Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach eISSN 2424-3876

2025, vol. 15, pp. 106–125 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/SW.2025.15.6

Inside Every Problem Lies an Opportunity: Senior Caregiver Perspectives

Zuzana Truhlářová

University of Hradec Králové, Czechia

E-mail: zuzana.truhlarova@uhk.cz

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3471-8657

https://ror.org/05k238v14

Stanislav Michek

University of Hradec Králové, Czechia

E-mail: stanislav.michek@uhk.cz

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0706-7043

https://ror.org/05k238v14

Jiří Haviger

University of Hradec Králové, Czechia

E-mail: jiri.haviger@uhk.cz

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8353-497X

https://ror.org/05k238v14

Melanie Zajacová

Charles University, Czechia

E-mail: melanie.zajacova@ff.cuni.cz

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5261-4889

https://ror.org/024d6js02

Jana Marie Havigerová

University of Hradec Králové, Czechia

E-mail: jana.havigerova@uhk.cz

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2614-4200

https://ror.org/05k238v14

Abstract: This study examined the impact of the recent pandemic on 253 Czech social workers in senior residential care, focusing on their emotional states and problem-solving experiences. By using PHQ-9 and GAD-7, the research found that 35% of the respondents reported moderate to severe depression, and 27% admitted similar anxiety levels. Contrary to expectations, private context variables showed no significant correlation with these emotional states. However, corpus analysis identified distinct verbal expressions: loneliness, financial deterioration, and chaos in higher depression groups, and information management challenges in higher anxiety groups. The most frequent problems addressed were behavioral issues, motivation, and communication. A measurable connection existed between problem characteristics and emotional states, with higher depression linked to economic problems and strained non-work relationships, and higher anxiety associated with information management difficulties. Social workers adapted by increasing their IT use, reducing administrative tasks, and enhancing client communication. These outcomes highlight their resilience and capacity to manage stress positively during challenging times. Their crucial role in ensuring the dignified lives of seniors, combined with their adaptability and commitment, offers a promising outlook for their mental health and well-being when facing future challenges.

Keywords: social workers, older adult care, depression, anxiety, problems solved.

Recieved: 2024-07-08. Accepted: 2025-05-02

Copyright © 2025 Zuzana Truhlářová, Stanislav Michek, Jiří Haviger, Melanie Zajacová, Jana Marie Havigerová. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access journal distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

In the existing framework of social protection, the elderly and individuals with health impairments emerge as notably vulnerable groups, who are reliant on health and social care services for their wellbeing. The absence or limitation of such care can critically degrade their quality of life, sometimes posing a risk to their survival. This underscores the importance of focusing on caregivers who support these individuals both at home and in institutional environments. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted the daily life and social interactions, adversely affecting the mental health and wellbeing of many (Tsai, 2022). The pandemic elicited a response from social work professionals to address the resultant human suffering (Guastafierro et al., 2021; Weinberg, 2021). Prior to the pandemic, Siebert (2004) identified a high prevalence of depressive symptoms among social workers.

This research zeroes in on social workers within senior residential services in the Czech Republic, where social services are legally mandated to meet specific operational standards. As crucial instruments of social policy, the year 2021 saw the registration of 916 residential facilities catering to the elderly, encompassing 526 homes for about 35.8 thousand seniors and 376 specialized facilities serving around 23 thousand older-age individuals. By the end of 2021, nearly 55,000 seniors, or 2.7% of those aged 62 and above, resided in these services, with a higher representation noted among the older age groups (ČSU, 2022). The impact of COVID-19 was significant, with 3,418 (11.2%) of the 30,363 reported casualties by August 6, 2021, being residents of such services. Between October 1, 2020, and April 11, 2021, 760 COVID clusters and 28,387 infections were documented in these settings (Horecký and Švehlová, 2021). Social workers in elderly care facilities tailor services to each client, based on information from clients and their families, ensuring continuous monitoring and protection of their clients’ dignity (Zajacová, 2021). These services aim to keep older adults physically and psychologically independent, integrating them into social life to maintain their normal lifestyle as long as possible, thereby ensuring a dignified living environment (Amadasun, 2020; IFSW, 2014). During the COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions were being placed on the movement and social interactions of clients in residential services, highlighting challenges such as protecting the staff, a shortage of social workers for adequate care, and the disruption of the clients’ familial and social connections (Gabura, 2022; Fitzpatrick, 2021; Truhlářová et al., 2021). Social workers had to adapt by finding creative – and sometimes imperfect – solutions to meet the evolving needs of their clients who were experiencing increased anxiety, fear, and aggression due to isolation and misinformation (Bern-Klug et al., 2021; Banks, 2023; Johansson-Pahala et al., 2022; Okafor, 2021). They played a vital role in providing support, understanding, and accurate information during this crisis. Research in the Czech Republic specifically focused on the challenges faced by social workers in elderly residential services during the pandemic.

Research and studies highlight that the perception of problems varies among different observers (Denzin, 2017; Leary et al., 2007; Michailakis and Schirmer, 2014). Social systems create their own realities and define social issues uniquely (Healy, 2022; Michailakis and Schirmer, 2014; Punová, 2021). This study posits that, during the pandemic, social workers viewed problems through a distinct lens, offering new insights into the challenges faced by social workers caring for older adults in this period. Based on the results of systematic review by Saade et al. (2022), it was highlighted that work factors associated with depression in the helping-segment professions includes skill utilization, decision authority, psychological demands, physical demands, the number of hours worked, the work schedule (irregular or regular), the shift hours schedule (daytime versus night time), social support from coworkers, social support from supervisor and the family, job insecurity, recognition, job promotion, and bullying. Based on the findings by Greene et al. (2021), their study of frontline health and social care workers in the UK during the initial wave of the COVID pandemic revealed that a significant proportion met the criteria for depression, and that factors such as inability to confide in managers about their coping difficulties and lack of reliable access to personal protective equipment were associated with a higher likelihood of meeting the criteria for a clinically significant mental disorder.

