Socialiniai tyrimai eISSN 2351-6712

2023, vol. 46(1), pp. 24–52 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/Soctyr.2022.46.1.2

Milda Kiškytė

Vilniaus kolegija, Elektronikos ir informatikos fakultetas, Užsienio kalbų centras, anglų kalbos lektorė

Vilniaus kolegija / Higher Education Institution, Faculty of Electronics and Informatics, Foreign Languages Centre, English language lecturer

El. p.: m.kiskyte@eif.viko.lt

Summary. Recent studies showed that language knowledge has, increasingly, become a value-add attribute that helps businesses to implement and satisfy their corporate goals in the globalized world as its services are highly demanded by employers in parallel to so-called hard skills in job advertisements. The paper presents a quantitative content-based analysis of foreign language knowledge requirements listed in job advertisements. The study results are based on data assessment from online job websites. The scope of the study was five industries-information technology, finance and accounting, organization and management, technical engineering, and customer service in three Baltic States - Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. The dataset consists of one thousand four hundred forty-two (N=1442) job advertisements written in English, published on the job portal, and examined from September 2021 to September 2022. The study results revealed that foreign language communication has become an obligatory attribute of the examined industries in the Baltic States and an indispensable characteristic of any working position. Labour market in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia seeks a candidate with highly fluent foreign language skills, advanced expression of thoughts and communication, able efficiently to present thoughts, ideas or comments and communicate correctly.

Keywords: language knowledge, job advertisement, employability, business industry, the Baltic States.

Santrauka. Naujausi tyrimai rodo, kad kalbų mokėjimas vis dažniau yra suprantamas kaip pridėtinės vertės požymis darbo rinkoje, tiesiogiai padedantis verslui įgyvendinti savo tikslus globalioje rinkoje. Straipsnyje atlikta kiekybinė darbo skelbimų turinio analizė, siekiant išsiaiškinti darbdavių poreikį ir keliamus reikalavimus užsienio kalbos mokėjimui įsidarbinant. Tiriamąją imtį sudarė tūkstantis keturi šimtai keturiasdešimt du (n=1442) darbo skelbimai, skelbiami Lietuvos, Latvijos ir Estijos darbo rinkai populiariose įsidarbinimo svetainėse. Buvo pasirinktos penkios verslo paslaugų sektoriaus pramonės šakos, informacinės technologijos, finansai ir apskaita, klientų aptarnavimas, verslo vadyba ir inžinerija atitinkamai Lietuvoje, Latvijoje ir Estijoje. Darbo skelbimai buvo surinkti ir peržvelgti nuo 2021 metų rugsėjo mėnesio iki 2022 metų rugsėjo mėnesio. Tyrimas atskleidė, kad poreikis mokėti užsienio kalbą Baltijos šalių rinkose yra aukštas ir, kad užsienio kalbų mokėjimas įsidarbinant yra lygiagrečiai svarbus moksliniam žinojimui visose Baltijos šalyse. Tyrimo rezultatai parodė, kad šiandien rinkai reikalingas darbuotojas, gebantis sklandžiai ar labai sklandžiai komunikuoti užsienio kalba raštu ir žodžiu, mokantis kelias užsienio kalbas, įvairiais aspektais galimai įgyja konkurencinį pranašumą.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: kalbos mokėjimas, darbo skelbimas, įsidarbinimas, verslo pramonės šaka, Baltijos šalys.

________

Received: 03/01/2023. Accepted: 14/03/2023

Copyright © Milda Kiškytė, 2023. Published by Vilnius University Press.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

It has become obvious that investing in language skills is an important prerequisite for increasing growth and competitiveness in the labour market. According to the Languages for Jobs report (European Commission, 2010), demand for foreign language skills in the European labour market is steadily rising and also bound to increase in the short- to medium-term future. The European Commission has published a broad-spectrum Communication: Rethinking education: investing in skills for better socioeconomic outcomes (European Commission, 2012) where economic value is linked to the impact of education and training planning processes. According to the Communication, investment in education and training is essential for developing skills to increase economic growth, create jobs, promote employability, and increase competitiveness in the labour market. Therefore, the Commission sets language skills apart from other skills and indicates that languages are particularly important. It argues that the effect of languages is a premium attribute to increase the level of employability and to be a factor of competitiveness: “…foreign language proficiency is one of the main determinants of learning and professional mobility, as well as of domestic and international employability. Poor language skills, thus constitute a major obstacle to free movement of workers and to the international competitiveness of EU enterprises. […] it is clear, however, that the benefits of improved language learning go well beyond the immediate economic advantages, encompassing a range of cultural, cognitive, social, civic, academic and security aspects (European Commission, 2012b). Moreover, as such, language knowledge serves as a tool to support a functional multilingual economy (European Commission, 2012b). Thus, the gradual transition from understanding the cultural or cognitive aspects of language learning to defining the impact of language effect on economic growth and a factor competitiveness can be observed in EU language policy documents.

To enhance employability, competitiveness of workers, Barcelona European Council (2002) based on the results of the European Survey Council Language Competence, set an objective to achieve the mother tongue plus two other languages.

The 2008 Council Resolution on a European Strategy for multilingualism (Council Resolution, 2008) further defined multilingualism as a factor for the competitiveness of the European economy and the mobility and employability of people. It highlighted the need to support languages so that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can “broaden their access to markets”, “promote language skills in professional development”, “offer job-specific language courses in vocational education and training (VET)” and “use of the linguistic competences of citizens with a migrant background”.

In addition, the 2008 Communication on Multilingualism: an asset for Europe and a shared commitment (European Commission, 2008), establishes a link between languages and employability, pointing out that the development of language skills will increase worker mobility and improve the employability of the European workforce.

The Framework for Key Competences (2006) and the EU Council list the competence of foreign language communication as second in a list of other key competences for lifelong learning (EP, RE, 2006), which includes the following:

1. Communication in the mother tongue.

2. Communication in foreign languages.

3. Mathematical competence and basic competences in science and technology.

4. Digital competence.

5. Learning to learn.

6. Social and civic competences.

7. Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship.

Aim of the study: To determine the significance of language knowledge for employability. The objective of the study is to determine how important foreign languages are, which languages are demanded the most and how this differs across countries and occupations.

The research question addressed in the present study is:

RQ1: What is the effect of foreign language skills on employability across industries in the Baltic region?

The proposed hypotheses that will be tested are:

H 1: It is assumed that language knowledge has a crucial impact on employability.

H 2: It is assumed that a demand for language knowledge is in line to so-called hard skills.

The present study is based on the assumption that foreign language skills increase employability and competitiveness in the labour market and imply that the ability to communicate with people in the professional field, is becoming increasingly important for many employers. However, there is a surprising lack of empirical studies examining labour market requirements in relation to language in three Baltic countries. Thus, in the context of the objectives of the present study, identifying trends, establishing current labour market needs and anticipating future needs in the Baltic Sea region in relation to the linguistic dimension, could fill the existing gap in empirical studies. The results of the study could potentially be relevant for institutions such as the labour exchange or language policy makers, who are the main source for bridging a link between this form of human capital and the labour market.

Literature review

Recent studies establish a de facto relationship between language skills and the economy, considering language skills as a form of human capital and introducing it as ‘linguanomics’ or ‘the economy of language’, which embraces such language functions as the influence of language on employment rates, effective communication in business, international trade, negotiations and settlement procedures, political activities (Holmes, 2018; Ayres-Bennet et al. 2022; Costa et al. 2017; Kostic-Bobanovic et al. 2016; Gazzola and Mazzacani, 2019).

