Socialiniai tyrimai eISSN 2351-6712

2021, vol. 44(1), pp. 8–28 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Soctyr.44.1.1

Straipsniai

The Role and Significance of the Data Protection Officer in the Organization

Aurimas Šidlauskas

Mykolo Romerio universiteto Ekonomikos ir verslo fakulteto doktorantas

Mykolas Romeris University, Faculty of Economics and Business, PhD student

El. p.: aurimas868@gmail.com

Summary. Following the entry into force of the General Data Protection Regulation (hereafter referred to as the GDPR), organizations that process personal data must ensure and demonstrate compliance with all of its principles. A new post, known as the Data Protection Officer (hereafter referred to as the DPO), has been created. The appointment of this official may be one of the measures necessary to implement the principle of accountability. The purpose of the article is to analyze the role and significance of the DPO in the organization, and to provide generalized recommendations. The role and significance of the DPO will continue to grow, as will the tasks and activities of the DPO. It is important to emphasize that GDPR compliance is the responsibility of the data controller or data processor, not the DPO.

Keywords: General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Data Protection Officer (DPO), Personal data.

Duomenų apsaugos pareigūno vaidmuo ir reikšmė organizacijoje

Santrauka. Bendruoju duomenų apsaugos reglamentu (Reglamentas), įsigaliojusiu 2018 metų gegužės 25 dieną, siekiama apsaugoti fizinių asmenų pagrindines teises ir laisves, visų pirma – jų teisę į asmens duomenų apsaugą. Reglamente pateikiami įvairūs reikalavimai, standartai ir atsakomybė. Nors asmens duomenų apsauga nėra absoliuti teisė, tačiau ji įgauna vis svarbesnį vaidmenį. Atsirado nauja pareigybė – duomenų apsaugos pareigūnas (Pareigūnas), jis yra nepriklausomas subjektas, užtikrinantis, kad organizacija laikytųsi Reglamento. Pareigūnas yra tarpininkas tarp duomenų subjektų, duomenų valdytojo ar tvarkytojo ir duomenų apsaugos priežiūros institucijos. Pareigūno institutas turi vykdyti galimų Reglamento nuostatų pažeidimų prevenciją ir padėti išvengti didelių finansinių nuostolių. Organizacija privalo užtikrinti ir įrodyti atitiktį visiems Reglamento principams, Pareigūno paskyrimas gali būti viena iš priemonių būtinų įgyvendinti atskaitomybės principą.

Šio mokslinio straipsnio aktualumas siejamas su Reglamento naujumu ir reikšmingumu duomenų apsaugos teisei.

Problema. Koks Pareigūno vaidmuo ir reikšmė organizacijoje?

Straipsnio tikslas – išanalizuoti Pareigūno vaidmenį ir reikšmę organizacijoje bei pateikti apibendrintas rekomendacijas. Keliami uždaviniai:

1. Atskleisti, kokiais pagrindais remiantis yra privaloma organizacijoje paskirti Pareigūną.

2. Įvardinti, kuomet gali kilti didelė interesų konflikto rizika skiriant Pareigūną ir kaip jos išvengti.

3. Išnagrinėti Pareigūnui keliamus kvalifikacinius reikalavimus, jo funkcijas ir statusą organizacijoje.

Metodologija: šiame moksliniame straipsnyje naudoti dokumentų analizės, loginis, lyginamasis, apibendrinimo tyrimo metodai. Dokumentų analizės metodas taikomas tiriant įvairius teisinius dokumentus, atsižvelgiant į jų oficialumą, privalomąjį ir neprivalomąjį pobūdį, siekiant ištirti asmens duomenų apsaugos teisinį reguliavimą, nustatytą įvairiose teisės normose. Loginis metodas naudojamas aiškinant teisės normų turinį, jį pritaikant organizacijoms. Lyginamasis metodas naudojamas atliekant lyginamąją analizę. Apibendrinimo metodas taikomas nagrinėjamais klausimais apibendrinant naudotą literatūrą, taip pat formuluojant pagrindinius tyrimo teiginius bei pabaigoje darant galutines išvadas.

Pareigūną privalo paskirti valdžios institucijos ir įstaigos bei kitos organizacijos, kurių pagrindinė veikla yra dideliu mastu sistemingai stebėti asmenis arba dideliu mastu tvarkyti specialių kategorijų asmens duomenis. Reglamento nuostatas, nustatančias kriterijus, pagal kuriuos yra privaloma paskirti Pareigūną, galima vertinti kritiškai dėl teisinio apibrėžtumo, aiškumo trūkumo, todėl kiekvieną atvejį reikia vertinti individualiai, priklausomai nuo organizacijos statuso ir veiklos pobūdžio duomenų tvarkymo kontekste. Pareigūno paskyrimas, nesant konkretesnio teisinio reguliavimo, iš esmės priklauso nuo subjektyvaus duomenų valdytojo savęs ir savo veiklos suvokimo. Tačiau Pareigūno paskyrimas turėtų būti vertinamas kaip organizacijos socialinės atsakomybės už jos sprendimų ir veiklos poveikį visuomenei skaidraus ir etiško elgesio ženklas. Be to, gali palengvinti reikalavimų laikymąsi ir tapti konkurenciniu pranašumu.

Vienas iš pagrindinių kriterijų, vertinant, ar dėl konkrečios pareigybės gali kilti interesų konfliktas, yra asmens duomenų tvarkymo tikslų ir priemonių nustatymo galimybė (įgaliojimai). Valdžios institucijos ir įstaigos, atsižvelgiant į jų struktūrą, veiklą ir kitas reikšmingas aplinkybes, turėtų kiekvienu konkrečiu atveju vertinti, ar konkreti pareigybė, net jei ji nepriklauso vyresniajai vadovybei, galėtų kelti interesų konfliktą.

Skiriant Pareigūną organizacijoje reikėtų atsižvelgti į jo ekspertinių žinių lygį, profesines savybes ir gebėjimą atlikti užduotis. Pareigūnas turi nuolatos tobulinti savo žinias duomenų apsaugos srityje, nes profesionali veikla kokybiškai gali būti vykdoma tik remiantis specifinėmis žiniomis apie konkrečią veiklos sritį. Ugdomas gebėjimas derinti, jungti įvairias žinias, įgytas iš įvairių šaltinių, į visumą, skatina savarankišką ir greitą efektyvių sprendimų atradimą. Po Reglamento įsigaliojimo sparčiai formuojasi jo taikymo praktika, tam įtakos turi institucinis izomorfizmas:

• Priverstinis izomorfizmas atsiranda dėl privalomų standartų ar kitų teisės aktų taikymo.