Therefore, we are interested in finding the connections and whether the social workers caring for the older adults have learned any ‘lessons’ from their lived experience of solving problems during the pandemic, what the respondents intend to do differently, or what they plan to change based on this.

Objective of the study

This is an exploratory quantitative study. The question in this research is as follows: What are the characteristics of the solved problem situations, negative emotional states, and how are professional and personal circumstances related to each other?

Sub-research questions:

• What is the prevalence of negative emotional states (depression and anxiety) among social workers in residential services for the older adults?

- Which variables in the private and work contexts connect with negative emotional states?

- What verbal expressions used to describe situations distinguish people with different emotional states (increased levels of depression and anxiety)?

• What characteristics reveal the problems that social workers in residential services for the older adults were solving during the pandemic?

- Which variables from the private and work contexts and which characteristics of the solved problems show a measurable connection? (Age, length of experience, educational attainment, experience with COVID-19).

• Which characteristics of the problems solved by social workers in residential services for the older adults show a measurable connection with negative emotional states?

• Based on the experience, what would social workers like to do differently?

Note: We use the term ‘senior caregivers’ in the sense of social workers involved in residential social services and caring for seniors aged 65+.

Method

This was a cross-sectional study of social workers in residential services for the older adults in the Czech Republic. The Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (CASI) was chosen as a research tool: an online questionnaire survey was employed.

Research tools

The study aimed to assess the pandemic’s effects on social workers, by focusing on mental health risks, operationalized as anxiety and depression levels. The assessment tool comprised 34 questions across four domains.

Demographic data (9 items) were collected in two categories: personal socio-demographics (age, gender, educational background, work experience, education level, and municipality size) and professional details (workplace, client type, COVID-19 exposure, and client mortality).

Work situation evaluations (9 items): specific work situations addressed by social workers in connection with the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic were investigated. The instruction began uniformly: “Now let’s slow down. Try to visualize specific situations that you had to deal with as a social worker in relation to the pandemic, situations that were new and different for you than before.” Situation 1: ‘the first thing’, 2. ‘the most challenging’, 3. ‘the most valuable’ were then introduced with identical open-ended questions: “which I dealt with during the pandemic was”: “describe as specifically as possible what it was about, what was the core of the situation”; “how did you address the situation and why?” Each situation was followed by a simple scale: the outcome of the approach was ‘successful’ – ‘cannot assess’ – ‘unsuccessful’. Note: The calculations revealed that these supplementary scales did not differentiate the sample and were excluded from further calculations; they are only mentioned here for completeness. The focus was on the respondent’s attention to various situational parameters (categories and subcategories describing the work situations addressed in general terms). Categorical analysis of the responses and the resulting categories are described below in the Data processing procedure section.

The GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder, 7 items) scale, validated by Spitzer et al. (2006) and Zhou et al. (2020), is used to identify and assess the severity of anxiety disorders. It utilizes a four-point Likert scale for symptoms such as excessive worry and nervousness, with scores ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The GAD-7 scores span from 0 to 21, with levels 0–4 meaning none-to-minimal, 5–9 showing mild, 10–14 denoting moderate, and 15–21 standing for severe anxiety levels. Scores above 10 suggest a necessity for treatment.

Depression was evaluated by using the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire, 9 items), which scores between 0 and 27 based on nine items each for one criterion of the depression state. The PHQ-9 thresholds at 5, 10, 15, and 20 indicate an increasing severity of depression from minimal to severe, with scores above 15 suggesting a need for clinical intervention (a diagnosis of major depression requires at least five depressive symptoms for most days over the past two weeks, including depressed mood or anhedonia; Kroenke et al., 2001).

Data collection procedure

The research plan was approved by the UHK Ethics Committee on 23 April 2021 under registration number 7/2021; the protocol was signed by the chairperson of the committee, Prof. PhDr. Marek Franěk, CSc., Ph.D.

Questionnaires were distributed to all 916 registered residential social services for older adults via the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications of the Czech Republic. These services employed 1,706 social workers, who were invited to participate through a letter containing a link to an online questionnaire hosted on LimeSurvey, available from November 2020 to July 2021, that is between the waves of the pandemic, after the partial easing of restrictive measures, before the second wave of restrictions came. The survey, taking an average of 25 minutes to complete, was voluntary, and it utilized a self-selecting sampling method, ensuring respondent anonymity.

Sample

The data set consisted of answers from N=253 social workers (14.8% of the basic group) working in residential services for the older adults (age=43±10 years), 90% of the participants were women, all levels of experience (m=11±8 years), all levels of education (predominantly university students), and cities and towns of different sizes (approximately one-fifth represented cities over 100,000 inhabitants) (Table 1). The COVID-19 context was as follows: during data collection, half of the sample had contracted the COVID infection, one third was unsure, and 22% did not have it. Approximately 90% had completed a course on the topic during the COVID period; 75% had worked with COVID-positive patients, and two-thirds of these patients died due to COVID-19 (1/3 was directly involved in the death, whereas 1/3 learned about the fact of death indirectly).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic data: private context (N=253)

|

Item |

N |

% |

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

26 |

10.28 |

|

Female |

227 |

89.72 |

|

Age |

|

|

|

less than 30 |

38 |

15.02 |

|

31–40 |

63 |

24.90 |

|

41–50 |

89 |

35.18 |

|

51–60 |

55 |

21.74 |

|

>60 |

8 |

3.16 |

|

Practice years |

|

|

|

0–2 |

35 |

13.83 |

|

3–5 |

41 |

16,21 |

|

6–10 |

64 |

25,30 |

|

11–20 |

82 |

32,41 |

|

>20 |

31 |

12.25 |

|

Education |

|

|

|

Higher professional school |

45 |

17.79 |

|

University Bc. |

85 |

33.60 |

|

University Mgr. or Ing. |

108 |

42.69 |

|

Postgraduate (Ph.D.) |

15 |

5.93 |

|

Municipality size |

|

|

|

<200 |

7 |

2.77 |

|

200–499 |

15 |

5.93 |

|

500–999 |

18 |

7.11 |

|

1,000–4,999 |

45 |

17.79 |

|

5,000–19,999 |

59 |

23.32 |

|

20,000–49,999 |

37 |

14.62 |

|

50,000–99,999 |

18 |

7.11 |

|

> 100,000 |

54 |

21.34 |

Data processing procedure

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) were assessed as per their manuals.