There is a large empirical literature examining the effect of foreign language skills on employability. The first major group of studies focuses on migrant workers and shows that foreign language proficiency, in particular English, is associated with a higher wage premiums (Fabo, Beblavy and Lenaerts, 2017; Gazzola and Mazzacani, 2019; Dustmann and Fabbri, 2003; Guven and Islam, 2015; Chiswick and Miller, 2002). However, this is outside the scope of the present study objectives and is therefore not addressed in the present study. The second group of empirical literature investigates the impact of knowing the language of the host country on employability opportunities (Chiswick and Miller, 2015; Aldashev et al., 2009; Bormann et al. 2019). The third group of studies examine the relationship between foreign (second) language skills and the employment opportunities of the residents. This group of articles is closer to the present study aim and objectives. Also, it is worth to mention that most of empirical literature estimate English language skills as premium skills in non-English speaking countries of residents.

The cross-national and cross-country study conducted by Cambridge English and titled English at work: global analysis of language skills in the workplace (2016) introduced a series of questions about English language skills in the workplace. 5,373 employers, in 38 countries/territories and 20 different industries participated in the study and answered the questions about English language skills in the workplace. The study focused on the demands for English level at workplace, English language skills gap, researched economic value of the employees with a higher level of English comparing across countries and industries examined. Overall, the survey shows that English language skills are important for over 95% of employers in many countries and territories where English is not an official language. Also, the report predicts that English language skills demand due to the globalisation will grow even further.

The cross-country study by Gazzola and Mazzacani (2019) examined the relationship between foreign language skills and the employment status of adult native citizens in three EU countries - Germany, Italy and Spain. The results of the study show that very good language skills are associated with a higher probability of being employed than sufficient or good skills. The proposed results suggest that people who want to remain employable and meet the demands of the labour market should have good language skills.

The study The importance of foreign language skills in the labour markets of Central and Eastern Europe: assessment based on data from online job portals by Fabo, Beblavy and Lenaerts (2017) examines the role of foreign language skills in the Visegrad Four countries’ labour markets. The results of the study indicate that in the Visegrad region skills in English, and to a lesser extent German, are in high demand.

The existing evidence in the empirical literature suggests that poor language skills are a serious barrier to employability. The findings of Aldashev, Gerandt and Thomsen (2009) show that immigrants speaking the language of the host country significantly increase their participation in labour market and the probability of employment and are less likely to become unemployed. Similarly, Dustmann and Fabbri (2003), who studied the effects of language on the income and employment of non-white immigrants, also point out that language skills have a positive effect on labour market opportunities.

However, there is a significant lack of empirical studies on the effect of foreign language for employability in the Baltic region. Few empirical studies investigate Estonian labour market in relation to language skills. The study by Toomet (2011) examined the return to proficiency in the dominant language for ethnic Russians in the Baltic States and found no evidence of a host country language premium for Russian minority men in Estonia. Bormann et al. (2019) aimed to analyse the relationship between skills in the Estonian, Russian and English language, and labour market outcomes in Estonia. The authors used the 2000-2012 Estonian Labor Force Surveys. The authors examined 25-55 years of age and grouped the workers into four groups: ethnic Estonian men and women, Russian-speaking minority men and women. The study found that Ethnic Russian men do not earn any premium from speaking Estonian, while women, fluent in Estonian earn approximately 10 per cent more. Unfortunately, there are no significant empirical studies on language effect for employability in Latvia and Lithuania.

Collectively, these studies outline that the contribution of foreign languages to employability, competitiveness and performance is thus too obvious to be doubted.

Language competence presents a set of language skills and language experience. In job postings language competence is presented as literacy in official language, literacy in foreign (second) language, literacy in English. This means that the language user has to have a solid knowledge of the elements of the language system and the elements of its respective subsystems in his/her individual language awareness. According to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08), skills can be divided into three broadly overlapping groups: 1) cognitive skills are mental abilities, 2) socio-emotional skills are attitudes and behaviours that enable individuals to cope effectively with personal and social situations, 3) technical skills are the specific knowledge required to perform a job, e.g. knowledge of production and processing and knowledge of markets. Technical skills also include technology: digital skills, including the ability to use computer tools. Jackson (2007), Brunello & Schlotter (2011), Dörfler & van de Werfhorst (2009) categorize skills into cognitive skills and cognitively acquired abilities (specific and generic), and non-cognitive skills, which further is divided into personal characteristics and social skills. Similar studies on other countries usually only distinguish cognitive and socioemotional skills or use their own taxonomy. Beblavy et al. (2016) split socioemotional skills into two categories, social and personal skills, in studies on Slovakia. Kurekova et al. (2016) use the Big Five Personality Traits taxonomy. In all previously mentioned studies knowledge of foreign languages are considered cognitively-acquired and also referred to specific skills. In addition, the European Commission (2015) devised a more detailed skill classification for Europe. The European Commission treats competences as links between an individual’s occupation and qualifications. The latter is defined as a ‘formal outcome of an assessment and validation process which is obtained when a competent body determines that an individual has achieved learning outcomes to given standards’ (European Commission 2015). In addition, the European Commission distinguishes between job-specific and transversal competences. The transversal competences are divided into five categories, with two to five subcategories divided by classes (43 in all) with language skills categorized in line with communication competence: non-verbal and verbal communication, mother tongue and foreign language.

However, the range of requirements for language competence depends on the communication situations and topics.

Previous research have confirmed that, along with the requirement for professional experience and educational level, language skills are the most frequently mentioned requirement in job advertisements and that this trend is likely to continue in the future (Cambridge English, 2016).

Pater, Szkola, Kozak (2019) in their study examined transversal competences in the Polish labour market using the method which involved collecting online job offers and analysing them with data mining and text analysis tools. The study revealed that the competences mentioned most frequently were those related to ‘language and communication’ while neglecting the other competencies in the job postings. In addition, the foreign languages in greatest demand were ‘English’ and ‘German.’ Similarly, Kurekova, Beblavy and Haita (2012) conducted an empirical study using the largest job portal in Slovakia, and focusing on the specific skills required by employers in the Slovak labour market. Their study showed that language skills, in addition to other skills listed in the job advertisement, are in demand in a large part of the professions, both on the domestic and foreign markets. The study by Muler and Safir (2019), using data from the World Bank, estimated employer demand for cognitive, socio-emotional and technical skills among employees and examined online job postings on Ukrainian job websites. The study found that foreign language skills account for a significantly higher share of demand than other specific-cognitive skills across all job postings in the same category, and rank second among the other fourteen cognitive skills after communication skills.

The corss-industry and cross-occupations study Job Creation and Demand for Skills in Kosovo: What Can We Learn from Job Portal Data? by Brancatelli, Marguerie, Brodmann (2020) provided an analysis of skill demand across industries and occupations. The study precisely measured the requirements for each skill in the job posting. The main finding of the research is that foreign language skills, extraversion and computer skills are most in demand across all industries and occupations and listed. More precisely, the study found that English is a key skill requirement in the labour market in Kosovo. Beadle, Humburg, Smith and Vale (2015) put the Barcelona 2002 target at the forefront of their study and reported key findings from research activities focusing on the benefits of foreign language skills in the labour market. The study found that foreign language skills improve career opportunities and is a part of a broader set of skills and experiences (e.g. educational background, work experience).

Participant profile

Attractive geographical location makes the Baltic States to become a bridge between Western and Eastern countries. The three Baltic states are often treated as a single economical unit sharing similar economic structure, demography, and market size. In 2020, the population in millions of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania was 1.331million, 1.875 million and 2.805 million, respectively (Eurostat, 2022). The largest market size in relation to population is in Lithuania and it is the smallest in Estonia. Under the World Bank’s classification of countries in 2022, employers from Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia belong to high-income economies with $13,205 per capita or more (The Word Bank, 2020).

In 2020, Lithuania created 15 jobs for 1million residents, Latvia 11 jobs for 1 million residents, Estonia 1 job for 1million residents. (EY, 2021). Thus, in 2020 Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were ranked as the 2nd, the 5th and the 30th in Europe for job creations, respectively.