• Mimetiškas izomorfizmas atsiranda dėl kopijavimo ir mėgdžiojimo.

• Normatyvinis izomorfizmas atsiranda dėl stiprios profesinės kompetencijos įtakos.

Pareigūnas savo pareigas ir užduotis turėtų galėti atlikti nepriklausomai, todėl svarbus jo statusas organizacijoje. Apie Pareigūno paskyrimą turi būti informuoti visi organizacijos darbuotojai, jis kuo ankstyvesniu etapu įtraukiamas į visus su duomenų apsauga susijusius klausimus. Pareigūnui turi būti užtikrinama vyresniosios vadovybės parama ir skiriama pakankamai laiko jo funkcijoms atlikti bei galimybė naudotis kitomis organizacijos tarnybomis, o esant poreikiui, sudaryti Pareigūno grupę, kurią sudarytų Pareigūnas ir darbuotojai, vykdantys jo užduotis. Pareigūnas neturi gauti nurodymų, kaip spręsti su duomenų apsauga susijusius klausimus. Įpareigojimu laikytis slaptumo ar konfidencialumo Pareigūnui nedraudžiama susisiekti su Inspekcija ir kreiptis į ją konsultacijos. Pareigūnų veiklos principai grindžiami ekspertine kompetencija, nepriklausomumu, interesų konflikto vengimu, prieinamumu, veiklos formos laisve.

Reglamento atitikties priežiūra organizacijoje nereiškia, kad Pareigūnas yra asmeniškai atsakingas už reguliavimo pažeidimus. Reglamento atitiktis yra priskiriama duomenų valdytojo ar duomenų tvarkytojo, o ne Pareigūno atsakomybei. Reglamento atitikties reikalavimų nesilaikančioms organizacijoms už pažeidimus gali būti skiriamos baudos iki 20 milijonų eurų arba 4% ankstesnių finansinių metų bendros metinės pasaulinės apyvartos ir žalos atlyginimas.

Pagrindiniai žodžiai: Bendrasis duomenų apsaugos reglamentas (Reglamentas), duomenų apsaugos pareigūnas (Pareigūnas), asmens duomenys.

_______

Received: 25/01/2021. Accepted: 24/05/2021

Copyright © Aurimas Šidlauskas, 2021. Published by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

On 25 May 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (hereafter referred to as GDPR) went into effect in the European Union. This GDPR protects fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons and in particular their right to the protection of personal data. The GDPR is a long comprehensive legal document containing various requirements, standards and responsibilities. This GDPR aims to meet the current challenges related to personal data protection, strengthen online privacy rights and boost Europe’s digital economy (Limba et al., 2020). The European Commission (2018) states that organizations that fail to adequately protect an individual’s personal data risk losing consumer trust, which is essential to encouraging people to use new products and services. As the GDPR abounds in abstract provisions that require a competent assessment, one cannot rely on their content alone. In order to properly implement the provisions of the legal instruments aimed at data protection, one must follow the guidelines of the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party (hereafter referred to as WP29), which have a direct practical significance for the application of the GDPR (Radžiūtė, 2018). There is a growing number of sources of interpretation and understanding of data protection law. Data protection is, therefore, arguably quite different from many other areas of legal practice (Lambert, 2017). In addition, as the GDPR entered into force, the European Data Protection Board (hereafter referred to as EDPB), which brings together the supervisory authorities responsible for personal data protection in the EU Member States, also became operational. This organization, is an independent European body, which contributes to the consistent application of data protection rules throughout the European Union, and promotes cooperation between the EU’s data protection authorities. The special role of the EDPB in the field of personal data protection is to formally interpret the provisions of the GDPR, thus ensuring the uniform application of this legislation throughout the European Union. One of the most important elements which comprise the EDPB’s activities is providing guidelines, recommendations and examples of best practice to the public. The supervisory authority responsible for personal data protection in the Republic of Lithuania is the State Data Protection Inspectorate (hereafter referred to as Inspectorate), whose mission is to protect the human right to personal data protection. An appropriate mechanism for data protection is a public interest, one that is vital to the state. Although the protection of personal data is not an absolute right, it has been gaining an increasingly important role in everyday life (Batutytė, 2019). A new post has been created in the GDPR, the Data Protection Officer (hereafter referred to as the DPO), an independent body whose task is to make sure the organization complies with the GDPR. Not all organizations who process personal data are required to appoint a DPO, but all are required to ensure compliance with the GDPR.

The relevance of this academic article is related to the novelty of the GDPR, as well as the significance thereof to data protection law.

The research problem. What is the role and significance of the DPO in the organization?

The object of research is the role and significance of the DPO.

The aim of the article is to analyze the role and significance of the DPO in the organization, and to provide generalized recommendations. The objectives of research:

1. To reveal the grounds on which the appointment of a DPO in an organization is mandatory.

2. To identify the instances when there may be a significant risk of a conflict of interest associated with the appointment of the DPO, along with the ways of avoiding such conflict.

3. To examine the qualification requirements for the DPO, his or her functions and status within the organization.

The research methods used in this academic article include scientific literature review and legal document analysis, as well as logical, comparative, and generalization-based research methods. A literature review can broadly be described as a more or less systematic way of collecting and synthesizing previous research (Baumeister, Leary, 1997; Tranfield et al., 2003). Literature reviews play an important role as a foundation for all types of research. They can serve as a basis for knowledge development, create guidelines for policy and practice, provide evidence of an effect, and, if well conducted, have the capacity to engender new ideas and directions for a particular field. As such, they serve as the grounds for future research and theory (Snyder, 2019).

Document analysis is applied to examine various legal documents, with their formality, their binding (mandatory) or non-binding (optional) nature taken into account in order to investigate the legal regulation aimed at personal data protection, as enshrined in various legal norms. Document analysis requires that data be examined and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). It involves the analysis of written materials containing information on the examined phenomenon or phenomena (Yıldırım and Şimşek, 2005). Documents are a very accessible and reliable source of data (Bowen, 2009). The logical method of interpretation permits the formulation - by the interpreter - of certain rational assessments, achieved through generalizing operations, of logical analysis of the text of the legal norm, or analogy, through applying formal logic (Bădescu, 2017). The logical method is used to interpret the content of legal provisions, insofar as they apply to organizations. The comparative method is used for comparative analysis. A generalization is an act of reasoning that involves drawing broad conclusions from particular instances – that is, making an inference about the unobserved based on the observed (Polit and Beck, 2010). The method of generalization is applied to summarize the sources used for the research, to formulate the main claims and to draw the final conclusions at the end.