Work situation evaluations involved open coding and categorization, with individual assessments and coding by collaborators, specialized review for uncertainties, and a final expert verification post a two-week interval, achieving satisfactory consensus. The categorical analysis was conducted according to the procedure outlined by Bilder and Tebbs (2008).

Resulting categories:

1. The core of the problem – what the problem is about, what was emphasized: subthemes emotions, and feelings (e.g., fear); motivation (e.g., unclear goal, lack of energy to achieve the goal); competence (e.g., I can’t work online); behavioral (e.g., wearing a face mask); communication (e.g., communicating information about new measures); related to the body (e.g., tiredness); related to time (e.g., lack of time to ensure changes, changing the daily schedule in the home office); technology and ICT (e.g., insufficient wi-fi coverage); material outside of ICT (e.g., there is no available room, vehicle); geographical (e.g., a ban on crossing the district), economic (e.g., there was no line in the budget allowing the purchase of masks), rules of polite behavior (e.g., shaking hands).

2. The bearer of the problem: the social worker, relatives of the worker, the client, relatives of the client, other people in the organization.

3. Professional perspective: preparation (resources of preparation, time devoted to preparation), conditions (spatial, technical), content (what will the task be), methods and forms (how I will implement), social relationships within the scope of the profession (relationship with clients, parents, colleagues, supervisors), relationships outside of the work context (relationships within the family, community, etc.), and personal circumstances (nature, health, mood, competence, motives, values, etc.).

An aggregate variable is created by using the total score method for subcategories (0–5 range), reflecting respondent focus on situational characteristics based on the described situations.

Text analysis: Our study incorporated a corpus-based analysis to examine terminology related to the issue, contrasting word frequencies across four General Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) categories: minimal, mild, moderate, and severe. By utilizing the K-words tool with the log-likelihood approach (assessing similarity to the foundational Czech corpus), we identified words fulfilling specific criteria: a significance level (α) of <0.001, a minimum frequency of 3, and constituting 5% of the keywords. We excluded terms strictly associated with COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., ‘pandemic’, ‘quarantine’) and focused on those conveying emotions.

Methods of data analysis consisted of the verification of normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, SD, median), non-parametric t-test (Wilcoxon, Kruskal-Wallis), and correlation (Rank-Biserial, Spearman). The eta square was calculated and converted by using a calculator (Lenhard 2016) to Cohen’s D, odds ratio, and CLES. Specific statements were found to impact the topics the respondents dealt with.

Results

What is the prevalence of negative emotional states (depression, anxiety) in the population of senior caregivers?

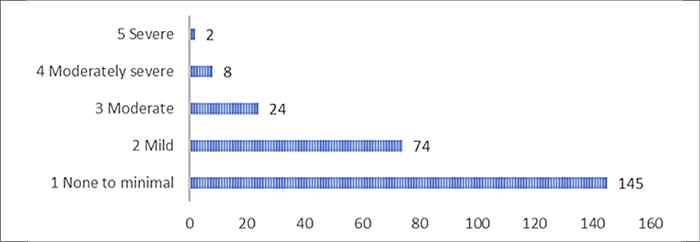

The study revealed PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores indicating low mean values of 3.9, with the majority of the participants not reaching maximum scores, which suggests a predominance of no symptoms or mild symptoms of depression and anxiety among the caregivers. Specifically, PHQ-9 results highlighted that 50% of the participants were not at risk of depression, 35% exhibited mild depression, and 15% displayed significant depressive symptoms warranting a medical consultation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Frequencies: categories of depression PHQ -9 (N=253)

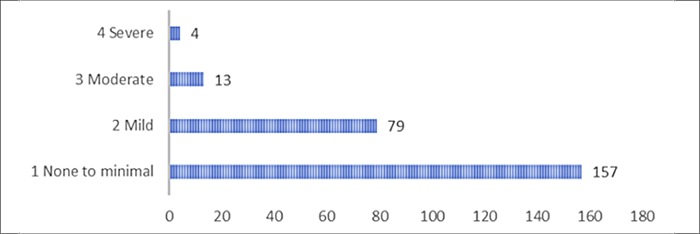

Similarly, GAD-7 findings showed that 66% had mild anxiety symptoms, 28% were experiencing moderate, and 6% severe anxiety symptoms, necessitating professional advice/assistance (Figure 2).

The distributions were non-normal, as confirmed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (sig <0.001) for both conditions. Overall, the data suggest that two-thirds of the sample experienced zero or mild symptoms, 20–25% were having moderate symptoms, and a minority of 6–10% were suffering from severe symptoms, indicating a prevalence of mental health concerns of 6% for depression and 10% for anxiety disorders.

Which variables from the private and work context show a connection with negative emotional states?

Figure 2.

Frequencies: categories of anxiety GAD-7 (N=253)

Has the degree of association between the private context of social workers (age, length of experience, education, experience with COVID-19, size of the municipality) and their depression/anxiety been verified? The characteristics of the private context did not show a statistically significant relationship with depression (PHQ-9) or anxiety (GAD-7).

What verbal expressions to describe situations distinguish people with different levels of emotional states (increased levels of depression, anxiety)?