The Baltic countries position themselves as business-friendly environment, which includes a multi-lingual and productive workforce, advanced IT infrastructure and e-commerce, a growing economy and low country risk with less expensive labour force. For example, Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian labour costs are four times lower than the EU average with 14.5 €, 11.1 € and 11.3 € (Eurostat, 2021). Employee turnover in Lithuania is less than 2 % for international manufacturing firms and 8 % for those in services. Or the level of compensation for unskilled jobs is three to four times lower than in such Western European countries as Germany and France, while in terms of wage adjusted labour productivity Latvia is ahead of most EU member states.

Choosing the right country for shared service locations is critical to successful outsourcing and the key factors in selecting the right location are still those related to labour: quality, cost and language skills. Due to similar cultures and business practices, Scandinavian countries, Germany, the UK and the US are major investors and have used investment in the Baltics to extend their home market - especially in the manufacturing, transport, finance, and IT sectors.

Despite the less expensive workforce, education levels in the Baltics are high. For example, over 50 % of Latvian, Estonian and Lithuanian population speaks more than two languages and around 93 % has a secondary or higher education, 20 % more than the EU average. In addition, nearly half of all people aged 24-29 have a university degree, the most in the EU. It also helps investors’ long-term prospects that employees are not just qualified, they are loyal (Eurostat, 2021).

It is important for investors to easily access their subsidiary from abroad. All business sectors, which participated in the study, belong to tertiary sector of economy to service support field. Information and communication technology (hereinafter IT), finance and accounting, management and organization, technical engineering and service industry are the participants of the research. Using Eurostat data, the fastest developing sector in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia is information and communications technology with 42k IT specialists employed (Invest Lithuania, n.d.) in Lithuania, 36k people employed in Latvia (Invest Latvia, n.d.) and with workforce of over 20k people in Estonia (Invest Estonia, n.d.). Also, the most demand for IT professionals was obvious from the highest number of the offered occupations compared to other on the job portal. On the portal IT sector lists such occupational fields as software development (front end), software development (back end), IT service desk, cloud operations, infrastructure development, big data analytics, data science, business intelligence, cyber security, infrastructure management, artificial intelligence.

Financial services are fast growing activity and among well-paid sectors in all three countries. It is rated as the second sector after IT with the considerably high number of the offered job vacancies on the portal. The main characteristics of finance sector in the Baltics is that it is dominated by Nordic banks and business units. Swedbank (Sweden), SEB bank (Sweden), DNB (Norway), Nordea bank (Finland) cover a large majority of the banking sector in three Baltics. Finance and accounting business sector employs financial/accounting/compliance/tax analysts, finance specialists, accountants, business analysts, accounting operations specialists, accounting, and sales assistants.

Business services and public administration are smaller sectors in all three countries. Management and organization business sector covers such occupations as marketing manager, business development manager, accounting and sales assistant, project manager, compliance consultant, product manager, human resource manager. Service industry – client service representatives, product support representatives, field sales representatives.

Technical engineering business sector is the sector which has the lowest number of the job postings on the examined portal across all Baltic countries under the reviewed period. It involves skilled manual workers or elementary occupations. The latter group covers those providing domestic help, cleaners, refuse collectors, as well as those who manually assemble components, sort, pack or deliver goods.

Bilingualism or even trilingualism is the norm of the labour force in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. The population of the Baltic States demonstrated a high degree of multilingualism compared to other EU Member States (Eurostat, 2019). Using foreign language skills statistics conducted by Eurostat in 2019, 9 out of every 10 individuals of working-age knew at least one foreign language in the Baltic States. 95.7 %, 95.6 % and 91.2 % inhabitants of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia are at least bilingual, respectively. These figures are explained that a large majority of people aged 45+ are well educated in Russian language or even German while significantly lacking English skills. Whereas younger generations learnt English since early ages (Eurostat, 2019). Also, it could be explained by de facto multiethnic settings in connection with citizenship and political participation, population distribution and labour market surrounding. The demand to know certain languages at work is directly related to the trade links with the neighbouring countries. For example, it is relatively common for people from some of the Baltic to understand the languages of some of their neighbours (Vihalemm and Hogan-Brun, 2013a). Despite high trading links of the Baltic region with Russia, at the same time, there are some differences between the three countries such as Finland and Sweden are more important trade partners for Estonia, while Lithuania and Latvia have larger trade links with Poland (Poissonnier, 2017). Consequently, the Baltic linguistic situation is evolving into a complex multilingual environment where a variety of languages now are gaining salience.

Methodology

The paper presents a sector-by-sector and country-by-country comparison of the required language knowledge qualification for employability. The dataset consists of one thousand four hundred forty two (N=1442) job postings written in English, published on CV-Online job portal. The following job advertising portal was selected, first, because it combines job advertisements from three Baltic states with each having their own national domain (CVonline.lt/ CVonline.lv/ CVonline.ee). Second, because it is one of the leading job portals in the Baltics with 2000 companies published>65,5 K job ads/year and 5500 new job ads/month and well-known among skilled specialists. Finally, it covers different categories of competitive employers, who advertise job positions across all industries, locations, occupations for the job seekers in three Baltic countries.

The job postings were examined between September 2021 and September 2022 across three Baltic states – Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and five business sectors: information technology, finance and accounting, organization and management, technical engineering, customer industry.

The demands for language at work were researched according to five domains. For this purpose, I constructed a classification framework wherein five categories were determined to define the meaning of language for employability: (1) how many job advertisements list language skills among the qualifications and skills required, (2) language ‘levels of priority’ among other qualifications and skills in the job posting, (3) required language proficiency level, (4) required language skills, (5) demand for multiple languages listed in the job advertisement. However, this study does not consider other elements of job offers in relation to language knowledge, such as requirements for certain occupational skills, or detailed job-related competences.

The single website to collect the job ads was chosen purposefully, to ensure that the examined job postings are without any duplicates on another websites. The job postings, written entirely in English language, were selected successively in the same order as they were posted online. The study purposefully ignored the size and legal type of the organization, offered job vacancy, complexity of occupation, and exclusively focused only on language dimension listed in the job advertisement aiming to identify the effect of foreign language on employability.

For each business sector, I, first, considered the number of job advertisements available on the portal and used t-test to measure the validity of confidence level of participants in the study. Considering the different market size of each examined business sector across countries, 95 % of confidence level within ± 10 % margin of the value was used to calculate the minimum number of necessary job advertisements to meet the desired statistical constraints. Note, however, that in some cases a single job advertisement was posted for several occupations on the same job posting website. Thus, taking 95% confidence level allowed to calculate the job advertisements which were sampled multiple times, and interval estimates made on each occasion, in approximately 95 % of the cases. Second, I decided to expand the recommended scope of the study, not increasing or decreasing ± 10 % margin, and equalized the number of job postings to a hundred across each sector. Thus, having examined around five hundred job ads per country and one thousand four hundred forty-two job (N=1442) advertisements across industries and countries. Table below displays the number of job advertisements for different sized markets across each sector and country in relation to the total job ads number available on the portal and ±10 % margin of error in the examined sectors under the reviewed period.