The appointment of a Data Protection Officer in an organization

Data controller means the institution or body that determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data. In particular, the controller has the duties of ensuring the quality of data and, in the case of the EU institutions and bodies, of notifying the processing operation to the DPO. In addition, the data controller is also responsible for the security measures protecting the data. The controller is also the entity that receives requests from data subjects to exercise their rights. The controller must cooperate with the DPO, and may consult him or her for an opinion on any data protection related question (European Data Protection Supervisor, 2019). The data controller must employ certain organizational and technical security measures to ensure compliance with the GDPR (Šidlauskas, 2019). One of the main reasons for poor protection is the general failure to realize that security is essential, as is taking care thereof. Other reasons include inexperienced security specialists and a lack of funding (Štitilis et al., 2016).

Early adoption of the required changes not only guarantees compliance with the GDPR but can also bring a competitive advantage (Tikkinen-Piri et al., 2018). Article 5 of the GDPR sets out seven key principles which lie at the heart of the general data protection regime. Article 5(1) requires that personal data shall be:

1. Processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner in relation to individuals (‘lawfulness, fairness and transparency’).

2. Collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes; further processing for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes shall not be considered to be incompatible with the initial purposes (‘purpose limitation’).

3. Adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed (‘data minimisation’).

4. Accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date; every reasonable step must be taken to ensure that personal data that are inaccurate, having regard to the purposes for which they are processed, are erased or rectified without delay (‘accuracy’).

5. Kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the personal data are processed; personal data may be stored for longer periods insofar as the personal data will be processed solely for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes subject to implementation of the appropriate technical and organisational measures required by the GDPR in order to safeguard the rights and freedoms of individuals (‘storage limitation’).

6. Processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security of the personal data, including protection against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage, using appropriate technical or organisational measures (‘integrity and confidentiality’).

7. Article 5(2) adds that the controller shall be responsible for, and be able to demonstrate compliance with, these principles (‘accountability’).

The appointment of a DPO can be among the measures required to implement the principle of accountability (Voigt and Von dem Bussche, 2017). The DPO is an employee or external expert (service provider) who oversees the data controller or data processor and helps ensure their compliance with the GDPR (Zaleskis, 2017). The institute of the DPO must act as a “safeguard” of sorts for the data controller, curbing any possible breaches of the provisions of the GDPR, and, at the same time, helping prevent significant financial losses resulting from potential violations (Januševičienė, 2018). The DPO must be flexible, and act as an arbitrator between the law and the actions of the organisation (Gobeo et al., 2018).

UK Information Commissioner Elizabeth Denham (2019) argues that DPOs have an important role to play in helping companies shift from baseline compliance to real accountability.

The GDPR grants the DPO a fairly important role within the entire data management system. Depending on the powers and functions assigned to them, the DPO must be regarded as a person who will not only have the obligation to assist data controllers and processors in properly implementing different data protection requirements, but who will also act as a mediator between data subjects and between the data controller or data processor and the supervisory authority responsible for data protection (Štareikė, Kausteklytė-Tunkevičienė, 2018). The precise scope and detail of the DPO role will depend on the size of the organisation and the complexity of the processing it is engaged in (Alford, 2020). Bamberger and Mulligan (2015) describes DPO role as the most important regulatory choice for institutionalising data protection. In practice, the DPO is the early warning indicator of adverse events when processing personal data within the organisation (Drewer and Miladinova, 2018)

An important duty on part of the data controller or data processor is to appoint the DPO. The data controller is the entity who sets the purpose for which the personal data is to be processed, as well as the means of doing so, whereas the data processor processes the personal data on the controller’s behalf in accordance with the instructions they provide. Pursuant to Article 37(1) of the GDPR, the DPO must be appointed when:

1. “The processing is carried out by a public authority or body, except for courts acting in their judicial capacity.” The GDPR does not provide a definition of a “public authority or body”, but Member States have the right to choose which bodies, enterprises, organizations or institutions to include in this concept in accordance with national law. Therefore, Article 2(2) of the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on the Legal Protection of Personal Data states that public authorities and institutions are to be understood as state and municipal institutions and establishments, enterprises and public enterprises financed from the state or municipal budgets or state monetary funds which are authorized to perform public administration, or provide public and administrative services to individuals or perform other public services in accordance with the Law of the Republic of Lithuania on Public Administration functions. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that this provision of the GDPR applies regardless of the precise data being processed.

2. “The core activities of the controller or the processor consist of processing operations which, by virtue of their nature, their scope and/or their purposes, require regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale.” ‘Core activities’ can be considered as the key operations to achieve the controller’s or processor’s objectives. These also include all activities where the processing of data forms as inextricable part of the controller’s or processor’s activity. The notion of regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects is not defined in the GDPR, but clearly includes all forms of tracking and profiling on the internet, including for the purposes of behavioural advertising. However, the notion of monitoring is not restricted to the online environment. WP29 interprets ‘regular’ as meaning one or more of the following: ongoing or occurring at particular intervals for a particular period; recurring or repeated at fixed times; constantly or periodically taking place. WP29 interprets ‘systematic’ as meaning one or more of the following: occurring according to a system; pre-arranged, organised or methodical; taking place as part of a general plan for data collection; carried out as part of a strategy.

3. “The core activities of the controller or the processor consist of processing on a large scale of special categories of data or personal data relating to criminal convictions and offences.” Personal data are treated as belonging to a special category if they include the particularly sensitive information of individuals, whose disclosure could have a significant impact on their rights and freedoms. Special categories of personal data: racial or ethnic origin; political opinions; religious or philosophical beliefs; trade union membership; processing of genetic data; biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person; health; sex life or sexual orientation. The GDPR does not define what constitutes large-scale processing. The WP29 recommends that the following factors, in particular, be considered when determining whether the processing is carried out on a large scale: the number of data subjects concerned - either as a specific number or as a proportion of the relevant population; the volume of data and/or the range of different data items being processed; the duration, or permanence, of the data processing activity; the geographical extent of the processing activity.

The provisions of the GDPR which lay down the criteria for appointing a DPO could be criticized for their lack of legal certainty and clarity. It would be reasonable and appropriate to describe the instances of legal regulation where a DPO must be appointed in greater detail (Zaleskis, 2017). The European Commission provides examples of situations where the appointment of a DPO is mandatory or optional on its website, “ec.europa.eu” (see Table 1).

Table 1. Examples provided by the European Commission as to where a DPO is or is not mandatory

|

DPO mandatory |

DPO not mandatory |

|

when your company/organisation is a hospital processing large sets of sensitive data |

you’re a local community doctor and you process personal data of your patients |

|

when your company/organisation is a security company responsible for monitoring shopping centres and public spaces; |

you have a small law firm and you process personal data of your clients |

|

when your company/organisation is a small head-hunting company that profiles individuals. |

you only send promotional materials to your customers once a year |

|

you process personal data for search engine advertising based on people’s online behavior |

Source: European Commission (2020).