Verbal expressions used to distinguish people with different levels of emotional states (increased levels of depression and anxiety) were investigated by using a corpus-based analysis. The bag of words was compared according to the three GAD-7 and PHQ-9 levels (minimal-mild, moderate, and severe). Table 2 shows the level of the emotional state in the rows and the expressions most commonly used by the respondents with a given level of GAD-7 and PHQ-9 in the columns. Emotional expressions that caught our attention are also highlighted.

Table 2.

Words from the description of the situation: K-words frequency analysis (N=253)

|

Level of GAD-7 |

Level of PHQ-9 |

||

|

1 None to Mild |

Solved, shifts, cohesion, loved, reassure, deterioration, strengthening, privacy, cheerful |

1 None to Mild |

Humor, incapacity, loose, challenging, barbecue, cohesion, termination, loved, strangers, cooperation, cheerful |

|

2 Moderate |

Outings, baked, solved, limiting, asylum, deceased, loved, relaxation, cooperation, deaths, panic, compliance |

2 Moderate |

Loneliness, sheltered, limiting, chaotic, relaxation, loved, deterioration, uncertainty, cheerful, chaos, challenging |

|

3 Moderately Severe to Severe |

Belonging, solved, loved, joy, crisis, emergency, funeral, mood, anxiety, fear, confusion |

3 Severe |

Sleeves, funeral, dying, Loved, deaths, joy, anywhere, helping, lack, everyone, emergency |

What characteristics show the problems that senior caregivers dealt with during the pandemic?

We present the characteristics of the problems that the respondents solved as a list, from the most to the least frequent. Table 3 shows that, at the core of the problem situations, social workers caring for the older adults were dealing with behavioral problems, problematic motivation, communication, competence, and emotions. In contrast, the respondents were least involved in addressing economic, ethical, or material issues at the core of the problem. The core person of the problem was most often the respondent, their client, or co-workers, while others were less frequently mentioned: the descendants of the respondent, the founder, or the superior. From a professional perspective (the professional core), the problems were based on conflicts such as professional relationships, personality, content, or working conditions and the least on non-work relationships, work versus family conflicts, or preparation.

Table 3.

Characteristics of described problems: percentage (N=253 respondents, Ns=1012 described situations)

|

Rank |

Core of |

% |

Core |

% |

Professional |

% |

|

1. |

Behavior |

88.9 |

Respondent |

60.5 |

Professional relationships |

69.6 |

|

2. |

Motivation |

70.8 |

Client |

57.3 |

Personality |

54.9 |

|

3. |

Communication |

64.4 |

Co-worker |

56.1 |

Content |

53.0 |

|

4. |

Competence |

62.1 |

Relatives of the client |

26.5 |

Conditions |

50.6 |

|

5. |

Emotion |

54.2 |

State |

13.4 |

Methods |

29.2 |

|

6. |

Health |

45.5 |

Media |

12.6 |

Information |

18.2 |

|

7. |

ICT |

31.6 |

The respondent’s family |

7.9 |

Relationships outside of work |

16.2 |

|

8. |

Time |

27.7 |

Social environment |

5.9 |

Preparation |

13.4 |

|

9. |

Economy |

18.2 |

Descendants of the respondent |

4.7 |

Work vs. family |

7.1 |

|

10. |

Ethics |

11.5 |

Founder |

1.2 |

||

|

11. |

Material |

3.2 |

Superiors |

1.2 |

|

|

Which variables from the private and work context and which characteristics of the solved problems show a measurable connection?

No private characteristic (age, length of practice, educational attainment, experience of COVID-19, size of the municipality) showed a statistically significant relationship with depression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) among social workers working in residential facilities.

Which characteristics of the solved problems show a measurable connection with negative emotional states?

The relationship between the solved problems and emotional states (depression and anxiety) was tested by calculating Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Regarding the solved situations, four were significantly associated with depression and the anxiety level. The correlations were low to moderate in strength. Table 4 shows that people with higher levels of depression more often described situations involving economic factors and finances (e.g., how they had to get finance or supplies for protective equipment, solve the problems of clients with financial need – collect a pension, secure an asylum) and non-work relationships (e.g., fear regarding their family and loved ones, e.g., that they would not get sick, limited contacts due to isolation, and missing their family and loved ones).

Table 4.

Characteristics of the described problems in association with negative emotional states (N=253 respondents)

|

Characteristics of the problem |

Associated with |

rho |

sig |

|

The heart of the problem of economics |

PHQ-9 |

0.169 |

0.008 |

|

Professional core relationships outside of work |

PHQ-9 |

0.142 |

0.025 |

|

Professional core, professional relationships |

GAD-7 |

-0.125 |

0.049 |

|

Professional information core |

GAD-7 |

0.161 |

0.011 |

People with higher anxiety levels more often described situations as the core of working with information (e.g., lack of information about their loved ones, difficulty obtaining information for clients, chaotic and/or rapidly changing information from higher authorities, and the need to interpret and explain information about events to clients, even if they lack information and new information flows). In contrast, the lower was the respondents’ anxiety, the more often they described situations in which professional relationships were at the core (e.g., relationships with clients and the need to help them beyond the scope of the previously ‘normal’ work duties and normal working hours, more frequent and unexpected deaths of clients, the ability of the team to bond and function under stricter conditions, the client’s ability to cooperate, creating a good positive atmosphere in the workplace, sharing small funny incidents with their clients).

Based on their experience, what would social workers do differently in the future?

In this study, we examined the ‘lessons learned’ from the pandemic, focusing on the lived experiences of respondents in problem-solving, their varied responses, and the future changes they plan to implement. The participants expressed a desire to modify their work methods, job content, and social interactions within their professions. Only a minority believed that professional preparation changes (e.g., additional courses or intensified training) were necessary, with other aspects and non-professional relationships not being mentioned.