In the next step, I acquired percentage share of job advertisements across each country corresponding to the total number of job advertisements available on the portal under the reviewed period. The results showed that the recent study examined not a lesser share than 10 % of each market across examined business sector seprately. These numbers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the number and % share of job advertisements included in the study in relation to the total number of job postings available on the portal

|

Country |

Business sector |

Total size of participants available |

Size of participants based on ±10% margin of error |

Size of participants included in the study |

% of market share of participants included in the study |

|

Lithuania |

IT |

752 |

86 |

100 |

13.29 % |

|

Service industry |

647 |

84 |

100 |

13.29 % |

|

|

Finance and accounting |

484 |

81 |

100 |

20.66 % |

|

|

Management and organization |

404 |

78 |

100 |

24.75 % |

|

|

Technical engineering |

288 |

73 |

100 |

34.72 % |

|

|

Latvia |

IT |

792 |

86 |

100 |

12.62 % |

|

Service industry |

606 |

84 |

100 |

16.50 % |

|

|

Finance and accounting |

372 |

77 |

100 |

26.88 % |

|

|

Management and organization |

390 |

78 |

100 |

25.64 % |

|

|

Technical engineering |

407 |

78 |

100 |

24.57 % |

|

|

Estonia |

IT |

407 |

78 |

100 |

24.57 % |

|

Service industry |

417 |

79 |

100 |

23.98 % |

|

|

Finance and accounting |

188 |

64 |

100 |

53.88 % |

|

|

Management and organization |

132 |

56 |

100 |

75.75 % |

|

|

Technical engineering |

99 |

49 |

42 |

42.42 % |

|

|

Grand total |

6385 |

1131 |

1442 |

100% |

Results

To determine the position of language, I, first, obtained the number of job advertisements which listed language skills among other qualifications and skills in relation to the industry but disregarding the country. The presence of language dimension in the job advertisement helped to assess the demand of language knowledge at work across the industries in general. Note, however, that the job advertisements, written entirely in English language, participated in the recent study. Thus, the absence of demand for language dimension could be understood as self-explanatory requirement of an employer to target employees with foreign language knowledge and even people from abroad. The data was achieved with respect to the frequency of occurence relative to the total number of requirements for language knowledge listed in the job posting.

The table below overviews data of percentage share in descending order of job advertisements, which listed language knowledge across each industry disregarding the country. The obtained figures may support the view that employers for all jobs with 8 in 10 (84.33 %) (N=1217) are keen to engage people who have language communication skills whereas around 2 in 10 (15.67 %) job postings do not list any requirements to possess language communication skills (N=225).

Table 2. Percentage share of job advertisements which listed language knowledge across each industry disregarding the country

|

Industry |

% of vacancies that require language skills |

% of vacancies that do not list language skills |

|

Finance and accounting |

95.67 % |

4.33 % |

|

Service industry |

94.33 % |

5.67 % |

|

Management and organization |

83.67 % |

16.33 % |

|

IT |

73.67 % |

26.33 % |

|

Technical engineering |

71.90 % |

28.10 % |

|

Grand Total |

84.33 % |

15.67 % |

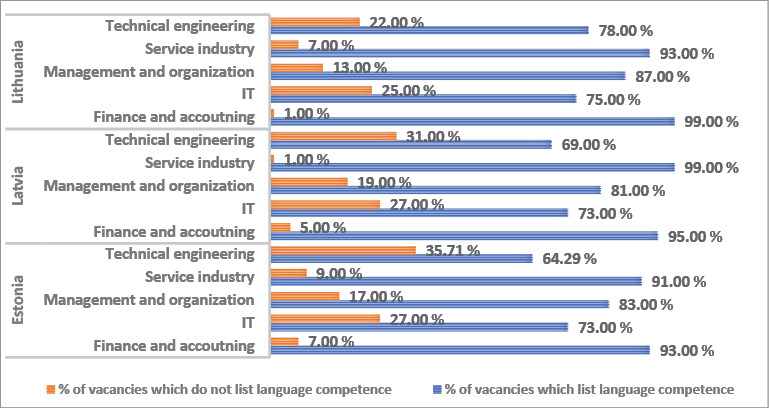

In the second step, I acquired percentage of the job advertisements which require language knowledge across the industries in relation to the country. The highest number of employers, with 10 in 10 vacancies across the three countries, which list language qualification, are in finance and accounting, 99 % in Lithuania, 95 % in Latvia and 93 % in Estonia. 9 in 10 of vacancies require language knowledge in service industry across all countries, with 93 % in Lithuania, 99 % in Latvia and 91 % in Estonia. Of organization and management sector, 8 in 10 employers list language as necessary skill with 87 % in Lithuania, 81 % in Latvia and 83 % in Estonia. 7 in 10 employers demand language skills in technical engineering and IT business sectors with 75 % in Lithuania, 73 % in Latvia and Estonia.

In addition, from 15.67 % of the job advertisements published on the portal, which did not include language knowledge into the listing of the qualifications and skills across the countries, the major share of the language position absence is observed in IT sector, with 3 in 10 employers in Lithuania (25 %), Latvia (27 %) and Estonia (27 %). Slight differences between the countries are in technical engineering sector, with 2 in 10 (22 %), 3 in 10 (31 %) and 4 in 10 (36 %) vacancies in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, respectively. Relatively lower % share is observed in organization and management business sector where 1 in 10 in Lithuania (13 %), 2 in 10 (19 %) in Latvia (19 %) and Estonia (17 %) of jobs do not include language knowledge into the list of qualifications and skills required. The numbers are reported in the figure below.

The figures demonstrate that % share of the job advertisements, which list demand for language knowledge, is very similar across all the countries in the examined business sectors.

Figure 1. Percentage of job advertisements which list language knowledge in relation to country

The following section presents distribution of language prioritization levels in the job advertisements across the examined business sectors in the Baltics. The results in this section were calculated according to a 5-point Likert-priority scale. The scale helped to establish a degree of language knowledge importance at work among other qualifications and skills listed in the job advertisement. The table below presents attributes on each level of the scale defined with a numerical rating. Note, however, that only the number of job advertisements, which listed language knowledge among other qualifications and skills, participated in this part (N=1217) of the study.

Table 3. A 5-point prioritization Likert scale

|

Degree of importance |

Definition |

Explanation |

|

1 |

Not a priority |

Equal importance |

|

2 |

Low priority |

Moderately favours one element over another |

|

3 |

Medium priority |

Strongly favours one element over another |

|

4 |

High priority |

One element is favoured very strongly over another |

|

5 |

Essential |

The evidence favouring one element over another is on the highest possible order |

To establish the level of language priority in the job posting, few steps were employed:

(1) determining the mean of the value score of every single requirement listed in the ranking order in the job advertisement in relation to the total number of values in the scale of prioritization.

(2) identifying the mean of the value score of the rank number of the language knowledge in a ranking order in the job posting with regards to the total number of values in the scale of prioritization that will eventually lead to establishing language level of importance or the relative importance.

To find the mean of the value scores of every single requirement and the mean of the rank number of the language knowledge in the job posting with regards to the values in prioritization scale, the results were achieved by calculating a proportion. The following proportion formula was implied:

Next, the obtained mean was assigned to the relative importance value listed in the levels of priority scale. In the study case, this number differed from one job posting to another in relation to the rank number of language skills and the total number of requirements listed in the job advertisement. Subsequently, the job advertisements were ranked according to the language knowledge priority level for each vacancy across the industries.

It was observed that the demands for language knowledge under category ‘not a priority’ usually were listed as the last position in the listing among all the requirements in the job posting. Relatively similar low positions in the listing took the category ‘low priority’. The demands labeled as ‘medium priority’ and ‘high priority’ mainly were in the middle to the top positions, but not the first in the listing among all the requirements in the job posting. The position ‘essential’ was among the first two requirements, depending on the number of the qualifications listed in total, to other competences in the job advertisement.