Of course, examples may vary and the situations arising within an organization should be considered on a case-by-case basis, depending on its status and the nature of its activities in the context of data processing, and in keeping with the GDPR.

At the end of 2019, the federal German DPA fined a telecommunications provider 10.000 euros for repeatedly failing to appoint a DPO despite multiple requests from the German DPA. The company failed to comply with its legal requirement under Article 37 of the GDPR to appoint an internal DPO. When imposing the 10.000 euros fine, the fact was taken into account that the company is belonging to the category of micro-enterprises (EDPB, 2019).

The WP29 points out that, depending on who fulfills the criteria for mandatory appointment, in some cases the DPO must be appointed exclusively by the data controller or the data processor, and in other cases by both the controller and the processor. It is important to emphasize that even if the data controller does meet the criteria for the mandatory appointment of a DPO, his data processor does not necessarily have to appoint the Data a DPO. However, this can be a beneficial experience. Jakštaitė (2018) claims that, in the absence of more specific legal regulation, the appointment of the DPO essentially depends on the duty holder’s subjective perception of themselves and their activities, and, taking into account that the DPO is closely related to the fulfillment of obligations by other data controllers and data processors, the question of full compliance with the provisions of the GDPR may also be raised should it be decided that no there is no obligation to appoint a DPO. The appointment of the DPO by data controllers, not bound to do so by law, should be judged a sign of the organization‘s corporate social responsibility for the impact of its decisions and activities on society through transparent and ethical conduct (Nerka, 2017). The appointment of a DPO can facilitate compliance and become a competitive advantage (Drewer and Miladinova, 2018) and demonstrates that the organization recognizes data as its main asset and the fact that they are crucial to their success (Zerlang, 2017). With corporate responsibility increasing, it is recognized that business and public services are not free from values and cannot meet standards based solely on measurable performance indicators. Responsibility means thinking about the consequences of a person in relation to others and clear lines in the issue of accountability (Žydžiūnaitė, 2018).

The Inspectorate announces on its website that when an organization appoints a DPO, the Inspectorate must be informed, i.e. given notice of the newly appointed DPO. The notification must be signed by the manager or his authorized representative and contain the following information:

• Name, legal entity code, contact details of the company, institution or organization, i. e. the data controller or data processor.

• Information on whether the DPO has been appointed by the controller or the processor.

• Name and surname, position (if an employee of the data controller is appointed), or legal entity name (if the DPO is an employee of another legal entity).

• The DPO’s address, telephone number, e-mail address and other means of communication.

The Hamburg Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information imposed a fine of 51.000 euros on Facebook Germany GmbH in December 2019, because the Hamburg DPA was not appropriately notified in accordance with GDPR Article 37(7), which requires both the publication of the DPO’s contact details and communication of those details to the relevant supervisory authority (EDPB, 2019).

According to the WP29, there is nothing to preclude an organization that is not under a legal obligation to appoint a DPO and does not wish to appoint one on a voluntary basis from employing certain staff members or hiring external consultants to be delegated with tasks connected to personal data protection. In this case, it is important to ensure that there is no confusion as to their job title, status, responsibilities and tasks. Thus, in any of the company’s internal communications, as well as in any dealings with data protection authorities, it should be made clear to data subjects and to the general public alike that this particular person or consultant is not a DPO.

The Inspectorate states that, as the assessment of the information obtained from public authorities and bodies has revealed, a common shortcoming while appointing an Official is the specific choice of post, i.e. it has been observed that the persons appointed as Officials often pose a significant risk of a conflict of interest. One of the main criteria for assessing whether a particular post may give rise to a conflict of interest is the possibility (powers) to determine the goal behind the processing of personal data or the means of doing so. In other words, if a particular position enables one to determine the purpose for which the data will be processed, as well as which data to collect and to what extent, which way the data is to be collected, and so on (i.e. to determine what is to be processed, why and how), one can conclude that that a conflict of interest would really be possible. In general, the following positions could be considered to give rise to a conflict of interest:

1. Senior management such as the CEO, the Chief Financial Officer, the Chief Medical Officer, the Marketing Manager, the Human Resources Manager, the IT Manager, and so forth.

2. Lower-level responsibilities where the duties or functions require one to set the goals behind the data processing and to determine the means of doing so: security officers, deputy managers, and so forth.

3. In the case of an external DPO, if he is called upon to represent a public authority or body before the courts in data protection matters.

In addition, one must emphasize that public authorities and bodies, depending on their structure, activities and other relevant circumstances, should assess on a case-by-case basis whether a particular position, even if not part of senior management, could give rise to a conflict of interest.

Following its investigation of a personal data breach, the Belgian Data Protection Authority issued a ruling on April 28, 2020, imposing a 50.000 euros fine on an organization for negligence in having appointed the company’s head of compliance, risk and audit as its DPO. This decision should cause entities to reconsider appointing a DPO who holds another senior role in the organization (Sterling et al., 2020).

CPO Magazine has released a comprehensive report outlining the challenges and priorities of data protection and privacy officers around the world in 2019. Based on the responses of 252 data privacy professionals worldwide, it is clear that many organizations could be doing much more to build and implement data privacy programs. For example, 45% of organizations are spending less than 250.000 dollars annually on data protection and privacy and 23% of organizations have only a single employee within the data protection and privacy program. Considering that some of these organizations have more than 10.000 employees worldwide, it would appear that much more could still be done to build a world-class data privacy organization.

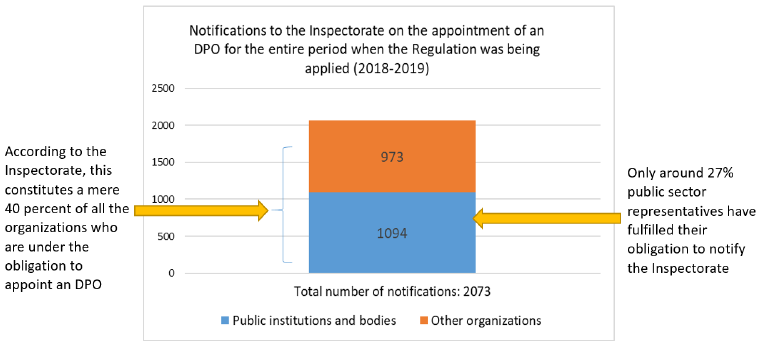

The Inspectorate’s activity report for 2019 states that 2073 organizations, including 1094 representatives of the public sector, have notified the Inspectorate about the appointment of a DPO throughout the entire period when the GDPR was being applied (2018-2019). In view of the information available to the Inspectorate on the DPOs appointed in Lithuania, it is estimated that 40% of the organizations who are under the obligation to appoint an DPO did so. Please note that the GDPR requires these DPOs to be be appointed by any members of the public sector, and that only around 27% public sector representatives have fulfilled this obligation (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Inspectorate statistics and claims

Source: compiled by the author and based on the activity report of the State Data Protection Inspectorate for 2019 (2020).