Table 5.

Commitment to change concerning emotions and emotional states: Comparison of groups test (N=253)

|

Area of change |

Variable |

Mann-Whitney sig. |

Cohen d |

CLES |

Odds Ratio |

|

Personal circumstances (character, mood, health, motives, competencies, values) |

PHQ-9 GAD-7 |

0.009 0.035 |

0.310 0.231 |

58.59% 56.45% |

1.74 1.52 |

Our analysis also explored the association between these intended changes and emotional states, as detailed in Table 5. We found that social workers planning to alter their approach to personal circumstances reported significantly higher levels of depression (1.74 times) and anxiety (1.52 times) compared to their counterparts. For instance, higher depression was linked to statements like prioritizing self-care and health prevention, seeking supervision and rest, and separating work from personal life.

Furthermore, our findings indicated that workplace factors such as client death or undertaking professional courses during the pandemic did not markedly affect the depression or anxiety levels.

Discussion

We analyzed the connections between emotional states and situations dealt with during the covid pandemic of social workers caring for the older adults and their private and professional contexts. Two hundred and fifty-three social workers participated in the research, of whom, 90% were women. The gender distribution corresponds to the usual gender representation in social and health professions in the Czech Republic and worldwide (Boniol et al., 2019; Schilling et al., 2008).

Emotional states

Emotional well-being was evaluated by using the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 questionnaires to measure depression and anxiety, respectively (Kroenke et al., 2001; Spitzer et al., 2006). The findings indicated that a majority of the participants exhibited none or mild symptoms of these disorders, with 20–25% experiencing moderate symptoms, and a small fraction (7–10%) facing severe symptoms, posing a significant mental health risk. The predominant emotional disorders identified were moderate-to-severe depression (35; 10%) and anxiety (27; 7%), aligning with the pre-pandemic findings by Siebert (2004) on social workers. Our data parallels that of recent studies among social workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Benatov et al., 2022; Greene et al., 2021), highlighting a significant prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders. The observed regional discrepancies in disorder prevalence may stem from our focus on social workers in elder care residential services, contrasting with studies without such specificity, challenging the findings of DiFilippo et al. (2022) regarding secondary care workers’ risk levels. Further, variables like gender, clinical experience, and age over 40 were linked to depression and anxiety levels (Alnazly et al., 2021; Zhan et al., 2022), although no direct correlation with depression was established for age, experience length, education, or the municipality size. Saade et al. (2021) suggested that work-related factors, rather than personal characteristics, significantly influence the depression levels among helping professionals, with overidentification potentially exacerbating depressive symptoms through diminished coherence (Ying, 2009).

Situations solved during COVID-19 period

During the pandemic, social workers were at the forefront of addressing human suffering, navigating various challenging situations (Weinberg, 2021; Banks et al., 2020; Fields et al., 2021). Despite the breadth of their experiences, a comprehensive typology of these situations still has to be identified. Our study utilized content analysis to categorize specific problem situations and solutions described by our respondents in the context of the pandemic. The findings underscore the predominance of participant behavior, followed by motivation, communication, competence, and emotions, as central issues, with ethical, material, or geographical factors being less addressed. This pattern suggests a pandemic-induced shift in focus towards external behaviors, potentially due to stress-related cognitive redirection and a decrease in the ability to analyze complex motivations (Mikšík, 2003; Braunstein-Bercovitz, 2003; Ackerman, 2011; Guastello, 2015; Kofta et al., 2011). Many social workers preferred focusing on external behaviors, reflecting a foundational aspect of social work – deep understanding of, and dedication to clients (Ferguson, 2018; Gambrill, 2017; Specht and Vickery, 2021).

Key stakeholders in these situations were often the social workers themselves, their clients, or colleagues, which underscores the importance of self-reflection and correct practice improvement (Sajid et al., 2021; Sicora, 2017; Van Zyl and Rothmann, 2022). Problems frequently revolved around professional relationships, personal attributes, work content, and working conditions, with minimal emphasis on work-family conflicts. This is notable given the pre-pandemic prevalence of work-family conflicts (Edlund, 2007) and their expected increase during the pandemic due to altered living conditions (Schiff et al., 2021; McFadden et al., 2021). However, our findings suggest that while the work-family conflict was significant, it was not the primary focus of the described situations, which were more oriented towards direct professional practice concerns.

The rapid transition to remote work and the adoption of digital communication tools during the pandemic significantly transformed social workers’ interactions with clients and colleagues, thereby affecting the dynamics of problem-solving and professional relationships (Nordesjö and Scaramuzzino, 2023). Concurrently, government policies and resource allocation decisions may have redirected the focus of social work practice, prioritizing immediate behavioral and communication strategies over long-term ethical considerations (Banks et al., 2020). Additionally, the cultural context along with the prevailing social norms during this period likely influenced the priorities and methods employed by social workers, placing greater emphasis on practical and observable outcomes rather than on abstract ethical deliberations (Tsui et al., 2023).

Connections between characteristics of solved problems and emotional states

This study explored the correlation between problem characteristics and emotional states, specifically, depression and anxiety, among social workers. Individuals with higher depression scores frequently cited economic challenges and strained non-work relationships, including fears of family illness and isolation. Common descriptors among these respondents included loneliness, financial deterioration, and chaos. Financial difficulties were linked to depression due to the stress and insecurity they engender, affecting psychological well-being (Butterworth et al., 2012; Saade et al., 2021). The diversion of resources towards immediate needs like disinfection and masks, away from client care, led to feelings of resignation and failure, which is indicative of depressive states (Greene et al., 2021; Siebert, 2004). Similarly, negative emotions tied to non-work relationships, such as fear and longing due to isolation, were identified as precursors to depression, with a noted increase in feelings of stigma and mental disorder risks among those lacking protective equipment (Greene et al., 2021).