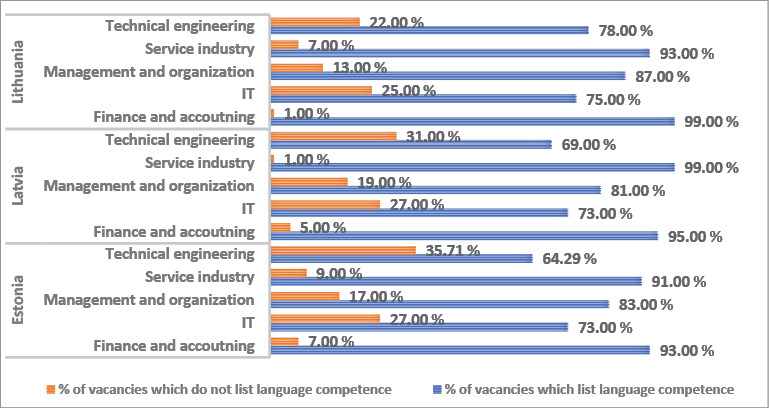

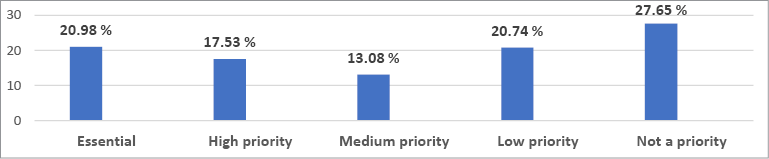

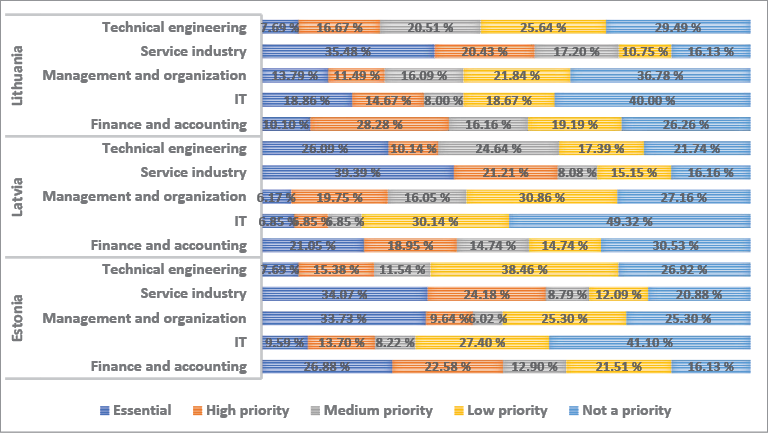

The examined data revealed that very similar proportions of ‘levels of priority’ fell among all industries across three Baltic states. A higher share of employers considers language skills as a value-add across all examined industries. ‘High priority’ includes the following categories: ‘essential’ (20.98 %), ‘high priority’ (17.53 %), ‘medium priority’ (13.08%), which is 51.61% in total. However, a lesser part of the employers stated that language knowledge is important but not of key importance. ‘Medium priority’ includes the categories of ‘low priority’ (27.65 %) or ‘not a priority’ (20.74 %) categories, which is in total 48.49 %. The figure below presents data how language levels of priority distributed across all industries disregarding the country.

Figure 2. Distribution of % share of levels of language knowledge priority across industries disregarding the country

The table below overviews data of percentage share of job advertisements across industries, which listed language knowledge under the category ‘of high priority’ disregarding the country. The results reveal that language knowledge is considered of key importance skill in service industry, finance and accounting businesses, with around 3 in 10 employers listing language knowledge as very important in-service industry (31.42 %) and finance and accounting (26.16 %) business sectors. Around 2 in 10 employers consider language knowledge as very important in management and organization businesses (17.70 %). Considerably lower percentage of the employers in technical engineering (13.72 %) and IT industry (11 %) list language abilities in the top positions. The numbers are reported in the figure below.

Table 4. Percentage share of industries which listed language knowledge as of ‘high priority’ across each industry disregarding the country

|

Industry Priority level |

Finance and accounting |

IT |

Management and organization |

Service industry |

Technical engineering |

|

Essential |

21.57 % |

10.20 % |

17.65 % |

40.39 % |

10.20 % |

|

High priority |

31.46 % |

12.21 % |

15.96 % |

29.11 % |

11.27 % |

|

Medium priority |

26.42 % |

10.69 % |

20.13 % |

20.13 % |

22.64 % |

|

Grand Total |

26.16 % |

11.00 % |

17.70 % |

31.42 % |

13.72 % |

The table below reports the distribution of % share of industries, which listed language skills in the last positions among all the requirements in the job advertisement. Around a third (25.85 %) of employers in IT sector require language skills but not as prior qualification in the listing. A fifth of IT recruiters (22.22 %) listed demand for language skills as of ‘low priority’ and a third (28.57 %) as of ‘not a priority’. Around a fourth (23.81 %) of the advertisements in management and organization sector listed language skills in the last positions among other skills in the job posting. Around a third of recruiters (25.79 %) consider demand for language as of ‘low priority’ and a fifth (22.32 %) as ‘not a priority’ listing language skill as the last requirement in the listing. Considerably a high number of the vacancies in management and organization sector, with around 2 in 10 (23.81 %) employers, listed language skills in the last positions. Around 2 in 10 employers consider language skills among other qualifications and skills in the job advertisement as of ‘low priority’ (21.03 %) and ‘not a priority’ (20.83 %). Relatively lower share of businesses in technical engineering (14.80 %) and service industry (14.63 %) listed demand for language skills in the last positions. The numbers are reported in the figure below.

Table 5. Percentage share of industries which listed language knowledge as ‘of low priority’ across each industry disregarding the country

|

Industry Priority |

Finance and accounting |

IT |

Management and organization |

Service industry |

Technical engineering |

|

Low priority |

21.03 % |

22.22 % |

25.79 % |

14.29 % |

16.67 % |

|

Not a priority |

20.83 % |

28.57 % |

22.32 % |

14.88 % |

13.39 % |

|

Grand Total |

20.92 % |

25.85 % |

23.81 % |

14.63 % |

14.80 % |

The figure below presents the distribution of language priority levels in relation to industry and country. The figures demonstrate that the highest share of job advertisements, which listed language skills in the first positions among other qualifications and skills, was recorded in service industry (31.42 %) and finance and accounting (26.16 %) businesses for the vacancies such as clerical support, service and sales managers, finance specialists, business analysts. This was considerably higher than for the IT and technical engineering sectors, with around one tenth (14.80 %) in technical engineering to a fourth (25.85 %) (IT) of the job postings which listed the language skills in the last rank numbers in ranking order of the qualification required. The rest figures demonstrate that % share distribution of language priority levels in the job postings, is very similar industry-by-industry and country-by-country.

Figure 3. Distribution of language knowledge priority levels at work across industries in relation to the country

The main conclusions for language status and language ‘priority’ levels:

1. Considerably major part (84.33 %) of the job advertisements list language qualification as important for the demanded vacancy. Only 15.67 % of job postings do not list any requirement for language competence. Note, however, that the job advertisements, written entirely in English language, participated in the recent study. Thus, the absence of demand for language dimension could be understood as self-explanatory requirement of an employer to hire people with the required foreign language skills or employers from oversees.

2. The % share between considering language competence as ‘of high importance’ and ‘of low importance’ is similar. In total 51.61 % of the employers consider language qualification as of ‘high importance’. However, a lesser part of the employers stated that language knowledge is important but not of key importance. ‘Medium priority’ includes the categories of ‘low priority’ (27.65 %) or ‘not a priority’ (20.74 %) categories, which is in total 48.49 %.

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (hereinafter CEFR) was used to determine language proficiency level required by the employers in the job advertisements. CEFR groups language learners into concrete proficiency domains, divides proficiency into six sub-levels – A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2. A corresponds to “Basic” levels, B to “Independent”, and C to “Advanced (Proficient).” A1 to A2 Beginner (Basic user) refers to the users with very basic to basic knowledge with frequent errors and situation-specific vocabulary. B1 (Intermediate user) level describes the speaker who makes frequent errors with new or complex words and uses adapted to a broad range vocabulary of circumstances. B2 (Independent user) makes occasional errors with new or complex words and possesses extensive knowledge of conversational English plus some basic technical vocabulary related to work or personal hobbies. A C1 (Advanced user) language user makes infrequent errors with new or complex words and has extensive knowledge of conversational English and technical vocabulary. A C2 proficiency level refers to the user with very infrequent errors and extensive knowledge of conversational English and technical vocabulary.