Based on the Inspectorate’s activity report for 2019, one can state that most organizations are not properly acquainted with the provisions of the GDPR and have therefore failed to fulfill the obligation to appoint a DPO and/or to notify the Inspectorate of his appointment.

Functions, qualification requirements and status of a Data Protection Officer within an organization

In an organization, the DPO shall be appointed on the basis of his professional qualities, in particular, his expertise in data protection law and practice, as well as his ability to perform the tasks referred to in Article 39 of the GDPR. The DPO may be one of the organization’s own employees or a third party. The DPO shall have at least the following tasks:

1. To inform and advise the controller or the processor and the employees who carry out processing of their obligations pursuant to this GDPR and to other Union or Member State data protection provisions.

2. To monitor compliance with this GDPR, with other Union or Member State data protection provisions and with the policies of the controller or processor in relation to the protection of personal data, including the assignment of responsibilities, awareness-raising and training of staff involved in processing operations, and the related audits.

3. To provide advice where requested as regards the data protection impact assessment and monitor its performance.

4. To cooperate with the Inspectorate.

5. To act as the contact point for the Inspectorate on issues relating to processing, including the prior consultation referred to in Article 36, and to consult, where appropriate, with regard to any other matter.

Also, the DPO shall in the performance of his or her tasks have due regard to the risk associated with processing operations, taking into account the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing.

The DPO should assess what personal data the organization collects and processes, for what purpose, and where they are located and secured. Particular attention is needed with outsourcing issues and contracts with processors. Contracts, including service-level agreements in relation to information technology (IT) systems, the cloud, and so on may be assessed. The various IT hardware, software, and systems that employees use need to be considered. The structure of the organization or groups needs to be considered as well as jurisdiction and location issues. The life cycle, storage, and disposal of personal data are also an important consideration for the DPO. (Lambert, 2017). Being able to pinpoint the location, application and storage techniques for personal data, DPOs can design and implement the security processes and technologies they will need to see, understand and interact with to carry out their duties (Wilson, 2018). Thus, we can see that the DPO’s role is key in the overall processing operation as a human firewall regarding all things related to data security in an organization. This helps the regulation ensure overall accountability by having an accountable officer within an organization who oversees the operation and ensures compliance while processing personal data (Sharma, 2019; Agostinelli et al., 2019).

Undoubtedly, the role and importance of the DPO will continue to grow, as will the tasks and activities of the DPO. On the one hand, this is due to the increasing complexity of processing operations, which requires DPOs to understand both the business needs, but also technical intricacies in more detail. On the other hand, organisations are fascinated by and want to make use of new technologies, which may often be challenging from a data protection point of view (Eggl, 2019).

According to Zaleskis (2019), the functions of the DPO may be entrusted to external service providers when the data controller and data processor lack experience in the field of data protection law, or desire to save time, human and administrative resources.

Recital 97 of the GDPR provides that the necessary level of expert knowledge should be determined according to the data processing operations carried out and the protection required for the personal data being processed. The information below has been provided by the WP29 and should be taken into consideration when appointing a DPO:

1. Level of expertise. The required level of expertise is not strictly defined but it must be commensurate with the sensitivity, complexity and amount of data an organisation processes. For example, where a data processing activity is particularly complex, or where a large amount of sensitive data is involved, the DPO may need a higher level of expertise and support. There is also a difference depending on whether the organisation systematically transfers personal data outside the European Union or whether such transfers are occasional. The DPO should thus be chosen carefully, with due regard to the data protection issues that arise within the organisation.

2. Professional qualities. Although the GDPR does not specify the professional qualities that should be considered when designating the DPO, it is a relevant element that DPOs must have expertise in national and European data protection laws and practices and an in-depth understanding of the GDPR. Knowledge of the business sector and of the organisation of the controller is useful. The DPO should also have a good understanding of the processing operations carried out, as well as the information systems, and data security and data protection needs of the controller. In the case of a public authority or body, the DPO should also have a sound knowledge of the administrative rules and procedures of the organisation.

3. Ability to fulfil its tasks. Ability to fulfil the tasks incumbent on the DPO should be interpreted as both referring to their personal qualities and knowledge, but also to their position within the organisation. Personal qualities should include for instance integrity and high professional ethics; the DPO’s primary concern should be enabling compliance with the GDPR. The DPO plays a key role in fostering a data protection culture within the organisation and helps to implement essential elements of the GDPR, such as the principles of data processing, data subjects’ rights, data protection by design and by default, records of processing activities, security of processing, and notification and communication of data breaches.

The most important element of the DPO is to remain independent and aligned solely to the requirements of the law they uphold, whilst balancing the rights of EU citizens and the needs of the organisation. The DPO should uphold the values of confidentiality, integrity and ethics within themselves to accomplish what others are not willing to do (Gobeo et al., 2018). Personal qualities like integrity, professional ethics, and the will to do the right thing are crucial in an effective DPO (Brusoni and Vaccaro, 2017).

Šidlauskas (2019) believes that the DPO may improve his knowledge in the field of data protection by taking advantage of various opportunities, such as studying the GDPR, consulting with the Authority, relying on external audit procedures (should any be carried out), using public and paid sources of information, attending conferences, taking courses. While operating in an environment full of uncertainties, every organization is faced with the problem of information accessibility, or, on the contrary, with the excess thereof (Jucevičius et al., 2017). By working for an organization, people acquire specialized skills, their talents and attitudes are revealed, and they have a bearing on productivity, quality and profitability. People become “human resources” with special roles (activities) of their own, which they perform within the organization. The role of each employee is purposefully defined, with the important part being a maximum personal contribution to achieving the organization’s strategic goals (Chlivickas et al., 2009). The main task of the organizational leaders in the context of knowledge management is to guarantee an environment in which the members of the organization would be motivated to acquire, develop, use and exchange knowledge in pursuit of the organization’s common goals (Vaitkevičius, 2016).