Conversely, higher anxiety scores were associated with challenges in information management, including the rapid change and interpretation of covid information, which Ganggi (2020) identified as anxiety triggers. Lower anxiety levels correlated with stronger professional relationships and a focus on client care, suggesting that positive workplace dynamics and client interactions may mitigate anxiety.

Both depression and anxiety were linked to expressions of distress and mortality, with anxious individuals more often mentioning death-related terms (Martínez-López et al., 2021). Positive expressions, indicating a healthier mental state, were more common among those with minimal depression or anxiety, thus supporting the notion that positive thinking can protect against these conditions (Becker et al., 2019; Silton et al., 2020; Zandvakili et al., 2014). This study underscores the complex interplay between work-related stressors, emotional states, and the importance of positive workplace and client relationships in social work.

In addition, access to continuous training and mental health resources could enhance coping mechanisms, thereby reducing the impact of work-related stressors on emotional well-being (Mickel, 2019). Furthermore, the role of leadership in fostering a supportive work environment is highlighted, as effective leadership can promote resilience and job satisfaction, reducing the prevalence of stress-induced emotional states (Milojević, 2024). The integration of technology in social work practices, while initially challenging, offers long-term benefits in terms of flexibility and efficiency, potentially alleviating stress and improving service delivery (Afrouz and Lucas, 2023).

What would I do differently in the future?

We wanted to focus on positive phenomena, and therefore we asked the respondents about their learnings from the experience and what they wanted to do differently. The social workers caring for the older adults took away some ‘lessons’. Based on their lived experience in solving problems during the pandemic, what do the respondents intend to do differently, and what do they intend to change? The results showed that the workers were determined to change the methods and forms of work, the content of the professional performance, and social relations within the profession. At a minimum, the respondents answered regarding changes in preparation for the profession (taking courses, increasing the intensity of preparation), the conditions of the profession (which did not have much influence), and non-work relationships.

Further analysis showed how planned changes in the future were related to emotional settings. In our group, individuals with increased depression and anxiety more often plan changes in personal circumstances; for example, they want to work on their behavior characteristics (being more consistent), mood (optimism, positive attitude, calmness), and general personal abilities (resilience, adaptability, communication, and sense of humor); they plan to take more care of their health (prevention, sleep regime, general regime, transition rituals, relaxation, exercise), and adjust their ranking of values. The fact that social workers with a higher level of depression want to work on themselves may be explained, in part, by a more adaptive self-regulatory style (Eddington et al., 2016). It is great to be a social worker who cares for the older adults.

Limitations of study

This study is subject to several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, sampling bias may have impacted the generalizability of the results, as the sample – comprising approximately 15% of social workers caring for older adults in residential settings – was based on self-selection and may have failed to accurately reflect the broader population. Second, the study’s conceptual focus and instrumentation introduced some limitations. Emotional states were assessed exclusively through standardized tools (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) that are intended to measure negative symptoms, such as depression and anxiety, thereby neglecting positive emotional dimensions such as resilience, job satisfaction, and emotional growth. Third, the cross-sectional design provided only a single snapshot of the participants’ emotional well-being, thereby limiting insights into how these states may have evolved over time or in response to changing conditions. Additionally, the predominance of the respondents reporting no or only mild symptoms restricted the variability within the dataset, potentially reducing the sensitivity of the conducted statistical analyses. Finally, the correlational and predictive analytic approach precludes conclusions about causal relationships between emotional states and work-related factors.

Conclusion

The findings underscore the critical rates of depression among social workers, emphasizing the need for heightened attention to their mental health. Investing in mental health initiatives can enhance productivity and minimize absenteeism, offering substantial benefits to employers (Bern-Klug et al., 2021; Saade et al., 2021). The protective effects of caring for older adults against emotional disorders in social workers prompt further inquiry. Interaction with seniors who possess diverse experiences fosters meaningful connections and reinforces social work values through practice. Prolonged engagement with clients strengthens a sense of belonging, with caregiving allowing for empathy, altruism, and mutual appreciation, which, in turn, positively impacts the caregivers’ mental health and personal growth (Benatov, 2022). Despite challenges, the sector offers opportunities for personal development, resilience building, and coping with adversity, which were particularly evident during the crisis period at the time of the pandemic. The role of social workers in residential services is crucial for the well-being of older adults, highlighting the importance of psychosocial support and the need for strategies to support these professionals in their essential duties (Shi et al., 2022; Schug et al., 2021). The collective efforts of social workers and the healthcare community are key to upholding the dignity and happiness of older adults in care settings.

Acknowledgment

We sincerely thank the participants who generously devoted their time and insights to this research. Their willingness to share their experiences and perspectives was invaluable in shaping the outcomes of this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data are published with a DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.24279409.

Funding

This work was supported by the Faculty of Education, University of Hradec Králové with no specific grant.

Ethical approval

On April 23, 2021, the UHK Ethics Committee approved the plan under registration number 7/2021, and Prof. Dr. Marek Franěk, CSc., Ph.D., the committee chairperson, signed it.

References

Ackerman, P. L. (2011). Cognitive fatigue: Multidisciplinary perspectives on current research and future applications. American Psychological Association.

