

The chart shows that there were visually big differences in the financial support and direct support as the proximal condition bars are approximately twice as large as the distal bars. Physical distancing and social distancing showed a similar effect, however, the distal condition bars were approximately twice as large as the proximal bars. These differences were marked with three stars, thus indicating statistical significance.

Victim blame and minimization show difference in scores between the conditions as well, where the distal bars can be seen as larger, however, these are visually less pronounced than the aforementioned bars and are marked by two stars of statistical significance. Weighing of suffering and anticipatory punishment visually shows larger bars in the distal condition than the proximal one, but they are not marked by any significance indicator. The bars representing ascribing meaning to suffering are barely visually distinguishable between the conditions, and no statistical significance is shown.

Overall, the bar chart illustrates that the two rational strategies are more endorsed in the proximal condition, while some, but not all, nonrational strategies are prominent in the distal condition.]](https://www.zurnalai.vu.lt/psichologija/article/download/39229/version/35371/40520/124382/ratiolis2.png)

Discussion and conclusions

The results showed that psychological distance can be an important component in terms of how people view events around the world and their victims. The first hypothesis has been disproven, as it was discovered that both messages were seen as similarly offensive to justice beliefs. Research has shown that psychological proximity increases justice judgments that are based on the target’s specific characteristics (Mentovich et al., 2016), while distal conditions are construed in morally abstract rather than specific principles (Eyal et al., 2008). In this way, distal conditions should proliferate moral judgments. However, due to the ambiguous literature surrounding justice beliefs and psychological distance, similar results between the distance conditions may not be a major surprise (Alper, 2020). At the time of the study, Ukrainian people have garnered much sympathy in Lithuanian society, as such, and therefore people’s moral judgements about this group have become dominatingly positive. This is why proximal conditions could have activated positive target specific characteristics about Ukrainian people which are not applicable to the people of Myanmar. In such a case, proximity may have stimulated a view towards those victims as more innocent, whose suffering is found to be more egregious (Hafer, 2000), and, in this way, similar justice effects to those of the distal condition were caused. On the other hand, the other two hypotheses have been proven correct. Indeed, psychologically proximal messages produced more rational responses to defend the just-world belief. This finding is in accordance with the Construal Level Theory, as it is the proximal messages that are construed more concretely, and, in this way, more conscious effort must be put in to appraise these messages (Liberman & Trope, 2014). As noted above, more conscious evaluation is the defining characteristic of rational strategies. Besides that, psychologically distal messages were found to induce the use of a more nonrational defense strategy. This essentially goes hand-in-hand with the Construal Level Theory as well, as more distal messages should be represented in a more abstract form, leading to less effortful evaluations. Moreover, Lammers (2012) has demonstrated that higher construal levels activate harsher moral judgments about other people. This result was replicated in our study, as nonrational strategies appeared more often in the distal (higher construal) condition. It seems that distal conditions make it easier to judge people while using less cognitive effort. It appears indicative that both proximal and distal distance reduces just-world belief in a significant manner, but these conditions have different effects on the rational versus nonrational strategy choice, where proximal conditions appear to exacerbate rational strategies, while distal conditions lead to more nonrational reactions.

Limitations

It is of importance to point out that the use of real news articles, while increasing the ecological validity of the study, may provide confounding variables. Firstly, the emotional nature of psychologically proximal texts must be acknowledged when considering the results. Messages are generally more emotionally loaded when presented as happening close rather than far away; and it could be argued that proximal messages about war can never be emotionally neutral. Secondly, different levels of knowledge have to be taken into account. People tend to be more knowledgeable about events happening near, rather than far, and this can appear as a confounding variable. Although a statistical test showed no significant result between knowledge and just-world belief, knowledge could still be associated with other effects. As mentioned above, at the time of the study, a lot of attention was being brought to the war in Ukraine as a conflict of special interest in Lithuania. This is due to historical reasons as both countries have dealt with the same looming threat over their existence and, as such, they have been facing similar challenges. On the other hand, significantly less attention has been paid to other conflicts around the world, thus – perhaps – contributing to hypersensitization effects about the proximal condition. As such, a more thorough look into how knowledge about victims interacts with just-world beliefs could be beneficial. Taking these limitations into account, it may be the case that the results are influenced by confounding current popular opinions and news coverage rather than strictly psychological distance effects. Nevertheless, further research into this topic seems warranted. In conclusion, the results of this study bring attention to how framing in terms of psychological distance can influence a person’s interpretation of unjust events and victims.

Author contributions

Justinas Zokas: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Kristina Vanagaitė: supervision, methodology, writing – original draft.

References

Alper, S. (2020). Explaining the Complex Effect of Construal Level on Moral and Political Attitudes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(2), 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419896362

Cao, X., & Decker, D. (2015). Psychological distancing: The effects of narrative perspectives and levels of access to a victim’s inner world on victim blame and helping intention. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 20(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1514

Dalbert, C. (1999). The World is More Just for Me than Generally: About the Personal Belief in a Just World Scale’s Validity. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 79–98.

Eyal, T., Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2008). Judging near and distant virtue and vice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(4), 1204–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.03.012

Fiedler, K., Jung, J., Wänke, M., & Alexopoulos, T. (2012). On the relations between distinct aspects of psychological distance: An ecological basis of construal-level theory. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(5), 1014–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.03.013

Hafer, C. L. (2000). Do innocent victims threaten the belief in a just world? Evidence from a modified Stroop task. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.165

Hafer, C., & Gosse, L. (2010). Preserving the belief in a just world: When and for whom are different strategies preferred? In D. R. Bobocel, A. C. Kay, M. P. Zanna, & J. M. Olson (Eds.), The psychology of justice and legitimacy (pp. ٧٩–١٠٢). Psychology Press.

Hafer, C. L., & Rubel, A. N. (2015). The why and how of defending belief in a just world. In J. M. Olson & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 51, pp. 41–96). Academic Press.

Lammers, J. (2011). Abstraction increases hypocrisy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(2), 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.006

Lerner, M. (1980). The Belief in a Just World: A Fundamental Delusion. Springer.

Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2014). Traversing psychological distance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.03.001

Modesto, J. G., & Pilati, R. (2017). “Not all victims matter”: belief in a just world, intergroup relations and victim blaming. Temas Em Psicologia, 25(2), 775–786. https://doi.org/10.9788/tp2017.2-18en

Reich, B., & Wang, X. (2015). And justice for all: Revisiting the Global Belief in a Just World Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 78, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.031

Russell, K. J., & Hand, C. J. (2017). Rape myth acceptance, victim blame attribution and Just World Beliefs: A rapid evidence assessment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.008

Soderberg, C. K., Amit, E., Callahan, S. P., Kochersberger, A. O., & Ledgerwood, A. (2015). The Effects of Psychological Distance on Abstraction: Two Meta-Analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 525–548. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/bul0000005

Warner, R. H., VanDeursen, M. J., & Pope, A. R. D. (2012). Temporal distance as a determinant of just world strategy. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(3), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1855

Zhang, M., & Wang, J. (2009). Psychological distance asymmetry: The spatial dimension vs. other dimensions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19(3), 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2009.05.001

Zhang, Q., Wei, W., Li, N., & Cao, W. (2022). The effects of psychological distance on spontaneous justice inferences: A construal level theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 1011497. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1011497