Once the GDPR has entered into force, the practice of its application is rapidly evolving, as the EDPB and the Inspectorate provide clarifications and recommendations as to how certain provisions of the GDPR should be applied, or how a specific situation should be treated to ensure compliance with the GDPR as far as data processing is concerned. The volume of scientific literature on data protection is growing, but one factor that has a significant impact on the application of the GDPR is institutional isomorphism. Institutional isomorphism is understood as the growing, sustained mutual resemblance of structures, practices, principles, which is determined by the connections between institutions, as well as by cooperation and by the need to operate in a shared institutional field (Noreikaitė, 2014). Mintzberg (2005) distinguishes three types of isomorphism:

• Mandatory isomorphism results from the application of obligatory standards or other legislation.

• Mimetic isomorphism results from copying and imitation. Organizations often copy the attitudes of their successful competitors, of course, because such attitudes are associated with success, but also because they wish to convince others that they too are examples of best practice.

• Normative isomorphism results from the strong influence of professional competence. Modern organizations are often dominated by experts who create their own general professional norms when making decisions.

The developing ability to combine and incorporate the knowledge gained from various sources into an indivisible whole promotes the independent and rapid discovery of efficient solutions. Learning is a continuous process: “learning” one thing opens up new domains of cognition and comprehension. Students learn to reveal their advantages and to notice opportunities, to set goals that are acceptable, yet ambitious, to solve problems in a creative fashion (Kvedaravičius et al., 2018). People create, use, share knowledge, and they also encourage each other to share knowledge. Knowledge belongs to the people, and the sharing thereof depends on the people’s will (Vaitkevičius, 2018). It is easier for organizations to manage knowledge if employees are willing to share it (Amayah, 2013).

Since reality is subjective, the aim is to teach an individual to comprehend the world around him and, along with the other members of society, to address the challenges pertaining to the development of consistency and sustainability which they face together. The theory of constructivism defines sustainable development learning as an active and continuous process, during which learners receive information from the environment and form their personal experience, meanings and knowledge constructs (Petkevičiūtė, Balčiūnaitienė, 2018). Professional activities can only be high-quality when they are based on specialized knowledge about a particular field of activity (Zakarevičius, 2013).

The lack of privacy knowledge and expertise inside organizations, which translates in a lack of awareness or in a difficulty to understand the regulation, may also require extra budget to recruit privacy experts (Lindgren, 2018). Designating an inside DPO is also a challenge as it is difficult to recruit and retain people with these skills (Tikkinen-Piri et al., 2018; Khan, 2018). The Inspectorate’s report for 2019 states that the market is facing a shortage of personal data protection specialists, since, now that the GDPR is being applied, apart from having to appoint a DPO, quite a few organizations must hire other professionals to deal with personal data protection in order to ensure compliance with the GDPR.

The DPO should assist in fostering good business practice, whilst upholding the rights of EU citizens, and balancing the needs of the business with those of the people of Europe (Gobeo et al., 2018). The DPO should be able to perform his duties and tasks independently, whether or not he is an employee of the data controller, so his status in the organization is important. Article 38 of the GDPR specifies the provisions on the status of the DPO and the WP29 has provided some recommendations for their implementation (see Table 2).

Table 2. DPO status

|

GDPR |

WP29 recommendations |

|

GDPR |

WP29 recommendations |

|

The controller and the processor shall ensure that the DPO is involved, properly and in a timely manner, in all issues which relate to the protection of personal data. |

The DPO shall be involved at the earliest possible stage in all matters relating to data protection, and shall be considered within the organization as a discussion partner, one who participates in relevant working groups or in senior and middle management meetings. |

|

The controller and processor shall support the DPO in performing the tasks referred to in Article 39 by providing resources necessary to carry out those tasks and access to personal data and processing operations, and to maintain his or her expert knowledge. |

The following aspects must be considered in the organization:

|

|

The controller and processor shall ensure that the DPO does not receive any instructions regarding the exercise of those tasks. He or she shall not be dismissed or penalised by the controller or the processor for performing his tasks. The DPO shall directly report to the highest management level of the controller or the processor. |

The DPO may not receive any instructions on how to deal with data protection issues. If the decisions made by the controller or processor are incompatible with the GDPR or with the DPO’s advice, the DPO should be given the opportunity to clearly voice his or her objections to the senior management and the decision-makers. Penalties are prohibited by the GDPR only if imposed in connection with matters relating to the performance of the DPO’s duties. |

|

Data subjects may contact the DPO with regard to all issues related to processing of their personal data and to the exercise of their rights under this GDPR. |

It is vital to be able to contact the DPO physically or by any other secure means of communication. |

|

The DPO shall be bound by secrecy or confidentiality concerning the performance of his or her tasks, in accordance with Union or Member State law. |

The obligation to observe secrecy or confidentiality does not prohibit the DPO from contacting and consulting the Inspectorate. |

|

The DPO may fulfil other tasks and duties. The controller or processor shall ensure that any such tasks and duties do not result in a conflict of interests. |

Organizations could apply the following good practice:

|

Source: Compiled by the author and based on the GDPR and on the guidelines supplied by the WP29 (2016).

The analysis of the GDPR demonstrates that the regulation of the DPOs’ activities tends to be based on general principles rather than on detailed requirements which set out a specific pattern of behavior. The following principles to be observed by a DPO in his activities can be distinguished: expert competence, independence, avoiding conflicts of interest, accessibility, freedom of form (Zaleskis, 2017). Three central findings can be derived regarding factors that influence DPO behavior: (1) DPOs recognize a fundamental necessity in their role, but their scope for action is severely limited by a lack of resources, (2) they consider privacy as crucial but see it threatened by various difficulties of a legal nature, and (3) DPOs face challenges which can be traced back to a gap between their legal role and duties as well as between the regulatory requirements of privacy and those of their organization (Casutt and Ebert, 2020).

If, for some reason, the organization decides not to follow any advice provided by DPO, it should keep records of decisions and reasons for those decisions, it may help demonstrate accountability (Dibble, 2019). GDPR divides its administrative fines into two main categories. The first category of fines can be up to €10 million or in cases of an undertaking up to 2% of their total worldwide annual turnover of their preceding financial year, whichever is higher.

The following statistics shows the highest individual fines imposed (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Top 5 biggest GDPR Fines

Source: GDPR Fines Tracker & Statistics (2021).

The constant pace of business change allied with evolving legal interpretations require constant vigilance on the part of the DPO and create additional challenges for accountability (Ryan et al., 2020). It is important to emphasize that monitoring compliance with the GDPR inside an organization does not mean that the DPO shall be held personally liable for regulatory violations. The GDPR compliance is the responsibility of the data controller or data processor, not the DPO.