Afrouz, R., & Lucas, J. (2023). A systematic review of technology-mediated social work practice: Benefits, uncertainties, and future directions. Journal of Social Work, 23(5), 953-974.https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173231165926

Alnazly, E., Khraisat, O. M., Al-Bashaireh, A. M., & Bryant, C. L. (2021). Anxiety, depression, stress, fear and social support during COVID-19 pandemic among Jordanian Healthcare Workers. PLOS ONE, 16(3): e0247679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247679

Amadasun, S. (2020). Social work and COVID-19 pandemic: An action call. International Social Work, 63(6), 753-756. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820959357

Banerjee D, Rai M. (2020). Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(6), 525–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020922269

Banks, S. (2023). Pandemic ethics and beyond: Creating space for virtues in the social professions. Nursing Ethics, 31(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697330231177421

Banks, S., Cai, T., de Jonge, E., Shears, J., Shum, M., Sobočan, A. M., Strom, K., Truell, R., Úriz, M. J., & Weinberg, M. (2020). Practising ethically during COVID-19: Social work challenges and responses. International Social Work, 63(5), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820949614

Becker, E. S., Barth, A., Smits, J. A. J., Beisel, S., Lindenmeyer, J., & Rinck, M. (2019). Positivity-approach training for depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 245, 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.042

Benatov, J., Zerach, G., & Levi-Belz, Y. (2022). Moral injury, depression, and anxiety symptoms among health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of Belongingness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(5), 1026–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640221099421

Bern-Klug, M., Carter, K. A., & Wang, Y. (2021). More Evidence that Federal Regulations Perpetuate Unrealistic Nursing Home Social Services Staffing Ratios. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 64(7), 811–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2021.1937432

Bilder, C. R., & Tebbs, J. M. (2008). An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(483), 1323. https://doi.org/10.1198/JASA.2008.S251

Boniol, M., McIsaac, M., Xu, L., Wuliji, T., Diallo, K., & Campbell, J. (2019, March). Gender equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 countries. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/gender-equity-in-the-health-workforce-analysis-of-104-countries

Braunstein-Bercovitz, H. (2003). Does stress enhance or impair selective attention? The effects of stress and perceptual load on negative priming. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 16(4), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800310000112560

Butterworth, P., Olesen, S. C., & Leach, L. S. (2012). The role of hardship in the association between socio-economic position and depression. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(4), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867411433215

ČSÚ (the Czech Statistical Office). (2022). Seniors in the Czech Republic in data - 2022. CZSO | ČSÚ. https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/seniori-v-cr-v-datech-rtm2xuji2o

Denzin, N. K. (2017). Research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. London, England: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315134543

Eddington, K. M., Burgin, C. J., & Majestic, C. (2016). Individual Differences in Expectancies for Change in Depression: Associations with Goal Pursuit and Daily Experiences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 35(8), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2016.35.8.629

Edlund, J. (2007). The Work–Family Time Squeeze: Conflicting Demands of Paid and Unpaid Work among Working Couples in 29 Countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 48(6), 451-480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715207083338

Ferguson, H. (2018). How social workers reflect in action and when and why they don’t: the possibilities and limits to reflective practice in social work. Social Work Education, 37(4), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1413083

Fields, N., Miller, V., Anderson, K., & Kusmaul, N. (2021). Work Does Not End When You Leave: Concerns and Coping Strategies Among Nursing Home Social Workers During COVID-19. Innovation in Aging, 5(1), 380–380. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igab046.1474

Fitzpatrick, J. M., Rafferty, A. M., Hussein, S., Ezhova, I., Palmer, S., Adams, R., Rees, L., Brearley, S., Sims, S., & Harris, R. (2021). Protecting older people living in care homes from COVID-19: a protocol for a mixed-methods study to understand the challenges and solutions to implementing social distancing and isolation. BMJ Open, 11(8). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050706

Gabura, J., & Mojtova, M. (2022). Social Work in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clinical Social Work and Health Intervention, 13(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.22359/cswhi_13_1_02

Gambrill, E. (Ed.). (2017). Social Work Ethics. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315242842

Ganggi, R. I. P. (2020). Information Anxieties and Information Distrust: The effects of Overload Information about COVID – 19. E3S Web of Conferences, 202, 15014. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202020215014

Greene, T., Harju-Seppänen, J., Adeniji, M., Steel, C., Grey, N., Brewin, C. R., Bloomfield, M. A., & Billings, J. (2021). Predictors and rates of PTSD, depression and anxiety in UK frontline health and social care workers during COVID-19. European journal of psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1882781. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1882781

Guastafierro, E., Toppo, C., Magnani, F. G., Romano, R., Facchini, C., Campioni, R., Brambilla, E., & Leonardi, M. (2021). Older Adults’ Risk Perception during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Lombardy Region of Italy: A Cross-sectional Survey. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 64(6), 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2020.1870606

Guastello, S. J. (2016). Cognitive workload and fatigue in financial decision making. New York: Springer.

Healy, K. (2022). Social Work Theories in Context: Creating Frameworks for Practice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Horecký, J., & Švehlová, A. (2021). Pandemie Covidu-19 a sociální služby 2020–2021 [Covid-19 pandemic and social services 2020–2021]. Asociace poskytovatelů sociálních služeb ČR, Tábor. https://www.apsscr.cz/files/files/A4_FACT%20SHEETS%20PANDEMIE%20COVID-19.pdf

IFSW. (2014). Global definition of Social work. International Federation of Social Workers. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

Jindra, I. W., & Graves, D. M. (2025). The Role of Resilience in Social Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clinical Social Work Journal, 53, 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-024-00943-0

Johansson-Pajala, R.-M., Alam, M., Gusdal, A., Heideken Wågert, P. von, Löwenmark, A., Boström, A.-M., & Hammar, L. M. (2022). Anxiety and loneliness among older people living in residential care facilities or receiving home care services in Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03544-z

Kofta, M., Weary, G., & Sedek, G. (2011). Personal Control in Action: Cognitive and Motivational Mechanisms. Springer.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887

Lenhard, W. & Lenhard, A. (2016). Calculation of Effect Sizes. https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html

Martínez-López, J. Á., Lázaro-Pérez, C., & Gómez-Galán, J. (2021). Death Anxiety in Social Workers as a Consequence of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behavioral Sciences, 11(5), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11050061

McFadden, P., Neill, R. D., Mallett, J., Manthorpe, J., Gillen, P., Moriarty, J., Currie, D., Schroder, H., Ravalier, J., Nicholl, P., & Ross, J. (2021). Mental well-being and quality of working life in UK social workers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A propensity score matching study. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(5), 2814–2833. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab198

Michailakis, D., & Schirmer, W. (2014). Social work and social problems: A contribution from systems theory and constructionism. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(4), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12091

Mickel, A. (2019). Manage Stress to Tackle Mental Health Problems in the Workplace. Archives of Psychology, 3(7). https://www.archivesofpsychology.org/index.php/aop/article/view/126

Mikšík, O. (1999). Psychological theories of personality. Karolinum.