However, the descriptions to define language proficiency level in the job postings differ from those presented in CEFR. The most frequently used descriptions for language proficiency found in the job postings across the investigated industries were native speaker, fluent/excellent/advanced/strong/solid/high/effective/smooth/outstanding/proficient/good/

very good working knowledge/basic command of language and communication skills.

To find the demanded level of language proficiency in the job advertisement, the job postings were grouped according to the meaning of the descriptions for language proficiency used in the job advertisement in relation to the definitions for language abilities provided in CEFR. The table below presents the descriptions of language proficiency used in the job advertisements and their equivalent level in CEFR.

Table 6. Overview of the descriptions of language proficiency levels in the job advertisements and their approximate level in CEFR

|

Descriptions of language proficiency level |

Description of language proficiency level in CEFR |

|

Native speaker |

- |

|

Fluent, smooth, effective |

C2 (Proficient user) |

|

Proficient, excellent, advanced, high, outstanding |

C1 (Proficient user) |

|

Very good (command/working knowledge) |

B2 (Independent user) |

|

Good (command/working knowledge) |

B1 (Independent user) |

|

Basic communication skills |

A1 to A2 (Basic user) |

The final data in this part of the study were achieved with respect to the frequency of occurence relative to the total number of proficiency levels listed in the job posting. The figures in the graph below demonstrate % share of language proficiency levels across the investigated industries disregarding the country. A relatively high share of the job advertisements with 7 in 10 (68.09 %) businesses across all industries and countries require a candidate to possess language at an advanced to fluent (C1 to C2) levels with similar distribution in % across all industries. Considerably lower share of job postings, with only 3 in 10 advertisements, listed a requirement for independent user (B1 to B2) (29.77 %) across all examined industries. Almost no businesses require a candidate to be a ‘native speaker’ (0.82 %) or possess language at A1 to A2 level (1.32 %).

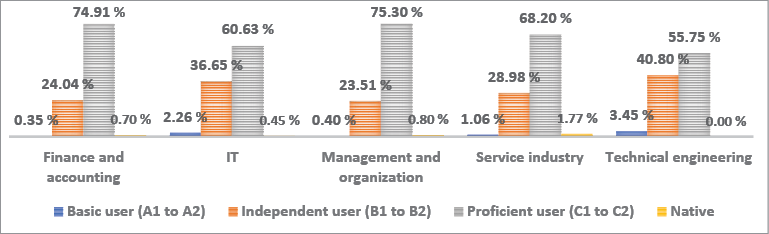

Figure 4. Distribution of % share of language proficiency levels across the industries disregarding the country

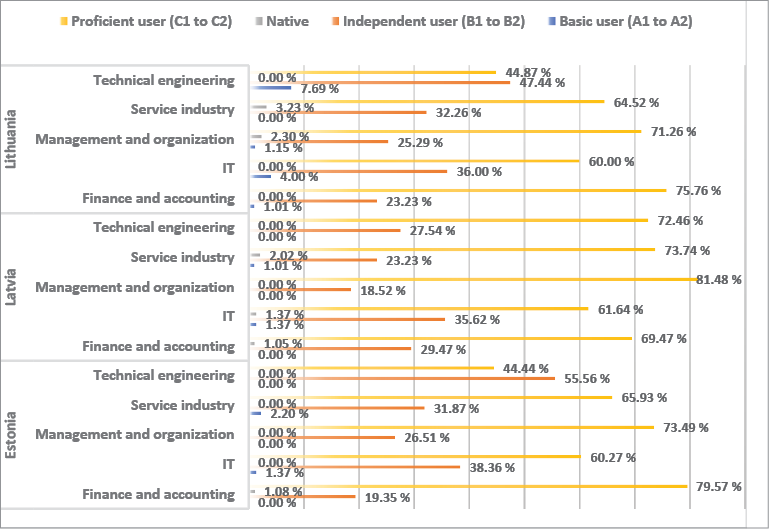

Examining industry-by-industry, it is observed that around 8 in 10 (74.91 % and 75.30 %) businesses in finance and accounting, and management and organization require a candidate to be advanced language user with C1 to C2 level across all countries, respectively. Around 7 in 10 (68.2 %) employers list a requirement for the employees in service industry and around 6 in 10 (60.63 %) recruiters demand C1 to C2 language level in IT and technical engineering (55.75 %) sectors.

Significantly lower share of job postings, with only 3 in 10 advertisements, listed a requirement for independent user (B1 to B2) (29.77 %) across all examined industries.

The highest share of employers demanding the employee to use language at independent level (B1 to B2) is registered in IT (36.65 %) and technical engineering (40.80 %) sectors. Around 3 in 10 recruiters demand the employee to know language at B1 to B2 level in finance and accounting (24.04 %), management and organization (23.51 %) and service industry (28.98 %).

A considerably low percentage of the employers demand the user to use language at Basic levels (1.32 %) and to be a ‘native speaker’ (0.82 %). The highest share of basic user in foreign language proficiency among other industries was recorded technicians (3.45 %) and IT (2.26 %) specialists across all countries.

A demand of being a ‘native’ language user is significantly low across all industries and countries, with only 1 in 10 employers. However, compared to other examined business sectors, a considerably high % of employers, listed a requirement to be a ‘native user’ in service industry sector (1.77 %), 0,8 % in management and organization and 0.7 % finance and accounting business sectors. The graph below demonstrates the distribution of language proficiency levels across the examined industries with regards to the country.

Figure 5. Overview of the distribution of language proficiency levels across the examined industries with regards to the country

The main conclusions for a demand of language proficiency level regarding the region:

1. The examined data reveals that the most desired employee is a speaker who possesses C1 to C2 language proficiency level according to CEFR across all industries.

2. A minor part of the job postings listed a requirement to be a ‘native’ speaker or to possess basic language proficiency level (A1 to A2) according to CEFR.

The following section overviews the demanded specified language skills across the investigated industries. Note that only job postings (N=1217), which listed the requirement for foreign language knowledge, participated in this stage of the study (see table 2). Most of the job postings (N=1217), which listed the requirement for language knowledge, specified the skills demanded for the vacancy (N=1158).

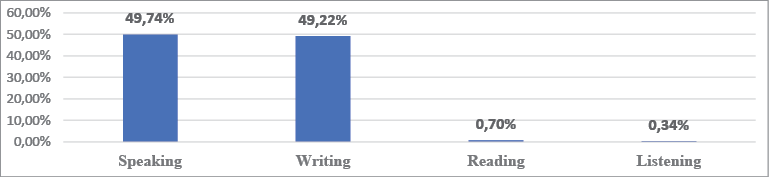

Writing and speaking skills were rated as the most important and prioritized skills over reading and listening skills across the examined business sectors in the Baltic. Nearly all job postings across all industries advertise the so-called soft skills, frequently using descriptions such as “high level of competence in verbal and written communication skills” or “excellent written and verbal communication skills”, “fluent English written skills”, “strength in written and verbal communication”, “good level of written and spoken English”, “highly proficient in spoken and written English” under preferred requirements.

Reading and listening skills were absent in almost all job postings across all examined industries and countries. Listening skills were rated as the most unimportant skill across the examined business sectors in all three countries.

All these numbers may be supporting the view that writing and speaking skills across all industries are highly valued because the examined industries belong to service support sector where spoken correspondence is generally important, while reading and listening qualification is more necessary for the employees working with documentation. The graph below reports % share of language skills in the job postings across the industries disregarding the industry and the country.