Conclusions

An organization must ensure and demonstrate compliance with all the principles of the GDPR, and the appointment of a DPO can be one of the measures required to implement the principle of accountability. According to the GDPR, non-compliant companies may face fines of up to 20 million euros or 4% of worldwide turnover and damage claims from violations. Companies stand to lose revenue as well as endure reputational damage should they breach the GDPR. The DPO must make sure that the organization complies with the GDPR and prevent any infringement on its provisions. The DPO must be appointed by public bodies or authorities and other organizations whose main activities are concerned with the large-scale and systematic monitoring of individuals, or with the large-scale processing of personal data ascribed to special categories. The provisions of the GDPR which lay down the criteria for the appointment of the DPO may be criticized for their lack of legal certainty and clarity, so that every individual situation must be assessed on a case-by-case basis, depending on the status of the organization and the nature of its activities insofar as they relate to data processing. In the absence of more specific legal regulation, the appointment of a DPO essentially depends on the data controller’s subjective perception of himself and his activities. However, the appointment of the DPO should be judged a sign of the organization’s corporate social responsibility for the impact of its decisions and activities on society through transparent and ethical conduct. Also, can facilitate compliance and become a competitive advantage. After the DPO has been appointed, the Inspectorate must be informed about this fact and provided with any information it may request. The Inspectorates state that one of the most common shortcomings when appointing a DPO is the choice of a particular position, which may be highly prone to conflicts of interest. One of the main criteria for assessing whether the given post may give rise to a conflict of interest is the possibility (powers) of determining the purpose for which the personal data are being processed, along with the means of doing so.

The DPO is to be appointed within an organization on the basis of his professional qualities, in particular, his expertise in data protection law and practice, as well as his capacity to perform the tasks referred to in Article 39 of the GDPR. In addition, in performing these tasks, the DPO should properly assess the risks inherent in data processing operations, having regard to the nature, scope, purpose, and context of the processing. The DPO should be able to perform his duties and tasks independently, whether or not he is an employee of the data controller, so his status within the organization is important. High-quality professional activities are possible only when grounded in precise knowledge pertaining to a specific field of activity. After the GDPR entered into force, the practical application thereof has been expanding rapidly, and has been influenced, among other things, by institutional isomorphism (mandatory, mimetic or normative).

The appointment of the DPO shall be communicated to all of the organization’s staff and he shall be involved in all matters relating to data protection at the earliest possible stage. The DPO must be provided with the support of the senior management, granted access to the other services available in the organization and given sufficient time to perform his functions. If necessary, an official team must be formed consisting of the DPO and the staff performing his tasks. The DPO must not receive instructions on how to deal with data protection issues. The DPO’s activities are governed by principles grounded in expert competence, independence, avoiding conflicts of interest, accessibility, and freedom of form.

The role and significance of the DPO will continue to grow, as will the tasks and activities of the DPO. This is due to the increasing complexity of processing operations, which requires DPOs to understand both the business needs, but also technical intricacies in more detail. It is important to emphasize that monitoring compliance with the GDPR inside an organization does not mean that the DPO shall be held personally liable for regulatory violations. The GDPR compliance is the responsibility of the data controller or data processor, not the DPO.

References

- Agostinelli, S., Maggi, F. M., Marrella, A., & Sapio, F. (2019). Achieving GDPR compliance of BPMN process models. In International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering, 10–22.

- Alford, S. (2020). GDPR: a Game of Snakes and Ladders. Routledge.

- Amayah, A. T. (2013). Determinants of knowledge sharing in a public sector organization. Journal of knowledge management, 17(3), 454–471.

- Article 29 Working Party (2016) Guidelines on Data Protection Officers (‘DPOs’). Available at http://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/document.cfm?doc_id=44100

- Bădescu, M. (2017). The Rationale Of Law. The Role And Importance Of The Logical Method Of Interpretation of Legal Norms. Challenges of the Knowledge Society, 384–392.

- Bamberger, K. A., & Mulligan, D. K. (2015). Privacy on the ground: driving corporate behavior in the United States and Europe. MIT Press.

- Batutytė, I. (2019). Ar asmens duomenys, kurie yra nuasmeninami, tačiau naudojami tiesioginės rinkodaros tikslais, papuola į naujojo ES BDAR reguliavimo sritį?: magistro darbas. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology, 1, 311–320.

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40.

- Brusoni, S. and Vaccaro, A. (2017). Ethics, Technology and Organizational Innovation, Journal of Business Ethics, 143 (2), 223–226.

- Casutt, N., & Ebert, N. (2020). Data Protection Officers: Figureheads of Privacy or Merely Decoration?. In 16th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance, Academic Conferences International limited.

- Chlivickas, E., Papšienė, P., Papšys, A. (2009). Žmogiškieji ištekliai: strateginio valdymo aspektai. Verslas, vadyba ir studijos, 7, 51–65.

- Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- CPO Magazine (2019). Data Protection and Privacy Officer Priorities 2019. Available at https://www.cpomagazine.com/download/7189/.

- Denham, E. (2019). A blog by Elizabeth Denham, Information Commissioner. Available at https://ico.org.uk/about-the-ico/news-and-events/blog-gdpr-one-year-on/

- Dibble, S. (2019). GDPR for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons.

- Drewer, D., & Miladinova, V. (2018). The canary in the data mine. Computer Law & Security Review, 34(4), 806–815.

- Eggl, B. (2019). Learning to walk a tightrope: Challenges DPOs face in the day-to-day exercise of their responsibilities. Journal of Data Protection & Privacy, 3(1), 69–81.

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Justice Consumers. (2018). BDAR: Naujos galimybės, naujos prievolės: Ką kiekviena įmonė turi žinoti apie ES bendrąjį duomenų apsaugos reglamentą. Luxembourg: Publications Office.

- European Data Protection Board (2019). BfDI imposes Fines on Telecommunications Service Providers. Available at https://edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2019/bfdi-imposes-fines-telecommunications-service-providers_en

- European Data Protection Board (2019). Hamburg Data Protection Commissioner‘s €51,000 fine against Facebook Germany GmbH. Available at https://edpb.europa.eu/news/national-news/2019/hamburg-data-protection-commissioners-eu51000-fine-against-facebook-germany_en.

- European Data Protection Supervisor. (2019). Bendrojo duomenų apsaugos reglamento (BDAR) taikymas ES institucijoms jūsų teisės skaitmeniniame amžiuje. Luxembourg: Publications Office.

- Gobeo, A., Fowler, C., & Buchanan, W. J. (2018). GDPR and Cyber Security for Business Information Systems. River Publishers.

- Hosseini, M. R., Tahsildari, H., Hashim, M. T., Tareq, M. A. (2014). The impact of people, process and technology on knowledge management. European Journal of business and Management, 6(28), 230–241.