Milojević, S., Aleksić, V. S., & Slavković, M. (2025). “Direct Me or Leave Me”: The Effect of Leadership Style on Stress and Self-Efficacy of Healthcare Professionals. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010025

Nicholas, D.B., Samson, P. L., Hilsen, L., & McFarlane, J. (2023). Examining the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on social work in health care. Journal of Social Work, 23(2), 334 - 349. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173221142767

Nordesjö, K., & Scaramuzzino, G. (2023). Digitalization, stress, and social worker–client relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Social Work, 23(6), 1080-1098. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173231180309

Okafor, A. (2021). Role of the social worker in the outbreak of pandemics (A case of COVID-19). Cogent Psychology, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2021.1939537

Punová, M. (2021). Resilience and Personality Dispositions of Social Workers in the Czech Republic. Practice, 34(3), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2021.2021166

Saade, S., Parent-Lamarche, A., Bazarbachi, Z., Ezzeddine, R., & Ariss, R. (2021). Depressive symptoms in helping professions: a systematic review of prevalence rates and work-related risk factors. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95(1), 67–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01783-y

Sajid, S. M., Baikady, R., Sheng-Li, C., & Sakaguchi, H. (2021). The Palgrave handbook of global social work education. Springer Nature.

Shi, L., Xu, R. H., Xia, Y., Chen, D., & Wang, D. (2022). The Impact of COVID-19-Related Work Stress on the Mental Health of Primary Healthcare Workers: The Mediating Effects of Social Support and Resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800183

Schiff, M., Shinan-Altman, S., & Rosenne, H. (2021). Israeli Health Care Social Workers’ Personal and Professional Concerns during the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: The Work–Family Role Conflict. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(5), 1858–1878. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab114

Schilling, R., Morrish, J. N., & Liu, G. (2008). Demographic Trends in Social Work over a Quarter-Century in an Increasingly Female Profession. Social Work, 53(2), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/53.2.103

Schug, C., Morawa, E., Geiser, F., Hiebel, N., Beschoner, P., Jerg-Bretzke, L., Albus, C., Weidner, K., Steudte-Schmiedgen, S., Borho, A., Lieb, M., & Erim, Y. (2021). Social Support and Optimism as Protective Factors for Mental Health among 7765 Healthcare Workers in Germany during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of the VOICE Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073827

Sicora, A. (2017). Reflective Practice, Risk and Mistakes in Social Work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 31(4), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2017.1394823

Siebert, D. C. (2004). Depression in North Carolina social workers: Implications for practice and research. Social Work Research, 28(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/28.1.30

Silton, R. L., Kahrilas, I. J., Skymba, H. V., Smith, J., Bryant, F. B., & Heller, W. (2020). Regulating positive emotions: Implications for promoting well-being in individuals with depression. Emotion, 20(1), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000675

Specht, H., & Vickery, A. (Eds.). (2021). Integrating Social Work Methods. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003199243

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092-1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Truhlářová, Z., Havigerová, J. M., & Haviger, J. (2021). Analýza dopadů pandemické zkušenosti na sociální pracovníky ve veřejné správě. [Analysis of the impact of the pandemic experience on social workers in public administration]. MPSV. https://www.mpsv.cz/documents/20142/1864403/Anal%C3%BDza_dopad%C5%AF_final.pdf/c9511946-3835-7be5-c0fc-8284a47dcfa7

Tsai, C. Y. (2022). Social support, Self-Esteem, and Levels of Stress, Depression, and Anxiety During the Covid-19 Pandemic. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1789

Tsui, MS., Pai, R.C.J., Wong, P.Y.J., Chu, CH. (2023). Emerging Ethical Voices in Social Work. In D. Hölscher, R. Hugman, & D. McAuliffe (Eds.), Social Work Theory and Ethics. Social Work (pp.463-478). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1015-9_24

Van Zyl, L. E., & Rothmann, S. (2022). Grand Challenges for Positive Psychology: Future Perspectives and Opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 833057. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.833057

Weinberg, M. (2020). Exacerbation of Inequities During Covid-19: Ethical Implications for Social Workers. Canadian Social Work Review / Revue canadienne de service social, 37(2), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.7202/1075117ar

Ying, Y.-W. (2009). Contribution of self-compassion to competence and mental health in social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 45(2), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.5175/jswe.2009.200700072

Zajacová, M. (2021). The importance and role of social work in the activities of social administration. In K. Šámalová, Vojtíšek, P. (Eds.), Social Administration. Organization and Management of Social Systems (pp. 407–420). Grada.

Zandvakili, M., Jalilvand, M., & Nikmanesh, Z. (2014). The Effect of Positive Thinking Training on Reduction of Depression, Stress and Anxiety of Juvenile Delinquents. International Journal of Medical Toxicology and Forensic Medicine, 4(2), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.22037/ijmtfm.v4i2(Spring).5622

Zhan, J., Chen, C., Yan, X., Wei, X., Zhan, L., Chen, H., & Lu, L. (2022). Relationship between social support, anxiety, and depression among frontline healthcare workers in China during COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.947945

Zhou, Y., Xu, J., & Rief, W. (2020). Are comparisons of mental disorders between Chinese and German students possible? An examination of measurement invariance for the PHQ-15, PHQ-9 and GAD-7. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 480. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02859-8