Figure 6. Overview of demanded language skills in the job postings across the industries disregarding the industry and the country

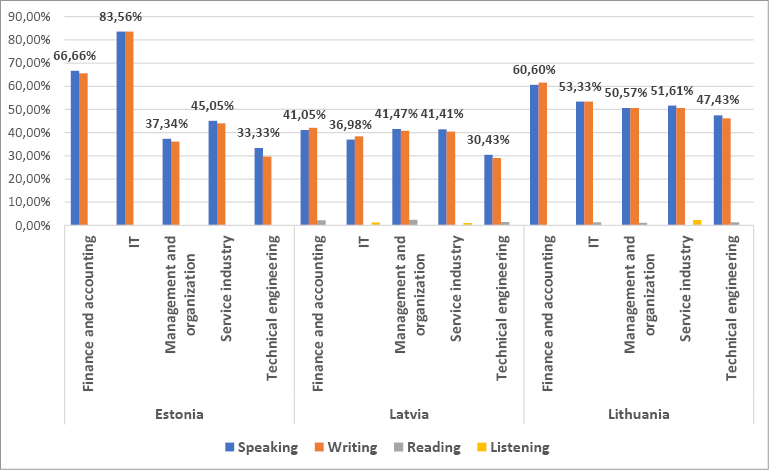

Around 4 in 10 businesses in Lithuania and 5 in 10 employers in Latvia and Estonia request a candidate to speak and write well across all investigated industries. The highest share of demanding speaking and writing skills is observed in IT business sector in Estonia with 83.56 % for speaking and 83.56 % for writing skills. It is two times higher than in Lithuania with 37% for speaking and writing 38.35 % skills and one and a half times higher than in Latvia with 53.33 % both for speaking and writing skills. The demonstrated figures may be linked to the fact that ICT is the fastest developing sector in Estonia, with 9 % of GDP growth (Invest in Estonia, n. d.).

Finance and accounting business sector is the second business sector after IT with relatively high figures for speaking and writing, with more than around 6 in 10 businesses in Estonia and Lithuania, with 66.66 % for speaking and 65.59 % for writing in Estonia and 60.60 % for speaking and 61.61 % writing in Lithuania and around 4 in 10 businesses with 41.05 % for speaking and 42.10 % for writing in Latvia.

The request for speaking and writing is considerably lower in technical engineering business sector across all countries. For example, compared to IT business sector it is three times lower, with 33.33 % for speaking and 29.62 % for writing in Estonia.

Reading and listening skills were absent in almost all job postings across all examined industries and countries. However, employers from the sectors such as finance (2.10 %), management and organization (3.54 %), technical engineering (4.82 %) and IT (1.30 %) indicated a demand for reading skill across Latvia and Lithuania. Estonia is the only one country from the Baltics that has no requirements for reading skills across all sectors. The demand for reading skill in the mentioned business sectors may be explained by the fact that documentation is vital in these business sectors. For example, the employees working in finance and accounting are involved with record keeping, technical engineers and IT professionals need to read the manuals and instructions. Listening skills were rated as the most unimportant skill across the examined business sectors in all three countries. Relatively low percentage of job advertisements in IT (1.30 %) and service industry (2.29 %) demanded a candidate to possess listening skill in Latvia and Lithuania, respectively. The graph below reports % share of language skills in the job postings across the industries regarding the country.

Figure 7. Overview of demanded language skills in the job postings across the industries disregarding the industry and the country

The main conclusions regarding the requested language skills:

1. Employers exclusively demand for speaking and writing skills while reading and listening skills hit the bottom. It could be explained that the examined business sectors belong to service industry where verbal and written communication is a value-add.

2. IT sector in Estonia demonstrates higher share of demanding speaking and writing skills compared to other Baltic countries. It could be explained that Estonia positions itself as the fastest developing IT country.

3. Correlating the results of Figure 4 with the data from Figure 5, it is observed that most of the recruiters search for a candidate who can speak and write at C1 to C2 language proficiency level.

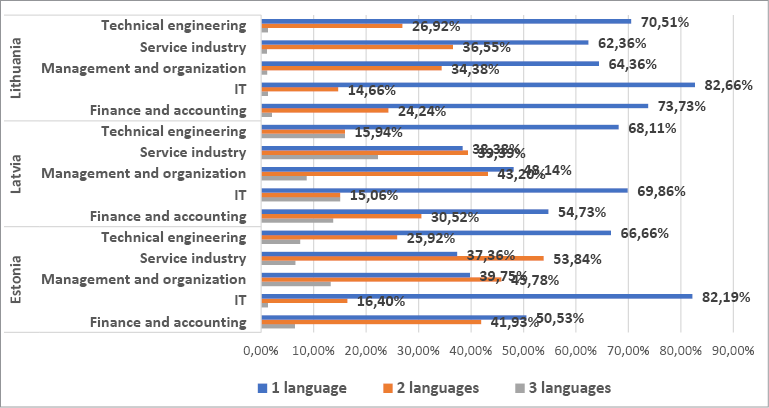

The following section overviews the demand for knowing more than one language across the examined industries in the Baltic region. The graph 8 presents data how many languages a candidate must know to obtain the desired job position. The data show that multilingualism is the characteristic among all investigated businesses. Around every single business demands an employee to know one foreign language (60.62 %), each third (30.98 %) two and each tenth (7.81 %) three foreign languages across all examined business sectors. Service industry and management and organization are the industries among other sectors, which listed more job postings with a demand to know two languages than one in Latvia and Estonia.

However, it is worth to note that IT and technical engineering business sectors are the sectors which list the highest share of job postings with no requirements for language knowledge (see table 2).

Figure 8. Overview of multilingualism in the examined business sectors

The main conclusions regarding the number of the required languages:

1. Around every single business demands an employee to know one foreign language (60.62 %), each third (30.98 %) two and each tenth (7.81 %) three foreign languages across all examined business sectors. Service industry and management and organization are the industries among other sectors, which listed more job postings with a demand to know two languages than one in Latvia and Estonia.

2. However, it is worth to note that IT and technical engineering business sectors are the sectors which demonstrate the highest share of job postings which do not list any requirements for language knowledge.

The chapter provides industry-by-industry data what languages an applicant must know to get the desired job position in the Baltic region. The collected data reveal that twenty-two different languages are in demand across the examined sectors.

One of the most important requirements for an employee across three Baltic countries and investigated business sectors is high English language proficiency. 10 in 10 (98.03 %) of employers listed a demand for English language skills. The proportions of English language knowledge demand are similar across all investigated sectors.

The second most required foreign language to know across all industries is Russian (6.91 %). The geographic location of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and the border with Russia, are the key factor for many global companies to launch business operations in the Baltic states where Russian language is a high-level necessity for the business. The highest demand for Russian language is observed in service industry (3.13 %) and management and organization (1.97 %) business sector across all investigated countries. However, correlation with Russia, according to Eurostat, is limited across all industries. This can be explained by the shift of the Baltic countries to a more EU oriented economy and by the relative size of the economies. (Poissonnier, 2017).

The Scandinavian languages take considerably high share (6.57 %) among the demanded languages across the examined business sectors of the Baltic and share the second place with Russian language. The most popular Nordic languages to require are Swedish (2.22 %), Norwegian (1.97 %), Finnish (1.48 %), Danish (0.90 %). The demand to possess Scandinavian language skills may be explained by the fact that business units from Scandinavian countries find similarities in cultural characteristics including the possibility to easily discuss business manners, closed and shared time zones, excellent language skills and even a willingness to learn Scandinavian languages. For example, in Latvia 44 % of business service centers originated in Scandinavian countries and links with Finland are relatively high, especially for Estonia (Poissonnier, 2017). The distribution share of Scandinavian languages is similar across all examined industry.

German language (1.73 %) is the third foreign language to be requested in the region with almost 2% of share. Dutch and French languages take relatively low share (0.66 %) among the demanded languages in the Baltic. Surprisingly, but demand for Polish language was requested only in 0.41 % of job advertisements across the investigated industries. It could be explained that trade links with Poland, a major market with a common border with Lithuania, are relatively weak.

Other languages, such as Spanish (0.58 %), Turkish (0.08 %), Japanese (0.08 %), Mandarin (0.08 %), Arabic (0.08 %), Ukrainian (0.16 %) are hardly requested in the region.

Trade among the Baltic area accounts for 10 to 30 % of each country’s exports and imports (Poissonnier, 2017). It signifies the importance of knowing local or one of the Baltic languages.