- Yıldırım A, Şimşek H (2005). Methods of Qualitative Research in Social Sciences. Ankara: Seçkin Press.

- Jakštaitė, A. (2018). ES Bendrasis duomenų apsaugos reglamentas: Poveikis duomenų apsaugos teisei: magistro darbas. Vilnius: Vilniaus universitetas.

- Januševičienė, J. (2018). Praktiniai asmens sveikatos duomenų tvarkymo aspektai pagal Bendrąjį asmens duomenų apsaugos reglamentą. Teisė, 107, 111–28.

- Jucevičius, G., Bakanauskienė, I., Brasaitė, D., Bendaravičienė, R., Linkauskaitė, U., Staniulienė, S., ... & Žirgutis, V. (2017). Organizacijų valdymas neapibrėžtumų aplinkoje: teorija ir praktika. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas.

- Khan, J. (2018). The need for continuous compliance, Network Security, 2018(6), 14-15.

- Kvedaravičius, J. E., Stašys, R, Giedraitis, A. (2018). Vadovo kaip asmenybės vystymosi trajektorijos. Klaipėda: Klaipėdos universiteto leidykla.

- Lambert, P. (2017). Understanding the new European data protection rules. CRC Press.

- Lietuvos Respublikos asmens duomenų teisinės apsaugos įstatymas. (1996) Available at https://e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalAct/lt/TAD/TAIS.29193/asr.

- Limba, T., Driaunys, K., Kiškis, M., Šidlauskas, A. (2020). Development of Digital Contents: Privacy Policy Model under the General Data Protection Regulation and User Friendly Interface. Transformations in Business & Economics, 19(1), 21–42.

- Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., & Lampel, J. (2005). Strategy Safari: a guided tour through the wilds of strategic mangament. Simon and Schuster.

- Nerka, A. (2017). Powołanie inspektora ochrony danych jako przejaw społecznej odpowiedzialności biznesu. Annales. Etyka w życiu gospodarczym, 20(3), 107–119.

- Noreikaitė, R. (2014). Europos administracinė erdvė: Europos Sąjungos ir Lietuvos administracijos sąveika: magistro darbas. Kaunas: Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas.

- Oficiali Europos Sąjungos interneto svetainė (2020). Ar mano įmonei ar organizacijai reikia duomenų apsaugos pareigūno (DAP)?. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/.

- Petkevičiūtė, N., Balčiūnaitienė, A. (2018). Darnumo vystymas organizacijose: problemos ir iššūkiai. Visuomenės saugumas ir viešoji tvarka, 20, 232–260.

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2010). Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International journal of nursing studies, 47(11), 1451-1458.

- Privacy Affairs (2021). GDPR Fines Tracker & Statistics Available at https://www.privacyaffairs.com/gdpr-fines/

- Radžiūtė, G. (2018). ES Bendrasis duomenų apsaugos reglamentas kaip duomenų apsaugos teisės šaltinis: magistro darbas. Vilnius: Vilniaus universitetas.

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation).

- Ryan, P., Crane, M., & Brennan, R. (2020). Design Challenges for GDPR RegTech. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.12138.

- Sharma, S. (2019). Data privacy and GDPR handbook. John Wiley & Sons.

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333-339.

- Sterling, N., Kaltsounis, A. & McLellan, M. L. (2020). Belgian Authority Raises Red Flag for DPOs with Multiple Roles. Available at https://www.bakerdatacounsel.com/enforcement/belgian-authority-raises-red-flag-for-dpos-with-multiple-roles/.

- Šidlauskas, A. (2019). Opportunities for dpo (data protection officer) occupational training and improvement. INTED19: 13th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain. 11-13 March, 2019: Conference Proceedings, 808–814.

- Šidlauskas, A. (2019). Video Surveillance and the GDPR. Social Transformations in Contemporary Society (STICS 2019): Proceedings of an Annual International Conference for Young Researchers, 7, 55–65.

- Štareikė, E., Kausteklytė-Tunkevičienė, S. (2018). Pagrindinės duomenų subjekto teisės ir jų užtikrinimas pagal ES Bendrąjį duomenų apsaugos reglamentą. Visuomenės saugumas ir viešoji tvarka, 20, 293–312.

- Štitilis, D., Kiškis, M., Limba, T., Rotomskis, I., Agafonov, K., Gulevičiūtė, G. ir Panka, K. (2016). Interneto ir technologijų teisė. Vilnius: Registrų centras.

- Tikkinen-Piri, C., Rohunen, A., Markkula, J. (2018). EU general data protection regulation: changes and implications for personal data collecting companies. Computer Law & Security Review, 34(1), 134–153.

- Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14, 207–222.

- Vaitkevičius, V. (2016). Lyderystės vaidmuo formuojant žinių valdymui palankią organizacijos kultūrą: atvejo analizė. Informacijos mokslai, 76, 123–38.

- Vaitkevičius, V. (2018). Žinių vadybos reikšmė viešojo sektoriaus inovatyvumui. Informacijos Mokslai, 83, 36–51.

- Valstybinės duomenų apsaugos inspekcijos 2019 m. veiklos ataskaita (2020). Available at https://vdai.lrv.lt/lt/naujienos/vyriausybe-pritare-valstybines-duomenu-apsaugos-inspekcijos-2019-m-veiklos-ataskaitai.

- Valstybinės duomenų apsaugos inspekcijos interneto svetainė (2020). Duomenų apsaugos pareigūnas. Available at https://vdai.lrv.lt/lt/

- Voigt, P., Von dem Bussche, A. (2017). The eu general data protection regulation (GDPR). A Practical Guide, 1st Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Wilson, S. (2018). A framework for security technology cohesion in the era of the GDPR. Computer Fraud & Security, 2018(12), 8–11.

- Zakarevičius, P. (2013). Vadybos paradigma. Management of Organizations: Systematic Research, 68, 151–159.

- Zaleskis, J. (2017). Duomenų apsaugos pareigūno veiklos pagrindai pagal ES bendrąjį duomenų apsaugos reglamentą. Teisė, 104, 159–70.

- Zaleskis. J. (2019) Europos Sąjungos bendrasis duomenų apsaugos reglamentas ir asmens duomenų apsaugos teisė. Vilnius: Registrų centras.

- Zerlang, J. (2017). GDPR: a milestone in convergence for cyber-security and compliance, Network Security, 2017(6), 8-11.

- Žydžiūnaitė, V. (2018). Implementing ethical principles in social research: Challenges, possibilities and limitations. Profesinis rengimas: tyrimai ir realijos, 29, 19–43.