It is worth to note that a demand for local language knowledge is relatively high in each of the examined Baltic countries. It implies that foreign investors search for an employee who is able to communicate effectively not only in English but also in local language.

These findings have important policy implications with regards to the education and training offered in universities.

The main conclusions for the Baltic region regarding the diversity of demanded languages:

1. Employers in the Baltic countries require knowledge of languages. Foreign languages are demanded in every single the job advertisements published in the region.

2. In the Baltic region, English is the most demanded foreign language skill: it is mentioned in 98 % of the vacancies.

3. Russian and Scandinavian languages are the second most demanded foreign languages to know.

4. German is the third most requested language in the region. German language skills appear in around 2 % of the advertisements.

5. Other languages such as Turkish (0.08 %), Japanese (0.08 %), Mandarin (0.08 %), Arabic (0.08 %), Ukrainian (0.16 %) are hardly requested in the region and are only present in less than 1 % of the vacancies.

6. Local Baltic languages are often listed in parallel with other requested languages. The % share of demanded knowledge for local language is considerably high. 8.22 % of job postings demand a candidate to know Lithuanian language, 11.84 % Latvian and 7.32 % Estonian.

Discussion

The study indicates that the demand for foreign language skills is a must in the labour market of the Baltic States.

Answering the first hypothesis, which states that language skills have a crucial effect on employability, the results of the study showed that effective language skills are a must attribute in the workplace in all industries and countries studied. The data examined show that most recruiters are looking for a candidate who can speak and write fluently and spontaneously, without much searching for expressions. Moreover, employers exclusively demand for speaking and writing skills, while reading and listening comprehension skills are least in demand. This could be due to the fact that the industries studied belong to the service industry, where oral and written communication is a value-add attribute. The findings reported in a cross-national and cross-sectoral study by Cambridge English (2016) are consistent with the finding of the present study. The Cambridge English study found that speaking is the most important skill in service industries where social interaction is a large part of the job. Likewise, Beadle et al. (2016) put the Barcelona 2002 aim at the forefront of their study and report the benefits of foreign language skills in the labour market with the emphasis on the value of oral foreign language skills necessary to converse with native speakers in the workplace, especially with citizens from neighbouring countries working in the labour market, and that foreign language skills improve career opportunities as part of a broader set of skills and experiences (e.g. educational background, work experience).

Answering the second hypothesis, which assumed that a demand for language knowledge is in line with so-called hard skills, the results of the present study proved that a significant share (51.59 % ) of the recruiters considers language knowledge more important than so-called hard skills, listing the demand for language skills of primary priority compared to other qualifications and competencies listed in the job advertisement. Another considerably high share of job postings (48.39 %) demanded language skills in parallel with hard skills. Similar findings were made by Kurekova et al. (2012), who conducted an empirical study using the largest job portal in Slovakia and focused on the specific skills required by employers in the Slovak labour market. The study showed that language skills, in addition to other skills listed in the job advertisement, are in demand in a large proportion of occupations, both on the domestic and foreign markets. The study by Muler and Safir (2019) confirms the finding of the present study. It used data from the World Bank to estimate employer demand for cognitive, socio-emotional and technical skills of employees and examined online job advertisements on Ukrainian job websites. The study found that foreign language skills accounted for the same share as technical skills. The results of the present study are also in line with the findings found by Brancatelli et al. (2020), which provides an analysis of skills needs in different sectors and occupations. The study accurately measured the requirements for each skill in job postings.The most important finding of the study is that foreign language skills, extraversion and computer skills are most in demand and listed across all industries and occupations.

The analysis has identified the languages that are likely to be of greatest importance to the Baltic in the next 10-20 years. This analysis has identified ten languages: English, Scandinavian (Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, Danish), German, Russian, Dutch, French and Polish that have the potential to add the most value to the Baltic’s strategic interests. Moreover, multilingualism in the Baltic labour market is evident. The data show that multilingualism is the characteristic of all the job postings studied. About every single job advertisement requires its employees to speak one foreign language (60.62 %), every third (30.98 %) requires two foreign languages and every tenth (7.81 %) requires three foreign languages in all sectors examined. The study found that in the Baltic Sea Region English is the most demanded foreign language competence: it is mentioned in 98 % of the job advertisements. Russian and Scandinavian languages are the second most demanded foreign language skills. German is the third most requested language in the region. German language skills are mentioned in about 2 % of job advertisements. The study results suggest that despite English is de facto the first foreign language taught in the Baltics, only proficiency in more than one foreign language will make a decisive difference in the future. This calls for language policies and strategies to more establish plurilingual education necessary for mobility and employability. According to the study results, English language will remain the most demanding language in the world of business for the next decade in the Baltics. These results complement the findings of the Skills Module (Rutkowski et al., 2017) according to which nearly 40 percent of surveyed employers claimed that specialists’ insufficient knowledge of English or other foreign language hampered the firm’s performance. The results of the study predict that English is a dominant language and is likely to remain dominant in the future.

Furthermore, the results of the study show that the demand for local language skills is considerably high. The study findings report that local Baltic languages are often listed in parallel with other required languages. 8.22 % of job advertisements require applicants to know Lithuanian, 11.84 % Latvian and 7.32 % Estonian. The results of the present study imply on the relationship between knowing the language of the host country and employability opportunities. Similar findings were made by Dustmann and Fabbri (2003), which suggest a positive premium of local language on a lower probability of becoming unemployed. The study by Clark and Drinkwater (2009) found that knowledge of the host country’s language is an important factor in the labour market. Aldhasev et al. (2009) conclude that immigrants who are fluent in the host country language are less likely to become unemployed.

The overall results of the study suggest that language skills are an indispensable asset for the recruiters in the examined industries to be competitive in an increasingly globalised world.

Limitations of the study

This study is not without its limitations. The first possible limitation is that such factors as the size and legal type of the organization, offered job vacancy, complexity of occupation, location of an organization, etc. could influence the results of the study. However, the current study aimed to examine the meaning of language as such for employability in the following five categories: (1) how many job advertisements list language skills among the qualifications and skills required, (2) language ‘levels of priority’ among other qualifications and skills in the job posting, (3) required language proficiency level, (4) required language skills, (5) demand for multiple languages listed in the job advertisement. This study purposefully does not consider other elements of job offers in relation to language knowledge, such as requirements for certain occupational skills, or detailed job-related competences and does not relate language skills to wage premiums. This objective could be addressed to further study.

Conclusions

This study examined the effect of foreign language on employability. The cross-country and cross-industry dimensions were exploited to achieve the results, meaning that the same industry in different countries was compared in relation to the language dimension. The study embraced five categories to define the meaning of language for employability: (1) how many job advertisements list language skills among the qualifications and skills required, (2) language ‘levels of priority’ among other qualifications and skills in the job posting, (3) required language proficiency level, (4) required language skills, (5) demand for multiple languages listed in the job advertisement. However, this study does not consider other elements of job advertisements related to language skills, such as requirements for specific professional skills or detailed job-related competences.

After examining the demand for language competence among other qualifications listed in one thousand four hundred forty two (N=1442) job postings, the statistical analysis of the study concluded that language skills are considered a premium skill listed in job advertisements. The study found that a significant proportion of recruiters consider language skills to be the most important qualification among the other qualifications listed in job advertisements. This study also reported that employers require competent foreign language skills, especially written and spoken. Moreover, the study concluded that while English is de facto the first foreign language required in the Baltic market, proficiency in more than one foreign language is a crucial factor in employability. Subsequently, the study found that multilingualism is evident in the Baltic labour market. Languages such as German, Polish, Scandinavian and Dutch are in high demand in the Baltic countries. Furthermore, the study found that there is a new trend to effectively master the national language. However, due to a significant lack of research made regarding the relationship between language and economics in the Baltic states, the research regarding the language knowledge of the host language of the country and employability status could be addressed for further research.